Graham Johnson’s music as quickly, quickly has always retained an intimacy even as the project has grown in scope. His homespun brand of psych-infused bedroom pop began evolving with 2021’s *The Long and Short of It*, remixing the DIY spirit of his catchy lo-fi tunes to include technicolor instrumental bursts and some of his clearest vocals to date. On its follow-up, 2025’s *I Heard That Noise*, Johnson imbues these vast soundscapes with moments of spontaneity and experimentation. His voice is more powerful than ever before, and he mirrors the whimsy of his instrumentals with his unpredictable melodic inclinations. Take “Enything,” a guitar-driven, folk-leaning track with spindly guitar melodies and a propulsive drum part. Johnson’s vocals build alongside the groove, which hints at a resolution that never comes. His ability to conjure and resolve tension is effortless and seamless. “Raven,” on the other hand, is an acoustic campfire jam, a track unlike anything else on the album. Here, Johnson performs the role of storyteller, his voice raw and vulnerable, matching the gravitas of the moment—whatever it may call for.

Both within and without his psych-rock outfit Wand, Cory Hanson has been on a lifelong quest to find harmony and ecstasy in a turbulent world that so often denies it. On his 2023 album, *Western Cum*, he sought it through epic high-voltage guitar odysseys, but on *I Love People*, the LA maverick lays off the six-string heroics and immerses himself in a soft-focus fantasia of Laurel Canyon gold sounds. With standout serenades like “Bird on a Swing,” “I Don’t Believe You,” and “On the Rocks,” Hanson resembles a rhinestone Rundgren, casting his pristine pop melodies in a countrypolitan patina, while solitary ballads like “Old Policeman” see him ease into the role of a last-call saloon troubadour vying for a spot on the Asylum Records roster circa 1973. But even when working in more formal classic-rock modes, Hanson’s idiosyncratic spirit still cuts through: the elegiac piano hymn “Lou Reed” pays tribute to the Velvet Underground trailblazer; however, Hanson seems less interested in romanticizing his musical innovations than his tai chi skills.

You’ll probably recognize the general sounds and styles on Ezra Furman’s 10th album: Beatles-y psych-folk (“Sudden Storm”), quasi-industrial ’90s pop (“Submission”), soft-focus disco (“You Hurt Me I Hate You”), and Springsteen-style garage (“Power of the Moon”). What’s great about Furman is the way she manages to make all these familiar, almost stock forms feel idiosyncratic by pushing them to their expressive limits. Like great karaoke, the key to her performances isn’t the way she pulls things together but the way she falls so joyfully, dramatically, performatively apart, queering the edges of pop tradition until it frays at the seams.

Helen Ballentine’s musical moniker Skullcrusher suggests a far different kind of music than what she writes. On *And Your Song Is Like a Circle*, the songs sink in like a scalp massage; there’s no physical crushing here. Ballentine’s second album, though, isn’t as light as some of the instrumentals suggest: Inspired by filmmakers like David Lynch and Hayao Miyazaki, Ballentine examines the nature of the human experience—the duality of feeling infinitely alive while knowing that sensation is fleeting. The concept is also reflected in the album title and the riverlike way these songs flow into one another. “Living” features Ballentine’s voice floating disparately against layers of harmonies and abstract synths, before a simple drum groove gives the song forward direction. It eventually concludes right back where it began, though, completing the circle.

The *Little House* EP finds Rachel Chinouriri still a month shy of celebrating the one year anniversary of her career-accelerating debut album, 2024’s *What a Devastating Turn of Events*, an anthemic, Britpop-inspired chronicle of her turbulent early twenties. With her star in rapid ascendance—critical acclaim, two BRIT Award nominations, a sold-out headline tour of her own, and an A-list guest spot opening for Sabrina Carpenter—the London-born singer-songwriter’s 180-degree pivot from devastation to satisfaction marks this four-track EP. It’s out with the self-doubt and second-guessing that shrouded her previous works and in with sunny optimism and an unassuming confidence, amplified by the heady rush of new love. Chinouriri is an expert when it comes to channeling boundless levels of unchecked feelings into potent shots of ear-snagging indie pop and while the tenor of her emotions has shifted, it’s clear from the effusive one-two punch of “Can we talk about Isaac?” and “23:42” that she has ample raw material at her disposal. The former recalls Chinouriri’s meet-cute moment in a burst of barely suppressed excitement propelled by surfy guitar riffs and finger-snapping percussion; on the latter she pinballs between delight and disbelief at her romantic luck over a cheerful, jaunty beat peppered with sci-fi synth stabs. Later, “Indigo” slows all the gushing to a measured pour, echoing the refrain “You make love feel like...” and letting an atmospheric swell of harmonic vocals fill in the blank. Sandwiched in between, “Judas (Demo)” is somewhat of an outlier, but the simple combination of Chinouriri’s anxious late-night musings backed by the soft strum of an acoustic guitar offers a familiar flash of haunting vulnerability—a reminder of the strong foundations *Little House* is building on.

“It feels really good to be in the driver’s seat,” singer-songwriter Shawn Mendes tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe on the eve of releasing *Shawn*, his first album in four years and most personal record to date. A teenage social-media sensation who became one of pop’s biggest stars in the late 2010s, Mendes pulled back after the release of 2020’s *Wonder*, canceling a 2022 tour and setting out on a journey to find himself, a decision he calls “terrifying” but one that was ultimately liberating. “It was the greatest gift I’ve ever given myself,” he says. “I gave myself a life. The best part about that is, it taught me that the next time I’m standing at the crossroads between choosing something in my truth or doing what would make everyone else happy, I have this reference point.” “Everything’s hard to explain out loud,” Mendes sings on the hushed opener “Who I Am,” a sketched overview of where Mendes has been and what’s to come over the next half-hour. It strips down Mendes’ music to its essence—vocals and strummed guitar framing lyrics that detail the way his thoughts raced as his life got too big around him. *Shawn* feels loose and confident even as it’s economical, putting Mendes’ reflections and smoke-plume voice front and center on the campfire sing-along “Why Why Why” and his tender, album-closing cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah.” The swaying “Heart of Gold” is a Laurel Canyon-inspired cut where Mendes laments the way a longtime friend slipped out of his circle before passing away, its weeping slide guitar providing a counterpoint to the bittersweet reminiscing about the days when he and his friend “shot for the stars.” “That’ll Be the Day” is fatefully lovelorn, its arrangement as delicate as lace, as Mendes muses on the idea of eternal love. On “The Mountain,” Mendes takes aim at the many rumors that have swirled around him and his intimates over the last two years in gently devastating fashion, rebuking anyone who might put him in a box while acoustic guitars roil beneath him. “Call it what you want,” Mendes sings on its refrain, and that phrase became an almost-defiant mantra for him as he was working on his fifth album. The song references a spiritual experience he had in Kauai. “Without going into the exact details of it, leaving that mountain that day gave me something I’ve always wanted, which was a sense of security that no success could ever provide me, no relationship could ever provide me,” he says. “It was security with myself. A lot changed after that, because when you’re not chasing something, you let go. And then it almost feels like things are starting to appear.” As he tells Lowe, whatever label people might want to place on him “really doesn’t matter, because I feel this.” *Shawn*, as a whole, is a statement of purpose from a musician who’s a veteran of the game in his mid-twenties—and it shows what he’s capable of when there’s nothing holding him back.

Brandi Carlile is hardly the only songwriter to be inspired by Joni Mitchell. But she is on a short list of artists who can boast that her own album is a direct result of having been Mitchell’s close collaborator. “I had finished playing the Hollywood Bowl \[in 2024\] with Joni, and it took up so much of my spiritual space and my mind space,” she tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “I felt really emotionally make-or-break, because I just wanted that to be a pivotal moment for Joni.” Carlile’s stewardship of her hero’s comeback performances, alongside *Who Believes in Angels?*, her 2025 team-up with Elton John, another one of her idols and mentors, left her little time to tend to her own music. “It became so overwhelming and so all-consuming that this little voice did start to say, ‘OK, you’re not going to live very long if you keep setting the bar for yourself in these really stressful places,’” she says. “‘And you’re also hiding a little bit.’” Following her time in LA with Mitchell, she headed to Aaron Dessner’s Long Pond Studio in upstate New York to begin work on *Returning to Myself*. “I didn’t know whether we were going to be writing songs for someone else, or writing songs for me, or what we were going to be doing,” she explains. Though she admits to struggling initially with the process, the end result runs from the sweet and sentimental (“Anniversary”) to the angry (“Church & State”) and, of course, an emotional ode to Mitchell herself (“Joni”). Read below for Carlile’s thoughts on a few key tracks. **“Returning to Myself”** “I didn’t even bring a guitar. I went upstairs to the bedroom, and I sat on this bed looking at a blank wall, and I was so stressed to be that alone. I wrote the poem for *Returning to Myself*. It was just a poem; it didn’t have music or anything yet. I was just almost rejecting it. I was almost feeling like, ‘OK, this is it. This is a noble pursuit, me staring at this wall. This is what it means to learn to be alone. I guess I’m evolving right now. I feel like I’m not doing anything at all but just indulging myself and sitting here on this bed.’” **“Human”** “I do feel that every generation since recorded history believes that their generation is the one living through the end of the world. I think that’s really comforting. And we do. We all see our conflicts and our wars and our political upheavals and tyranny and democracy in constant balance. We are in a loop, and the loop is the loop of humanity. And don’t be apathetic. Don’t ignore it. Don’t look away. Do fight. Do be an activist. Do get out of bed every morning and think about how you can serve humanity. But also touch grass. Also realize that you’re here for a split second and that you don’t want to look back and realize you missed the whole thing because you believed you were living through the end of the world.” **“Church & State”** “We were set up to jam and that song was really carnal. We were in a circle. It was like rock ’n’ roll time, and it was November 5th, the night of the \[2024\] election. I went into the studio, laptop open, spiraling, just not doing great emotionally. I mean, I knew what was coming. I had written ‘Human’ the night before, and it was like a primal cry for self-preservation in a way, and not just for me, for everybody.”

The New York-based band Florist make music that captures both the naive sweetness of indie folk and the cosmic abstraction of ambient and New Age. Fuller than *Emily Alone* and more cohesive than the documentarylike *Florist*, 2025’s *Jellywish* feels, in some ways, like the album they have been approaching for years: simple, porchy songs glittering with unexpected bits of processed sound. The childlike voice of Emily Sprague delivers thoughts on death (“Started to Glow”), redemption (“Have Heaven”), and other less-than-childlike things. This is music that feels modest and ordinary but is always reaching quietly into the unknown. The tension between their folksy side and their cosmic one turns out to resolve easily: In both cases, they are looking for the beauty they know is right in front of them.

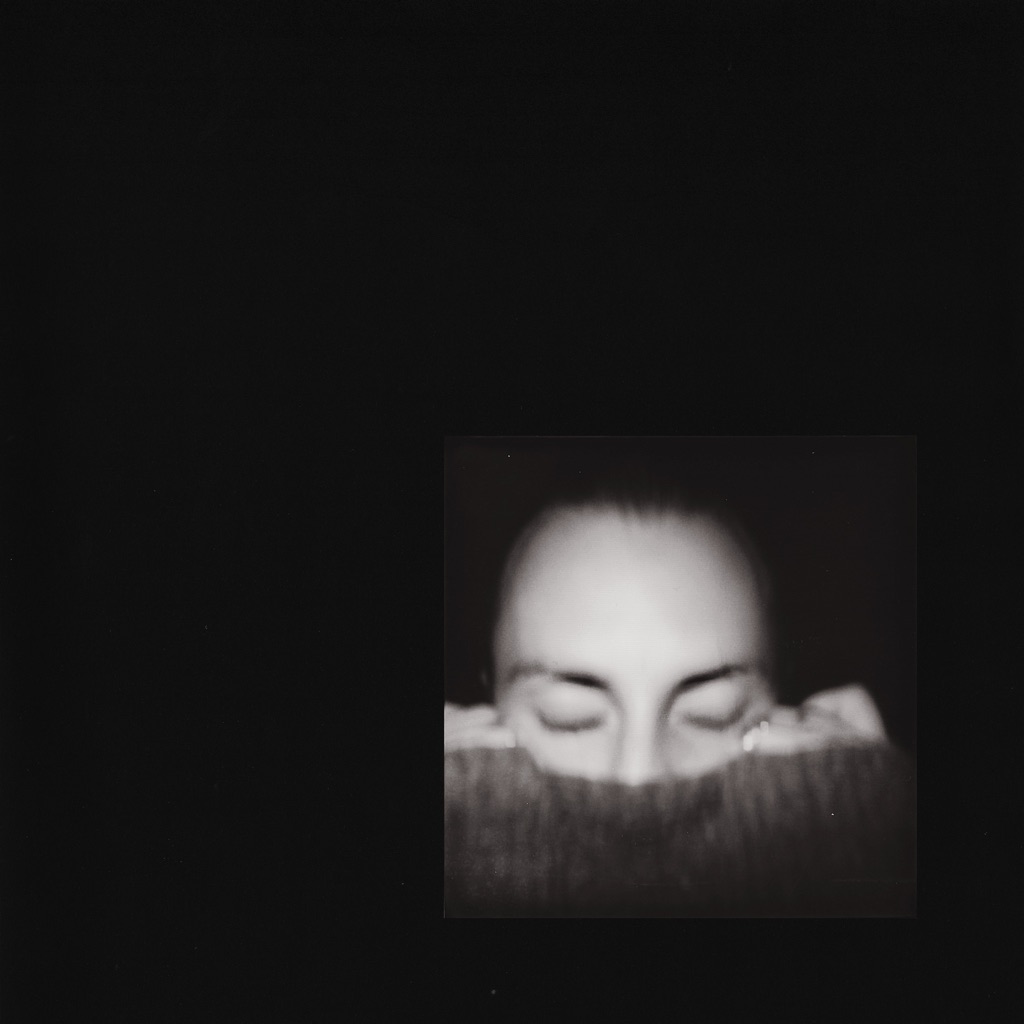

This ninth studio album from Amanda Shires follows a particularly tumultuous period in the acclaimed singer-songwriter/fiddler’s life. *Nobody’s Girl* was written and recorded in the wake of her very public divorce from fellow musician and former bandmate Jason Isbell, and the resulting songs take stock of the raw early days of her journey to healing. Produced by friend and collaborator Lawrence Rothman (Blondshell, Bartees Strange), *Nobody’s Girl* opens with an instrumental invocation, with a particularly mournful fiddle performance from Shires that sets the tone for the complex emotions to follow. “A Way It Goes” offers a painful, revealing glimpse at the dissolution of her marriage, which she describes with trademark poeticism and no shortage of vulnerability: “I could show you a real shattering/A bird flown into a glass window collapsing.” “The Details” is stark and cutting, with lyrical Easter eggs that point to Isbell, including a nod to his fan-favorite 2013 track “Cover Me Up,” which he wrote about Shires. While there is plenty of ache on the album, there is also hope, like on “Living,” where she acknowledges that “perfect conditions don’t exist,” and closing track “Not Feeling Anything,” which still carries the considerable weight of grief but acknowledges the silver linings of independence and starting over.

The central theme running through the beguiling third album by Shura is stripping everything back and starting over, no matter how daunting that feels. *I Got Too Sad for My Friends* marks a complete artistic reset for the London-born, Manchester-raised singer-songwriter, one that grew out of a period of emotional turmoil. Moving away from the sad banger synth-pop of her first two records, 2016’s *Nothing’s Real* and 2019 follow-up *forevher*, it’s a record steeped in an Americana-ish sway and folky reassurance. Shura found that the way out of the gloom that enveloped her during lockdown, where she was increasingly cutting herself off from her inner-circle, was to return to how she’d written songs as a teenager: alone in a room with an acoustic guitar. It gave her a path back, the route that led to the hazy, wistful warmth of *I Got Too Sad for My Friends*. It opened up a dramatic overhaul in how she made music. Working with a new producer (Foals and Depeche Mode collaborator Luke Smith), Shura got down the majority of the record in live takes that were tweaked and honed further down the line, constantly daring herself to try new things. It has taken her to the defining album of her career so far, a record full of rich melodic hooks and a soothing melancholic glow, from the country longing of “Richardson” via the expansive ’80s pop of “Recognise” to doe-eyed campfire ditties (plaintive closer “Bad Kid”). It’s a fresh start in all the best ways, a third album that feels like a startling debut. Her pals would surely agree—it was all worth it in the end.

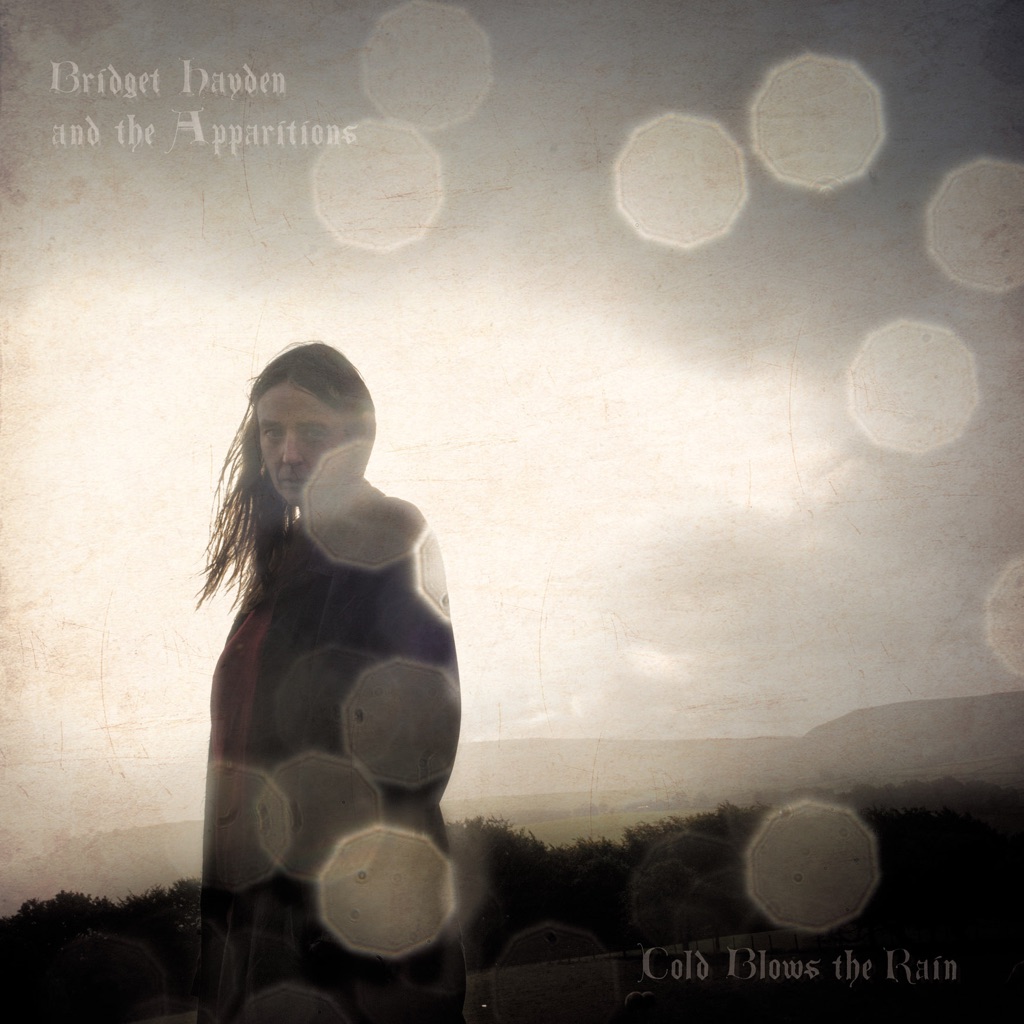

Five years between albums has given Nadia Reid plenty to reflect upon across *Enter Now Brightness*, recorded while she was pregnant with her second child. Besides becoming a mother since 2000’s *Out of My Province*, the Aotearoa New Zealand songwriter relocated across the world to Manchester, England. So themes of renewal run naturally through these warm, open songs, with Reid backed primarily by guitarist/keyboardist Sam Taylor and multi-instrumentalist/producer Tom Healy. Half of these tracks are quite sparse, while the other half deploy bassist Richard Pickard and drummer Joe McCallum for an effective oomph. Even the more stripped-back tracks aren’t as rooted in folk music as Reid’s earlier work was, but rather in a ruminative strand of indie pop. Whichever mode she’s in, she sings with such calm sureness that it’s easy to get swept up in the emotional truth of her lyrics. As horns lick the edges of the woozy ballad “Baby Bright,” she tells her older daughter, “Something tells me that you’re gonna be all right.” And on “Hold It Up,” Reid sounds downright serene as the arrangements wax and wane around her and she assures us, “I can be kind to anyone.”

“Let me introduce myself/I’ve been lost in the dark/I don’t stay in one place/I have many names,” the musician Adam Andrzejewski (formerly McIlwee) sings over wistful pedal steel on “I Just Moved Here.” You’d think the singer-songwriter would need no introduction, having been active in the music scene for two decades now. But the Pennsylvania native has evolved over the years, tapping the deep well of the zeitgeist: For eight years, he sang and played guitar in the post-hardcore band Tigers Jaw, then coined the Wicca Phase moniker and co-founded the GothBoiClique collective, whose murky underground aesthetic seeped into the mainstream. On *Mossy Oak Shadow*, the prolific artist ventures out of his comfort zone and into what he calls “mystical folk rock.” Here, roads are lonely, horizons are endless, hearts are heavy, and thunder rolls in over the darkened plains. But familiar motifs tie rootsy songs like “Enchantment” and “Meet Me Anywhere” (a duet with Ethel Cain, with whom he collaborated on her 2021 EP *Inbred*) to Wicca Phase’s past work: Portals appear in the moonlight, revelations arrive in solitude.

Gigi Perez pours her life experience into her work. After the viral success of her 2024 single “Sailor Song”—an open plea for queer romantic connection that topped the UK singles chart and went platinum in several other countries—her self-produced debut album plays like unabashed memoir. “Sugar Water” opens with a nod to Perez’s birthplace of Hackensack, New Jersey before recounting schoolyard taunts and even the texture of her childhood Barbie’s hair. Her sister Celene’s death in 2020 sits at the center of “Fable,” with both that song and the closing title track featuring voicemails left by Celene. Perez also unpacks that family tragedy on the darker “Survivor’s Guilt,” while the album’s title was inspired in part by Perez sleeping on the beach after her sister died. The emotive singing and busker-style folk balladry of Perez’s earlier releases is very much at play, though lilting strings interweave with the acoustic guitar on “Crown” and the especially surprising “Twister” adds Auto-Tune and a programmed beat. But again, the lyrics are most often the star here, with the singer-songwriter revisiting her intense religious upbringing alongside love, loss, and other weighty themes.

The cover art for the sixth album from indie-pop dynamo George Lewis Jr.—aka Twin Shadow—features the handwritten signature of his father Georgie, who passed away from cancer in 2024. It’s a poignant visual cue for what is undoubtedly the most nakedly personal and reflective album of Twin Shadow’s career. Where so much of his discography exists in a never-ending summer of ’84 where Prince and Springsteen are jostling for the top of the charts, *Georgie* strips Lewis’ songcraft down to the core. The glistening guitars and neon-tinted synth textures remain, but the tracks are almost entirely devoid of drums or beats and left to freely float in a sea of melancholy and simmering resentment—the bittersweet serenade “Good Times” is really a chronicle of the bad ones and an indictment of fair-weather friends who never seem to be around when you need them the most. But on tracks like “You Already Know” and “Permanent Feeling,” Lewis’ intimately soulful voice displays a Bon Iver-esque ability to transform even the most skeletal songs into full-blooded, heart-pumping hymns.

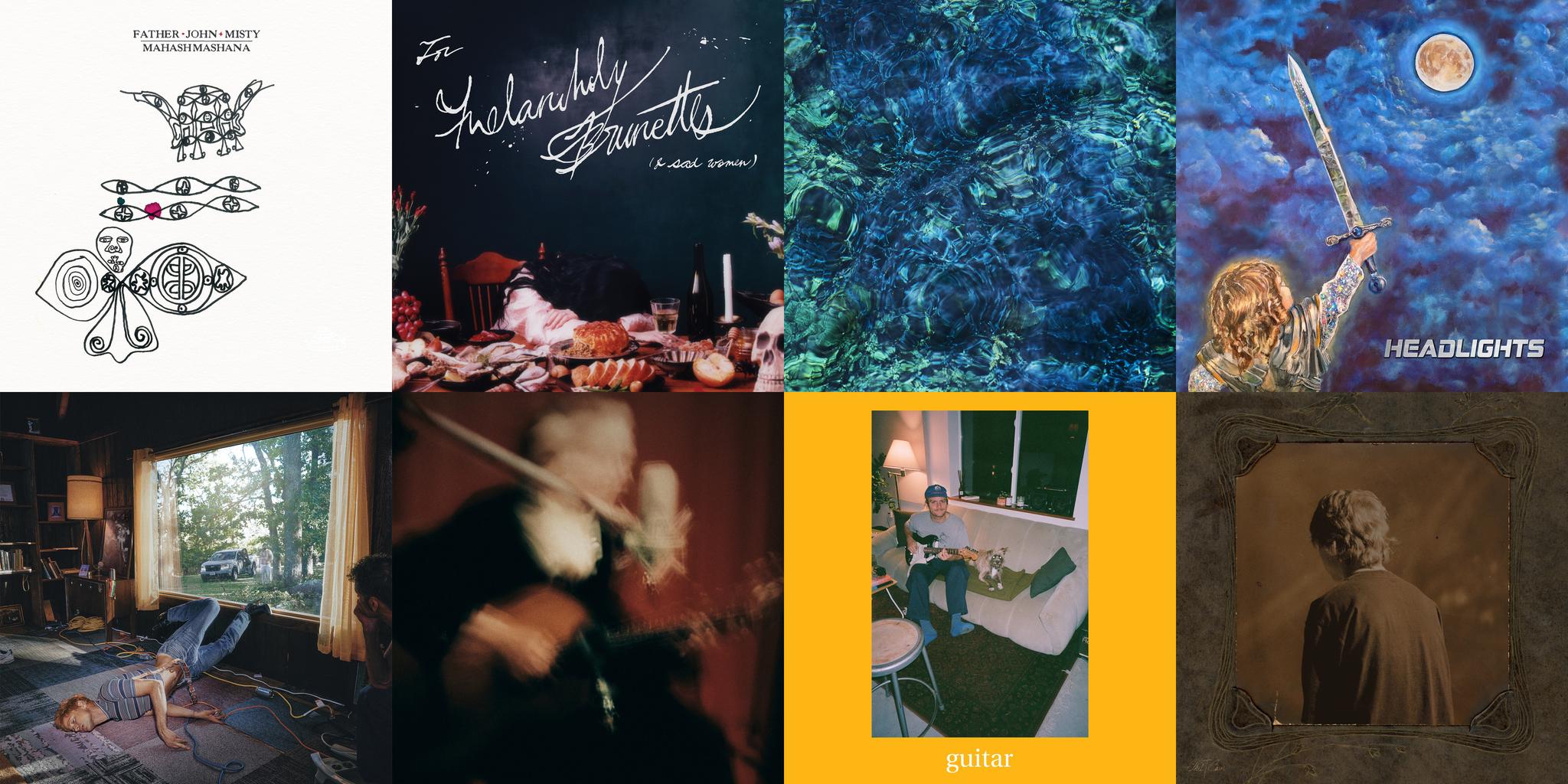

Folk Bitch Trio’s debut album contains several very distinct through lines. “The songs are us experiencing things that we mostly experienced together or with real-life narration of, ‘This is what’s happening in my life,’” guitarist/vocalist Jeanie Pilkington tells Apple Music. “They’re songs that come from our shared brain and heart, and individual brains and hearts.” Given that some were composed during the Melbourne band’s extensive national and overseas touring, adjusting to life on the road is another clear theme, particularly in songs such as “Mary’s Playing the Harp.” “A few of them were written in that transition between \[touring\] not being a part of our lives and starting to tour, and starting to make sense of going to weird places to perform and how that feels,” says Pilkington. Adds guitarist/vocalist Heide Peverelle: “I write a lot on the road and a lot of the songs reference feelings of being on tour.” It was during one of those tours, supporting English songwriter Ben Howard on an Australian and New Zealand run in 2024, that the trio stopped by Auckland’s Roundhead Studios to record “God’s a Different Sword” with producer Tom Healy, who would go on to helm the full record. They were drawn to the studio for its equipment. “They have a tape machine, and we had decided we wanted to work on tape for this record,” says Peverelle. The analog recording accentuates the trio’s astonishingly warm vocal harmonies (all recorded live), which sit atop their dreamy, pastoral folk and occasional flourishes of lo-fi electric guitar. “It’s us on a plate,” says Peverelle. “It feels like our hearts are very open.” Here, Pilkington, Peverelle, and vocalist/guitarist Gracie Sinclair take Apple Music through *Now Would Be a Good Time*, track by track. **“God’s a Different Sword”** Heide Peverelle: “When I brought that to the group to arrange and tweak, it felt like an introduction to how we wanted to go sonically. It’s just about the euphoria and optimism you feel \[at\] the end of a breakup, starting afresh.” Gracie Sinclair: “It signifies that feeling of having your own hands back on the wheel. And you’re like, I’m driving my life now.” **“Hotel TV”** Jeanie Pilkington: “It’s about a relationship going bad. Gracie wrote the hook when we were in a hotel in Brisbane, our first time staying out of Melbourne to do music, needing some rest. We needed a fucking break. It really resonated with the rest of the song, ’cause that’s what I was trying to say—I needed to step away, because I was in this suffocated environment that is that hotel room, but also that relationship.” **“The Actor”** HP: “The story is very true; it’s quite a literal song. When you start dating someone, and even if you’ve been married to someone, \[you can\] still not really know them. I think it’s about that and the mask you wear when you’re in a relationship, and if shit gets hard and it crumbles.” JP: “It’s short and it’s punchy. I think it represents a downward spiral that happens very quickly, before you can even catch yourself.” **“Moth Song”** JP: “People think it’s me talking to my bandmates.” GS: “It’s me talking to myself. I’m Gracie and I’m singing, so I say my own name. ‘Moth Song’ is about losing the plot. It’s about wanting more from the relationships that you have around you and feeling very heartbroken and very alone in that. I was sitting on the train feeling very sorry for myself for some reason, and daydreaming and imagining all these moths filling the train carriage, and that’s what I’m talking about in the chorus—I was imagining the train doors opening and all these moths going up into the sky like confetti. That’s a nice release.” **“I’ll Find a Way (To Carry It All)”** GS: “It’s the closer to the A-side of the record.” JP: “It’s like a breathing point. Originally, we were going to open the record with this because, for a long time, we opened our set with it when we played live—it’s a great way to shut up the room. But it felt a little bit somber to open \[the album\] like that. Now, it’s this really nice point where, if you’re listening on vinyl, it closes out the first side. The B-side of the record is a bit darker and rocks a bit harder.” **“Cathode Ray”** GS: “This was the last song on the record to get finished. It’s about frustration in a relationship, and when you love someone and you feel like you just can’t get through to them. And you really want to and you want to see them come undone.” **“Foreign Bird”** JP: “\[It’s about\] trying to force yourself to do something and then stopping to realize, hang on, why the hell am I doing this, I don’t want to? And just trying to pull yourself out of your own habits.” **“That’s All She Wrote”** HP: “I spent a lot of time in Northeast Victoria and I was really picturing that part of the world when I was writing it. Each verse and chorus feels like it has a time stamp for me—the first verse is a few years ago, and the middle is more recently and again with the last verse. There’s a clear picture in my mind of each scenario \[and\] specific relationships I had.” **“Sarah”** HP: “It’s a breakup song. We really went back and forth about whether it would be on the record ’cause it felt overly earnest. We wanted to really try and bring down the earnestness with the more rocky guitar vibe.” **“Mary’s Playing the Harp”** JP: “It’s a song about being on tour and being heartbroken, and watching a Mary Lattimore set at a festival in Thirroul and thinking about someone I was going to have to see that I really missed, but also was really dreading what that was going to feel like. We did this superlong tour a couple of years ago through regional Australia and it was a real time of peaks and valleys. Some weird experiences, some bad experiences, just trying to figure out how to live on the road and how isolating that can be. A weird thing to experience as a very young woman or femme person, and all those things came into play.”

No one would accuse dodie of giving anything less than her best effort on her 2025 album, *Not for Lack of Trying*. The project, which is a “sister” album of sorts to her 2021 full-length debut, *Build a Problem*, is a cinematic tour of the troubles, joyous experiences, traumas, and uncertainties that fill her life. When she sings “Big, brave girl—29 now/I’m fine now, really, I’m fine now” on opening track “I’M FINE,” she seems to be convincing herself of this fact more than asserting it. It’s a vulnerability that animates the entire record, like on “Darling, Angel, Baby,” which takes inspiration from the anthemic, defiant indie rock of songwriters like Mitski. dodie says to her subject that she’ll be awaiting their kiss when they’re ready, and this time the uncertainty is something she finds comfort in. There are, refreshingly, no straight answers and wide-eyed certainties on *Not for Lack of Trying*. Rather, dodie explores the world, eager to see which questions are worth keeping around and which are better left unanswered.

If you’ve ever seen Bahamas in concert, you’ll know that, on top of being a charismatically laidback singer and dazzling guitar player, Afie Jurvanen delivers stage banter with the deadpan flair of a seasoned stand-up comedian. So, it’s safe to assume he’s being somewhat cheeky in titling his seventh Bahamas record *My Second Last Album*—after all, Jurvanen seems like the sort of lifer who’ll be sharing his witty I-just-wasn’t-made-for-these-times commentary and casually dropping brain-bending guitar solos well into his nursing-home years. *My Second Last Album* is a testament to his resourcefulness: Where his 2023 release, *BOOTCUT*, saw him heading down to Nashville and surrounding himself with a Music City dream team of veteran session players, this time he stayed close to home in rural Nova Scotia, shacking up in producer Joshua Van Tassel’s tiny backyard studio shed, with the two handling all instrumentation. But the results are no less rich and splendorous than any ensemble Bahamas effort: “The Bridge” sets a text-message-based songwriting collaboration with Hiss Golden Messenger’s MC Taylor to a flute-inflected, gospel-gilded funk strut, while the American-culture satire “Dearborn” dresses up its “Son of a Preacher Man” groove with fuzz-tone licks and falsetto hooks. But on the closing slow-motion serenade “In Country,” Jurvanen removes his tongue from cheek to celebrate his Finnish family’s immigrant experience. “We all belong in this country,” he sings and, likewise, Bahamas’ breezy, soft-rockin’ country-soul welcomes all comers with open arms.

When UK-born singer-songwriter Jade Bird was making her 2024 EP *Burn the Hard Drive*, she didn’t realize she was writing about a breakup that hadn’t happened yet—the one that would involve her fiancé-slash-touring guitarist. *Who Wants to Talk About Love?*, Bird\'s third album, is a more conscious processing of that loss. But rather than focus its songs tightly on just that relationship, Bird widens her lens of self-reflection, reckoning with the failed marriages around her (specifically her parents’ and both sets of grandparents’) to better understand where she might’ve gone wrong. This personal introspection underscores Bird’s gifts for raw, nakedly honest storytelling. She poses the album’s title as a rhetorical question in “Who Wants,” a look at her family’s poor communication habits in the face of love breaking down. And on “Dreams,” which she wrote the morning after a particularly rough night with her now ex, Bird questions her will to leave a partnership that isn’t working. But in “Glad You Did,” she finds that, in hindsight, it was all for the best. “You let me slip right out your grip,” she sings. “You lost me, gone bit by bit, but I’m so glad you did.”