Esquire's (UK) 20 Best Albums of 2016

From Bon Iver to DJ Shadow, the tracks you've been humming for the past 12 months - and some you may have missed

Published: November 17, 2016 17:41

Source

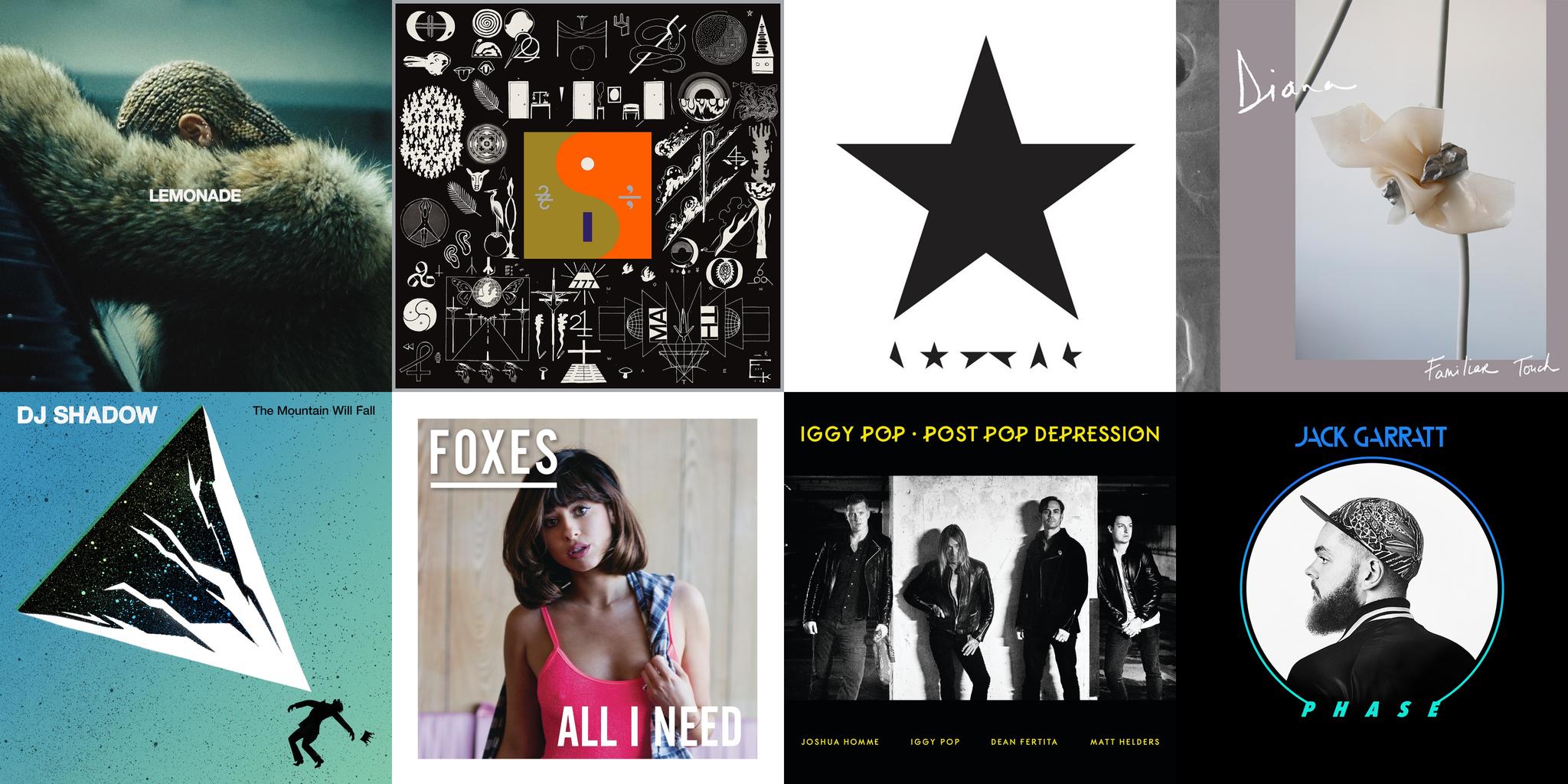

There’s one moment critical to understanding the emotional and cultural heft of *Lemonade*—Beyoncé’s genre-obliterating blockbuster sixth album—and it arrives at the end of “Freedom,” a storming empowerment anthem that samples a civil-rights-era prison song and features Kendrick Lamar. An elderly woman’s voice cuts in: \"I had my ups and downs, but I always find the inner strength to pull myself up,” she says. “I was served lemons, but I made lemonade.” The speech—made by her husband JAY-Z’s grandmother Hattie White on her 90th birthday in 2015—reportedly inspired the concept behind this radical project, which arrived with an accompanying film as well as words by Somali-British poet Warsan Shire. Both the album and its visual companion are deeply tied to Beyoncé’s identity and narrative (her womanhood, her blackness, her husband’s infidelity) and make for Beyoncé\'s most outwardly revealing work to date. The details, of course, are what make it so relatable, what make each song sting. Billed upon its release as a tribute to “every woman’s journey of self-knowledge and healing,” the project is furious, defiant, anguished, vulnerable, experimental, muscular, triumphant, humorous, and brave—a vivid personal statement from the most powerful woman in music, released without warning in a time of public scrutiny and private suffering. It is also astonishingly tough. Through tears, even Beyoncé has to summon her inner Beyoncé, roaring, “I’ma keep running ’cause a winner don’t quit on themselves.” This panoramic strength–lyrical, vocal, instrumental, and personal–nudged her public image from mere legend to something closer to real-life superhero. Every second of *Lemonade* deserves to be studied and celebrated (the self-punishment in “Sorry,” the politics in “Formation,” the creative enhancements from collaborators like James Blake, Robert Plant, and Karen O), but the song that aims the highest musically may be “Don’t Hurt Yourself”—a Zeppelin-sampling psych-rock duet with Jack White. “This is your final warning,” she says in a moment of unnerving calm. “If you try this shit again/You gon\' lose your wife.” In support, White offers a word to the wise: “Love God herself.”

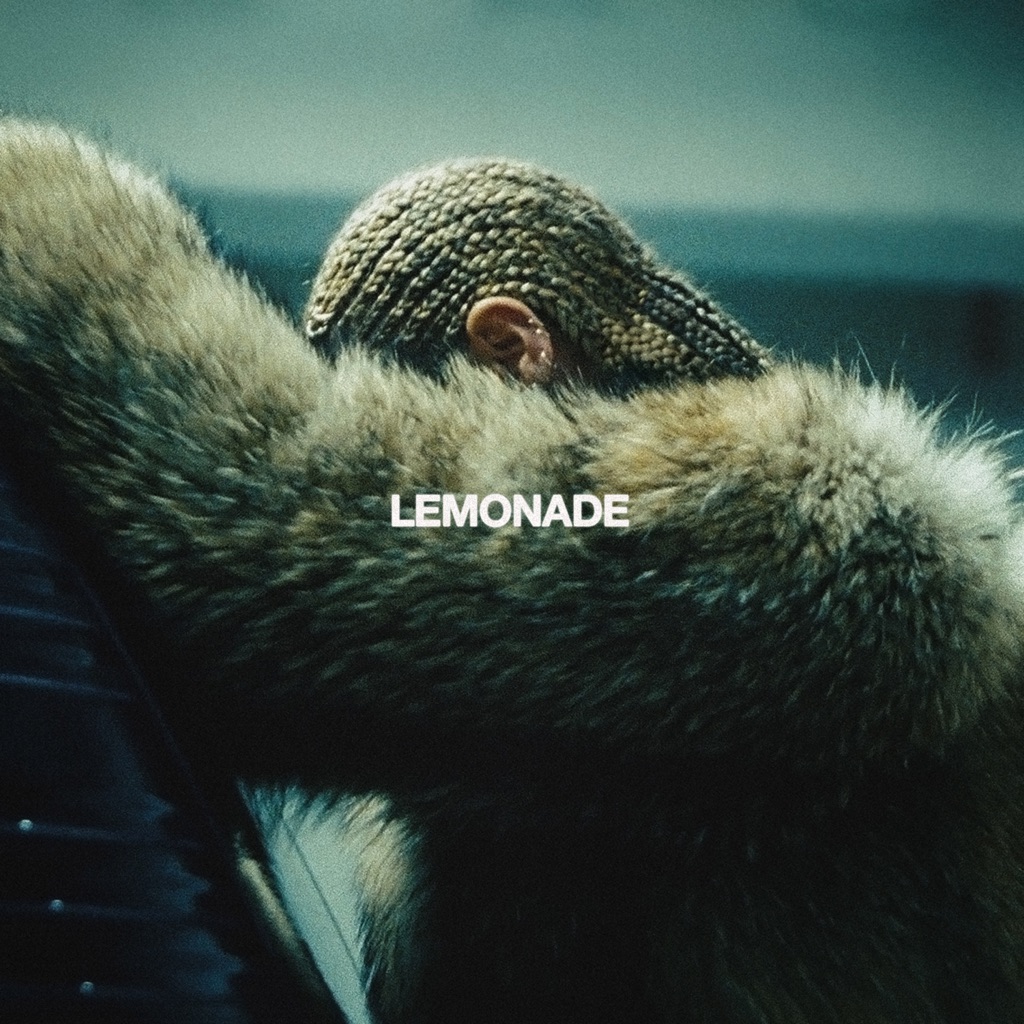

Bon Iver’s third LP is as bold as it is beautiful. Made during a five-year period when Justin Vernon contemplated ditching the project altogether, *22, A Million* perfects the sound alloyed on 2011’s *Bon Iver*: ethereal but direct, layered but stripped-back, as processed as EDM yet naked as a fallen branch. The songs here run together as though being uncovered in real time, with highlights—“29 #Strafford APTS,” “8 (circle)”—flashing in the haze.

'22, A Million' is part love letter, part final resting place of two decades of searching for self-understanding like a religion. And the inner-resolution of maybe never finding that understanding. The album’s 10 poly-fi recordings are a collection of sacred moments, love’s torment and salvation, contexts of intense memories, signs that you can pin meaning onto or disregard as coincidence. If Bon Iver, Bon Iver built a habitat rooted in physical spaces, then '22, A Million' is the letting go of that attachment to a place.

DJ Shadow, widely acknowledged as a crucial figure in the development of experimental, instrumental hip-hop, will return with ‘The Mountain Will Fall’ worldwide on June 24 via Mass Appeal Records [and Believe Digital in France], his first full length release since 2011. The 12-track album finds DJ Shadow exploring new realms in addition to the deep samples and kinetic soundscapes that helped to launch his career 20 years ago. On ‘The Mountain Will Fall’ he’s shifted further toward original composition, a vast experimentation of beats and textures, synthesizers and live instruments including horns and woodwinds. The album features Run The Jewels, Nils Frahm, Matthew Halsall, Ernie Fresh and more.

The second album from singer/songwriter Louisa Allen moves her into rarefied UK pop air. It’s a supremely confident set full of fevered melodrama, delicious despair and, crucially for her chances of superstardom, euphoric choruses. *All I Need* also shows off a dynamic, versatile performer. Pared back on “If You Leave Me Now” and “Scar” she’s ethereal, “Cruel” sees her skillfully navigate a spry R&B beat and the hymnal “Better Love” unleashes her full vocal force. But it’s “Body Talk”—powered by dreamy ‘80s synths and tailor made for summer festivals—that really underlines Foxes’ maturing appeal.

How do you make a grand statement when you have nothing left to prove? On *Post Pop Depression*, Iggy Pop huddles with Queens of the Stone Age’s Josh Homme, Dead Weather’s Dean Fertita, and Arctic Monkeys’ Matt Helders. The results are wiry, muscular, and shape-shifting, much like Iggy himself. His unctuous cool drips all over slow-burners like “American Valhalla” and “Break Into Your Heart.\" “Vulture” sounds like Iggy reading a twisted campfire story. “Paraguay” and “Chocolate Drops” are as poignant as they are profane. Nearly 50 years from where it all began, *Post Pop Depression* proves that the punk pioneer can still cause a ruckus.

This prodigiously-hirsute Londoner has spent the fledgling days of his career picking up armfuls of awards in the UK. His debut (double) album—a wildly ambitious, kaleidoscopic opus—justifies the billing. The juddering electro-R&B of “Worry” and “The Love You’re Given” showcase a skillful use of space and silence, while “Surprise Yourself” and “I Couldn’t Want You Anyway” gently reveal Garratt’s inner-troubadour and an ability to move hearts, minds, and feet.

Julia Jacklin thought she’d be a social worker. Growing up in the Blue Mountains to a family of teachers, Jacklin discovered an avenue to art at the age of 10, thanks to an unlikely source: Britney Spears. Jacklin chanced upon a documentary about the pop star while on family holiday. “By the time Britney was 12 she’d achieved a lot,” says Jacklin.”I remember thinking, ‘Shit, what have I done with my life? I haven’t achieved anything.’ So I was like, ‘Mum, as soon as we get home from this holiday I need to go to singing lessons.’ Classical singing lessons were the only kind in the area, but Jacklin took to it. Voice control was crucial, and Jacklin flourished. But the lack of expression had the teen seeking substance, and she wound up in a high school band, “wearing surf clothing and doing a lot of high jumps” singing Avril Lavigne and Evanescence covers. It wasn’t much but she was hooked. Jacklin’s second epiphany came after high school. Travelling in South America she reconnected with high school friend and future foil Liz Hughes. The two returned home to the Blue Mountains and started a band, bonding over a love of indie-Appalachian folk trio Mountain Man and the songs Hughes was writing. “I would just sing,” says Jacklin. “But as I got my confidence I started playing guitar and writing songs. I wouldn’t be doing music now if it wasn’t for Liz or that band. I never knew it was something I could do. “ Now living in a garage in Glebe and working a day job on a factory production line making essential oils, the 25-year old found time to hone her craft – to examine her turns of phrase, to observe the stretching of her friendship circles, to wonder who she was and who she might become. That document is Jacklin’s masterful debut album, Don’t Let The Kids Win - an intimate examination of a life still being lived. Recorded at New Zealand’s Sitting Room studios with Ben Edwards (Marlon Williams, Aldous Harding, Nadia Reid), Don’t Let The Kids Win courses with the aching current of alt-country and indie-folk, augmented by Jacklin’s undeniable calling cards: her rich, distinctive voice, and her playful, observational wit. You can hear it in opener ‘Pool Party’, a gorgeous lilt bristling with Jacklin’s tale of substance abuse by the pool; in the sparse, ‘Elizabeth’, wrestling with both devotion and admonishment of a friend; in detailing the slow-motion banality of a relationship breakdown in the woozy ‘L.A Dreams’; and in her resolve to accept the passing of time on the snappy fuzz of ‘Coming Of Age’. The album hums with peripheral insights, minute in their moments but together proving an urge to stay curious. “I thought it was going to be a heartbreak record,” says Jacklin of Don’t Let The Kids Win. “But in hindsight I see it’s about hitting 24 and thinking, ‘What the fuck am I doing?’ I was feeling very nostalgic for my youth. When I was growing up I was so ambitious: I’m going to be this amazing social worker, save the world, a great musician, fit, an amazing writer. Then you get to mid-20s and you realise you have to focus on one thing. Even if it doesn’t pay-off, or you feel embarrassed at family occasions because you’re the poor musician still, that’s the decision I made.” In person Jacklin is funny, wry, quick to crack a joke. It makes the blunt honesty and prickly insight laced through her songwriting disarming, a dissonance she delights in. “Especially coming from my family,” says Jacklin. “They don’t talk about feelings at all. I love writing songs about them and watching them listen and squirm. To me that’s great. I enjoy it.” The title track was the last song Jacklin wrote for the album. “My sister’s getting married soon,” she says of the closer. “And it hit me – we used to be two young girls and now that part of our lives is over. Seeing her talking about wanting to have a baby and…it’s like, man I can’t believe we’re already here.” Don’t mistake this awareness for nostalgia. “It’s not that I want to go back to that time at all,” says Jacklin. “It’s trying to figure out how to be responsible when you don’t identify with who you were anymore.” “All my friends at this age are freaking out. Everyone’s constantly talking about being old. Don’t Let The Kids Win is saying yeah we’re getting older but it’s not so special. It’s not unique. Everyone has dealt with this and it’s going to keep feeling weird. So I’m freaking out about it too but that song is trying to convince myself: let’s live now and just be old when we’re old.”

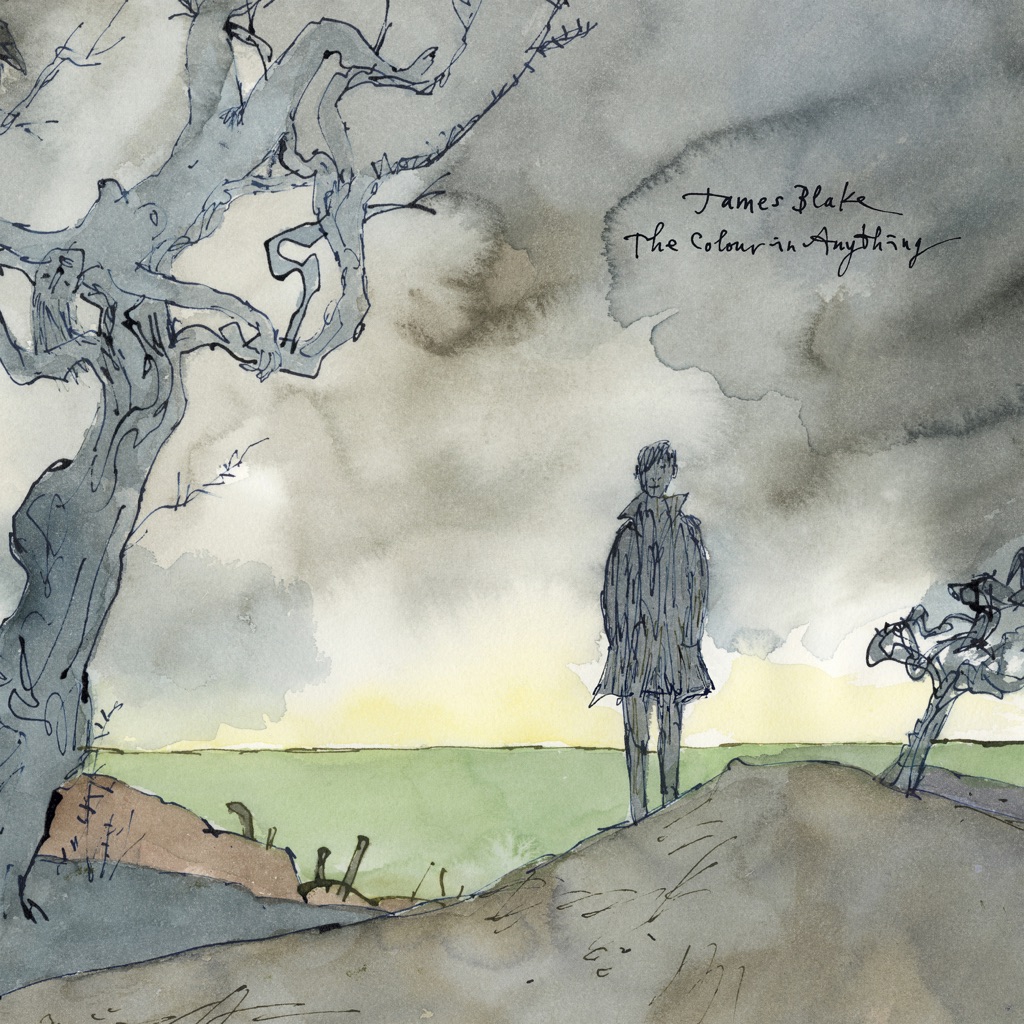

*You Want It Darker* joins *Old Ideas* and *Popular Problems* in a trio of gorgeous, ruminative albums that find Cohen settling his affairs, spiritual (“Leaving the Table”), romantic (“If I Didn’t Have Your Love”), and otherwise. At 35, he sounded like an old man—at 82, he sounds eternal.

The border-crossing pop visionary returns with her most positive and self-assured album yet. Like her past triumphs, *AIM* is both thoughtful and provocative. Between the bhangra and boom-bap is the lived-in confidence of an artist who no longer has to shout to be heard, evidenced on the Delhi dancehall of “Visa” and the album-closing “Survivor,” her most unabashedly pretty song yet.

2011’s *Hurry Up, We’re Dreaming* was a gargantuan album to add to the canon of gargantuan M83 albums. *Junk* is rather different, but no less thrilling. Out go the blown-out anthems and in their place, nostalgically candied pop, disco and soul gems. It bobs merrily between gloriously indulgent (“Do It, Try It”, “Go!”), gloriously silly (“Moon Crystal” sounds like a ‘70s TV theme), and deeply romantic (“For the Kids”, “Atlantique Sud” and \"Sunday Night 1987”). “Solitude”, meanwhile, is gorgeous, cinematic and blessed with a spellbinding keytar solo. It’s that sort of album.

On *Under the Sun*, abstract techno mastermind Mark Pritchard steps off the dance floor and into a free-floating ambient excursion. In place of the almighty beat are acoustic flourishes, musique concrète-style experiments, and synth-driven textures, often assisted with some heavenly voices. “Infrared” is ragged and noisy industrial, while “Falling” finds Pritchard noodling up and down the scale with warped organ tones. But the gems here are folk singer Linda Perhacs’ haunting vocals on the lush “You Wash My Soul,” and “Beautiful People,” on which Thom Yorke is equally gentle and soulful over a lo-fi Latin beat.

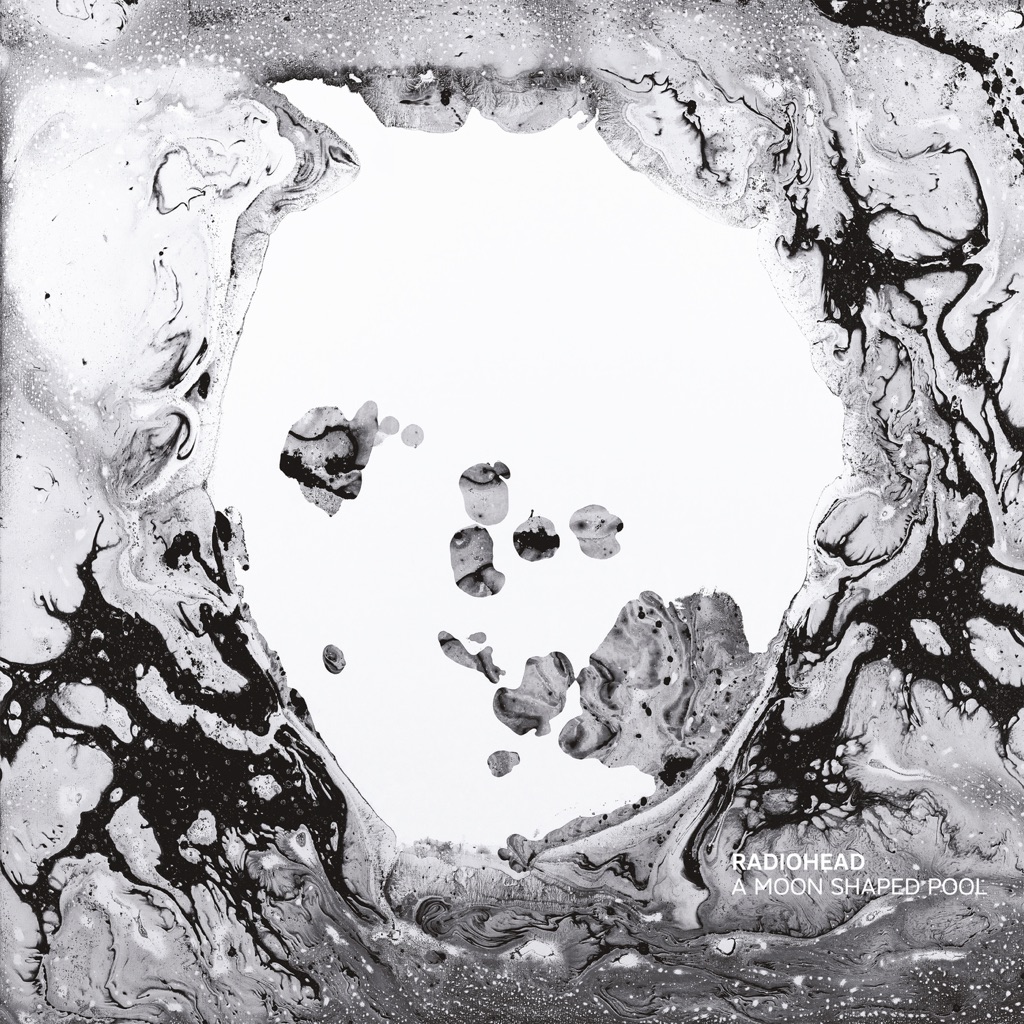

Radiohead’s ninth album is a haunting collection of shapeshifting rock, dystopian lullabies, and vast spectral beauty. Though you’ll hear echoes of their previous work—the remote churn of “Daydreaming,” the feverish ascent and spidery guitar of “Ful Stop,” Jonny Greenwood’s terrifying string flourishes—*A Moon Shaped Pool* is both familiar and wonderfully elusive, much like its unforgettable closer. A live favorite since the mid-‘90s, “True Love Waits” has been re-imagined in the studio as a weightless, piano-driven meditation that grows more exquisite as it gently floats away.