The Wire's Releases of the Year 2022

On the cover: 2022 Rewind : the year in underground music: Releases Of The Year : We asked our contributors to nominate their top ten records, CDs, downloads and streams of the year, then we added up the votes; Columnists’ Charts : Our specialist critics excavate all crevices of the culture for this year’s most exciting music, from hiphop to modern composition; Books, Films & Events : Emily Bick surveys the year in print, cinema, audiovisual arts and live performance; Critics’ Reflections : Wire writers discuss their cultural highs and lows for 2022. Archive Releases Of The Year : Our contributors voted for their top ten archival records, CDs, downloads and streams, and we counted them all up. Plus: The New Vaudeville : Funny games. By Stewart Smith; Turntablists : Spin cycles. By Rob Turner; Climate : Burning issues. By Phil England; Healing Sounds : Good vibrations. By Emily Pothast; Invisible Jukebox : Kali Malone : Our mystery record selection pulls out all the stops for the composer and organist. Tested by Derek Walmsley. Also inside this issue: Unlimited Editions : REC-on; Unofficial Channels : Xenwiki; Venus Ex Machina ; Daniel Bachman ; Kraus ; Heith ; The Inner Sleeve by Gaye Su Akyol ; Epiphanies by Meg Baird ; many pages of reviews and much more.

Source

Rather than a set of songs, think of Colombian-born, Berlin-based artist Lucrecia Dalt’s eighth album, *¡Ay!*, as a room cast in sound: smokey, low-lit, seductive but vaguely threatening; a place where fantasy and reality meet in deep, inky shadow. Dalt’s takes on the bolero, son, ranchera, and merengue that form the romantic spine of Latin pop are genuine enough to feel folkloric and off-kilter enough to conjure the art and experimental music she’s known for—a contrast that pulls *¡Ay!* along on its hovering, dreamlike course. Squint and you can imagine hearing “Dicen” in a dusty bar somewhere or swaying to “La Desmesura” or “Bochinche.” But like the great exotica artists of the ’50s, Dalt teeters between the foreign and the comforting so gracefully, you don’t recognize how strange she is until you’re in her pocket. *¡Ay!* is lounge music for the beyond.

Lucrecia Dalt channels sensory echoes of growing up in Colombia on her new album ¡Ay!, where the sound and syncopation of tropical music encounter adventurous impulse, lush instrumentation, and metaphysical sci-fi meditations in an exclamation of liminal delight. In sound and spirit, ¡Ay! is a heliacal exploration of native place and environmental tuning, where Dalt reverses the spell of temporal containment. Through the spiraling tendencies of time and topography, Lucrecia has arrived where she began.

Alongside Moor Mother’s 2021 album, *Black Encyclopedia of the Air*, *Jazz Codes* explores the question of how accessible a generally inaccessible artist can get without sacrificing the density of their ideas. It isn’t to say it’s easy music (45 tightly collaged minutes of spoken word, free jazz, electronic loops, and fragmentary hip-hop)—only that it makes space for the listener in ways she hasn’t always in the past. Given the album’s subject matter—jazz history, the nature and place of Black art—it’s easy to hear the shift as one from personal expression to stewardship and communication: She wants you to understand where she’s coming from as a gesture of respect to those who came before, whether Woody Shaw (“WOODY SHAW”), Mary Lou Williams (“ODE TO MARY”), or Joe McPhee (“JOE MCPHEE NATION TIME”). Her fellow travelers—multi-hyphenate Black artists like AKAI SOLO and Melanie Charles—show you she isn’t alone. And while the difficulty lingers, it gets explicit purpose, courtesy of professor, artist, and activist Thomas Stanley on the outro: “Ultimately, perhaps, it is good that people abandoned jazz/Replaced it with musical products better-suited to capitalism’s designs/Now jazz jumps up like Lazarus if we allow it, to rediscover itself as a living music.”

Called “the poet laureate of the apocalypse” by Pitchfork, Moor Mother is announcing ‘Jazz Codes'. Coming out on July 1, it is her second album for ANTI- and a companion to her celebrated 2021 release ’Black Encyclopedia of the Air‘. ’Jazz Codes’ uses poetry as a starting point, but the collection moves toward more melody, more singing voices, more choruses and more complexity. In its warm, densely layered course through jazz, blues, soul, hip-hop, ’Jazz Codes’ sets the ear blissfully adrift and unhitches the mind from habit. Through her work, Ayewa illuminates the principles of her interdisciplinary collaborative practice Black Quantum Futurism, a theoretical framework for creating counter-chronologies and envisioning Black quantum womanist futures that rupture exclusionary versions of history and future through art, writing, music, and performance. Moor Mother - aka the songwriter, composer, vocalist, poet, and visual artist Camae Ayewa – is also a professor at the University of Southern California's Thornton School of Music. She released her debut album Fetish Bones in 2016 and has since put out an abundance of acclaimed music, both as a solo artist and in collaboration with other musicians who share her drive to dig up the untold. She is a member of many other groups including the free jazz group Irreversible Entanglements, 700 bliss and moor jewelry. She has also toured and recorded with The Art Ensemble of Chicago and Nicole Mitchell.

Order the LP at Forced Exposure : bit.ly/3nApTYE In a trajectory full of about-faces, Music for Four Guitars splices the formal innovations of Bill Orcutt's software-based music into the lobe-frying, blown-out Fender hyperdrive of his most frenetic workouts with Corsano or Hoyos. And while the guitar tone here is resolutely treble-kicked — or, as Orcutt puts it, "a bridge pickup rather than a neck pickup record" — it still wades the same melodic streams as his previous LPs (yet, as Heraclitus taught us, that stream is utterly different the second time around). Although it's a true left-field listen, Music for Four Guitars is bizarrely meditative, a Bill Orcutt Buddha Machine, a glimpse of the world of icy beauty haunting the latitudes high above the Delta (down where the climate suits your clothes). I've written before of the immediate misapprehension that greeted Harry Pussy on their first tour with my band Charalambides — that this was a trio of crazed freaks spontaneously spewing sound from wherever their fingers or drumsticks happened to land — but I'll grant the casual listener a certain amount of confusion based on the early recorded evidence (and the fact that the band COULD be a trio of crazed freaks letting fly, as we learned from later tours). But to my ears, the precision and composition of their tracks were immediately apparent, as if the band was some sort of 5-D music box with its handle cranked into oblivion by a calculating organ grinder, running through musical maps as pre-ordained as the road to a Calvinist's grave. That organ grinder, it turns out, was Bill Orcutt, whose solo guitar output until 2022 has tilted decidedly towards improvisation, while his fetish for relentless, gridlike composition has animated his electronic music (c.f. Live in LA, A Mechanical Joey). Music for Four Guitars, apparently percolating since 2015 as a loosely-conceived score for an actual meatspace guitar quartet, is the culmination of years ruminating on classical music, Magic Band miniatures, and (perhaps) The League of Crafty Guitarists, although when the Reich-isms got tossed in the brew is anyone's guess. And Reichian (Steve, not Wilhelm) it is. The album's form is startlingly minimalist — four guitars, each consigned to a chattering melody in counterpoint, repeated in cells throughout the course of the track, selectively pulled in and out of the mix to build fugue-like drama over the course of 11 brief tracks. It's tempting to compare them to chamber music, but these pieces reflect little of the delicacy of Satie's Gymnopedies or Bach's Cantatas. Instead, they bulldoze their way through melodic content with a touch of the motorik romanticism of New Order or Bailter Space ("At a Distance"), but more often ("A Different View," "On the Horizon") with the gonad-crushing drive of Discipline-era Crimson, full of squared corners, coldly angled like Beefheart-via-Beat-Detective. Just to nail down the classical fetishism, the album features a download of an 80-page PDF score transcribed by guitarist Shane Parish. And while it'd be just as reproducible as a bit of code or a player piano roll, I can easily close my eyes and imagine folks with brows higher than mine squeezing into their difficult-listening-hour folding chairs at Issue Project Room to soak up these sounds being played by real people reading a printed score 50 years from now. And as much as I want to bomb anyone's academy, that feels like a warm fuzzy future to sink into. . — TOM CARTER

Extended guitar hero Oren Ambarchi returns with Shebang, the latest in the series of intricately detailed long-form rhythmic workouts that includes Quixotism (2014) and Hubris (2016). Like those records, Shebang features an international all-star cast of musical luminaries, their contributions recorded individually in locations from Sweden to Japan yet threaded together so convincingly (by Ambarchi in collaboration with Konrad Sprenger) that it’s hard to believe they weren’t breathing the same studio air. Expanding on the techniques used on Simian Angel (2019), we can never be entirely sure who is responsible for what we hear, as Ambarchi’s guitar is used to trigger everything from bass lines to driving piano riffs. Picking up from the staccato guitar patterns that ran through Hubris, Shebang’s single 35-minute track begins with a precisely interwoven lattice of chiming guitar figures, expanding Hubris’ monolithic pulse into a joyous, hyper-rhythmic melodicism that calls up points of reference as disparate as Albert Marcoeur, early Pat Metheny Group, and Henry Kaiser’s It’s A Wonderful Life. Building from isolated single notes into densely layered polyrhythms, the muted guitar tones are joined by subtle touches of shimmering Leslie cabinet tones and guitar synth. Simmering down and funnelling into a single note, the guitar stew is soon thickened by Joe Talia’s propulsive ride cymbal, which blossoms into a beautifully flowing yet rigorously snapped-to fusion funk, whose ever-shifting details skitter across the kit – think 70s heavyweights like Jack DeJohnette or Jon Christensen. An unexpected entry of guttural bass clarinet licks from Sam Dunscombe begins the series of instrumental features that pepper the remainder of the piece. Soon we hear from the legendary British pedal steel player B.J. Cole (hopefully known to some listeners from his outer-limits singer-songwriter masterpiece The New Hovering Dog or, failing that, ‘Tiny Dancer’), whose languorous yet uneasy lines float in and out of a shifting rhythmic foundation supported by a single note bass groove, cut through with aleatoric synth articulations Though single-mindedly occupying its rhythmic space throughout, Shebang’s dense ensemble sound is carefully composed while drawing on the free flow of improvisation, with individual voices momentarily coming to the fore and subtle changes in harmony and texture. Perhaps the most surprising of these shifts occurs around half-way through when the smoke of a buzzing synth crescendo from Jim O'Rourke clears to reveal something like a piano trio, with Ambarchi’s guitar-triggered piano patterns providing restless accompaniment to flowing melodic lines from Chris Abrahams of The Necks, while Johan Berthling’s double bass and Talia’s drums fill out the bottom end. Before long, things take another left turn as Julia Reidy’s rapidly picked 12-string guitar lines take centre stage, with O’Rourke’s monumental synth clouds hovering in the distance. The ensemble surges through a slow series of harmonic changes before the whole shebang dissolves into a delirious synthetic mirage. Bridging minimalism, contemporary electronics, and classic ECM stylings, and bringing together a cast of preternaturally talented contributors, Shebang is unmistakably the work of Oren Ambarchi: obsessively detailed, relentlessly rhythmic, unabashedly celebratory.

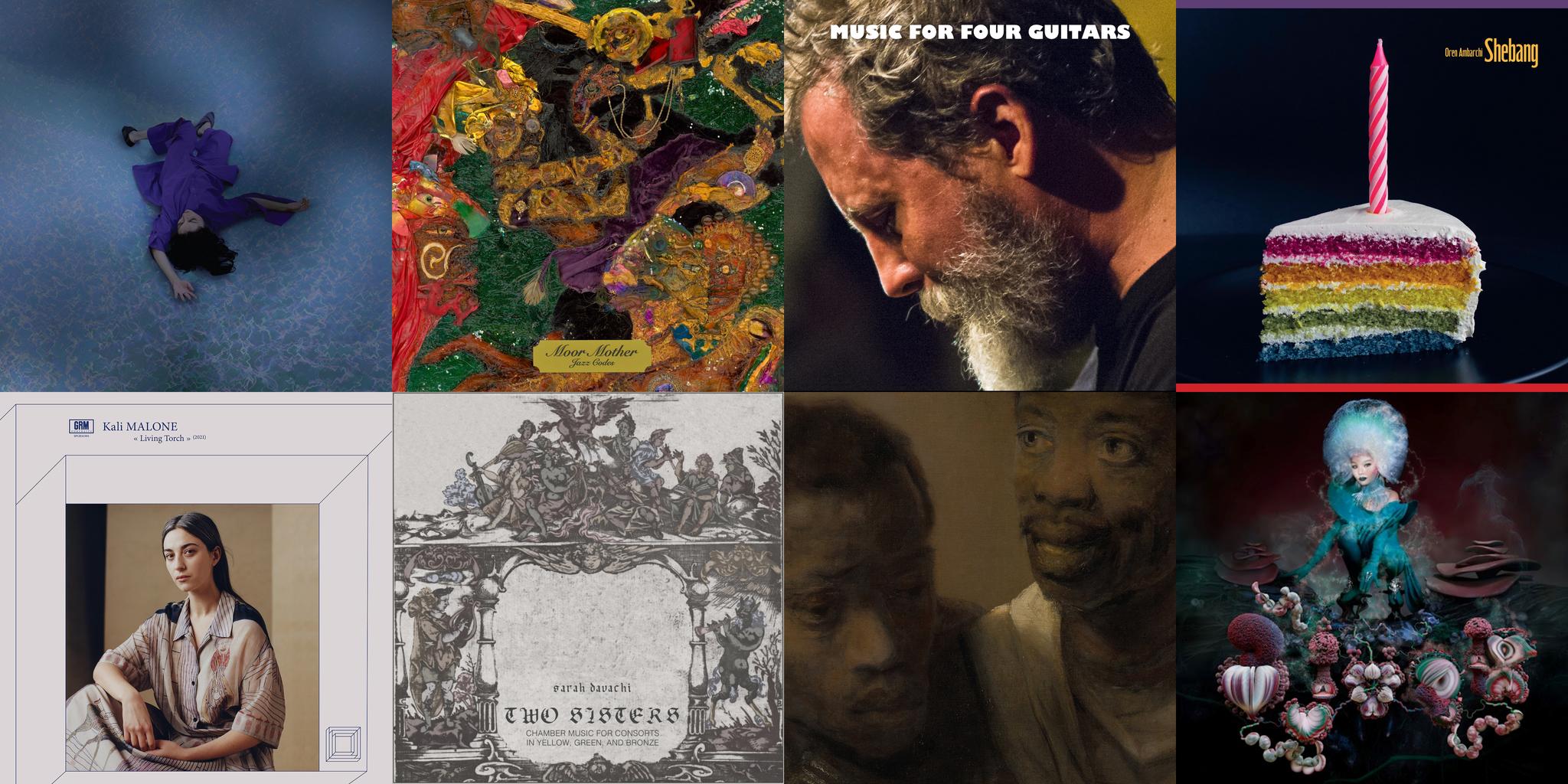

Stockholm-based Kali Malone is best-known for music that combines the rigor of electro-acoustic composition with the ruminative atmosphere of drone, doom metal, and medieval music—associations, no doubt, reinforced by her work with the pipe organ, which tends to put people in more primitive states of mind. As with a lot of her work (not to mention that of minimalist forebears like Eliane Radigue and La Monte Young), the process behind *Living Torch* is complex—pre-modern intonation, contemporary adaptations of Indian drone boxes. But the result is naturalistic and easy to listen to, conjuring dark hills, smoke-filled voids, and a pervasive sense of gloom that, while not threatening, point to forces and feelings modern life doesn’t tend to make time for. Listen loud and/or alone.

Living Torch, through its unique structural form and harmonic material, is a bold continuation of Kali Malone’s demanding and exciting body of work, while opening new perspectives and increasing the emotional potential of the music tenfold. As such, Living Torch is a major new piece by the composer and adds a significant milestone to an already fascinating repertoire. Departing from the pipe organ that Malone’s music is most notable for, Living Torch features a complex electroacoustic ensemble. Leafing through recordings from conventional instruments like the trombone and bass clarinet to more experimental machines like the boîte à bourdon, passing through sinewave generators and Éliane Radigue’s ARP 2500 synthesizer. Living Torch weaves its own history, its own genealogy, and that of its author. It extends her robust structural approach to a liberated palette of timbre. Living Torch was initially commissioned by GRM for its legendary loudspeaker orchestra, the Acousmonium, and premiered in its complete multichannel form at the Grand Auditorium of Radio France in a concert entirely dedicated to the artist. Composed at GRM studios in Paris between 2020-2021, Living Torch is a work of great intensity, an oeuvre-monde that is singularly placed at the crossroads of instrumental writing and electroacoustic composition. Living Torch proceeds from multiple lineages, including early modern music, American minimalism, and musique concrète. It’s a work as much turned towards exploring justly tuned harmony and canonic structures as towards the polyphony of unique timbres, the scaling of dynamic range, and the revelation of sound qualities. GRM (Groupe de Recherches Musicales), the pioneering institution of electroacoustic, acousmatic, and musique concrète, has been a unique laboratory for sonorous research since 1958. Witnessing the extreme vitality of the music championed by GRM, the Portraits GRM record series extends and expands this momentum with Kali Malone’s Living Torch. The French label-partner Shelter Press is proud to continue the collaboration with GRM, which Peter Rehberg of Editions MEGO set the foundation for in 2012.

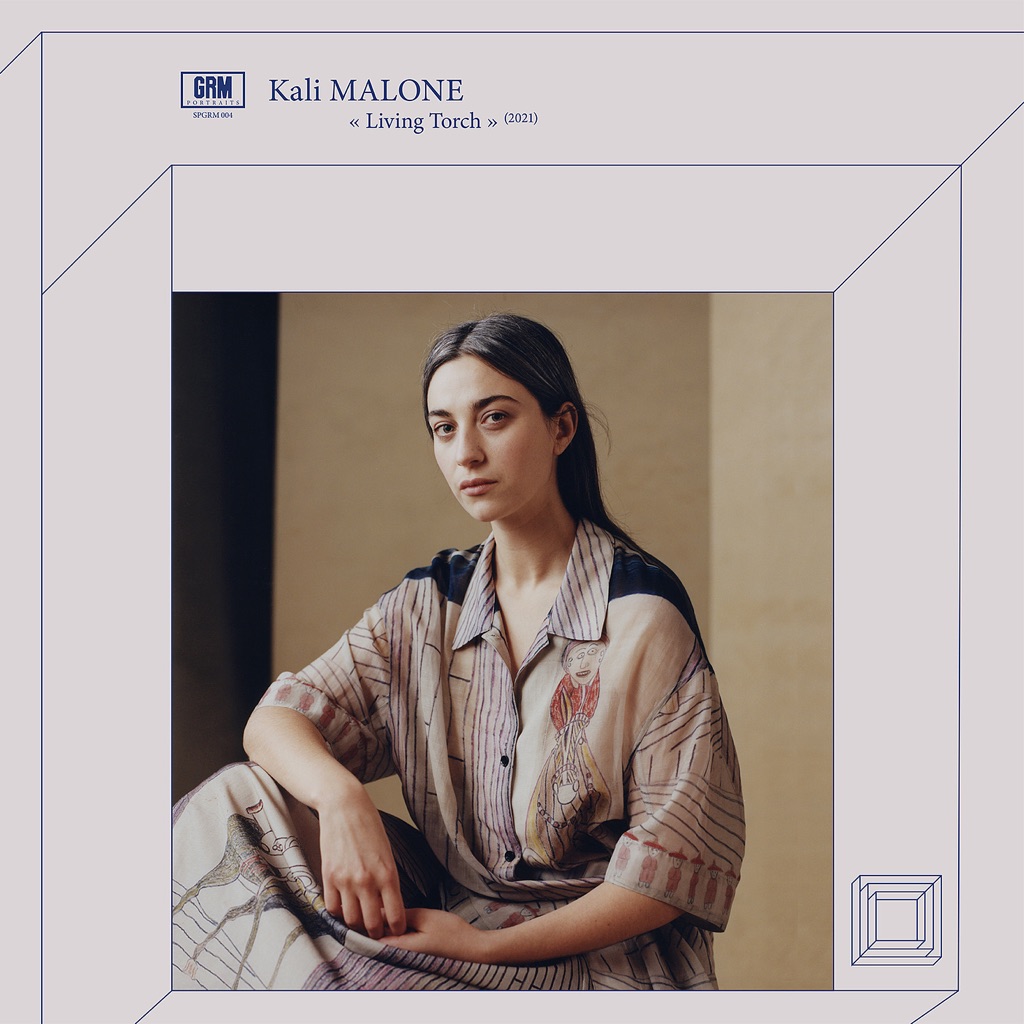

Releases September 2022 All compositions by Sarah Davachi 'Alas, Departing' based on 'Alas Departynge is Ground of Woo' (Anon., ca 1450) Recorded between January and November 2021 carillon on 'Hall of Mirrors' performed and recorded by Tiffany Ng mezzo-soprano on 'Alas, Departing' performed and recorded by Jessika Kenney contralto on 'Alas, Departing' performed and recorded by Dorothy Berry violin on 'Icon Studies I' performed and recorded by Johnny Chang viola on 'Icon Studies I' performed and recorded by Andrew McIntosh cello on 'Icon Studies I' performed and recorded by Judith Hamann quartertone bass flute and alto Renaissance recorder on 'Icon Studies I' performed by Rebecca Lane, recorded by Sam Dunscombe violins on 'Icon Studies II' performed by Mira Benjamin and Gordon MacKay, recorded by Simon Limbrick viola on 'Icon Studies II' performed by Bridget Carey, recorded by Simon Limbrick cello on 'Icon Studies II' performed by Anton Lukoszevieze, recorded by Simon Limbrick trombone on 'En Bas Tu Vois' performed by Mattie Barbier, recorded by Sarah Davachi quartertone bass flute on 'O World and the Clear Song' performed by Rebecca Lane, recorded by Sam Dunscombe electric organ (on 'Hall of Mirrors), reed organ (on 'Icon Studies I'), pipe organs (on 'Vanity of Ages', 'Harmonies in Bronze', 'Harmonies in Green', and 'O World and the Clear Song'), synthesizer (on 'Icon Studies I'), and bell plates (on 'O World and the Clear Song') performed and recorded by Sarah Davachi Mixed by Sarah Davachi at Alms Vert in Los Angeles, CA, USA Mastered by Sean McCann

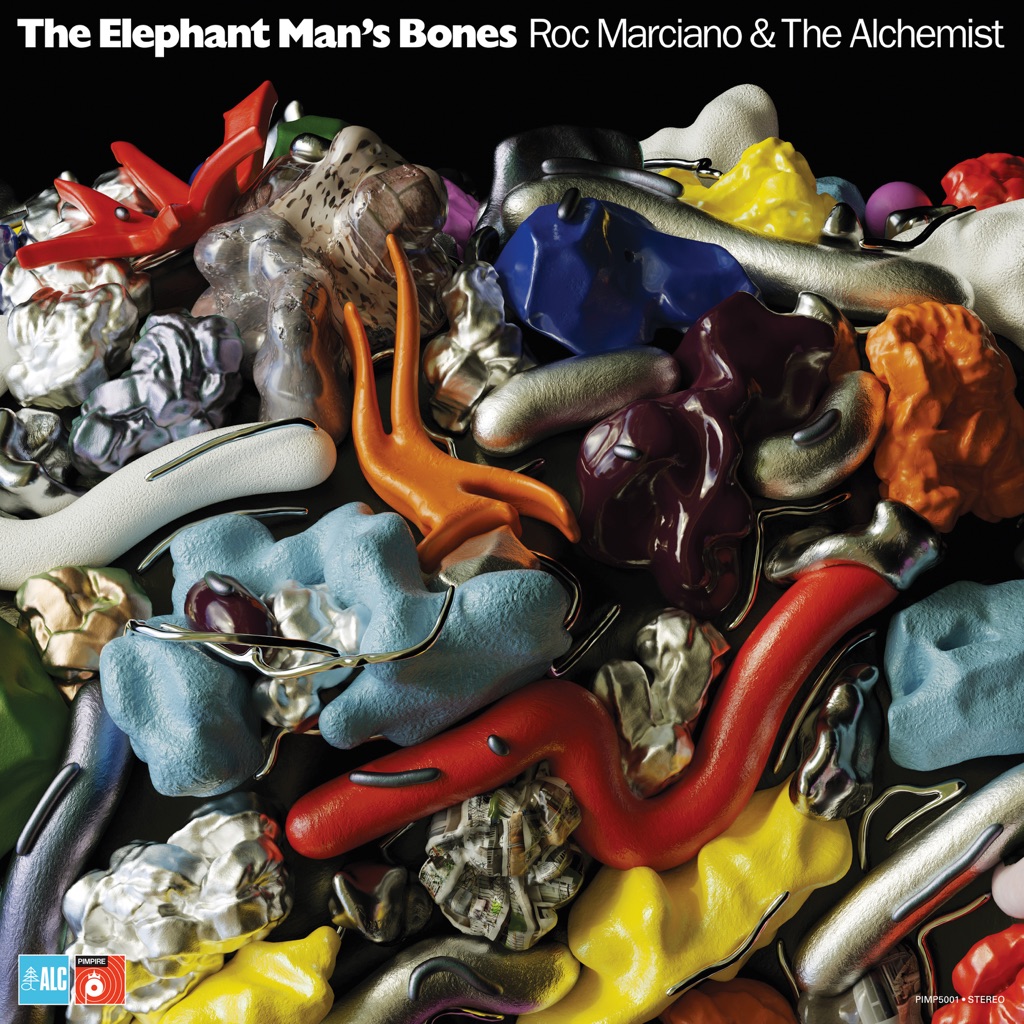

The New Yorker has finally gotten his flowers as one of the finest MCs in the contemporary underground after a cool couple decades grinding it out with his label, Backwoodz Studioz; 2021’s *Haram*, from Woods’ Armand Hammer duo with E L U C I D, felt like a high watermark for a new NY scene. On *Aethiopes*, Woods’ first solo album since 2019, he recruits producer Preservation, a fellow NY scene veteran known for his work with Yasiin Bey and Ka; his haunted beats set an unsettling scene for Woods’ evocative stories, which span childhood bedrooms and Egyptian deserts. The guest list doubles as a who’s who of underground rap—EL-P, Boldy James, E L U C I D—but Woods holds his own at the center of it all. As he spits on the stunningly skeletal “Remorseless”: “Anything you want on this cursed earth/Probably better off getting it yourself, see what it’s worth.”

DIGITAL VERSION OF THE ALBUM DROPS ON APRIL 8, 2022. Aethiopes is billy woods’ first album since 2019’s double feature of Hiding Places and Terror Management. The project is fully produced by Preservation (Dr Yen Lo, Yasiin Bey), who delivered a suite of tracks on Terror Management, including the riveting single “Blood Thinner”. The two collaborated again on Preservation’s 2020’s LP Eastern Medicine, Western Illness, which featured a memorable billy woods appearance on the song “Lemon Rinds”, as well as the B-side “Snow Globe”.

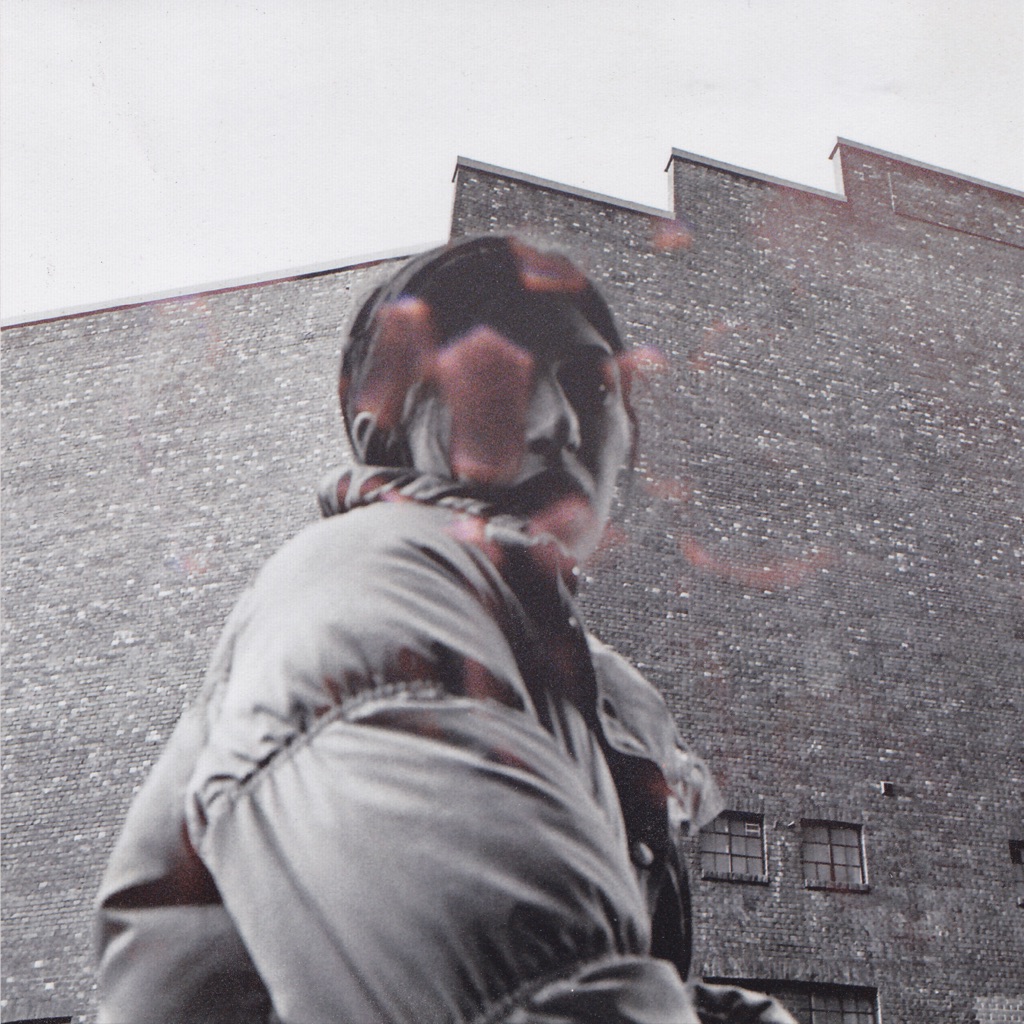

*Read a personal, detailed guide to Björk’s 10th LP—written by Björk herself.* *Fossora* is an album I recorded in Iceland. I was unusually here for a long time during the pandemic and really enjoyed it, probably the longest I’d been here since I was 16. I really enjoyed shooting down roots and really getting closer with friends and family and loved ones, forming some close connections with my closest network of people. I guess it was in some ways a reaction to the album before, *Utopia*, which I called a “sci-fi island in the clouds” album—basically because it was sort of out of air with all the flutes and sort of fantasy-themed subject matters. It was very much also about the ideal and what you would like your world to be, whereas *Fossora* is sort of what it is, so it’s more like landing into reality, the day-to-day, and therefore a lot of grounding and earth connection. And that’s why I ended up calling *Fossora* “the mushroom album.” It is in a way a visual shortcut to that, it’s all six bass clarinets and a lot of deep sort of murky, bottom-end sound world, and this is the shortcut I used with my engineers, mixing engineers and musicians to describe that—not sitting in the clouds but it’s a nest on the ground. “Fossora” is a word that I made up from Latin, the female of *fossor*, which basically means the digger, the one who digs into the ground. The word fossil comes from this, and it’s kind of again, you know, just to exaggerate this feeling of digging oneself into the ground, both in the cozy way with friends and loved ones, but also saying goodbye to ancestors and funerals and that kind of sort of digging. It is both happy digging and also the sort of morbid, severe digging that unfortunately all of us have to do to say goodbye to parents in our lifetimes. **“Atopos” (feat. Kasimyn)** “Atopos” is the first single because it is almost like the passport or the ID card (of the album), it has six bass clarinets and a very fast gabba beat. I spent a lot of time on the clarinet arrangements, and I really wanted this kind of feeling of being inside the soil—very busy, happy, a lot of mushrooms growing really fast like a mycelium orchestra. **“Sorrowful Soil” and “Ancestress” (feat. Sindri Eldon)** Two songs about my mother. “Sorrowful Soil” was written just before she passed away, it\'s probably capturing more the sadness when you discover that maybe the last chapter of someone\'s life has started. I wanted to capture this emotion with what I think is the best choir in Iceland, The Hamrahlid Choir. I arranged for nine voices, which is a lot—usually choirs are four voices like soprano, alto, or bass. It took them like a whole summer to rehearse this, so I\'m really proud of this achievement to capture this beautiful recording. “Ancestress” deals with after my mother passing away, and it\'s more about the celebration of her life or like a funeral song. It is in chronological order, the verses sort of start with my childhood and sort of follow through her life until the end of it, and it\'s kind of me learning how to say goodbye to her. **“Fungal City” (feat. serpentwithfeet)** When I was arranging for the six bass clarinets I wanted to capture on the album all different flavors. “Atopos” is the most kind of aggressive fast, “Victimhood” is where it’s most melancholic and sort of Nordic jazz, I guess. And then “Fungal City” is maybe where it\'s most sort of happy and celebrational. I even decided to also record a string orchestra to back up with this kind of happy celebration and feeling and then ended up asking serpentwithfeet to sing with me the vocals on this song. It is sort of about the capacity to love and this, again, meditation on our capacity to love. **“Mycelia”** “Mycelia” is a good example of how I started writing music for this album. I would sample my own voice making several sounds, several octaves. I really wanted to break out of the normal sort of chord structures that I get stuck in, and this was like the first song, like a celebration, to break out of that. I was sitting in the beautiful mountain area in Iceland overlooking a lake in the summer. It was a beautiful day and I think it captured this kind of high energy, high optimism you get in Iceland’s highlands. **“Ovule”** “Ovule” is almost like the feminine twin to “Atopos.” Lyrically it\'s sort of about being ready for love and removing all luggage and becoming really fresh—almost like a philosophical anthem to collect all your brain cells and heart cells and soul cells in one point and really like a meditation about love. It imagines three glass eggs, one with ideal love, one with the shadows of love, and one with day-to-day mundane love, and this song is sort of about these three worlds finding equilibrium between these three glass eggs, getting them to coexist.

Carl Stone continues his late career prolific renaissance with a new album of sculpted, tuneful MAX/MSP fantasias. Stone “plays” his source material the way Terry Riley’s In C “plays” an ensemble – with a loose, freewheeling charm connected to the ancient human impulse to make sound, melody, and rhythm from anything. Stone’s unique technique simultaneously focuses and sprays sound like a symphony of uncapped fire hydrants. Is this techno, avant-garde, sound art? It’s simply (or rather fantastically messily) Carl Stone.

On “Tick Tock,” the second track on *Warm Chris*, Aldous Harding asks, “Now that you see me, what you gonna do? Wanted to see me.” The New Zealand singer-songwriter’s lyrics have always been veiled and poetically cryptic—and she’s made a point of not explaining the meaning behind any of it. But her fourth album feels assured and open in a way that makes you wonder whether the question is directed at an audience that\'s been wanting to learn more about this singular artist. There’s a lot to see here, and like a well-directed film, it benefits from multiple replays, with more nuances and hidden meanings uncovered on each listen. Across her four albums, you’ll notice a linear emotional evolution. Speaking to Apple Music in 2019 about her then-new album *Designer*, she said, “I felt freed up… I could feel a loosening of tension, a different way of expressing my thought processes.” The journey clearly continued. *Warm Chris* is as intimate and curious as ever, but it’s more grounded, more confident. If the tension was loosening on *Designer*, here, Harding has grown accustomed to the relaxed space and made herself at home. The album seems to deal primarily with connections and relationships. She reflects on a lost love during opener “Ennui” (“You’ve become my joy, you understand… Come back, come back and leave it in the right place”), hunts for faded excitement on “Fever” (“I still stare at you in the dark/Looking for that thrill in the nothing/You know my favorite place is the start”), comically complains on “Passion Babe” (“Well, you know I’m married, and I was bored out of my mind/Of all the ways to eat a cake, this one surely takes the knife… Passion must play, or passion won’t stay”), and accepts an ending on “Lawn” (“Then if you\'re not for me, guess I am not for you/I will enjoy the blue, I’m only confused with you”). On the whole, *Warm Chris* feels light and folksy, and the music is relatively simple—though not without its surprises. There are brass embellishments here, a psychedelic guitar solo there, even a brief foray into forlorn vintage blues on “Bubbles.” It leaves space for Harding’s voice to remain in the spotlight. Her vocal acrobatics are as strange and versatile as ever—she can shift from breathy, dramatically deep bass to ultra-fine, ultra-high falsetto in moments, sometimes for only a word at a time. She sounds innocent and paper-thin on the gentle “Lawn,” lively—and inflected with an unusual accent—on “Passion Babe.” Her delivery is so pronounced and hyperbolic on the heart-wrenching “She’ll Be Coming Round the Mountain” that it sounds like something out of a musical. And album closer “Leathery Whip” feels inspired by The Velvet Underground, complete with a deep Nico drawl (occasionally flipping to a Kate Bush-style nasal tone), backing harmonies, a jangling tambourine, and a cheeky refrain: “Here comes life with his leathery whip.”

An artist of rare calibre, Aldous Harding does more than sing; she conjures a singular intensity. The artist has announced details of Warm Chris new studio album, the follow-up to 2019’s acclaimed Designer. For Warm Chris, the Aotearoa New Zealand musician reunited with producer John Parish, continuing a professional partnership that began in 2017 and has forged pivotal bodies of work (2017’s Party and the aforementioned Designer). All ten tracks were recorded at Rockfield Studios in Wales, the album includes contributions from H. Hawkline, Seb Rochford, Gavin Fitzjohn, John and Hopey Parish and Jason Williamson (Sleaford Mods).

For more than two decades, the disciple that has most visibly carried on Sun Ra Arkestra’s legacy and sound is their musical director, alto saxophonist Marshall Allen, the iconic fire breather and life force that restored the Arkestra’s vitality in the massive vacuum left by Ra and John Gilmore’s death in the ‘90s. Allen turned 98 in 2022 and, as evidenced by Living Sky, his influence and leadership remain undiminished. Marking the Arkestra’s first new recording since their 2021 Grammy-nominated album Swirling, Living Sky was recorded on June 15, 2021 at Rittenhouse SoundWorks in Philadelphia and features a total of nineteen musicians, including a strings section. It was mixed and mastered by three-time Grammy winner Dave Darlington (Eddie Palmieri, Brian Lynch, Wayne Shorter). Living Sky includes the first instrumental recording of Ra’s “Somebody Else’s Idea,” originally recorded in 1955 and again in 1970 for proper release on 1971’s My Brother The Wind, Vol II. Without June Tyson’s fierce vocal presence, “Somebody Else’s Idea” feels more measured, allowing for the hovering harmonic movement to glide into the foreground with the horns modulating their volume and presence in each cycle and bringing in new details, whether it be the mewling trumpets of Michael Ray and Cecil Brooks or the seeking sound flurries blow by Allen on Electronic Valve Instrument. The Arkestra’s renewed brilliance is thanks in part to the singing of Tara Middleton, the true heir to Tyson, who plays violin and flute in the album. With Living Sky the Arkestra eschew the human voice, creating cosmic tones only with their instruments. The repertoire includes pieces of more recent vintage penned by Allen, complementing a variety of classic material that take on a decidedly more mellow hue in this context. The album opens with “Prelude in A Major,” Ra’s elaboration of the Frédéric Chopin miniature that previously appeared on only a few live recordings. Special Arkestra harmonies emanate from “Marshall’s Groove,” a spacey blues by Allen that ramps up patiently, like flames gingerly lapping at a sonic cauldron until an inferno engulfs the pot stoked by the swinging groove of drummer Wayne Anthony Smith Jr. Allen temporarily sets aside his alto in favor of the kora on his “Day of the Living Sky,” where his chiming chords open up like a sunrise welcoming the gurgle of hand percussion, meandering flute, and muted low brass crying in the far distance. The album concludes with a pair of tuneful ballads that inject an uncertain optimism and beauty into the proceedings. Allen’s gorgeous “Firefly” provides the saxophonist with a lush platform for an extended solo toggling between pleading cries and ecstatic hollers while clearing improvisational space for Scott, veteran French horn maestro Vincent Chancey, trombonist Adriene G Davis, tenor saxophonist Nasir P. Dickenson, and a three-way string conversation between Middleton, Gwen Laster, and Melanie Dyer. The album’s hopeful vibe embraces a leap of faith with a new spin on “When You Wish Upon a Star,” a long-time feature in the Arkestra’s rep, where Allen offers a testimonial that’s anything but starry-eyed. For decades listeners have looked to Sun Ra’s Arkestra for outward bound possibilities in music that grapples with earthly mayhem by embracing other galaxies. Yet their music has always been grounded by the human spirit. In this first new recording since the pandemic bandleader Marshall Allen and company give us something we can hold onto, an instrumental album rich in spirituality guiding us through the unknown yet again.

Weather is happening. From the heart of Delhi, to Tangier Island. The burning redwood forests, the dying jet stream waters. It is happening to you and to me. We pump carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere by the gigaton as the cascading feedback loops of climate breakdown continue to destabilize the biosphere. Oh, the wind and rain. We have all lived it. Stunned by the unfathomable power of our Earth and a sinking derealization about our tenuous future. "Almanac Behind" exists in this space. The title is both an anagram of Daniel Bachman’s name and a reference to the fact that rapid environmental changes have rendered traditional weather forecasting methods woefully unable to accurately predict our future. Over fifteen tracks, "Almanac Behind" guides the listener through natural disaster and its aftermath, via a series of field recordings by Bachman and his collaborators. The guitar, banjo, fiddle, and other instruments are presented in neutral modal tunings, avoiding conventional harmonic representations of mood and sentiment, and are often digitally altered in both subtle and obvious ways. At its core, "Almanac Behind" is powered by the sounds of the Earth, tones inherently familiar to the billions of people who have experienced extreme weather. It is an attempt to emotionally contend with and foster connection over a shared global experience. “Barometric Cascade (Signal Collapse)” begins with wind blowing through front porch windchimes. Broken segments of cut-and-pasted slide guitar improvisations play over a tanpura-like guitar drone. The slide guitar crackles out of a thin radio speaker, achieved by broadcasting the recording to a home radio via an FM transmitter. As the storm gathers, the radio signal collapses into squelching tones. Local NOAA weather radio, “8:35 PM KHB36 (Alter Course)” cuts through the static and relays a year’s worth of emergency weather broadcasts recorded by Bachman at his home in Banco, Va. The chaotic thumps and strums of a 12-string guitar warn of the events unfolding. An emergency broadcast plays over church hymns. The signal morphs into “Bow Echo/Wall Cloud,” a series of repeating audio patterns made from traditional Appalachian rain signs rendered into WAV files. “Gust Front (The Waiting)” follows, with solo banjo playing an uneasy cadence as winds gather in tight mountain valleys. The storm begins almost instantly in “540 Supercell,” where a now-driving banjo and frogs, recorded in the mill race behind Bachman’s house, are easily overtaken by waves of hissing rain and hail. “10:17 PM KHB36 (The Warned Area)” returns with an updated emergency alert of imminent flooding in the neighborhood. Disparate radio transmissions swell as the broadcast is overtaken by the rising water. All that remains when “Flood Stage” opens is repeating AM radio static, slowed 43 times to create a pulsing rhythmic pattern that drives through the entirety of the track. The same cut-and-paste technique used earlier is repeated here to create a buoyant slide guitar melody, like a dead log floating down a swollen river. The flood waters rise during “Inundation (The Blackout),” in which the sounds of all of Virginia’s major rivers at flood stage flow into one sonic stream. Tree limbs, pulled into the water, scream in high pitched wails. Electrical lines flail wildly as all sound condenses into a single point, then silence. A match is lit in the darkness as “Wildfire (Smoke Over Old Rag)” begins. Here, Bachman has built a fire from field recordings, YouTube videos of Virginia wildfire responders, harmonium drone, and a beat created by rendering a photo of the sun setting behind Old Rag Mountain, red from West coast wildfire smoke, into a WAV file. “Think Before You Breathe” is audio of dying fire, significantly slowed to exaggerate its final gasps for air. The warbling guitar floats to great heights with the smoke, consistently interrupted by glitches and abrupt pitch drops. “3:24 AM KHB36 (When The World’s On Fire)” breaks out of the relative calm with the drone of hand-wound emergency radio crank underneath clips from the 2022 IPCC report, time signal radio broadcast, a smoke inhalation alert, and a performance of the Carter Family’s gospel tune “When The World’s On Fire” on slide guitar and accompaniment. The tired and mournful banjo solo, “Daybreak (In The Awful Silence)” represents exhaustion and frustrated resignation during an extended power outage. “Grid Reactivation” comes suddenly, rushing down the lines to reach the transformer, powering on the A/C, radio, and other temporarily-muted appliances. “Five Old Messages (MadCo Alert)” await. Now, as cleanup begins, comes “Recalibration/Normalization.” The cut-and-paste technique is repeated one final time to represent disorientation of facing a new reality in the aftermath of disaster. At its end, we again hear wind rustling the porch chimes, signaling storms on the horizon. "Almanac Behind" ends as it began, and can be played on a loop, mirroring the cyclicality of these weather patterns. The only thing that has changed is that the listener has now also experienced them. Weather is happening.

Listening to the Baltimore instrumental band Horse Lords’ mix of minimal art-rock and pan-African music is like looking at one of those optical illusions where you can’t tell if an image is static or moving, and if so, how fast. It can sound jarring and dissonant and almost purposefully ugly (“May Brigade”) but so trancelike in its repetitions that even its dissonances become beautiful (“Law of Movement”). And like Talking Heads or ’90s math-rock bands like Don Caballero, their kinship with punk isn’t just their intensity but their rebellion against the fantasy of rock music being something loose and free. They occasionally flirt with machines (the outro of “Mess Mend”), but their discipline is 100 percent human.

Horse Lords return with Comradely Objects, an alloy of erudite influences and approaches given frenetic gravity in pursuit of a united musical and political vision. The band’s fifth album doesn’t document a new utopia, so much as limn a thrilling portrait of revolution underway. Comradely Objects adheres to the essential instrumental sound documented on the previous four albums and four mixtapes by the quartet of Andrew Bernstein (saxophone, percussion, electronics), Max Eilbacher (bass, electronics), Owen Gardner (guitar, electronics), and Sam Haberman (drums). But the album refocuses that sound, pulling the disparate strands of the band’s restless musical purview tightly around propulsive, rhythmic grids. Comradely Objects ripples, drones, chugs, and soars with a new abandon and steely control.

Listeners get a sense of Mary Halvorson’s writing for The Mivos Quartet on the latter three tracks of *Amaryllis*. But on *Belladonna*, the companion album from the same year, the pairing of the Mivos strings and Halvorson’s guitar becomes the sole focus. While the horns and rhythm section of *Amaryllis* make for a busier, more groove-oriented sound, the sparser texture of *Belladonna* renders it more guitar-centric. In a sense, The Mivos Quartet becomes a string quintet, though Halvorson’s instrument is plucked rather than bowed, and she makes liberal use of pitch-shifting and bending effects to tweak her otherwise clean and unadorned hollow-body sound. (Four minutes into “Flying Song” is a particularly stark example.) The writing is sonically rich, dense with counterpoint and astringent lyricism, with a porous boundary between composed and improvised elements. In the closing minutes of the title track, Halvorson takes an aggressive turn, multitracking distorted lines over a metal-like cello riff. For a moment, the aesthetics of shred crash the chamber-music party, right before the whole affair comes abruptly to an end.

-Mondays at The Enfield Tennis Academy-, x2 LPs of long-form, lyrical, groove-based free improv by acclaimed guitarist & composer Jeff Parker's ETA IVtet is at last here. Recorded live at ETA (referencing David Foster Wallace), a bar in LA’s Highland Park neighborhood with just enough space in the back for Parker, drummer Jay Bellerose, bassist Anna Butterss, & alto saxophonist Josh Johnson to convene in extraordinarily depthful & exploratory music making. Gleaned for the stoniest side-length cuts from 10+ hours of vivid two-track recordings made between 2019 & 2021 by Bryce Gonzales, -Mondays at The Enfield Tennis Academy- is a darkly glowing séance of an album, brimming over with the hypnotic, the melodic, & patience & grace in its own beautiful strangeness. Room-tone, electric fields, environment, ceiling echo, live recording, Mondays, Los Angeles. Jeff Parker's first double album & first live album, -Mondays at The Enfield Tennis Academy- belongs in the lineage of such canonical live double albums recorded on the West Coast as Lee Morgan’s -Live at the Lighthouse-, Miles Davis' -In Person Friday & Saturday Night at the Blackhawk, San Francisco- & -Black Beauty-, & John Coltrane's -Live in Seattle-. While the IVtet sometimes plays standards &, including on this recording, original compositions, it is as previously stated largely a free improv group —just not in the genre meaning of the term. The music is more free composition than free improvisation, more blending than discordant. It’s tensile, yet spacious & relaxed. Clearly all four musicians have spent significant time in the planetary system known as jazz, but relationships to other musics, across many scenes & eras —dub & Dilla, primary source psychedelia, ambient & drone— suffuse the proceedings. listening to playbacks Parker remarked, humorously & not, “we sound like the Byrds” (to certain ears, the Clarence White-era Byrds, who really stretched it). A fundamental of all great ensembles, whether basketball teams or bands, is the ability of each member to move fluidly & fluently in & out of lead & supportive roles. Building on the communicative pathways they’ve established in Parker’s -The New Breed- project, Parker & Johnson maintain a constant dialogue of lead & support. Their sampled & looped phrases move continuously thru the music, layered & alive, adding depth & texture & pattern, evoking birds in formation, sea creatures drifting below the photic zone. Or, the two musicians simulate those processes by entwining their terse, clear-lined playing in real-time. The stop/start flow of Bellerose, too, simulates the sampler, recalling drum parts in Parker’s beat-driven projects. Mostly Bellerose's animated phraseologies deliver the inimitable instantaneous feel of live creative drumming. The range of tonal colors he conjures from his extremely vintage battery of drums & shakers —as distinctive a sonic signature as we have in contemporary acoustic drumming— bring almost folkloric qualities to the aesthetic currency of the IVtet's language. A wonderful revelation in this band is the playing of Anna Butterss. The strength, judiciousness & humility with which she navigates the bass position both ground & lift upward the egalitarian group sound. As the IVtet's grooves flow & clip, loop & repeat, the ensemble elements reconfigure, a terrarium of musical cultivation growing under controlled variables, a tight experiment of harmony & intuition, deep focus & freedom. For all its varied sonic personality, -Mondays at The Enfield Tennis Academy- scans immediately & unmistakably as music coming from Jeff Parker‘s unique sound world. Generous in spirit, trenchant & disciplined in execution, Parker’s music has an earned respect for itself & for its place in history that transmutes through the musical event into the listener. Many moods & shapes of heart & mind will find utility & hope in a music that combines the autonomy & the community we collectively long to see take hold in our world, in substance & in staying power. On the personal tip, this was always my favorite gig to hit, a lifeline of the eremite records Santa Barbara years. Mondays southbound on the 101, driving away from tasks & screens & illness, an hour later ordering a double tequila neat at the bar with the band three feet away, knowing i was in good hands, knowing it would be back around on another Monday. To encounter life at scales beyond the human body is the collective dance of music & the beholding of its beauty, together. —Michael Ehlers & Zac Brenner Pressed on premium audiophile-quality 120 gram vinyl at RTI from Kevin Gray / Cohearent Audio lacquers. Mastered by Joe Lizzi, Triple Point Records, Queens, NY. First eremite edition of 1799 copies. First 400 direct order LPs come with eremite’s signature retro-audiophile inner-sleeves, hand screen-printed by Alan Sherry, Siwa Studios, northern New Mexico. CD edition & EU x2LP edition available thru our EU partner, Aguirre records, Belgium. Jeff Parker synthesizes jazz and hip-hop with an appealingly light touch. The longtime Tortoise guitarist has a silken, clean-cut tone, yet his production takes more cues from DJ Premier than it does from a classic mid-century jazz sound. In the early ’00s, when Madlib ushered a boom-bap sensibility into the hallowed halls of the jazz label Blue Note, Parker conducted his own experiments in genre-mashing in the Chicago group Isotope 217, dragging jaunty hip-hop rhythms into the far reaches of computerized abstraction. More recently, Parker enlivened quantized beats and chopped-up samples with live instrumentation, both as leader of the New Breed and sideman to Makaya McCraven. Inverting rap’s longtime reverence for jazz, Parker has gradually codified a new language for the so-called “American art form” with a vocabulary gleaned from the United States’ next great contribution to the musical universe. Parker’s latest, the live double LP Mondays at the Enfield Tennis Academy, was largely recorded in 2019, while his star as a solo artist was steeply ascending. Capturing a few intimate evenings with drummer Jay Bellerose, bassist Anna Butterss, and New Breed saxophonist Josh Johnson at ETA, a cozy Los Angeles cocktail bar, the record anticipates his 2020 opus with the New Breed, Suite for Max Brown. Yet Mondays amounts to something novel in 2022: It lays out long-form spiritual jazz, knotty melodies, and effortless solos over a slow-moving foundation as consistent as an 808. The results are as mesmerizing as a luxurious, beatific ambient record—yet at the same time, it’s clear that all of this is happening within the inherently messy confines of an improvisatory concert. Across four side-long tracks, each spanning about 20 minutes, Parker and Johnson trade ostinatos, mesh together, split again into polyrhythmic call-and-response. Butterss commands the pocket with a photonegative of their lead lines, often freed from rhythmic responsibilities by the drums’ relentlessness. Bellerose exhibits a Neu!-like sense of consistency, just screwed down a whole bunch of BPMs. His kit sounds as dusty as an old sample, and his hypnotic rhythms evoke humanizers of the drum machine such as J Dilla or RZA. You could spend the album’s 84-minute runtime listening only to the beats; every shift in pattern queues a new movement in the compositions, beaming a timeframe from the bottom up. Bellerose’s sensitive, reactive playing, though, is unmistakably live. We can practically see the sweat beading on his arm when he holds steady on a ride cymbal for minutes on end, or plays a shaker for a whole LP side. He begins the understated opener “2019-07-08 I” with feather-soft brush swirls, but on the second cut, he sets Mondays’ stride, as a simple bell pattern builds into a leisurely rhythmic stroll. Thirteen minutes in, the mood breaks. Bellerose hits some heavy quarter notes on his hi-hat; Butterss leans into a fat bassline; saxophone arpeggios, probably looped, float in front of us like smoke rings lingering in the air. It’s a glorious moment, punctuated by clinking glasses and a distant “whoo!” so perfectly placed we become aware of not only the setting, but also the supple knob-turns of engineer Bryce Gonzales in post-production. Anyone who’s heard great improvisation at a bar in the company of both jazzheads and puzzled onlookers knows this dynamic—for some, the music was incidental. Others experienced a revelation. Lodged in this familiar situation is the question of what such “ambient jazz” means to accomplish—whether it wants to occupy the center of our consciousnesses, or resign itself to the background. The record’s perpetual soloing offers an answer. Never screechy, grating, or aggressive, each performance is nonetheless highly individual. Even when the quartet settles into an extended groove, a spotlight shines on Johnson, Butterss, and Parker in turn, steadily illuminating a perpetual sense of invention. Their interplay feels almost traditional, suggesting bandstand trade-offs of yore, yet the open-ended structure of their jams keeps it unconventional. Mondays works in layers: Its metronomic rhythms pacify, but the performers and their idiosyncratic expressions offer ample material to those interested in hearing young luminaries and seasoned vets swap ideas within a group. In 2020, Johnson dropped his first record under his own name, the excellent, daringly melodic Freedom Exercise, while Butterss’ recent debut as bandleader, Activities, is one of the most exciting, undersung jazz releases of 2022. Akin to Parker’s early experiments with Tortoise and Chicago Underground, Johnson and Butterss’ recordings both revel in electronic textures, and each features the other as a collaborator. Mondays captures them as their mature playing styles gain sea legs atop the rudder of Parker’s guitar. The only track recorded after the pandemic began, closer “2021-04-28” sculpts the record’s loping structure, giving retrospective shape to the preceding hour of ambience. In the middle of the song, Parker’s guitar slows to a yawn; the drums pipe down. After a couple minutes of drone, Bellerose slips back into the mix alongside a precisely phrased guitar line strummed on the upper frets, punctuated by saxophone accents that exclaim with the force of an eager hype man. Beginning with a murmur, the album ends with a bracing statement, a passage so articulated that it actually feels spoken. Mondays drifts with unhurried purpose through genres and ideas, imprinted with the passage of time. The deliberate, thumping clock of its drumbeat keeps duration in mind, and, as with so many live albums, we’re reminded of how circumstances have changed since the sessions were recorded. Truly, life is different than it was in 2019—and not just in terms of world politics, climate change, the threat of disease, or the reality that making a living in music is harder than ever. Seemingly catalyzed by COVID-19’s deadly, isolating scourge, jazz has transformed, hybridized, and weakened tired arguments for musical stratification and fundamentalism. Even calling Mondays a “live” album is a simplification, considering how Parker and other top jazz brains have increasingly availed themselves of the studio—including, in a sparing yet dramatic way, on Mondays. Near the end of the first track, the tape slows abruptly. The plane of the song opens to another dimension: This set, Parker seems to be saying, can be manipulated with the ease of a vinyl platter beneath a DJ’s fingers. Parker’s latest may be his first live album, but it’s also the product of a mad scientist, cackling over a mixing board. Time is dilated, curated, edited, and intercut, and the very live-ness of a concert recording turns fascinatingly, fruitfully convoluted—even when the artists responsible are four players participating in the age-old custom of jamming together in a room. --Daneil Felsenthal, Pitchfork, 8.4 Best New Music Turn to Mondays at The Enfield Tennis Academy and you’re in another world. Recorded live (it’s apparently Parker’s first live record) between 2019 and 2021 at a bar in Los Angeles’ Highland Park neighborhood that’s named for the principal setting of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest(and Parker’s ETA 4tet named, in turn, for the room). As producer Michael Ehlers points out in a press sheet, It is “largely a free improv group —just not in the genre meaning of the term.” Mondays… will include all the things that free improvisation leaves out, modes, melodies, key centres and regular (though often multiple) rhythms; in effect, the musicians are free to include the conventionally excluded. It’s a kind of perfect opposite of Eastside Romp – clear tunes rarely define a piece, there’s no solo order, actually few solos, no formal beginnings or endings – instead substituting the extended jam for the tight knit composition. It’s a two-LP set, each side an excerpt from a long collective improvisation, a kind of electronic jazz version of hypnotic minimalism with Parker and saxophonist Josh Johnson both employing loops to build up interlocking rhythmic patterns and a kind of floating, layered timelessness, while bassist Anna Butterss and drummer/ percussionist Jay Bellerose lay down pliable fundamentals. Often and delightfully, it answers this listener’s specific auditory needs, a bright shifting soundscape that can begin in mid-phrase and eventually fade away, not beginning, not ending, like Heaven’s Muzak or the abstract decorative art of the Alhambra. It can sound at times like, fifty years on, Grant Green has added his clear lines to the kind of work that over 50 years ago filtered from Terry Riley to musicians from jazz, rock and minimalism. Though the tunes are described as excerpts, we often have what seem to be beginnings, the faint sound of background conversation and noise ceding to the music in the first few seconds, but the “beginnings” sound tentative, like proposals or suggestions. The most explicit tune here is the slow, loping line passed back and forth between Parker and Johnson that initiates Side C, 2019 May-05-19, the earliest recording here. The music is a constant that doesn’t mind omitting its beginnings and ends, but it’s also, in the same way, an organism, a kind of music that many of us are always inside and that is always inside us. All kinds of music stimulate us in all kinds of ways, but for this listener, Jeff Parker’s ETA Quartet happily raises a fundamental question: what is comfort music, what are its components, and could there be a universal comfort music? Or is comfort music a universal element in what we may listen for in sound? Modality, rhythmic and melodic figures/motifs, drone, compound relationships and, too, a shifting mosaic that cannot be encapsulated? The thing is, any music we seek out is, in our seeking, a comfort, whether it’s a need for structures so complex that we might lose ourselves in mapping them, or music so random, we are freed of all specificity, but something that may have healing properties. This is not just bar music, but music for a bar named for art that further echoes in the band’s abbreviated name. Socialization is enshrined here. There’s another crucial fiction, too, maybe closer, The Scope, the bar in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 with its “strictly electronic music policy”. Consider, too, the social roots reverberating in the distant musical ancestry, that Riley session with John Cale, Church of Anthrax, among many … or the healing music of the Gnawa … or the Master Musicians of Jajouka with Ornette Coleman on Dancing in Your Head. And that which is most “natural” to us in the early decades of the 21st century? … Jamming, looping, drones…So perhaps an ideal musical state might be a regular Monday night session with guitar, saxophone, loops, bass and drums…the guitarist and saxophonist using loops, expanding the palette and multiplying the reach of time, repeating oneself with the possibility of mutation or constancy. In some long ago, perfect insight into a burgeoning age of filming and recording, Jay Gatsby remarked, “Can’t repeat the past? Why, of course you can!” We might even repeat the present or the future. --Stuart Broomer, freejazzblog.org

Composed in 2020 during the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, the first incarnation of the work was played as a sound installation at the Kapellen Leprosarium (Leper's Sanctuary) in Hanover, Germany. This sanctuary was built around 1250 and served as a quarantine for those who suffered from the plague and leprosy in the Middle Ages. This first presentation of Broken Gargoyles featured verses by German poet Georg Heym, “Das Fieberspital” and “Die Dämonen der Stadt.” The work was finalized in 2020 in collaboration with the artist and sound designer Daniel Neumann. In “Das Fieberspital” Heym describes the horrific state of people suffering from yellow fever who live in paralyzing fear of death and swirling delirium owing to their brutal treatment and isolation in medical wards in early 20th-century Germany. “Die Dämonen der Stadt” also addresses such grim portents of World War I; in this poem, the god Baal observes (like a gargoyle) a town from a rooftop of a city block at nighttime and lets a street burn down during dawn. Employing a vast array of advanced vocal and instrumental techniques, Broken Gargoyles is arguably Galas’ most intellectually, sonically and viscerally formidable work to date. The album finds the visionary artist deftly probing the weaving, warping transformation on the nervous systems of her post-traumatic soldiers and dying diseased. The album’s first part, “Mutilatus,” contains the Heym poems “Das Fieberspital” and “Die Dämonen der Stadt,” and concerns the suffering of the soldier in the trenches and during innumerable operations in the hospital. “Mutilatus,” was originally recorded in 2012-2013 in collaboration with recording and mix engineer Kris Townes and serves as a welcome into a parallel world of doom and delusion foretold. Sustained, portentous low-end piano rumble and Galás’ solo and multiplied voices create evanescent masses of tonality and, pertinently, a resonant frequency clash or harmonic distortion. You can hear it and feel it: she is inside her subjects, as if to emphasize with the sweaty diffusion of the patients’ feverish minds. When this extraordinary introduction of “Mutilatus” recedes in an approaching chilly ill wind, Galás intones over subdued whining electronics, cawing birds, semi-human verbalizations and something somewhere between these things. Representing the doomed, their punishers and perhaps her listeners in all our delusional wisdom, she rasps out words, or the sound of words; the electronic whine rises and falls. Then piano, left-hand low, and “vocalese” so high in deliberately splintery disfigurement, which gives way to the piano’s pulsing beat-figure darkly looming over the hill amid a babble of human voices and dark clouds of ravens. The often sisyphean sound throughout Broken Gargoyles plumbs great depths in the album’s second part, “Abiectio” (humiliation, dejection, despondency), which draws from the Heym poems “Der Blinde” and “Der Hunger” and the last verses of “Das Fieberspital.” Feedback moans over impending piano thunder, Galás rough-grain wheezes, bawls and howls. Multilayered voice becomes a flock of winged creatures. The effected vocal throngs reach out diseased limbs, mangled faces. Where humans become beasts become…A blind man is forced outside of an asylum to die, with the order "Look into the sun!" Galás makes the inference that the sun burns him alive. A man made delirious and dying through hunger and the sun (again) forces open the jaws of a hound in order to devour him and ends up falling into a dark crevice, where he disappears. The voice at the end of “Das Fieberspital” speaks as one with a burned throat might, through what sounds like an electrolarynx –– again a herald to fire, dehydration. This part of the poem observes the patients laughing in derision and delirium at the priest who approaches the bed of a man dying of yellow fever in order to give him the Last Rites. The dying man impales the priest with a stone he had been sharpening. The album’s title references Krieg dem Kriege!, a photographic book by the German anti-militarist Ernst Friedrich from 1924 documenting the atrocities of World War I, including the album’s nominal “broken gargoyles,” which is how the facially maimed soldiers were termed by their hospital keepers; the disfigured soldiers also had to wear metal masks to better hide their monster faces –– blown apart by shrapnel, burned by mustard gas and further mutilated by medical “researchers” –– from public view. Who is the beater and who is the beaten? What about the pain of the punisher? Galás stirs the damaged minds of the hospital surgeons and guards with the victims’, obscuring her cries as the pain ebbs and flows, panting or pummeling. She creak-croons as each party to this disaster would, sinister though not altogether cruel. Her piano’s stout low end comes down like a jail door; her voices hover, theremin-like. Her people, her “characters,” ascend and descend, haltingly reharmonizing, weakly but determinedly pushing forward toward their demise, or what their fates have in mind for them. Galás’ highly original use of studio effects and electronics melts down to amplify and ambiguize her soundstage, its storm clouds of sonority tormenting, perhaps comforting a roomful of zombified mummies surrendered to those who likely regard them as hunks of meat to root around in like hogs, to wade through like puddles of putrid chaos.

Coby Sey steps out with his remarkable debut album 'Conduit', set for release via AD 93 on September 9th 2022. "'Conduit' is a statement of intent, reaffirming my dedication to transcend the tangible through music – it’s my way to continue and contribute to the musical lineage laid by those before me, locally and worldwide." - Coby Sey Written, performed, instrumentation (various), produced, arranged, mixed and engineered (all tracks) by Coby Sey. Electronic percussion (tracks, 1, 2) by Raisa Mariam Khan. Tenor saxophone (tracks 1, 2, 7) and loops (7) by Ben Vince. Alto saxophone (tracks 1, 2, 7), recorder (track 7) and loops (7) by CJ Calderwood. Electric guitar (track 7) by Biu Rainey. Mastered and cut by Kassian Troyer. Photography direction by Ksenia Burnasheva and Coby Sey. Art direction by Coby Sey, Nicola Tirabasso and Tasker. Created in Lewisham, London and Hackney, London.

Listen to the fourth album by Scotland-born, LA-based Ross Birchard and you’re liable to feel a little overwhelmed. Sugar rush or religious epiphany? The elation of a good roller coaster or the nausea that sets in when the ride loses control? Birchard likes it all, and by the fistful. Nearly a decade out from his public christening as a producer for Kanye West (“Mercy,” “Blood on the Leaves”) and half of the jock-jam festival phenomenon TNGHT (with Lunice), he’s become the kind of musician it seems like he wanted to be all along: bright, weird, funky, funny, and guided by an optimism so irrepressible you wonder if, deep down, he feels a little sad. “Stump” is the most beautiful music that didn’t make *Blade Runner*. “Bicstan” is Aphex Twin for a seven-year-old’s birthday party. He can balance tracks as abstract as “Kpipe” with ones as direct as “3 Sheets to the Wind,” and the soulful lag of American rap (“Redeem”) with the momentum of UK bass (“Rain Shadow,” “Is It Supposed”), not to mention whatever neon-halo hybrid “Behold” is. This is opera for people raised on anime. And as easy as it is to imagine listening in a big, sweaty room, he knows that most of us will end up taking it in alone on headphones—and he wants us to have fun.

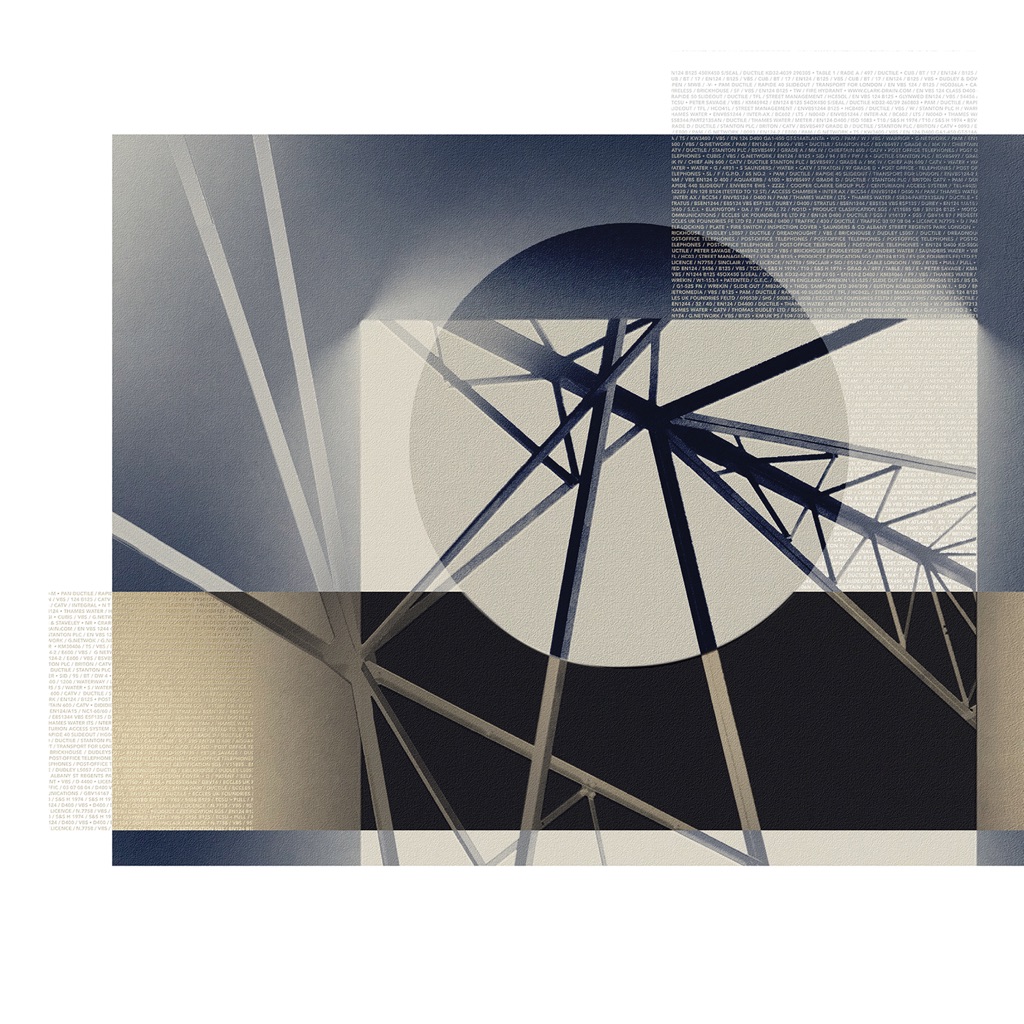

‘HOSTILE ARCHITECTURE is a sonic exploration of the ways that subjects under late capitalism are constrained and set in motion via the various structures that uphold stratification and oppression in urban contexts. It is inspired by brutalist, postmodern and utilitarian architectural structures that are found throughout post-industrial cities, hauntological in nature, being designed to provide for the populace through affordable housing but ultimately cost-cutting exercises and unfit for purpose. The term hostile architecture refers to design elements in social spaces that deter the public from using the object for means unintended by the designer, e.g. anti-homeless spikes, which the album presents as emblematic of a foundational contempt for the poor and working class, an exemplification of a status quo fortified in concrete. The album invites the listener to explore the dissonance of these contradictions in their own circumstances and perhaps consider possibilities for a world beyond what Mark Fisher called “Capitalist Realism.”’ Tragic Heroin Video: youtu.be/XBNY-l3NT9s

For fans of ’90s indie rock—your Sonic Youths, your Breeders, your Yo La Tengos—*Versions of Modern Performance* will serve as cosmic validation: Even the kids know the old ways are best. But who influenced you is never as important as what you took from them, a lesson that Chicago’s Horsegirl understands intuitively. Instead, the art is in putting it together: the haze of shoegaze and the deadpan of post-punk (“Option 8,” “Billy”), slacker confidence and twee butterflies (“Beautiful Song,” “World of Pots and Pans”). Their arty interludes they present not as free-jazz improvisers, but a teenage garage band in love with the way their amps hum (“Bog Bog 1,” “Electrolocation 2”).

Horsegirl are best friends. You don’t have to talk to the trio for more than five minutes to feel the warmth and strength of their bond, which crackles through every second of their debut full-length, Versions of Modern Performance. Penelope Lowenstein (guitar, vocals), Nora Cheng (guitar, vocals), and Gigi Reece (drums) do everything collectively, from songwriting to trading vocal duties and swapping instruments to sound and visual art design. “We made [this album] knowing so fully what we were trying to do,” the band says. “We would never pursue something if one person wasn’t feeling good about it. But also, if someone thought something was good, chances are we all thought it was good. ”Versions of Modern Performance was recorded with John Agnello (Kurt Vile, The Breeders, Dinosaur Jr.) at Electrical Audio. “It’s our debut bare-bones album in a Chicago institution with a producer who we feel like really respected what we were trying to do,” the band says. Horsegirl expertly play with texture, shape, and shade across the record, showcasing their fondness for improvisation and experimentation. Opener “Anti-glory” is elastic and bright post-punk, while the guitars in instrumental interlude “Bog Bog 1” smear across the song’s canvas like watercolors. “Dirtbag Transformation (Still Dirty)” and “World of Pots and Pans” have rough, blown-out pop charm. “The Fall of Horsegirl” is all sharp edges and dark corners.

‘Paste’ is the new album by Moin, due for release on the 28th October 2022 via AD 93. The follow up to their well received debut album ‘Moot!’, the record draws influences from alternative guitar music in its many forms, using electronic manipulations and sampling techniques to redefine it's context, not settling on any one style but moving through them in search of new connections. By exploring these relationships, Moin delivers another collage of the known and unknown, punctuated by words that are just out of reach. Mastered and cut by Noel Summerville Artwork by Joe Andrews and Tom Halstead Mixed at Hackney Road Studios

If The Smile ever seemed like a surprisingly upbeat name for a band containing two members of Radiohead (Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood, joined by Sons of Kemet drummer Tom Skinner), the trio used their debut gig to offer some clarification. Performing as part of Glastonbury Festival’s Live at Worthy Farm livestream in May 2021, Yorke announced, “We are called The Smile: not The Smile as in ‘Aaah!’—more the smile of the guy who lies to you every day.” To grasp the mood of their debut album, it’s instructive to go even deeper into a name that borrows the title of a 1970 Ted Hughes poem. In Hughes’ impressionist verse, some elemental force—compassion, humanity, love maybe—rises up to resist the deception and chicanery behind such disarming grins. And as much as the 13 songs on *A Light for Attracting Attention* sense crisis and dystopia looming, they also crackle with hope and insurrection. The pulsing electronics of opener “The Same” suggest the racing hearts and throbbing temples of our age of acute anxiety, and Yorke’s words feel like a call for unity and mobilization: “We don’t need to fight/Look towards the light/Grab it in with both hands/What you know is right.” Perennially contemplating the dynamics of power and thought, he surveys a world where “devastation has come” (“Speech Bubbles”) under the rule of “elected billionaires” (“The Opposite”), but it’s one where protest, however extreme, can still birth change (“The Smoke”). Amid scathing guitars and outbursts of free jazz, his invective zooms in on abuses of power (“You Will Never Work in Television Again”) before shaming inertia and blame-shifters on the scurrying beats and descending melodies of “A Hairdryer.” These aren’t exactly new themes for Yorke and it’s not a record that sits at an extreme outpost of Radiohead’s extended universe. Emboldened by Skinner’s fluid, intrepid rhythms, *A Light for Attracting Attention* draws frequently on various periods of Yorke and Greenwood’s past work. The emotional eloquence of Greenwood’s soundtrack projects resurfaces on “Speech Bubbles” and “Pana-Vision,” while Yorke’s fascination with digital reveries continues to be explored on “Open the Floodgates” and “The Same.” Elegantly cloaked in strings, “Free in the Knowledge” is a beautiful acoustic-guitar ballad in the lineage of Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees” and the original live version of “True Love Waits.” Of course, lesser-trodden ground is visited, too: most intriguingly, math-rock (“Thin Thing”) and folk songs fit for a ’70s sci-fi drama (“Waving a White Flag”). The album closes with “Skrting on the Surface,” a song first aired at a 2009 show Yorke played with Atoms for Peace. With Greenwood’s guitar arpeggios and Yorke’s aching falsetto, it calls back even further to *The Bends*’ finale, “Street Spirit (Fade Out).” However, its message about the fragility of existence—“When we realize we have only to die, then we’re out of here/We’re just skirting on the surface”—remains sharply resonant.

The Smile will release their highly anticipated debut album A Light For Attracting Attention on 13 May, 2022 on XL Recordings. The 13- track album was produced and mixed by Nigel Godrich and mastered by Bob Ludwig. Tracks feature strings by the London Contemporary Orchestra and a full brass section of contempoarary UK jazz players including Byron Wallen, Theon and Nathaniel Cross, Chelsea Carmichael, Robert Stillman and Jason Yarde. The band, comprising Radiohead’s Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood and Sons of Kemet’s Tom Skinner, have previously released the singles You Will Never Work in Television Again, The Smoke, and Skrting On The Surface to critical acclaim.

Éliane Radigue Frédéric Blondy Occam XXV organ reframed OR1 In 2018 experimental festival Organ Reframed commissioned Éliane Radigue to write her first work for organ, 'Occam Ocean XXV'. Radigue worked closely with organist Frédéric Blondy at the Église Saint Merry in Paris before transferring the piece to Union Chapel for its premiere at Organ Reframed on 13 October 2018. The recording on this compact disc was made at a private session at Union Chapel on 8 January 2020. 'Occam XXV' inaugurates the very special record series of works exclusively commissioned by Organ Reframed, the organ-only, one of a kind experimental music festival, carefully curated by Scottish composer/performer and London's Union Chapel organ music director Claire M Singer. Paris-born Éliane Radigue is one of the most innovative and influential living composers of all time. After working under Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry in the late 1950's/early 60's she mainly worked with tape before developing a deep relationship with modular synthesis in the early 1970's. Over the next three decades she pushed her own conceptions of musicality forward developing a deep relationship with her ARP 2500. Through endless exploration and drawing on her personal journey as a practicing Buddhist she created an entirely new landscape of experimental sound. In the early 2000's she made an extraordinary shift into writing predominantly for acoustic instruments. 'Occam XXV' is the latest chapter of Radigue's broader series of works Occam Ocean which she has been composing in the last decade. Carefully selected by Radigue she has closely collaborated with various extremely experienced yet sensitive instrumentalists. For Occam XXV Radigue collaborated with pianist, organist, composer, improviser, artistic director of the Orchestra of New Musical Creation, Experimentation and Improvisation (ONCEIM) Frédéric Blondy, which is their second collaboration in the Occam Ocean series. 'Occam XXV' premiered in 2018, and was later recorded privately in 2020 at London's Organ Reframed headquarters Union Chapel. "We live in a universe filled with waves. Not only between the Earth and the Sun but all the way down to the tiniest microwaves and inside it is the minuscule band that lies between the 60 Hz and the 12,000 to 15,000 Hz that our ears turn into sound. There are many wavelengths in the ocean too and we also come into contact with it physically, mentally and spiritually. That explains the title of this body of work which is called Occam Ocean.The main aim of this work is to focus on how the partials are dealt with. Whether they come in the form of micro beats, pulsations, harmonics, subharmonics – which are extremely rare but have a transcendent beauty – bass pulsations – the highly intangible aspect of sound. That's what makes it so rich. When Luciano Pavarotti gave free rein to the full force of his voice the conductor stopped beating time and you could hear the richness in its entirety. Music in written form, or however it is relayed, ultimately remains abstract. It's the performer, the person playing it who brings it to life. So the person playing the instrument must come first. I've always thought of performers and their instruments as one. They form a dual personality. No two performers, playing the same instrument, have the same relationship with that instrument – the same intimate relationship. This is where the process of making the work personal begins. The purely personal task of deciding on the theme or image that we're going to work from. Obviously, because this is Occam Ocean, the theme is always related to water. It could be a little stream, a fountain, the distant ocean, rivers. Out of the fifty or so musicians I've worked with no two themes have been the same. Each musician's theme is completely unique and completely personal. The music does the talking. This is one of those art forms that manages to express the many things that words aren't able to. Even at an early stage, all those ideas need to have been brought together." - Éliane Radigue Since its conception in 2016, Organ Reframed has commissioned artists including Low, Hildur Guðnadóttir, Philip Jeck, Phill Niblock, Mark Fell, Mira Calix, Darkstar, Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith, Sarah Davachi, hailing from London's Union Chapel, ending up also in Amsterdam and Moscow. Organ Reframed will be back this year on September 16--18 with Abul Mogard, Ipek Gorgun, Anna von Hausswolff, Claire M Singer and Cabaret Voltaire's Chris Watson. "The idea of Organ Reframed dates back to 2006 when I was commissioned to write my first organ piece. At the time I was mostly composing in the studio and was struck by the vast breadth of the instrument and how capable it was of creating timbres that were similar to what I was working with electronically. The lush acoustic quality of the sound resonating in the space was incredible and the sonic possibilities seemed endless. I felt so fortunate to have had the time to experiment and explore the instrument and realised perhaps the reason there wasn’t a huge amount of experimental works being written for organ was because they are mainly housed in churches and concert halls so you really need to know someone with a key. From that point on I started composing almost exclusively for organ and since launching Organ Reframed in 2016 I am now able to give fellow artists the opportunity to explore what an incredible instrument it is." - Claire M Singer. Union Chapel's 1877 organ built by master organ builder Father Henry Willis is known to be on of the finest in the world. It is one of very few organs left in UK with a fully working hydraulics (water powered) which can be used an alternative to the electric blowing system. The organ is completely hidden from the listeners allowing to focus solely on the music.

Dewa Alit, Bali’s master of contemporary Gamelan composition, returns to Black Truffle with Chasing the Phantom, presenting two recent works played by the composer’s Gamelan Salukat, a large ensemble that performs on instruments specially built to his designs, using a unique tuning system that combines notes from two traditional Balinese Gamelan scales. Alit explains that the ensemble’s name suggests “a place to fuse creative ideas to generate new, innovative works” and both compositions demonstrate the composer’s ability to wring stunning new possibilities from variations on the traditional Gamelan ensemble. While using familiar elements of Balinese Gamelan music, such as unison scalar melodies and stop-start dynamics, Alit’s music is overflowing with harmonic, rhythmic, and timbral inventions, the latter often facilitated by unorthodox playing techniques. “Ngejuk Memedi”, an English translation of which gives the LP its title, results from Alit’s reflection on the complex relationship between tradition and modernity in Balinese culture, particularly in the way that belief in the phantoms or spirits known as ‘memedi’ are shared through social media using digital technologies. Embodying this uncanny co-existence, the opening passages of the piece are at once immediately recognisable in their use of the metallophones of the Gamelan ensemble and strikingly reminiscent of electronics in their timbre and movement. At points, what we hear seems to have been fragmented with digital tools, or even to originate in some incessantly glitching DX7. Short melodic figures loop irregularly, with the ensemble splintering into polyrhythmic shards before unexpectedly recombining for intricate unison passages. After several minutes of this manically tinkling metallic sound world, the metallophones are joined by drums for a meditative passage of lower dynamics, as the uniformly high pitch range explored in the opening sections gradually opens up to include resonant low gong hits. Recovering some of the manic energy of the opening, but now enhanced with the full range of percussion, the piece weaves through a series of tempo changes to a stunning passage of rapid-fire melodies and ringing chords that sweep across the metallophones, their unorthodox tuning creating complex clouds of wavering harmonies. “Likad”, written during Covid-19 lockdowns, channels anxiety and uncertainty into musical form, resulting in a piece that, even by Alit’s standards, is stunning in its complexity and the virtuosity it demands of Gamelan Salukat. Its opening section is perhaps most remarkable for its mastery of texture, with rapid transitions between dry, muted strikes and metallic shimmers calling to mind the use of filters in electronic music. At points, the complex irregular repetitions of short melodic patterns, where the music seems to get stuck or be suddenly interrupted by a skip, recall the mad sampler works of Alvin Curran or the skittering surface of prime period Oval more than anything familiar from acoustic percussion music. Moving through a dizzying series of twists and turns, the piece ends with a majestic sequence of chords possessing an almost hieratic power. A major statement from a radical contemporary composer, one cannot help but agree with Alit when he sees Chasing the Phantom as an answer to the “question of the future of Gamelan music”.