The musician born Josh Tillman chose the title for his sixth album in a decidedly Father John Misty kind of way: He found the Sanskrit word in a novel by Bruce Wagner, who shares with the musician a certain impish LA mysticism. Mahāśmaśāna translates to “great cremation ground,” so it’s no surprise to find the singer-songwriter in “what’s it all mean?” mode, trawling tragicomic corners of the American Southwest in search of answers about life, death, and humanity. After trying his hand at big-band jazz on 2022’s *Chloë and the Next 20th Century*, Tillman returns to the big, sweeping ’70s-style pop rock that’s earned him a place among his generation’s most intriguing songwriters. He channels Leonard Cohen’s *Death of a Ladies’ Man* on the sprawling title track, whose swooning orchestration and ambitious lyrics take stock of, well, everything. “She Cleans Up” tells a rollicking tale involving female aliens, high-dollar kimonos, and rabbits with guns, and on dystopian power ballad “Screamland,” he offers an all-American refrain: “Stay young/Get numb/Keep dreaming.”

The indie-pop band fronted by Michelle Zauner released their third album, 2021’s *Jubilee*, to massive critical acclaim and their first Grammy nomination. After spending five years writing *Crying in H Mart*, her best-selling memoir about grief, Zauner devoted the record to joy and catharsis, all triumphant horns and swooning synths. But for its follow-up, the ambitious polymath found herself drawn to darker, knottier themes—loneliness, desire, contemporary masculinity. She also gravitated to the indie-rock sounds of her past, recruiting producer and guitarist Blake Mills, known for his work with artists like Fiona Apple, Feist, and Weyes Blood. “\[For *Jubilee*\] we wanted to have bombastic, big instrumentation with lots of strings and horns; I wanted this to come back to a more guitar-oriented record,” Zauner tells Apple Music. “I think I’m going back to my roots a little bit more.” When she began to write the band’s fourth record in 2022, Zauner found inspiration in an unlikely literary juxtaposition: Greek mythology, gothic romance classics, and works that she wryly deemed as part of the “incel canon” à la Bret Easton Ellis’ *American Psycho*. From such seemingly disparate sources emerged the gorgeously bleak songs of *For Melancholy Brunettes (& sad women)*, whose title is presented with an implied wink, acknowledging the many women songwriters whose work is reduced to “sad girl music.” Indeed, the atmosphere on *For Melancholy Brunettes* is less straightforwardly sad, and more…well, it’s complicated. On “Leda,” the story of a strained relationship unfolds by way of Greek myths in which Zeus takes the form of a swan to seduce a Spartan queen. “Little Girl,” a deceptively sweet-sounding ballad about a father estranged from his daughter, opens with a spectacularly abject image: “Pissing in the corner of a hotel suite.” And on the fascinatingly eerie “Mega Circuit,” on which legendary drummer Jim Keltner lays down a mean shuffle, Zauner paints a twisted tableau of modern manhood—muddy ATVs, back-alley blowjobs, “incel eunuchs”—somehow managing to make it all sound achingly poetic with lines like, “Deep in the soft hearts of young boys so pissed off and jaded/Carrying dull prayers of old men cutting holier truths.” The universe Zauner conveys on *For Melancholy Brunettes* is sordid and strange, though not without beauty in the form of sublime guitar sounds or striking turns of phrase. (“I never knew I’d find my way into the arms/Of men in bars,” she sings on the wistful “Men in Bars,” which includes the album’s only feature from…Jeff Bridges?!) As for the title’s bone-dry humor—sardonically zesty castanet and tambourine add extra irony to “Winter in LA,” on which Zauner imagines herself as a happier woman, writing sweet love songs instead of…these.

Ichiko Aoba has come into her own as one of Japan’s most vital artists since debuting at 19 years old, with her boundless curiosity and musical versatility only growing as her career has progressed. On *Luminescent Creatures*, she casts her gaze toward the sea, channeling its moments of tumult and peace into 11 meticulously crafted songs that glow with awe. Ichiko and her chief collaborator, pianist and composer Taro Umebayashi, deftly lead an ensemble through the Kyoto-raised Ichiko’s brief yet complex compositions, on which she shows her precisely honed instincts for employing both airy minimalism and oceanic grandeur. “COLORATURA” rises and falls like waves, its circling flutes and cascading piano propelling her whispered voice into a tangle of strings; on “Lucifèrine,” she creates a mille-feuille of her own voice, bringing to full brightness the “light deep within the soul” marveled over in her lyrics. *Luminescent Creatures* shows how Ichiko has evolved—not just as an artist, but as an observer of the natural world over the last 15 years.

Alex G’s cryptic, heartfelt indie rock has earned him friends in interesting places: He contributed guitar and arrangements to Frank Ocean’s *Endless* and *Blonde*, he co-wrote and produced about half of Halsey’s *The Great Impersonator*, he’s toured with Foo Fighters, and he soundtracked Jane Schoenbrun’s 2024 movie *I Saw the TV Glow*—a movie that, like G’s music, seemed almost instantly destined to be a cult classic, playing with nostalgia for early-’90s pop culture in ways that felt both comforting and deeply unsettling. He’s not a household name, but he touches a nerve. His first major-label album (whatever that really means in 2025), *Headlights*, isn’t different from his run of Domino albums (2015’s *Beach Music* to 2022’s *God Save the Animals*) in kind so much as in degree. “Every couple weeks, I’d have a new song and just start working on it,” he tells Apple Music. “And then, at the end of a couple of years, I guess I had these 12 songs that were good.” The conventional tracks are more straightforward (the early Wilco stomp of “Logan Hotel”), the experiments are both bolder and catchier (the Auto-Tuned hyperpop of “Bounce Boy”). For an artist who can pull deep feeling out of vague stretches of sound, he’s gotten incredibly good at knowing how to use detail and when: Just listen to the accordion that seeps into “June Guitar” or the girls’ chorus that drifts in and out of the alien-abduction/high-school-football story (yes) “Beam Me Up”—touches that feel both unexpected and irreplaceable. The result is an album that feels less like a collection of indie-rock songs than a dream about collections of indie-rock songs—vivid but patchy, intimate but abstract, emotionally deep but totally indirect. In some ways, he’s just another point on the continuum of artists like Pavement or The Velvet Underground, both of whom managed to balance directness with abstraction, shadow with light. In others, he feels perfectly made for his moment, an enigmatically normal-seeming guy whose gift for melody and cool fragments of sound work as well as background vibes for chill times as hermetic texts left to be parsed by comment-section scholars. There’s a reason his fans latch on so tight: Like a good dream, Alex G points toward mystery.

The remarkable thing about Mike Hadreas’ music is how he manages to fit such big feelings into such small, confined spaces. Like 2020’s *Set My Heart on Fire Immediately*, 2025’s *Glory* (also produced by the ever-subtle but ever-engaging Blake Mills) channels the kind of gothic Americana that might soundtrack a David Lynch diner or the atmospheric opening credits of a show about hot werewolves: a little campy, a little dark, a lot of passions deeply felt. The bold moments here are easy to grasp (“It’s a Mirror,” “Me & Angel”), but it’s the quieter ones that make you sit up and listen (“Capezio,” “In a Row”). Once he found beauty in letting go, now he finds it in restraint.

For over two decades, Natalia Lafourcade’s catalog has showcased her magnificent voice across a variety of styles, both as a stunning soloist and at the helm of skilled ensembles. Reuniting with her *De Todas las Flores* co-producer Adan Jodorowsky, the Veracruz-raised singer-songwriter taps into her home region’s musical history while drawing upon her wider discography for *Cancionera*. Perhaps most impressively, she recorded it entirely in one take, a feat that becomes more and more meaningful as the album persists. After a tone-setting instrumental introduction, she begins to shape the album’s fantastical broad narrative with the title track, portraying herself as an almost supernatural spirit of song. What follows is a series of memorable moments like the rumba-y-mezcal-enhanced “El Palomo y La Negra” and the fragile yet firm “Mascaritas de Cristal,” as well as moving duets like “Como Quisiera Quererte” with El David Aguilar and “Amor Clandestino” with flamenco singer Israel Fernández.

Like the so-called slackers of early-’90s alt-rock (Beck, Pavement, etc.), Mac DeMarco’s sleight of hand is to make beautiful music without apparently trying—a chiller so chill he doesn’t write songs so much as wait for them to come snuggle up in his lap. *Guitar* is his most quietly striking album since the landmark *Salad Days*, stripping the slimy synth textures and bubbling drum machines out of his early sound to reveal sparse, paper-thin soft rock whose eerie melodies and gently jazzy chord progressions have more in common with ’40s-era pop like The Ink Spots and The Platters than anything from the underground (“Sweeter,” “Nightmare”). “Miracle, reveal yourself to me,” he sings at the beginning of “Holy,” channeling the meditative stillness of a John Lennon demo or early-’70s Al Green. It might sound wimpy at first. Then you realize a sound so naked and dry leaves him nowhere to hide. That’s strength.

The Florida-born singer-songwriter’s 2022 debut album, *Preacher’s Daughter*, was not exactly standard pop fare—a Southern Gothic odyssey steeped in themes of original sin and family trauma, whose fictional protagonist (spoiler alert) dies at the end. Nevertheless, the album broke through to the mainstream, even cracking the Top 10 of the Billboard 200 following its vinyl reissue this spring. Her long-awaited second album, January 2025’s *Perverts*, sat somewhere between passion project and provocation; its 90 minutes of eerie ambient collages seemed designed to challenge fans, if not shake them off entirely. Eight months later, Cain’s third album revisits the narrative that began with *Preacher’s Daughter*, whose centerpiece, “A House in Nebraska,” is a melancholy ode to Willoughby Tucker, the protagonist’s first love. *Willoughby Tucker, I’ll Always Love You* functions as a *Preacher’s Daughter* prequel—a story of two young, damaged lovers for whom doom is a powerful aphrodisiac. “I can see the end in the beginning of everything,” she sings on the reverb-drenched “Janie” before concluding grimly: “It’s not looking good.” Between sprawling ambient-folk stunners like “Nettles” and “Tempest,” Cain slips in a handful of moody instrumental interludes à la *Perverts* and a pair of fan favorites initially released as demos: “Dust Bowl,” a staple of her live sets for years, and the 15-minute “Waco, Texas,” for those who like their slow-dance numbers with a hearty dose of fatalism and a sprinkle of ’90s cult lore. Fitting for a concept album set in 1986, there’s also “Fuck Me Eyes,” a synth-pop power ballad starring a hell-raising, denim-wearing angel.

Samia’s third album, *Bloodless*, sounds as if someone’s opened a nearby window, allowing for a gush of fresh air to carry Samia Finnerty’s voice into the skies. The 28-year-old Minneapolis-based singer-songwriter’s follow-up to 2023’s *Honey* feels lithe and buoyant even at its most emotionally weighty. At times—the slinky “Lizard,” the echo-laden swell of “Sacred,” the thicket of woodwinds and vocals that run through closing track “Pants”—Samia recalls the ethereal New Wave of British pop-rock phenom The Japanese House, or the timeless bounce of Fleetwood Mac. At the center of such gestures is Samia’s close-to-the-bone lyricism, which continues to convey her pitch-perfect sly humor; atop the stormy strums and electronic frissons of “North Poles,” she wraps her bell-clear voice around evocations of “spyware lipstick” and fistfuls of natural wine before lobbing a grenade of reflection at the listener’s feet: “When you see yourself in someone/How can you look at them?”

“Ultimately—and I only discovered this after the whole album was written—this album is about opening yourself up to a lover, or a person, or the entire world, giving them every single part of yourself,” Laufey tells Apple Music about her third album, *A Matter of Time*. “It’s about acknowledging that it’s just a matter of time until you find out every single part of me.” She began working on the project while touring behind her breakthrough album *Bewitched* in 2024, inspired by a host of factors—particularly balancing her hectic schedule as an in-demand pop star with falling in love for the first time. Laufey worked on *A Matter of Time* with her longtime collaborator Spencer Stewart and new creative partner Aaron Dessner (of The National and Big Red Machine, and a regular collaborator of Taylor Swift’s). “It was that new experience that I was craving for an album,” she says. “I wanted to be so careful for this album about staying true to myself, and staying true to my roots, and staying true to my philosophy, which is ultimately keeping jazz music and classical music alive through my own music. But I was craving a level of speed and shine and newness for this album, and I knew I had to find one partner to work with who would bring that out in me.”

The thing about desire is it relies on the not-having of the thing you want; then sometimes you get it, and the whole game changes. In the case of Lucy Dacus—the dreamy singer-songwriter and guitarist, best known these days as one-third of indie-rock supergroup boygenius—the conundrum could apply to any number of current-life situations, among them her unexpected success as a Grammy-winning rock god. “I think that through boygenius, it felt like, ‘Well, what else? I don’t want more than this,’” Dacus tells Apple Music. “I feel like I’ve been very career-oriented because I’ve just wanted to play music, satisfy my own drive, and make things that I can be proud of. Getting Grammys and stuff, I’m like, ‘Well, I guess that’s the end of the line. What is my life about?’” On her fourth solo album, *Forever Is a Feeling*, Dacus takes a heartfelt stab at answering that question, and in doing so, opens another desire-related can of worms. While the record explores the intoxicating, confusing, fleeting qualities of romance, it simultaneously functions as a fan-fic-worthy relationship reveal. (She went public with her relationship with boygenius bandmate Julien Baker weeks before the album’s release.) On *Forever*, Dacus dives headfirst into the implied complications, recruiting co-producer Blake Mills for subversive, swooning folk-pop numbers that revel in the mysteries of love, and what precedes it. Dacus’ songwriting has always been vulnerable, though perhaps never this much, nor in this way. “What if we don’t touch?” she begins the super-sexy “Ankles” by proposing—instead, she imagines hypothetical bitten shoulders, pulled hair, crossword puzzles finished together the morning after. (“It’s about not being able to get what you want,” Dacus says of the song. “You want to get them in bed, but you also want to wake up with them in the morning and have sweet, intimate moments, and you can’t. So, you just have to use your imagination about what that might be like.”) She explores the in-between stages of a relationship on the wispy “For Keeps,” takes a quiet road trip through the mountains with her partner on “Talk,” and on “Big Deal,” she wonders to a star-crossed lover if things could ever go back to how it was before, though the climactic final chorus suggests otherwise. Writing *Forever* brought Dacus closer to an answer to the question she posed to herself earlier, and she doesn’t care how cheesy it may sound. “I want my life to be about love,” she explained to Apple Music. “It feels corny to say. But that’s part of what this project is—the idea that talking about love is corny. I don’t think love is all you need, but I do think you need it amongst everything else.”

“There was basically an urgency to this record. It came out of me in this furious burst,” Florence Welch tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe of Florence + the Machine’s sixth full-length. “And it’s one of those records where if I hadn’t have put it out now, it never would’ve come out because I think how I felt about things is so specific to this moment in time, and this roared out of me. It was made almost like a coping mechanism.” That moment in time began for Welch during the *Dance Fever* tour. “I actually ended up having a ectopic miscarriage onstage that was dangerous, and that I had to be hospitalized for, and I had to have immediate surgery because I had a Coke can of blood in my abdomen,” she explains. Her health crisis and ensuing feelings fueled *Everybody Scream*, which offers a haunting yet cathartic experience for both the singer and those listening. “I felt so out of control of my body, it was interesting,” she says. “I looked into themes of witchcraft, and mysticism, and everywhere that you looked in terms of birth or stories of birth, you came across stories of witchcraft, and folk horror, and myths.” Infusing those elements throughout the album, Welch wails, warbles, belts—and, yes, screams—with emotional clarity and appropriately witchy charisma while getting quality assistance in the form of Mitski, Aaron Dessner, and IDLES guitarist Mark Bowen. The title track muses on fame and pushing through the pain to perform: “But look at me run myself ragged/Blood on the stage/But how can I leave you when you’re screaming my name?” Conjuring up a bacchanalian forest rave, “Witch Dance” casts a spell with its heated pace and Welch’s breathy chants. And for the singer, “Perfume and Milk” helps alleviate her own agony. “It was about healing and having watched seasons change and having watched other things growing and then returning to the earth and a sense that I was also part of that nature and part of that cycle,” she says. *Everybody Scream* ends with the stirring “And Love,” striking a hopeful note: “Peace is coming” she repeats on the ballad. “Let this one be the one that comes true,” she says. “Let this one be the one that is realized in the world. I think the songs are always three steps ahead of me. It’s been that way my whole life.”

Released in the wake of his divorce from singer-songwriter Amanda Shires, 2025’s *Foxes in the Snow* is Jason Isbell’s first solo acoustic album, and his first album without The 400 Unit since his 2013 breakthrough *Southeastern*. But don’t let the context color things too much: Isbell’s best writing has a scythelike quality whether backed by a band or not, and relationships born, broken, salvaged, and mourned have been subject matter for him from the get. The lovelorn will no doubt revel in the agony and catharsis of “Eileen,” “Gravelweed,” and “True Believer” (“All your girlfriends say I broke your fucking heart, and I don’t like it”), but allow us to direct you instead to the folksy, John Prine-like wisdom of “Don’t Be Tough”: “Don’t be shitty to the waiter/He’s had a harder day than you,” and, later, “Don’t say ‘love’ unless you mean it/But don’t say ‘sorry’ ’less you’re wrong.” Anyone can cradle their ego, but it takes a gentleman to know when to put it to bed.

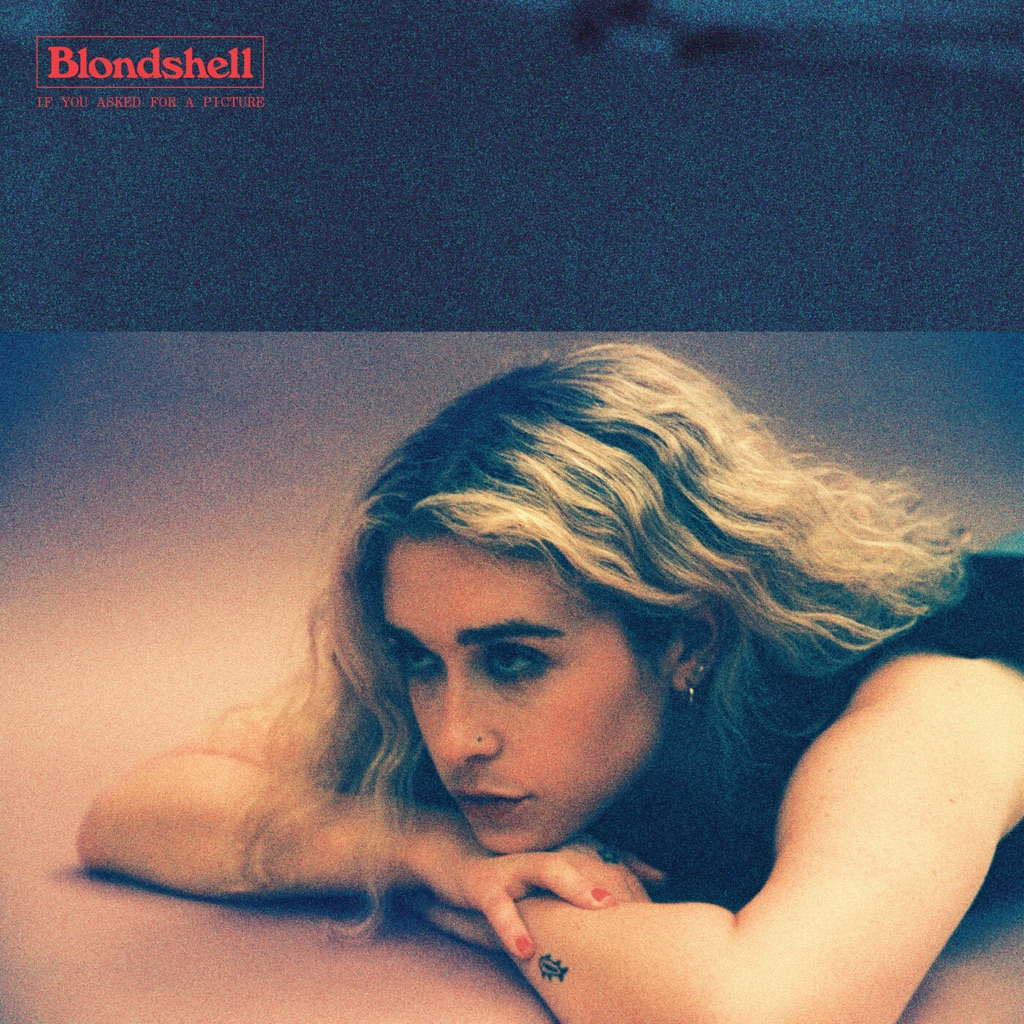

After the reception to her 2023 self-titled debut as Blondshell, it’s no surprise that Sabrina Teitelbaum’s follow-up, *If You Asked for a Picture*, came together while she was quite literally on the move. “I was touring a lot, so I was in a lot of new places and just writing about what was going on,” she tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “I didn’t have the intention of making an album, but when I got home, I was like, ‘Oh, I’m going to start demoing these songs.’” The resulting 12 tracks may have come together casually, but *If You Asked for a Picture* is a fuller and richer evocation of the Blondshell sound, pairing spiky ’90s alternative rock sounds with acerbic couplets. Along with longtime studio collaborator Yves Rothman (Kim Gordon, Yves Tumor), Teitelbaum adds subtle sonic flourishes to her winning sound—peep the Ronettes-recalling backbeat of “23’s a Baby” and the dream pop of closer “Model Rockets”—but her cutting and personal songwriting style remains the project’s hallmark. Who else could write an introspective exploration of living with OCD, as Teitelbaum does on the explosive “Toy,” and sneak in a withering line like, “I’ve been running this ship like the Navy/But it’s more like a Wendy’s”? As Teitelbaum’s songwriting continues to mature, Blondshell’s balance of the devastating and the deeply funny continues on as one of indie rock’s most thrilling high-wire acts.

Soon after The National singer Matt Berninger released his solo debut, *Serpentine Prison*, in the fall of 2020, its name seemed to backfire. After two decades as one of indie rock’s most magnetic lyricists and vocalists, he was trapped inside writer’s block, stuck in a cycle where anything that resembled work or even input induced despair. That trap slowly broke as he and his band began work on 2023’s *First Two Pages of Frankenstein* and its surprise follow-up, *Laugh Track*; their rebuilt rapport slowly revived his lexicon. That same year, Berninger and his family left Los Angeles after a decade, with their country escape to Connecticut recalling scenes of his Ohio childhood. He settled into new rhythms and modes, writing lyrics between the seams of baseballs. *Get Sunk*—a reference to that earlier depressive period and, implicitly, springing out of it—steadily took shape. To make *Get Sunk*, Berninger and longtime engineering partner and producer Sean O’Brien bounced around a Los Angeles studio, building beats and sequences for six hours at a time until Berninger finally found the words that fit. They recruited a sterling support cast, including Hand Habits’ Meg Duffy, session ace Booker T. Jones, and Ronboy leader Julia Laws. They called their dozen or so helpers the “Saturday Musicians.” Berninger’s voice has always been The National’s calling card, the athletic baritone at its center. Wouldn’t a solo album, especially a second, just feel redundant or reductive, an imitation of its more famous setting? But *Get Sunk* is marked by an unexpected versatility. Where he cannily mumbles his way through the textural maze of “Nowhere Special,” he becomes ultimately approachable on “Junk,” a gorgeous and gothic love song that suggests Nick Cave. Where “Frozen Oranges” is a Middle American fever dream about searching for contentment, “No Love” documents the end of personal chemistry, of a relationship that once held meaning now corroding into, at best, niceties. The linchpin, though, is closer “Times of Difficulty,” where that whole big band gathers together to offer an anthem for interdependence, to reaching out for a lift when you get sunk. “Feels like we missed another summer/If we’re not dying, then what are we?” he moans. Getting on, best we can.

After years of touring the world with *Marchita*, Silvana Estrada was burned out. “I made this album during an incredibly difficult time in my life,” she tells Apple Music of *Vendrán Suaves Lluvias*. “I had toured endlessly and was exhausted. My best friend and his brother passed away, and I felt orphaned from so many things at once. I needed to reconnect with beauty in order to feel okay again.” Produced by Estrada with orchestral arrangements by Owen Pallett, the record feels intimate yet cinematic: delicate acoustic textures brushed by sweeping strings. The melancholy of “Dime,” with echoes of Latin American folk, yields to the lightness of “Como un Pájaro,” guided by a whistled melody. Each track feels handcrafted, led by instinct and honesty rather than perfectionism. The title reaches back to childhood. Estrada and her brother read Ray Bradbury’s *The Martian Chronicles*, which closes on Sara Teasdale’s poem “There Will Come Soft Rains,” written after World War I. “That image of hope amid desolation stayed with me forever,” she recalls. It became an anchor for this work—a metaphor for renewal after devastation. It resurfaces in “No Te Vayas Sin Saber,” one of the album’s most luminous and personal songs. “It’s a calm goodbye—because I know that someday I’ll be okay again, and maybe I’ll see you without the pain,” she says. The path there wasn’t simple. Before this project, Estrada tried to record an album in Texas in 10 days—a creative sprint that left her dissatisfied. “Some of those songs died—they stayed there, on the battlefield,” she admits. “When I can remember that time with gratitude, I’ll listen to them again.” That unfinished chapter shed expectations, clearing space for *Vendrán Suaves Lluvias* to emerge truer and freer. Throughout, Estrada braids Mexican folk roots with expanding curiosity. “I didn’t even like life that much at that point, but I still loved beauty,” she says. “And beauty became a kind of promise—because if it could exist inside a song, then maybe it could exist outside of it, too.” That belief turns *Vendrán Suaves Lluvias* into more than a collection of songs: a meditation on beauty’s persistence in the face of despair. “I’m not religious, but in difficult moments, singing has always felt like a prayer,” she says. “When I’m alone and feeling low, I always start singing to lift myself up a little. Before every show, I ask myself how I can turn it into a ritual, how I can make this moment something that makes life feel a little better, even for a while.”

Emotional directness has always been part and parcel of the Laura Stevenson experience—but on *Late Great*, the Long Island-hailing singer-songwriter digs even deeper within as she chronicles the dissolution of a long-term relationship. “There were a lot of changes in my life,” she tells Apple Music. “I had to rebuild, and it was really difficult. The aftermath was having to navigate the world as a person on my own—which was difficult, because I was partnered for my entire adult life.” These 12 songs, imbued with the rich lyricism and melodic punch she’s long been known for, came together as Stevenson dealt with the wreckage amidst navigating continuing education, parenthood, and the expectations of agelessness that come with being a full-time musician. “When you’re in a band, you never really feel like a grown-up,” she laughs. “Your future thinking is not that clear. All of a sudden, it was like, ‘Oh, I’m a grown up, and I don’t know what is going on.” This period of change emboldened Stevenson to take charge in new ways with her studio collaborators, which included pop-punk compatriot Jeff Rosenstock, Real Estate drummer Sammi Niss, and producer John Agnello. “In the past, I wasn’t as vocal about things that I didn’t want—I’m a total people-pleaser, a peacekeeper,” she says. “This time around, I was pretty uncompromising about what I wanted. I sat with this one in a way that I never had before. I don’t think anything ever will be exactly the way you want it to be—but it was as close to what I really want as I’ve ever gotten.” Below, Stevenson tells the story behind each song on *Late Great*. **“#1”** “I wrote this song a long time ago. I was playing it while opening for Murder By Death in 2016, and I was like, ‘Their fans are gonna hate me if I play my little quiet songs.’ So I made it more boisterous than it was intended, and then I hated it and I put it away for a long time. When I was coming back to it, I kept hearing Roy Orbison singing the chorus—and I love a real schmaltzy chorus, so I leaned harder into that. Then I felt like it needed to be over-the-top, so I asked Jeff Rosenstock to add some orchestration—and it was exactly what I wanted. I felt like if it wasn’t huge, then it would be stupider somehow—so it had to be really stupid to the point where it was good, and we got there.” **“I Want to Remember It All”** “When I was writing this song, I was like, ‘Is this already a song?’ I felt like it worked *too* well—it couldn’t possibly be my idea. It’s a song about when things happen in your life that are supposed to happen. My daughter’s here, and every moment of my life that led up to her birth has been the exact right thing that needed to happen to make sure that this very specific human being was made. There were a lot of painful things that happened in the past couple of years, but I want to remember everything. I’ll take the painful stuff if I can have all the beautiful things.” **“Honey”** “Sonically and lyrically, it’s a weaving together of similar ideas. Part of it is about the relationship that I was in, part of it is about love in general, and part of it is about singing to someone I hadn’t even met. It’s love in a bunch of different forms, and then I wove it all together. I’m barely singing to anyone—I might be singing to myself, who knows.” **“Not Us”** “This one’s really sad. I’d never heard a song about this topic, which is when you’re in a relationship and watching everybody else around you break up, and you’re like, ‘That’ll never happen to us—we’re perfect.’ It’s not schadenfreude, but with each relationship that dies around you, for some reason it draws you closer. But then it does happen, and you’re like, ‘Holy shit, I didn’t see that coming.’ How did we get there? Did we just let it fall apart because we didn’t think about it? We just thought it would always work.” **“I Couldn’t Sleep”** “This one is about me getting back out there—I’ve never been single in my entire life. That was scary. Then I was seeing someone, and I felt absolutely nothing—and I was, like, actually happy, because it just didn’t feel right. But then you feel like, ‘Am I broken?’ And that’s scary too, but it’s okay. I just thought it was such a good song, and it makes sense with this chapter in my life where I’m just trying to figure out what is going on—what love is, how to love. This is the truth, and that’s how I’ve always been with the things that I make. I don’t censor it.” **“Short and Sweet”** “It’s about being back in the world again and making yourself vulnerable, and being afraid of that. I’m working as a music therapist, and I work with older populations at an assisted living facility sometimes. I sing that song ‘L-O-V-E,’ and the end of the song goes, ‘Take my heart, but please don’t break it.’ I had a long talk with the folks at the assisted living facility about that lyric, and how that’s such a scary thing—and that’s what love is. So the song is about that, and not being ready for that, because it’s a scary prospect.” **“Can I Fly for Free?”** “I was in Queens seeing Paul Simon, and I had an existential crisis about my life—and also about my physical safety at that moment, because it was a poorly organized operation, there were no clear exits, and I was really scared that the crowd was gonna go crazy and everybody was gonna die. But also, I was feeling a little suffocated in my life. I wasn’t making choices based on what I wanted, and I was going along with things and pretty freaked out. It was like this weird, pivotal, scary moment, and I remember looking up and the moon was coming up so low in the sky, and this Spirit Airlines plane flew past the moon in this way that I’m always gonna have in my mind. The title is kind of a joke, because I mention Spirit Airlines, so it’d be nice to have like some sort of sponsorship.” **“Domino”** “This is about another attempt at love. It’s about knowing something is going to end—and end badly—but also knowing that it was never really real in the first place. It’s another attempt at love, but then you want to go back in a time machine and just be in that place where you felt good for a second, even though you know that everything was bad. When something’s ending, you wish for that ‘ignorance is bliss’ situation, but you can’t get it.” **“Instant Comfort”** “This one’s about being out in the world again—getting burned, and getting burned bad. It’s about knowing what I represented to someone instead of what I actually was, and feeling a little used in that regard, which is scary, and hard. Musically, I was really excited about this one because I borrowed a mandolin from my work. I used a lot of really chime-y instruments, like a 12-string guitar and a couple of other acoustic guitars, to get a really bright-sounding guitar sound that I was looking for. I sat with it a lot in the aftermath to get a layered sound that I couldn’t really describe when we were in the studio, so I did it myself, and sometimes that’s the way to do it.” **“Middle Love”** “I wrote this one on piano very quickly. It’s about a moment in time where you’re dropped into a scene and looking around. It’s very special when those songs happen, because it’s like a short story but you’re not given all the characters or context and you have to figure it out. In this one, it’s two people sitting in a notary’s office, separating. Their driver’s licenses are sitting there, and they’re seeing pictures of themselves in the past from a couple of years prior. They’re looking back at them like, ‘Would you have believed that you’d be sitting there right now in the future?’” **“Late Great”** “I had a friend tell me that this one is their favorite one, and I was like, ‘Really?’ I mean, when I was writing it, I was like, ‘This is a good song.’ But when I was going through the instrumentation, something got lost there for me and I fell out of love with it. But now I’m starting to fall back in love with it, because I’ve been playing it by myself the way that I wrote it. Thematically, it sums the whole album up: I’m doing it on my own, but I’m figuring it out. It’s the only song that has a real positive message.” **“#1 (2)”** “This song is my favorite. I felt like the record needed something, and then it just found its way to the end of the record. A lot had changed during recording, and I had a lot of time to reflect on how crazy and sad everything was. I needed some sort of closure from the whole experience, so I wrote this one about mending the heaviness of it all. There’ll always be grief there, and I do feel like the song really works well in bringing everything full circle.”

The early 2020s was a period of leveling up for Daniel Caesar. The Toronto R&B artist signed to a major label, logged No. 1 hits with Justin Bieber and Tyler, The Creator, and with 2023’s *NEVER ENOUGH*, scored his highest-charting album to date and graduated to arena-headliner status. But as a child of the church, Caesar has always seemed less interested in indulging in the spoils of stardom than in forging a deep spiritual connection with his congregation of fans. In the lead-up to the release of his fourth full-length, *Son of Spergy*, Caesar hosted surprise pop-up concerts in various cities, turning up in local parks on a few hours’ notice with just an acoustic guitar—a fitting prelude to his most intimate and off-the-cuff album to date. Named for his gospel-singer father, *Son of Spergy* is a moment for Caesar to recalibrate after years of whirlwind success, and reconnect with family, old flames, and the church. “Lord, let your blessings rain down,” he sings on the opener, “Rain Down,” a hazy-headed hymn that sets the soul-searching tone for the album. Compared to the beat-driven experimentation of *NEVER ENOUGH*, *Son of Spergy* is both a more organic and psychedelic experience, favoring folky instrumentation that Caesar weaves to delightfully daydreamy effect on openhearted serenades like “Have a Baby (With Me)” and the Bon Iver-assisted beauty “Moon,” where jazzy piano wafts through the dulcet acoustic arrangement like a misty drizzle. But *Son of Spergy*’s Zen vibe is counterbalanced by Caesar’s growing confidence at drawing far outside the lines of R&B: “Call on Me” is an upbeat outlier that pairs crunchy alt-rock guitars and reggae riddims, while “Baby Blue” is a beautifully dazed ballad that just turns stranger and stranger over its six minutes, layering woozy strings, chopped-up vocals, and sound-effect samples with White Album-style wanderlust.

Despite that Cass McCombs is one of the most enigmatic singer-songwriters of the 21st century, his 11th studio album *Interior Live Oak* is an uncommonly generous offering. With 16 tracks and over an hour in runtime, the record spans the many forms his music has taken across his career and pulls in impressive collaborators like indie rock journeyman Matt Sweeney, former Deerhoof member Chris Cohen, and Papercuts’ Jason Quever—the latter of whom collaborated with McCombs on 2024’s archival release *Seed Cake on Leap Year*. But it’s McCombs’ cryptic wit and preference for shaggy-dog melodies that takes center stage across *Interior Live Oak*, with a stylistic left turn or two to keep longtime listeners on their toes. Witness the spry and organ-led “Juvenile,” which takes on the classic New Zealand indie-pop sound while keeping his haunted, searching perspective intact. Few songwriters sound as uncomplicatedly plaintive as McCombs, and yet after more than 20 years of releasing records, he continues to draw listeners in with the type of lyrical musings and overcast melodies so stretched across the chassis of *Interior Live Oak*.

Ben Kweller’s seventh studio album is marked by an unimaginable tragedy: the death of his teenage son Dorian in a car crash in 2023. “The last two years have been the hardest times in my life,” Kweller tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “I replay that night over and over again in my head, and I’ve had to relearn how to live.” A month after Dorian’s passing, Kweller discovered a digital trove of music that his late son had been working on, which lit the spark that created *Cover the Mirrors*; the aching ballad “Trapped” draws from a melody Dorian had been working on. “I remember hearing him in his bedroom singing this amazing chorus, and I walked in and I’m like, ‘Dude, this is awesome, keep going,’” Kweller recalls. Even as some of *Cover the Mirrors*—especially the stream-of-consciousness piano-led opener “Going Insane”—emerged from the solitude of grief, the record finds Kweller embracing the warmth of collaboration more than at any previous point in his career, with contributions from Waxahatchee’s Katie Crutchfield (“Dollar Store”), MJ Lenderman (the rollicking and elegiac closer “Oh Dorian”), Jason Schwartzman’s Coconut Records alias (“Depression”), and The Flaming Lips (“Killer Bee”). “The one thing that’s kept me together through this is community,” Kweller says. “I’m usually so protective of my music, and I think most artists are—but I’ve been so cracked open that I’ve really enjoyed and embraced it.”

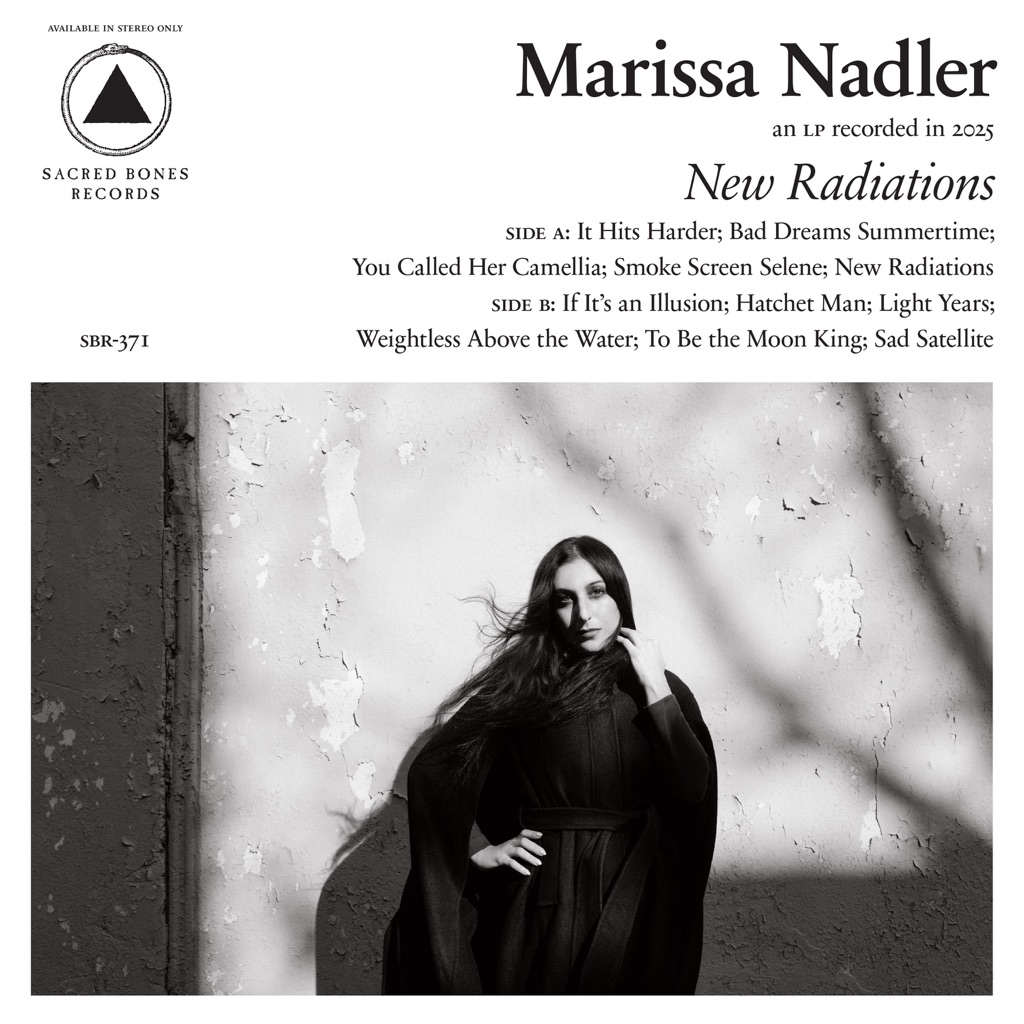

Over the course of two decades, Marissa Nadler has absorbed myriad aesthetics—folk, goth, dream pop, doom metal—into her singular brand of occult Americana. And on 2021’s *The Path of the Clouds*, she executed her most lavish, cinematic, and powerful rendering yet, with the help of special guests like ex-Cocteau Twin Simon Raymonde and harpist Mary Lattimore. However, *New Radiations* sees Nadler going back to old ways, putting the focus squarely on her acoustic guitar-playing and singing. None of these 11 tracks even feature percussion, allowing her double-tracked, self-harmonizing voice to fill the entire canvas of hymns like “It Hits Harder.” No song better encapsulates the album’s uncanny balance of haunted and heavenly than the aptly titled “Bad Dreams Summertime.” And while *New Radiations* features no lack of painterly embellishments from collaborator Milky Burgess—be it the ominous string textures and distorted drones on “Smoke Screen Selene” or the Floydian synth swells on “Weightless Above the Water”—they’re largely used to impressionistic, subliminal effect, representing the turbulent undercurrent of emotions bubbling beneath Nadler’s deceptively serene storytelling.

“Hello, stranger,” Neko Case sings off the top of her eighth album, and it’s a welcome reintroduction, given that *Neon Grey Midnight Green* arrives seven years after its predecessor. Case spent a good chunk of her time away writing her best-selling memoir, *The Harder I Fight the More I Love You*, a no-holds-barred account of her hardscrabble upbringing, and in a sense, *Neon Grey Midnight Green* feels like a continuation of that introspective work. As the first entirely self-produced album of her career, it provides an unfiltered glimpse into her musical mind, where she conjures a surrealist swirl of classic-country balladry, lush ’60s orchestral pop, dissonant punk, and avant-garde experimentation. It’s also a profoundly personal record, informed by the deaths of some longtime indie-rock allies: On “Winchester Mansion of Sound,” she pays tribute to Flat Duo Jets lead vocalist Dexter Romweber with a baroque piano lullaby that gives way to a lovingly nostalgic invocation of the “Down Down Baby” clapping-game sing-along. On the equally haunting and heavenly “Match-Lit,” she and guest Richard Reed Parry of Arcade Fire summon the spirit of The Sadies’ Dallas Good by quoting a song they all bonded over, the Mickey & Sylvia/Everlys standard “Love Is Strange.” At times, *Neon Grey Midnight Green*’s dream-state logic leads Case into bizarre uncharted territory: The theatrical spoken-word jazz poem “Tomboy Gold” is a lot closer to Laurie Anderson than Loretta Lynn. But while such outré excursions mark *Neon Grey Midnight Green* as the most eccentric entry in Case’s canon to date, the album is ultimately anchored by towering, string-swept torch songs—like “Wreck” and “An Ice Age”—that make a convincing case for Case’s gale-force voice to be recognized as the eighth wonder of the world.

Arriving just one year after the Grammy-nominated *Weird Faith*, Diaz’s seventh album dramatically pares back her sound; much of the album is just her and an acoustic guitar, with full-band instrumentation making its return for the album’s cathartic closing title track. The minimalist structures of *Fatal Optimist* were born out of a breakup and a period of self-enforced solitude, and with co-producer Gabe Wax (Soccer Mommy, Zach Bryan) at the boards, these 11 songs ring out with warmth and quiet devastation. Diaz has always been known for emotional missives that cut close to the bone, but moments like the reflective pain of “Ambivalence” and the not-looking-back kiss-off “Lone Wolf” are as direct as she’s ever been on record.

History gets harder and harder to make, but never in the long, weird history of popular music has there been an analogue for this. Doorstop box sets with troves of fan-coveted rarities are de rigueur for any legacy artist, very much including Bruce Springsteen, whose 1998 compilation *Tracks* dutifully assembled 66 of these—four and a half hours of alternate history to one of rock’s most vaunted narratives. Twenty-seven years later, its nominal sequel is composed of seven full and distinct stand-alone albums recorded between 1983 and 2018, largely unknown to even the most devout Springsteen cryptographers. That something so auspicious and audacious bears the modest title *Tracks II* is the slyest joke of his career. Individually, these albums demonstrate logical extensions of his classic songwriting that manage to meet that impossible standard—much like outtakes from *Darkness on the Edge of Town* and *The River*, which were both full LPs’ worth of parallel material every bit the equal of the latter works, as well as tantalizing, disciplined, and fully realized genre exercises that have no real precedent in his discography. As a whole, the collection begs nothing less than a wholesale reevaluation of an already deeply considered career. A collection of gussied-up home recordings that bridges the gap between 1982’s *Nebraska* and the 1984 supernova *Born in the U.S.A.*. An entire album in the subdued synth-pop vein of “Streets of Philadelphia” and “Secret Garden.” (The long-held idea that the ’90s was a relatively fallow period for Springsteen goes very much out the window here.) An atmospheric soundtrack to a shelved western that answers the question, “What if Springsteen transformed himself into Tom Waits?” One pure honky-tonk album and one of jazz standards-style torch songs. An album influenced by traditional Mexican music, another of full-bore, more recent vintage rock songs. These are the worlds contained within *Tracks II* and below is a quick and deeply insufficient guide to Springsteen’s most recent epic. ***LA Garage Sessions ’83*** Few words in the rock lexicon are more malleable than “garage.” For Springsteen in 1983, this meant an apartment over the garage of his new home in the Hollywood Hills, where he decamped in the interregnum between 1982’s spare, downcast *Nebraska* and 1984’s *Born in the U.S.A.*, which catapulted him from mere rock star to global icon and—forgive us—brand. Probably not a surprise, then, that these semi-polished home demos split the difference between those two vibes: “Don’t Back Down on Our Love” and “Don’t Back Down” have the bones of what could have been a couple of vintage E Street rave-ups, while “The Klansman” is a pitch-black song about the son of a proud KKK member learning the ropes. ***Streets of Philadelphia Sessions*** While on paper, this may seem similar to *LA Garage Sessions*—Springsteen working largely alone, at home, with a drum machine—it feels less like rough demos than a collection of fully realized songs that happen to share a specific dynamic. Even adding the word “sessions” into the title feels like a hedge. Springsteen’s slump-busting hit “Streets of Philadelphia,” written for Jonathan Demme’s 1993 film *Philadelphia*, was pared down to his voice, synths, and drum loops—a combination he found appealing enough to continue for another 10 songs, fleshed out in places by members of his early-’90s post-E Street backing band. While “Secret Garden” found its way to a greatest-hits compilation, the others were lost to lore—a whispered-about but never heard “drum loops album.” It’s not the rap or trip-hop album that those whisperers may have been imagining; it is, rather, a logical extension of the two known songs to come out of these recordings, only maybe a little hornier. “Maybe I Don’t Know You” has “Brilliant Disguise” DNA in its blood, while “One Beautiful Morning” comes the closest to a more traditional full-band sound. ***Faithless*** In 2005, Springsteen was commissioned to compose the soundtrack to what he has called a “spiritual western” called *Faithless* by an as-yet-unnamed director, but probably someone we’ve heard of. The movie never wound up being made, but Springsteen held up his end of the bargain, and the result is as revelatory as anything in his career—a mix of moody instrumentals and gospel-tinged Americana ballads that manage to be oddly timeless despite the purported 19th-century setting. At least one song (“All God’s Children”) sounds so much like early-’90s Waits that you may check to make sure you didn’t switch records, while “Where You Going, Where You From” is buttressed by a choir of voices including two of Springsteen’s children. (Note: “Goin’ to California” is *not* a Led Zeppelin cover, but given the experimental streak on display, you’re excused for letting your imagination run a little wild.) ***Somewhere North of Nashville*** If this set were constructed chronologically, and it is not, this one would have been slotted right after *Streets of Philadelphia Sessions*. As Springsteen began reactivating the E Street Band in 1995, he shelved what would have been that solo release and began working on *The Ghost of Tom Joad* and this—a companion album of sorts that took a lighter approach tonally and sonically. *Somewhere North of Nashville* is a honky-tonk lark with a cast of characters including slide guitarist Marty Rifkin. “Janey Don’t You Lose Heart,” a beloved *Born in the U.S.A.*-era B-side, gets revisited here a decade later, and sounds more than a little like R.E.M.’s “(Don’t Go Back To) Rockville.” This isn’t exactly Springsteen out of his element, but it may have been greeted in 1995 as the exact kind of cutting loose that fans hadn’t seen from him in a long time. ***Inyo*** A largely solo acoustic affair along the lines of *Devils & Dust*, also recorded around this time, *Inyo* is tied together by Springsteen’s focus on detailed, character-driven stories about the American Southwest and the Mexican border, combining the stark narrative style forged and perfected on *Nebraska* with música mexicana flourishes like mariachi bands and strings. Thirty years later, stories about the Southern border and the people on either side of it wind up being more resonant and urgent than he could have imagined at the time. ***Twilight Hours*** In a sprawling collection that highlights Springsteen’s career-long comfort with formal genre exercises, the grand Burt Bacharach-style ballads of *Twilight Hours* may be the most jarring. Not that The Boss doesn’t deserve some downtime to undo his bow tie and nurse his heartache over a stiff martini, but it’s an era that doesn’t have much of an analogue in Springsteen’s canon. Written more or less alongside the long gestation period that eventually birthed *Western Stars*, songs like the title track, “Late in the Evening,” and “Sunday Love” evoke a smoke-filled lounge that couldn’t have fit anywhere else. ***Perfect World*** While the other six albums here were conceived and finally now realized as stand-alone works, the finale is an odds-and-sods collection of songs from the mid-’90s through the early 2010s with a loose theme: They’re nice rock songs, crowd-pleasers that just never reached any crowds, and are most likely the kind of thing that comes to mind when you close your eyes and think of the words “Bruce” and “Springsteen.” “I’m Not Sleeping” channels Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers’ “Don’t Do Me Like That,” while coulda-been hits like “Rain in the River” and “You Lifted Me Up” exemplify what makes this entire sprawling set such a unique window into a revered artist’s process: Someone could have forged a legendary career just off the material that one man couldn’t find a place for and barely remembered he made.