Slant Magazine's 25 Best Albums of 2019

The more borders you cross, the more potential for discovery—and 2019, as eclectic a year as any, has demonstrated that.

Published: December 12, 2019 17:05

Source

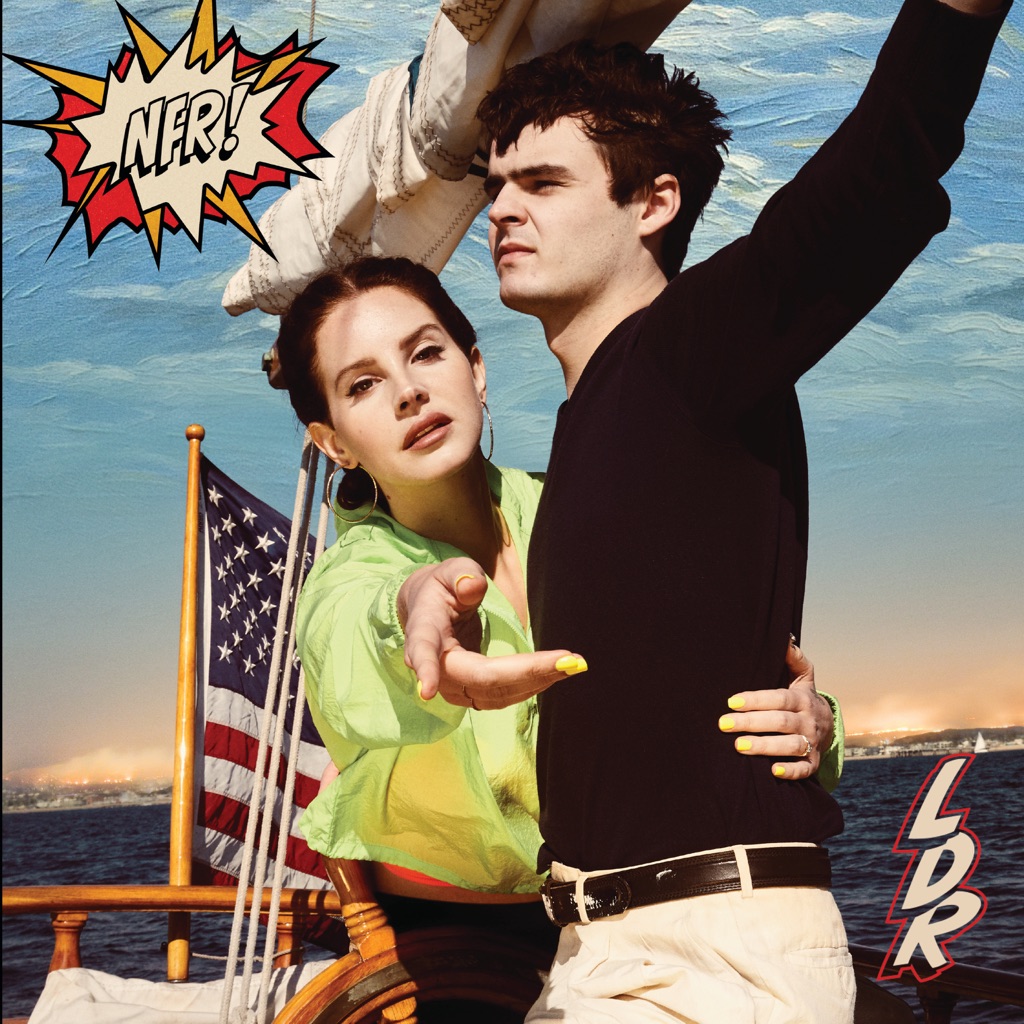

Part of the fun of listening to Lana Del Rey’s ethereal lullabies is the sly sense of humor that brings them back down to earth. Tucked inside her dreamscapes about Hollywood and the Hamptons are reminders—and celebrations—of just how empty these places can be. Here, on her sixth album, she fixes her gaze on another place primed for exploration: the art world. Winking and vivid, *Norman F\*\*\*\*\*g Rockwell!* is a conceptual riff on the rules that govern integrity and authenticity from an artist who has made a career out of breaking them. In a 2018 interview with Apple Music\'s Zane Lowe, Del Rey said working with songwriter Jack Antonoff (who produced the album along with Rick Nowels and Andrew Watt) put her in a lighter mood: “He was so *funny*,” she said. Their partnership—as seen on the title track, a study of inflated egos—allowed her to take her subjects less seriously. \"It\'s about this guy who is such a genius artist, but he thinks he’s the shit and he knows it,” she said. \"So often I end up with these creative types. They just go on and on about themselves and I\'m like, \'Yeah, yeah.\' But there’s merit to it also—they are so good.” This paradox becomes a theme on *Rockwell*, a canvas upon which she paints with sincerity and satire and challenges you to spot the difference. (On “The Next Best American Record,” she sings, “We were so obsessed with writing the next best American record/’Cause we were just that good/It was just that good.”) Whether she’s wistfully nostalgic or jaded and detached is up for interpretation—really, everything is. The album’s finale, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have - but I have it,” is packaged like a confessional—first-person, reflective, sung over simple piano chords—but it’s also flamboyantly cinematic, interweaving references to Sylvia Plath and Slim Aarons with anecdotes from Del Rey\'s own life to make us question, again, what\'s real. When she repeats the phrase “a woman like me,” it feels like a taunt; she’s spent the last decade mixing personas—outcast and pop idol, debutante and witch, pinup girl and poet, sinner and saint—ostensibly in an effort to render them all moot. Here, she suggests something even bolder: that the only thing more dangerous than a complicated woman is one who refuses to give up.

Look past its futurist textures and careful obfuscations, and there’s something deeply human about FKA twigs’ 21st-century R&B. On her second full-length, the 31-year-old British singer-songwriter connects our current climate to that of Mary Magdalene, a healer whose close personal relationship with Christ brought her scorn from those who would ultimately write her story: men. “I\'m of a generation that was brought up without options in love,” she tells Apple Music. “I was told that as a woman, I should be looked after. It\'s not whether I choose somebody, but whether somebody chooses me.” Written and produced by twigs, with major contributions from Nicolas Jaar, *MAGDALENE* is a feminist meditation on the ways in which we relate to one another and ourselves—emotionally, sexually, universally—set to sounds that are at once modern and ancient. “Now it’s like, ‘Can you stand up in my holy terrain?’” she says, referencing the titular lyric from her mid-album collaboration with Future. “‘How are we going to be equals in this? Spiritually, am I growing? Do you make me want to be a better person?’ I’m definitely still figuring it out.” Here, she walks us through the album track by track. **thousand eyes** “All the songs I write are autobiographical. Anyone that\'s been in a relationship for a long time, you\'re meshed together. But unmeshing is painful, because you have the same friends or your families know each other. No matter who you are, the idea of leaving is not only a heart trauma, but it\'s also a social trauma, because all of a sudden, you don\'t all go to that pub that you went to together. The line \[\'If I walk out the door/A thousand eyes\'\] is a reference to that. At the time, I was listening to a lot of Gregorian music. I’d started really getting into medieval chords before that, and I\'d found some musicians that play medieval music and done a couple sessions with them. Even on \[2014\'s\] *LP1*, I had ‘Closer,’ which is essentially a hymn. I spent a lot of time in choir as a child and I went to Sunday school, so it’s part of who I am at this stage.” **home with you** “I find things like that interesting in the studio, just to play around and bring together two completely different genres—like Elton John chords and a hip-hop riff. That’s what ‘home with you’ was for me: It’s a ballad and it\'s sad, but then it\'s a bop as well, even though it doesn\'t quite ever give you what you need. It’s about feeling pulled in all directions: as a daughter, or as a friend, or as a girlfriend, or as a lover. Everyone wanting a piece of you, but not expressing it properly, so you feel like you\'re not meeting the mark.” **sad day** “It’s like, ‘Will you take another chance with me? Can we escape the mundane? Can we escape the cyclical motion of life and be in love together and try something that\'s dangerous and exhilarating? Yeah, I know I’ve made you sad before, but will you give me another chance?\' I wrote this song with benny blanco and Koreless. I love to set myself challenges, and it was really exciting to me, the challenge of retaining my sound while working with a really broad group of people. I was lucky working with Benny, in the fact that he creates an environment where, as an artist, you feel really comfortable to be yourself. To me, that\'s almost the old-school definition of a producer: They don\'t have to be all up in your grill, telling you what to do. They just need to lay a really beautiful, fertile soil, so that you can grow to be the best you in the moment.” **holy terrain** “I’m saying that I want to find a man that can stand up next to me, in all of my brilliance, and not feel intimidated. To me, Future’s saying, ‘Hey, I fucked up. I filled you with poison. I’ve done things to make you jealous. Can you heal me? Can you tell me how to be a better man? I need the guidance, of a woman, to show me how to do that.’ I don\'t think that there are many rappers that can go there, and just put their cards on the table like that. I didn\'t know 100%, once I met Future, that it would be right. But we spoke on the phone and I played him the album and I told him what it was about: ‘It’s a very female-positive, femme-positive record.’ And he was just like, ‘Yeah. Say no more. I\'ve got this.’ And he did. He crushed it. To have somebody who\'s got patriarchal energy come through and say that, wanting to stand up and be there for a woman, wanting to have a woman that\'s an equal—that\'s real.” **mary magdalene** “Let’s just imagine for one second: Say Jesus and Mary Magdalene are really close, they\'re together all the time. She\'s his right-hand woman, she’s his confidante, she\'s healing people with him and a mystic in her own right. So, at that point, any man and woman that are spending that much time together, they\'re likely to be what? Lovers. Okay, cool. So, if Mary had Jesus\' children, that basically debunks the whole of history. Now, I\'m not saying that happened. What I\'m saying is that the idea of people thinking that might happen is potentially really dangerous. It’s easier to call her a whore, because as soon as you call a woman a whore, it devalues her. I see her as Jesus Christ\'s equal. She’s a male projection and, I think, the beginning of the patriarchy taking control of the narrative of women. Any woman that\'s done anything can be subject to that; I’ve been subject to that. It felt like an apt time to be talking about it.” **fallen alien** “When you\'re with someone, and they\'re sleeping, and you look at them, and you just think, \'No.\' For me, it’s that line, \[\'When the lights are on, I know you/When you fall asleep, I’ll kick you down/By the way you fell, I know you/Now you’re on your knees\'\]. You\'re just so sick of somebody\'s bullshit, you\'re just taking it all day, and then you\'re in bed next to them, and you\'re just like, ‘I can\'t take this anymore.’” **mirrored heart** “People always say, ‘Whoever you\'re with, they should be a reflection of yourself.’ So, if you\'re looking at someone and you think, ‘You\'re a shitbag,’ then you have to think about why it was that person, at that time, and what\'s connecting you both. What is the reflection? For others that have found a love that is a true reflection of themselves, they just remind me that I don\'t have that, a mirrored heart.” **daybed** “Have you ever forgotten how to spell a really simple word? To me, depression\'s a bit like that: Everything\'s quite abstract, and even slightly dizzy, but not in a happy way. It\'s like a very slow circus. Suddenly the fruit flies seem friendly, everything in the room just starts having a different meaning and you even have a different relationship with the way the sofa cushions smell. \[Masturbation\] is something to raise your endorphins, isn\'t it? It’s either that or try and go to the gym, or try and eat something good. You almost can\'t put it into words, but we\'ve all been there. I sing, \'Active are my fingers/Faux, my cunnilingus\': You\'re imagining someone going down on you, but they\'re actually not. You open your eyes, and you\'re just there, still on your sofa, still watching daytime TV.” **cellophane** “It\'s just raw, isn\'t it? It didn\'t need a thing. The vocal take that\'s on the record is the demo take. I had a Lyft arrive outside the studio and I’d just started playing the piano chords. I was like, ‘Hey, can you just give me like 20, 25 minutes?’ And I recorded it as is. I remember feeling like I wanted to cry, but I just didn\'t feel like it was that suitable to cry at a studio session. I often want everything to be really intricate and gilded, and I want to chip away at everything, and sculpt it, and mold it, and add layers. The thing I\'ve learned on *MAGDALENE* is that you don\'t need to do that all the time, and just because you can do something, it doesn\'t mean you should. That\'s been a real growing experience for me—as a musician, as a producer, as a singer, even as a dancer. Something in its most simple form is beautiful.”

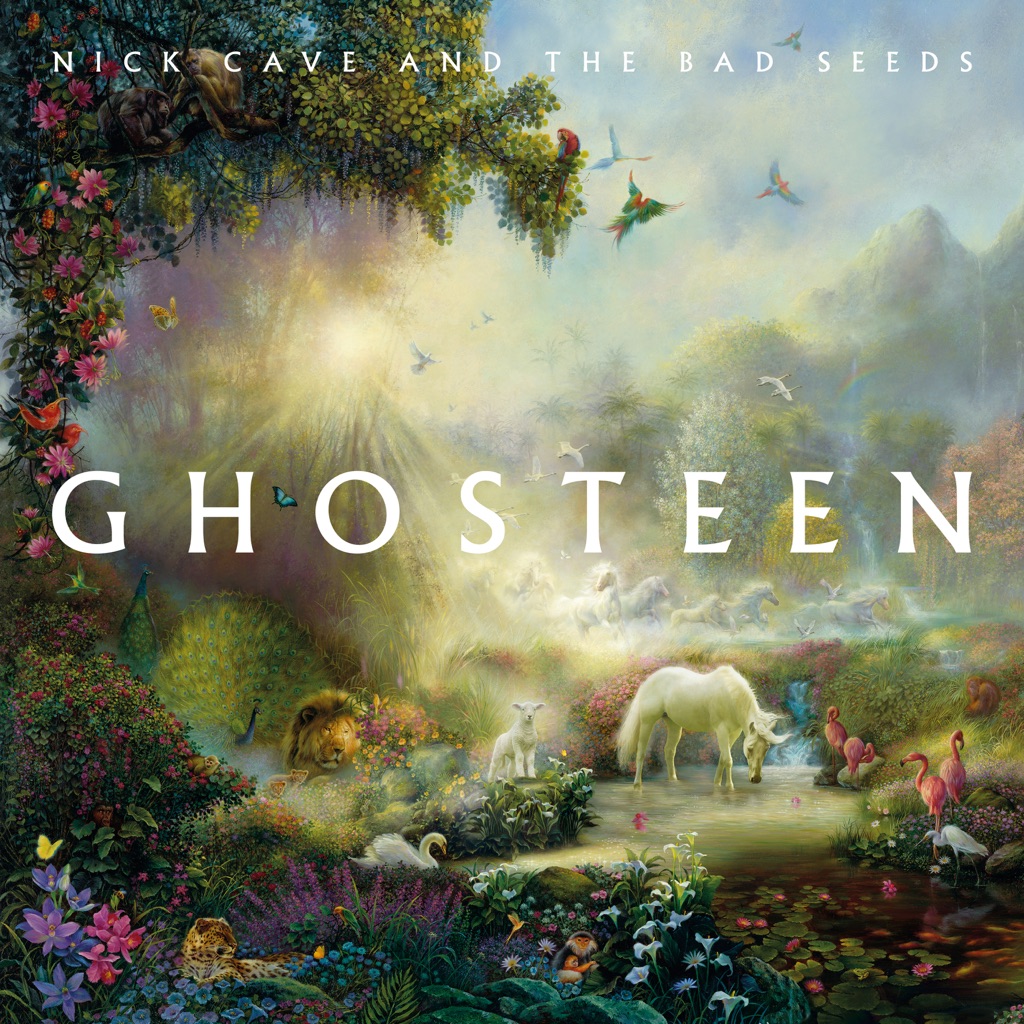

The cover art for Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ 17th album couldn’t feel more removed from the man once known as a snarling, terrifying prince of poetic darkness. This heavenly forest with its vibrant flowers, rays of sun, and woodland creatures feels comically opposed to anything Cave has ever represented—but perhaps that’s the point. This pastel fairy tale sets the scene for *Ghosteen*, his most minimalist, supernatural work to date, in which he slips between realms of fantasy and reality as a means to accept life and death, his past and future. In his very first post on The Red Hand Files—the website Cave uses to receive and respond to fan letters—he spoke of rebuilding his relationship with songwriting, which had been damaged while enduring the grief that followed his son Arthur’s death in 2015. He wrote, “I found with some practise the imagination could propel itself beyond the personal into a state of wonder. In doing so the colour came back to things with a renewed intensity and the world seemed clear and bright and new.” It is within that state of wonder that *Ghosteen* exists. “The songs on the first album are the children. The songs on the second album are their parents,” Cave has explained. Those eight “children” are misty, ambient stories of flaming mares, enchanted forests, flying ships, and the eponymous, beloved Ghosteen, described as a “migrating spirit.” The second album features two longer pieces, connected by the spoken-word “Fireflies.” He tells fantasy stories that allude to love and loss and letting go, and occasionally brings us back to reality with detailed memories of car rides to the beach and hotel rooms on rainy days. These themes aren’t especially new, but the feeling of this album is. There are no wild murder ballads or raucous, bluesy love songs. Though often melancholy, it doesn’t possess the absolute devastation and loneliness of 2016’s *Skeleton Tree*. Rather, these vignettes and symbolic myths are tranquil and gentle, much like the instrumentation behind them. With little more than synths and piano behind Cave’s vocals, *Ghosteen* might feel uneventful at times, but the calmness seems to help his imagination run free. On “Bright Horses,” he sings of “Horses broken free from the fields/They are horses of love, their manes full of fire.” But then he pulls back the curtain and admits, “We’re all so sick and tired of seeing things as they are/Horses are just horses and their manes aren’t full of fire/The fields are just fields, and there ain’t no lord… This world is plain to see, it don’t mean we can’t believe in something.” Through these dreamlike, surreal stories, Cave is finding his path to peace. And he’s learned that he isn’t alone on his journey. On “Galleon Ship,” he begins, “If I could sail a galleon ship, a long, lonely ride across the sky,” before realizing: “We are not alone, it seems, so many riders in the sky/The winds of longing in their sails, searching for the other side.”

“How people may emotionally connect with music I’ve been involved in is something that part of me is completely mystified by,” Thom Yorke tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “Human beings are really different, so why would it be that what I do connects in that way? I discovered maybe around \[Radiohead\'s album\] *The Bends* that the bit I didn’t want to show, the vulnerable bit… that bit was the bit that mattered.” *ANIMA*, Yorke’s third solo album, further weaponizes that discovery. Obsessed by anxiety and dystopia, it might be the most disarmingly personal music of a career not short of anxiety and dystopia. “Dawn Chorus” feels like the centerpiece: It\'s stop-you-in-your-tracks beautiful with a claustrophobic “stream of consciousness” lyric that feels something like a slowly descending panic attack. And, as Yorke describes, it was the record\'s biggest challenge. “There’s a hit I have to get out of it,” he says. “I was trying to develop how ‘Dawn Chorus’ was going to work, and find the right combinations on the synthesizers I was using. Couldn’t find it, tried it again and again and again. But I knew when I found it I would have my way into the song. Things like that matter to me—they are sort of obsessive, but there is an emotional connection. I was deliberately trying to find something as cold as possible to go with it, like I sing essentially one note all the way through.” Yorke and longtime collaborator Nigel Godrich (“I think most artists, if they\'re honest, are never solo artists,” Yorke says) continue to transfuse raw feeling into the album’s chilling electronica. “Traffic,” with its jagged beats and “I can’t breathe” refrain, feels like a partner track to another memorable Yorke album opener, “Everything in Its Right Place.” The extraordinary “Not the News,” meanwhile, slaloms through bleeps and baleful strings to reach a thunderous final destination. It’s the work of a modern icon still engaged with his unique gift. “My cliché thing I always say is, \'You know you\'re in trouble when people stop listening to sad music,\'” Yorke says. “Because the moment people stop listening to sad music, they don\'t want to know anymore. They\'re turning themselves off.”

What happens when the reigning queen of bubblegum pop goes through a breakup? Exactly what you’d think: She turns around and creates her most romantic, wholehearted, blissed-out work yet. Written with various pop producers in LA (Captain Cuts), New York (Jack Antonoff), and Sweden, as well as on a particularly formative soul-searching trip to the Italian coast, Jepsen’s fourth album *Dedicated* is poptimism at its finest: joyous and glitzy, rhythmic and euphoric, with an extra layer of kitsch. It’s never sad—that just isn’t Jepsen—but the “Call Me Maybe” star *does* get more in her feelings; songs like “No Drug Like Me” and “Right Words Wrong Time” aren\'t about fleeing pain so much as running to it. As Jepsen puts it on the synth ballad “Too Much,” she’d do anything to get the rush of being in love, even if it means risking heartache again and again. “Party for One,” the album’s standout single, is an infectious, shriek-worthy celebration of being alone that also acknowledges just how difficult that can be: “Tried to let it go and say I’m over you/I’m not over you/But I’m trying.”

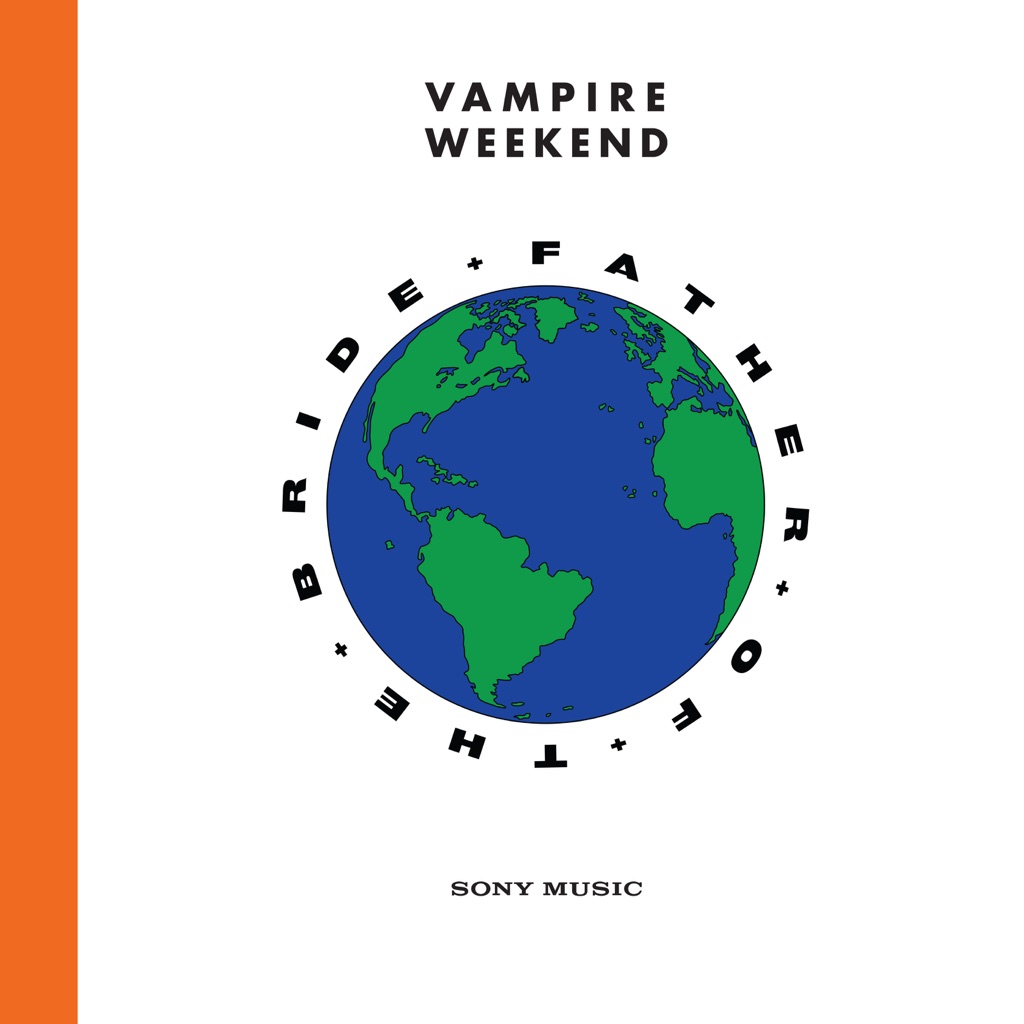

“It feels right that our fourth album is not 10, 11 songs,” Vampire Weekend frontman Ezra Koenig explains on his Beats 1 show *Time Crisis*, laying out the reasoning behind the 18-track breadth of his band\'s first album in six years. “It felt like it needed more room.” The double album—which Koenig considers less akin to the stylistic variety of The Beatles\' White Album and closer to the narrative and thematic cohesion of Bruce Springsteen\'s *The River*—also introduces some personnel changes. Founding member Rostam Batmanglij contributes to a couple of tracks but is no longer in the band, while Haim\'s Danielle Haim and The Internet\'s Steve Lacy are among the guests who play on multiple songs here. The result is decidedly looser and more sprawling than previous Vampire Weekend records, which Koenig feels is an apt way to return after a long hiatus. “After six years gone, it\'s a bigger statement.” Here Koenig unpacks some of *Father of the Bride*\'s key tracks. **\"Hold You Now\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “From pretty early on, I had a feeling that\'d be a good track one. I like that it opens with just acoustic guitar and vocals, which I thought is such a weird way to open a Vampire Weekend record. I always knew that there should be three duets spread out around the album, and I always knew I wanted them to be with the same person. Thank God it ended up being with Danielle. I wouldn\'t really call them country, but clearly they\'re indebted to classic country-duet songwriting.” **\"Rich Man\"** “I actually remember when I first started writing that; it was when we were at the Grammys for \[2013\'s\] *Modern Vampires of the City*. Sometimes you work so hard to come up with ideas, and you\'re down in the mines just trying to come up with stuff. Then other times you\'re just about to leave, you listen to something, you come up with a little idea. On this long album, with songs like this and \'Big Blue,\' they\'re like these short-story songs—they\'re moments. I just thought there\'s something funny about the narrator of the song being like, \'It\'s so hard to find one rich man in town with a satisfied mind. But I am the one.\' It\'s the trippiest song on the album.” **\"Married in a Gold Rush\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “I played this song for a couple of people, and some were like, \'Oh, that\'s your country song?\' And I swear, we pulled our hair out trying to make sure the song didn\'t sound too country. Once you get past some of the imagery—midnight train, whatever—that\'s not really what it\'s about. The story is underneath it.” **\"Sympathy”** “That\'s the most metal Vampire Weekend\'s ever gotten with the double bass drum pedal.” **\"Sunflower\" (feat. Steve Lacy)** “I\'ve been critical of certain references people throw at this record. But if people want to say this sounds a little like Phish, I\'m with that.” **\"We Belong Together\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “That\'s kind of two different songs that came together, as is often the case of Vampire Weekend. We had this old demo that started with programmed drums and Rostam having that 12-string. I always wanted to do a song that was insanely simple, that was just listing things that go together. So I\'d sit at the piano and go, \'We go together like pots and pans, surf and sand, bottles and cans.\' Then we mashed them up. It\'s probably the most wholesome Vampire Weekend song.”

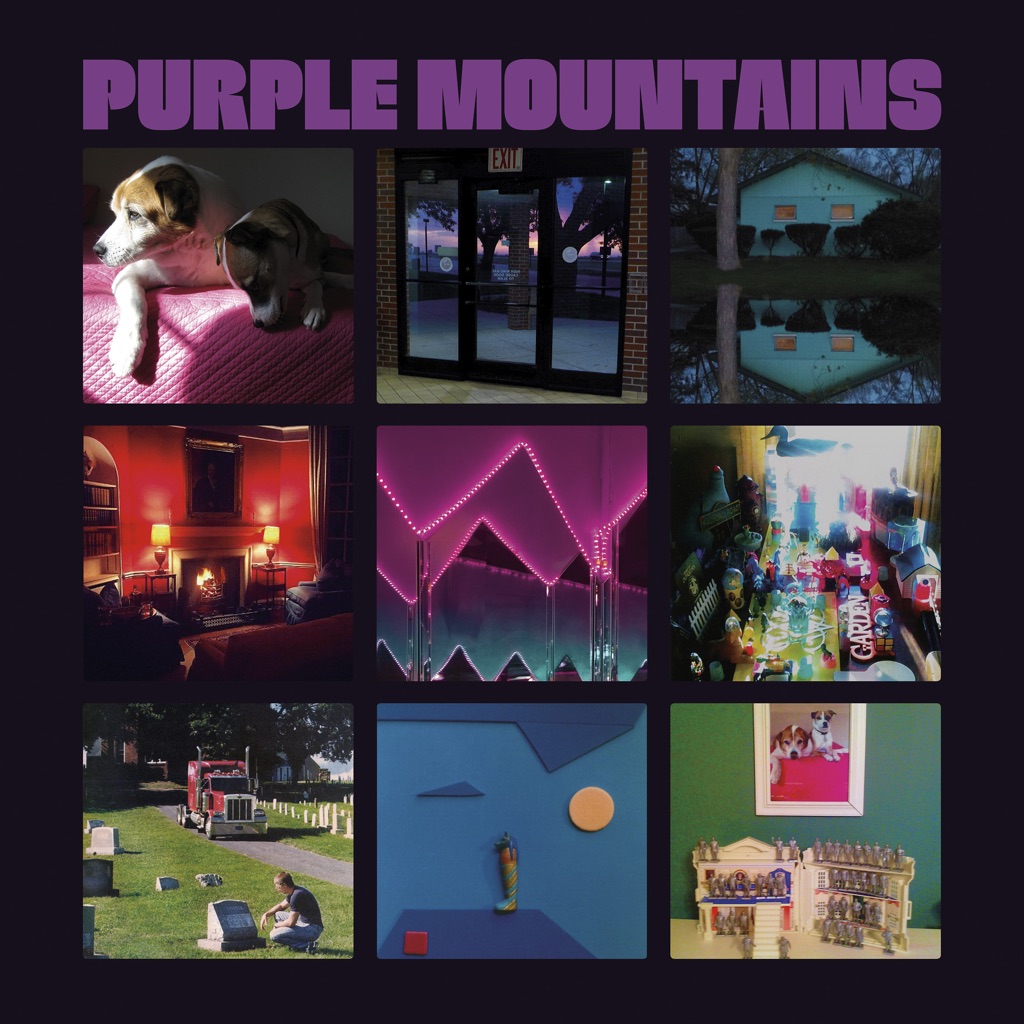

When David Berman disbanded Silver Jews in 2009, the world stood to lose one of the best writers in indie rock, a guy who catalogued the magic and misery of everyday life with wit, heart, and the ragged glory of the occupationally down-and-out. After a 10-year break professedly spent reading books and arguing with people on Reddit, Berman enlisted members of the Brooklyn band Woods to back him on *Purple Mountains*. Berman’s pain had never been laid quite so bare, nor had it ever sounded quite so urgent. “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion,” he sings on the swaggering “That’s Just the Way I Feel.” “Day to day, I’m neck and neck with giving in.” And “Margaritas at the Mall” turns an ordinary happy hour into a jeremiad about the cold comforts of capitalism in a godless world. That the music—country-tinged indie rock—was as polished and competent as it was only highlighted Berman’s intensity: less a rock singer than a street preacher, someone who needed to avail himself of his visions stat. But even at his most desperate, he remained achingly funny, turning statements of existential loneliness into the kind of bumper sticker Zen that made him seem like an ordinary guy no matter how highfalutin he could get. “Well, if no one’s fond of fuckin’ me, maybe no one’s fuckin’ fond of me,” he sings on the album-closing “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” sounding not all that far off from the George Strait one-twos he reportedly loved. Above all, though, his writing is beautiful, attuned to detail in ways that make ordinary scenarios shimmer with quiet magic. Just listen to “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan,” which turns a quiet night in a big city into an allegory of finding solace in the weather of what comes to us. Shortly after the release of *Purple Mountains*, Berman died, at the age of 52, a tragic end to what felt like a triumphant return. “The dead know what they\'re doing when they leave this world behind,” he sings on “Nights That Won’t Happen.” “When the here and the hereafter momentarily align.”

David Berman comes in from the cold after ten long years. His new musical expression is a meltdown unparalleled in modern memory. He warns us that his findings might be candid, but as long as his punishment comes in such bite-sized delights of all-American jukebox fare, we'll hike the Purple Mountains with pleasure forever.

After the billowing, nearly gothic pop of 2016’s *Blood Bitch*—which included a song constructed entirely from feral panting—Norwegian singer-songwriter Jenny Hval makes the unlikely pivot into brightly colored synth-pop on *The Practice of Love*. Rarely has music so experimental been quite this graceful, so deeply invested in the kinds of immediate pleasure at which pop music excels. Conceptually and sometimes formally, the album can be as challenging as Hval’s thorniest work. The title track layers together a spoken-word soliloquy by Vivian Wang, the album’s chief vocalist, with an unrelated conversation between Hval and the Australian musician Laura Jean, so that resonant details—about hatred of love, the fragility of the ego, the decision not to have children—drift free of their original contexts and intertwine over a bed of ambient synths. But the bulk of the record is built atop a shimmering foundation of buoyant synths and sleek dance beats, with memories of ’90s trance and dream pop seeping into cryptic lyrics about vampires, thumbsuckers, and nuclear families. In “Six Red Cannas,” Hval makes a pilgrimage to Georgia O’Keeffe’s ranch in New Mexico, citing Joni Mitchell and Amelia Earhart as she meditates on the endless skies above. Her invocation of such feminist pioneers is fitting. Refusing to take even the most well-worn categories as a given, Hval reinvents the very nature of pop music.

At first listen, The Practice of Love, Jenny Hval’s seventh full-length album, unspools with an almost deceptive ease. Across eight tracks, filled with arpeggiated synth washes and the kind of lilting beats that might have drifted, loose and unmoored, from some forgotten mid-’90s trance single, The Practice of Love feels, first and foremost, compellingly humane. Given the horror and viscera of her previous album, 2016’s Blood Bitch, The Practice of Love is almost subversive in its gentleness—a deep dive into what it means to grow older, to question one’s relationship to the earth and one’s self, and to hold a magnifying glass over the notion of what intimacy can mean. As Hval describes it, the album charts its own particular geography, a landscape in which multiple voices engage and disperse, and the question of connectedness—or lack thereof—hangs suspended in the architecture of every song. It is an album about “seeing things from above—almost like looking straight down into the ground, all of these vibrant forest landscapes, the type of nature where you might find a porn magazine at a certain place in the woods and everyone would know where it was, but even that would just become rotting paper, eventually melting into the ground.” Prompted by an urge to find a different kind of language to express what she was feeling, the songs on Love unfurl like an interior dialogue involving several voices. Friends and collaborators Vivian Wang, Laura Jean Englert, and Felicia Atkinson surface on various tracks, via contributed vocals or through bits of recorded conversation, which further posits the record itself as a kind of ongoing discourse. “The last thing I wrote, which was my new book (forthcoming), had quite an angry voice,” says Hval, “The voice of an angry teenager, furious at the hierarchies. Perhaps this album rediscovers that same voice 20 years later. Not so angry anymore, but still feeling apart from the mainstream, trying to find their place and their community. With that voice, I wanted to push my writing practice further, writing something that was multilayered, a community of voices, stories about both myself and others simultaneously, or about someone’s place in the world and within art history at the same time. I wanted to develop this new multi-tracked writing voice and take it to a positive, beautiful pop song place... A place which also sounds like a huge pile of earth that I’m about to bury my coffin in.” Opening track “Lions” sets the tone for the record, both thematically and aesthetically, offering both a directive and a question: “Look at these trees / Look at this grass / Look at those clouds / Look at them now / Study this and ask yourself: Where is God?” The idea of placing ourselves in context to the earth and to others bubbles up throughout the record. On “Accident” two friends video chat on the topic of childlessness, considering their own ambivalence about motherhood and the curiosity of having been born at all. “She is an accident,” Hval sings, “She is made for other things / Born for cubist yearnings / Born to Write. Born to Burn / She is an accident / Flesh in dissent.” What does it mean to be in the world? What does it mean to participate in the culture of what it means to be human? To parent (or not)? To live and die? To practice love and care? What must we do to feel validated as living beings? Such questions are baked into the DNA of Love, wrapped up in layers of gauzy synthesizers and syncopated beats. Even when circling issues of mortality, there is a kind of humane delight at play. “Put two fingers in the earth,” Hval intones on “Ashes to Ashes”— “I am digging my own grave / in the honeypot / ashes to ashes / dust to dust.” Balanced against these ruminations on love, care and being, Hval employs sounds that are both sentimental and more than a little nostalgic. “I kept coming back to trashy, mainstream trance music from the ’90s,” she says, “It’s a sound that was kind of hiding in the back of my mind for a long time. I don’t mean trashy in a bad sense, but in a beautiful one. The synth sounds are the things I imagined being played at the raves I was too young and too scared to attend, they were the sounds I associated with the people who were always driving around the two streets in the town where I grew up, the guys with the big stereo in the car that was always just pumping away. I liked the idea of playing with trance music in the true transcendental sense, those washy synths have lightness and clarity to them. I think I’m always looking for what sounds can bring me to write, and these synths made me write very open, honest lyrics.” Though The Practice of Love was, in some sense, inspired by Valie Export’s 1985 film of the same name, for Hval the concept of love as a practice—as an ongoing, sustained, multivalent activity—provided a way to broaden and expand her own writing practice. Lyrically, the 8 tracks present here, particularly the title track, hew more closely to poetic forms than anything Hval has made before. (As evidenced by the record’s liner notes, which assume the form of a poetry chapbook.) Rather than shrink from the subject or try to overly obfuscate in some way, Love considers the notion of intimacy from all sides, whether it be positing the notion of art in conversation with other artists (“Six Red Cannas”) or playing with clichés around what it means to be a woman who makes art (“High Alice”), Hval’s songs attempt to make sense of what love and care actually mean—love as a practice, a vocation that one must continually work at. “This sounds like something that should be stitched on a pillow, but intimacy really is a lifelong journey,” she explains, “And I am someone who is interested in what ideas or practices of love and intimacy can be. These practices have for me been deeply tied to the practice of otherness, of expressing myself differently from what I’ve seen as the norm. Maybe that's why I've mostly avoided love as a topic of my work. The theme of love in art has been the domain of the mainstream for me. Love is one of those major subjects, like death and the ocean, and I’m a minor character. But in the last few years I have wanted to take a closer look at otherness, this fragile performance, to explore how it expresses love, intimacy, and kindness. I've wanted to explore how otherness deals with the big, broad themes. I've wanted to ask big questions, like: What is our job as a member of the human race? Do we have to accept this job, and if we don’t, does the pressure to be normal ever stop?” It’s a crazy ambition, perhaps, to think that something as simple as a pop song can manage, over the course of two or three minutes, to chisel away at some extant human truth. Still, it’s hard to listen to the songs on The Practice of Love and not feel as if you are listening in on a private conversation, an examination that is, for lack of a better word, truly intimate. Tucked between the beats and washy synths, the record spills over with slippery truths about what it is to be a human being trying to move through the world and the ways—both expected and unexpected—we relate to each other. “Outside again, the chaos / and I wonder what is lost,” Hval sings on “Ordinary,” the album’s closing track, “We don’t always get to choose / when we are close / and when we are not.”

“We’ve never really had anyone say to us, ‘All right, this song is good but we should try to push it to another level,’” Hot Chip’s Joe Goddard tells Apple Music. Seven albums deep, the band—Goddard, Alexis Taylor, Al Doyle, Owen Clarke, and Felix Martin—decided to reach new levels by working with producers for the first time, drafting in Rodaidh McDonald (The xx, Sampha) and the late French touch prime mover Philippe Zdar. “They didn\'t really ask us to do anything mega crazy, but there were moments when they challenged us and pushed us out of our comfort zone, which was really healthy and good,” says Goddard. *A Bath Full of Ecstasy* handsomely vindicates the decision to solicit external opinion. Rather than abandon their winning synthesis of pop melodies, melancholy, and the sparkle of club music, the band has finessed it into their brightest, sharpest album yet. And they got there with the help of Katy Perry, hot sauce, and Taylor’s mother-in-law—discover how with their track-by-track guide. **“Melody of Love”** Alexis Taylor: “It’s about submitting to sound, and finding optimism within its abstract beauty. It’s about the personal as well as the more universal problems being faced by individuals, and overcoming those; it’s about connecting to something that resonates with you.” Joe Goddard: “I was initially imagining I would put it out without vocals on, without there really being a song. But I found this sample from a gospel track by The Mighty Clouds of Joy, and Alexis responded to the music very quickly and wrote these great words. Rodaidh is a very focused person, a bit like the T-1000, and was like, ‘OK, guys, we’re going to do this, this, this, this, this.’ And he cut it right down, which was a really good suggestion.” **“Spell”** AT: “This is a seduction song, but it’s not entirely clear who is in the driving seat, who has the upper hand, who holds the whip…” JG: “Alexis’ songwriting and lyrics are fantastic, but he is such an enormous lover of Prince, I felt like there would be places that he could go that would be slightly more sensual, sexual. And that he would really excel at it. But I don’t think it comes naturally to him. Then we were asked to do a few days in the studio with Katy Perry. We wrote a bunch of short demo ideas to play to her, and the beginning of ‘Spell’ was one of those. I think for Alexis, imagining writing something for her was quite freeing.” **“Bath Full of Ecstasy”** AT: “‘Bath Full of Ecstasy’ is a side-scrolling platform game in which the player takes control of one of the five band members on a quest to save the kingdom. A curse has ravaged the kingdom and eradicated all joy from the land, and the townsfolk and villagers can no longer see colors or hear music. With the help of the Bubble Bath Fairy, a magical microphone, and some friendly strangers along the way, the band must embark on a quest through five exciting worlds on a mission to find the secret source that will break the curse.” **“Echo”** JG: “The demo was another one that we wrote for the Katy Perry sessions. We were trying to do something a bit Neptunes-y, a bit Pharrell—quite simple hip-hop-y bassline and drums. Lyrically it deals with letting go of your past.” AT: “It was originally called ‘Hot Sauce’ and was written about my favorite hot sauce, made by my friend, the steel-pan legend Fimber Bravo.” Al Doyle: “This was Philippe bringing to the pool his concept of ‘air,’ putting in huge gaps and spaces and really reducing the sonic palette of the song—to the point where you’re almost like, ‘Oh wow, this is actually almost too sparse.’ But what is there is extremely powerful and crafted and razor-sharp.” **“Hungry Child”** JG: “It’s all about this real longing, obsessional kind of love—unrequited. Obviously, a classic subject for soul and disco music, and I was really channeling that. I love disco records that do that; I think there’s a real special power to them. And in Jamie Principle, Frankie Knuckles, that brilliant deep house classic Round Two, ‘New Day,’ you get this obsessional, dark love stuff as well.” AT: “I mainly played Mellotron and wrote the chorus—about things which are momentary but somehow affect you forever.” **“Positive”** AT: “The song talks about perceptions of homelessness, illness, the need for community, kind gestures or lack of, information, love. It’s a heartbreak song with those subjects and a fantasy relationship at the core.” JG: “It features this Eurorack synth stuff very heavily, which is screamingly modern-sounding.” **“Why Does My Mind”** AT: “A song written on Alex Chilton’s guitar, lent to me by Jason McPhail \[of Glasgow band V-Twin\], about the perplexing way in which my mind works.” **“Clear Blue Skies”** JG: “Once a record is 70 percent done, you’re thinking about how to complement the music that you already have. So we wanted to have a more gentle, drum-machine-led thing. I was really also inspired by ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ by Brian Eno, which has that feel. I find it really difficult, with the size of the universe, trying to find that meaning in small things. I find that really problematic sometimes—that’s the meaning of the song.” **“No God”** AT: “A love song, written with my mother-in-law in mind as the singer, for a TV talent show contest, but never delivered to her, and instead turned into a euphoric song about love for a person rather than God, or light.” JG: “The chorus and the verse are very, very simple pop music. It reminded us of ABBA at one point. We struggled to find a production that was interesting, that had the right balance of strangeness and poppiness. It reminds me a bit of Andrew Weatherall and Primal Scream, that kind of balearic house thing.” Owen Clarke: “It went reggae for a bit. It had a techno moment as well.”

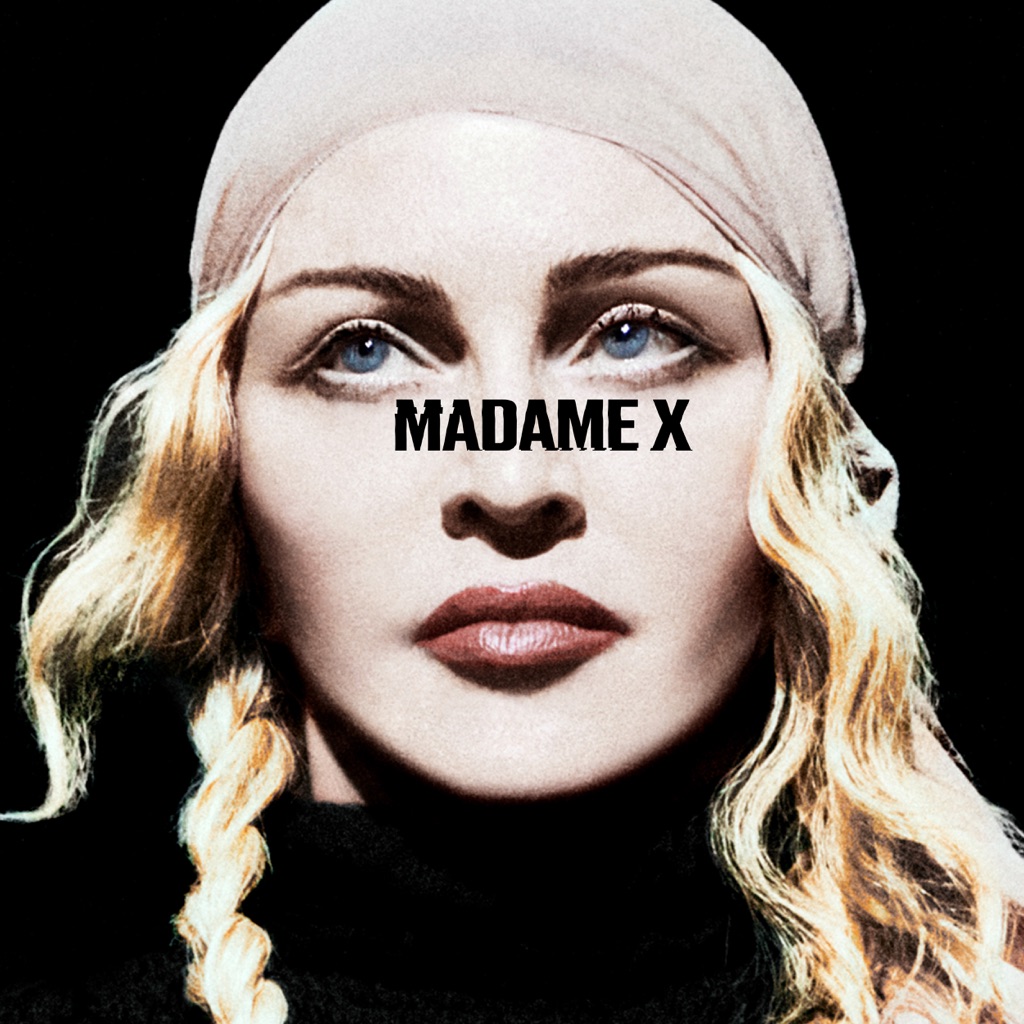

“The whole inspiration for this record was completely and utterly based on going out in Lisbon and trying to make friends,” Madonna tells Apple Music\'s Julie Adenuga. “Portugal is such a melting pot for so many different cultures—there\'s a lot of people from Brazil, Angola, Spain. You can stand out on a balcony and hear some incredible voice carrying through the starlit sky, and it\'s just so magical you can\'t help but be inspired by it.” Fourteen albums in, it may be standard practice for Madonna to immerse herself in new cultures as a way of sparking artistic ideas, but her recent move to Lisbon opened her to incorporating not just different sounds but different languages. As evidence, look no further than “Medellin,” one of two collaborations on the album with Colombian pop star Maluma. “I heard from his manager that he wanted to collaborate with me,” she said. “\[My producer and I\] started listening to his music more closely, thinking, \'Okay, how can we do something slightly different but that still has a connection to the music that he makes?’” This adventurous strategy—as much a cultural bridge as a musical technique—is what makes the sprawling *Madame X* so bold and timely. By fusing some of pop’s trendiest sounds (deep house, disco, and dancehall are a few) with characteristically eccentric imagery and serious subject matter (gun control, narcissism, ageism, and political noise), she doesn’t just acknowledge the current moment, she confronts it. “This is your wake-up call,” she sings on “God Control,” which morphs from spiritual hymn into ironic disco-funk at the sound of disquieting gunshots. “We don’t have to fall/A new democracy.” She seems to find hope in her own perseverance: “Died a thousand times/Managed to survive,” she sings on “I Rise.” “I rise up above it all.”

It\'s hard to imagine Bruce Springsteen describing a project of his as a concept album—too much prog baggage, too much expectation of some big, grand, overarching *story*. But nothing he\'s done across five decades as one of rock\'s most accomplished storytellers has had the singular, specific focus and locus, lyrically and musically, as this long-gestating solo effort—a lush meditation on the landscape of the western United States and the people who are drawn there, or got stuck there. Neither a bare-bones acoustic effort like *Nebraska* nor a fully tricked-out E Street Band affair, this set of 13 largely subdued character-driven songs (his first new ones since 2014\'s *High Hopes*, following five years immersed in memoir) is ornamented with strings and horns and slide guitar and banjo that sound both dusty and Dusty. They trade in the most familiar of American iconography—trains, hitchhikers, motels, sunsets, diners, Hollywood, and, of course, wild horses—but aren\'t necessarily antiquated; the clichés are jumping-off points, aiming for timelessness as much as nostalgia. The battered stuntman of “Drive Fast” could be licking, and cataloging, his wounds in 1959 or 2019. As convulsive and pivotal as the current moment may feel, restlessness and aimlessness and disenfranchisement are evergreen, and the songs are built to feel that way. In true Springsteen fashion, the personal is elevated to the mythical.

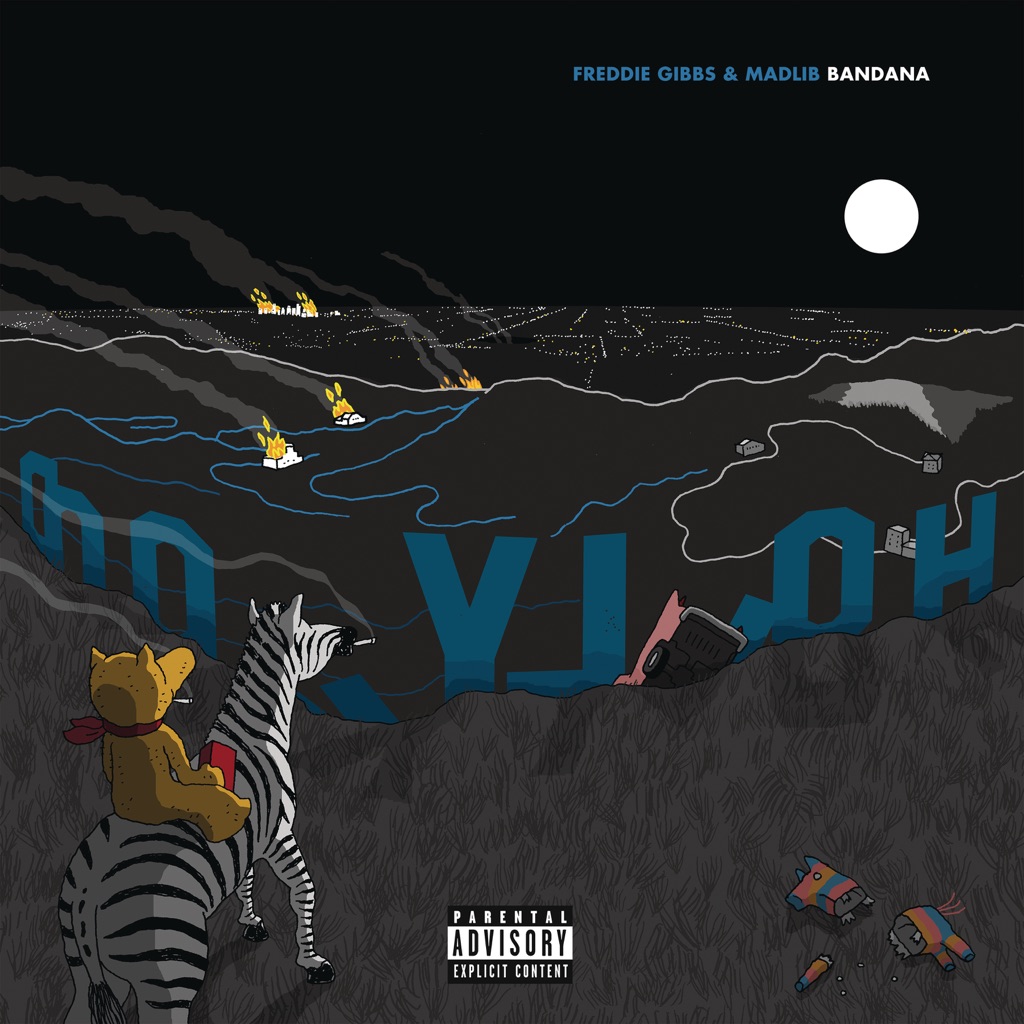

An eccentric like Madlib and a straightforward guy like Freddie Gibbs—how could it possibly work? If 2014’s *Piñata* proved that the pairing—offbeat producer, no-frills street rapper—sounded better and more natural than it looked on paper, *Bandana* proves *Piñata* wasn’t a fluke. The common ground is approachability: Even at their most cinematic (the noisy soul of “Flat Tummy Tea,” the horror-movie trap of “Half Manne Half Cocaine”), Madlib’s beats remain funny, strange, decidedly at human scale, while Gibbs prefers to keep things so real he barely uses metaphor. In other words, it’s remarkable music made by artists who never pretend to be anything other than ordinary. And even when the guest spots are good (Yasiin Bey and Black Thought on “Education” especially), the core of the album is the chemistry between Gibbs and Madlib: vivid, dreamy, serious, and just a little supernatural.

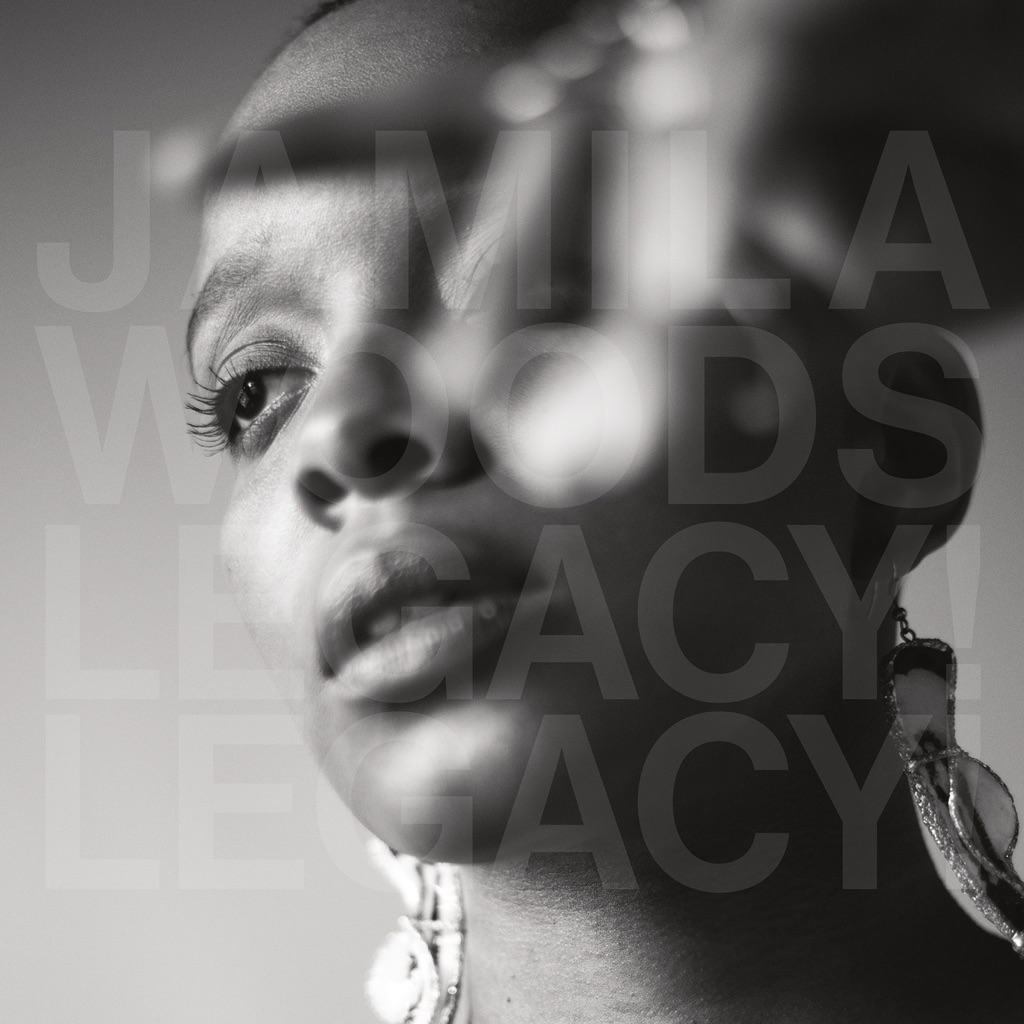

There’s nothing all that subtle about Jamila Woods naming each of these all-caps tracks after a notable person of color. Still, that’s the point with *LEGACY! LEGACY!*—homage as overt as it is original. True to her own revolutionary spirit, the Chicago native takes this influential baker’s dozen of songs and masterfully transmutes their power for her purposes, delivering an engrossingly personal and deftly poetic follow-up to her formidable 2016 breakthrough *HEAVN*. She draws on African American icons like Miles Davis and Eartha Kitt as she coos and commands through each namesake cut, sparking flames for the bluesy rap groove of “MUDDY” and giving flowers to a legend on the electro-laced funk of “OCTAVIA.”

In the clip of an older Eartha Kitt that everyone kicks around the internet, her cheekbones are still as pronounced as many would remember them from her glory days on Broadway, and her eyes are still piercing and inviting. She sips from a metal cup. The wind blows the flowers behind her until those flowers crane their stems toward her face, and the petals tilt upward, forcing out a smile. A dog barks in the background. In the best part of the clip, Kitt throws her head back and feigns a large, sky-rattling laugh upon being asked by her interviewer whether or not she’d compromise parts of herself if a man came into her life. When the laugh dies down, Kitt insists on the same, rhetorical statement. “Compromise!?!?” she flings. “For what?” She repeats “For what?” until it grows more fierce, more unanswerable. Until it holds the very answer itself. On the hook to the song “Eartha,” Jamila Woods sings “I don’t want to compromise / can we make it through the night” and as an album, Legacy! Legacy! stakes itself on the uncompromising nature of its creator, and the histories honored within its many layers. There is a lot of talk about black people in America and lineage, and who will tell the stories of our ancestors and their ancestors and the ones before them. But there is significantly less talk about the actions taken to uphold that lineage in a country obsessed with forgetting. There are hands who built the corners of ourselves we love most, and it is good to shout something sweet at those hands from time to time. Woods, a Chicago-born poet, organizer, and consistent glory merchant, seeks to honor black people first, always. And so, Legacy! Legacy! A song for Zora! Zora, who gave so much to a culture before she died alone and longing. A song for Octavia and her huge and savage conscience! A song for Miles! One for Jean-Michel and one for my man Jimmy Baldwin! More than just giving the song titles the names of historical black and brown icons of literature, art, and music, Jamila Woods builds a sonic and lyrical monument to the various modes of how these icons tried to push beyond the margins a country had assigned to them. On “Sun Ra,” Woods sings “I just gotta get away from this earth, man / this marble was doomed from the start” and that type of dreaming and vision honors not only the legacy of Sun Ra, but the idea that there is a better future, and in it, there will still be black people. Jamila Woods has a voice and lyrical sensibility that transcends generations, and so it makes sense to have this lush and layered album that bounces seamlessly from one sonic aesthetic to another. This was the case on 2016’s HEAVN, which found Woods hopeful and exploratory, looking along the edges resilience and exhaustion for some measures of joy. Legacy! Legacy! is the logical conclusion to that looking. From the airy boom-bap of “Giovanni” to the psychedelic flourishes of “Sonia,” the instrument which ties the musical threads together is the ability of Woods to find her pockets in the waves of instrumentation, stretching syllables and vowels over the harmony of noise until each puzzle piece has a home. The whimsical and malleable nature of sonic delights also grants a path for collaborators to flourish: the sparkling flows of Nitty Scott on “Sonia” and Saba on “Basquiat,” or the bloom of Nico Segal’s horns on “Baldwin.” Soul music did not just appear in America, and soul does not just mean music. Rather, soul is what gold can be dug from the depths of ruin, and refashioned by those who have true vision. True soul lives in the pages of a worn novel that no one talks about anymore, or a painting that sits in a gallery for a while but then in an attic forever. Soul is all the things a country tries to force itself into forgetting. Soul is all of those things come back to claim what is theirs. Jamila Woods is a singular soul singer who, in voice, holds the rhetorical demand. The knowing that there is no compromise for someone with vision this endless. That the revolution must take many forms, and it sometimes starts with songs like these. Songs that feel like the sun on your face and the wind pushing flowers against your back while you kick your head to the heavens and laugh at how foolish the world seems.

“It was baby steps—we didn’t say, hey, we’re going to make an album or go on tour,” The Raconteurs co-frontman Jack White explains to Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “We just thought, let’s get together and record a couple of songs and see how that goes.” The time felt right for White and Brendan Benson to reconnect following a series of jam sessions with drummer Patrick Keeler, something they hadn’t done in over a decade due to their commitments to other projects. During that time, White pursued his solo career and formed The Dead Weather with Raconteurs bassist Jack Lawrence, all while running Third Man Records; Benson launched his own record label and released 2012’s *What Kind of World* and 2013’s *You Were Right*. Though their third album touches on the power-pop stomp of *Broken Boy Soldiers* and the country-folk of *Consolers of the Lonely*, the band now seems to have one mission in mind: Play some good ol’ fashioned classic rock that pays homage to their musical roots. White and Benson are both based in Nashville now, but their native Michigan is never far from their hearts. “Well, I’m Detroit born and raised/But these days, I’m living with another,” White and Benson harmonize on the single “Bored and Razed.” The guitars nod to pioneering Michigan bands like Grand Funk Railroad and The Amboy Dukes, while the scuzzy, frantic Stooges-like garage rock of “Don’t Bother Me” features White, unsurprisingly, imploring you to put down your damn phone. But *Help Us Stranger* is not just strut and swagger: From reflective folk rock (“Only Child”) and piano balladry (“Shine the Light on Me”) to heartbreaking blues (“Now That You’re Gone”), White and Benson keep it fresh with their engaging, mood-shifting songwriting. They sound like they’re genuinely having fun, happy that they’re still together after all these years. “We played a show in London with The Strokes, and what struck me was, \'Ah, it’s so great to see any band have the original members they started with even three years later, let alone 15, 20 years later,\'” says White. “Everyone’s for the same goal of trying to make some sort of music happen that didn’t exist before. But the proof is, those same people are in the room together.”

Singer-songwriter Natalie Mering’s fourth album as Weyes Blood conjures the feeling of a beautiful object on a shelf just out of reach: You want to touch it, but you can’t, and so you do the next best thing—you dream about it, ache for it, and then you ache some more. Grand, melodramatic, but keenly self-aware, the music here pushes Mering’s \'70s-style chamber pop to its cinematic brink, suffusing stories of everything from fumbled romance (the McCartney-esque “Everyday”) to environmental apocalypse (“Wild Time”) with a dreamy, foggy almost-thereness both gorgeous and profoundly unsettling. A self-described “nostalgic futurist,” Mering doesn’t recreate the past so much as demonstrate how the past is more or less a fiction to begin with, a story we love hearing no matter how sad its unreachability makes us. Hence the album’s centerpiece, “Movies,” which wonders—gorgeously, almost religiously—why life feels so messy by comparison. As to the thematic undercurrent of apocalypse, well, if extinction is as close as science says it is, we might as well have something pretty to play us out.

The phantom zone, the parallax, the upside down—there is a rich cultural history of exploring in-between places. Through her latest, Titanic Rising, Weyes Blood (a.k.a. Natalie Mering) has, too, designed her own universe to soulfully navigate life’s mysteries. Maneuvering through a space-time continuum, she intriguingly plays the role of melodic, sometimes melancholic, anthropologist. Tellingly, Mering classifies Titanic Rising as the Kinks meet WWII or Bob Seger meets Enya. The latter captures the album’s willful expansiveness (“You can tell there’s not a guy pulling the strings in Enya’s studio,” she notes, admiringly). The former relays her imperative to connect with listeners. “The clarity of Bob Seger is unmistakable. I’m a big fan of conversational songwriting,” she adds. “I just try to do that in a way that uses abstract imagery as well.” “An album is like a Rubik’s Cube,” she says. “Sometimes you get all the dimensions—the lyrics, the melody, the production—to line up. I try to be futuristic and ancient at once, which is a difficult alchemy. It’s taken a lot of different tries to get it right.” As concept-album as it may sound, it’s also a devoted exercise in realism, albeit occasionally magical. Here, the throwback-cinema grandeur of “A Lot’s Gonna Change” gracefully coexists with the otherworldly title track, an ominous instrumental. Titanic Rising, written and recorded during the first half of 2018, is the culmination of three albums and years of touring: stronger chops and ballsier decisions. It’s an achievement in transcendent vocals and levitating arrangements—one she could reach only by flying under the radar for so many years. “I used to want to belong,” says the L.A. based musician. “I realized I had to forge my own path. Nobody was going to do that for me. That was liberating. I became a Joan of Arc solo musician.” The Weyes Blood frontwoman grew up singing in gospel and madrigal choirs. “Classical and Renaissance music really influenced me,” says Mering, who first picked up a guitar at age 8. (Listen closely to Titanic Rising, and you’ll also hear the jazz of Hoagy Carmichael mingle with the artful mysticism of Alejandro Jodorowsky and the monomyth of scholar Joseph Campbell.) “Something to Believe,” a confessional that makes judicious use of the slide guitar, touches on that cosmological upbringing. “Belief is something all humans need. Shared myths are part of our psychology and survival,” she says. “Now we have a weird mishmash of capitalism and movies and science. There have been moments where I felt very existential and lost.” As a kid, she filled that void with Titanic. (Yes, the movie.) “It was engineered for little girls and had its own mythology,” she explains. Mering also noticed that the blockbuster romance actually offered a story about loss born of man’s hubris. “It’s so symbolic that The Titanic would crash into an iceberg, and now that iceberg is melting, sinking civilization.” Today, this hubris also extends to the relentless adoption of technology, at the expense of both happiness and attention spans. The track “Movies” marks another Titanic-related epiphany, “that movies had been brainwashing people and their ideas about romantic love.” To that end, Mering has become an expert at deconstructing intimacy. Sweeping and string-laden, “Andromeda” seems engineered to fibrillate hearts. “It’s about losing your interest in trying to be in love,” she says. “Everybody is their own galaxy, their own separate entity. There is a feeling of needing to be saved, and that’s a lot to ask of people.” Its companion track, “Everyday,” “is about the chaos of modern dating,” she says, “the idea of sailing off onto your ships to nowhere to deal with all your baggage.” But Weyes Blood isn’t one to stew. Her observations play out in an ethereal saunter: far more meditative than cynical. “I experience reality on a slower, more hypnotic level,” she says. “I’m a more contemplative kind of writer.” To Mering, listening and thinking are concurrent experiences. “There are complicated influences mixed in with more relatable nostalgic melodies,” she says. “In my mind my music feels so big, a true production. I’m not a huge, popular artist, but I feel like one when I’m in the studio. But it’s never taking away from the music. I’m just making a bigger space for myself.”

Big Thief has been known to tackle intensely personal themes: family histories, deaths, isolation, fear. Here, on their expansive third album, the New York indie rock band shifts its gaze outward and into the unknown. \"Just like a bad dream/You\'ll disappear,” frontwoman Adrianne Lenker coos on the title track. \"And I imagine you/Taking me outta here.” Through gentle strums and hushed, tumbling melodies, the band wonders: Who\'s out there? Are they as strange as we are? What’s real? The second F in the album’s title stands for “friend”—an optimistic embrace of all things unfamiliar or alien. Their songs—comforting, eerie, folksy, magnificent—do the same.

U.F.O.F., F standing for ‘Friend’, is the name of the highly anticipated third record by Big Thief, set to be released on 3rd May 2019 via 4AD. U.F.O.F. was recorded in rural western Washington at Bear Creek Studios. In a large cabin-like room, the band set up their gear to track live with engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who was also behind their previous albums. Having already lived these songs on tour, they were relaxed and ready to experiment. The raw material came quickly. Some songs were written only hours before recording and stretched out instantly, first take, vocals and all. “Making friends with the unknown… All my songs are about this,” says Lenker; “If the nature of life is change and impermanence, I’d rather be uncomfortably awake in that truth than lost in denial.”

It takes a village to raise a child; Holly Herndon’s third proper studio LP, *PROTO*, holds that the same is true for an artificial intelligence, or AI. The Berlin-based electronic musician’s 2015 album *Platform* explored the intersection of community and technological utopia, and so does its follow-up—only this time, one of her collaborators is a programmed entity, a virtual being named Spawn. Arguing that technology should be embraced, not feared, Herndon and her human collaborators, including a choral ensemble and hundreds of volunteer vocal coaches, set about “teaching” their AI via call-and-response singing sessions inspired by Herndon’s religious upbringing in East Tennessee. The results harness *Platform*’s richly synthetic palette and jagged percussive force and join them with choral music of almost overwhelming beauty. The massed voices of “Frontier” suggest a combination of Appalachian revival meetings and Bulgarian folk that’s been cut up over Hollywood-blockbuster drums; in “Godmother,” a collaboration with the experimental footwork producer Jlin, Spawn “sings” a dense, hyperkinetic fugue based on Jlin’s polyrhythmic signature. The crux of the whole album might be “Extreme Love,” in which a narrator recounts the story of a future post-human generation: “We are not a collection of individuals but a macro-organism living as an ecosystem. We are completely outside ourselves and the world is completely inside us.” A loosely synchronized choir chirps in the background as she asks, in a voice full of childlike wonder, “Is this how it feels to become the mother of the next species—to love them more than we love ourselves?” It’s a moving encapsulation of the album’s radical optimism.

Holly Herndon operates at the nexus of technological evolution and musical euphoria. Holly’s third full-length album 'PROTO' isn’t about A.I., but much of it was created in collaboration with her own A.I. ‘baby’, Spawn. For the album, she assembled a contemporary ensemble of vocalists, developers, guest contributors (Jenna Sutela, Jlin, Lily Anna Haynes, Martine Syms) and an inhuman intelligence housed in a DIY souped-up gaming PC to create a record that encompasses live vocal processing and timeless folk singing, and places an emphasis on alien song craft and new forms of communion. 'PROTO' makes reference to what Holly refers to as the protocol era, where rapidly surfacing ideological battles over the future of A.I. protocols, centralised and decentralised internet protocols, and personal and political protocols compel us to ask ourselves who are we, what are we, what do we stand for, and what are we heading towards? You can hear traces of Spawn throughout the album, developed in partnership with long time collaborator Mathew Dryhurst and ensemble developer Jules LaPlace, and even eavesdrop on the live training ceremonies conducted in Berlin, in which hundreds of people were gathered to teach Spawn how to identify and reinterpret unfamiliar sounds in group call-and-response singing sessions; a contemporary update on the religious gathering Holly was raised amongst in her upbringing in East Tennessee. “There’s a pervasive narrative of technology as dehumanizing,” says Holly. “We stand in contrast to that. It’s not like we want to run away; we’re very much running towards it, but on our terms. Choosing to work with an ensemble of humans is part of our protocol. I don’t want to live in a world in which humans are automated off stage. I want an A.I. to be raised to appreciate and interact with that beauty.” Since her arrival in 2012, Holly has successfully mined the edges of electronic and Avant Garde pop and emerged with a dynamic and disruptive canon of her own, all while studying for her soon-to-be-completed PhD at Stanford University, researching machine learning and music. Just as Holly’s previous album 'Platform' forewarned of the manipulative personal and political impacts of prying social media platforms long before popular acceptance, 'PROTO' is a euphoric and principled statement setting the shape of things to come.

You don’t come to Chromatics for the songs so much as the opportunity to linger in the world in which the songs transpire: Eerie, stylish, unsettled but seductive—a horror movie so pretty you don’t see the silver for blade or the red for blood until it’s too late. Surprise-released in late 2019 after a years-long period during which they teased an entirely different album (the hypothetical *Dear Tommy*, whose 25,000 physical copies producer/songwriter Johnny Jewel supposedly destroyed), *Closer to Grey* leans on the lighter side of the band’s sound, shifting between beatless meditations (“Wishing Well,” an unnerving take on “The Sound of Silence”) and brittle, ethereal synth-pop (“You’re No Good,” the downtempo “Light as a Feather”). As with 2012’s *Kill for Love* (and even more so 2007’s classic *Night Drive*), the tension is between the anchor of the beat and the light-headedness of Ruth Radelet’s vocals, the sense that everything is beautiful and shimmering but that the beauty and shimmer only serve to conceal a lurking threat. “Don’t you know that fear is what they offer/Love is there to catch you if you fall,” Radelet sings on the harrowing “Whispers in the Hall” just as the band splinters into noise—a reassurance framed as an inescapable curse.

From the outset of his fame—or, in his earliest years as an artist, infamy—Tyler, The Creator made no secret of his idolization of Pharrell, citing the work the singer-rapper-producer did as a member of N.E.R.D as one of his biggest musical influences. The impression Skateboard P left on Tyler was palpable from the very beginning, but nowhere is it more prevalent than on his fifth official solo album, *IGOR*. Within it, Tyler is almost completely untethered from the rabble-rousing (and preternaturally gifted) MC he broke out as, instead pushing his singing voice further than ever to sound off on love as a life-altering experience over some synth-heavy backdrops. The revelations here are mostly literal. “I think I’m falling in love/This time I think it\'s for real,” goes the chorus of the pop-funk ditty “I THINK,” while Tyler can be found trying to \"make you love me” on the R&B-tinged “RUNNING OUT OF TIME.” The sludgy “NEW MAGIC WAND” has him begging, “Please don’t leave me now,” and the album’s final song asks, “ARE WE STILL FRIENDS?” but it’s hardly a completely mopey affair. “IGOR\'S THEME,” the aforementioned “I THINK,” and “WHAT\'S GOOD” are some of Tyler’s most danceable songs to date, featuring elements of jazz, funk, and even gospel. *IGOR*\'s guests include Playboi Carti, Charlie Wilson, and Kanye West, whose voices are all distorted ever so slightly to help them fit into Tyler\'s ever-experimental, N.E.R.D-honoring vision of love.

JAIME I wrote this record as a process of healing. Every song, I confront something within me or beyond me. Things that are hard or impossible to change, words and music to describe what I’m not good at conveying to those I love, or a name that hurts to be said: Jaime. I dedicated the title of this record to my sister who passed away as a teenager. She was a musician too. I did this so her name would no longer bring me memories of sadness and as a way to thank her for passing on to me everything she loved: music, art, creativity. But, the record is not about her. It’s about me. It’s not as veiled as work I have done before. I’m pretty candid about myself and who I am and what I believe. Which, is why I needed to do it on my own. I wrote and arranged a lot of these songs on my laptop using Logic. Shawn Everett helped me make them worthy of listening to and players like Nate Smith, Robert Glasper, Zac Cockrell, Lloyd Buchanan, Lavinia Meijer, Paul Horton, Rob Moose and Larry Goldings provided the musicianship that was needed to share them with you. Some songs on this record are years old that were just sitting on my laptop, forgotten, waiting to come to life. Some of them I wrote in a tiny green house in Topanga, CA during a heatwave. I was inspired by traveling across the United States. I saw many beautiful things and many heartbreaking things: poverty, loneliness, discouraged people, empty and poor towns. And of course the great swathes of natural, untouched lands. Huge pink mountains, seemingly endless lakes, soaring redwoods and yellow plains that stretch for thousands of acres. There were these long moments of silence in the car when I could sit and reflect. I wondered what it was I wanted for myself next. I suppose all I want is to help others feel a bit better about being. All I can offer are my own stories in hopes of not only being seen and understood, but also to learn to love my own self as if it were an act of resistance. Resisting that annoying voice that exists in all of our heads that says we aren’t good enough, talented enough, beautiful enough, thin enough, rich enough or successful enough. The voice that amplifies when we turn on our TVs or scroll on our phones. It’s empowering to me to see someone be unapologetically themselves when they don’t fit within those images. That’s what I want for myself next and that’s why I share with you, “Jaime”. Brittany Howard

In January 2018, Will Oldham joined his wife on a month-long artist residency on the rim of Hawaii’s Kilauea volcano. When taking breaks from her own work, she’d provide her husband with creative prompts by posting future song titles to the wall of their cottage. “We essentially had a big grocery list,” Oldham tells Apple Music, “and every day, at what were sometimes frustratingly random times because I\'d be chomping at the bit, she would write down a song title. And I would think, ‘Okay, well, how do I focus all of my ideas to fit that?’” So began the writing of *I Made a Place*, Oldham’s first LP of original songs under the Bonnie “Prince” Billy alias in nearly a decade. Recorded later in Louisville—with key contributions from Nathan Salsburg, Joan Shelley, and Jacob Duncan—it’s one of the Kentucky singer-songwriter\'s most disarming works to date, influenced in large part by the arrival of his daughter. “I’ll be 50 years old at the beginning of next year, and I am at a point where I\'m happy to yield a significant amount of my space to another person, to my wife and our child,” he says. “Where a lot of my records before were almost built consciously on a foundation of uncertainty, this album—its major keys and its melodies—is a closed space without a lot of loose ends. It seems like we try to do things differently for our children, and one thing that I would like to do is to give her the authority to feel a degree of certainty. It’s all built on this idea of wanting to make something good enough for her.” Here, Oldham guides us through the album track by track. **New Memory Box** “‘New Memory Box’ is a little reference to ‘New Partner,’ a song we recorded for *Viva Last Blues* and *Bonnie \"Prince\" Billy Sings Greatest Palace Music*. It’s a song about *being* a song. This was a return to that idea and thinking about some of the better purposes for songs—along the lines of a fight song, but a playful fight song. The ideal is to fulfill: I want to grow up and be a doctor, a lawyer, or an Indian chief, but a song wants to grow up and be something that people rally around or sing along loudly to. I was giving this song the fast track towards a successful career, as something designed to bring joy. I figured that was a good way of starting the whole record out.” **Dream Awhile** “Every once in a while I will know where a song comes from, but it\'s pretty rare. And even rarer is the sense that I don\'t know where it came from but I know that it came from somewhere. I\'ve always felt in listening to \'Dream Awhile\' that there\'s something going on that I\'m pulling from some other song. A couple of people have suggested Tim Hardin’s \'If I Were a Carpenter,\' which surprised me, even though I\'ve listened to it hundreds of times, specifically the Johnny Cash/June Carter Cash recording of it. It does have the same progression, but I feel like there\'s something more. There\'s something dreamy about the way the song moves. Someday I\'m going to remember where it’s stolen from. Or, if not, I must have just had a really great dream one night.” **The Devil’s Throat** “I’m not very good at making small talk, like at parties. And yet, we need to put forth our positions on certain things on a pretty regular basis. ‘Devil\'s Throat\' is a list song, making all of these pronouncements as if they’re intensely considered—about aspects of duality and the human condition—when in fact they’re kind of random. If somebody pushed really hard on any given line, it might just cave in like a sandcastle. I say, ‘The ranger put out good fires, bad fires.’ My wife was arguing with me about what a ranger would do in relationship to fires, and which fires were good and which fires were bad. But it\'s Election Day, you\'ve got to vote.” **Look Backward on Your Future, Look Forward to Your Past** “I haven\'t written really long story songs since the early \'90s, and I’ve wanted to. Something along the lines of an Irish ballad, of songs by Paul Brady or John Prine most of all. \[Prine\] sets up a character for you to follow and he makes it musical and he makes it fun. I wanted to have a song that people could very quickly get caught up in. It’s a story about this poor fellow Richard who came to his realizations just a little bit too late for them to be maximally fulfilling. The idea is that there\'s no such thing as closure and there\'s no such thing as history when it comes to your own fate and your own identity. All things being predetermined and all things being written, we are always one with our fate, and it\'s nice to know that that doesn\'t change anything. It just gives you something to think about: Nothing is futile, because you have your one existence to sculpt.” **I Have Made a Place** “It was important to me to name the record after this song, because of the sentiment of the chorus. I\'ve observed myself throughout life and into the future: In rap music, people describe all these different versions of success, but I know that those would never be success for me. I wouldn\'t fit in any of those places, and so I wanted to try to describe a place that I would recognize as being totally fine and temporary. Everything that you do or have done will not be remembered—the mark you make will be washed away. That\'s something you know is coming, and if you can\'t look forward to it, then you\'ve got to turn your head around, because it\'s something you can completely look forward to. That can be a pretty joyful and liberating idea.” **Squid Eye** “There was a writer who was born in the continental United States named Ian McMillan, and he moved to Hawaii decades ago and began a long career as a fiction writer and teacher at the University of Hawaii. The first time I went to Hawaii in \'99, I found one of his books, a short story collection called *Squid Eye*, and that was a pretty crucial key to unlocking some of the many riches Hawaii has given to me in the subsequent 20 years. It’s about that concept, of someone literally being able to sight an octopus—or where an octopus might be holed up—a skill he calls ‘squid eye.’ This is kind of a kid song, except there\'s just such a jumble of vocabulary in there. How wonderful it would be to hear kids try to wrap their mouths around all that language.” **You Know the One** “There\'s a lot of little chord progressions that different songs share throughout the record, musical themes and lyrical themes that unite it. I was trying to figure out how to use my squid eye and get the gold out of this idea: What is a sweet memory? It doesn\'t have to be a memory of the past, it can be a memory of things that you\'re preparing your memory box for—the things that are yet to happen. People are telling \[my wife and me\] all the time, ‘It\'s going to go by so fast. It all goes by so fast.’ And yet I have this feeling already, our daughter’s going to be a year old in two weeks, and I feel like she\'s been with us forever. Right now it creeps by in this wonderful way where every day is full. When she really starts walking, I can’t wait to hold her hand and walk down the street—I\'m preparing that memory even though I have no idea what that experience will be like.” **This Is Far From Over** “There\'s so much doom presented to us at all times these days about the planet. I don\'t ever hear anybody say that whatever direction the planet goes in, it\'s got to be okay. Why present to our children constantly this idea that they\'re entering this ill-fated, imminent destruction, as opposed to just saying, \'I don\'t know. It\'s exciting.\' We\'re an invasive species, and the more respect that we have for that concept, I think the more chance we have of our children inheriting a sense of justification in their existence rather than feeling like they\'re inherently evil just by being human. It\'s trying to give people like my daughter the idea that even with the world that they\'re inheriting, their capability for exploration and optimism and adventure is no lesser than at any time in the past. It\'s as intense and extreme as it ever has been to master their own identity, even in the face of these things that we think are so horrendous.” **Nothing Is Busted** “I like to call it a para-apocalyptic song, something that goes *along* with an apocalypse. ‘Nothing Is Busted’ begins its own world and ends its own world. It clears the way a little bit, and then we can bring it back to pretty human terms. Making an impossible relationship possible is what it’s all about. We very humbly tackle some pretty grand themes with ‘This Is Far From Over’ and then this clears the air and we can just say, ‘Now look around, and don\'t look into the past and don\'t look into the future, but look at impossibilities that you have to deal with. Make them less impossible.’” **Mama Mama** “The one cover song on the album. It was the inherent mystery of it, this inherent contradiction that attracted me to it. I didn\'t understand the sentiment. It’s a strange relationship from child to parent, and the child being the reassuring one even in the face of tragedy, being the one that has to tell the parent, ‘Everything is going to be okay,’ even as the most terrible things are about to happen, and somehow feeling that they have the authority to tell their mother that.” **The Glow Pt. 3** “Every night on the volcano, when the sun went down, we could see the glow of the lava in this big pit. My wife wrote ‘The Glow’ on the song title list, and I was like, ‘Well, okay, but I’ve got to put it in appropriate sequence,’ so I put it as part seven just because I wasn\'t sure if \[Microphones singer-songwriter\] Phil \[Elverum\] had written more than a couple parts to \[his album\] *The Glow*. I contacted him later and he said, \'Yeah, there\'s only Pt. 1 and Pt. 2, so you can go ahead and call it Pt. 3 if you want.\' It was especially funny, because my wife didn’t know Microphones’ music, and while we were on the volcano, Phil and his daughter came and visited us. She’d written the title up there without any knowledge of its history and its association with these friends of ours who’d visited us.\" **Thick Air** “I still think sometimes that this belongs as the first song on the record. ‘Thick Air’ is all about clearing the air, and it’s a statement of position and purpose. When my wife wrote the title, I\'m sure she was referring to the air that we were trying to breathe, the volcanic fog—or vog. But for more than a decade now, we\'ve been dealing with my mother\'s Alzheimer’s, and that creates an emotional environment. This song imagines what it will be like to breathe the air after my mom is physically gone from the Earth. Even though now it\'s almost two years ago that those lyrics were begun, and she\'s still physically here, it\'s trying to describe a space that is free from prolonged and active grieving.” **Building a Fire** “This record in so many ways is about encouraging us to recognize the ability to define our own spaces. There’s a certain degree of certainty, but there\'s a implication that solitude is not the end goal. The goal has always been to create and identify a community, by throwing the music out into the world and seeing who reacts to it and who picks up on it. When we’re growing up and sitting alone in our rooms listening to a record, we realize, ‘Oh, my universe is much bigger than I thought it was, because the people making this music, they\'re a part of my world, and it\'s reassuring that everything that I know is not limited to this house or this block or this street or this school that I have to go to. There\'s reason to believe that there\'s something beyond what I can see and feel, and there\'s people out there that I can relate to.’”

GQ clothes-horse and man who saw a darkness Bonnie Prince Billy has his first album of new songs since 2011. This time, he brings the lightness, with help from a Louisville band including picker Nathan Salsburg, ex-Gary Burton Quartet drummer Mike Hyman and singer-songwriter Joan Shelley. Influenced by songwriters John Prine and Tom T. Hall and inspired by the state of Hawaii, I Made a Place finds Bonny using his considerable powers for good