Still Listening's Top 50 Albums Of 2023

The moment is here. Unveiling our favourite records from 2023.

Source

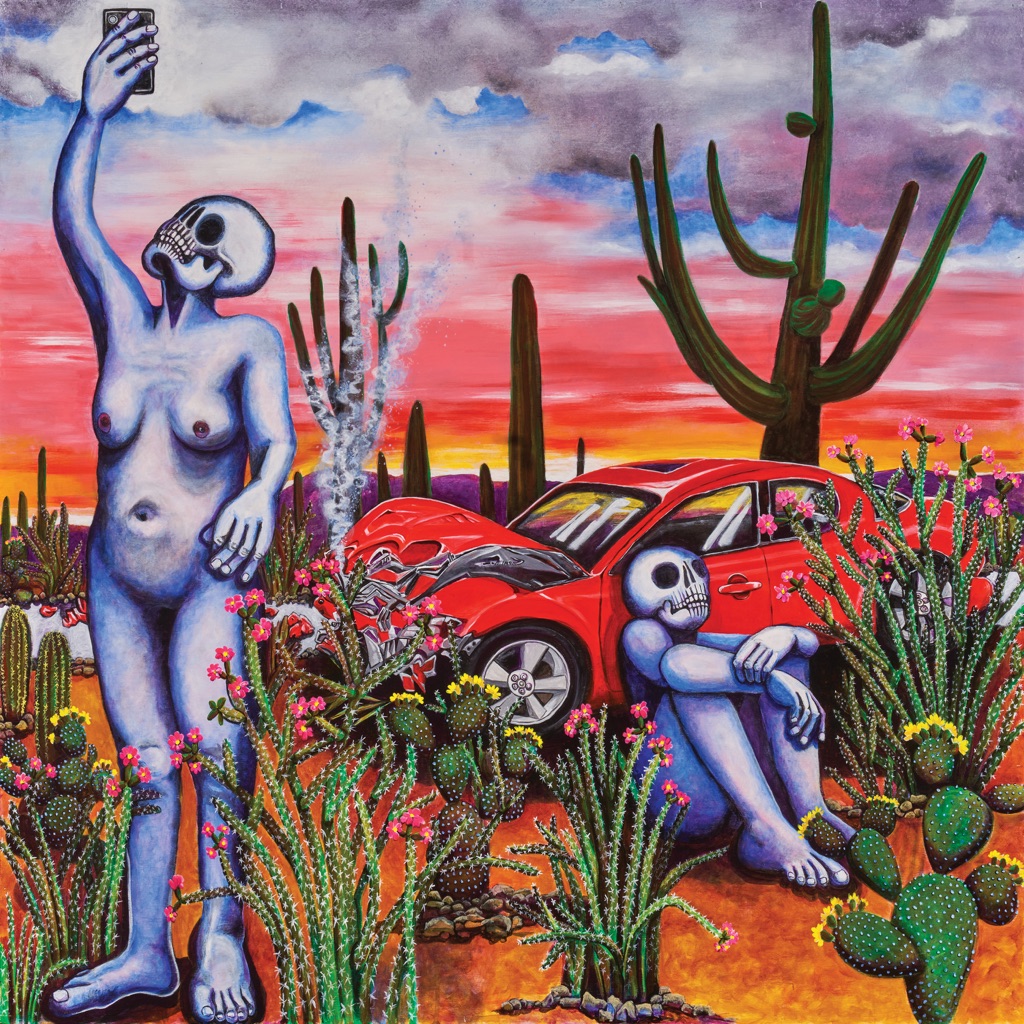

Part of what makes Danny Brown and JPEGMAFIA such a natural pair is that they stick out in similar ways. They’re too weird for the mainstream but too confrontational for the subtle or self-consciously progressive set. And while neither of them would be mistaken for traditionalists, the sample-scrambling chaos of tracks like “Burfict!” and “Shut Yo Bitch Ass Up/Muddy Waters” situate them in a lineage of Black music that runs through the comedic ultraviolence of the Wu-Tang Clan back through the Bomb Squad to Funkadelic, who proved just because you were trippy didn’t mean you couldn’t be militant, too.

For the last two decades, Sufjan Stevens’ music has taken on two distinct forms. On one end, you have the ornate, orchestral, and positively stuffed style that he’s excelled at since the conceptual fantasias of 2003’s star-making *Michigan*. On the other, there’s the sparse and close-to-the-bone narrative folk-pop songwriting that’s marked some of his most well-known singles and albums, first fully realized on the stark and revelatory *Seven Swans* from 2004. His 10th studio full-length, *Javelin*, represents the fullest and richest merging of those two approaches that Stevens has achieved to date. Even as it’s been billed as his first proper “songwriter’s album” since 2015’s autobiographical and devastating *Carrie & Lowell*, *Javelin* is a kaleidoscopic distillation of everything Stevens has achieved in his career so far, resulting in some of the most emotionally affecting and grandiose-sounding music he’s ever made. *Javelin* is Stevens’ first solo record of vocal-based music since 2020’s *The Ascension*, and it’s relatively straightforward compared to its predecessor’s complexity. Featuring contributions from vocalists and frequent collaborators like Nedelle Torrisi, adrienne maree brown, Hannah Cohen, and The National’s Bryce Dessner (who adds his guitar skills to the heart-bursting epic “Shit Talk”), the record certainly sounds like a full-group effort in opposition to the angsty isolation that streaked *The Ascension*. But at the heart of *Javelin* is Stevens’ vocals, the intimacy of which makes listeners feel as if they’re mere feet away from him. There’s callbacks to Stevens’ discography throughout, from the *Age of Adz*-esque digital dissolve that closes out “Genuflecting Ghost” to the rustic Flannery O’Connor evocations of “Everything That Rises,” recalling *Seven Swans*’ inspirational cues from the late fiction writer. Ultimately, though, *Javelin* finds Stevens emerging from the depressive cloud of *The Ascension* armed with pleas for peace and a distinct yearning to belong and be embraced—powerful messages delivered on high, from one of the 21st century’s most empathetic songwriters.

A Wednesday song is a quilt. A short story collection, a half-memory, a patchwork of portraits of the American south, disparate moments that somehow make sense as a whole. Karly Hartzman, the songwriter/vocalist/guitarist at the helm of the project, is a story collector as much as she is a storyteller: a scholar of people and one-liners. Rat Saw God, the Asheville quintet’s new and best record, is ekphrastic but autobiographical and above all, deeply empathetic. Across the album’s ten tracks Hartzman, guitarist MJ Lenderman, bassist Margo Shultz, drummer Alan Miller, and lap/pedal steel player Xandy Chelmis build a shrine to minutiae. Half-funny, half-tragic dispatches from North Carolina unfurling somewhere between the wailing skuzz of Nineties shoegaze and classic country twang, that distorted lap steel and Hartzman’s voice slicing through the din. Rat Saw God is an album about riding a bike down a suburban stretch in Greensboro while listening to My Bloody Valentine for the first time on an iPod Nano, past a creek that runs through the neighborhood riddled with broken glass bottles and condoms, a front yard filled with broken and rusted car parts, a lonely and dilapidated house reclaimed by kudzu. Four Lokos and rodeo clowns and a kid who burns down a corn field. Roadside monuments, church marquees, poppers and vodka in a plastic water bottle, the shit you get away with at Jewish summer camp, strange sentimental family heirlooms at the thrift stores. The way the South hums alive all night in the summers and into fall, the sound of high school football games, the halo effect from the lights polluting the darkness. It’s not really bright enough to see in front of you, but in that stretch of inky void – somehow – you see everything. Rat Saw God was written in the months immediately following Twin Plagues’ completion, and recorded in a week at Asheville’s Drop of Sun studio. While Twin Plagues was a breakthrough release critically for Wednesday, it was also a creative and personal breakthrough for Hartzman. The lauded record charts feeling really fucked up, trauma, dropping acid. It had Hartzman thinking about the listener, about her mom hearing those songs, about how it feels to really spill your guts. And in the end, it felt okay. “I really jumped that hurdle with Twin Plagues where I was not worrying at all really about being vulnerable – I was finally comfortable with it, and I really wanna stay in that zone.” The album opener, “Hot Rotten Grass Smell,” happens in a flash: an explosive and wailing wall-of-sound dissonance that’d sound at home on any ‘90s shoegaze album, then peters out into a chirping chorus of peepers, a nighttime sound. And then into the previously-released eight-and-half-minute sprawling, heavy single, “Bull Believer.” Other tracks, like the creeping “What’s So Funny” or “Turkey Vultures,” interrogate Hartzman’s interiority - intimate portraits of coping, of helplessness. “Chosen to Deserve” is a true-blue love song complete with ripping guitar riffs, skewing classic country. “Bath County” recounts a trip Hartzman and her partner took to Dollywood, and time spent in the actual Bath County, Virginia, where she wrote the song while visiting, sitting on a front porch. And Rat Saw God closer “TV in the Gas Pump” is a proper traveling road song, written from one long ongoing iPhone note Hartzman kept while in the van, its final moments of audio a wink toward Twin Plagues. The reference-heavy stand-out “Quarry” is maybe the most obvious example of the way Hartzman seamlessly weaves together all these throughlines. It draws from imagery in Lynda Barry’s Cruddy; a collection of stories from Hartzman’s family (her dad burned down that cornfield); her current neighbors; and the West Virginia street from where her grandma lived, right next to a rock quarry, where the explosions would occasionally rock the neighborhood and everyone would just go on as normal. The songs on Rat Saw God don’t recount epics, just the everyday. They’re true, they’re real life, blurry and chaotic and strange – which is in-line with Hartzman’s own ethos: “Everyone’s story is worthy,” she says, plainly. “Literally every life story is worth writing down, because people are so fascinating.” But the thing about Rat Saw God - and about any Wednesday song, really - is you don’t necessarily even need all the references to get it, the weirdly specific elation of a song that really hits. Yeah, it’s all in the details – how fucked up you got or get, how you break a heart, how you fall in love, how you make yourself and others feel seen – but it’s mostly the way those tiny moments add up into a song or album or a person.

“You can feel a lot of motion and energy,” Caroline Polachek tells Apple Music of her second solo studio album. “And chaos. I definitely leaned into that chaos.” Written and recorded during a pandemic and in stolen moments while Polachek toured with Dua Lipa in 2022, *Desire, I Want to Turn Into You* is Polachek’s self-described “maximalist” album, and it weaponizes everything in her kaleidoscopic arsenal. “I set out with an interest in making a more uptempo record,” she says. “Songs like ‘Bunny Is a Rider,’ ‘Welcome to My Island,’ and ‘Smoke’ came onto the plate first and felt more hot-blooded and urgent than anything I’d done before. But of course, life happened, the pandemic happened, I evolved as a person, and I can’t really deny that a lunar, wistful side of my writing can never be kept out of the house. So it ended up being quite a wide constellation of songs.” Polachek cites artists including Massive Attack, SOPHIE, Donna Lewis, Enya, Madonna, The Beach Boys, Timbaland, Suzanne Vega, Ennio Morricone, and Matia Bazar as inspirations, but this broad church only really hints at *Desire…*’s palette. Across its 12 songs we get trip-hop, bagpipes, Spanish guitars, psychedelic folk, ’60s reverb, spoken word, breakbeats, a children’s choir, and actual Dido—all anchored by Polachek’s unteachable way around a hook and disregard for low-hanging pop hits. This is imperial-era Caroline Polachek. “The album’s medium is feeling,” she says. “It’s about character and movement and dynamics, while dealing with catharsis and vitality. It refuses literal interpretation on purpose.” Read on for Polachek’s track-by-track guide. **“Welcome to My Island”** “‘Welcome to My Island’ was the first song written on this album. And it definitely sets the tone. The opening, which is this minute-long non-lyrical wail, came out of a feeling of a frustration with the tidiness of lyrics and wanting to just express something kind of more primal and urgent. The song is also very funny. We snap right down from that Tarzan moment down to this bitchy, bratty spoken verse that really becomes the main personality of this song. It’s really about ego at its core—about being trapped in your own head and forcing everyone else in there with you, rather than capitulating or compromising. In that sense, it\'s both commanding and totally pathetic. The bridge addresses my father \[James Polachek died in 2020 from COVID-19\], who never really approved of my music. He wanted me to be making stuff that was more political, intellectual, and radical. But also, at the same time, he wasn’t good at living his own life. The song establishes that there is a recognition of my own stupidity and flaws on this album, that it’s funny and also that we\'re not holding back at all—we’re going in at a hundred percent.” **“Pretty in Possible”** “If ‘Welcome to My Island’ is the insane overture, ‘Pretty in Possible’ finds me at street level, just daydreaming. I wanted to do something with as little structure as possible where you just enter a song vocally and just flow and there\'s no discernible verses or choruses. It’s actually a surprisingly difficult memo to stick to because it\'s so easy to get into these little patterns and want to bring them back. I managed to refuse the repetition of stuff—except for, of course, the opening vocals, which are a nod to Suzanne Vega, definitely. It’s my favorite song on the album, mostly because I got to be so free inside of it. It’s a very simple song, outside a beautiful string section inspired by Massive Attack’s ‘Unfinished Sympathy.’ Those dark, dense strings give this song a sadness and depth that come out of nowhere. These orchestral swells at the end of songs became a compositional motif on the album.” **“Bunny Is a Rider”** “A spicy little summer song about being unavailable, which includes my favorite bassline of the album—this quite minimal funk bassline. Structurally on this one, I really wanted it to flow without people having a sense of the traditional dynamics between verses and choruses. Timbaland was a massive influence on that song—especially around how the beat essentially doesn\'t change the whole song. You just enter it and flow. ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ was a set of words that just flowed out without me thinking too much about it. And the next thing I know, we made ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ thongs. I love getting occasional Instagram tags of people in their ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ thongs. An endless source of happiness for me.” **“Sunset”** “This was a song I began writing with Sega Bodega in 2020. It sounded completely nothing like the others. It had a folk feel, it was gypsy Spanish, Italian, Greek feel to it. It completely made me look at the album differently—and start to see a visual world for them that was a bit more folk, but living very much in the swirl of city life, having this connection to a secret, underground level of antiquity and the universalities of art. It was written right around a month or two after Ennio Morricone passed away, so I\'d been thinking a lot about this epic tone of his work, and about how sunsets are the biggest film clichés in spaghetti westerns. We were laughing about how it felt really flamenco and Spanish—not knowing that a few months later, I was going to find myself kicked out of the UK because I\'d overstayed my visa without realizing it, and so I moved my sessions with Sega to Barcelona. It felt like the song had been a bit of a premonition that that chapter-writing was going to happen. We ended up getting this incredible Spanish guitarist, Marc Lopez, to play the part.” **“Crude Drawing of an Angel”** “‘Crude Drawing of an Angel’ was born, in some ways, out of me thinking about jokingly having invented the word ‘scorny’—which is scary and horny at the same time. I have a playlist of scorny music that I\'m still working on and I realized that it was a tone that I\'d never actually explored. I was also reading John Berger\'s book on drawing \[2005’s *Berger on Drawing*\] and thinking about trace-leaving as a form of drawing, and as an extremely beautiful way of looking at sensuality. This song is set in a hotel room in which the word ‘drawing’ takes on six different meanings. It imagines watching someone wake up, not realizing they\'re being observed, whilst drawing them, knowing that\'s probably the last time you\'re going to see them.” **“I Believe”** “‘I Believe’ is a real dedication to a tone. I was in Italy midway through the pandemic and heard this song called ‘Ti Sento’ by Matia Bazar at a house party that blew my mind. It was the way she was singing that blew me away—that she was pushing her voice absolutely to the limit, and underneath were these incredible key changes where every chorus would completely catch you off guard. But she would kind of propel herself right through the center of it. And it got me thinking about the archetype of the diva vocally—about how really it\'s very womanly that it’s a woman\'s voice and not a girl\'s voice. That there’s a sense of authority and a sense of passion and also an acknowledgment of either your power to heal or your power to destroy. At the same time, I was processing the loss of my friend SOPHIE and was thinking about her actually as a form of diva archetype; a lot of our shared taste in music, especially ’80s music, kind of lined up with a lot of those attitudes. So I wanted to dedicate these lyrics to her.” **“Fly to You” (feat. Grimes and Dido)** “A very simple song at its core. It\'s about this sense of resolution that can come with finally seeing someone after being separated from them for a while. And when a lot of misunderstanding and distrust can seep in with that distance, the kind of miraculous feeling of clearing that murk to find that sort of miraculous resolution and clarity. And so in this song, Grimes, Dido, and I kind of find our different version of that. But more so than anything literal, this song is really about beauty, I think, about all of us just leaning into this kind of euphoric, forward-flowing movement in our singing and flying over these crystalline tiny drum and bass breaks that are accompanied by these big Ibiza guitar solos and kind of Nintendo flutes, and finding this place where very detailed electronic music and very pure singing can meet in the middle. And I think it\'s something that, it\'s a kind of feeling that all of us have done different versions of in our music and now we get to together.” **“Blood and Butter”** “This was written as a bit of a challenge between me and Danny L Harle where we tried to contain an entire song to two chords, which of course we do fail at, but only just. It’s a pastoral, it\'s a psychedelic folk song. It imagines itself set in England in the summer, in June. It\'s also a love letter to a lot of the music I listened to growing up—these very trance-like, mantra-like songs, like Donna Lewis’ ‘I Love You Always Forever,’ a lot of Madonna’s *Ray of Light* album, Savage Garden—that really pulsing, tantric electronic music that has a quite sweet and folksy edge to it. The solo is played by a hugely talented and brilliant bagpipe player named Brighde Chaimbeul, whose album *The Reeling* I\'d found in 2022 and became quite obsessed with.” **“Hopedrunk Everasking”** “I couldn\'t really decide if this song needed to be about death or about being deeply, deeply in love. I then had this revelation around the idea of tunneling, this idea of retreating into the tunnel, which I think I feel sometimes when I\'m very deeply in love. The feeling of wanting to retreat from the rest of the world and block the whole rest of the world out just to be around someone and go into this place that only they and I know. And then simultaneously in my very few relationships with losing someone, I did feel some this sense of retreat, of someone going into their own body and away from the world. And the song feels so deeply primal to me. The melody and chords of it were written with Danny L Harle, ironically during the Dua Lipa tour—when I had never been in more of a pop atmosphere in my entire life.” **“Butterfly Net”** “‘Butterfly Net’ is maybe the most narrative storyteller moment on the whole album. And also, palette-wise, deviates from the more hybrid electronic palette that we\'ve been in to go fully into this 1960s drum reverb band atmosphere. I\'m playing an organ solo. I was listening to a lot of ’60s Italian music, and the way they use reverbs as a holder of the voice and space and very minimal arrangements to such incredible effect. It\'s set in three parts, which was somewhat inspired by this triptych of songs called ‘Chansons de Bilitis’ by Claude Debussy that I had learned to sing with my opera teacher. I really liked that structure of the finding someone falling in love, the deepening of it, and then the tragedy at the end. It uses the metaphor of the butterfly net to speak about the inability to keep memories, to keep love, to keep the feeling of someone\'s presence. The children\'s choir \[London\'s Trinity Choir\] we hear on ‘Billions’ comes in again—they get their beautiful feature at the end where their voices actually become the stand-in for the light of the world being onto me.” **“Smoke”** “It was, most importantly, the first song for the album written with a breakbeat, which inspired me to carry on down that path. It’s about catharsis. The opening line is about pretending that something isn\'t catastrophic when it obviously is. It\'s about denial. It\'s about pretending that the situation or your feelings for someone aren\'t tectonic, but of course they are. And then, of course, in the chorus, everything pours right out. But tonally it feels like I\'m at home base with ‘Smoke.’ It has links to songs like \[2019’s\] ‘Pang,’ which, for me, have this windswept feeling of being quite out of control, but are also very soulful and carried by the music. We\'re getting a much more nocturnal, clattery, chaotic picture.” **“Billions”** “‘Billions’ is last for all the same reasons that \'Welcome to My Island’ is first. It dissolves into total selflessness, whereas the album opens with total selfishness. The Beach Boys’ ‘Surf’s Up’ is one of my favorite songs of all time. I cannot listen to it without sobbing. But the nonlinear, spiritual, tumbling, open quality of that song was something that I wanted to bring into the song. But \'Billions\' is really about pure sensuality, about all agenda falling away and just the gorgeous sensuality of existing in this world that\'s so full of abundance, and so full of contradictions, humor, and eroticism. It’s a cheeky sailboat trip through all these feelings. You know that feeling of when you\'re driving a car to the beach, that first moment when you turn the corner and see the ocean spreading out in front of you? That\'s what I wanted the ending of this album to feel like: The song goes very quiet all of a sudden, and then you see the water and the children\'s choir comes in.”

With A Hammer is the debut studio album by New York singer-songwriter Yaeji. “With A Hammer” was composed across a two-year period in New York, Seoul, and London, begun shortly after the release of “What We Drew” and during the lockdowns of the Coronavirus pandemic. It is a diaristic ode to self-exploration; the feeling of confronting one’s own emotions, and the transformation that is possible when we’re brave enough to do so. In this case, Yaeji examines her relationship to anger. It is a departure from her previous work, blending elements of trip-hop and rock with her familiar house-influenced style, and dealing with darker, more self-reflective lyrical themes, both in English and Korean. Yaeji also utilizes live instrumentation for the first time on this album—weaving in a patchwork ensemble of live musicians, and incorporating her own guitar playing. “With A Hammer” features electronic producers and close collaborators K Wata and Enayet, and guest vocals from London’s Loraine James and Baltimore’s Nourished by Time.

ANOHNI’s music revolves around the strength found in vulnerability, whether it’s the naked trembling of her voice or the way her lyrics—“It’s my fault”; “Why am I alive?”; “You are an addict/Go ahead, hate yourself”—cut deeper the simpler they get. Her first album of new material with her band the Johnsons since 2010’s *Swanlights* sets aside the more experimental/electronic quality of 2016’s *HOPELESSNESS* for the tender avant-soul most listeners came to know her by. She mourns her friends (“Sliver of Ice”), mourns herself (“It’s My Fault”), and catalogs the seemingly limitless cruelty of humankind (“It Must Change”) with the quiet resolve of someone who knows that anger is fine but the true warriors are the ones who kneel down and open their hearts.

“I feel like I have a better sense of boundaries,” Tkay Maidza tells Apple Music. “I know what I do want to do and what I don\'t want to do. I stand up for myself a lot more, and when I go into the studio, I’m not questioning anything. I lost the sense of embarrassment.” The Zimbabwean Australian artist’s second LP comes seven years after her debut, *Tkay*, and two years after the final installment of her *Last Year Was Weird* EP trilogy. In those past couple years in particular, she recognized that she’d been giving too much attention to people who were holding her back. “Before I started making the album, I had this overarching feeling of being embarrassed or not doing the right thing all the time,” she says. Maidza struggled with motivation and faith in herself for a long period, until a series of co-writing sessions in LA in September 2022 saw her hit the accelerator. She found the confidence to listen to herself, to stop second-guessing, to take the high road. “It all just happened really quickly after a year and a half of being confused,” she says. “And I felt like I shouldn\'t question anything because it\'s been a while since I\'ve been on a hot streak like that. I\'m more confident in myself now. I\'m less scared. And even when I do question myself, it’s different now. It’s not because I\'m surrounded by people who constantly criticize me.” *Sweet Justice* is the sum total of that growth. It flows between hip-hop, house, and ’90s-inspired R&B, and features production from KAYTRANADA (“Our Way,” “Ghost!”) and Flume (“Silent Assassin,” which he also co-wrote). There are representations of the stages of grief Maidza encountered as she cleared her life of those holding her back—particularly anger and acceptance. Ultimately, though, it’s a proud acknowledgment of hard-won self-assurance; a wink and a middle finger up at everything and everyone quickly fading away in her rearview mirror. Below, she talks through key tracks on the album. **“Silent Assassin”** “I was letting go of a lot of people and while I was trying to separate myself from them, a lot of them were being really nosy, like, ‘You\'re not doing what you\'re supposed to be doing. What are you doing? You\'re supposed to be working.’ And little did they realize that I was working, it just didn\'t involve them. So this is basically me describing what I\'m actually up to and what they don\'t understand. I’m continuing my life without them, basically.” **“Ring-A-Ling”** “This was one of the first songs where I had a sense of finally healing, I was coming from an empowered place. Before, I was trying to figure out how to finish the song. I was sleeping a lot, I was procrastinating a lot, and the song was almost like my spirit saying, ‘Wake up, babes, it\'s time to get the money. There\'s business calling you.’ It’s my inner cheerleader telling me to wake up and get it, because time keeps moving with or without you, and the more you keep moving, the more you get results.” **“WUACV”** “I was letting go of the old people in my life and there was a sense of sadness, but then there came this feeling of anger. I remember a lot of people on Twitter were writing, \'Woke up and chose violence.’ That was such a meme, and I wrote it down as a song title. Then I heard this beat and it sounded like a riot. I wanted to make something that you could mosh to at a show, but it was kind of sneaky and smart in a way, like, be patient. You’re holding in the anger and then you let it go and that can contain it. It\'s like, ‘I\'m dangerous, don\'t try me. I could unleash, but I\'m choosing not to.’ And I think the healthiest way for me to channel that was in the music. Otherwise, I\'ll just be doing unproductive things.” **“Out of Luck”** “One of my focuses was to make smooth songs that also hit hard. You can listen to it in your lounge room or you can go to a party and it\'s banging. When I heard the instrumental for ‘Out of Luck,’ the energy just really embodied that mood board for what a Tkay album should sound like. I was in this powerful stage coming through grievance and acceptance where I almost felt sorry for everyone. I\'m like, ‘Damn, I\'m really about to start flying off. I\'m literally gone.’ And instead of thinking that I lost something, I think it\'s more powerful for girls to be like, ‘It was their loss.’” **“Won One”** “This one was really fun to do. I’m such a big fan of Aaliyah and Timbaland. So the mood board was around that inspiration, and also doubling down on the early-2000s idea by kind of interpolating USHER’s ‘U Remind Me,’ but flipping it to be from a girl\'s perspective. I really wanted to make songs that were about overcoming and reflecting, but not from a sad point of view. I think the lyrics are really honest—and I often feel that if you\'re able to speak about something, you\'ve moved on from it. So the fact that I could actually express how I felt in a way that I haven\'t before was a new sense of maturity and growth in terms of accepting my past and being okay with it.” **“What Ya Know”** “One of the things I really wanted to do on this album was to build on the universe of house music. I wanted to make at least three house songs. The other goal for this one was to create almost a girl group. It sounds like there\'s three people on the song. And to embody this empowering feeling, like you\'re walking through a club and everyone\'s looking at you, and they just don\'t know what it is that keeps them looking at you. You can tell they\'re kind of confused, and you’re okay with that. It\'s like, ‘I\'ve got a secret that you don\'t know about.’” **“Walking on Air”** “I really wanted a song that felt like that indie blog era, where they\'d pitch up vocals. The concept was about almost wanting to be in this state of blissful ignorance and being okay with it. I feel like I walk through life that way, with blind optimism, and I wanted to capture it in a song. And it kind of wraps the whole album up in a way—nothing really matters as long as I\'m sitting in this ‘ignorance is bliss’ state of mind and just being okay with not knowing what\'s going to happen.”

Post-humanism was a passion and a coping mechanism on yeule’s breakthrough album, 2022’s *Glitch Princess*, art-pop that escaped into the simulation and drew raw emotion from its artifice. Their third full-length finds the shape-shifting musician regaining their bearings as a human being, and trading short-circuiting electronica for the fuzzy sounds of shoegaze and ‘90s alt-rock. The effect is that of an AI yearning to be flesh and blood: “If only I could be/Real enough to love,” they sing over downcast guitar chords on “ghosts” as their voice glitches into decay. On the bleakly gorgeous “software update,” yeule fantasizes about a lover downloading their mind after their body is gone, over a swelling, reverberating wall of sound. There’s a tactile quality to the album’s digital processing reminiscent of ‘90s Warp Records staples like Boards of Canada or Aphex Twin, shot through with the melancholy that accompanies nostalgia for a time that’s long gone and barely remembered.

Whether as Fever Ray or with her brother Olof in The Knife, the Swedish electro-pop artist Karin Dreijer has always used alien-sounding music to evoke primitive human states. It isn’t just *Radical Romantics*’ metaphors that scan as sexual (the surrender of “Shiver,” the dominance-and-revenge fantasies of “Even It Out”); it’s the way their squishy synths and herky-jerky club beats conjure the messy ecstasy of our biological selves. And then there’s Dreijer’s voice, which through expert playacting and the miracle of modern technology creates a spectrum of characters, from temptress to horror-show to big daddy and little girl.

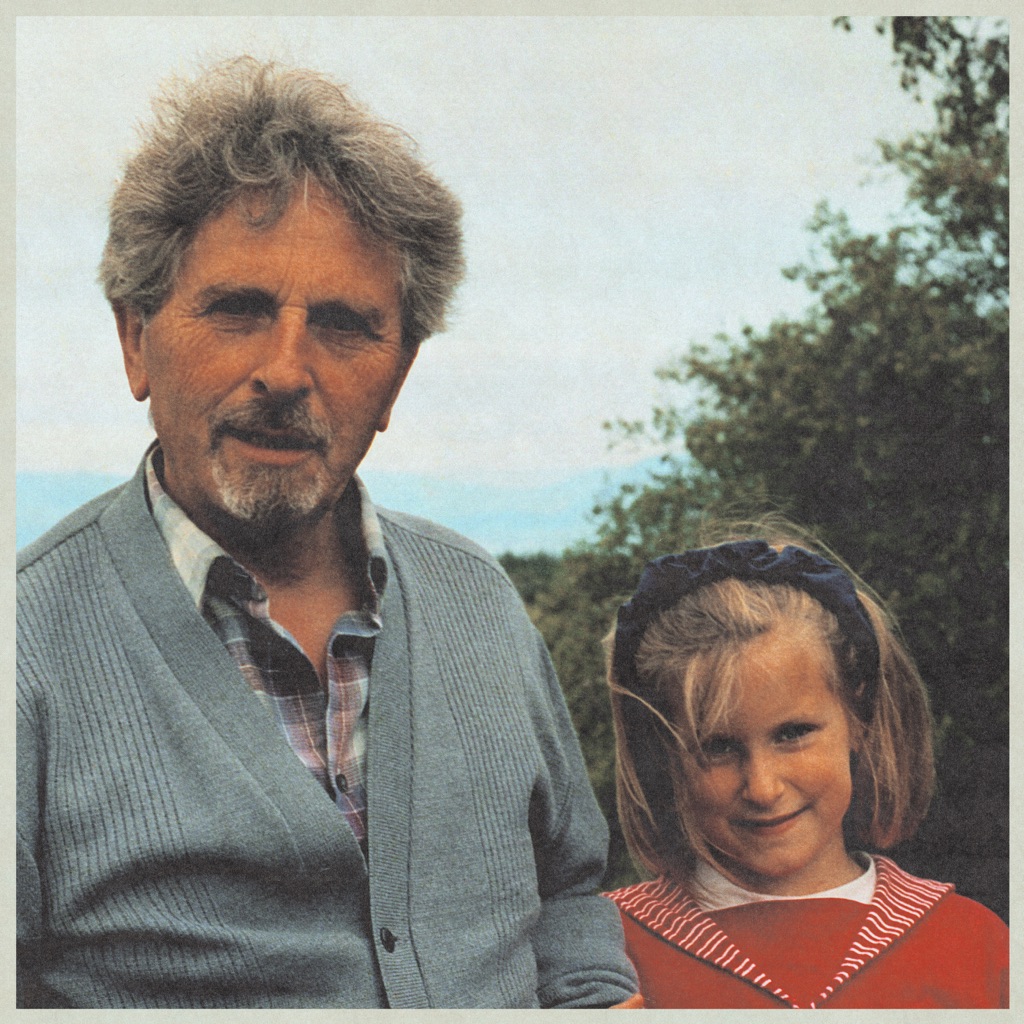

Like it did for listeners, Polly Jean Harvey’s 10th album came to her by surprise. “I\'d come off tour after \[2016’s\] *Hope Six Demolition Project*, and I was taking some time where I was just reassessing everything,” she tells Apple Music of what would become a seven-year break between records, during which it was rumored the iconic singer-songwriter might retire altogether. “Maybe something that we all do in our early fifties, but I\'d really wanted to see if I still felt I was doing the best that I could be with my life. Not wanting to sound doom-laden, but at 50, you do start thinking about a finite amount of time and maximizing what you do with that. I wanted to see what arose in me, see where I felt I needed to go with this last chapter of my life.” Harvey turned her attention to soundtrack work and poetry. In 2022, she published *Orlam*, a magical realist novel-in-verse set in the western English countryside where she grew up, written in a rare regional dialect. To stay sharp, she’d make time to practice scales on piano and guitar, to dig into theory. “Then I just started,” she says. “Melodies would arise, and instead of making up vowel sounds and consonant sounds, I\'d just pull at some of the poems. I wasn\'t trying to write a song, but then I had all these poems everywhere, overflowing out of my brain and on tables everywhere, bits of paper and drawings. Everything got mixed up together.” Written over the course of three weeks—one song a day—*I Inside the Old Year Dying* combines Harvey’s latest disciplines, lacing 12 of *Orlam*’s poems through similarly dreamy and atmospheric backdrops. The language is obscure but evocative, the arrangements (longtime collaborators Flood and John Parish produced) often vaporous and spare. But the feeling in her voice (especially on the title track and opener “Prayer at the Gate”) is inescapable. “I stopped thinking about songs in terms of traditional song structure or having to meet certain expectations, and I viewed them like I do the freedom of soundtrack work—it was just to create the right emotional underscore to the scene,” she says. “It was almost like the songs were just there, really wanting to come out. It fell out of me very easily. I felt a lot freer as a writer—from this album and hopefully onwards from now.”

During the pandemic, Fontaines D.C. singer Grian Chatten returned to Skerries, the town on Ireland’s East Coast where he’d spent his teenage years. One night, walking along the beach, something came to him. “It was when the moon conjures a strip of light along the horizon towards you, like a path to heaven,” he tells Apple Music. “And there’s the gentle ebb and flow of an invisible ocean around it.” As he looked to sea, new music seeped into his head—a sort of pier-end lounge pop played out on brass and strings. It didn’t really fit with the ideas Fontaines had been fermenting for their next record; instead it opened up inspiration for a solo album. There were, thought Chatten, stories to be told about lives being etched out in coastal areas like Skerries. “The whole atmosphere of the place, there’s something slightly set about it,” he says. “I’m really into fantasy, the Muppets movies and *The Dark Crystal*, or even *Sweeney Todd*, where they demand a slight suspension of disbelief of the audience in order to achieve, or embellish on, a very human emotion. I wanted to live the town through those kind of lenses.” By late 2022, as Chatten endured some heavy personal turbulence, the songs he was writing helped process his own experiences. “It was like, ‘How do I actually feel right now?’” he says. “Just by painting a picture of the darkness, I gleaned an understanding from it. I was then able to cordon it off.” Unsurprisingly then, *Chaos for the Fly* is as intimate as Chatten has sounded on record. Built from mostly acoustic foundations, the songs explore grief, isolation, betrayal, and escapism—but their intensity is a little more insidious and measured than on Fontaines’ sinewy music. Even the corrosively jaundiced “All of the People” is delivered with steady calm, Chatten warning, “People are scum/I will say it again” under a soft shroud of piano and precisely picked guitar. “There’s probably times on the record where it becomes almost self-indulgent, the personal nature of it,” he says. “It’s a startlingly fair reflection of me, I suppose. I didn’t really realize that was possible.” Read on for his track-by-track guide. **“The Score”** “I had a 10-day break in between two tours. I find it very difficult to switch off, and my manager said, ‘You need to go off somewhere,’ so I went to Madrid. I got antsy without being able to write music—the whole point, really, of me being away—and I actually asked Carlotta \[Cosials, singer/guitarist\] from Hinds if she knew any good guitar shops, so I could grab a Spanish guitar, a nylon. She sent me the name of a place that was just around the corner, and I had ‘The Score’ later on that day. When it comes to the second chord, I think that opens the curtain a bit. There’s a sort of subverted cabaret about it, which I really like. And there’s also a misdirection of the modalities of the chords. It goes to a kind of surprising chord. There’s a nice sleight of hand to the first few seconds of it. I really wanted that to be the tone-setter of the album.” **“Last Time Every Time Forever”** “This was inspired by the sound of these fruit machines and slot machines that I grew up with. There was this casino in town, called Bob’s Casino. It’s about addiction or dependence on something, and I’m not really talking specifically about drugs and booze or anything like that. I’m just talking about compulsive behavior and escapism, which are things that kind of shift my gears—I can relate to the pursuit of another world. It has that weird push that it does in the drums. I think it sounds kind of like stunted growth, like it’s glitching.” **“Fairlies”** “After Madrid, we went down to a town called Jerez, which was the birthplace of flamenco, I believe. We were going to go out to get a beer or something, myself and my fiancée. She was getting ready and I wrote that tune. There’s loads of bootleg recordings of The La’s, and I think they really affected me when I was slightly younger, when we were setting off the band. There’s a tune, ‘Tears in the Rain.’ There’s something about the way Lee Mavers does all that weird stuff with his vocals that really affected the way I write a lot of melodies. The snappy, jaunty, almost poke-y, edgy melody of the chorus, that was inspired by Lee Mavers. The verses are more Lee Hazlewood and Leonard Cohen, maybe.” **“Bob’s Casino”** “I heard the intro to ‘Bob’s Casino’ \[that night on the beach\]. Similar to ‘Last Time Every Time Forever,’ ‘Bob’s Casino’ is a tune about a kind of addiction and inertia and isolation. I wanted it to sound as beautiful as it sounds in the addict’s head, or the isolated person’s head, when they achieve those moments of respite. I think that’s a much more realistic picture than a tune that sounds scared straight or something. A play, or any good piece of screenwriting, is usually helped by the bad guys or the antagonist being relatable, or seeing a side of them that makes you empathize with them, or even love them, briefly. It creates this nice 3D effect. I enjoyed writing from that character’s perspective because I feel like I’m expressing something. I’m not saying that I am that character. But the character has a good chance of winning sometimes within me. The more I write about it and express it, then maybe the less chance that character has of taking over.” **“All of the People”** “This is probably my proudest moment from the album. I’m giving myself compliments here, but I think there’s a surgical kind of precision to it. There’s nothing wasted. I really like the natural swells. I like how it swells when the lyric swells. I really do feel that fucking shit sometimes, as do a lot of people. I’m grateful for that song, for what it did for my head when I wrote it. I can stand back and look at it now. It’s like I’ve blown that poison into a bottle and I’ve sealed the bottle, and now I’ve put it on a shelf.” **“East Coast Bed”** “‘East Coast Bed’ is about the death of my beloved hurling coach, who was like a second mother to me growing up, a woman called Ronnie Fay. The whole idea of the East Coast bed is firstly this refuge that she offered me when I was growing up. And then eventually, we laid her in her own East Coast bed when we buried her. The song is essentially about death. Not necessarily in a grim way, but in a sad, melancholic, moving-on way. That synth part that Dan Carey \[producer\] did sounds like the soul moving on for me. That was him exercising his great sympathy for the music that he works on.” **“Salt Throwers off a Truck”** “I remember the title coming to me when we were writing \[2022 Fontaines D.C. album\] *Skinty Fia*. There were lads on the back of a truck, salting the road outside the rehearsal space. I thought that was an interesting sight: ‘Oh, that’s a good title to have to justify with a good lyric.’ I like the fact that it scours the world a little bit. There’s New York in there and, although they’re not mentioned explicitly, other places too. The last verse is inspired by my own granddad’s death last year in Barrow-in-Furness. It’s different people at different stages. To me, it feels like when a director puts the audience in the eyes of a bird. There’s an omnipresence to it that I really like. It’s like when Scrooge is visited by the Ghosts of Christmas Past and Present and Future, and he gets to fly around, and visit all of these different vignettes, or all these different families in their houses.” **“I Am so Far”** “I wrote that one during the dreaded and not-very-aesthetic-to-talk-about lockdown. It was this kind of bleak and beautiful, ‘all the time in the world and nothing to do’ sort of thing that interested me then. That’s why there’s so much drudgery on the track. I wrote that on the East Coast again. It does sound to me a little bit like water, with light on it.” **“Season for Pain”** “I think it’s an abdication. It’s like cutting something you love out of your life. It sounds sad, and it is sad, and it is dark, but it’s putting up a necessary wall. It’s terminating a friendship or relationship with someone that you truly love. It’s not going to be easy for anyone, but it’s gone too far. I think there’s something about the production that slightly isolates it from the album. It feels slightly afterthought-ish, which I like. I like the end, which came from a jam. We’d finished recording the track, the tape was still rolling, and we just started playing, and then that became the outro. The song is about moving on and it sounds like I’m moving on at the end.”

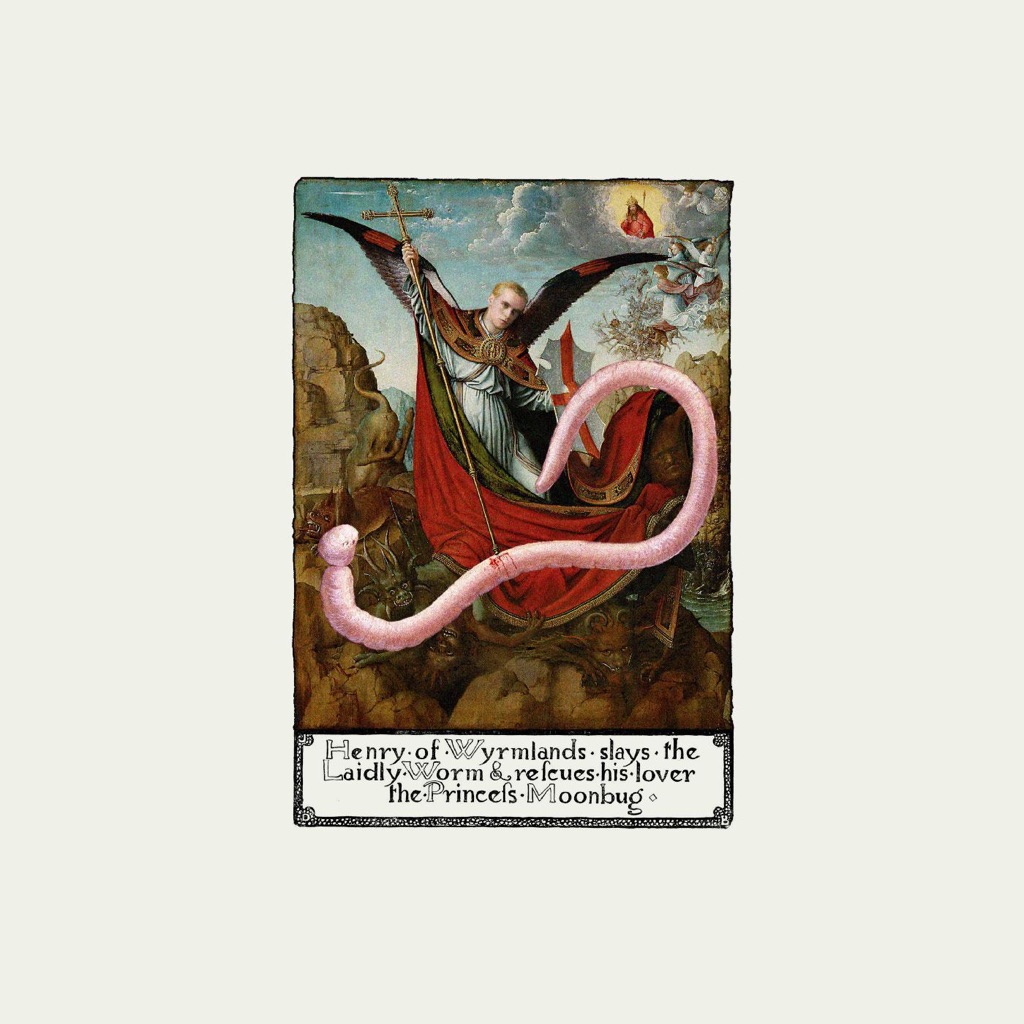

Created over the course of two years with a cast of 47 musicians – including a gospel choir and a 16-piece string orchestra – The Worm is less a concept album than a fully-fledged musical universe, transcending genre and medium. Set in a disorienting anachronistic version of Medieval England – as steeped in dystopian sci-fi fantasy as it is folklore and Old English mythology – it’s part political polemic, part deeply moving psychological journey, and finds frontman Henry Spychalski drawing on his own psycho-spiritual struggles to construct a modern parable about the impotence felt by individuals stuck inside gargantuan, labyrinthine systems of power that they are powerless to change. Henry explains,“We’re told to believe that anxiety and depression are purely material and biological – like a parasitic worm that can be removed with the right treatment. I think that really these conditions reflect the world that surrounds us - like colonies that a far bigger Worm has made in each of us - the psychological havoc wreaked by our inescapable capitalist reality and the looming apocalypse it has created."

The question of whether you want an MC like Earl Sweatshirt and a producer like The Alchemist to test each other’s limits is on some level an existential one: Like, isn’t the fact that the dreamlike flights of *VOIR DIRE* feel like comfort food a testament to how much they’ve already stretched our conception of hip-hop? Ten years out from his first “real” album (2013’s *Doris*), Earl sounds grateful, fulfilled, and yet no less enigmatic than when he was a kid, holding space for a history of Black diasporic art from Martinican poet Aimé Césaire to the Swazi-Xhosa South African pop legend Miriam Makeba without sacrificing the hermetic quality that made him so appealing in the first place. In Vince Staples, he continues to find the straight-talking foil he needs (“The Caliphate,” “Mancala”), and in Al a producer who can nudge him just a little closer to the hallelujahs he’s either too cool or evasive to embrace (“Mancala”). And at 26 minutes, the whole thing easily asks to be played again.

Close to five years on from their last transmission, Ulrika Spacek resurface from self-imposed exile with their third album, Compact Trauma, a collection of songs that function as a chance treatise of sorts for our current collective condition. With a title like that arriving at this point in time, it’s tempting to interpret the record solely in the context of the global events of the past few years, but the roots of these ten songs arc back much further in time, charged with their own personalised internal damage. Mid 2018, approaching exhaustion and feeling increasingly fragile from the stresses of itinerant road life, the five-piece of Rhys Edwards, Rhys Williams, Joseph Stone, Syd Kemp and Callum Brown began work in earnest on the follow up to their second album, Modern English Decoration. Released less than a year earlier and having promoted it constantly in the months that followed, now might have represented a fine moment for the band to take a breath. Yet Ulrika Spacek were not familiar with the concept of slowing down, conditioned by a strong work ethnic and the demands of capricious touring cycles that necessitated more content and at speed. Moving too fast, it was difficult to avoid the hazards up ahead. The band’s previous albums had both been recorded in KEN, a studio and rehearsal space in Homerton that also doubled as their shared home. As writing for album three began, KEN suddenly became another victim to the indiscriminate violence of gentrification, rendering the project both hub- and homeless. Writing and recording at KEN was then abruptly shifted to a professional studio in Hackney, only the second time they had worked in such conditions, and tensions and logistical difficulties soon became apparent. The enforced switch to an unfamiliar locale would have been discomforting enough, but when allied with the fractures already beginning to splinter through the band, made for an especially frazzled experience. Somehow, a record began to emerge piecemeal from the gloom, though it was one obviously infected with its circumstances. Trauma, in its myriad forms, is often hard to qualify, even harder to rationalise. When something begins to go wrong, how do you gain perspective? What is a temporary roadblock, and what is unmitigated disaster? In its first phase of life, Compact Trauma was a document of a band striving to perfect an idea while the universe around them seemed to want to shut down. And then, at an impasse of sorts and with a record halfway complete, it suddenly did. If Ulrika Spacek were a band in need of the breaks applying, it was the force of a global pandemic that made it happen. As the world stood still, Compact Trauma was filed away, unfinished and unheard by the wider world, possibly to remain that way forever. And yet, there was to be a second act. If mutability is our tragedy, it's also our hope, clearer days slowly began to emerge as the bad slipped away. The wound, as the saying goes, is the place where the light enters you. The prolonged break enforced by myriad lockdowns may have separated the group but it also afforded the five time to reflect on what had already been committed to tape.. As the lights came back on and the shutters up, they found themselves drawn back towards Compact Trauma. What they rediscovered was a record that seemed to preempt the shared grief of a global pandemic. Even if the specifics were different, the themes were uncannily similar. Addressing existential freak out, displacement, substance reliance and encroaching self-doubt, these highly personalised songs suddenly took on a wider significance, speaking in part to a bigger narrative. Opening track, ‘The Sheer Drop’, begins with the line “Homerton is caving in”; ‘It Will Come Sometime’ describes a “liver like a lightbulb and swelling”; and Lounge Angst (an almost perfect description of those maddening lockdown days indoors) laments, ‘seems my friends grew up or left’. The fear and panic is palpable. The lyrics are matched to a soundtrack that oscillates between the febrile and the off-kilter, unconventional song structures and knotty arrangements either spinning the listener in unexpected directions or offering some kind of cathartic release. Take, as example, the aforementioned opener, ‘The Sheer Drop’. A wire-taut exercise in tension-and-release rendered in three parts, a whimsical synth opening giving way to characteristic chiming guitars before a nail biting coda sets its controls for the heart of the sun or the end of the world, whichever comes first. Either way, it’s a hell of a way to reintroduce yourself after a five year absence. ‘If The Wheels Are Coming Off, The Wheels Are Coming Off’ is equally instructive, a lacerating exposition of self-doubt that bursts into ecstatic release at its climax, demanding repeat listens, while ‘Stuck At The Door’ is an 11-minute Pacific North West-style epic that threatens, ‘the worst of it’s to come’. But it’s the title track that might be the true heartbeat of the record. Either addressing itself or some unknown assailant, it begins by demanding that they “take your hands and your head off the table”, while spiralling around a breathless riff fueled by an infectious anxious energy, before changing tact completely and shifting to a lullaby-like finale, concluding with the ominous thought, “compact trauma? Or full blown disaster? I'll be back in an hour (Or so i think)”. It’s a fitting encapsulation of a highly complex record. They could have left it alone, but in coming back to what they knew, Ulrika Spacek found their best work yet.