The Guardian's 50 Best Albums of 2020

Our countdown is complete, topped by a mercurial work of sprawling invention by a woman who has dug deep to survive. Taken as a whole, these choices contain drama, solace, poetry and fire, a fitting selection for a turbulent year

Published: December 18, 2020 08:07

Source

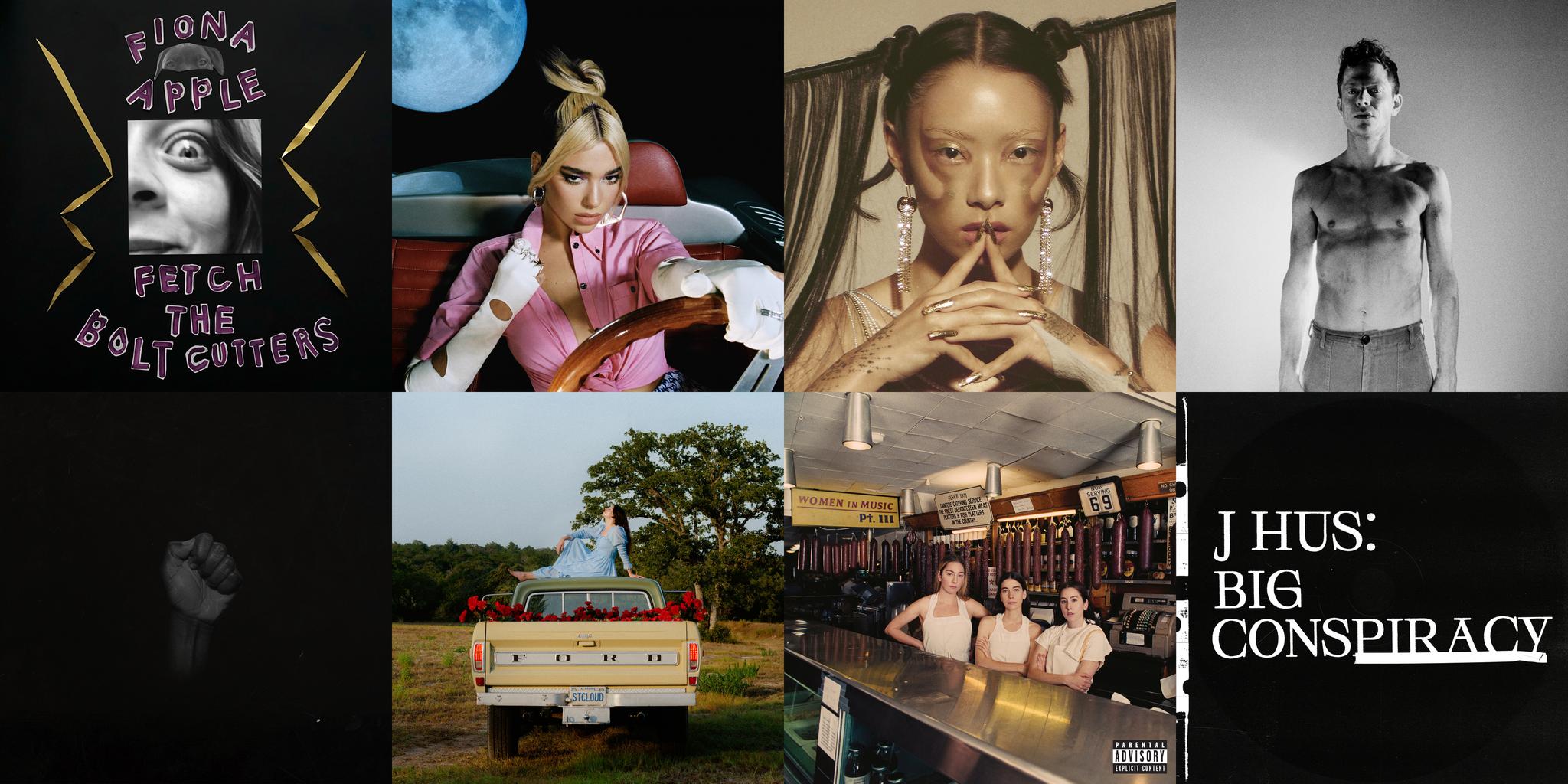

You don’t need to know that Fiona Apple recorded her fifth album herself in her Los Angeles home in order to recognize its handmade clatter, right down to the dogs barking in the background at the end of the title track. Nor do you need to have spent weeks cooped up in your own home in the middle of a global pandemic in order to more acutely appreciate its distinct banging-on-the-walls energy. But it certainly doesn’t hurt. Made over the course of eight years, *Fetch the Bolt Cutters* could not possibly have anticipated the disjointed, anxious, agoraphobic moment in history in which it was released, but it provides an apt and welcome soundtrack nonetheless. Still present, particularly on opener “I Want You to Love Me,” are Apple’s piano playing and stark (and, in at least one instance, literal) diary-entry lyrics. But where previous albums had lush flourishes, the frenetic, woozy rhythm section is the dominant force and mood-setter here, courtesy of drummer Amy Wood and former Soul Coughing bassist Sebastian Steinberg. The sparse “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” is backed by drumsticks seemingly smacking whatever surface might be in sight. “Relay” (featuring a refrain, “Evil is a relay sport/When the one who’s burned turns to pass the torch,” that Apple claims was excavated from an old journal from written she was 15) is driven almost entirely by drums that are at turns childlike and martial. None of this percussive racket blunts or distracts from Apple’s wit and rage. There are instantly indelible lines (“Kick me under the table all you want/I won’t shut up” and the show-stopping “Good morning, good morning/You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in”), all in the service of channeling an entire society’s worth of frustration and fluster into a unique, urgent work of art that refuses to sacrifice playfulness for preaching.

“It was about halfway through this process that I realized,” Rina Sawayama tells Apple Music, “that this album is definitely about family.” While it’s a deeply personal, genre-fluid exploration, the Japanese British artist is frank about drawing on collaborative hands to flesh out her full kaleidoscopic vision. “If I was stuck, I’d always reach out to songwriter friends and say, ‘Hey, can you help me with this melody or this part of the song?’” she says. “Adam Hann from The 1975, for example, helped rerecord a lot of guitar for us, which was insane.” Born in Niigata in northwestern Japan before her family moved to London when she was five, Sawayama graduated from Cambridge with a degree in politics, psychology, and sociology and balanced a fledgling music career’s uncertainty with the insurance of professional modeling. The leftfield pop on her 2017 mini-album *RINA* offered significant promise, but this debut album is a Catherine wheel of influences (including, oddly thrillingly, nu metal), dispatched by a pop rebel looking to take us into her future. “My benchmark is if you took away all the production and you’re left with just the melody, does it still sound pop?” she says. “The gag we have is that it’ll be a while until I start playing stadiums. But I want to put that out into the universe. It’s going to happen one day.” Listen to her debut album to see why we feel that confidence is not misplaced—and read’s Rina’s track-by-track guide. **Dynasty** “I think thematically and lyrically it makes sense to start off with this. I guess I come from a bit of an academic background, so I always approach things like a dissertation. The title of the essay would be ‘Won\'t you break the chain with me?’ It\'s about intergenerational pain, and I\'m asking the listener to figure out this whole world with me. It\'s an invitation. I\'d say ‘Dynasty’ is one of the craziest in terms of production. I think we had 250 tracks in Logic at one point.” **XS** “I wrote this with Nate Campany, Kyle Shearer, and Chris Lyon, who are super pop writers. It was the first session we ever did together in LA. They were noodling around with guitar riffs and I was like, ‘I want to write something that\'s really abrasive, but also pop that freaks you out.’ It\'s the good amount of jarring, the good side of jarring that it wakes you up a little bit every four bars or whatever. I told them, \'I really love N.E.R.D and I just want to hear those guitars.’” **STFU!** “I wanted to shock people because I\'d been away for a while. The song before this was \[2018 single\] \'Flicker,\' and that\'s just so happy and empowering in a different way. I wanted to wake people up a little bit. It\'s really fun to play with people\'s emotions, but if fundamentally the core of the song again is pop, then people get it, and a lot of people did here. I was relieved.” **Comme Des Garçons (Like the Boys)** \"It\'s one of my favorite basslines. It was with \[LA producers and singer-songwriters\] Bram Inscore and Nicole Morier, who\'s done a lot of stuff with Britney. I think this was our second session together. I came into it and said, \'Yeah, I think I want to write about toxic masculinity.\' Then Nicole was like, ‘Oh my god, that\'s so funny, because I was just thinking about Beto O\'Rourke and how he\'d lost the primary in Texas, but still said, essentially, \'I was born to win it, so it’s fine.’” **Akasaka Sad** “This was one of the songs that I wrote alone. It is personal, but I always try and remove my ego and try to think of the end result, which is the song. There\'s no point fighting over whether it\'s 100% authentically personal. I think there\'s ways to tell stories in songs that is personal, but also general. *RINA* was just me writing lyrics and melody and then \[UK producer\] Clarence Clarity producing. This record was the first time that I\'d gone in with songwriters. Honestly, up until then I was like, \'So what do they actually do? I don\'t understand what they would do in a session.\' I didn\'t understand how they could help, but it\'s only made my lyrics better and my melodies better.” **Paradisin’** “I wanted to write a theme song for a TV show. Like if my life, my teenage years, was like a TV show, then what would be the soundtrack, the opening credits? It really reminded me of *Ferris Bueller\'s Day Off* and that kind of fast BPM you’d get in the ’80s. I think it\'s at 130 or 140 BPM. I was really wild when I was a teenager, and that sense of adventure comes from a production like that. There\'s a bit in the song where my mum\'s telling me off, but that\'s actually my voice. I realized that if I pitched my voice down, I sound exactly like my mum.” **Love Me 4 Me** “For me, this was a message to myself. I was feeling so under-confident with my work and everything. I think on the first listen it just sounds like trying to get a lover to love you, but it\'s not at all. Everything is said to the mirror. That\'s why the spoken bit at the beginning and after the middle eight is like: \'If you can\'t love yourself, how are you going to love somebody else?\' That\'s a RuPaul quote, so it makes me really happy, but it\'s so true. I think that\'s very fundamental when being in a relationship—you\'ve got to love yourself first. I think self-love is really hard, and that\'s the overall thing about this record: It\'s about trying to find self-love within all the complications, whether it\'s identity or sexuality. I think it\'s the purest, happiest on the record. It’s like that New Jack Swing-style production, but originally it had like an \'80s sound. That didn\'t work with the rest of the record, so we went back and reproduced it.” **Bad Friend** “I think everyone\'s been a bad friend at some point, and I wanted to write a very pure song about it. Before I went in to write that, I\'d just seen an old friend. She\'s had a baby. I\'d seen that on Facebook, and I hadn\'t been there for it at all, so I was like, ‘What!’ We fell out, basically. In the song, in the first verse, we talk about Japan and the mad, fun group trip we went on. The vocoder in the chorus sort of reflects just the emptiness you feel, almost like you\'ve been let go off a rollercoaster. I do have a tendency to fall head-first into new relationships, romantic relationships, and leave my friends a little bit. She\'s been through three of my relationships like a rock. Now I realize that she just felt completely left behind. I\'m going to send it to her before it comes out. We\'re now in touch, so it\'s good.” **F\*\*k This World (Interlude)** “Initially, this song was longer, but I feel like it just tells the story already. Sometimes a song doesn\'t need that full structure. I wanted it to feel like I\'m dissociating from what\'s happening on Earth and floating in space and looking at the world from above. Then the song ends with a radio transmission and then I get pulled right back down to Earth, and obviously a stadium rock stage, which is…” **Who’s Gonna Save U Now?** “When \[UK producer and songwriter\] Rich Cooper, \[UK songwriter\] Johnny Latimer, and I first wrote this, it was like a \'90s Britney song. It wasn\'t originally stadium rock. Then I watched \[2018’s\] *A Star Is Born* and *Bohemian Rhapsody* in the same week. In *A Star Is Born*, there\'s that first scene where he\'s in front of tens of thousands of people, but it\'s very loaded. He comes off stage and he doesn\'t know who he is. The stage means a lot in movies. For Freddie Mercury too: Despite any troubles, he was truly himself when he was onstage. I felt the stage was an interesting metaphor for not just redemption, but that arc of storytelling. Even when I was getting bullied at school, I never thought, \'Oh, I\'ll do the same back to them.\' I just felt: \'I\'m going to become successful so that you guys rethink your ways.\' For me, this song is the whole redemption stadium rock moment. I\'ve never wanted revenge on people.” **Tokyo Love Hotel** “I\'d just come back from a trip to Japan and witnessed these tourists yelling in the street. They were so loud and obnoxious, and Japan\'s just not that kind of country. I was thinking about the \[2021\] Olympics. Like, \'Oh god, the people who are going to come and think it\'s like Disneyland and just trash the place.\' Japanese people are so polite and respectful, and I feel that culture in me. There are places in Japan called love hotels, where people just go to have sex. You can book the room to simply have sex. I felt like these tourists were treating Japan as a country or Tokyo as a city in that way. They just come and have casual sex in it, and then they leave. They’ll say, ‘That was so amazing, I love Tokyo,\' but they don’t give a shit about the people or don\'t know anything about the people and how difficult it is to grow up there. Then at the end of each verse, I say, \'Oh, but this is just another song about Tokyo,\' referring back to my trip that I had in \'Bad Friend\' where I was that tourist and I was going crazy. It\'s my struggle with feeling like an outsider in Japan, but also feeling like I\'m really part of it. I look the same as everyone else, but feel like an outsider, still.” **Chosen Family** “I wrote this thinking about my chosen family, which is my LGBTQ sisters and brothers. I mean, at university, and at certain points in my life where I\'ve been having a hard time, the LGBTQ community has always been there for me. The concept of chosen family has been long-standing in the queer community because a lot of people get kicked out of their homes and get ostracized from their family for coming out or just living true to themselves. I wanted to write a song literally for them, and it\'s just a message and this idea of a safe space—an actual physical space.” **Snakeskin** “This has a Beethoven sample \[Piano Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, Op. 13 ‘Pathétique’\]. It’s a song that my mum used to play on the piano. It’s the only song I remember her playing, and it only made sense to end with that. I wanted it to end with her voice, and that\'s her voice, that little more crackle of the end. The metaphor of ‘Snakeskin’ is a handbag, really. A snakeskin handbag that people commercialize, consume, and use as they want. At the end my mum says in Japanese, ‘I\'ve realized that now I want to see who I want to see, do what I want to do, be who I want to be.’ I interviewed her about how it felt to turn 60 on her birthday, after having been through everything she’s gone through. For her to say that…I just needed to finish the record on that note.”

Mike Hadreas’ fifth LP under the Perfume Genius guise is “about connection,” he tells Apple Music. “And weird connections that I’ve had—ones that didn\'t make sense but were really satisfying or ones that I wanted to have but missed or ones that I don\'t feel like I\'m capable of. I wanted to sing about that, and in a way that felt contained or familiar or fun.” Having just reimagined Bobby Darin’s “Not for Me” in 2018, Hadreas wanted to bring the same warmth and simplicity of classic 1950s and \'60s balladry to his own work. “I was thinking about songs I’ve listened to my whole life, not ones that I\'ve become obsessed over for a little while or that are just kind of like soundtrack moments for a summer or something,” he says. “I was making a way to include myself, because sometimes those songs that I love, those stories, don\'t really include me at all. Back then, you couldn\'t really talk about anything deep. Everything was in between the lines.” At once heavy and light, earthbound and ethereal, *Set My Heart on Fire Immediately* features some of Hadreas’ most immediate music to date. “There\'s a confidence about a lot of those old dudes, those old singers, that I\'ve loved trying to inhabit in a way,” he says. “Well, I did inhabit it. I don\'t know why I keep saying ‘try.’ I was just going to do it, like, ‘Listen to me, I\'m singing like this.’ It\'s not trying.” Here, he walks us through the album track by track. **Whole Life** “When I was writing that song, I just had that line \[‘Half of my whole life is done’\]—and then I had a decision afterwards of where I could go. Like, I could either be really resigned or I could be open and hopeful. And I love the idea. That song to me is about fully forgiving everything or fully letting everything go. I’ve realized recently that I can be different, suddenly. That’s been a kind of wild thing to acknowledge, and not always good, but I can be and feel completely different than I\'ve ever felt and my life can change and move closer to goodness, or further away. It doesn\'t have to be always so informed by everything I\'ve already done.” **Describe** “Originally, it was very plain—sad and slow and minimal. And then it kind of morphed, kind of went to the other side when it got more ambient. When I took it into the studio, it turned into this way dark and light at the same time. I love that that song just starts so hard and goes so full-out and doesn\'t let up, but that the sentiment and the lyric and my singing is still soft. I was thinking about someone that was sort of near the end of their life and only had like 50% of their memories, or just could almost remember. And asking someone close to them to fill the rest in and just sort of remind them what happened to them and where they\'ve been and who they\'d been with. At the end, all of that is swimming together.” **Without You** “The song is about a good moment—or even just like a few seconds—where you feel really present and everything feels like it\'s in the right place. How that can sustain you for a long time. Especially if you\'re not used to that. Just that reminder that that can happen. Even if it\'s brief, that that’s available to you is enough to kind of carry you through sometimes. But it\'s still brief, it\'s still a few seconds, and when you tally everything up, it\'s not a lot. It\'s not an ultra uplifting thing, but you\'re not fully dragged down. And I wanted the song to kind of sound that same way or at least push it more towards the uplift, even if that\'s not fully the sentiment.” **Jason** “That song is very much a document of something that happened. It\'s not an idea, it’s a story. Sometimes you connect with someone in a way that neither of you were expecting or even want to connect on that level. And then it doesn\'t really make sense, but you’re able to give each other something that the other person needs. And so there was this story at a time in my life where I was very selfish. I was very wild and reckless, but I found someone that needed me to be tender and almost motherly to them. Even if it\'s just for a night. And it was really kind of bizarre and strange and surreal, too. And also very fueled by fantasy and drinking. It\'s just, it\'s a weird therapeutic event. And then in the morning all of that is just completely gone and everybody\'s back to how they were and their whole bundle of shit that they\'re dealing with all the time and it\'s like it never happened.” **Leave** “That song\'s about a permanent fantasy. There\'s a place I get to when I\'m writing that feels very dramatic, very magical. I feel like it can even almost feel dark-sided or supernatural, but it\'s fleeting, and sometimes I wish I could just stay there even though it\'s nonsense. I can\'t stay in my dark, weird piano room forever, but I can write a song about that happening to me, or a reminder. I love that this song then just goes into probably the poppiest, most upbeat song that I\'ve ever made directly after it. But those things are both equally me. I guess I\'m just trying to allow myself to go all the places that I instinctually want to go. Even if they feel like they don\'t complement each other or that they don\'t make sense. Because ultimately I feel like they do, and it\'s just something I told myself doesn\'t make sense or other people told me it doesn\'t make sense for a long time.” **On the Floor** “It started as just a very real song about a crush—which I\'ve never really written a song about—and it morphed into something a little darker. A crush can be capable of just taking you over and can turn into just full projection and just fully one-sided in your brain—you think it\'s about someone else, but it\'s really just something for your brain to wild out on. But if that\'s in tandem with being closeted or the person that you like that\'s somehow being wrong or not allowed, how that can also feel very like poisonous and confusing. Because it\'s very joyous and full of love, but also dark and wrong, and how those just constantly slam against each other. I also wanted to write a song that sounded like Cyndi Lauper or these pop songs, like, really angsty teenager pop songs that I grew up listening to that were really helpful to me. Just a vibe that\'s so clear from the start and sustained and that every time you hear it you instantly go back there for your whole life, you know?” **Your Body Changes Everything** “I wrote ‘Your Body Changes Everything’ about the idea of not bringing prescribed rules into connection—physical, emotional, long-term, short-term—having each of those be guided by instinct and feel, and allowed to shift and change whenever it needed to. I think of it as a circle: how you can be dominant and passive within a couple of seconds or at the exact same time, and you’re given room to do that and you’re giving room to someone else to do that. I like that dynamic, and that can translate into a lot of different things—into dance or sex or just intimacy in general. A lot of times, I feel like I’m supposed to pick one thing—one emotion, one way of being. But sometimes, I’m two contradicting things at once. Sometimes, it seems easier to pick one, even if it’s the worse one, just because it’s easier to understand. But it’s not for me.” **Moonbend** “That\'s a very physical song to me. It\'s very much about bodies, but in a sort of witchy way. This will sound really pretentious, but I wasn\'t trying to write a chorus or like make it like a sing-along song, I was just following a wave. So that whole song feels like a spell to me—like a body spell. I\'m not super sacred about the way things sound, but I can be really sacred about the vibe of it. And I feel like somehow we all clicked in to that energy, even though it felt really personal and almost impossible to explain, but without having to, everybody sort of fell into it. The whole thing was really satisfying in a way that nobody really had to talk about. It just happened.” **Just a Touch** “That song is like something I could give to somebody to take with them, to remember being with me when we couldn\'t be with each other. Part of it\'s personal and part of it I wasn\'t even imagining myself in that scenario. It kind of starts with me and then turns into something, like a fiction in a way. I wanted it to be heavy and almost narcotic, but still like honey on the body or something. I don\'t want that situation to be hot—the story itself and the idea that you can only be with somebody for a brief amount of time and then they have to leave. You don\'t want anybody that you want to be with to go. But sometimes it\'s hot when they\'re gone. It’s hard to be fully with somebody when they\'re there. I take people for granted when they\'re there, and I’m much less likely to when they\'re gone. I think everybody is like that, but I might take it to another level sometimes.” **Nothing at All** “There\'s just some energetic thing where you just feel like the circle is there: You are giving and receiving or taking, and without having to say anything. But that song, ultimately, is about just being so ready for someone that whatever they give you is okay. They could tell you something really fucked up and you\'re just so ready for them that it just rolls off you. It\'s like we can make this huge dramatic, passionate thing, but if it\'s really all bullshit, that\'s totally fine with me too. I guess because I just needed a big feeling. I don\'t care in the end if it\'s empty.” **One More Try** “When I wrote my last record, I felt very wild and the music felt wild and the way that I was writing felt very unhinged. But I didn\'t feel that way. And with this record I actually do feel it a little, but the music that I\'m writing is a lot more mature and considered. And there\'s something just really, really helpful about that. And that song is about a feeling that could feel really overwhelming, but it\'s written in a way that feels very patient and kind.” **Some Dream** “I think I feel very detached a lot of the time—very internal and thinking about whatever bullshit feels really important to me, and there\'s not a lot of room for other people sometimes. And then I can go into just really embarrassing shame. So it\'s about that idea, that feeling like there\'s no room for anybody. Sometimes I always think that I\'m going to get around to loving everybody the way that they deserve. I\'m going to get around to being present and grateful. I\'m going to get around to all of that eventually, but sometimes I get worried that when I actually pick my head up, all those things will be gone. Or people won\'t be willing to wait around for me. But at the same time that I feel like that\'s how I make all my music is by being like that. So it can be really confusing. Some of that is sad, some of that\'s embarrassing, some of that\'s dramatic, some of it\'s stupid. There’s an arc.” **Borrowed Light** “Probably my favorite song on the record. I think just because I can\'t hear it without having a really big emotional reaction to it, and that\'s not the case with a lot of my own songs. I hate being so heavy all the time. I’m very serious about writing music and I think of it as this spiritual thing, almost like I\'m channeling something. I’m very proud of it and very sacred about it. But the flip side of that is that I feel like I could\'ve just made that all up. Like it\'s all bullshit and maybe things are just happening and I wasn\'t anywhere before, or I mean I\'m not going to go anywhere after this. This song\'s about what if all this magic I think that I\'m doing is bullshit. Even if I feel like that, I want to be around people or have someone there or just be real about it. The song is a safe way—or a beautiful way—for me to talk about that flip side.”

AN IMPRESSION OF PERFUME GENIUS’ SET MY HEART ON FIRE IMMEDIATELY By Ocean Vuong Can disruption be beautiful? Can it, through new ways of embodying joy and power, become a way of thinking and living in a world burning at the edges? Hearing Perfume Genius, one realizes that the answer is not only yes—but that it arrived years ago, when Mike Hadreas, at age 26, decided to take his life and art in to his own hands, his own mouth. In doing so, he recast what we understand as music into a weather of feeling and thinking, one where the body (queer, healing, troubled, wounded, possible and gorgeous) sings itself into its future. When listening to Perfume Genius, a powerful joy courses through me because I know the context of its arrival—the costs are right there in the lyrics, in the velvet and smoky bass and synth that verge on synesthesia, the scores at times a violet and tender heat in the ear. That the songs are made resonant through the body’s triumph is a truth this album makes palpable. As a queer artist, this truth nourishes me, inspires me anew. This is music to both fight and make love to. To be shattered and whole with. If sound is, after all, a negotiation/disruption of time, then in the soft storm of Set My Heart On Fire Immediately, the future is here. Because it was always here. Welcome home.

Released on Juneteenth 2020, the third album by the enigmatic-slash-anonymous band Sault is an unapologetic dive into Black identity. Tapping into ’90s-style R&B (“Sorry Ain’t Enough”), West African funk (“Bow”), early ’70s soul (“Miracles”), churchy chants (“Out the Lies”), and slam-poetic interludes (“Us”), the flow here is more mixtape or DJ set than album, a compendium of the culture rather than a distillation of it. What’s remarkable is how effortless they make revolution sound.

Proceeds will be going to charitable funds

“Place and setting have always been really huge in this project,” Katie Crutchfield tells Apple Music of Waxahatchee, which takes its name from a creek in her native Alabama. “It’s always been a big part of the way I write songs, to take people with me to those places.” While previous Waxahatchee releases often evoked a time—the roaring ’90s, and its indie rock—Crutchfield’s fifth LP under the Waxahatchee alias finds Crutchfield finally embracing her roots in sound as well. “Growing up in Birmingham, I always sort of toed the line between having shame about the South and then also having deep love and connection to it,” she says. “As I started to really get into alternative country music and Lucinda \[Williams\], I feel like I accepted that this is actually deeply in my being. This is the music I grew up on—Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, the powerhouse country singers. It’s in my DNA. It’s how I learned to sing. If I just accept and embrace this part of myself, I can make something really powerful and really honest. I feel like I shed a lot of stuff that wasn\'t serving me, both personally and creatively, and it feels like *Saint Cloud*\'s clean and honest. It\'s like this return to form.” Here, Crutchfield draws us a map of *Saint Cloud*, with stories behind the places that inspired its songs—from the Mississippi to the Mediterranean. WEST MEMPHIS, ARKANSAS “Memphis is right between Birmingham and Kansas City, where I live currently. So to drive between the two, you have to go through Memphis, over the Mississippi River, and it\'s epic. That trip brings up all kinds of emotions—it feels sort of romantic and poetic. I was driving over and had this idea for \'**Fire**,\' like a personal pep talk. I recently got sober and there\'s a lot of work I had to do on myself. I thought it would be sweet to have a song written to another person, like a traditional love song, but to have it written from my higher self to my inner child or lower self, the two selves negotiating. I was having that idea right as we were over the river, and the sun was just beating on it and it was just glowing and that lyric came into my head. I wanted to do a little shout-out to West Memphis too because of \[the West Memphis Three\]—that’s an Easter egg and another little layer on the record. I always felt super connected to \[Damien Echols\], watching that movie \[*Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills*\] as a teenager, just being a weird, sort of dark kid from the South. The moment he comes on the screen, I’m immediately just like, ‘Oh my god, that guy is someone I would have been friends with.’ Being a sort of black sheep in the South is especially weird. Maybe that\'s just some self-mythology I have, like it\'s even harder if you\'re from the South. But it binds you together.” BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA “Arkadelphia Road is a real place, a road in Birmingham. It\'s right on the road of this little arts college, and there used to be this gas station where I would buy alcohol when I was younger, so it’s tied to this seediness of my past. A very profound experience happened to me on that road, but out of respect, I shouldn’t give the whole backstory. There is a person in my life who\'s been in my life for a long time, who is still a big part of my life, who is an addict and is in recovery. It got really bad for this person—really, really bad. \[\'**Arkadelphia**\'\] is about when we weren’t in recovery, and an experience that we shared. One of the most intense, personal songs I\'ve ever written. It’s about growing up and being kids and being innocent and watching this whole crazy situation play out while I was also struggling with substances. We now kind of have this shared recovery language, this shared crazy experience, and it\'s one of those things where when we\'re in the same place, we can kind of fit in the corner together and look at the world with this tent, because we\'ve been through what we\'ve been through.” RUBY FALLS, TENNESSEE “It\'s in Chattanooga. A waterfall that\'s in a cave. My sister used to live in Chattanooga, and that drive between Birmingham and Chattanooga, that stretch of land between Alabama, Georgia, into Tennessee, is so meaningful—a lot of my formative time has been spent driving that stretch. You pass a few things. One is Noccalula Falls, which I have a song about on my first album called ‘Noccalula.’ The other is Ruby Falls. \[‘**Ruby Falls**’\] is really dense—there’s a lot going on. It’s about a friend of mine who passed away from a heroin overdose, and it’s for him—my song for all people who struggle with that kind of thing. I sang a song at his funeral when he died. This song is just all about him, about all these different places that we talked about, or that we’d spend so much time at Waxahatchee Creek together. The beginning of the song is sort of meant to be like the high. It starts out in the sky, and that\'s what I\'m describing, as I take flight, up above everybody else. Then the middle part is meant to be like this flashback but it\'s taking place on earth—it’s actually a reference to *Just Kids*, Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe. It’s written with them in mind, but it\'s just about this infectious, contagious, intimate friendship. And the end of the song is meant to represent death or just being below the surface and being gone, basically.” ST. CLOUD, FLORIDA “It\'s where my dad is from, where he was born and where he grew up. The first part of \[\'**St. Cloud**\'\] is about New York. So I needed a city that was sort of the opposite of New York, in my head. I wasn\'t going to do like middle-of-nowhere somewhere; I really did want it to be a place that felt like a city. But it just wasn’t cosmopolitan. Just anywhere America, and not in a bad way—in a salt-of-the-earth kind of way. As soon as the idea to just call the whole record *Saint Cloud* entered my brain, it didn\'t leave. It had been the name for six months or something, and I had been calling it *Saint Cloud*, but then David Berman died and I was like, ‘Wow, that feels really kismet or something,’ because he changed his middle name to Cloud. He went by David Cloud Berman. I\'m a fan; it feels like a nice way to \[pay tribute\].” BARCELONA, SPAIN “In the beginning of\* \*‘**Oxbow**’ I say ‘Barna in white,’ and ‘Barna’ is what people call Barcelona. And Barcelona is where I quit drinking, so it starts right at the beginning. I like talking about it because when I was really struggling and really trying to get better—and many times before I actually succeeded at that—it was always super helpful for me to read about other musicians and just people I looked up to that were sober. It was during Primavera \[Sound Festival\]. It’s sort of notoriously an insane party. I had been getting close to quitting for a while—like for about a year or two, I would really be not drinking that much and then I would just have a couple nights where it would just be really crazy and I would feel so bad, and it affected all my relationships and how I felt about music and work and everything. I had the most intense bout of that in Barcelona right at the beginning of this tour, and as I was leaving I was going from there to Portugal and I just decided, ‘I\'m just going to not.’ I think in my head I was like, ‘I\'m actually done,’ but I didn\'t say that to everybody. And then that tour went into another tour, and then to the summer, and then before you know it I had been sober six months, and then I was just like, ‘I do not miss that at all.’ I\'ve never felt more like myself and better. It was the site of my great realization.”

HAIM only had one rule when they started working on their third album: There would be no rules. “We were just experimenting,” lead singer and middle sibling Danielle Haim tells Apple Music. “We didn’t care about genre or sticking to any sort of script. We have the most fun when nothing is off limits.” As a result, *Women in Music Pt. III* sees the Los Angeles sisters embrace everything from thrillingly heavy guitar to country anthems and self-deprecating R&B. Amid it all, gorgeous saxophone solos waft across the album, transporting you straight to the streets of their hometown on a sunny day. In short, it’s a fittingly diverse effort for a band that\'s always refused, in the words of Este Haim, to be “put in a box.” “I just hope people can hear how much fun we had making it,” adds Danielle, who produced the album alongside Rostam Batmanglij and Ariel Rechtshaid—a trio Alana Haim describes as “the Holy Trinity.” “We wanted it to sound fun. Everything about the album was just spontaneous and about not taking ourselves too seriously.” Yet, as fun-filled as they might be, the tracks on *Women in Music Pt. III* are also laced with melancholy, documenting the collective rock bottom the Haim sisters hit in the years leading up to the album’s creation. These songs are about depression, seeking help, grief, failing relationships, and health issues (Este has type 1 diabetes). “A big theme in this album is recognizing your sadness and expelling it with a lot of aggression,” says Danielle, who wanted the album to sound as raw and up close as the subjects it dissects. “It feels good to scream it in song form—to me that’s the most therapeutic thing I can do.” Elsewhere, the band also comes to terms with another hurdle: being consistently underestimated as female musicians. (The album’s title, they say, is a playful “invite” to stop asking them about being women in music.) The album proved to be the release they needed from all of those experiences—and a chance to celebrate the unshakable sibling support system they share. “This is the most personal record we’ve ever put out,” adds Alana. “When we wrote this album, it really did feel like collective therapy. We held up a mirror and took a good look at ourselves. It’s allowed us to move on.” Let HAIM guide you through *Women in Music Pt. III*, one song at a time. **Los Angeles** Danielle Haim: “This was one of the first songs we wrote for the album. It came out of this feeling when we were growing up that Los Angeles had a bad rep. It was always like, ‘Ew, Los Angeles!’ or ‘Fuck LA!’ Especially in 2001 or so, when all the music was coming out of New York and all of our friends ended up going there for college. And if LA is an eyeroll, the Valley—where we come from—is a constant punchline. But I always had such pride for this city. And then when our first album came out, all of a sudden, the opinion of LA started to change and everyone wanted to move here. It felt a little strange, and it was like, ‘Maybe I don’t want to live here anymore?’ I’m waiting for the next mass exodus out of the city and people being like, ‘This place sucks.’ Anyone can move here, but you’ve got to have LA pride from the jump.” **The Steps** Danielle: “With this album, we were reckoning with a lot of the emotions we were feeling within the business. This album was kind of meant to expel all of that energy and almost be like ‘Fuck it.’ This song kind of encapsulates the whole mood of the record. The album and this song are really guitar-driven \[because\] we just really wanted to drive that home. Unfortunately, I can already hear some macho dude being like, ‘That lick is so easy or simple.’ Sadly, that’s shit we’ve had to deal with. But I think this is the most fun song we’ve ever written. It’s such a live, organic-sounding song. Just playing it feels empowering.” Este Haim: “People have always tried to put us in a box, and they just don’t understand what we do. People are like, ‘You dance and don’t play instruments in your videos, how are you a band?’ It’s very frustrating.” **I Know Alone** Danielle: “We wrote this one around the same time that we wrote ‘Los Angeles,’ just in a room on GarageBand. Este came up with just that simple bassline. And we kind of wrote the melody around that bassline, and then added those 808 drums in the chorus. It’s about coming out of a dark place and feeling like you don\'t really want to deal with the outside world. Sometimes for me, being at home alone is the most comforting. We shout out Joni Mitchell in this song; our mom was such a huge fan of hers and she kind of introduced us to her music when we were really little. I\'d always go into my room and just blast Joni Mitchell super loud. And I kept finding albums of hers as we\'ve gotten older and need it now. I find myself screaming to slow Joni Mitchell songs in my car. This song is very nostalgic for her.” **Up From a Dream** Danielle: “This song literally took five minutes to write, and it was written with Rostam. It’s about waking up to a reality that you just don’t want to face. In a way, I don’t really want to explain it: It can mean so many different things to different people. This is the heaviest song we’ve ever had. It’s really cool, and I think this one will be really fun to play live. The guitar solo alone is really fun.” **Gasoline** Danielle: “This was another really quick one that we wrote with Rostam. The song was a lot slower originally, and then we put that breakbeat-y drumbeat on it and all of a sudden it turned into a funky sort of thing, and it really brought the song to life. I love the way that the drums sound. I feel like we really got that right. I was like literally in a cave of blankets, a fort we created with a really old Camco drum set from the ’70s, to make sure we got that dry, tight drum sound. That slowed-down ending is due to Ariel. He had this crazy EDM filter he stuck on the guitar, and I was like, ‘Yes, that’s fucking perfect.’” Alana Haim: “I think there were parts of that song where we were feeling sexy. I remember I had gone to go get food, and when I came back Danielle had written the bridge. She was like, ‘Look what I wrote!’ And I was like, ‘Oh! Okay!’” **3 AM** Alana: “It’s pretty self-explanatory—it’s about a booty call. There have been around 10 versions of this song. Someone was having a booty call. It was probably me, to be honest. We started out with this beat, and then we wrote the chorus super quickly. But then we couldn’t figure out what to do in the verses. We’d almost given up on it and then we were like, ‘Let’s just try one last time and see if we can get there.’ I think it was close to 3 am when we figured out the verse and we had this idea of having it introduced by a phone call. Because it *is* about a booty call. And we had to audition a bunch of dudes. We basically got all of our friends that were guys to be like, ‘Hey, this is so crazy, but can you just pretend to be calling a girl at 3 am?’ We got five or six of our friends to do it, and they were so nervous and sheepish. They were the worst! I was like, ‘Do you guys even talk to girls?’ I think you can hear the amount of joy and laughs we had making this song.” **Don’t Wanna** Alana: “I think this is classic HAIM. It was one of the earlier songs which we wrote around the same time as ‘Now I’m in It.’ We always really, really loved this song, and it always kind of stuck its head out like, ‘Hey, remember me?’ It just sounded so good being simple. We can tinker around with a song for years, and with this one, every time we added something or changed it, it lost the feeling. And every time we played it, it just kind of felt good. It felt like a warm sweater.” **Another Try** Alana: “I\'ve always wanted to write a song like this, and this is my favorite on the record. The day that we started it, I was thinking that I was going to get back together with the love of my life. I mean, now that I say that, I want to barf, because we\'re not in a good place now, but at that point we were. We had been on and off for almost 10 years and I thought we were going to give it another try. And it turns out, the week after we finished the song, he had gotten engaged. So the song took on a whole new meaning very quickly. It’s really about the fact I’ve always been on and off with the same person, and have only really had one love of my life. It’s kind of dedicated to him. I think Ariel had a lot of fun producing this song. As for the person it’s about? He doesn’t know about it, but I think he can connect the dots. I don’t think it’s going to be very hard to figure out. The end of the song is supposed to feel like a celebration. We wanted it to feel like a dance party. Because even though it has such a weird meaning now, the song has a hopeful message. Who knows? Maybe one day we’ll figure it out. I am still hopeful.” **Leaning on You** Alana: “This is really a song about finding someone that accepts your flaws. That’s such a rare thing in this world—to find someone you love that accepts you as who you are and doesn\'t want to change you. As sisters, we are the CEOs of our company: We have super strong personalities and really strong opinions. And finding someone that\'s okay with that, you would think would be celebrated, but it\'s actually not. It\'s really hard to find someone that accepts you and accepts what you do as a job and accepts everything about you. And I think ‘Leaning on You’ is about when you find that person that really uplifts you and finds everything that you do to be incredible and interesting and supports you. It’s a beautiful thing.” Danielle: “We wrote this song just us sitting around a guitar. And we just wanted to keep it like that, so we played acoustic guitar straight into the computer for a very dry, unique sound that I love.” **I’ve Been Down** Danielle: “This is the last one we wrote on the album. This was super quick with stream-of-consciousness lyrics. I wanted it to sound like you were in the room, like you were right next to me. That chorus—‘I’ve been down, I’ve been down’—feels good to sing. It\'s very therapeutic to just kind of scream it in song form. To me, it’s the most therapeutic thing I can do. The backing vocals on this are like the other side of your brain.” **Man From the Magazine** Este: \"When we were first coming out, I guess it was perplexing for some people that I would make faces when I played, even though men have been doing it for years. When they see men do it, they are just, to quote HAIM, ‘in it.’ But of course, when a woman does it, it\'s unsettling and off-putting and could be misconstrued as something else. We got asked questions about it early on, and there was this one interviewer who asked if I made the faces I made onstage in bed. Obviously he wasn’t asking about when I’m in bed yawning. My defense mechanism when stuff like that happens is just to try to make a joke out of it. So I kind of just threw it back at him and said, ‘Well, there\'s only one way to find out.’ And of course, there was a chuckle and then we moved on. Now, had someone said that to me, I probably would\'ve punched them in the face. But as women, we\'re taught kind of just to always be pleasant and be polite. And I think that was my way of being polite and nice. Thank god things are changing a bit. We\'ve been talking about shit like this forever, but I think now, finally, people are able to listen more intently.” Danielle: “We recorded this song in one take. We got the feeling we wanted in the first take. The first verse is Este\'s super specific story, and then, on the second verse, it feels very universal to any woman who plays music about going into a guitar store or a music shop and immediately either being asked, ‘Oh, do you want to start to play guitar?’ or ‘Are you looking for a guitar for your boyfriend?’ And you\'re like, ‘What the fuck?’ It\'s the worst feeling. And I\'ve talked to so many other women about the same experience. Everyone\'s like, ‘Yeah, it\'s the worst. I hate going in the guitar stores.’ It sucks.” **All That Ever Mattered** Alana: “This is one of the more experimental songs on the record. Whatever felt good on this track, we just put it in. And there’s a million ways you could take this song—it takes on a life of its own and it’s kind of chaotic. The production is bananas and bonkers, but it did really feel good.” Danielle: “It’s definitely a different palette. But to us it was exciting to have that crazy guitar solo and those drums. It also has a really fun scream on it, which I always like—it’s a nice release.” **FUBT** Alana: “This song was one of the ones that was really hard to write. It’s about being in an emotionally abusive relationship, which all three of us have been in. It’s really hard to see when you\'re in something like that. And the song basically explains what it feels like and just not knowing how to get out of it. You\'re just kind of drowning in this relationship, because the highs are high and the lows are extremely low. You’re blind to all these insane red flags because you’re so immersed in this love. And knowing that you\'re so hard on yourself about the littlest things. But your partner can do no wrong. When we wrote this song, we didn’t really know where to put it. But it felt like the end to the chapter of the record—a good break before the next songs, which everyone knew.” **Now I’m in It** Danielle: “This song is about feeling like you\'re in something and almost feeling okay to sit in it, but also just recognizing that you\'re in a dark place. I was definitely in a dark place, and it was just like I had to look at myself in the mirror and be like, ‘Yeah, this is fucked up. And you need to get your shit together and you need to look it in the face and know that you\'re here and work on yourself.’ After writing this song I got a therapist, which really helped me.” **Hallelujah** Alana: “This song really did just come from wanting to express how important it is to have the love of your family. We\'re very lucky that we each have two sisters as backup always. We wrote this with our friend Tobias Jesso Jr., and we all just decided to write verses separately, which is rare for us. I think we each wanted to have our own take on the lyric ‘Why me, how\'d I get this hallelujah’ and what it meant to each of us. I wrote about losing a really close friend of mine at such a young age and going through a tragedy that was unexplainable. I still grapple with the meaning of that whole thing. It was one of the hardest times in my life, and it still is, but I was really lucky that I had two siblings that were really supportive during that time and really helped me get through it. If you talk to anybody that loses someone unexpectedly, you really do become a different person. I feel like I\'ve had two chapters of my life at this point: before it happened and after it happened. And I’ve always wanted to thank my sisters at the same time because they were so integral in my healing process going through something so tragic.” **Summer Girl** Alana: This song is collectively like our baby. Putting it out was really fun, but it was also really scary, because we were coming back and we didn’t know how people were going to receive it. We’d played it to people and a lot of them didn’t really like it. But we loved everything about it. You can lose your confidence really quickly, but thankfully, people really liked it. Putting out this song really did give us back our confidence.” Danielle: “I\'ve talked about it a lot, but this song is about my boyfriend getting cancer a couple of years ago, and it was truly the scariest thing that I have ever been through. I just couldn\'t stop thinking about how he was feeling. I get spooked really easily, but I felt like I had to buck the fuck up and be this kind of strong figure for him. I had to be this kind of sunshine, which was hard for me, but I feel like it really helped him. And that’s kind of where this song came from. Being the summer when he was just in this dark, dark place.”

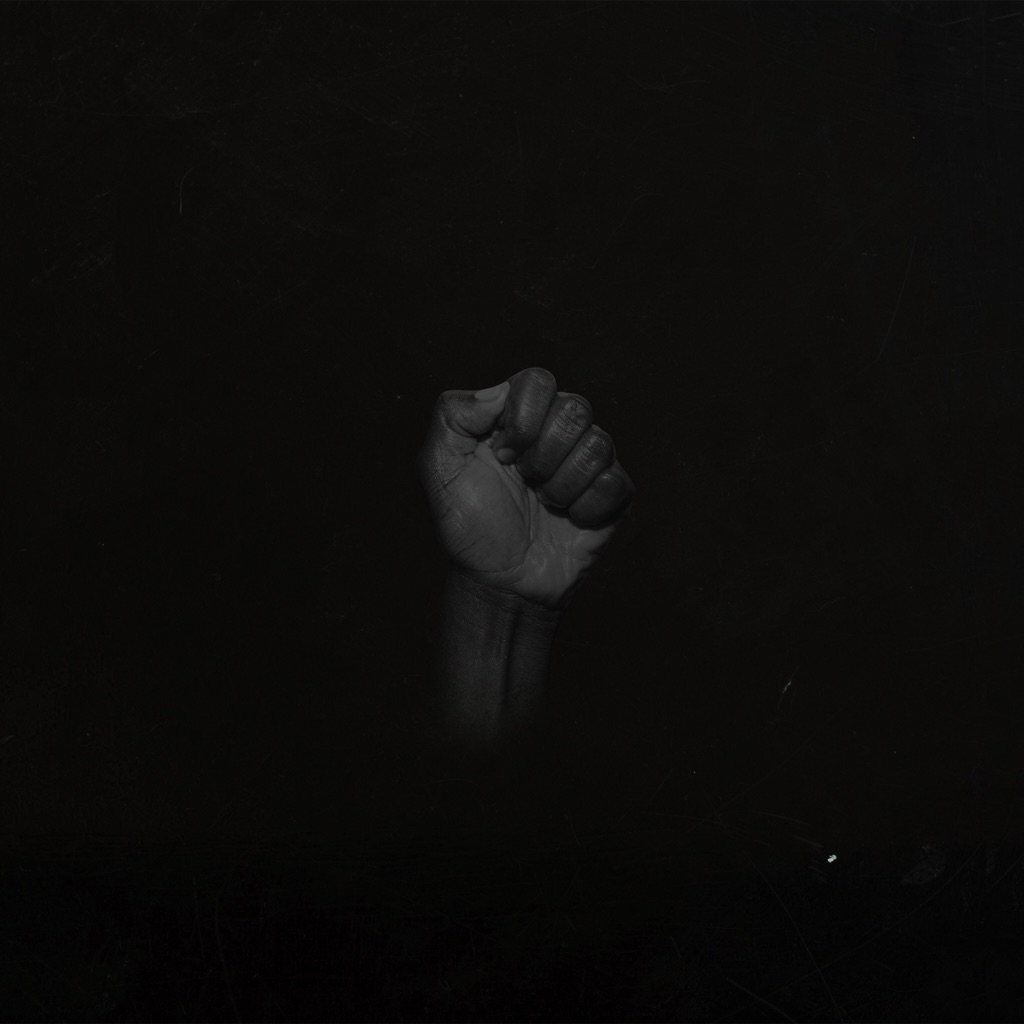

“I was fresh from a war but it was internal/Every day I encounter another hurdle,” J Hus spits as he closes *Big Conspiracy* on the piano-led “Deeper Than Rap”. That war, and the highs and lows of Momodou Jallow’s life, make for a mesmerising second album. Lyrics address his incarceration, street life, God, violence, his African roots and colonialism. From others those themes would feel heavy, but delivered in J Hus’ effortless voice, with a flow that switches frequently, they stun. The references are playful, too—Mick Jagger and Woody Woodpecker are mentioned on “Fortune Teller” and Destiny’s Child get a recurrent role in the standout “Fight for Your Right”. Hus is backed by inventive instrumentation encompassing delicate strings, Afrobeats, reggae and hip-hop and nods to garage and Dr. Dre’s work with 50 Cent, while Koffee and Burna Boy contribute to the celebratory feel on “Repeat” and “Play Play”. This is a record as diverse, smart and vibrant as anything coming from the UK right now.

A mere 11 months passed between the release of *Lover* and its surprise follow-up, but it feels like a lifetime. Written and recorded remotely during the first few months of the global pandemic, *folklore* finds the 30-year-old singer-songwriter teaming up with The National’s Aaron Dessner and longtime collaborator Jack Antonoff for a set of ruminative and relatively lo-fi bedroom pop that’s worlds away from its predecessor. When Swift opens “the 1”—a sly hybrid of plaintive piano and her naturally bouncy delivery—with “I’m doing good, I’m on some new shit,” you’d be forgiven for thinking it was another update from quarantine, or a comment on her broadening sensibilities. But Swift’s channeled her considerable energies into writing songs here that double as short stories and character studies, from Proustian flashbacks (“cardigan,” which bears shades of Lana Del Rey) to outcast widows (“the last great american dynasty”) and doomed relationships (“exile,” a heavy-hearted duet with Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon). It’s a work of great texture and imagination. “Your braids like a pattern/Love you to the moon and to Saturn,” she sings on “seven,” the tale of two friends plotting an escape. “Passed down like folk songs, the love lasts so long.” For a songwriter who has mined such rich detail from a life lived largely in public, it only makes sense that she’d eventually find inspiration in isolation.

Since her days fronting Moloko beginning in the mid-’90s, Róisín Murphy has been dancing around the edges of the club, and occasionally—for instance, on the 2012 single “Simulation” or 2015’s “Jealousy”—she has waded into the thick of the dance floor. But on *Róisín Machine*, the Irish singer-songwriter declares her unconditional love for the discotheque. Working with her longtime collaborator DJ Parrot—a Sheffield producer who once recorded primitive house music alongside Cabaret Voltaire’s Richard H. Kirk in the duo Sweet Exorcist—she summons a sound that is both classic and expansive, swirling together diverse styles and eras into an enveloping embrace of a groove. “We Got Together” invokes 1988’s Second Summer of Love in its bluesy, raving-in-a-muddy-field stomp; “Shellfish Mademoiselle” sneaks a squirrelly acid bassline under cover of Hammond-kissed R&B; “Kingdom of Ends” is part Pink Floyd, part “French Kiss.” The crisply stepping funk of “Incapable”—a dead ringer for classic Matthew Herbert, another of her onetime collaborators—is as timeless as house music gets. So are the pumping “Simulation” and “Jealousy,” which bookend the album, and which haven’t aged a day since they first burned up nightclubs as white-label 12-inches.

The harmonies that Chloe and Halle Bailey conjure sound like heaven. It\'s what got them tens of millions of views on YouTube; it\'s what eventually attracted Beyoncé\'s attention; and it\'s what continues to make them a force on their second album, *Ungodly Hour*. The duo experiments with a multitude of sounds and textures—many of their own making—while keeping their voices centered and striking as ever. Where their 2018 debut *The Kids Are Alright* played up an almost angelism that connected that moment to their origins as child stars, this new project is about maturation—both musically and otherwise. “I feel like we were more sure of ourselves, more sure of our messaging and what we wanted to get across in just showing that it\'s okay to have flaws and insecurities and show all the layers of what makes you beautiful,” Halle tells Apple Music. “I feel like we\'ve come a long way and in our growth as young women, and you\'d definitely be able to hear that in the music.” This time around, they\'re owning their sexuality and, along with it, the messiness that comes with being an adult and trying to figure out your place. On its face, *Ungodly Hour* is an uplifting album, but it doesn\'t shy away from the darker feelings that come along the way. “A lot of the world sees us as like little perfect angels, and we want to show the different layers of us,” Chloe says. “We\'re not perfect. We\'re growing into grown women, and we wanted to show all of that.” Here the sisters break down each song on their second album. **Intro** Halle: “This intro was made after we had finished making ‘Forgive Me.’ We thought about how we wanted to open this album, because our musicianship and musical integrity is always super-duper important to us, and we never want to lose the essence of who we are in trying to also make some songs that are a bit more mainstream. It felt like us being us completely and just drowning everyone in harmonies like we love to and just playing around. That was our time to play and to open the album with something that will make people\'s ears perk up as well as allow us to have so much fun creatively.” Chloe: “And the reason why we wanted to say the phrase ‘Don\'t ask for permission, ask for forgiveness’ is because that was a statement that wrapped and concluded the whole album. We should never have to apologize for being ourselves. You should never apologize for who you are or any of your imperfections, and you don\'t need to get permission from the world to be yourself.” **Forgive Me** Chloe: “I love it because it\'s so badass, and it\'s taking your power back and not feeling like your self-worth is in the trash. I remember we were all in the studio with \[songwriter\] Nija \[Charles\] and \[producer\] Sounwave, and for me personally, I was going through a situation where I was dealing with a guy and he picked someone else over me, and it really bothered me because I felt like it wasn\'t done in the most honest light. I like to be told things up front. And so when we were all in the session, this had just happened to me. I went in the booth and laid down some melodies, and some of the words came in, and then Halle went in and she sang ‘forgive me,’ and I thought that was so strong and powerful, and Nija laid down some melodies. We kind of constructed it as a puzzle in a way. It felt so good—it felt like we were taking our power back, like, ‘Forgive me for not caring and giving you that energy to control me and make me sad.’” **Baby Girl** Halle: “‘Baby Girl’ is a girl empowerment song, but our perspective when we were writing the song, personally, for me, it was a message that I needed to remind myself of. I remember we wrote this song in Malibu. We decided for the day after Christmas, we wanted to rent an Airbnb, and we wanted to just go out there with no parents and be by the beach and bring our gear and just create. And I remember at that time I was just feeling a little bit down, and I just needed that pick-me-up. So I started writing these lyrics about how I was feeling, how everybody makes it looks so easy and how everything that you see—it seems real, but is it really? So that was definitely an encouraging, empowering song that we wanted other girls to relate to and play when they needed that messaging—when you\'re feeling overwhelmed and insecure and you\'re just like, \'Okay, what\'s next?\' Like, nope, snap out of it. You\'re amazing.” **Do It** Chloe: “We just love the energy of that record. It feels so lighthearted and fun but simple and complex at the same time. We worked with Victoria Monét and Scott Storch on this one, and when we were creating it, we were just vibing out and feeling good. Our intention whenever we create is never to make that hit song or that single, because whenever you kind of go into that mindset, that\'s when you kind of stifle your creativity, and there\'s really nowhere to go. So we were just all having fun and vibing out, and we were just going to throw whatever to the wall and see what sticks. After we created the song, about two weeks later, we were listening to it and we were like, \'Uh-oh, we\'re really kind of feeling this. It feels really, really good.\' And we decided that that would be one that we would shoot a video to, and it just kind of made a life of its own. I\'m always happy when our music is well received, and it just makes us happy also seeing people online dancing to it and doing the dance we did in the music video. It\'s really exceeding all of our expectations.” **Tipsy** Halle: “‘Tipsy’ was such a fun record to write. My beautiful sister did this amazing production that just brought it to a whole nother level. I remember when we were first starting out the song, I was playing like these sort of country-sounding guitar chords that kind of had a little cool swing to it, and then we just started writing. We were thinking about when we\'re so in love, how our hearts are just open and how the other person in the relationship really has the power to break your heart. They have that power, and you\'re open and you\'re hoping nothing goes wrong. It\'s kind of like a warning to them: If you break my heart, if you don\'t do what you\'re supposed to do, yes, I will go after you, and yes, this will happen. Of course it\'s an exaggeration—we would never actually kill somebody over that. But we just wanted to voice how it\'s very important to take care of our hearts and that when we give a piece of ourselves, we want them to give a piece of themselves as well. It\'s a playful song, so we think a lot of people will have fun with that one.” **Ungodly Hour** Chloe: “I believe it was Christmas of 2018, and we knew that we wanted to start on this album. With anything, we\'re very visual, so we got a bunch of magazines, and we got like three posters we duct-taped together, and we made our mood board. There was a phrase that we found in a magazine that said \'the trouble with angels\' that really stuck out with us. We put that on the board, and we put a lot of women on there who didn\'t really have many clothes on because we wanted this album to express our sexuality. Halle\'s 20, I\'m 22. We just wanted to show that we can own our sexuality in a beautiful way as young women and it\'s okay to own that. So fast-forward a few months, and we were in the session with Disclosure. Whenever my sister and I create lyrics, sometimes we\'re inspired randomly on the day and we\'ll hear a phrase or something. I forgot what I was doing or what I was watching, but I heard the phrase \'ungodly hour\' and I wrote it in my notes really quick. So when we were all in a session together, we were putting our minds together, like, what can we say with that? And we came up with the phrase \'Love me at the ungodly hour.\' Love me at my worst. Love me when I\'m not the best version of myself. And the song kind of wrote itself really fast. It\'s about being in a situationship with someone who isn\'t ready to fully commit or settle down with you, but the connection is there, the chemistry is there, it\'s so electric. But being the woman, you know your self-worth and you know what you won\'t accept. So it\'s like, if you want all of me, then you need to come correct. And I love how simple and groovy the beat feels, and how the vocals kind of just rock on top of it. It feels so vibey.” **Busy Boy** Halle: “So ‘Busy Boy’ is another very playful love song. The inspiration for it basically came from our experiences, kiki-ing with our girls, when we have those moments where we\'re all gossiping and talking about what\'s going on in our lives. This one dude comes up, and we all know him because he is so fine and he\'s tried to holler at all of us. It was such a fun story to ride off of, because we have had those moments where—\'cause we\'re friends with a lot of beautiful black girls, and we\'re all doing our thing, and the same guy who is really successful or cute will hop around trying to get at each of us. So that was really funny to talk about, and also to talk about the bonding of sisterhood, of just saying all this stuff about this guy to make ourselves feel better. I mean, because at the end of the day, we have to remind ourselves that even though you may be cute, even though you may be trying to get my attention, I know that you\'re just a busy boy, and I\'m going to keep it moving.” **Overwhelmed** Chloe: “Halle and I really wanted to have interludes on this album, and we were kind of going through all of the projects and files that were on my hard drive listening on our speakers in our studio. This came up and we were like, wow. The lyrics really resonated with us, and we forgot we even wrote it. We went and reopened the project and laid down so many more harmonies on top of it. We just wanted it to kind of feel like that breath in the album, because there\'s so many times when you feel overwhelmed and sometimes you\'re even scared to admit it because you don\'t want to come off as weak or seeming like you can\'t do something, but we\'re all human. There have been so many times when Halle and I feel overwhelmed, and I\'ll play this song and feel so much better. It\'s okay to just lay in that and not feel pressured to know what\'s next and just kind of accept, and once you accept it, then you could start moving forward and planning ahead. But we all have those moments where we kind of just need to admit it and just live in it.” **Lonely** Halle: “This song is so very important to us. We did this with Scott Storch, and it ended up just kind of writing itself. I think one friend that we had in particular was kind of going through something in their life, and sometimes, a lot of the situations that we\'re around we take inspiration from to write about. We were also feeling just stuck in a way, and we wanted to write something that would uplift whoever it was out there who felt the same way we did, whether it was just being lonely and knowing that it\'s okay to be alone. And when you are alone, owning how beautiful you are and knowing that it\'s okay to be by yourself. We kind of just wrote the story that way, thinking about us alone in our apartment and what we do, what we think when we\'re in our room, and what they think when they go home. I mean, what is everybody thinking about in all of this? When people are waiting by the phone, waiting for somebody to call them, and the call never comes—you don\'t have to let that discourage you. At the end of the day, you are a beautiful soul inside and out, and as long as you\'re okay with loving yourself wholeheartedly, then you can be whoever you want to be, and you can thrive.” **Don\'t Make It Harder on Me** Chloe: “We wrote this with our good friend Nasri and this amazing producer Gitty, and we were all in the studio, and I believe Halle really inspired this song. She was going through a situation where she was involved with someone, and there was also someone else trying to get her attention, and we kind of just painted that story through the lyrics: You\'re in this wonderful relationship, but there\'s this guy who just keeps getting your attention, and you don\'t want to be tempted, you want to be faithful. And it\'s like, \'Look, you had your chance with me. Don\'t come around now that I\'m taken. Don\'t make it harder on me.\' I love it because it feels so old-school. We wanted the background to feel so nostalgic. Afterwards, we added actual strings on the record. It just feels so good—every time I listen to it, I just feel really light and free and happy.” **Wonder What She Thinks of Me** Halle: “I was really inspired for this song because of a story that was kind of happening in my life. I mean, the themes of \'Don\'t Make It Harder on Me\' and this song as well are kind of hand in hand. There was this amazing guy who\'s so sweet, and it just talks about this bond that you have with somebody and how this person came out of nowhere. And then all of a sudden, you kind of find yourself wanting that person, but they\'re in a situation and you\'re in a situation, and you don\'t want to seem like you\'re trying to take this girl\'s man. We spun it into this story of being the other woman—even though, just so you know, Chloe and I were never that. So we pushed that story so far, and it was really fun and exciting to talk about, because I don\'t think we had ever experienced or heard another song that was talking about the perspective of the other woman—the woman who is on the side or the girl who wishes so badly that she could be with him and is always there for him. So we flipped it into this drama-filled song, which we really feel like it\'s so exciting and so adventurous. The melodies and the lyrics and the beautiful production my sister did, it just really turned out amazing.” **ROYL** Chloe: “I love \'Rest of Your Life\' because it kind of feels like an ode to our debut album, *The Kids Are Alright*, with the anthemic backgrounds and feeling so youthful and grungy. With this song, we just wanted to wrap this album up by saying, \'It doesn\'t matter what mistakes you make, just live your life, go for it, have fun. You don\'t know when your time to leave this earth is, so just live out for the rest of your life.\' And even though we are in the ungodly hour right now, and we\'re learning ourselves through our mistakes and our imperfections, so what? That\'s what makes us who we are. Live it out.”

On his first LP of original songs in nearly a decade—and his first since reluctantly accepting Nobel Prize honors in 2016—Bob Dylan takes a long look back. *Rough and Rowdy Ways* is a hot bath of American sound and historical memory, the 79-year-old singer-songwriter reflecting on where we’ve been, how we got here, and how much time he has left. There are temperamental blues (“False Prophet,” “Crossing the Rubicon”) and gentle hymns (“I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You”), rollicking farewells (“Goodbye Jimmy Reed”) and heady exchanges with the Grim Reaper (“Black Rider”). It reads like memoir, but you know he’d claim it’s fiction. And yet, maybe it’s the timing—coming out in June 2020 amidst the throes of a pandemic and a social uprising that bears echoes of the 1960s—or his age, but Dylan’s every line here does have the added charge of what feels like a final word, like some ancient wisdom worth decoding and preserving before it’s too late. “Mother of Muses” invokes Elvis and MLK, Dylan claiming, “I’ve already outlived my life by far.” On the 16-minute masterstroke and stand-alone single “Murder Most Foul,” he draws Nazca Lines around the 1963 assassination of JFK—the death of a president, a symbol, an era, and something more difficult to define. It’s “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” that lingers longest, though: Over nine minutes of accordion and electric guitar mingling like light on calm waters, Dylan tells the story of an outlaw cycling through radio stations as he makes his way to the end of U.S. Route 1, the end of the road. “Key West is the place to be, if you’re looking for your mortality,” he says, in a growl that gives way to a croon. “Key West is paradise divine.”