Loud and Quiet's Best 40 Albums of 2019

Voted for by Loud And Quiet's contributors, these are our favourite albums released in 2019 and a reminder of what they are.

Source

Look past its futurist textures and careful obfuscations, and there’s something deeply human about FKA twigs’ 21st-century R&B. On her second full-length, the 31-year-old British singer-songwriter connects our current climate to that of Mary Magdalene, a healer whose close personal relationship with Christ brought her scorn from those who would ultimately write her story: men. “I\'m of a generation that was brought up without options in love,” she tells Apple Music. “I was told that as a woman, I should be looked after. It\'s not whether I choose somebody, but whether somebody chooses me.” Written and produced by twigs, with major contributions from Nicolas Jaar, *MAGDALENE* is a feminist meditation on the ways in which we relate to one another and ourselves—emotionally, sexually, universally—set to sounds that are at once modern and ancient. “Now it’s like, ‘Can you stand up in my holy terrain?’” she says, referencing the titular lyric from her mid-album collaboration with Future. “‘How are we going to be equals in this? Spiritually, am I growing? Do you make me want to be a better person?’ I’m definitely still figuring it out.” Here, she walks us through the album track by track. **thousand eyes** “All the songs I write are autobiographical. Anyone that\'s been in a relationship for a long time, you\'re meshed together. But unmeshing is painful, because you have the same friends or your families know each other. No matter who you are, the idea of leaving is not only a heart trauma, but it\'s also a social trauma, because all of a sudden, you don\'t all go to that pub that you went to together. The line \[\'If I walk out the door/A thousand eyes\'\] is a reference to that. At the time, I was listening to a lot of Gregorian music. I’d started really getting into medieval chords before that, and I\'d found some musicians that play medieval music and done a couple sessions with them. Even on \[2014\'s\] *LP1*, I had ‘Closer,’ which is essentially a hymn. I spent a lot of time in choir as a child and I went to Sunday school, so it’s part of who I am at this stage.” **home with you** “I find things like that interesting in the studio, just to play around and bring together two completely different genres—like Elton John chords and a hip-hop riff. That’s what ‘home with you’ was for me: It’s a ballad and it\'s sad, but then it\'s a bop as well, even though it doesn\'t quite ever give you what you need. It’s about feeling pulled in all directions: as a daughter, or as a friend, or as a girlfriend, or as a lover. Everyone wanting a piece of you, but not expressing it properly, so you feel like you\'re not meeting the mark.” **sad day** “It’s like, ‘Will you take another chance with me? Can we escape the mundane? Can we escape the cyclical motion of life and be in love together and try something that\'s dangerous and exhilarating? Yeah, I know I’ve made you sad before, but will you give me another chance?\' I wrote this song with benny blanco and Koreless. I love to set myself challenges, and it was really exciting to me, the challenge of retaining my sound while working with a really broad group of people. I was lucky working with Benny, in the fact that he creates an environment where, as an artist, you feel really comfortable to be yourself. To me, that\'s almost the old-school definition of a producer: They don\'t have to be all up in your grill, telling you what to do. They just need to lay a really beautiful, fertile soil, so that you can grow to be the best you in the moment.” **holy terrain** “I’m saying that I want to find a man that can stand up next to me, in all of my brilliance, and not feel intimidated. To me, Future’s saying, ‘Hey, I fucked up. I filled you with poison. I’ve done things to make you jealous. Can you heal me? Can you tell me how to be a better man? I need the guidance, of a woman, to show me how to do that.’ I don\'t think that there are many rappers that can go there, and just put their cards on the table like that. I didn\'t know 100%, once I met Future, that it would be right. But we spoke on the phone and I played him the album and I told him what it was about: ‘It’s a very female-positive, femme-positive record.’ And he was just like, ‘Yeah. Say no more. I\'ve got this.’ And he did. He crushed it. To have somebody who\'s got patriarchal energy come through and say that, wanting to stand up and be there for a woman, wanting to have a woman that\'s an equal—that\'s real.” **mary magdalene** “Let’s just imagine for one second: Say Jesus and Mary Magdalene are really close, they\'re together all the time. She\'s his right-hand woman, she’s his confidante, she\'s healing people with him and a mystic in her own right. So, at that point, any man and woman that are spending that much time together, they\'re likely to be what? Lovers. Okay, cool. So, if Mary had Jesus\' children, that basically debunks the whole of history. Now, I\'m not saying that happened. What I\'m saying is that the idea of people thinking that might happen is potentially really dangerous. It’s easier to call her a whore, because as soon as you call a woman a whore, it devalues her. I see her as Jesus Christ\'s equal. She’s a male projection and, I think, the beginning of the patriarchy taking control of the narrative of women. Any woman that\'s done anything can be subject to that; I’ve been subject to that. It felt like an apt time to be talking about it.” **fallen alien** “When you\'re with someone, and they\'re sleeping, and you look at them, and you just think, \'No.\' For me, it’s that line, \[\'When the lights are on, I know you/When you fall asleep, I’ll kick you down/By the way you fell, I know you/Now you’re on your knees\'\]. You\'re just so sick of somebody\'s bullshit, you\'re just taking it all day, and then you\'re in bed next to them, and you\'re just like, ‘I can\'t take this anymore.’” **mirrored heart** “People always say, ‘Whoever you\'re with, they should be a reflection of yourself.’ So, if you\'re looking at someone and you think, ‘You\'re a shitbag,’ then you have to think about why it was that person, at that time, and what\'s connecting you both. What is the reflection? For others that have found a love that is a true reflection of themselves, they just remind me that I don\'t have that, a mirrored heart.” **daybed** “Have you ever forgotten how to spell a really simple word? To me, depression\'s a bit like that: Everything\'s quite abstract, and even slightly dizzy, but not in a happy way. It\'s like a very slow circus. Suddenly the fruit flies seem friendly, everything in the room just starts having a different meaning and you even have a different relationship with the way the sofa cushions smell. \[Masturbation\] is something to raise your endorphins, isn\'t it? It’s either that or try and go to the gym, or try and eat something good. You almost can\'t put it into words, but we\'ve all been there. I sing, \'Active are my fingers/Faux, my cunnilingus\': You\'re imagining someone going down on you, but they\'re actually not. You open your eyes, and you\'re just there, still on your sofa, still watching daytime TV.” **cellophane** “It\'s just raw, isn\'t it? It didn\'t need a thing. The vocal take that\'s on the record is the demo take. I had a Lyft arrive outside the studio and I’d just started playing the piano chords. I was like, ‘Hey, can you just give me like 20, 25 minutes?’ And I recorded it as is. I remember feeling like I wanted to cry, but I just didn\'t feel like it was that suitable to cry at a studio session. I often want everything to be really intricate and gilded, and I want to chip away at everything, and sculpt it, and mold it, and add layers. The thing I\'ve learned on *MAGDALENE* is that you don\'t need to do that all the time, and just because you can do something, it doesn\'t mean you should. That\'s been a real growing experience for me—as a musician, as a producer, as a singer, even as a dancer. Something in its most simple form is beautiful.”

In some ways, Aldous Harding’s third album, *Designer*, feels lighter than her first two—particularly 2017’s stunning, stripped-back, despairing *Party*. “I felt freed up,” Harding (whose real name is Hannah) tells Apple Music. “I could feel a loosening of tension, a different way of expressing my thought processes. There was a joyful loosening in an unapologetic way. I didn’t try to fight that.” Where *Party* kept the New Zealand singer-songwriter\'s voice almost constantly exposed and bare, here there’s more going on: a greater variety of instruments (especially percussion), bigger rhythms, additional vocals that add harmonies and echoes to her chameleonic voice, which flips between breathy baritone and wispy falsetto. “I wanted to show that there are lots of ways to work with space, lots of ways you can be serious,” she says. “You don’t have to be serious to be serious. I’m not a role model, that’s just how I felt. It’s a light, unapologetic approach based on what I have and what I know and what I think I know.” Harding attributes this broader musical palette to the many places and settings in which the album was written, including on tour. “It’s an incredibly diverse record, but it somehow feels part of the same brand,” she says. “They were all written at very different times and in very different surroundings, but maybe that’s what makes it feel complete.” The bare, devastating “Heaven Is Empty” came together on a long train ride and “The Barrel” on a bike ride, while intimate album closer “Pilot” took all of ten minutes to compose. “It was stream of consciousness, and I don’t usually write like that,” she says. “Once I’d written it all down, I think I made one or two changes to the last verse, but other than that, I did not edit that stream of consciousness at all.” The piano line that anchors “Damn” is rudimentary, for good reason: “I’m terrible at piano,” she says. “But it was an experiment, too. I’m aware that it’s simple and long, and when you stretch out simple it can be boring. It may be one of the songs people skip over, but that’s what I wanted to do.” The track is, as she says, a “very honest self-portrait about the woman who, I expect, can be quite difficult to love at times. But there’s a lot of humor in it—to me, anyway.”

Aldous Harding’s third album, Designer is released on 26th April and finds the New Zealander hitting her creative stride. After the sleeper success of Party (internationally lauded and crowned Rough Trade Shop’s Album of 2017), Harding came off a 200-date tour last summer and went straight into the studio with a collection of songs written on the road. Reuniting with John Parish, producer of Party, Harding spent 15 days recording and 10 days mixing at Rockfield Studios, Monmouth and Bristol’s J&J Studio and Playpen. From the bold strokes of opening track ‘Fixture Picture’, there is an overriding sense of an artist confident in their work, with contributions from Huw Evans (H. Hawkline), Stephen Black (Sweet Baboo), drummer Gwion Llewelyn and violinist Clare Mactaggart broadening and complimenting Harding’s rich and timeless songwriting.

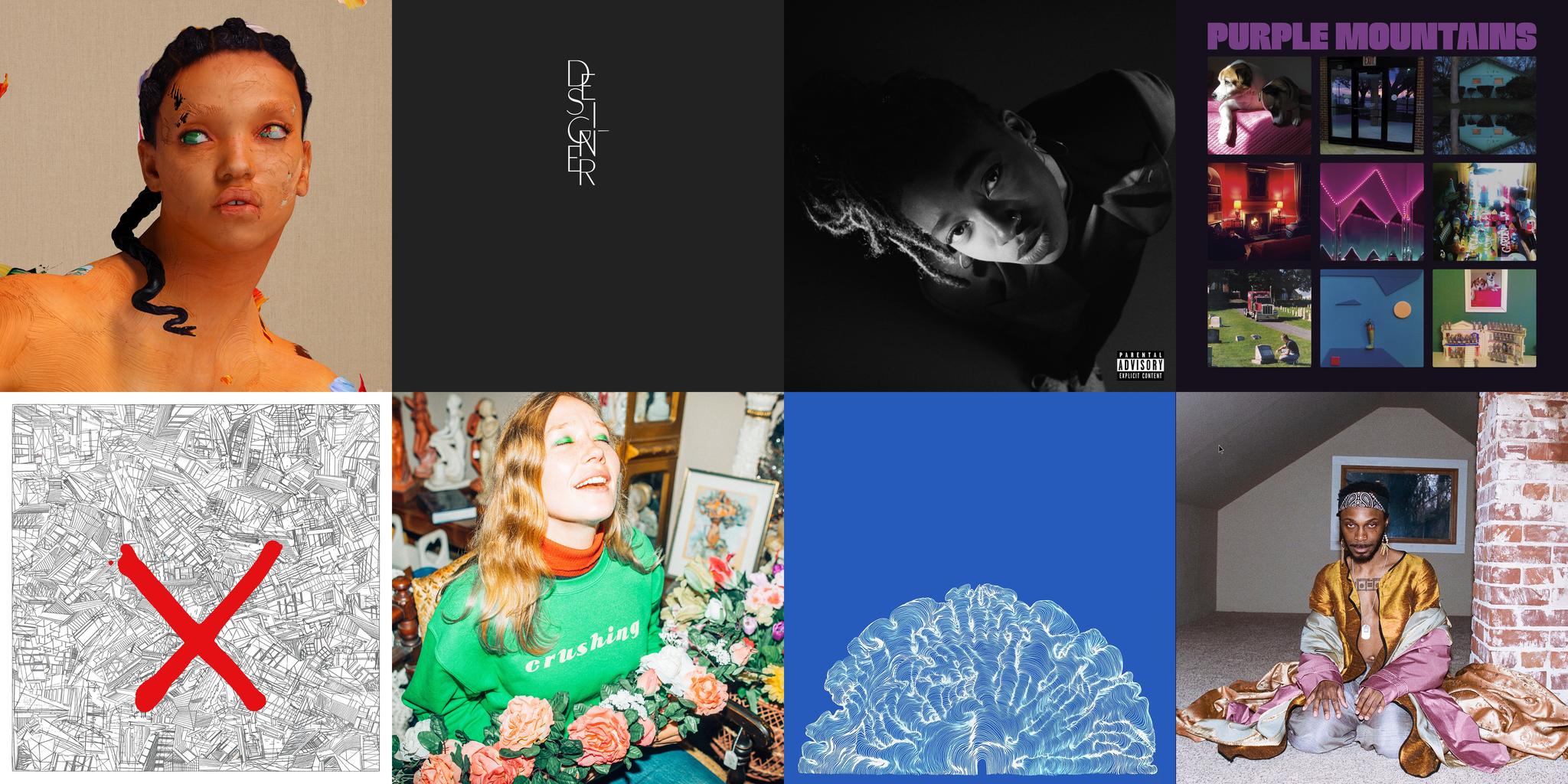

When David Berman disbanded Silver Jews in 2009, the world stood to lose one of the best writers in indie rock, a guy who catalogued the magic and misery of everyday life with wit, heart, and the ragged glory of the occupationally down-and-out. After a 10-year break professedly spent reading books and arguing with people on Reddit, Berman enlisted members of the Brooklyn band Woods to back him on *Purple Mountains*. Berman’s pain had never been laid quite so bare, nor had it ever sounded quite so urgent. “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion,” he sings on the swaggering “That’s Just the Way I Feel.” “Day to day, I’m neck and neck with giving in.” And “Margaritas at the Mall” turns an ordinary happy hour into a jeremiad about the cold comforts of capitalism in a godless world. That the music—country-tinged indie rock—was as polished and competent as it was only highlighted Berman’s intensity: less a rock singer than a street preacher, someone who needed to avail himself of his visions stat. But even at his most desperate, he remained achingly funny, turning statements of existential loneliness into the kind of bumper sticker Zen that made him seem like an ordinary guy no matter how highfalutin he could get. “Well, if no one’s fond of fuckin’ me, maybe no one’s fuckin’ fond of me,” he sings on the album-closing “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” sounding not all that far off from the George Strait one-twos he reportedly loved. Above all, though, his writing is beautiful, attuned to detail in ways that make ordinary scenarios shimmer with quiet magic. Just listen to “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan,” which turns a quiet night in a big city into an allegory of finding solace in the weather of what comes to us. Shortly after the release of *Purple Mountains*, Berman died, at the age of 52, a tragic end to what felt like a triumphant return. “The dead know what they\'re doing when they leave this world behind,” he sings on “Nights That Won’t Happen.” “When the here and the hereafter momentarily align.”

David Berman comes in from the cold after ten long years. His new musical expression is a meltdown unparalleled in modern memory. He warns us that his findings might be candid, but as long as his punishment comes in such bite-sized delights of all-American jukebox fare, we'll hike the Purple Mountains with pleasure forever.

2020 is the sixth solo album from Richard Dawson, the black-humoured bard of Newcastle. The album is an utterly contemporary state-of-the-nation study that uncovers a tumultuous and bleak time. Here is an island country in a state of flux; a society on the edge of mental meltdown.

On the auspicious occasion of the release of his mystical seventh artist album, technological force-of-nature Leafcutter John teams up with fellow stalwarts of idiosyncratic electronica Border Community to gift unto the world the small-yet-perfectly-formed joyously utopian artefact ‘Yes! Come Parade With Us’. Weaving field recordings from the Norfolk coastline together with layers of lyrical modular synth, these seven bright-eyed folk anthems sing with positivity and a sense of place, and feel right at home amongst the British label’s unparalleled ever-pastoral and often organic electronic legacy. During the summer of 2017 exiled Yorkshireman Leafcutter John returned to his one-time home of Norfolk (having graduated in Painting from Norwich’s School of Art and Design back in 1998) and set out on foot along the sixty mile section of Norfolk Coast Path which runs from Hunstanton to Overstrand, trusty audio recording device in his pocket. “And very soon the physical act of walking began to make me think about music,” he explains. “My footsteps dictated the tempo and imagined melodies accompanied me as I slowly moved along the increasingly wild and magical stretch of coastline. Stresses of the city were replaced by the fall and rise of the North Sea and endless salt flats. Sounds from the environment filtered in and I would stop often to record what I was hearing around me.” Back home in London, the hours of amassed field recordings would form the backbone and inspiration for a whole album worth of outpourings from John’s six-years-in-the-making modular synth. From the evocative sound of sea birds on ‘Pillar’ and ‘Stepper Motor’ to the colourful conversation from a country pub in ‘This Way Out’, the apposite selection of samples which made the final edit provide the perfect jumping-off point for John’s synths to soar with abandon, at times uplifting, frenetic, haunting, hypnotic or meditative, but always atmospheric and with unstoppable propulsion. “Above all else, I wanted the album to exude a sense of constant forward motion but at a very human scale,” says John. Thus drummer friends Tom Skinner (Hello Skinny) and Sebastian Rochford (long-time collaborator in the twice Mercury Prize-nominated band Polar Bear) were roped in to lend their suitably clattering human momentum, on ‘Doing The Beeston Bump’ and ‘Dunes’ respectively. Working in tempos to match his walking speed throughout – “whether trudging along a rainy shingle beach or running up wildflowering clifftop paths” – ‘Yes! Come Parade With Us’ is perfect traveling music, and once unleashed upon the world is sure to provide the soundtrack to plenty more journeys to come. Beginning his own musical journey back in 1999 on Mike Paradinas’ Planet Mu Records and with a widely-varied twenty year career in electronic music already under his belt, the release of his masterful seventh album sees Leafcutter John on career-defining form. An intensely personal project, John has also hand-drawn the labyrinthine album art and animated his own suitably exuberant rainbow-hued video to accompany the boundless enthusiasm of restorative title track Yes! Come Parade With Us. The resultant album gem is both assuredly successful in his stated aim of capturing “both the rugged beauty of the environment and the positivity I felt walking through it” and incredibly infectious, with a harmonious utopian outlook which cannot help but rub off on the listener. An electronics master of both modular synth and Max/MSP who over the years has self-assembled quite the collection of bespoke controllers for his musical performances, the centrepiece of John’s current live show is an arresting light-activated interface which enables a torch-controlled live performance like no other. Leafcutter John will be taking this and other handmade technological wizardry out on the road this Spring across the UK and beyond, including a fitting early album showcase on 16th March at the Norfolk Wildlife Trust centre in Cley Marshes, which sits around the mid-point of that fateful walk of 2017. The CD version of ‘Yes! Come Parade With Us’ comes with a map insert hand-drawn by John, and is limited to 1000 copies.

Calling an album *All My Heroes Are Cornballs* reads immediately as a brilliant indictment of celebrity culture, but what about when said whistleblower exists—to a steadily increasing number of fans—as a hero himself? “Some people *might* see me as a hero, and I *might* be a cornball to some people,” JPEGMAFIA tells Apple Music. “It can be turned on the person who created it. I’m not infallible or trying to say I\'m not a cornball. I\'m just saying, *all my heroes are cornballs*.” The album and declaration come just a year after *Veteran*, the project that brought the Brooklyn-born Baltimore MC and producer his most visibility. So what does Peggy do with all of the eyes and ears he now has at his disposal? The same thing he’s done from the beginning of his music-making career: tell people about themselves, whether they’re ready to hear it or not. Read on as JPEGMAFIA talks Apple Music through some of *All My Heroes Are Cornballs*\' more provocative selections. **“Beta Male Strategies”** “Going back to the title \[of the album\], I\'m letting you know off the bat, I\'m a false prophet. Don\'t get your hopes up, because everybody\'s human. I might put a MAGA hat on one day. It\'s unlikely, but you don\'t know, so it\'s just like, \'I\'m a false prophet/Bringin’ white folks this new religion/My fans need new addictions.’ It\'s not like I\'m the first artist to struggle with notoriety or anything like that. I\'m just framing it through my lens. I\'ve been underground and poor for years, so this is hilarious to me.\" **“Grimy Waifu”** \"‘Grimy Waifu’ is actually about a gun. They probably changed it now because the times are different, but \[when I was in the military\] they framed it like, ‘This is your gun. This is your girl. You gotta sleep with her…’ In the female squad, they probably did the opposite: ‘This is your n\*gga. Bring your n\*gga to bed.’ It\'s framed like it\'s a love song, but it\'s a song about me and my rifle.” **“PRONE!”** “The intention behind ‘PRONE!’ was to make a punk song with no instruments. This is a song that\'s made completely digitally. I feel like people in other genres, specifically rock—I go back to rock a lot because rock spends a lot of time trashing rap—a lot of people in rock had this idea that rappers aren\'t talented. In my opinion, we\'re fucking better than them. We\'re better writers, we think deeper, our concepts are harder—rap evolves faster and at a higher rate than any other genre. The only difference is rap has a bunch of n\*ggas doing it and rock has a bunch of white boys doing it. I made this song just to be like, \'I can do what you do and I don\'t even have to learn how to play drums. I\'m in here playing with my hands, bitch! And I can still do this shit.\'” **“All My Heroes Are Cornballs”** “Structurally it makes no sense, but thematically it’s the most straightforward song on here: rapping about the idea that the people we’re supposed to look up to are corny as shit. I feel like this one sums up everything, because I’m not doing anything weird vocally, I’m singing and then I’m rapping, but the execution of it doesn’t make sense: It starts off one way and I’m singing, and there’s like a long-ass hook where I don’t actually say anything and then there’s like a verse, and then the other hook that comes in is different, and then the end is like my homie ordering a bacon smokehouse meal. I came very close to cutting it, actually.” **“Thot Tactics”** “I actually wrote the rap first and that melody I had, and when I was writing the song, I would hum that melody over the part where it is now, and in the back of my head I told myself I’m gonna write something to that later, but I just sat down one day and I was like, nah, n\*gga, this is it! This is the song. I can’t hire En Vogue to do this, I gotta do it myself. I’m a DIY n\*gga. I want some shit done, I do it my muthafuckin’ self!” **“BasicBitchTearGas”** “I always told myself that one day I’d do a cover of ‘No Scrubs,’ and I just wanted to make that a reality. Bucket-list-type shit. I love this song, man. It’s one of the best songs ever written. And I really like recontextualizing songs that mean a lot to people, like pop music, because it exposes the reality of these songs. That these songs are *excellent*—regardless of how popular they are and regardless of the narrative that’s been built around some of these songs, these are excellently written, beautiful songs, and I wanna take time to appreciate them.” **“Papi I Missed U”** “I wanted to put something on record that was completely, exactly how the fuck I felt. There was no trolling, this is how I feel. And I want people to hear that and I want people to know that there\'s no fucking answer \[for it\]. I don\'t like you and there\'s nothing you can do about it. That\'s how they made my black ass feel for my whole fucking life. So when I say some shit like \'I hate old white n\*ggas, I\'m prejudiced…\' What now? I said it, I meant it, it is what it is. They don\'t give a fuck about our feelings, I don\'t give a fuck about theirs. It\'s returning all the shit they always give to me and give to black people. All this shit these racist types give to people of color, I\'m giving it right back to them and I\'m watching them scatter because they can\'t fucking take it.”

All tracks produced, written, mixed and mastered by JPEGMAFIA "Rap Grow Old & Die" contains additional production from Vegyn Album Artwork Design by Alec Marchant Recorded alone @ a space for me This album is really a thank you to my fans tbh. I started and finished it In 2018, mixed and mastered it in 2019 right after the Vince tour. I don’t usually work on something right after I release a project. But Veteran was the first time in my life I worked hard on something, and it was reciprocated back to me. So I wanted thank my people. And make an album that I put my my whole body into, as in all of me. All sides of Me baby. Not just a few. This the most ME album I’ve ever made in my life, Im trying to give y’all niggas a warm album you can live in and take a nap in maybe start a family and buy some Apple Jacks to. I’ve removed restrictions from my head and freed myself of doubt musically. I would have removed half this shit before but naw fuck it. Y’all catching every bit of this basic bitch tear gas. This is me, all me, in full form nigga, and this formless piece of audio is my punk musical . I hope it disappoints every last one of u. 💕💕

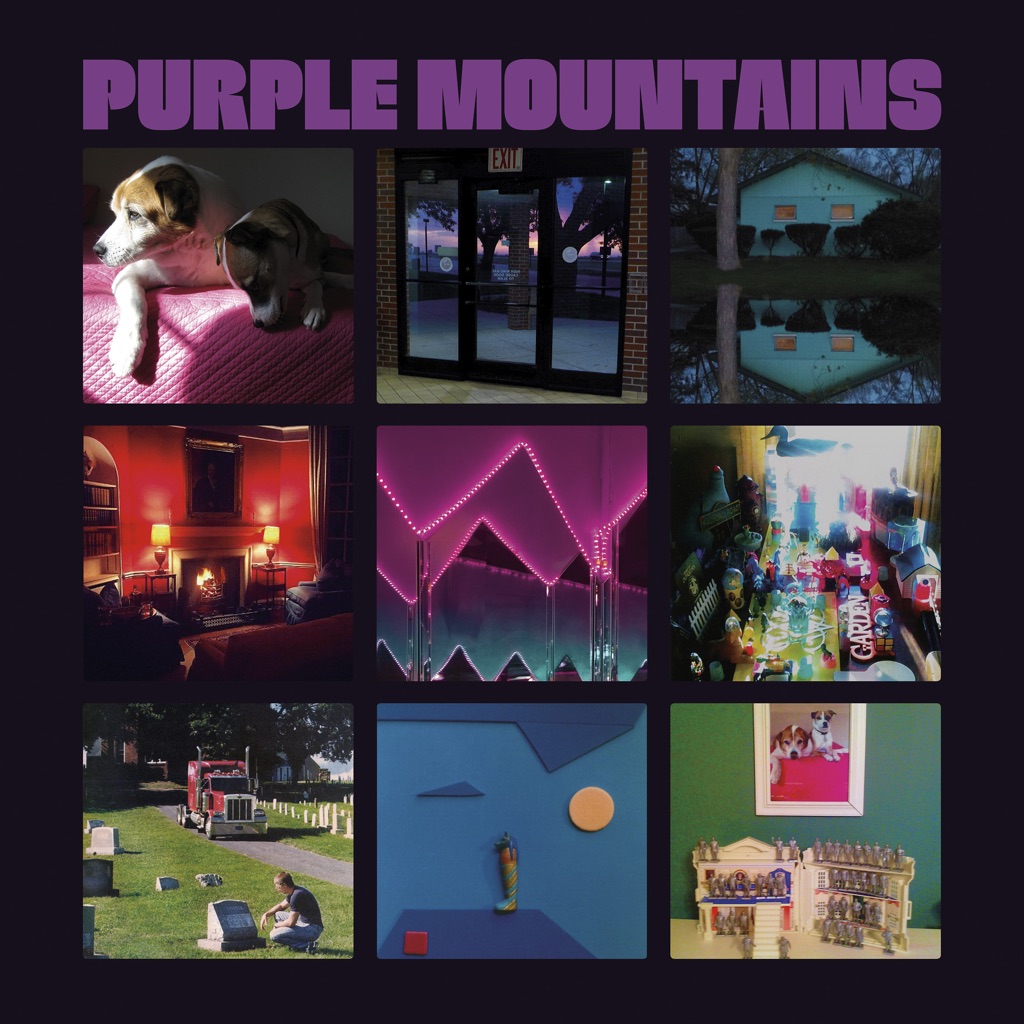

Sam Shepherd aka Floating Points has announced his new album Crush will be released on 18 October on Ninja Tune. Along with the announcement he has shared new track 'Last Bloom' along with accompanying video by Hamill Industries and announced details of a new live show with dates including London's Printworks, his biggest headline live show to date. The best musical mavericks never sit still for long. They mutate and morph into new shapes, refusing to be boxed in. Floating Points has so many guises that it’s not easy to pin him down. There’s the composer whose 2015 debut album Elaenia was met with rave reviews – including being named Pitchfork’s ‘Best New Music’ and Resident Advisor’s ‘Album of the Year’ – and took him from dancefloors to festival stages worldwide. The curator whose record labels have brought soulful new sounds into the club, and, on his esteemed imprint Melodies International, reinstated old ones. The classicist, the disco guy that makes machine music, the digger always searching for untapped gems to re-release. And then there’s the DJ whose liberal approach to genre saw him once drop a 20-minute instrumental by spiritual saxophonist Pharoah Sanders in Berghain. Fresh from the release earlier this year of his compilation of lambent, analogous ambient and atmospheric music for the esteemed Late Night Tales compilation series, Floating Points’ first album in four years, Crush, twists whatever you think you know about him on its head again. A tempestuous blast of electronic experimentalism whose title alludes to the pressure-cooker of the current environment we find ourselves in. As a result, Shepherd has made some of his heaviest, most propulsive tracks yet, nodding to the UK bass scene he emerged from in the late 2000s, such as the dystopian low-end bounce of previously shared striking lead single ‘LesAlpx’ (Pitchfork’s ‘Best New Track’), but there are also some of his most expressive songs on Crush: his signature melancholia is there in the album’s sublime mellower moments or in the Buchla synthesizer, whose eerie modulation haunts the album. Whereas Elaenia was a five-year process, Crush was made during an intense five-week period, inspired by the invigorating improvisation of his shows supporting The xx in 2017. He had just finished touring with his own live ensemble, culminating in a Coachella appearance, when he suddenly became a one-man band, just him and his trusty Buchla opening up for half an hour every night. He thought what he’d come out with would "be really melodic and slow- building" to suit the mood of the headliners, but what he ended up playing was "some of the most obtuse and aggressive music I've ever made, in front of 20,000 people every night," he says. "It was liberating." His new album feels similarly instantaneous – and vital. It’s the sound of the many sides of Floating Points finally fusing together. It draws from the "explosive" moments during his sets, the moments that usually occur when he throws together unexpected genres, for the very simple reason that he gets excited about wanting to "hear this record, really loud, now!" and then puts the needle on. It’s "just like what happens when you’re at home playing music with your friends and it's going all over the place," he says. Today's newly announced live solo shows capture that energy too, so that the audience can see that what they’re watching isn’t just someone pressing play. Once again Shepherd has teamed up with Hamill Industries, the duo who brought their ground-breaking reactive laser technologies to his previous tours. Their vision is to create a constant dialogue between the music and the visuals. This time their visuals will zoom in on the natural world, where landscapes are responsive to the music and flowers or rainbow swirls of bubbles might move and morph to the kick of the bass drum. What you see on the screen behind Shepherd might "look like a cosmos of colour going on," says Shepherd, "but it’s actually a tiny bubble with a macro lens on it being moved by frequencies by my Buchla," which was also the process by which the LP artwork was made." It means, he adds, "putting a lot of Fairy Liquid on our tour rider".

The title of this group’s second album may suggest a mystical journey, but what you hear across these nine tracks is a thrilling and direct collaboration that speaks to the mastery of the individual members: London jazz supremo Shabaka Hutchings delivers commanding saxophone parts, keyboardist Dan Leavers supplies immersive electronic textures, and drummer Max Hallett provides a welter of galvanizing rhythms. The trio records under pseudonyms—“King Shabaka,” “Danalogue,” and “Betamax” respectively—and that fantastical edge is also part of their music, which looks to update the cosmic jazz legacy of 1970s outliers such as Alice Coltrane and Sun Ra. With the only vocals a spoken-word poem on the grinding “Blood of the Past,” the lead is easily taken by Hutchings’ urgent riffs. Tracks such as “Summon the Fire” have a delirious velocity that builds and peaks repeatedly, while the skittering beat on “Super Zodiac” imports the production techniques of Britain’s grime scene. There’s a science-fiction sheen to slower jams like “Astral Flying,” which makes sense—this is evocative time-travel music, after all. Even as you pick out the reference points, which also include drum \'n\' bass and psychedelic rock, they all interlock to chart a sound for the future.

London-based composer Anna Meredith loves a corkscrew spiral, a manic grid, and key changes that lurch between nausea and pleasure. Few songs on her second album, *Fibs*, end where they start—“Sawbones” traverses precipitous bass, chiptune reverie, and a symphony in hyperdrive—yet her classical grounding ensures a keen eye on the dynamic sweep. An opening half of screaming crescendos (“Calion”) and regal pomp (“Killjoy”) begets a reprieve of power pop (“Limpet”) and girlish dreaminess (“Ribbons”)—only to end with a bang with “Paramour,” a song that makes “Sawbones” sound like Debussy’s “Clair de Lune.”

The eagerly anticipated second studio album, FIBS, is out now via Moshi Moshi/Black Prince Fury. Arriving three and a half years on from the release of her Scottish Album of the Year Award-winning debut studio album Varmints, FIBS is 45 minutes of technicolour maximalism, almost perpetual rhythmic reinvention, and boasts a visceral richness and unparalleled accessibility. FIBS is no “Varmints Part 2” — the retreading of old ground, or even a smooth progression from one project to another, just isn’t Meredith’s style. Instead, if anything, it’s “Varmints 2.0”, an overhauled and updated version of the composer’s soundworld, involving, in places, a literal retooling that has seen Meredith chuck out her old MIDI patches and combine her unique compositional voice with brand-new instruments, both acoustic and electronic, and a writing process that’s more intense than she’s ever known. Despite Meredith’s background and skills these tracks are no academic exercise, the world of FIBS is at both overwhelming and intimate, a journey of intense energy and joyful irreverence. FIBS, says Meredith, are “lies — but nice friendly lies, little stories and constructions and daydreams and narratives that you make for yourself or you tell yourself”. Entirely internally generated and perfectly balanced, they can be a source of comfort and excitement, intrigue and endless entertainment. The eleven fibs contained on Anna Meredith’s second record will do all that, and more besides.

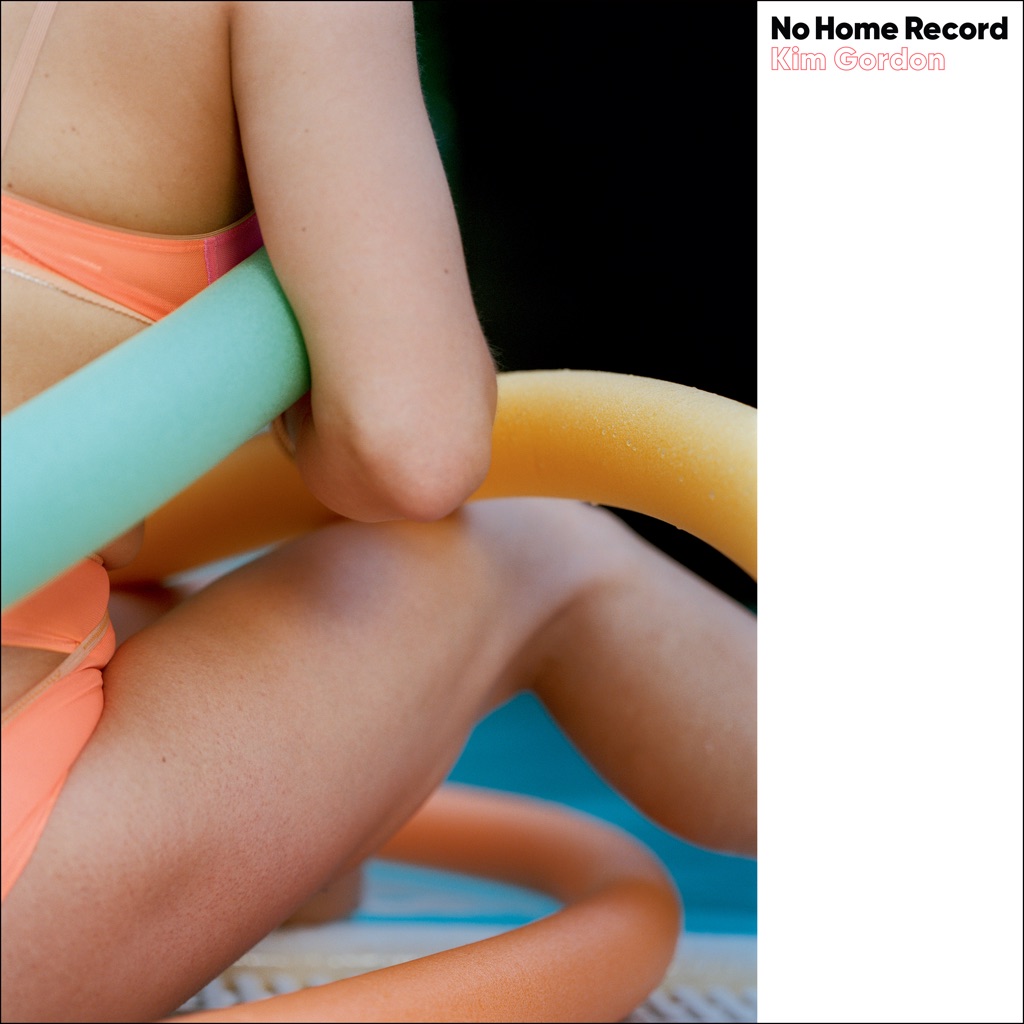

You’d think that an artist making her first solo album after nearly 40 years of collaborative work would fall for at least a few pitfalls of sentimentality—the glance in the rearview, the meditation on middle age, the warmth of accomplishment, whatever. Then again, Kim Gordon was never much for soft landings. Noisy, vibrant, and alive with the kind of fragmented poetry that made her presence in Sonic Youth so special, *No Home Record* feels, above all, like a debut—a new voice clocking in for the first time, testing waters, stretching her capacity. The wit is classic (“Airbnb/Could set me free!” she wails on “Air BnB,” channeling the misplaced passions of understimulated yuppies worldwide), as is the vacant sex appeal (“Touch your nipple/You’re so fine!” she wails on “Hungry Baby,” channeling the…misplaced passions of understimulated yuppies worldwide). Most surprising is how informed the album is by electronic music (“Don’t Play It”) and hip-hop (“Paprika Pony,” “Sketch Artist”)—a shift that breaks with the free-rock-saviordom that Sonic Youth always represented while maintaining the continuity of experimentation that made Gordon a pioneer in the first place.

With a career spanning nearly four decades, Kim Gordon is one of the most prolific and visionary artists working today. A co-founder of the legendary Sonic Youth, Gordon has performed all over the world, collaborating with many of music’s most exciting figures including Tony Conrad, Ikue Mori, Julie Cafritz and Stephen Malkmus. Most recently, Gordon has been hitting the road with Body/Head, her spellbinding partnership with artist and musician Bill Nace. Despite the exhaustive nature of her résumé, the most reliable aspect of Gordon’s music may be its resistance to formula. Songs discover themselves as they unspool, each one performing a test of the medium’s possibilities and limits. Her command is astonishing, but Gordon’s artistic curiosity remains the guiding force behind her music. It makes sense that this “American idea” (as Gordon says on the agitated rock track “Air BnB”) of purchasing utopia permeates the record, as no place is this phenomenon more apparent than Los Angeles, where Gordon was born and recently returned to after several lifetimes on the east coast. It was a move precipitated by a number of seismic shifts in her personal life and undoubtedly plays a role in No Home Record’s fascination with transience. The album opens with the restless “Sketch Artist,” where Gordon sings about “dreaming in a tent” as the music shutters and skips like scenery through a car window. “Even Earthquake,” perhaps the record’s most straightforward track embodies this mood; Gordon’s voice wavering like watercolor: “If I could cry and shake for you / I’d lay awake for you / I got sand in my heart for you,” guitar strokes blending into one another as they bleed out across an unstable page. Front to back, No Home Record is an expert operation in the uncanny. You don’t simply listen to Gordon’s music; you experience it.

Order: North America (Telephone Explosion): telephoneexplosion.bandcamp.com/album/beneath-the-floors Abroad (Tin Angel Records): tinangelrecords.bandcamp.com/alb…/beneath-the-floors

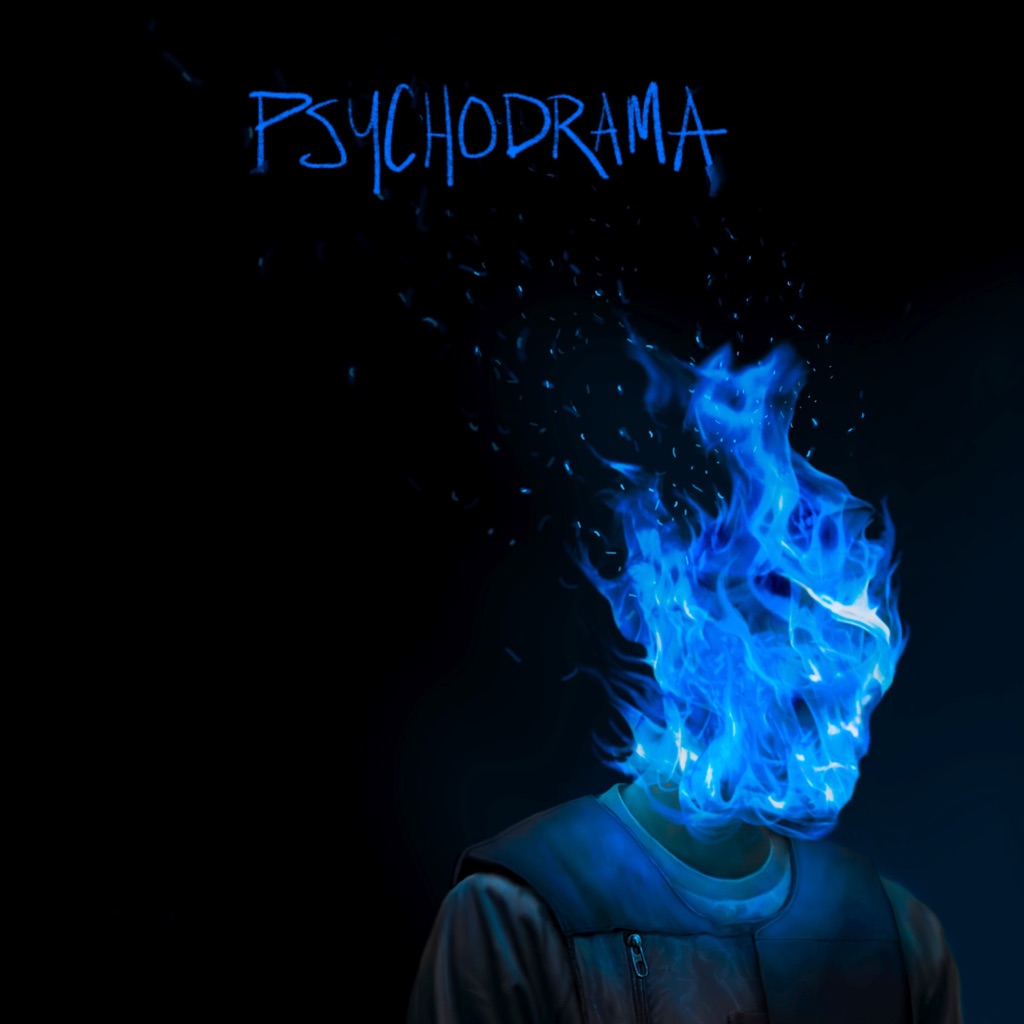

The more music Dave makes, the more out of step his prosaic stage name seems. The richness and daring of his songwriting has already been granted an Ivor Novello Award—for “Question Time,” 2017’s searing address to British politicians—and on his debut album he gets deeper, bolder, and more ambitious. Pitched as excerpts from a year-long course of therapy, these 11 songs show the South Londoner examining the human condition and his own complex wiring. Confession and self-reflection may be nothing new in rap, but they’ve rarely been done with such skill and imagination. Dave’s riveting and poetic at all times, documenting his experience as a young British black man (“Black”) and pulling back the curtain on the realities of fame (“Environment”). With a literary sense of detail and drama, “Lesley”—a cautionary, 11-minute account of abuse and tragedy—is as much a short story as a song: “Touched her destination/Way faster than the cab driver\'s estimation/She put the key in the door/She couldn\'t believe what she see on the floor.” His words are carried by equally stirring music. Strings, harps, and the aching melodies of Dave’s own piano-playing mingle with trap beats and brooding bass in incisive expressions of pain and stress, as well as flashes of optimism and triumph. It may be drawn from an intensely personal place, but *Psychodrama* promises to have a much broader impact, setting dizzying new standards for UK rap.

Written and recorded By Housewives Mixed and mastered by Rupert Clervaux Artwork by Joseph A.C. Rafferty Released by Blank Editions

slowthai knew the title of his album long before he wrote a single bar of it. He knew he wanted the record to speak candidly about his upbringing on the council estates of Northampton, and for it to advocate for community in a country increasingly mired in fear and insularity. Three years since the phrase first appeared in his breakout track ‘Jiggle’, Tyron Frampton presents his incendiary debut ‘Nothing Great About Britain’. Harnessing the experiences of his challenging upbringing, slowthai doesn’t dwell in self-pity. From the album’s title track he sets about systematically dismantling the stereotypes of British culture, bating the Royals and lampooning the jingoistic bluster that has ultimately led to Brexit and a surge in nationalism. “Tea, biscuits, the roads: everything we associate with being British isn’t British,” he cries today. “What’s so great about Britain? The fact we were an empire based off of raping and pillaging and killing, and taking other people’s culture and making it our own?” ‘Nothing Great About Britain’ serves up a succession of candid snapshots of modern day British life; drugs, disaffection, depression and the threat of violence all loom in slowthai’s visceral verses, but so too does hope, love and defiance. Standing alongside righteous anger and hard truths, it’s this willingness to appear vulnerable that makes slowthai such a compelling storyteller, and this debut a vital cultural document, testament to the healing power of music. As slowthai himself explains, “Music to me is the biggest connector of people. It don’t matter what social circle you’re from, it bonds people across divides. And that’s why I do music: to bridge the gap and bring people together.”

Singer-songwriter Natalie Mering’s fourth album as Weyes Blood conjures the feeling of a beautiful object on a shelf just out of reach: You want to touch it, but you can’t, and so you do the next best thing—you dream about it, ache for it, and then you ache some more. Grand, melodramatic, but keenly self-aware, the music here pushes Mering’s \'70s-style chamber pop to its cinematic brink, suffusing stories of everything from fumbled romance (the McCartney-esque “Everyday”) to environmental apocalypse (“Wild Time”) with a dreamy, foggy almost-thereness both gorgeous and profoundly unsettling. A self-described “nostalgic futurist,” Mering doesn’t recreate the past so much as demonstrate how the past is more or less a fiction to begin with, a story we love hearing no matter how sad its unreachability makes us. Hence the album’s centerpiece, “Movies,” which wonders—gorgeously, almost religiously—why life feels so messy by comparison. As to the thematic undercurrent of apocalypse, well, if extinction is as close as science says it is, we might as well have something pretty to play us out.

The phantom zone, the parallax, the upside down—there is a rich cultural history of exploring in-between places. Through her latest, Titanic Rising, Weyes Blood (a.k.a. Natalie Mering) has, too, designed her own universe to soulfully navigate life’s mysteries. Maneuvering through a space-time continuum, she intriguingly plays the role of melodic, sometimes melancholic, anthropologist. Tellingly, Mering classifies Titanic Rising as the Kinks meet WWII or Bob Seger meets Enya. The latter captures the album’s willful expansiveness (“You can tell there’s not a guy pulling the strings in Enya’s studio,” she notes, admiringly). The former relays her imperative to connect with listeners. “The clarity of Bob Seger is unmistakable. I’m a big fan of conversational songwriting,” she adds. “I just try to do that in a way that uses abstract imagery as well.” “An album is like a Rubik’s Cube,” she says. “Sometimes you get all the dimensions—the lyrics, the melody, the production—to line up. I try to be futuristic and ancient at once, which is a difficult alchemy. It’s taken a lot of different tries to get it right.” As concept-album as it may sound, it’s also a devoted exercise in realism, albeit occasionally magical. Here, the throwback-cinema grandeur of “A Lot’s Gonna Change” gracefully coexists with the otherworldly title track, an ominous instrumental. Titanic Rising, written and recorded during the first half of 2018, is the culmination of three albums and years of touring: stronger chops and ballsier decisions. It’s an achievement in transcendent vocals and levitating arrangements—one she could reach only by flying under the radar for so many years. “I used to want to belong,” says the L.A. based musician. “I realized I had to forge my own path. Nobody was going to do that for me. That was liberating. I became a Joan of Arc solo musician.” The Weyes Blood frontwoman grew up singing in gospel and madrigal choirs. “Classical and Renaissance music really influenced me,” says Mering, who first picked up a guitar at age 8. (Listen closely to Titanic Rising, and you’ll also hear the jazz of Hoagy Carmichael mingle with the artful mysticism of Alejandro Jodorowsky and the monomyth of scholar Joseph Campbell.) “Something to Believe,” a confessional that makes judicious use of the slide guitar, touches on that cosmological upbringing. “Belief is something all humans need. Shared myths are part of our psychology and survival,” she says. “Now we have a weird mishmash of capitalism and movies and science. There have been moments where I felt very existential and lost.” As a kid, she filled that void with Titanic. (Yes, the movie.) “It was engineered for little girls and had its own mythology,” she explains. Mering also noticed that the blockbuster romance actually offered a story about loss born of man’s hubris. “It’s so symbolic that The Titanic would crash into an iceberg, and now that iceberg is melting, sinking civilization.” Today, this hubris also extends to the relentless adoption of technology, at the expense of both happiness and attention spans. The track “Movies” marks another Titanic-related epiphany, “that movies had been brainwashing people and their ideas about romantic love.” To that end, Mering has become an expert at deconstructing intimacy. Sweeping and string-laden, “Andromeda” seems engineered to fibrillate hearts. “It’s about losing your interest in trying to be in love,” she says. “Everybody is their own galaxy, their own separate entity. There is a feeling of needing to be saved, and that’s a lot to ask of people.” Its companion track, “Everyday,” “is about the chaos of modern dating,” she says, “the idea of sailing off onto your ships to nowhere to deal with all your baggage.” But Weyes Blood isn’t one to stew. Her observations play out in an ethereal saunter: far more meditative than cynical. “I experience reality on a slower, more hypnotic level,” she says. “I’m a more contemplative kind of writer.” To Mering, listening and thinking are concurrent experiences. “There are complicated influences mixed in with more relatable nostalgic melodies,” she says. “In my mind my music feels so big, a true production. I’m not a huge, popular artist, but I feel like one when I’m in the studio. But it’s never taking away from the music. I’m just making a bigger space for myself.”

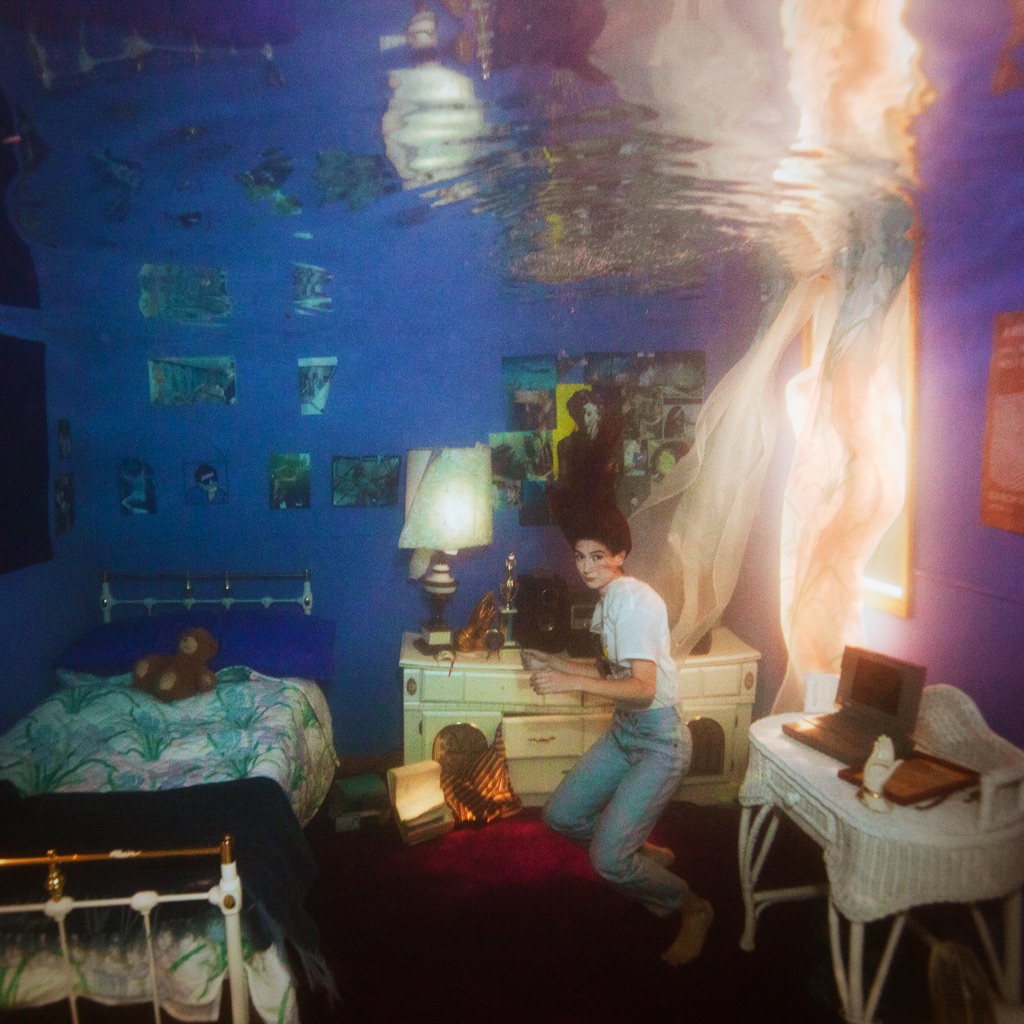

Though she’d been writing songs in her head since she was six, and on the guitar since she was 12, it took a long time for Nilüfer Yanya to work up the courage to show anyone her music. “I knew I wanted to sing, but the idea of actually having to do it was really horrifying,” says the 23-year-old. When she was finally persuaded to do so, by a music teacher in West London where she grew up, she says “it was horrible. I loved it”. At 18, Nilüfer – who is of Turkish-Irish-Bajan heritage – uploaded a few demos to SoundCloud. Though she’s preternaturally shy, her music – which uniquely blends elements of soul and jazz into intimate pop songs with electronic flourishes and a newly expressed grungy guitar sound – isn’t. And it didn’t take long for it to catch people’s attention. She signed with independent New York label ATO, following three EPs on esteemed london indie label Blue Flowers, and earned a place on the BBC Sound of 2018 longlist. She also supported the likes of The xx, Interpol, Broken Social Scene and Mitski on tour. Now, Nilüfer is ready to release her debut album, Miss Universe. Though she recorded much of it in the same remote Cornwall studio she used to jam in as a much younger person, it is bigger and more ambitious than anything she has done before. ‘Angels’, with its muted, harmonic riffs, channels ideas “of paranoid thoughts and anxiety” – a theme that runs through the album, not least in its conceptual spoken word interludes which emanate from a fictional health management company WWAY HEALTH TM. “You sign up, and you pay a fee,” explains Nilüfer of the automated messages, which are littered through the album and are narrated by the titular Miss Universe. “They sort out all of your dietary requirements, and then they move onto medication, and then maybe you can get a better organ or something… and then suddenly it starts to get a bit weird. You're giving them more of you and to what end?”

Ezra Collective ‘You Can’t Steal My Joy’ (Enter The Jungle) You Can’t Steal My Joy is an exuberant, defiant debut album that’s destined to cement Ezra Collective’s status as one of the UK’s most exciting groups. The record features friends and fans, Loyle Carner, KOKOROKO and Jorja Smith, and is preceded by lead single and full-blown banger, Quest For Coin. Ezra Collective are five young Londoners; bandleader Femi Koleoso (drums), his brother TJ Koleoso (bass), Joe Armon-Jones (keys), Dylan Jones (trumpet), and James Mollison (saxophone). The band’s incredible musicianship and spirited, inclusive approach to music - which draws on afrobeat, Latin, hip-hop, grime and more - has seen them break out beyond the thriving UK jazz scene. Ezra Collective’s 2017 EP, Juan Pablo: The Philosopher, won ‘Best Jazz Album’ at Gilles Peterson’s Worldwide Awards and the band picked up ‘Best UK Jazz Act’ and ‘Live Experience Of The Year’ at the 2018 Jazz FM Awards. They played Quincy Jones’ birthday party and recently completed a mosh-pit-filled and completely sold out UK tour before headlining Winter JazzFest in New York. Ezra Collective’s forthcoming gigs include All Point East, Lamar Tree and Green Man festivals and full headline tour of the UK culminating at The Roundhouse in London for November 2019. "Growing up as young people in London has challenges but, rather than focus on all the negativity surrounding us, we’ve decided to focus on the positives”, explains Femi. “You can steal a lot of things from us - our ability to travel freely, our access to education, our right to a level playing field, even our ability to live life at its full potential - but as long as we don’t forget our core truth, You Can’t Steal Our Joy.” Ezra Collective bring the fire on a stunning debut album // Crack Thrilling and vital /// Q A real coming of age /// MOJO An urgent, free-wheeling bundle of fun /// NME Ezra Collective have marked themselves out from the crowd with their genre-bridging prowess /// The Guardian the sound of London in 2019 distilled and put down on record /// Clash At the heart of a bubbling scene without a point of entry for many, Ezra Collective stand with their arms wide open /// Loud & Quiet British rave-jazz moves onwards and upwards /// The Observer Potent, rebellious, and uplifting /// Dork There is a lean exuberance to this band that demands a dancing response /// Rolling Stone One of the liveliest groups to emerge from London’s jazz renaissance /// New York Times

CD / LP / CASSETTE + MERCH AVAILABLE AT : found.ee/SMTB_DogWhistle

A raw and scintillating state-of-Dublin address.

An eccentric like Madlib and a straightforward guy like Freddie Gibbs—how could it possibly work? If 2014’s *Piñata* proved that the pairing—offbeat producer, no-frills street rapper—sounded better and more natural than it looked on paper, *Bandana* proves *Piñata* wasn’t a fluke. The common ground is approachability: Even at their most cinematic (the noisy soul of “Flat Tummy Tea,” the horror-movie trap of “Half Manne Half Cocaine”), Madlib’s beats remain funny, strange, decidedly at human scale, while Gibbs prefers to keep things so real he barely uses metaphor. In other words, it’s remarkable music made by artists who never pretend to be anything other than ordinary. And even when the guest spots are good (Yasiin Bey and Black Thought on “Education” especially), the core of the album is the chemistry between Gibbs and Madlib: vivid, dreamy, serious, and just a little supernatural.

Big Thief has been known to tackle intensely personal themes: family histories, deaths, isolation, fear. Here, on their expansive third album, the New York indie rock band shifts its gaze outward and into the unknown. \"Just like a bad dream/You\'ll disappear,” frontwoman Adrianne Lenker coos on the title track. \"And I imagine you/Taking me outta here.” Through gentle strums and hushed, tumbling melodies, the band wonders: Who\'s out there? Are they as strange as we are? What’s real? The second F in the album’s title stands for “friend”—an optimistic embrace of all things unfamiliar or alien. Their songs—comforting, eerie, folksy, magnificent—do the same.

U.F.O.F., F standing for ‘Friend’, is the name of the highly anticipated third record by Big Thief, set to be released on 3rd May 2019 via 4AD. U.F.O.F. was recorded in rural western Washington at Bear Creek Studios. In a large cabin-like room, the band set up their gear to track live with engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who was also behind their previous albums. Having already lived these songs on tour, they were relaxed and ready to experiment. The raw material came quickly. Some songs were written only hours before recording and stretched out instantly, first take, vocals and all. “Making friends with the unknown… All my songs are about this,” says Lenker; “If the nature of life is change and impermanence, I’d rather be uncomfortably awake in that truth than lost in denial.”

Making a debut album was a bruising experience for Dublin post-punk quintet The Murder Capital. “I didn’t know you could experience such a range of emotions in a day, every day,” singer James McGovern tells Apple Music. “I could feel utter despair, thinking that it was just not going to happen, it’s completely run ruin and it’s gone. Then, 20 minutes later, it’s genius and some new thing comes in and it’s just an overwhelming experience.” Recorded in London with storied producer Flood, *When I Have Fears* is as stirring to listen to as it was to make. Twisting through emotions that run from throbbing-temple rage to tender reflection, it’s an absorbing account of, among other things, isolation, grief, and a fading sense of community. Here, in a track-by-track guide, McGovern recalls the sleepy boat trips, stunned silences, and angry farmers that helped create the album. **“For Everything”** “This ended up being the opener because it feels very cinematic and we are all cinephiles. Also, the opening lyric seems, for me, like the right initial imprint on the floor. I wanted to go away on my own, so I looked for the cheapest flight I could find and went to Oslo—without looking at the price of stuff in Oslo. So I got this hostel for five nights and ate very rarely. I went around writing. I deleted everything off my phone and left. I left the world for five days, which was unbelievable. I went on a boat trip with some fjords and wrote it on that—there are a lot of little references to things I saw. I wrote a quick poem and then fell asleep for the entire boat trip that I paid 40 quid on.” **“More Is Less”** “In that incubation period in the very beginning \[of the band\], everything was just getting thrown in so quickly. If we played two shows a month, there might have been three or four new tracks in each show. I think ‘More Is Less’ was the first time we were like, ‘Oh, we’ll keep this.’ It sounds like it was written in a time of urgency, like I was fed up with something. I think your environment, politically and socially, naturally bleeds into you. It affects your mood and your view of yourself and the world. Even though it wasn’t that long ago, I feel like it was really naive at the time—but in a beautiful way.” **“Green & Blue”** “We were going through a pretty heavy drought in the writing room. I saw an article about \[American photographer\] Francesca Woodman and showed it to the boys. Everyone was hit in the chest by it, maybe even moist at the eye. There was something so alive about the way she depicted isolation. And something going through the record is this idea of isolation within a community, or the absence of fear giving love and the absence of love giving fear. We watched her documentary and the next day ‘Green & Blue’ just fell out.” **“Slowdance I”** “We got this cheap Airbnb in Mayo to finish writing. We actually had to move because a farmer threatened to shoot us for the noise. But in that first house, we wrote ‘Slowdance I,’ ‘Slowdance II,’ ‘Don’t Cling to Life,’ and something else. We were going in to record on March 2 and we went into that house on January 2, so that’s how up against the ropes we were. ‘Slowdance I’ came together over that bassline. We were fighting against keeping it at that tempo, going, ‘Don’t speed up, don\'t speed up.’ It was like pulling a rope at a mooring—it’s not giving way. We thought, ‘Maybe this is the way it should stay.’” **“Slowdance II”** “Part II was being written as a different idea. I named it that day, and then it very much became its own thing. Giving it that name became a visualization thing for us, imagining people moving to this track, that flow of the body. We love the idea of having something that just flows into the next thing. It just became this lotus flower or this opus. Lyrically, it became about disassociation somehow.” **“On Twisted Ground”** “My best friend took his own life and I couldn’t write about it for ages. When you’re writing about something so overtly personal, you can’t let anything go. It just has to be perfect. It was one of the hardest nuts to crack in the studio. Eventually, Cathal, our guitarist, just said, ‘Fuck everything: James and Gabriel \[bassist\] go in that room and play it alone.’ Immediately after we played it back, there was this crazy five minutes of silence. It was just so intense, like it was vibrating through you. Flood said he had never experienced anything like it in the studio before. Then we had this chat about how personal grief feels, and how hard done by you feel by it because your love for that person and their love for you is specific to you. No one else had that. It’s not a thing that gets better or worse or this bullshit of ‘it gets easier after time.’ You’re just like, ’I’m trying to fill my space with more positive things around that hole that will be there forever.’” **“Feeling Fades”** “We played the Sound House in Dublin. I came off the stage, went for a cigarette in the smoking area, and just started writing this poem to occupy the mind, because the feeling you get after getting offstage is weird. That’s reflected somewhat in the lyrics. It was also wondering if our generation is being robbed of a sense of community by whatever this natural evolution of technology and society is. I don’t want to be stuck in the past, but it feels like that sense of togetherness, that knocking over to a friend’s house, you have to *talk about* it now for it to exist. Humans still love each other just as much and are trying to understand each other better than ever, but something about the disassociative nature of technology is sort of harrowing. I just wanna hang out with people, you know?” **“Don’t Cling to Life”** “Gabriel’s mum became severely unwell, and she actually passed away within the first two weeks of recording. While this was going on, we discussed that idea of songs like ‘Perfect Day’ or ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart,’ where it sounds happy but it’s completely not. Gabriel came into the house \[in Mayo\] and he was like, ‘Let’s just write something we can dance to.’ It was quite a tough nut to crack because it was veering more to the pop side of things than to anything we had written before. I like the possibility it gives you for juxtaposition: It doesn’t have to be really dark, it can be really hopeful as well—it just depends which way you play the words in your mind. You can go to it for anything.” **“How the Streets Adore Me Now”** “That was one that wasn’t written \[before going into the studio\]. Cathal had this droning, repeated piano idea. He was playing it on an old upright, and I remember just flicking through my journal and finding this poem. I sat in next to him and we figured it out and had it recorded within an hour. When we listened back, we were all like, ‘Holy fucking shit.’ Flood was like, ‘You’re not going to touch that.’ I think it is my favorite song.” **“Love, Love, Love”** “We decided, pretty quickly, that this was going to close the record. It was very important for us to have that. It was imperative that there was a narrative, there was a feeling of where do we bring you now and where do we go next and how are you left and are you being challenged? We look to people like Alexander McQueen, who said, ‘If you aren\'t affected by my show, then I haven\'t done my job.’ Sometimes music or art or theater should be making you uncomfortable. It should be confronting you with something, then almost immediately comforting you and all those things. ‘Love, Love, Love,’ I find, does that. It’s also satisfying to finish an album saying, ‘Goodbye, goodbye.’”

The science-fiction visionary Octavia Butler once declared that “there is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” The aphorism could apply to any art form where the basic contours are fixed, but the appetite for innovation remains infinite. Enter Clipping, flash fiction genre masters in a hip-hop world firmly rooted in memoir. If first person confessionals historically reign, the mid-city Los Angeles trio of rapper Daveed Diggs and producers William Hutson and Jonathan Snipes have spent the last half-decade terraforming their own patch of soil, replete with conceptual labyrinths and industrial chaos. They have conjured a mutant emanation of the future, built at odd angles atop the hallowed foundation of the past. Their third album for Sub Pop, There Existed an Addiction to Blood, finds them interpreting another rap splinter sect through their singular lens. This is clipping’s transmutation of horrorcore, a purposefully absurdist and creatively significant sub-genre that flourished in the mid-90s. If some of its most notable pioneers included Brotha Lynch Hung and Gravediggaz, it also encompasses seminal works from the Geto Boys, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, and the near-entirety of classic Memphis cassette tape rap. The most subversive and experimental rap has often presented itself as an “alternative” to conventional sounds, but Clipping respectfully warp them into new constellations. There Existed an Addiction to Blood absorbs the hyper-violent horror tropes of the Murder Dog era, but re-imagines them in a new light: still darkly-tinted and somber, but in a weirder and more vivid hue. If traditional horrorcore was akin to Blacula, the hugely popular blaxploitation flick from the early 70s, Clipping’s latest is analogous to Ganja & Hess, the blood-sipping 1973 cult classic regarded as an unsung landmark of black independent cinema, whose score the band samples on “Blood of the Fang.” From the opening “Intro,” Clipping summon an unsettling eeriness. Diggs sounds like he’s rapping through a drive-thru speaker about the bottom falling out, bodies hitting the floor, and recurrent ghosts. You hear ambient noises, footsteps and shovels. The hairs on your arms stick up like bayonets. You can practically see the knife’s edge, sharp and luminous. Each song contains its own premise and conceptual bent. There is “Nothing is Safe,” a reversal of Assault on Precinct 13, where the band create their own version of a John Carpenter-inspired rap beat and the cops are the ones raiding a trap house. Diggs sketches the narrative from the perspective of the victims, full of lurid and visceral details and intricate wordplay. The windows are boarded and sealed, the product simmers on the stove, the bodies sleep fitfully in shifts. Then law enforcement arrives and the bullets start to fly. “He Dead” turns police officers into werewolves while Diggs flips Kendrick Lamar’s “Riggamortis” into something gravely literal.“All In Your Head” finds Clipping re-contextualizing the pimp talk of Suga Free and Too $hort into a metaphor for an Exorcist-style possession. The album contains interludes featuring hissing recordings of demonic invasions and guest appearances from Griselda Gang’s Benny the Butcher and Hypnotize Minds horror queen La Chat. Other tracks feature contributions from noise music legends The Rita and Pedestrian Deposit. It all ends with “Piano Burning,” a performance of a piece written by the avant-garde composer Annea Lockwood. Yes, it is the sound of a piano burning. In the hands of the less imaginative or less virtuosic, it could come off as overwrought or pretentious. Instead, Clipping annex new terrain for a sub-genre often left for dead. In its own way, one could compare what they’ve accomplished to Tarantino’s post-modern reworkings of critically overlooked but creatively fertile blaxploitation, horror and spaghetti western cinema. Everything fits neatly into the broader scope of the band’s career, which has seen them expand from insular experimentalists into globally recognized artists. Since the release of their first album in 2013, Diggs has won a Tony and a Grammy, as well as co-written and starred in 2018’s critically hailed Blindspotting, while Snipes and Hutson have scored numerous films and television shows. Clipping’s last album, the 2016 afro-futurist dystopian space opus Splendor & Misery was recently named one of Pitchfork’s Best Industrial Albums of All-Time. Commissioned for an episode of “This American Life,” their 2017 single “The Deep” became the inspiration for a novel of the same name, written by Rivers Solomon and published by Saga Press. But it’s their latest masterwork that embodies what the band had been building towards — a work that finds them without peer. This is experimental hip-hop built to bang in a post-apocalyptic club bursting with radiation. It’s horror-core that soaks up past blood and replants it into a different organism, undead but dangerously alive. It is a new sun, blindingly bright and built to burn your retinas.

“It feels quite sinister,” Kano tells Apple Music about the title of his exceptional sixth album, *Hoodies All Summer*. “But a hoodie’s also like a defense mechanism—a coat of armor, protection from the rain. It’s like we always get rained on but don’t worry, we’re resilient, we wear hoodies all summer. We’re prepared for whatever.” That description is fitting for 10 songs that tear down stereotypes and assumptions to reveal the humanity and bigger picture of life in London’s toughest quarters. On “Trouble” that means reflecting with nuance and empathy on the lives being lost to postcode wars and knife and gun crime. “People become so used to the fact that these situations happen that they are almost numb to it,” he says. “Young kids dying on the street—it gets to a point where it’s like you lose count, and you just move on really quickly and forget a person’s name two minutes after hearing about it.” Like 2016’s *Made in the Manor*, this is an album rooted in his experiences of living in East London. This time, though, the focus is less introspective, with Kano, as he says, “reversing the lens” toward the communities he grew up in. “I just wanted to speak about it in a way where it\'s like, ‘I understand, I get it.’ I\'ll get into the psyche of why people do what they do. It’s about remembering that these unfortunate situations come about because of circumstances that are out of the hands of people involved. Not everyone’s this gang-sign, picture-taking, hoodie-wearing gang member. That’s the way they put us across in the media. Yes, some people are involved in crime, and some people are *not*—they just live in these areas, and it’s a fucked-up situation.” Kano’s at his poetic and potent best here. Lines such as “All our mothers worry when we touch the road/\'Cause they know it’s touch-and-go whether we’re coming home” (“Trouble”) impact fast and deep, but he also spotlights hope amid hard times. “I feel like we’re resilient people and there’s always room for a smile and to celebrate the small wins, and the big wins,” he says. “That’s when you hear \[tracks\] like \'Pan-Fried\' and \'Can\'t Hold We Down\'—you can\'t hold us down, no matter what you do to us, you can\'t stop us. We’re a force, you can\'t stop us creatively. I want more for you: I’ve made it through, I want you to see what I’ve seen. It’s about everyone having the opportunity to see more, so they’ll want more, to feel like they are more.” If the wisdom of Kano’s bars positions him as an elder statesman of UK rap, the album as a whole confirms that he’s an undisputed great of the genre. Musically, it sets new standards in vision and ambition, complementing visceral electronic beats with strings and choirs as it moves through exhilarating left turns and dizzying switches of pace and intensity. “I wanted it to be an exciting listen,” he says. “Like the beat that comes in from nowhere in ‘Teardrops’—it’s like a slap in the face. This ain’t the album that you just put on in the background. I didn\'t want it to be that. You need to dedicate time out of your day to listen to this.”

Holding fast to the emotional honesty of Playing House (2017), Common Holly’s sophomore record, When I say to you Black Lightning is a look outward; an exploration of the ways in which we all experience pain, fear and self-delusion, and how we can learn to confront those feelings with boldness. A swift change of course, WISTYBL couples a submergence into the dark and dissonant with its consolation in harmony, and a dose of dry humour. The record is more experimental than Brigitte Naggar’s debut. It is rougher, looser, louder and more atonal. It feels edgy, but still kind. WISTYBL ditches fear without losing vulnerability, and trades in sadness for the healing powers of anger, and the strength of observing, recognizing and confronting. Through its 9 labyrinthian yet catchy tracks, shaped sonically by the seriously unique visions of Devon Bate, Hamish Mitchell, and Naggar herself, the album observes the complexities of mental health, the precarity of life, and the challenges of finding strength in the face of grave misunderstanding. On its own, When I Say to you Black Lightning is a phrase which holds authority-- it does not apologize for itself, it stands boldly where it is, and yet it also laughs at itself for daring to take up that space. The title phrase is directive - it suggests a thought without completing it, engaging you to contemplate what comes next and pointing the finger away from itself to somewhere undefined. If Playing House was about personal turmoil, WISTYBL is about humanity’s emotional challenges and how we each approach them as individuals. The former centered around one person and one heartbreak, while the latter circles different characters that Naggar has observed or interacted with—romantically or otherwise, whose stories cumulate in a whimsically entertaining tale of struggle, and the resulting emotional growth.

It takes a village to raise a child; Holly Herndon’s third proper studio LP, *PROTO*, holds that the same is true for an artificial intelligence, or AI. The Berlin-based electronic musician’s 2015 album *Platform* explored the intersection of community and technological utopia, and so does its follow-up—only this time, one of her collaborators is a programmed entity, a virtual being named Spawn. Arguing that technology should be embraced, not feared, Herndon and her human collaborators, including a choral ensemble and hundreds of volunteer vocal coaches, set about “teaching” their AI via call-and-response singing sessions inspired by Herndon’s religious upbringing in East Tennessee. The results harness *Platform*’s richly synthetic palette and jagged percussive force and join them with choral music of almost overwhelming beauty. The massed voices of “Frontier” suggest a combination of Appalachian revival meetings and Bulgarian folk that’s been cut up over Hollywood-blockbuster drums; in “Godmother,” a collaboration with the experimental footwork producer Jlin, Spawn “sings” a dense, hyperkinetic fugue based on Jlin’s polyrhythmic signature. The crux of the whole album might be “Extreme Love,” in which a narrator recounts the story of a future post-human generation: “We are not a collection of individuals but a macro-organism living as an ecosystem. We are completely outside ourselves and the world is completely inside us.” A loosely synchronized choir chirps in the background as she asks, in a voice full of childlike wonder, “Is this how it feels to become the mother of the next species—to love them more than we love ourselves?” It’s a moving encapsulation of the album’s radical optimism.

Holly Herndon operates at the nexus of technological evolution and musical euphoria. Holly’s third full-length album 'PROTO' isn’t about A.I., but much of it was created in collaboration with her own A.I. ‘baby’, Spawn. For the album, she assembled a contemporary ensemble of vocalists, developers, guest contributors (Jenna Sutela, Jlin, Lily Anna Haynes, Martine Syms) and an inhuman intelligence housed in a DIY souped-up gaming PC to create a record that encompasses live vocal processing and timeless folk singing, and places an emphasis on alien song craft and new forms of communion. 'PROTO' makes reference to what Holly refers to as the protocol era, where rapidly surfacing ideological battles over the future of A.I. protocols, centralised and decentralised internet protocols, and personal and political protocols compel us to ask ourselves who are we, what are we, what do we stand for, and what are we heading towards? You can hear traces of Spawn throughout the album, developed in partnership with long time collaborator Mathew Dryhurst and ensemble developer Jules LaPlace, and even eavesdrop on the live training ceremonies conducted in Berlin, in which hundreds of people were gathered to teach Spawn how to identify and reinterpret unfamiliar sounds in group call-and-response singing sessions; a contemporary update on the religious gathering Holly was raised amongst in her upbringing in East Tennessee. “There’s a pervasive narrative of technology as dehumanizing,” says Holly. “We stand in contrast to that. It’s not like we want to run away; we’re very much running towards it, but on our terms. Choosing to work with an ensemble of humans is part of our protocol. I don’t want to live in a world in which humans are automated off stage. I want an A.I. to be raised to appreciate and interact with that beauty.” Since her arrival in 2012, Holly has successfully mined the edges of electronic and Avant Garde pop and emerged with a dynamic and disruptive canon of her own, all while studying for her soon-to-be-completed PhD at Stanford University, researching machine learning and music. Just as Holly’s previous album 'Platform' forewarned of the manipulative personal and political impacts of prying social media platforms long before popular acceptance, 'PROTO' is a euphoric and principled statement setting the shape of things to come.