Pitchfork's Best Rock Albums of 2019

From Big Thief’s twin masterworks to Brittany Howard’s bold solo debut, these were the guitar records we loved most this year.

Published: December 11, 2019 14:00

Source

Big Thief had only just finished work on their 3rd album, U.F.O.F. – “the celestial twin” – days before in a cabin studio in the woods of Washington State. Now it was time to birth U.F.O.F.’s sister album – “the earth twin” – Two Hands. 30 miles west of El Paso, surrounded by 3,000 acres of pecan orchards and only a stone’s throw from the Mexican border, Big Thief (a.k.a. Adrianne Lenker, Buck Meek, Max Oleartchik, and James Krivchenia) set up their instruments as close together as possible to capture their most important collection of songs yet. Where U.F.O.F.layered mysterious sounds and effects for levitation, Two Hands grounds itself on dried-out, cracked desert dirt. In sharp contrast to the wet environment of the U.F.O.F. session, the southwestern Sonic Ranch studio was chosen for its vast desert location. The 105-degree weather boiled away any clinging memories of the green trees and wet air of the previous session. Two Hands had to be completely different — an album about the Earth and the bones beneath it. The songs were recorded live with almost no overdubs. All but two songs feature entirely live vocal takes, leaving Adrianne’s voice suspended above the mix in dry air, raw and vulnerable as ever. “Two Hands has the songs that I’m the most proud of; I can imagine myself singing them when I’m old,” says Adrianne. “Musically and lyrically, you can’t break it down much further than this. It’s already bare-bones.” Lyrically this can be felt in the poetic blur of the internal and external. These are political songs without political language. They explore the collective wounds of our Earth. Abstractions of the personal hint at war, environmental destruction, and the traumas that fuel it. Across the album, there are genuine attempts to point the listener towards the very real dangers that face our planet. When Adrianne sings “Please wake up,” she’s talking directly to the audience. Engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who were both behind U.F.O.F., capture the live energy as instinctually and honestly as possible. Sarlo teamed up with James Krivchenia to mix the album, where they sought to emphasize raw power and direct energy inherent in the takes. The journey of a song from the stage to the record is often a difficult one. Big Thief’s advantage is their bond and loving centre as a chosen family. They spend almost 100% of their lives together working towards a sound that they all agree upon. A band with this level of togetherness is increasingly uncommon. If you ask drummer James Krivchenia, bassist Max Oleartchik or guitarist Buck Meek how they write their parts, they will describe — passionately — the experience of hearing Adrianne present a new song, listening intently for hints of parts that already exist in the ether and the undertones to draw out with their respective instruments. With raw power and intimacy, Two Hands folds itself gracefully into Big Thief’s impressive discography. This body of work grows deeper and more inspiring with each new album.

Big Thief has been known to tackle intensely personal themes: family histories, deaths, isolation, fear. Here, on their expansive third album, the New York indie rock band shifts its gaze outward and into the unknown. \"Just like a bad dream/You\'ll disappear,” frontwoman Adrianne Lenker coos on the title track. \"And I imagine you/Taking me outta here.” Through gentle strums and hushed, tumbling melodies, the band wonders: Who\'s out there? Are they as strange as we are? What’s real? The second F in the album’s title stands for “friend”—an optimistic embrace of all things unfamiliar or alien. Their songs—comforting, eerie, folksy, magnificent—do the same.

U.F.O.F., F standing for ‘Friend’, is the name of the highly anticipated third record by Big Thief, set to be released on 3rd May 2019 via 4AD. U.F.O.F. was recorded in rural western Washington at Bear Creek Studios. In a large cabin-like room, the band set up their gear to track live with engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who was also behind their previous albums. Having already lived these songs on tour, they were relaxed and ready to experiment. The raw material came quickly. Some songs were written only hours before recording and stretched out instantly, first take, vocals and all. “Making friends with the unknown… All my songs are about this,” says Lenker; “If the nature of life is change and impermanence, I’d rather be uncomfortably awake in that truth than lost in denial.”

Released in September of 2018, Mother of My Children was the debut album from Black Belt Eagle Scout, the recording project of Katherine Paul. Heralded as a favorite new musician of 2018 by the likes of NPR Music, Stereogum, and Paste, the album was also named as a “Best Rock Album of 2018” by Pitchfork, and garnered further end-of-year praise from FADER, Under The Radar and more. Arriving just a year after that debut record, At the Party With My Brown Friends is a brand new full-length recording from Black Belt Eagle Scout. Where that first record was a snapshot of loss and landscape and of KP’s standing as a radical indigenous queer feminist, this new chapter finds its power in love, desire and friendship. At the Party With My Brown Friends is a profound and understated forward step. The squalling guitar anthems that shaped its predecessor are replaced by delicate vocals and soft keys, sentiments spoken and unspoken, presenting something shadowy and unsettling; a stirring of the waters. The end result presents a captivating about-face that redefines KP’s beautifully singular artistic vision.

Over the decade-plus since he arrived seemingly fully formed as the platonic ideal of indie DIY made good, Justin Vernon has pushed back against the notion that he and Bon Iver are synonymous. He is quick to deflect credit to core longtime collaborators like Chris Messina and Brad Cook, while April Base, the studio and headquarters he built just outside his native Eau Claire, Wisconsin, has become a cultural hub playing host to a variety of experimental projects. The fourth Bon Iver full-length album shines a brighter light on Bon Iver as a unit with many moving parts: Renovations to April Base sent operations to Sonic Ranch in Tornillo, Texas, for much of the production, but the spirit of improvisation and tinkering and revolving-door personnel that marked 2016’s out-there *22, A Million* remained intact. “This record in particular felt like a very outward record; Justin felt outward to me,” says Cook, who grew up with Vernon and has played with him through much of his career. “He felt like he was in a new place, and he was reaching out for new input in a different way. We\'re just more in the foreground inevitably because the process became just a little bit more transparent.” Vernon, Cook, and Messina talk through that process on each of *i,i*\'s 13 tracks. **“Yi”** Justin Vernon: “That was a phone recording of me and my friend Trevor screwing around in a barn, turning a radio on and off. We chopped it up for about five years, just a hundred times. There’s something in that ‘Are you recording? Are you recording?’ that felt like the spirit that flows into the next song.” **“iMi”** Brad Cook: “It was like an old friend that you didn\'t know what to do with for a long time. When we got to Texas, a lot of different people took a crack at trying to make something out of that song. And then Andrew Sarlo, who works with Big Thief and is just a badass young producer, he took the whack that broke through the wall. Once the band got their hands on it, Justin added some of the acoustic stuff to it, and it just totally blew it wide open.” **“We”** Vernon: “I was working on this idea one morning with this engineer, Josh Berg, who happened to be out with us. And this guy Bobby Raps from Minneapolis was also at my studio just kind of hanging around, and he brought this dude named Wheezy who does some Young Thug beats, some Future beats. So I had this little baritone-guitar bass loop thing, and Wheezy put his beat on there. All these songs had a life, or had a birth, before Texas, but Texas was like graduation for every single one. That\'s why we went for so long and allowed for so much perspective to sink into all the tunes. It\'s a fucking banger; I love that one.” **“Holyfields,”** Vernon: “The whole song is an improvised moment with barely any editing, and we just improv\'d moves. I sang some scratch vocals that day when we made it up, and they were weirdly close to what ended up being on the album. We didn\'t really chop away at that one—it kind of just was born with all its hair and everything.” **“Hey, Ma”** Vernon: “It just felt like a good strong song; we knew people would get it in their head. A couple of these tunes, and some of the tunes from the last album, I sort of peck around the studio with BJ Burton from time to time, and 90 percent of the stuff we make is death techno or something. So, there\'s another one that sort of just hung around with a stake in the ground, so to speak. And then our team—the three of us and the rest of everyone—just kept etching away at it, and it ended up becoming the song that felt emblematic of the record.” **\"U (Man Like)\"** Cook: “We had Bruce \[Hornsby\] come out to Justin\'s studio for a session for his *Absolute Zero* record. Bruce was playing a bunch of musical ideas that he had just sort of done at his house, and that piano figure in that song—I feel like we were tracking 15 seconds later. It was like, \'Wait, can we listen to this again?\'” Vernon: “I\'m not so good at coming up with full songs on the spot, but I can kind of map them out with my voice, or inflection. Then it takes a long time to chip away at them. Messina might have an idea for what that line should be, or Brad, or me. The melody that I sang that first day probably sounds remarkably like the melody that\'s on the album.” **“Naeem”** Vernon: “We did a collaboration with a dance group called TU Dance, and that was one of the songs. So we\'ve been performing \'Naeem\' as a part of this thing for a while. It\'s in a different state, but it\'s the finale of this big collaboration. And it just seemed very anthemic, and a very important part of whatever this record was going to be. It feels really nice to have a little bit more straightforward—not always bombastic, not always sonically trying to flip your lid or something.” **“Jelmore”** Vernon: “Basically an improvisation with me and this guy Buddy Ross. Again I probably didn\'t sing any final lyrics, but it\'s based on an improvisation, much like the song \'\_\_\_\_45\_\_\_\_\_\' from \[*22, A Million*\]. And when we were down outside El Paso, me and Chris were over on one part of this studio and Brad was with the band in a big studio across the property, and they sort of took \'Jelmore\' upon themselves and filled it in with all the lovely live-ness that\'s there. As the record goes on, it feels like there\'s a lot of these things that are sort of bare but have a lot of live energy to them.” **“Faith”** Vernon: “A basement improv that sat around for many years; maybe could have been on the last album, was for a while. I don\'t know, man—it\'s a song about having faith.” **“Marion”** Chris Messina: “I think that\'s one that Justin\'s been noodling around with for a while; for a few years, he would pick up that guitar and you would just kind of hear that riff. And we didn\'t really know what was going to happen to it. It\'s another one that exists in the TU Dance show. But what\'s cool about the version that\'s on the record is we did that as a live take with a six-piece ensemble that Rob Moose wrote for and conducted, and it was saxophone, trombone, trumpet, French horn, harmonica, and I think that\'s it that we did live. And then Justin was singing live and playing guitar live.” **“Salem”** Vernon: “OP-1 loop, weird Indigo Girls/Rickie Lee Jones vibes. I got really into acid and the Grateful Dead this year, so there\'s definitely some early psych vibes in there. The record really is supposed to be thought of as the fall record for this band, if you think of the other ones as seasons. Salem and burning leaves—these longings and these deaths, it\'s very much in there in that song, so it\'s a really autumn-y song.” **“Sh’Diah”** Vernon: “It stands for Shittiest Day in American History—the day after Trump got elected. It\'s another that sort of hung around as an improvised idea, and we finally got to figure out where we\'re going to land Mike Lewis, our favorite instrumentalist alive today in music. He gets to play over it, and the band got to do all this crazy layering over it. It\'s just one of my favorite moods on the album.” **“RABi”** Messina: “Justin\'s singing a cool thing on it, the guitar vibe is comforting and persistent, but we just weren\'t really sure where it needed to go. And then Brad and the rest of the dudes got their hands on it and it came back as just a dream sequence; it was so sick. We all kind of heard it and it was like, whoa, how can this not close out the record? This is definitely \'see you later.\'” Vernon: “Just some ‘life feels good now, don\'t it?\' There\'s a lot to be sad about, there\'s a lot to be confused about, there\'s a lot to be thankful for. And leaning on gratitude and appreciation of the people around you that make you who you are, make you feel safe, and provide that shelter so you can be who you want to be, there\'s still that impetus in life. We need that. It\'s a nice way to close the record, we all thought.”

JAIME I wrote this record as a process of healing. Every song, I confront something within me or beyond me. Things that are hard or impossible to change, words and music to describe what I’m not good at conveying to those I love, or a name that hurts to be said: Jaime. I dedicated the title of this record to my sister who passed away as a teenager. She was a musician too. I did this so her name would no longer bring me memories of sadness and as a way to thank her for passing on to me everything she loved: music, art, creativity. But, the record is not about her. It’s about me. It’s not as veiled as work I have done before. I’m pretty candid about myself and who I am and what I believe. Which, is why I needed to do it on my own. I wrote and arranged a lot of these songs on my laptop using Logic. Shawn Everett helped me make them worthy of listening to and players like Nate Smith, Robert Glasper, Zac Cockrell, Lloyd Buchanan, Lavinia Meijer, Paul Horton, Rob Moose and Larry Goldings provided the musicianship that was needed to share them with you. Some songs on this record are years old that were just sitting on my laptop, forgotten, waiting to come to life. Some of them I wrote in a tiny green house in Topanga, CA during a heatwave. I was inspired by traveling across the United States. I saw many beautiful things and many heartbreaking things: poverty, loneliness, discouraged people, empty and poor towns. And of course the great swathes of natural, untouched lands. Huge pink mountains, seemingly endless lakes, soaring redwoods and yellow plains that stretch for thousands of acres. There were these long moments of silence in the car when I could sit and reflect. I wondered what it was I wanted for myself next. I suppose all I want is to help others feel a bit better about being. All I can offer are my own stories in hopes of not only being seen and understood, but also to learn to love my own self as if it were an act of resistance. Resisting that annoying voice that exists in all of our heads that says we aren’t good enough, talented enough, beautiful enough, thin enough, rich enough or successful enough. The voice that amplifies when we turn on our TVs or scroll on our phones. It’s empowering to me to see someone be unapologetically themselves when they don’t fit within those images. That’s what I want for myself next and that’s why I share with you, “Jaime”. Brittany Howard

It was on a mountainside in Cumbria that the first whispers of Cate Le Bon’s fifth studio album poked their buds above the earth. “There’s a strange romanticism to going a little bit crazy and playing the piano to yourself and singing into the night,” she says, recounting the year living solitarily in the Lake District which gave way to Reward. By day, ever the polymath, Le Bon painstakingly learnt to make solid wood tables, stools and chairs from scratch; by night she looked to a second-hand Meers — the first piano she had ever owned —for company, “windows closed to absolutely everyone”, and accidentally poured her heart out. The result is an album every bit as stylistically varied, surrealistically-inclined and tactile as those in the enduring outsider’s back catalogue, but one that is also intensely introspective and profound; her most personal to date. This sense of privacy maintained throughout is helped by the various landscapes within which Reward took shape: Stinson Beach, LA, and Brooklyn via Cardiff and The Lakes. Recording at Panoramic House [Stinson Beach, CA], a residential studio on a mountain overlooking the ocean, afforded Le Bon the ability to preserve the remoteness she had captured during the writing of Reward in Staveley, Lake District. Over this extended period a cast of trusted and loved musicians joined Le Bon, Khouja and fellow co-producer Josiah Steinbrick — Stella Mozgawa (of Warpaint) on drums and percussion; Stephen Black (aka Sweet Baboo) on bass and saxophone and longtime collaborators Huw Evans (aka H.Hawkline) and Josh Klinghoffer on guitars — and were added to the album, “one by one, one on one”. The fact that these collaborators have appeared variously on Le Bon’s previous outputs no doubt goes some way to aid the preservation of a signature sound despite a relatively drastic change in approach. Be it on her more minimalist, acoustic-leaning 2009 debut album Me Oh My or critically acclaimed, liquid-riffed 2013 LP Mug Museum as well as 2016s Crab Day, Cate Le Bon’s solo work — and indeed also her production work, such as that carried out on recent Deerhunter album Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? (4AD, January 2019) — has always resisted pigeonholing, walking the tightrope between krautrock aloofness and heartbreaking tenderness; deadpan served with a twinkle in the eye, a flick of the fringe and a lick of the Telecaster. The multifaceted nature of Le Bon’s art — its ability to take on multiple meanings and hold motivations which are not immediately obvious — is evident right down to the album’s very name. “People hear the word ‘reward’ and they think that it’s a positive word” says Le Bon, “and to me it’s quite a sinister word in that it depends on the relationship between the giver and the receiver. I feel like it’s really indicative of the times we’re living in where words are used as slogans, and everything is slowly losing its meaning.” The record, then, signals a scrambling to hold onto meaning; it is a warning against lazy comparisons and face values. It is a sentiment nicely summed up by the furniture-making musician as she advises: “Always keep your hand behind the chisel.”

Covert contracts rule our world: manipulative relationships, encoded social norms, opaque technologies. “With a covert contract, the trick is that the agreement is only known by the person who makes it,” says Ali Carter, singer and bassist of Philly post-punk trio Control Top. “The other person is oblivious. Consent is impossible. A void of communication opens up a world of misunderstanding.” In an era of such impossibilities, Control Top—Carter with guitarist Al Creedon and drummer Alex Lichtenauer—rip open space for catharsis. Their explosive songs are a synthesis of varied interests and backgrounds: Carter’s innate sense of new wave melodies, Creedon’s sirening noise guitars, Lichtenauer’s feverish hardcore drumming. On their debut full-length Covert Contracts, out now via Get Better Records, the songwriting is fully a collaboration of Carter and Creedon. Carter’s voice thumps and screams and deadpans while her driving, hooky basslines play out like guitar leads. Creedon, also the band’s engineer and producer, balances composition and chaos, equally inspired by pop and no-wave. With her lyrics, Carter responds to feeling trapped and overwhelmed in a capitalist patriarchy, offering indictments of wrongdoing and abuse of power, odes to empathy and ego death, as well as declarations of self-determination. These songs hit even harder when you consider how close this band came to not existing at all. Despite being involved in underground music communities for years, Carter didn’t start Control Top (her first band) until age 25. Disillusioned by punk, Creedon had all but abandoned guitar. But Control Top felt exciting, a chance to experiment: to rethink the relationship between guitar and bass and use samplers to add new dimensions. Meanwhile, Lichtenauer had quit playing drums after an abusive situation in a previous band that had ruined playing music for them, and joining Control Top was an opportunity for rebirth. At once anthemic and chilling, Covert Contracts puts words to today’s unspoken anxieties. Brimming with post-punk poetry for 2019, it’s the sound of agency being reclaimed.

“We all get lost, but we all come back,” Crumb’s Lila Ramani sings on the title track to *Jinx*, providing a succinct mission statement for one of 2019’s most bewitching indie-rock debuts. The New York-via-Boston quartet douse their songs in luxuriant *Dark Side of the Moon Safari* atmosphere, but a taut, in-the-pocket rhythm section and Ramani’s velveteen voice serve as beacons that guide you through the haze. *Jinx* conjures the sensation of drifting through a dream that’s equally nostalgic and unnerving, with Ramani’s dazed delivery falling somewhere between resigned and restless. On “Ghostride,” she blithely details the ennui-inducing minutiae of a long road trip as a metaphor for being trapped in a dysfunctional relationship, sheepishly admitting, “The radio reminds me I’m alive.” But Crumb isn\'t afraid to disrupt their hypnotic reveries with abrupt shifts in course—\"Part III” begins as a blissfully narcotic Stereolab sway, before coming to a dead stop and free-falling into a psychedelic jazz abyss. “It’s just a feeling,” Ramani repeats just as she’s about to disappear into the void, but *Jinx*’s ambiguous beauty lies in the fact that you’re never exactly sure how you should be feeling.

The Atlanta band’s eighth full-length finds iconoclastic frontman Bradford Cox and co. shrinking their typically ambient-focused sound, with relatively compact guitar-pop gems alongside haunting, weightless-sounding instrumentals. Featuring contributions from Welsh singer-songwriter Cate Le Bon and Tim Presley of garage-popsters White Fence, *Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?* diverges from the deeply personal themes of previous Deerhunter albums, zeroing in on topics ranging from James Dean (“Plains”) to the tragic murder of British politician Jo Cox (“No One’s Sleeping”)—but the spectral vocals and penchant for left-field sounds are well accounted for, as the album represents the latest strange chapter in one of modern indie rock’s most consistently surprising acts.

Rebirth takes place when everything falls apart. DIIV—Zachary Cole Smith [lead vocals, guitar], Andrew Bailey [guitar], Colin Caulfield [vocals, bass], and Ben Newman [drums]—craft the soundtrack to personal resurrection under the heavy weight of metallic catharsis upheld by robust guitars and vocal tension that almost snaps, but never quite… The same could be said of the journey these four musicians underwent to get to their third full-length album, Deceiver. Out of lies, fractured friendships, and broken promises, clarity would be found. “I’ve known everyone in the band for ten years plus separately and together as DIIV for at least the past five years,” says Cole. “On Deceiver, I’m talking about working for the relationships in my life, repairing them, and accepting responsibility for the places I’ve failed them. I had to re-approach the band. It wasn’t restarting from a clean slate, but it was a new beginning. It took time—as it did with everybody else in my life—but we all grew together and learned how to communicate and collaborate.” A whirlwind brought DIIV there. Amidst turmoil, the group delivered the critical and fan favorite Is the Is Are in 2016 following 2012’s Oshin. Praise came from The Guardian, Spin, and more. NME ranked it in the Top 10 among the “Albums of the Year.” Pitchfork’s audience voted Is the Is Are one of the “Top 50 Albums of 2016” as the outlet dubbed it, “gorgeous.” In the aftermath of Cole’s personal struggles, he “finally accepted what it means to go through treatment and committed,” emerging with a renewed focus and perspective. Getting back together with the band in Los Angeles would result in a series of firsts. This would be the first time DIIV conceived a record as a band with Colin bringing in demos, writing alongside Cole, and the entire band arranging every tune. “Cole and I approached writing vocal melodies the same way the band approached the instrumentals,” says Colin. “We threw ideas at the wall for months on end, slowly making sense of everything. It was a constant conversation about the parts we liked best versus which of them served the album best.” Another first, DIIV lived with the songs on the road. During a 2018 tour with Deafheaven, they performed eight untitled brand-new compositions as the bulk of the set. The tunes also progressed as the players did. “We went from playing these songs in the rehearsal space to performing them live at shows, figuring them out in real-time in front of hundreds of people, and approaching them from a broader range of reference points,” he goes on. “We’d never done that before. We got to internalize how everything worked on stage. We did all of the trimming before we went to the studio. It was an exercise in simplifying what makes a song. We really learned how to listen, write, and work as a band.” The vibe got heavier under influences ranging from Unwound and Elliot Smith to True Widow and Neurosis. They also enlisted producer Sonny Diperri [My Bloody Valentine, Nine Inch Nails, Protomartyr]. his presence dramatically expanded the sonic palette, making it richer and fuller than ever before. It marks a major step forward for DIIV. “He brought a lot of common sense and discipline to our process,” adds Cole. “We’d been touring these songs and playing them for a while, so he was able to encourage us to make decisions and own them.” The first single “Skin Game” charges forward with frenetic drums, layered vocals and clean, driven guitars that ricochet off each other. “I’d say it’s an imaginary dialogue between two characters, which could either be myself or people I know,” he says. “I spent six months in several different rehab facilities at the beginning of 2017. I was living with other addicts. Being a recovering addict myself, there are a lot of questions like, ‘Who are we? What is this disease?’ Our last record was about recovery in general, but I truthfully didn’t buy in. I decided to live in my disease instead. ‘Skin Game’ looks at where the pain comes from. I’m looking at the personal, physical, emotional, and broader political experiences feeding into the cycle of addiction for millions of us.” A trudging groove and wailing guitar punctuate a lulling apology on the magnetically melancholic “Taker.” According to Cole, it’s “about taking responsibility for your lies, their consequences, and the entire experience.” Meanwhile, the ominous bass line and crawling beat of “Blankenship” devolve into schizophrenic string bends as the vitriolic lyrics. Offering a dynamic denouement, the seven-minute “Acheron” flows through a hulking beat guided under gusts of lyrical fretwork and a distorted heavy apotheosis. Even after the final strains of distortion ring out on Deceiver, these four musicians will continue to evolve. “We’re still going,” Cole leaves off. “Hopefully we’ll be doing this for a long time.” Ultimately, DIIV’s rebirth is a hard-earned and well-deserved new beginning.

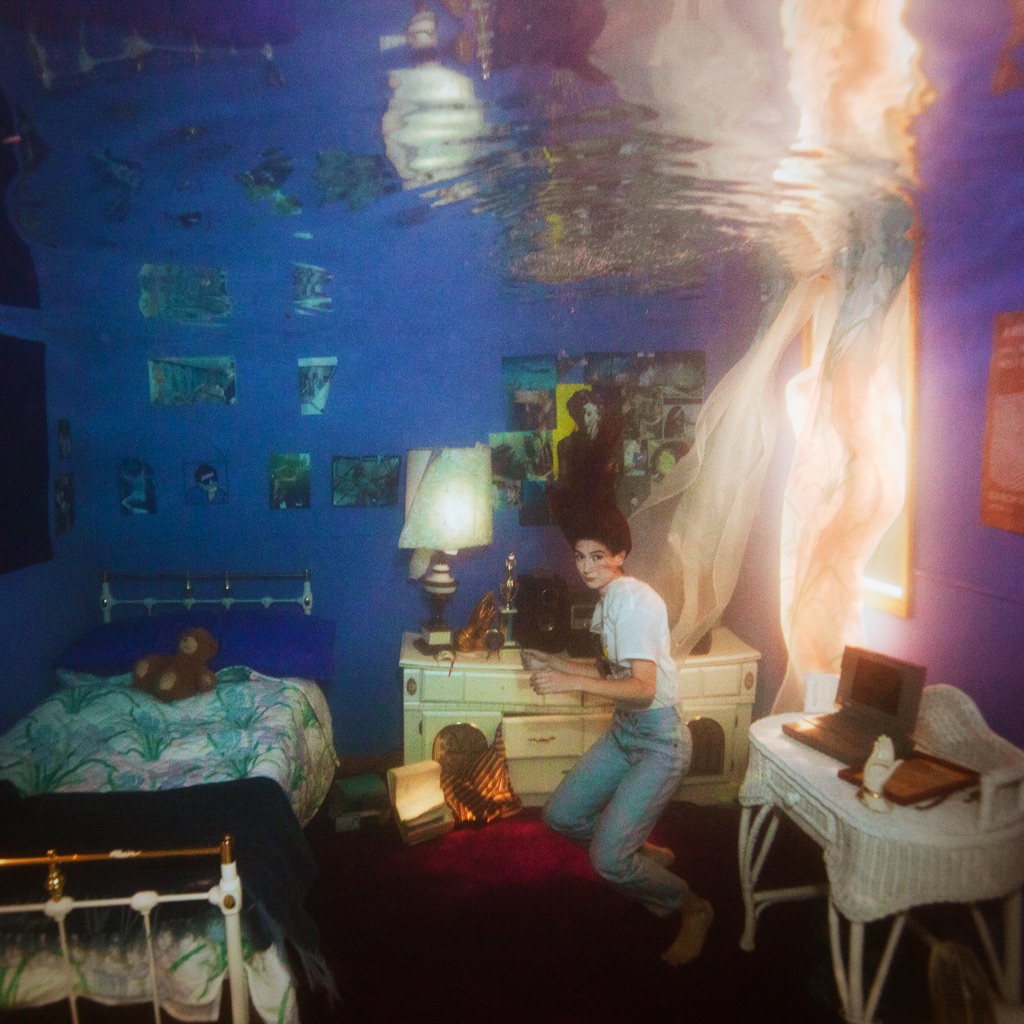

A successful child actor turned indie-rock sweetheart with Rilo Kiley, a solo artist beloved by the famed and famous, Jenny Lewis would appear to have led a gilded life. But her truth—and there have been intimations both in song lyrics and occasionally in interviews—is of a far darker inheritance. “I come from working-class showbiz people who ended up in jail, on drugs, both, or worse,” Lewis tells Apple Music. “I grew up in a pretty crazy, unhealthy environment, but I somehow managed to survive.” The death of her mother in 2017 (with whom she had reconnected after a 20-year estrangement) and the end of her 12-year relationship with fellow singer-songwriter Johnathan Rice set the stage for Lewis’ fourth solo album, where she finally reconciles her public and private self. A bountiful pop record about sex, drugs, death, and regret, with references to everyone from Elliott Smith to Meryl Streep, *On the Line* is the Lewis aesthetic writ large: an autobiographical picaresque burnished by her dark sense of humor. Here, Lewis takes us through the album track by track. **“Heads Gonna Roll”** “I’m a big boxing fan, and I basically wanted to write a boxing ballad. There’s a line about ‘the nuns of Harlem\'—that’s for real. I met a priest backstage at a Dead & Company show in a cloud of pot smoke. He was a fan of my music, and we struck up a conversation and a correspondence. I’d just moved to New York at the time and was looking to do some service work. And so this priest hooked me up with the nuns in Harlem. I would go up there and get really stoned and hang out with theses nuns, who were the purest, most lovely people, and help them put together meal packages. The nuns of Harlem really helped me out.” **“Wasted Youth”** “For me, the thing that really brings this song, and the whole record, together is the people playing on it. \[Drummer\] Jim Keltner especially. He’s played on so many incredible records, he’s the heartbeat of rock and roll and you don’t even realize it. Jim and Don Was were there for so much of this record, and they were the ones that brought Ringo Starr into the sessions—playing with him was just surreal. Benmont Tench is someone I’d worked with before—he’s just so good at referencing things from the past but playing something that sounds modern and new at the same time. He created these sounds that were so melodic and weird, using the Hammond organ and a bunch of pedals. We call that ‘the fog’—Benmont adds the fog.” **“Red Bull & Hennessy”** “I was writing this song, almost predicting the breakup with my longtime partner, while he was in the room. I originally wanted to call it ‘Spark,’ ’cause when that spark goes out in a relationship it’s really hard to get it back.” **“Hollywood Lawn”** “I had this for years and recorded three or four different versions; I did a version with three female vocalists a cappella. Then I went to Jamaica with Savannah and Jimmy Buffett—I actually wrote some songs with Jimmy for the *Escape to Margaritaville* musical that didn’t get used. We didn’t use that version, but I really arranged the s\*\*\* out of it there, and some of the lyrics are about that experience.” **“Do Si Do”** “Wrote this for a friend who went off his psych meds abruptly, which is so dangerous—you have to taper off. I asked Beck to produce it for a reason: He gets in there and wants to add and change chords. And whatever he suggests is always right, of course. That’s a good thing to remember in life: Beck is always right.” “Dogwood” “This is my favorite song on the record. I wrote it on the piano even though I don’t think I’m a very good piano player. I probably should learn more, but I’m just using the instrument as a way to get the song out. This was a live vocal, too. When I’m playing and singing at the same time, I’m approaching the material more as a songwriter rather than a singer, and that changes the whole dynamic in a good way.” **“Party Clown”** “I’d have to describe this as a Faustian love song set at South by Southwest. There’s a line in there where I say, ‘Can you be my puzzle piece, baby?/When I cry like Meryl Streep?’ It’s funny, because Meryl actually did a song of mine, ‘Cold One,’ in *Ricki and the Flash*.” **“Little White Dove”** “Toward the end of the record, I would write songs at home and then visit my mom in the hospital when she was sick. I started this on bass, had the chord structure down, and wrote it at the pace it took to walk from the hospital elevator to the end of the hall. I was able to sing my mom the chorus before she passed.” **“Taffy”** “That one started out as a poem I’d written on an airplane, then it turned into a song. It’s a very specific account of a weekend spent in Wisconsin, and there are some deep Wisconsin references in there. I’m not interested in platitudes, either as a writer or especially as a listener. I want to hear details. That’s why I like hip-hop so much. All those details, names that I haven’t heard, words that have meanings that I don’t understand and have to look up later. I’m interested in those kinds of specifics. That’s also what I love about Bob Dylan songs, too—they’re very, very specific. You can paint an incredibly vivid picture or set a scene or really project a feeling that way.” **“On the Line”** “This is an important song for me. If you read the credits on this record, it says, ‘All songs by Jenny Lewis.’ Being in a band like Rilo Kiley was all about surrendering yourself to the group. And then working with Johnathan for so long, I might have lost a little bit of myself in being a collaborator. It’s nice to know I can create something that’s totally my own. I feel like this got me back to that place.” **“Rabbit Hole”** “The record was supposed to end with ‘On the Line’—the dial tone that closes the song was supposed to be the last thing you hear. But I needed to write ‘Rabbit Hole,’ almost as a mantra for myself: ‘I’m not gonna go/Down the rabbit hole with you.’ I figured the song would be for my next project, but I played it for Beck and he insisted that we put it on this record. It almost feels like a perfect postscript to this whole period of my life.”

You’d think that an artist making her first solo album after nearly 40 years of collaborative work would fall for at least a few pitfalls of sentimentality—the glance in the rearview, the meditation on middle age, the warmth of accomplishment, whatever. Then again, Kim Gordon was never much for soft landings. Noisy, vibrant, and alive with the kind of fragmented poetry that made her presence in Sonic Youth so special, *No Home Record* feels, above all, like a debut—a new voice clocking in for the first time, testing waters, stretching her capacity. The wit is classic (“Airbnb/Could set me free!” she wails on “Air BnB,” channeling the misplaced passions of understimulated yuppies worldwide), as is the vacant sex appeal (“Touch your nipple/You’re so fine!” she wails on “Hungry Baby,” channeling the…misplaced passions of understimulated yuppies worldwide). Most surprising is how informed the album is by electronic music (“Don’t Play It”) and hip-hop (“Paprika Pony,” “Sketch Artist”)—a shift that breaks with the free-rock-saviordom that Sonic Youth always represented while maintaining the continuity of experimentation that made Gordon a pioneer in the first place.

With a career spanning nearly four decades, Kim Gordon is one of the most prolific and visionary artists working today. A co-founder of the legendary Sonic Youth, Gordon has performed all over the world, collaborating with many of music’s most exciting figures including Tony Conrad, Ikue Mori, Julie Cafritz and Stephen Malkmus. Most recently, Gordon has been hitting the road with Body/Head, her spellbinding partnership with artist and musician Bill Nace. Despite the exhaustive nature of her résumé, the most reliable aspect of Gordon’s music may be its resistance to formula. Songs discover themselves as they unspool, each one performing a test of the medium’s possibilities and limits. Her command is astonishing, but Gordon’s artistic curiosity remains the guiding force behind her music. It makes sense that this “American idea” (as Gordon says on the agitated rock track “Air BnB”) of purchasing utopia permeates the record, as no place is this phenomenon more apparent than Los Angeles, where Gordon was born and recently returned to after several lifetimes on the east coast. It was a move precipitated by a number of seismic shifts in her personal life and undoubtedly plays a role in No Home Record’s fascination with transience. The album opens with the restless “Sketch Artist,” where Gordon sings about “dreaming in a tent” as the music shutters and skips like scenery through a car window. “Even Earthquake,” perhaps the record’s most straightforward track embodies this mood; Gordon’s voice wavering like watercolor: “If I could cry and shake for you / I’d lay awake for you / I got sand in my heart for you,” guitar strokes blending into one another as they bleed out across an unstable page. Front to back, No Home Record is an expert operation in the uncanny. You don’t simply listen to Gordon’s music; you experience it.

The cover art for Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ 17th album couldn’t feel more removed from the man once known as a snarling, terrifying prince of poetic darkness. This heavenly forest with its vibrant flowers, rays of sun, and woodland creatures feels comically opposed to anything Cave has ever represented—but perhaps that’s the point. This pastel fairy tale sets the scene for *Ghosteen*, his most minimalist, supernatural work to date, in which he slips between realms of fantasy and reality as a means to accept life and death, his past and future. In his very first post on The Red Hand Files—the website Cave uses to receive and respond to fan letters—he spoke of rebuilding his relationship with songwriting, which had been damaged while enduring the grief that followed his son Arthur’s death in 2015. He wrote, “I found with some practise the imagination could propel itself beyond the personal into a state of wonder. In doing so the colour came back to things with a renewed intensity and the world seemed clear and bright and new.” It is within that state of wonder that *Ghosteen* exists. “The songs on the first album are the children. The songs on the second album are their parents,” Cave has explained. Those eight “children” are misty, ambient stories of flaming mares, enchanted forests, flying ships, and the eponymous, beloved Ghosteen, described as a “migrating spirit.” The second album features two longer pieces, connected by the spoken-word “Fireflies.” He tells fantasy stories that allude to love and loss and letting go, and occasionally brings us back to reality with detailed memories of car rides to the beach and hotel rooms on rainy days. These themes aren’t especially new, but the feeling of this album is. There are no wild murder ballads or raucous, bluesy love songs. Though often melancholy, it doesn’t possess the absolute devastation and loneliness of 2016’s *Skeleton Tree*. Rather, these vignettes and symbolic myths are tranquil and gentle, much like the instrumentation behind them. With little more than synths and piano behind Cave’s vocals, *Ghosteen* might feel uneventful at times, but the calmness seems to help his imagination run free. On “Bright Horses,” he sings of “Horses broken free from the fields/They are horses of love, their manes full of fire.” But then he pulls back the curtain and admits, “We’re all so sick and tired of seeing things as they are/Horses are just horses and their manes aren’t full of fire/The fields are just fields, and there ain’t no lord… This world is plain to see, it don’t mean we can’t believe in something.” Through these dreamlike, surreal stories, Cave is finding his path to peace. And he’s learned that he isn’t alone on his journey. On “Galleon Ship,” he begins, “If I could sail a galleon ship, a long, lonely ride across the sky,” before realizing: “We are not alone, it seems, so many riders in the sky/The winds of longing in their sails, searching for the other side.”

Though she’d been writing songs in her head since she was six, and on the guitar since she was 12, it took a long time for Nilüfer Yanya to work up the courage to show anyone her music. “I knew I wanted to sing, but the idea of actually having to do it was really horrifying,” says the 23-year-old. When she was finally persuaded to do so, by a music teacher in West London where she grew up, she says “it was horrible. I loved it”. At 18, Nilüfer – who is of Turkish-Irish-Bajan heritage – uploaded a few demos to SoundCloud. Though she’s preternaturally shy, her music – which uniquely blends elements of soul and jazz into intimate pop songs with electronic flourishes and a newly expressed grungy guitar sound – isn’t. And it didn’t take long for it to catch people’s attention. She signed with independent New York label ATO, following three EPs on esteemed london indie label Blue Flowers, and earned a place on the BBC Sound of 2018 longlist. She also supported the likes of The xx, Interpol, Broken Social Scene and Mitski on tour. Now, Nilüfer is ready to release her debut album, Miss Universe. Though she recorded much of it in the same remote Cornwall studio she used to jam in as a much younger person, it is bigger and more ambitious than anything she has done before. ‘Angels’, with its muted, harmonic riffs, channels ideas “of paranoid thoughts and anxiety” – a theme that runs through the album, not least in its conceptual spoken word interludes which emanate from a fictional health management company WWAY HEALTH TM. “You sign up, and you pay a fee,” explains Nilüfer of the automated messages, which are littered through the album and are narrated by the titular Miss Universe. “They sort out all of your dietary requirements, and then they move onto medication, and then maybe you can get a better organ or something… and then suddenly it starts to get a bit weird. You're giving them more of you and to what end?”

“Laying in the grass, we were dragging on loud/Got my hand in your hand and my head in the clouds.” This is the scene, set with acoustic atmospherics and frontman Jade Lilitri’s familiar, layered, honey-sweet-but-burnt-around-the-edges vocals, that flickers to life at the start of oso oso’s new full-length, basking in the glow. The track, simply called “intro,” is just that: an intimate, humble, and hopeful prologue that prefaces a record radically committed to letting the light in—because Lilitri knows the darkness like the back of his hand. The spacious opening proposition of “intro” gives way to “the view,” an electric, invigorating indie rock banger that showcases Lilitri’s slick, effortless melodic excellence and lyrical precision (“I’ll grow, we’ll see/There’s something good in me”). The title track follows, driving home the record’s thesis on a chorus like a roman candle cracking a mid-July night sky: “These days, it feels like all I know is this phase/I hope I’m basking in the glow of something bigger I don’t know.” Lead single “dig” rounds out this first act with rainy-day riffing and hushed, staccato vocal delivery on the verse before its tense, charged chorus: “There’s this hole in my soul/So how far do you wanna go?” Lilitri asks, his voice ethereal and couched in bubblegum harmony. It’s a slow build, twining the best parts of emo around pop punk sensibilities and, eventually, wide-open alt-rock anthemics at the track’s climax before sinking back, in a slow-motion fall, to a deserted shoegaze outro. It’s an ambitious, complex scheme, and one that captures the spirit of the record: clutching tight to the unbridled glee of the short, sunny, major-key moments before they dissolve. basking in the glow is a wrestle, and it is hard work; it is the sound of refusing to capitulate to darkness, every goddamn day. It is a practice, or perhaps a battle plan (“I see my demise, I feel it coming/I got one sick plan to save me from it,” Lilitri sings, his voice and hurried guitar crackling as if they’re coming through a bedroom tape recorder.) It is filled with the delightful, subtle melodic imagination that characterizes the sound Lilitri has perfected with oso oso, but this time out, he’s put this sound to use declaring happiness (“I got a glimpse of this feeling, I’m trying to stay in that lane,” on “impossible game”) and sketching out, with keen, desperate detail, warm memories to hold onto (“‘Oh c’mon Charlie, a little louder’/I say as I hear her singing out from the shower,” on “charlie”). This “one sick plan” and its bright disposition does falter and fade. The darkness does return—it always will—but Lilitri has come to terms with it, armoring himself with the good he’s found. Even as the record ends with a relationship’s demise, Lilitri is clear-eyed, leaving us squarely in the sunlight: “And in the end I think that’s fine/Cause you and I had a very nice time.”

There are musicians who suffer for their art, and then there’s Stefan Babcock. The guitarist and lead screamer for Toronto pop-punk ragers PUP has often used his music as a bullhorn to address the physical and mental toll of being in a touring rock band. The band’s 2016 album *The Dream Is Over* was inspired by Babcock seeking treatment for his ravaged vocal cords and being told by a doctor he’d never be able to sing again. Now, with that scare behind him, he’s using the aptly titled *Morbid Stuff* to address a more insidious ailment: depression. “*The Dream Is Over* was riddled with anxiety and uncertainties, but I think I was expressing myself in a more immature way,” Babcock tells Apple Music. “I feel I’ve found the language to better express those things.” Certainly, *Morbid Stuff* pulls no punches: This is an album whose idea of an opening line is “I was bored as fuck/Sitting around and thinking all this morbid stuff/Like if anyone I slept with is dead.” But of course, this being PUP—a band that built their fervent fan base through their wonderfully absurd high-concept videos—they can’t help but make a little light of the darkest subject matter. “I’m pretty aware of the fact I’m making money off my own misery—what Phoebe Bridgers called ‘the commodification of depression,’” Babcock says. “It’s a weird thing to talk about mood disorders for a living. But my intention with this record was to explore the darker things with a bit of humor, and try to make people feel less alone while they listen to it.” To that end, Babcock often directs his most scathing one-liners at himself. On the instant shout-along anthem “Free at Last,” he issues a self-diagnosis that hits like a glass of cold water in the face: “Just because you’re sad again/It doesn’t make you special at all.” “The conversation around mental health that’s happening now is such a positive thing,” Babcock says, “but one of the small drawbacks is that people are now so sympathetic to it that some people who suffer from mood disorders—and I speak from experience here—tend to use it as a crutch. I can sometimes say something to my bandmates or my girlfriend that’s pretty shitty, and they’ll be like, ‘It’s okay, Stefan’s in a different headspace right now’—and that’s *not* okay. It’s important to remind myself and other people that being depressed and being an asshole are not mutually exclusive.” Complementing Babcock’s fearless lyricism is the band’s growing confidence to step outside of the circle pit: “Scorpion Hill” begins as a lonesome barstool serenade before kicking into a dusty cowpunk gallop, while the power-pop rave-up “Closure” simmers into a sweet psychedelic breakdown that nods to one of Babcock’s all-time favorite bands, Built to Spill. And the closing “City” is PUP’s most vulnerable statement to date, a pulverizing power ballad where Babcock takes stock of his conflicted relationship with Toronto, his lifelong home. “The beginning of ‘Scorpion Hill’ and ‘City’ are by far the most mellow, softest moments we’ve ever created as a band,” Babcock says. “And I think on the last two records, we never would’ve gone there—not because we didn’t want to, but just because we didn’t think people would accept PUP if PUP wasn’t always cranked up to 10. And this time, we felt a bit more confident to dial it back in certain parts when it felt right. I feel like we’ve grown a lot as a band and shed some of our inhibitions.”

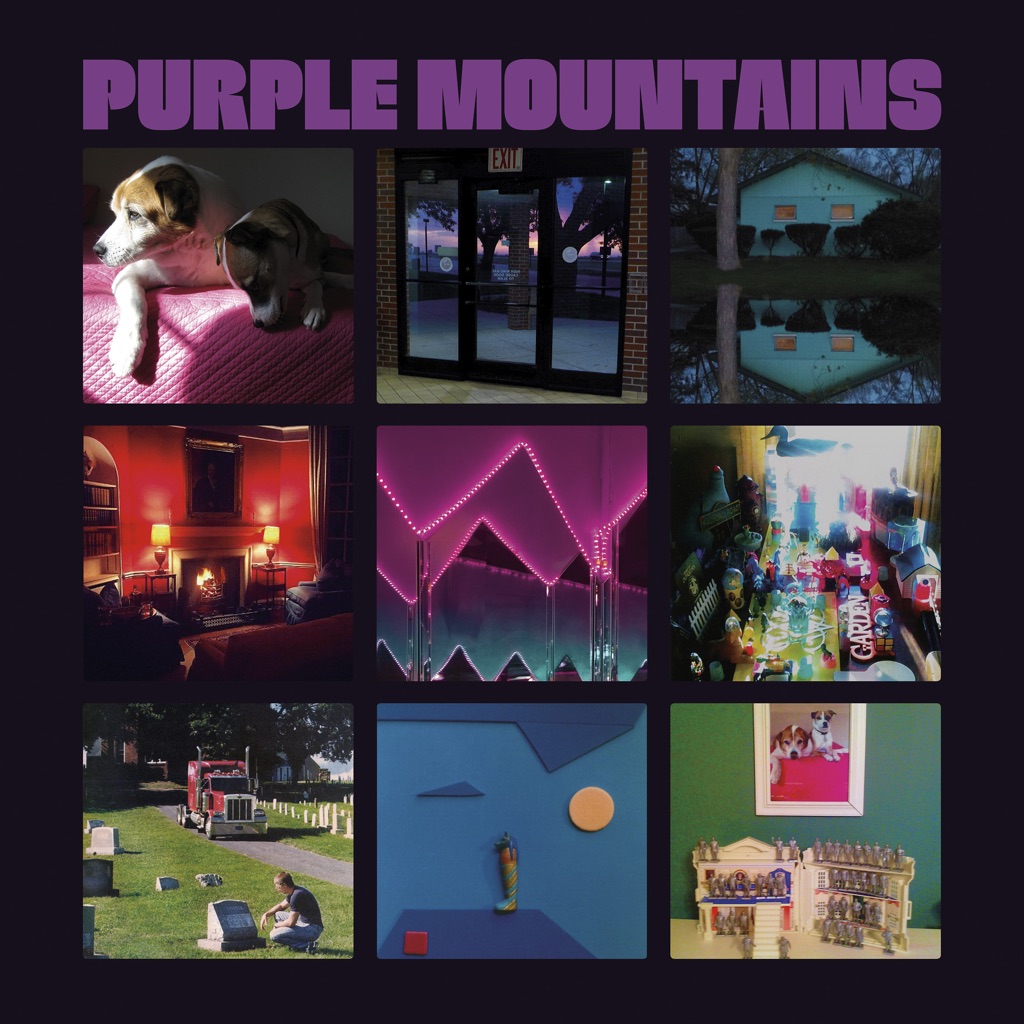

When David Berman disbanded Silver Jews in 2009, the world stood to lose one of the best writers in indie rock, a guy who catalogued the magic and misery of everyday life with wit, heart, and the ragged glory of the occupationally down-and-out. After a 10-year break professedly spent reading books and arguing with people on Reddit, Berman enlisted members of the Brooklyn band Woods to back him on *Purple Mountains*. Berman’s pain had never been laid quite so bare, nor had it ever sounded quite so urgent. “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion,” he sings on the swaggering “That’s Just the Way I Feel.” “Day to day, I’m neck and neck with giving in.” And “Margaritas at the Mall” turns an ordinary happy hour into a jeremiad about the cold comforts of capitalism in a godless world. That the music—country-tinged indie rock—was as polished and competent as it was only highlighted Berman’s intensity: less a rock singer than a street preacher, someone who needed to avail himself of his visions stat. But even at his most desperate, he remained achingly funny, turning statements of existential loneliness into the kind of bumper sticker Zen that made him seem like an ordinary guy no matter how highfalutin he could get. “Well, if no one’s fond of fuckin’ me, maybe no one’s fuckin’ fond of me,” he sings on the album-closing “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” sounding not all that far off from the George Strait one-twos he reportedly loved. Above all, though, his writing is beautiful, attuned to detail in ways that make ordinary scenarios shimmer with quiet magic. Just listen to “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan,” which turns a quiet night in a big city into an allegory of finding solace in the weather of what comes to us. Shortly after the release of *Purple Mountains*, Berman died, at the age of 52, a tragic end to what felt like a triumphant return. “The dead know what they\'re doing when they leave this world behind,” he sings on “Nights That Won’t Happen.” “When the here and the hereafter momentarily align.”

David Berman comes in from the cold after ten long years. His new musical expression is a meltdown unparalleled in modern memory. He warns us that his findings might be candid, but as long as his punishment comes in such bite-sized delights of all-American jukebox fare, we'll hike the Purple Mountains with pleasure forever.

On her fifth proper full-length album, Sharon Van Etten pushes beyond vocals-and-guitar indie rock and dives headlong into spooky maximalism. With production help from John Congleton (St. Vincent), she layers haunting drones with heavy, percussive textures, giving songs like “Comeback Kid” and “Seventeen” explosive urgency. Drawing from Nick Cave, Lucinda Williams, and fellow New Jersey native Bruce Springsteen, *Remind Me Tomorrow* is full of electrifying anthems, with Van Etten voicing confessions of reckless, lost, and sentimental characters. The album challenges the popular image of Van Etten as *just* a singer-songwriter and illuminates her significant talent as composer and producer, as an artist making records that feel like a world of their own.

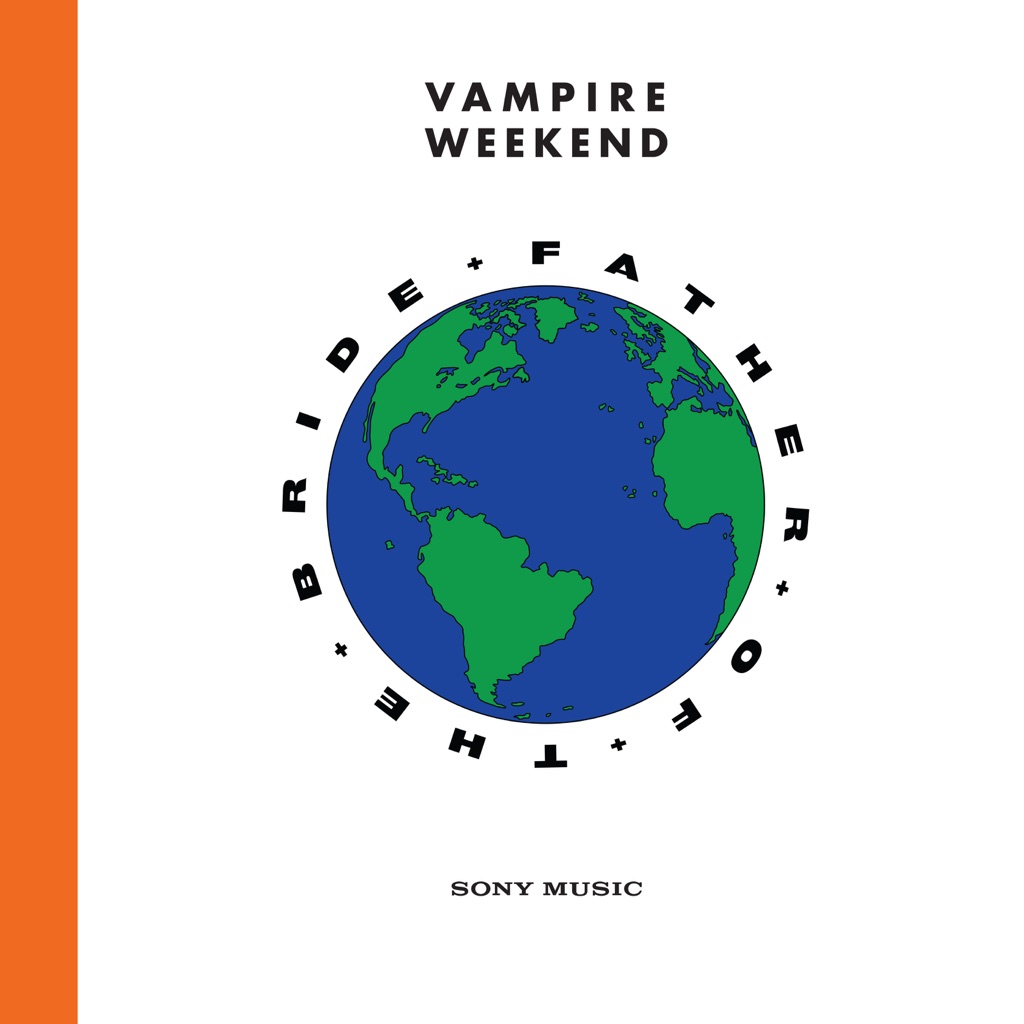

“It feels right that our fourth album is not 10, 11 songs,” Vampire Weekend frontman Ezra Koenig explains on his Beats 1 show *Time Crisis*, laying out the reasoning behind the 18-track breadth of his band\'s first album in six years. “It felt like it needed more room.” The double album—which Koenig considers less akin to the stylistic variety of The Beatles\' White Album and closer to the narrative and thematic cohesion of Bruce Springsteen\'s *The River*—also introduces some personnel changes. Founding member Rostam Batmanglij contributes to a couple of tracks but is no longer in the band, while Haim\'s Danielle Haim and The Internet\'s Steve Lacy are among the guests who play on multiple songs here. The result is decidedly looser and more sprawling than previous Vampire Weekend records, which Koenig feels is an apt way to return after a long hiatus. “After six years gone, it\'s a bigger statement.” Here Koenig unpacks some of *Father of the Bride*\'s key tracks. **\"Hold You Now\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “From pretty early on, I had a feeling that\'d be a good track one. I like that it opens with just acoustic guitar and vocals, which I thought is such a weird way to open a Vampire Weekend record. I always knew that there should be three duets spread out around the album, and I always knew I wanted them to be with the same person. Thank God it ended up being with Danielle. I wouldn\'t really call them country, but clearly they\'re indebted to classic country-duet songwriting.” **\"Rich Man\"** “I actually remember when I first started writing that; it was when we were at the Grammys for \[2013\'s\] *Modern Vampires of the City*. Sometimes you work so hard to come up with ideas, and you\'re down in the mines just trying to come up with stuff. Then other times you\'re just about to leave, you listen to something, you come up with a little idea. On this long album, with songs like this and \'Big Blue,\' they\'re like these short-story songs—they\'re moments. I just thought there\'s something funny about the narrator of the song being like, \'It\'s so hard to find one rich man in town with a satisfied mind. But I am the one.\' It\'s the trippiest song on the album.” **\"Married in a Gold Rush\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “I played this song for a couple of people, and some were like, \'Oh, that\'s your country song?\' And I swear, we pulled our hair out trying to make sure the song didn\'t sound too country. Once you get past some of the imagery—midnight train, whatever—that\'s not really what it\'s about. The story is underneath it.” **\"Sympathy”** “That\'s the most metal Vampire Weekend\'s ever gotten with the double bass drum pedal.” **\"Sunflower\" (feat. Steve Lacy)** “I\'ve been critical of certain references people throw at this record. But if people want to say this sounds a little like Phish, I\'m with that.” **\"We Belong Together\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “That\'s kind of two different songs that came together, as is often the case of Vampire Weekend. We had this old demo that started with programmed drums and Rostam having that 12-string. I always wanted to do a song that was insanely simple, that was just listing things that go together. So I\'d sit at the piano and go, \'We go together like pots and pans, surf and sand, bottles and cans.\' Then we mashed them up. It\'s probably the most wholesome Vampire Weekend song.”

Singer-songwriter Natalie Mering’s fourth album as Weyes Blood conjures the feeling of a beautiful object on a shelf just out of reach: You want to touch it, but you can’t, and so you do the next best thing—you dream about it, ache for it, and then you ache some more. Grand, melodramatic, but keenly self-aware, the music here pushes Mering’s \'70s-style chamber pop to its cinematic brink, suffusing stories of everything from fumbled romance (the McCartney-esque “Everyday”) to environmental apocalypse (“Wild Time”) with a dreamy, foggy almost-thereness both gorgeous and profoundly unsettling. A self-described “nostalgic futurist,” Mering doesn’t recreate the past so much as demonstrate how the past is more or less a fiction to begin with, a story we love hearing no matter how sad its unreachability makes us. Hence the album’s centerpiece, “Movies,” which wonders—gorgeously, almost religiously—why life feels so messy by comparison. As to the thematic undercurrent of apocalypse, well, if extinction is as close as science says it is, we might as well have something pretty to play us out.

The phantom zone, the parallax, the upside down—there is a rich cultural history of exploring in-between places. Through her latest, Titanic Rising, Weyes Blood (a.k.a. Natalie Mering) has, too, designed her own universe to soulfully navigate life’s mysteries. Maneuvering through a space-time continuum, she intriguingly plays the role of melodic, sometimes melancholic, anthropologist. Tellingly, Mering classifies Titanic Rising as the Kinks meet WWII or Bob Seger meets Enya. The latter captures the album’s willful expansiveness (“You can tell there’s not a guy pulling the strings in Enya’s studio,” she notes, admiringly). The former relays her imperative to connect with listeners. “The clarity of Bob Seger is unmistakable. I’m a big fan of conversational songwriting,” she adds. “I just try to do that in a way that uses abstract imagery as well.” “An album is like a Rubik’s Cube,” she says. “Sometimes you get all the dimensions—the lyrics, the melody, the production—to line up. I try to be futuristic and ancient at once, which is a difficult alchemy. It’s taken a lot of different tries to get it right.” As concept-album as it may sound, it’s also a devoted exercise in realism, albeit occasionally magical. Here, the throwback-cinema grandeur of “A Lot’s Gonna Change” gracefully coexists with the otherworldly title track, an ominous instrumental. Titanic Rising, written and recorded during the first half of 2018, is the culmination of three albums and years of touring: stronger chops and ballsier decisions. It’s an achievement in transcendent vocals and levitating arrangements—one she could reach only by flying under the radar for so many years. “I used to want to belong,” says the L.A. based musician. “I realized I had to forge my own path. Nobody was going to do that for me. That was liberating. I became a Joan of Arc solo musician.” The Weyes Blood frontwoman grew up singing in gospel and madrigal choirs. “Classical and Renaissance music really influenced me,” says Mering, who first picked up a guitar at age 8. (Listen closely to Titanic Rising, and you’ll also hear the jazz of Hoagy Carmichael mingle with the artful mysticism of Alejandro Jodorowsky and the monomyth of scholar Joseph Campbell.) “Something to Believe,” a confessional that makes judicious use of the slide guitar, touches on that cosmological upbringing. “Belief is something all humans need. Shared myths are part of our psychology and survival,” she says. “Now we have a weird mishmash of capitalism and movies and science. There have been moments where I felt very existential and lost.” As a kid, she filled that void with Titanic. (Yes, the movie.) “It was engineered for little girls and had its own mythology,” she explains. Mering also noticed that the blockbuster romance actually offered a story about loss born of man’s hubris. “It’s so symbolic that The Titanic would crash into an iceberg, and now that iceberg is melting, sinking civilization.” Today, this hubris also extends to the relentless adoption of technology, at the expense of both happiness and attention spans. The track “Movies” marks another Titanic-related epiphany, “that movies had been brainwashing people and their ideas about romantic love.” To that end, Mering has become an expert at deconstructing intimacy. Sweeping and string-laden, “Andromeda” seems engineered to fibrillate hearts. “It’s about losing your interest in trying to be in love,” she says. “Everybody is their own galaxy, their own separate entity. There is a feeling of needing to be saved, and that’s a lot to ask of people.” Its companion track, “Everyday,” “is about the chaos of modern dating,” she says, “the idea of sailing off onto your ships to nowhere to deal with all your baggage.” But Weyes Blood isn’t one to stew. Her observations play out in an ethereal saunter: far more meditative than cynical. “I experience reality on a slower, more hypnotic level,” she says. “I’m a more contemplative kind of writer.” To Mering, listening and thinking are concurrent experiences. “There are complicated influences mixed in with more relatable nostalgic melodies,” she says. “In my mind my music feels so big, a true production. I’m not a huge, popular artist, but I feel like one when I’m in the studio. But it’s never taking away from the music. I’m just making a bigger space for myself.”