Slant Magazine's 25 Best Albums of 2011

The ladies truly dominate the upper reaches of our 2011 albums list in a way they haven’t ever before.

Published: December 14, 2011 18:54

Source

For her 11th album, PJ Harvey steps away from the strident agit-folk that made her name in the ‘90s, writing instead a subtle and hauntingly beautiful record that is simultaneously a meditation on the brutality and futility of the First World War and a nostalgic paean to her home country. As is her custom, guitars take center stage, all eerie and drenched in chilling reverb (“In the Dark Places”), while Harvey’s vocals are uncharacteristically understated and soft, reaching tremulously to the top of her register on “Hanging in the Wire.”

Any honey flowing through Lykke Li\'s coy pop fully hardened on this dark and doomy follow-up to her 2008 debut album. The Swedish singer/songwriter traps the loss of youth and love in a warped wall of sound that echoes vintage girl-group pop on big, gushing torch songs like \"Unrequited Love\" and \"Sadness Is a Blessing.\" But she comes into her own when harnessing her womanly power, with big, booming percussion on the tribal-esque thriller \"Get Some.\"

After two previous releases, St. Vincent (a.k.a. Annie Clark) finds a way to channel her avant-garde instincts in more accessible directions, displaying a firm grasp on pop songwriting forms even as she subverts them. In tandem with producer John Congleton, she plays nervous industrial beats and quivering keyboards against billowing ‘60s-ish melodies. Her cooing vocals on “Cruel” and “Surgeon” insinuate dark scenarios of betrayal and abandonment, transcending mere irony into something palpably sinister. More direct in their intentions are “Cheerleader” (an anthem of personal liberation) and “Champagne Year” (a jaundiced look at success). If Clark’s lyrics tease and dazzle, her music hits hard sonically, clattering to a galloping groove on “Hysterical Strength” and erupting into guitar-fueled cacophony on “Northern Lights.” The otherworldly grandeur of Kate Bush or Björk is recalled on tracks like “Chloe In the Afternoon.” But St. Vincent is in a class all her own as she exorcises sexual demons, grapples with psychic breakdown, and achieves an uncanny catharsis.

On their sophomore album, Bon Iver add just a touch of color to their stark indie folk, while retaining every bit of its intimacy. The haunting chill of solitude continues to cling to Justin Vernon\'s every word, even when his lilting falsetto radiates warmth over a rich bed of acoustic guitar, synths, and horns. The drama exudes from every little sound—the soft, pattering snare guiding \"Perth,\" the delicate whirrs of sax on \"Holocene,\" and the big, gleaming synths on \'80s-esque noir jam \"Beth / Rest.\"

Bon Iver, Bon Iver is Justin Vernon returning to former haunts with a new spirit. The reprises are there – solitude, quietude, hope and desperation compressed – but always a rhythm arises, a pulse vivified by gratitude and grace notes. The winter, the legend, has faded to just that, and this is the new momentary present. The icicles have dropped, rising up again as grass.

The plump furnishings of their first two albums gone, *Smother is a heartbroken ruin where Wild Beasts add grave, staticky synths to their graceful guitar pop. It turns out they do heartbreak just as well as they do lust, and survey their own failings with the acuity they brought to British mating rituals on Two Dancers. They wring loss from a plate of abandoned breakfast on “Deeper” and Hayden Thorpe gasps at his own cruel nature on “Plaything”.*

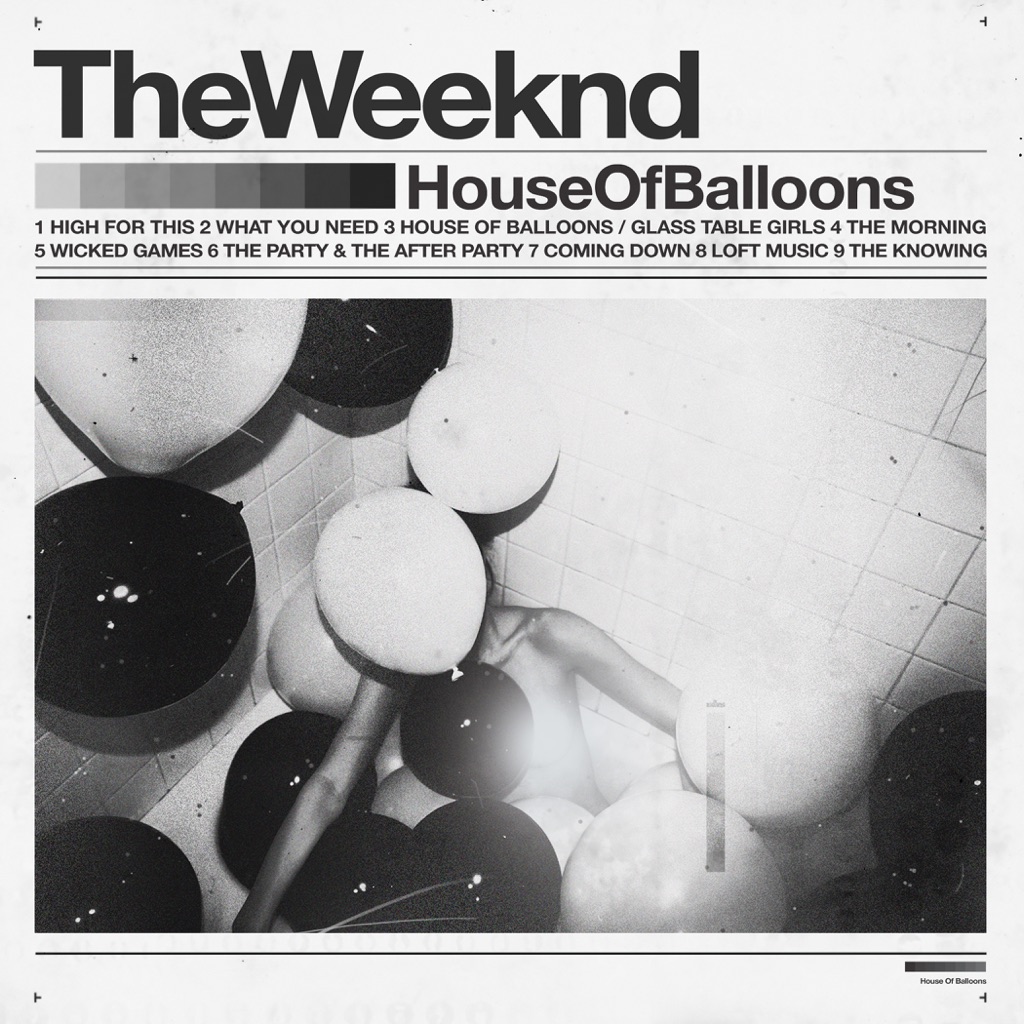

When The Weeknd’s debut mixtape, *House of Balloons*, dropped in 2011, it was clear, even then, that something had shifted. This was a divergent kind of R&B that hinged on atmospherics over vocal prowess—an almost soulless quality in a genre built around soul. At the time, The Weeknd was largely anonymous, hiding in the shadows of his own music, the aloofness only adding to the allure. He was no one and yet everyone, as his raw, bruised candor resonated with fans suffering the effects of overexposure and contradicting desires to both feel and be numb simultaneously. He was a decent enough singer (his falsetto often drew comparisons to Michael Jackson), but it was the one-two punch of the nocturnal sound and indulgent lyrics—the darkness, the dysfunction, the hazy synth-bath of it all—that gave it staying power. When he says, “Trust me, girl, you wanna be high for this,” as he declares on the opening track, it\'s hard to tell whether it\'s an invitation or a warning, but it landed on ears that were all too happy to oblige. *House of Balloons*, here now in its original form with all samples restored, introduces the sentiment that has underscored nearly all of The Weeknd\'s music that\'s followed: a blurring of the lines between love and addiction, between having a good time and being consumed by it. In multi-part songs such as “House of Balloons/Glass Table Girls” and “The Party & The After Party,” a night\'s zenith and nadir are never too far apart; his audience, like his women, are held captive by the mercurial nature of his moods. A line like “Bring your love, baby, I could bring my shame/Bring the drugs, baby, I could bring my pain,” from lead single “Wicked Games,” serves as a kind of mission statement for the mixtape\'s (and, perhaps, the singer himself\'s) central tension. In the exchange of affection and substances, there exists an emotional transference wherein power is gained by feeling the least. The Weeknd taps into our id-driven urges for pleasure and domination and rewards them again and again. Cruelty somehow becomes sexy in this world where detachment—from everything—is the only goal; the music that he’s created as a soundtrack continues to leave its audience equally insatiable. As the years go by, *House of Balloons* has become increasingly timeless. It remains as much an exercise in mythmaking (and star-making) for The Weeknd as a testament to our own pathological impulses, sending us barreling towards destruction and ecstasy all at once.

Meshell Ndegeocello’s ninth release burns with a quiet fire. Emotionally charged and sonically rich, *Weather* is an intimate recording supported by complex arrangements that ride along with her elastic bass playing and powerful, versatile voice. She sounds vulnerable and raw on the heartrending piano ballad “Oyster,” defiant on “Rapid Fire,” and sultry on “Crazy and Wild” and the title track. Slowing the tempo to a crawl, she smolders through the sparse and haunting “Objects in Mirror Are Closer Than They Appear” and “Feeling for the Wall,” as if struggling to contain her emotions. “Dirty World” and “Dead End,” two soulful uptempo numbers, offer relief from the album’s dark undercurrent, as does a tender cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Chelsea Hotel.” Produced by Joe Henry, the album is a study in control and subtlety as it finds a perfect pitch between the experimental and pop-oriented sides of her musical personality.

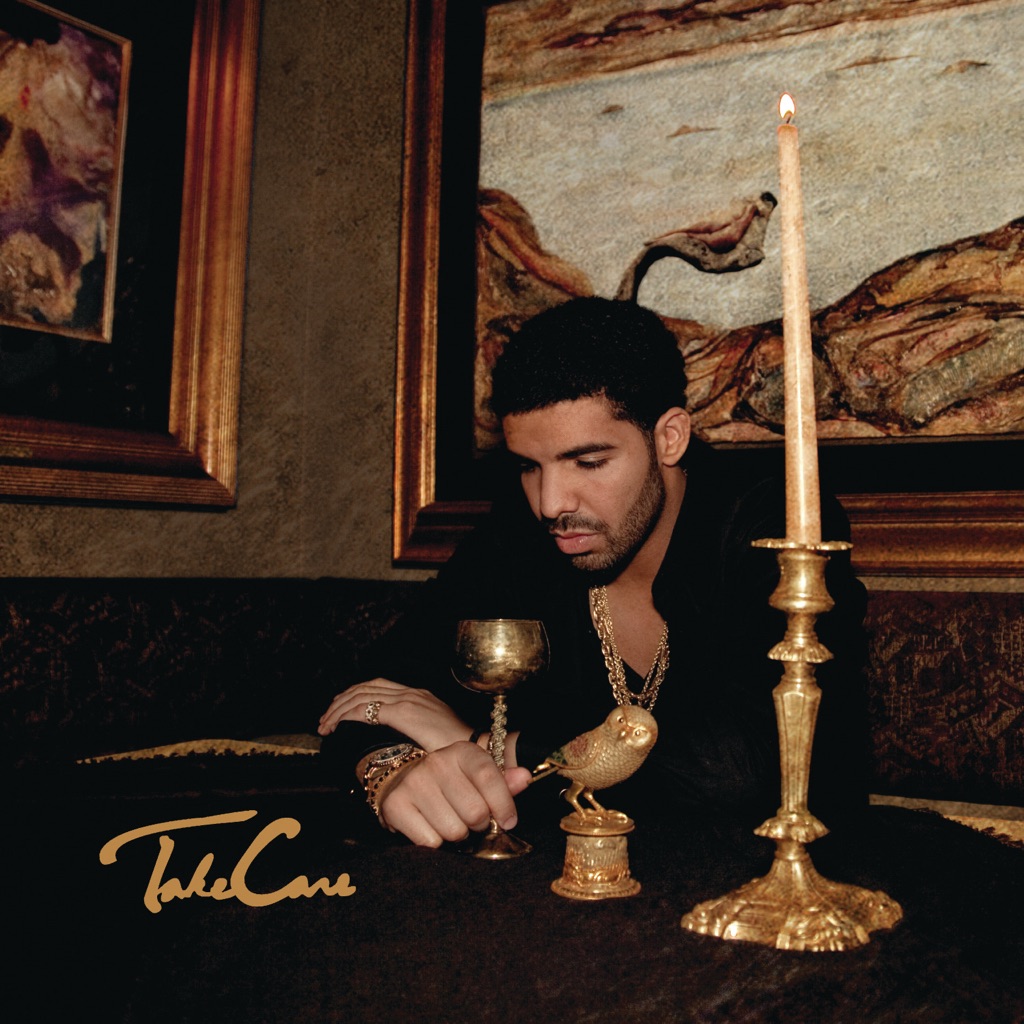

Drake\'s still fretting about lost love, the perils of fame, and connecting with his fellow man; just look at him on the cover, staring into a golden chalice like a lonely king. These naked emotions, however, are what make *Take Care* a classic, placing Drake in a league with legendary emoters like Marvin Gaye and Al Green. \"Marvin\'s Room\" is one of the most sullen singles to hit the Top 100, and the winsome guitar howls of the title track, coproduced by Jamie xx, are among of the most recognizable sounds of the decade.

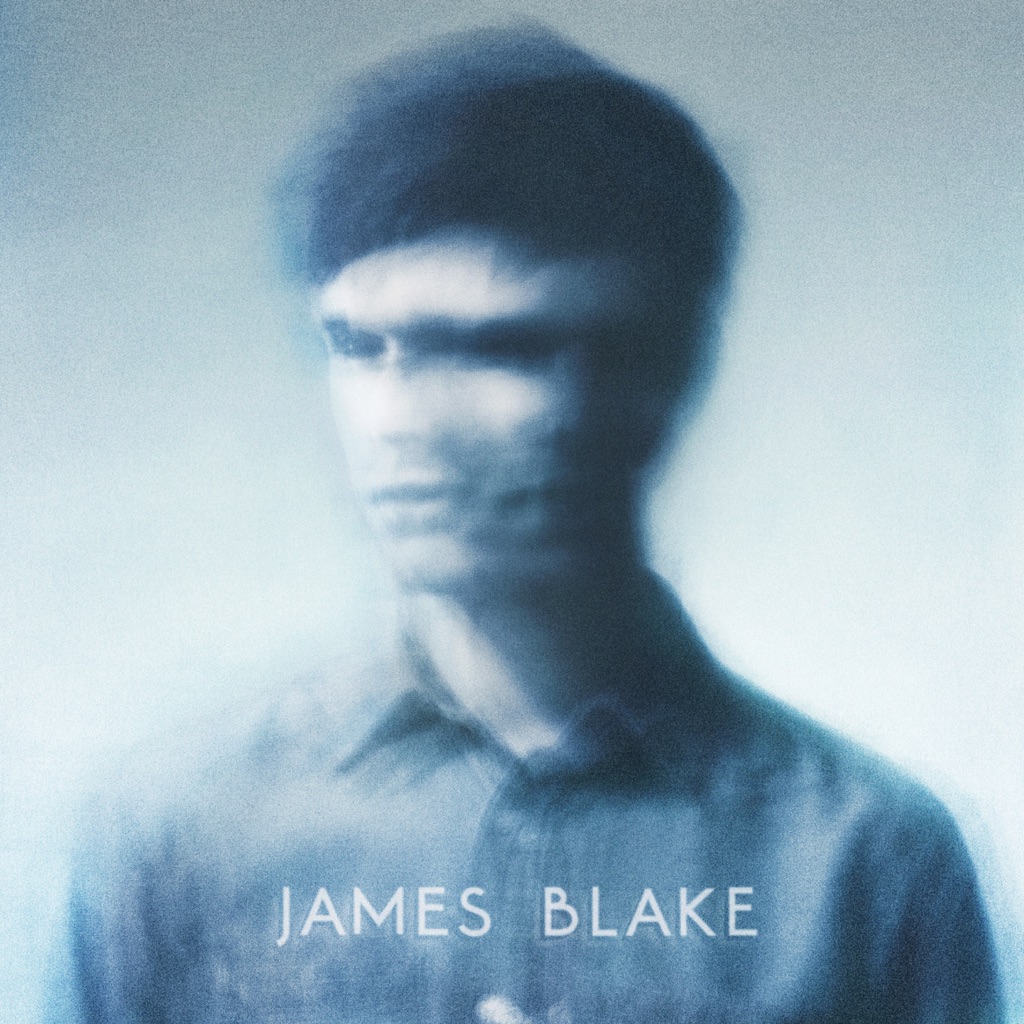

The British electronic pop artist James Blake was showered with attention and nominations in his native land in 2010 and 2011. That’s striking because Blake’s music is truly strange. Drawing on the weirder side of R&B as well as leftfield English dance music, the singer/songwriter crafts spare and spooky gems. On “Unluck,” simple electric piano (evocative of ‘70s Sly & The Family Stone), itchy rhythmic tics, and sound blurts serve as a backdrop as Blake sings, at times through a vocoder. The track sounds like something you would hear while a producer was tinkering with a mix, but here it’s the intriguing end result. One of the album’s singles, “The Wilhelm Scream,” is as lovely as it is eldritch. The catchy melody is surrounded by music that is both minimal and ambient. Blake is capable of all sorts of odd moves: on “I Never Learnt to Share,” a beat doesn’t kick in until the cut is more than half over. One of the album’s highlights is a cover of the Canadian songwriter Feist’s “Limit to Your Love,” which consists of his naked voice, piano, and a haunted atmosphere.

It’s fitting that *Eye Contact* — the fifth studio album from Gang Gang Dance — found a home on the esteemed 4AD label; after all, some of the imprint’s earliest signings were purveyors of the sort of mystical/global amalgam favored by Gang Gang Dance. After the Brooklyn quartet injected their own unique brand of experimental music with a tougher street vibe — highlighting the electronic over the organic on 2009’s *Saint Dymphna* — here the band polishes the edges to a softer finish, each track flowing easily to the next in a mix of down-tempo beats, Bollywood melodies and Middle Eastern-inflected rhythms. The epic opener “Glass Jar” is a fantastic intro to the journey ahead, morphing from a fluttering, primordial space-trip to a climactic landing, a splash-down against an intense palette of sunset color and galactic promise. One of the most muscular tracks, the breathless “MindKilla,” has been given the remix treatment by his royal highness, Lee Scratch Perry, and is well worth seeking out.

Finally departed from his old record label, Hank Williams III released three albums on September 6, 2011. The other two releases, *Attention Deficit Domination* and *Cattle Callin*, focus on his doom metal and cattle-core interests, while *Ghost to A Ghost / Gutter Town* tends to his country-music lineage. The son of Hank Williams, Jr. and grandson of Hank Williams, Sr., Hank 3 understands the music from the inside out. “The Devil’s Movin’ In” plays like a ghostly Appalachian blues that Will Oldham’s been seeking his entire career. “Ray Lawrence Jr.” is written and performed by his bandmate of the same name. “Time to Die” plays like a tribal ghost dance. “Ghost to a Ghost” itself, with Primus’ Les Claypool and Tom Waits, is some high weirdness that makes itself better known on the second half of the album with “Chord of the Organ,” “Chaos Queen” and “Thunderplain.” “Outlaw Convention” and “C\*\*t of a Bitch” make clear Williams’ decision to remain with “outlaw country.” “Gutter Stomp” is informed by a Cajun influence, while “Fadin’ Moon” throws country fiddle and Tom Waits into the mix.

After breaking with their drummer following their last album, Catherine McCandless and Stephen Ramsay move on to forge a new sound for Young Galaxy on the aptly titled *Shapeshifting*. Teaming up with producer Dan Lissvik, half of the Swedish duo Studio, their third release continues their dream-wave fascination while adding elements of synth pop, electronica, and dance music. The result is a lush album built around shimmering layers of sound, twinkling keyboards, slinky guitar figures, and some delightfully melodramatic production touches. McCandless and Ramsay trade lead vocals throughout, and the stark differences between their voices keeps things interesting as they sing about stars, chemical reactions, the elements, astrology, and various agents of energy and change. This vocal contrast is particularly apparent on the excellent “Peripheral Visionaries,” on which they harmonize to great effect. Elsewhere there’s dance music (“We Have Everything”), new-wave inspired pop (“Phantoms,” “B.S.E.,”), and arresting and textured tracks featuring McCandless’ rich vocals (“Blown Minded,” “For Dear Life,” “High and Goodbye”).

Florence + The Machine deliver one baroque-pop anthem after another on *Ceremonials*. Booming percussion, strings, echoing keyboards, and big guitars create a towering platform of sound from which Florence Welch emotes with a fury. Her powerful voice erupts amid a gospel choir on “Shake It Out,” “What the Water Gave Me,” and “Leave My Body,” while tribal drums fuel “No Light, No Light” and “Heartlines.”

Ben Sollee is a classically trained cellist who has worked on a wide variety of projects. He’s played in the Sparrow Quartet with Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn, recorded with My Morning Jacket, and released an album with Daniel Martin Moore (*Dear Companion*). Stylistically, *Inclusions*, his second solo release, is a country/folk/modern pop hybrid with a twist. Cello is the primary instrument here and that lends a distinct feel to the album. Whether he’s bowing or plucking it the texture is everywhere, and Sollee uses it in many inventive ways to support these carefully constructed songs. It’s haunting on the sparse “Embrace,” rustic on “Close to You,” and when backed by jazzy woodwinds, brass, and tympani on “Bible Belt,” it gives the song a mellow, late night feel. On “Cluttered Mind” the cello supports subdued banjo and bass clarinet, and in “Electrified” it’s used to create a funky, skittering groove. His lyrics are as interesting as the compositions, filled with compelling imagery and observations, making the album work on several levels. *Inclusions* aims for the head and the heart and hits both.

While they’re clearly inspired by classic late ‘80s and early ‘90s shoegaze and indie rock—Ride, Dinosaur Jr., Pavement—this young London quintet proved on their self-titled debut that they could spin their influences into a memorable, blissful, fuzzed-out sound all their own. Whether heavy in the red on the ebullient “Holing Out” or swooning on the sweet, reverb-laden ballad “Stutter,” Yuck’s sunny songwriting has that sense of infinite possibility that, at its best, underground rock music is all about.