Consequence of Sound's Top 50 Albums of 2016

These are the titles we clung to in a year dominated by division, conflict, and loss.

Published: November 28, 2016 05:00

Source

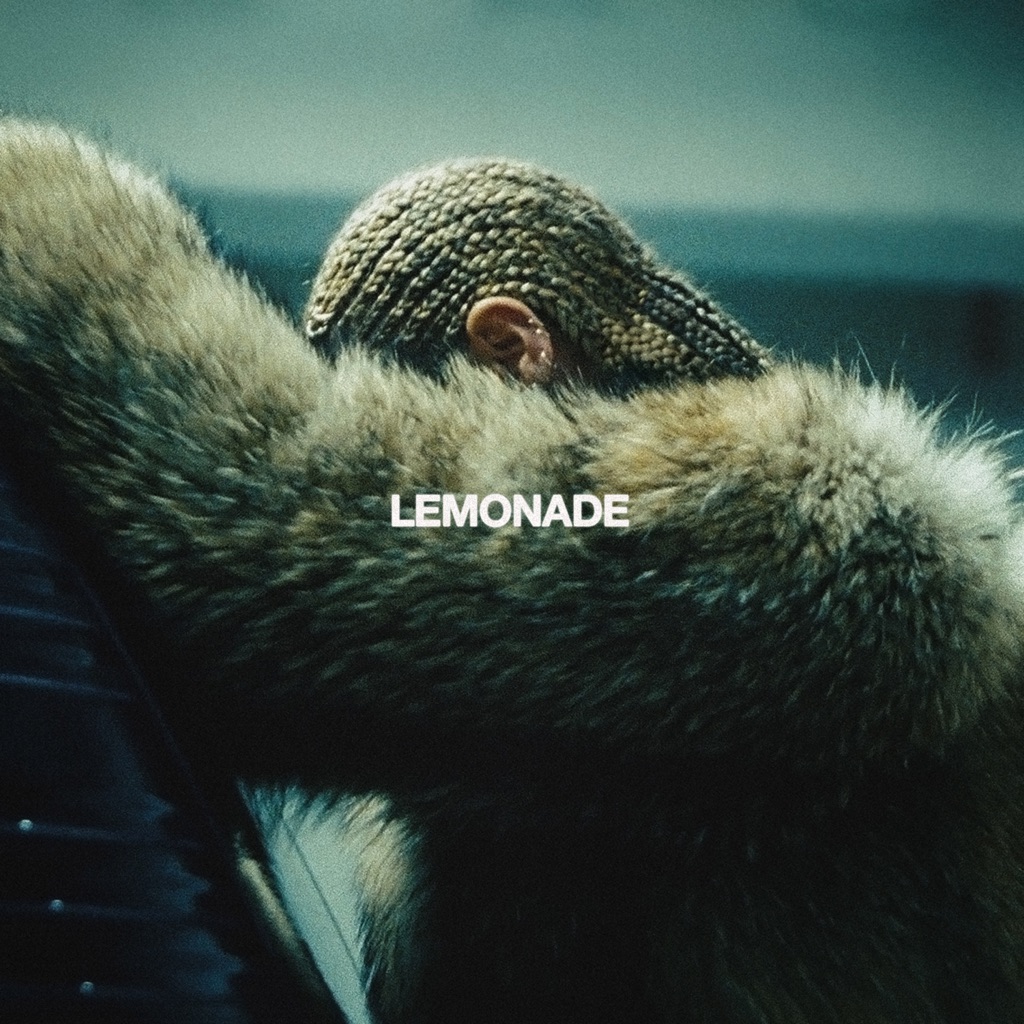

There’s one moment critical to understanding the emotional and cultural heft of *Lemonade*—Beyoncé’s genre-obliterating blockbuster sixth album—and it arrives at the end of “Freedom,” a storming empowerment anthem that samples a civil-rights-era prison song and features Kendrick Lamar. An elderly woman’s voice cuts in: \"I had my ups and downs, but I always find the inner strength to pull myself up,” she says. “I was served lemons, but I made lemonade.” The speech—made by her husband JAY-Z’s grandmother Hattie White on her 90th birthday in 2015—reportedly inspired the concept behind this radical project, which arrived with an accompanying film as well as words by Somali-British poet Warsan Shire. Both the album and its visual companion are deeply tied to Beyoncé’s identity and narrative (her womanhood, her blackness, her husband’s infidelity) and make for Beyoncé\'s most outwardly revealing work to date. The details, of course, are what make it so relatable, what make each song sting. Billed upon its release as a tribute to “every woman’s journey of self-knowledge and healing,” the project is furious, defiant, anguished, vulnerable, experimental, muscular, triumphant, humorous, and brave—a vivid personal statement from the most powerful woman in music, released without warning in a time of public scrutiny and private suffering. It is also astonishingly tough. Through tears, even Beyoncé has to summon her inner Beyoncé, roaring, “I’ma keep running ’cause a winner don’t quit on themselves.” This panoramic strength–lyrical, vocal, instrumental, and personal–nudged her public image from mere legend to something closer to real-life superhero. Every second of *Lemonade* deserves to be studied and celebrated (the self-punishment in “Sorry,” the politics in “Formation,” the creative enhancements from collaborators like James Blake, Robert Plant, and Karen O), but the song that aims the highest musically may be “Don’t Hurt Yourself”—a Zeppelin-sampling psych-rock duet with Jack White. “This is your final warning,” she says in a moment of unnerving calm. “If you try this shit again/You gon\' lose your wife.” In support, White offers a word to the wise: “Love God herself.”

On this, his first masterpiece, Chance evolves—from Rapper to pop visionary. Influenced by gospel music, *Coloring Book* finds the Chicago native moved by the Holy Spirit and the current state of his hometown. “I speak to God in public,” he says on “Blessings,” its radiant closer. “He think the new sh\*t jam / I think we mutual fans.”

In the four years between Frank Ocean’s debut album, *channel ORANGE*, and his second, *Blonde*, he had revealed some of his private life—he published a Tumblr post about having been in love with a man—but still remained as mysterious and skeptical towards fame as ever, teasing new music sporadically and then disappearing like a wisp on the wind. Behind great innovation, however, is a massive amount of work, and so when *Blonde* was released one day after a 24-hour, streaming performance art piece (*Endless*) and alongside a limited-edition magazine entitled *Boys Don’t Cry*, one could forgive him for being slippery. *Endless* was a visual album that featured the mundane beauty of Ocean woodworking in a studio, soundtracked by abstract and meandering ambient music. *Blonde* built on those ideas and imbued them with a little more form, taking a left-field, often minimalist approach to his breezy harmonies and ever-present narrative lyricism. His confidence was crucial to the risk of creating a big multimedia project for a sophomore album, but it also extended to his songwriting—his voice surer of itself (“Solo”), his willingness to excavate his weird impulses more prominent (“Good Guy,” “Pretty Sweet,” among others). Though *Blonde* packs 17 tracks into one quick hour, it’s a sprawling palette of ideas, a testament to the intelligence of flying one’s own artistic freak flag and trusting that audiences will meet you where you’re at. In this case, fans were enthusiastic enough for *Blonde* to rack up No. 1s on charts around the world.

ANOHNI has collaborated with Oneohtrix Point Never and Hudson Mohawke on the artist's latest work, HOPELESSNESS. Late last year, ANOHNI, the lead singer from Antony and the Johnsons, released “4 DEGREES", a bombastic dance track celebrating global boiling and collapsing biodiversity. Rather than taking refuge in good intentions, ANOHNI gives voice to the attitude sublimated within her behavior as she continues to consume in a fossil fuel-based economy. ANOHNI released “4 DEGREES,” the first single from her upcoming album HOPELESSNESS, to support the Paris climate conference this past December. The song emerged earlier last year in live performances. As discussed by ANOHNI: "I have grown tired of grieving for humanity, and I also thought I was not being entirely honest by pretending that I am not a part of the problem," she said. “’4 DEGREES' is kind of a brutal attempt to hold myself accountable, not just valorize my intentions, but also reflect on the true impact of my behaviors.” The album, HOPELESSNESS, to be released world wide on May 6th 2016, is a dance record with soulful vocals and lyrics addressing surveillance, drone warfare, and ecocide. A radical departure from the singer’s symphonic collaborations, the album seeks to disrupt assumptions about popular music through the collision of electronic sound and highly politicized lyrics. ANOHNI will present select concerts in Europe, Australia and the US in support of HOPELESSNESS this Summer.

The songwriter transfigures personal tragedy into growling, elemental elegies. On his latest collaboration with the Bad Seeds, Nick Cave pulls us through the gorgeous, groaning terrors of “Anthrocene” and “Jesus Alone” only to deliver us, scarred but safe, to “I Need You” and “Skeleton Tree,” a pair of tender, mournful folk ballads.

After the lonesome folk and skeletal roadhouse soul of her debut album, 2012’s *Half Way Home*, Angel Olsen turned up the intensity on *Burn Your Fire for No Witness*, and she does it again on *MY WOMAN*. The title’s in all caps for a reason: The St. Louis, Missouri, native’s third album is bigger in both the acrobatic feats of her always-agile voice and the widescreen, hi-fi sound that Olsen and co-producer Justin Raisen bring to the table. With the very first song, “Intern,” it’s clear that Olsen has taken us somewhere new. A slow dance in a dive bar at last call, it might be familiar turf were it not for the synthesizers that cast an eerie glow across the song’s red-velvet backdrop. “Never Be Mine” harnesses the anguish of ’60s girl groups in jangling guitar and crisp backbeats; “Shut Up Kiss Me” couches desire in terms so heated the mic practically melts beneath Olsen’s yelp. Mindful of its ancestry but never expressly retro, the album is a triumph of rock ’n’ roll pathos, an exquisite dissertation on the poetry of twang and tremolo. And even if “There is nothing new/Under the sun,” as Olsen sings on the fateful “Heart Shaped Face,” she is forever finding ways to file down everyday truths to a finer point, drawing blood with every new prick. As she sighs over watery piano and fathomless reverb on the heartbreaking closer, “Pops,” “It hurts to start dreaming/Dreaming again.” But that pain is precisely what makes *MY WOMAN* so unforgettable, and so true.

Anyone reckless enough to have typecast Angel Olsen according to 2013’s ‘Burn Your Fire For No Witness’ is in for a sizable surprise with her third album, ‘MY WOMAN’. The crunchier, blown-out production of the former is gone, but that fire is now burning wilder. Her disarming, timeless voice is even more front-and-centre than before, and the overall production is lighter. Yet the strange, raw power and slowly unspooling incantations of her previous efforts remain, so anyone who might attempt to pigeonhole Olsen as either an elliptical outsider or a pop personality is going to be wrong whichever way they choose - Olsen continues to reign over the land between the two with a haunting obliqueness and sophisticated grace. Given its title, and track names like ‘Sister’ and ‘Woman’, it would be easy to read a gender-specific message into ‘MY WOMAN’, but Olsen has never played her lyrical content straight. She explains: “I’m definitely using scenes that I’ve replayed in my head, in the same way that I might write a script and manipulate a memory to get it to fit. But I think it’s important that people can interpret things the way that they want to.” That said, Olsen concedes that if she could locate any theme, whether in the funny, synth-laden ‘Intern’ or the sadder songs which are collected on the record’s latter half, “then it’s maybe the complicated mess of being a woman and wanting to stand up for yourself, while also knowing that there are things you are expected to ignore, almost, for the sake of loving a man. I’m not trying to make a feminist statement with every single record, just because I’m a woman. But I do feel like there are some themes that relate to that, without it being the complete picture.” Over her two previous albums, she’s given us reverb-shrouded poetic swoons, shadowy folk, grunge-pop band workouts and haunting, finger-picked epics. ‘MY WOMAN’ is an exhilarating complement to her past work, and one for which Olsen recalibrated her writing/recording approach and methods to enter a new music-making phase. She wrote some songs on the piano she’d bought at the end of the previous album tour, but she later switched it out for synth and/or Mellotron on a few of them, such as the aforementioned ‘Intern’. ‘MY WOMAN’ is lovingly put together as a proper A-side and a B-side, featuring the punchier, more pop/rock-oriented songs up front, and the longer, more reflective tracks towards the end. The rollicking ‘Shut Up Kiss Me’, for example, appears early on - its nervy grunge quality belying a subtle desperation, as befits any song about the exhaustion point of an impassioned argument. Another crowning moment comes in the form of the melancholic and Velvets-esque ‘Heart-shaped Face’, while the compelling ‘Sister’ and ‘Woman’ are the only songs not sung live. They also both run well over the seven-minute mark: the first being a triumph of reverb-splashed, ’70s country rock, cast along Fleetwood Mac lines with a Neil Young caged-tiger guitar solo to cap it off. The latter is a wonderful essay in vintage electronic pop and languid, psychedelic soul. Because her new songs demanded a plurality of voices, Olsen sings in a much broader range of styles on the album, and she brought in guest guitarist Seth Kauffman to augment her regular band of bass player Emily Elhaj, drummer Joshua Jaeger and guitarist Stewart Bronaugh. As for a producer, Olsen took to Justin Raisen, who’s known for his work with Charli XCX, Sky Ferreira and Santigold, as well as opting to record live to tape at LA’s historic Vox Studios. As the record evolves, you get the sense that the “My Woman” of the title is Olsen herself - absolutely in command, but also willing to bend with the influence of collaborators and circumstances. If ever there was any pressure in the recording process, it’s totally undetectable in the result. An intuitively smart, warmly communicative and fearlessly generous record, ‘MY WOMAN’ speaks to everyone. That it might confound expectation is just another of its strengths.

Rapper/singer Anderson .Paak’s third album—and first since his star turn on Dr. Dre’s *Compton*—is a warm, wide-angle look at the sweep of his life. A former church drummer trained in gospel music, Paak is as expressive a singer as he is a rapper, sliding effortlessly between the reportorial grit of hip-hop (“Come Down”) and the emotional catharsis of soul and R&B (“The Season/Carry Me”), live-instrument grooves and studio production—a blend that puts him in league with other roots-conscious artists like Chance the Rapper and Kendrick Lamar.

Bon Iver’s third LP is as bold as it is beautiful. Made during a five-year period when Justin Vernon contemplated ditching the project altogether, *22, A Million* perfects the sound alloyed on 2011’s *Bon Iver*: ethereal but direct, layered but stripped-back, as processed as EDM yet naked as a fallen branch. The songs here run together as though being uncovered in real time, with highlights—“29 #Strafford APTS,” “8 (circle)”—flashing in the haze.

'22, A Million' is part love letter, part final resting place of two decades of searching for self-understanding like a religion. And the inner-resolution of maybe never finding that understanding. The album’s 10 poly-fi recordings are a collection of sacred moments, love’s torment and salvation, contexts of intense memories, signs that you can pin meaning onto or disregard as coincidence. If Bon Iver, Bon Iver built a habitat rooted in physical spaces, then '22, A Million' is the letting go of that attachment to a place.

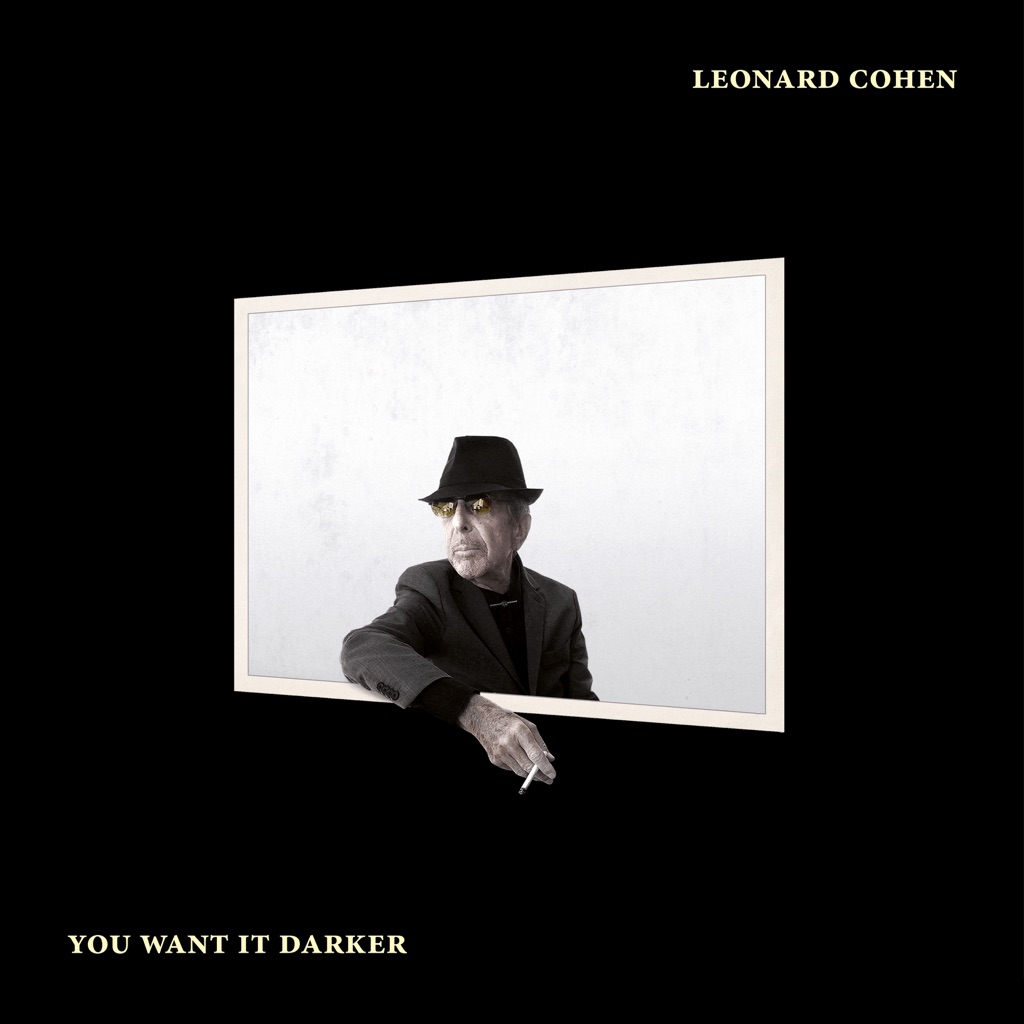

*You Want It Darker* joins *Old Ideas* and *Popular Problems* in a trio of gorgeous, ruminative albums that find Cohen settling his affairs, spiritual (“Leaving the Table”), romantic (“If I Didn’t Have Your Love”), and otherwise. At 35, he sounded like an old man—at 82, he sounds eternal.

Puberty is a game of emotional pinball: hormones that surge, feelings that ricochet between exhilarating highs and gut-churning lows. That’s the dizzying, intoxicating experience Mitski evokes on her aptly titled fourth album, a rush of rebel music that touches on riot grrrl, skeletal indie rock, dreamy pop, and buoyant punk. Unexpected hooks pierce through the singer/songwriter’s razor-edged narratives—a lilting chorus elevates the slinky, druggy “Crack Baby,” while her sweet singsong melodies wrestle with hollow guitar to amplify the tension on “Your Best American Girl.”

Ask Mitski Miyawaki about happiness and she'll warn you: “Happiness fucks you.” It's a lesson that's been writ large into the New Yorker's gritty, outsider-indie for years, but never so powerfully as on her newest album, 'Puberty 2'. “Happiness is up, sadness is down, but one's almost more destructive than the other,” she says. “When you realise you can't have one without the other, it's possible to spend periods of happiness just waiting for that other wave.” On 'Puberty 2', that tension is palpable: a both beautiful and brutal romantic hinterland, in which one of America’s new voices hits a brave new stride. The follow-up to 2014's 'Bury Me At Makeout Creek', named after a Simpsons quote and hailed by Pitchfork as “a complex 10-song story [containing] some of the most nuanced, complex and articulate music that's come from the indiesphere in a while,” 'Puberty 2' picks up where its predecessor left off. “It's kind of a two parter,” explains Mitski. “It's similar in sound, but a direct growth [from] that record.” Musically, there are subtle evolutions: electronic drum machines pulse throughout beneath Pixies-ish guitars, while saxophone lights up its opening track. “I had a certain confidence this time. I knew what I wanted, knew what I was doing and wasn't afraid to do things that some people may not like.” In terms of message though, the 25-year-old cuts the same defiant, feminist figure on 'Puberty 2' that won her acclaim last time around (her hero is MIA, for her politics as much as her music). Born in Japan, Mitski grew up surrounded by her father's Smithsonian folk recordings and mother's 1970s Japanese pop CDs in a family that moved frequently: she spent stints in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Malaysia, China and Turkey among other countries before coming to New York to study composition at SUNY Purchase. She reflects now on feeling “half Japanese, half American but not fully either” – a feeling she confronts on the clever 'Your Best American Girl' – a super-sized punk-rock hit she “hammed up the tropes” on to deconstruct and poke fun at that genre's surplus of white males. “I wanted to use those white-American-guy stereotypes as a Japanese girl who can't fit in, who can never be an American girl,” she explains. Elsewhere on the record there's 'Crack Baby', a song which doesn't pull on your heartstrings so much as swing from them like monkey bars, which Mitski wrote the skeleton of as a teenager. As you might have guessed from the album's title, that adolescent period is a time of her life she doesn't feel she's entirely left behind. “It came up as a joke and I became attached to it. 'Puberty 2'! It sounds like a blockbuster movie” – a nod to the horror-movie terror of adolescence. “I actually had a ridiculously long argument whether it should be the number 2, or a Roman numeral.” The album was put together with the help of long-term accomplice Patrick Hyland, with every instrument on record played between the two of them. “You know the Drake song 'No New Friends'? It's like that. The more I do this, the more I close-mindedly stick to the people I know,” she explains. “I think that focus made it my most mature record.” Sadness is awful and happiness is exhausting in the world of Mitski. The effect of 'Puberty 2', however, is a stark opposite: invigorating, inspiring and beautiful.

On their final album, Q-Tip, Phife Dawg, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and Jarobi rekindle a chemistry that endeared them to hip-hop fans worldwide. Filled with exploratory instrumental beds, creative samples, supple rhyming, and serious knock, it passes the headphone and car stereo test. “Kids…” is like a rap nerd’s fever dream, Andre 3000 and Q-Tip slaying bars. Phife—who passed away in March 2016—is the album’s scion, his roughneck style and biting humor shining through on “Black Spasmodic” and “Whateva Will Be.” “We the People” and “The Killing Season” (featuring Kanye West) show ATCQ’s ability to move minds as well as butts. *We got it from Here... Thank You 4 Your service* is not a wake or a comeback—it’s an extended visit with a long-missed friend, and a mic-dropping reminder of Tribe’s importance and influence.

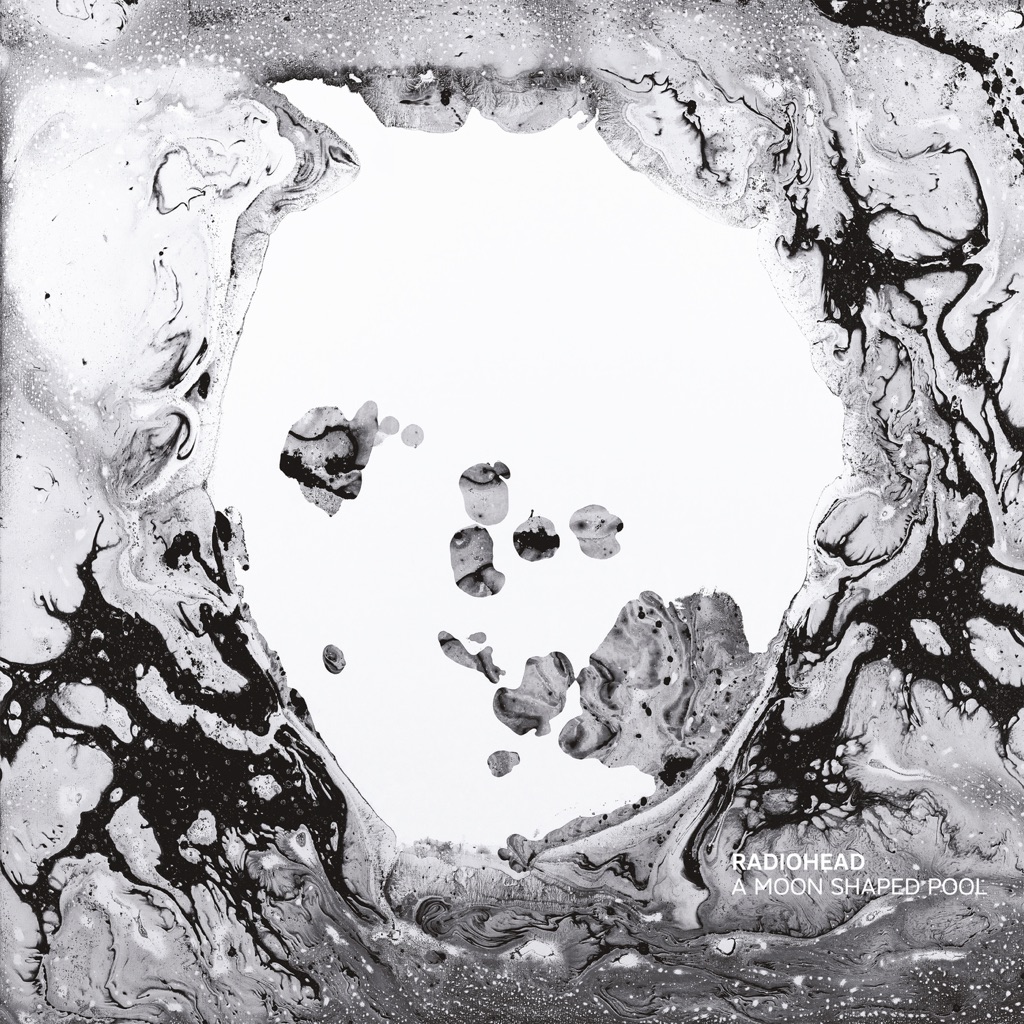

Radiohead’s ninth album is a haunting collection of shapeshifting rock, dystopian lullabies, and vast spectral beauty. Though you’ll hear echoes of their previous work—the remote churn of “Daydreaming,” the feverish ascent and spidery guitar of “Ful Stop,” Jonny Greenwood’s terrifying string flourishes—*A Moon Shaped Pool* is both familiar and wonderfully elusive, much like its unforgettable closer. A live favorite since the mid-‘90s, “True Love Waits” has been re-imagined in the studio as a weightless, piano-driven meditation that grows more exquisite as it gently floats away.

Solemn, wrenching and totally stunning; *Freetown Sound* proves Dev Hynes has become one of pop’s great alchemists. Named after Sierra Leone’s capital (his father’s hometown), it’s an album, says Hynes, “for the under-appreciated.” Its dominant themes—exquisite heartbreak and displacement—check that description out. The music—scintillating, poised, and sticky synth-soul—make it a record for the under-appreciated to hold very close. Highlights are bountiful, but the ecstatic “Best To You” receives a glorious Real Thing assist and “Hadron Collider”, a mercurial Nelly Furtado ballad, will long stay with you.

Freetown Sound is the third album from Devonté Hynes aka Blood Orange. Written and produced by Hynes, Freetown Sound is a tour de force, a pastiche of Hynes’ past, present, and future that melds his influences with his own established musical voice. For well over a decade, Devonté Hynes has proven himself a virtuoso of versatility, experimenting with almost every conceivable musical genre under a variety of monikers. After moving to New York City in the mid-2000s, Hynes became Blood Orange, plumming the oeuvres of the city’s musical legends to create a singular style of urgent, delicate pop music. Freetown Sound, which follows 2011’s Coastal Grooves and 2013’s breakthrough Cupid Deluxe, builds upon everything Hynes has done as an artist, resulting in the most expansive artistic statement of his career. Drawing from a deep well of techniques and references, the album unspools like a piece of theater, evoking unexpected communions of moods, voices, and eras. Freetown Sound derives its name from the birthplace of Hynes’ father, the capital of Sierra Leone. Thematically, it is profoundly personal and unapologetically political, touching on issues of race, religion, sex, and sexism over 17 shimmering songs.

On the gritty, star-studded *Blank Face LP*, ScHoolboy Q is at his very best. Through 17 tracks of heavy-lidded gangsta rap, the incisive L.A. native joins forces with guests both legendary (E-40, Jadakiss, Tha Dogg Pound) and soon-to-be (Vince Staples, Anderson. Paak). “Robbin’ your kids too,” he says on “Groovy Tony / Eddie Kane,” a haunting double feature. “My heart a igloo.”

You have no right to be depressed You haven’t tried hard enough to like it There are two kinds of great lyrics. The first is the banger/anthem catch phrase: "Normal life is borin' / but superstardom is close to post-mortem." The second is more complex (and more rarely found): "Like a bird on a wire / Like a drunk in a midnight choir/I have tried in my way to be free" — with ideas, themes, and personae unfolding over the course of songs, contradicting each other, confronting the listeners' preconceptions, like Pete Townsend, Morrissey, or Kendrick Lamar. Will Toledo, the singer/songwriter/visionary of Car Seat Headrest, is adept at both, having developed them over the course of his eleven college-recorded Bandcamp albums and his retrospective collection last fall, Teens of Style. With Teens of Denial, his first real "studio" album with an actual band, Toledo moves from bedroom pop to something approaching classic-rock grandeur and huge (if detailed and personal) narrative ambitions, with nods to the Cars, Pavement, Jonathan Richman, Wire, and William Onyeabor. "I’m so sick of / (Fill in the blank)" or "It’s more than you bargained for / But it's a little less than what you paid for" are more than smart, edgy slogans. Over the course of Teens of Denial's 11 songs, Will narrates a journey with his mysterious companion/alter-ego Joe that addresses big themes (personal responsibility, existential despair, the nature of identity, the Bible, heaven) and small ones (Air Jordans, cops, whether to have one more beer, why he lost his backpack). By turns tender and caustic, empathetic and solipsistic, literary and vernacular, profound and profane, self-loathing and self-aggrandizing, he conjures a specifically 21st century mindset, a product of information overload, the loneliness it can foster, and the escape music can provide. “Fill in The Blank,” the mission statement of the album, kicks things off — it’s a fist-pumping anthem about feeling lousy in an ill-defined way, the fear of settling into a routine of futility, and not wanting to deal with it. Although it’s oddly joyful sounding, Toledo considers it the introduction to his angriest record yet. In that vein, “Vincent,” “Hippie Powers,” and “Connect The Dots” are about both fighting to hold your place in the crowd and to hold your drink, as well as DIY college house shows, and having no one to dance with, respectively. Initially similar, "Drunk Drivers/Killer Whales” veers off in surprising directions, each piece flush with huge, irony-free hooks. At the heart of the album sits the 11:32 "Ballad of the Costa Concordia," which has more musical ideas than most whole albums (and at that length, it uses them all). Horns, keyboards, and elegant instrumental interludes set off art-garage moments; vivid vocal harmonies follow punk frenzy. The selfish captain of the capsized cruise liner in the Mediterranean in 2013 becomes a metaphor for struggles of the individual in society, as experienced by one hungover young man on the verge of adulthood. Teens of Denial refracts Toledo's particular, personal story of one difficult year through cultural touchstones such as the biography of Frank Sinatra, the evolution of the Me Generation as seen in Mad Men and elsewhere, plus elements of eastern and western theology. The whole thing flaunts a kind of conceptual, lyrical, and musical ambition that has been missing from far too much 21st-century music. I won’t go down with this shit I will put my hands up and surrender there will be no more flags above my door I have lost, and always will be There are two kinds of great lyricists. The first kind is one one you find in books, canonized by time and a lifetime of expression. The second has it all in front of him. Meet Will Toledo. Or at least one version of him.

A confessional autobiography and meditation on being black in America, this album finds Solange searching for answers within a set of achingly lovely funk tunes. She finds intensity behind the patient grooves of “Weary,” expresses rage through restraint in “Mad,” and draws strength from the naked vulnerability of “Where Do We Go.” The spirit of Prince hovers throughout, especially over “Junie,” a glimmer of merriment in an exquisite portrait of sadness.

The avant garde Norwegian throws open a ghostly sonic sketchbook on this complex sixth album. Taking vampirism, gore, and femininity as her stated themes, Hval uses everything from percussive panting (the compellingly sinister “In The Red”) to distant, discordant horns (“Untamed Region”) to conjure challenging, dark dreamscapes. Thankfully, she never forgets the tunes. “The Great Undressing” is a propulsive art-pop jewel, and “Secret Touch” pits Hval’s brittle falsetto against hissing, addictive trip hop.

Jenny Hval’s conceptual takes on collective and individual gender identities and sociopolitical constructs landed Apocalypse, girl on dozens of year end lists and compelled writers everywhere to grapple with the age-old, yet previously unspoken, question: What is Soft Dick Rock? After touring for a year and earning her second Nordic Prize nomination, as any perfectionist would, Hval immediately went back into the studio to continue her work with acumen noise producer Lasse Marhaug, with whom she co-produces here on Blood Bitch. Her new effort is in many respects a complete 180° from her last in subject matter, execution and production. It is her most focused, but the lens is filtered through a gaze which the viewer least expects.

KAYTRANADA\'s debut LP is a guest-packed club night of vintage house, hip-hop, and soul. The Montreal producer brings a rich old-school feel to all of these tracks, but it’s his vocalists that put them over the edge. AlunaGeorge drops a sizzling topline over a swervy beat on “TOGETHER,” Syd brings bedroom vibes to the bassline-driven house tune “YOU’RE THE ONE,” and Anderson .Paak is mysterious and laidback on the hazy soundscape “GLOWED UP.” And when Karriem Riggins and River Tiber assist on the boom-bap atmospheres of “BUS RIDE,\" they simply cement the deal.

On No One Deserves Happiness, The Body’s Chip King and Lee Buford set out to make “the grossest pop album of all time.” The album themes of despair and isolation are delivered by the unlikely pairing of the Body’s signature heaviness and 80s dance tracks. The Body can emote pain like no other band, and their ability to move between the often strict confines of the metal world and the electronic music sphere is on full display throughout No One Deserves Happiness, an album that eludes categorization. More then any of their genre-defying peers, The Body does it without softening their disparate influences towards a middle ground, but instead through a beautiful combining of extremes. No One Deserves Happiness is an album that defies definition and expectations, standing utterly alone. Buford and King are outliers at their core, observing the world as if apart from it. They strive for music without a category. They embody many contrasts. They are open and playful as well as thoughtful and disciplined. Live, they deliver punishing volume and scale with their spare duo set up, expanding their sound through a complex set of effects on both guitar and drums. For records, they approach things entirely differently and expand their group in the studio to include Seth Manchester and Keith Souza from Machines with Magnets (their long-time studio), as well as Chrissy Wolpert of The Assembly of Light Choir. The list of instruments used on No One Deserves Happiness is an unexpected collection that includes 808 drum machine, a cello and a trombone. The band employs instruments in their unprocessed state for the simple beauty of the sound, and then in equal measure push them to their most extreme (for example, the sounds at the end of “The Fall and the Guilt” are created by a guitar and a cello). Because they create an entirely singular sound, The Body is in high demand for collaborations with artists across the musical spectrum, from The Bug to Full of Hell to The Haxan Cloak and beyond. They build albums that are as lush and dense as a rainforest and as unforgiving. Building an album as layered as No One Deserves Happiness is a complex process. Striving for harshness, dynamics and detail all at once poses some technical challenges: It requires that tracks are built up, deconstructed, processed and re-built. Manchester explains that as an engineering team for The Body, Machines with Magnets must always consider the mix — they never go in and record the basics and then mix it. In order to get the immersive experience that is No One Deserves Happiness, they must experiment with and constantly re-evaluate every construct. While they do employ an 808 on this album, they use pre-fabricated samples very sparingly. To get the contrast they are looking for, they experiment with a huge variety of their own sound samples and varying levels of distortion. Reprocessing a few samples of a track can often result in a remix to retain the balance and dynamics they are looking for. Delicate, ethereal vocals, courtesy of Wolpert and Maralie Armstrong (who wrote and sings the lyrics for “Adamah” and contributes vocals at the end of “Shelter Is Illusory”) sharply juxtapose King’s distinctive, hellish cries. Album opener “Wanderings” is the perfect introduction to No One Deserves Happiness: Wolpert’s angelic calls to “go it alone” build until utter despair takes over, her voice drowned in guitar distortion, and as it is swallowed, we hear the desperate cries of Chip King. The Body then completely switches approaches, starting again with bare drums, but this time more processed and more industrial. The march is quickly augmented by electronics and King’s distant shrieks — this continues to build to the apex of Wolpert’s vocals rising from the oppressiveness and elevating it with her melodies. The contrasting composition and employment of textures on these two songs highlight the Body’s songwriting and arrangement skills. Each track is at once melodic and bleak, employing many of the same instruments but never in the same manner. The band’s musical tastes are broad, and that is reflected in the wide variety of inspirations they cite for the tracks on No One Deserves Happiness. “Two Snakes” started with a bass line that was inspired by Beyoncé and went through several mutations as the band remixed and reprocessed core elements, vocal melodies morphing into distorted keys, all carried by the foundational bass line. The core duo of The Body has clear ideas of what they want to achieve, but they are completely open to ideas on the execution. This collaborative, open approach allows for a lot of creative input into the building blocks or sounds of a composition that The Body then meticulously arranges. In the same manner as the music, the lyrics are inspired by a variety of literary reference points, from the spoken word piece on “Prescience,” written by Édouard Levé, to the Joan Didion quote inscribed in the album artwork. The Didion passage succinctly sums up an overriding theme of loss and isolation: “A single person is missing for you, and the whole world is empty.” In the past two years alone, The Body has joined forces with the metal bands Thou, Sandworm, and Krieg, recorded with Wrekmeister Harmonies, and collaborated with electronic producer The Haxan Cloak. They are currently working on a collaboration with The Bug and grindcore band Full of Hell. They have toured with Neurosis (playing large venues) and toured with Sandworm (playing house shows). This unexpected list of collaborators and unpredictable touring approach further emphasizes the demand for the band’s distinctive sound and their open, explorative nature.

More trauma and travails with the magnetic Detroit MC. Like *XXX* and *Old* before it, *Atrocity Exhibition* plays like a nightmare with punchlines, the diary of a hedonist who loves the night as much as he hates the morning after. “Upcoming heavy traffic/say ya need to slow down, ’cause you feel yourself crashing,” Brown raps on “Ain’t it Funny,” a feverish highlight. “Staring the devil in the face but ya can’t stop laughing.”

Jamila Woods surrounds herself with the things she loves, things like Lucille Clifton’s poetry or letters from her grandmother or the late 80s post-punk of The Cure. “It’s just powerful to me to know the lineage and influences going into the making of the song,” Jamila says. That lineage–fragments of her life and loves–helped structure the progressive, delicate and minimalist soul of HEAVN, her debut solo album released in the summer of 2016. “It’s like a collage process,” she says. “It’s very enjoyable to me to take something I love and mold it into something new.” A frequent guest vocalist in the hip-hop, jazz and soul world, Jamila has emerged as a once-in-a-generation voice on her soul-stirring debut. Hailed by Pitchfork as, “a singular mix of clear-eyed optimism and Black girl magic,” HEAVN is the culmination of more than two decades’ worth of musical performances, creative remixing, haunted memories and her unique “collage” writing process. “I think of songs as physical spaces,” Jamila says. “Writing a song feels like decorating my space with things that make me happy or reflect who I am.” The message of HEAVN, the album, and Jamila, the musician and poet, are clear: all parts strengthen the whole. Born and raised on the Southside of Chicago, Woods grew up in a family of music lovers. She was a member of her grandmother’s church choir as well as the Chicago Children’s Choir and often sat next to her parents’ speakers, singing along to their sizeable music collection while surrounding herself with things she admired. But it took a surprise poetry class with the high school arts program Gallery 37 for Jamila to finally find her metaphorical and literal voice. “Through poetry, I realized you are the expert of your own experience,” she says. “You can tell your story the best and no one else can tell it for you. You can focus on what you lack, comparing yourself to other people, or you can focus on what you can do right now with your voice.” Her interest in poetry grew with age, taking her to Brown University, where she often participated in open mics. But music still lingered in the background even if she wasn’t necessarily confident of her skills. “I definitely always wanted to be a performer or be a singer,” Jamila said. “I always had that in my mind, but I didn’t think I had the voice of a solo artist.” She joined the acapella group Shades of Brown where she learned how to arrange music for her peers. It became a skill she later utilized when crafting her own songs. “I thought about the parts everyone would sing and that really influenced the way I started to write songs,” she offers. Music–like poetry– is personal, she says: “It became a way to stop hiding, to actually be the most honest with myself through writing. It helps me check in with myself.” And that honesty translated to HEAVN, an album she describes as a collection of, “nontraditional love songs pushing the idea of what makes a love song.” Here, you’ll find the bits and pieces of her past and present that make Jamila: family, the city of Chicago, self-care, the black women she calls friends. In 2016, Chicago-based hip-hop label Closed Sessions released HEAVN. Working with Closed Sessions gave Jamila a home to help craft a complete, singular body of work. “That’s been the coolest thing,” she says. “Just being connected with so many people in Chicago. I like that they’re local.” HEAVN features a variety of producers, including oddCouple, a fellow Closed Sessions signee who produced five of the album’s 12 tracks. “Working with oddCouple was when I really started thinking of [HEAVN] as an album,” she adds. Other producers on the album include Peter Cottontale and even Jamila’s sister. In 2017, Jamila partners with Jagjaguwar and Closed Sessions to re-release the critically-acclaimed HEAVN. On the album’s title track, which samples the Cure’s “Just Like Heaven,” Jamila explores how black people’s history influences their ability to love each other. “How do we love in our current situation, with the everyday violences we have to endure?” she asks. “Holy” connects to Jamila’s life growing up in church, sampling a gospel song and utilizing a psalm structure to talk about self love. “In church, there was a lot of emphasis on love–like love your neighbor, love God–but not self love,” she says. “When I wrote ‘Holy,’ I wanted to remember to take care of myself. It was an affirmation mantra for me.” Elsewhere, Jamila plays with contrast to tell a bigger story. On “VRY BLK,” she uses black girl hand clap games to talk about police brutality. “It might sound innocent, but it’s really not,” Jamila says. “BLK Girl Soldier,” a song Jamila describes as a partner to “VRY BLK,” focuses on solidarity. “It’s very prideful,” Jamila says. “I’m talking about this violence that happens, but not staying in a place of feeling victimized.” Jamila is an artist of substance. Her music, crafted with a sturdy foundation of her passions and influences, gets to the heart of things. True and pure in its construction and execution, it is also the best representation of Jamila herself: strong in her roots, confident in her ideas, and attuned to the people, places and things shaping her world.

Indie-pop miniaturist Frankie Cosmos makes music like minimal sculpture or haiku: radically simple but deceptively complicated at the same time. Her second studio album, *Next Thing*, is by turns tender and funny, innocent and wise, often within the space of the same brief line. (Take this one, from “Fool”: “Once I was happy, you found it intriguing/Then you got to me and left me bleeding.”) And though her songs are brief and the arrangements simple, the album feels surprisingly complete—the product of someone who knows exactly what they want to say and doesn’t waste time with one word more.

The first sound on Nicolas Jaar’s new record Sirens is a flag whipping in a gale. It’s the sort of sound you don’t realize you know until you hear it. But it’s unmistakable. And pregnant with meaning: nation, memory, conquest—but also frailty, a delicate thing buffeted by mercurial winds. The second sound is breaking glass. Nicholas Jaar has been busy. Since 2015, he’s released Nymphs, a series of four EPs, and Pomegranates, an alternate soundtrack to Sergei Parajanov's 1969 film The Colour of Pomegranates. If Nymphs and Pomegranates represent two sides of the coin of Jaar’s work—club and experimental ambient respectively—Sirens, he says, is“the coin itself”: the terrain, the constraints, the material conditions from which the others emerge. Sirens is animated by an ambivalence at the heart of American music: that, in some fundamental sense, the history of American popular culture is a history of theft. The six lush tracks move seamlessly from rock to reggaetón to doo-wop, each exhibiting Jaar’s signature sensitivity to restraint and exuberance, disjuncture and groove, comfort and disquiet. Foregrounded throughout is the question of what these forms—artifacts of empire and its resistance both—can do for us today. Jaar, whose parents lived under dictatorship in Chile and whose grandparents are Palestinian, ascribes to Víctor Jara’s philosophy that you’re making political music whether you want to or not. The injustices of the past weigh heavily on the living, structuring the possibilities of the present. As Jaar sings, “we’re all waiting for the old thoughts to die.” For now, they’re our thoughts too. Jaar composed and recorded all the music on Sirens himself, with one exception: a sample of the Andean folk song “Lagrimas”—tears—which appears, almost unadorned, in the middle of “No,” the fourth track on Siren. “No” recalls the Chilean national plebiscite of 1988, when artists and activists organized millions of Chileans to vote “no”to the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. The song is a meditation on the seeming futility of protest against systems that structure our very reality. Over a loping reggaetón beat, Jaar laments, “ya dijimos no, pero el Si está en todo.”We already said no, but the Yes is everywhere. The songs on Sirens are fiercely critical, but they are generous too, even loving. “I made these songs to play for my friends, for people going to see music,” Jaar says. The place he wants to be is liminal: between the precious sense of freedom that only music can provide, and the reality that there’s no escape; between “knowing that we’re trying to get away and knowing that we can’t. That maybe,” he says, “we shouldn’t.” After the glass shatters, a rush of sound, fluttering pianos and synth mingle with the shards. The shimmering music billows and quiets. There is calm. Then the glass shatters again.

Say what it is... Its so impossible... Pinegrove’s Evan Stephens Hall drawls on the album’s highlight track. The line’s meant as an examination of language’s intrinsic hardships, but it’s also an apt description of the record itself. Adopting genres and influences at will, *Cardinal* unfolds through lo-fi indie shouts, country twang, and chunky-riffed pop rock choruses. Each turn of phrase, guitar tone, and harmony feels delightfully stripped-down, comfortably unrushed, and well-lived-in.

The Japanese group BABYMETAL are premised upon the unlikeliest of contrasts: Vocalists SU-METAL, YUIMETAL, and MOAMETAL harmonize sweetly while bludgeoning riffs crash and explode, and they apply that approach to a wide range of subgenres on their second album. The majestically bouncy “YAVA!” races along on a ska-inflected beat, the jittery “Gj!” nods to nu-metal, and “No Rain, No Rainbow” is a straight-up power ballad, complete with guitar solo. On “Awadama Fever,” which combines grinding guitars and hyperactive drums with a triumphant chorus, BABYMETAL further compress the distance between metal and pop.

Soundtracking “rousing sport montages” was not an ambition for Texan instrumental rockers Explosions In the Sky with their sixth album. We’re not sure they’ll avoid that honor entirely—“The Ecstatics” and “Tangle Formations” are spine-tingly enough to accompany most last-second heroics—but this panoramic, foreboding set certainly hits harder than previous work. “Disintegration Anxiety” is a fuzzy, muscular work-out, the ambient and glitchy “Losing the Light” haltingly unsettling, while “Colours in Space” cycles through the band’s full range of melodic shades before allowing “Landing Clifs” its gorgeous comedown.

The Wilderness is Explosions In The Sky's sixth album, and first non-soundtrack release since 2011’s Take Care, Take Care, Take Care. True to its title, The Wilderness explores the infinite unknown, utilizing several of the band’s own definitions of “space" (outer space, mental space, physical geography of space) as compositional tools. The band uses their gift for dynamics and texture in new and unique ways—rather than intuitively fill those empty spaces, they shine a light into them to illuminate all the colors of the dark. From the electronic textures of the opening track to the ambient dissolve of closer “Landing Cliffs,” The Wilderness is an aggressively modern and forward-thinking work—one that wouldn’t seem the slightest bit out of place on a shelf between original pressings of Meddle and Obscured By Clouds. It is an album where shoegaze, electronic experimentation, punk damaged dub, noise, and ambient folk somehow coexist without a hint of contrivance—and cohere into some of the most memorable and listenable moments of the band’s expansive body of work—“proper” studio albums and major motion picture soundtracks alike. The progressive ambience of early Peter Gabriel, the triumphant romanticism of The Cure in their prime, and the more melancholy moments of Fleetwood Mac all inform the curious beauty of The Wilderness. The uncanny ability to reconcile the tension between discordant, nightmarish cacophony and laid-back, Laurel Canyon-inspired folk-rock is a cornerstone of this album, and the center of Explosions In The Sky's remarkable evolution. If The Earth Is Not A Cold Dead Place was the defining album of Explosions In The Sky's career, The Wilderness is the band's [re]defining album.

In honor of their late mother, brothers Joe and Mario Duplantier of French metallurgists Gojira respond to tragedy with some of the most emotional songs of their career. Epic suites yield to sharpened body blows. For every pummeling track like “Silvera” and “The Cell” there are moving salutes like “The Shooting Star” and “Yellow Stone,” where sadness and depression transform into submission and ultimately salvation.

The Range is a digital archaeologist, unearthing deep musical emotion from the obscure sounds he digs up on YouTube. For *Potential*, the Brooklyn producer searched for voices in particular, incorporating them into his alternately lush and dank masses of beats and bass. Anonymous singsong flits ethereally through “Florida,” which skips and struts over thick kicks accessorized with clipped steel-drum ping and banjo pluck. Others, like “1804,” revolve around rapping or toasting by unknown MCs whose words cut a path through nostalgic yet novel combinations of jungle, dubstep, grime, and ambient music.

Whitney’s debut is a haunting set of ‘60s guitar pop. Taking pages from Byrds ballads (“Light Upon the Lake”), pre-psychedelic Beatles (“Golden Days”), and the more placid side of soul (“Dave’s Song”), the duo—comprising former members of Smith Westerns and Unknown Mortal Orchestra—sound cheerful but bittersweet, muted by a sense of melancholy that gives drummer/vocalist Julien Ehrlich’s falsetto a sneaky, surprising depth. Even the album’s most upbeat moment, “The Falls,” feels less like it’s looking forward to something, and more like it’s looking back.

Whitney make casually melancholic music that combines the wounded drawl of Townes Van Zandt, the rambunctious energy of Jim Ford, the stoned affability of Bobby Charles, the American otherworldliness of The Band, and the slack groove of early Pavement. Their debut, ‘Light Upon the Lake’, is due in June on Secretly Canadian, and it marks the culmination of a short, but incredibly intense, creative period for the band. To say that Whitney is more than the sum of its parts would be a criminal understatement. Formed from the core of guitarist Max Kakacek and singing drummer Julien Ehrlich, the band itself is something bigger, something visionary, something neither of them could have accomplished alone. Ehrlich had been a member of Unknown Mortal Orchestra, but left to play drums for the Smith Westerns, where he met guitarist Kakacek. That group burned brightly but briefly, disbanding in 2014 and leaving its members adrift. Brief solo careers and side-projects abounded, but nothing clicked. Making everything seem all the more fraught: both of them were going through especially painful breakups almost simultaneously, the kind that inspire a million songs, and they emerged emotionally bruised and lonelier than ever. Whitney was born from a series of laidback early-morning songwriting sessions during one of the harshest winters in Chicago history, after Ehrlich and Kakacek reconnected - first as roommates splitting rent in a small Chicago apartment and later as musical collaborators passing the guitar and the lyrics sheet back and forth. “We approached it as just a fun thing to do. We never wanted to force ourselves to write a song. It just happened very organically. And we were smiling the whole time, even though some of the songs are pretty sad.” The duo wrote frankly about the break-ups they were enduring and the breakdowns they were trying to avoid. Each served as the other’s most brutal critic and most sympathetic confessor, a sounding board for the hard truths that were finding their way into new songs like “No Woman” and “Follow,” a eulogy for Ehrlich’s grandfather. In exorcising their demons they conjured something else, something much more benign—a third presence, another personality in the music, which they gave the name Whitney. They left it singular to emphasize its isolation and loneliness. Says Kakacek, “We were both writing as this one character, and whenever we were stuck, we’d ask, ‘What would Whitney do in this situation?’ We personified the band name into this person, and that helped a lot. We wrote the record as though one person were playing everything. We purposefully didn’t add a lot of parts and didn’t bother making everything perfect, because the character we had in mind wouldn’t do that.” In those imperfections lies the music’s humanity. Whilst they demoed and toured the new songs, they became more aware of the perfect imperfections of the songs, and needing to strike the right balance, they eventually made the trek out to California, where they recorded with Foxygen frontman and longtime friend, Jonathan Rado. They slept in tents in Rado’s backyard, ate the same breakfast every morning at the same diner in the remote, desolate and completely un-rock n roll San Fernando Valley, whilst they dreamt of Laurel Canyon, or maybe The Band’s hideout in Malibu, or Neil Young’s ranch in Topanga Canyon. The analog recording methods, the same as used by their forebearers, allowed them to concentrate on the songs themselves and create moments that would be powerful and unrepeatable. “Tape forces you to get a take down,” says Kakacek. “We didn’t have enough tracks to record ten takes of a guitar part and choose the best one later. Whatever we put down is all we had. That really makes you as a musician focus on the performance.” The sessions were loose, with room for improvisation and new ideas, as the band expanded from that central duo into a dynamic sextet (septet if you count their trusty soundman). And that’s what you hear – Whitney is the sound of that songwriting duo expanding their group and delivering the sound of a band at their freest, their loosest, their giddiest. Classic and modern at the same time, they revel in concrete details, evocative turns of phrase, and thorny emotions that don’t have exact names. These ten songs on 'Light Upon the Lake' sound like they could have been written at any time in the last fifty years. Ehrlich and Kakacek emerge as imaginative and insightful songwriting partners, impressive in their scope and restraint as they mold classic rock lyricism into new and personal shapes without sound revivalist or retro. “I’m searching for those golden days.” sings Ehrlich, with a subtle ripple of something that sounds like hope, on the track “Golden Days”. It’s a song that defines Whitney as a band. “There’s a lot of true feeling behind these songs,” says Ehrlich. “We wanted them to have a part of our personalities in them. We wanted the songs to have soul.”

Eight albums and 20 years deep, a determination to stretch metal’s boundaries remains sacrosanct for the Californians. Another key Deftones tenet—bonding aggression with vulnerability—rages throughout an album that captures a band invigorated and reflective. “There’s a new strange, godless demon awake inside me” sings Chino Moreno on cacophonous opener “Prayers / Triangles” and it sets the rapturous tone. The juddering “Doomed User” amps up the drama while “Geometric Headdress”, “(L)mirl” and “Phantom Bride” are piercing examples of the band’s propensity for melody.

Mothers couldn’t be more suited to the indie music mecca of Athens, Georgia. Their off-kilter first album is an ideal mixture of quirk and gravitas, with Kristine Leschper’s hypnotic warble elevating the beautiful finger-picked arrangements of sweet daybreak serenades like “Too Small For Eyes.” But they dip into heavier vibes on tunes like “Copper Mines” and “Lockjaw,” which crank up the overdriven guitars amid the sway and swirl. Moments like these add up to a debut that’s touching, mournful, vibrant, and completely captivating.

The Baton Rouge rapper Kevin Gates has never been much for jokes. Earnest, unsparing, and intensely personal, his full-length major-label is a downcast trip through tales of the grind (“La Familia”) romantic woes (“Pride”), and the trials of balancing the two (“2 Phones”). He delivers it all with enough charm and hope to keep things from getting too dark or gritty. “Man in the mirror you way outta order,” he raps on “The Truth”—fitting words for an artist who named his album (and his daughter, for that matter) after an Arabic word meaning \"to improve.\"

Thugga’s agility and anguish come together in a high-impact performance for the ages. He’s always been lithe, but witness the rapper’s snakelike vocals slide through “Wyclef Jean” and “Swizz Beats,” both built on the subliminal rumbles of dub and dancehall. While he digs into “Future Swag” with wolfish gusto, his fractured croon finds home in the sore-hearted hedonism of “Riri.”

Mailorder (US) - www.dirtnaprecs.com/website/ Mailorder (UK/EU) - cargorecordsdirect.co.uk/products/martha-blisters-in-the-pit-of-my-heart iTunes - geni.us/h7oJh Amazon (CD) - geni.us/g7TG Amazon (Vinyl) - geni.us/CxdqY5

White Lung’s dizzyingly breakneck *Paradise* finds them more fiery than ever, with catchy punk hooks alongside deliriously shred-heavy guitar attacks. Mish Barber-Way’s ferocious vocals steal the show on songs like the dark, metal-tinged “Demented.” Guitarist Kenneth William’s ridiculously quick-fingered six-string heroics burn hotter than a scorpion pepper on furious opener “Dead Weight.” The heavy-hitting four-piece save their raucous best for last with the title track—a thick ‘n’ thrashy rampage about the joys of grabbing your lover and leaving it all behind.

After the critically acclaimed release Deep Fantasy (2014), White Lung return with their fourth album Paradise. Vocalist Mish Barber-Way, guitarist Kenneth William and drummer Anne-Marie Vassiliou, reconnected in Los Angeles to work with engineer and producer Lars Stalfors (HEALTH, Cold War Kids, Alice Glass). In October of 2015, White Lung spent a month in the studio, working closely with Stalfors to challenge what could be done with their songs. “I wanted it to sound new. I wanted a record that sounded like it was made in 2016”, says William of his mindset. Bringing all the energy, unique guitar work and lyrical prowess Rolling Stone, Pitchfork, NME have praised them for in the past few years, White Lung curated their songs with a new pop sensibility. Mixed by Stalfors and later mastered by Joe LaPorta, Paradise is their smartest, brightest songwriting yet. “There’s this stupid attitude that only punks have where it’s uncool to become a better song writer,” says Barber-Way, “In no other musical genre are your fans going to drop you when you start progressing. That would be like parents being disappointed in their child for graduating from kindergarten to the first grade. Paradise is the best song writing we have ever done, and I expect the next record to be the same. I have no interest in staying in kindergarten.”

How do you make a grand statement when you have nothing left to prove? On *Post Pop Depression*, Iggy Pop huddles with Queens of the Stone Age’s Josh Homme, Dead Weather’s Dean Fertita, and Arctic Monkeys’ Matt Helders. The results are wiry, muscular, and shape-shifting, much like Iggy himself. His unctuous cool drips all over slow-burners like “American Valhalla” and “Break Into Your Heart.\" “Vulture” sounds like Iggy reading a twisted campfire story. “Paraguay” and “Chocolate Drops” are as poignant as they are profane. Nearly 50 years from where it all began, *Post Pop Depression* proves that the punk pioneer can still cause a ruckus.