“Life seems to provide no end of things to explore without too much investigation,” Laura Marling tells Apple Music. The London singer-songwriter is discussing how, after six albums (three of which were Mercury Prize-nominated), she found the inspiration needed for her seventh, *Song For Our Daughter*. One thing which proved fruitful was turning 30. In an evolution of 2017’s exquisite rumination on womanhood *Semper Femina*, growing, as she says, “a bit older” prompted Marling to consider how she might equip her her own figurative daughter to navigate life’s complexities. “In light of the cultural shift, you go back and think, ‘That wasn’t how it should have happened. I should have had the confidence and the know-how to deal with that situation in a way that I didn’t have to come out the victim,’” says Marling of the album’s central message. “You can’t do anything about it, obviously, so you can only prepare the next generation with the tools and the confidence \[to ensure\] they \[too\] won’t be victims.” This feeling reaches a crescendo on the title track, which sees Marling consider “our daughter growing old/All of the bullshit that she might be told” amid strings that permeate the entire record. While *Song for Our Daughter* is undoubtedly a love letter to women, it is also a deeply personal album where whimsical melodies (“Strange Girl”) collide with Marling at her melancholic best (the gorgeously sparse “Blow by Blow”—a surprisingly honest chronicle of heartbreak—or the exceptional, haunting “Hope We Meet Again”). And its roaming nature is exactly how Marling wanted to soundtrack the years since *Semper Femina*. “There is no cohesive narrative,” she admits. “I wrote this album over three years, and so much had changed. Of course, no one knows the details of my personal life—nor should they. But this album is like putting together a very fragmented story that makes sense to me.” Let Marling guide you through that story, track by track. **Alexandra** “Women are so at the forefront of my mind. With ‘Alexandra,’ I was thinking a lot about the women who survive the projected passion of so-called ‘great men.’ ‘Alexandra’ is a response to Leonard Cohen’s ‘Alexandra Leaving,’ but it’s also the idea that for so long women have had to suffer the very powerful projections that people have put on them. It’s actually quite a traumatizing experience, I think, to only be seen through the eyes of a man’s passion; just as a facade. And I think it happens to women quite often, so in a couple of instances on this album I wanted to give voice to the women underneath all of that. The song has something of Crosby, Stills & Nash about it—it’s a chugging, guitar-riffy job.” **Held Down** “Somebody said to me a couple of years ago that the reason why people find it hard to attach to me \[musically\] is that it\'s not always that fun to hear sad songs. And I was like, ‘Oh, well, I\'m in trouble, because that\'s all I\'ve got!’ So this song has a lightness to it and is very light on sentiment. It’s just about two people trying to figure out how to not let themselves get in the way of each other, and about that constant vulnerability at the beginning of a relationship. The song is almost quite shoegazey and is very simple to play on the guitar.” **Strange Girl** “The girl in this song is an amalgamation of all my friends and I, and of all the things we\'ve done. There’s something sweet about watching someone you know very well make the same mistakes over and over again. You can\'t tell them what they need to know; they have to know it themselves. That\'s true of everyone, including myself. As for the lyrics about the angry, brave girl? Well, aren’t we all like that? The fullness and roundness of my experience of women—the nuance and all the best and worst things about being a complicated little girl—is not always portrayed in the way that I would portray it, and I think women will recognize something in this song. My least favorite style of music is Americana, so I was conscious to avoid that sound here. But it’s a lovely song; again, it has chords which are very Crosby, Stills & Nash-esque.” **Only the Strong** “I wanted the central bit of the album to be a little vulnerable tremble, having started it out quite boldly. This song has a four-beat click in it, which was completely by accident—it was coming through my headphones in the studio, so it was just a happy accident. The strings on this were all done by my bass player Nick \[Pini\] and they are all bow double-bass strings. They\'re close to the human voice, so I think they have a specific, resonant effect on people. I also went all out on the backing vocals. I wanted it to be my own chorus, like my own subconscious backing me up. The lyric ‘Love is a sickness cured by time\' is actually from a play by \[London theater director\] Robert Icke, though I did ask his permission to use it. I just thought that was the most incredible ointment to the madness of infatuation.” **Blow by Blow** “I wrote this song on the piano, but it’s not me playing here—I can\'t play the piano anywhere near as well as my friend Anna here. This song is really straightforward, and I kind of surprised myself by that. I don\'t like to be explicit. I like to be a little bit opaque, I guess, in the songwriting business. So this is an experiment, and I still haven’t quite made my mind up on how I feel about it. Both can exist, but I think what I want from my music or art or film is an uncanny familiarity. This song is a different thing for me, for sure—it speaks for itself. I’d be rendering it completely naked if I said any more.” **Song for Our Daughter** “This song is kind of the main event, in my mind. I actually wrote it around the time of the Trayvon Martin \[shooting in 2012\]. All these young kids being unarmed and shot in America. And obviously that\'s nothing to do with my daughter, or the figurative daughter here, but I \[was thinking about the\] institutional injustice. And what their mothers must be feeling. How helpless, how devastated and completely unable to have changed the course of history, because nothing could have helped them. I was also thinking about a story in Roman mythology about the Rape of Lucretia. She was the daughter of a nobleman and was raped—no one believed her and, in that time, they believed that if you had been ‘spoilt’ by something like that, then your blood would turn black. And so she rode into court one day and stabbed herself in the heart, and bled and died. It’s not the cheeriest of analogies, but I found that this story that existed thousands of years ago was still so contemporary. The strings were arranged by \[US instrumentalist, arranger, and producer\] Rob Moose, and when he sent them to me he said, ‘I don\'t know if this is what you wanted, but I wanted to personify the character of the daughter in the strings, and help her kind of rise up above everything.’ And I was like, ‘That\'s amazing! What an incredible, incredible leap to make.’ And that\'s how they ended up on the record.” **Fortune** “Whenever I get stuck in a rut or feel uninspired on the guitar, I go and play with my dad, who taught me. He was playing with this little \[melody\]—it\'s just an E chord going up the neck—so I stole it and then turned it into this song. I’m very close with my sisters, and at the time we were talking and reminiscing about the fact that my mother had a ‘running-away fund.’ She kept two-pence pieces in a pot above the laundry machine when we were growing up. She had recently cashed it in to see how much money she had, and she had built up something like £75 over the course of a lifetime. That was her running-away fund, and I just thought that was so wonderfully tragic. She said she did it because her mother did it. It was hereditary. We are living in a completely different time, and are much closer to equality, so I found the idea of that fund quite funny.” **The End of the Affair** “This song is loosely based on *The End of the Affair* by Graham Greene. The female character, \[Sarah\], is elusive; she has a very secret role that no one can be part of, and the protagonist of the book, the detective \[Maurice Bendrix\], finds it so unbearably erotic. He finds her secretness—the fact that he can\'t have her completely—very alluring. And in a similar way to ‘Alexandra Leaving,’ it’s about how this facade in culture has appeared over women. I was also drawing on my own experience of great passions that have to die very quietly. What a tragedy that is, in some ways, to have to bear that alone. No one else is obviously ever part of your passions.” **Hope We Meet Again** “This was actually the first song we recorded on the album, so it was like a tester session. There’s a lot of fingerpicking on this, so I really had to concentrate, and it has pedal steel, which I’m not usually a fan of because it’s very evocative of Americana. I originally wrote this for a play, *Mary Stuart* by Robert Icke, who I’ve worked with a lot over the last couple of years, and adapted the song to turn it back into a song that\'s more mine, rather than for the play. But originally it was supposed to highlight the loneliness of responsibility of making your own decisions in life, and of choosing your own direction. And what the repercussions of that can sometimes be. It\'s all of those kind of crossroads where deciding to go one way might be a step away from someone else.” **For You** “In all honesty, I think I’m getting a bit soft as I get older. And I’ve listened to a lot of Paul McCartney and it’s starting to affect me in a lot of ways. I did this song at home in my little bunker—this is the demo, and we just kept it exactly as it was. It was never supposed to be a proper song, but it was so sweet, and everyone I played it to liked it so much that we just stuck it on the end. The male vocals are my boyfriend George, who is also a musician. There’s also my terrible guitar solo, but I left it in there because it was so funny—I thought it sounded like a five-year-old picking up a guitar for the first time.”

Laura Marling’s exquisite seventh album Song For Our Daughter arrives almost without pre-amble or warning in the midst of uncharted global chaos, and yet instantly and tenderly offers a sense of purpose, clarity and calm. As a balm for the soul, this full-blooded new collection could be posited as Laura’s richest to date, but in truth it’s another incredibly fine record by a British artist who rarely strays from delivering incredibly fine records. Taking much of the production reins herself, alongside long-time collaborators Ethan Johns and Dom Monks, Laura has layered up lush string arrangements and a broad sense of scale to these songs without losing any of the intimacy or reverence we’ve come to anticipate and almost take for granted from her throughout the past decade.

It took Kelly Lee Owens 35 days to write the music for her second album. “I had a flood of creation,” she tells Apple Music. “But this was after three years that included loss, learning how to deal with loss and how to transmute that loss into something of creation again. They were the hardest three years of my life.” The Welsh electronic musician’s self-titled 2017 debut album figured prominently on best-of-the-year lists and won her illustrious fans across music and fashion. It’s the sort of album you recommend to people you’d like to impress. Its release, however, was clouded by issues in Owens’ personal life. “There was a lot going on, and it took away my energy,” she says. “It made me question the integrity of who I was and whether it was ego driving certain situations. It was so tough to keep moving forward.” Fortunately, Owens rallied. “It sounds hippie-dippie, but this is my purpose in life,” she says. “To convey messages via sounds and to connect to other people.” Informed by grief, lust, anxiety, and environmental concerns, *Inner Song* is an electronic album that impacts viscerally. “I allowed myself to be more of a vessel that people talk about,” she says. “It’s real. Ideas can flow through you. In that 35-day period, I allowed myself to tap into any idea I had, rather than having to come in with lyrics, melodies, and full production. It’s like how the best ideas come when you’re in the shower: You’re usually just letting things be and come through you a bit more. And then I could hunker down and go in hard on all those minute nudges on vocal lines or kicks or rhythmical stuff or EQs. Both elements are important, I learned. And I love them both.” Here, Owens treats you to a track-by-track guide to *Inner Song*. **Arpeggi** “*In Rainbows* is one of my favorite albums of all time. The production on it is insane—it’s the best headphone *and* speaker listening experience ever. This cover came a year before the rest of the album, actually. I had a few months between shows and felt like I should probably go into the studio. I mean, it’s sacrilege enough to do a Radiohead cover, but to attempt Thom’s vocals: no. There is a recording somewhere, but as soon as I heard it, I said, ‘That will never been heard or seen. Delete, delete, delete.’ I think the song was somehow written for analog synths. Perhaps if Thom Yorke did the song solo, it might sound like this—especially where the production on the drums is very minimal. So it’s an homage to Thom, really. It was the starting point for me, and this record, so it couldn’t go anywhere else.” **On** “I definitely wanted to explore my own vocals more on this album. That ‘journey,’ if you like, started when Kieran Hebden \[Four Tet\] requested I play before him at a festival and afterwards said to me, ‘Why the fuck have you been hiding your vocals all this time under waves of reverb, space echo, and delay? Don’t do that on the next album.’ That was the nod I needed from someone I respect so highly. It’s also just been personal stuff—I have more confidence in my voice and the lyrics now. With what I’m singing about, I wanted to be really clear, heard, and understood. It felt pointless to hide that and drown it in reverb. The song was going to be called ‘Spirit of Keith’ as I recorded it on the day \[Prodigy vocalist\] Keith Flint died. That’s why there are so many tinges of ’90s production in the drums, and there’s that rave element. And almost three minutes on the dot, you get the catapult to move on. We leap from this point.” **Melt!** “Everyone kept taking the exclamation mark out. I refused, though—it’s part of the song somehow. It was pretty much the last song I made for the album, and I felt I needed a techno banger. There’s a lot of heaviness in the lyrics on this album, so I just wanted that moment to allow a letting loose. I wanted the high fidelity, too. A lot of the music I like at the moment is really clear, whereas I’m always asking to take the top end off on the snare—even if I’m told that’s what makes something a snare. I just don’t really like snares. The ‘While you sleep, melt, ice’ lyrics kept coming into my head, so I just searched for ‘glacial ice melting’ and ‘skating on ice’ or ‘icicles cracking’ and found all these amazing samples. The environmental message is important—as we live and breathe and talk, the environment continues to suffer, but we have to switch off from it to a certain degree because otherwise you become overwhelmed and then you’re paralyzed. It’s a fine balance—and that’s why the exclamation mark made so much sense to me.” **Re-Wild** “This is my sexy stoner song. I was inspired by Rihanna’s ‘Needed Me,’ actually. People don’t necessarily expect a little white girl from Wales to create something like this, but I’ve always been obsessed with bass so was just wanting a big, fat bassline with loads of space around it. I’d been reading this book *Women Who Run With the Wolves* \[by Clarissa Pinkola\], which talks very poetically about the journey of a woman through her lifetime—and then in general about the kind of life, death, and rebirth cycle within yourself and relationships. We’re always focused on the death—the ending of something—but that happens again and again, and something can be reborn and rebirthed from that, which is what I wanted to focus on. She \[Pinkola\] talks about the rewilding of the spirit. So often when people have depression—unless we suffer chronically, which is something else—it’s usually when the creative soul life dies. I felt that mine was on the edge of fading. Rewilding your spirit is rewilding that connection to nature. I was just reestablishing the power and freedoms I felt within myself and wanting to express that and connect people to that inner wisdom and power that is always there.” **Jeanette** “This is dedicated to my nana, who passed away in October 2019, and she will forever be one of the most important people in my life. She was there three minutes after I was born, and I was with her, holding her when she passed. That bond is unbreakable. At my lowest points she would say, ‘Don’t you dare give this up. Don’t you dare. You’ve worked hard for this.’ Anyway, this song is me letting it go. Letting it all go, floating up, up, and up. It feels kind of sunshine-y. What’s fun for me—and hopefully the listener—is that on this album you’re hearing me live tweaking the whole way through tracks. This one, especially.” **L.I.N.E.** “Love Is Not Enough. This is a deceivingly pretty song, because it’s very dark. Listen, I’m from Wales—melancholy is what we do. I tried to write a song in a minor key for this album. I was like, ‘I want to be like The 1975’—but it didn’t happen. Actually, this is James’ song \[collaborator James Greenwood, who releases music as Ghost Culture\]. It’s a Ghost Culture song that never came out. It’s the only time I’ve ever done this. It was quite scary, because it’s the poppiest thing I’ve probably done, and I was also scared because I basically ended up rewriting all the lyrics, and re-recorded new kick drums, new percussion, and came up with a new arrangement. But James encouraged all of it. The new lyrics came from doing a trauma body release session, which is quite something. It’s someone coming in, holding you and your gaze, breathing with you, and helping you release energy in the body that’s been trapped. Humans go through trauma all the time and we don’t literally shake and release it, like animals do. So it’s stored in the body, in the muscles, and it’s vital that we figure out how to release it. We’re so fearful of feeling our pain—and that fear of pain itself is what causes the most damage. This pain and trauma just wants to be seen and acknowledged and released.” **Corner of My Sky (feat. John Cale)** “This song used to be called ‘Mushroom.’ I’m going to say no more on that. I just wanted to go into a psychedelic bubble and be held by the sound and connection to earth, and all the, let’s just say, medicine that the earth has to offer. Once the music was finished, Joakim \[Haugland, founder of Owens’ label, Smalltown Supersound\] said, ‘This is nice, but I can hear John Cale’s voice on this.’ Joakim is a believer that anything can happen, so we sent it to him knowing that if he didn’t like it, he wouldn’t fucking touch it. We had to nudge a bit—he’s a busy man, he’s in his seventies, he’s touring, he’s traveling. But then he agreed and it became this psychedelic lullaby. For both of us, it was about the land and wanting to go to the connection to Wales. I asked if he could speak about Wales in Welsh, as it would feel like a small contribution from us to our country, as for a long time our language was suppressed. He then delivered back some of the lyrics you hear, but it was all backwards. So I had to go in and chop it up and arrange it, which was this incredibly fun challenge. The last bit says, ‘I’ve lost the bet that words will come and wake me in the morning.’ It was perfect. Honestly, I feel like the Welsh tourist board need to pay up for the most dramatic video imaginable.” **Night** “It’s important that I say this before someone else does: I think touring with Jon Hopkins influenced this one in terms of how the synth sounded. It wasn’t conscious. I’ve learned a lot of things from him in terms of how to produce kicks and layer things up. It’s related to a feeling of how, in the nighttime, your real feelings come out. You feel the truth of things and are able to access more of yourself and your actual soul desires. We’re distracted by so many things in the daytime. It’s a techno love song.” **Flow** “This is an anomaly as it’s a strange instrumental thing, but I think it’s needed on the album. This has a sample of me playing hand drum. I actually live with a sound healer, so we have a ceremony room and there’s all sorts of weird instruments in there. When no one was in the house, I snuck in there and played all sorts of random shit and sampled it simply on my iPhone. And I pitched the whole track around that. It fits at this place on the record, because we needed to come back down. It’s a breathe-out moment and a restful space. Because this album can truly feel like a journey. It also features probably my favorite moment on the album—when the kick drums come back in, with that ‘bam, bam, bam, bam.’ Listen and you’ll know exactly where I mean.” **Wake-Up** “There was a moment sonically with me and this song after I mixed it, where the strings kick in and there’s no vocals. It’s just strings and the arpeggio synth. I found myself in tears. I didn’t know that was going to happen to me with my own song, as it certainly didn’t happen when I was writing it. What I realized was that the strings in that moment were, for me, the earth and nature crying out. Saying, ‘Please, listen. Please, see what’s happening.’ And the arpeggio, which is really chaotic, is the digital world encroaching and trying to distract you from the suffering and pain and grief that the planet is enduring right now. I think we’re all feeling this collective grief that we can’t articulate half the time. We don’t even understand that we are connected to everyone else. It’s about tapping into the pain of this interconnected web. It’s also a commentary on digital culture, which I am of course a part of. I had some of the lyrics written down from ages ago, and they inspired the song. ‘Wake up, repeat, again.’ Just questioning, in a sense, how we’ve reached this place.”

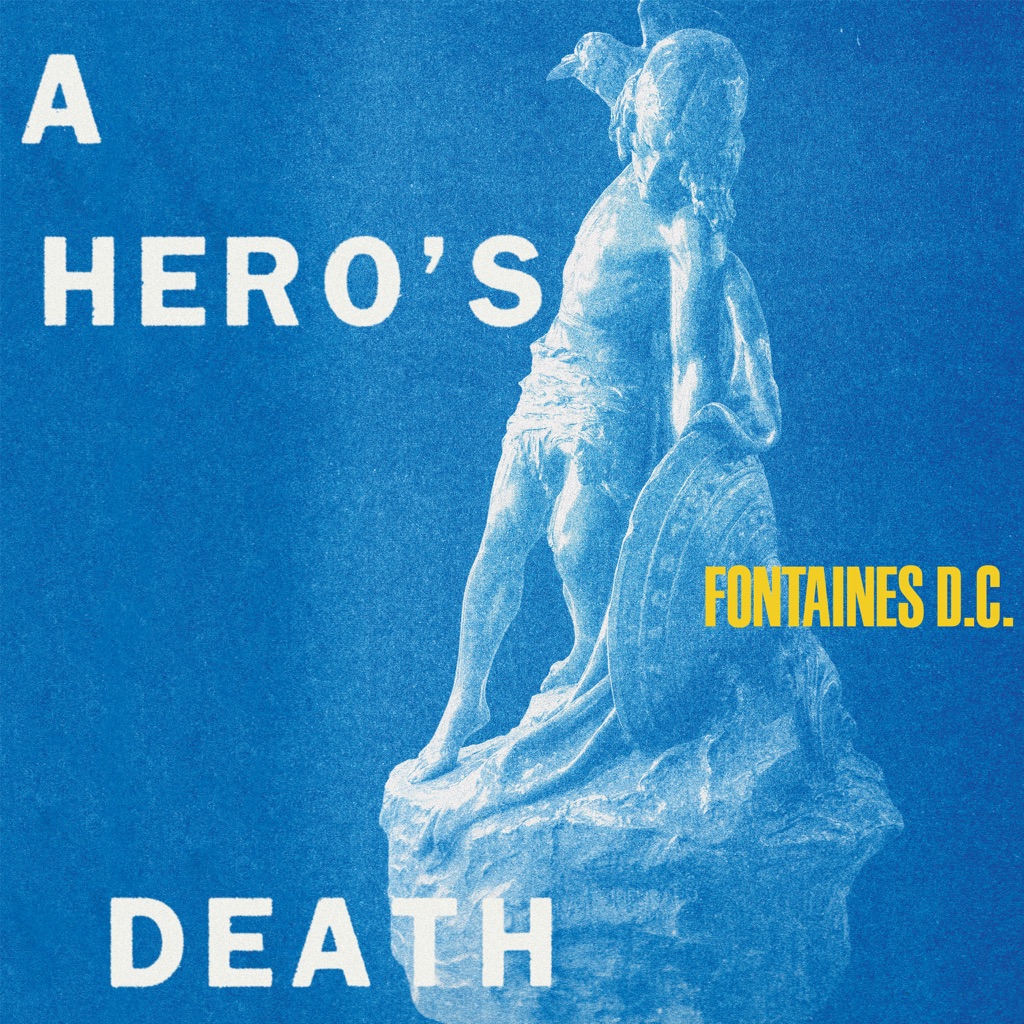

Fontaines D.C. singer Grian Chatten was with bandmates Tom Coll and Conor Curley in a pub somewhere in the US when the words “Happy is living in a closed eye” came to him. It was possibly in Chicago, he thinks, and certainly during their 2019 tour. “We were playing pool and drinking some shit Guinness,” he tells Apple Music. “I was drinking an awful lot and there was a sense of running away on that tour—because we were so overworked. The gigs were really good and full of energy, but it almost felt like a synthetic, anxious energy. We were all burning the candle at both ends. I think my subconscious was trying to tell me when I wrote that line that I was not really facing reality properly. Ever since I\'ve read Oscar Wilde, I\'ve always been fascinated by questioning the validity of living soberly or healthily.” The line eventually made its way into “Sunny” a track from the band’s second album *A Hero’s Death*. Like much of the record, that unsteady waltz is an absorbing departure from the rock ’n’ roll punch of their Mercury-nominated debut, *Dogrel*. Released in April 2019, *Dogrel* quickly established the Irish five-piece as one of the most exciting guitar bands on their side of the Atlantic, throwing them into an exacting tour and promo schedule. When the physical and mental strains of life on the road bore down—on many nights, Chatten would have to visit dark memories to reengage with the thoughts and feelings behind some songs—the five-piece sought relief and refuge in other people’s music. “We found ourselves enjoying mostly gentler music that took us out of ourselves and calmed us down, took us away from the fast-paced lifestyle,” says Chatten. “I think we began to associate a particular sound and kind of music, one band in particular would have been The Beach Boys, that helped us feel safe and calm and took us away from the chaos.” That, says Chatten, helps account for the immersive and expansive sound of *A Hero’s Death*. With their world being refracted through the heat haze of interstate highways and the disconcerting fog of days without much sleep, there’s a dreaminess and longing in the music. It’s in the percussive roll of “Love Is the Main Thing” and the harmonies swirling around the title track’s rigorous riffs. It drifts through the uneasy reflection of “Sunny.” “‘Sunny’ is hard for me to sing,” says Chatten, “just because there are so many long fucking notes. And I have up until recently been smoking pretty hard. But I enjoy the character that I feel when I sing it. I really like the embittered persona and the gin-soaked atmosphere.” While *Dogrel*’s lyrics carried poetic renderings of life in modern Dublin, *A Hero’s Death* burrows inward. “Dublin is still in the language that I use, the colloquialisms and the way that I express things,” says Chatten. “But I consider this to be much more a portrait of an inner landscape. More a commentary on a temporal reality. It\'s a lot more about the streets within my own mind.” Throughout, Chatten can be found examining a sense of self. He does it with bracing defiance on “I Don’t Belong” and “I Was Not Born,” and with aching resignation on “Oh Such a Spring”—a lament for people who go to work “just to die.” ”I worked a lot of jobs that gave me no satisfaction and forced me to shelve temporarily who I was,” says Chatten. “I felt very strongly about people I love being in the service industry and having to become somebody else and suppress their own feelings and their own views, their own politics, to make a living. How it feels after a shift like that, that there is blood on your hands almost. You’re perpetuating this lie, because it’s a survival mechanism for yourself.” Ambitious and honest, *A Hero’s Death* is the sound of a band protecting their ideals when the demands of being rock’s next big thing begin to exert themselves. ”One of the things we agreed upon when we started the band was that we wouldn\'t write a song unless there was a purpose for its existence,” says Chatten. “There would be no cases of churning anything out. It got to a point, maybe four or five tunes into writing the album, where we realized that we were on the right track of making art that was necessary for us, as opposed to necessary for our careers. We realized that the heart, the core of the album is truthful.”

The West Midlands-born and London-based electronic duo Delmer Darion (comprising Oliver Jack and Tom Lenton) announce their debut album ‘Morning Pageants’ will be released on the 16th October via Practise Music. Their debut album has been five years in the making: a sprawling, industrial ten-track account of the death of the devil, inspired by a line in the Wallace Stevens poem ‘Esthétique du Mal’: “The death of Satan was a tragedy for the imagination.” A vast aural landscape is covered from the opening melodies coded in the constructed language of Solresol. When sequenced together, ‘Morning Pageants’ is shrouded in the same intricate noise of self-sampling and tape degradation. De-centred rhythmic assemblies of analogue drum machines play through a series of guitar pedals, thunderous bass swells from a self oscillating filter feedback patch, and folk songs dissolve into thin air. The artwork for Morning Pageants was designed by Oliver, based from a series of 16th Century prints called “The Dance of Death” by Hans Holbein, depicting different people being led away by Death. Recreating one of the prints, he replaced the figure being led away with an original drawing of Satan. The final artwork is printed on Nepalese Lokta paper, a waxy yellow paper that has been used for lots of sacred texts. Even if you’re not following the descent of the devil step by step through their unspooling archives, you’ll have little chance not to be transfixed.

You don’t need to know that Fiona Apple recorded her fifth album herself in her Los Angeles home in order to recognize its handmade clatter, right down to the dogs barking in the background at the end of the title track. Nor do you need to have spent weeks cooped up in your own home in the middle of a global pandemic in order to more acutely appreciate its distinct banging-on-the-walls energy. But it certainly doesn’t hurt. Made over the course of eight years, *Fetch the Bolt Cutters* could not possibly have anticipated the disjointed, anxious, agoraphobic moment in history in which it was released, but it provides an apt and welcome soundtrack nonetheless. Still present, particularly on opener “I Want You to Love Me,” are Apple’s piano playing and stark (and, in at least one instance, literal) diary-entry lyrics. But where previous albums had lush flourishes, the frenetic, woozy rhythm section is the dominant force and mood-setter here, courtesy of drummer Amy Wood and former Soul Coughing bassist Sebastian Steinberg. The sparse “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” is backed by drumsticks seemingly smacking whatever surface might be in sight. “Relay” (featuring a refrain, “Evil is a relay sport/When the one who’s burned turns to pass the torch,” that Apple claims was excavated from an old journal from written she was 15) is driven almost entirely by drums that are at turns childlike and martial. None of this percussive racket blunts or distracts from Apple’s wit and rage. There are instantly indelible lines (“Kick me under the table all you want/I won’t shut up” and the show-stopping “Good morning, good morning/You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in”), all in the service of channeling an entire society’s worth of frustration and fluster into a unique, urgent work of art that refuses to sacrifice playfulness for preaching.

Jarvis Cocker’s band Pulp might have been one of the defining groups of the mid-’90s Britpop era, but there was something distinctly different about them. In a sea of bands fixated on the past, Pulp’s landmark 1995 album *Different Class* was, musically and lyrically, a step forward. They weren’t the only band taking a critical look at British society, but Cocker was constantly turning his gaze inward. In his songwriting, relationships were messy, memories weren’t always to be trusted, the drugs often had the opposite of their intended effect, and even the losers got lucky—more than just sometimes. On two albums to follow, the Sheffield group would cut further left—and Cocker would go on to explore many more avenues of expression. Two solo albums in 2006 and 2009 (as well as writing most of Charlotte Gainsbourg’s beautiful *5:55*) only further showcased his range—and that’s before he occupied himself as a book editor, a BBC radio host, and, during the COVID-19 shutdown, a housebound orator of great literary works. (Google “Jarvis Cocker’s Bedtime Stories” to hear his soothing baritone recite Brautigan and Salinger.) On the heels of his collaborative project with Chilly Gonzales, 2017’s *Room 29*, Cocker was invited by Sigur Rós to perform at a festival in Reykjavík. He quickly assembled an entirely new London-based group of musicians to work through song sketches he’d developed over the last few years, which became the band-in-progress JARV IS…—emphasis on those three trailing dots. “Usually you put that into a sentence when you are implying that something isn\'t quite finished,” Cocker tells Apple Music. “The whole point of this band was to finish off these ideas for songs that I\'d had for quite a long time but wasn\'t able to bring to fruition on my own.” At a trim seven songs, *Beyond the Pale* still manages to explore a range of themes, most of which revolve around the modern human condition—from aging to FOMO and self-doubt to living in the wake of a bygone era. Evolution plays a big part, too—not just in the subject matter, but in how the music took shape: “Because we were doing this experiment of trying to finish off a record by playing it to people, it seemed logical that we should record the shows so we could see how we were getting on,” he says of what would become “Must I Evolve?”, which was recorded live in an actual cave in Castleton, Derbyshire. “A light bulb went off in my head then, because that\'s every artist\'s dream, really—to make a record without even realizing it. To not go through that self-conscious phase where you go into a studio and start questioning things and the song gets away from you.” Here, Cocker tells us how the rest of the songs came together. **Save the Whale** \"You\'re not the first person to say there\'s a similarity to Leonard Cohen, which I take as a massive compliment, because he\'s really been an artistic touchstone for me, all through my career. There are some artists that show you different ideas of what a song can be, and open up your perceptions of what a song can be. Especially for someone like me, who was basically brought up on pop radio, which lyrically isn\'t very adventurous. So what Leonard Cohen did with words in songs was something that really had an effect on me. But what\'s exciting for me was all the time that I was in Pulp, I was the only person in the band who sang. And in this band, basically everybody sings, especially Serafina \[Steer, harpist\] and Emma \[Smith, violinist/guitarist\]. Rather than it being a monologue, I can tie in other viewpoints with what they say. And sometimes it will reinforce it, sometimes it will undercut it, sometimes it will just comment on it. And it\'s a lot of fun writing that way, because suddenly you\'re writing a dialogue or conversation rather than just me, me, me all the time.\" **Must I Evolve?** \"The starting point for it was me thinking about the development of a relationship, from meeting someone to moving in with them and stuff like that. You could draw a parallel with evolution itself, of two cells splitting and then those cells divide more and then you start to get organisms and eventually you\'ve got some fish and then the fish grows legs and somehow comes out... I guess I was just remembering biology textbooks from school. The idea of the ascendant man, stuff like that. The Big Bang. That was a bit of a joke I had with myself, with the meanings of \'bang.\' Banging, like \'Who\'ve been banging lately,\' and the Big Bang that started the whole of human creation off. Two of the longest songs on the record are questions: \'Must I Evolve?\' and \'Am I Missing Something?\' I guess I\'m at an age where I ask myself those kind of questions, and the songs were some type of attempt on my part to answer those questions. But this really was the key song because it was the first one that we finished and released, and also the call-and-response theme came from this song, because I\'d already written the \'Must I evolve? Must I change? Must I develop?\' But there was no answer to that. We were just rehearsing and I think it was Serafina started going, \'Yes, yes, yes,\' I think as a bit of a joke. And then I thought, \'That\'s such a great idea, let\'s just do that.\' That totally added a new dimension to the song.\" **Am I Missing Something?** \"It\'s in that tradition, I suppose, of those long songs where it very directly addresses the listener. This is the oldest song on the record; the lyrics were written pretty much eight years ago. I wanted to try a bit of a different approach, and so the lyrics aren\'t so much a through narrative; it\'s not just one story. It jumps around a bit. And that seemed appropriate because it\'s about this idea of \'Am I missing something?\' It could mean there\'s something really interesting going on but I don\'t know about it, which is like a modern disease: Too many entertainment and information options to choose from. It can also be like, \'Do I lack something? Is there something missing in me? Do I need to fill some gaping psychological hole within myself or whatever?\' Or actually, ‘Am I overlooking something, am I not getting something?’ That\'s a really important part of a song, that you have to leave some space in it for the person listening to do what they want with it.” **House Music All Night Long** \"People have said, ‘Yes, it\'s a COVID anthem,’ but it wasn\'t conceived in that way at all. For a start, it was written two years ago before anybody was really thinking about any pandemic. It was really just one weekend where I was stuck in London. It was a very hot weekend and everyone I knew had left town. I was in this house on my own and some friends had gone to a house music festival in Wales and I was jealous of that. I was having—people call it FOMO, don\'t they? I just thought to myself, \'Don\'t just sit here feeling sorry for yourself, do something to get yourself out of this trough you\'ve found yourself in.\' So I remembered that there was a secondhand keyboard that I\'d bought from a street market just a few weeks before and it was down in the basement of this house. So I went and found it, brought it up, plugged it in, put it through an amp, and just started trying to write bits of music. I came up with the chord pattern that the song starts off with, and because this keyboard—it\'s an old string machine, so it\'s got a quite naive sound to it, which reminded me of some of those early house records where they would use big, almost symphonic-sounding things but on really crap keyboards. The first chord change really reminded me of something like \'Promised Land\' by Joe Smooth or something like that. So maybe it was because I was thinking about my friends who were having a good time at a rave. Again, once I\'ve got that idea of the two meanings of \'house\'—like, house music and then \'house\' as in a building that you live in. I was stuck in a house feeling sorry for myself whilst my friends were out dancing to house, probably having a great time, as far as I was imagining. And so then the song had already half written itself once I got those basic ideas down.\" **Sometimes I Am Pharaoh** \"I developed a fascination with these street entertainers—human statues. You tend to get them outside famous buildings or in tourist hotspots. So you either get somebody dressed up as Charlie Chaplin—that\'s why it\'s \'Sometimes I\'m Pharaoh/Sometimes I\'m Chaplin.\' And they stand still and then a crowd gathers and eventually they move and everybody screams and hopefully gives them some money. It died out a little bit in more recent years. They’ve been superseded slightly by those levitating guys—have you seen those ones? Where it\'s like Yoda floating, and he\'s holding a stick but obviously the stick—there\'s some kind of platform under him. And I feel sorry for the statue guys, because the levitating Yoda, it\'s just like, anybody could do that. You just go and buy the weird frame—which has obviously got some kind of really heavy base so that it doesn\'t topple over—and you\'re in business. Whereas to actually stand still for hours on end must be really difficult. I was just showing some respect and love to the people that were doing that.\" **Swanky Modes** \"My son \[who lives in France\] goes to this once-a-week rock school. It\'s run by a guy from Brooklyn who moved over to Paris. I\'ve become friendly with him, and he asked me if I would come to the class and help the kids write a song in the space of an hour or something. So we met to talk about how that could work, and then we\'re jamming around and he was playing the piano and I was messing around on the bass and then we started playing what became \'Swanky Modes,\' which is really not a kids\' song at all. The piano that you hear on the record is him, Jason Domnarski. And the first half of the song has got my bass playing on it. So it\'s almost like a field recording. This is probably the most narrative-driven song on the record. Somehow all these events that happened to me at very specific periods of time, which was when I was living in Camden in London, just towards the end of my time at Saint Martins art college, so we\'re talking about 1991. I was only living there for maybe eight months, and all these images from my time of living there suddenly came into my mind really, really clearly. The title of the song, \'Swanky Modes,\' it\'s the name of the shop. It was a women\'s clothes shop that was near where I was living at the time. Again, that\'s one of the mysteries of songwriting—why suddenly, almost 30 years later, these words would come to me that summed up a fairly minor chapter in my life. But it came back in really minute detail and I\'m really glad it did, because now I\'ll never forget that period on my life, because I\'ve got a souvenir of it.\" **Children of the Echo** \"A few years ago I was asked to write a review of a book called *The John Lennon Letters*. I\'m a Beatles fan, and particularly of John Lennon, so I thought if John Lennon wrote lots of letters, I\'d really like to see them. So I was sent an advance copy of the book, and it was just weird. They weren\'t letters. Some of them were just \'Tell Dave to get lasagna from supermarket. Walk dog.\' They were just to-do notes, like a Post-it note that you would put on your refrigerator to remind you to do something. They weren\'t letters. So I was really, really disappointed with this book, so I tried to express this in the review. And this phrase \'children of the echo\' came into my mind, which in the context of the article was talking about how someone in my position—I can\'t really remember The Beatles, because I was a kid. I was born in 1963, when they first broke through, and then they broke up in 1970 when I was seven. They were there, but I couldn\'t really be actively a fan or anything like that. But they left such a mark and they made such an impact that the ripples obviously were coming out and affected everybody a lot. And this made me think of this idea of an echo, of a sound which would be like The Beatles, this amazing sound that changed everything. And then I consider myself to be a child of the echo because I was brought up in the aftermath of that. And I was thinking, \'Well, we\'ve got to get beyond that,\' because that was the problem with that thing that got called Britpop in the UK—that it was so in thrall to the \'60s and The Beatles in particular that it killed it. It stopped it from being what could\'ve been a really forward-thinking and exciting and innovative thing into a retro thing. And you can\'t make another period of history happen again, it\'s just impossible. It seemed like it was exciting, and \'here we come, here\'s the revolution, the world\'s going to change.\' And then it just went into this horrible nostalgic morass of nothing. That\'s when I jumped ship. I think now it\'s so long ago that there is a chance now to do something new, because we have to transcend the echo now, we have to make another thing happen. We can\'t keep living on this echo that gets fainter and fainter and fainter and fainter. Because there\'s nothing to live on anymore.\"

Keleketla! is an expansive collaborative project, reaching outward from Johannesburg to London, Lagos, L.A. and West Papua, “Keleketla!” started as a musical meeting ground between Ninja Tune cofounders Coldcut and a cadre of South African musicians (introduced by the charity In Place Of War), including the raw, South African-accented jazz styles of Sibusile Xaba, and rapper Yugen Blakrok (Black Panther OST). From those initial sessions, the record grew to encompass a wider web of musical luminaries, including Afrobeat architects, the late pioneer Tony Allen and Dele Sosimi, legendary L.A. spoken word pioneers The Watts Prophets, and West Papuan activist Benny Wenda. The album collaborators are as follows: South Africa sessions: Yugen Blakrok, Nono Nkoane, Thabang Tabane, Tubatsi Moloi, Gally Ngoveni, Sibusile Xaba, Soundz of the South Collective, DJ Mabheko London sessions: Tony Allen, Shabaka Hutchings, Dele Sosimi, Ed ‘Tenderlonious’ Cawthorne, Tamar Osborn, Miles James, Joe Armon-Jones, Afla Sackey, Benny Wenda, The Lani Singers, Eska Mtungwazi, Jungle Drummer, DeeJay Random Additionally, The Watts Prophets (Los Angeles) and Antibalas (New York) have contributed to the album. The final product is a future-facing assemblage of influences, drawing connections between different points in a jazz-tipped, soulfully-minded spectrum; it builds outwards, from the solid musical foundations of those first sessions, featuring the likes of Thabang Tabane, esteemed percussionist and son of the legendary Phillip Tabane. On the one hand, there are gqom beats, interlaced with activist chants and and Tony Allen’s live Afrobeat drums; on the other, there are warm, lyrical meditations, aided by horns and keys. The name “Keleketla” means “response”, as in “call-and-response”, a title which speaks to the project’s aim: to build out a shared musical ground, traced across different recording sessions, continents apart. It all started with Johannesburg’s Keleketla! Library, an independent library and media arts initiative, stocked since its 2008 inception with donated items from the local community. Run by artists and musicians Rangoato Hlasane and Malose Malahlela, they met Ruth Daniels of the charity In Place of War (where a portion of the proceeds from the record will go to) who asked who they would choose for a musical collaboration with South African artists. Ra and Malose named Coldcut. The UK duo responded to the invitation to make a trip to South Africa for the recording sessions (supported by the British Council) and so the story started to grow. The duo had long nurtured an interest in South African jazz, and it was through Mushroom Hour Half Hour co-founder Andrew Curnow, whose label and collective have been part of the vanguard of a new generation of jazz-influenced acts from Jo’Burg and beyond, that they were connected to the players for the sessions. The main sessions took place at Soweto’s Trackside Studios, where they started a set of songs and settled down to rehearse and record them. Upon returning to the UK, Black and More sought out extra collaborators, setting up sessions with musicians who could expand and re-imagine the album’s horizons. In many cases, this meant building on the sessions in Soweto, such as in ‘Crystallise’, where Tamar Osborn’s sax parts were added to the lyrics that Yugen Blakrok laid down in Trackside. In other cases, they led to new tracks altogether, such as ‘Freedom Groove’, which came out of an off-the-cuff jam between Tony Allen and Matt Black; Allen’s drum part was taken to build a new track, overlaid with fat, battle-cry brass from Antibalas, and a powerful call to freedom from The Watts Prophets in L.A. Music and politics is a recurring theme on the record, most notably on ‘Future Toyi Toyi’, recorded in Khayelitsha, which features a recording Black and More made of hip-hop activists Soundz of the South, singing a revolutionary chant, referenced in the title, combined with – amongst other elements – a gqom track by Durban producer DJ Mabheko for the single version. Their creation was partly inspired by their experiences with the Keleketla! Library, who held a party during their stay. At the party, they saw the library’s co-founder Hlasane mix a recording of a student chant into a fiery, uptempo moment in his set, sending the crowd into a frenzy. It was a moment where they were reminded of how closely entwined politics and music can be. “It was almost a religious experience,” recalls Black, “to see the effect music could have in galvanising the audience like this.” Likewise, ‘Papua Merdeka’ centres around a political invocation. Led by Benny Wenda, it’s a call for freedom for the nation of West Papua from Indonesia, which Wenda fled in 2004 after being persecuted by the Indonesian military. He now leads a campaign from his home in Oxford, where the vocals for the track were recorded. Tony Allen, the rhythm behind Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat revolution, recorded the drums, along with Miles James, a guitarist who’s played with Michael Kiwanuka and Yussef Dayes, and who – as the son of an old family friend – featured in a Coldcut video when he was just a year old. “Keleketla!” is about finding musical connections. Starting with the tight community around the Keleketla! Library, this project has grown out of those closely forged bonds that can develop around music. Recalling the records he was introduced to and friends made while in South Africa, More says, “There’s music lovers everywhere and that’s what we thrive with.” “Keleketla!” is about embracing that call-and-response tradition, and seeing where it takes you.

A psychotherapist by day, Laura Fell’s upcoming debut album, ’Safe from Me’, is a search for answers from a woman always expected to have them to hand, and the self-punishing frustration that assumption brings. Fell’s dedication to this journey of self-discovery was unquestionable from the off, so much so that her peers questioned her sanity. Holding down three jobs to fund the record, Fell was determined that the songs would go far beyond their acoustic guitar genesis, assembling classically trained musicians to fully realise her vision. London-based, Fell only started playing music at 25 when the poetry she had been writing for almost a decade began to feel more like songs. This talent stretches throughout ‘Safe from Me’; Fell invites you to claw at the soil until you strike gold, and the meaning eventually becomes unearthed. ‘Safe from Me’ will be released on 20th November through Balloon Machine Records.

A few years before the release of *Songs of an Unknown Tongue*, Zara McFarlane travelled to her ancestral home of Jamaica. It was a research trip for a musical she was writing about an old Jamaican legend: The White Witch of Rose Hall—a twisted love story about a white woman who learns obeah, kills her lovers and enslaved peoples before eventually being killed by an enslaved labourer. This experience—travelling the country, conducting field research and interviews—sowed the seeds for this, her extraordinary fourth album. “It’s allegory of my personal journey exploring how the effects of colonialism resonates within my life today being Black and British,’’ Zara—who grew up in Dagenham, east London— tells Apple Music over the phone. Across the album’s 10 tracks we journey through semi-imagined histories spanning pre-colonialism, through enslavement and (the official) emancipation, to the present afterlife of slavery. It\'s not a linear timeline. McFarlane performs a kind of historical wake work here: Tending to unacknowledged histories, the living and the dead, the spirit and material worlds. “The story of the White Witch is set on the cusp of emancipation around 1834,” she says. “There were uprisings leading up to that moment, and I wanted to know what was happening musically at that time and to draw from those traditions. Most people think about ska as the beginning of Jamaican music, but there’s so much more, especially on the folk side.” Sonically, she encountered living folk traditions that largely came via enslaved peoples, and later indentured labourers from Africa and Asia. These rhythms—including Bruckins, Kumina, Ettu and many others—formed the basis of the album. “I wanted to make an album that was led by rhythm, percussion and vocals,” she says. She worked with celebrated producers and instrumentalists, Kwake Bass and Wu Lu to explore electronic expressions of these folk forms. It is an album of self-affirmation and witnessing, using music as a site for retrieving and pushing back on colonial histories. Here’s Zara’s track-by-track guide. **Everything is Connected** “This track was inspired by the cotton tree—it\'s vast and can grow ridiculously high. Mythically, it’s a place that holds the spirit of death through the creatures that live in it. Often these traditions are held by these trees in communion between sets of spirits. You hear those voices in that song, with the whispers I sing. These are the whispers of history and of those ancestors. This whole album takes you on a journey, from freedom and enslavement to emancipation. This part of the album is saying that everything is connected: it\'s exploring the idea of the cycle of life, the fact that life and death exist together in the same space.” **Black Treasure** “’Black Treasure’ is us: Black people. But on a wider level, it\'s speaking to everyone. To the essence of who you are. I primarily wanted it to be an anthem for Black people to feel empowered by. It’s also a reflection on the fact that the connotation of Black is always negative in the British language and in the media. I’m saying that Black is my history, my culture, my skin, my soul, my thoughts, my music, my words. All of it is treasure. Museums are filled with Black treasures—despite the fact that we’re called primitive and barbaric, so I\'m exploring ideas of voyage, treasure hunting and the British Empire. I’m making comment on the taking that’s been done. The way that I like to write is that I like to have two parallel things happening at the same time—so this track could be about not being taken seriously in a relationship, not being treated as treasure. From the angle I’m writing from, I’m saying that I’m Black treasure and I don’t need you to tell me that. It\'s also speaking specifically to Black women, as we are not always celebrated. We are treasure.” **My Story** “I had this vision of seeing myself walking down the street. I met a book that told me it had lost its pages, and asked me to help it find them, so I did. I realised it was my story. It represents Black history: the seeking that I have done and want to continue to do to understand what happened, and to better understand my identity. It\'s about recognising and acknowledging and owning the past: I don\'t think that happens here in this country. When I was researching in Jamaica I found that the histories were spoken about in a different way—people were much more vocal and open about it. It\'s their reality and they live it. It was interesting to meet those people and ask myself how I might do that in the same way. In the UK we don’t recognise Britain’s association with slavery. I think about it sheepishly: can I even talk about it? So, to me the song is about finding a way to own and acknowledge those histories and move forward with it. Musically, it\'s based on the revivalist tradition, which is related to Chrisitianity and has a religious context to it. I like the upbeat side to it: with church music you’re praising and uplifting, so it\'s got a driving rhythm to it.” **Broken Water** “I made a conscious decision that I wanted the melody to feel disjointed. I heard the tracks as disjointed sentences with a kind of call and response. The sentences are constructed across two voices: You can’t get the full message without the two voices together. I wanted an element of dissonance—that feeling and that mood. It\'s about that sense of displacement after travelling across the waters, and the loss that people went through. This track has a nyabinghi rhythm, there’s a religious connotation here, too. Christianity was a tool for enslavement—enslaved people weren’t allowed to practice their traditions and Christianity was taught to hold them down. The track is also fragmented lyrically—and that speaks to the idea of languages being broken down and lost.” **Saltwater** “This is one of the ballads on the album—at this point in the story, we’re in enslavement. I use the imagery of being abandoned and stranded on an island. I chose to talk about these feelings in the context of a relationship. Saltwater is reference to the ocean tears from the frustration of feeling trapped. With the instrumentation, melodically, the synth sound that you hear is directly related to the Bruckins party rhythm. I love what Kwake did with this version: it\'s so open and spacious, it feels like water. There is a sense of loss because you don’t have the driving force of the rhythm to hold you down, so there’s that sense being stuck out in the middle of nowhere and feeling alone, either by yourself or in the context of the relationship.” **Run of Your Life** “Here we’re escaping from slavery—it’s the thing that’s going to get you to freedom in order to have a life. It\'s a mantra to keep pushing forward through adversity in general. I grew up in a single parent household, and learnt from the women around me to keep pushing forwards. This track is played on a drum machine. Kwake and Wulu recorded the percussion live and created a MIDI imprint and then used purely electronic sounds. It\'s basically about an escape to freedom.” **State of Mind** “This is based on the Kumina rhythm and tradition. Kumina was developed as neo-traditional African practice among freed peoples, and the indentured labourers who came to Jamaica after emancipation. The rhythm has a hypnotic trance like effect, and can cause people to do superhuman feats, like walking up trees. I love the idea of the hypnotic trance, and the idea of the heartbeat. For me, this song is about the power of the rhythm and how it can have an effect on one’s state of mind. I wanted to use it as a channeling force for healing and guidance. For Kwake, it was also a homage to ‘90s dance as well, he liked the beat and the pulse of that sound—that whole scene was almost spiritual for some people! The drums in Kumina celebrations are said to be particularly important because of the control they have over the spirit. That was partly how I wanted to use this as well. I wanted to draw from that in a positive way.” **Native Nomad** “At this point, we’ve come out of ‘Run of Your Life\', where you’ve been escaping to freedom, into ‘State of Mind’ where you’re now on the other side and you’re asking where you go and what to do—you need to channel and get into a process of healing and guidance to be able to move forwards. ‘Native Nomad’ is about being in this new place and space and trying to fit in and understand what freedom is—you’re asking yourself how life then continues. Here, I’m literally writing about my experience of not fitting in as an English person, and not fitting in as a Jamaican person. It\'s about diaspora and how that feeling of displacement lingers across generations: This affinity with both worlds, and a yearning to go back to a homeland that was never our homeland. But it\'s ultimately about accepting who you are.” **Roots of Freedom** “This track takes us back to the idea of the tree again. This time it\'s about sowing seeds, and we are the seeds. We’ve accepted where we are now \[at this point in the story\]—we’re free. In being free we have the chance to improve the future for others. It\'s the idea of moving forward and the importance of a sense of unity for people: Black people, but also people throughout the world. It\'s about sowing the seeds for positive change. We own our future and we aren\'t limited. In leaning on history, we have the power to move better to move our forwards with strength.” **Future Echoes** “This track is about emancipation. We’re free. ‘Roots of Freedom’ is channeling freedom and getting the strength to move forward. ‘Future Echoes’ is also based on the Bruckins party tradition. It\'s about the future. What happens next. How we move forward. It\'s also about your relationship with yourself, and owing everything that has happened. Past hurts, future dreams, and directing the narrative of our own stories. It points to the fact that Black histories have always been told incorrectly: I’ve had to relearn my history. This track is about owning my story. I don’t need someone else to tell me my story: I’ve come through all of this. My history, my narrative, \[so now it\'s about\] my future for myself. It\'s a celebration of self-acceptance and rewriting the narrative. We realised that we’re not alone, and never have been.”

Brownswood are delighted to present Zara McFarlane’s, Songs of an Unknown Tongue a masterful work that underlines her continuous growth as an artist. Zara’s fourth studio album pushes the boundaries of jazz adjacent music via an exploration into the folk and spiritual traditions of her ancestral motherland, Jamaica. The album is a rumination on the piecing together of black heritage, where painful and proud histories are uncovered and connected to the present. Partnering with cult South London based producers Kwake Bass and Wu-lu, Zara has created a futuristic sound palate, electronically recreating the pulsing, hypnotic rhythms Kumina and Nyabinghi – and the music played at African rooted rituals like the emancipation celebration Bruckins Party, and the lively death rites of Dinki Minki and Gerreh. These richly patterned electronic rhythms are balanced throughout by McFarlane’s distinctive, clear vocal tones, and vivid song writing. Zara’s critically acclaimed third studio album ‘Arise’ met with universal critical praise, and was supported by an impressive live tour performing at festivals such as Love Supreme, Field Day and SXSW. Zara is the winner of multiple awards including a Mobo, 2 Jazz FM Vocalist of the Year Award (2018 & 2015), an Urban Music Award, and Session of the Year at Worldwide Awards. Drawing respect from a wide range of artists, Zara has collaborated with Gregory Porter, Shabaka Hutchings, Moses Boyd and Louie Vega. These new sonic explorations signal an exciting direction of travel for this innovative founding member of the UK’s vibrant homegrown jazz scene.

Ultraísta have announced their first new album since 2012's self-titled debut with the release of “Tin King.” The trio will release Sister on March 13, 2020. It’s a collection that defies easy categorization, and one that proves that Ultraísta — GRAMMY-winning producer/engineer/musician Nigel Godrich, best known for his two decades helming Radiohead’s groundbreaking studio output; celebrated drummer Joey Waronker, who’s toured and recorded with everyone from R.E.M. and Beck to Roger Waters and Elliott Smith; and singer Bettinson, an acclaimed solo artist whose work combines synth-driven electropop and dreamy vocal looping — is far more than just the sum of its remarkable parts.

On the eponymously titled final song of her debut album Land of No Junction, Irish songwriter Aoife Nessa Frances (pronounced Ee-fa) sings “Take me to the land of no junction/Before it fades away/Where the roads can never cross/But go their own way.” It is this search that lies at the heart of the album, recalling journeys towards an ever shifting centre – a centre that cannot hold – where maps are constantly being rewritten. The songs traverse and inhabit this indeterminate landscape: the beginnings of love, moments of loss, discovery, fragility and strength, all intermingle and interact. Land of No Junction is shot through with a sense of mystery – an ambiguity and disorientation that illuminates with smokey luminescence. Navigated by the richness of Aoife’s voice, along with the layers gently built through her collaborators’ instruments (strings, drums, guitars, keys, percussion) gives a feeling of filling up space into every corner and crack. A remarkable coherent sonic world: buoyant and aqueous, with dark undercurrents. Where nostalgia and newness ebb and flow in equal measure.

**COPIES STILL AVAILABLE THROUGH THE FOLLOWING. BANDCAMP NOW SOLD OUT** ROUGH TRADE www.roughtrade.com/gb/total-wkts/running-tracks RESIDENT RECORDS www.resident-music.com/productdetails&path=34000&product_id=71383 NORMAN RECORDS www.normanrecords.com/records/182914-total-wkts-running-tracks DRIFT RECORD SHOP driftrecords.com/products/total-wkts-running-tracks?_pos=1&_sid=f467eccab&_ss=r RECORDSTORE.CO.UK www.recordstore.co.uk/recordstore/recordstore/Running-Tracks-Signed-Exclusive-Frosted-Glass-Vinyl/6N8I0000000 Made in the gap between March and May 2020, John Newton (vocalist/drummer of London based two-piece JOHN) presents ’Running Tracks' under the guise ‘Total Wkts’. An album embracing the limitations and possibilities of a spell away from his usual surroundings in South London. Having moved back into his childhood town in the rural South West of England, the tracks are treated as playful collages, incorporating various sampled sounds in each composition: bird noises become stuck in the programming of drum tracks, inhalation between spoken lines is left to remain. The incidental is encouraged throughout the entire project, opener ‘HP Envy’ taking its name from the household printer that sets its rhythm, offering overlaid lyrics that repurpose the words of a spam email received during its production. 'Animal Dream' and 'Miniature Police' follow the same vein, the songs built from the verbal retellings of dreams. The name 'Total Wkts' becomes an emblem of his approach. The two words taken from a sign seen on his daily run through the rural landscape, with most of the tracks also written and arranged whilst on this repetitive circuit. Following online correspondence regarding an unrelated and unrealised project in March 2020, 'HP Envy' was sent to Graeme Sinclair of label Outré Disque. He premiered the track whilst guesting on James Endeacott's Soho Radio show on the 19th May 2020. Newton felt that it was important for the music to be released in the same spirit of its making, choosing to release the full collection of songs shortly after on June 11th (also his birthday).

A Powys trio whose free-spirited invention and exuberant intensity flows through experimental pop: hypnotic, exhilarating and defiantly unique. The Welsh band Islet return with the release of their long-awaited new album. 'Eyelet' was recorded at home tucked away in the hills of rural Mid Wales. It took form the months following the birth of band members Emma and Mark Daman Thomas’ second child and the death of fellow band member Alex Williams’ mother. Alex came to live with Emma and Mark, and the band enlisted Rob Jones (Pictish Trail, Charles Watson) to produce. Winner of 2020 Neutron Prize www.godisinthetvzine.co.uk/2020/09/30/news-islet-win-the-neutron-prize-2020/ Shortlisted for Welsh Music Prize 2020

They began by just playing the hits. In 2017, nearly eight years after Doves had last picked up their instruments together, drummer Andy Williams and his twin brother, guitarist Jez, gave bassist/singer Jimi Goodwin a call. Come over to Andy’s studio, they said, and let’s see if we can remember how to play “Black and White Town” and “There Goes the Fear”—just for fun. “It came back really quickly,” Andy tells Apple Music. “We were all laughing and having fun. As a drummer, hearing that bass—*his* bass—instantly felt very familiar, in a good sense. Pretty soon, there was a real enthusiasm and hunger from us to work together.” When they went on hiatus after 2009’s excellent *Kingdom of Rust* album, Doves were fatigued. They’d been together for a quarter of a century, serving up four albums as one of Britain’s best and more adventurous indie-rock trios—plus one before that as house specialists Sub Sub. They were never meant to disappear for a decade, but when you’ve got families and side projects (the Williams brothers as Black Rivers, Goodwin with his 2014 solo album *Odludek*), life gets in the way. “I don’t want to sound boastful, but I think there’s a chemistry between us three that you don’t run into every day,” Andy says. “That time away from each other has helped us appreciate that.” Fizzing with that chemistry, *The Universal Want* sounds like a Doves album precisely because it doesn’t sound like any other Doves album. The exquisitely measured mix of euphoria and sorrow is familiar, but by experimenting with Afrobeat, dub, and keyboards foraged from behind the Iron Curtain, the trio continues to expand their horizons on every song. “We didn’t attempt to resurrect another ‘The Cedar Room’ or ‘There Goes the Fear,’ because it’s a recipe for disaster when you chase your own tail,” says Andy. “It’s really important for us three to be excited and feel like we’re moving forward.” Let him guide you through that evolution, track by track. **Carousels** “Originally, it started life as Black Rivers and we couldn’t get it to work. We put it down for a while, then Jez had a look at it again. He’d bought a Tony Allen breakbeat album and just sampled some breaks. It just clicked—the song came alive. We felt it was a bit of a progression for us, so it felt like a good song to introduce ourselves back to people again. Lyrically, it’s a bit of a nostalgia thing. We all used to go out to funfairs as kids up here in the North West, and every summer we’d go to a place called Harlech in North Wales and there’d be a funfair near there. It’s a nostalgic look back at that era when you used to hear music for the first time, loud, on loudspeakers, and that excitement at the fair—trying to recapture that feeling. The music’s trying to push it forward, but lyrically, it’s looking back, so there’s that juxtaposition.” **I Will Not Hide** “Really fun memories of making this. Jimi loves his sampling, so when he played it to us, it was like, ‘Wow! What’s going on there?’ I couldn’t really fathom out the lyrics. I mean, I put a couple of lines in there myself, but I still don’t fully understand what it’s about. I don’t think Jimi does. But we quite like that place sometimes, where it’s almost a train of thought. Jimi’s demo stopped, I think, at chorus two. We just looked at the chords, me and Jez, and tacked the guitar section onto the end. That’s the nice thing about Doves—when people present ideas to the band, it goes through the filter of all three of us and it can change. That’s when it’s working well between us three, when someone has an initial idea and then the other two run with it.” **Broken Eyes** “Early doors, we found an old hard drive with loads of material on, stuff we hadn’t actually ever managed to finish, and this was one \[from the *Kingdom of Rust* sessions\]. We were like, ‘Oh, that’s got real heart and soul. Let’s tackle that again.’ Last time, we were maybe overcomplicating it, so we stripped it away and kept it simple. It always had a different lyric, right up until the 11th hour, actually. It had a very different vibe. Jimi sounds brilliant on this. When he did the vocal, it was hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck stuff. That’s when you know you’re on the right path. You just hit a brick wall sometimes with songs. I read a Leonard Cohen book and I think he was talking about ‘Tower of Song,’ that it took him 20 years to finish. Started it, put it down, picked it up again, kept going back to it. If a song’s got strength in it, it will keep knocking on your door. We’ve got other songs which I’m hoping we can look at again at some point. There’s a couple of things where I’ve gone, ‘Do you remember this one?’ And it was, ‘Oh no, I can’t.’ Because we’d absolutely hammered it at the time and not made it work, and no one’s ready to go back to that place.” **For Tomorrow** “Again, we had those chords for the chorus kicking round for a while but we never really had a song. The high string in the verses, we were like, ‘Oh god, look, it’s got that kind of Isaac Hayes classic soul thing we were going for.’ I know it didn’t necessarily end up that way, but that’s what we were going for in our heads. We did it live in the room, and I remember going back in the control room and going, ‘Ah, it’s just coming together.’ I’ve got really fond memories, a couple of moments of like, ‘Yeah.’ It’s a really fun one to play on the drums.” **Cathedrals of the Mind** “Initially it was from a Black Rivers session—another song that, down the line, Jimi heard and really loved and worked on with us. We were booked to go to Anglesey, me and Jez, in 2016. We were due to set off at nine in the morning, but at six o’clock, my wife wakes me up and says, ‘Bowie’s passed.’ I couldn’t take it in—like the whole world, I guess. I remember driving to Anglesey with 6 Music on, they cleared their schedule and were just talking about Bowie. We got to Anglesey and it was like, ‘Fucking hell.’ I’m not saying we wrote this song for him, but I think it was an unconscious thing. Jez had some chords and I tried a couple of different grooves. It didn’t work, and I tried that sort of dub groove, and that was the start of the song. The lyrics, as well—‘In the back room/In the ballroom/I hear them calling your name…/Everywhere I see those eyes.’ I think we were referencing the passing of such a musical icon. He was such a towering figure, cultural figure. Him passing felt like your own mortality, essentially.” **Prisoners** “It’s the love affair with northern soul that we’ve had for years. Very English lyrics. The Jam was one reference when we were doing the lyrics, ‘Town Called Malice.’ It was written way before the situation we’re in \[2020’s lockdown\], but it’s got some sort of resonance. We’ve all been stuck in our houses and we’re only just starting to come out. But it’s also got a sense of hope. The chorus is ‘We’re just prisoners of these times/Although it won’t be for long.’ So there is a sense of hope with that. We let everybody know our struggles, I guess, but it’s good to have a sense of hope in there.” **Cycle of Hurt** “Jez came with that \[robotic voice\] sample and those chords. They’re probably the most direct lyrics \[on the album\]. It’s referencing a relationship really, and just trying to get out of a cycle of hurt—a cycle of thought that you’re trapped in. They’re quite collaborative, these lyrics. A lot of them that are \[about being\] just locked in a cycle of your own thought, really, and trying to break free from that. There’s definite references to trying to keep your own mental health on track. Looking back on it, that’s a subject we’ve definitely returned to on this record. We felt this \[track\] was really good for the album because there weren’t really deep strings on the rest of the record, and it just brings a new sound for your ears to keep your interest up.” **Mother Silverlake** “The end result doesn’t bear any relation to an Afrobeat song, but that’s what we had in our heads—something that felt new to us, we’ve never really attempted that. Jez and Jimi combined \[on the\] vocal—that was really nice to hear those two singing together in the studio, the mix of their two voices. Martin Rebelski’s pianos really uplift the chorus. It’s a feel-good track, but the lyrics are slightly melancholic, almost referencing our mum, who’s still around, thank god. We always try and make music as uplifting as possible, or as joyous as possible. It might be offset with more melancholic lyrics, but overall we always want it to be an uplifting experience.” **Universal Want** “I started it in my studio as a ballad. I never intended it to be like a house workout at the end. I was thinking of just a two-and-a-half-minute song about the universal want—this question of always chasing something, be it consumerism or some aspect of your life where you think you’re going to be happy. But Jez took it away and he obviously saw something else for the end section and thought of welding this house section onto the end. I couldn’t believe it when I heard it, it was just so unpredictable, and I hope that unpredictability carries through to the listener. I guess it’s kind of a reference to our past, our Sub Sub days—a cheeky doff of the cap to that era. It was a very formative era for all of us.” **Forest House** “Again, this had been knocking around for a while and we were never able to master it, didn’t ever find the key to unlock it. It just felt like it was a really intimate way to finish the record—a small way to wind the album down. A simple song, but with Jez’s Russian keyboard in there—this old Russian ’60s monster of an analog keyboard. It’s almost got a dystopian sound. Once that got brought into the song, it was like, ‘Yeah.’”