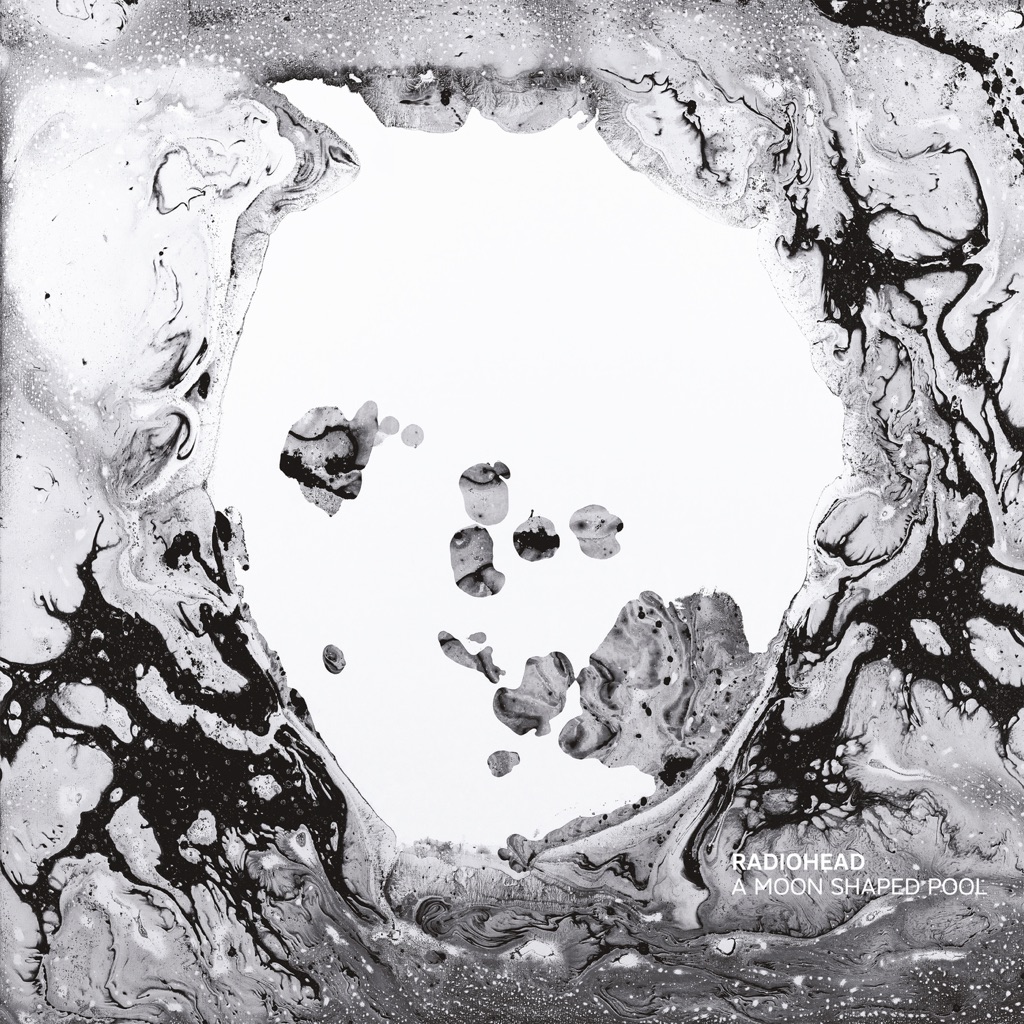

Uproxx's 20 Best Albums Of 2016

From the folk album you've barely heard to your most-played pop record, here's our ranking of the 2016's best albums.

Published: December 12, 2016 15:00

Source

In the four years between Frank Ocean’s debut album, *channel ORANGE*, and his second, *Blonde*, he had revealed some of his private life—he published a Tumblr post about having been in love with a man—but still remained as mysterious and skeptical towards fame as ever, teasing new music sporadically and then disappearing like a wisp on the wind. Behind great innovation, however, is a massive amount of work, and so when *Blonde* was released one day after a 24-hour, streaming performance art piece (*Endless*) and alongside a limited-edition magazine entitled *Boys Don’t Cry*, one could forgive him for being slippery. *Endless* was a visual album that featured the mundane beauty of Ocean woodworking in a studio, soundtracked by abstract and meandering ambient music. *Blonde* built on those ideas and imbued them with a little more form, taking a left-field, often minimalist approach to his breezy harmonies and ever-present narrative lyricism. His confidence was crucial to the risk of creating a big multimedia project for a sophomore album, but it also extended to his songwriting—his voice surer of itself (“Solo”), his willingness to excavate his weird impulses more prominent (“Good Guy,” “Pretty Sweet,” among others). Though *Blonde* packs 17 tracks into one quick hour, it’s a sprawling palette of ideas, a testament to the intelligence of flying one’s own artistic freak flag and trusting that audiences will meet you where you’re at. In this case, fans were enthusiastic enough for *Blonde* to rack up No. 1s on charts around the world.

Puberty is a game of emotional pinball: hormones that surge, feelings that ricochet between exhilarating highs and gut-churning lows. That’s the dizzying, intoxicating experience Mitski evokes on her aptly titled fourth album, a rush of rebel music that touches on riot grrrl, skeletal indie rock, dreamy pop, and buoyant punk. Unexpected hooks pierce through the singer/songwriter’s razor-edged narratives—a lilting chorus elevates the slinky, druggy “Crack Baby,” while her sweet singsong melodies wrestle with hollow guitar to amplify the tension on “Your Best American Girl.”

Ask Mitski Miyawaki about happiness and she'll warn you: “Happiness fucks you.” It's a lesson that's been writ large into the New Yorker's gritty, outsider-indie for years, but never so powerfully as on her newest album, 'Puberty 2'. “Happiness is up, sadness is down, but one's almost more destructive than the other,” she says. “When you realise you can't have one without the other, it's possible to spend periods of happiness just waiting for that other wave.” On 'Puberty 2', that tension is palpable: a both beautiful and brutal romantic hinterland, in which one of America’s new voices hits a brave new stride. The follow-up to 2014's 'Bury Me At Makeout Creek', named after a Simpsons quote and hailed by Pitchfork as “a complex 10-song story [containing] some of the most nuanced, complex and articulate music that's come from the indiesphere in a while,” 'Puberty 2' picks up where its predecessor left off. “It's kind of a two parter,” explains Mitski. “It's similar in sound, but a direct growth [from] that record.” Musically, there are subtle evolutions: electronic drum machines pulse throughout beneath Pixies-ish guitars, while saxophone lights up its opening track. “I had a certain confidence this time. I knew what I wanted, knew what I was doing and wasn't afraid to do things that some people may not like.” In terms of message though, the 25-year-old cuts the same defiant, feminist figure on 'Puberty 2' that won her acclaim last time around (her hero is MIA, for her politics as much as her music). Born in Japan, Mitski grew up surrounded by her father's Smithsonian folk recordings and mother's 1970s Japanese pop CDs in a family that moved frequently: she spent stints in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Malaysia, China and Turkey among other countries before coming to New York to study composition at SUNY Purchase. She reflects now on feeling “half Japanese, half American but not fully either” – a feeling she confronts on the clever 'Your Best American Girl' – a super-sized punk-rock hit she “hammed up the tropes” on to deconstruct and poke fun at that genre's surplus of white males. “I wanted to use those white-American-guy stereotypes as a Japanese girl who can't fit in, who can never be an American girl,” she explains. Elsewhere on the record there's 'Crack Baby', a song which doesn't pull on your heartstrings so much as swing from them like monkey bars, which Mitski wrote the skeleton of as a teenager. As you might have guessed from the album's title, that adolescent period is a time of her life she doesn't feel she's entirely left behind. “It came up as a joke and I became attached to it. 'Puberty 2'! It sounds like a blockbuster movie” – a nod to the horror-movie terror of adolescence. “I actually had a ridiculously long argument whether it should be the number 2, or a Roman numeral.” The album was put together with the help of long-term accomplice Patrick Hyland, with every instrument on record played between the two of them. “You know the Drake song 'No New Friends'? It's like that. The more I do this, the more I close-mindedly stick to the people I know,” she explains. “I think that focus made it my most mature record.” Sadness is awful and happiness is exhausting in the world of Mitski. The effect of 'Puberty 2', however, is a stark opposite: invigorating, inspiring and beautiful.

Bon Iver’s third LP is as bold as it is beautiful. Made during a five-year period when Justin Vernon contemplated ditching the project altogether, *22, A Million* perfects the sound alloyed on 2011’s *Bon Iver*: ethereal but direct, layered but stripped-back, as processed as EDM yet naked as a fallen branch. The songs here run together as though being uncovered in real time, with highlights—“29 #Strafford APTS,” “8 (circle)”—flashing in the haze.

'22, A Million' is part love letter, part final resting place of two decades of searching for self-understanding like a religion. And the inner-resolution of maybe never finding that understanding. The album’s 10 poly-fi recordings are a collection of sacred moments, love’s torment and salvation, contexts of intense memories, signs that you can pin meaning onto or disregard as coincidence. If Bon Iver, Bon Iver built a habitat rooted in physical spaces, then '22, A Million' is the letting go of that attachment to a place.

A confessional autobiography and meditation on being black in America, this album finds Solange searching for answers within a set of achingly lovely funk tunes. She finds intensity behind the patient grooves of “Weary,” expresses rage through restraint in “Mad,” and draws strength from the naked vulnerability of “Where Do We Go.” The spirit of Prince hovers throughout, especially over “Junie,” a glimmer of merriment in an exquisite portrait of sadness.

You have no right to be depressed You haven’t tried hard enough to like it There are two kinds of great lyrics. The first is the banger/anthem catch phrase: "Normal life is borin' / but superstardom is close to post-mortem." The second is more complex (and more rarely found): "Like a bird on a wire / Like a drunk in a midnight choir/I have tried in my way to be free" — with ideas, themes, and personae unfolding over the course of songs, contradicting each other, confronting the listeners' preconceptions, like Pete Townsend, Morrissey, or Kendrick Lamar. Will Toledo, the singer/songwriter/visionary of Car Seat Headrest, is adept at both, having developed them over the course of his eleven college-recorded Bandcamp albums and his retrospective collection last fall, Teens of Style. With Teens of Denial, his first real "studio" album with an actual band, Toledo moves from bedroom pop to something approaching classic-rock grandeur and huge (if detailed and personal) narrative ambitions, with nods to the Cars, Pavement, Jonathan Richman, Wire, and William Onyeabor. "I’m so sick of / (Fill in the blank)" or "It’s more than you bargained for / But it's a little less than what you paid for" are more than smart, edgy slogans. Over the course of Teens of Denial's 11 songs, Will narrates a journey with his mysterious companion/alter-ego Joe that addresses big themes (personal responsibility, existential despair, the nature of identity, the Bible, heaven) and small ones (Air Jordans, cops, whether to have one more beer, why he lost his backpack). By turns tender and caustic, empathetic and solipsistic, literary and vernacular, profound and profane, self-loathing and self-aggrandizing, he conjures a specifically 21st century mindset, a product of information overload, the loneliness it can foster, and the escape music can provide. “Fill in The Blank,” the mission statement of the album, kicks things off — it’s a fist-pumping anthem about feeling lousy in an ill-defined way, the fear of settling into a routine of futility, and not wanting to deal with it. Although it’s oddly joyful sounding, Toledo considers it the introduction to his angriest record yet. In that vein, “Vincent,” “Hippie Powers,” and “Connect The Dots” are about both fighting to hold your place in the crowd and to hold your drink, as well as DIY college house shows, and having no one to dance with, respectively. Initially similar, "Drunk Drivers/Killer Whales” veers off in surprising directions, each piece flush with huge, irony-free hooks. At the heart of the album sits the 11:32 "Ballad of the Costa Concordia," which has more musical ideas than most whole albums (and at that length, it uses them all). Horns, keyboards, and elegant instrumental interludes set off art-garage moments; vivid vocal harmonies follow punk frenzy. The selfish captain of the capsized cruise liner in the Mediterranean in 2013 becomes a metaphor for struggles of the individual in society, as experienced by one hungover young man on the verge of adulthood. Teens of Denial refracts Toledo's particular, personal story of one difficult year through cultural touchstones such as the biography of Frank Sinatra, the evolution of the Me Generation as seen in Mad Men and elsewhere, plus elements of eastern and western theology. The whole thing flaunts a kind of conceptual, lyrical, and musical ambition that has been missing from far too much 21st-century music. I won’t go down with this shit I will put my hands up and surrender there will be no more flags above my door I have lost, and always will be There are two kinds of great lyricists. The first kind is one one you find in books, canonized by time and a lifetime of expression. The second has it all in front of him. Meet Will Toledo. Or at least one version of him.

On their final album, Q-Tip, Phife Dawg, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and Jarobi rekindle a chemistry that endeared them to hip-hop fans worldwide. Filled with exploratory instrumental beds, creative samples, supple rhyming, and serious knock, it passes the headphone and car stereo test. “Kids…” is like a rap nerd’s fever dream, Andre 3000 and Q-Tip slaying bars. Phife—who passed away in March 2016—is the album’s scion, his roughneck style and biting humor shining through on “Black Spasmodic” and “Whateva Will Be.” “We the People” and “The Killing Season” (featuring Kanye West) show ATCQ’s ability to move minds as well as butts. *We got it from Here... Thank You 4 Your service* is not a wake or a comeback—it’s an extended visit with a long-missed friend, and a mic-dropping reminder of Tribe’s importance and influence.

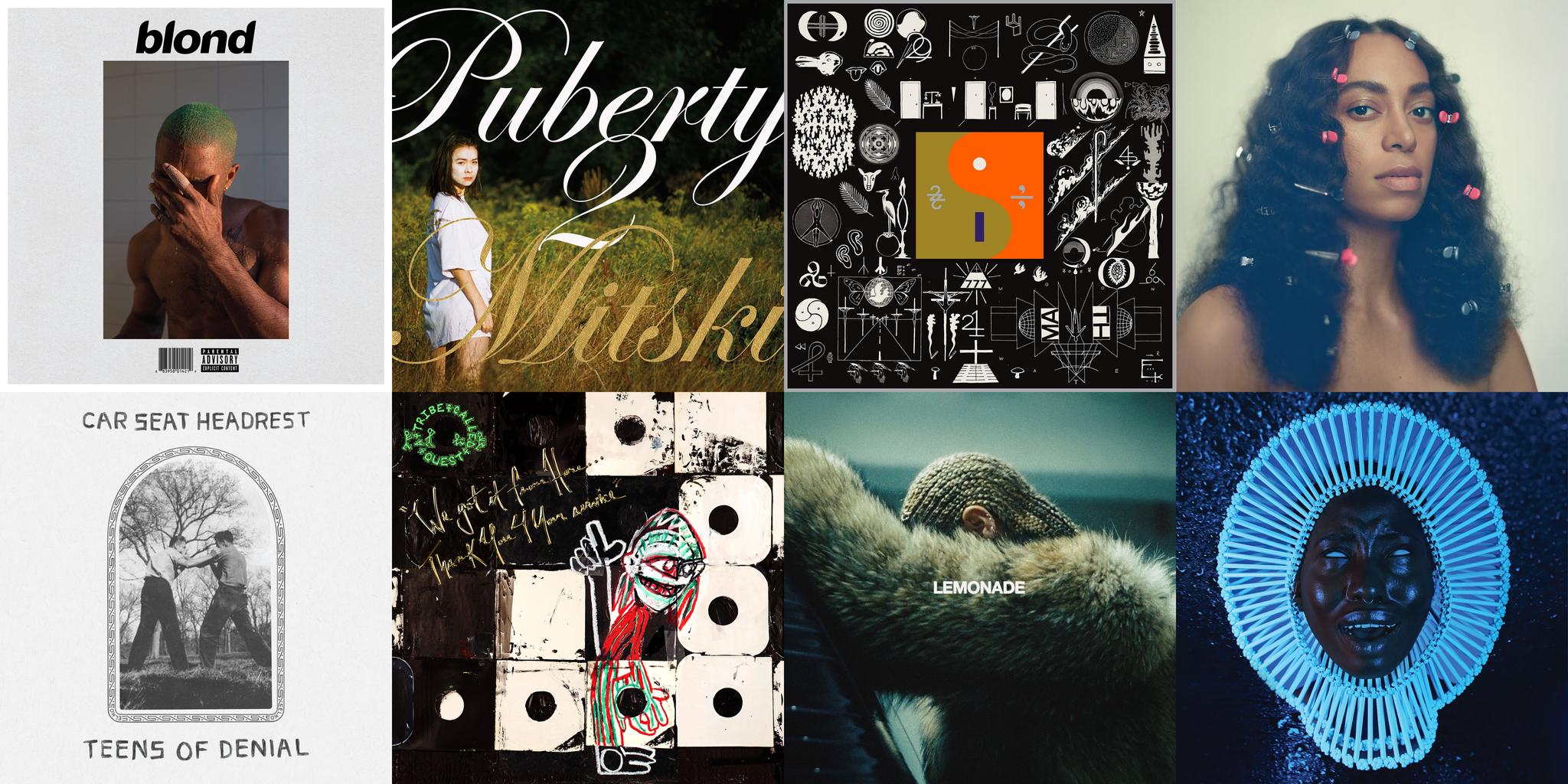

There’s one moment critical to understanding the emotional and cultural heft of *Lemonade*—Beyoncé’s genre-obliterating blockbuster sixth album—and it arrives at the end of “Freedom,” a storming empowerment anthem that samples a civil-rights-era prison song and features Kendrick Lamar. An elderly woman’s voice cuts in: \"I had my ups and downs, but I always find the inner strength to pull myself up,” she says. “I was served lemons, but I made lemonade.” The speech—made by her husband JAY-Z’s grandmother Hattie White on her 90th birthday in 2015—reportedly inspired the concept behind this radical project, which arrived with an accompanying film as well as words by Somali-British poet Warsan Shire. Both the album and its visual companion are deeply tied to Beyoncé’s identity and narrative (her womanhood, her blackness, her husband’s infidelity) and make for Beyoncé\'s most outwardly revealing work to date. The details, of course, are what make it so relatable, what make each song sting. Billed upon its release as a tribute to “every woman’s journey of self-knowledge and healing,” the project is furious, defiant, anguished, vulnerable, experimental, muscular, triumphant, humorous, and brave—a vivid personal statement from the most powerful woman in music, released without warning in a time of public scrutiny and private suffering. It is also astonishingly tough. Through tears, even Beyoncé has to summon her inner Beyoncé, roaring, “I’ma keep running ’cause a winner don’t quit on themselves.” This panoramic strength–lyrical, vocal, instrumental, and personal–nudged her public image from mere legend to something closer to real-life superhero. Every second of *Lemonade* deserves to be studied and celebrated (the self-punishment in “Sorry,” the politics in “Formation,” the creative enhancements from collaborators like James Blake, Robert Plant, and Karen O), but the song that aims the highest musically may be “Don’t Hurt Yourself”—a Zeppelin-sampling psych-rock duet with Jack White. “This is your final warning,” she says in a moment of unnerving calm. “If you try this shit again/You gon\' lose your wife.” In support, White offers a word to the wise: “Love God herself.”

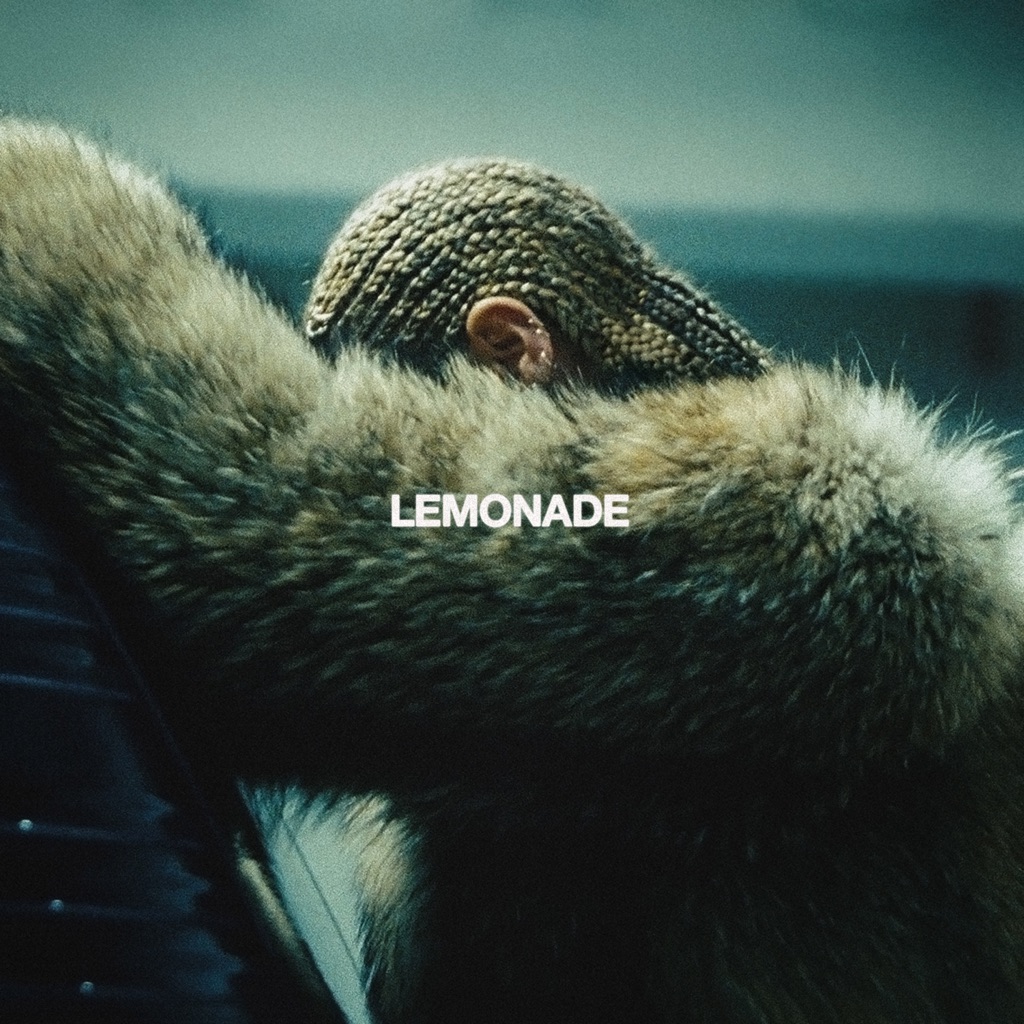

On the face of it, Donald Glover’s *“Awaken, My Love!”* is a museum-quality rip of early-’70s funk and soul: the faded vocals, the fuzzed-out guitars, the collective sense of chaos and exuberance. But it’s also more than that. Glover said he’d started with childhood memories of his parents playing Funkadelic and The Isley Brothers on the stereo: specific sounds and songs, but more importantly, a general feeling—one that Glover wasn’t quite old enough to grasp. Like a funhouse mirror, he stretches his influences into weird shapes: The freak-outs are exaggerated to the point of comedy (“Me and Your Mama”) and the ballads romantic to the point of creepy (“Terrified”). It makes for a tonal fluidity that also marks his work on the television show *Atlanta*, which he created. Coming from an artist known for taut wordplay and manically constructed similes, the broad strokes of *Awaken* are a shift: You’ll think eventually, but mood comes first. And in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests that followed the deaths of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and so many more, Glover’s choice to echo a period in Black music when artists took on an explicitly revolutionary cast is a canny complement to albums like Kendrick Lamar’s *To Pimp a Butterfly* and Solange Knowles’ *A Seat at the Table*, both of which explored Black identity with new urgency. The result is an experiment in time travel: Through sounds of the past, he captures the tensions of the present.

The new Weyes Blood record, Front Row Seat To Earth, is the folk music of the near future. Natalie Mering, the being behind Weyes Blood, embeds her sublime song in a harmonic gauze of arpeggiated piano, acoustic guitar, druggy horns, and outer space electronics. Propulsive, spare drums carry us across the album’s course. There is a faded California beauty to Front Row. A gentle honesty that recalls the finest folk music made on the West Coast of the ‘70s. The hue hangs in the sweet-spooky harmonies, the pulsing sway of the vibrato, and the ecstatic chord resolves. It is the joyful release of energy as the song delicately unfolds from intro to extrospection. But this beauty is scratched with shadow; with dark foreboding, alienation, and acceptance of change. Love and loss balance together in suspended alchemy, as the earthiness of the singer-songwriter tradition wears digital sounds like feathers in its hair. Mering, together with co-producer Chris Cohen and some special guests, contrasts live band intimacy with the post-modern electric sheen of A.M. radio atmospherics. The experimental flourishes sparkle amid the succinct, thoughtful arrangements. The closeness of this record - how personal, alone, and frank it feels - conceals its aspirations to the outside, to the "Earth" of its title. Weyes Blood harbors devastating weight while also universalizing the strange ways of identity and relationships. These are not typical love songs or protest songs -- they are painful, poignant riddles that celebrate the ambiguity of love and affirm the conflict of harmonious life within a disharmonic world.

After giving the world a decade of nonstop hits, the big question for Rihanna was “What’s next?” Well, she was going to wait a little longer than expected to reveal the answer. Four years separated *Unapologetic* and her eighth album. But she didn’t completely escape from the spotlight during the mini hiatus. Rather, she experimented in real time by dropping one-off singles like the acoustic folk “FourFiveSeconds” collaboration with Kanye West and Paul McCartney, the patriotic ballad “American Oxygen,” and the feisty “Bitch Better Have My Money.” The sonic direction she was going to land on for *ANTI* was still murky, but those songs were subtle hints nonetheless. When she officially unleashed *ANTI* to the world, it quickly became clear that this wasn’t the Rihanna we’d come to know from years past. In an unexpected twist, the singer tossed her own hit factory formula (which she polished to perfection since her 2005 debut) out the window. No, this was a freshly independent Rihanna who intentionally took time to dig deep. As the world was holding its breath awaiting the new album, she found a previously untapped part of her artistry. *ANTI* says it all in the title: The album is the complete antithesis of Pop Star Rihanna. From the abstract cover art (which features a poem written in braille) to newfound autonomy after leaving her longtime record label, Def Jam, to form her own, *ANTI* shattered all expectations of what a structured pop album should sound like—not only for her own standards, but also for fellow artists who wanted to demolish industry rules. And the risk worked in her favor: it became the singer’s second No. 1 LP. “I got to do things my own way, darling/Will you ever let me?/Will you ever respect me?” Rihanna mockingly asks on the opening track, “Consideration.” In response, the rest of the album dives headfirst into fearlessness where she doesn’t hesitate to get sensual, vulnerable, and just a little weird. *ANTI*’s overarching theme is centered on relationships. Echoing Janet Jackson’s *The Velvet Rope*, Rihanna details the intricacies of love from all stages. Lead single “Work” is yet another flirtatious reunion with frequent collaborator Drake as they tease each other atop a steamy dancehall bassline. She spits vitriolic acid on the Travis Scott-produced “Woo,” taunting an ex-flame who walked away from her: “I bet she could never make you cry/’Cause the scars on your heart are still mine.” What’s most notable throughout *ANTI* is Rihanna’s vocal expansion, from her whiskey-coated wails on the late-night voicemail that is “Higher” to breathing smoke on her rerecorded version of Tame Impala’s “New Person, Same Old Mistakes.” Yet the signature Rihanna DNA remained on the album. The singer proudly celebrated her Caribbean heritage on the aforementioned “Work,” presented women with yet another kiss-off anthem with “Needed Me,” and flaunted her erotic side on deluxe track “Sex With Me.” Ever the sonic explorer, she also continued to uncover new genres by going full ’50s doo-wop on “Love on the Brain” and channeling Prince for the velvety ’80s power-pop ballad “Kiss It Better.” *ANTI* is not only Rihanna’s brilliant magnum opus, but it’s also a sincere declaration of freedom as she embraces her fully realized womanhood.

Rapper/singer Anderson .Paak’s third album—and first since his star turn on Dr. Dre’s *Compton*—is a warm, wide-angle look at the sweep of his life. A former church drummer trained in gospel music, Paak is as expressive a singer as he is a rapper, sliding effortlessly between the reportorial grit of hip-hop (“Come Down”) and the emotional catharsis of soul and R&B (“The Season/Carry Me”), live-instrument grooves and studio production—a blend that puts him in league with other roots-conscious artists like Chance the Rapper and Kendrick Lamar.

When Maren Morris moved to Nashville, the now megastar had modest dreams of making a living as a writer for hire on Music Row. After finding her footing in town (as well as connecting with a top-notch cadre of cowriters), Morris wrote a song that would forever change her life: “My Church.” “I didn\'t have the interest to just be back onstage again for probably four or five years,” she tells Apple Music. “Then I wrote ‘My Church’ and it just kind of rekindled this flame in me of wanting to be the one on the microphone, because I just couldn\'t hear someone else singing that song.” The Grammy-winning single is only one of several hits on her fourth album *Hero*, which was also nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Country Album and led to Morris’ 2016 CMA Award win for New Artist of the Year. The breezy, carefree pop of “80s Mercedes” foreshadowed Morris’s genre agnosticism, while “Rich,” with its irreverent lyrics and earworm of a chorus, showed her versatility. Morris scored her first No. 1 hit at radio with the wistful ballad “I Could Use a Love Song,” an accomplishment that cut through the glut of men clogging country radio charts. “At the time, I don\'t think people remember how unheard of it was for a female with a ballad to go all the way to the top,” she tells Apple Music. Morris coproduced *Hero* alongside the late producer and songwriter busbee, who served as an integral collaborator for Morris until his death at 43 in 2019. “He’s just so embedded in every tom sound, every kick drum,” she tells Apple Music. “Every bass note is him playing. It’s still such a timeless record, to me, because of him.” *Hero* would soon catapult Morris to new heights, including featuring prominently on Zedd’s massive, paradigm-shifting pop hit “The Middle,” a move that would make her a household name just in time for the release of *Hero*’s follow-up, 2019’s *GIRL*.

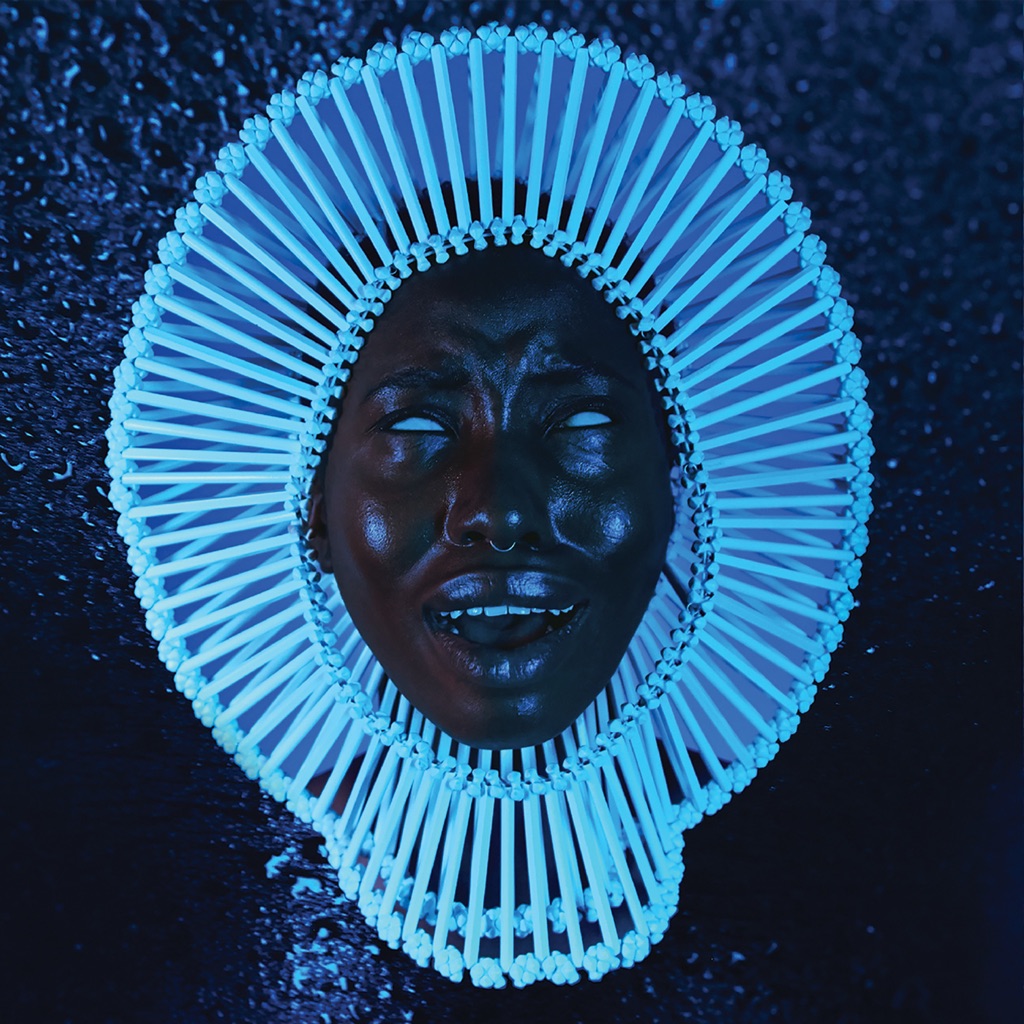

Radiohead’s ninth album is a haunting collection of shapeshifting rock, dystopian lullabies, and vast spectral beauty. Though you’ll hear echoes of their previous work—the remote churn of “Daydreaming,” the feverish ascent and spidery guitar of “Ful Stop,” Jonny Greenwood’s terrifying string flourishes—*A Moon Shaped Pool* is both familiar and wonderfully elusive, much like its unforgettable closer. A live favorite since the mid-‘90s, “True Love Waits” has been re-imagined in the studio as a weightless, piano-driven meditation that grows more exquisite as it gently floats away.

The songwriter transfigures personal tragedy into growling, elemental elegies. On his latest collaboration with the Bad Seeds, Nick Cave pulls us through the gorgeous, groaning terrors of “Anthrocene” and “Jesus Alone” only to deliver us, scarred but safe, to “I Need You” and “Skeleton Tree,” a pair of tender, mournful folk ballads.

KAYTRANADA\'s debut LP is a guest-packed club night of vintage house, hip-hop, and soul. The Montreal producer brings a rich old-school feel to all of these tracks, but it’s his vocalists that put them over the edge. AlunaGeorge drops a sizzling topline over a swervy beat on “TOGETHER,” Syd brings bedroom vibes to the bassline-driven house tune “YOU’RE THE ONE,” and Anderson .Paak is mysterious and laidback on the hazy soundscape “GLOWED UP.” And when Karriem Riggins and River Tiber assist on the boom-bap atmospheres of “BUS RIDE,\" they simply cement the deal.