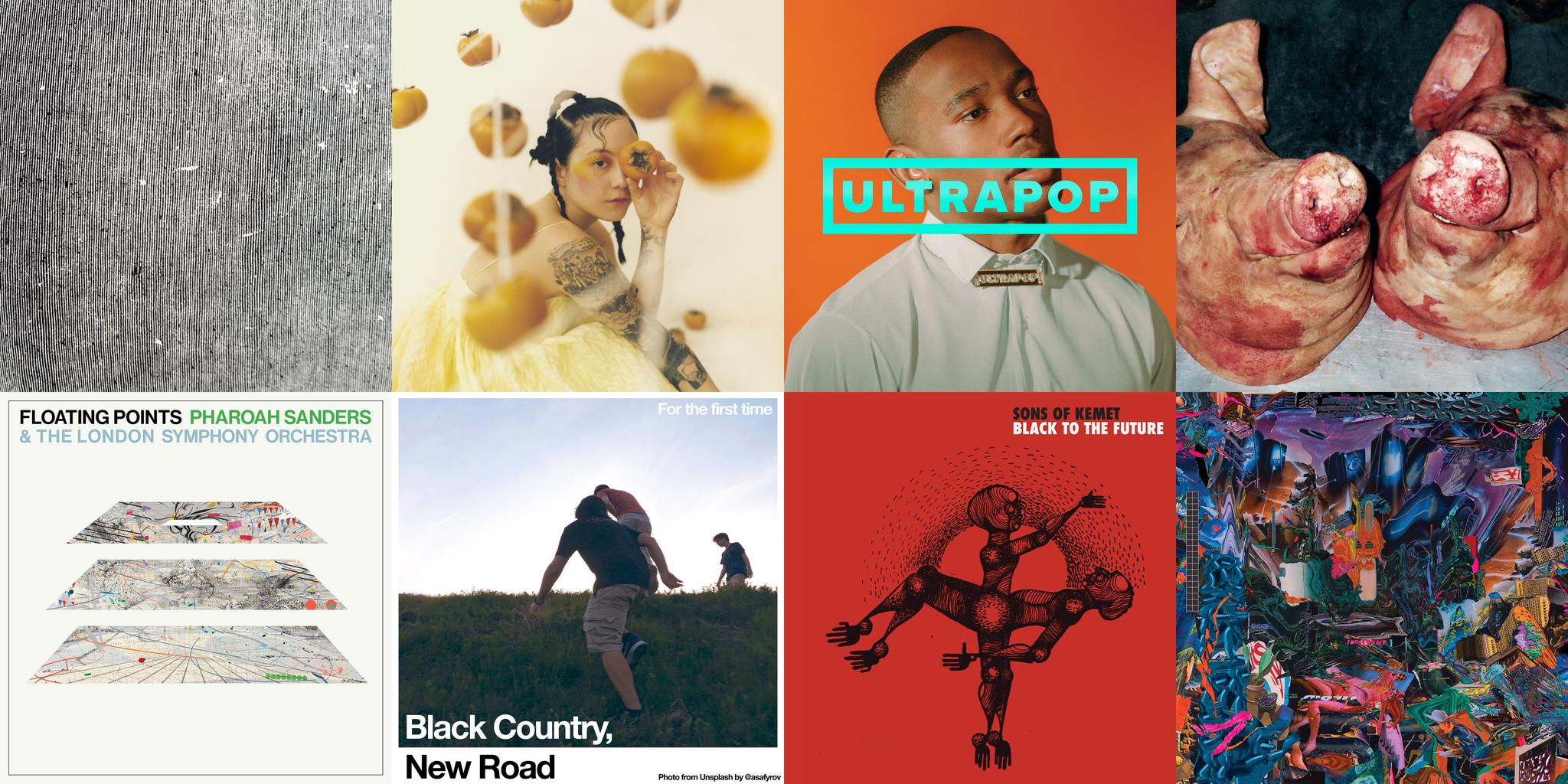

Treble's 50 Best Albums of 2021

Our list of the 50 best albums of 2021 is a cross section of gems from a strange year, from haunted gospel to orchestral rap maximalism.

Published: December 07, 2021 04:01

Source

When Low started out in the early ’90s, you could’ve mistaken their slowness for lethargy, when in reality it was a mark of almost supernatural intensity. Like 2018’s *Double Negative*, *Hey What* explores new extremes in their sound, mixing Alan Sparhawk and Mimi Parker\'s naked harmonies with blocks of noise and distortion that hover in drumless space—tracks such as “Days Like These” and “More” sound more like 18th-century choral music than 21st-century indie rock. Their faith—they’ve been practicing Mormons most of their lives—has never been so evident, not in content so much as purity of conviction: Nearly 30 years after forming, they continue to chase the horizon with a fearlessness that could make anyone a believer.

After two critically acclaimed albums about loss and mourning and a *New York Times* best-selling memoir, Michelle Zauner—the Brooklyn-based singer-songwriter known as Japanese Breakfast—wanted release. “I felt like I’d done the grief work for years and was ready for something new,” she tells Apple Music. “I was ready to celebrate *feeling*.” Her third album *Jubilee* is unguardedly joyful—neon synths, bubblegum-pop melodies, gusts of horns and strings—and delights in largesse; her arrangements are sweeping and intricate, her subjects complex. Occasionally, as on “Savage Good Boy” and “Kokomo, IN,” she uses fictional characters to illustrate meta-narratives around wealth, corruption, independence, and selfhood. “Album three is your chance to think big,” she says, pointing to Kate Bush and Björk, who released what she considers quintessential third albums: “Theatrical, ambitious, musical, surreal.” Below, Zauner explains how she reconciled her inner pop star with her desire to stay “extremely weird” and walks us through her new album track by track. **“Paprika”** “This song is the perfect thesis statement for the record because it’s a huge, ambitious monster of a song. We actually maxed out the number of tracks on the Pro Tools session because we used everything that could possibly be used on it. It\'s about reveling in the beauty of music.” **“Be Sweet”** “Back in 2018, I decided to try out writing sessions for the first time, and I was having a tough go of it. My publisher had set me up with Jack Tatum of Wild Nothing. What happens is they lie to you and say, ‘Jack loves your music and wants you to help him write his new record!’ And to him they’d say, ‘Michelle *loves* Wild Nothing, she wants to write together!’ Once we got together we were like, ‘I don\'t need help. I\'m not writing a record.’ So we decided we’d just write a pop song to sell and make some money. We didn’t have anyone specific in mind, we just knew it wasn’t going to be for either of us. Of course, once we started putting it together, I realized I really loved it. I think the distance of writing it for ‘someone else’ allowed me to take on this sassy \'80s women-of-the-night persona. To me, it almost feels like a Madonna, Whitney Houston, or Janet Jackson song.” **“Kokomo, IN”** “This is my favorite song off of the album. It’s sung from the perspective of a character I made up who’s this teenage boy in Kokomo, Indiana, and he’s saying goodbye to his high school sweetheart who is leaving. It\'s sort of got this ‘Wouldn\'t It Be Nice’ vibe, which I like, because Kokomo feels like a Beach Boys reference. Even though the song is rooted in classic teenage feelings, it\'s also very mature; he\'s like, ‘You have to go show the world all the parts of you that I fell so hard for.’ It’s about knowing that you\'re too young for this to be *it*, and that people aren’t meant to be kept by you. I was thinking back to how I felt when I was 18, when things were just so all-important. I personally was *not* that wise; I would’ve told someone to stay behind. So I guess this song is what I wish I would’ve said.” **“Slide Tackle”** “‘Slide Tackle’ was such a fussy bitch. I had a really hard time figuring out how to make it work. Eventually it devolved into, of all things, a series of solos, but I really love it. It started with a drumbeat that I\'d made in Ableton and a bassline I was trying to turn into a Future Islands-esque dance song. That sounded too simple, so I sent it to Ryan \[Galloway\] from Crying, who wrote all these crazy, math-y guitar parts. Then I got Adam Schatz, who plays in the band Landlady, to provide an amazing saxophone solo. After that, I stepped away from the song for like a year. When I finally relistened to it, it felt right. It’s about the way those of us who are predisposed to darker thoughts have to sometimes physically wrestle with our minds to feel joy.” **“Posing in Bondage”** “Jack Tatum helped me turn this song into this fraught, delicate ballad. The end of it reminds me of Drake\'s ‘Hold On, We\'re Going Home’; it has this drive-y, chill feeling. This song is about the bondage of controlled desire, and the bondage of monogamy—but in a good way.” **“Sit”** “This song is also about controlled desire, or our ability to lust for people and not act on it. Navigating monogamy and desire is difficult, but it’s also a normal human condition. Those feelings don’t contradict loyalty, you know? The song is shaped around this excellent keyboard line that \[bandmate\] Craig \[Hendrix\] came up with after listening to Tears for Fears. The chorus reminds me of heaven and the verses remind me of hell. After these dark and almost industrial bars, there\'s this angelic light that breaks through.” **“Savage Good Boy”** “This one was co-produced by Alex G, who is one of my favorite musicians of all time, and was inspired by a headline I’d read about billionaires buying bunkers. I wanted to write it from the perspective of a billionaire who’d bought one, and who was coaxing a woman to come live with him as the world burned around them. I wanted to capture what that level of self-validation looks like—that rationalization of hoarding wealth.” **“In Hell”** “This might be the saddest song I\'ve ever written. It\'s a companion song to ‘In Heaven’ off of *Psychopomp*, because it\'s about the same dog. But here, I\'m putting that dog down. It was actually written in the *Soft Sounds* era as a bonus track for the Japanese release, but I never felt like it got its due.” **“Tactics”** “I knew I wanted to make a beautiful, sweet, big ballad, full of strings and groovy percussion, and Craig, who co-produced it, added this feel-good Bill Withers, Randy Newman vibe. I think the combination is really fabulous.” **“Posing for Cars”** “I love a long, six-minute song to show off a little bit. It starts off as an understated acoustic guitar ballad that reminded me of Wilco’s ‘At Least That\'s What You Said,’ which also morphs from this intimate acoustic scene before exploding into a long guitar solo. To me, it always has felt like Jeff Tweedy is saying everything that can\'t be said in that moment through his instrument, and I loved that idea. I wanted to challenge myself to do the same—to write a long, sprawling, emotional solo where I expressed everything that couldn\'t be said with words.”

The jazz great Pharoah Sanders was sitting in a car in 2015 when by chance he heard Floating Points’ *Elaenia*, a bewitching set of flickering synthesizer etudes. Sanders, born in 1940, declared that he would like to meet the album’s creator, aka the British electronic musician Sam Shepherd, 46 years his junior. *Promises*, the fruit of their eventual collaboration, represents a quietly gripping meeting of the two minds. Composed by Shepherd and performed upon a dozen keyboard instruments, plus the strings of the London Symphony Orchestra, *Promises* is nevertheless primarily a showcase for Sanders’ horn. In the ’60s, Sanders could blow as fiercely as any of his avant-garde brethren, but *Promises* catches him in a tender, lyrical mode. The mood is wistful and elegiac; early on, there’s a fleeting nod to “People Make the World Go Round,” a doleful 1971 song by The Stylistics, and throughout, Sanders’ playing has more in keeping with the expressiveness of R&B than the mountain-scaling acrobatics of free jazz. His tone is transcendent; his quietest moments have a gently raspy quality that bristles with harmonics. Billed as “a continuous piece of music in nine movements,” *Promises* takes the form of one long extended fantasia. Toward the middle, it swells to an ecstatic climax that’s reminiscent of Alice Coltrane’s spiritual-jazz epics, but for the most part, it is minimalist in form and measured in tone; Shepherd restrains himself to a searching seven-note phrase that repeats as naturally as deep breathing for almost the full 46-minute expanse of the piece. For long stretches you could be forgiven for forgetting that this is a Floating Points project at all; there’s very little that’s overtly electronic about it, save for the occasional curlicue of analog synth. Ultimately, the music’s abiding stillness leads to a profound atmosphere of spiritual questing—one that makes the final coda, following more than a minute of silence at the end, feel all the more rewarding.

“I don\'t think it\'s an incredible, incredible album, but I do think it\'s an honest portrayal of what we were like and what we sounded like when those songs were written,” Black Country, New Road frontman Isaac Wood tells Apple Music of his Cambridge post-punk outfit’s debut LP. “I think that\'s basically all it can be, and that\'s the best it can be.” Intended to capture the spark of their early years—and electrifying early performances—*For the First Time* is an urgent collision of styles and signifiers, a youthful tangling of Slint-ian post-rock and klezmer meltdowns, of lowbrow and high, Kanye and the Fonz, Scott Walker and “the absolute pinnacle of British engineering.” Featuring updates to singles “Sunglasses” and “Athens, France,” it’s also a document of their banding together after the public demise of a previous incarnation of the outfit, when all they wanted to do was be in a room with one another again, playing music. “I felt like I was able to be good with these people,” Wood says of his six bandmates. “These were the people who had taught me and enabled me to be a good musician. Had I played the record back to us then, I would be completely over the moon about it.” Here, Wood walks us through the album start to finish. **Instrumental** “It was the first piece we wrote. So to fit with making an accurate presentation of our sound or our journey as musicians, we thought it made sense to put one of the first things we wrote first.” **Athens, France** “We knew we were going to be rerecording it, so I listened back to the original and I thought about what opportunities I might take to change it up. I just didn\'t do the best job at saying the thing I was wanting to say. And so it was just a small edit, just to try and refine the meaning of the song. It wouldn’t be very fun if I gave that all away, but the simplest—and probably most accurate—way to explain it would be that the person whose perspective was on this song was most certainly supposed to be the butt of a joke, and I think it came across that that wasn\'t the case, and that\'s what made me most uncomfortable.” **Science Fair** “I’m not so vividly within this song; I’m more of an outsider. I have a fair amount of personal experience with science fairs. I come from Cambridge—and most of the band do as well—and there\'s many good science fairs and engineering fairs around there that me and my father would attend quite frequently. It’s a funny thing, something that I did a lot and never thought about until the minute that the idea for the song came into my head. It’s the sort of thing that’s omnipresent, but in the background. It\'s the same with talking about the Cirque du Soleil: Just their plain existence really made me laugh.” **Sunglasses** “It was a genuine realization that I felt slightly more comfortable walking down the street if I had a pair of sunglasses on. It wasn\'t necessarily meditating on that specific idea, but it was jotted down and then expanded and edited, expanded and messed around with, and then became what it was. Sunglasses exist to represent any object, those defense mechanisms that I recognize in myself and find in equal parts effective and kind of pathetic. Sometimes they work and other times they\'re the thing that leads to the most narcissistic, false, and ignorant ways of being. I just broke the pair that my fiancée bought for me, unfortunately. Snapped in half.” **Track X** “I wrote that riff ages and ages ago, around the time I first heard *World of Echo* by Arthur Russell, which is possibly my favorite record of all time. I was playing around with the same sort of delay effects that he was using, trying to play some of his songs on guitar, sort of translate them from the cello. We didn\'t play it for ages and ages, and then just before we recorded this album, we had the idea to resurrect it and put it together with an old story that I had written. It’s a love story—love and loss and all that\'s in between. It just made sense for it to be something quieter, calmer. And because it was arranged most recently, it definitely gives the most glimpse of our new material.” **Opus** “‘Opus’ and ‘Instrumental’ were written on the same day. We were in a room together without any music prepared, for the first time in a few months, and we were all feeling quite down. It was a highly emotional time, and I think the music probably equal parts benefits and suffers from that. It\'s rich with a fair amount of typical teenage angst and frustration, even though we were sort of past our teens by that point. I mean, it felt very strange but very, very good to be playing together again. It took us a little while to realize that we might actually be able to do it. It was just a desire to get going and to make something new for ourselves, to build a new relationship musically with each other and the world, to just get out there and play a show. We didn\'t really have our sights set particularly high—we just really wanted to play live at the pub.”

“I wanted to get a better sense of how African traditional cosmologies can inform my life in a modern-day context,” Sons of Kemet frontman Shabaka Hutchings tells Apple Music about the concept behind the British jazz group’s fourth LP. “Then, try to get some sense of those forms of knowledge and put it into the art that’s being produced.” Since their 2013 debut LP *Burn*, the Barbados-raised saxophonist/clarinetist and his bandmates (tuba player Theon Cross and drummers Tom Skinner and Eddie Hick) have been at the forefront of the new London jazz scene—deconstructing its conventions by weaving a rich sonic tapestry that fuses together elements of modal and free jazz, grime, dub, ’60s and ’70s Ethiopian jazz, and Afro-Caribbean music. On *Black to the Future*, the Mercury Prize-nominated quartet is at their most direct and confrontational with their sociopolitical message—welcoming to the fold a wide array of guest collaborators (most notably poet Joshua Idehen, who also collaborated with the group on 2018’s *Your Queen Is a Reptile*) to further contextualize the album’s themes of Black oppression and colonialism, heritage and ancestry, and the power of memory. If you look closely at the song titles, you’ll discover that each of them makes up a singular poem—a clever way for Hutchings to clue in listeners before they begin their musical journey. “It’s a sonic poem, in that the words and the music are the same thing,” Hutchings says. “Poetry isn\'t meant to be descriptive on the surface level, it\'s descriptive on a deep level. So if you read the line of poetry, and then you listen to the music, a picture should emerge that\'s more than what you\'d have if you considered the music or the line separately.” Here, Hutchings gives insight into each of the tracks. **“Field Negus” (feat. Joshua Idehen)** “This track was written in the midst of the Black Lives Matter protests in London, and it was a time that was charged with an energy of searching for meaning. People were actually starting to talk about Black experience and Black history as it related to the present, in a way that hadn\'t really been done in Britain before. The point of artists is to be able to document these moments in history and time, and be able to actually find a way of contextualizing them in a way that\'s poetic. The aim of this track is to keep that conversation going and keep the reflections happening. I\'ve been working with Joshua for 15 years and I really appreciate his perspective on the political realm. He\'s got a way of describing reality in a manner which makes you think deeply. He never loses humor and he never loses his sense of sharpness.” **“Pick Up Your Burning Cross” (feat. Moor Mother & Angel Bat Dawid)** “It started off with me writing the bassline, which I thought was going to be a grime bassline. But then in the pandemic lockdown, I added layers of horns and woodwinds. It took it completely out of the grime space and put it more in that Antillean-Caribbean atmosphere. It really showed me that there\'s a lot of intersecting links between these musics that sometimes you\'re not even aware of until you start really diving into their potential and start adding and taking away things. It was really great to actually discover that the tune had more to offer than I envisioned in the beginning. Angel Bat Dawid and Moor Mother are both on this one, and the only thing I asked them to do was to listen to the track and just give their honest interpretation of what the music brings out of them.” **“Think of Home”** “If you\'re thinking poetically, you\'ve got that frantic energy of \'Burning Cross,\' which signifies dealing with those issues of oppression. Then at the end of that process of dealing with them, you\'ve got to still remember the place that you come from. You\'ve got to think about the utopia, think about that serene tranquil place so that you\'re not consumed in the battle. It\'s not really trying to be a Caribbean track per se, but I was trying to get that feeling of when I think back to my days growing up in Barbados. This is the feeling I had when I remember the music that was made at that time.” **“Hustle” (feat. Kojey Radical)** “The title of the track links back to the title of our second album, *Lest We Forget What We Came Here to Do*. The answer to that question is to hustle. Our grandparents came and migrated to Britain, not to just be British per se, but so that they could then create a better life for themselves and their families and have the future be one with dignity and pride. I gave these words to Kojey and he said that he finds it difficult to depict these types of struggles considering that he\'s not in the present moment within the same struggle that he grew up in. He felt it was disingenuous for him to talk about the struggle. I told him that he\'s a storyteller, and storytelling isn\'t always autobiographical. His gift is to be able to tell stories for his community, and to remember that he\'s also an orator of their history regardless of where his personal journey has led him.” **“For the Culture” (feat. D Double E)** “Originally, we\'d intended D Double E to be on \'Pick Up Your Burning Cross.\' But he came into the studio and it really wasn\'t the vibe that he was in. We played him the demo of this track and his face lit up. He was like, \'Let\'s go into the studio. I know what to do.\' It was one take and that was it. I think this might be one of my favorite tunes on the album. The reason I called it \'For the Culture\' is that it puts me back into what it felt like to be a teenager in Barbados in the \'90s, going into the dance halls and really learning what it is to dance. It\'s not just all about it being hard and struggling and striving; there is that fun element of celebrating what it is to be sensual and to be alive and love music and partying and just joyfulness.” **“To Never Forget the Source”** “I gave this really short melody to the band, maybe like four bars for the melody and a very repeated bassline. We played it for about half an hour, where the drums and bass entered slowly and I played the melody again and again. The idea of this, when we recorded in the studio, is that it needs to be the vibe and spirit of how we are playing together. So it wasn\'t about stopping and starting and being anxious. We need to play it until the feeling is right. The clarinets and the flutes on this one is maybe the one I\'m most proud of in terms of adding a counterpoint line, which really offsets and emphasizes the original saxophone and tuba line.” **“In Remembrance of Those Fallen”** “The idea of \'In Remembrance of Those Fallen\' is to give homage to those people that have been fighting for liberation and freedom within all those anti-colonial movements, and remember the ongoing struggle for dignity within especially the Black world in Africa. It\'s trying to get that feeling of \'We can do this. We can go forward, regardless of what hurdles have been done and of what hurdles we\'ve encountered.\' But, musically, there\'s so many layers to this. I was excited with how, on one side, the drums are doing what you\'d describe as Afro-jazz, and on the other one, it\'s doing a really primal sound—but mixing it in a way where you feel the impact of those two contrasting drum patterns. This is at the heart of what I like about the drums in Kemet. Regardless of what they\'re doing, the end result becomes one pulsating, forward-moving machine.” **“Let the Circle Be Unbroken”** “I was listening to a lot of \[Brazilian composer\] Hermeto Pascoal while making the album, and my mind was going onto those beautiful melodies that Hermeto sometimes makes. Songs that feel like you remember them, but they\'ve got a level of harmonic intricacy, which means that there\'s something disorienting too. It\'s like you\'re hearing a nursery rhyme in a dream, hearing the basic contour of the melody, but there\'s just something below the surface that disorientates you and throws you off what you know of it. It\'s one of the only times I\'ve ever heard that midtempo soca descend into brutal free jazz.” **“Envision Yourself Levitating”** “This one also features one of my heroes on the saxophone, Kebbi Williams, who does the first saxophone solo on the track. His music has got that real New Orleans communal vibe to it. For me, this is the height of music making—when you can make music that\'s easy enough to play its constituent parts, but when it all pieces together, it becomes a complex tapestry. It\'s the first point in the album where I do an actual solo with backing parts. This is, in essence, what a lot of calypso bands do in Barbados. So when you\'ve got traditional calypso music, you\'ll get a performer who is singing their melody and then you\'ve got these horn section parts that intersect and interact with the melody that the calypsonian is singing. It\'s that idea of an interchange between the band backing the chief melodic line.” **“Throughout the Madness, Stay Strong”** “It\'s about optimism, but not an optimism where you have a smile on your face. An optimism where you\'re resigned to the place of defeat within the big spectrum of things. It\'s having to actually resign yourself to what has happened in the continued dismantling of Black civilization, and how Black people are regarded as a whole in the world within a certain light; but then understanding that it\'s part of a broader process of rising to something else, rising to a new era. Also, on the more technical side of the recording of this tune, this was the first tune that we recorded for the whole session. It\'s the first take of the first tune on the first day.” **“Black” (feat. Joshua Idehen)** “There was a point where we all got into the studio and I asked that we go into these breathing exercises where we essentially just breathe in really deeply about 30 times, and at the end of 30, we breathe out and hold it for as long as you can with nothing inside. We did one of these exercises while lying on the floor with our eyes shut in pitch blackness. I asked everyone to scream as hard as we can, really just let it out. No one could have anything in their ears apart from the track, so no one was aware of how anyone else sounded. It was complete no-self-awareness, no shyness. It\'s like a cathartic ritual to really just let it out, however you want.”

In August 2019, New York singer-songwriter Cassandra Jenkins thought she had the rest of her year fully mapped out, starting with a tour of North America as a guitarist in David Berman’s newly launched project Purple Mountains. But when Berman took his own life that month, everything changed. “All of a sudden, I was just unmoored and in shock,” she tells Apple Music. “I really only spent four days with David. But those four days really knocked me off my feet.” For the next few months, she wrote as she reflected, obsessively collecting ideas and lyrics, as well as recordings of conversations with friends and strangers—cab drivers and art museum security guards among them. The result is her sophomore LP, a set of iridescent folk rock that came together almost entirely over the course of one week, with multi-instrumentalist Josh Kaufman in his Brooklyn studio. “I was trying to articulate this feeling of getting comfortable with chaos,” she says. “And learning how to be comfortable with the idea that things are going to fall apart and they\'re going to come back together. I had shed a lot of skin very quickly.” Here, Jenkins tells us the story of each song on the album. **Michelangelo** “I think sequencing the record was an interesting challenge because, to me, the songs feel really different from one another. ‘Michelangelo’ is the only one that I came in with that was written—I had a melody that I wanted to use and I thought, ‘Okay, Josh, let’s make this into a little rock song and take the guitar solo in the middle.’ That was the first song we recorded, so it was just our way of getting into the groove of recording, with what sounds like a familiar version of what I\'ve done in the past.” **New Bikini** “I was worried when I was writing it that it sounded too starry-eyed and a little bit naive, saying, ‘The water cures everything.’ I think it was this tension between that advice—from a lot of people with good intentions—and me being like, ‘Well, it\'s not going to bring this person back from the dead and it\'s not going to change my DNA and it\'s not going to make this person better.’” **Hard Drive** “I just love talking to people, to strangers. The heart of the song is people talking about the nature of things, but often, what they\'re doing is actually talking about themselves and expressing something about themselves. I think that every person that I meet has wisdom to give and it\'s just a matter of turning that key with people. Because when you turn it and you open that door, you can be given so much more than you ever expected. Really listening, being more of a journalist in my own just day-to-day life—rather than trying to influence my surroundings, just letting them hit me.” **Crosshairs** “You could look at this as a kind of role-playing song, which isn\'t explicitly sexual, but that\'s definitely one aspect of it. It’s the idea that when you\'re assuming a different role within yourself, it actually can open up chambers within you that are otherwise not seeing the light of day. I was looking at the parts of me that are more masculine, the parts of me that are explicitly feminine, and seeing where everything is in between, while also trying to do the same for someone else in my life.” **Ambiguous Norway** “The song is titled after one of David\'s cartoons, a drawing of a house with a little pinwheel on the top. It\'s about that moment where I was experiencing this grief of David passing away, where I was really saturated in it. I threw myself onto this island in Norway—Lyngør—thinking I could sort of leave that behind to a certain extent, and just realizing that it really didn\'t matter what corner of the planet I found myself on, I was still interacting with the impression of David\'s death and finding that there was all of these coincidences everywhere I went. I felt like I was in this wide-eyed part of the grieving process where it becomes almost psychedelic, like I was seeing meaning in everything and not able at all to just put it into words because it was too big and too expansive.” **Hailey** “It\'s challenging to write a platonic love song—it doesn\'t have all the ingredients of heartbreak or lust or drama that I think a lot of those songs have. It\'s much more simple than that. I just wanted to celebrate her and also celebrate someone who\'s alive now, who\'s making me feel motivated to keep going when things get tough, and to have confidence in myself, because that\'s a really beautiful thing and it\'s rare to behold. I think a lot of the record is mourning, and this was kind of the opposite.” **The Ramble** “I made these binaural recordings as I walked around and birdwatched in the morning, in April \[2020\], when it was pretty much empty. I was a stone\'s throw away from all the hospitals that were cropping up in Central Park, while simultaneously watching nature flourish in this incredible way. I recorded a guitar part and then I sent that to all of my friends around the country and said, ‘Just write something, send it back to me. Don\'t spend a lot of time on it.’ I wanted to capture the feeling that things change, but it’s nature\'s course to find its way through. Just to go out with my binoculars and be in nature and observe birds is my way of really dissolving and letting go of a lot of my fears and anxieties—and I wanted to give that to other people.”

In his native country of Niger, singer-songwriter Mdou Moctar taught himself to play guitar by watching videos of Eddie Van Halen’s iconic shredding. When you hear his unique psych-rock hybrid—a mix of traditional Tuareg melodies with the kinds of buzzing strings and trilling fret runs that people often associate with the recently deceased guitar god—it makes sense. Moctar has honed that stylistic fingerprint over the course of five albums, after first being introduced to Western audiences via Sahel Sounds’ now cult classic compilation *Music From Saharan Cellphones, Vol. 1*, and in the process has been heartily embraced by indie rock fans based on his sound alone (he also plays on Bonnie \"Prince” Billy and Matt Sweeney’s *Superwolves* album). The songs that make up *Afrique Victime* alternate between jubilant, sometimes meandering and jammy (the opening “Chismiten”)—mirroring his band’s explosive live shows—and more tightly wound, raga-like and reflective (the trance-inducing “Ya Habibti”). But within the music, there’s a deeper, often political context: Recorded with his group in studios, apartments, hotel rooms, backstage, and outdoors, the album covers a range of themes: love, religion, women’s rights, inequality, and the exploitation of West Africa by colonial powers. “I felt like giving a voice to all those who suffer on my continent and who are ignored by the Western world,” Moctar tells Apple Music. Here he dissects each of the album’s tracks. **“Chismiten”** “The song talks about jealousy in a relationship, but more importantly about making sure that you’re not swept away too quickly by this emotion, which I think can be very harmful. Every individual, man or woman, has the right to have relationships outside marriage, be it with friends or family.” **“Taliat”** “It’s another song that addresses relationships, the suffering we go through when we’re deeply in love with someone who doesn’t return that love.” **“Ya Habibti”** “The title of this track, which I composed a long time ago, means ‘oh my love’ in Arabic. I reminisce about that evening in August when I met my wife and how I immediately thought she was so beautiful.” **“Tala Tannam”** “This is also a song I wrote for my wife when I was far away from her, on a trip. I tell her that wherever I may be, I’ll be thinking of her.” **“Asdikte Akal”** “It’s about my origins and the sense of nostalgia I feel when I think about the village where I grew up, about my country and all those I miss when I’m far away from them, like my mother and my brothers.” **“Layla”** “Layla is my wife. When she gave birth to our son, I wasn’t allowed to be by her side, because that’s just how it is for men in our country. I was on tour when she called me, very worried, to tell me that our son was about to be born. I felt really helpless, and as a way of offering comfort, I wrote this song for her.” **“Afrique Victime”** “Although my country gained its independence a long time ago, France had promised to help us, but we never received that support. Most of the people in Niger don’t have electricity or drinking water. That’s what I emphasize in this song.” **“Bismilahi Atagah”** “This one talks about the various possible dangers that await us, about everything that could make us turn our back on who we really are, such as the illusion of love and the lure of money.”

Over the course of her first four albums as The Weather Station, Toronto’s Tamara Lindeman has seen her project gradually blossom from a low-key indie-folk oddity into a robust roots-rock outfit powered by motorik rhythms and cinematic strings. But all that feels like mere baby steps compared to the great leap she takes with *Ignorance*, a record where Lindeman soundly promotes herself from singer-songwriter to art-rock auteur (with a dazzling, Bowie-worthy suit made of tiny mirrors to complete the transformation). It’s a move partly inspired by the bigger rooms she found herself playing in support of her 2017 self-titled release, but also by the creative stasis she was feeling after a decade spent in acoustic-strummer mode. “Whenever I picked up the guitar, I just felt like I was repeating myself,” Lindeman tells Apple Music. “I felt like I was making the same decisions and the same chord changes, and it just felt a little stale. I just really wanted to embrace some of this other music that I like.” To that end, Lindeman built *Ignorance* around a dream-team band, pitting pop-schooled players like keyboardist John Spence (of Tegan and Sara’s live band) and drummer Kieran Adams (of indie electro act DIANA) against veterans of Toronto’s improv-jazz scene, like saxophonist Brodie West and flautist Ryan Driver. The results are as rhythmically vigorous as they are texturally scrambled, with Lindeman’s pristine Christine McVie-like melodies mediating between the two. Throughout the record, Lindeman distills the biggest, most urgent issues of the early 2020s—climate change, social injustice, unchecked capitalism—into intimate yet enigmatic vignettes that convey the heavy mental toll of living in a world that seems to be slowly caving in from all sides. “With a lot of the songs on the record, it could be a personal song or it could be an environmental song,” Lindeman explains. “But I don\'t think it matters if it\'s either, because it\'s all the same feelings.” Here, Lindeman provides us with a track-by-track survey of *Ignorance*’s treacherous psychic terrain. **Robber** “It\'s a very strange thing to be the recipient of something that\'s stolen, which is what it means to be a non-Indigenous Canadian. We\'re all trying to grapple with the question of: What does it mean to even be here at all? We\'re the beneficiaries of this long-ago genocide, essentially. I think Canadians in general and people all over the world are sort of waking up to our history—so to sing \'I never believed in the robber\' sort of feels like how we all were taught not to see certain things. The first page in the history textbook is: ‘People lived here.’ And then the next 265 pages are all about the victors—the takers.” **Atlantic** “I was thinking about the weight of the climate crisis—like, how can you look out the window and love the world when you know that it is so threatened, and how that threat and that grief gets in the way of loving the world and being able to engage with it.” **Tried to Tell You** “Something I thought about a lot when I was making the album was how strange our society is—like, how we’ve built a society on a total lack of regard for biological life, when we are biological. Our value system is so odd—it\'s ahuman in this funny way. We\'re actually very soft, vulnerable creatures—we fall in love easily and our hearts are so big. And yet, so much of the way that we try to be is to turn away from everything that\'s soft and mysterious and instinctual about the way that we actually are. There\'s a distinct lack of humility in the way that we try to be, and it doesn\'t do us any good. So this just started out as a song about a friend who was turning away from someone that they were very clearly deeply in love with, but at the same time, I felt like I was writing about everyone, because everyone is turning away from things that we clearly deeply love.” **Parking Lot** “What\'s beautiful about birds is that they\'re everywhere, and they show up in our big, shitty cities, and they\'re just this constant reminder of the nonhuman perspective—like when you really watch a bird, and you try to imagine how it\'s perceiving the world around it and why it\'s doing what it does. For me, there\'s such a beauty in encountering the nonhuman, but also a sadness, and those two ideas are connected in the song.” **Loss** “This song started with that chord change and that repetition of \'loss is loss is loss is loss.\' So I stitched in a snapshot of a person—I don\'t know who—having this moment where they realize that the pain of trying to avoid the pain is not as bad as the pain itself. The deeper feeling beneath that avoidance is loss and sadness and grief, so when you can actually see it, and acknowledge that loss is loss and that it\'s real, you also acknowledge the importance of things. I took a quote from a friend of mine who was talking about her journey into climate activism, and she said, ‘At some point, you have to live as if the truth is true.’ I just loved that, so I quoted her in the song, and I think about that line a lot.\" **Separated** “With some of these songs, I\'m almost terrified by some of the lyrics that I chose to include—I\'m like, \'What? I said that?\' To be frank, I wrote this song in response to the way that people communicate on social media. There\'s so much commitment: We commit to disagree, we commit to one-upping each other and misunderstanding each other on purpose, and it\'s not dissimilar to a broken relationship. Like, there\'s a genuine choice being made to perpetuate the conflict, and I feel like that\'s not really something we like to talk about.” **Wear** “This one\'s a slightly older song. I think I wrote it when I was still out on the road touring a lot. And it just seemed like the most perfect, deep metaphor: ‘I tried to wear the world like some kind of garment.’ I\'m always really happy when I can hit a metaphor that has many layers to it, and many threads that I can pull out over the course of the song—like, the world is this garment that doesn\'t fit and doesn\'t keep you warm and you can\'t move in. And you just want to be naked, and you want to take it off and you want to connect, and yet you have to wear it. I think it speaks to a desire to understand the world and understand other people—like, \'Is everyone else comfortable in this garment, or is it just me that feels uncomfortable?\'” **Trust** “This song was written in a really short time, and that doesn\'t usually happen to me, because I usually am this very neurotic writer and I usually edit a lot and overthink. It\'s a very heavy song. And it\'s about that thing that\'s so hard to wrap your head around when you\'re an empathetic person: You want to understand why some people actively choose conflict, why they choose to destroy. I wasn\'t actually thinking about a personal relationship when I wrote this song; I was thinking about the world and various things that were happening at the time. I think the song is centered in understanding the softness that it takes to stand up for what matters, even when it\'s not cool.” **Heart** “Along with \'Robber,\' this was one of my favorite recording moments. It had a pretty loose shape, and there\'s this weird thing that I was obsessed with where the one chord is played through the whole song, and everything is constantly tying back to this base. I just loved what the band did and how they took it in so many different directions. This song really freaked me out \[lyrically\]. I was not comfortable with it. But I was talked into keeping it, and all for the better, because obviously, I do believe that the sentiments shared on the song—though they are so, so fucking soft!—are the best things that you can share.” **Subdivisions** “This was one of the first songs written before the record took shape in my mind and before it structurally came together. I think we recorded it in, like, an hour, and everyone\'s performance was just perfect. I like these big, soft, emotional songs, and from a craft perspective, I think it\'s one of my better songs. I\'ve never really written a chorus like that. I don\'t even feel like it\'s my song. I don\'t feel like I wrote it or sang it, but it just feels like falling deeper and deeper into some very soft place—which is, I think, the right way to end the record.”

Listening to Liz Harris’ music as Grouper, the word that comes to mind is “psychedelic.” Not in the cartoonish sense—if anything, the Astoria, Oregon-based artist feels like a monastic antidote to spectacle of almost any kind—but in the subtle way it distorts space and time. She can sound like a whisper whose words you can’t quite make out (“Pale Interior”) and like a primal call from a distant hillside (“Followed the ocean”). And even when you can understand what she’s saying, it doesn’t sound like she meant to be heard (“The way her hair falls”). The paradox is one of closeness and remove, of the intimacy of singer-songwriters and the neutral, almost oracular quality of great ambient music. That the tracks on *Shade*, her 12th LP, were culled from a 15-year period is fitting not just because it evokes Harris’ machine consistency (she found her creative truth and she’s sticking to it), but because of how the staticky, white-noise quality of her recordings makes you aware of the hum of the fridge and the hiss of the breeze: With Grouper, it’s always right now.

“Sometimes I’ll be in my own space, my own company, and that’s when I\'m really content,” Little Simz tells Apple Music. “It\'s all love, though. There’s nothing against anyone else; that\'s just how I am. I like doing my own thing and making my art.” The lockdowns of 2020, then, proved fruitful for the North London MC, singer, and actor. She wrestled writer’s block, revived her cult *Drop* EP series (explore the razor-sharp and diaristic *Drop 6* immediately), and laid grand plans for her fourth studio album. Songwriter/producer Inflo, co-architect of Simz’s 2019 Mercury-nominated, Ivor Novello Award-winning *GREY Area*, was tapped and the hard work began. “It was straight boot camp,” she says of the *Sometimes I Might Be Introvert* sessions in London and Los Angeles. “We got things done pronto, especially with the pace that me and Flo move at. We’re quite impulsive: When we\'re ready to go, it’s time to go.” Months of final touches followed—and a collision between rap and TV royalty. An interest in *The Crown* led Simz to approach Emma Corrin (who gave an award-winning portrayal of Princess Diana in the drama). She uses her Diana accent to offer breathless, regal addresses that punctuate the 19-track album. “It was a reach,” Simz says of inviting Corrin’s participation. “I’m not sure what I expected, but I enjoyed watching her performance, and wrote most of her words whilst I was watching her.” Corrin’s speeches add to the record’s sense of grandeur. It pairs turbocharged UK rap with Simz at her most vulnerable and ambitious. There are meditations on coming of age in the spotlight (“Standing Ovation”), a reunion with fellow Sault collaborator Cleo Sol on the glorious “Woman,” and, in “Point and Kill,” a cleansing, polyrhythmic jam session with Nigerian artist Obongjayar that confirms the record’s dazzling sonic palette. Here, Simz talks us through *Sometimes I Might Be Introvert*, track by track. **“Introvert”** “This was always going to intro the album from the moment it was made. It feels like a battle cry, a rebirth. And with the title, you wouldn\'t expect this to sound so huge. But I’m finding the power within my introversion to breathe new meaning into the word.” **“Woman” (feat. Cleo Sol)** “This was made to uplift and celebrate women. To my peers, my family, my friends, close women in my life, as well as women all over the world: I want them to know I’ve got their back. Linking up with Cleo is always fun; we have such great musical chemistry, and I can’t imagine anyone else bringing what she did to the song. Her voice is beautiful, but I think it\'s her spirit and her intention that comes through when she sings.” **“Two Worlds Apart”** “Firstly, I love this sample; it’s ‘The Agony and the Ecstasy’ by Smokey Robinson, and Flo’s chopped it up really cool. This is my moment to flex. You had the opener, followed by a nice, smoother vibe, but this is like, ‘Hey, you’re listening to a *rap* album.’” **“I Love You, I Hate You”** “This wasn’t the easiest song for me to write, but I\'m super proud that I did. It’s an opportunity for me to lay bare my feelings on how that \[family\] situation affected me, growing up. And where I\'m at now—at peace with it and moving on.” **“Little Q, Pt. 1 (Interlude)”** “Little Q is my cousin, Qudus, on my dad\'s side. We grew up together, but then there was a stage where we didn\'t really talk for some years. No bad blood, just doing different things, so when we reconnected, we had a real heart-to-heart—and I heard about all he’d been through. It made me feel like, ‘Damn, this is a blood relative, and he almost lost his life.’ I thank God he didn’t, but I thought of others like him. And I felt it was important that his story was heard and shared. So, I’m speaking from his perspective.” **“Little Q, Pt. 2”** “I grew up in North London and \[Little Q\] was raised in South, and as much as we both grew up in endz, his experience was obviously different to mine. Being a product of an environment or system that isn\'t really for you, it’s tough trying to navigate that.” **“Gems (Interlude)”** “This is another turning point, reminding myself to take time: ‘Breathe…you\'re human. Give what you can give, but don\'t burn out for anyone. Put yourself first.’ Just little gems that everyone needs to hear once in a while.” **“Speed”** “This track sends another reminder: ‘This game is a marathon, not a sprint. So pace yourself!’ I know where I\'m headed, and I\'m taking my time, with little breaks here and there. Now I know when to really hit the gas and also when to come off a bit.” **“Standing Ovation”** “I take some time to reflect here, like, ‘Wow, you\'re still here and still going. It’s been a slow burn, but you can afford to give yourself a pat on the back.’ But as well as being in the limelight, let\'s also acknowledge the people on the ground doing real amazing work: our key workers, our healers, teachers, cleaners. If you go to a toilet and it\'s dirty, people go in from 9 to 5 and make sure that shit is spotless for you, so let\'s also say thank you.” **“I See You”** “This is a really beautiful and poetic song on love. Sometimes as artists we tend to draw from traumatic times for great art, we’re hurt or in pain, but it was nice for me to be able to draw from a place of real joy in my life for this song. Even where it sits \[on the album\]: right in the center, the heart.” **“The Rapper That Came to Tea (Interlude)”** “This title is a play on \[Judith Kerr’s\] children\'s book *The Tiger Who Came to Tea*, and this is about me better understanding my introversion. I’m just posing questions to myself—I might not necessarily have answers for them, I think it\'s good to throw them out there and get the brain working a bit.” **“Rollin Stone”** “This cut reminds me somewhat of ’09 Simz, spitting with rapidness and being witty. And I’m also finding new ways to use my voice on the second half here, letting my evil twin have her time.” **“Protect My Energy”** “This is one of the songs I\'m really looking forward to performing live. It’s a stepper, and it got me really wanting to sing, to be honest. I very much enjoy being around good company, but these days I enjoy my personal space and I want to protect that.” **“Never Make Promises (Interlude)”** “This one is self-explanatory—nothing is promised at all. It’s a short intermission to lead to the next one, but at one point it was nearly the album intro.” **“Point and Kill” (feat. Obongjayar)** “This is a big vibe! It feels very much like Nigeria to me, and Obongjayar is one of my favorites at the moment. We recorded this in my living room on a whim—and I\'m very, very grateful that he graced this song. The title comes from a phrase used in Nigeria to pick out fish at the market, or a store. You point, they kill. But also metaphorically, whatever I want, I\'m going to get in the same way, essentially.” **“Fear No Man”** “This track continues the same vibe, even more so. It declares: ‘I\'m here. I\'m unapologetically me and I fear no one here. I\'m not shook of anyone in this rap game.’” **“The Garden (Interlude)”** “This track is just amazing musically. It’s about nurturing the seeds you plant. Nurture those relationships, and everything around you that\'s holding you down.” **“How Did You Get Here”** “I want everyone to know *how* I got here; from the jump, school days, to my rap group, Space Age. We were just figuring it out, being persistent. I cried whilst recording this song; it all hit me, like, ‘I\'m actually recording my fourth album.’ Sometimes I sit and I wonder if this is all really true.” **“Miss Understood”** “This is the perfect closer. I could have ended on the last track, easily, but, I don\'t know, it\'s kind of like doing 99 reps. You\'ve done 99, that\'s amazing, but you can do one more to just make it 100, you can. And for me it was like, ‘I\'m going to get this one in there.’”

After decades of lending clutch support to everyone from D’Angelo to The Who, ace session bassist Pino Palladino makes his long-awaited debut on *Notes With Attachments*. The main attachment, enough to share cover billing, is Grammy-winning producer and multi-instrumentalist Blake Mills, who encountered Palladino and drummer Chris Dave (also of D’Angelo’s orbit) while working on John Legend’s 2016 album *Darkness and Light*. Collaborative seeds were sown, and the result is this highly inventive program of instrumentals, steeped in abstract hip-hop beats, leftfield sonics, clustery jazz harmony, and subtle compositional detailing. Palladino’s effortless bass steers but never dominates the set. Mills weighs in on everything from baritone guitar to berimbau, from tres to ngoni, keeping the timbres ever-changing. Chris Dave’s groove aesthetic is central enough to get an entire track named after him. But there’s also Senegalese percussion from Ben Aylon (on “Chris Dave” and “Man From Molise”), dollops of Andrew Bird’s violin on the Afrobeat-inspired “Ekuté,” and crafty organ, mellotron, and synth work from jazz great Larry Goldings on half the album as well. In terms of melody, texture, harmony, and counterpoint, the saxophonists are also essential: Sam Gendel cuts through on nearly every track, while guests Jacques Schwarz-Bart (on “Soundwalk”) and Marcus Strickland (on “Ekuté,” playing mainly bass clarinet) enhance the music’s dark and hazy lyricism.

Ahead of its release, Vince Staples told Apple Music\'s Zane Lowe that his eponymous album was a more personal work than those that came before. The Long Beach rapper has never shied away from bringing the fullness of his personality to his music—it\'s what makes him such a consistently entertaining listen—but *Vince Staples*, aided by Kenny Beats, who produced the project, is more clear-eyed than ever. Opener “ARE YOU WITH THAT?” is immediate: “Whenever I miss those days/Visit my Crips that lay/Under the ground, runnin\' around, we was them kids that played/All in the street, followin\' leads of n\*\*\*as who lost they ways,” he muses in the second verse, assessing the misguided aspirations that marked his childhood even as the threat of violence and death loomed. It\'s not that Staples hasn\'t broached these topics before—it\'s that he\'s rarely been this explicit regarding his own feelings about them. His sharp matter-of-factness and acerbic humor have often masked criticism in piercing barbs and commentary in unflinching bravado. Here, he\'s direct. The songs, like a series of vignettes that don\'t even reach the three-minute mark, feel intimately autobiographical. “SUNDOWN TOWN” reflects on the distrustful mentality that comes with taking losses and having the rug pulled out from under you one too many times (“When I see my fans, I\'m too paranoid to shake their hands”); “TAKE ME HOME” illuminates how the pull of the past, of “home,” can still linger even after you\'ve escaped it (“Been all across this atlas but keep coming back to this place \'cause it trapped us”). Some might call this an album of maturation, but it ultimately seems more like an invitation—Staples finally allowing his fans to know him just a bit more.

“Everybody is scared of death or ultimate oblivion, whether you want to admit it or not,” Julien Baker tells Apple Music. “That’s motivated by a fear of uncertainty, of what’s beyond our realm of understanding—whatever it feels like to be dead or before we\'re born, that liminal space. It\'s the root of so much escapism.” On her third full-length, Baker embraces fuller arrangements and a full-band approach, without sacrificing any of the intimacy that galvanized her earlier work. The result is at once a cathartic and unabashedly bleak look at how we distract ourselves from the darkness of voids both large and small, universal and personal. “It was easier to just write for the means of sifting through personal difficulties,” she says. “There were a lot of paradigm shifts in my understanding of the world in 2019 that were really painful. I think one of the easiest ways to overcome your pain is to assign significance to it. But sometimes, things are awful with no explanation, and to intellectualize them kind of invalidates the realness of the suffering. I just let things be sad.” Here, the Tennessee singer-songwriter walks us through the album track by track. **Hardline** “It’s more of a confession booth song, which a lot of these are. I feel like whenever I imagine myself in a pulpit, I don\'t have a lot to say that\'s honest or useful. And when I imagine myself in a position of disclosing, in order to bring me closer to a person, that\'s when I have a lot to say.” **Heatwave** “I wrote it about being stuck in traffic and having a full-on panic attack. But what was causing the delay was just this car that had a factory defect and bomb-style exploded. I was like, ‘Man, someone got incinerated. A family maybe.’ The song feels like a fall, but it\'s born from the second verse where I feel like I\'m just walking around with my knees in gravel or whatever the verse in Isaiah happens to be: the willing submission to suffering and then looking around at all these people\'s suffering, thinking that is a huge obstacle to my faith and my understanding, this insanity and unexplainable hurt that we\'re trying to heal with ideology instead of action.” **Faith Healer** “I have an addictive personality and I understand it\'s easy for me to be an escapist with substances because I literally missed being high. That was a real feeling that I felt and a feeling that felt taboo to say outside of conversations with other people in recovery. The more that I looked at the space that was left by substance or compulsion that I\'ve then just filled with something else, the more I realized that this is a recurring problem in my personality. And so many of the things that I thought about myself that were noble or ultimately just my pursuit of knowing God and the nature of God—that craving and obsession is trying to assuage the same pain that alcohol or any prescription medication is.” **Relative Fiction** “The identity that I have worked so hard to cultivate as a good person or a kind person is all basically just my own homespun mythology about myself that I\'m trying to use to inspire other people to be kinder to each other. Maybe what\'s true about me is true about other people, but this song specifically is a ruthless evaluation of myself and what I thought made me principled. It\'s kind of a fool\'s errand.” **Crying Wolf** “It\'s documenting what it feels like to be in a cyclical relationship, particularly with substances. There was a time in my life, for almost a whole year, where it felt like that. I think that is a very real place that a lot of people who struggle with substance use find themselves in, where the resolution of every day is the same and you just can’t seem to make it stick.” **Bloodshot** “The very first line of the song is talking about two intoxicated people—myself being one of them—looking at each other and me having this out-of-body experience, knowing that we are both bringing to our perception of the other what we need the other person to be. That\'s a really lonely and sad place to be in, the realization that we\'re each just kind of sculpting our own mythologies about the world, crafting our narratives.” **Ringside** “I have a few tics that manifest themselves with my anxiety and OCD, and for a long time, I would just straight-up punch myself in the head—and I would do it onstage. It\'s this extension of physicality from something that\'s fundamentally compulsive that you can\'t control. I can\'t stop myself from doing that, and I feel really embarrassed about it. And for some reason I also can\'t stop myself from doing other kinds of more complicated self-punishment, like getting into codependent relationships and treating each one of those like a lottery ticket. Like, \'Maybe this one will work out.\'” **Favor** “I have a friend whose parents live in Jackson, where my parents live. They’re one of my closest friends and they were around for the super dark part of 2019. I\'ll try to talk to the person who I hurt or I\'ll try to admit the wrongdoing that I\'ve done. I\'ll feel so much guilt about it that I\'ll cry. And then I\'ll hate that I\'ve cried because now it seems manipulative. I\'m self-conscious about looking like I hate myself too much for the wrong things I\'ve done because then I kind of steal the person\'s right to be angry. I don\'t want to cry my way out of shit.” **Song in E** “I would rather you shout at me like an equal and allow me to inhabit this imagined persona I have where I\'m evil. Because then, if I can confirm that you hate me and that I\'m evil and I\'ve failed, then I don\'t any longer have to deal with the responsibility of trying to be good. I don\'t any longer have to be saddled with accountability for hurting you as a friend. It’s something not balancing in the arithmetic of my brain, for sin and retribution, for crime and punishment. And it indebts you to a person and ties you to them to be forgiven.” **Repeat** “I tried so hard for so long not to write a tour song, because that\'s an experience that musicians always write about that\'s kind of inaccessible to people who don\'t tour. We were in Germany and I was thinking: Why did I choose this? Why did I choose to rehash the most emotionally loaded parts of my life on a stage in front of people? But that\'s what rumination is. These are the pains I will continue to experience, on some level, because they\'re familiar.” **Highlight Reel** “I was in the back of a cab in New York City and I started having a panic attack and I had to get out and walk. The highlight reel that I\'m talking about is all of my biggest mistakes, and that part—‘when I die, you can tell me how much is a lie’—is when I retrace things that I have screwed up in my life. I can watch it on an endless loop and I can torture myself that way. Or I can try to extract the lessons, however painful, and just assimilate those into my trying to be better. That sounds kind of corny, but it\'s really just, what other options do you have except to sit there and stare down all your mistakes every night and every day?” **Ziptie** “I was watching people be restrained with zip ties on the news. It\'s just such a visceral image of violence to see people put restraints on another human being—on a demonstrator, on a person who is mentally ill, on a person who is just minding their own business, on a person who is being racially profiled. I had a dark, funny thought that\'s like, what if God could go back and be like, ‘Y\'all aren\'t going to listen.’ Jesus sacrificed himself and everybody in the United States seems to take that as a true fact, and then shoot people in cold blood in the street. I was just like, ‘Why?’ When will you call off the quest to change people that are so horrid to each other?”

It’s likely that only diehard Boldy James fans understand how perfect a complement he is to the Griselda Records roster. The Detroit MC’s focus has always been lyrically proficient street rap, but in 2020 alone, his ear for production would manifest collaborative tapes with beloved Mobb Deep collaborator The Alchemist (*The Price of Tea in China*), jazz musician Sterling Toles (*Manger on McNichols*), social media content creator Jay Versace (*The Versace Tape*), and fashion label/production collective Real Bad Man. The man likes to rap. And if there’s one thing Griselda doesn’t do, it’s hold back projects where their MCs go off. James’ first release of 2021, *Bo Jackson*, clearly fits the mold. Look no further than the album opener “Double Hockey Sticks” for Donald Goines-vivid streetlife scenarios unfurled in James’ signature deadpan: “My bitch scored and hit a game-changer/I made her transport the work in her Keyshia Ka\'oir waist trainer/Say she gon\' leave me and I can’t blame her/’Cause I was cutting up my side bitch raw with the same razor,” he raps. The Alchemist is, here, who he was for *The Price of Tea in China* and the James/Alc collaborative project that preceded that, 2019’s *Boldface*: a producer whose one-of-a-kind loops bring the best out of an MC who never really needed the help.

On his Red Hand Files website, Nick Cave reflected on a comment he’d made back in 1997 about needing catastrophe, loss, and longing in order for his creativity to flourish. “These words sound somewhat like the indulgent posturing of a man yet to discover the devastating effect true suffering can have on our ability to function, let alone to create,” he wrote. “I am not only talking about personal grief, but also global grief, as the world is plunged deeper into this wretched pandemic.” Whether he needs it or not, the Australian songwriter’s music does very often deal with catastrophe, loss, and longing. The pandemic didn’t inspire *CARNAGE* per se, but the challenges of 2020 clearly permitted both intense, lyric-stirring ideas and, with canceled tours and so on, the time and creativity to flesh them out with longtime collaborator and masterful multi-instrumentalist/songwriter Warren Ellis. The most direct reference to COVID-19 might be “Albuquerque,” a sentimental lamentation on the inability to travel. For the most part, Cave looks beyond the pandemic itself, throwing himself into a philosophical realm of meditations on humanity, isolation, love, and the Earth itself, depicted through observations and, as he is wont to do, taking on the roles of several other characters, sentient and otherwise. The album begins with “Hand of God.” There’s soft piano and lyrics about the search for “that kingdom in the sky,” until Ellis\' dissonant violin strikes away the sweetness and an electronic beat kicks in. “I’m going to the river where the current rushes by/I’m gonna swim to the middle where the water is real high,” he sings, a little manically, as he gives in to the current. “Hand of God coming from the sky/Gonna swim to the middle and stay out there awhile… Let the river cast its spell on me.” That unmitigated strength of nature is central to *CARNAGE*. Motifs of rivers, rain, animals, fields, and sunshine are used to depict not only the beauty and the bedlam he sees in the world, but the ways it changes him. On the sweet, delicate “Lavender Fields,” he sings of “traveling appallingly alone on a singular road into the lavender fields… the lavender has stained my skin and made me strange.” On “Carnage,” he sings of loss (“I always seem to be saying goodbye”), but also of love and hope, later depicting a “reindeer, frozen in the footlights,” who then escapes back into the woods. “It’s only love, with a little bit of rain,” goes the uplifting refrain. With its murky rhythm and snarling spoken-word lyrics, “White Elephant” is one of Cave’s most intense songs in years. It’s also the song that most explicitly references a 2020 event: the murder of George Floyd. “The white hunter sits on his porch with his elephant gun and his tears/He\'ll shoot you for free if you come around here/A protester kneels on the neck of a statue, the statue says, ‘I can’t breathe’/The protester says, ‘Now you know how it feels’ and he kicks it into the sea.” Later, he continues, as the hunter: “I’ve been planning this for years/I’ll shoot you in the f\*\*king face if you think of coming around here/I’ll shoot you just for fun.” It’s one of the only Nick Cave songs to ever address a racially, politically charged event so directly. And it’s a dark, powerful moment on this album. *CARNAGE* ends with a pair of atmospheric ballads—their soundscapes no doubt influenced by Cave and Ellis’ extensive work on film scores. On “Shattered Ground,” the exodus of a girl (a personification of the moon) invokes peaceful, muted pain—“I will be all alone when you are gone… I will not make a single sound, but come softly crashing down”—and “Balcony Man” depicts a man watching the sun and considering how “everything is ordinary, until it’s not,” tweaking an idiom with serene acceptance: “You are languid and lovely and lazy, and what doesn’t kill you just makes you crazier.” There is substantial pain, darkness, and loss on this album, but it doesn’t rip its narrator apart or invoke retaliation. Rather, he takes it all in, allowing himself to be moved and changed even if he can’t effect change himself. That challenging sense of being unable to do anything more than *observe* is synonymous with the pandemic, and more broadly the evolving, sometimes devastating world. Perhaps the lesson here is to learn to exist within its chaos—but to always search for beauty and love in its cracks.

Take the irony Steely Dan applied to Boomer narcissists in the ’70s and map it onto the introverts of Gen Z and you get some idea of where Atlanta singer-songwriter Faye Webster is coming from. Like Steely Dan, the sound is light—in Webster’s case, a gorgeous mix of indie rock, country, and soul—but the material is often sad. And even when she gets into it, she does so with the practiced detachment of someone who glazes over everything with a joke. Her boyfriend dumps her by saying he has more of the world to see, then starts dating a girl who looks just like her (“Sometimes”). She might just take the day off to cry in bed (“A Stranger”). And when all that thinking doesn’t make her feel better, she suggests having some sake and arguing about the stuff you always argue about (“I Know I’m Funny haha”). On the advice of the great Oscar the Grouch, Faye Webster doesn’t turn her frown upside down—she lets it be her umbrella.

All rippers, no skippers, Sarah Tudzin’s second album as Illuminati Hotties imbues hooky Y2K-era pop-punk with an attitude that feels distinctly contemporary. Stretching her sweet-and-sour voice like taffy, Tudzin sings from the perspective of a millennial slacker who isn’t quite buying what society’s selling, be it marketing scams (“Threatening Each Other re: Capitalism”) or too-cool-for-school socialites (“Joni: LA’s No. 1 Health Goth”). She’s referred to her scrappy, bruised songs as “tenderpunk,” and beneath all the pool-hopping and kick-flipping, there’s a woman trying to pull off this adulting thing in what feels like end times. But in the meantime, why not try and have some fun?

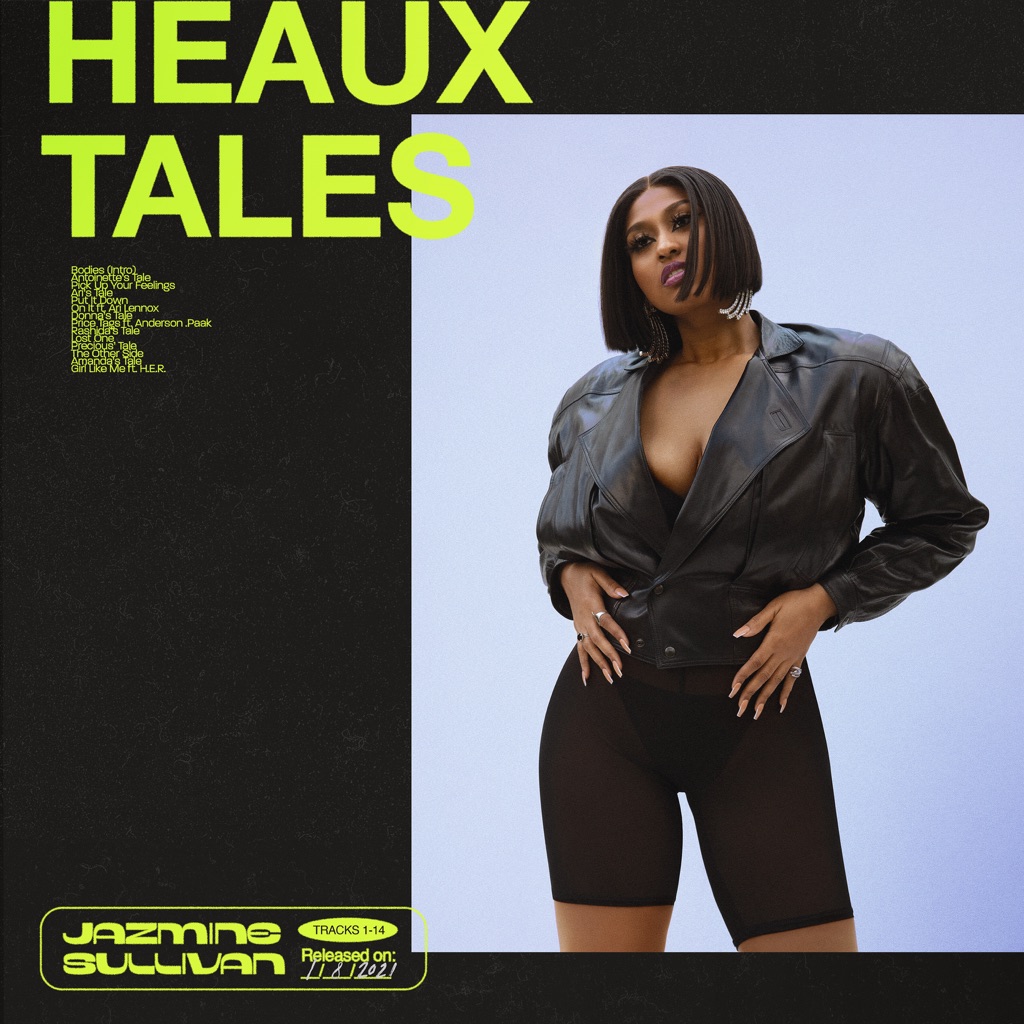

There\'s power in reclamation, and Jazmine Sullivan leans into every bit of it on *Heaux Tales*. The project, her fourth overall and first in six years, takes the content and casual candor of a group chat and unpacks them across songs and narrative, laying waste to the patriarchal good girl/bad girl dichotomy in the process. It\'s as much about “hoes” as it is the people who both benefit from and are harmed by the notion. Pleasure takes center stage from the very beginning; “Bodies” captures the inner monologue of the moments immediately after a drunken hookup with—well, does it really matter? The who is irrelevant to the why, as Sullivan searches her mirror for accountability. “I keep on piling on bodies on bodies on bodies, yeah, you getting sloppy, girl, I gotta stop getting fucked up.” The theme reemerges throughout, each time towards a different end, as short spoken interludes thread it all together. “Put It Down” offers praise for the men who only seem to be worthy of it in the bedroom (because who among us hasn\'t indulged in or even enabled the carnal delights of those who offer little else beyond?), while “On It,” a pearl-clutching duet with Ari Lennox, unfolds like a three-minute sext sung by two absolute vocal powerhouses. Later, she cleverly inverts the sentiment but maintains the artistic dynamism on a duet with H.E.R., replacing the sexual confidence with a missive about how “it ain\'t right how these hoes be winning.” The singing is breathtaking—textbooks could be filled on the way Sullivan brings emotionality into the tone and texture of voice, as on the devastating lead single “Lost One”—but it\'d be erroneous to ignore the lyrics and what these intra- and interpersonal dialogues expose. *Heaux Tales* not only highlights the multitudes of many women, it suggests the multitudes that can exist within a single woman, how virtue and vulnerability thrive next to ravenous desire and indomitability. It stands up as a portrait of a woman, painted by the brushes of several, who is, at the end of it all, simply doing the best she can—trying to love and protect herself despite a world that would prefer she do neither.

As The War on Drugs has grown in size and stature from bedroom recording project to sprawling, festival-headlining rock outfit, Adam Granduciel’s role has remained constant: It’s his band, his vision. But when the pandemic forced recording sessions for their fifth LP *I Don’t Live Here Anymore* to go remote in 2020, Granduciel began encouraging his bandmates to take ownership of their roles within each song—to leave their mark. “Once we got into a groove of sending each other sessions, it was this really cool thing where everyone had a way of working on their own time that really helped,” he tells Apple Music. “I think being friends with the guys now and collaborative for so many years, each time we work together, it\'s like everyone\'s more confident in their role and I’m more confident in my desire for them to step up and bring something real. I was all about giving up control.” That shift, Granduciel adds, opened up “new sonic territory” that he couldn’t have seen by himself. And the sense of peace and perspective that came with it was mirrored—if not made possible—by changes in his personal life, namely the birth of his first child. A decade ago, Granduciel would have likely obsessed and fretted over every detail, making himself unwell in the process, “but I wasn\'t really scared to turn in this record,” he says. “I was excited for it to be out in the world, because it\'s not so much that you don\'t care about your work, but it’s just not the most important thing all the time. I was happy with whatever I could contribute, as long as I felt that I had given it my all.” Here, Granduciel guides us through the entire record, track by track. **“Living Proof”** “It felt like a complete statement, a complete thought. It felt like the solo was kind of composed and was there for a reason, and it all just felt buttoned up perfectly, where it could open a record in kind of a tender way. Just very deliberate and right.” **“Harmonia’s Dream”** “It’s mostly inspired by the band Harmonia and this thing that \[keyboardist\] Robbie \[Bennett\] had done that was blowing my mind in real time. I started playing those two chords, and in the spur of the moment he wrote that whole synth line. We went on for about nine minutes, and I remember, when we were doing it, I was like, ‘Don\'t hit a wrong note.’ Because it was so perfect what he was just feeling out in the moment, at 2 am, at some studio in Brooklyn. I was so lucky that I got to witness him doing that.” **“Change”** “I had started it at the end of 2017’s *Deeper Understanding* and it was like this piano ballad in half-time. Years later, we’re in upstate New York, and I\'m showing it to \[bassist\] Dave \[Hartley\] and \[guitarist\] Anthony \[LaMarca\]. I\'m on piano and they\'re on bass and drums and it\'s not really gelling. At some point Anthony just picks up the drumsticks and he shifts it to the backbeat, this straight-ahead pop-rock four-on-the-floor thing. It immediately had this really cool ‘I\'m on Fire’ vibe.’” **“I Don’t Wanna Wait”** “\[Producer-engineer\] Shawn \[Everett\], for the most part, puts the vocal very front and center on a lot of songs, very pop-like. I think as you get more confident in your songs it\'s okay to have the vocals there. But for this one I was thinking about Radiohead, like it would be cool if we just processed the vocals in this really weird way. I wanted to have fun with them, because we’ve already got so many alien sounds happening with those Prophet keyboards and the moodiness of the drum machine. I wanted to give it something that felt like you were sucked into some weird little world.” **“Victim”** “Ten years ago if we had had this song, we wouldn\'t have a chorus on it—it would just be like a verse over and over. Now I feel like we\'ve progressed to where you have this hypnotic thing but it actually goes somewhere. We’d had it done, but the vocals were a little weird. I told Shawn I wasn’t sure about them, because this song had such a vibe. When he asked me to describe it in one word, I was like, ‘back alley,’ like steam coming out of a fucking manhole cover or something. And then he puts his headphones on and I see him work in some gear for like 30 minutes—and then he turns the speakers on. I was like, ‘Oh, dude. That\'s it.’” **“I Don’t Live Here Anymore”** “I\'ll be the first to say it has that \'80s thing going, but we kind of pushed it in that way. At one point Shawn and I ran everything on the song—drums, the girls, bass, everything—through a JC-120 Roland amplifier, which is like the sound of the \'80s, essentially. I saw it just sitting there at Sound City \[Studios in Los Angeles\]. We spent like a day doing that, and it just gave it this sound that was a familiar heartbeat or something. It sounds huge but it also felt real—in my mind it was basically just a bedroom recording, because everything was done in my tiny little room, directly into my computer.” **“Old Skin”** “I demoed it in one afternoon, in like 30 minutes. Then I showed it to the band, and from the minute we started playing, it was just so fucking boring. But I knew that there was something in the song I really liked, and we kept building it up and building it up, and then one day, I asked Shawn to mute everything except the two things I liked most: the organ and the single note I was playing on the Juno. I brought the drums in at the right moment and it was like, \'Oh, that\'s the fucking song.’ Lyrically, I felt like it was about the concept of pushing back against everything that tries to hold you down—and having a song about that and then having it be as dynamic as it is, with these drums coming out of nowhere, it just feels like a really special moment. It’s my favorite song on the record, I think.” **“Wasted”** “This song was actually a really early one that I kind of abandoned—I sent it to \[drummer\] Pat \[Berkery\] because I knew there was a song there but the drums were just very stale. I didn\'t know any of this, but the day that he was working out of my studio in Philly was the day that his personal life had kind of all come to a head: He was getting divorced from his wife of 15 years. He did the song and he sent it back to me and it was fucking ferocious. It just gave new life to it. Springsteen always talks about Max Weinberg on ‘Born in the U.S.A.’ and how it’s Max\'s greatest recorded performance. I said the same thing when I heard this: ‘It’s Pat’s greatest recorded performance.’” **“Rings Around My Father’s Eyes”** “I\'d been strumming those open chords for a couple years—I had the melody and I had that opening line. I wanted to express something, but I wasn\'t 100% sure how I was going to go about doing it—part of the journey was to not be embarrassed by a line or not think that something is too obvious and too sentimental. As time went on with this record, I became a dad, and I started seeing it from the other side. It’s not so much a reflection on my relationship with my own dad, but starting to think about being a dad, being a protector.” **“Occasional Rain”** “As a songwriter I just love it because it\'s really concise. Lyrically, I was able to wrap up some of the scenes that I wanted to try and talk about, knowing where it was going to go on the record. I just think it\'s one of those songs that\'s a perfect closer. It\'s the last song in our fifth album. It\'s like, if this was the last album we ever made and that was the last song, I\'d be like, ‘That\'s a good way to go out.’”