A Wednesday song is a quilt. A short story collection, a half-memory, a patchwork of portraits of the American south, disparate moments that somehow make sense as a whole. Karly Hartzman, the songwriter/vocalist/guitarist at the helm of the project, is a story collector as much as she is a storyteller: a scholar of people and one-liners. Rat Saw God, the Asheville quintet’s new and best record, is ekphrastic but autobiographical and above all, deeply empathetic. Across the album’s ten tracks Hartzman, guitarist MJ Lenderman, bassist Margo Shultz, drummer Alan Miller, and lap/pedal steel player Xandy Chelmis build a shrine to minutiae. Half-funny, half-tragic dispatches from North Carolina unfurling somewhere between the wailing skuzz of Nineties shoegaze and classic country twang, that distorted lap steel and Hartzman’s voice slicing through the din. Rat Saw God is an album about riding a bike down a suburban stretch in Greensboro while listening to My Bloody Valentine for the first time on an iPod Nano, past a creek that runs through the neighborhood riddled with broken glass bottles and condoms, a front yard filled with broken and rusted car parts, a lonely and dilapidated house reclaimed by kudzu. Four Lokos and rodeo clowns and a kid who burns down a corn field. Roadside monuments, church marquees, poppers and vodka in a plastic water bottle, the shit you get away with at Jewish summer camp, strange sentimental family heirlooms at the thrift stores. The way the South hums alive all night in the summers and into fall, the sound of high school football games, the halo effect from the lights polluting the darkness. It’s not really bright enough to see in front of you, but in that stretch of inky void – somehow – you see everything. Rat Saw God was written in the months immediately following Twin Plagues’ completion, and recorded in a week at Asheville’s Drop of Sun studio. While Twin Plagues was a breakthrough release critically for Wednesday, it was also a creative and personal breakthrough for Hartzman. The lauded record charts feeling really fucked up, trauma, dropping acid. It had Hartzman thinking about the listener, about her mom hearing those songs, about how it feels to really spill your guts. And in the end, it felt okay. “I really jumped that hurdle with Twin Plagues where I was not worrying at all really about being vulnerable – I was finally comfortable with it, and I really wanna stay in that zone.” The album opener, “Hot Rotten Grass Smell,” happens in a flash: an explosive and wailing wall-of-sound dissonance that’d sound at home on any ‘90s shoegaze album, then peters out into a chirping chorus of peepers, a nighttime sound. And then into the previously-released eight-and-half-minute sprawling, heavy single, “Bull Believer.” Other tracks, like the creeping “What’s So Funny” or “Turkey Vultures,” interrogate Hartzman’s interiority - intimate portraits of coping, of helplessness. “Chosen to Deserve” is a true-blue love song complete with ripping guitar riffs, skewing classic country. “Bath County” recounts a trip Hartzman and her partner took to Dollywood, and time spent in the actual Bath County, Virginia, where she wrote the song while visiting, sitting on a front porch. And Rat Saw God closer “TV in the Gas Pump” is a proper traveling road song, written from one long ongoing iPhone note Hartzman kept while in the van, its final moments of audio a wink toward Twin Plagues. The reference-heavy stand-out “Quarry” is maybe the most obvious example of the way Hartzman seamlessly weaves together all these throughlines. It draws from imagery in Lynda Barry’s Cruddy; a collection of stories from Hartzman’s family (her dad burned down that cornfield); her current neighbors; and the West Virginia street from where her grandma lived, right next to a rock quarry, where the explosions would occasionally rock the neighborhood and everyone would just go on as normal. The songs on Rat Saw God don’t recount epics, just the everyday. They’re true, they’re real life, blurry and chaotic and strange – which is in-line with Hartzman’s own ethos: “Everyone’s story is worthy,” she says, plainly. “Literally every life story is worth writing down, because people are so fascinating.” But the thing about Rat Saw God - and about any Wednesday song, really - is you don’t necessarily even need all the references to get it, the weirdly specific elation of a song that really hits. Yeah, it’s all in the details – how fucked up you got or get, how you break a heart, how you fall in love, how you make yourself and others feel seen – but it’s mostly the way those tiny moments add up into a song or album or a person.

Part of what makes Danny Brown and JPEGMAFIA such a natural pair is that they stick out in similar ways. They’re too weird for the mainstream but too confrontational for the subtle or self-consciously progressive set. And while neither of them would be mistaken for traditionalists, the sample-scrambling chaos of tracks like “Burfict!” and “Shut Yo Bitch Ass Up/Muddy Waters” situate them in a lineage of Black music that runs through the comedic ultraviolence of the Wu-Tang Clan back through the Bomb Squad to Funkadelic, who proved just because you were trippy didn’t mean you couldn’t be militant, too.

The Murder Capital’s second studio album Gigi’s Recovery, produced by John Congleton, will be released on January 20, 2023 via Human Season Records. Painting by Peter Doyle and designed by Aidan Cochrane.

“You can feel a lot of motion and energy,” Caroline Polachek tells Apple Music of her second solo studio album. “And chaos. I definitely leaned into that chaos.” Written and recorded during a pandemic and in stolen moments while Polachek toured with Dua Lipa in 2022, *Desire, I Want to Turn Into You* is Polachek’s self-described “maximalist” album, and it weaponizes everything in her kaleidoscopic arsenal. “I set out with an interest in making a more uptempo record,” she says. “Songs like ‘Bunny Is a Rider,’ ‘Welcome to My Island,’ and ‘Smoke’ came onto the plate first and felt more hot-blooded and urgent than anything I’d done before. But of course, life happened, the pandemic happened, I evolved as a person, and I can’t really deny that a lunar, wistful side of my writing can never be kept out of the house. So it ended up being quite a wide constellation of songs.” Polachek cites artists including Massive Attack, SOPHIE, Donna Lewis, Enya, Madonna, The Beach Boys, Timbaland, Suzanne Vega, Ennio Morricone, and Matia Bazar as inspirations, but this broad church only really hints at *Desire…*’s palette. Across its 12 songs we get trip-hop, bagpipes, Spanish guitars, psychedelic folk, ’60s reverb, spoken word, breakbeats, a children’s choir, and actual Dido—all anchored by Polachek’s unteachable way around a hook and disregard for low-hanging pop hits. This is imperial-era Caroline Polachek. “The album’s medium is feeling,” she says. “It’s about character and movement and dynamics, while dealing with catharsis and vitality. It refuses literal interpretation on purpose.” Read on for Polachek’s track-by-track guide. **“Welcome to My Island”** “‘Welcome to My Island’ was the first song written on this album. And it definitely sets the tone. The opening, which is this minute-long non-lyrical wail, came out of a feeling of a frustration with the tidiness of lyrics and wanting to just express something kind of more primal and urgent. The song is also very funny. We snap right down from that Tarzan moment down to this bitchy, bratty spoken verse that really becomes the main personality of this song. It’s really about ego at its core—about being trapped in your own head and forcing everyone else in there with you, rather than capitulating or compromising. In that sense, it\'s both commanding and totally pathetic. The bridge addresses my father \[James Polachek died in 2020 from COVID-19\], who never really approved of my music. He wanted me to be making stuff that was more political, intellectual, and radical. But also, at the same time, he wasn’t good at living his own life. The song establishes that there is a recognition of my own stupidity and flaws on this album, that it’s funny and also that we\'re not holding back at all—we’re going in at a hundred percent.” **“Pretty in Possible”** “If ‘Welcome to My Island’ is the insane overture, ‘Pretty in Possible’ finds me at street level, just daydreaming. I wanted to do something with as little structure as possible where you just enter a song vocally and just flow and there\'s no discernible verses or choruses. It’s actually a surprisingly difficult memo to stick to because it\'s so easy to get into these little patterns and want to bring them back. I managed to refuse the repetition of stuff—except for, of course, the opening vocals, which are a nod to Suzanne Vega, definitely. It’s my favorite song on the album, mostly because I got to be so free inside of it. It’s a very simple song, outside a beautiful string section inspired by Massive Attack’s ‘Unfinished Sympathy.’ Those dark, dense strings give this song a sadness and depth that come out of nowhere. These orchestral swells at the end of songs became a compositional motif on the album.” **“Bunny Is a Rider”** “A spicy little summer song about being unavailable, which includes my favorite bassline of the album—this quite minimal funk bassline. Structurally on this one, I really wanted it to flow without people having a sense of the traditional dynamics between verses and choruses. Timbaland was a massive influence on that song—especially around how the beat essentially doesn\'t change the whole song. You just enter it and flow. ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ was a set of words that just flowed out without me thinking too much about it. And the next thing I know, we made ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ thongs. I love getting occasional Instagram tags of people in their ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ thongs. An endless source of happiness for me.” **“Sunset”** “This was a song I began writing with Sega Bodega in 2020. It sounded completely nothing like the others. It had a folk feel, it was gypsy Spanish, Italian, Greek feel to it. It completely made me look at the album differently—and start to see a visual world for them that was a bit more folk, but living very much in the swirl of city life, having this connection to a secret, underground level of antiquity and the universalities of art. It was written right around a month or two after Ennio Morricone passed away, so I\'d been thinking a lot about this epic tone of his work, and about how sunsets are the biggest film clichés in spaghetti westerns. We were laughing about how it felt really flamenco and Spanish—not knowing that a few months later, I was going to find myself kicked out of the UK because I\'d overstayed my visa without realizing it, and so I moved my sessions with Sega to Barcelona. It felt like the song had been a bit of a premonition that that chapter-writing was going to happen. We ended up getting this incredible Spanish guitarist, Marc Lopez, to play the part.” **“Crude Drawing of an Angel”** “‘Crude Drawing of an Angel’ was born, in some ways, out of me thinking about jokingly having invented the word ‘scorny’—which is scary and horny at the same time. I have a playlist of scorny music that I\'m still working on and I realized that it was a tone that I\'d never actually explored. I was also reading John Berger\'s book on drawing \[2005’s *Berger on Drawing*\] and thinking about trace-leaving as a form of drawing, and as an extremely beautiful way of looking at sensuality. This song is set in a hotel room in which the word ‘drawing’ takes on six different meanings. It imagines watching someone wake up, not realizing they\'re being observed, whilst drawing them, knowing that\'s probably the last time you\'re going to see them.” **“I Believe”** “‘I Believe’ is a real dedication to a tone. I was in Italy midway through the pandemic and heard this song called ‘Ti Sento’ by Matia Bazar at a house party that blew my mind. It was the way she was singing that blew me away—that she was pushing her voice absolutely to the limit, and underneath were these incredible key changes where every chorus would completely catch you off guard. But she would kind of propel herself right through the center of it. And it got me thinking about the archetype of the diva vocally—about how really it\'s very womanly that it’s a woman\'s voice and not a girl\'s voice. That there’s a sense of authority and a sense of passion and also an acknowledgment of either your power to heal or your power to destroy. At the same time, I was processing the loss of my friend SOPHIE and was thinking about her actually as a form of diva archetype; a lot of our shared taste in music, especially ’80s music, kind of lined up with a lot of those attitudes. So I wanted to dedicate these lyrics to her.” **“Fly to You” (feat. Grimes and Dido)** “A very simple song at its core. It\'s about this sense of resolution that can come with finally seeing someone after being separated from them for a while. And when a lot of misunderstanding and distrust can seep in with that distance, the kind of miraculous feeling of clearing that murk to find that sort of miraculous resolution and clarity. And so in this song, Grimes, Dido, and I kind of find our different version of that. But more so than anything literal, this song is really about beauty, I think, about all of us just leaning into this kind of euphoric, forward-flowing movement in our singing and flying over these crystalline tiny drum and bass breaks that are accompanied by these big Ibiza guitar solos and kind of Nintendo flutes, and finding this place where very detailed electronic music and very pure singing can meet in the middle. And I think it\'s something that, it\'s a kind of feeling that all of us have done different versions of in our music and now we get to together.” **“Blood and Butter”** “This was written as a bit of a challenge between me and Danny L Harle where we tried to contain an entire song to two chords, which of course we do fail at, but only just. It’s a pastoral, it\'s a psychedelic folk song. It imagines itself set in England in the summer, in June. It\'s also a love letter to a lot of the music I listened to growing up—these very trance-like, mantra-like songs, like Donna Lewis’ ‘I Love You Always Forever,’ a lot of Madonna’s *Ray of Light* album, Savage Garden—that really pulsing, tantric electronic music that has a quite sweet and folksy edge to it. The solo is played by a hugely talented and brilliant bagpipe player named Brighde Chaimbeul, whose album *The Reeling* I\'d found in 2022 and became quite obsessed with.” **“Hopedrunk Everasking”** “I couldn\'t really decide if this song needed to be about death or about being deeply, deeply in love. I then had this revelation around the idea of tunneling, this idea of retreating into the tunnel, which I think I feel sometimes when I\'m very deeply in love. The feeling of wanting to retreat from the rest of the world and block the whole rest of the world out just to be around someone and go into this place that only they and I know. And then simultaneously in my very few relationships with losing someone, I did feel some this sense of retreat, of someone going into their own body and away from the world. And the song feels so deeply primal to me. The melody and chords of it were written with Danny L Harle, ironically during the Dua Lipa tour—when I had never been in more of a pop atmosphere in my entire life.” **“Butterfly Net”** “‘Butterfly Net’ is maybe the most narrative storyteller moment on the whole album. And also, palette-wise, deviates from the more hybrid electronic palette that we\'ve been in to go fully into this 1960s drum reverb band atmosphere. I\'m playing an organ solo. I was listening to a lot of ’60s Italian music, and the way they use reverbs as a holder of the voice and space and very minimal arrangements to such incredible effect. It\'s set in three parts, which was somewhat inspired by this triptych of songs called ‘Chansons de Bilitis’ by Claude Debussy that I had learned to sing with my opera teacher. I really liked that structure of the finding someone falling in love, the deepening of it, and then the tragedy at the end. It uses the metaphor of the butterfly net to speak about the inability to keep memories, to keep love, to keep the feeling of someone\'s presence. The children\'s choir \[London\'s Trinity Choir\] we hear on ‘Billions’ comes in again—they get their beautiful feature at the end where their voices actually become the stand-in for the light of the world being onto me.” **“Smoke”** “It was, most importantly, the first song for the album written with a breakbeat, which inspired me to carry on down that path. It’s about catharsis. The opening line is about pretending that something isn\'t catastrophic when it obviously is. It\'s about denial. It\'s about pretending that the situation or your feelings for someone aren\'t tectonic, but of course they are. And then, of course, in the chorus, everything pours right out. But tonally it feels like I\'m at home base with ‘Smoke.’ It has links to songs like \[2019’s\] ‘Pang,’ which, for me, have this windswept feeling of being quite out of control, but are also very soulful and carried by the music. We\'re getting a much more nocturnal, clattery, chaotic picture.” **“Billions”** “‘Billions’ is last for all the same reasons that \'Welcome to My Island’ is first. It dissolves into total selflessness, whereas the album opens with total selfishness. The Beach Boys’ ‘Surf’s Up’ is one of my favorite songs of all time. I cannot listen to it without sobbing. But the nonlinear, spiritual, tumbling, open quality of that song was something that I wanted to bring into the song. But \'Billions\' is really about pure sensuality, about all agenda falling away and just the gorgeous sensuality of existing in this world that\'s so full of abundance, and so full of contradictions, humor, and eroticism. It’s a cheeky sailboat trip through all these feelings. You know that feeling of when you\'re driving a car to the beach, that first moment when you turn the corner and see the ocean spreading out in front of you? That\'s what I wanted the ending of this album to feel like: The song goes very quiet all of a sudden, and then you see the water and the children\'s choir comes in.”

For the last two decades, Sufjan Stevens’ music has taken on two distinct forms. On one end, you have the ornate, orchestral, and positively stuffed style that he’s excelled at since the conceptual fantasias of 2003’s star-making *Michigan*. On the other, there’s the sparse and close-to-the-bone narrative folk-pop songwriting that’s marked some of his most well-known singles and albums, first fully realized on the stark and revelatory *Seven Swans* from 2004. His 10th studio full-length, *Javelin*, represents the fullest and richest merging of those two approaches that Stevens has achieved to date. Even as it’s been billed as his first proper “songwriter’s album” since 2015’s autobiographical and devastating *Carrie & Lowell*, *Javelin* is a kaleidoscopic distillation of everything Stevens has achieved in his career so far, resulting in some of the most emotionally affecting and grandiose-sounding music he’s ever made. *Javelin* is Stevens’ first solo record of vocal-based music since 2020’s *The Ascension*, and it’s relatively straightforward compared to its predecessor’s complexity. Featuring contributions from vocalists and frequent collaborators like Nedelle Torrisi, adrienne maree brown, Hannah Cohen, and The National’s Bryce Dessner (who adds his guitar skills to the heart-bursting epic “Shit Talk”), the record certainly sounds like a full-group effort in opposition to the angsty isolation that streaked *The Ascension*. But at the heart of *Javelin* is Stevens’ vocals, the intimacy of which makes listeners feel as if they’re mere feet away from him. There’s callbacks to Stevens’ discography throughout, from the *Age of Adz*-esque digital dissolve that closes out “Genuflecting Ghost” to the rustic Flannery O’Connor evocations of “Everything That Rises,” recalling *Seven Swans*’ inspirational cues from the late fiction writer. Ultimately, though, *Javelin* finds Stevens emerging from the depressive cloud of *The Ascension* armed with pleas for peace and a distinct yearning to belong and be embraced—powerful messages delivered on high, from one of the 21st century’s most empathetic songwriters.

Having exorcised their fascination with post-punk on 2021’s *Drunk Tank Pink*, shame evolves on their third LP—with an expansive mix of anthems (“Fingers of Steel”), rippers (“Six-Pack,” “Different Person”), and ballads (“All the People,” the Phoebe Bridgers-featuring “Adderall”) that, like the Pixies before them, delivers the twists and abrasions of underground music with the straightforward warmth of classic rock. To note that they wrote most of it in a couple of weeks (and recorded it live in the studio) would sound like a corny bid for the scruffy vitality of rock ’n’ roll, were it not for the fact that you can tell.

shame were tourists in their own adolescence - and nothing was quite like the postcard. The freefall of their early twenties, in all its delight and disaster, was tangled up in being hailed one of post-punk’s greatest hopes. In 2018, they took their incendiary debut album Songs of Praise for a cross-continental joyride for almost 350 relentless nights. They tried to bite off more than they could chew, just to prove their teeth were sharp enough – but eventually, you’ve got to learn to spit it out. Then came the hangover. shame’s frontman, Charlie Steen, suffered a series of panic attacks which led to the tour’s cancellation. For the first time, since being plucked from the stage of The Windmill and catapulted into notoriety, shame were confronted with who they’d become on the other side of it. This era, of being forced to endure reality and the terror that comes with your own company, would form shame’s second album, 2021’s Drunk Tank Pink, the band’s reinvention. If Songs of Praise was fuelled by pint-sloshing teenage vitriol, then Drunk Tank Pink delved into a different kind of intensity. Wading into uncharted musical waters, emboldened by their wit and earned cynicism, they created something with the abandon of a band who had nothing to lose. Having forced their way through their second album’s identity crisis, they arrive, finally, at a place of hard-won maturity. Enter: Food for Worms, which Steen declares to be “the Lamborghini of shame records.” For the first time, the band are not delving inwards, but seeking to capture the world around them. “I don’t think you can be in your own head forever,” says Steen. A conversation after one of their gigs with a friend prompted a stray thought that he held onto: “It’s weird, isn’t it? Popular music is always about love, heartbreak, or yourself. There isn’t much about your mates.” In many ways, the album is an ode to friendship, and a documentation of the dynamic that only five people who have grown up together - and grown so close, against all odds - can share. The title, Food for Worms, takes on different meanings when considered with the ten vignettes the band has painted for you across the record. That spirit of interpretation, to see yourself reflected within it, is conveyed through the cover art. Designed by acclaimed artist Marcel Dzama, whose style evokes dark fairy tales and surrealism, it’s suggestive of what’s left unsaid, what lies beneath the surface. On the one hand, Food for Worms calls to mind a certain morbidity, but on the other, it’s a celebration of life; the way that, in the end, we need each other. It also strikes at the core of shame itself. Since the beginning, the band has been in the business of finding the light in uncomfortable contradictions: Steen always makes a point of taking his top off during performances as a way of tackling his body weight insecurities. Through sheer defiance, they play their vulnerabilities as strengths. Reconnecting with that ethos is what hotwired the band into making the album after a false start during the pandemic. Without pressure or an end goal - just a long expanse of time - nothing would hold. Their management then presented them with a challenge: in just under three weeks, shame would play two shows at The Windmill where they would be expected to debut two sets of entirely new songs. This opportunity meant that the band returned the same ideology which propelled them to these heights in the first place: the love of playing live, on their own terms, fed by their audience. Thus, Food for Worms careened and crashed into life faster than anything they’d created before: a weapons-grade cocktail that captured all the gristle, fragility and carnal physicality that earned shame their merits. It was only right that shame would record the album entirely live for the first time. The band recorded Food for Worms while playing festivals all over Europe, invigorated by the strength of the reaction their new material was met with. That live energy, what it’s like to witness shame in their element, is captured perfectly on record - like lightning in a bottle. They called upon renowned producer Flood (Nick Cave, U2, Foals) to execute their vision. Recording each track live meant a kind of surrender: here, the rough edges give the album its texture; the mistakes are more interesting than perfection. In a way, it harks back to the title itself and the way that with this record, the band are embracing frailty and by doing so, are tapping into a new source of bravery. It also marks a sonic departure from anything they’ve done before. shame have abandoned their post-punk beginnings for far more eclectic influences, drawing from the tense atmospherics of Merchandise, the sharp yet uncomplicated lyrical observations of Lou Reed and the more melodic works of 90s German band, Blumfeld. In the past, their music had been almost clinically assembled, with the vocals and the band existing as two distinct layers. But Food for Worms, there has never been such an immediate sense of togetherness - and more than that, it was fun. Everyone chipped in on vocals; they made the unifying choice to sing, rather than the solitude that comes with a shout. Roles were not so fiercely defined, with Steen taking command of the bass guitar for the anthemic “Adderall”, devising a simple progression that bassist Josh Finerty would never dream of, pushing the album into new, unexpected places. “Adderall” staggers, feeling the weight of its own bones, evoking a certain desperation that comes with dragging yourself through an internal fog. Steen explains: “‘Adderall’ is the observation of a person reliant on prescription drugs. These pills shift their mental and physical state and alter their behaviour; it’s about how this affects them and those around them. It’s a song of compassion, frustration and the acceptance of change. It’s partly coming to terms with the fact that sometimes your help and love can’t cure those around you but, as much as it causes exasperation, you still won’t ever stop trying to help.” The album opens with “Fingers of Steel”, which is heralded with an airy piano section that plunges into nosebleed-inducing guitars like a mutant orchestra; it was completely transformed from its folk-indebted beginnings. It delves into the cyclical nature of friendship, which the title invites you to consider. “‘Fingers of Steel’ is about helping a mate and the frustrations that come with it,” shares Steen. “It’s coming to terms with the fact that people can’t be who you want them to be and sometimes there isn’t anything you can do to help, it’s their own thing they have to work out for themselves and you have to accept that.” But it wouldn’t be shame if there wasn’t a bit of theatrical flair, signed off with a smirk. “Six Pack”, with its psychedelic wah-wah grooves and frenetic guitarwork, sees Steen act as your spirit guide into a room where, within those four walls, your wildest dreams come true: “Now you’ve got Pamela Anderson reading you a bedtime story / And every scratch card is a fucking winner!” he howls. The song is a product of lockdown-induced cabin fever, and the absurd places our mind can wander when we are confined. It’s an anthem for newfound freedom: “You’ve done time behind bars, and now you’re making time in front of them,” Steen sings, with a showman’s grandeur. It’s time to make up for everything you’ve lost or wasted - and shame wants it all. Food for Worms also sees Steen deliver one of his greatest vocal performances which came from learning to lean into the vulnerabilities his lyrics portray, rather than deflecting them. “Orchid”, opens with the easy amble of an acoustic guitar, a different sound for the band which required careful consideration for how his voice would adapt to it. His vocal teacher, Rebecca Phillips, encouraged him to approach it unflinchingly. He recalls her telling him: “Anything that you’re singing is obviously personal, but a very male tendency is to detach from it and think of the melody, instead of what you’re saying.” It was this new technique that allowed shame to embrace the songs that dealt with a deeply personal subject: fear for a friend’s mental well-being. Steen’s voice paces with sleepless worry, guilt, frustration – and absolute tenderness. Closing track “All the People”, a great musical swell of brotherly love, haunts the mind the lingering words penned by guitarist Sean Coyle-Smith: “All the people that you’re gonna meet / Don’t you throw it all away / Because you can’t love yourself.” With that weight, there is a lightness to the song which captures the spirit of Food for Worms and all the thoughts that expression evokes, all that bittersweetness. And even if you can’t put those feelings into words, shame have found them for you.

Protomartyr’s slurred ramblings and miasmic clouds of guitar have always had a touch of the apocalypse in them, or at least of the decay that might lead there. The paradox is how the Detroit band manages to make that decay sound so grand. New Wave rippers (“For Tomorrow”) and leather-jacket music (“Fun in Hi Skool”), ’50s slow dances (“Make Way”) and jock jams for the recently undead (“Polacrilex Kid”): Where some post-punk bands lean into their artiness and Eurocentrism, Protomartyr sound like Midwesterners raised on arena rock and the looming intensity of Bible stories. “Welcome to the haunted earth/The living afterlife,” Joe Casey moans at the album\'s onset. He’s grinding his teeth under the bleachers as we speak.

“I\'ve always written from a place of fiction,” Andy Shauf tells Apple Music. “When I was making \[2016’s\] *The Party*, I was going to a lot of parties. When I was writing \[2020’s\] *The Neon Skyline*, I was drinking at a bar called the Skyline. It feels now like it was a bit unimaginative, but I think I was trying to do the thing that people tell you to do, which is write what you know. I came to this realization that if I want to take a step forward, I need to write something that\'s outside of writing what I know.” Like its forebears, *Norm*, the Toronto singer-songwriter\'s eighth solo LP, takes a magnifying glass to its central character, but its stories are told through a series of narrators. That’s partly because when Shauf started writing it, there wasn’t a concept at all. “I was going to call the album *Norm*, and it was just going to be a normal album—like a normal batch of songs,” he says. But once he wrote “Telephone,” the seed for a storyline was planted. “It was about someone longing to be on the phone,” he says. “Then it flips to show the perspective of this person looking in the window while they\'re calling, and it has this stalker vibe to it. I just made a mental note that this could be a character and I could call them Norm.” With the help of a friend—Shauf writes, plays all the instruments, and records on his own—he sewed the narrative together, coloring in the detail of Norm’s increasing creepiness while constantly in God’s presence. (Shauf was raised Christian in small-town Saskatchewan, but doesn’t consider himself religious now.) “I think Norm is a pretty normal guy,” he says. “He\'s a bit of a fuck-up, and he has a side of him that\'s really disconnected from reality. And he\'s got some pretty serious problems. He\'s introduced very relatably, but at a certain point there\'s a shift that can change your perspective on everything that\'s happened before.” Here Shauf talks through how Norm’s story takes shape, track by track. **“Wasted on You”** “I was reading the Old Testament and looking for stories where I could flip the perspective so that God was narrating them, so that you heard this sort of imperfect God explaining his side of it. I was picturing this conversation between God and Jesus. My familiarity with Christianity—or just cartoon Christianity—made me feel like this was the most spoon-fed, \'Here\'s God as a narrator’ story, but I like that it\'s a little bit vague.” **“Catch Your Eye”** “This is the first introduction to Norm. We\'re in his head, and we are just getting a picture of that longing. It\'s a gentle introduction. I think by the end of the song, you\'re going to realize that something is a little bit off with what he\'s doing.” **“Telephone”** “I wrote it kind of as a joke, where it was the pandemic and I was trying to connect with someone and we were talking on the telephone a lot. And there was a lot of running out of things to talk about. I was starting to dread it. I decided I would write a song that at first seemed like I really loved the telephone, and by the end of it, it just had a lot of questions or it just turned on its side. I think you could still read that song as a love song—maybe if you aren\'t paying attention for the second half.” **“You Didn\'t See”** “I needed to have a point where the relationship between Norm and God was explained. You get a glimpse into why Norm is getting away with what he\'s doing, to a certain extent, while he\'s under the eye of God—so this is a song from God\'s perspective.” **“Paradise Cinema”** “You go from God\'s perspective of Norm standing behind a tree and God\'s just continuing to keep an eye on him to this. It\'s a lazy…maybe it\'s a Sunday afternoon stroll to the cinema—for more than one person.” **“Norm”** “Originally I wrote it about Norm standing in line to buy a sandwich, and then I realized that the story in that song sucked. But it was also because in any story involving God, I think there\'s the need for a divine intervention of sorts, or God needs to make himself known. So on one instance, he helped Norm, and on this instance, he needs to tell Norm that he\'s no longer okay with what he is doing. And at the same time, it\'s just Norm grazing around, watching some *Price Is Right*.” **“Halloween Store”** “I thought that my next record was going to be a disco record. At a certain point, I just realized that I was making—I don\'t know—like cartoon music. It was like I was becoming a caricature of myself making this weird, throwback...cartoon music is the best way I can say it. But this song, I wrote it with those songs and it\'s got this super-fast triangle and like a four-on-the-floor, dancy beat. I had the first two verses of it for a long time, and it just stuck around until I found a place for it in the Norm universe. This is the point in the story where the thing that Norm has been waiting for is finally happening, and he\'s not even sure if it\'s happening.” **“Sunset”** “It’s the furthering of the event in ‘Halloween Store’—it\'s too good to be true, and it\'s too easy. I wanted it to be so simple that you\'re wondering why it\'s even possible, or it\'s a terrible thing that\'s happening and it\'s the result of something that was not intended to be terrible or was not intended to have any weight at all, which is what happens in the next song—the flipped perspective of it.” **“Daylight Dreaming”** “This was the hardest part of the record for me. This is essentially someone just trying to play a joke on someone else, and there\'s history between these people, and there\'s a history of this joke specifically. But this time it turns into something that\'s completely unintended and gives Norm his opportunity.” **“Long Throw”** “We\'re sticking with the same perspective. I struggled with this story in how to tie it together, and I had this weird thing happen where I was watching *Mulholland Drive*, looking for some inspiration, and a certain scene in the movie froze. I watched it for about five minutes thinking that I was watching an insane creative choice, and I took a lot of meaning from it in the plot of the movie. It made me realize that this story has an ending that doesn\'t really need to be in the lyrics or in the story at all. And it\'s a very simple story, and this song is the ending of it, where the third perspective is just not getting a phone call.” **“Don\'t Let It Get to You”** “I was writing a lot with the synthesizer, and just trying to use atmosphere as much as possible. This song is a summary of the story, where there\'s a lot of chance happenings, certain decisions affecting other decisions. This is the sentiment of a cruel God just saying, \'All these things happen and you just can\'t let it get to you.\' But something that I was trying to do with this record a little bit more was to let almost an improvisation guide melodies. I would play a line and then that would be the line, instead of writing a melody. I would just play it until the moment was gone, and then I\'d recreate that and maybe harmonize to it.” **“All of My Love”** “This is kind of all three perspectives on the record. If there\'s a theme to the story, it\'s this idea of a really flawed love or a really flawed perspective of what love is or what love could be. Each of these perspectives are asking the same question. It\'s essentially the same structure as the first song, musically, but it\'s shifted to a very dark version of that. If the story of Norm is showed to you in a gradually darkening way, the music is doing the same thing—where at first, it sounds really nice, and probably by the second half of the second side, the music has also gone a bit sideways—it\'s got a sinister element to it.”

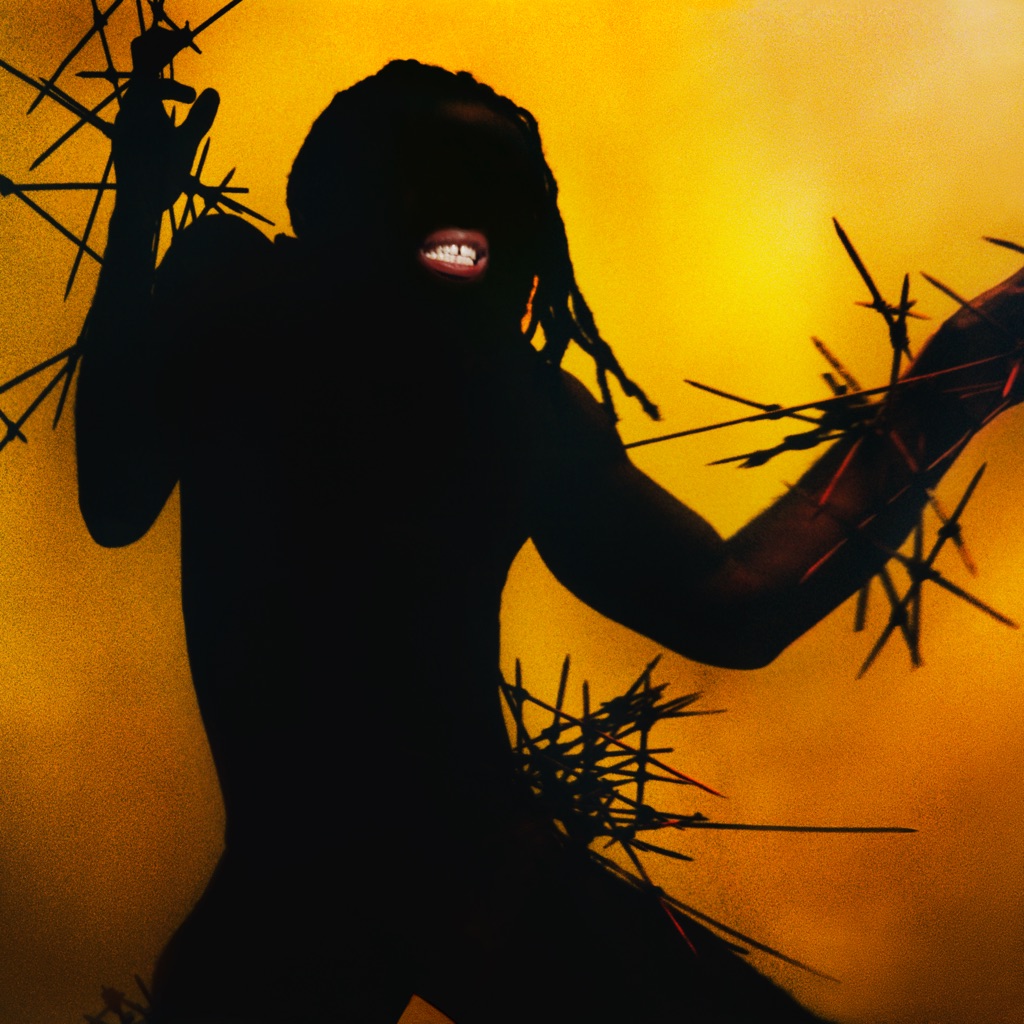

Like all great stylists, the artist born Sean Bowie has a gift for presenting sounds we know in ways we don’t. So, while the surfaces of *Praise a Lord…*, Yves Tumor’s fifth LP, might remind you of late-’90s and early-2000s electro-rock, the album’s twisting song structures and restless detail (the background panting of “God Is a Circle,” the industrial hip-hop of “Purified by the Fire,” and the houselike tilt of “Echolalia”) offer almost perpetual novelty all while staying comfortably inside the constraints of three-minute pop. Were the music more challenging, you’d call it subversive, and in the context of Bowie as a gender-nonconforming Black artist playing with white, glam-rock tropes, it is. But the real subversion is that they deliver you their weird art and it feels like pleasure.

“As I got older I learned I’m a drinker/Sometimes a drink feels like family,” Mitski confides with disarming honesty on “Bug Like an Angel,” the strummy, slow-build opening salvo from her seventh studio album that also serves as its lead single. Moments later, the song breaks open into its expansive chorus: a convergence of cooed harmonies and acoustic guitar. There’s more cracked-heart vulnerability and sonic contradiction where that came from—no surprise considering that Mitski has become one of the finest practitioners of confessional, deeply textured indie rock. Recorded between studios in Los Angeles and her recently adopted home city of Nashville, *The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We* mostly leaves behind the giddy synth-pop experiments of her last release, 2022’s *Laurel Hell*, for something more intimate and dreamlike: “Buffalo Replaced” dabbles in a domestic poetry of mosquitoes, moonlight, and “fireflies zooming through the yard like highway cars”; the swooning lullaby “Heaven,” drenched in fluttering strings and slide guitar, revels in the heady pleasures of new love. The similarly swaying “I Don’t Like My Mind” pithily explores the daily anxiety of being alive (sometimes you have to eat a whole cake just to get by). The pretty syncopations of “The Deal” build to a thrilling clatter of drums and vocals, while “When Memories Snow” ropes an entire cacophonous orchestra—French horn, woodwinds, cello—into its vivid winter metaphors, and the languid balladry of “My Love Mine All Mine” makes romantic possessiveness sound like a gift. The album’s fuzzed-up closer, “I Love Me After You,” paints a different kind of picture, either postcoital or defiantly post-relationship: “Stride through the house naked/Don’t even care that the curtains are open/Let the darkness see me… How I love me after you.” Mitski has seen the darkness, and on *The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We*, she stares right back into the void.

Young Fathers occupy a unique place in British music. The Mercury Prize-winning trio are as adept at envelope-pushing sonic experimentalism and opaque lyrical impressionism as they are at soulful pop hooks and festival-primed choruses—frequently, in the space of the same song. Coming off the back of an extended hiatus following 2018’s acclaimed *Cocoa Sugar*, the Edinburgh threesome entered their basement studio with no grand plan for their fourth studio album other than to reconnect to the creative process, and each other. Little was explicitly discussed. Instead, Alloysious Massaquoi, Kayus Bankole, and Graham “G” Hastings—all friends since their school days—intuitively reacted to a lyric, a piece of music, or a beat that one of them had conceived to create multifaceted pieces of work that, for all their complexities and contradictions, hit home with soul-lifting, often spiritual, directness. Through the joyous clatter of opener “Rice,” the electro-glam battle cry “I Saw,” the epic “Tell Somebody,” and the shape-shifting sonic explosion of closer “Be Your Lady,” Young Fathers express every peak and trough of the human condition within often-dense tapestries of sounds and words. “Each song serves an integral purpose to create something that feels cohesive,” says Bankole. “You can find joy in silence, you can find happiness in pain. You can find all these intricate feelings and diverse feelings that reflect reality in the best possible way within these songs.” Across 10 dazzling tracks, *Heavy Heavy* has all that and more, making it the band’s most fully realized and affecting work to date. Let Massaquoi and Bankole guide you through it, track by track. **“Rice”** Alloysious Massaquoi: “What we’re great at doing is attaching ourselves to what the feeling of the track is and then building from that, so the lyrics start to come from that point of view. \[On ‘Rice’\] that feeling of it being joyous was what we were connecting to. It was the feeling of fresh morning air. You’re on a journey, you’re moving towards something, it feels like you’re coming home to find it again. For me, it was finding that feeling of, ‘OK, I love music again,’ because during COVID it felt redundant to me. What mattered to me was looking after my family.” **“I Saw”** AM: “We’d been talking about Brexit, colonialism, about forgetting the contributions of other countries and nations so that was in the air. And when we attached ourselves to the feeling of the song, it had that call-to-arms feeling to it, it’s like a march.” Kayus Bankole: “It touches on Brexit, but it also touches on how effective turning a blind eye can be, that idea that there’s nothing really you can do. It’s a call to arms, but there’s also this massive question mark. I get super-buzzed by leaving question marks so you can engage in some form of conversation afterwards.” **“Drum”** AM: “It’s got that sort of gospel spiritual aspect to it. There’s an intensity in that. It’s almost like a sermon is happening.” KB: “The intensity of it is like a possession. A good, spiritual thing. For me, speaking in my native tongue \[Yoruba\] is like channeling a part of me that the Western world can’t express. I sometimes feel like the English language fails me, and in the Western world not a lot of people speak my language or understand what I’m saying, so it’s connecting to my true self and expressing myself in a true way.” **“Tell Somebody”** AM: “It was so big, so epic that we just needed to be direct. The lyrics had to be relatable. It’s about having that balance. You have to really boil it down and think, ‘What is it I’m trying to say here?’ You have 20 lines and you cut it down to just five and that’s what makes it powerful. I think it might mean something different to everyone in the group, but I know what it means to me, through my experiences, and that’s what I was channeling. The more you lean into yourself, the more relatable it is.” **“Geronimo”** AM: “It’s talking about relationships: ‘Being a son, brother, uncle, father figure/I gotta survive and provide/My mama said, “You’ll never ever please your woman/But you’ll have a good time trying.”’ It’s relatable again, but then you have this nihilistic cynicism from Graham: ‘Nobody goes anywhere really/Dressed up just to go in the dirt.’ It’s a bit nihilistic, but given the reality of the world and how things are, I think you need the balance of those things. Jump on, jump off. It’s like: *decide*. You’re either hot or you’re cold. Don’t be lukewarm. You either go for it or you don’t. Then encapsulating all that within Geronimo, this Native American hero.” **“Shoot Me Down”** AM: “‘Shoot Me Down’ is definitely steeped in humanity. You’ve got everything in there. You’ve got the insecurities, the cynicism, you’ve got the joy, the pain, the indifference. You’ve got all those things churning around in this cauldron. There’s a level of regret in there as well. Again, when you lean into yourself, it becomes more relatable to everybody else.” **“Ululation”** KB: “It’s the first time we’ve ever used anyone else on a track. A really close friend of mine, who I call a sister, called me while we were making ‘Uluation’: ‘I need a place to stay, I’m having a difficult time with my husband, I’m really angry at him…’ I said if you need a place to chill just come down to the studio and listen to us while we work but you mustn’t say a word because we’re working. We’re working on the track and she started humming in the background. Alloy picked up on it and was like, ‘Give her a mic!’ She’s singing about gratitude. In the midst of feeling very angry, feeling like shit and that life’s not fair, she still had that emotion that she can practice gratitude. I think that’s a beautiful contrast of emotions.” **“Sink Or Swim”** AM: “It says a similar thing to what we’re saying on ‘Geronimo’ but with more panache. The music has that feeling of a carousel, you’re jumping on and jumping off. If you watch Steve McQueen’s Small Axe \[film anthology\], in *Lovers Rock*, when they’re in the house party before the fire starts—this fits perfectly to that. It’s that intensity, the sweat and the smoke, but with these direct lines thrown in: ‘Oh baby, won’t you let me in?’ and ‘Don’t always have to be so deep.’ Sometimes you need a bit of directness, you need to call a spade a spade.” **“Holy Moly”** AM: “It’s a contrast between light and dark. You’re forcing two things that don’t make sense together. You have a pop song and some weird beat, and you’re forcing them to have this conversation, to do something, and then ‘Holy Moly’ comes out of that. It’s two different worlds coming together and what cements it is the lyrics.” **“Be Your Lady”** KB: “It’s the perfect loop back to the first track so you could stay in the loop of the album for decades, centuries, and millenniums and just bask in these intricate parts. ‘Be Your Lady’ is a nice wave goodbye, but it’s also radical as fuck. That last line ‘Can I take 10 pounds’ worth of loving out of the bank please?’ I’m repeating it and I’m switching the accents of it as well because I switch accents in conversation. I sometimes speak like someone who’s from Washington, D.C. \[where Bankole has previously lived\], or someone who’s lived in the Southside of Edinburgh, and I sometimes speak like someone who’s from Lagos in Nigeria.” AM: “I wasn’t convinced about that track initially. I was like, ‘What the fuck is this?’” KB: “That’s good, though. That’s the feeling that you want. That’s why I feel it’s radical. It’s something that only we can do, it comes together and it feels right.”

WIN ACCESS TO A SOUNDCHECK AND TICKETS TO A UK HEADLINE SHOW OF YOUR CHOOSING BY PRE-ORDERING* ANY ALBUM FORMAT OF 'HEAVY HEAVY' BY 6PM GMT ON TUESDAY 31ST JANUARY. PREVIOUS ORDERS WILL BE COUNTED AS ENTRIES. OPEN TO UK PURCHASES ONLY. FAQ young-fathers.com/comp/faq Young Fathers - Alloysious Massaquoi, Kayus Bankole and G. Hastings - announce details of their brand new album Heavy Heavy. Set for release on February 3rd 2023 via Ninja Tune, it’s the group’s fourth album and their first since 2018’s album Cocoa Sugar. The 10-track project signals a renewed back-to-basics approach, just the three of them in their basement studio, some equipment and microphones: everything always plugged in, everything always in reach. Alongside the announcement ‘Heavy Heavy’, Young Fathers will make their much anticipated return to stages across the UK and Europe beginning February 2023 - known for their electrifying performances, their shows are a blur of ritualistic frenzy, marking them as one of the most must-see acts operating today. The tour will include shows at the Roundhouse in London, Elysee Montmartre in Paris, Paradiso in Amsterdam, O2 Academy in Leeds and Glasgow, Olympia in Dublin, Astra in Berlin, Albert Hall in Manchester, Trix in Antwerp, Mojo Club in Hamburg and more (full dates below) To mark news of the album and the tour, Young Fathers today release a brand new single, “I Saw”. It’s the second track to be released from the album (following standalone single “Geronimo” in July) and brims with everything fans have come to love from a group known for their multi-genre versatility - kinetic rhythms, controlled chaos and unbridled soul. Accompanied by a video created by 23 year old Austrian-Nigerian artist and filmmaker David Uzochukwu, the track demonstrates the ambitious ideas that lay at the heart of this highly-anticipated record. Speaking about the title, the band write that Heavy Heavy could be a mood, or it could describe the smoothed granite of bass that supports the sound… or it could be a nod to the natural progression of boys to grown men and the inevitable toll of living, a joyous burden, relationships, family, the natural momentum of a group that has been around long enough to witness massive changes. “You let the demons out and deal with it,” reckons Kayus of the album. “Make sense of it after.” For Young Fathers, there’s no dress code required. Dancing, not moshing. Hips jerking, feet slipping, brain firing in Catherine Wheel sparks of joy and empathy. Underground but never dark. Still young, after some years, even as the heavy, heavy weight of the world seems to grow day by day.

LA-based, Dallas-raised artist Liv.e, announces her sophomore album 'Girl In The Half Pearl' due February 10th via In Real Life. 'Girl In The Half Pearl' seizes on both the creative and personal liberation Liv.e has experienced in the time since her 2020 debut album 'Couldn't Wait To Tell You...'. The album's 17 tracks are a document of self-examination, as she works through realizations prompted by grief and grapples with the dynamics of her role in the relationships in her life. Building upon the foundation she laid with CWTTY, 'Girl In The Half Pearl' bares her process of growth, forgiveness and reclamation of her sense of womanhood across an immersive soundscape. The album's artistic shifts developed during her time experimenting with live performance in London earlier this year while under residency at London's Laylow. The 24-year-old artist first garnered attention with her 2017 EP, FRANK, and 2018's Hoopdreams EP. Over the past year, Liv.e shared the standalone Mndsgn-produced single "Bout It," along with a COLORS performance and released 'CWTTY+', the deluxe version of her 2020 critically-acclaimed debut album. She's since performed alongside Earl Sweatshirt and Ravyn Lenae. Liv.e's unique sensibilities have also caught the eye of the fashion world, marked by an appearance in a Miu Miu ad campaign photographed by Tyrone Lebon. Most recently, she was featured on the new Mount Kimbie single titled "a deities encore."

Furling moves through the breadth of Meg’s musical fascinations and the environments around them—edges of memory, daydreams spanning years, loose ends, divergent paths, secret conversations under stars—all led by a stirring, singular voice calling experience and enlightenment, elation, and ecstasy into bloom.

The wistful, slightly uncertain feeling you get from a Yo La Tengo album isn’t just one of the most reliable pleasures in indie rock; it practically defines the form. Their 17th studio album was recorded nearly 40 years after husband and wife Ira Kaplan and Georgia Hubley decided that, hey, maybe they could do it, too. *This Stupid World*’s sweet ballads (“Aselestine,” “Apology Letter”) and steady, psychedelic drones (“This Stupid World,” “Sinatra Drive Breakdown”) call back to the band’s classic mid-’90s period of *Painful* and *Electr-O-Pura*, whose domestications of garage rock and Velvet Underground-style noise helped bring the punk ethic to the most bookish and unpunk among us. Confident and capable as they are, you still get the sense that they don’t totally know what they’re doing, or at least entertain enough uncertainty to keep them human—a quality that not only gives the music its lived-in greatness, but also makes them the kind of band you want to root for, which their fans do with a low-key fidelity few other bands can claim.

Coming February 10: the most live-sounding Yo La Tengo album in years, This Stupid World. Times have changed for Yo La Tengo as much as they have for everyone else. In the past, the band has often worked with outside producers and mixers. In their latest effort, the first full-length in five years, This Stupid World was created all by themselves. And their time-tested judgment is both sturdy enough to keep things to the band’s high standards, and nimble enough to make things new. At the base of nearly every track is the trio playing all at once, giving everything a right-now feel. There’s an immediacy to the music, as if the distance between the first pass and the final product has become more direct. Available on standard black vinyl, CD and on limited blue vinyl.

제가 지금 누리고 있는 것들이 언제 사라질지, 언제 사람들이 제 곁을 떠날지 항상 두렵습니다. 모든 것들이 잠깐동안 밝게 빛났다가 아무 일도 없었던 것처럼 사라지는 일종의 마법이라고 생각합니다. 2집 발매 이후 제가 꾼 꿈들을 엮어서 만든 앨범입니다. 도움을 주신 전 세계 사람들에게 감사의 말씀을 드립니다. I'm always afraid when what I have now will disappear and when people will leave me. I think these are some kind of magic, that will shine bright for a while and then lights out, like nothing happened. This is an album that I made with my dreams I dreamed after my 2nd album. Thanks to people all over the world for the help.

With A Hammer is the debut studio album by New York singer-songwriter Yaeji. “With A Hammer” was composed across a two-year period in New York, Seoul, and London, begun shortly after the release of “What We Drew” and during the lockdowns of the Coronavirus pandemic. It is a diaristic ode to self-exploration; the feeling of confronting one’s own emotions, and the transformation that is possible when we’re brave enough to do so. In this case, Yaeji examines her relationship to anger. It is a departure from her previous work, blending elements of trip-hop and rock with her familiar house-influenced style, and dealing with darker, more self-reflective lyrical themes, both in English and Korean. Yaeji also utilizes live instrumentation for the first time on this album—weaving in a patchwork ensemble of live musicians, and incorporating her own guitar playing. “With A Hammer” features electronic producers and close collaborators K Wata and Enayet, and guest vocals from London’s Loraine James and Baltimore’s Nourished by Time.

"When making this album, I wanted to do something that creatively pushed a button. Something that served a purpose while trying to understand both sides of the fence that it represents. The idea of a fictional character, Franklin Saint, and what his innermost thoughts could be when dealing with the fictional world he’s caught within. What makes it so intriguing is that his character and his world are mirrors of a time and EDA that really happened. The birth of one of the world’s most addictive drugs and how its ripple effect took on a life that may seemingly never die. The crack era was one of the worst chapters in black America’s story. Using the “Snowfall” series as a vehicle to delve into both sides was truly fascinating as an emcee. It’s a project that is layered beyond measure. If you’ve never seen Snowfall, you’ll think it’s a really great album, but if you’re an avid fan of Snowfall, you’ll truly feel as if Franklin, the conflicted boy genius turned millionaire and career criminal, truly did pick up a pen and pad to write his life story over a bed of beats. It was one of the most intense projects I’ve ever written. The idea of becoming a fictional character which represents actual real life events, making sure to hit every detail, be it from both the show and our real world, was a writing work out like no other. I’m honored to have been able to do so, and I’m honored that The Other Guys trusted me to step outside of a box and truly push the envelope with this. Enjoy, and remember, like they told us in the 80’s: just say no." -Skyzoo

Forget the mumbled vocals and air of perpetual dislocation—Archy Marshall is a traditionalist, albeit a subtle one. Like all King Krule albums, *Space Heavy* has its jagged moments (“Pink Shell,” the back half of the title track). But as a father on the cusp of 30, he seems evermore in touch with the quiet contentments that make our perceived miseries endurable: a long walk on a chilly beach, a full moon seen from a clean bed. His ballads feel like doo-wop without exactly sounding like them (“Our Vacuum”), and the broken sweetness of his guitars are both ’90s indie-rock and the sleepy jazz of an after-hours lounge (“That Is My Life, That Is Yours”). New approach, same old beauty.

“This isn’t a concept album,” Yazmin Lacey tells Apple Music. “This is a sound collage that represents where I am right now. I worked on this project for over two years. There’s more collaboration here, I’ve worked with more people compared to any other project I’ve put out. The music-making process has been similar in some ways, though. I’m a creature of comfort. If things aren’t comfortable for me, I don’t do them. So, in terms of the way we recorded, it was similar. I laid down a lot of the vocals on my own.” The East London-born singer-songwriter’s story is anything but conventional. While working blue-collar jobs for many years, hazy, fume-filled open mic nights and late bars are where Yazmin Lacey found her calling. Using the improvisation of ’40s bebop, hip-hop word spirals, and neo-soul-driven melodies, Lacey would carve out rousing performances from loose freestyles, sharing this across a debut EP, *Black Moon*, her bold introduction to the alternative jazz circuit in 2017. The following year, a second EP, *When the Sun Dips 90 Degrees*, served up genre-bending mysticism, encompassing the past and future with every groove as slow-burning cuts recalled Ella Fitzgerald, Sweetback, and early Amy Winehouse in tonality and tempo. Tapping beatsmiths David Okumu, Melo-Zed, and JD. Reid for her full-length debut LP, the album is structured just as it’s titled—a digital sketchbook with an analog feel. Recorded over a two-year span, *Voice Notes* is an expansive exploration of Yazmin’s personal and musical hallmarks. Reflecting on small-hours excursions (“Late Night People”), scenic waterfronts (“Sea Glass”), and foggy, early-morning bus rides (“Where Did You Go?”), *Voice Notes* finds Yazmin wrestling with her subconscious. “I think this album took so long to make because life just kept happening,” she says. “It’s a collection of my life.” Read on for her track-by-track guide. **“Flylo Tweet”** “This began life as an eight-and-a-half-minute freestyle, a literal stream of consciousness. As the title suggests, a legendary tweet from Flying Lotus—aka FlyLo—inspired the song. I practiced free-form writing for half an hour for this song to clear my mind. At the end of the freestyle, I talked with one of my best friends, Stella. I vividly remember telling her about this tweet I’d seen. The conversation spawned into a discussion about FlyLo’s philosophy of self-consciousness and its role as a creativity killer. I knew starting the album with eight full minutes would’ve been too much. Because of that, the final version of the song you hear is actually a conversation between me and one of the album’s producers, Zach Cayenne-Elliott, aka Melo-Zed. We’re not talking about music specifically throughout; it’s more of a window into my chaotic mind.” **“Bad Company”** “This song explores duality. \[Producer and leader of The Invisible\] Dave Okumu and I had fun with this track. This track is the spiritual successor to ‘Flylo Tweet.’ Here’s where things get introspective for me. I start to ask critical questions about myself. My demons were personified as a character called Priscilla. It’s a real self-reflective session where I wrestle with life’s ills. Priscilla’s impact is felt throughout the rest of the album too.” **“Late Night People”** “I love nocturnal things. My whole creative process for this track was inspired by the night sky, being outside, and clubbing culture. The track is really symbolic for me because I got my first gig in the smoking area of a pub. When I first started singing, I had a full-time job, so the only time I had an opportunity to make music was at night. Because the night guided so much of my early music, it also embedded itself in my creativity. This song represents all those late-night house parties, clubbing and 4 am adventures.” **“Fool’s Gold”** “This song is raw. I love it because ‘Fool’s Gold’ was a jam session that morphed into a track. This was inspired by a late-night conversation I had with a stranger at a bus stop. What’s amazing about this track is that many lyrical themes and \[the\] structure are pretty much unchanged from our jam session—there’s real beauty in that.” **“Where Did You Go?”** “This song is like a mental pit stop. ‘Flylo Tweet’ is the opener, setting up my creative process; ‘Bad Company’ deals with my inner-demon Priscilla, which leads to my decisions on ‘Late Night People.’ After burning the midnight oil, I head to my bus stop at 1 am on ‘Fool’s Gold,’ and now this track is kind of me reflecting and asking myself what’s next. I’m soul-searching.” **“Sign and Signal”** “Like the previous track, ‘Sign And Signal’ was about the changes in my life at the time. It might sound cheesy, but I was looking for clues in sentimental things, things my friends would say, or what I’d see on the street. The day I made this song, I was on the way to the studio and saw a flyer that said, ‘If you can dream it, you can believe it,’ or something along those lines. When I was in the studio, Zak already had the track demo with the switch in it. From there, I just started harmonizing with the mantra I saw on the street in the forefront of my mind. After we tweaked the track with Dave’s sauce, we went into executive-producer mode and started stitching the album together. This track really bought everything together.” **“From a Lover”** “This sits in a world I’ve never really inhabited before. When I made this record, so many things—good and bad—were happening in my life. While recording the album, I spent time with my dad and brother, sifting through their old records. I guess their records inspired how I wrote, especially their Caribbean records and vintage lovers rock. It’s real authentic.” **“Eye to Eye”** “I always try and use my voice as an instrument. ‘Eye to Eye’ is the perfect example of this. This song is sincere and vulnerable—emotionally speaking. It’s all fun and games when you’re in the studio, just spilling out your heart, but then it’s crazy to think people listen to experiences. The song is all about intimacy. It’s about connecting with someone sensually, binding the mind, body, and spirit together. The song is an ode to connectivity. My voice is real smooth and silky on this.” **“Pieces”** “This is a continuation of the previous track. It’s an open goodbye letter, probably one of the most personal tracks I’ve made. It summarizes my feelings. When dealing with a breakup, you’re all over the place. A song like ‘Pieces’ is like making sense of my thoughts. I remember going back and forth with my manager, discussing this track’s fate. After a while, something came over me and I said, ‘I have to put this out.’ It was so important to me that it eventually became *Voice Notes*’ first single.” **“Pass It Back”** “This one is really cool. I roughly talk about a particular thing in my life. It was something that I’d been carrying on my shoulders for a few years, and this track was like me finally letting go of it all.” **“Tomorrow’s Child”** “Thematically, this track is connected to ‘From a Lover.’ It was a freestyle that spawned from hearing a record in my dad’s collection. My mind had moved on from the album’s whirlwind: the emotional relationship stuff. My mind was pondering the world and everything going on right now. I’m an auntie and a godmother. Loads of my friends have children, and then you have COVID-19 in the back of everyone’s mind too. I’m not trying to say I’m some eco-warrior, but I think this song is a time lapse of the changes I’ve seen.” **“Match in my Pocket”** “This is a conversation between me and my girlfriends. We’re talking about the fact that we’re proud to be Black—it’s deep and carries a huge sense of pride. I don’t often write about things that come under the realm of politics because I write in such a borderless way. Normally, if I were tackling something socially conscious, I would feel like I’d have to think about it and structure it concisely. Luckily, everything came out naturally with this song. I hummed the bits out to Zak in a voice note before I left for London. When I got to the studio, Zak had the perfect drums, and the song came together just like that. It’s just a love letter to us. The song’s overall sentiment is that each generation will be stronger than the one that came before.” **“Legacy”** “Simply put, this one’s about my Nanny Mary—my mum’s mum. She passed away quite a long time ago, but I think the dynamics in my family are changing, and Nanny Mary is a big part of me looking back on how things used to be. My path into music was a quick left and out of the blue. I often think about where that confidence comes from, from my nan. She was very much the head of our family. I’m sad she never heard me sing, so this song’s dedicated to her. JD. Reid put the song together and helped me focus. We wrote this in one sitting.” **“Sea Glass”** “I’m a Cancerian: We love water. We’re also deep thinkers, overthinkers, deep dwellers, and storytellers. I wrote a lot of this track by the sea. I go there on my own, just randomly. I’ve been doing it for years. I just like being by the water. I voice noted a lot and listened to a lot of the album by the sea. The record starts so chaotic before it simmers down—that’s how I am. This is the culmination of everything. It’s me reflecting on my time at sea. Even though it\'s melancholic, the song has a real sense of finality. After Zak and I finished, we hugged, and it was such a special moment. This track capped off two years of recording. It’s the perfect bookend for the album.”

Yazmin Lacey is a singer-songwriter who knows something about coming into her own. She came to music late, she says – “It's never late, but late in the perspective of that I'm doing it now,” – almost as if by fate. And throughout her time in the music scene, the 33-year-old has used her music as an exercise in capturing those moments and putting them into song, as if a snapshot of the intimate parts of her own life. Debut album Voice Notes is yet another record of those moments. It follows on from three stunning EP’s; Black Moon (2017), When The Sun Dips 90 Degrees (2018) and Morning Matters (2020), a trilogy of sorts, named in part by the settings in which they were written. Voice Notes is similarly inspired by something that helped the album spring to life. A long-held tool of her music-making and way of sharing melodies with collaborators, it’s a method of communication deeply special to her. “For me, a voice note represents an immediate reaction to something,” she says. “[It’s] unfiltered and raw in the way that you can hear it. Made out of studio jam sessions alongside collaborators like Craigie Dodds, JD.REID, Melo-Zed and executive producer Dave Okumu, the recording process intentionally captured the beauty of imperfection. Lacey opted to forego a polished sound to give way for rawness, the chance to “hear someone's pauses, their stops or the cracks in their voice” much like the album’s namesake. Sonically she is uncategorisable, made up of many styles and influences. “There's lots of different flavours in there in terms of different ways I express myself,” she shares. “The things that I listen to, music that I love – it’s hard to place it. In some ways I would call it soul because that's where it comes from, my own soul. But I always avoid that; it's all perception.” She has gained support from Evening Standard, The Guardian and BBC Radio 6 Music, holds fans in the likes of Questlove and notably appeared on COLORS in 2020 with song On Your Own. But besides those wider accolades, it is the smaller, unseen parts of her life that become the story of Voice Notes, and the intimate personal observations Lacey chooses to share with listeners. “For me, it's my reactions to my lived experiences,” she says. “It's the next chapter of all I've learned musically and in life through making those three EP's, and me letting go of a lot of stuff that has happened over the last few years.” It is those experiences captured in the moment – “breakups, moving, starting again, making mistakes, losing yourself, finding yourself, and being able to tap back into the wider picture of what's important” – that come to the forefront, imperfections and all.

The music of Dylan Brady and Laura Les is what you might get if you took the trashiest tropes of early-2000s pop and slurred them together so violently it sounded almost avant-garde. It’s not that they treat their rap metal (“Dumbest Girl Alive,” “Billy Knows Jamie”), mall-punk (“Hollywood Baby”), and movie-trailer ska (“Frog on the Floor,” “I Got My Tooth Removed”) as means to a grander artistic end—if anything, *10,000 gecs* puts you in the mind of kids so excited to share their excitement that they spit out five ideas at once. And while modern listeners will be reminded of our perpetually scatterbrained digital lives, the music also calls back to the sense of novelty and goofiness that have propelled pop music since the chipmunk squeals of doo-wop and beyond. Sing it with them now: “Put emojis on my grave/I’m the dumbest girl alive.”

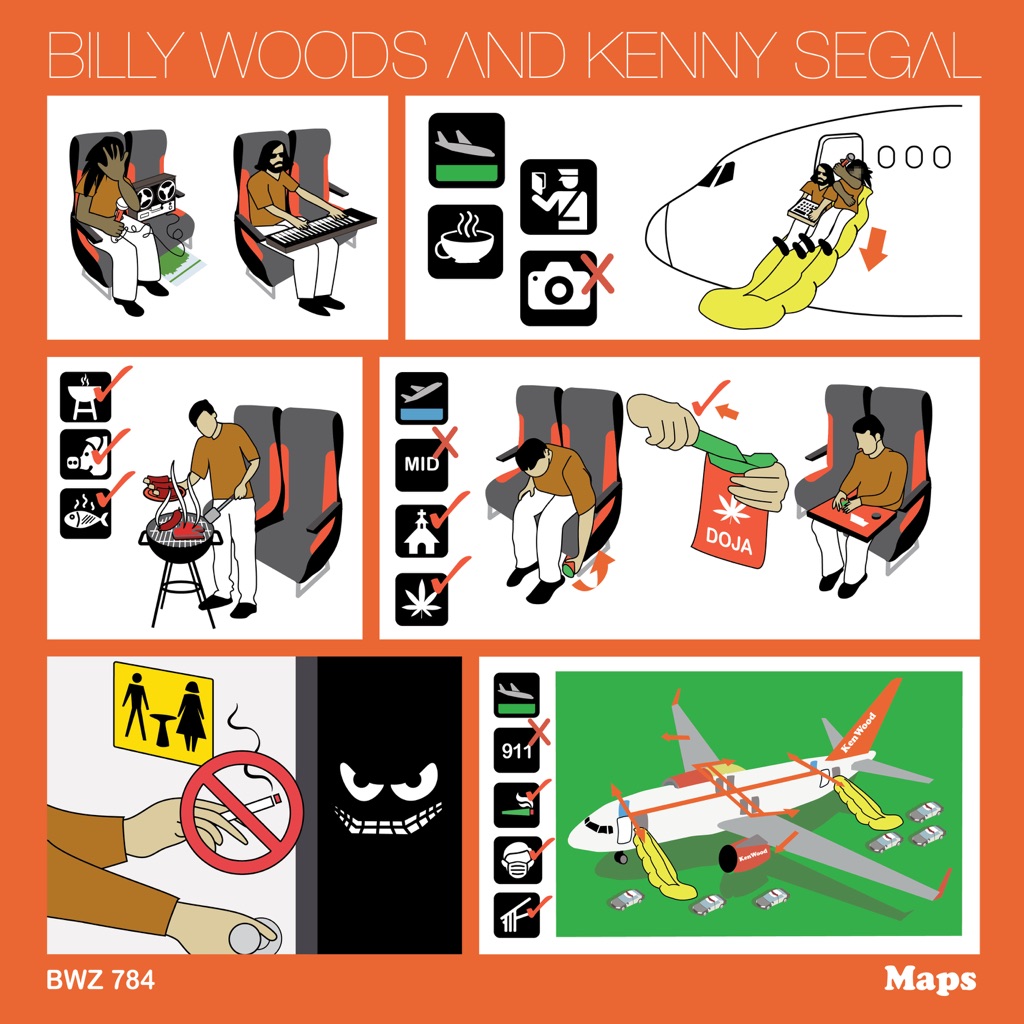

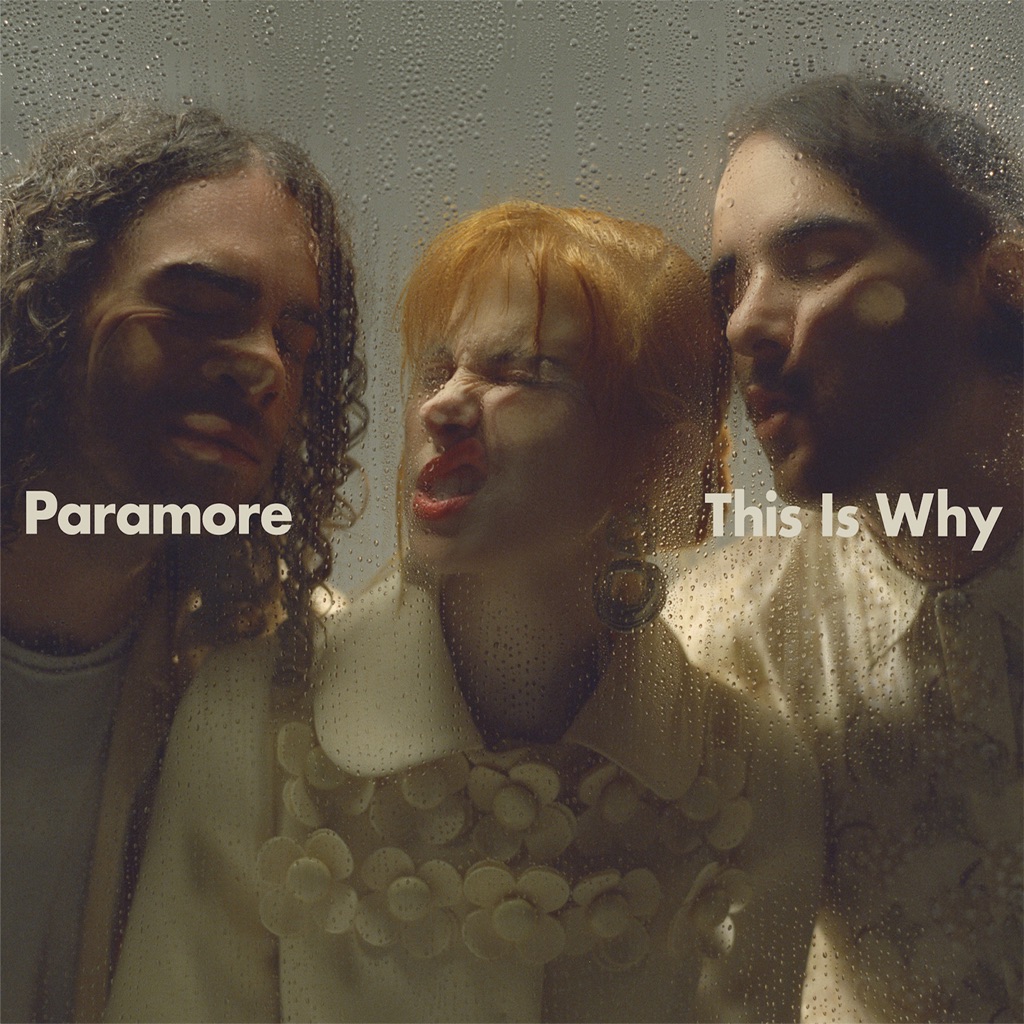

Few rock bands this side of Y2K have committed themselves to forward motion quite like Paramore. But in order to summon the aggression of their sixth full-length, the Tennessee outfit needed to look back—to draw on some of the same urgency that defined them early on, when they were teenaged upstarts slinging pop punk on the Warped Tour. “I think that\'s why this was a hard record to make,” Hayley Williams tells Apple Music of *This Is Why*. “Because how do you do that without putting the car in reverse completely?” In the neon wake of 2017’s *After Laughter*—an unabashed pop record—guitarist Taylor York says he found himself “really craving rock.” Add to that a combination of global pandemic, social unrest, apocalyptic weather, and war, and you have what feels like a suitable backdrop (if not cause) for music with edges. “I think figuring out a smarter way to make something aggressive isn\'t just turning up the distortion,” York says. “That’s where there was a lot of tension, us trying to collectively figure out what that looks like and can all three of us really get behind it and feel represented. It was really difficult sometimes, but when we listened back at the end, we were like, ‘Sick.’” What that looks like is a set of spiky but highly listenable (and often danceable) post-punk that draws influence from early-2000s revivalists like Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Bloc Party, The Rapture, Franz Ferdinand, and Hot Hot Heat. Throughout, Williams offers relatable glimpses of what it’s been like to live through the last few years, whether it’s feelings of anxiety (the title cut), outrage (“The News”), or atrophy (“C’est Comme Ça”). “I got to yell a lot on this record, and I was afraid of that, because I’ve been treating my voice so kindly and now I’m fucking smashing it to bits,” she says. “We finished the first day in the studio and listened back to the music and we were like, ‘Who is this?’ It simultaneously sounds like everything we\'ve ever loved and nothing that we\'ve ever done before ourselves. To me, that\'s always a great sign, because there\'s not many posts along the way that tell you where to go. You\'re just raw-dogging it. Into the abyss.”