Under the Radar's Top 100 Albums of 2019

2019 was a divisive and toxic year for politics on both sides of the Atlantic and elsewhere, but can we all agree that the decade's final year was firmly a fantastic one for music? Probably not, but here at Under the Radar we certainly felt that way.

Source

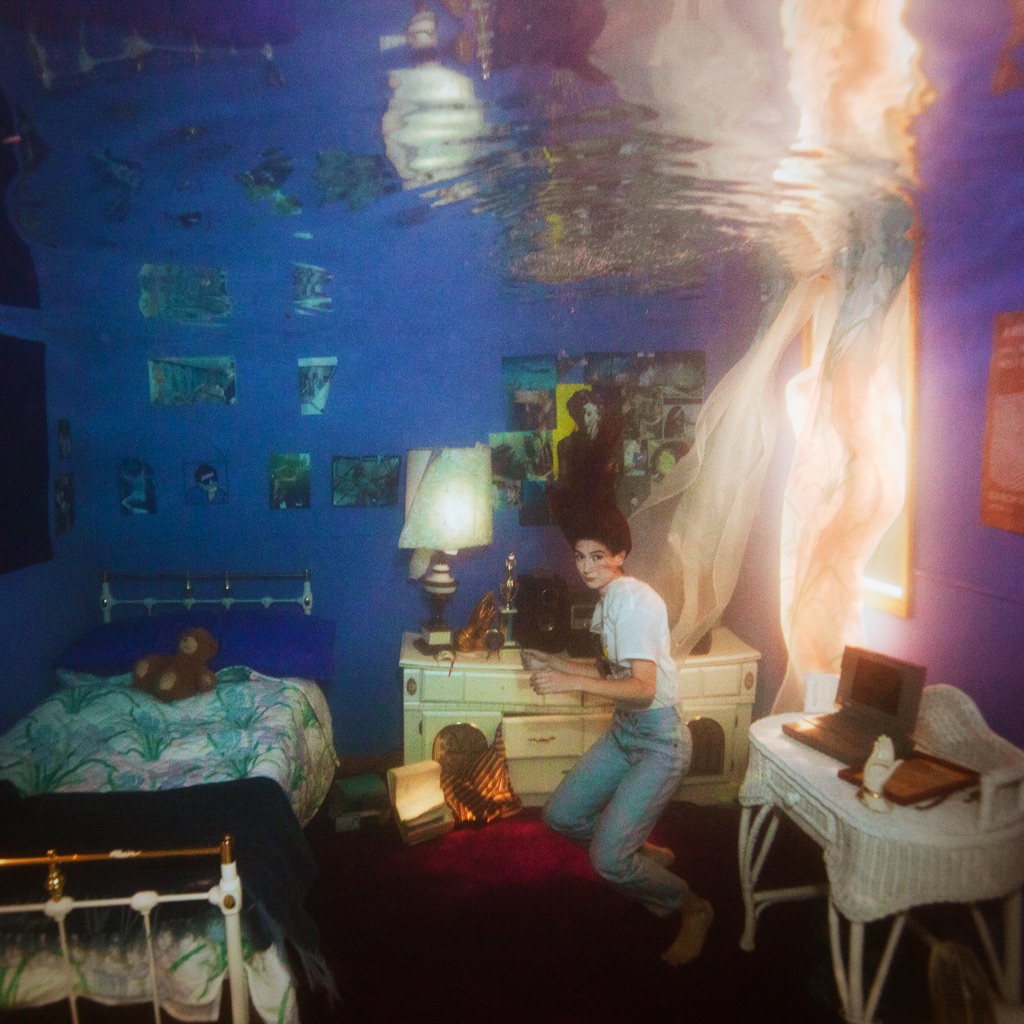

Singer-songwriter Natalie Mering’s fourth album as Weyes Blood conjures the feeling of a beautiful object on a shelf just out of reach: You want to touch it, but you can’t, and so you do the next best thing—you dream about it, ache for it, and then you ache some more. Grand, melodramatic, but keenly self-aware, the music here pushes Mering’s \'70s-style chamber pop to its cinematic brink, suffusing stories of everything from fumbled romance (the McCartney-esque “Everyday”) to environmental apocalypse (“Wild Time”) with a dreamy, foggy almost-thereness both gorgeous and profoundly unsettling. A self-described “nostalgic futurist,” Mering doesn’t recreate the past so much as demonstrate how the past is more or less a fiction to begin with, a story we love hearing no matter how sad its unreachability makes us. Hence the album’s centerpiece, “Movies,” which wonders—gorgeously, almost religiously—why life feels so messy by comparison. As to the thematic undercurrent of apocalypse, well, if extinction is as close as science says it is, we might as well have something pretty to play us out.

The phantom zone, the parallax, the upside down—there is a rich cultural history of exploring in-between places. Through her latest, Titanic Rising, Weyes Blood (a.k.a. Natalie Mering) has, too, designed her own universe to soulfully navigate life’s mysteries. Maneuvering through a space-time continuum, she intriguingly plays the role of melodic, sometimes melancholic, anthropologist. Tellingly, Mering classifies Titanic Rising as the Kinks meet WWII or Bob Seger meets Enya. The latter captures the album’s willful expansiveness (“You can tell there’s not a guy pulling the strings in Enya’s studio,” she notes, admiringly). The former relays her imperative to connect with listeners. “The clarity of Bob Seger is unmistakable. I’m a big fan of conversational songwriting,” she adds. “I just try to do that in a way that uses abstract imagery as well.” “An album is like a Rubik’s Cube,” she says. “Sometimes you get all the dimensions—the lyrics, the melody, the production—to line up. I try to be futuristic and ancient at once, which is a difficult alchemy. It’s taken a lot of different tries to get it right.” As concept-album as it may sound, it’s also a devoted exercise in realism, albeit occasionally magical. Here, the throwback-cinema grandeur of “A Lot’s Gonna Change” gracefully coexists with the otherworldly title track, an ominous instrumental. Titanic Rising, written and recorded during the first half of 2018, is the culmination of three albums and years of touring: stronger chops and ballsier decisions. It’s an achievement in transcendent vocals and levitating arrangements—one she could reach only by flying under the radar for so many years. “I used to want to belong,” says the L.A. based musician. “I realized I had to forge my own path. Nobody was going to do that for me. That was liberating. I became a Joan of Arc solo musician.” The Weyes Blood frontwoman grew up singing in gospel and madrigal choirs. “Classical and Renaissance music really influenced me,” says Mering, who first picked up a guitar at age 8. (Listen closely to Titanic Rising, and you’ll also hear the jazz of Hoagy Carmichael mingle with the artful mysticism of Alejandro Jodorowsky and the monomyth of scholar Joseph Campbell.) “Something to Believe,” a confessional that makes judicious use of the slide guitar, touches on that cosmological upbringing. “Belief is something all humans need. Shared myths are part of our psychology and survival,” she says. “Now we have a weird mishmash of capitalism and movies and science. There have been moments where I felt very existential and lost.” As a kid, she filled that void with Titanic. (Yes, the movie.) “It was engineered for little girls and had its own mythology,” she explains. Mering also noticed that the blockbuster romance actually offered a story about loss born of man’s hubris. “It’s so symbolic that The Titanic would crash into an iceberg, and now that iceberg is melting, sinking civilization.” Today, this hubris also extends to the relentless adoption of technology, at the expense of both happiness and attention spans. The track “Movies” marks another Titanic-related epiphany, “that movies had been brainwashing people and their ideas about romantic love.” To that end, Mering has become an expert at deconstructing intimacy. Sweeping and string-laden, “Andromeda” seems engineered to fibrillate hearts. “It’s about losing your interest in trying to be in love,” she says. “Everybody is their own galaxy, their own separate entity. There is a feeling of needing to be saved, and that’s a lot to ask of people.” Its companion track, “Everyday,” “is about the chaos of modern dating,” she says, “the idea of sailing off onto your ships to nowhere to deal with all your baggage.” But Weyes Blood isn’t one to stew. Her observations play out in an ethereal saunter: far more meditative than cynical. “I experience reality on a slower, more hypnotic level,” she says. “I’m a more contemplative kind of writer.” To Mering, listening and thinking are concurrent experiences. “There are complicated influences mixed in with more relatable nostalgic melodies,” she says. “In my mind my music feels so big, a true production. I’m not a huge, popular artist, but I feel like one when I’m in the studio. But it’s never taking away from the music. I’m just making a bigger space for myself.”

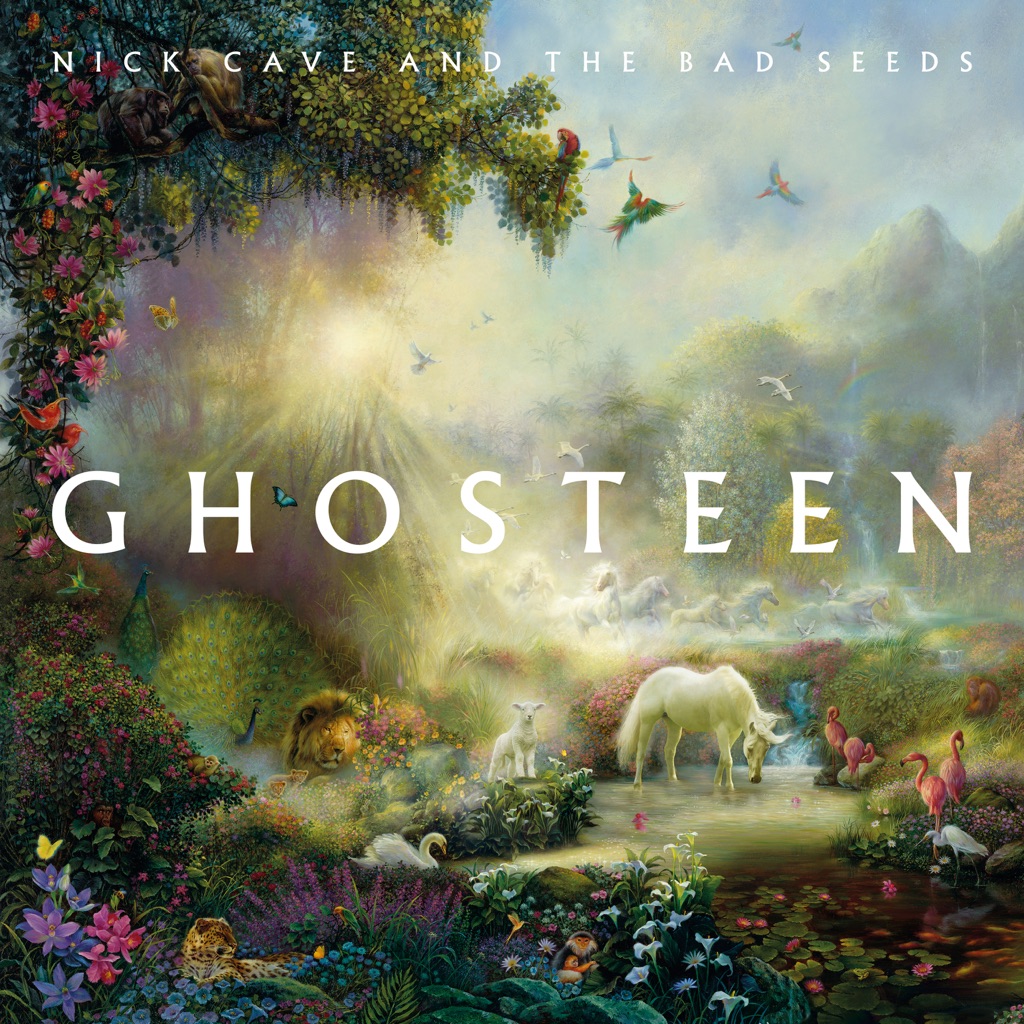

The cover art for Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ 17th album couldn’t feel more removed from the man once known as a snarling, terrifying prince of poetic darkness. This heavenly forest with its vibrant flowers, rays of sun, and woodland creatures feels comically opposed to anything Cave has ever represented—but perhaps that’s the point. This pastel fairy tale sets the scene for *Ghosteen*, his most minimalist, supernatural work to date, in which he slips between realms of fantasy and reality as a means to accept life and death, his past and future. In his very first post on The Red Hand Files—the website Cave uses to receive and respond to fan letters—he spoke of rebuilding his relationship with songwriting, which had been damaged while enduring the grief that followed his son Arthur’s death in 2015. He wrote, “I found with some practise the imagination could propel itself beyond the personal into a state of wonder. In doing so the colour came back to things with a renewed intensity and the world seemed clear and bright and new.” It is within that state of wonder that *Ghosteen* exists. “The songs on the first album are the children. The songs on the second album are their parents,” Cave has explained. Those eight “children” are misty, ambient stories of flaming mares, enchanted forests, flying ships, and the eponymous, beloved Ghosteen, described as a “migrating spirit.” The second album features two longer pieces, connected by the spoken-word “Fireflies.” He tells fantasy stories that allude to love and loss and letting go, and occasionally brings us back to reality with detailed memories of car rides to the beach and hotel rooms on rainy days. These themes aren’t especially new, but the feeling of this album is. There are no wild murder ballads or raucous, bluesy love songs. Though often melancholy, it doesn’t possess the absolute devastation and loneliness of 2016’s *Skeleton Tree*. Rather, these vignettes and symbolic myths are tranquil and gentle, much like the instrumentation behind them. With little more than synths and piano behind Cave’s vocals, *Ghosteen* might feel uneventful at times, but the calmness seems to help his imagination run free. On “Bright Horses,” he sings of “Horses broken free from the fields/They are horses of love, their manes full of fire.” But then he pulls back the curtain and admits, “We’re all so sick and tired of seeing things as they are/Horses are just horses and their manes aren’t full of fire/The fields are just fields, and there ain’t no lord… This world is plain to see, it don’t mean we can’t believe in something.” Through these dreamlike, surreal stories, Cave is finding his path to peace. And he’s learned that he isn’t alone on his journey. On “Galleon Ship,” he begins, “If I could sail a galleon ship, a long, lonely ride across the sky,” before realizing: “We are not alone, it seems, so many riders in the sky/The winds of longing in their sails, searching for the other side.”

“How people may emotionally connect with music I’ve been involved in is something that part of me is completely mystified by,” Thom Yorke tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “Human beings are really different, so why would it be that what I do connects in that way? I discovered maybe around \[Radiohead\'s album\] *The Bends* that the bit I didn’t want to show, the vulnerable bit… that bit was the bit that mattered.” *ANIMA*, Yorke’s third solo album, further weaponizes that discovery. Obsessed by anxiety and dystopia, it might be the most disarmingly personal music of a career not short of anxiety and dystopia. “Dawn Chorus” feels like the centerpiece: It\'s stop-you-in-your-tracks beautiful with a claustrophobic “stream of consciousness” lyric that feels something like a slowly descending panic attack. And, as Yorke describes, it was the record\'s biggest challenge. “There’s a hit I have to get out of it,” he says. “I was trying to develop how ‘Dawn Chorus’ was going to work, and find the right combinations on the synthesizers I was using. Couldn’t find it, tried it again and again and again. But I knew when I found it I would have my way into the song. Things like that matter to me—they are sort of obsessive, but there is an emotional connection. I was deliberately trying to find something as cold as possible to go with it, like I sing essentially one note all the way through.” Yorke and longtime collaborator Nigel Godrich (“I think most artists, if they\'re honest, are never solo artists,” Yorke says) continue to transfuse raw feeling into the album’s chilling electronica. “Traffic,” with its jagged beats and “I can’t breathe” refrain, feels like a partner track to another memorable Yorke album opener, “Everything in Its Right Place.” The extraordinary “Not the News,” meanwhile, slaloms through bleeps and baleful strings to reach a thunderous final destination. It’s the work of a modern icon still engaged with his unique gift. “My cliché thing I always say is, \'You know you\'re in trouble when people stop listening to sad music,\'” Yorke says. “Because the moment people stop listening to sad music, they don\'t want to know anymore. They\'re turning themselves off.”

Though she’d been writing songs in her head since she was six, and on the guitar since she was 12, it took a long time for Nilüfer Yanya to work up the courage to show anyone her music. “I knew I wanted to sing, but the idea of actually having to do it was really horrifying,” says the 23-year-old. When she was finally persuaded to do so, by a music teacher in West London where she grew up, she says “it was horrible. I loved it”. At 18, Nilüfer – who is of Turkish-Irish-Bajan heritage – uploaded a few demos to SoundCloud. Though she’s preternaturally shy, her music – which uniquely blends elements of soul and jazz into intimate pop songs with electronic flourishes and a newly expressed grungy guitar sound – isn’t. And it didn’t take long for it to catch people’s attention. She signed with independent New York label ATO, following three EPs on esteemed london indie label Blue Flowers, and earned a place on the BBC Sound of 2018 longlist. She also supported the likes of The xx, Interpol, Broken Social Scene and Mitski on tour. Now, Nilüfer is ready to release her debut album, Miss Universe. Though she recorded much of it in the same remote Cornwall studio she used to jam in as a much younger person, it is bigger and more ambitious than anything she has done before. ‘Angels’, with its muted, harmonic riffs, channels ideas “of paranoid thoughts and anxiety” – a theme that runs through the album, not least in its conceptual spoken word interludes which emanate from a fictional health management company WWAY HEALTH TM. “You sign up, and you pay a fee,” explains Nilüfer of the automated messages, which are littered through the album and are narrated by the titular Miss Universe. “They sort out all of your dietary requirements, and then they move onto medication, and then maybe you can get a better organ or something… and then suddenly it starts to get a bit weird. You're giving them more of you and to what end?”

On her fifth proper full-length album, Sharon Van Etten pushes beyond vocals-and-guitar indie rock and dives headlong into spooky maximalism. With production help from John Congleton (St. Vincent), she layers haunting drones with heavy, percussive textures, giving songs like “Comeback Kid” and “Seventeen” explosive urgency. Drawing from Nick Cave, Lucinda Williams, and fellow New Jersey native Bruce Springsteen, *Remind Me Tomorrow* is full of electrifying anthems, with Van Etten voicing confessions of reckless, lost, and sentimental characters. The album challenges the popular image of Van Etten as *just* a singer-songwriter and illuminates her significant talent as composer and producer, as an artist making records that feel like a world of their own.

Despite an earlier stint in Brisbane quartet Go Violets, Harriette Pilbeam seemed to emerge out of nowhere with her 2018 debut EP as Hatchie. The immersive dream-pop of *Sugar & Spice* earned strong notices around the world, and the full-length follow-up *Keepsake* continued Pilbeam’s winning combination of brightly careening melodies and lush textural depth. Even when Pilbeam applies woozy washes of guitar effects, they serve to heighten her sharp pop instincts rather than obscure them. Observe how “Without a Blush” carves out a roomy atmosphere far in advance of its headily romantic chorus, or how “Secret” culminates in a shimmering latticework of overlapping vocals. Several songs hark back to the mid-’90s radio hits of The Cranberries and The Sundays, even as heavier turns point toward My Bloody Valentine and the Cocteau Twins. All the while, Pilbeam’s sighing, empathic vocals capture the upending sensation of new love and other seismic emotional events. Pilbeam would tease out even more electronic elements on 2022’s *Giving the World Away*, following through on the sleepy club hook deployed here for “Stay With Me.” She would also enlist top co-writers like Olivia Rodrigo collaborator Dan Nigro to take her songwriting ever more skyward with undeniable earworms like “Quicksand.”

Big Thief has been known to tackle intensely personal themes: family histories, deaths, isolation, fear. Here, on their expansive third album, the New York indie rock band shifts its gaze outward and into the unknown. \"Just like a bad dream/You\'ll disappear,” frontwoman Adrianne Lenker coos on the title track. \"And I imagine you/Taking me outta here.” Through gentle strums and hushed, tumbling melodies, the band wonders: Who\'s out there? Are they as strange as we are? What’s real? The second F in the album’s title stands for “friend”—an optimistic embrace of all things unfamiliar or alien. Their songs—comforting, eerie, folksy, magnificent—do the same.

U.F.O.F., F standing for ‘Friend’, is the name of the highly anticipated third record by Big Thief, set to be released on 3rd May 2019 via 4AD. U.F.O.F. was recorded in rural western Washington at Bear Creek Studios. In a large cabin-like room, the band set up their gear to track live with engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who was also behind their previous albums. Having already lived these songs on tour, they were relaxed and ready to experiment. The raw material came quickly. Some songs were written only hours before recording and stretched out instantly, first take, vocals and all. “Making friends with the unknown… All my songs are about this,” says Lenker; “If the nature of life is change and impermanence, I’d rather be uncomfortably awake in that truth than lost in denial.”

London-based composer Anna Meredith loves a corkscrew spiral, a manic grid, and key changes that lurch between nausea and pleasure. Few songs on her second album, *Fibs*, end where they start—“Sawbones” traverses precipitous bass, chiptune reverie, and a symphony in hyperdrive—yet her classical grounding ensures a keen eye on the dynamic sweep. An opening half of screaming crescendos (“Calion”) and regal pomp (“Killjoy”) begets a reprieve of power pop (“Limpet”) and girlish dreaminess (“Ribbons”)—only to end with a bang with “Paramour,” a song that makes “Sawbones” sound like Debussy’s “Clair de Lune.”

The eagerly anticipated second studio album, FIBS, is out now via Moshi Moshi/Black Prince Fury. Arriving three and a half years on from the release of her Scottish Album of the Year Award-winning debut studio album Varmints, FIBS is 45 minutes of technicolour maximalism, almost perpetual rhythmic reinvention, and boasts a visceral richness and unparalleled accessibility. FIBS is no “Varmints Part 2” — the retreading of old ground, or even a smooth progression from one project to another, just isn’t Meredith’s style. Instead, if anything, it’s “Varmints 2.0”, an overhauled and updated version of the composer’s soundworld, involving, in places, a literal retooling that has seen Meredith chuck out her old MIDI patches and combine her unique compositional voice with brand-new instruments, both acoustic and electronic, and a writing process that’s more intense than she’s ever known. Despite Meredith’s background and skills these tracks are no academic exercise, the world of FIBS is at both overwhelming and intimate, a journey of intense energy and joyful irreverence. FIBS, says Meredith, are “lies — but nice friendly lies, little stories and constructions and daydreams and narratives that you make for yourself or you tell yourself”. Entirely internally generated and perfectly balanced, they can be a source of comfort and excitement, intrigue and endless entertainment. The eleven fibs contained on Anna Meredith’s second record will do all that, and more besides.

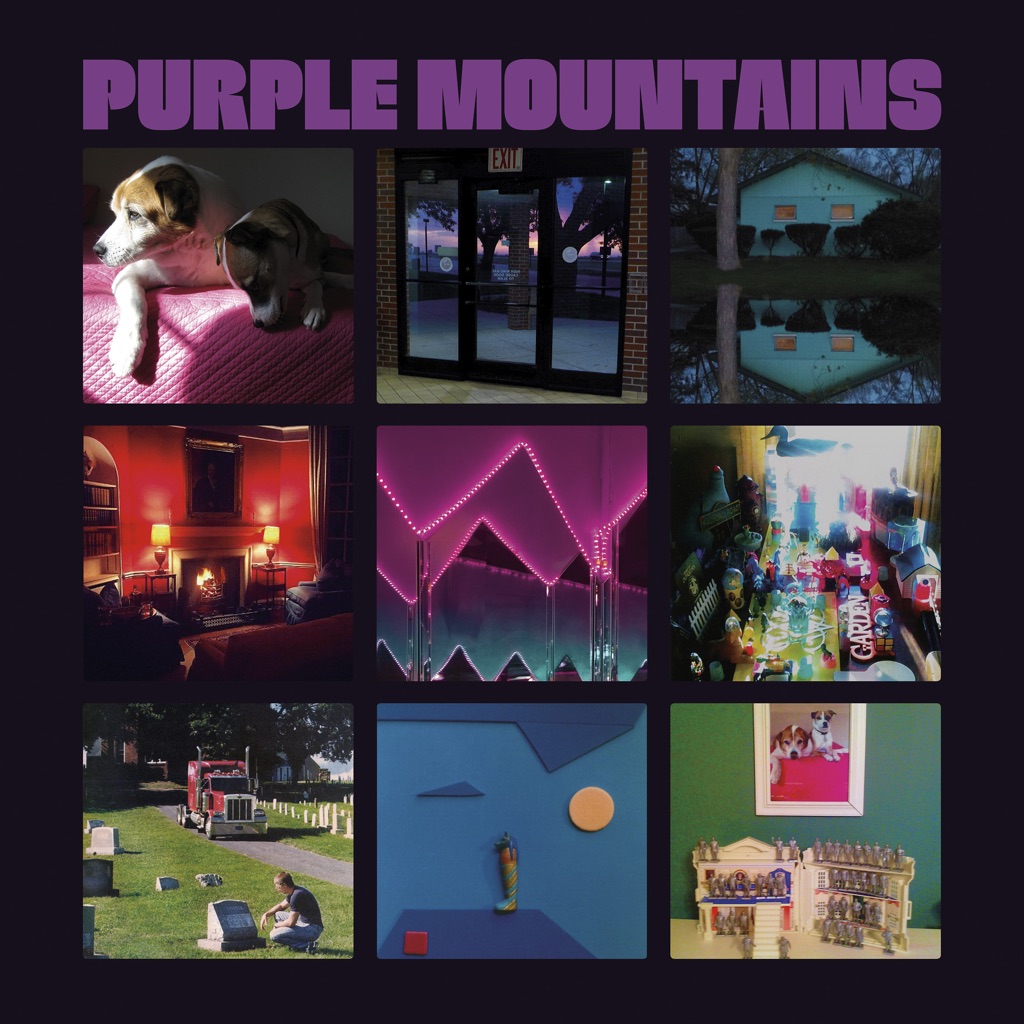

When David Berman disbanded Silver Jews in 2009, the world stood to lose one of the best writers in indie rock, a guy who catalogued the magic and misery of everyday life with wit, heart, and the ragged glory of the occupationally down-and-out. After a 10-year break professedly spent reading books and arguing with people on Reddit, Berman enlisted members of the Brooklyn band Woods to back him on *Purple Mountains*. Berman’s pain had never been laid quite so bare, nor had it ever sounded quite so urgent. “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion,” he sings on the swaggering “That’s Just the Way I Feel.” “Day to day, I’m neck and neck with giving in.” And “Margaritas at the Mall” turns an ordinary happy hour into a jeremiad about the cold comforts of capitalism in a godless world. That the music—country-tinged indie rock—was as polished and competent as it was only highlighted Berman’s intensity: less a rock singer than a street preacher, someone who needed to avail himself of his visions stat. But even at his most desperate, he remained achingly funny, turning statements of existential loneliness into the kind of bumper sticker Zen that made him seem like an ordinary guy no matter how highfalutin he could get. “Well, if no one’s fond of fuckin’ me, maybe no one’s fuckin’ fond of me,” he sings on the album-closing “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” sounding not all that far off from the George Strait one-twos he reportedly loved. Above all, though, his writing is beautiful, attuned to detail in ways that make ordinary scenarios shimmer with quiet magic. Just listen to “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan,” which turns a quiet night in a big city into an allegory of finding solace in the weather of what comes to us. Shortly after the release of *Purple Mountains*, Berman died, at the age of 52, a tragic end to what felt like a triumphant return. “The dead know what they\'re doing when they leave this world behind,” he sings on “Nights That Won’t Happen.” “When the here and the hereafter momentarily align.”

David Berman comes in from the cold after ten long years. His new musical expression is a meltdown unparalleled in modern memory. He warns us that his findings might be candid, but as long as his punishment comes in such bite-sized delights of all-American jukebox fare, we'll hike the Purple Mountains with pleasure forever.

\"Kids in the Dark\" ushers in Bat for Lashes\' fifth album on a wave of cinematic synths that sounds like sunset and open road. It\'s the perfect introduction to a conceptual cycle that finds London-bred singer-songwriter Natasha Khan inhaling a throwback version of her new LA home base. Khan is no stranger to inhabiting complex characters (the widow of 2016\'s *The Bride*) and motifs (the fairy-tale fantasies of her debut, *Fur and Gold*), and likewise, *Lost Girls* hinges on Nikki Pink, whom Khan has described as \"a more Technicolor version\" of herself. In addition to its clear nods to the 1987 film *The Lost Boys*, the record takes cues from the original screenplay Khan was working on upon her relocation, inspired by \'80s kid flicks and vampire films, and blows them out in neon songs, tinged with drama and romance. The saxophone-laden instrumental \"Vampires\" calls to mind retro climactic scenes where imminent peril is blocked out by hope, while the disarmingly bright \"So Good\" embodies the kind of glamorous and carefree existence we often ascribe to the past. \"Why does it hurt so good?\" she begs on the hook, projecting all of the delight and none of the suffering. Khan is a master of conjuring thematic atmosphere, but here, she inhabits her era with particular gusto. In a pop culture landscape that remains obsessed with nostalgia, on *Lost Girls*, Khan transforms the familiar tropes of the past into something that feels fresh and revelatory—we are able to see old things anew, through the eyes of a person she\'s never been in a time and place she\'s never lived.

Melina Duterte is a master of voice: Hers are dream pop songs that hint at a universe of her own creation. Recording as Jay Som since 2015, Duterte’s world of shy, swirling intimacies always contains a disarming ease, a sky-bent sparkle and a grounding indie-rock humility. In an era of burnout, the title track of her 2017 breakout, Everybody Works, remains a balm and an anthem. Duterte’s life became a whirlwind in the wake of Everybody Works. After spending her teen years and early 20s exploring an eclectic array of musical styles—studying jazz trumpet as a child, carrying on her Filipino family tradition of spirited karaoke, and quietly recording indie-pop songs in her bedroom alone—that accomplished album found her playing festivals around the world, sharing stages with the likes of Paramore, Death Cab for Cutie, and Mitski. In November of 2017, seeking a new environment, Duterte left her home of the Bay Area for Los Angeles. There, she demoed new songs, while also embracing opportunities to do session work and produce, engineer, and mix for other artists (like Sasami, Chastity Belt). Reckoning with the relative instability of musicianhood, Duterte turned inward, tuning ever deeper into her own emotions and desires as a way of staying centered through huge changes. She found a community; she fell in love. And for an artist whose career began after releasing her earliest collection of demos—2015's hazy but exquisitely crafted Turn Into—in a fit of drunken confidence on Thanksgiving night, she finally quit drinking for good. “I feel like a completely different person,” she reflects. Positivity was a way forward. The striking clarity of her new music reflects that shift. After months of poring over pools of demos, Duterte, now 25, essentially started over. She wrote most of her brilliant new album, Anak Ko—pronounced Anuhk-Ko—in a burst during a self-imposed week-long solo retreat to Joshua Tree. As in the past, Duterte recorded at home (in some songs, you can hear the washer/dryer near her bedroom) and remained the sole producer, engineer, and mixer. But for the first time, she recruited friends—including Vagabon’s Laetitia Tamko, Chastity Belt’s Annie Truscott, Justus Proffitt, Boy Scouts’ Taylor Vick, as well as bandmates Zachary Elasser, Oliver Pinnell and Dylan Allard—to contribute additional vocals, drums, guitars, strings, and pedal steel. Honing in on simplicity and groove, refining her skills as a producer, Duterte cracked her sound open subtly, highlighting its best parts: She’s bloomed. Inspired by the lush, poppy sounds of 80s bands such as Prefab Sprout, the Cure, and Cocteau Twins—as well as the ecstatic guitarwork of contemporary Vancouver band Weed—Anak Ko sounds dazzlingly tactile, and firmly present. The result is a refreshingly precise sound. On the subtly explosive “Superbike,” Duterte aimed for the genius combination of “Cocteau Twins and Alanis Morissette”—“letting loose,” she says, over swirling shoegaze. “Night Time Drive” is a restless road song, but one with a sense of contentedness and composure, which “basically encapsulated my entire life for the past two years,” she says—always moving, but “accepting it, being a little stronger from it.” (She sings, memorably, of “shoplifting at the Whole Foods.”) Duterte focused more on bass this time: “I just wanted to make a more groovy record,” she notes. The slow-burning highlight “Tenderness” begins minimally, like a slightly muffled phone call, before flowering into a bright, jazzy earworm. Duterte calls it “a feel-good, funky, kind of sexy song” in part about “the curse of social media” and how it complicates relationships. “That’s definitely about scrolling on your phone and seeing a person and it just haunts you, you can’t escape it,” Duterte says. “I have a weird relationship to social media and how people perceive me—as this person that has a platform, as a solo artist, and this marginalized person. That was really getting to me. I wanted to express those emotions, but I felt stifled. I feel like a lot of the themes of the songs stemmed from bottled up emotions, frustration with yourself, and acceptance.” The title, Anak Ko, means “my child" in Tagalog, one of the native dialects in the Philippines. It was inspired by an unassuming text message from Duterte’s mother, who has always addressed her as such: Hi anak ko, I love you anak ko. “It’s an endearing thing to say, it feels comfortable,” Duterte reflects, likening the process of creating and releasing an album, too, to “birthing a child.” That sense of care charges Anak Ko, as does another concept Duterte has found herself circling back to: the importance of patience and kindness. “In order to change, you’ve got to make so many mistakes,” Duterte says, reflecting on her recent growth as an artist with a zen-like calm. “What’s helped me is forcing myself to be even more peaceful and kind with myself and others. You can get so caught up in attention, and the monetary value of being a musician, that you can forget to be humble. You can learn more from humility than the flashy stuff. I want kindness in my life. Kindness is the most important thing for this job, and empathy.”

Look past its futurist textures and careful obfuscations, and there’s something deeply human about FKA twigs’ 21st-century R&B. On her second full-length, the 31-year-old British singer-songwriter connects our current climate to that of Mary Magdalene, a healer whose close personal relationship with Christ brought her scorn from those who would ultimately write her story: men. “I\'m of a generation that was brought up without options in love,” she tells Apple Music. “I was told that as a woman, I should be looked after. It\'s not whether I choose somebody, but whether somebody chooses me.” Written and produced by twigs, with major contributions from Nicolas Jaar, *MAGDALENE* is a feminist meditation on the ways in which we relate to one another and ourselves—emotionally, sexually, universally—set to sounds that are at once modern and ancient. “Now it’s like, ‘Can you stand up in my holy terrain?’” she says, referencing the titular lyric from her mid-album collaboration with Future. “‘How are we going to be equals in this? Spiritually, am I growing? Do you make me want to be a better person?’ I’m definitely still figuring it out.” Here, she walks us through the album track by track. **thousand eyes** “All the songs I write are autobiographical. Anyone that\'s been in a relationship for a long time, you\'re meshed together. But unmeshing is painful, because you have the same friends or your families know each other. No matter who you are, the idea of leaving is not only a heart trauma, but it\'s also a social trauma, because all of a sudden, you don\'t all go to that pub that you went to together. The line \[\'If I walk out the door/A thousand eyes\'\] is a reference to that. At the time, I was listening to a lot of Gregorian music. I’d started really getting into medieval chords before that, and I\'d found some musicians that play medieval music and done a couple sessions with them. Even on \[2014\'s\] *LP1*, I had ‘Closer,’ which is essentially a hymn. I spent a lot of time in choir as a child and I went to Sunday school, so it’s part of who I am at this stage.” **home with you** “I find things like that interesting in the studio, just to play around and bring together two completely different genres—like Elton John chords and a hip-hop riff. That’s what ‘home with you’ was for me: It’s a ballad and it\'s sad, but then it\'s a bop as well, even though it doesn\'t quite ever give you what you need. It’s about feeling pulled in all directions: as a daughter, or as a friend, or as a girlfriend, or as a lover. Everyone wanting a piece of you, but not expressing it properly, so you feel like you\'re not meeting the mark.” **sad day** “It’s like, ‘Will you take another chance with me? Can we escape the mundane? Can we escape the cyclical motion of life and be in love together and try something that\'s dangerous and exhilarating? Yeah, I know I’ve made you sad before, but will you give me another chance?\' I wrote this song with benny blanco and Koreless. I love to set myself challenges, and it was really exciting to me, the challenge of retaining my sound while working with a really broad group of people. I was lucky working with Benny, in the fact that he creates an environment where, as an artist, you feel really comfortable to be yourself. To me, that\'s almost the old-school definition of a producer: They don\'t have to be all up in your grill, telling you what to do. They just need to lay a really beautiful, fertile soil, so that you can grow to be the best you in the moment.” **holy terrain** “I’m saying that I want to find a man that can stand up next to me, in all of my brilliance, and not feel intimidated. To me, Future’s saying, ‘Hey, I fucked up. I filled you with poison. I’ve done things to make you jealous. Can you heal me? Can you tell me how to be a better man? I need the guidance, of a woman, to show me how to do that.’ I don\'t think that there are many rappers that can go there, and just put their cards on the table like that. I didn\'t know 100%, once I met Future, that it would be right. But we spoke on the phone and I played him the album and I told him what it was about: ‘It’s a very female-positive, femme-positive record.’ And he was just like, ‘Yeah. Say no more. I\'ve got this.’ And he did. He crushed it. To have somebody who\'s got patriarchal energy come through and say that, wanting to stand up and be there for a woman, wanting to have a woman that\'s an equal—that\'s real.” **mary magdalene** “Let’s just imagine for one second: Say Jesus and Mary Magdalene are really close, they\'re together all the time. She\'s his right-hand woman, she’s his confidante, she\'s healing people with him and a mystic in her own right. So, at that point, any man and woman that are spending that much time together, they\'re likely to be what? Lovers. Okay, cool. So, if Mary had Jesus\' children, that basically debunks the whole of history. Now, I\'m not saying that happened. What I\'m saying is that the idea of people thinking that might happen is potentially really dangerous. It’s easier to call her a whore, because as soon as you call a woman a whore, it devalues her. I see her as Jesus Christ\'s equal. She’s a male projection and, I think, the beginning of the patriarchy taking control of the narrative of women. Any woman that\'s done anything can be subject to that; I’ve been subject to that. It felt like an apt time to be talking about it.” **fallen alien** “When you\'re with someone, and they\'re sleeping, and you look at them, and you just think, \'No.\' For me, it’s that line, \[\'When the lights are on, I know you/When you fall asleep, I’ll kick you down/By the way you fell, I know you/Now you’re on your knees\'\]. You\'re just so sick of somebody\'s bullshit, you\'re just taking it all day, and then you\'re in bed next to them, and you\'re just like, ‘I can\'t take this anymore.’” **mirrored heart** “People always say, ‘Whoever you\'re with, they should be a reflection of yourself.’ So, if you\'re looking at someone and you think, ‘You\'re a shitbag,’ then you have to think about why it was that person, at that time, and what\'s connecting you both. What is the reflection? For others that have found a love that is a true reflection of themselves, they just remind me that I don\'t have that, a mirrored heart.” **daybed** “Have you ever forgotten how to spell a really simple word? To me, depression\'s a bit like that: Everything\'s quite abstract, and even slightly dizzy, but not in a happy way. It\'s like a very slow circus. Suddenly the fruit flies seem friendly, everything in the room just starts having a different meaning and you even have a different relationship with the way the sofa cushions smell. \[Masturbation\] is something to raise your endorphins, isn\'t it? It’s either that or try and go to the gym, or try and eat something good. You almost can\'t put it into words, but we\'ve all been there. I sing, \'Active are my fingers/Faux, my cunnilingus\': You\'re imagining someone going down on you, but they\'re actually not. You open your eyes, and you\'re just there, still on your sofa, still watching daytime TV.” **cellophane** “It\'s just raw, isn\'t it? It didn\'t need a thing. The vocal take that\'s on the record is the demo take. I had a Lyft arrive outside the studio and I’d just started playing the piano chords. I was like, ‘Hey, can you just give me like 20, 25 minutes?’ And I recorded it as is. I remember feeling like I wanted to cry, but I just didn\'t feel like it was that suitable to cry at a studio session. I often want everything to be really intricate and gilded, and I want to chip away at everything, and sculpt it, and mold it, and add layers. The thing I\'ve learned on *MAGDALENE* is that you don\'t need to do that all the time, and just because you can do something, it doesn\'t mean you should. That\'s been a real growing experience for me—as a musician, as a producer, as a singer, even as a dancer. Something in its most simple form is beautiful.”

Big Thief had only just finished work on their 3rd album, U.F.O.F. – “the celestial twin” – days before in a cabin studio in the woods of Washington State. Now it was time to birth U.F.O.F.’s sister album – “the earth twin” – Two Hands. 30 miles west of El Paso, surrounded by 3,000 acres of pecan orchards and only a stone’s throw from the Mexican border, Big Thief (a.k.a. Adrianne Lenker, Buck Meek, Max Oleartchik, and James Krivchenia) set up their instruments as close together as possible to capture their most important collection of songs yet. Where U.F.O.F.layered mysterious sounds and effects for levitation, Two Hands grounds itself on dried-out, cracked desert dirt. In sharp contrast to the wet environment of the U.F.O.F. session, the southwestern Sonic Ranch studio was chosen for its vast desert location. The 105-degree weather boiled away any clinging memories of the green trees and wet air of the previous session. Two Hands had to be completely different — an album about the Earth and the bones beneath it. The songs were recorded live with almost no overdubs. All but two songs feature entirely live vocal takes, leaving Adrianne’s voice suspended above the mix in dry air, raw and vulnerable as ever. “Two Hands has the songs that I’m the most proud of; I can imagine myself singing them when I’m old,” says Adrianne. “Musically and lyrically, you can’t break it down much further than this. It’s already bare-bones.” Lyrically this can be felt in the poetic blur of the internal and external. These are political songs without political language. They explore the collective wounds of our Earth. Abstractions of the personal hint at war, environmental destruction, and the traumas that fuel it. Across the album, there are genuine attempts to point the listener towards the very real dangers that face our planet. When Adrianne sings “Please wake up,” she’s talking directly to the audience. Engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who were both behind U.F.O.F., capture the live energy as instinctually and honestly as possible. Sarlo teamed up with James Krivchenia to mix the album, where they sought to emphasize raw power and direct energy inherent in the takes. The journey of a song from the stage to the record is often a difficult one. Big Thief’s advantage is their bond and loving centre as a chosen family. They spend almost 100% of their lives together working towards a sound that they all agree upon. A band with this level of togetherness is increasingly uncommon. If you ask drummer James Krivchenia, bassist Max Oleartchik or guitarist Buck Meek how they write their parts, they will describe — passionately — the experience of hearing Adrianne present a new song, listening intently for hints of parts that already exist in the ether and the undertones to draw out with their respective instruments. With raw power and intimacy, Two Hands folds itself gracefully into Big Thief’s impressive discography. This body of work grows deeper and more inspiring with each new album.

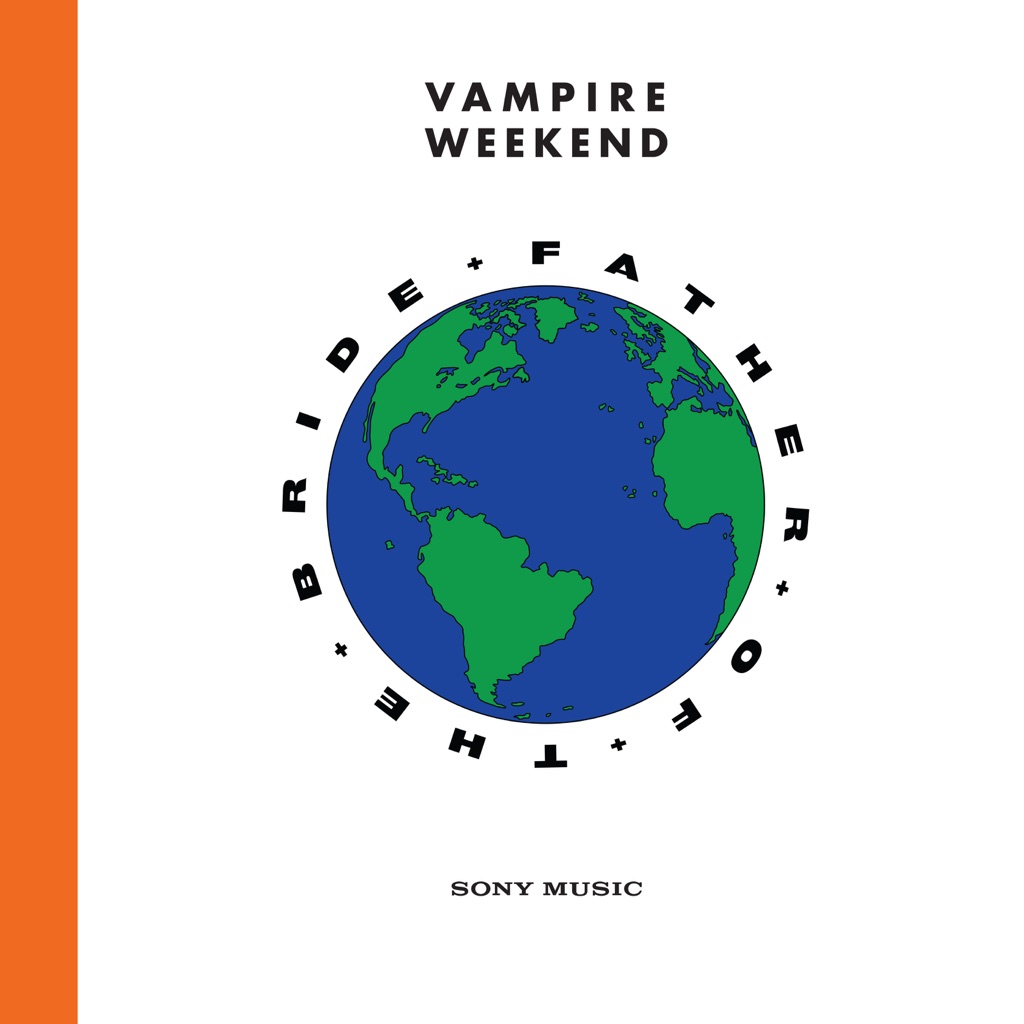

“It feels right that our fourth album is not 10, 11 songs,” Vampire Weekend frontman Ezra Koenig explains on his Beats 1 show *Time Crisis*, laying out the reasoning behind the 18-track breadth of his band\'s first album in six years. “It felt like it needed more room.” The double album—which Koenig considers less akin to the stylistic variety of The Beatles\' White Album and closer to the narrative and thematic cohesion of Bruce Springsteen\'s *The River*—also introduces some personnel changes. Founding member Rostam Batmanglij contributes to a couple of tracks but is no longer in the band, while Haim\'s Danielle Haim and The Internet\'s Steve Lacy are among the guests who play on multiple songs here. The result is decidedly looser and more sprawling than previous Vampire Weekend records, which Koenig feels is an apt way to return after a long hiatus. “After six years gone, it\'s a bigger statement.” Here Koenig unpacks some of *Father of the Bride*\'s key tracks. **\"Hold You Now\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “From pretty early on, I had a feeling that\'d be a good track one. I like that it opens with just acoustic guitar and vocals, which I thought is such a weird way to open a Vampire Weekend record. I always knew that there should be three duets spread out around the album, and I always knew I wanted them to be with the same person. Thank God it ended up being with Danielle. I wouldn\'t really call them country, but clearly they\'re indebted to classic country-duet songwriting.” **\"Rich Man\"** “I actually remember when I first started writing that; it was when we were at the Grammys for \[2013\'s\] *Modern Vampires of the City*. Sometimes you work so hard to come up with ideas, and you\'re down in the mines just trying to come up with stuff. Then other times you\'re just about to leave, you listen to something, you come up with a little idea. On this long album, with songs like this and \'Big Blue,\' they\'re like these short-story songs—they\'re moments. I just thought there\'s something funny about the narrator of the song being like, \'It\'s so hard to find one rich man in town with a satisfied mind. But I am the one.\' It\'s the trippiest song on the album.” **\"Married in a Gold Rush\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “I played this song for a couple of people, and some were like, \'Oh, that\'s your country song?\' And I swear, we pulled our hair out trying to make sure the song didn\'t sound too country. Once you get past some of the imagery—midnight train, whatever—that\'s not really what it\'s about. The story is underneath it.” **\"Sympathy”** “That\'s the most metal Vampire Weekend\'s ever gotten with the double bass drum pedal.” **\"Sunflower\" (feat. Steve Lacy)** “I\'ve been critical of certain references people throw at this record. But if people want to say this sounds a little like Phish, I\'m with that.” **\"We Belong Together\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “That\'s kind of two different songs that came together, as is often the case of Vampire Weekend. We had this old demo that started with programmed drums and Rostam having that 12-string. I always wanted to do a song that was insanely simple, that was just listing things that go together. So I\'d sit at the piano and go, \'We go together like pots and pans, surf and sand, bottles and cans.\' Then we mashed them up. It\'s probably the most wholesome Vampire Weekend song.”

Throughout their 15-year run, Glasgow, Scotland miserablists The Twilight Sad have skillfully walked a tightrope between sweeping post-rock and gleaming synth-rock. Led by James Graham’s impassioned brogue, *It Won/t Be Like This All the Time*, their fifth LP and first with Mogwai\'s Rock Action Records, retains their pummeling might, delving into the deepest corners of the soul with their darkest imagery yet. Taking cues from The Cure’s industrial-laced *Pornography* period—it serves to mention that Robert Smith is the band’s most effusive endorser—“The Arbor” and “\[10 Good Reasons for Modern Drugs\]” bring back the shrill synthesizers of 2012\'s *No One Can Ever Know*. “Are you not scared/I saw you kill him on the back stairs,” Graham threatens on the chilling “Shooting Dennis Hopper Shooting.” Forbidding words, for sure, but rarely are such sentiments accompanied with a sound that is this positively uplifting.

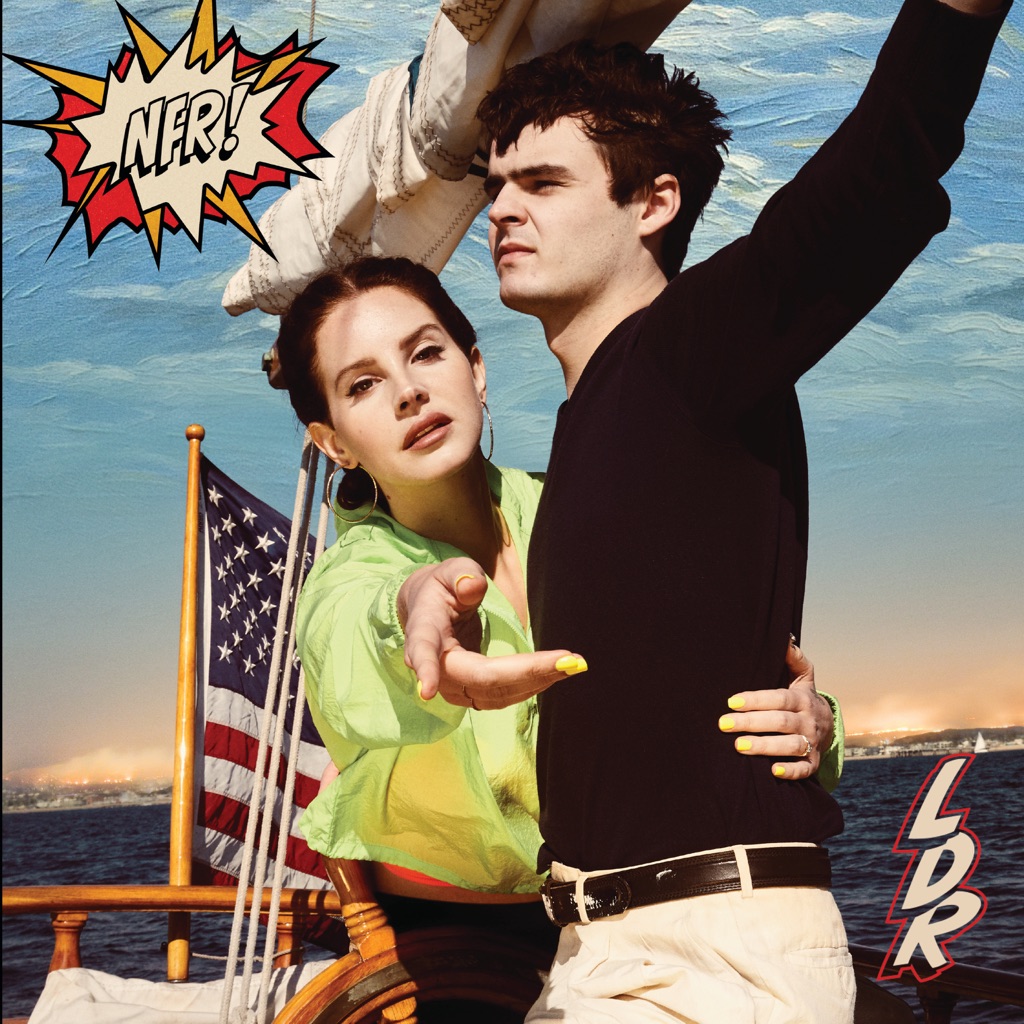

Part of the fun of listening to Lana Del Rey’s ethereal lullabies is the sly sense of humor that brings them back down to earth. Tucked inside her dreamscapes about Hollywood and the Hamptons are reminders—and celebrations—of just how empty these places can be. Here, on her sixth album, she fixes her gaze on another place primed for exploration: the art world. Winking and vivid, *Norman F\*\*\*\*\*g Rockwell!* is a conceptual riff on the rules that govern integrity and authenticity from an artist who has made a career out of breaking them. In a 2018 interview with Apple Music\'s Zane Lowe, Del Rey said working with songwriter Jack Antonoff (who produced the album along with Rick Nowels and Andrew Watt) put her in a lighter mood: “He was so *funny*,” she said. Their partnership—as seen on the title track, a study of inflated egos—allowed her to take her subjects less seriously. \"It\'s about this guy who is such a genius artist, but he thinks he’s the shit and he knows it,” she said. \"So often I end up with these creative types. They just go on and on about themselves and I\'m like, \'Yeah, yeah.\' But there’s merit to it also—they are so good.” This paradox becomes a theme on *Rockwell*, a canvas upon which she paints with sincerity and satire and challenges you to spot the difference. (On “The Next Best American Record,” she sings, “We were so obsessed with writing the next best American record/’Cause we were just that good/It was just that good.”) Whether she’s wistfully nostalgic or jaded and detached is up for interpretation—really, everything is. The album’s finale, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have - but I have it,” is packaged like a confessional—first-person, reflective, sung over simple piano chords—but it’s also flamboyantly cinematic, interweaving references to Sylvia Plath and Slim Aarons with anecdotes from Del Rey\'s own life to make us question, again, what\'s real. When she repeats the phrase “a woman like me,” it feels like a taunt; she’s spent the last decade mixing personas—outcast and pop idol, debutante and witch, pinup girl and poet, sinner and saint—ostensibly in an effort to render them all moot. Here, she suggests something even bolder: that the only thing more dangerous than a complicated woman is one who refuses to give up.

After the billowing, nearly gothic pop of 2016’s *Blood Bitch*—which included a song constructed entirely from feral panting—Norwegian singer-songwriter Jenny Hval makes the unlikely pivot into brightly colored synth-pop on *The Practice of Love*. Rarely has music so experimental been quite this graceful, so deeply invested in the kinds of immediate pleasure at which pop music excels. Conceptually and sometimes formally, the album can be as challenging as Hval’s thorniest work. The title track layers together a spoken-word soliloquy by Vivian Wang, the album’s chief vocalist, with an unrelated conversation between Hval and the Australian musician Laura Jean, so that resonant details—about hatred of love, the fragility of the ego, the decision not to have children—drift free of their original contexts and intertwine over a bed of ambient synths. But the bulk of the record is built atop a shimmering foundation of buoyant synths and sleek dance beats, with memories of ’90s trance and dream pop seeping into cryptic lyrics about vampires, thumbsuckers, and nuclear families. In “Six Red Cannas,” Hval makes a pilgrimage to Georgia O’Keeffe’s ranch in New Mexico, citing Joni Mitchell and Amelia Earhart as she meditates on the endless skies above. Her invocation of such feminist pioneers is fitting. Refusing to take even the most well-worn categories as a given, Hval reinvents the very nature of pop music.

At first listen, The Practice of Love, Jenny Hval’s seventh full-length album, unspools with an almost deceptive ease. Across eight tracks, filled with arpeggiated synth washes and the kind of lilting beats that might have drifted, loose and unmoored, from some forgotten mid-’90s trance single, The Practice of Love feels, first and foremost, compellingly humane. Given the horror and viscera of her previous album, 2016’s Blood Bitch, The Practice of Love is almost subversive in its gentleness—a deep dive into what it means to grow older, to question one’s relationship to the earth and one’s self, and to hold a magnifying glass over the notion of what intimacy can mean. As Hval describes it, the album charts its own particular geography, a landscape in which multiple voices engage and disperse, and the question of connectedness—or lack thereof—hangs suspended in the architecture of every song. It is an album about “seeing things from above—almost like looking straight down into the ground, all of these vibrant forest landscapes, the type of nature where you might find a porn magazine at a certain place in the woods and everyone would know where it was, but even that would just become rotting paper, eventually melting into the ground.” Prompted by an urge to find a different kind of language to express what she was feeling, the songs on Love unfurl like an interior dialogue involving several voices. Friends and collaborators Vivian Wang, Laura Jean Englert, and Felicia Atkinson surface on various tracks, via contributed vocals or through bits of recorded conversation, which further posits the record itself as a kind of ongoing discourse. “The last thing I wrote, which was my new book (forthcoming), had quite an angry voice,” says Hval, “The voice of an angry teenager, furious at the hierarchies. Perhaps this album rediscovers that same voice 20 years later. Not so angry anymore, but still feeling apart from the mainstream, trying to find their place and their community. With that voice, I wanted to push my writing practice further, writing something that was multilayered, a community of voices, stories about both myself and others simultaneously, or about someone’s place in the world and within art history at the same time. I wanted to develop this new multi-tracked writing voice and take it to a positive, beautiful pop song place... A place which also sounds like a huge pile of earth that I’m about to bury my coffin in.” Opening track “Lions” sets the tone for the record, both thematically and aesthetically, offering both a directive and a question: “Look at these trees / Look at this grass / Look at those clouds / Look at them now / Study this and ask yourself: Where is God?” The idea of placing ourselves in context to the earth and to others bubbles up throughout the record. On “Accident” two friends video chat on the topic of childlessness, considering their own ambivalence about motherhood and the curiosity of having been born at all. “She is an accident,” Hval sings, “She is made for other things / Born for cubist yearnings / Born to Write. Born to Burn / She is an accident / Flesh in dissent.” What does it mean to be in the world? What does it mean to participate in the culture of what it means to be human? To parent (or not)? To live and die? To practice love and care? What must we do to feel validated as living beings? Such questions are baked into the DNA of Love, wrapped up in layers of gauzy synthesizers and syncopated beats. Even when circling issues of mortality, there is a kind of humane delight at play. “Put two fingers in the earth,” Hval intones on “Ashes to Ashes”— “I am digging my own grave / in the honeypot / ashes to ashes / dust to dust.” Balanced against these ruminations on love, care and being, Hval employs sounds that are both sentimental and more than a little nostalgic. “I kept coming back to trashy, mainstream trance music from the ’90s,” she says, “It’s a sound that was kind of hiding in the back of my mind for a long time. I don’t mean trashy in a bad sense, but in a beautiful one. The synth sounds are the things I imagined being played at the raves I was too young and too scared to attend, they were the sounds I associated with the people who were always driving around the two streets in the town where I grew up, the guys with the big stereo in the car that was always just pumping away. I liked the idea of playing with trance music in the true transcendental sense, those washy synths have lightness and clarity to them. I think I’m always looking for what sounds can bring me to write, and these synths made me write very open, honest lyrics.” Though The Practice of Love was, in some sense, inspired by Valie Export’s 1985 film of the same name, for Hval the concept of love as a practice—as an ongoing, sustained, multivalent activity—provided a way to broaden and expand her own writing practice. Lyrically, the 8 tracks present here, particularly the title track, hew more closely to poetic forms than anything Hval has made before. (As evidenced by the record’s liner notes, which assume the form of a poetry chapbook.) Rather than shrink from the subject or try to overly obfuscate in some way, Love considers the notion of intimacy from all sides, whether it be positing the notion of art in conversation with other artists (“Six Red Cannas”) or playing with clichés around what it means to be a woman who makes art (“High Alice”), Hval’s songs attempt to make sense of what love and care actually mean—love as a practice, a vocation that one must continually work at. “This sounds like something that should be stitched on a pillow, but intimacy really is a lifelong journey,” she explains, “And I am someone who is interested in what ideas or practices of love and intimacy can be. These practices have for me been deeply tied to the practice of otherness, of expressing myself differently from what I’ve seen as the norm. Maybe that's why I've mostly avoided love as a topic of my work. The theme of love in art has been the domain of the mainstream for me. Love is one of those major subjects, like death and the ocean, and I’m a minor character. But in the last few years I have wanted to take a closer look at otherness, this fragile performance, to explore how it expresses love, intimacy, and kindness. I've wanted to explore how otherness deals with the big, broad themes. I've wanted to ask big questions, like: What is our job as a member of the human race? Do we have to accept this job, and if we don’t, does the pressure to be normal ever stop?” It’s a crazy ambition, perhaps, to think that something as simple as a pop song can manage, over the course of two or three minutes, to chisel away at some extant human truth. Still, it’s hard to listen to the songs on The Practice of Love and not feel as if you are listening in on a private conversation, an examination that is, for lack of a better word, truly intimate. Tucked between the beats and washy synths, the record spills over with slippery truths about what it is to be a human being trying to move through the world and the ways—both expected and unexpected—we relate to each other. “Outside again, the chaos / and I wonder what is lost,” Hval sings on “Ordinary,” the album’s closing track, “We don’t always get to choose / when we are close / and when we are not.”

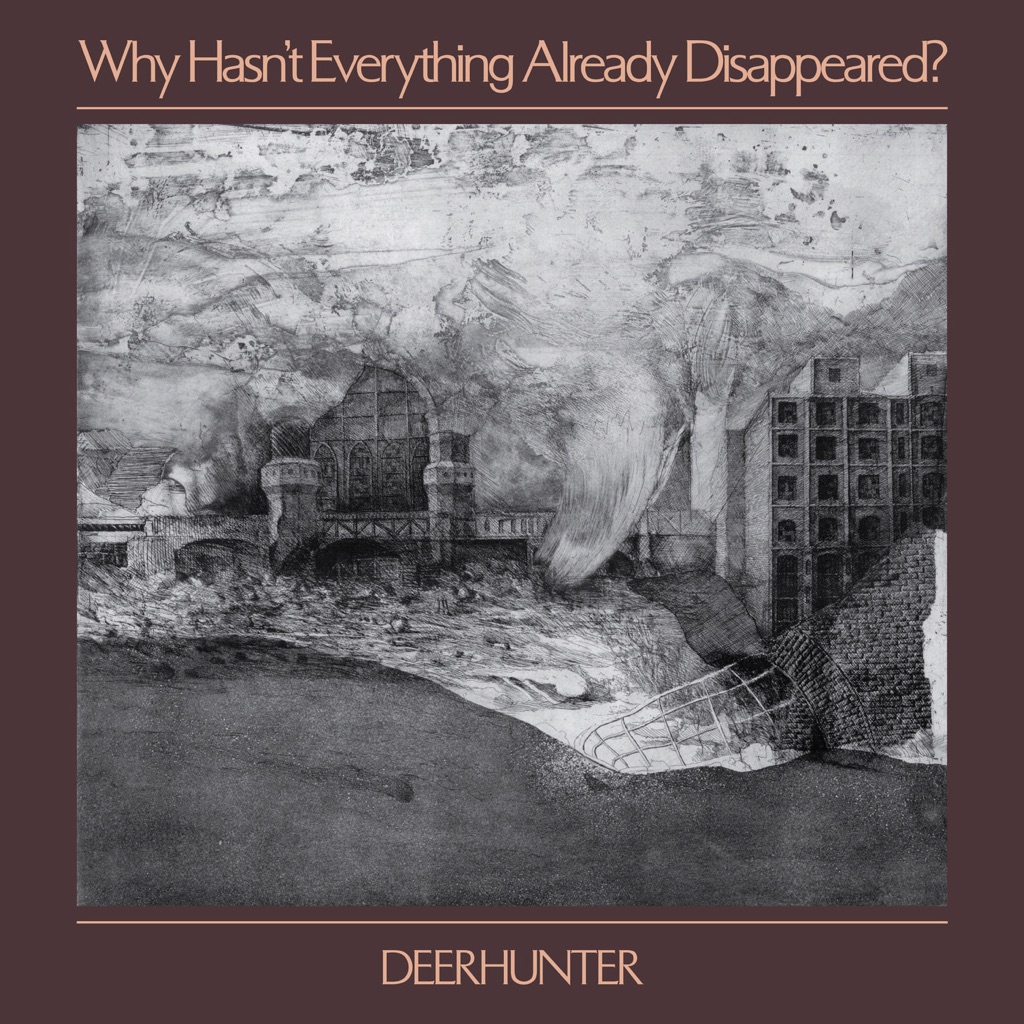

The Atlanta band’s eighth full-length finds iconoclastic frontman Bradford Cox and co. shrinking their typically ambient-focused sound, with relatively compact guitar-pop gems alongside haunting, weightless-sounding instrumentals. Featuring contributions from Welsh singer-songwriter Cate Le Bon and Tim Presley of garage-popsters White Fence, *Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?* diverges from the deeply personal themes of previous Deerhunter albums, zeroing in on topics ranging from James Dean (“Plains”) to the tragic murder of British politician Jo Cox (“No One’s Sleeping”)—but the spectral vocals and penchant for left-field sounds are well accounted for, as the album represents the latest strange chapter in one of modern indie rock’s most consistently surprising acts.

In some ways, Aldous Harding’s third album, *Designer*, feels lighter than her first two—particularly 2017’s stunning, stripped-back, despairing *Party*. “I felt freed up,” Harding (whose real name is Hannah) tells Apple Music. “I could feel a loosening of tension, a different way of expressing my thought processes. There was a joyful loosening in an unapologetic way. I didn’t try to fight that.” Where *Party* kept the New Zealand singer-songwriter\'s voice almost constantly exposed and bare, here there’s more going on: a greater variety of instruments (especially percussion), bigger rhythms, additional vocals that add harmonies and echoes to her chameleonic voice, which flips between breathy baritone and wispy falsetto. “I wanted to show that there are lots of ways to work with space, lots of ways you can be serious,” she says. “You don’t have to be serious to be serious. I’m not a role model, that’s just how I felt. It’s a light, unapologetic approach based on what I have and what I know and what I think I know.” Harding attributes this broader musical palette to the many places and settings in which the album was written, including on tour. “It’s an incredibly diverse record, but it somehow feels part of the same brand,” she says. “They were all written at very different times and in very different surroundings, but maybe that’s what makes it feel complete.” The bare, devastating “Heaven Is Empty” came together on a long train ride and “The Barrel” on a bike ride, while intimate album closer “Pilot” took all of ten minutes to compose. “It was stream of consciousness, and I don’t usually write like that,” she says. “Once I’d written it all down, I think I made one or two changes to the last verse, but other than that, I did not edit that stream of consciousness at all.” The piano line that anchors “Damn” is rudimentary, for good reason: “I’m terrible at piano,” she says. “But it was an experiment, too. I’m aware that it’s simple and long, and when you stretch out simple it can be boring. It may be one of the songs people skip over, but that’s what I wanted to do.” The track is, as she says, a “very honest self-portrait about the woman who, I expect, can be quite difficult to love at times. But there’s a lot of humor in it—to me, anyway.”

Aldous Harding’s third album, Designer is released on 26th April and finds the New Zealander hitting her creative stride. After the sleeper success of Party (internationally lauded and crowned Rough Trade Shop’s Album of 2017), Harding came off a 200-date tour last summer and went straight into the studio with a collection of songs written on the road. Reuniting with John Parish, producer of Party, Harding spent 15 days recording and 10 days mixing at Rockfield Studios, Monmouth and Bristol’s J&J Studio and Playpen. From the bold strokes of opening track ‘Fixture Picture’, there is an overriding sense of an artist confident in their work, with contributions from Huw Evans (H. Hawkline), Stephen Black (Sweet Baboo), drummer Gwion Llewelyn and violinist Clare Mactaggart broadening and complimenting Harding’s rich and timeless songwriting.

“I think everybody was ready to take a hiatus, pull the shades down for a year or so,” The National frontman Matt Berninger tells Apple Music of his band’s state of mind at the end of their tour for 2017’s Grammy-winning *Sleep Well Beast*. “Everyone in the band was exhausted and had no intention of diving back into a record at all. But Mike Mills showed up and had an idea, and then the idea just kept getting more exciting.” Mills—the Oscar-nominated writer and director behind *20th Century Women*, and not, it can’t be stressed enough, the former R.E.M. bassist—reached out to Berninger with the intention of maybe directing a video for the band, but that soon blossomed into a much more ambitious proposition: Mills would use some tracks that didn’t find their way onto *Sleep Well Beast* as the springboard for a short film project. That film—also called *I Am Easy to Find*—features Oscar winner Alicia Vikander portraying a unnamed woman from birth to death, a life story told in picaresque black-and-white subtitled snippets, to the swells of The National’s characteristically dramatic music. Those subtitles in turn informed new songs and inspired the band to head from touring straight into making another full album, right when they should have had their toes in sand. “All the song bits and lyric ideas and emotional places and stuff that we were deep into all went into the same big crock pot,” Berninger says. “We knew there would be a 25-minute film and a record, but it\'s not like one was there to support or accompany the other.” Just as the film is about nothing more and nothing less than an examination of one person’s entire existence, the album is The National simultaneously at their most personal and most far-flung. Don’t be fooled by the press photos showing five guys; though the band has been increasingly collaborative and sprawling over its two-decade run, never has the reach of the National Cinematic Universe been so evident. Berninger is still nominally the lead singer and focal point, but on none of the album’s 16 tracks is he the *only* singer, ceding many of the album’s most dramatic moments to a roster of female vocalists including Gail Ann Dorsey (formerly of David Bowie’s band), Sharon Van Etten, Kate Stables of This Is the Kit, Lisa Hannigan, and Mina Tindle, with additional assists from the Brooklyn Youth Chorus. Berninger’s wife Carin Besser, who has been contributing lyrics to National songs for years, had a heavier hand. Mills himself serves as a hands-on producer, reassembling parts of songs at will with the band’s full blessing, despite never having done anything like that before in his life. Despite this decentralization, it still feels like a cohesive National album—in turns brooding and bombastic, elegiac and euphoric, propelled by jittery rhythms and orchestral flourishes. But it is also a busy tapestry of voices and ideas, all in the name of exploring identity and what it means to be present and angry and bewildered at a tumultuous time. “There\'s a shaking off all the old tropes and patterns and ruts,” Berninger says. “Women are sick and tired of how they are spoken about or represented. Children are rebelling against the packages that they\'re forced into—and it\'s wonderful. I never questioned the package that I was supposed to walk around in until my thirties.” The album’s default mood is uneasy lullaby, epitomized by the title track, “Hairpin Turns,” “Light Years,” and the woozily logorrheic, nearly seven-minute centerpiece “Not in Kansas.” This gravity makes the moments that gallop, relatively speaking—“Where Is Her Head,” the purposefully gender-nonspecific “Rylan,” and the palpitating opener “You Had Your Soul with You”—feel all the more urgent. The expanded cast might be slightly disorienting at first, but that disorientation is by design—an attempt to make the band’s music and perspective feel more universal by working in concert with other musicians and a film director. “This is a packaging of the blurry chaos that creates some sort of reflection of it, and seeing a reflection of the chaos through some other artist\'s lens makes you feel more comfortable inside it,” says Berninger. “Other people are in this chaos with me and shining lights into corners. I\'m not alone in this.”

On 3rd September 2017, director Mike Mills emailed Matt Berninger to introduce himself and in very short order, the most ambitious project of the National’s nearly 20-year career was born and plans for a hard-earned vacation died. The Los Angeles-based filmmaker was coming off his third feature, 20th Century Women, and was interested in working with the band on... something. A video maybe. Berninger, already a fan of Mills’ films, not only agreed to collaborate, he essentially handed over the keys to the band’s creative process. The result is I Am Easy to Find, a 24-minute film by Mills starring Alicia Vikander, and I Am Easy to Find, a 68-minute album by the National. The former is not the video for the latter; the latter is not the soundtrack to the former. The two projects are, as Mills calls them, “Playfully hostile siblings that love to steal from each other” -- they share music and words and DNA and impulses and a vision about what it means to be human in 2019, but don’t necessarily need one another. The movie was composed like a piece of music; the music was assembled like a film, by a film director. The frontman and natural focal point was deliberately and dramatically sidestaged in favour of a variety of female voices, nearly all of whom have long been in the group’s orbit. It is unlike anything either artist has ever attempted and also totally in line with how they’ve created for much of their careers. As the album’s opening track, ‘You Had Your Soul With You,’ unfurls, it’s so far, so National: a digitally manipulated guitar line, skittering drums, Berninger’s familiar baritone, mounting tension. Then around the 2:15 mark, the true nature of I Am Easy To Find announces itself: the racket subsides, strings swell, and the voice of long-time David Bowie bandmate Gail Ann Dorsey booms out—not as background vocals, not as a hook, but to take over the song. Elsewhere it’s Irish singer-songwriter Lisa Hannigan, or Sharon Van Etten, or Mina Tindle or Kate Stables of This Is the Kit, or varying combinations of them. The Brooklyn Youth Choir, whom Bryce Dessner had worked with before. There are choral arrangements and strings on nearly every track, largely put together by Bryce in Paris—not a negation of the band’s dramatic tendencies, but a redistribution of them. “Yes, there are a lot of women singing on this, but it wasn't because, ‘Oh, let's have more women's voices,’ says Berninger. “It was more, ‘Let's have more of a fabric of people's identities.’ It would have been better to have had other male singers, but my ego wouldn't let that happen."

There’s something almost startlingly disarming about the way Stella Donnelly can convey such immense, moving messages in songs typically anchored by bright, gentle vocals and acoustic guitars. The Western Australian singer-songwriter first made her mark in 2017 with “Boys Will be Boys,” a powerful song that is, despite its sweet melody, an all-out attack on the culture of sexual assault victim-blaming. Two years later, her debut album is a melodic collection of guitar-based songs that directly address toxic masculinity, abuse, white Australia, and the breakdown of a relationship. Of course, *Beware of the Dogs* isn’t *all* doom and gloom, but happy songs aren’t necessarily Donnelly’s cup of tea. “I struggle to write about the flowers and the birds and the bees and the blue skies,” she tells Apple Music. “There\'s gotta be a bit of grit in there somewhere.” Read about the stories and meaning behind each song on the album below. **“Old Man”** “It was really important to me that I came out with a strong statement on the first song. After putting out ‘Boys Will Be Boys,’ I received so much love, but I also got challenged by a lot of people. I had to make a decision that I wasn\'t going to back away in fear, I was going to come out, guns blazing, middle finger up. It’s my way of making sure listeners knew I wasn’t moving away from that activism or outspokenness.” **“Mosquito”** “This is probably the only love song I\'ll ever write. I find myself having to say ‘Sorry, mum’ after singing it live, sometimes. The vibrator line is the only way I could really express my love for someone. It had to be a little bit crass. It’s hard to find a way of speaking about love that isn\'t too optimistic.” **“Season’s Greetings”** “I wanted to paint a picture of a Christmas party gone wrong, where you\'re forced into a small space with people who you generally spend the rest of the year avoiding. It’s a chance to learn a little bit about ourselves, if not about someone else.” **“Allergies”** “I actually had a breakup the day I recorded this. You can hear it in my voice. I\'m all choked up and snotty and crying, and my two best friends were sitting on the couch with fried chicken, chocolate, and tissues for when I finished the song. It\'s not perfect. Some bits are shaky. But in terms of getting across that mood and that truth, I wouldn’t change anything.” **“Tricks”** “It\'s a bit of a joke song about the people who heckled me when I used to play covers. I\'d be singing ‘Wonderwall’ for the 50th time that week and then someone would yell, ‘Play Cold Chisel! Play “Khe Sanh”!’ Every weekend they’d heckle me, I’d finally play Crowded House and they\'d be happy. That\'s what I mean by the tricks. They only liked me when I played what they wanted.” **“Boys Will Be Boys”** “It was a last-minute decision to put this on the record, because it came out on the EP in 2017. Unfortunately, I feel like its message still needs to come through and be heard by more people. I spoke to my dad about it and he said, ‘A lot of people have heard that song, but a lot more people haven\'t heard that song.’ It\'s still painful to perform, it challenges me and feels powerful to be speaking out. Certain songs lose the weight they had when you first wrote it. ‘Boys Will Be Boys’ hasn\'t changed.” **“Lunch”** “It was originally meant to be just me and an acoustic guitar. One day I was playing these random chords, and my bass player, Jenny, was playing really low notes on the guitar. We ended up adding drums, keyboard, cello, and it became this beautiful thing. My guitarist, George, had the idea for the drums. He stood in the middle of the room with a snare and a tom—not even the whole drum kit—and made the part. We were all on the other side of the room cheering him on! It was a really special moment.” **“Bistro”** “‘Bistro’ was actually originally a full song with a chorus, bridge, and everything, but I was struggling to tell the story that I was trying to tell. So I cut lines and just repeated the same lyrics over and over again. It was all I needed to say, really.” **“Die”** “I wrote ‘Die’ initially because I wanted a song that I could go jogging to. None of my music is very joggable. I’ll tell you what, though: I haven’t gone jogging once since putting out the song. So that didn\'t work out very well.” **“Beware of the Dogs”** “It’s about Australian identity and what that actually means for me, as an Anglo, white Australian, and how my experience of this country can differ so much from somebody else\'s based on that privilege. It also looks at the people in power, who have all the money and protect it at the expense of others. I guess I\'m just trying to use this platform to speak up.” **“U Owe Me”** “This one\'s about my old boss at a pub I used to work at back home. Three or four years ago, I was literally pouring flat VB into warm cups. It was a real bleak scenario, but I got so many great experiences from that.” **“Watching Telly”** “I wrote this song after arriving in Dublin on the day that they voted in the right for women to seek a legal abortion. It was really scary. There were \'No\' signs everywhere, lots of protests. I felt so much for the women who had to see these signs questioning the right to make their own decisions for their bodies. I just found it so troubling that there was still such a question about that freedom.” **“Face It”** “There’s a narrative throughout the album about a relationship breakdown, and I wanted to finish by drawing the line in the sand, moving on from that experience, and going into the next record with something new. It’s my closing speech.”

Marika Hackman’s second album, 2017’s *I’m Not Your Man*, gave the English singer-songwriter a lot to reflect on. “Being so open about my sexuality and having a response from young women saying it helped them to realize who they are and come out—that isn’t something that just washes over you,” she tells Apple Music. “I hold that in my heart and it’s very much a driving force.” That momentum can be felt throughout Hackman’s third album as she explores sex between two women (“all night”), inhabiting the mind of her ex to confront a breakup (“send my love”), and masturbation (“hand solo”) with bracing candor and propulsive synths. “Coming to this record I thought, ‘All right. I’ll do it, I\'ll be more open.’” Let Hackman guide you through her darkly comic journey of what it means to be human, track by track. **“wanderlust”** “I wrote this song in a matter of hours, and this is the first recording ever of it. It’s just me at the kitchen table with the mic on a pair of Apple headphones, the old ones. It’s been sitting in my bank for a while; I didn’t want it on the last album because it felt too similar to my first and I wanted to pull away from that. When I wrote ‘the one’ \[the following track\], it felt like this would be the perfect opener to lull the listener into a false sense of security about where I’d gone with my music this time around, like, ‘Oh, it’s the old Marika that I know and love.’” **“the one”** “This is the first song I wrote specifically for this album. It really set the tone and surprised me. I deal with a lot through humor; I think it’s a good way of connecting with people. It invites them in. The track was born out of feeling frustrated: I’ve been doing this for a long time and sometimes I wish I was bigger. It was taking that as a concept and exaggerating the fuck out of it to make this big joke. I don’t like this part of myself—I don’t like being frustrated or jealous—so I wanted to push that feeling as far as I could. I turned it into something external that I can sit back and laugh at.” **“all night”** “The intention with this song was to openly explore sex between two women in a celebratory, honest way. Because that’s my experience of sex, so that’s the only way I can talk about it. The whole ‘kissing, eating, fucking, moaning’ part, that was saved in the notes on my phone for a really long time. I get a lot of ideas when I’m on buses if I’ve been on a night out. I had this idea about describing your mouth as being something just for eating and moaning. Then you flip that and the eating becomes the fucking and kissing and moaning. I like wordplay and to pretend it’s going somewhere then take you somewhere else.” **“blow”** “I wanted every instrument to have a purpose in the part that it was playing, not just be a wash of color or for some atmosphere. On this track there’s funky basslines interlocking with wild drum parts and then a space where the jagged, gnarly guitar lines stick out. I’ve never written like that before, and I think that’s because my confidence in playing guitar has really jumped up in the last couple of years from touring.” **“i’m not where you are”** “One of the fans summed this up perfectly: ‘It’s the anthem for the emotionally detached that we never had before.’ That was exactly what I was aiming to do, but I hadn’t put it in those words. There’s an aloofness that people often attribute to being unavailable that’s kinda sexy and cool. And it’s not at all. It’s horrible to feel like you can’t just let go and throw yourself into something because of fear. You often hear songs about people who are so hard to get; I wanted to write it from the other perspective of someone who’s like, ‘I don’t know how to connect. I don’t feel on the same level as most people I meet.’ That’s very lonely.” **“send my love”** “This is about the end of a relationship with my ex, Amber \[of The Japanese House\], and it’s me inhabiting her. I was using her character as the mouthpiece for me to say how I was feeling about myself when we were breaking up. I can only share my experience by saying, ‘This must be how you feel about me right now because this is how I feel about myself.’ And then she listens to it and thinks the lyrics are really sad, because she was like, ‘That’s not how I view you or ever viewed you.’ The lyrics are pretty brutal. There’re all of those elements of nostalgia and regret—that’s what happens when things come to an end. When I listen to the song, I can feel that streak of self-loathing, self-hatred, and sadness, but it’s just a moment in time. That was how I was feeling then, and things change. We’re like best friends now.” **“hand solo”** “One lyric that will get overlooked because I don’t think many people are gonna understand the reference, but the first half of the song is looking at old wives’ tales about masturbation. One of them I read is that you get hairy hands if you masturbate too much. There’s a line in there that says, ‘Oh, monkey glove’—it’s talking about having hairy hands. It’s quite abstract but it sounds sexual as well. It sounds like something you might call your vagina. And it’s quite gross, that song. ‘Dark meat, skin pleat’—it’s all quite visceral. My favorite lyric is obviously ‘Under patriarchal law, I’m gonna die a virgin.’ That is insane, that is crazy! I feel like people don’t take my sexual experiences as real. The song is also a massive fuck-you, because it’s very funny and empowered with a bit of sass.” **“conventional ride”** “This song is about that classic thing where you feel like a straight girl might think she’s into it, but she’s fulfilling some sort of fantasy. Which is fine—that’s something that should be explored—but it’s about being open and honest about that with whoever you’re sleeping with. This is about me being like, ‘Maybe you just need a conventional ride. You’re not really into this. You started off thinking you were, but you’re pulling me along.’ The song has that feeling of momentum, being pulled along by something when it’s not quite right.” **“come undone”** “I was listening to a lot of Crumb and I thought, ‘They’ve got some funky basslines. I wanna write a funky bassline!’ That’s often how a lot of my creative process starts: ‘I wanna do that too.’ Like a petulant child! I wrote the bassline and I thought there’s not enough room for anything to go over the top of this, but I kept with it and wrote a nice drum beat that locked in with this. It’s pretty simple, letting that bassline sing with a flourish of guitar pulling your attention left and right.” **“hold on”** “This song was written on a little MIDI keyboard. I’d never written a song like that before. I went for something a bit like Massive Attack or Radiohead, and it swept off into this big beast that I didn’t really anticipate. It’s a sad song; I was going through a really severe bout of depression that I hadn’t felt intensely before. Maybe that’s why the lyrics don’t make that much sense. It’s like a big exhale. I think I might explore that style of writing a bit more—that was my first foray, and it would be exciting to see if I can do a bit more electronic.” **“any human friend”** “I knew immediately this was going to be the last song on the record because it has this optimism to it. It’s a moment to just breathe and let it wash over you. There’s a very conscious decision right at the end when the acoustic guitar comes in repeating the riff ’til it floats away to bring it back to how ‘wanderlust’ starts and lands it again back into the real world. On this album there’s quite a lot of psychedelic segues between the songs and there’s not much room to breathe; it’s quite intense. Then it spits you out and there’s this tiny little anchor at the end, pulling you back into the room.”