New York drummer Allison Miller marks the 10th anniversary of her Boom Tic Boom sextet with an album of original compositions as refined and eccentric as the band itself. With violinist Jenny Scheinman, cornetist Kirk Knuffke, clarinetist Ben Goldberg, pianist Myra Melford, and bassist Todd Sickafoose, Miller creates beautifully whimsical jazz in which form unfolds like a dream and style is a moving target. Standout tracks on this fourth studio album have a focused theme: “Malaga” features an arrangement so cinematic that the music feels like a drone tour of the Spanish city; “Zev — The Phoenix” juxtaposes a rakish clarinet-driven vamp with introspective piano lyricism to create the mood of a child at play. Along with the LP\'s ubiquitous melody and groove, one of its greatest strengths is the band’s esprit de corps; each improviser is uniquely expressive while looking to a shared musical horizon.

What do you do when things fall apart? If you’re Ariana Grande, you pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and head for the studio. Her hopeful fourth album, *Sweetener*—written after the deadly attack at her concert in Manchester, England—encouraged fans to stay strong and open to love (at the time, the singer was newly engaged to Pete Davidson). Shortly after the album’s release in August 2018, things fell apart again: Grande’s ex-boyfriend, rapper Mac Miller, died from an overdose in September, and she broke off her engagement a few weeks later. Again, Grande took solace from the intense, and intensely public, melodrama in songwriting, but this time things were different. *thank u, next*, mostly recorded over those tumultuous months, sees her turning inward in an effort to cope, grieve, heal, and let go. “Though I wish he were here instead/Don’t want that living in your head,” she confesses on “ghostin,” a gutting synth-and-strings ballad that hovers in your throat. “He just comes to visit me/When I’m dreaming every now and then.” Like many of the songs here, it was produced by Max Martin, who has a supernatural way of making pain and suffering sound like beams of light. The album doesn\'t arrive a minute too soon. As Grande wrestles with what she wants—distance (“NASA”) and affection (“needy”), anonymity (“fake smile\") and star power (“7 rings”), and sex without strings attached (“bloodline,” “make up”)—we learn more and more about the woman she’s becoming: complex, independent, tenacious, flawed. Surely embracing all of that is its own form of self-empowerment. But Grande also isn\'t in a rush to grow up. A week before the album’s release, she swapped out a particularly sentimental song called “Remember” with the provocative, NSYNC-sampling “break up with your girlfriend, i\'m bored.” As expected, it sent her fans into a frenzy. “I know it ain’t right/But I don’t care,” she sings. Maybe the ride is just starting.

For a project so shrouded in mystery in the run-up to its release, the origin story behind Better Oblivion Community Center isn\'t particularly enigmatic at all: Phoebe Bridgers and Conor Oberst started writing some songs together in Los Angeles, unclear what their final destination would be until they had enough good ones that a proper album seemed inevitable. Plus, the anonymity and secrecy allowed them to subvert any expectations that might come from news of high-profile singer-songwriter types teaming up. “We just realized that the songs were their own style and they didn\'t sound like either of us,” Bridgers tells Apple Music. “I don\'t think that they would have felt comfortable on one of my records or one of Conor\'s records. And even the band name—Conor came up with it and we didn\'t think about it as a real thing, and then people were like, \'Whoa, clearly it\'s this elaborate concept,\' and we\'re like, \'Really? Cool.\'” Let Bridgers and Oberst guide you through each track of their no-longer-enigmatic debut. **“Didn\'t Know What I Was in For”** Oberst: “When you sit down and write a song with someone, you kind of find out pretty fast—even if you\'re friends with them—if you gel on a creative level.” Bridgers: “I think it\'s really important to be able to have bad ideas in front of someone to create with them, and realizing I could do that with him was really important to our dynamic. We were able to tell each other what we actually thought about style and all that stuff, starting with that song.” **“Sleepwalkin’”** Oberst: “That was one of the first ones we started recording with a rhythm section, and I knew it was gonna be fun and actually be rock music, and I got excited for that.” Bridgers: “We did mostly real live takes of the band stuff, which was really fun. When I record my records, I overdub into oblivion because I like deleting and reworking and rethinking halfway through, so it\'s pretty different for me.” **“Dylan Thomas”** Oberst: “That was the last one we wrote, so we kind of had our method a little more dialed. It immediately felt like a good thing to put out there first, as far as people getting the whole concept quickly: that it\'s two singers and maybe more upbeat than people would think. I guess \[Dylan Thomas\] is a kind of antiquated reference for 2019, but he\'s always been one of my favorite poets.” **“Service Road”** Oberst: “That one is kind of like a heavy song, lyrically. I don\'t know if I would have been able to get to all that stuff without Phoebe\'s help—she\'s very empathetic in her writing.” Bridgers: “It\'s funny, I didn\'t really think about it like, \'Oh, helping Conor write something heavy\'; it was just immediately pretty familiar territory and I didn\'t really have to think twice about it.” Oberst: “It\'s cool when you find someone to write songs with, where a lot of it can go unsaid and you can be automatically on the same page without having to explain a bunch of stuff up front. \'Cause I feel like other times when I\'ve been in co-writing situations, if you\'re coming from super-different places, it takes a bunch of legwork to even get to a starting point.” **“Exception to the Rule”** Oberst: “That one changed the most from the demo to the actual recording. It really came into its own in the recording, with all the pulsing keyboard—that was not at all the way the demo was. That\'s always fun, when something changes in the recording process.” **“Chesapeake”** Bridgers: “I kind of started it as my own song with my friend Christian helping me out. We were getting together, ranting about music, and we were like, \'What if we wrote a song about what we think is stupid in music?\' and kind of ranted for hours over those chords. And then Conor, who was tripping on mushrooms, wanders into the room, like, \'Are you guys gonna just talk about writing this song or when are you gonna actually write it?\' We were kind of brushing him off, and then he started writing with us and then it immediately became real. And yeah, he gave us a run for our money on mushrooms.” **“My City”** Bridgers: “I think it\'s funny when people call LA \'this town.\' It\'s fucking so corny and funny, and the amount that I hear it is really disturbing. Like, \'Yeah, this town spits you out in a heartbeat.\' We started talking about that and then it became a lyric, and then weirdly kind of started being about Los Angeles. One of my favorite ways to write with Conor is just to go on a rant about something and then he spits out beautiful lyrics with whatever I said.” **“Forest Lawn”** Oberst: “Yeah, I guess there are a lot of LA references on this record. Phoebe would talk about when she was a teenager they would hang out and party and smoke weed in Forest Lawn. Every teenager in every town ends up going to a cemetery. Youth and reckless abandon amongst dead bodies—there\'s something kind of nice about that image to me.” **“Big Black Heart”** Bridgers: “I feel like—well, I know—that I subliminally stole the riff from a Tigers Jaw song. An early 2000s emo band...” Oberst: “She\'s like, \'I wanna email them and ask them if we can use it.\' And I was like, \'Damn, Phoebe, you\'re extremely ethical. I really appreciate your ethics.\'\" Bridgers: “They were very sweet, and they were like, \'What the fuck are you talking about? That\'s not stealing it.\'” Oberst: “I think Phoebe has a great scream and she never uses it, so I convinced her to bring that in, which is cool.” **“Dominos”** Oberst: “That\'s a cover. Taylor Hollingsworth is a songwriter from Birmingham, Alabama, a guy I\'ve played with a lot, that we both love as a person and as a musician. We just love that song. I had called him and got him to record those little samples on the phone of him talking. I kind of lied a little bit, like, \'Yeah, Taylor, I\'m making this sound collage for a song I\'m working on.\' When we finally played it for him, he was totally floored and got a little teary-eyed. He\'s like, \'I can\'t believe you guys recorded my song.\' So, that was really sweet.”

Big Thief had only just finished work on their 3rd album, U.F.O.F. – “the celestial twin” – days before in a cabin studio in the woods of Washington State. Now it was time to birth U.F.O.F.’s sister album – “the earth twin” – Two Hands. 30 miles west of El Paso, surrounded by 3,000 acres of pecan orchards and only a stone’s throw from the Mexican border, Big Thief (a.k.a. Adrianne Lenker, Buck Meek, Max Oleartchik, and James Krivchenia) set up their instruments as close together as possible to capture their most important collection of songs yet. Where U.F.O.F.layered mysterious sounds and effects for levitation, Two Hands grounds itself on dried-out, cracked desert dirt. In sharp contrast to the wet environment of the U.F.O.F. session, the southwestern Sonic Ranch studio was chosen for its vast desert location. The 105-degree weather boiled away any clinging memories of the green trees and wet air of the previous session. Two Hands had to be completely different — an album about the Earth and the bones beneath it. The songs were recorded live with almost no overdubs. All but two songs feature entirely live vocal takes, leaving Adrianne’s voice suspended above the mix in dry air, raw and vulnerable as ever. “Two Hands has the songs that I’m the most proud of; I can imagine myself singing them when I’m old,” says Adrianne. “Musically and lyrically, you can’t break it down much further than this. It’s already bare-bones.” Lyrically this can be felt in the poetic blur of the internal and external. These are political songs without political language. They explore the collective wounds of our Earth. Abstractions of the personal hint at war, environmental destruction, and the traumas that fuel it. Across the album, there are genuine attempts to point the listener towards the very real dangers that face our planet. When Adrianne sings “Please wake up,” she’s talking directly to the audience. Engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who were both behind U.F.O.F., capture the live energy as instinctually and honestly as possible. Sarlo teamed up with James Krivchenia to mix the album, where they sought to emphasize raw power and direct energy inherent in the takes. The journey of a song from the stage to the record is often a difficult one. Big Thief’s advantage is their bond and loving centre as a chosen family. They spend almost 100% of their lives together working towards a sound that they all agree upon. A band with this level of togetherness is increasingly uncommon. If you ask drummer James Krivchenia, bassist Max Oleartchik or guitarist Buck Meek how they write their parts, they will describe — passionately — the experience of hearing Adrianne present a new song, listening intently for hints of parts that already exist in the ether and the undertones to draw out with their respective instruments. With raw power and intimacy, Two Hands folds itself gracefully into Big Thief’s impressive discography. This body of work grows deeper and more inspiring with each new album.

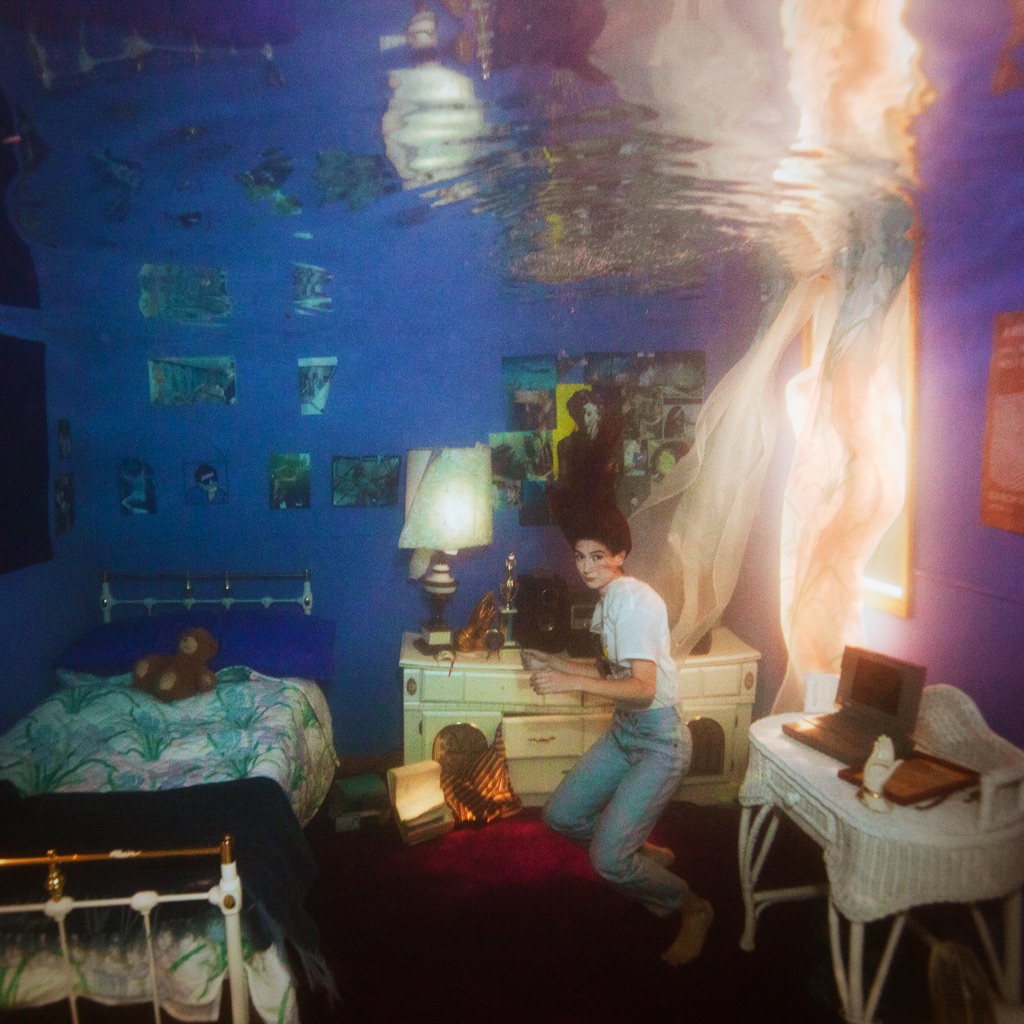

Beginning with the haunting alt-pop smash “Ocean Eyes” in 2016, Billie Eilish made it clear she was a new kind of pop star—an overtly awkward introvert who favors chilling melodies, moody beats, creepy videos, and a teasing crudeness à la Tyler, The Creator. Now 17, the Los Angeles native—who was homeschooled along with her brother and co-writer, Finneas O’Connell—presents her much-anticipated debut album, a melancholy investigation of all the dark and mysterious spaces that linger in the back of our minds. Sinister dance beats unfold into chattering dialogue from *The Office* on “my strange addiction,” and whispering vocals are laid over deliberately blown-out bass on “xanny.” “There are a lot of firsts,” says FINNEAS. “Not firsts like ‘Here’s the first song we made with this kind of beat,’ but firsts like Billie saying, ‘I feel in love for the first time.’ You have a million chances to make an album you\'re proud of, but to write the song about falling in love for the first time? You only get one shot at that.” Billie, who is both beleaguered and fascinated by night terrors and sleep paralysis, has a complicated relationship with her subconscious. “I’m the monster under the bed, I’m my own worst enemy,” she told Beats 1 host Zane Lowe during an interview in Paris. “It’s not that the whole album is a bad dream, it’s just… surreal.” With an endearingly off-kilter mix of teen angst and experimentalism, Billie Eilish is really the perfect star for 2019—and here is where her and FINNEAS\' heads are at as they prepare for the next phase of her plan for pop domination. “This is my child,” she says, “and you get to hold it while it throws up on you.” **Figuring out her dreams:** **Billie:** “Every song on the album is something that happens when you’re asleep—sleep paralysis, night terrors, nightmares, lucid dreams. All things that don\'t have an explanation. Absolutely nobody knows. I\'ve always had really bad night terrors and sleep paralysis, and all my dreams are lucid, so I can control them—I know that I\'m dreaming when I\'m dreaming. Sometimes the thing from my dream happens the next day and it\'s so weird. The album isn’t me saying, \'I dreamed that\'—it’s the feeling.” **Getting out of her own head:** **Billie:** “There\'s a lot of lying on purpose. And it\'s not like how rappers lie in their music because they think it sounds dope. It\'s more like making a character out of yourself. I wrote the song \'8\' from the perspective of somebody who I hurt. When people hear that song, they\'re like, \'Oh, poor baby Billie, she\'s so hurt.\' But really I was just a dickhead for a minute and the only way I could deal with it was to stop and put myself in that person\'s place.” **Being a teen nihilist role model:** **Billie:** “I love meeting these kids, they just don\'t give a fuck. And they say they don\'t give a fuck *because of me*, which is a feeling I can\'t even describe. But it\'s not like they don\'t give a fuck about people or love or taking care of yourself. It\'s that you don\'t have to fit into anything, because we all die, eventually. No one\'s going to remember you one day—it could be hundreds of years or it could be one year, it doesn\'t matter—but anything you do, and anything anyone does to you, won\'t matter one day. So it\'s like, why the fuck try to be something you\'re not?” **Embracing sadness:** **Billie:** “Depression has sort of controlled everything in my life. My whole life I’ve always been a melancholy person. That’s my default.” FINNEAS: “There are moments of profound joy, and Billie and I share a lot of them, but when our motor’s off, it’s like we’re rolling downhill. But I’m so proud that we haven’t shied away from songs about self-loathing, insecurity, and frustration. Because we feel that way, for sure. When you’ve supplied empathy for people, I think you’ve achieved something in music.” **Staying present:** **Billie:** “I have to just sit back and actually look at what\'s going on. Our show in Stockholm was one of the most peak life experiences we\'ve had. I stood onstage and just looked at the crowd—they were just screaming and they didn’t stop—and told them, \'I used to sit in my living room and cry because I wanted to do this.\' I never thought in a thousand years this shit would happen. We’ve really been choking up at every show.” FINNEAS: “Every show feels like the final show. They feel like a farewell tour. And in a weird way it kind of is, because, although it\'s the birth of the album, it’s the end of the episode.”

JAIME I wrote this record as a process of healing. Every song, I confront something within me or beyond me. Things that are hard or impossible to change, words and music to describe what I’m not good at conveying to those I love, or a name that hurts to be said: Jaime. I dedicated the title of this record to my sister who passed away as a teenager. She was a musician too. I did this so her name would no longer bring me memories of sadness and as a way to thank her for passing on to me everything she loved: music, art, creativity. But, the record is not about her. It’s about me. It’s not as veiled as work I have done before. I’m pretty candid about myself and who I am and what I believe. Which, is why I needed to do it on my own. I wrote and arranged a lot of these songs on my laptop using Logic. Shawn Everett helped me make them worthy of listening to and players like Nate Smith, Robert Glasper, Zac Cockrell, Lloyd Buchanan, Lavinia Meijer, Paul Horton, Rob Moose and Larry Goldings provided the musicianship that was needed to share them with you. Some songs on this record are years old that were just sitting on my laptop, forgotten, waiting to come to life. Some of them I wrote in a tiny green house in Topanga, CA during a heatwave. I was inspired by traveling across the United States. I saw many beautiful things and many heartbreaking things: poverty, loneliness, discouraged people, empty and poor towns. And of course the great swathes of natural, untouched lands. Huge pink mountains, seemingly endless lakes, soaring redwoods and yellow plains that stretch for thousands of acres. There were these long moments of silence in the car when I could sit and reflect. I wondered what it was I wanted for myself next. I suppose all I want is to help others feel a bit better about being. All I can offer are my own stories in hopes of not only being seen and understood, but also to learn to love my own self as if it were an act of resistance. Resisting that annoying voice that exists in all of our heads that says we aren’t good enough, talented enough, beautiful enough, thin enough, rich enough or successful enough. The voice that amplifies when we turn on our TVs or scroll on our phones. It’s empowering to me to see someone be unapologetically themselves when they don’t fit within those images. That’s what I want for myself next and that’s why I share with you, “Jaime”. Brittany Howard

It\'s hard to imagine Bruce Springsteen describing a project of his as a concept album—too much prog baggage, too much expectation of some big, grand, overarching *story*. But nothing he\'s done across five decades as one of rock\'s most accomplished storytellers has had the singular, specific focus and locus, lyrically and musically, as this long-gestating solo effort—a lush meditation on the landscape of the western United States and the people who are drawn there, or got stuck there. Neither a bare-bones acoustic effort like *Nebraska* nor a fully tricked-out E Street Band affair, this set of 13 largely subdued character-driven songs (his first new ones since 2014\'s *High Hopes*, following five years immersed in memoir) is ornamented with strings and horns and slide guitar and banjo that sound both dusty and Dusty. They trade in the most familiar of American iconography—trains, hitchhikers, motels, sunsets, diners, Hollywood, and, of course, wild horses—but aren\'t necessarily antiquated; the clichés are jumping-off points, aiming for timelessness as much as nostalgia. The battered stuntman of “Drive Fast” could be licking, and cataloging, his wounds in 1959 or 2019. As convulsive and pivotal as the current moment may feel, restlessness and aimlessness and disenfranchisement are evergreen, and the songs are built to feel that way. In true Springsteen fashion, the personal is elevated to the mythical.

What happens when the reigning queen of bubblegum pop goes through a breakup? Exactly what you’d think: She turns around and creates her most romantic, wholehearted, blissed-out work yet. Written with various pop producers in LA (Captain Cuts), New York (Jack Antonoff), and Sweden, as well as on a particularly formative soul-searching trip to the Italian coast, Jepsen’s fourth album *Dedicated* is poptimism at its finest: joyous and glitzy, rhythmic and euphoric, with an extra layer of kitsch. It’s never sad—that just isn’t Jepsen—but the “Call Me Maybe” star *does* get more in her feelings; songs like “No Drug Like Me” and “Right Words Wrong Time” aren\'t about fleeing pain so much as running to it. As Jepsen puts it on the synth ballad “Too Much,” she’d do anything to get the rush of being in love, even if it means risking heartache again and again. “Party for One,” the album’s standout single, is an infectious, shriek-worthy celebration of being alone that also acknowledges just how difficult that can be: “Tried to let it go and say I’m over you/I’m not over you/But I’m trying.”

It was on a mountainside in Cumbria that the first whispers of Cate Le Bon’s fifth studio album poked their buds above the earth. “There’s a strange romanticism to going a little bit crazy and playing the piano to yourself and singing into the night,” she says, recounting the year living solitarily in the Lake District which gave way to Reward. By day, ever the polymath, Le Bon painstakingly learnt to make solid wood tables, stools and chairs from scratch; by night she looked to a second-hand Meers — the first piano she had ever owned —for company, “windows closed to absolutely everyone”, and accidentally poured her heart out. The result is an album every bit as stylistically varied, surrealistically-inclined and tactile as those in the enduring outsider’s back catalogue, but one that is also intensely introspective and profound; her most personal to date. This sense of privacy maintained throughout is helped by the various landscapes within which Reward took shape: Stinson Beach, LA, and Brooklyn via Cardiff and The Lakes. Recording at Panoramic House [Stinson Beach, CA], a residential studio on a mountain overlooking the ocean, afforded Le Bon the ability to preserve the remoteness she had captured during the writing of Reward in Staveley, Lake District. Over this extended period a cast of trusted and loved musicians joined Le Bon, Khouja and fellow co-producer Josiah Steinbrick — Stella Mozgawa (of Warpaint) on drums and percussion; Stephen Black (aka Sweet Baboo) on bass and saxophone and longtime collaborators Huw Evans (aka H.Hawkline) and Josh Klinghoffer on guitars — and were added to the album, “one by one, one on one”. The fact that these collaborators have appeared variously on Le Bon’s previous outputs no doubt goes some way to aid the preservation of a signature sound despite a relatively drastic change in approach. Be it on her more minimalist, acoustic-leaning 2009 debut album Me Oh My or critically acclaimed, liquid-riffed 2013 LP Mug Museum as well as 2016s Crab Day, Cate Le Bon’s solo work — and indeed also her production work, such as that carried out on recent Deerhunter album Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? (4AD, January 2019) — has always resisted pigeonholing, walking the tightrope between krautrock aloofness and heartbreaking tenderness; deadpan served with a twinkle in the eye, a flick of the fringe and a lick of the Telecaster. The multifaceted nature of Le Bon’s art — its ability to take on multiple meanings and hold motivations which are not immediately obvious — is evident right down to the album’s very name. “People hear the word ‘reward’ and they think that it’s a positive word” says Le Bon, “and to me it’s quite a sinister word in that it depends on the relationship between the giver and the receiver. I feel like it’s really indicative of the times we’re living in where words are used as slogans, and everything is slowly losing its meaning.” The record, then, signals a scrambling to hold onto meaning; it is a warning against lazy comparisons and face values. It is a sentiment nicely summed up by the furniture-making musician as she advises: “Always keep your hand behind the chisel.”

Upon erupting into a house single fit for any Vegas club, *Courage*’s opener, “Flying on My Own,” finds Celine Dion alone. “The warmer winds will carry me,” she sings at high altitude, her voice climbing. “Anywhere I want them to/If you could see what I can see/That nothing’s blocking my view.” *Courage* is the Canadian star’s first album (in any language) since the 2016 death of her husband and longtime manager, René Angélil. Recorded almost entirely in Las Vegas—near the end of the wildly successful eight-year residency there that she and Angélil had conceived of together—these are songs of resilience, of moving forward when all you want is to look back. To get there, she collaborated with some of modern pop’s biggest names (Sia, Sam Smith, Skylar Grey, Greg Kurstin, David Guetta) for everything from heartbreaking ballads (“Courage”) to brief flirtations with rapping (the piano-driven lullaby “Perfect Goodbye,” which features contributions from Steve Aoki). “I’m having some kind of breakthrough,” she sings on “Lying Down,” a tale of faltering love. “I’m ready to live.”

Look past its futurist textures and careful obfuscations, and there’s something deeply human about FKA twigs’ 21st-century R&B. On her second full-length, the 31-year-old British singer-songwriter connects our current climate to that of Mary Magdalene, a healer whose close personal relationship with Christ brought her scorn from those who would ultimately write her story: men. “I\'m of a generation that was brought up without options in love,” she tells Apple Music. “I was told that as a woman, I should be looked after. It\'s not whether I choose somebody, but whether somebody chooses me.” Written and produced by twigs, with major contributions from Nicolas Jaar, *MAGDALENE* is a feminist meditation on the ways in which we relate to one another and ourselves—emotionally, sexually, universally—set to sounds that are at once modern and ancient. “Now it’s like, ‘Can you stand up in my holy terrain?’” she says, referencing the titular lyric from her mid-album collaboration with Future. “‘How are we going to be equals in this? Spiritually, am I growing? Do you make me want to be a better person?’ I’m definitely still figuring it out.” Here, she walks us through the album track by track. **thousand eyes** “All the songs I write are autobiographical. Anyone that\'s been in a relationship for a long time, you\'re meshed together. But unmeshing is painful, because you have the same friends or your families know each other. No matter who you are, the idea of leaving is not only a heart trauma, but it\'s also a social trauma, because all of a sudden, you don\'t all go to that pub that you went to together. The line \[\'If I walk out the door/A thousand eyes\'\] is a reference to that. At the time, I was listening to a lot of Gregorian music. I’d started really getting into medieval chords before that, and I\'d found some musicians that play medieval music and done a couple sessions with them. Even on \[2014\'s\] *LP1*, I had ‘Closer,’ which is essentially a hymn. I spent a lot of time in choir as a child and I went to Sunday school, so it’s part of who I am at this stage.” **home with you** “I find things like that interesting in the studio, just to play around and bring together two completely different genres—like Elton John chords and a hip-hop riff. That’s what ‘home with you’ was for me: It’s a ballad and it\'s sad, but then it\'s a bop as well, even though it doesn\'t quite ever give you what you need. It’s about feeling pulled in all directions: as a daughter, or as a friend, or as a girlfriend, or as a lover. Everyone wanting a piece of you, but not expressing it properly, so you feel like you\'re not meeting the mark.” **sad day** “It’s like, ‘Will you take another chance with me? Can we escape the mundane? Can we escape the cyclical motion of life and be in love together and try something that\'s dangerous and exhilarating? Yeah, I know I’ve made you sad before, but will you give me another chance?\' I wrote this song with benny blanco and Koreless. I love to set myself challenges, and it was really exciting to me, the challenge of retaining my sound while working with a really broad group of people. I was lucky working with Benny, in the fact that he creates an environment where, as an artist, you feel really comfortable to be yourself. To me, that\'s almost the old-school definition of a producer: They don\'t have to be all up in your grill, telling you what to do. They just need to lay a really beautiful, fertile soil, so that you can grow to be the best you in the moment.” **holy terrain** “I’m saying that I want to find a man that can stand up next to me, in all of my brilliance, and not feel intimidated. To me, Future’s saying, ‘Hey, I fucked up. I filled you with poison. I’ve done things to make you jealous. Can you heal me? Can you tell me how to be a better man? I need the guidance, of a woman, to show me how to do that.’ I don\'t think that there are many rappers that can go there, and just put their cards on the table like that. I didn\'t know 100%, once I met Future, that it would be right. But we spoke on the phone and I played him the album and I told him what it was about: ‘It’s a very female-positive, femme-positive record.’ And he was just like, ‘Yeah. Say no more. I\'ve got this.’ And he did. He crushed it. To have somebody who\'s got patriarchal energy come through and say that, wanting to stand up and be there for a woman, wanting to have a woman that\'s an equal—that\'s real.” **mary magdalene** “Let’s just imagine for one second: Say Jesus and Mary Magdalene are really close, they\'re together all the time. She\'s his right-hand woman, she’s his confidante, she\'s healing people with him and a mystic in her own right. So, at that point, any man and woman that are spending that much time together, they\'re likely to be what? Lovers. Okay, cool. So, if Mary had Jesus\' children, that basically debunks the whole of history. Now, I\'m not saying that happened. What I\'m saying is that the idea of people thinking that might happen is potentially really dangerous. It’s easier to call her a whore, because as soon as you call a woman a whore, it devalues her. I see her as Jesus Christ\'s equal. She’s a male projection and, I think, the beginning of the patriarchy taking control of the narrative of women. Any woman that\'s done anything can be subject to that; I’ve been subject to that. It felt like an apt time to be talking about it.” **fallen alien** “When you\'re with someone, and they\'re sleeping, and you look at them, and you just think, \'No.\' For me, it’s that line, \[\'When the lights are on, I know you/When you fall asleep, I’ll kick you down/By the way you fell, I know you/Now you’re on your knees\'\]. You\'re just so sick of somebody\'s bullshit, you\'re just taking it all day, and then you\'re in bed next to them, and you\'re just like, ‘I can\'t take this anymore.’” **mirrored heart** “People always say, ‘Whoever you\'re with, they should be a reflection of yourself.’ So, if you\'re looking at someone and you think, ‘You\'re a shitbag,’ then you have to think about why it was that person, at that time, and what\'s connecting you both. What is the reflection? For others that have found a love that is a true reflection of themselves, they just remind me that I don\'t have that, a mirrored heart.” **daybed** “Have you ever forgotten how to spell a really simple word? To me, depression\'s a bit like that: Everything\'s quite abstract, and even slightly dizzy, but not in a happy way. It\'s like a very slow circus. Suddenly the fruit flies seem friendly, everything in the room just starts having a different meaning and you even have a different relationship with the way the sofa cushions smell. \[Masturbation\] is something to raise your endorphins, isn\'t it? It’s either that or try and go to the gym, or try and eat something good. You almost can\'t put it into words, but we\'ve all been there. I sing, \'Active are my fingers/Faux, my cunnilingus\': You\'re imagining someone going down on you, but they\'re actually not. You open your eyes, and you\'re just there, still on your sofa, still watching daytime TV.” **cellophane** “It\'s just raw, isn\'t it? It didn\'t need a thing. The vocal take that\'s on the record is the demo take. I had a Lyft arrive outside the studio and I’d just started playing the piano chords. I was like, ‘Hey, can you just give me like 20, 25 minutes?’ And I recorded it as is. I remember feeling like I wanted to cry, but I just didn\'t feel like it was that suitable to cry at a studio session. I often want everything to be really intricate and gilded, and I want to chip away at everything, and sculpt it, and mold it, and add layers. The thing I\'ve learned on *MAGDALENE* is that you don\'t need to do that all the time, and just because you can do something, it doesn\'t mean you should. That\'s been a real growing experience for me—as a musician, as a producer, as a singer, even as a dancer. Something in its most simple form is beautiful.”

A raw and scintillating state-of-Dublin address.

FLY or DIE II: bird dogs of paradise is the much-anticipated follow-up to composer, trumpeter, and (now) singer jaimie branch's debut Fly or Die, which was dubbed one of the “Best Albums of 2017” by The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, NPR Music, WIRE, Stereogum, Aquarium Drunkard, and more. Written (mostly) while on her first European tour with Fly or Die in November 2018; and recorded (mostly) in studio at Total Refreshment Centre and live at Café OTO in London UK at the end of that tour, bird dogs of paradise is the result of a never-satisfied branch pushing her distinct style of progressive composition to new heights — while also stepping forward as a vocalist for the first time. “So much beauty lies in the abstract of instrumental music,” says branch in the album’s liner notes, “but being this ain’t a particularly beautiful time, I’ve chosen a more literal path. The voice is good for that.” On the album’s epic opening opus “prayer for amerikkka pt.1 and 2” branch calls out “a bunch of wide-eyed racists” between searing trumpet ad libs atop a massive, down-tuned blues. On the album’s closing track “love song (for assholes & clowns)” she laughs in their faces - an unhinged, unflinching, mix of anger and humor paired with a classic shuffle beat. Between both ends is an instrumental chronicle that traverses a deep sea of dystopian Americana without trepidation. Her trumpet – sometimes soft and pleading and other times brash and seething – is always at the helm. Branch and company are on a quest for sonic saturation here and they conjure up moments of real reckoning - hopefulness, hopelessness, danger, and joy. A cinematic sojourn from our earth to imagined worlds above, bird dogs of paradise dares you to feel again, or as branch says, “now sound the trumpets and get ready to roll.”

There’s nothing all that subtle about Jamila Woods naming each of these all-caps tracks after a notable person of color. Still, that’s the point with *LEGACY! LEGACY!*—homage as overt as it is original. True to her own revolutionary spirit, the Chicago native takes this influential baker’s dozen of songs and masterfully transmutes their power for her purposes, delivering an engrossingly personal and deftly poetic follow-up to her formidable 2016 breakthrough *HEAVN*. She draws on African American icons like Miles Davis and Eartha Kitt as she coos and commands through each namesake cut, sparking flames for the bluesy rap groove of “MUDDY” and giving flowers to a legend on the electro-laced funk of “OCTAVIA.”

In the clip of an older Eartha Kitt that everyone kicks around the internet, her cheekbones are still as pronounced as many would remember them from her glory days on Broadway, and her eyes are still piercing and inviting. She sips from a metal cup. The wind blows the flowers behind her until those flowers crane their stems toward her face, and the petals tilt upward, forcing out a smile. A dog barks in the background. In the best part of the clip, Kitt throws her head back and feigns a large, sky-rattling laugh upon being asked by her interviewer whether or not she’d compromise parts of herself if a man came into her life. When the laugh dies down, Kitt insists on the same, rhetorical statement. “Compromise!?!?” she flings. “For what?” She repeats “For what?” until it grows more fierce, more unanswerable. Until it holds the very answer itself. On the hook to the song “Eartha,” Jamila Woods sings “I don’t want to compromise / can we make it through the night” and as an album, Legacy! Legacy! stakes itself on the uncompromising nature of its creator, and the histories honored within its many layers. There is a lot of talk about black people in America and lineage, and who will tell the stories of our ancestors and their ancestors and the ones before them. But there is significantly less talk about the actions taken to uphold that lineage in a country obsessed with forgetting. There are hands who built the corners of ourselves we love most, and it is good to shout something sweet at those hands from time to time. Woods, a Chicago-born poet, organizer, and consistent glory merchant, seeks to honor black people first, always. And so, Legacy! Legacy! A song for Zora! Zora, who gave so much to a culture before she died alone and longing. A song for Octavia and her huge and savage conscience! A song for Miles! One for Jean-Michel and one for my man Jimmy Baldwin! More than just giving the song titles the names of historical black and brown icons of literature, art, and music, Jamila Woods builds a sonic and lyrical monument to the various modes of how these icons tried to push beyond the margins a country had assigned to them. On “Sun Ra,” Woods sings “I just gotta get away from this earth, man / this marble was doomed from the start” and that type of dreaming and vision honors not only the legacy of Sun Ra, but the idea that there is a better future, and in it, there will still be black people. Jamila Woods has a voice and lyrical sensibility that transcends generations, and so it makes sense to have this lush and layered album that bounces seamlessly from one sonic aesthetic to another. This was the case on 2016’s HEAVN, which found Woods hopeful and exploratory, looking along the edges resilience and exhaustion for some measures of joy. Legacy! Legacy! is the logical conclusion to that looking. From the airy boom-bap of “Giovanni” to the psychedelic flourishes of “Sonia,” the instrument which ties the musical threads together is the ability of Woods to find her pockets in the waves of instrumentation, stretching syllables and vowels over the harmony of noise until each puzzle piece has a home. The whimsical and malleable nature of sonic delights also grants a path for collaborators to flourish: the sparkling flows of Nitty Scott on “Sonia” and Saba on “Basquiat,” or the bloom of Nico Segal’s horns on “Baldwin.” Soul music did not just appear in America, and soul does not just mean music. Rather, soul is what gold can be dug from the depths of ruin, and refashioned by those who have true vision. True soul lives in the pages of a worn novel that no one talks about anymore, or a painting that sits in a gallery for a while but then in an attic forever. Soul is all the things a country tries to force itself into forgetting. Soul is all of those things come back to claim what is theirs. Jamila Woods is a singular soul singer who, in voice, holds the rhetorical demand. The knowing that there is no compromise for someone with vision this endless. That the revolution must take many forms, and it sometimes starts with songs like these. Songs that feel like the sun on your face and the wind pushing flowers against your back while you kick your head to the heavens and laugh at how foolish the world seems.

A successful child actor turned indie-rock sweetheart with Rilo Kiley, a solo artist beloved by the famed and famous, Jenny Lewis would appear to have led a gilded life. But her truth—and there have been intimations both in song lyrics and occasionally in interviews—is of a far darker inheritance. “I come from working-class showbiz people who ended up in jail, on drugs, both, or worse,” Lewis tells Apple Music. “I grew up in a pretty crazy, unhealthy environment, but I somehow managed to survive.” The death of her mother in 2017 (with whom she had reconnected after a 20-year estrangement) and the end of her 12-year relationship with fellow singer-songwriter Johnathan Rice set the stage for Lewis’ fourth solo album, where she finally reconciles her public and private self. A bountiful pop record about sex, drugs, death, and regret, with references to everyone from Elliott Smith to Meryl Streep, *On the Line* is the Lewis aesthetic writ large: an autobiographical picaresque burnished by her dark sense of humor. Here, Lewis takes us through the album track by track. **“Heads Gonna Roll”** “I’m a big boxing fan, and I basically wanted to write a boxing ballad. There’s a line about ‘the nuns of Harlem\'—that’s for real. I met a priest backstage at a Dead & Company show in a cloud of pot smoke. He was a fan of my music, and we struck up a conversation and a correspondence. I’d just moved to New York at the time and was looking to do some service work. And so this priest hooked me up with the nuns in Harlem. I would go up there and get really stoned and hang out with theses nuns, who were the purest, most lovely people, and help them put together meal packages. The nuns of Harlem really helped me out.” **“Wasted Youth”** “For me, the thing that really brings this song, and the whole record, together is the people playing on it. \[Drummer\] Jim Keltner especially. He’s played on so many incredible records, he’s the heartbeat of rock and roll and you don’t even realize it. Jim and Don Was were there for so much of this record, and they were the ones that brought Ringo Starr into the sessions—playing with him was just surreal. Benmont Tench is someone I’d worked with before—he’s just so good at referencing things from the past but playing something that sounds modern and new at the same time. He created these sounds that were so melodic and weird, using the Hammond organ and a bunch of pedals. We call that ‘the fog’—Benmont adds the fog.” **“Red Bull & Hennessy”** “I was writing this song, almost predicting the breakup with my longtime partner, while he was in the room. I originally wanted to call it ‘Spark,’ ’cause when that spark goes out in a relationship it’s really hard to get it back.” **“Hollywood Lawn”** “I had this for years and recorded three or four different versions; I did a version with three female vocalists a cappella. Then I went to Jamaica with Savannah and Jimmy Buffett—I actually wrote some songs with Jimmy for the *Escape to Margaritaville* musical that didn’t get used. We didn’t use that version, but I really arranged the s\*\*\* out of it there, and some of the lyrics are about that experience.” **“Do Si Do”** “Wrote this for a friend who went off his psych meds abruptly, which is so dangerous—you have to taper off. I asked Beck to produce it for a reason: He gets in there and wants to add and change chords. And whatever he suggests is always right, of course. That’s a good thing to remember in life: Beck is always right.” “Dogwood” “This is my favorite song on the record. I wrote it on the piano even though I don’t think I’m a very good piano player. I probably should learn more, but I’m just using the instrument as a way to get the song out. This was a live vocal, too. When I’m playing and singing at the same time, I’m approaching the material more as a songwriter rather than a singer, and that changes the whole dynamic in a good way.” **“Party Clown”** “I’d have to describe this as a Faustian love song set at South by Southwest. There’s a line in there where I say, ‘Can you be my puzzle piece, baby?/When I cry like Meryl Streep?’ It’s funny, because Meryl actually did a song of mine, ‘Cold One,’ in *Ricki and the Flash*.” **“Little White Dove”** “Toward the end of the record, I would write songs at home and then visit my mom in the hospital when she was sick. I started this on bass, had the chord structure down, and wrote it at the pace it took to walk from the hospital elevator to the end of the hall. I was able to sing my mom the chorus before she passed.” **“Taffy”** “That one started out as a poem I’d written on an airplane, then it turned into a song. It’s a very specific account of a weekend spent in Wisconsin, and there are some deep Wisconsin references in there. I’m not interested in platitudes, either as a writer or especially as a listener. I want to hear details. That’s why I like hip-hop so much. All those details, names that I haven’t heard, words that have meanings that I don’t understand and have to look up later. I’m interested in those kinds of specifics. That’s also what I love about Bob Dylan songs, too—they’re very, very specific. You can paint an incredibly vivid picture or set a scene or really project a feeling that way.” **“On the Line”** “This is an important song for me. If you read the credits on this record, it says, ‘All songs by Jenny Lewis.’ Being in a band like Rilo Kiley was all about surrendering yourself to the group. And then working with Johnathan for so long, I might have lost a little bit of myself in being a collaborator. It’s nice to know I can create something that’s totally my own. I feel like this got me back to that place.” **“Rabbit Hole”** “The record was supposed to end with ‘On the Line’—the dial tone that closes the song was supposed to be the last thing you hear. But I needed to write ‘Rabbit Hole,’ almost as a mantra for myself: ‘I’m not gonna go/Down the rabbit hole with you.’ I figured the song would be for my next project, but I played it for Beck and he insisted that we put it on this record. It almost feels like a perfect postscript to this whole period of my life.”

You’d think that an artist making her first solo album after nearly 40 years of collaborative work would fall for at least a few pitfalls of sentimentality—the glance in the rearview, the meditation on middle age, the warmth of accomplishment, whatever. Then again, Kim Gordon was never much for soft landings. Noisy, vibrant, and alive with the kind of fragmented poetry that made her presence in Sonic Youth so special, *No Home Record* feels, above all, like a debut—a new voice clocking in for the first time, testing waters, stretching her capacity. The wit is classic (“Airbnb/Could set me free!” she wails on “Air BnB,” channeling the misplaced passions of understimulated yuppies worldwide), as is the vacant sex appeal (“Touch your nipple/You’re so fine!” she wails on “Hungry Baby,” channeling the…misplaced passions of understimulated yuppies worldwide). Most surprising is how informed the album is by electronic music (“Don’t Play It”) and hip-hop (“Paprika Pony,” “Sketch Artist”)—a shift that breaks with the free-rock-saviordom that Sonic Youth always represented while maintaining the continuity of experimentation that made Gordon a pioneer in the first place.

With a career spanning nearly four decades, Kim Gordon is one of the most prolific and visionary artists working today. A co-founder of the legendary Sonic Youth, Gordon has performed all over the world, collaborating with many of music’s most exciting figures including Tony Conrad, Ikue Mori, Julie Cafritz and Stephen Malkmus. Most recently, Gordon has been hitting the road with Body/Head, her spellbinding partnership with artist and musician Bill Nace. Despite the exhaustive nature of her résumé, the most reliable aspect of Gordon’s music may be its resistance to formula. Songs discover themselves as they unspool, each one performing a test of the medium’s possibilities and limits. Her command is astonishing, but Gordon’s artistic curiosity remains the guiding force behind her music. It makes sense that this “American idea” (as Gordon says on the agitated rock track “Air BnB”) of purchasing utopia permeates the record, as no place is this phenomenon more apparent than Los Angeles, where Gordon was born and recently returned to after several lifetimes on the east coast. It was a move precipitated by a number of seismic shifts in her personal life and undoubtedly plays a role in No Home Record’s fascination with transience. The album opens with the restless “Sketch Artist,” where Gordon sings about “dreaming in a tent” as the music shutters and skips like scenery through a car window. “Even Earthquake,” perhaps the record’s most straightforward track embodies this mood; Gordon’s voice wavering like watercolor: “If I could cry and shake for you / I’d lay awake for you / I got sand in my heart for you,” guitar strokes blending into one another as they bleed out across an unstable page. Front to back, No Home Record is an expert operation in the uncanny. You don’t simply listen to Gordon’s music; you experience it.

Part of the fun of listening to Lana Del Rey’s ethereal lullabies is the sly sense of humor that brings them back down to earth. Tucked inside her dreamscapes about Hollywood and the Hamptons are reminders—and celebrations—of just how empty these places can be. Here, on her sixth album, she fixes her gaze on another place primed for exploration: the art world. Winking and vivid, *Norman F\*\*\*\*\*g Rockwell!* is a conceptual riff on the rules that govern integrity and authenticity from an artist who has made a career out of breaking them. In a 2018 interview with Apple Music\'s Zane Lowe, Del Rey said working with songwriter Jack Antonoff (who produced the album along with Rick Nowels and Andrew Watt) put her in a lighter mood: “He was so *funny*,” she said. Their partnership—as seen on the title track, a study of inflated egos—allowed her to take her subjects less seriously. \"It\'s about this guy who is such a genius artist, but he thinks he’s the shit and he knows it,” she said. \"So often I end up with these creative types. They just go on and on about themselves and I\'m like, \'Yeah, yeah.\' But there’s merit to it also—they are so good.” This paradox becomes a theme on *Rockwell*, a canvas upon which she paints with sincerity and satire and challenges you to spot the difference. (On “The Next Best American Record,” she sings, “We were so obsessed with writing the next best American record/’Cause we were just that good/It was just that good.”) Whether she’s wistfully nostalgic or jaded and detached is up for interpretation—really, everything is. The album’s finale, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have - but I have it,” is packaged like a confessional—first-person, reflective, sung over simple piano chords—but it’s also flamboyantly cinematic, interweaving references to Sylvia Plath and Slim Aarons with anecdotes from Del Rey\'s own life to make us question, again, what\'s real. When she repeats the phrase “a woman like me,” it feels like a taunt; she’s spent the last decade mixing personas—outcast and pop idol, debutante and witch, pinup girl and poet, sinner and saint—ostensibly in an effort to render them all moot. Here, she suggests something even bolder: that the only thing more dangerous than a complicated woman is one who refuses to give up.

Moved by the warm response to 2016’s *You Want It Darker*, released three weeks before his death, Leonard Cohen left his son with instructions to finish those songs they’d started together, using vocal recordings he was leaving behind. In an act of devotion—to his father, to song—Adam wrote and recorded arrangements for each, as he thought Leonard would have wanted to hear them. The result is *Thanks for the Dance*, a posthumous album of unreleased material that’s as loving and respectful as they come. “This was not meant to be about me,” Adam tells Apple Music. “I didn’t make choices that were a reflection of my taste—the exercise was to try to make choices that were a reflection of his. It’s this advantage that I have over much greater and more accomplished producers: They don’t know what he hates. I do.” Here, he tells us the story behind each track and highlights some of his favorite lines. **Happens to the Heart** “Anyone who knew Leonard Cohen at the end of his life knew that there was one song he was obsessively and compulsively writing and trying to perfect, and that was ‘Happens to the Heart.’ He was hell-bent—or heaven-bent—on completing it, and we just were unable to get a musical accompaniment that he was satisfied with. I think it\'s one in a long line of songs that have his essential thesis in life, which is the broken hallelujah: Everything cracks, and this is what happens to the heart. I had this incredible vocal that was so meaningful to him. It was a way to keep him with me, a way to sit with him—there\'s the emotional part, but more important to me than anything was just getting it right. The first task was to parse through all of the verses and assemble a vocal based on his last approved version of what the poem was going to be, and set that to chordal language that would make sense to a Leonard Cohen listener.” **Moving On** “His notion for the song was that he would repeat the same verse over and over and over again almost as a meditation. Every time we tried, it failed by his own estimation. So I had some very compelling vocals from him and the trick was to then go back to the essence, bring back the Eastern sound of the tremolo—in this case a concert mandolin player by the name of Avi Avital—and Javier Mas on his Spanish nylon string guitar, in my backyard in Los Angeles. ‘As if there ever was a you’ is the line that kills me. The whole thing feels like this nostalgic dream. When we were recording the vocal, he had just got news that Marianne \[Ihlen\] had passed away. And in recording the vocals I really did feel like he was channeling and correcting lyrics to have the song be a postscript to ‘So Long, Marianne.’ It\'s something that we had discussed while we were recording and it informed my wanting to exaggerate the Mediterranean romance of the song.” **The Night of Santiago** “‘Night of Santiago’ was always one of my favorite poems that my father had written, which is actually based on a Federico García Lorca poem that he adapted. I\'d heard it under construction for years, on the front lawn or while we were having coffee or dinner, and I\'d always begged him to attempt to write music to it. In a weakened state, he said, ‘Look, I\'ll just recite the poem to a certain tempo and you go ahead and you write the music and try to tell the story.’ And it was really, really fun to work with it. It has such voluptuous language. The song was mostly recorded in Spain, with Sílvia Pérez Cruz from Barcelona and Javier Mas and Carlos de Jacoba, to give it that flamenco twist—we very much tried to capture a kind of whimsy. When we got back to LA, Beck came over to put some Jew’s harp in the verses and laid the guitar down just to give it an extra layer of cinema.” **Thanks for the Dance** “He tried to get a version of it on *Old Ideas* and *Popular Problems*, and on *You Want It Darker*. He’d been even trying to figure out his way of doing that song for years, and I think that he would have been incredibly pleased with this particular version. It was meant to evoke things like \'Dance Me to the End of Love\' and \'Hallelujah.\' It has a certain strain of lightness and cheekiness that some of his work has: \'Stop at the surface, the surface is fine.\' To have that kind of resignation but humor really does encapsulate where his mind was at the end. Jennifer Warnes, his longtime vocal partner, came to my backyard and sang on that. When we completed it, we knew we had the record. There was something about the invocation of that union, between the feminine voice and my father’s low baritone—it just touches a nerve and makes you feel like you\'ve heard the song before. There was this sense that *You Want It Darker* had a kind of gravity and darkness, and this offering has a softer, flower-pushing-up quality and romance to it.” **It’s Torn** “‘Torn’ was started a decade ago with Sharon Robinson—with whom he had written many songs and with whom he toured—but it really took a hold in Berlin with concert pianist and composer Dustin O\'Halloran. It has chord signatures borrowed from my father’s song from decades earlier ‘Avalanche.’ Again, it\'s this incredible thesis of brokenness that he has, this consistent message, this toying with the imperfection of life: ‘It\'s torn where there\'s beauty, it\'s torn where there\'s death/It\'s torn where there\'s mercy, but torn somewhat less,’ he says. ‘It\'s torn in the highest, from kingdom to crown/The messages fly but the network is down/Bruised at the shoulder and cut at the wrist/The sea rushes home to its thimble of mist/The opposites falter, the spirals reverse/And Eve must re-enter the sleep of her birth.’ I mean, this is pseudo-biblical. I’ve never heard that from any other songwriter, not even Dylan. It\'s just so composed. It’s like King David.” **The Goal** “‘The Goal’ might be my favorite piece on the album. The zinger is at the end: ‘No one to follow and nothing to teach/Except that the goal falls short of the reach.’ That\'s an incredible line to ponder, and it very much resembles the condition that he was in at the end, where he\'d sit in his chair, look at life go by, and have and share these incredibly profound and generous thoughts. The music around his reading brings to life the humor and the emotion—the swelling and the sparseness of what I imagined to be his own emotional state. The most stirring thing that people say over and over after listening to these songs is how they feel Leonard Cohen is still among us, he\'s still alive. And this song has that quality in a powerful dose. The reading is almost thespian-like, it is so present. He was speaking from the other side for sure.” **Puppets** “Another poem that we discussed for years—or, at least, for years he heard my disappointment with the fact that it had never been turned into song. He would chuckle and say, ‘Well, write something that makes sense musically around it, and I\'d consider it.’ There is a ferocious boldness to the lyric and to the position of the narrator. And there\'s a kind of steely, church-like quality to the arrangement. The lyric: ‘German puppets burned the Jews/Jewish puppets did not choose.’ To open a song that way is frighteningly bold, so the arrangement needed to be robust. And there\'s this otherworldliness going through the entire thing. We recorded this German choir in Berlin, and then funny enough we ended up going to Montreal, to get the Jewish men\'s choir that played such an important role on *You Want It Darker*. And so there\'s literally a choir of Germans and a choir of Jews on the song blending together. The trick was to create something with as much evocation without going into sentimentality.” **The Hills** “‘Triumphant’ is a wonderful word to describe it, in the narrator’s semi-comical declaration he can\'t make the hills, one of the wonderful paradoxes of all of our existences. There’s a sort of *Secret Life of Walter Mitty* quality to this one, and at the same time it\'s the voyage—it’s what you wanted versus what you got. There\'s something stark and resigned and yet not woeful about it, which allows for this grandiose, classic feeling while at the same time being fresh and modern. Patrick Watson, who\'s one of my favorite recording artists, lent a great deal of work with horns and vocal arrangements. It\'s the only song on the record that\'s co-produced by anybody.” **Listen to the Hummingbird** “The last thing we recorded. We were struggling at the time, because we had an eight-song record and it just felt shy—we knew we needed another one. We were in Berlin and Justin Vernon from Bon Iver was in the studio next door to ours, making these incredible, really emotional, stirring sounds. And there was something about the mood that was so captivating and inspiring that it reminded me of my father’s last press conference. It was the last time he ever spoke in public, a press junket for *You Want It Darker*. Unprompted, he said, ‘Do you want to hear a new poem?’ And he recited it, into this cheap microphone in a conference room. I asked Sony for the audio, recuperated it, set it to be metronomically correct, and composed this piece of music with those atmospheric sounds from Bon Iver coming through our shared wall in Berlin. That\'s how we got it.”

Lightning Bolt play with abandon that is unmatched and remarkably undiluted since the duo’s formation 25 years ago. They are often called one of the loudest rock outfits in existence, both on record and on (or famously, off) the stage. Brian Gibson creates sounds that are unexpected and remarkably varied with his virtuosic bass playing and his inventive approach to the instrument, centered around melody rather than rhythm. The dizzying fury of Brian Chippendale’s drums twist from primal patterns into disorienting break beats as his distorted, looped, and echoing vocals weave more melody into the mayhem. Amidst the fray there has always been shreds of a pop songs discernible in the eye of every Lightning Bolt song. For their seventh full length, Sonic Citadel, Gibson and Chippendale have done the daring, stripping away some of the distortion mask to reveal the naked pop forms as never before. Their relentless energy, inventiveness and, unrestrained joy still drive their songs, pulling you in and compelling you to bounce and yes, even sing along. Over their career Lightning Bolt’s incomparable sound has been built on the ebb and flow between the power of raw, unbridled simplicity and a boundless, childlike sense of wonder. Sonic Citadel marks the duo’s most varied and diverse work since their seminal album Wonderful Rainbow, exploring a large breadth of emotions between and within each song. Gibson and Chippendale again recorded with the esteemed Machines With Magnets to capture the abandon of their music with clarity and Gibson’s incredible dynamic range clearly to make the record as visceral an experience as their live performances. The pummeling “Blow To The Head” and swirling “Van Halen 2049” bookend the album with two of the most ferocious songs in the band’s catalogue, with the former built as a Black Pus (Brian Chippendale’s solo outlet) track on steroids. In stark contrast, songs like “Don Henley In The Park,” and “All Insane” take on almost conventional pop shapes despite being entirely spontaneous pieces crafted in the studio. “Hüsker Dön’t” too defies expectations as one of the poppiest songs in their discography with a chugging but clear chord progression and some of Chippendale’s least distorted vocals. These wildly varying approaches are a testament to the duo’s immeasurable capacity to explore new sonic territory organically, and largely through improvisation. For the bulk of Lightning Bolt’s work together, they have slowly molded improvised jams which sometimes take years to develop on the road. The song “Halloween 3” may sound familiar to fans who have seen the band live in the last 15 years, and is named after a popular video of the duo performing an early version of the song. Sonic Citadel, however, also prominently features songs which began as solo recordings, be it a Black Pus 4-track recording or a series of looped bass figures from Gibson. In the four years between album releases, each member’s increasingly prolific creative endeavors limited their time to create together. Brian Gibson was the sole artist, musician and co-designer of the acclaimed video game Thumper, which has since proliferated across a multitude of platforms, and won countless awards including the 2019 Apple Design Award. Brian Chippendale, who has always created the band’s visual art, released the graphic novel Puke Force, was included in Rolling Stone’s “100 Greatest Drummers of All Time,” and recently collaborated with fashion designers Eckhaus Latta. Coupled with their consistent touring, as well as Chippendale recently becoming a father, the duo took the challenge of their time constraints head on as a compositional tool. By keeping some songs more direct and focusing on their central ideas, the duo managed to increase the overall intensity of their music while leaving space to for the songs to breath and stretch out live. The impact that Lightning Bolt has had on underground music since its inception is immense, and remains pervasive beyond any genre tag that has been attached to them. Sonic Citadel is the work of band unafraid to challenge themselves, unbound by expectations, joyfully defiant, and possessed of the same inventive curiosity which set them apart on day one and is unmatched still 25 years later.

To put it mildly, San Diego-based artist Kristin Hayter’s second album under the Lingua Ignota name is not for the faint of heart. (Her first, it’s maybe worth noting, is called *All Bitches Die*.) A dark communion of neoclassical strings, industrial atmospherics, and Hayter’s classically trained vibrato, *Caligula* is an arresting meditation on abuse, recovery, and revenge. The opening “Faithful Servant Friend of Christ” sets the album’s tone early, showcasing both Hayter’s stirring vocal range and the complex religious themes that underpin most songs. On the funereal “Do You Doubt Me Traitor,” she sharpens her lyrics into weapons, even enlisting the Devil himself as an ally in her personal war against her abuser and herself (“I don’t eat/I don’t sleep/I let it consume me/How do I break you/Before you break me?”). This is not an uplifting journey through trauma to peace, however—the strangled wails and purgative screams of “Butcher of the World” and “Day of Tears and Mourning” speak to a catharsis without resolution or relief, only riddance. It’s an exhilarating, intense, apocalyptic jeremiad told with disarming honesty and starkness.

“CALIGULA”, the new album from LINGUA IGNOTA set for release on July 19th on CD/2xLP/Digital through Profound Lore Records, takes the vision of Kristin Hayter’s vessel to a new level of grandeur, her purging and vengeful audial vision going beyond anything preceding it and reaching a new unparalleled sonic plane within her oeuvre. Succeeding her self-released 2017 “All Bitches Die” opus (re-released by Profound Lore Records in 2018), “CALIGULA” sees Hayter design her most ambitious work to date, displaying the full force of her talent as a vocalist, composer, and storyteller. Vast in scope and multivalent in its influences, with delivery nothing short of demonic, “CALIGULA” is an outsider’s opera; magnificent, hideous, and raw. Eschewing and disavowing genre altogether, Hayter builds her own world. Here she fully embodies the moniker Lingua Ignota, from the German mystic Hildegard of Bingen, meaning “unknown language” — this music has no home, any precedent or comparison could only be uneasily given, and there is nothing else like it in our contemporary realm. LINGUA IGNOTA has always taken a radical, unflinching approach to themes of violence and vengeance, and “CALIGULA” builds on the transformation of the survivor at the core of this narrative. “CALIGULA” embraces the darkness that closes in, sharpens itself with the cruelty it has been subjected to, betrays as it has been betrayed. It is wrath unleashed, scathing, a caustic blood-letting: “Let them hate me so long as they fear me,” Hayter snarls in a voice that ricochets from chilling raw power to agonizing vulnerability. Whilst “CALIGULA” is unapologetically personal and critically self-aware, there are broader themes explored; the decadence, corruption, depravity and senseless violence of emperor Caligula is well documented and yet still permeates today. Brimming with references and sly jabs, Hayter’s sardonic commentary on abuse of power and invalidation is deftly woven. Working closely with Seth Manchester at Machines With Magnets studio in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Hayter strips away much of the industrial and electronic elements of her previous work, approaching instead the corporeal intensity and intimate menace of her notorious live performances, achieved with unconventional recording techniques and sound sources, as well as a full arsenal of live instrumentation and collaborators including harsh noise master Sam McKinlay (THE RITA), visceral drummer Lee Buford (The Body) and frenetic percussionist Ted Byrnes (Cackle Car, Wood & Metal), with guest vocals from Dylan Walker (Full of Hell), Mike Berdan (Uniform), and Noraa Kaplan (Visibilities). “CALIGULA” is a massive work, a multi-layered epic that gives voice and space to that which has been silenced and cut out.

HEY USA! Our friends at Bloodshot are working with the Mekons to distribute Deserted in USA to insure shipping is as affordable as possible. Head over to the album page linked below. Thanks! Glitterbeat mekons.bandcamp.com “There's never been a band quite like the Mekons. Unmarred by breakups or breakouts, undefined by genre, geography, or ego-trips…no rock outfit's ever been this committed to behaving like a true band, with all the equanimity and familial bonding implied.” – Rolling Stone This legendary group from Leeds, have written contemporary music history for the last 40 years as radical innovators of both first generation punk and insurgent roots music. Their new album was recorded in the desert environs of Joshua Tree, California and is drenched with widescreen, barbed-wire atmosphere and hard-earned (but ever amused) defiance. The return of one of the planet’s most essential rock & roll bands. When punk exploded in London, fast and brash and full of fury, up in Leeds the Mekons came blinking into the light at a much slower pace. Singles like “Where Were You” and “Never Been in a Riot” (both from1978) fractured punk’s outlaw myth with the ordinariness of real life. During the next decade, as country singers donned cowboy hats and slid into the stadiums, the Mekons celebrated the music’s rough, raw beginnings and tender hearts with the Fear and Whiskey album (1985) and went on to demolish rock narratives with Mekons Rock’n’Roll (1989). For more than four decades they’ve been a constant contradiction, an ongoing art project of observation, anger and compassion, all neatly summed up in the movie Revenge of the Mekons, which has ironically brought an upsurge in their popularity around the US as new audiences discovers their shambling splendour. And now the caravan continues with Deserted, their first full studio album in eight years. And desert is an apt word. This time there’s an emphasis on texture and sounds, a sense of space that brings a new, widescreen feel to their music, opening up songs that surge like clarion calls, like the album’s opening track, “Lawrence of California.” “We were recording at the studio of our bass player, Dave Trumfio,” Langford recalls. “It’s just outside Joshua Tree National Park. Seeing Tom [Greenhalgh, the group’s other original member] wandering in that landscape looked like a scene from Lawrence of California.’ And then, ‘Wait a minute, there’s a song in that.’” The band arrived with no songs written, only a few ideas exchanged by email between Langford and Tom Greenhalgh, the group’s other original member. “Things emerged. At one point we had a sheet with a few words written here and there. Everyone added bits and by the time it was finished, it only needed a few changes to be able to sing. Somewhere else there are two lyrics sung over each other.” Five days of brilliant chaos let their thoughts run free, from the almost-folk wonder of “How Many Stars” and the wide open space of “In The Desert,” to the oblique strangeness of “Harar 1883,” a song about French poet Arthur Rimbaud’s time in Ethiopia, inspired by photographs Greenhalgh has of the period. And then there’s “Weimar Vending Machine.” “That starts off about Iggy Pop in Berlin,” Langford explains. “There’s a story that he went to a vending machine and saw the word ‘sand’. He put his money in and a bag of sand came out.” It’s a gloriously unlikely, cinematic image to use as a springboard into the album’s longest song, a piece that shifts between darkness and joy, powered by Rico Bell’s piano and Sally Timms’s clarion voice. It’s one to provoke thought and questions, but that’s hardly unusual for the band. They’ve always revelled in the surreal and the bizarre. What stands out on Deserted, though, is the space and clarity in the sound, with Susie Honeyman’s violin taking a more prominent role on a couple of the tracks. “Susie’s wonderful,” Langford says. “You play something to her, she thinks for a minute them comes out with this haunting Highland beauty.” Even the impromptu instrumental sessions find their way into the record, sometimes transformed and spacy to add texture to a song, elsewhere simply allowed to float free and form the tail to “After The Rain,” the album’s closer. The studio itself becomes an instrument here, and much of that is down to Trumfio, whose production credits at his Kingsize Soundlabs include Wilco and the Pretty Things. “Even during the mixing, Dave pushed us into some new sonic territory all the way through,” Langford recalls. The tweaking and effects take them about as far as they can go from 2016’s Existentialism, which saw all eight members crowded around a single microphone in a tiny theatre in Red Hook, New York, recording live in front of an audience. Deserted offers a different kind of freedom. Of space and stars and wide-open land. Of possibilities and past. But mainly of the future. It’s fresh territory. But that’s always been what attracts the Mekons. They show that four decades doesn’t translate to becoming a heritage act. Instead, they keep experimenting, from the jagged, spaced throb that powers “Into The Sun,” revolving around the drums of Steve Goulding and Trumfio’s bass to the barely controlled anarchy that’s “Mirage,” or a countrified homage to “Andromeda.” Everything is possible, everything is permitted. 41 years after that first single they’re still moving. Still defiant, still laughing, still joyful. Never underestimate some happy anarchy, and never write off the Mekons. Deserted, perhaps, but they’re back to tip the world on its axis. Again.

In the middle of writing her seventh album *Wildcard*, Miranda Lambert hit pause. “I took the first long stretch I’ve ever had off in my entire career since I was 17,” she tells Apple Music. “Finally you realize how much you need a breath.” During that break, the country superstar made some big life changes, surprising the world by announcing that she’d secretly gotten married and was moving part-time to New York City—a switch-up that she says revitalized her creative energy and breathed new life into her sound. “Oddly enough, on my seventh solo album, I feel like I approached it more like my first album than any other record I’ve made,” she says. In many ways, *Wildcard* feels like a new beginning. It’s full of frenetic, uptempo rock (“Locomotive”), propulsive power pop (“Mess With My Head\"), and clear-eyed confidence (“It All Comes Out in the Wash”). The newfound edge is partly a reflection of producer Jay Joyce (Eric Church, Zac Brown Band), with whom she works for the first time here after years with Frank Liddell. Lambert says it was time to mix it up: “Country is what I do, it’s who I am…but I love rock ’n’ roll.” Her country devotees will delight in “Way Too Pretty for Prison,” a deliciously clever breakup song in which Lambert and Maren Morris fantasize about killing an ex before ultimately deciding prison sounds unappealing (not enough boys, beauty parlors, or Chardonnay). And on “Pretty Bitchin’,” a similarly rowdy send-up, she rolls out a series of flexes—fine wine, a new guitar, a kitted-out Airstream—and makes no apologies about relishing her success in a world that is often unkind to women entertainers. “I use what I got/I don’t let it go to waste,” she sings with the remorseless air of someone who has endured their fair share of tabloid headlines. This song is about winning in spite of all that: \"I’m pretty from the back/Kinda pretty in the face/I hate to admit it/But it didn’t stop me, did it?”

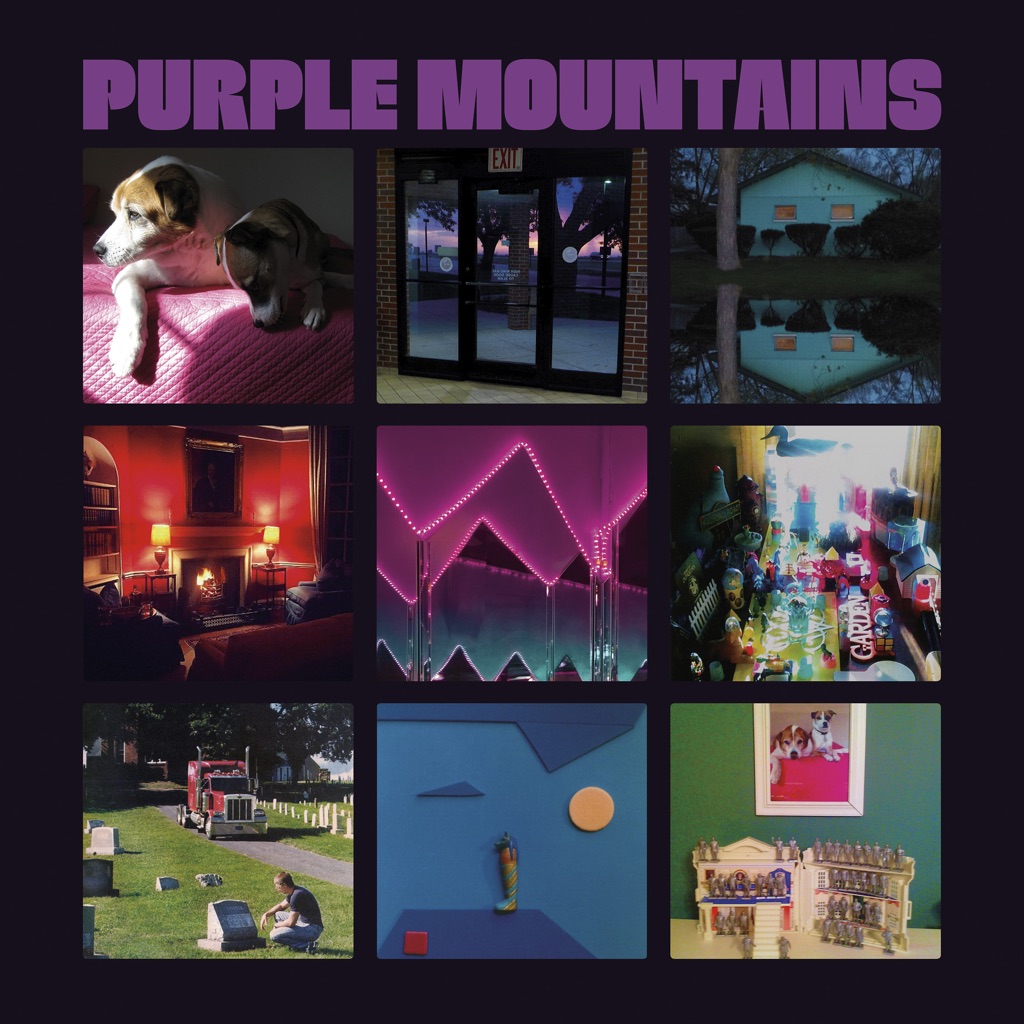

When David Berman disbanded Silver Jews in 2009, the world stood to lose one of the best writers in indie rock, a guy who catalogued the magic and misery of everyday life with wit, heart, and the ragged glory of the occupationally down-and-out. After a 10-year break professedly spent reading books and arguing with people on Reddit, Berman enlisted members of the Brooklyn band Woods to back him on *Purple Mountains*. Berman’s pain had never been laid quite so bare, nor had it ever sounded quite so urgent. “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion,” he sings on the swaggering “That’s Just the Way I Feel.” “Day to day, I’m neck and neck with giving in.” And “Margaritas at the Mall” turns an ordinary happy hour into a jeremiad about the cold comforts of capitalism in a godless world. That the music—country-tinged indie rock—was as polished and competent as it was only highlighted Berman’s intensity: less a rock singer than a street preacher, someone who needed to avail himself of his visions stat. But even at his most desperate, he remained achingly funny, turning statements of existential loneliness into the kind of bumper sticker Zen that made him seem like an ordinary guy no matter how highfalutin he could get. “Well, if no one’s fond of fuckin’ me, maybe no one’s fuckin’ fond of me,” he sings on the album-closing “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” sounding not all that far off from the George Strait one-twos he reportedly loved. Above all, though, his writing is beautiful, attuned to detail in ways that make ordinary scenarios shimmer with quiet magic. Just listen to “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan,” which turns a quiet night in a big city into an allegory of finding solace in the weather of what comes to us. Shortly after the release of *Purple Mountains*, Berman died, at the age of 52, a tragic end to what felt like a triumphant return. “The dead know what they\'re doing when they leave this world behind,” he sings on “Nights That Won’t Happen.” “When the here and the hereafter momentarily align.”

David Berman comes in from the cold after ten long years. His new musical expression is a meltdown unparalleled in modern memory. He warns us that his findings might be candid, but as long as his punishment comes in such bite-sized delights of all-American jukebox fare, we'll hike the Purple Mountains with pleasure forever.