Far Out Magazine's 50 Best Albums of 2019

In a review of 2019, Far Out Magazine discusses albums from Julia Jacklin, Nick Cave, Lizzo and more in its top 50 albums of the year list.

Published: December 24, 2019 11:08

Source

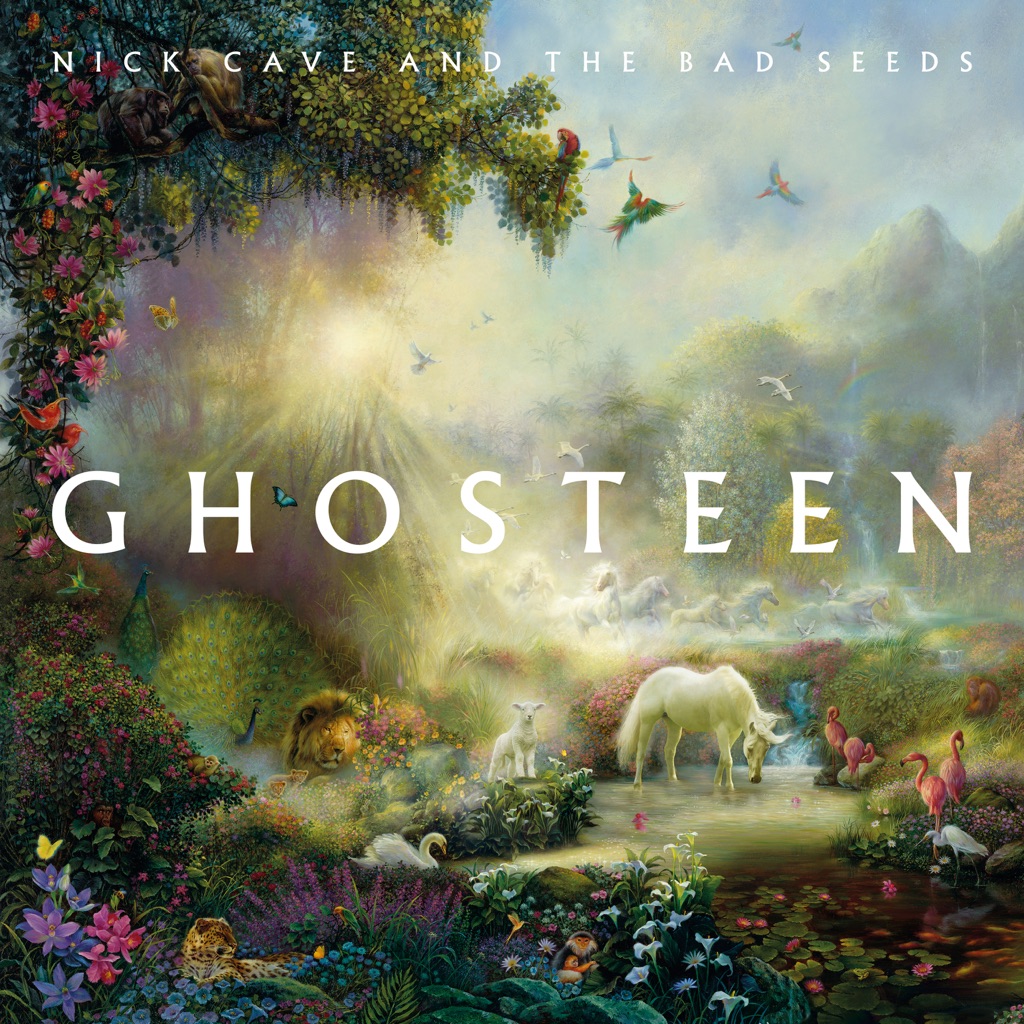

The cover art for Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ 17th album couldn’t feel more removed from the man once known as a snarling, terrifying prince of poetic darkness. This heavenly forest with its vibrant flowers, rays of sun, and woodland creatures feels comically opposed to anything Cave has ever represented—but perhaps that’s the point. This pastel fairy tale sets the scene for *Ghosteen*, his most minimalist, supernatural work to date, in which he slips between realms of fantasy and reality as a means to accept life and death, his past and future. In his very first post on The Red Hand Files—the website Cave uses to receive and respond to fan letters—he spoke of rebuilding his relationship with songwriting, which had been damaged while enduring the grief that followed his son Arthur’s death in 2015. He wrote, “I found with some practise the imagination could propel itself beyond the personal into a state of wonder. In doing so the colour came back to things with a renewed intensity and the world seemed clear and bright and new.” It is within that state of wonder that *Ghosteen* exists. “The songs on the first album are the children. The songs on the second album are their parents,” Cave has explained. Those eight “children” are misty, ambient stories of flaming mares, enchanted forests, flying ships, and the eponymous, beloved Ghosteen, described as a “migrating spirit.” The second album features two longer pieces, connected by the spoken-word “Fireflies.” He tells fantasy stories that allude to love and loss and letting go, and occasionally brings us back to reality with detailed memories of car rides to the beach and hotel rooms on rainy days. These themes aren’t especially new, but the feeling of this album is. There are no wild murder ballads or raucous, bluesy love songs. Though often melancholy, it doesn’t possess the absolute devastation and loneliness of 2016’s *Skeleton Tree*. Rather, these vignettes and symbolic myths are tranquil and gentle, much like the instrumentation behind them. With little more than synths and piano behind Cave’s vocals, *Ghosteen* might feel uneventful at times, but the calmness seems to help his imagination run free. On “Bright Horses,” he sings of “Horses broken free from the fields/They are horses of love, their manes full of fire.” But then he pulls back the curtain and admits, “We’re all so sick and tired of seeing things as they are/Horses are just horses and their manes aren’t full of fire/The fields are just fields, and there ain’t no lord… This world is plain to see, it don’t mean we can’t believe in something.” Through these dreamlike, surreal stories, Cave is finding his path to peace. And he’s learned that he isn’t alone on his journey. On “Galleon Ship,” he begins, “If I could sail a galleon ship, a long, lonely ride across the sky,” before realizing: “We are not alone, it seems, so many riders in the sky/The winds of longing in their sails, searching for the other side.”

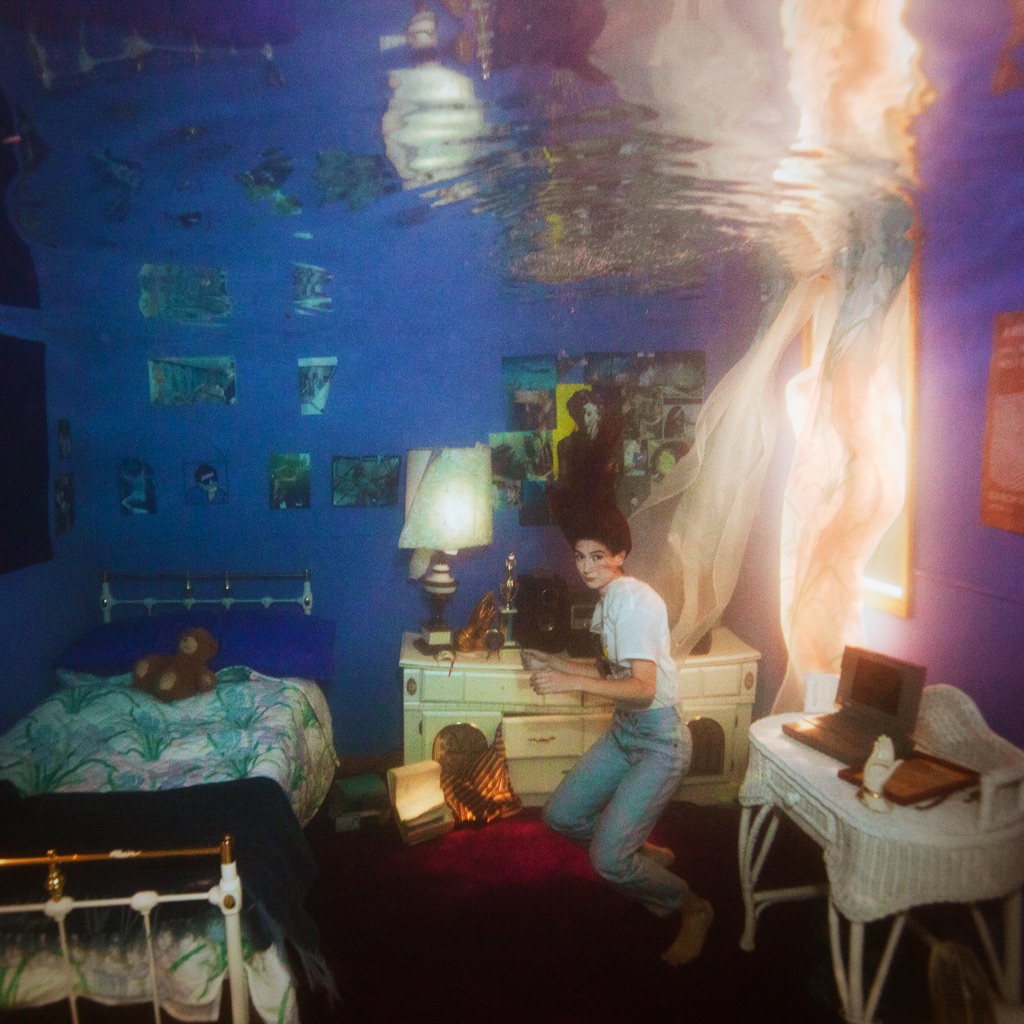

On her fifth proper full-length album, Sharon Van Etten pushes beyond vocals-and-guitar indie rock and dives headlong into spooky maximalism. With production help from John Congleton (St. Vincent), she layers haunting drones with heavy, percussive textures, giving songs like “Comeback Kid” and “Seventeen” explosive urgency. Drawing from Nick Cave, Lucinda Williams, and fellow New Jersey native Bruce Springsteen, *Remind Me Tomorrow* is full of electrifying anthems, with Van Etten voicing confessions of reckless, lost, and sentimental characters. The album challenges the popular image of Van Etten as *just* a singer-songwriter and illuminates her significant talent as composer and producer, as an artist making records that feel like a world of their own.

Marika Hackman’s second album, 2017’s *I’m Not Your Man*, gave the English singer-songwriter a lot to reflect on. “Being so open about my sexuality and having a response from young women saying it helped them to realize who they are and come out—that isn’t something that just washes over you,” she tells Apple Music. “I hold that in my heart and it’s very much a driving force.” That momentum can be felt throughout Hackman’s third album as she explores sex between two women (“all night”), inhabiting the mind of her ex to confront a breakup (“send my love”), and masturbation (“hand solo”) with bracing candor and propulsive synths. “Coming to this record I thought, ‘All right. I’ll do it, I\'ll be more open.’” Let Hackman guide you through her darkly comic journey of what it means to be human, track by track. **“wanderlust”** “I wrote this song in a matter of hours, and this is the first recording ever of it. It’s just me at the kitchen table with the mic on a pair of Apple headphones, the old ones. It’s been sitting in my bank for a while; I didn’t want it on the last album because it felt too similar to my first and I wanted to pull away from that. When I wrote ‘the one’ \[the following track\], it felt like this would be the perfect opener to lull the listener into a false sense of security about where I’d gone with my music this time around, like, ‘Oh, it’s the old Marika that I know and love.’” **“the one”** “This is the first song I wrote specifically for this album. It really set the tone and surprised me. I deal with a lot through humor; I think it’s a good way of connecting with people. It invites them in. The track was born out of feeling frustrated: I’ve been doing this for a long time and sometimes I wish I was bigger. It was taking that as a concept and exaggerating the fuck out of it to make this big joke. I don’t like this part of myself—I don’t like being frustrated or jealous—so I wanted to push that feeling as far as I could. I turned it into something external that I can sit back and laugh at.” **“all night”** “The intention with this song was to openly explore sex between two women in a celebratory, honest way. Because that’s my experience of sex, so that’s the only way I can talk about it. The whole ‘kissing, eating, fucking, moaning’ part, that was saved in the notes on my phone for a really long time. I get a lot of ideas when I’m on buses if I’ve been on a night out. I had this idea about describing your mouth as being something just for eating and moaning. Then you flip that and the eating becomes the fucking and kissing and moaning. I like wordplay and to pretend it’s going somewhere then take you somewhere else.” **“blow”** “I wanted every instrument to have a purpose in the part that it was playing, not just be a wash of color or for some atmosphere. On this track there’s funky basslines interlocking with wild drum parts and then a space where the jagged, gnarly guitar lines stick out. I’ve never written like that before, and I think that’s because my confidence in playing guitar has really jumped up in the last couple of years from touring.” **“i’m not where you are”** “One of the fans summed this up perfectly: ‘It’s the anthem for the emotionally detached that we never had before.’ That was exactly what I was aiming to do, but I hadn’t put it in those words. There’s an aloofness that people often attribute to being unavailable that’s kinda sexy and cool. And it’s not at all. It’s horrible to feel like you can’t just let go and throw yourself into something because of fear. You often hear songs about people who are so hard to get; I wanted to write it from the other perspective of someone who’s like, ‘I don’t know how to connect. I don’t feel on the same level as most people I meet.’ That’s very lonely.” **“send my love”** “This is about the end of a relationship with my ex, Amber \[of The Japanese House\], and it’s me inhabiting her. I was using her character as the mouthpiece for me to say how I was feeling about myself when we were breaking up. I can only share my experience by saying, ‘This must be how you feel about me right now because this is how I feel about myself.’ And then she listens to it and thinks the lyrics are really sad, because she was like, ‘That’s not how I view you or ever viewed you.’ The lyrics are pretty brutal. There’re all of those elements of nostalgia and regret—that’s what happens when things come to an end. When I listen to the song, I can feel that streak of self-loathing, self-hatred, and sadness, but it’s just a moment in time. That was how I was feeling then, and things change. We’re like best friends now.” **“hand solo”** “One lyric that will get overlooked because I don’t think many people are gonna understand the reference, but the first half of the song is looking at old wives’ tales about masturbation. One of them I read is that you get hairy hands if you masturbate too much. There’s a line in there that says, ‘Oh, monkey glove’—it’s talking about having hairy hands. It’s quite abstract but it sounds sexual as well. It sounds like something you might call your vagina. And it’s quite gross, that song. ‘Dark meat, skin pleat’—it’s all quite visceral. My favorite lyric is obviously ‘Under patriarchal law, I’m gonna die a virgin.’ That is insane, that is crazy! I feel like people don’t take my sexual experiences as real. The song is also a massive fuck-you, because it’s very funny and empowered with a bit of sass.” **“conventional ride”** “This song is about that classic thing where you feel like a straight girl might think she’s into it, but she’s fulfilling some sort of fantasy. Which is fine—that’s something that should be explored—but it’s about being open and honest about that with whoever you’re sleeping with. This is about me being like, ‘Maybe you just need a conventional ride. You’re not really into this. You started off thinking you were, but you’re pulling me along.’ The song has that feeling of momentum, being pulled along by something when it’s not quite right.” **“come undone”** “I was listening to a lot of Crumb and I thought, ‘They’ve got some funky basslines. I wanna write a funky bassline!’ That’s often how a lot of my creative process starts: ‘I wanna do that too.’ Like a petulant child! I wrote the bassline and I thought there’s not enough room for anything to go over the top of this, but I kept with it and wrote a nice drum beat that locked in with this. It’s pretty simple, letting that bassline sing with a flourish of guitar pulling your attention left and right.” **“hold on”** “This song was written on a little MIDI keyboard. I’d never written a song like that before. I went for something a bit like Massive Attack or Radiohead, and it swept off into this big beast that I didn’t really anticipate. It’s a sad song; I was going through a really severe bout of depression that I hadn’t felt intensely before. Maybe that’s why the lyrics don’t make that much sense. It’s like a big exhale. I think I might explore that style of writing a bit more—that was my first foray, and it would be exciting to see if I can do a bit more electronic.” **“any human friend”** “I knew immediately this was going to be the last song on the record because it has this optimism to it. It’s a moment to just breathe and let it wash over you. There’s a very conscious decision right at the end when the acoustic guitar comes in repeating the riff ’til it floats away to bring it back to how ‘wanderlust’ starts and lands it again back into the real world. On this album there’s quite a lot of psychedelic segues between the songs and there’s not much room to breathe; it’s quite intense. Then it spits you out and there’s this tiny little anchor at the end, pulling you back into the room.”

“hand solo,” “blow,” “conventional ride”—these are just a few of the cheeky offerings off Any Human Friend, the new album from rock provocateur Marika Hackman. “This whole record is me diving into myself and peeling back the skin further and further, exposing myself in quite a big way. It can be quite sexual,” Hackman says. “It’s blunt, but not offensive. It’s mischievous.” There’s also depth to her carnal knowledge: Any Human Friend is ultimately about how, as she puts it, “We all have this lightness and darkness in us.” Hackman lifted the album’s title from a documentary about four-year-olds interacting with dementia patients in senior homes. At one point, two little girls confer about their experience there, with one musing on how it’s great to make “any human friend,” whether old or young. “When she said that it really touched a nerve in me,” says the London-based musician. “It’s that childlike view where we really accept people, are comfortable with their differences.” Such introspection has earned Hackman her name. Her folkie 2015 debut, We Slept at Last, was heralded for being nuanced and atmospheric. She really found her footing with her last release, I’m Not Your Man—which earned raves from The Guardian, Stereogum, and Pitchfork—and its sybaritic, swaggering hit “Boyfriend,” which boasts of seducing away a straight guy’s girlfriend. “Her tactile lyrics keep the songs melodically strong and full of surprises,” remarked Pitchfork. We’ll say! “I’m a hopeless romantic,” she explains. “I search for love and sexual experience, but also I’m terrified by it.” Hackman is a Rid of Me-era PJ Harvey for the inclusive generation: unbounded by musical genre, a preternatural lyricist and tunesmith who isn’t afraid to go there. (Even her cover art, which finds Hackman nearly nude while cradling a baby pig, is a nod to Dutch photographer Rineke Dijkstra’s unfiltered photos of mothers just after they gave birth.) To that end, “hand solo” extorts the virtues of masturbation and features Hackman’s favorite line, “Under patriarchal law, I’m going to die a virgin.” The song “blow” paints a picture of social excess. And “conventional ride” thumbs its nose at heterosexual sex through “the trope a lot of gay women experience: sleeping with someone, then it becomes apparent you’re kind of an experiment.” With Any Human Friend, boundaries are no longer an issue for her. “I sent ‘all night’ to my parents and they were quite shocked,” she says of the paean to the flesh, dressed as a sweetly harmonic track. “Why does it sound shocking coming out of my mouth? Women have sex with each other, and it seems to me we aren’t as freely allowed to discuss that as men are. But at no point am I disrespecting the women I’m having sex with. It can be fucking sexy without banging people over the head with a frying pan. It’s sexy sex.” Sharing intimacies with her parents sorta makes sense when you consider she wrote “the one”—a portrait of the artist amid identity crisis—and several other songs in her bedroom at their house, where she crashed after a painful break-up with a longtime girlfriend. “‘send my love’ is a proper breakup song,” she says of the levitating, string-laden track. “I actually wrote that in a moment of grief. It’s a strange take on it because I’m imagining myself as my ex-girlfriend.” She penned its companion track, “i’m not where you are,” a melodic earworm about emotional detachment from relationships, roughly six months later. “I think because my life was flipped upside down, it was taking me longer to write,” she says. “This was definitely the hardest process I’ve gone through to make a record.” She wrote the album over a year, recording a few songs at a time with co-producer David Wrench (Frank Ocean, The xx). “I stopped being able to sleep properly,” she says. “I was waking up in the middle of the night to write songs.” But the longer recording process also meant that Hackman had the time to experiment in the studio, especially with electronic songs. She was inspired by Wrench’s vast synth collection, many of which she used throughout Any Human Friend (“the synths give the album a nice shine”), notably on “hold on,” a deep dive into ennui expressed as ethereal R&B. She also switched up drum rhythms and wrote songs on the bass, such as the upbeat, idiosyncratic “come undone” (working name: “Funky Little Thang”). Hackman bookends Any Human Friend with some of her most unexpected musical turns. The first song she wrote, “the one” (technically its second track), is “probably the poppiest song I’ve ever written,” she says. “It’s about that weird feeling of starting the process again from scratch.” To that end, it features a riot grrrl Greek chorus hurling such insults at her as, “You’re such an attention whore!” The title track closes out the album and explores how, “when we’re interacting with people, it’s like holding a mirror up to yourself.” It’s a weightless coda that’s jazz-like in its layering of rhythmic sounds as if you’re leisurely sorting through Hackman’s headspace. “The drive to do all this is all just about trying to work out what the fuck is in my brain,” she says, laughing. The dragon she’s chasing is a rarified peace that materializes after properly tortured herself. “I really did have a good time working on this album,” she says, reassuringly. “It’s just emotionally draining to write music and constantly tap into your psyche. No musician is writing music for themselves to listen to. It’s a dialogue, a conversation, a connection. I’m creating something for people to react to.”

In some ways, Aldous Harding’s third album, *Designer*, feels lighter than her first two—particularly 2017’s stunning, stripped-back, despairing *Party*. “I felt freed up,” Harding (whose real name is Hannah) tells Apple Music. “I could feel a loosening of tension, a different way of expressing my thought processes. There was a joyful loosening in an unapologetic way. I didn’t try to fight that.” Where *Party* kept the New Zealand singer-songwriter\'s voice almost constantly exposed and bare, here there’s more going on: a greater variety of instruments (especially percussion), bigger rhythms, additional vocals that add harmonies and echoes to her chameleonic voice, which flips between breathy baritone and wispy falsetto. “I wanted to show that there are lots of ways to work with space, lots of ways you can be serious,” she says. “You don’t have to be serious to be serious. I’m not a role model, that’s just how I felt. It’s a light, unapologetic approach based on what I have and what I know and what I think I know.” Harding attributes this broader musical palette to the many places and settings in which the album was written, including on tour. “It’s an incredibly diverse record, but it somehow feels part of the same brand,” she says. “They were all written at very different times and in very different surroundings, but maybe that’s what makes it feel complete.” The bare, devastating “Heaven Is Empty” came together on a long train ride and “The Barrel” on a bike ride, while intimate album closer “Pilot” took all of ten minutes to compose. “It was stream of consciousness, and I don’t usually write like that,” she says. “Once I’d written it all down, I think I made one or two changes to the last verse, but other than that, I did not edit that stream of consciousness at all.” The piano line that anchors “Damn” is rudimentary, for good reason: “I’m terrible at piano,” she says. “But it was an experiment, too. I’m aware that it’s simple and long, and when you stretch out simple it can be boring. It may be one of the songs people skip over, but that’s what I wanted to do.” The track is, as she says, a “very honest self-portrait about the woman who, I expect, can be quite difficult to love at times. But there’s a lot of humor in it—to me, anyway.”

Aldous Harding’s third album, Designer is released on 26th April and finds the New Zealander hitting her creative stride. After the sleeper success of Party (internationally lauded and crowned Rough Trade Shop’s Album of 2017), Harding came off a 200-date tour last summer and went straight into the studio with a collection of songs written on the road. Reuniting with John Parish, producer of Party, Harding spent 15 days recording and 10 days mixing at Rockfield Studios, Monmouth and Bristol’s J&J Studio and Playpen. From the bold strokes of opening track ‘Fixture Picture’, there is an overriding sense of an artist confident in their work, with contributions from Huw Evans (H. Hawkline), Stephen Black (Sweet Baboo), drummer Gwion Llewelyn and violinist Clare Mactaggart broadening and complimenting Harding’s rich and timeless songwriting.

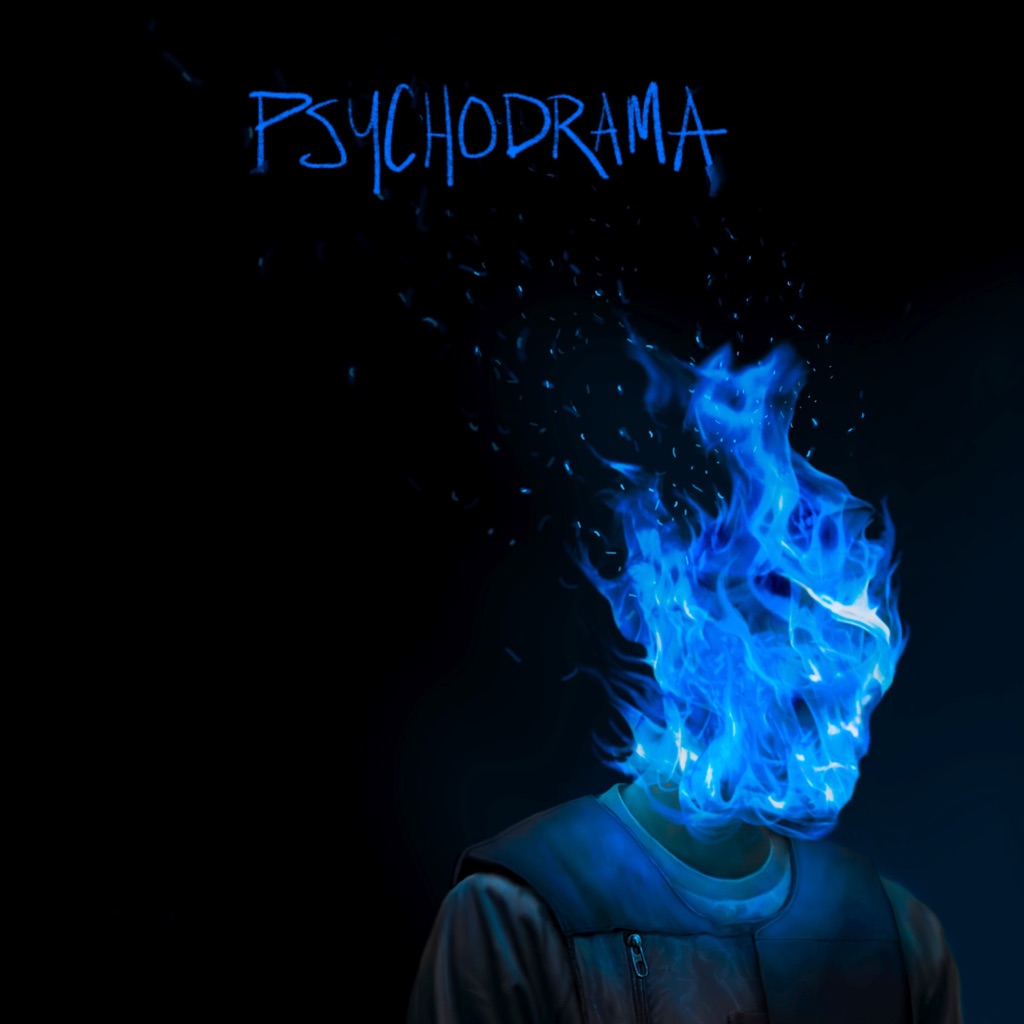

The more music Dave makes, the more out of step his prosaic stage name seems. The richness and daring of his songwriting has already been granted an Ivor Novello Award—for “Question Time,” 2017’s searing address to British politicians—and on his debut album he gets deeper, bolder, and more ambitious. Pitched as excerpts from a year-long course of therapy, these 11 songs show the South Londoner examining the human condition and his own complex wiring. Confession and self-reflection may be nothing new in rap, but they’ve rarely been done with such skill and imagination. Dave’s riveting and poetic at all times, documenting his experience as a young British black man (“Black”) and pulling back the curtain on the realities of fame (“Environment”). With a literary sense of detail and drama, “Lesley”—a cautionary, 11-minute account of abuse and tragedy—is as much a short story as a song: “Touched her destination/Way faster than the cab driver\'s estimation/She put the key in the door/She couldn\'t believe what she see on the floor.” His words are carried by equally stirring music. Strings, harps, and the aching melodies of Dave’s own piano-playing mingle with trap beats and brooding bass in incisive expressions of pain and stress, as well as flashes of optimism and triumph. It may be drawn from an intensely personal place, but *Psychodrama* promises to have a much broader impact, setting dizzying new standards for UK rap.

Big Thief has been known to tackle intensely personal themes: family histories, deaths, isolation, fear. Here, on their expansive third album, the New York indie rock band shifts its gaze outward and into the unknown. \"Just like a bad dream/You\'ll disappear,” frontwoman Adrianne Lenker coos on the title track. \"And I imagine you/Taking me outta here.” Through gentle strums and hushed, tumbling melodies, the band wonders: Who\'s out there? Are they as strange as we are? What’s real? The second F in the album’s title stands for “friend”—an optimistic embrace of all things unfamiliar or alien. Their songs—comforting, eerie, folksy, magnificent—do the same.

U.F.O.F., F standing for ‘Friend’, is the name of the highly anticipated third record by Big Thief, set to be released on 3rd May 2019 via 4AD. U.F.O.F. was recorded in rural western Washington at Bear Creek Studios. In a large cabin-like room, the band set up their gear to track live with engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who was also behind their previous albums. Having already lived these songs on tour, they were relaxed and ready to experiment. The raw material came quickly. Some songs were written only hours before recording and stretched out instantly, first take, vocals and all. “Making friends with the unknown… All my songs are about this,” says Lenker; “If the nature of life is change and impermanence, I’d rather be uncomfortably awake in that truth than lost in denial.”

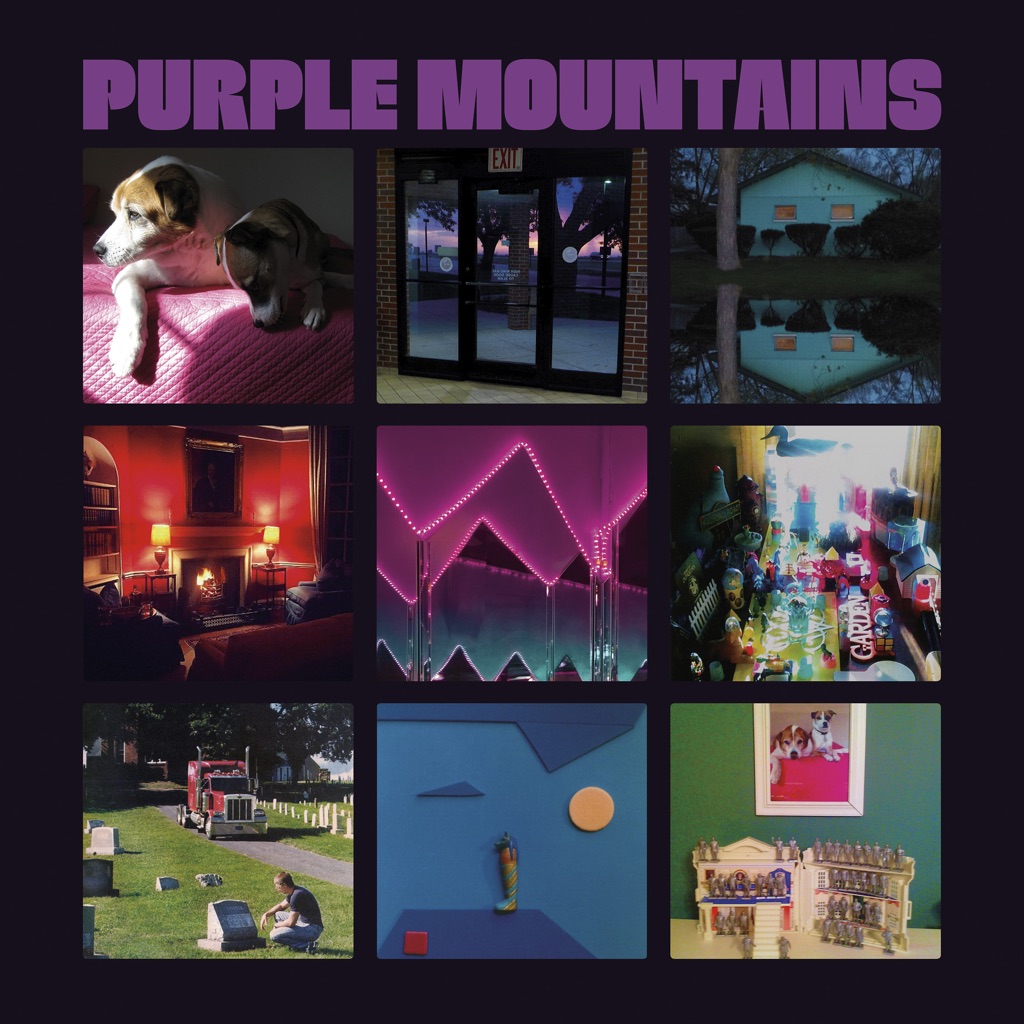

When David Berman disbanded Silver Jews in 2009, the world stood to lose one of the best writers in indie rock, a guy who catalogued the magic and misery of everyday life with wit, heart, and the ragged glory of the occupationally down-and-out. After a 10-year break professedly spent reading books and arguing with people on Reddit, Berman enlisted members of the Brooklyn band Woods to back him on *Purple Mountains*. Berman’s pain had never been laid quite so bare, nor had it ever sounded quite so urgent. “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion,” he sings on the swaggering “That’s Just the Way I Feel.” “Day to day, I’m neck and neck with giving in.” And “Margaritas at the Mall” turns an ordinary happy hour into a jeremiad about the cold comforts of capitalism in a godless world. That the music—country-tinged indie rock—was as polished and competent as it was only highlighted Berman’s intensity: less a rock singer than a street preacher, someone who needed to avail himself of his visions stat. But even at his most desperate, he remained achingly funny, turning statements of existential loneliness into the kind of bumper sticker Zen that made him seem like an ordinary guy no matter how highfalutin he could get. “Well, if no one’s fond of fuckin’ me, maybe no one’s fuckin’ fond of me,” he sings on the album-closing “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” sounding not all that far off from the George Strait one-twos he reportedly loved. Above all, though, his writing is beautiful, attuned to detail in ways that make ordinary scenarios shimmer with quiet magic. Just listen to “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan,” which turns a quiet night in a big city into an allegory of finding solace in the weather of what comes to us. Shortly after the release of *Purple Mountains*, Berman died, at the age of 52, a tragic end to what felt like a triumphant return. “The dead know what they\'re doing when they leave this world behind,” he sings on “Nights That Won’t Happen.” “When the here and the hereafter momentarily align.”

David Berman comes in from the cold after ten long years. His new musical expression is a meltdown unparalleled in modern memory. He warns us that his findings might be candid, but as long as his punishment comes in such bite-sized delights of all-American jukebox fare, we'll hike the Purple Mountains with pleasure forever.

With powerhouse pipes, razor-sharp wit, and a tireless commitment to self-love and self-care, Lizzo is the fearless pop star we needed. Born Melissa Jefferson in Detroit, the singer and classically trained flautist discovered an early gift for music (“It chose me,” she tells Apple Music) and began recording in Minneapolis shortly after high school. But her trademark self-confidence came less naturally. “I had to look deep down inside myself to a really dark place to discover it,” she says. Perhaps that’s why her third album, *Cuz I Love You*, sounds so triumphant, with explosive horns (“Cuz I Love You”), club drums (“Tempo” featuring Missy Elliott), and swaggering diva attitude (“No, I\'m not a snack at all/Look, baby, I’m the whole damn meal,” she howls on the instant hit “Juice\"). But her brand is about more than mic-drop zingers and big-budget features. On songs like “Better in Color”—a stomping, woke plea for people of all stripes to get together—she offers an important message: It’s not enough to love ourselves, we also have to love each other. Read on for Lizzo’s thoughts on each of these blockbuster songs. **“Cuz I Love You”** \"I start every project I do with a big, brassy orchestral moment. And I do mean *moment*. It’s my way of saying, ‘Stand the fuck up, y’all, Lizzo’s here!’ This is just one of those songs that gets you amped from the jump. The moment you hear it, you’re like, ‘Okay, it’s on.’ It’s a great fucking way to start an album.\" **“Like a Girl”** \"We wanted take the old cliché and flip it on its head, shaking out all the negative connotations and replacing them with something empowering. Serena Williams plays like a girl and she’s the greatest athlete on the planet, you know? And what if crying was empowering instead of something that makes you weak? When we got to the bridge, I realized there was an important piece missing: What if you identify as female but aren\'t gender-assigned that at birth? Or what if you\'re male but in touch with your feminine side? What about my gay boys? What about my drag queens? So I decided to say, ‘If you feel like a girl/Then you real like a girl,\' and that\'s my favorite lyric on the whole album.\" **“Juice”** \"If you only listen to one song from *Cuz I Love You*, let it be this. It’s a banger, obviously, but it’s also a state of mind. At the end of the day, I want my music to make people feel good, I want it to help people love themselves. This song is about looking in the mirror, loving what you see, and letting everyone know. It was the second to last song that I wrote for the album, right before ‘Soulmate,\' but to me, this is everything I’m about. I wrote it with Ricky Reed, and he is a genius.” **“Soulmate”** \"I have a relationship with loneliness that is not very healthy, so I’ve been going to therapy to work on it. And I don’t mean loneliness in the \'Oh, I don\'t got a man\' type of loneliness, I mean it more on the depressive side, like an actual manic emotion that I struggle with. One day, I was like, \'I need a song to remind me that I\'m not lonely and to describe the type of person I *want* to be.\' I also wanted a New Orleans bounce song, \'cause you know I grew up listening to DJ Jubilee and twerking in the club. The fact that l got to combine both is wild.” **“Jerome”** \"This was my first song with the X Ambassadors, and \[lead singer\] Sam Harris is something else. It was one of those days where you walk into the studio with no expectations and leave glowing because you did the damn thing. The thing that I love about this song is that it’s modern. It’s about fuccboi love. There aren’t enough songs about that. There are so many songs about fairytale love and unrequited love, but there aren’t a lot of songs about fuccboi love. About when you’re in a situationship. That story needed to be told.” **“Cry Baby”** “This is one of the most musical moments on a very musical album, and it’s got that Minneapolis sound. Plus, it’s almost a power ballad, which I love. The lyrics are a direct anecdote from my life: I was sitting in a car with a guy—in a little red Corvette from the ’80s, and no, it wasn\'t Prince—and I was crying. But it wasn’t because I was sad, it was because I loved him. It was a different field of emotion. The song starts with \'Pull this car over, boy/Don\'t pretend like you don\'t know,’ and that really happened. He pulled the car over and I sat there and cried and told him everything I felt.” **“Tempo”** “‘Tempo\' almost didn\'t make the album, because for so long, I didn’t think it fit. The album has so much guitar and big, brassy instrumentation, but ‘Tempo’ was a club record. I kept it off. When the project was finished and we had a listening session with the label, I played the album straight through. Then, at the end, I asked my team if there were any honorable mentions they thought I should play—and mind you, I had my girls there, we were drinking and dancing—and they said, ‘Tempo! Just play it. Just see how people react.’ So I did. No joke, everybody in the room looked at me like, ‘Are you crazy? If you don\'t put this song on the album, you\'re insane.’ Then we got Missy and the rest is history.” **“Exactly How I Feel”** “Way back when I first started writing the song, I had a line that goes, ‘All my feelings is Gucci.’ I just thought it was funny. Months and months later, I played it at Atlantic \[Records\], and when that part came up, I joked, ‘Thanks for the Gucci feature, guys!\' And this executive says, ‘We can get Gucci if you want.\' And I was like, ‘Well, why the fuck not?\' I love Gucci Mane. In my book, he\'s unproblematic, he does a good job, he adds swag to it. It doesn’t go much deeper than that, to be honest. The rest of the song has plenty of meaning: It’s an ode to being proud of your emotions, not feeling like you have to hide them or fake them, all that. But the Gucci feature was just fun.” **“Better in Color”** “This is the nerdiest song I have ever written, for real. But I love it so much. I wanted to talk about love, attraction, and sex *without* talking about the boxes we put those things in—who we feel like we’re allowed to be in love with, you know? It shouldn’t be about that. It shouldn’t be about gender or sexual orientation or skin color or economic background, because who the fuck cares? Spice it up, man. Love *is* better in color. I don’t want to see love in black and white.\" **“Heaven Help Me”** \"When I made the album, I thought: If Aretha made a rap album, what would that sound like? ‘Heaven Help Me’ is the most Aretha to me. That piano? She would\'ve smashed that. The song is about a person who’s confident and does a good job of self-care—a.k.a. me—but who has a moment of being pissed the fuck off and goes back to their defensive ways. It’s a journey through the full spectrum of my romantic emotions. It starts out like, \'I\'m too cute for you, boo, get the fuck away from me,’ to \'What\'s wrong with me? Why do I drive boys away?’ And then, finally, vulnerability, like, \'I\'m crying and I\'ve been thinking about you.’ I always say, if anyone wants to date me, they just gotta listen to this song to know what they’re getting into.\" **“Lingerie”** “I’ve never really written sexy songs before, so this was new for me. The lyrics literally made me blush. I had to just let go and let God. It’s about one of my fantasies, and it has three different chord changes, so let me tell you, it was not easy to sing. It was very ‘Love On Top’ by Beyoncé of me. Plus, you don’t expect the album to end on this note. It leaves you wanting more.”

My new album ’M for Empathy' is mostly things said or shoulda said, heard or shoulda. Much of it, and it's just a lil, came to me, or outta me, outta a deepening silence. Something you can hear a lot of I hope. It let me voice again. It also let me not, and only sing as much as I wanted, which is important too. Making peace with the word in me, just a lil, all my might. xo, Hannah

“How people may emotionally connect with music I’ve been involved in is something that part of me is completely mystified by,” Thom Yorke tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “Human beings are really different, so why would it be that what I do connects in that way? I discovered maybe around \[Radiohead\'s album\] *The Bends* that the bit I didn’t want to show, the vulnerable bit… that bit was the bit that mattered.” *ANIMA*, Yorke’s third solo album, further weaponizes that discovery. Obsessed by anxiety and dystopia, it might be the most disarmingly personal music of a career not short of anxiety and dystopia. “Dawn Chorus” feels like the centerpiece: It\'s stop-you-in-your-tracks beautiful with a claustrophobic “stream of consciousness” lyric that feels something like a slowly descending panic attack. And, as Yorke describes, it was the record\'s biggest challenge. “There’s a hit I have to get out of it,” he says. “I was trying to develop how ‘Dawn Chorus’ was going to work, and find the right combinations on the synthesizers I was using. Couldn’t find it, tried it again and again and again. But I knew when I found it I would have my way into the song. Things like that matter to me—they are sort of obsessive, but there is an emotional connection. I was deliberately trying to find something as cold as possible to go with it, like I sing essentially one note all the way through.” Yorke and longtime collaborator Nigel Godrich (“I think most artists, if they\'re honest, are never solo artists,” Yorke says) continue to transfuse raw feeling into the album’s chilling electronica. “Traffic,” with its jagged beats and “I can’t breathe” refrain, feels like a partner track to another memorable Yorke album opener, “Everything in Its Right Place.” The extraordinary “Not the News,” meanwhile, slaloms through bleeps and baleful strings to reach a thunderous final destination. It’s the work of a modern icon still engaged with his unique gift. “My cliché thing I always say is, \'You know you\'re in trouble when people stop listening to sad music,\'” Yorke says. “Because the moment people stop listening to sad music, they don\'t want to know anymore. They\'re turning themselves off.”

Over the decade-plus since he arrived seemingly fully formed as the platonic ideal of indie DIY made good, Justin Vernon has pushed back against the notion that he and Bon Iver are synonymous. He is quick to deflect credit to core longtime collaborators like Chris Messina and Brad Cook, while April Base, the studio and headquarters he built just outside his native Eau Claire, Wisconsin, has become a cultural hub playing host to a variety of experimental projects. The fourth Bon Iver full-length album shines a brighter light on Bon Iver as a unit with many moving parts: Renovations to April Base sent operations to Sonic Ranch in Tornillo, Texas, for much of the production, but the spirit of improvisation and tinkering and revolving-door personnel that marked 2016’s out-there *22, A Million* remained intact. “This record in particular felt like a very outward record; Justin felt outward to me,” says Cook, who grew up with Vernon and has played with him through much of his career. “He felt like he was in a new place, and he was reaching out for new input in a different way. We\'re just more in the foreground inevitably because the process became just a little bit more transparent.” Vernon, Cook, and Messina talk through that process on each of *i,i*\'s 13 tracks. **“Yi”** Justin Vernon: “That was a phone recording of me and my friend Trevor screwing around in a barn, turning a radio on and off. We chopped it up for about five years, just a hundred times. There’s something in that ‘Are you recording? Are you recording?’ that felt like the spirit that flows into the next song.” **“iMi”** Brad Cook: “It was like an old friend that you didn\'t know what to do with for a long time. When we got to Texas, a lot of different people took a crack at trying to make something out of that song. And then Andrew Sarlo, who works with Big Thief and is just a badass young producer, he took the whack that broke through the wall. Once the band got their hands on it, Justin added some of the acoustic stuff to it, and it just totally blew it wide open.” **“We”** Vernon: “I was working on this idea one morning with this engineer, Josh Berg, who happened to be out with us. And this guy Bobby Raps from Minneapolis was also at my studio just kind of hanging around, and he brought this dude named Wheezy who does some Young Thug beats, some Future beats. So I had this little baritone-guitar bass loop thing, and Wheezy put his beat on there. All these songs had a life, or had a birth, before Texas, but Texas was like graduation for every single one. That\'s why we went for so long and allowed for so much perspective to sink into all the tunes. It\'s a fucking banger; I love that one.” **“Holyfields,”** Vernon: “The whole song is an improvised moment with barely any editing, and we just improv\'d moves. I sang some scratch vocals that day when we made it up, and they were weirdly close to what ended up being on the album. We didn\'t really chop away at that one—it kind of just was born with all its hair and everything.” **“Hey, Ma”** Vernon: “It just felt like a good strong song; we knew people would get it in their head. A couple of these tunes, and some of the tunes from the last album, I sort of peck around the studio with BJ Burton from time to time, and 90 percent of the stuff we make is death techno or something. So, there\'s another one that sort of just hung around with a stake in the ground, so to speak. And then our team—the three of us and the rest of everyone—just kept etching away at it, and it ended up becoming the song that felt emblematic of the record.” **\"U (Man Like)\"** Cook: “We had Bruce \[Hornsby\] come out to Justin\'s studio for a session for his *Absolute Zero* record. Bruce was playing a bunch of musical ideas that he had just sort of done at his house, and that piano figure in that song—I feel like we were tracking 15 seconds later. It was like, \'Wait, can we listen to this again?\'” Vernon: “I\'m not so good at coming up with full songs on the spot, but I can kind of map them out with my voice, or inflection. Then it takes a long time to chip away at them. Messina might have an idea for what that line should be, or Brad, or me. The melody that I sang that first day probably sounds remarkably like the melody that\'s on the album.” **“Naeem”** Vernon: “We did a collaboration with a dance group called TU Dance, and that was one of the songs. So we\'ve been performing \'Naeem\' as a part of this thing for a while. It\'s in a different state, but it\'s the finale of this big collaboration. And it just seemed very anthemic, and a very important part of whatever this record was going to be. It feels really nice to have a little bit more straightforward—not always bombastic, not always sonically trying to flip your lid or something.” **“Jelmore”** Vernon: “Basically an improvisation with me and this guy Buddy Ross. Again I probably didn\'t sing any final lyrics, but it\'s based on an improvisation, much like the song \'\_\_\_\_45\_\_\_\_\_\' from \[*22, A Million*\]. And when we were down outside El Paso, me and Chris were over on one part of this studio and Brad was with the band in a big studio across the property, and they sort of took \'Jelmore\' upon themselves and filled it in with all the lovely live-ness that\'s there. As the record goes on, it feels like there\'s a lot of these things that are sort of bare but have a lot of live energy to them.” **“Faith”** Vernon: “A basement improv that sat around for many years; maybe could have been on the last album, was for a while. I don\'t know, man—it\'s a song about having faith.” **“Marion”** Chris Messina: “I think that\'s one that Justin\'s been noodling around with for a while; for a few years, he would pick up that guitar and you would just kind of hear that riff. And we didn\'t really know what was going to happen to it. It\'s another one that exists in the TU Dance show. But what\'s cool about the version that\'s on the record is we did that as a live take with a six-piece ensemble that Rob Moose wrote for and conducted, and it was saxophone, trombone, trumpet, French horn, harmonica, and I think that\'s it that we did live. And then Justin was singing live and playing guitar live.” **“Salem”** Vernon: “OP-1 loop, weird Indigo Girls/Rickie Lee Jones vibes. I got really into acid and the Grateful Dead this year, so there\'s definitely some early psych vibes in there. The record really is supposed to be thought of as the fall record for this band, if you think of the other ones as seasons. Salem and burning leaves—these longings and these deaths, it\'s very much in there in that song, so it\'s a really autumn-y song.” **“Sh’Diah”** Vernon: “It stands for Shittiest Day in American History—the day after Trump got elected. It\'s another that sort of hung around as an improvised idea, and we finally got to figure out where we\'re going to land Mike Lewis, our favorite instrumentalist alive today in music. He gets to play over it, and the band got to do all this crazy layering over it. It\'s just one of my favorite moods on the album.” **“RABi”** Messina: “Justin\'s singing a cool thing on it, the guitar vibe is comforting and persistent, but we just weren\'t really sure where it needed to go. And then Brad and the rest of the dudes got their hands on it and it came back as just a dream sequence; it was so sick. We all kind of heard it and it was like, whoa, how can this not close out the record? This is definitely \'see you later.\'” Vernon: “Just some ‘life feels good now, don\'t it?\' There\'s a lot to be sad about, there\'s a lot to be confused about, there\'s a lot to be thankful for. And leaning on gratitude and appreciation of the people around you that make you who you are, make you feel safe, and provide that shelter so you can be who you want to be, there\'s still that impetus in life. We need that. It\'s a nice way to close the record, we all thought.”

2020 is the sixth solo album from Richard Dawson, the black-humoured bard of Newcastle. The album is an utterly contemporary state-of-the-nation study that uncovers a tumultuous and bleak time. Here is an island country in a state of flux; a society on the edge of mental meltdown.

slowthai knew the title of his album long before he wrote a single bar of it. He knew he wanted the record to speak candidly about his upbringing on the council estates of Northampton, and for it to advocate for community in a country increasingly mired in fear and insularity. Three years since the phrase first appeared in his breakout track ‘Jiggle’, Tyron Frampton presents his incendiary debut ‘Nothing Great About Britain’. Harnessing the experiences of his challenging upbringing, slowthai doesn’t dwell in self-pity. From the album’s title track he sets about systematically dismantling the stereotypes of British culture, bating the Royals and lampooning the jingoistic bluster that has ultimately led to Brexit and a surge in nationalism. “Tea, biscuits, the roads: everything we associate with being British isn’t British,” he cries today. “What’s so great about Britain? The fact we were an empire based off of raping and pillaging and killing, and taking other people’s culture and making it our own?” ‘Nothing Great About Britain’ serves up a succession of candid snapshots of modern day British life; drugs, disaffection, depression and the threat of violence all loom in slowthai’s visceral verses, but so too does hope, love and defiance. Standing alongside righteous anger and hard truths, it’s this willingness to appear vulnerable that makes slowthai such a compelling storyteller, and this debut a vital cultural document, testament to the healing power of music. As slowthai himself explains, “Music to me is the biggest connector of people. It don’t matter what social circle you’re from, it bonds people across divides. And that’s why I do music: to bridge the gap and bring people together.”

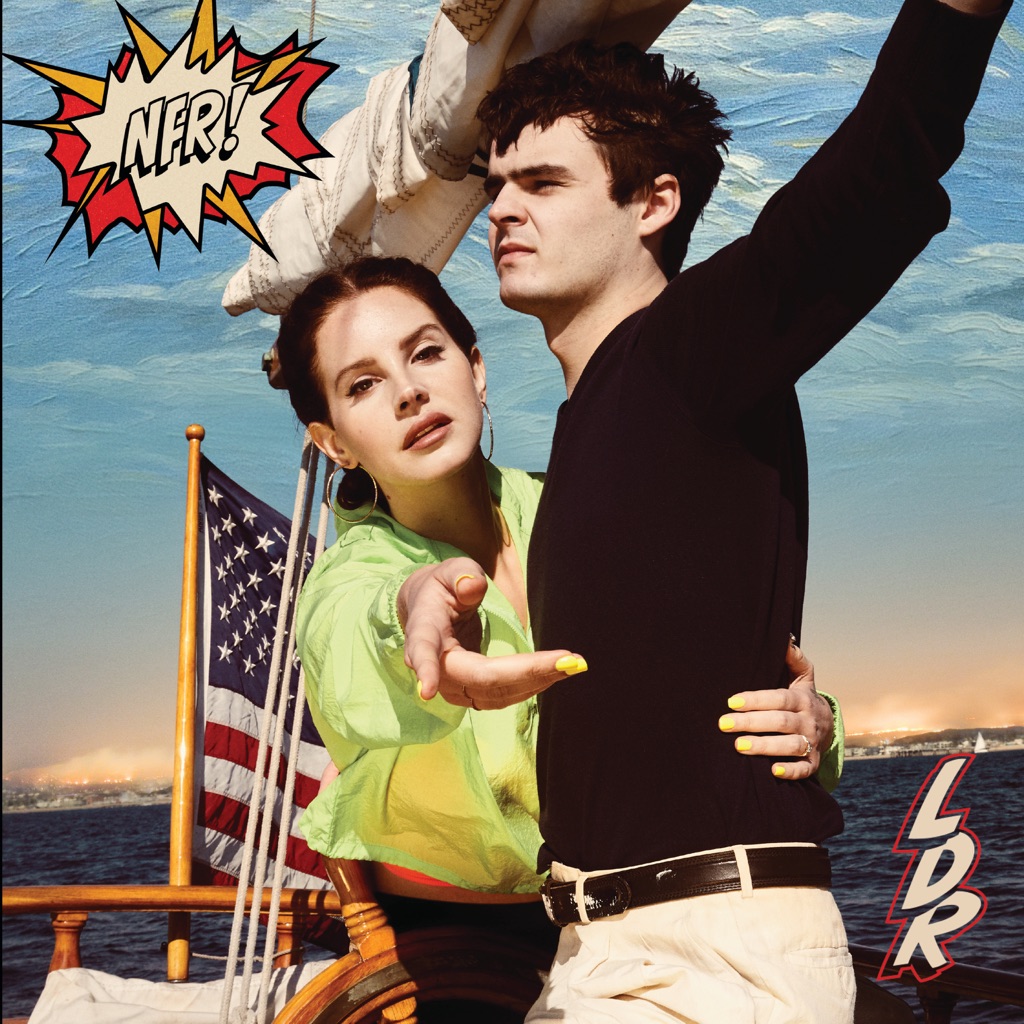

Part of the fun of listening to Lana Del Rey’s ethereal lullabies is the sly sense of humor that brings them back down to earth. Tucked inside her dreamscapes about Hollywood and the Hamptons are reminders—and celebrations—of just how empty these places can be. Here, on her sixth album, she fixes her gaze on another place primed for exploration: the art world. Winking and vivid, *Norman F\*\*\*\*\*g Rockwell!* is a conceptual riff on the rules that govern integrity and authenticity from an artist who has made a career out of breaking them. In a 2018 interview with Apple Music\'s Zane Lowe, Del Rey said working with songwriter Jack Antonoff (who produced the album along with Rick Nowels and Andrew Watt) put her in a lighter mood: “He was so *funny*,” she said. Their partnership—as seen on the title track, a study of inflated egos—allowed her to take her subjects less seriously. \"It\'s about this guy who is such a genius artist, but he thinks he’s the shit and he knows it,” she said. \"So often I end up with these creative types. They just go on and on about themselves and I\'m like, \'Yeah, yeah.\' But there’s merit to it also—they are so good.” This paradox becomes a theme on *Rockwell*, a canvas upon which she paints with sincerity and satire and challenges you to spot the difference. (On “The Next Best American Record,” she sings, “We were so obsessed with writing the next best American record/’Cause we were just that good/It was just that good.”) Whether she’s wistfully nostalgic or jaded and detached is up for interpretation—really, everything is. The album’s finale, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have - but I have it,” is packaged like a confessional—first-person, reflective, sung over simple piano chords—but it’s also flamboyantly cinematic, interweaving references to Sylvia Plath and Slim Aarons with anecdotes from Del Rey\'s own life to make us question, again, what\'s real. When she repeats the phrase “a woman like me,” it feels like a taunt; she’s spent the last decade mixing personas—outcast and pop idol, debutante and witch, pinup girl and poet, sinner and saint—ostensibly in an effort to render them all moot. Here, she suggests something even bolder: that the only thing more dangerous than a complicated woman is one who refuses to give up.

Beginning with the haunting alt-pop smash “Ocean Eyes” in 2016, Billie Eilish made it clear she was a new kind of pop star—an overtly awkward introvert who favors chilling melodies, moody beats, creepy videos, and a teasing crudeness à la Tyler, The Creator. Now 17, the Los Angeles native—who was homeschooled along with her brother and co-writer, Finneas O’Connell—presents her much-anticipated debut album, a melancholy investigation of all the dark and mysterious spaces that linger in the back of our minds. Sinister dance beats unfold into chattering dialogue from *The Office* on “my strange addiction,” and whispering vocals are laid over deliberately blown-out bass on “xanny.” “There are a lot of firsts,” says FINNEAS. “Not firsts like ‘Here’s the first song we made with this kind of beat,’ but firsts like Billie saying, ‘I feel in love for the first time.’ You have a million chances to make an album you\'re proud of, but to write the song about falling in love for the first time? You only get one shot at that.” Billie, who is both beleaguered and fascinated by night terrors and sleep paralysis, has a complicated relationship with her subconscious. “I’m the monster under the bed, I’m my own worst enemy,” she told Beats 1 host Zane Lowe during an interview in Paris. “It’s not that the whole album is a bad dream, it’s just… surreal.” With an endearingly off-kilter mix of teen angst and experimentalism, Billie Eilish is really the perfect star for 2019—and here is where her and FINNEAS\' heads are at as they prepare for the next phase of her plan for pop domination. “This is my child,” she says, “and you get to hold it while it throws up on you.” **Figuring out her dreams:** **Billie:** “Every song on the album is something that happens when you’re asleep—sleep paralysis, night terrors, nightmares, lucid dreams. All things that don\'t have an explanation. Absolutely nobody knows. I\'ve always had really bad night terrors and sleep paralysis, and all my dreams are lucid, so I can control them—I know that I\'m dreaming when I\'m dreaming. Sometimes the thing from my dream happens the next day and it\'s so weird. The album isn’t me saying, \'I dreamed that\'—it’s the feeling.” **Getting out of her own head:** **Billie:** “There\'s a lot of lying on purpose. And it\'s not like how rappers lie in their music because they think it sounds dope. It\'s more like making a character out of yourself. I wrote the song \'8\' from the perspective of somebody who I hurt. When people hear that song, they\'re like, \'Oh, poor baby Billie, she\'s so hurt.\' But really I was just a dickhead for a minute and the only way I could deal with it was to stop and put myself in that person\'s place.” **Being a teen nihilist role model:** **Billie:** “I love meeting these kids, they just don\'t give a fuck. And they say they don\'t give a fuck *because of me*, which is a feeling I can\'t even describe. But it\'s not like they don\'t give a fuck about people or love or taking care of yourself. It\'s that you don\'t have to fit into anything, because we all die, eventually. No one\'s going to remember you one day—it could be hundreds of years or it could be one year, it doesn\'t matter—but anything you do, and anything anyone does to you, won\'t matter one day. So it\'s like, why the fuck try to be something you\'re not?” **Embracing sadness:** **Billie:** “Depression has sort of controlled everything in my life. My whole life I’ve always been a melancholy person. That’s my default.” FINNEAS: “There are moments of profound joy, and Billie and I share a lot of them, but when our motor’s off, it’s like we’re rolling downhill. But I’m so proud that we haven’t shied away from songs about self-loathing, insecurity, and frustration. Because we feel that way, for sure. When you’ve supplied empathy for people, I think you’ve achieved something in music.” **Staying present:** **Billie:** “I have to just sit back and actually look at what\'s going on. Our show in Stockholm was one of the most peak life experiences we\'ve had. I stood onstage and just looked at the crowd—they were just screaming and they didn’t stop—and told them, \'I used to sit in my living room and cry because I wanted to do this.\' I never thought in a thousand years this shit would happen. We’ve really been choking up at every show.” FINNEAS: “Every show feels like the final show. They feel like a farewell tour. And in a weird way it kind of is, because, although it\'s the birth of the album, it’s the end of the episode.”

Warmduscher return. Heavy metals. Disco Peanuts. CCTV in the break room. A little something to get you through the week. There’s enough to go around. Revenge is a dish best served bold. Melt in the mouth disco basslines on a fragrant bed of feedback. Try it with the boom bap tapenade. Here for a good time, not a long time. If you made your way out of Whale City with your faculties intact, this one’s for you. Clams Baker, Lightnin’ Jack Everett, Mr Salt Fingers Lovecraft and The Witherer have been joined by Quicksand on cutting board and cheese wire and commis chef Cheeks on vibes. They’ve been cooking. Michelin stars. The finest ingredients money can buy: Kool Keith and Iggy Pop. Funk, punk, hip-hop and lounge rock. Love is real. Band biographer and revered botanist Dr Alan Goldfarb describes the album as “a sample hole through which to taste another universe. A dramatic warning. A gilded aroma. It is a tale of wanton desire and limitless treachery. A tale of disillusionment – the refusal of exploitation.” If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.

Sam Shepherd aka Floating Points has announced his new album Crush will be released on 18 October on Ninja Tune. Along with the announcement he has shared new track 'Last Bloom' along with accompanying video by Hamill Industries and announced details of a new live show with dates including London's Printworks, his biggest headline live show to date. The best musical mavericks never sit still for long. They mutate and morph into new shapes, refusing to be boxed in. Floating Points has so many guises that it’s not easy to pin him down. There’s the composer whose 2015 debut album Elaenia was met with rave reviews – including being named Pitchfork’s ‘Best New Music’ and Resident Advisor’s ‘Album of the Year’ – and took him from dancefloors to festival stages worldwide. The curator whose record labels have brought soulful new sounds into the club, and, on his esteemed imprint Melodies International, reinstated old ones. The classicist, the disco guy that makes machine music, the digger always searching for untapped gems to re-release. And then there’s the DJ whose liberal approach to genre saw him once drop a 20-minute instrumental by spiritual saxophonist Pharoah Sanders in Berghain. Fresh from the release earlier this year of his compilation of lambent, analogous ambient and atmospheric music for the esteemed Late Night Tales compilation series, Floating Points’ first album in four years, Crush, twists whatever you think you know about him on its head again. A tempestuous blast of electronic experimentalism whose title alludes to the pressure-cooker of the current environment we find ourselves in. As a result, Shepherd has made some of his heaviest, most propulsive tracks yet, nodding to the UK bass scene he emerged from in the late 2000s, such as the dystopian low-end bounce of previously shared striking lead single ‘LesAlpx’ (Pitchfork’s ‘Best New Track’), but there are also some of his most expressive songs on Crush: his signature melancholia is there in the album’s sublime mellower moments or in the Buchla synthesizer, whose eerie modulation haunts the album. Whereas Elaenia was a five-year process, Crush was made during an intense five-week period, inspired by the invigorating improvisation of his shows supporting The xx in 2017. He had just finished touring with his own live ensemble, culminating in a Coachella appearance, when he suddenly became a one-man band, just him and his trusty Buchla opening up for half an hour every night. He thought what he’d come out with would "be really melodic and slow- building" to suit the mood of the headliners, but what he ended up playing was "some of the most obtuse and aggressive music I've ever made, in front of 20,000 people every night," he says. "It was liberating." His new album feels similarly instantaneous – and vital. It’s the sound of the many sides of Floating Points finally fusing together. It draws from the "explosive" moments during his sets, the moments that usually occur when he throws together unexpected genres, for the very simple reason that he gets excited about wanting to "hear this record, really loud, now!" and then puts the needle on. It’s "just like what happens when you’re at home playing music with your friends and it's going all over the place," he says. Today's newly announced live solo shows capture that energy too, so that the audience can see that what they’re watching isn’t just someone pressing play. Once again Shepherd has teamed up with Hamill Industries, the duo who brought their ground-breaking reactive laser technologies to his previous tours. Their vision is to create a constant dialogue between the music and the visuals. This time their visuals will zoom in on the natural world, where landscapes are responsive to the music and flowers or rainbow swirls of bubbles might move and morph to the kick of the bass drum. What you see on the screen behind Shepherd might "look like a cosmos of colour going on," says Shepherd, "but it’s actually a tiny bubble with a macro lens on it being moved by frequencies by my Buchla," which was also the process by which the LP artwork was made." It means, he adds, "putting a lot of Fairy Liquid on our tour rider".

In 2016’s *Private Energy*, Roberto Carlos Lange, a.k.a. Helado Negro, celebrated his identity while highlighting themes like racially targeted enforcement and gender fluidity. The Brooklyn-based singer-producer’s follow-up, *This Is How You Smile*, allows him to wind down and find his center. *Smile* is by turns more self-reflective, a vivid reverie of personal memories bedded in delicate acoustic strums and atmospheric dreamscapes. Lange\'s articulate, compassionate voice softens the album\'s dense arrangements (which are interspersed with field recordings and ambient interludes). On “País Nublado,” a balmy bossa nova groove ambles against Lange’s pithy haikus. Serene piano strokes lead the way over his soulful, whispered baritone on both “Running” and “Please Won’t Please.” “Seen My Aura” is more effervescent by comparison, but just as chill—a lysergic funk jam where Lange’s naturalistobservations take flight.

Helado Negro returns with This Is How You Smile, an album that freely flickers between clarity and obscurity, past and present geographies, bright and unhurried seasons. Miami-born, New York-based artist Roberto Carlos Lange embraces a personal and universal exploration of aura – seen, felt, emitted – on his sixth album and second for RVNG Intl.

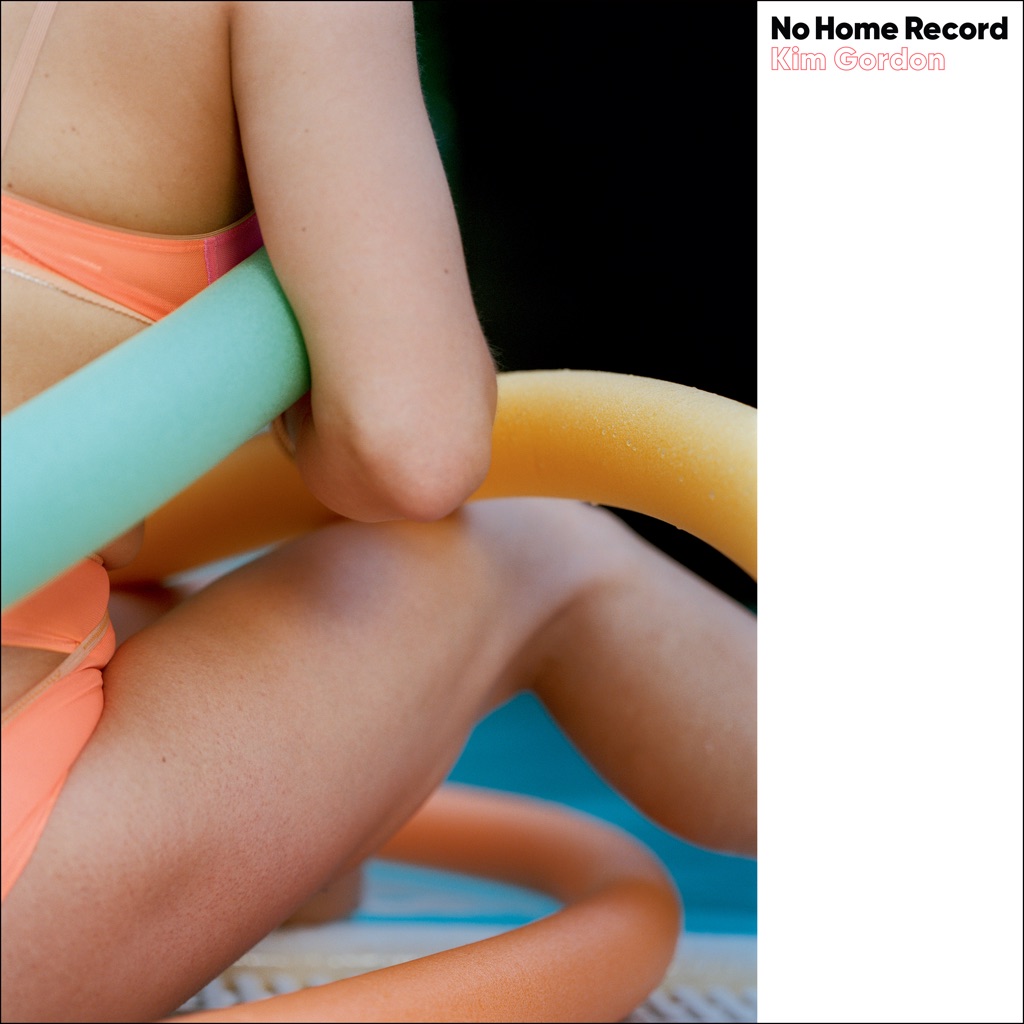

You’d think that an artist making her first solo album after nearly 40 years of collaborative work would fall for at least a few pitfalls of sentimentality—the glance in the rearview, the meditation on middle age, the warmth of accomplishment, whatever. Then again, Kim Gordon was never much for soft landings. Noisy, vibrant, and alive with the kind of fragmented poetry that made her presence in Sonic Youth so special, *No Home Record* feels, above all, like a debut—a new voice clocking in for the first time, testing waters, stretching her capacity. The wit is classic (“Airbnb/Could set me free!” she wails on “Air BnB,” channeling the misplaced passions of understimulated yuppies worldwide), as is the vacant sex appeal (“Touch your nipple/You’re so fine!” she wails on “Hungry Baby,” channeling the…misplaced passions of understimulated yuppies worldwide). Most surprising is how informed the album is by electronic music (“Don’t Play It”) and hip-hop (“Paprika Pony,” “Sketch Artist”)—a shift that breaks with the free-rock-saviordom that Sonic Youth always represented while maintaining the continuity of experimentation that made Gordon a pioneer in the first place.

With a career spanning nearly four decades, Kim Gordon is one of the most prolific and visionary artists working today. A co-founder of the legendary Sonic Youth, Gordon has performed all over the world, collaborating with many of music’s most exciting figures including Tony Conrad, Ikue Mori, Julie Cafritz and Stephen Malkmus. Most recently, Gordon has been hitting the road with Body/Head, her spellbinding partnership with artist and musician Bill Nace. Despite the exhaustive nature of her résumé, the most reliable aspect of Gordon’s music may be its resistance to formula. Songs discover themselves as they unspool, each one performing a test of the medium’s possibilities and limits. Her command is astonishing, but Gordon’s artistic curiosity remains the guiding force behind her music. It makes sense that this “American idea” (as Gordon says on the agitated rock track “Air BnB”) of purchasing utopia permeates the record, as no place is this phenomenon more apparent than Los Angeles, where Gordon was born and recently returned to after several lifetimes on the east coast. It was a move precipitated by a number of seismic shifts in her personal life and undoubtedly plays a role in No Home Record’s fascination with transience. The album opens with the restless “Sketch Artist,” where Gordon sings about “dreaming in a tent” as the music shutters and skips like scenery through a car window. “Even Earthquake,” perhaps the record’s most straightforward track embodies this mood; Gordon’s voice wavering like watercolor: “If I could cry and shake for you / I’d lay awake for you / I got sand in my heart for you,” guitar strokes blending into one another as they bleed out across an unstable page. Front to back, No Home Record is an expert operation in the uncanny. You don’t simply listen to Gordon’s music; you experience it.

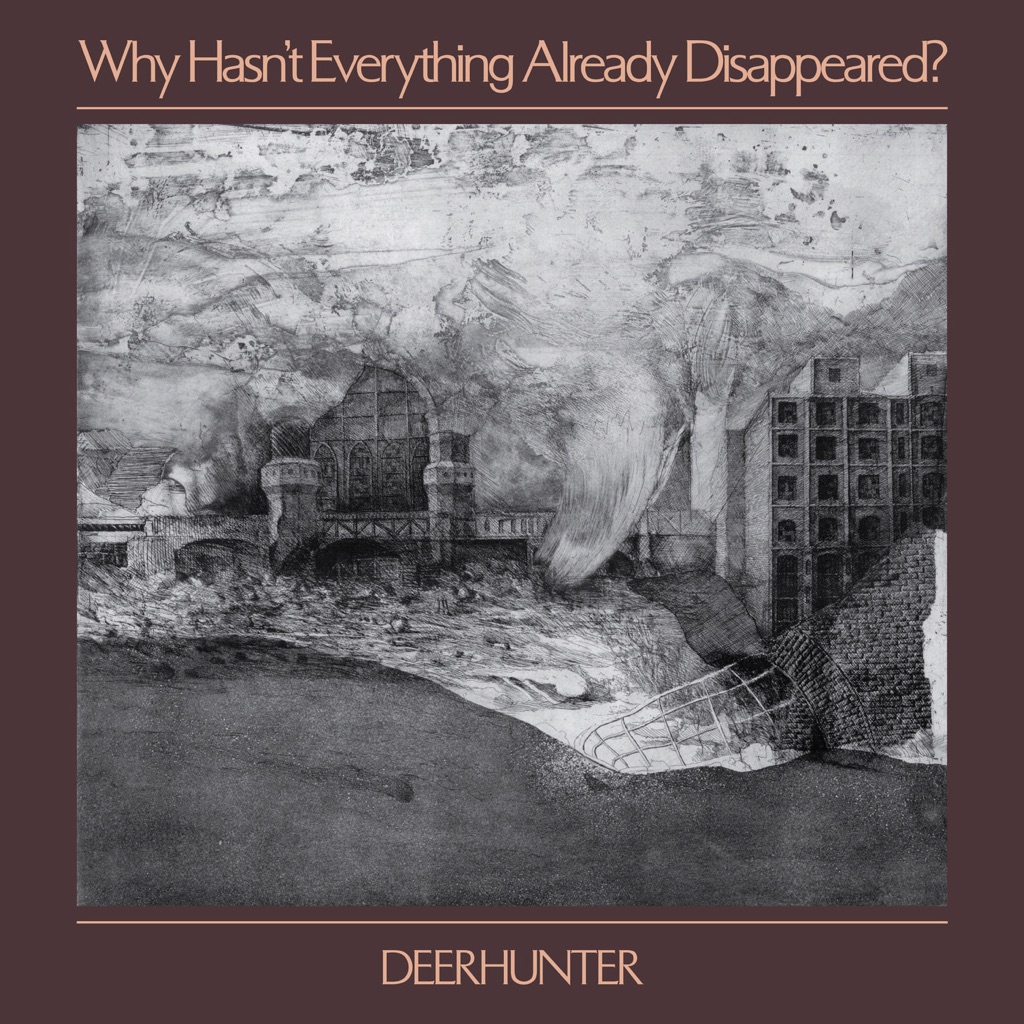

The Atlanta band’s eighth full-length finds iconoclastic frontman Bradford Cox and co. shrinking their typically ambient-focused sound, with relatively compact guitar-pop gems alongside haunting, weightless-sounding instrumentals. Featuring contributions from Welsh singer-songwriter Cate Le Bon and Tim Presley of garage-popsters White Fence, *Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?* diverges from the deeply personal themes of previous Deerhunter albums, zeroing in on topics ranging from James Dean (“Plains”) to the tragic murder of British politician Jo Cox (“No One’s Sleeping”)—but the spectral vocals and penchant for left-field sounds are well accounted for, as the album represents the latest strange chapter in one of modern indie rock’s most consistently surprising acts.

Look past its futurist textures and careful obfuscations, and there’s something deeply human about FKA twigs’ 21st-century R&B. On her second full-length, the 31-year-old British singer-songwriter connects our current climate to that of Mary Magdalene, a healer whose close personal relationship with Christ brought her scorn from those who would ultimately write her story: men. “I\'m of a generation that was brought up without options in love,” she tells Apple Music. “I was told that as a woman, I should be looked after. It\'s not whether I choose somebody, but whether somebody chooses me.” Written and produced by twigs, with major contributions from Nicolas Jaar, *MAGDALENE* is a feminist meditation on the ways in which we relate to one another and ourselves—emotionally, sexually, universally—set to sounds that are at once modern and ancient. “Now it’s like, ‘Can you stand up in my holy terrain?’” she says, referencing the titular lyric from her mid-album collaboration with Future. “‘How are we going to be equals in this? Spiritually, am I growing? Do you make me want to be a better person?’ I’m definitely still figuring it out.” Here, she walks us through the album track by track. **thousand eyes** “All the songs I write are autobiographical. Anyone that\'s been in a relationship for a long time, you\'re meshed together. But unmeshing is painful, because you have the same friends or your families know each other. No matter who you are, the idea of leaving is not only a heart trauma, but it\'s also a social trauma, because all of a sudden, you don\'t all go to that pub that you went to together. The line \[\'If I walk out the door/A thousand eyes\'\] is a reference to that. At the time, I was listening to a lot of Gregorian music. I’d started really getting into medieval chords before that, and I\'d found some musicians that play medieval music and done a couple sessions with them. Even on \[2014\'s\] *LP1*, I had ‘Closer,’ which is essentially a hymn. I spent a lot of time in choir as a child and I went to Sunday school, so it’s part of who I am at this stage.” **home with you** “I find things like that interesting in the studio, just to play around and bring together two completely different genres—like Elton John chords and a hip-hop riff. That’s what ‘home with you’ was for me: It’s a ballad and it\'s sad, but then it\'s a bop as well, even though it doesn\'t quite ever give you what you need. It’s about feeling pulled in all directions: as a daughter, or as a friend, or as a girlfriend, or as a lover. Everyone wanting a piece of you, but not expressing it properly, so you feel like you\'re not meeting the mark.” **sad day** “It’s like, ‘Will you take another chance with me? Can we escape the mundane? Can we escape the cyclical motion of life and be in love together and try something that\'s dangerous and exhilarating? Yeah, I know I’ve made you sad before, but will you give me another chance?\' I wrote this song with benny blanco and Koreless. I love to set myself challenges, and it was really exciting to me, the challenge of retaining my sound while working with a really broad group of people. I was lucky working with Benny, in the fact that he creates an environment where, as an artist, you feel really comfortable to be yourself. To me, that\'s almost the old-school definition of a producer: They don\'t have to be all up in your grill, telling you what to do. They just need to lay a really beautiful, fertile soil, so that you can grow to be the best you in the moment.” **holy terrain** “I’m saying that I want to find a man that can stand up next to me, in all of my brilliance, and not feel intimidated. To me, Future’s saying, ‘Hey, I fucked up. I filled you with poison. I’ve done things to make you jealous. Can you heal me? Can you tell me how to be a better man? I need the guidance, of a woman, to show me how to do that.’ I don\'t think that there are many rappers that can go there, and just put their cards on the table like that. I didn\'t know 100%, once I met Future, that it would be right. But we spoke on the phone and I played him the album and I told him what it was about: ‘It’s a very female-positive, femme-positive record.’ And he was just like, ‘Yeah. Say no more. I\'ve got this.’ And he did. He crushed it. To have somebody who\'s got patriarchal energy come through and say that, wanting to stand up and be there for a woman, wanting to have a woman that\'s an equal—that\'s real.” **mary magdalene** “Let’s just imagine for one second: Say Jesus and Mary Magdalene are really close, they\'re together all the time. She\'s his right-hand woman, she’s his confidante, she\'s healing people with him and a mystic in her own right. So, at that point, any man and woman that are spending that much time together, they\'re likely to be what? Lovers. Okay, cool. So, if Mary had Jesus\' children, that basically debunks the whole of history. Now, I\'m not saying that happened. What I\'m saying is that the idea of people thinking that might happen is potentially really dangerous. It’s easier to call her a whore, because as soon as you call a woman a whore, it devalues her. I see her as Jesus Christ\'s equal. She’s a male projection and, I think, the beginning of the patriarchy taking control of the narrative of women. Any woman that\'s done anything can be subject to that; I’ve been subject to that. It felt like an apt time to be talking about it.” **fallen alien** “When you\'re with someone, and they\'re sleeping, and you look at them, and you just think, \'No.\' For me, it’s that line, \[\'When the lights are on, I know you/When you fall asleep, I’ll kick you down/By the way you fell, I know you/Now you’re on your knees\'\]. You\'re just so sick of somebody\'s bullshit, you\'re just taking it all day, and then you\'re in bed next to them, and you\'re just like, ‘I can\'t take this anymore.’” **mirrored heart** “People always say, ‘Whoever you\'re with, they should be a reflection of yourself.’ So, if you\'re looking at someone and you think, ‘You\'re a shitbag,’ then you have to think about why it was that person, at that time, and what\'s connecting you both. What is the reflection? For others that have found a love that is a true reflection of themselves, they just remind me that I don\'t have that, a mirrored heart.” **daybed** “Have you ever forgotten how to spell a really simple word? To me, depression\'s a bit like that: Everything\'s quite abstract, and even slightly dizzy, but not in a happy way. It\'s like a very slow circus. Suddenly the fruit flies seem friendly, everything in the room just starts having a different meaning and you even have a different relationship with the way the sofa cushions smell. \[Masturbation\] is something to raise your endorphins, isn\'t it? It’s either that or try and go to the gym, or try and eat something good. You almost can\'t put it into words, but we\'ve all been there. I sing, \'Active are my fingers/Faux, my cunnilingus\': You\'re imagining someone going down on you, but they\'re actually not. You open your eyes, and you\'re just there, still on your sofa, still watching daytime TV.” **cellophane** “It\'s just raw, isn\'t it? It didn\'t need a thing. The vocal take that\'s on the record is the demo take. I had a Lyft arrive outside the studio and I’d just started playing the piano chords. I was like, ‘Hey, can you just give me like 20, 25 minutes?’ And I recorded it as is. I remember feeling like I wanted to cry, but I just didn\'t feel like it was that suitable to cry at a studio session. I often want everything to be really intricate and gilded, and I want to chip away at everything, and sculpt it, and mold it, and add layers. The thing I\'ve learned on *MAGDALENE* is that you don\'t need to do that all the time, and just because you can do something, it doesn\'t mean you should. That\'s been a real growing experience for me—as a musician, as a producer, as a singer, even as a dancer. Something in its most simple form is beautiful.”

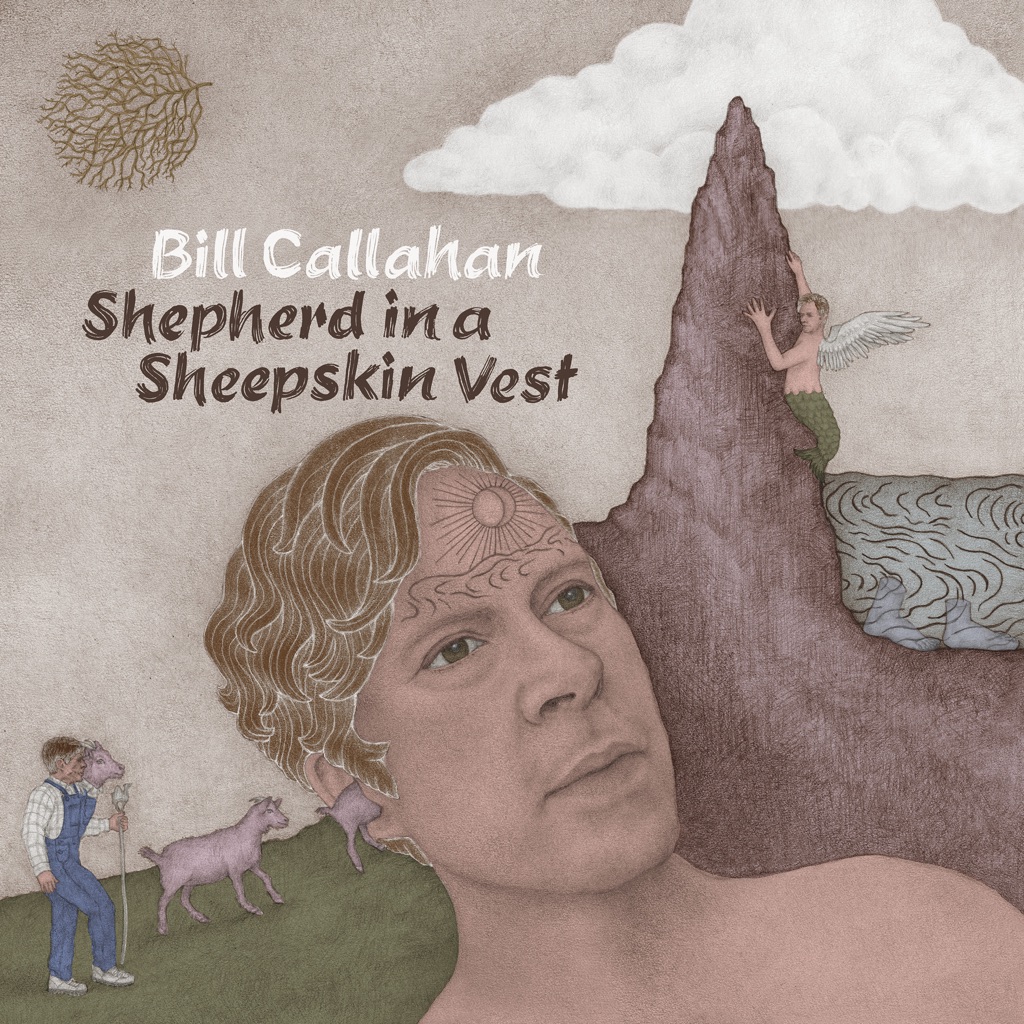

Few songwriters have Bill Callahan’s eye for wry detail: “Like motel curtains, we never really met,” the singer-songwriter declares on “Angela,” using his weather-worn baritone. On his first studio album in five years—an unusually long gap for Callahan—one of the enduring voices in alternative music continues to pare back the extraneous in his sound. A noise musician and mighty mumbler when he broke through under the moniker of Smog in the early 1990s, Callahan now favors minimal indie-folk brushstrokes such as a guitar strum, a sighing pedal steel guitar, or simply barely audible room ambience. The 20 songs here insinuate themselves with bittersweet melodies and a conversational tone, and they’re a strong reminder of Callahan\'s dry sense of humor: “The panic room is now a nursery,” the recently married new father sings on “Son of the Sea.” But if he’s comparatively settled in life, Callahan still knows how to hit an unnerving note with a matter-of-fact ease.

The voice murmuring in our ear, with shaggy-dog and other kinds of stories, is an old friend we're so glad to hear again. Bill’s gentle, spacey take on folk and roots music is like no other; scraps of imagery, melody and instrumentation tumble suddenly together in moments of true human encounters.

It was on a mountainside in Cumbria that the first whispers of Cate Le Bon’s fifth studio album poked their buds above the earth. “There’s a strange romanticism to going a little bit crazy and playing the piano to yourself and singing into the night,” she says, recounting the year living solitarily in the Lake District which gave way to Reward. By day, ever the polymath, Le Bon painstakingly learnt to make solid wood tables, stools and chairs from scratch; by night she looked to a second-hand Meers — the first piano she had ever owned —for company, “windows closed to absolutely everyone”, and accidentally poured her heart out. The result is an album every bit as stylistically varied, surrealistically-inclined and tactile as those in the enduring outsider’s back catalogue, but one that is also intensely introspective and profound; her most personal to date. This sense of privacy maintained throughout is helped by the various landscapes within which Reward took shape: Stinson Beach, LA, and Brooklyn via Cardiff and The Lakes. Recording at Panoramic House [Stinson Beach, CA], a residential studio on a mountain overlooking the ocean, afforded Le Bon the ability to preserve the remoteness she had captured during the writing of Reward in Staveley, Lake District. Over this extended period a cast of trusted and loved musicians joined Le Bon, Khouja and fellow co-producer Josiah Steinbrick — Stella Mozgawa (of Warpaint) on drums and percussion; Stephen Black (aka Sweet Baboo) on bass and saxophone and longtime collaborators Huw Evans (aka H.Hawkline) and Josh Klinghoffer on guitars — and were added to the album, “one by one, one on one”. The fact that these collaborators have appeared variously on Le Bon’s previous outputs no doubt goes some way to aid the preservation of a signature sound despite a relatively drastic change in approach. Be it on her more minimalist, acoustic-leaning 2009 debut album Me Oh My or critically acclaimed, liquid-riffed 2013 LP Mug Museum as well as 2016s Crab Day, Cate Le Bon’s solo work — and indeed also her production work, such as that carried out on recent Deerhunter album Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? (4AD, January 2019) — has always resisted pigeonholing, walking the tightrope between krautrock aloofness and heartbreaking tenderness; deadpan served with a twinkle in the eye, a flick of the fringe and a lick of the Telecaster. The multifaceted nature of Le Bon’s art — its ability to take on multiple meanings and hold motivations which are not immediately obvious — is evident right down to the album’s very name. “People hear the word ‘reward’ and they think that it’s a positive word” says Le Bon, “and to me it’s quite a sinister word in that it depends on the relationship between the giver and the receiver. I feel like it’s really indicative of the times we’re living in where words are used as slogans, and everything is slowly losing its meaning.” The record, then, signals a scrambling to hold onto meaning; it is a warning against lazy comparisons and face values. It is a sentiment nicely summed up by the furniture-making musician as she advises: “Always keep your hand behind the chisel.”

Singer-songwriter Natalie Mering’s fourth album as Weyes Blood conjures the feeling of a beautiful object on a shelf just out of reach: You want to touch it, but you can’t, and so you do the next best thing—you dream about it, ache for it, and then you ache some more. Grand, melodramatic, but keenly self-aware, the music here pushes Mering’s \'70s-style chamber pop to its cinematic brink, suffusing stories of everything from fumbled romance (the McCartney-esque “Everyday”) to environmental apocalypse (“Wild Time”) with a dreamy, foggy almost-thereness both gorgeous and profoundly unsettling. A self-described “nostalgic futurist,” Mering doesn’t recreate the past so much as demonstrate how the past is more or less a fiction to begin with, a story we love hearing no matter how sad its unreachability makes us. Hence the album’s centerpiece, “Movies,” which wonders—gorgeously, almost religiously—why life feels so messy by comparison. As to the thematic undercurrent of apocalypse, well, if extinction is as close as science says it is, we might as well have something pretty to play us out.