XS Noize's 50 Best Albums of 2022

XS Noize: Albums of the year 2022 compiled by Iam Burn from lists by Mark Millar, Michael Barron, Ben P Scott, Marija Buljeta, Lee Campbell, Lori Gava,

Published: December 23, 2022 20:01

Source

If The Smile ever seemed like a surprisingly upbeat name for a band containing two members of Radiohead (Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood, joined by Sons of Kemet drummer Tom Skinner), the trio used their debut gig to offer some clarification. Performing as part of Glastonbury Festival’s Live at Worthy Farm livestream in May 2021, Yorke announced, “We are called The Smile: not The Smile as in ‘Aaah!’—more the smile of the guy who lies to you every day.” To grasp the mood of their debut album, it’s instructive to go even deeper into a name that borrows the title of a 1970 Ted Hughes poem. In Hughes’ impressionist verse, some elemental force—compassion, humanity, love maybe—rises up to resist the deception and chicanery behind such disarming grins. And as much as the 13 songs on *A Light for Attracting Attention* sense crisis and dystopia looming, they also crackle with hope and insurrection. The pulsing electronics of opener “The Same” suggest the racing hearts and throbbing temples of our age of acute anxiety, and Yorke’s words feel like a call for unity and mobilization: “We don’t need to fight/Look towards the light/Grab it in with both hands/What you know is right.” Perennially contemplating the dynamics of power and thought, he surveys a world where “devastation has come” (“Speech Bubbles”) under the rule of “elected billionaires” (“The Opposite”), but it’s one where protest, however extreme, can still birth change (“The Smoke”). Amid scathing guitars and outbursts of free jazz, his invective zooms in on abuses of power (“You Will Never Work in Television Again”) before shaming inertia and blame-shifters on the scurrying beats and descending melodies of “A Hairdryer.” These aren’t exactly new themes for Yorke and it’s not a record that sits at an extreme outpost of Radiohead’s extended universe. Emboldened by Skinner’s fluid, intrepid rhythms, *A Light for Attracting Attention* draws frequently on various periods of Yorke and Greenwood’s past work. The emotional eloquence of Greenwood’s soundtrack projects resurfaces on “Speech Bubbles” and “Pana-Vision,” while Yorke’s fascination with digital reveries continues to be explored on “Open the Floodgates” and “The Same.” Elegantly cloaked in strings, “Free in the Knowledge” is a beautiful acoustic-guitar ballad in the lineage of Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees” and the original live version of “True Love Waits.” Of course, lesser-trodden ground is visited, too: most intriguingly, math-rock (“Thin Thing”) and folk songs fit for a ’70s sci-fi drama (“Waving a White Flag”). The album closes with “Skrting on the Surface,” a song first aired at a 2009 show Yorke played with Atoms for Peace. With Greenwood’s guitar arpeggios and Yorke’s aching falsetto, it calls back even further to *The Bends*’ finale, “Street Spirit (Fade Out).” However, its message about the fragility of existence—“When we realize we have only to die, then we’re out of here/We’re just skirting on the surface”—remains sharply resonant.

The Smile will release their highly anticipated debut album A Light For Attracting Attention on 13 May, 2022 on XL Recordings. The 13- track album was produced and mixed by Nigel Godrich and mastered by Bob Ludwig. Tracks feature strings by the London Contemporary Orchestra and a full brass section of contempoarary UK jazz players including Byron Wallen, Theon and Nathaniel Cross, Chelsea Carmichael, Robert Stillman and Jason Yarde. The band, comprising Radiohead’s Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood and Sons of Kemet’s Tom Skinner, have previously released the singles You Will Never Work in Television Again, The Smoke, and Skrting On The Surface to critical acclaim.

Simple Minds return with eighteenth studio album Direction of the Heart, set for release on 21st October 2022 and including lead single ‘Vision Thing’. Direction of the Heart is Simple Minds’ first album of new material since 2018’s outstanding UK Top 5 album Walk Between Worlds. Throughout its nine tracks, Direction of the Heart finds the band at their most confident, anthemic best on an inspired celebration of life, and which manages to perfectly encapsulate the essence of past and present Simple Minds, a band whose reascent over the past 10 years has seen them, once again, capture the magic and critical praise of their early days.

A couple of years before she became known as one half of Wet Leg, Rhian Teasdale left her home on the Isle of Wight, where a long-term relationship had been faltering, to live with friends in London. Every Tuesday, their evening would be interrupted by the sound of people screaming in the property below. “We were so worried the first time we heard it,” Teasdale tells Apple Music. Eventually, their investigations revealed that scream therapy sessions were being held downstairs. “There’s this big scream in the song ‘Ur Mum,’” says Teasdale. “I thought it’d be funny to put this frustration and the failure of this relationship into my own personal scream therapy session.” That mix of humor and emotional candor is typical of *Wet Leg*. Crafting tightly sprung post-punk and melodic psych-pop and indie rock, Teasdale and bandmate Hester Chambers explore the existential anxieties thrown up by breakups, partying, dating apps, and doomscrolling—while also celebrating the fun to be had in supermarkets. “It’s my own experience as a twentysomething girl from the Isle of Wight moving to London,” says Teasdale. The strains of disenchantment and frustration are leavened by droll, acerbic wit (“You’re like a piece of shit, you either sink or float/So you take her for a ride on your daddy’s boat,” she chides an ex on “Piece of shit”), and humor has helped counter the dizzying speed of Wet Leg’s ascent. On the strength of debut single “Chaise Longue,” Teasdale and Chambers were instantly cast by many—including Elton John, Iggy Pop, and Florence Welch—as one of Britain’s most exciting new bands. But the pair have remained committed to why they formed Wet Leg in the first place. “It’s such a shame when you see bands but they’re habitually in their band—they’re not enjoying it,” says Teasdale. “I don’t want us to ever lose sight of having fun. Having silly songs obviously helps.” Here, she takes us through each of the songs—silly or otherwise—on *Wet Leg*. **“Being in Love”** “People always say, ‘Oh, romantic love is everything. It’s what every person should have in this life.’ But actually, it’s not really conducive to getting on with what you want to do in life. I read somewhere that the kind of chemical storm that is produced in your brain, if you look at a scan, it’s similar to someone with OCD. I just wanted to kind of make that comparison.” **“Chaise Longue”** “It came out of a silly impromptu late-night jam. I was staying over at Hester’s house when we wrote it, and when I stay over, she always makes up the chaise longue for me. It was a song that never really was supposed to see the light of day. So it’s really funny to me that so many people are into it and have connected with it. It’s cool. I was as an assistant stylist \[on Ed Sheeran’s ‘Bad Habits’ video\]. Online, a newspaper \[*The New York Times*\] was doing the top 10 videos out this week, and it was funny to see ‘Chaise Longue’ next to this video I’d been working on. Being on set, you have an idea of the budget that goes into getting all these people together to make this big pop-star video. And then you scroll down and it’s our little video that we spent about £50 on. Hester had a camera and she set up all the shots. Then I edited it using a free trial version of Final Cut.” **“Angelica”** “The song is set at a party that you no longer want to be at. Other people are feeling the same, but you are all just fervently, aggressively trying to force yourself to have a good time. And actually, it’s not always possible to have good times all the time. Angelica is the name of my oldest friend, so we’ve been to a lot of rubbish parties together. We’ve also been to a lot of good parties together, but I thought it would be fun to put her name in the song and have her running around as the main character.” **“I Don’t Wanna Go Out”** “It’s kind of similar to ‘Angelica’—it’s that disenchantment of getting fucked up at parties, and you’re gradually edging into your late twenties, early thirties, and you’re still working your shitty waitressing job. I was trying to convince myself that I was working these shitty jobs so that I could do music on the side. But actually, you’re kind of kidding yourself and you’re seeing all of your friends starting to get real jobs and they’re able to buy themselves nice shampoo. You’re trying to distract yourself from not achieving the things that you want to achieve in life by going to these parties. But you can’t keep kidding yourself, and I think it’s that realization that I’ve tried to inject into the lyrics of this song.” **“Wet Dream”** “The chorus is ‘Beam me up.’ There’s this Instagram account called beam\_me\_up\_softboi. It’s posts of screenshots of people’s texts and DMs and dating-app goings-on with this term ‘softboi,’ which to put it quite simply is someone in the dating scene who’s presenting themselves as super, super in touch with their feelings and really into art and culture. And they use that as currency to try and pick up girls. It’s not just men that are softbois; women can totally be softbois, too. The character in the song is that, basically. It’s got a little bit of my own personal breakup injected into it. This particular person would message me since we’d broken up being like, ‘Oh, I had a dream about you. I dreamt that we were married,’ even though it was definitely over. So I guess that’s why I decided to set it within a dream: It was kind of making fun of this particular message that would keep coming through to me.” **“Convincing”** “I was really pleased when we came to recording this one, because for the bulk of the album, it is mainly me taking lead vocals, which is fine, but Hester has just the most beautiful voice. I hope she won’t mind me saying, but she kind of struggles to see that herself. So it felt like a big win when she was like, ‘OK, I’m going to do it. I’m going to sing. I’m going to do this song.’ It’s such a cool song and she sounds so great on it.” **“Loving You”** “I met this guy when I was 20, so I was pretty young. We were together for six or seven years or something, and he was a bit older, and I just fell so hard. I fell so, so hard in love with him. And then it got pretty toxic towards the end, and I guess I was a bit angry at how things had gone. So it’s just a pretty angry song, without dobbing him in too much. I feel better now, though. Don’t worry. It’s all good.” **“Ur Mum”** “It’s about giving up on a relationship that isn’t serving you anymore, either of you, and being able to put that down and walk away from it. I was living with this guy on the Isle of Wight, living the small-town life. I was trying to move to London or Bristol or Brighton and then I’d move back to be with this person. Eventually, we managed to put the relationship down and I moved in with some friends in London. Every Tuesday, it’d get to 7 pm and you’d hear that massive group scream. We learned that downstairs was home to the Psychedelic Society and eventually realized that it was scream therapy. I thought it’d be funny to put this frustration and the failure of this relationship into my own personal scream therapy session.” **“Oh No”** “The amount of time and energy that I lose by doomscrolling is not OK. It’s not big and it’s not clever. This song is acknowledging that and also acknowledging this other world that you live in when you’re lost in your phone. When we first wrote this, it was just to fill enough time to play a festival that we’d been booked for when we didn’t have a full half-hour set. It used to be even more repetitive, and the lyrics used to be all the same the whole way through. When it came to recording it, we’re like, ‘We should probably write a few more lyrics,’ because when you’re playing stuff live, I think you can definitely get away with not having actual lyrics.” **“Piece of shit”** “When I’m writing the lyrics for all the songs with Wet Leg, I am quite careful to lean towards using quite straightforward, unfussy language and I avoid, at all costs, using similes. But this song is the one song on the album that uses simile—‘like a piece of shit.’ Pretty poetic. I think writing this song kind of helped me move on from that \[breakup\]. It sounds like I’m pretty wound up. But actually, it’s OK now, I feel a lot better.” **“Supermarket”** “It was written just as we were coming out of lockdown and there was that time where the highlight of your week would be going to the supermarket to do the weekly shop, because that was literally all you could do. I remember queuing for Aldi and feeling like I was queuing for a nightclub.” **“Too Late Now”** “It’s about arriving in adulthood and things maybe not being how you thought they would be. Getting to a certain age, when it’s time to get a real job, and you’re a bit lost, trying to navigate through this world of dating apps and social media. So much is out of our control in this life, and ‘Too late now, lost track somehow,’ it’s just being like, ‘Everything’s turned to shit right now, but that’s OK because it’s unavoidable.’ It sounds very depressing, but you know sometimes how you can just take comfort in the fact that no matter what you do, you’re going to die anyway, so don’t worry about it too much, because you can’t control everything? I guess there’s a little bit of that in ‘Too Late Now.’”

In sharply differing ways, thoughts of place and identity run through Fontaines D.C.’s music. Where 2019 debut *Dogrel* delivered a rich and raw portrait of the band’s home city, Dublin, 2020 follow-up *A Hero’s Death* was the sound of dislocation, a set of songs drawing on the introspection, exhaustion, and yearning of an anchorless life on the road. When the five-piece moved to London midway through the pandemic, the experiences of being outsiders in a new city, often facing xenophobia and prejudice, provided creative fuel for third album *Skinty Fia*. The music that emerged weaves folk, electronic, and melodic indie pop into their post-punk foundations, while contemplating Irishness and how it transforms in a different country. “That’s the lens through which all of the subjects that we explore are seen through anyway,” singer Grian Chatten tells Apple Music’s Matt Wilkinson. “There are definitely themes of jealousy, corruption, and stuff like that, but it’s all seen through the eyes of someone who’s at odds with their own identity, culturally speaking.” Recording the album after dark helped breed feelings of discomfort that Chatten says are “necessary to us,” and it continued a nocturnal schedule that had originally countered the claustrophobia of a locked-down city. “We wrote a lot of it at night as well,” says Chatten. “We went into the rehearsal space just as something different to do. When pubs and all that kind of thing were closed, it was a way of us feeling like the world was sort of open.” Here, Chatten and guitarist Carlos O’Connell talk us through a number of *Skinty Fia*’s key moments. **“In ár gCroíthe go deo”** Grian Chatten: “An Irish woman who lived in Coventry \[Margaret Keane\] passed away. Her family wanted the words ‘In ár gCroíthe go deo,’ which means ‘in our hearts forever,’ on her gravestone as a respectful and beautiful ode to her Irishness, but they weren’t allowed without an English translation. Essentially the Church of England decreed that it would be potentially seen as a political slogan. The Irish language is apparently, according to these people, an inflammatory thing in and of itself, which is a very base level of xenophobia. It’s a basic expression of a culture, is the language. If you’re considering that to be related to terrorism, which is what they’re implying, I think. That sounds like it’s something out of the ’70s, but this is two and a half years ago.” Carlos O’Connell: “About a year ago, it got turned around and \[the family\] won this case.” GC: “The family were made aware \[of the song\] and asked if they could listen to it. Apparently they really loved it, and they played it at the gravestone. So, that’s 100,000 Grammys worth of validation.” **“Big Shot”** CO: “When you’ve got used to living with what you have and then all these dreams happen to you, it’s always going to overshadow what you had before. The only impact that \[Fontaines’ success\] was having in my life was that it just made anything that I had before quite meaningless for a while, and I felt quite lost in that. That’s that lyric, ‘I traveled to space and found the moon too small’—it’s like, go up there and actually it’s smaller than the Earth.” GC: “We’ve all experienced it very differently and that’s made us grow in different ways. But that song just sounded like a very true expression of Carlos. Perhaps more honest than he always is with himself or other people. All the honesty was balled up into that tune.” **“Jackie Down the Line”** GC: “It’s an expression of misanthropy. And there’s toxicity there. There’s erosion of each other’s characters. It’s a very un-beneficial, unglamorous relationship that isn’t necessarily about two people. I like the idea of it being about Irishness, fighting to not be eroded as it exists in a different country. The name is Jackie because a Dubliner would be called, in a pejorative sense, a Jackeen by people from other parts of Ireland. That’s probably in reference to the Union Jack as well—it’s like the Pale \[an area of Ireland, including Dublin, that was under English governmental control during the late Middle Ages\]. So it’s this kind of mutation of Irishness or loss of Irishness as it exists, or fails to exist, in a different environment.” **“Roman Holiday”** GC: “The whole thing was colored by my experience in London. I moved to London to be with my fiancée, and as an Irish person living in London, as one of a gang of Irish people, there was that kind of searching energy, there was this excitement, there was a kind of adventure—but also this very, very tight-knit, rigorously upkept group energy. I think that’s what influenced the tune.” **“The Couple Across the Way”** GC: “I lived on Caledonian Road \[in North London\] and our gaff backed onto another house. There was a couple that lived there, they were probably mid-seventies, and they had really loud arguments. The kind of arguments where you’d see London on a map getting further, further away and hear the shout resounding. Something like *The Simpsons*. And the man would come out and take a big breath. He’d stand on his balcony and look left and right and exhale all the drama. And then he’d just turn around and go back in to his gaff to do the same thing the next day. The absurdity of that, of what we put ourselves through, to be in a relationship that causes you such daily pain, to just always turn around and go back in. I couldn’t really help but write about that physical mirror that was there. Am I seeing myself and my girlfriend in these two people, and vice versa? So I tried to tie it in to it being from both perspectives at some point.” **“Skinty Fia”** GC: “The line ‘There is a track beneath the wheel and it’s there ’til we die’ is about being your dad’s son. There are many ways in which we explore doom on this record. One of them is following in the footsteps of your ancestors, or your predecessors, no matter how immediate or far away they might have been. I’m interested in the inescapability of genetics, the idea that your fate is written. I do, on some level, believe in that. That is doom, even if your faith is leading you to a positive place. Freedom is probably the main pursuit of a lot of our music. I think that that is probably a link that ties all of the stuff that we’ve done together—autonomy.” **“I Love You”** GC: “It’s most ostensibly a love letter to Ireland, but has in it the corruption and the sadness and the grief with the ever-changing Dublin and Ireland. The reason that I wanted to call it ‘I Love You’ is because I found its cliché very attractive. It meant that there was a lot of work to be done in order to justify such a basic song and not have it be a clichéd tune. It’s a song with two heads, because you’ve got the slow, melodic verses that are a little bit more straightforward and then the lid is lifted off energetically. I think that the friction between those two things encapsulates the double-edged sword that is love.” **“Nabokov”** GC: “I think there’s a different arc to this album. The first two, I think, achieve a sense of happiness and hope halfway through, and end on a note of hope. I think this one does actually achieve hope halfway through—and then slides back into a hellish, doomy thing with the last track and stuff. I think that was probably one of the more conscious decisions that we made while making this album.”

"2020’s A Hero’s Death saw Fontaines D.C. land a #2 album in the UK, receive nominations at the GRAMMYs, BRITs and Ivor Novello Awards, and sell out London’s iconic Alexandra Palace. Now the band return with their third record in as many years: Skinty Fia. Used colloquially as an expletive, the title roughly translates from the Irish language into English as “the damnation of the deer”; the spelling crassly anglicized, and its meaning diluted through generations. Part bittersweet romance, part darkly political triumph - the songs ultimately form a long-distance love letter, one that laments an increasingly privatized culture in danger of going the way of the extinct Irish giant deer."

Yannis Philippakis doesn’t think that Foals will make another album like *Life Is Yours*. After the sprawling rock explorations of 2019’s two-part *Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost*, their seventh album is a product of the environment in which it was made: a series of grueling lockdowns, dreaming of lost nights and nocturnal roaming, yearning to be back out on the road. It was a period in which everyone was desperate to get out of the house, but only Foals could’ve turned it into the most buoyant and danceable record of their career. “I can’t see us making a record that’s as dancy and up and energized and simple as this again,” singer and guitarist Philippakis tells Apple Music. It’s not like the London-based trio ever seems inclined to repeat a trick anyway. “Everyone always says, ‘How come the sound changes so much from album to album?’” says guitarist and keyboardist Jimmy Smith. “Well, you go through three years, musically and emotionally, and you’re not the same person.” What marks Foals out as one of the most important guitar bands of their generation is how they always sound like themselves, wherever they take their sound: whether it’s the mix of melancholy and defiance in Philippakis’ voice; the wiry, sleek guitar lines; the swarming synths; or drummer Jack Bevan’s rhythmic propulsion. The anthemic grooves of *Life Is Yours* were made for dancing to, but delve deeper and you’ll find Philippakis in a contemplative mood. “It’s a positive and fun record made for communal moments, but the title is quite solemn advice,” he says. “It’s meant as an antidote to depression. On every record, there’s been a balancing act that goes on between the levels of melancholy.” Here, they get the blend just right. In many ways, *Life Is Yours* feels like a compilation of Foals’ best bits. Philippakis and Smith take us through it, track by track. **“Life Is Yours”** Yannis Philippakis: “Whatever is happening in the verse between the vocal and the keyboard part and the beat and the bassline felt like the DNA for the album, the blueprint. It was the bit I liked most. The song came right out of \[next track\] ‘Wake Me Up’—we were jamming it and then Jimmy went into that keyboard bit. The next day I said, ‘Let’s split it.’ Lyrically, the song is set along that coast between Seattle and Vancouver, where my partner is from, conversations that happen in private in car journeys along the Pacific Northwest.” **“Wake Me Up”** Jimmy Smith: “There’s always a bit of choice about which song to put out first, but this had the most immediate impact.” YP: “And it’s the most bombastic. We just felt that the message and the immediacy of the grooves and the boldness of the parts would be a wake-up call. It would demarcate the new era of the band and also be the kind of song that should come out after a pandemic. It felt like it was energizing and defiant, it wasn’t introspective. Normally we throw curveballs out first, we put something out that shocks people. I guess maybe it did in some way, but it also felt like it sets you up for what’s to come.” **“2am”** YP: “This started off more melancholic. I messed around with a keyboard during the depths of lockdown, late at night. I was missing the pub, missing the potential that a nightlife allows—the potential to make mistakes, the potential for wrong decisions, for wild decisions, for waking up in a very different place to the one you intended when you went out, the type of infinite choice that can occur if you do a night out well. It got moved into a bigger and poppier direction when we started recording with \[producer\] Dan Carey.” JS: “There was a smoky late-night version, which we were all down for. But as soon as we experienced the Dan Carey version, it made the smoky version seem unbelievably slow and dull.” **“2001”** YP: “This is one that really benefited from working on it with \[producer\] A. K. Paul. It’s almost a collaboration with A. K. Paul; he plays the bass on it and he wrote the chorus bass. It reminds me of The Rapture and ‘House of Jealous Lovers.’ Lyrically, I was thinking about the frustration that people were feeling in lockdown. It made me think about being a teenager and feeling frustrated when you are cooped up and you don’t have autonomy—and how the cure for that is to run away to the seaside and have a wild weekend. It’s partly looking back at when we moved to Brighton \[in 2001\], the excitement of leaving Oxford and us living in a house together for the first time. We moved there and it was a really exciting time for the band and an exciting time for the music scene.” **“(summer sky)”** YP: “This was essentially a jam with A. K. Paul. We’d wanted to work with him for a long time. We come from two different worlds, so it was a really fruitful collaboration.” JS: “Pretty much everything he did was amazing. He had to edit out a lot of his own stuff, but it was pretty special. We just sat on a sofa, watching it happen, watching this man use his amazing brain to make the song better.” **“Flutter”** YP: “I was looping something on the guitar and the vocal part came very quickly. We were playing it over and over, and Jack sat back on a beat, and the riff came out of that same jam. Everything was there in the first few hours, basically. We didn’t work on it more as we wanted it to be simple, like, ‘Let this be a slice of the moment.’” **“Looking High”** JS: “This is one of the ones that I started. It was an experiment of very, very simple guitar playing and pop structuring, that two-chord pattern back and forth, and I had a drum machine playing a Wu-Tang beat which I copied from ‘Protect Ya Neck.’ It all slotted in really quickly, and then Yannis added the other parts of the song, the more reflective, dancier bits in the drop-downs. When I listen, it feels like that moment at a show when you lose yourself a little bit and then it snaps back into the verse and it’s completely different. I really like the to-ing and fro-ing; there’s a cleanliness to it.” **“Under the Radar”** JS: “It came straight out of the practice room when we were writing. There’s a few on the record that were written on the spot, like nothing brought in from the past.” YP: “Probably 30 percent of our songs come from jams, but we always jam our ideas. No one ever comes in with a complete song, as in, ‘That’s it, learn the song.’ We tried to keep this really simple. It felt quite different for us. I think it feels New Wave-y, like something we haven’t written before.” **“Crest of the Wave”** YP: “This goes back to a recording session we did in about 2012, with Jono Ma from Jagwar Ma. It was this syrupy, sweaty jam known as ‘Isaac,’ and we parked it because I couldn’t find the vocals, but this time I did. Something happened between the bassline changing and the vocals, and we just cracked it. To me, it feels like a companion to \[2010 single\] ‘Miami’ because it’s set in Saint Lucia. It’s got longing and a bittersweet feeling of rejection in it; it’s somewhere idyllic, but you’re melancholic. There’s high humidity and there’s tears.” **“The Sound”** YP: “We don’t normally do that uplifting, classic penultimate track. This is us at our most electronic and clubby. It’s inspired by Caribou, that slightly dusty and dirty vibe; there’s crackle and a slight wildness to it. I like the fact that there’s a slightly West African-style guitar part that contrasts with the clubbiness of the synths. I had a lot of fun with the vocals on that. I wanted to layer up lots of shards of lyrics and approach it in a slightly Karl Hyde-ian way.” **“Wild Green”** JS: “The album finishes in such an organic way, it almost falls apart. I love how it just drops straight into the studio ambience. It seemed to happen quite naturally.” YP: “It’s about life cycles, the cycle of spring, expectation of spring and regeneration. In the first half of the song, there’s lyrics about wanting to fold oneself in the corner of the day and wait for the spring to reemerge. Then there’s a shift. Once you get to the second half of the song, spring is passed and now it’s actually the wind-down and it’s departure and it’s death. It’s not in a dark way, but it’s passing through states. It’s about the passing of time. That’s why it felt like a good album closer, because it’s basically saying, in a veiled way, farewell to the listener.”

A few months before releasing his third solo album, Liam Gallagher told Apple Music to expect a little of the unexpected. “Some of it’s odd,” he said. “I’d say 80 percent of the record is peculiar but still good, and 20 percent of it is classic. If you’re gonna do something a bit different, do it in these times, and if people don’t dig it, blame it on COVID.” On *C’MON YOU KNOW*, “odd” doesn’t quite mean a journey into the outer rims of acid trance or vaporwave, but, chiefly guided by trusted producer/songwriter Andrew Wyatt, Gallagher is noticeably freer of spirit. After two albums of bedding himself into a solo career with gently psychedelic rock that didn’t range too far from Oasis or Beady Eye, Liam is now deftly toggling between polemic punk and weightless dub on “I’m Free.” He told Apple Music that he’d bought a tepee to help cope with the claustrophobia of lockdown and, by building from a children’s choir to a grand, strobing finale, opener “More Power” suggests he spent those outdoor nights picking up signals from Spiritualized’s richly orchestrated cosmos. Other more intrepid moments include deeply psychedelic pop (“Better Days”), elegantly psychedelic soul (“The Joker”), and limber funk rock (“Diamond in the Dark”). While the music peers in new directions, the voice remains unmistakable—and in decent health. There’s a familiar snarl and swagger to “I’m Free” and the trippy, indie groove of “Don’t Go Halfway,” but Gallagher’s sometimes-overlooked warmth and reassurance are also regularly in play. He never likes slapping definitive meaning on the words he sings, preferring that listeners take what they want from the songs, and in a post-pandemic age there’s plenty to draw from the piano-driven heart-tugger “Too Good for Giving Up”: “Look how far you’ve come/Stronger than the damage done/Step out of the darkness unafraid.” During “Don’t Go Halfway,” he sings, “You were all thumbs/Through the dark days/When your time comes/Don’t go halfway.” On a record released a few months before his 50th birthday, Gallagher is heeding his own advice and emerging as a man whose horizons stretch further than ever.

The irony of Sophie Allison calling her second Soccer Mommy album *color theory* is that the title would be a better fit for her third, *Sometimes, Forever*. Not only is this record more stylistically varied on a track-to-track level—the flinty, classic indie rock of “Bones” and “Following Eyes,” the industrial tilt of “Darkness Forever,” the country vibe of “Feel It All the Time”—but it amplifies the internal mixings that make Allison’s songs vivid: beauty and dissonance (“Unholy Affliction”), romance and violence (“I cut a piece out of my thigh/And felt my heart go skydiving” on “Still”), bitter wisdom and wide-eyed innocence (“Feel It All the Time”). She’s a devoted student of the ’90s, to be sure—but one who’s rapidly outgrowing her influences, too.

Sometimes, Forever, the immersive and compulsively replayable new Soccer Mommy full-length, cements Sophie Allison’s status as one of the most gifted songwriters making rock music right now. The album finds Sophie broadening the borders of her aesthetic without abandoning the unsparing lyricism and addictive melodies that made earlier songs so easy to obsess over. To support her vision Sophie enlisted producer Daniel Lopatin, whose recent credits include the Uncut Gems movie score and The Weeknd’s Dawn FM.

This Machine Still Kills Fascists is the eleventh studio album and was released on September 30, 2022. It marks the band's first studio album since their 1998 debut album Do or Die to not feature vocalist Al Barr who was on hiatus from the band to take care of his ailing mother. It is the band's first acoustic album and is composed of unused lyrics and words by Woody Guthrie.

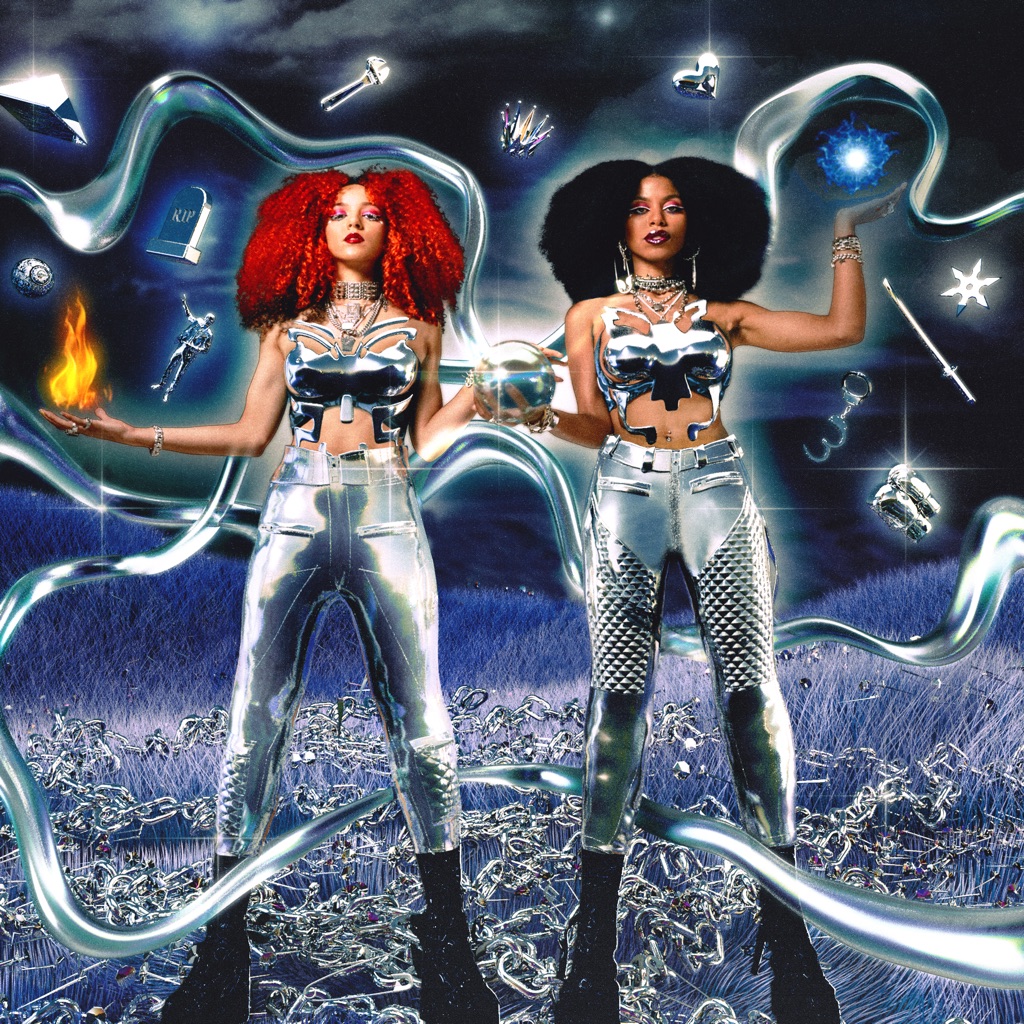

When a DIY ethos is baked into your core, your intuition is always likely to guide you right. Since forming in 2014, Nova Twins have established themselves as alt-rock explorers constantly crossing genre boundaries to absorb ideas and recast them in their own vision. The London-based duo of Amy Love and Georgia South approached their second album by dialing up both the brightness and heaviness of their debut, 2020’s *Who Are the Girls?*, operating on gut feel. “We have label support now, but it’s all still about us,” Love tells Apple Music. “It’s the shit we’ve always done, but they’ve helped us to facilitate the things we need to make the sound even bigger. There was no pressure, no schedule; we were just writing because we wanted to.” Written broadly during the pandemic and from within the Black Lives Matter movement, *Supernova* centers on the duo’s experiences of grief, heartbreak, erasure, and the empowerment of self-owned sexuality, as they battle their way through darkness to find light. The result is an album of intensity, energy, and enough fighting spirit to share around. “Life isn’t perfect, and we all have shit times,” says South. “But with *Supernova*, we want to give people that extra skip in their step, to feel like they can push through. Whatever you have going on, there is always a way to come out as a winner.” Let Nova Twins guide you through the album, track by track. **“Power (Intro)”** Georgia South: “We wanted a word that set the precedent for how we wanted the album to make people feel, and that word was ‘power.’” Amy Love: “It feels like a new beginning, a new era for the Nova Twins world. By putting this as the beginning and then ending on ‘Sleep Paralysis,’ it’s a wake-up call, like being born again.” GS: “It was just a nice little way to introduce the album and bookend the world that we created. If you were to be transported through a vortex, this is what it would sound like.” **“Antagonist”** AL: “This one came after the heavy lockdown. It felt so good to be able to finally meet up in person, and that energy and sense of connection is audible. It was just us together in a room, having fun.” GS: “We worked with Jim Abbiss again on production for the record, but in lockdown, we got really into Logic, the nitty-gritty of making beats and doing vocal production and sound effects ourselves. We learnt so much more about quality this time that a lot of the demos were good enough to go right on the album, and then, with Jim’s production style and live drums, we could focus on building up that really big sound.” **“Cleopatra”** AL: “The resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 was a traumatic time. It was so dark and depressing and terrifying, but when we all started unifying and marching, it felt like there was some sort of hope. It spurred us on to write something that would make people feel good, to feel powerful and proud of where they’re from. ‘Cleopatra’ was written in that moment of feeling truly part of something; we’re confident Black women, but it’s only when you start talking with others that you shine light on areas even you didn’t understand properly. We wanted to have a song that reflected the times, but also something which would give hope in the future.” **“K.M.B.”** GS: “With ‘K.M.B.’ \[Kill My Boyfriend\], we homed in on the sassy ’90s R&B that we both love. We love groups like Destiny’s Child, and we also love heavy music, so we thought that if we paired the two, we’d have the sassiest, most badass thing ever.” AL: “So many people can relate to the idea of getting revenge on a ex. When we read the lyrics back in isolation, we were like, ‘Is this a bit much?’ But then we were like, ‘Nah, it’s a joke. Right?!’” GS: “That’s why we made the music video so bright and colorful, to really get the joke across. The day of filming was so fun; the woman who owned the house came in and was like, ‘Can we rename the song “Kill My Husband?”’” AL: “He had cheated on her 47 times! She was like, ‘This video is the perfect send-off.’ She definitely saw the sense of humor in it.” **“Fire & Ice”** GS: “‘I tend to start with drums and then write riffs on top of the beat, building up in layers. We didn’t use any synths on the album, just bass, guitar, drums, and a bunch of pedals, which will make it a lot of fun to play live. I’m going to need a third leg!” AL: “Conceptually, it’s about all our moods as human beings. People assume that we’re scary or we’re this and that, but we’re all those things and the opposite. As women, we’re never just one thing; we can be moody, upset, loving, happy, vulnerable, sweet. It’s just about being a normal girl today—it’s not always pretty, but that duality is always going to be something you love about us.” **“Puzzles”** GS: “‘Puzzles’ puts us back in our ’90-2000s era. When you’re in a club, there’s those classic sexy tracks that you just want to dance to, like Khia’s ‘My Neck, My Back’ or ‘Pony’ by Ginuwine. We all want to feel sexy, to feel good about ourselves. We wanted it to be heavy—something you can mosh to but get down to at the same time.” AL: “It’s a fun song, but it’s also there to challenge people who are still living in the dark ages. There’s no line with Nova; we might like wearing baggy tracksuits, but at the same time, we also know how to let loose and have fun with our sexuality. If people are still uncomfortable about that, then a song like this is needed.” **“A Dark Place for Somewhere Beautiful”** AL: “We don’t always share our personal home truths in our music. Time is the biggest healer, and if something is still quite fresh, you can only talk about it so much. People can read between the lines and take what they want from it, but we all experience grief in our lives at some point, and this song is just describing what it feels like to go through that. A part of you disappears, but you also grow so much. Loss really does change you.” **“Toolbox”** GS: “It’s all about flipping the script on all the social pressures and beauty ideals that are usually aimed at women—changing up the roles so we’re singing it to a man. We’ve had to say, ‘Fuck you’ to so many men all the way along our career, and it’s built us into these strong women as a result. I’m grateful for it because it comes across in tunes like this.” **“Choose Your Fighter”** GS: “This was the last song we finished; we only had 24 hours to do it because of vinyl lead time. We were in the home studio writing, really tired. Whenever one of us was lagging, we’d have a tea break, put ‘Work Bitch’ by Britney Spears on, and then be like, ‘OK, we can do this.’ We truly have to thank Britney for this one—without her, we would have just slept.” AL: “In lockdown, we were sending songs back and forth, and then, suddenly, this was one where we were like, ‘I guess we’re writing an album.’ Lockdown was terrible, but it really helped us to find our way to this body of work, to say all the things that we wanted to say.” **“Enemy”** AL: “‘Enemy’ is about the time in our career where people weren’t quite getting it. We’ve seen other people be able to walk through so much easier because they fit the mold of what people perceive to be a riot grrrl. This was our kick back to the people who said that we look like we should only be doing hip-hop.” GS: “It’s pure rage, but we were also laughing so much while making it, putting people on our imaginary hit list. Obviously, we’re not trying to promote violence, but people can relate to that feeling in the moment. They can listen on their headphones going to work with their horrible boss, or at school if somebody’s picking on them. It’s a song about standing up for yourself.” **“Sleep Paralysis”** GS: “We were playing with different dynamics. It feels like you’re on a crazy loop because it joins back with the intro, and it’s a bit trippy and chaotic. It was definitely reflective of where we were at the time. We were locked down, BLM was going on, there was so much loss, and it was just like, ‘This is a full-on nightmare.’” AL: “We created this world where it almost felt like *Stranger Things*, The Upside Down. Everything seems really peaceful and calm and then, suddenly, the chorus hits. That gnarly hellscape feeling truly felt like what we were living through. It shows that we’re not afraid to not be super loud, that we don’t put boundaries on ourselves. Everything we’ve done with this band, we don’t plan; we just jump and see what happens. It’s always worked for us, so we’re going to keep jumping.”

As frontman James Smith and bassist Ryan Needham were holed up in Leeds, writing the songs that make up Yard Act’s debut album, the pair weren’t thinking about a record until they almost had one in front of them. Instead, they were caught up in the sort of heady, creative whirl you get from a new group flexing their songwriting chops. “We knew we were writing a lot, but there was no form or structure to it; it was just loads of ideas,” Smith tells Apple Music. “It was when we started to realize how much material we had that we said, ‘All right, now is probably the time to go in and have a go at the album.’” That spirit of artistic delirium runs right through *The Overload*, where wiry post-punk grooves and buoyant indie anthems-in-waiting frame Smith’s wry, cutting observations on life in modern Britain. “We realized there was a theme running through the songs,” recalls Smith, “an anti-capitalist slant to the whole thing. We came up with this idea of an arc about this person’s journey trying to become a success and how that pans out.” *The Overload* is a thrilling snapshot of pre- and post-pandemic life, less a black mirror to the early 2020s and more a vivid, full-color one. Here, Smith and Needham guide us through it, track by track. **“The Overload”** James Smith: “The song was originally a really pounding house track that Ryan had sent, but I heard the beat differently and put this sped-up drum-and-bass loop over the top of Ryan’s bassline. As soon as I put that on it, the energy made more sense. There’s a chopped sample break running underneath the whole thing that really completed it and gave it that manic feel.” **“Dead Horse”** JS: “I was always pretty keen on this being early on in the album. It feels like the culmination of all the early singles, finally figuring out how to write in our own style.” Ryan Needham: “I think, lyrically, James had a little bit of extreme anger around the time of the Dominic Cummings \[a former Chief Adviser to the Prime Minister caught breaking public health restrictions during the first UK lockdown\] stuff.” JS: “Yeah, it did come from that little month of anger. The bass was on groove; it was really good. And the lyrics played well—there were some good lines in there. It represented where we had got to up until that point.” **“Payday”** JS: “This was written to fit in on the album to coax the narrative along. Originally, it was a really lo-fi demo and then we lost it. When we redid it, we built in all these 909 electronic drums and then Sam \[Shjipstone\] put this really mad funk guitar on it that was exactly what it needed. It is just one of the more straight-up songs, a vehicle to get onto some of the more creative stuff. I tried to be more abstract with the lyrics—didn’t want to do the overly talky thing, so I left a lot more space in the verses so that chorus can come through a bit.” **“Rich”** JS: “It’s a really simple bassline that I was hypnotized by. It was written when Yard Act had just started doing OK. As some of these crazier offers were coming in, I could see it maybe reaching a level where we became part of the culture and made a living off it. I pondered on this idea that music is one of those things where, if it *goes*, you don’t really have control over how much money you suddenly earn out of nowhere. For so long, you are on the bottom rung and money is tight, and then, all of a sudden, the floodgates open and you can make loads of money really easy. That was it, but applied to the narrative of anyone that has an idea that becomes popular.” **“The Incident”** RN: “This was loads of fun. It’s a bit of an outlier on the record—it’s what sounds most like us live. I had been listening to loads of stuff like Omni and stuff like Elastica—this wave of what everyone was calling post-punk bands at the time. I wrote guitars for this one, everything, I got carried away.” JS: “I think you came up with some really interesting, busy basslines for this one.” **“Witness (Can I Get A?)”** JS: “This predates this lineup and lockdown in terms of the lyrics and the bassline. It was sounding quite generic, a post-punk sort of tune from the really early days where we had a couple of jams in late 2019.” RN: “Then, we tried it like the Beastie Boys.” JS: “We wanted to do a hardcore song, but that wasn’t really working either. Then, we did that sort of Suicide drum thing with it. As soon as it went like that, it always reminded me of the start of ‘Doorman’ by slowthai \[and Mura Masa\]. We just wanted a really fun song to close the first side. There’s something about one-minute songs—they are underrated.” **“Land of the Blind”** JS: “Ryan sent this drum-and-bass groove, and I was instantly really smitten with it, and I wrote the lyrics really fast. It’s one which has most of the demo vocals on it. We were in lockdown and Ryan got his girlfriend—who clearly can sing, but she doesn’t consider herself a singer and doesn’t perform or anything—to do all the backing vocals. They just come out so human. If a proper singer had done them, it wouldn’t have sounded right. It really shaped the song.” **“Quarantine the Sticks”** JS: “This was one of the last songs written for the record, another one that joins the narrative. The basslines are really good on this—they dance between different keys, which makes it really unnerving, and it’s got Billy Nomates \[post-punk singer-songwriter Tor Maries\] doing backing vocals on it as well. It’s quite melodic and quite a strange melody, and my voice wasn’t really holding it on \[its\] own. But there was a hint of something there, so we asked Tor to sing on it.” **“Tall Poppies”** RN: “It started with that simple bassline and then it just went on—I looped that bassline. I would send James a loop and then, about an hour later, I would get back something fucking epic, like ‘Tall Poppies.’ There was no craftsmanship on my part; it was basically like handing James a trowel and some bricks and he comes back with a finished wall.” JS: “There was something about the motor of the bassline. The first thing I got from it was that it felt quite reflective and suspensive. Off the back of that, I had that spark for telling the story of this person’s whole life, from cradle to grave.” **“Pour Another”** JS: “This was one of the harder ones. Ali \[Chant, producer\] didn’t really like this one. He kept pushing it away, but we were adamant it was good and there was something in it. ” RN: “I wanted to have a bit of a Happy Mondays sort of thing. The lyrics are funny, and the humor carried it in that way.” **“100% Endurance”** JS: “We thought the album was probably going to end on ‘Tall Poppies,’ and then, at the last-minute, Ryan sent this new demo over and it became ‘100% Endurance.’ I wrote all the lyrics to a WhatsApp video loop of it playing on Ryan’s speaker in the studio. That is the audio we used on the recording. The first take I recorded on my computer that I sent to Ryan. It felt like we had finally figured out the album, which was interesting because when we went in that first week, we thought we might come away with four or five tracks and then see where we were at later in the year. We didn’t expect to finish the album in a week.”

Behemoth leader Adam “Nergal” Darski borrowed a fitting term from Carl Jung for the title of his extreme-metal band’s 12th album. “Jung had his own agenda attached to it, but for me, it’s a work of art against the nature of things, the order of things,” the Polish guitarist and vocalist tells Apple Music. “It defines my approach to music.” As a vehemently anti-Christian artist who’s been repeatedly hauled into court on charges of blasphemy and “offending religious feelings” in his institutionally pious homeland, Nergal is especially attuned to censorship in all its forms. “There’s a set of standards that’s being imposed upon people, and especially artists, where you cannot talk freely,” he says. “To me, art has no limits. As we speak, I have three lawsuits happening simultaneously, for blasphemy and mocking this or that. There are people who watch my shows or read my lyrics and think, ‘This guy is a villain. We should put him behind bars.’ *Opvs Contra Natvram* is yet another middle finger I’m throwing against those cunts’ faces.” Below, he comments on each song. **“Post-God Nirvana”** “It’s an intro that’s also a song. There are just two proper verses, so it makes it a very weird, different song. Some of what I write is wishful thinking, like I’m projecting some kind of dystopian or post-apocalyptic or whatever future where things are going to be my way, or they’re not going to be my way. In this case, I imagine a world, let’s say 50 years down the road, where the world is free of God, free of religion. There’s no abortion laws. There are no chains anymore. People are basically free.” **“Malaria Vvlgata”** “After ‘Post-God Nirvana,’ I wanted to come out with something absolutely blistering, something polarizing. ‘Malaria Vvlgata’ was deliberately done as a hit between the eyes with an iron first. It’s almost punky—a burst of anti-Christian, anti-religious feeling. There’s no nuances. It’s a hate anthem, just completely uncompromising. It’s one of the most brutal songs I’ve ever written and definitely the shortest one I’ve ever written.” **“The Deathless Sun”** “This song reminds me of how I felt about ‘Ora Pro Nobis Lucifer’ when we did *The Satanist*. When we wrote that song, I thought, ‘OK, it’s strong, it’s a banger, but it’s probably not the strongest song on the record.’ But then, holy shit—it really took crowds by storm. People went totally nuts when we played it live. When we started playing this album for people, a lot of them were saying ‘The Deathless Sun’ is the strongest on the record. It took me a while to realize that, but now I’m thinking it’s one of my absolute favorites.” **“Ov My Herculean Exile”** “It’s probably the most mellow track on the record, and it was also the first one we made a video for. Every other band, when they release their first single, it’s always a banger. They’re just fucking flexing the muscles, like, ‘We are the heaviest, we are the fastest.’ But I wanted to do it the other way around. I wanted to serve an aperitif first, rather than the main course. I’d say this is our storytelling song. It’s rather epic and midtempo. A lot of people were complaining, ‘Where’s the speed?’ But I’m dying to read the comments when they hear how fucking intense the full record is.” **“Neo-Spartacvs”** “I love this one. It’s very catchy and brutal. The message behind the song is quite crucial because everyone knows who Spartacus is; he’s probably the most-known rebel in history. I’m telling people there are many things that you can rebel against that are objectively wrong. I think the invasion of Ukraine by Russia is wrong, and I don’t give a fuck if you agree with me or not. I think the righteous thing is to be a Spartacus about that. Please support Ukraine. Make people aware of what is happening. There is an obvious invader and an obvious victim. There is no gray spot.” **“Disinheritance”** “Again, this is one of the most brutal songs I’ve ever written. I really hope that people will find it as the hidden treasure of the record. It’s a really strong, powerful song that this record needed. I’m particularly proud of the midsection—it’s one of the craziest parts I’ve ever come up with. It’s like a complete fucking tornado, almost going out of tune. It gets to the point where it sounds cacophonic. It’s the sickest, most bizarre part I’ve ever written for this band.” **“Off To War!”** “It\'s a banger of a song with punky vibes. I started exploring those vibes on the previous record, and I think I kind of perfected it on this album. When Ihsahn from Emperor heard this, he said it has that ’90s black-metal feel to it. Maybe it does—I don’t know, but I really like the song. It’s super powerful to play live. The lyrics are very existential. There’s a lot of questions I’m throwing into the ether, but I’m not answering them. There’s no fun in giving answers. I’m not clever enough to answer those questions.” **“Once Upon A Pale Horse”** “I’ve never done anything similar to this before. It has a groove that I believe can really do a lot of damage live. It sounds almost rock-ish, but we turn it into our black metal, and it’s fucking sharp and dangerous. There’s a conquering riff with almost a power-metal vibe. I’m not afraid to say that I was a big fan of Manowar, and if there is a power-metal moment on this record, it’s in the chorus of this song, which is some of my words mixed with Aleister Crowley’s most famous quote ‘do what thou wilt,’ which I’ve had tattooed on me for 20 years.” **“Thy Becoming Eternal”** “When it comes to fast songs, this is my favorite. The first section is fucking relentless. It never stops. I did the choirs, and my friend Zofia from the Polish band Obscure Sphinx added those really weird-sounding female vocals on top of it. \[Bassist\] Orion also backed me up with the vocals. It doesn’t leave any room for breath, and then it just opens up. When you watch the video that accompanies the song, it’s the moment where the world opens up and they’re ready to receive the knowledge from the fire seeker. He’s carrying the Torch of Heraclitus, and he’s just giving it to the world.” **“Versvs Christvs”** “I wanted this to be a stand-alone monument, something that does everything—like ‘Stairway to Heaven’ is everything. Of course, I’m not competing with fucking timeless Led Zeppelin classics, but some bands release songs that are just fucking bigger than everything, you know? Like \[Iron Maiden’s\] ‘Powerslave’ or \[Slayer’s\] ‘Seasons in the Abyss’ or \[Metallica’s\] ‘Master of Puppets.’ I wanted to make something so bombastic, you couldn’t label it. It’s a song that takes different curves. It’s anthemic. It has choirs. It’s goth. I’m singing over a piano, and then it speeds up with a punky vibe, and then it goes into a blasting riff. It’s very adventurous and all over the place. Again, I’m not comparing this to classics. What I’m saying is that I’m aspiring.”

“I want to love unconditionally now.” Read on as Steve Lacy opens up about how he made his sophomore album in this exclusive artist statement. “Someone asked me if I felt pressure to make something that people might like. I felt a disconnect, my eyes squinted as I looked up. As I thought about the question, I realized that we always force a separation between the artist (me) and audience (people). But I am not separate. I am people, I just happen to be an artist. Once I understood this, the album felt very easy and fun to make. *Gemini Rights* is me getting closer to what makes me a part of all things, and that is: feelings. Feelings seem like the only real things sometimes. “I write about my anger, sadness, longing, confusion, happiness, horniness, anger, happiness, confusion, fear, etc., all out of love and all laughable, too. The biggest lesson I learned at the end of this album process was how small we make love. I want to love unconditionally now. I will make love bigger, not smaller. To me, *Gemini Rights* is a step in the right direction. I’m excited for you to have this album as your own as it is no longer mine. Peace.” —Steve Lacy

It has nearly become a cliché unto itself for so many albums released in 2021 and 2022: an accomplished work of art that perfectly articulates themes of isolation and desperation and fatalism, only for the artists to reveal that the songs that express these ideas most acutely were written *before* the pandemic. “It was already sort of all in the world,” Arcade Fire’s Win Butler tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “In order to write music, you have to have this antenna up that kind of picks up little signals from the future and signals from the past. And so I think a lot of times we\'re just getting these like aftershocks of things that are about to happen.” *WE* is 10 tracks, but really more like five songs, taking into account various parts and chapters that give the album its epic scope, capturing the joy-in-the-face-of-peril spirit of their beloved 2004 debut *Funeral*, only with the peril a bit heightened. The songs that Butler and his wife Régine Chassagne started in their backyard New Orleans studio prior to March 2020 form a narrative that opens in a state of despair and winds up in an unlikely place of hope and optimism, with all the exuberance that marks the band’s most memorable songs. Like all Arcade Fire albums, *WE* is a family affair, featuring not just Butler, Chassagne, and Butler’s younger brother Will—who has since left the group, amicably—but Butler’s mom, a harpist, as well as guest vocals from Peter Gabriel. Read on as Butler expounds on a few key moments from *WE*. **“End of the Empire I-III”** “It\'s easy to interpret everything as being about the present, and I think there\'s an element of that, but I think you\'re trying to pick up on smoke signals. To me, the end of the empire isn\'t about now, it\'s about the future. It\'s about what\'s coming. I\'m still waiting to wake up and check my phone and see the stock market has finally crashed. I mean, it\'s just an inevitability. This stuff is so cyclical, and it\'s like we\'re just printing money and pretending everything\'s okay. My grandfather lived through the Depression and was a musician in World War II and lived through some pretty intense stuff, and so I think this generation is up to the task as well. We have an eight-year-old, and the tools that he has compared to the tools that I had at that age are incredible.” **“End of the Empire IV (Sagittarius A)”** “‘End of the Empire’ is four parts; we had the first three parts and it was already six and a half minutes. For some reason I just knew that there was a fourth part to it, and I had this index card that said, ‘Sagittarius A,’ which is a black hole in the middle of our solar system. I just had the card on my wall and I would just walk by it. As soon as I was vaccinated and was able to travel, I went with my son to go visit my parents because I hadn\'t seen them in a long time. I went back to their house in Maine and I brought my 4-track and I put it in the basement of their house and ran a bunch of cables up to the top floor. I felt like I was 15. It was exactly like the shit I was doing when I was 15. I was like, \'Mom, I\'m working on this song.\' We would play \'Sagittarius A\' together. There were a couple other songs that I did these 4-track recordings of playing it with her, and it sort of helped me to work through it and to just figure out what it is.” **“The Lightning II”** “What was in my head when I was singing that song was all the Haitians at the border trying to get into the US who had taken a boat from Haiti to Brazil and then walked or taken a train all the way to the Mexican border. Just to find a better life for your family—imagine what it would take, the bravery. The governor of Texas can honestly...I don\'t hate a lot of people, but I hate that motherfucker. I don\'t even believe in hell, but if there\'s a hell, that motherfucker\'s going there. Just to meet people with the absolute absence of compassion, these fake fucking Christians. That\'s not necessarily what the song\'s about, but that was what was in my head: What does it mean to not quit and to reach the end and then to be turned back, and you still can\'t quit because you still have your family, so then you get sent back to where you started and you still can\'t give up because it\'s still your life and it\'s still your family and you\'re still fighting for survival.” **“Unconditional I (Lookout Kid)”** “I was really just thinking about my son and the world that he\'s facing and how I was a very depressed kid, particularly in high school. I was trying to imagine the way that I\'m wired, just chemically, having to deal with that now, not to mention 10 years from now, whenever the fuck he\'s going to be dealing with it. He\'s going to need to have a thick skin and to just really be able to take a hit and have some fortitude. And basically just the idea of unconditional love, which is this impossible thing to achieve. But we do it naturally, somehow. And it\'s something that I think we naturally have with our kids, but I think it\'s something that we\'re supposed to have for people that we\'re not related to as well.” **“WE”** “I think the journey of the record, the first half is: Imagine this character\'s like, \'Get me the F out of here, get me off this planet, get me out of my own skin, get me away from myself. I don\'t want to be here.\' It\'s anxiety and it\'s depression and it\'s heaviness, it\'s the weight of the world. And he looks at this black hole like, \'Well, maybe if I could get through that black hole, that would be far enough away.\' And when he gets there, he finds that it\'s himself and it\'s everyone he ever loved and the lives of his ancestors. There\'s nothing to escape, because it\'s all the same thing anyway. Stories and films are always building towards this big conclusion and then the credits roll. And to me, the sentiment is, \'Let\'s just fucking do it again, with all of it—all the pain, all the loneliness, all the sadness, all the heartbreak. I just want to do it over and over again. Just run it back.”

Anyone encountering the gorgeous, ’70s-style orchestral pop of *And in the Darkness, Hearts Aglow* might be surprised to learn that Natalie Mering started her journey as an experimental-noise musician. Listen closer, though, and you’ll hear an album whose beauty isn’t just tempered by visions of almost apocalyptic despair, but one that also turns beauty itself into a kind of weapon against the deadness and cynicism of modern life. After all, what could be more rebellious in 2022 than being as relentlessly and unapologetically beautiful as possible? Stylistically, the album draws influence from the gold-toned sounds of California artists like Harry Nilsson, Judee Sill, and even the Carpenters. Its mood evokes the strange mix of cheerfulness and violent intimations that makes late-’60s Los Angeles so captivating to the cultural imagination. And like, say, The Beach Boys circa *Pet Sounds* or *Smiley Smile*, the sophistication of Mering’s arrangements—the mix of strings, synthesizer touches, soft-focus ambience, and bone-dry intimacy—is more evocative of childhood innocence than adult mastery. Where her 2019 breakthrough, *Titanic Rising*, emphasized doom, *Hearts Aglow*—the second installment of a stated trilogy—emphasizes hope. She writes about alienation in a way that feels both compassionate and angst-free (“It’s Not Just Me, It’s Everybody”), and of romance so total, it could make you as sick as a faceful of roses (“Hearts Aglow,” “Grapevine”). And when the hard times come, she prays not for thicker armor, but to be made so soft that the next touch might crush her completely (“God Turn Me Into a Flower”). All told, *And in the Darkness, Hearts Aglow* is the feather that knocks you over.

August 25th, 2022 Los Angeles, CA Hello Listener, Well, here we are! Still making it all happen in our very own, fully functional shit show. My heart, like a glow stick that’s been cracked, lights up my chest in a little explosion of earnestness. And when your heart's on fire, smoke gets in your eyes. Titanic Rising was the first album of three in a special trilogy. It was an observation of things to come, the feelings of impending doom. And in the Darkness, Hearts Aglow is about entering the next phase, the one in which we all find ourselves today — we are literally in the thick of it. Feeling around in the dark for meaning in a time of instability and irrevocable change. Looking for embers where fire used to be. Seeking freedom from algorithms and a destiny of repetitive loops. Information is abundant, and yet so abstract in its use and ability to provoke tangible actions. Our mediums of communication are fraught with caveats. Our pain, an ironic joke born from a gridlocked panopticon of our own making, swirling on into infinity. I was asking a lot of questions while writing these songs, and hyper isolation kept coming up for me. “It’s Not Just Me, It’s Everybody” is a Buddhist anthem, ensconced in the interconnectivity of all beings, and the fraying of our social fabric. Our culture relies less and less on people. This breeds a new, unprecedented level of isolation. The promise we can buy our way out of that emptiness offers little comfort in the face of fear we all now live with – the fear of becoming obsolete. Something is off, and even though the feeling appears differently for each individual, it is universal. Technology is harvesting our attention away from each other. We all have a “Grapevine” entwined around our past with unresolved wounds and pain. Being in love doesn’t necessarily mean being together. Why else do so many love songs yearn for a connection? Could it be narcissism? We encourage each other to aspire – to reach for the external to quell our desires, thinking goals of wellness and bliss will alleviate the baseline anxiety of living in a time like ours. We think the answer is outside ourselves, through technology, imaginary frontiers that will magically absolve us of all our problems. We look everywhere but in ourselves for a salve. In “God Turn Me into a Flower,” I relay the myth of Narcissus, whose obsession with a reflection in a pool leads him to starve and lose all perception outside his infatuation. In a state of great hubris, he doesn’t recognize that the thing he so passionately desired was ultimately just himself. God turns him into a pliable flower who sways with the universe. The pliable softness of a flower has become my mantra as we barrel on towards an uncertain fate. I see the heart as a guide, with an emanation of hope, shining through in this dark age. Somewhere along the line, we lost the plot on who we are. Chaos is natural. But so is negentropy, or the tendency for things to fall into order. These songs may not be manifestos or solutions, but I know they shed light on the meaning of our contemporary disillusionment. And maybe that’s the beginning of the nuanced journey towards understanding the natural cycles of life and death, all over again. Thoughts and Prayers, Natalie Mering (aka Weyes Blood)

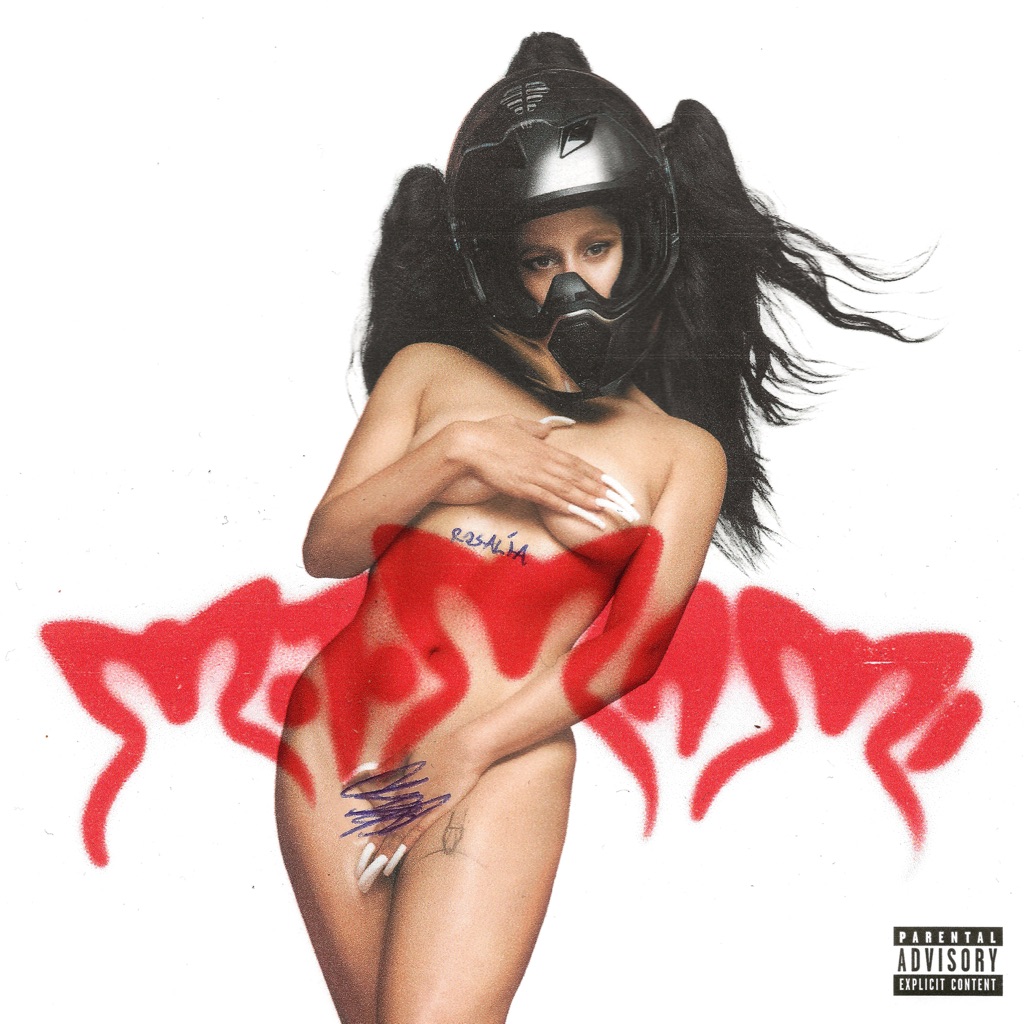

“I literally don’t take breaks,” ROSALÍA tells Apple Music. “I feel like, to work at a certain level, to get a certain result, you really need to sacrifice.” Judging by *MOTOMAMI*, her long-anticipated follow-up to 2018’s award-winning and critically acclaimed *EL MAL QUERER*, the mononymous Spanish singer clearly put in the work. “I almost feel like I disappear because I needed to,” she says of maintaining her process in the face of increased popularity and attention. “I needed to focus and put all my energy and get to the center to create.” At the same time, she found herself drawing energy from bustling locales like Los Angeles, Miami, and New York, all of which she credits with influencing the new album. Beyond any particular source of inspiration that may have driven the creation of *MOTOMAMI*, ROSALÍA’s come-up has been nothing short of inspiring. Her transition from critically acclaimed flamenco upstart to internationally renowned star—marked by creative collaborations with global tastemakers like Bad Bunny, Billie Eilish, and Oneohtrix Point Never, to name a few—has prompted an artistic metamorphosis. Her ability to navigate and dominate such a wide array of musical styles only raised expectations for her third full-length, but she resisted the idea of rushing things. “I didn’t want to make an album just because now it’s time to make an album,” she says, citing that several months were spent on mixing and visuals alone. “I don’t work like that.” Some three years after *EL MAL QUERER*, ROSALÍA’s return feels even more revolutionary than that radical breakout release. From the noisy-yet-referential leftfield reggaetón of “SAOKO” to the austere and *Yeezus*-reminiscent thump of “CHICKEN TERIYAKI,” *MOTOMAMI* makes the artist’s femme-forward modus operandi all the more clear. The point of view presented is sharp and political, but also permissive of playfulness and wit, a humanizing mix that makes the album her most personal yet. “I was like, I really want to find a way to allow my sense of humor to be present,” she says. “It’s almost like you try to do, like, a self-portrait of a moment of who you are, how you feel, the way you think.\" Things get deeper and more unexpected with the devilish-yet-austere electronic punk funk of the title track and the feverish “BIZCOCHITO.” But there are even more twists and turns within, like “HENTAI,” a bilingual torch song that charms and enraptures before giving way to machine-gun percussion. Add to that “LA FAMA,” her mystifying team-up with The Weeknd that fuses tropical Latin rhythms with avant-garde minimalism, and you end up with one of the most unique artistic statements of the decade so far.