Uncut's 75 Best Albums of 2021

The Uncut Review Of The Year: here's a rundown of the 50 best new albums we've listened to in 2021.

Published: December 21, 2021 10:42

Source

If 2019’s *“Let’s Rock”* allowed The Black Keys to go back to basics with their blues-smoked garage rock, then on *Delta Kream*, they honor the source. “Any chance we get to turn people on hill country blues, we want to do that, because it means that much to us,” singer-songwriter-guitarist Dan Auerbach tells Apple Music. “We love this music and definitely feel a close connection to it.” Recorded during a two-day session in Nashville with local musicians Kenny Brown and Eric Deaton, the Nashville-by-way-of-Akron, Ohio duo’s 10th LP features reworkings of North Mississippi hill country blues standards they’ve been listening to since they were in their teens. Their passion for the genre shows in their raw and effortless performances—whether they turn John Lee Hooker’s “Crawling Kingsnake” into a six-minute incendiary jam or give the full treatment to R.L. Burnside’s “Mellow Peaches” with a soulful guitar interplay that rises into an intense crescendo. But for the most part, Auerbach and drummer Patrick Carney are not interested in adding any bells and whistles, like on “Sad Days, Lonely Nights,” where they capture the live essence of Junior Kimbrough’s 1994 original. “Some of the best roots music are those spontaneous records,” Auerbach adds. “You can just feel this kind of nervous energy, but it was just fun.”

Damon Krukowski – Acoustic guitar, drums, vocals Naomi Yang – Bass, piano, keyboards, vocals Michio Kurihara – Electric guitar

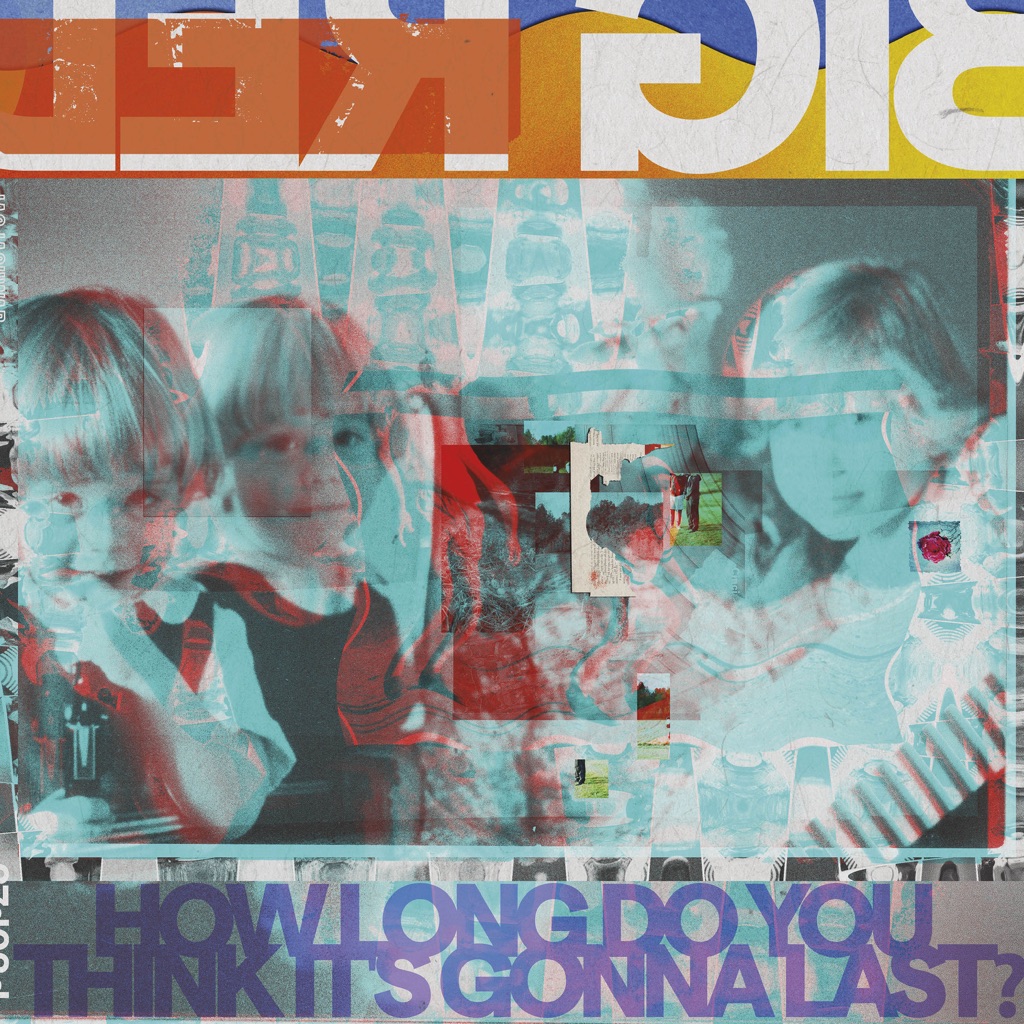

As a producer and multi-instrumentalist, Aaron Dessner has worked alongside a number of magnetic vocalists: Matt Berninger, Sharon Van Etten, Justin Vernon, and, most famously, Taylor Swift, on 2020’s *folklore* and *evermore*. But on his second LP as one-half of Big Red Machine (a sprawling collaboration with Vernon that began in the late 2000s with a song that became their namesake), he’s finally taken the mic himself. “I’m not naturally somebody who seeks the spotlight or wants to be lead singer,” he tells Apple Music. “I like the process of making and engineering and producing stuff, getting lost in the weeds. I’ve almost been a ventriloquist or something, trying to create emotional worlds for other people to inhabit. But I think I did realize that there’s another step, artistically, that I needed to take.” The decision to step into the foreground began, in part, with a nudge from both Swift and Vernon—after each heard a song Dessner had recently written about his twin brother (and fellow National guitarist), Bryce. “It just started happening,” he says of the transition. “I was lucky to be getting a strong push from these crazy-talented singers, who were all saying, ‘Don’t hide your voice.’” And though *How Long Do You Think It’s Gonna Last?* offers a stage to more lead vocalists than ever before (Anaïs Mitchell and Fleet Foxes’ Robin Pecknold among them), it’s an album that feels like Dessner’s—more personal, less opaque. Where Big Red Machine’s debut LP was, as Dessner says, a “wild” and “fairly cryptic” set of mostly electronic smudges and smears and sketches (all fronted by Vernon), its follow-up is traditional by comparison, its more song-oriented approach inspired by Dessner’s time playing with the Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir. “I wanted to be more intentional about it, but to create this feeling where there’s room for improvisation and the paint is always wet somehow,” he says. “I tried to make stuff that’s open and had this warmth, and always had this experimentation in it, too. I think we were successful on that.” Read on as Dessner takes us inside a number of the album’s key tracks. **“Latter Days” (feat. Anaïs Mitchell)** “I’d recorded the instrumental and when Justin heard it, the very first thing that he did is whistle. There was a microphone that picked him up. And we just kept it as a sort of improvised vocal melody that I wrote words to. I’ve always liked that about records, where there’s things that you don’t clean up, even though it’s slightly out of tune. If you listen closely, you’ll hear crickets and frogs on certain songs because the doors were open. That’s kind of how I think about Justin whistling.” **“Phoenix” (feat. Fleet Foxes & Anaïs Mitchell)** “I feel like Robin’s voice is timeless. I had written ‘Phoenix’ and Justin wrote the chorus melodies, and I just sent it to Robin as kind of a work in progress, imagining this multitude of voices could be a dialogue between different singers. He was really into it and moved and inspired. He wrote the song essentially as a dialogue between him and Justin, recalling the only conversation they ever had in person, which was backstage at a venue in Phoenix, Arizona, 10 years ago at a loading bay dock. That’s literally what it’s about, and when Anaïs Mitchell heard it, she rewrote Justin’s chorus lyrics, almost like a response to Robin. It’s very much the process of this record, the exchange of ideas.” **“Birch” (feat. Taylor Swift)** “It’s actually a beat that The National’s drummer, Bryan Devendorf, made in his basement. He will make these kind of loopy, trippy beats in his basement on a drum machine, and then send them to me as a Voice Memo. I wrote music to it and developed it and played all the parts to it and made it. It was during a time where I wasn’t doing that well, actually—maybe in fall 2019. I sent it to Justin, and good friends sometimes know when you’re going through something and maybe he felt that. He wrote the words and melody to it and as we recorded and developed it, we played it for Taylor at some point, towards the end of *folklore*. She really loved the song, and heard harmonies, and then kind of helped to lift further into some heavenly place.” **“Renegade” (feat. Taylor Swift)** “We wrote ‘Renegade’ after we finished *evermore*— I was really specifically writing music for Big Red Machine, and I think Taylor was, too. When she sent me ‘Renegade,’ it was literally another bolt of electricity. Thematically, it’s this idea of the way fear and anxiety and emotional baggage get in the way of loving, or being loved. I can just really relate to it in a very deep way. It did feel very connected to other songs and other characters in the record. But also, just the clarity of her songwriting and her sense of melody and rhythm and her diction: It’s just astonishing. She’s able to make a Voice Memo sound almost like it’s a finished record.” **“The Ghost of Cincinnati”** “It’s about the feeling of someone that’s empty, overextended to the point where they feel empty and hollow, like a ghost. They’re still alive, but they kind of feel like they’re running on fumes and searching for a remedy through fleeting memories and fleeting images of the past. It’s a sense of catharsis just by giving voice to a feeling that might be bleak. It kind of helps you get over it.” **“Easy to Sabotage” (feat. Naeem)** “It’s literally two bootlegs stitched together, two live recordings—one from Brooklyn at Pioneer Works and one from LA at the Hollywood Palladium. It was purely improvised, and then we took it and made a song out of it. It does relate more to the spontaneous, structured improvisation of the first Big Red Machine record, but I think it’s also a link between the past and the future of whatever this is.” **“Hutch” (feat. Sharon Van Etten, Lisa Hannigan & Shara Nova)** “I wrote a sketch inspired by my friend Scott Hutchison from Frightened Rabbit, who passed away. It’s this dark, kind of spiritual, kind of gothic piano piece. I’d produced the last Frightened Rabbit record, and it was just very shocking. He’s not the first friend I’ve lost that way, but it’s just really hard, obviously, and sad. You wonder how did it get so bad, or did I check in enough, or did I miss signs, or did I not take it seriously enough? That was the sentiment, but we wanted it to feel cathartic and have this heavenly lift to it. Lisa Hannigan and Sharon Van Etten and Shara Nova sing so beautifully on it. They added their parts and really lifted it like this angelic choir almost.” **“Brycie”** “I remember I wrote the music backstage in Washington, D.C. It was clear to me, in my head somehow, that it was about my brother. I think even the way that I was playing the guitar was how he and I play the guitar together, kind of—these interlocking, twin, mirrored guitar parts. That’s actually me and him playing together on the song, too. There are so many times in my life where he helped me get through a difficult time, where he refused to let me fall, and that’s what it’s about. It’s a love letter to him, thanking him for keeping me above the ground and hoping he’ll be there when we’re old. And when I wrote it, it was the first clue of what this record would become. It’s about looking at your childhood and searching for meaning in it—that time before you’ve lost innocence and before you’ve taken on the pressure and anxiety and uncertainty of adulthood. Just that feeling of ‘how long do you think it’s going to last?’”

Listening to Liz Harris’ music as Grouper, the word that comes to mind is “psychedelic.” Not in the cartoonish sense—if anything, the Astoria, Oregon-based artist feels like a monastic antidote to spectacle of almost any kind—but in the subtle way it distorts space and time. She can sound like a whisper whose words you can’t quite make out (“Pale Interior”) and like a primal call from a distant hillside (“Followed the ocean”). And even when you can understand what she’s saying, it doesn’t sound like she meant to be heard (“The way her hair falls”). The paradox is one of closeness and remove, of the intimacy of singer-songwriters and the neutral, almost oracular quality of great ambient music. That the tracks on *Shade*, her 12th LP, were culled from a 15-year period is fitting not just because it evokes Harris’ machine consistency (she found her creative truth and she’s sticking to it), but because of how the staticky, white-noise quality of her recordings makes you aware of the hum of the fridge and the hiss of the breeze: With Grouper, it’s always right now.

A few years removed from his Oscar-nominated work on 2017’s *Call Me by Your Name*, Sufjan Stevens turns to film for inspiration on this collaborative concept LP with LA singer-songwriter Angelo De Augustine. Working together in upstate New York, the two would watch a movie in the evening, then write a song in response the next morning, employing the sort of quiet arrangements and pristine melodies that mark their work as solo artists. It’s an ode to maintaining an open mind (or *shoshin*, the Zen Buddhist term whose English translation is the album’s title), Stevens and De Augustine as eager to engage with horror films and commercial blockbusters as they would artier fare—from *All About Eve* to *Hellraiser III*, *Bring It On Again* to *Point Break* and *Wings of Desire*. But whether they’re giving voice to *The Silence of the Lambs*’ Buffalo Bill (“Cimmerian Shade,” sung from the perspective of said serial killer) or exploring the power dynamics of Spike Lee’s *She’s Gotta Have It* (“It’s Your Own Body and Mind”), every song here sparkles and stands on its own. You don’t need to have seen any of the source material to fully appreciate it.

After decades of lending clutch support to everyone from D’Angelo to The Who, ace session bassist Pino Palladino makes his long-awaited debut on *Notes With Attachments*. The main attachment, enough to share cover billing, is Grammy-winning producer and multi-instrumentalist Blake Mills, who encountered Palladino and drummer Chris Dave (also of D’Angelo’s orbit) while working on John Legend’s 2016 album *Darkness and Light*. Collaborative seeds were sown, and the result is this highly inventive program of instrumentals, steeped in abstract hip-hop beats, leftfield sonics, clustery jazz harmony, and subtle compositional detailing. Palladino’s effortless bass steers but never dominates the set. Mills weighs in on everything from baritone guitar to berimbau, from tres to ngoni, keeping the timbres ever-changing. Chris Dave’s groove aesthetic is central enough to get an entire track named after him. But there’s also Senegalese percussion from Ben Aylon (on “Chris Dave” and “Man From Molise”), dollops of Andrew Bird’s violin on the Afrobeat-inspired “Ekuté,” and crafty organ, mellotron, and synth work from jazz great Larry Goldings on half the album as well. In terms of melody, texture, harmony, and counterpoint, the saxophonists are also essential: Sam Gendel cuts through on nearly every track, while guests Jacques Schwarz-Bart (on “Soundwalk”) and Marcus Strickland (on “Ekuté,” playing mainly bass clarinet) enhance the music’s dark and hazy lyricism.

Lucy Dacus’ favorite songs are “the ones that take 15 minutes to write,” she tells Apple Music. “I\'m easily convinced that the song is like a unit when it comes out in one burst. In many ways, I feel out of control, like it\'s not my decision what I write.” On her third LP, the Philadelphia-based singer-songwriter surrenders to autobiography with a set of spare and intimate indie rock that combines her memory of growing up in Richmond, Virginia, with details she pulled from journals she’s kept since she was 7, much of it shaped by her religious upbringing. It’s as much about what we remember as how and why we remember it. “The record was me looking at my past, but now when I hear them it\'s almost like the songs are a part of the past, like a memory about memory,” she says. “This must be what I was ready to do, and I have to trust that. There\'s probably stuff that has happened to me that I\'m still not ready to look at and I just have to wait for the day that I am.” Here, she tells us the story behind every song on the album. **“Hot & Heavy”** “My first big tour in 2016—after my first record came out—was two and a half months, and at the very end of it, I broke up with my partner at the time. I came back to Richmond after being gone for the longest I\'d ever been away and everything felt different: people’s perception of me; my friend group; my living situation. I was, for the first time, not comfortable in Richmond, and I felt really sad about that because I had planned on being here my whole life. This song is about returning to where you grew up—or where you spent any of your past—and being hit with an onslaught of memories. I think of my past self as a separate person, so the song is me speaking to me. It’s realizing that at one point in my life, everything was ahead of me and my life could\'ve ended up however. It still can, but it\'s like now I know the secret.” **“Christine”** “It starts with a scene that really happened. Me and my friend were sitting in the backseat and she\'s asleep on my shoulder. We’re coming home from a sermon that was about how humans are evil and children especially need to be guided or else they\'ll fall into the hands of the devil. She was dating this guy who at the time was just not treating her right, and I played her the song. I was like, ‘I just want you to hear this once. I\'ll put it away, but you should know that I would not support you if you get married. I don\'t think that this is the best you could do.’ She took it to heart, but she didn\'t actually break up with the guy. They\'re still together and he\'s changed and they\'ve changed and I don\'t feel that way anymore. I feel like they\'re in a better place, but at the time it felt very urgent to me that she get out of that situation.” **“First Time”** “I was on a kind of fast-paced walk and I started singing to myself, which is how I write most of my songs. I had all this energy and I started jogging for no reason, which, if you know me, is super not me—I would not electively jog. I started writing about that feeling when you\'re in love for the first time and all you think about is the one person and how you find access to yourself through them. I paused for a second because I was like, ‘Do I really want to talk about early sexual experiences? No, just do it. If you don\'t like it, don\'t share it.’ It’s about discovery: your body and your emotional capacity and how you\'re never going to feel it that way you did the first time again. At the time, I was very worried that I\'d never feel that way again. The truth was, I haven’t—but I have felt other wonderful things.” **“VBS”** “I don\'t want my identity to be that I used to believe in God because I didn\'t even choose that, but it\'s inextricable to who I am and my upbringing. I like that in the song, the setting is \[Vacation Bible School\], but the core of the song is about a relationship. My first boyfriend, who I met at VBS, used to snort nutmeg. He was a Slayer fan and it was contentious in our relationship because he loved Slayer even more than God and I got into Slayer thinking, ‘Oh, maybe he\'ll get into God.’ He was one of the kids that went to church but wasn\'t super into it, whereas I was defining my whole life by it. But I’ve got to thank him for introducing me to Slayer and The Cure, which had the biggest impact on me.” **“Cartwheel”** “I was taking a walk with \[producer\] Collin \[Pastore\] and as we passed by his school, I remembered all of the times that I was forced to play dodgeball, and how the heat in Richmond would get so bad that it would melt your shoes. That memory ended up turning into this song, about how all my girlfriends at that age were starting to get into boys before I wanted to and I felt so panicked. Why are we sneaking boys into the sleepover? They\'re not even talking. We were having fun and now no one is playing with me anymore. When my best friend told me when she had sex for the first time, I felt so betrayed. I blamed it on God, but really it was personal, because I knew that our friendship was over as I knew it, and it was.” **“Thumbs”** “I was in the car on the way to dinner in Nashville. We were going to a Thai restaurant, meeting up with some friends, and I just had my notepad out. Didn\'t notice it was happening, and then wrote the last line, ‘You don\'t owe him shit,’ and then I wrote it down a second time because I needed to hear it for myself. My birth father is somebody that doesn\'t really understand boundaries, and I guess I didn\'t know that I believed that, that I didn\'t owe him anything, until I said it out loud. When we got to the restaurant, I felt like I was going to throw up, and so they all went into the restaurant, got a table, and I just sat there and cried. Then I gathered myself and had some pad thai.” **“Going Going Gone”** “I stayed up until like 1:00 am writing this cute little song on the little travel guitar that I bring on tour. I thought for sure I\'d never put it on a record because it\'s so campfire-ish. I never thought that it would fit tonally on anything, but I like the meaning of it. It\'s about the cycle of boys and girls, then men and women, and then fathers and daughters, and how fathers are protective of their daughters potentially because as young men they either witnessed or perpetrated abuse. Or just that men who would casually assault women know that their daughters are in danger of that, and that\'s maybe why they\'re so protective. I like it right after ‘Thumbs’ because it\'s like a reprieve after the heaviest point on the record.” **“Partner in Crime”** “I tried to sing a regular take and I was just sounding bad that day. We did Auto-Tune temporarily, but then we loved it so much we just kept it. I liked that it was a choice. The meaning of the song is about this relationship I had when I was a teenager with somebody who was older than me, and how I tried to act really adult in order to relate or get that person\'s respect. So Auto-Tune fits because it falsifies your voice in order to be technically more perfect or maybe more attractive.” **“Brando”** “I really started to know about older movies in high school, when I met this one friend who the song is about. I feel like he was attracted to anything that could give him superiority—he was a self-proclaimed anarchist punk, which just meant that he knew more and knew better than everyone. He used to tell me that he knew me better than everyone else, but really that could not have been true because I hardly ever talked about myself and he was never satisfied with who I was.” **“Please Stay”** “I wrote it in September of 2019, after we recorded most of the record. I had been circling around this role that I have played throughout my life, where I am trying to convince somebody that I love very much that their life is worth living. The song is about me just feeling helpless but trying to do anything I can to offer any sort of way in to life, instead of a way out. One day at a time is the right pace to aim for.” **“Triple Dog Dare”** “In high school I was friends with this girl and we would spend all our time together. Neither of us were out, but I think that her mom saw that there was romantic potential, even though I wouldn\'t come out to myself for many years later. The first verses of the song are true: Her mom kept us apart, our friendship didn\'t last. But the ending of the song is this fictitious alternative where the characters actually do prioritize each other and get out from under the thumbs of their parents and they steal a boat and they run away and it\'s sort of left to anyone\'s interpretation whether or not they succeed at that or if they die at sea. There’s no such thing as nonfiction. I felt empowered by finding out that I could just do that, like no one was making me tell the truth in that scenario. Songwriting doesn\'t have to be reporting.”

It’s perhaps fitting that Dave’s second album opens with the familiar flicker and countdown of a movie projector sequence. Its title was handed to him by iconic film composer Hans Zimmer in a FaceTime chat, and *We’re All Alone in This Together* sets evocative scenes that laud the power of being able to determine your future. On his 2019 debut *PSYCHODRAMA*, the Streatham rapper revealed himself to be an exhilarating, genre-defying artist attempting to extricate himself from the hazy whirlwind of his own mind. Two years on, Dave’s work feels more ambitious, more widescreen, and doubles down on his superpower—that ability to absorb perspectives around him within his otherworldly rhymes and ideas. He’s addressing deeply personal themes from a sharp, shifting lens. “My life’s full of plot holes,” he declares on “We’re All Alone.” “And I’m filling them up.” As it has been since his emergence, Dave is skilled, mature, and honest enough to both lay bare and uplift the Black British experience. “In the Fire” recruits four sons of immigrant UK families—Fredo, Meekz, Giggs, and Ghetts (all uncredited, all lending incendiary bars)—and closes on a spirited Dave verse touching on early threats of deportation and homelessness. With these moments in the can, the earned boasts of rare kicks and timepieces alongside Stormzy for “Clash” are justified moments of relief from past struggles. And these loose threads tie together on “Three Rivers”—a somber, piano-led track that salutes the contributions of Britain’s Windrush generation and survivors of war-torn scenarios, from the Middle East to Africa. In exploring migration—and the questions it asks of us—Dave is inevitably led to his Nigerian heritage. Lagos newcomer Boj puts down a spirited, instructional hook in Yoruba for “Lazarus,” while Wizkid steps in to form a smooth double act on “System.” “Twenty to One,” meanwhile, is “Toosie Slide” catchy and precedes “Heart Attack”—arguably the showstopper at 10 minutes and loaded with blistering home truths on youth violence. On *PSYCHODRAMA* Dave showed how music was his private sanctuary from a life studded by tragedy. *We’re All Alone in This Together* suggests that relationship might have changed. Dave is now using his platform to share past pains and unique stories of migration in times of growing isolation. This music keeps him—and us—connected.