The Line of Best Fit's 50 Essential Albums of 2016

Here are the fifty records that made 2016 a beautiful, sad, profound and memorable year for us.

Published: December 14, 2016 00:00

Source

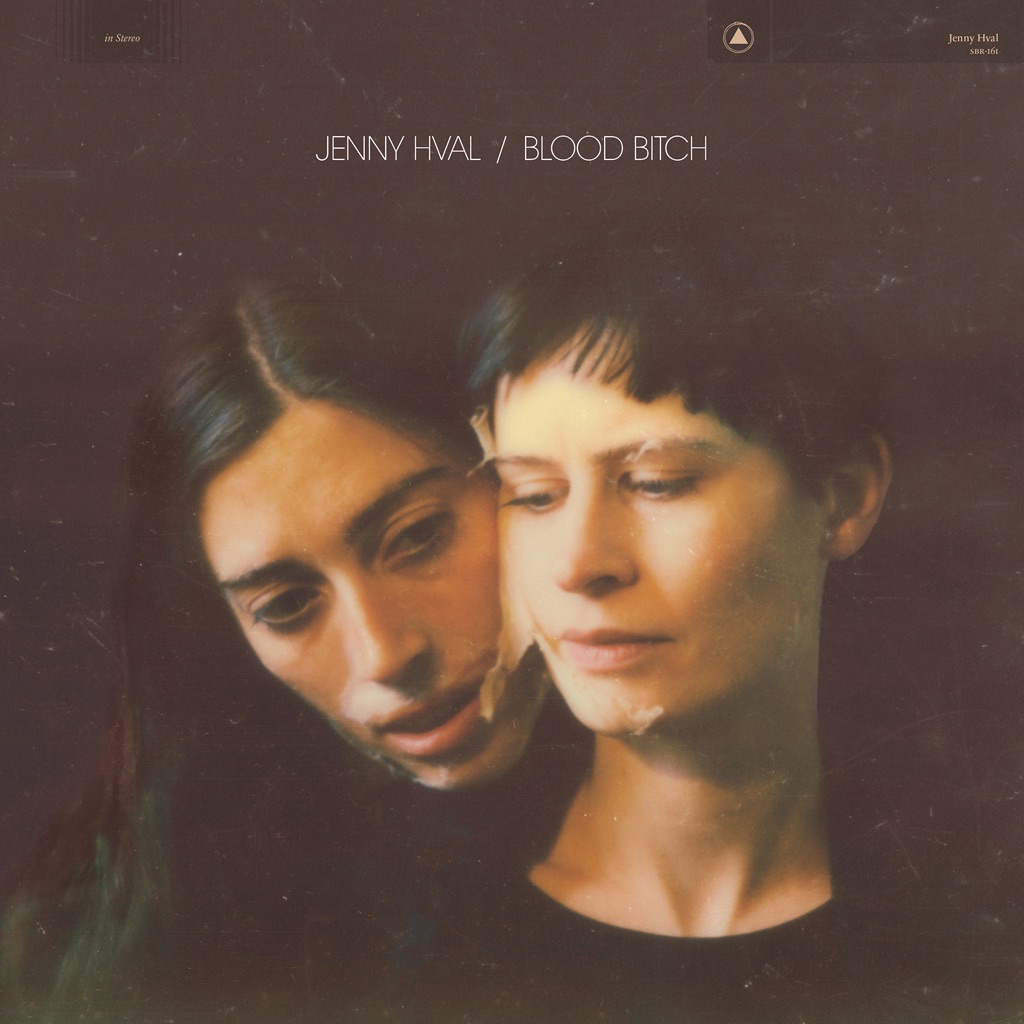

The avant garde Norwegian throws open a ghostly sonic sketchbook on this complex sixth album. Taking vampirism, gore, and femininity as her stated themes, Hval uses everything from percussive panting (the compellingly sinister “In The Red”) to distant, discordant horns (“Untamed Region”) to conjure challenging, dark dreamscapes. Thankfully, she never forgets the tunes. “The Great Undressing” is a propulsive art-pop jewel, and “Secret Touch” pits Hval’s brittle falsetto against hissing, addictive trip hop.

Jenny Hval’s conceptual takes on collective and individual gender identities and sociopolitical constructs landed Apocalypse, girl on dozens of year end lists and compelled writers everywhere to grapple with the age-old, yet previously unspoken, question: What is Soft Dick Rock? After touring for a year and earning her second Nordic Prize nomination, as any perfectionist would, Hval immediately went back into the studio to continue her work with acumen noise producer Lasse Marhaug, with whom she co-produces here on Blood Bitch. Her new effort is in many respects a complete 180° from her last in subject matter, execution and production. It is her most focused, but the lens is filtered through a gaze which the viewer least expects.

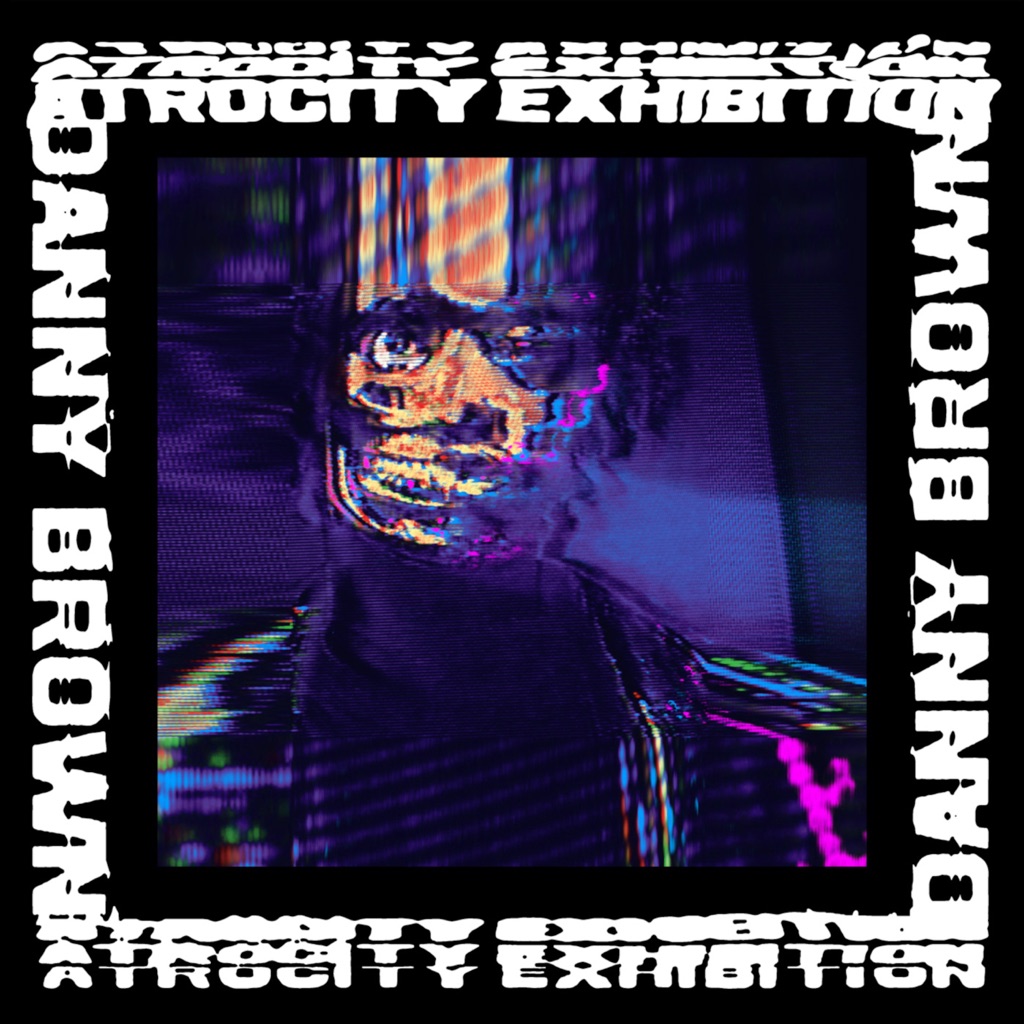

More trauma and travails with the magnetic Detroit MC. Like *XXX* and *Old* before it, *Atrocity Exhibition* plays like a nightmare with punchlines, the diary of a hedonist who loves the night as much as he hates the morning after. “Upcoming heavy traffic/say ya need to slow down, ’cause you feel yourself crashing,” Brown raps on “Ain’t it Funny,” a feverish highlight. “Staring the devil in the face but ya can’t stop laughing.”

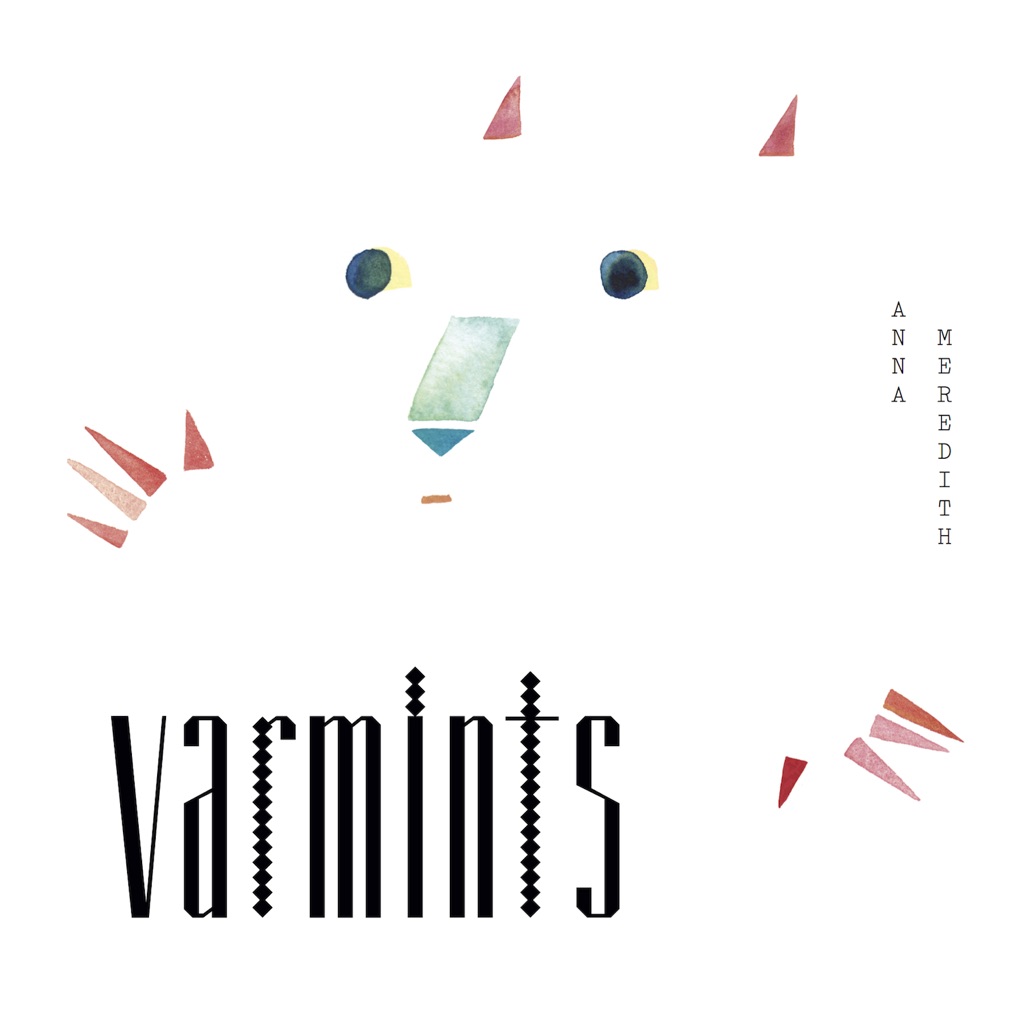

Anna Meredith may have composed for the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, but she’s also written a piece for an MRI scanner. Echoing that breadth of approaches, her debut album blends classical leanings (clarinet, tuba, cello) with bubbling electronics and Dirty Projectors-esque avant-pop. The Scottish-born, London-based composer stokes pinging, bass-buffeted melodies on opener “Nautilus”, while “Taken” moves to distorted guitar and a quasi-rock chorus. Whether turning to epic synth odysseys (“The Vapours”) or sugary electro-pop (“Something Helpful”), *Varmints* accumulates more giddy ideas with every passing minute.

"one of the most innovative minds in modern British music" Pitchfork (Best New Music) "hearing a leading young classical composer, regardless of gender, leap ahead of the pack to make electronic pop that's both accessible and out there is something very special" WIRE "jaw-dropping debut" The Line of Best Fit The follow-up to 2012's Black Prince Fury EP and 2013's Jet Black Raider EP, Anna Meredith's debut full length Varmints. For all its atmospheric, Varmints is held together by Meredith's expert understanding of dynamics. "Pacing is a physical thing," she explains. "I can feel when stuff has to happen in a track. I knew I wanted Varmints to end privately but start confidently, have moments of privacy and moments of power and build'. All limited edition LPs come with a download code.

Puberty is a game of emotional pinball: hormones that surge, feelings that ricochet between exhilarating highs and gut-churning lows. That’s the dizzying, intoxicating experience Mitski evokes on her aptly titled fourth album, a rush of rebel music that touches on riot grrrl, skeletal indie rock, dreamy pop, and buoyant punk. Unexpected hooks pierce through the singer/songwriter’s razor-edged narratives—a lilting chorus elevates the slinky, druggy “Crack Baby,” while her sweet singsong melodies wrestle with hollow guitar to amplify the tension on “Your Best American Girl.”

Ask Mitski Miyawaki about happiness and she'll warn you: “Happiness fucks you.” It's a lesson that's been writ large into the New Yorker's gritty, outsider-indie for years, but never so powerfully as on her newest album, 'Puberty 2'. “Happiness is up, sadness is down, but one's almost more destructive than the other,” she says. “When you realise you can't have one without the other, it's possible to spend periods of happiness just waiting for that other wave.” On 'Puberty 2', that tension is palpable: a both beautiful and brutal romantic hinterland, in which one of America’s new voices hits a brave new stride. The follow-up to 2014's 'Bury Me At Makeout Creek', named after a Simpsons quote and hailed by Pitchfork as “a complex 10-song story [containing] some of the most nuanced, complex and articulate music that's come from the indiesphere in a while,” 'Puberty 2' picks up where its predecessor left off. “It's kind of a two parter,” explains Mitski. “It's similar in sound, but a direct growth [from] that record.” Musically, there are subtle evolutions: electronic drum machines pulse throughout beneath Pixies-ish guitars, while saxophone lights up its opening track. “I had a certain confidence this time. I knew what I wanted, knew what I was doing and wasn't afraid to do things that some people may not like.” In terms of message though, the 25-year-old cuts the same defiant, feminist figure on 'Puberty 2' that won her acclaim last time around (her hero is MIA, for her politics as much as her music). Born in Japan, Mitski grew up surrounded by her father's Smithsonian folk recordings and mother's 1970s Japanese pop CDs in a family that moved frequently: she spent stints in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Malaysia, China and Turkey among other countries before coming to New York to study composition at SUNY Purchase. She reflects now on feeling “half Japanese, half American but not fully either” – a feeling she confronts on the clever 'Your Best American Girl' – a super-sized punk-rock hit she “hammed up the tropes” on to deconstruct and poke fun at that genre's surplus of white males. “I wanted to use those white-American-guy stereotypes as a Japanese girl who can't fit in, who can never be an American girl,” she explains. Elsewhere on the record there's 'Crack Baby', a song which doesn't pull on your heartstrings so much as swing from them like monkey bars, which Mitski wrote the skeleton of as a teenager. As you might have guessed from the album's title, that adolescent period is a time of her life she doesn't feel she's entirely left behind. “It came up as a joke and I became attached to it. 'Puberty 2'! It sounds like a blockbuster movie” – a nod to the horror-movie terror of adolescence. “I actually had a ridiculously long argument whether it should be the number 2, or a Roman numeral.” The album was put together with the help of long-term accomplice Patrick Hyland, with every instrument on record played between the two of them. “You know the Drake song 'No New Friends'? It's like that. The more I do this, the more I close-mindedly stick to the people I know,” she explains. “I think that focus made it my most mature record.” Sadness is awful and happiness is exhausting in the world of Mitski. The effect of 'Puberty 2', however, is a stark opposite: invigorating, inspiring and beautiful.

Bon Iver’s third LP is as bold as it is beautiful. Made during a five-year period when Justin Vernon contemplated ditching the project altogether, *22, A Million* perfects the sound alloyed on 2011’s *Bon Iver*: ethereal but direct, layered but stripped-back, as processed as EDM yet naked as a fallen branch. The songs here run together as though being uncovered in real time, with highlights—“29 #Strafford APTS,” “8 (circle)”—flashing in the haze.

'22, A Million' is part love letter, part final resting place of two decades of searching for self-understanding like a religion. And the inner-resolution of maybe never finding that understanding. The album’s 10 poly-fi recordings are a collection of sacred moments, love’s torment and salvation, contexts of intense memories, signs that you can pin meaning onto or disregard as coincidence. If Bon Iver, Bon Iver built a habitat rooted in physical spaces, then '22, A Million' is the letting go of that attachment to a place.

On this, his first masterpiece, Chance evolves—from Rapper to pop visionary. Influenced by gospel music, *Coloring Book* finds the Chicago native moved by the Holy Spirit and the current state of his hometown. “I speak to God in public,” he says on “Blessings,” its radiant closer. “He think the new sh\*t jam / I think we mutual fans.”

Pop that’s both understated and immediate, from a rising singer/songwriter. On her long-awaited debut, Shura weaves together elegant, intricately patterned electro-pop that channels late-‘80s Madonna (“What’s It Gonna Be?”), Janet Jackson (“Indecision”), and more. Though it has the grand sweep and melodic goods of a major breakthrough, *Nothing Real* also bears the subtle flourishes (and song titles) of a reticent, deeply introspective mind.

On their final album, Q-Tip, Phife Dawg, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and Jarobi rekindle a chemistry that endeared them to hip-hop fans worldwide. Filled with exploratory instrumental beds, creative samples, supple rhyming, and serious knock, it passes the headphone and car stereo test. “Kids…” is like a rap nerd’s fever dream, Andre 3000 and Q-Tip slaying bars. Phife—who passed away in March 2016—is the album’s scion, his roughneck style and biting humor shining through on “Black Spasmodic” and “Whateva Will Be.” “We the People” and “The Killing Season” (featuring Kanye West) show ATCQ’s ability to move minds as well as butts. *We got it from Here... Thank You 4 Your service* is not a wake or a comeback—it’s an extended visit with a long-missed friend, and a mic-dropping reminder of Tribe’s importance and influence.

ANOHNI has collaborated with Oneohtrix Point Never and Hudson Mohawke on the artist's latest work, HOPELESSNESS. Late last year, ANOHNI, the lead singer from Antony and the Johnsons, released “4 DEGREES", a bombastic dance track celebrating global boiling and collapsing biodiversity. Rather than taking refuge in good intentions, ANOHNI gives voice to the attitude sublimated within her behavior as she continues to consume in a fossil fuel-based economy. ANOHNI released “4 DEGREES,” the first single from her upcoming album HOPELESSNESS, to support the Paris climate conference this past December. The song emerged earlier last year in live performances. As discussed by ANOHNI: "I have grown tired of grieving for humanity, and I also thought I was not being entirely honest by pretending that I am not a part of the problem," she said. “’4 DEGREES' is kind of a brutal attempt to hold myself accountable, not just valorize my intentions, but also reflect on the true impact of my behaviors.” The album, HOPELESSNESS, to be released world wide on May 6th 2016, is a dance record with soulful vocals and lyrics addressing surveillance, drone warfare, and ecocide. A radical departure from the singer’s symphonic collaborations, the album seeks to disrupt assumptions about popular music through the collision of electronic sound and highly politicized lyrics. ANOHNI will present select concerts in Europe, Australia and the US in support of HOPELESSNESS this Summer.

KAYTRANADA\'s debut LP is a guest-packed club night of vintage house, hip-hop, and soul. The Montreal producer brings a rich old-school feel to all of these tracks, but it’s his vocalists that put them over the edge. AlunaGeorge drops a sizzling topline over a swervy beat on “TOGETHER,” Syd brings bedroom vibes to the bassline-driven house tune “YOU’RE THE ONE,” and Anderson .Paak is mysterious and laidback on the hazy soundscape “GLOWED UP.” And when Karriem Riggins and River Tiber assist on the boom-bap atmospheres of “BUS RIDE,\" they simply cement the deal.

After the lonesome folk and skeletal roadhouse soul of her debut album, 2012’s *Half Way Home*, Angel Olsen turned up the intensity on *Burn Your Fire for No Witness*, and she does it again on *MY WOMAN*. The title’s in all caps for a reason: The St. Louis, Missouri, native’s third album is bigger in both the acrobatic feats of her always-agile voice and the widescreen, hi-fi sound that Olsen and co-producer Justin Raisen bring to the table. With the very first song, “Intern,” it’s clear that Olsen has taken us somewhere new. A slow dance in a dive bar at last call, it might be familiar turf were it not for the synthesizers that cast an eerie glow across the song’s red-velvet backdrop. “Never Be Mine” harnesses the anguish of ’60s girl groups in jangling guitar and crisp backbeats; “Shut Up Kiss Me” couches desire in terms so heated the mic practically melts beneath Olsen’s yelp. Mindful of its ancestry but never expressly retro, the album is a triumph of rock ’n’ roll pathos, an exquisite dissertation on the poetry of twang and tremolo. And even if “There is nothing new/Under the sun,” as Olsen sings on the fateful “Heart Shaped Face,” she is forever finding ways to file down everyday truths to a finer point, drawing blood with every new prick. As she sighs over watery piano and fathomless reverb on the heartbreaking closer, “Pops,” “It hurts to start dreaming/Dreaming again.” But that pain is precisely what makes *MY WOMAN* so unforgettable, and so true.

Anyone reckless enough to have typecast Angel Olsen according to 2013’s ‘Burn Your Fire For No Witness’ is in for a sizable surprise with her third album, ‘MY WOMAN’. The crunchier, blown-out production of the former is gone, but that fire is now burning wilder. Her disarming, timeless voice is even more front-and-centre than before, and the overall production is lighter. Yet the strange, raw power and slowly unspooling incantations of her previous efforts remain, so anyone who might attempt to pigeonhole Olsen as either an elliptical outsider or a pop personality is going to be wrong whichever way they choose - Olsen continues to reign over the land between the two with a haunting obliqueness and sophisticated grace. Given its title, and track names like ‘Sister’ and ‘Woman’, it would be easy to read a gender-specific message into ‘MY WOMAN’, but Olsen has never played her lyrical content straight. She explains: “I’m definitely using scenes that I’ve replayed in my head, in the same way that I might write a script and manipulate a memory to get it to fit. But I think it’s important that people can interpret things the way that they want to.” That said, Olsen concedes that if she could locate any theme, whether in the funny, synth-laden ‘Intern’ or the sadder songs which are collected on the record’s latter half, “then it’s maybe the complicated mess of being a woman and wanting to stand up for yourself, while also knowing that there are things you are expected to ignore, almost, for the sake of loving a man. I’m not trying to make a feminist statement with every single record, just because I’m a woman. But I do feel like there are some themes that relate to that, without it being the complete picture.” Over her two previous albums, she’s given us reverb-shrouded poetic swoons, shadowy folk, grunge-pop band workouts and haunting, finger-picked epics. ‘MY WOMAN’ is an exhilarating complement to her past work, and one for which Olsen recalibrated her writing/recording approach and methods to enter a new music-making phase. She wrote some songs on the piano she’d bought at the end of the previous album tour, but she later switched it out for synth and/or Mellotron on a few of them, such as the aforementioned ‘Intern’. ‘MY WOMAN’ is lovingly put together as a proper A-side and a B-side, featuring the punchier, more pop/rock-oriented songs up front, and the longer, more reflective tracks towards the end. The rollicking ‘Shut Up Kiss Me’, for example, appears early on - its nervy grunge quality belying a subtle desperation, as befits any song about the exhaustion point of an impassioned argument. Another crowning moment comes in the form of the melancholic and Velvets-esque ‘Heart-shaped Face’, while the compelling ‘Sister’ and ‘Woman’ are the only songs not sung live. They also both run well over the seven-minute mark: the first being a triumph of reverb-splashed, ’70s country rock, cast along Fleetwood Mac lines with a Neil Young caged-tiger guitar solo to cap it off. The latter is a wonderful essay in vintage electronic pop and languid, psychedelic soul. Because her new songs demanded a plurality of voices, Olsen sings in a much broader range of styles on the album, and she brought in guest guitarist Seth Kauffman to augment her regular band of bass player Emily Elhaj, drummer Joshua Jaeger and guitarist Stewart Bronaugh. As for a producer, Olsen took to Justin Raisen, who’s known for his work with Charli XCX, Sky Ferreira and Santigold, as well as opting to record live to tape at LA’s historic Vox Studios. As the record evolves, you get the sense that the “My Woman” of the title is Olsen herself - absolutely in command, but also willing to bend with the influence of collaborators and circumstances. If ever there was any pressure in the recording process, it’s totally undetectable in the result. An intuitively smart, warmly communicative and fearlessly generous record, ‘MY WOMAN’ speaks to everyone. That it might confound expectation is just another of its strengths.

When the four members of Preoccupations wrote and recorded their new record, they were in a state of near total instability. Years-long relationships ended; they left homes behind. Frontman Matt Flegel, guitarist Danny Christiansen, multi-instrumentalist Scott Munro and drummer Mike Wallace all moved to different cities. They resolved to change their band name, but hadn’t settled on a new one. And their road-tested, honed approach to songwriting was basically thrown out the window. This time, they walked into the studio with the gas gauge near empty, buoyed by one another while the rest of their lives were virtually unrecognizable and rootless. There was no central theme or idea to guide the band’s collective cliff jump. As a result, ‘Preoccupations’ bears the visceral, personal sound of holding onto some steadiness in the midst of changing everything. Flegel is quick to point out how little mystery is in the titles of these songs: Anxiety, Monotony, Degraded, Stimulation, Fever. “Monotony is a dead end job; Anxiety is changing as a band,” he says. “Memory is watching someone lose their mind; Fever is comforting someone. It’s all drawing from very specific things.” These things — bigger ones like breakups, smaller ones like simply trying to calm someone down — are ultimately the things that explode our brains, that keep us up at night. And so where their previous album ‘Viet Cong’ was built in some ways on the abstract cycles of creation and destruction, ‘Preoccupations’ explores how that sometimes-suffocating, sometimes-revelatory trap affects our lives. “We discarded a lot, reworking songs pretty ruthlessly,” Munro explains. “We ripped songs down to the studs, taking one piece we liked and building something new around it. It was pretty cannibalistic, I guess. Existing songs were killed and used to make new ones.” Sonically, it’s still blistering. But it’s a different kind of blister, less the the scorched earth of the band’s previous LP, more like a blood blister on a fingertip: something immediate and physical that you push and stare at. It’s yours. Opener “Anxiety” articulates that tension: clattering sounds drift into focus, bouncing and echoing off one another until one bone-shattering moment when the full band strikes at once, moving from something untouchable to get to something deeply felt. “Monotony” moves at a narcoleptic pace by Preoccupations’ standards, but snaps to attention to make its point, that “this repetition’s killing you // it’s killing everyone.” “Stimulation” opens with a snarl and hurls itself forward at what feels like a million bpm, pausing for one mortal moment of relief before barreling onward. “Degraded” surprises, with something like a traditional structure and an almost pop-leaning melody to its chorus, twisting the bigness of Preoccupations’ music to sideswipe the clear, finite smallness of its subjects and events. And the 11-minute-long “Memory” is the album’s keystone, with an intimate narrative and a truly timeless post-punk center. There’s love piercing through the iciness here, fighting its way forward in each of the song’s distinct sections. As always, there is something crystalline to what they’ve made, a blast of cold air in a burning hot place. All this adds up to ‘Preoccupations’: a singular, bracing collection that proves what’s punishing can also be soothing, everything can change without disrupting your compass. Your best year can be your worst year at the same time. Whatever sends you flying can also help you land.

The extraordinary, tattoo-bedecked, flamenco-inspired guitarist - and dare we say profane raconteur - that is RM Hubbert (Hubby to you and me) has returned with a new album, Telling the Trees, and it’s every bit as bold, unpredictable and affecting as we could have dared to expect. A reprisal of the collaborative format that so enriched 2012’s SAY Award winning ‘Thirteen Lost & Found’, this new project finds Hubby co-writing at arm’s-length from a dazzling array of musicians, songwriters and lyricists in stark contrast to the previous album’s up close and personal approach. Enlisting an amazingly diverse ensemble of talent, Telling the Trees features: Anneliese Mackintosh | Anneke Kampman | Rachel Grimes | Kathryn Williams | Marnie | Kathryn Joseph | Martha Ffion | Sarah J. Stanley | Aby Vulliamy | Karine Polwart | Eleanor Friedberger The result is a mesmerising collection of styles, songs and instrumentals, linked by their infusion of Hubby’s trademark guitar playing and the sparkling production techniques of Paul Savage at Chem19..

Cackling with energy and warmth, this debut album from the Madrid-based quartet is an effortless joy. Carlotta Cosials and Ana Perrote’s dual vocals circulate in a hazy mist around giddy guitars to produce gorgeous garage-pop gems like the woozy “San Diego” and bouyant “Warts.” But it’s not all sun-drunk and carefree. “Catigadas En El Granero” is a feverish riot while “And I Will Send Your Flowers Back” and “I’ll Be Your Man” reveal the band’s vulnerable—and joyously vengeful—side.

The Scottish duo return harder and darker on second album, *Babes Never Die*, where new drummer Cat Myers powers singer-guitarist Stina Tweeddale through her tales of vengeance and vulnerability. There’s a menacing tone here (the predators of “Sister Wolf”) that warns troublemakers from messing with the invincible young women of “Sea Hearts”. And with weapons like the surfy “Ready for the Magic”, and the epic sludge of “Walking at Midnight”, don’t say they didn’t warn you…

In the four years between Frank Ocean’s debut album, *channel ORANGE*, and his second, *Blonde*, he had revealed some of his private life—he published a Tumblr post about having been in love with a man—but still remained as mysterious and skeptical towards fame as ever, teasing new music sporadically and then disappearing like a wisp on the wind. Behind great innovation, however, is a massive amount of work, and so when *Blonde* was released one day after a 24-hour, streaming performance art piece (*Endless*) and alongside a limited-edition magazine entitled *Boys Don’t Cry*, one could forgive him for being slippery. *Endless* was a visual album that featured the mundane beauty of Ocean woodworking in a studio, soundtracked by abstract and meandering ambient music. *Blonde* built on those ideas and imbued them with a little more form, taking a left-field, often minimalist approach to his breezy harmonies and ever-present narrative lyricism. His confidence was crucial to the risk of creating a big multimedia project for a sophomore album, but it also extended to his songwriting—his voice surer of itself (“Solo”), his willingness to excavate his weird impulses more prominent (“Good Guy,” “Pretty Sweet,” among others). Though *Blonde* packs 17 tracks into one quick hour, it’s a sprawling palette of ideas, a testament to the intelligence of flying one’s own artistic freak flag and trusting that audiences will meet you where you’re at. In this case, fans were enthusiastic enough for *Blonde* to rack up No. 1s on charts around the world.

Whitney’s debut is a haunting set of ‘60s guitar pop. Taking pages from Byrds ballads (“Light Upon the Lake”), pre-psychedelic Beatles (“Golden Days”), and the more placid side of soul (“Dave’s Song”), the duo—comprising former members of Smith Westerns and Unknown Mortal Orchestra—sound cheerful but bittersweet, muted by a sense of melancholy that gives drummer/vocalist Julien Ehrlich’s falsetto a sneaky, surprising depth. Even the album’s most upbeat moment, “The Falls,” feels less like it’s looking forward to something, and more like it’s looking back.

Whitney make casually melancholic music that combines the wounded drawl of Townes Van Zandt, the rambunctious energy of Jim Ford, the stoned affability of Bobby Charles, the American otherworldliness of The Band, and the slack groove of early Pavement. Their debut, ‘Light Upon the Lake’, is due in June on Secretly Canadian, and it marks the culmination of a short, but incredibly intense, creative period for the band. To say that Whitney is more than the sum of its parts would be a criminal understatement. Formed from the core of guitarist Max Kakacek and singing drummer Julien Ehrlich, the band itself is something bigger, something visionary, something neither of them could have accomplished alone. Ehrlich had been a member of Unknown Mortal Orchestra, but left to play drums for the Smith Westerns, where he met guitarist Kakacek. That group burned brightly but briefly, disbanding in 2014 and leaving its members adrift. Brief solo careers and side-projects abounded, but nothing clicked. Making everything seem all the more fraught: both of them were going through especially painful breakups almost simultaneously, the kind that inspire a million songs, and they emerged emotionally bruised and lonelier than ever. Whitney was born from a series of laidback early-morning songwriting sessions during one of the harshest winters in Chicago history, after Ehrlich and Kakacek reconnected - first as roommates splitting rent in a small Chicago apartment and later as musical collaborators passing the guitar and the lyrics sheet back and forth. “We approached it as just a fun thing to do. We never wanted to force ourselves to write a song. It just happened very organically. And we were smiling the whole time, even though some of the songs are pretty sad.” The duo wrote frankly about the break-ups they were enduring and the breakdowns they were trying to avoid. Each served as the other’s most brutal critic and most sympathetic confessor, a sounding board for the hard truths that were finding their way into new songs like “No Woman” and “Follow,” a eulogy for Ehrlich’s grandfather. In exorcising their demons they conjured something else, something much more benign—a third presence, another personality in the music, which they gave the name Whitney. They left it singular to emphasize its isolation and loneliness. Says Kakacek, “We were both writing as this one character, and whenever we were stuck, we’d ask, ‘What would Whitney do in this situation?’ We personified the band name into this person, and that helped a lot. We wrote the record as though one person were playing everything. We purposefully didn’t add a lot of parts and didn’t bother making everything perfect, because the character we had in mind wouldn’t do that.” In those imperfections lies the music’s humanity. Whilst they demoed and toured the new songs, they became more aware of the perfect imperfections of the songs, and needing to strike the right balance, they eventually made the trek out to California, where they recorded with Foxygen frontman and longtime friend, Jonathan Rado. They slept in tents in Rado’s backyard, ate the same breakfast every morning at the same diner in the remote, desolate and completely un-rock n roll San Fernando Valley, whilst they dreamt of Laurel Canyon, or maybe The Band’s hideout in Malibu, or Neil Young’s ranch in Topanga Canyon. The analog recording methods, the same as used by their forebearers, allowed them to concentrate on the songs themselves and create moments that would be powerful and unrepeatable. “Tape forces you to get a take down,” says Kakacek. “We didn’t have enough tracks to record ten takes of a guitar part and choose the best one later. Whatever we put down is all we had. That really makes you as a musician focus on the performance.” The sessions were loose, with room for improvisation and new ideas, as the band expanded from that central duo into a dynamic sextet (septet if you count their trusty soundman). And that’s what you hear – Whitney is the sound of that songwriting duo expanding their group and delivering the sound of a band at their freest, their loosest, their giddiest. Classic and modern at the same time, they revel in concrete details, evocative turns of phrase, and thorny emotions that don’t have exact names. These ten songs on 'Light Upon the Lake' sound like they could have been written at any time in the last fifty years. Ehrlich and Kakacek emerge as imaginative and insightful songwriting partners, impressive in their scope and restraint as they mold classic rock lyricism into new and personal shapes without sound revivalist or retro. “I’m searching for those golden days.” sings Ehrlich, with a subtle ripple of something that sounds like hope, on the track “Golden Days”. It’s a song that defines Whitney as a band. “There’s a lot of true feeling behind these songs,” says Ehrlich. “We wanted them to have a part of our personalities in them. We wanted the songs to have soul.”

Radiohead’s ninth album is a haunting collection of shapeshifting rock, dystopian lullabies, and vast spectral beauty. Though you’ll hear echoes of their previous work—the remote churn of “Daydreaming,” the feverish ascent and spidery guitar of “Ful Stop,” Jonny Greenwood’s terrifying string flourishes—*A Moon Shaped Pool* is both familiar and wonderfully elusive, much like its unforgettable closer. A live favorite since the mid-‘90s, “True Love Waits” has been re-imagined in the studio as a weightless, piano-driven meditation that grows more exquisite as it gently floats away.

Singular adventures in pop oddness, recorded in a nuclear bunker in the east of England. Rosa Walton and Jenny Hollingworth’s debut has many childlike charms: over-sweetened teenage-witch vocals; liberal use of glockenspiel and recorder; and a low-boredom-threshold flightiness that carries the pair from dimly-lit trip-hop (“Deep Six Textbook”) to sinister folk (“Chocolate Sludge Cake”), and lo-fi rave and hip-hop (“Eat Shiitake Mushrooms”). There’s nothing infantile about their execution though, and they layer sound and ideas into enrapturing melodies with skill and fearlessness.

A decade since debut album *Home Sweet Home* saw Kano placed among grime’s chosen few, the east Londoner circles back to his roots. At 30 and with ten years negotiating UK hip-hop’s choppy waters on the clock, *Made in the Manor* sees Kano neatly placed to ruminate on old neighborhoods, family and contemporaries. “Little Sis”, “Deep Blues” and “Endz” are mature, searingly honest and clever reflections, but this is no sentimental collection from an artist winding down. “Hail”, “3 Wheels Up” and “This Is England” are blistering urban commentaries that feel urgent and dangerous.

The playfully titled *Introducing* recasts alt-folkie Karl Blau as a bejeweled country crooner. A gorgeous exercise covering left-field classics by artists like Townes Van Zandt (“If I Needed You”) and Tom T. Hall (“That’s How I Got To Memphis”), the album presents a vision of country more in tune with indie Americana than Nashville, leaning on plush, mellow arrangements and Blau’s beery baritone, which delivers the songs’ lovelorn lyrics with the slightest of winks.

On the gritty, star-studded *Blank Face LP*, ScHoolboy Q is at his very best. Through 17 tracks of heavy-lidded gangsta rap, the incisive L.A. native joins forces with guests both legendary (E-40, Jadakiss, Tha Dogg Pound) and soon-to-be (Vince Staples, Anderson. Paak). “Robbin’ your kids too,” he says on “Groovy Tony / Eddie Kane,” a haunting double feature. “My heart a igloo.”

*Confessions* is a unique, unsuspecting duet of sorts—a compelling collaboration between two singular musical forces. In “Nowheresville,” Teitur takes on a carefree attitude to his poppy lyrics, which are complemented perfectly by Muhly’s upbeat keyboards and woodwinds. “Cat Rescue” cleverly dramatizes a completely relatable situation.

The songwriter transfigures personal tragedy into growling, elemental elegies. On his latest collaboration with the Bad Seeds, Nick Cave pulls us through the gorgeous, groaning terrors of “Anthrocene” and “Jesus Alone” only to deliver us, scarred but safe, to “I Need You” and “Skeleton Tree,” a pair of tender, mournful folk ballads.

An intoxicating ode to chasing adrenaline, the Swedish pop star\'s second album is broken into two chapters: Fairy Dust, which is about the highs, and Fire Fade, which is about the lows. As she explained on Beats 1, there’s plenty of joy in chapter two. “Imaginary Friend,” a song about a gut feeling, was born in a moment of crushing self-doubt. “Whenever someone tells me I can’t do something, it tells me it’s definitely possible,” she said. \"I’m thankful for that.”

Following the dizzying success of their breakout 2013 debut, The 1975 aim even higher. The poignantly titled *I like it when you sleep, for you are so beautiful yet so unaware of it* is a captivating display of all the UK rock chameleons do so well, blending neon ‘80s art-funk confections (“Love Me,” “She’s American”) and heady 21st-century electro-textures (“Somebody Else,” “If I Believe You,” the gorgeous title cut). Held together by frontman Matt Healy’s bold-yet-earnest vocal performances, the result is as anthemic as it is intimate.

The Kendrick Lamar associate sprawls out on his poetic, contemplative second album. Making good on 2014’s enormously promising *Cilvia Demo*, *The Sun’s Tirade* echoes late-night ‘70s soul and its ‘90s counterparts (Erykah Badu, Outkast) rendered in booming, contemporary colors—a fitting backdrop for Rashad’s unsparing reflections on race (“BDay”), youth (“Free Lunch”), depression (“Dressed Like Rappers”), and ambition (“Park”).

The feelings of isolation and disenchantment Scott Hutchison suffered after moving from Glasgow to L.A. two years ago ring through his band’s fifth album. Co-produced by The National’s Aaron Dessner–who knows a thing or two about gently anthemic, adventurously textured alt-rock–*Painting of a Panic Attack* frames Hutchison’s anxieties within stately tapestries of soaring melodies, staccato rhythms, jagged riffs, and electronic flourishes. Venturing into shoegazing’s fluting hypnotics, the sweet sorrow of “Get Out” encapsulates the restraint that ensures everything here is emotionally charged without being overdramatic.

The difference between Charles Bradley and a so-called soul revivalist is that, for Bradley—who was 67 when the third and final album of his lifetime, *Changes*, came out in 2016—soul never died in the first place. Like the work of Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings (whose affiliates the Menahan Street Band provide most of Bradley’s musical backing), *Changes* doesn’t sound like a lost ’60s album so much as a found one, retouched and dusted off, sonically saturated in a way that wouldn’t’ve been possible 50 years ago. And while Bradley spent years as a James Brown impersonator, his delivery has more in common with what you heard in the balladry of Otis Redding: pained and reflective (“Changes”) but resilient (“Good to Be Back Home”) too—the sound of everything to give and nothing left to lose.

Julianna Barwick\'s third album embraces synths to striking effect. Comprising field recordings and studio work, the buzz of traffic encircles *Will*, interwoven with Barwick\'s haunted choirgirl voice. She sounds submerged on “Nebula,” where striking synths dapple the surface of the water, but comes into focus on “Someway”, her voice chiming like church bells. On closing song “See, Know”, her long coo guides jazz percussion and a strident synth lead, the aggression positioning her music in the thrum of the real world.

Julia Jacklin thought she’d be a social worker. Growing up in the Blue Mountains to a family of teachers, Jacklin discovered an avenue to art at the age of 10, thanks to an unlikely source: Britney Spears. Jacklin chanced upon a documentary about the pop star while on family holiday. “By the time Britney was 12 she’d achieved a lot,” says Jacklin.”I remember thinking, ‘Shit, what have I done with my life? I haven’t achieved anything.’ So I was like, ‘Mum, as soon as we get home from this holiday I need to go to singing lessons.’ Classical singing lessons were the only kind in the area, but Jacklin took to it. Voice control was crucial, and Jacklin flourished. But the lack of expression had the teen seeking substance, and she wound up in a high school band, “wearing surf clothing and doing a lot of high jumps” singing Avril Lavigne and Evanescence covers. It wasn’t much but she was hooked. Jacklin’s second epiphany came after high school. Travelling in South America she reconnected with high school friend and future foil Liz Hughes. The two returned home to the Blue Mountains and started a band, bonding over a love of indie-Appalachian folk trio Mountain Man and the songs Hughes was writing. “I would just sing,” says Jacklin. “But as I got my confidence I started playing guitar and writing songs. I wouldn’t be doing music now if it wasn’t for Liz or that band. I never knew it was something I could do. “ Now living in a garage in Glebe and working a day job on a factory production line making essential oils, the 25-year old found time to hone her craft – to examine her turns of phrase, to observe the stretching of her friendship circles, to wonder who she was and who she might become. That document is Jacklin’s masterful debut album, Don’t Let The Kids Win - an intimate examination of a life still being lived. Recorded at New Zealand’s Sitting Room studios with Ben Edwards (Marlon Williams, Aldous Harding, Nadia Reid), Don’t Let The Kids Win courses with the aching current of alt-country and indie-folk, augmented by Jacklin’s undeniable calling cards: her rich, distinctive voice, and her playful, observational wit. You can hear it in opener ‘Pool Party’, a gorgeous lilt bristling with Jacklin’s tale of substance abuse by the pool; in the sparse, ‘Elizabeth’, wrestling with both devotion and admonishment of a friend; in detailing the slow-motion banality of a relationship breakdown in the woozy ‘L.A Dreams’; and in her resolve to accept the passing of time on the snappy fuzz of ‘Coming Of Age’. The album hums with peripheral insights, minute in their moments but together proving an urge to stay curious. “I thought it was going to be a heartbreak record,” says Jacklin of Don’t Let The Kids Win. “But in hindsight I see it’s about hitting 24 and thinking, ‘What the fuck am I doing?’ I was feeling very nostalgic for my youth. When I was growing up I was so ambitious: I’m going to be this amazing social worker, save the world, a great musician, fit, an amazing writer. Then you get to mid-20s and you realise you have to focus on one thing. Even if it doesn’t pay-off, or you feel embarrassed at family occasions because you’re the poor musician still, that’s the decision I made.” In person Jacklin is funny, wry, quick to crack a joke. It makes the blunt honesty and prickly insight laced through her songwriting disarming, a dissonance she delights in. “Especially coming from my family,” says Jacklin. “They don’t talk about feelings at all. I love writing songs about them and watching them listen and squirm. To me that’s great. I enjoy it.” The title track was the last song Jacklin wrote for the album. “My sister’s getting married soon,” she says of the closer. “And it hit me – we used to be two young girls and now that part of our lives is over. Seeing her talking about wanting to have a baby and…it’s like, man I can’t believe we’re already here.” Don’t mistake this awareness for nostalgia. “It’s not that I want to go back to that time at all,” says Jacklin. “It’s trying to figure out how to be responsible when you don’t identify with who you were anymore.” “All my friends at this age are freaking out. Everyone’s constantly talking about being old. Don’t Let The Kids Win is saying yeah we’re getting older but it’s not so special. It’s not unique. Everyone has dealt with this and it’s going to keep feeling weird. So I’m freaking out about it too but that song is trying to convince myself: let’s live now and just be old when we’re old.”

Following his acclaimed debut Whelm, London-based singer-songwriter and pianist Douglas Dare returns with his sophomore album Aforger on October 14th. In a digital age where memories are mimicked by pixels and identity is as malleable as static, Douglas Dare’s new album Aforger questions the boundaries between reality and fiction. Inspired by recent events and revelations encountered in his life these songs depict Dare at his most vulnerable, whilst simultaneously reflecting our own obsession with reality and technology back at us. Aforger was mixed at the iconic Abbey Road Studios and produced by long-time collaborator Fabian Prynn. In the following conversation Douglas strips back the personal journeys and realisations which preceded its recording. Having first toured the world to support of the likes of Ólafur Arnalds, Nils Frahm and Fink, followed by European headline tours in 2014 and 2015, this autumn will see Douglas return to the live circuit for a series of select shows in London and beyond. In a conversation with Douglas Dare on July 11th 2016: The album title plays with the idea of a forger – someone creating imitations or copies, and reimagines them as the creator of something that’s no longer real. Prior to writing the record, I came out to my father and came out of a long relationship, both were hugely challenging for me and questioned my idea of identity and reality. These thoughts leaked out into the record and formed the core of Aforger. I was determined not to write a break-up album or repeat what I’d done before.. I grew up on quite an isolated farm in Dorset, surrounded by fields and not much besides. My mother taught piano from home and we didn’t have a computer, or the internet or mobile phones. In fact, my family still chooses not to use these things. It’s worlds apart from my life now in London where technology seems to dominate everything I do. After finding out my boyfriend had been leading this double-life, I became obsessed with the question of what is real and George Orwell’s 1984 felt appropriate for me to re-read. Orwell explains this idea of reality control and Doublethink, and it struck a chord with me. The idea that truth can be steered or changed, and we might be able to believe two contradictory things at once. In my case, ignorance was my protection from the truth and ignorance really is bliss, until you’re no longer ignorant. Binary talks about the idea that technology is allowing us to live on after we’re gone. A relative of mine whose parent passed away kept a picture of them on their phone as a background image. A friend saw this and asked ‘how can you have that there to constantly remind you of your loss?’ They replied, ‘no I have to, it shows me that they’re still here’. This resonated with me and I thought ‘okay, this is just an image to me but to them it’s more than a reminder or a reassurance, it’s a reality’. At the same time, I was finding myself haunted by the digital reminder of my ex-partner and wishing they would disappear. I had to realise that it’s all just pixels on a screen. I think New York can be thought of as this fabricated, magical place. I was there with my boyfriend after touring the U.S., but when I came back to London I discovered all these lies and began questioning everything. I even questioned whether New York actually happened or not. New York is a song that’s literally describing that very real feeling of not knowing who or what to believe any more – scary and magical at the same time. Lyrically I wanted to be as honest as possible. The album deals with so much dishonesty, so I felt the lyrics had to be the counterbalance. I was inspired by Björk’s album Vulnicura and how everything is almost awkward in its honesty. Like my first album, Aforger started as poetry, but I consciously tried to be less poetic. For instance, Oh Father is an example of complete unambiguity. It’s certainly the most personal song I’ve put out there, and the realisation that people may hear it makes me feel very vulnerable. That’s the most real feeling of all for me right now.

Intoxicating future-jazz messages from a distant galaxy are beamed your way on this freewheeling psychedelic debut. Conceived as a side project for saxophonist Shabaka Hutching, TCiC benefit hugely from the fact both synth-specialist Dan Leavers and drummer Maxwell Hallett know their way around a 3am dancefloor. “Space Carnival” packs hyperactive afrobeat horns and “Lightyears”—augmented by Joshua Idehen’s charismatic spoken word—is a stunning nebula of frenzied improvisation.

The Comet Is Coming. Our saviours Danalogue The Conqueror, Betamax Killer and King Shabaka come bearing their debut album Channel The Spirits. A prophetic document. A celebration. The beginning of the end. Marvel! As it blazes a streak of phosphorescent beauty across the night sky. Listen! As a trailing meteor shower drops hot coals hissing into topographical oceans. Inhale! The burning funk of strange new flavours. The sound of the future... today. Channel The Spirits is shortlisted for the 2016 Mercury Prize.

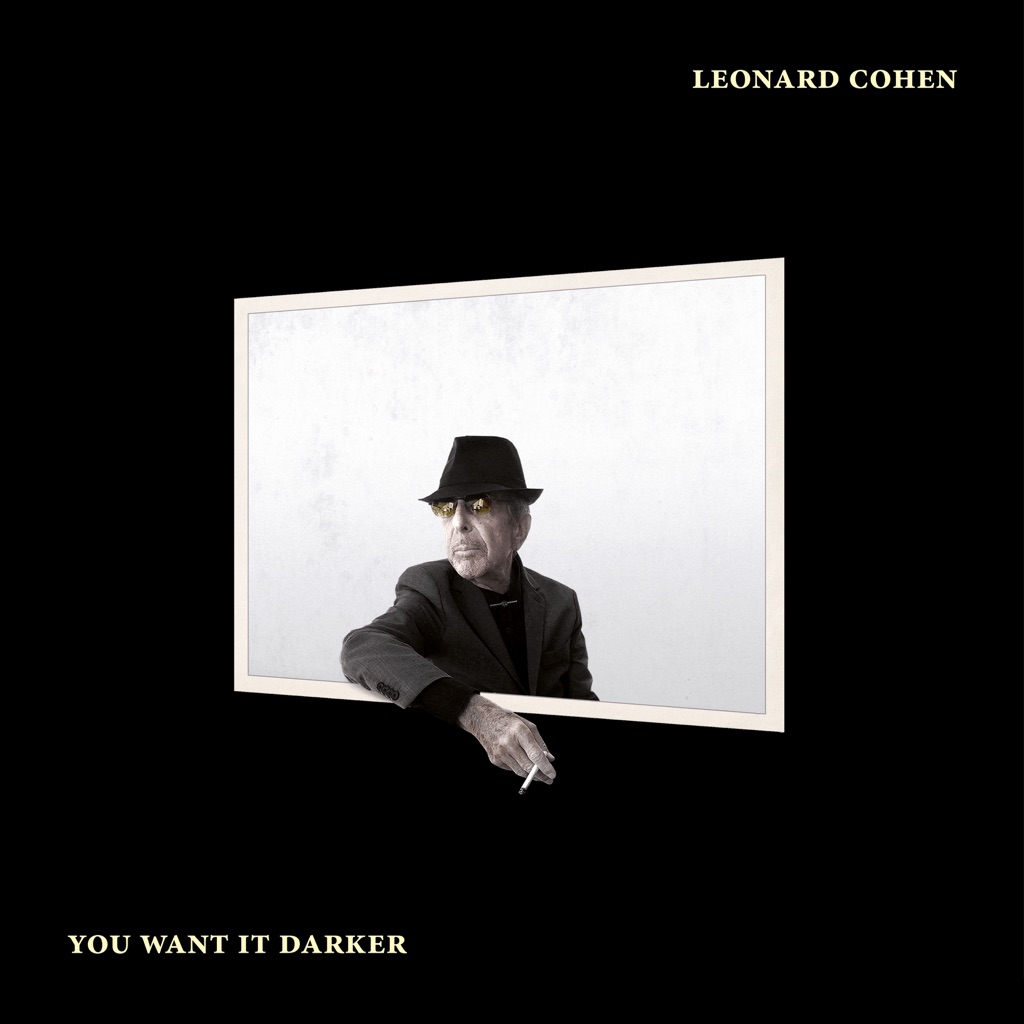

*You Want It Darker* joins *Old Ideas* and *Popular Problems* in a trio of gorgeous, ruminative albums that find Cohen settling his affairs, spiritual (“Leaving the Table”), romantic (“If I Didn’t Have Your Love”), and otherwise. At 35, he sounded like an old man—at 82, he sounds eternal.

The UK art-rock outfit’s brilliant new album. *Boy King* is that most satisfying of things. A daring step in a fresh direction that comes off beautifully. It’s a lascivious, muscular record, pulsing with crunching guitars and Hayden Thorpe’s prodigious falsetto. “Big Cat”, “Get My Bang”, and “He the Colossus” are the taut and slithery bangers, while closer “Dreamliner”—gorgeous and operatic—serves to highlight the far-reaching talents of a very special band.