Obscure Sound's Best Albums of 2019

Obscure Sound kicks off featuring the best albums of 2019.

Published: December 17, 2019 18:38

Source

From the outset of his fame—or, in his earliest years as an artist, infamy—Tyler, The Creator made no secret of his idolization of Pharrell, citing the work the singer-rapper-producer did as a member of N.E.R.D as one of his biggest musical influences. The impression Skateboard P left on Tyler was palpable from the very beginning, but nowhere is it more prevalent than on his fifth official solo album, *IGOR*. Within it, Tyler is almost completely untethered from the rabble-rousing (and preternaturally gifted) MC he broke out as, instead pushing his singing voice further than ever to sound off on love as a life-altering experience over some synth-heavy backdrops. The revelations here are mostly literal. “I think I’m falling in love/This time I think it\'s for real,” goes the chorus of the pop-funk ditty “I THINK,” while Tyler can be found trying to \"make you love me” on the R&B-tinged “RUNNING OUT OF TIME.” The sludgy “NEW MAGIC WAND” has him begging, “Please don’t leave me now,” and the album’s final song asks, “ARE WE STILL FRIENDS?” but it’s hardly a completely mopey affair. “IGOR\'S THEME,” the aforementioned “I THINK,” and “WHAT\'S GOOD” are some of Tyler’s most danceable songs to date, featuring elements of jazz, funk, and even gospel. *IGOR*\'s guests include Playboi Carti, Charlie Wilson, and Kanye West, whose voices are all distorted ever so slightly to help them fit into Tyler\'s ever-experimental, N.E.R.D-honoring vision of love.

Singer-songwriter Natalie Mering’s fourth album as Weyes Blood conjures the feeling of a beautiful object on a shelf just out of reach: You want to touch it, but you can’t, and so you do the next best thing—you dream about it, ache for it, and then you ache some more. Grand, melodramatic, but keenly self-aware, the music here pushes Mering’s \'70s-style chamber pop to its cinematic brink, suffusing stories of everything from fumbled romance (the McCartney-esque “Everyday”) to environmental apocalypse (“Wild Time”) with a dreamy, foggy almost-thereness both gorgeous and profoundly unsettling. A self-described “nostalgic futurist,” Mering doesn’t recreate the past so much as demonstrate how the past is more or less a fiction to begin with, a story we love hearing no matter how sad its unreachability makes us. Hence the album’s centerpiece, “Movies,” which wonders—gorgeously, almost religiously—why life feels so messy by comparison. As to the thematic undercurrent of apocalypse, well, if extinction is as close as science says it is, we might as well have something pretty to play us out.

The phantom zone, the parallax, the upside down—there is a rich cultural history of exploring in-between places. Through her latest, Titanic Rising, Weyes Blood (a.k.a. Natalie Mering) has, too, designed her own universe to soulfully navigate life’s mysteries. Maneuvering through a space-time continuum, she intriguingly plays the role of melodic, sometimes melancholic, anthropologist. Tellingly, Mering classifies Titanic Rising as the Kinks meet WWII or Bob Seger meets Enya. The latter captures the album’s willful expansiveness (“You can tell there’s not a guy pulling the strings in Enya’s studio,” she notes, admiringly). The former relays her imperative to connect with listeners. “The clarity of Bob Seger is unmistakable. I’m a big fan of conversational songwriting,” she adds. “I just try to do that in a way that uses abstract imagery as well.” “An album is like a Rubik’s Cube,” she says. “Sometimes you get all the dimensions—the lyrics, the melody, the production—to line up. I try to be futuristic and ancient at once, which is a difficult alchemy. It’s taken a lot of different tries to get it right.” As concept-album as it may sound, it’s also a devoted exercise in realism, albeit occasionally magical. Here, the throwback-cinema grandeur of “A Lot’s Gonna Change” gracefully coexists with the otherworldly title track, an ominous instrumental. Titanic Rising, written and recorded during the first half of 2018, is the culmination of three albums and years of touring: stronger chops and ballsier decisions. It’s an achievement in transcendent vocals and levitating arrangements—one she could reach only by flying under the radar for so many years. “I used to want to belong,” says the L.A. based musician. “I realized I had to forge my own path. Nobody was going to do that for me. That was liberating. I became a Joan of Arc solo musician.” The Weyes Blood frontwoman grew up singing in gospel and madrigal choirs. “Classical and Renaissance music really influenced me,” says Mering, who first picked up a guitar at age 8. (Listen closely to Titanic Rising, and you’ll also hear the jazz of Hoagy Carmichael mingle with the artful mysticism of Alejandro Jodorowsky and the monomyth of scholar Joseph Campbell.) “Something to Believe,” a confessional that makes judicious use of the slide guitar, touches on that cosmological upbringing. “Belief is something all humans need. Shared myths are part of our psychology and survival,” she says. “Now we have a weird mishmash of capitalism and movies and science. There have been moments where I felt very existential and lost.” As a kid, she filled that void with Titanic. (Yes, the movie.) “It was engineered for little girls and had its own mythology,” she explains. Mering also noticed that the blockbuster romance actually offered a story about loss born of man’s hubris. “It’s so symbolic that The Titanic would crash into an iceberg, and now that iceberg is melting, sinking civilization.” Today, this hubris also extends to the relentless adoption of technology, at the expense of both happiness and attention spans. The track “Movies” marks another Titanic-related epiphany, “that movies had been brainwashing people and their ideas about romantic love.” To that end, Mering has become an expert at deconstructing intimacy. Sweeping and string-laden, “Andromeda” seems engineered to fibrillate hearts. “It’s about losing your interest in trying to be in love,” she says. “Everybody is their own galaxy, their own separate entity. There is a feeling of needing to be saved, and that’s a lot to ask of people.” Its companion track, “Everyday,” “is about the chaos of modern dating,” she says, “the idea of sailing off onto your ships to nowhere to deal with all your baggage.” But Weyes Blood isn’t one to stew. Her observations play out in an ethereal saunter: far more meditative than cynical. “I experience reality on a slower, more hypnotic level,” she says. “I’m a more contemplative kind of writer.” To Mering, listening and thinking are concurrent experiences. “There are complicated influences mixed in with more relatable nostalgic melodies,” she says. “In my mind my music feels so big, a true production. I’m not a huge, popular artist, but I feel like one when I’m in the studio. But it’s never taking away from the music. I’m just making a bigger space for myself.”

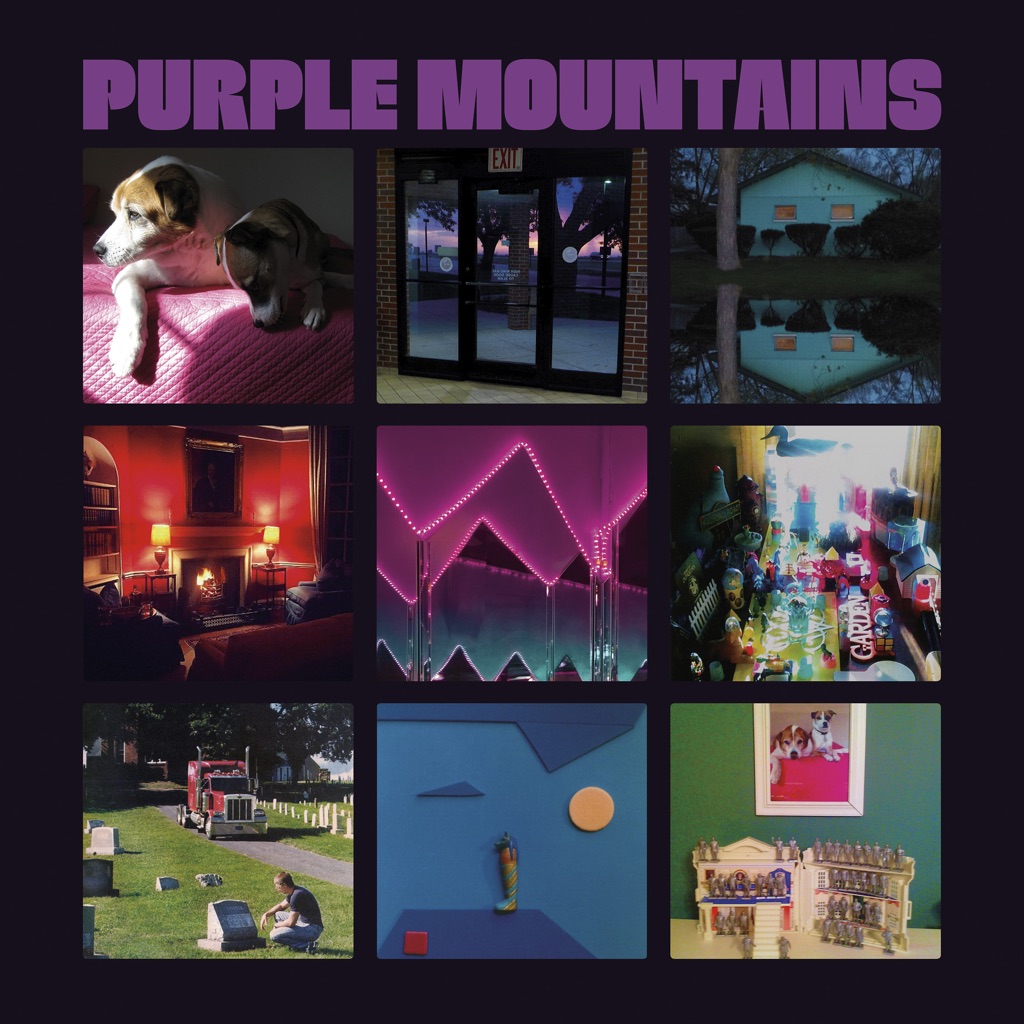

When David Berman disbanded Silver Jews in 2009, the world stood to lose one of the best writers in indie rock, a guy who catalogued the magic and misery of everyday life with wit, heart, and the ragged glory of the occupationally down-and-out. After a 10-year break professedly spent reading books and arguing with people on Reddit, Berman enlisted members of the Brooklyn band Woods to back him on *Purple Mountains*. Berman’s pain had never been laid quite so bare, nor had it ever sounded quite so urgent. “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion,” he sings on the swaggering “That’s Just the Way I Feel.” “Day to day, I’m neck and neck with giving in.” And “Margaritas at the Mall” turns an ordinary happy hour into a jeremiad about the cold comforts of capitalism in a godless world. That the music—country-tinged indie rock—was as polished and competent as it was only highlighted Berman’s intensity: less a rock singer than a street preacher, someone who needed to avail himself of his visions stat. But even at his most desperate, he remained achingly funny, turning statements of existential loneliness into the kind of bumper sticker Zen that made him seem like an ordinary guy no matter how highfalutin he could get. “Well, if no one’s fond of fuckin’ me, maybe no one’s fuckin’ fond of me,” he sings on the album-closing “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” sounding not all that far off from the George Strait one-twos he reportedly loved. Above all, though, his writing is beautiful, attuned to detail in ways that make ordinary scenarios shimmer with quiet magic. Just listen to “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan,” which turns a quiet night in a big city into an allegory of finding solace in the weather of what comes to us. Shortly after the release of *Purple Mountains*, Berman died, at the age of 52, a tragic end to what felt like a triumphant return. “The dead know what they\'re doing when they leave this world behind,” he sings on “Nights That Won’t Happen.” “When the here and the hereafter momentarily align.”

David Berman comes in from the cold after ten long years. His new musical expression is a meltdown unparalleled in modern memory. He warns us that his findings might be candid, but as long as his punishment comes in such bite-sized delights of all-American jukebox fare, we'll hike the Purple Mountains with pleasure forever.

In a lot of ways, you can map Alex Giannascoli’s story onto a broader story of music and art in the 2010s. Born outside Philadelphia in 1993, he started self-releasing albums online while still in high school, building a small but devoted cult that scrutinized his collage-like indie folk like it was scripture. His music got denser, more expressive, and more accomplished, he signed to venerated indie label Domino, and he worked with Frank Ocean, all—more or less—without leaving his bedroom. In other words, Giannascoli didn’t have to leave his dream-hive to find an audience; he brought his audience in, and on his terms, too. “Something I can never stress enough is I try and explain this stuff, but it never accurately reflects the process,” Giannascoli tells Apple Music, “because I’m not actually thinking that much when I’m doing it.” Recorded in the same building-block fashion as his previous albums (and with the same home studio setup), *House of Sugar* represents a new peak for Giannascoli—not just as a songwriter, but as a producer who can spin peculiar moods out of combinations that don’t make any immediate sense. It can be blissful (“Walk Away”), it can be ominous (“Sugar”), it can be grounded one minute (“Cow,” “Hope,” “Southern Sky”) and abstract the next (“Near,” “Project 2”)—a range that gives the overall experience the disjointed, saturated feeling of a half-remembered dream. Often, the prettier the music is, the bleaker the lives of the characters in the lyrics get, whether it’s the drug casualty of “Hope” or the gamblers of “SugarHouse,” who keep coming back to the tables no matter how often they lose—a contrast, Giannascoli says, that was inspired in part by the 2018 sci-fi film *Annihilation*. “From afar, everything looks bright and beautiful,” he says, “but the closer you get, the more violent it becomes.” Despite his rising profile, Giannascoli tries to remain intuitive, following inspiration whenever it shows up, keeping what he calls “that lens” on whenever possible. “I never say to myself, ‘This isn’t where I thought \[the music\] was going to go,’” he says. “Because usually I don’t have that thought in mind to begin with. And I never really end up getting surprised, because the music is unfolding before me as I make it.”

House of Sugar— Alex G’s ninth overall album and his third for Domino — emerges as his most meticulous, cohesive album yet: a statement of artistic purpose, showing off his ear for both persistent earworms and sonic adventurism.

After releasing 2016’s *The Colour in Anything*, James Blake moved from London to Los Angeles, where he found himself busier than ever. “I’ve been doing a lot of production work, a lot of writing for other people and projects,” he tells Apple Music. “I think the constant process of having a mirror held up to your music in the form of other people’s music, and other people, helped me cross something. A shiny new thing.” That thing—his fourth album, *Assume Form*—is his least abstract and most grounded, revealing and romantic album to date. Here, Blake pulls back the curtain and explains the themes, stories and collaborations behind each track. **“Assume Form”** “I\'m saying, ‘The plan is to become reachable, to assume material form, to leave my head and join the world.’ It seems like quite a modern, Western idea that you just get lost. These slight feelings of repression lead to this feeling of *I’m not in my body, I’m not really experiencing life through first-person. It’s like I’m looking at it from above*. Which is a phenomenon a lot of people describe when they talk about depression.” **“Mile High” (feat. Metro Boomin & Travis Scott)** “Travis is just exceptionally talented at melodies; the ones he wrote on that track are brilliant. And it was made possible by Metro—the beat is a huge part of why that track feels the way it does.” **“Tell Them” (feat. Metro Boomin & Moses Sumney)** “Moses came on tour with me a couple years ago. I watched him get a standing ovation every night, and that was when he was a support act. For me, it’s a monologue on a one-night stand: There’s fear, there’s not wanting to be too close to anybody. Just sort of a self-analysis, really.” **“Into the Red”** “‘Into the Red’ is about a woman in my life who was very giving—someone who put me before themselves, and spent the last of their money on something for me. It was just a really beautiful sentiment—especially the antithesis of the idea that the man pays. I just liked that idea of equal footing.” **“Barefoot in the Park” (feat. ROSALÍA)** “My manager played me \[ROSALÍA’s 2017 debut\] *Los Ángeles*, and I honestly hadn’t heard anything so vulnerable and raw and devastating in quite a while. She came to the studio, and within a day we’d made two or three things. I loved the sound of our voices together.” **“Can’t Believe the Way We Flow”** “It’s a pure love song, really. It’s just about the ease of coexisting that I feel with my girlfriend. It’s fairly simple in its message and in its delivery, hopefully. Romance is a very commercialized subject, but sometimes it can just be a peaceful moment of ease and something even mundane—just the flow between days and somebody making it feel like the days are just going by, and that’s a great thing.” **“Are You in Love?”** “I like the idea of that moment where neither of you know whether you’re in love yet, but there’s this need for someone to just say they are: ‘Give me assurance that this is good and that we’re good, and that you’re in love with me. I’m in love with you.’ The words might mean more in that moment, but that’s not necessarily gonna make it okay.” **“Where’s the Catch?” (feat. André 3000)** “I was, and remain, inspired by Outkast. Catching him now is maybe even *more* special to me, because the way he writes is just so good! I love the way he balances slight abstraction with this feeling of paranoia. The line ‘Like I know I’m eight, and I know I ain’t’—anxiety bringing you back to being a child, but knowing that you’re supposed to feel strong and stable because you’re an adult now. That’s just so beautifully put.” **“I’ll Come Too”** “It’s a real story: When you fall in love, the practical things go out the window, a little bit. And you just want to go to wherever they are.” **“Power On”** “It’s about being in a relationship, and being someone who gets something wrong. If you can swallow your ego a little bit and accept that you aren’t always to know everything, that this person can actually teach you a lot, the better it is for everyone. Once I’ve taken accountability, it’s time to power on—that’s the only way I can be worthy of somebody’s love and affection and time.” **“Don’t Miss It”** “Coming at the end of the album was a choice. I think it kind of sums up the mission statement in some ways: Yes, there are millions of things that I could fixate on, and I have lost years and years and years to anxiety. There are big chunks of my life I can’t remember—moments I didn’t enjoy when I should have. Loves I wasn’t a part of. Heroes I met that I can’t really remember the feeling of meeting. Because I was so wrapped up in myself. And I think that’s what this is—the inner monologue of an egomaniac.” **“Lullaby for My Insomniac”** “I literally wrote it to help someone sleep. This is just me trying to calm the waters so you can just drift off. It does what it says on the tin.”

Two years after stirring up a murky swirl of psychedelic folk on *Eucalyptus*, Dave Portner sounds like he’s in a brighter mood on *Cows on Hourglass Pond*, his third solo album away from his day job in Animal Collective. The energy levels here don’t quite match the kaleidoscopic, kinetic overload of his group at their most madcap, but jangly guitars lend a cheerful air to songs like the breathless “Eyes on Eyes” and “Saturdays (Again),” while dub-techno beats (“What’s the Goodside?”) and inventive sound design (“Our Little Chapter”) find Portner continuing to push himself sonically. And as centerpiece “K.C. Yours” attests, his imagination has never been in sharper form: Set to a groove that’s both wistful and rollicking, the song vividly imagines a post-apocalyptic scenario in which robot overlords rule everything, even love.

Cows On Hourglass Pond was recorded between January - March 2018 by Dave Portner at Laughing Gas in Asheville, NC on a Tascam 48 half-inch reel-to-reel tape machine.

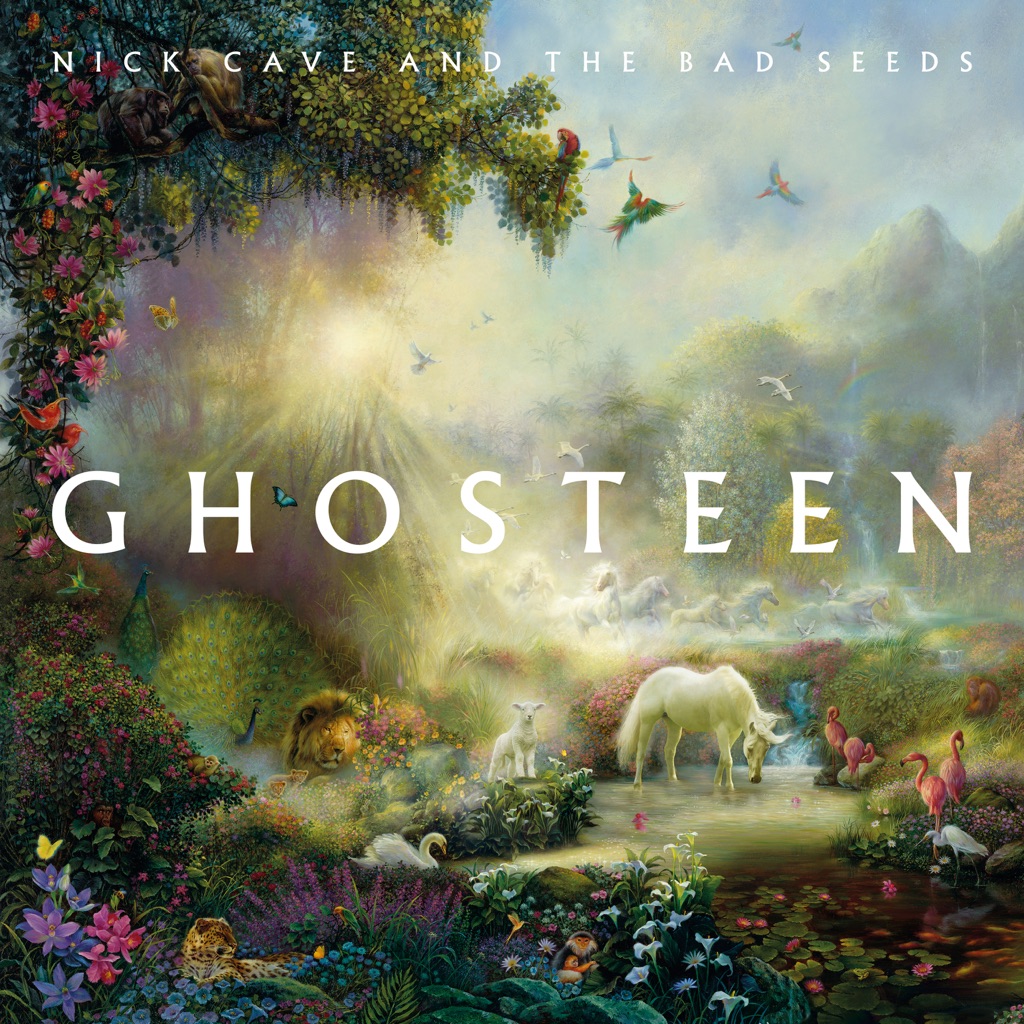

The cover art for Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ 17th album couldn’t feel more removed from the man once known as a snarling, terrifying prince of poetic darkness. This heavenly forest with its vibrant flowers, rays of sun, and woodland creatures feels comically opposed to anything Cave has ever represented—but perhaps that’s the point. This pastel fairy tale sets the scene for *Ghosteen*, his most minimalist, supernatural work to date, in which he slips between realms of fantasy and reality as a means to accept life and death, his past and future. In his very first post on The Red Hand Files—the website Cave uses to receive and respond to fan letters—he spoke of rebuilding his relationship with songwriting, which had been damaged while enduring the grief that followed his son Arthur’s death in 2015. He wrote, “I found with some practise the imagination could propel itself beyond the personal into a state of wonder. In doing so the colour came back to things with a renewed intensity and the world seemed clear and bright and new.” It is within that state of wonder that *Ghosteen* exists. “The songs on the first album are the children. The songs on the second album are their parents,” Cave has explained. Those eight “children” are misty, ambient stories of flaming mares, enchanted forests, flying ships, and the eponymous, beloved Ghosteen, described as a “migrating spirit.” The second album features two longer pieces, connected by the spoken-word “Fireflies.” He tells fantasy stories that allude to love and loss and letting go, and occasionally brings us back to reality with detailed memories of car rides to the beach and hotel rooms on rainy days. These themes aren’t especially new, but the feeling of this album is. There are no wild murder ballads or raucous, bluesy love songs. Though often melancholy, it doesn’t possess the absolute devastation and loneliness of 2016’s *Skeleton Tree*. Rather, these vignettes and symbolic myths are tranquil and gentle, much like the instrumentation behind them. With little more than synths and piano behind Cave’s vocals, *Ghosteen* might feel uneventful at times, but the calmness seems to help his imagination run free. On “Bright Horses,” he sings of “Horses broken free from the fields/They are horses of love, their manes full of fire.” But then he pulls back the curtain and admits, “We’re all so sick and tired of seeing things as they are/Horses are just horses and their manes aren’t full of fire/The fields are just fields, and there ain’t no lord… This world is plain to see, it don’t mean we can’t believe in something.” Through these dreamlike, surreal stories, Cave is finding his path to peace. And he’s learned that he isn’t alone on his journey. On “Galleon Ship,” he begins, “If I could sail a galleon ship, a long, lonely ride across the sky,” before realizing: “We are not alone, it seems, so many riders in the sky/The winds of longing in their sails, searching for the other side.”

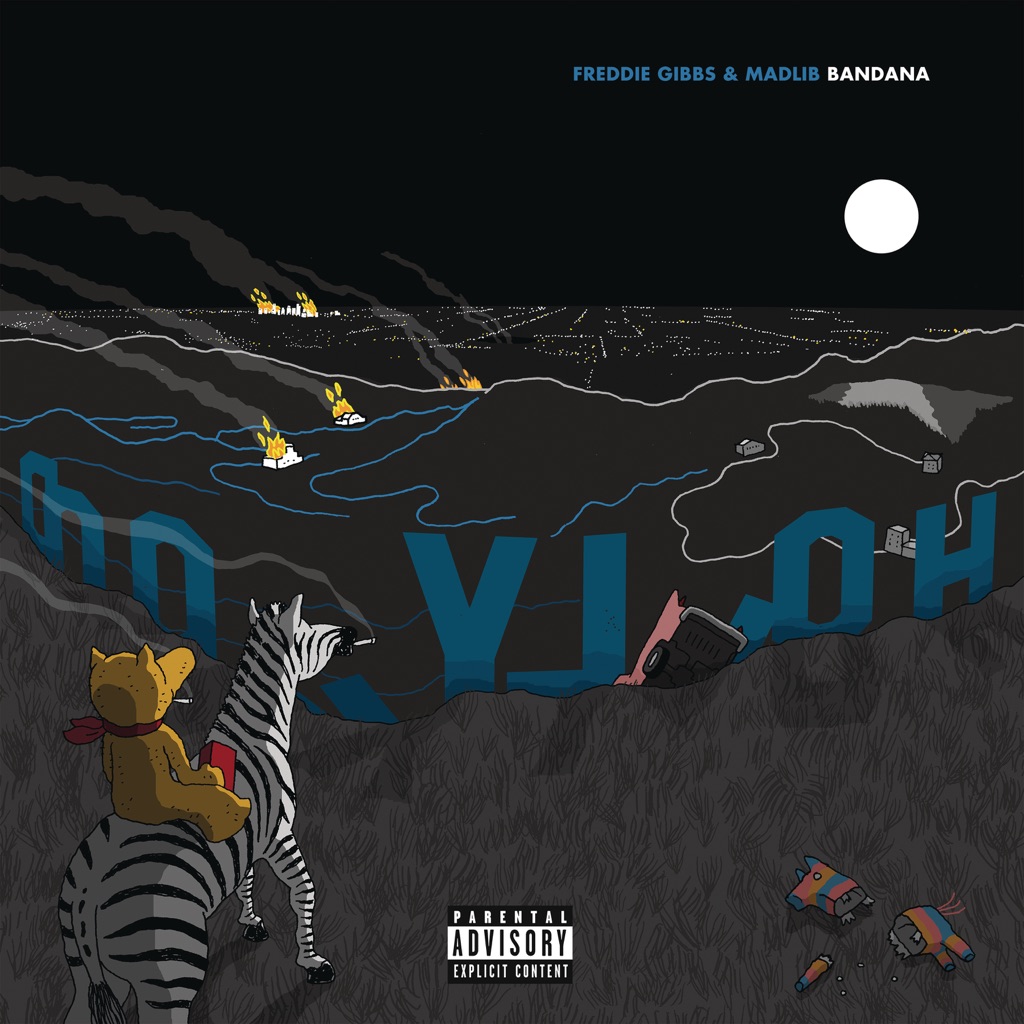

An eccentric like Madlib and a straightforward guy like Freddie Gibbs—how could it possibly work? If 2014’s *Piñata* proved that the pairing—offbeat producer, no-frills street rapper—sounded better and more natural than it looked on paper, *Bandana* proves *Piñata* wasn’t a fluke. The common ground is approachability: Even at their most cinematic (the noisy soul of “Flat Tummy Tea,” the horror-movie trap of “Half Manne Half Cocaine”), Madlib’s beats remain funny, strange, decidedly at human scale, while Gibbs prefers to keep things so real he barely uses metaphor. In other words, it’s remarkable music made by artists who never pretend to be anything other than ordinary. And even when the guest spots are good (Yasiin Bey and Black Thought on “Education” especially), the core of the album is the chemistry between Gibbs and Madlib: vivid, dreamy, serious, and just a little supernatural.

It was on a mountainside in Cumbria that the first whispers of Cate Le Bon’s fifth studio album poked their buds above the earth. “There’s a strange romanticism to going a little bit crazy and playing the piano to yourself and singing into the night,” she says, recounting the year living solitarily in the Lake District which gave way to Reward. By day, ever the polymath, Le Bon painstakingly learnt to make solid wood tables, stools and chairs from scratch; by night she looked to a second-hand Meers — the first piano she had ever owned —for company, “windows closed to absolutely everyone”, and accidentally poured her heart out. The result is an album every bit as stylistically varied, surrealistically-inclined and tactile as those in the enduring outsider’s back catalogue, but one that is also intensely introspective and profound; her most personal to date. This sense of privacy maintained throughout is helped by the various landscapes within which Reward took shape: Stinson Beach, LA, and Brooklyn via Cardiff and The Lakes. Recording at Panoramic House [Stinson Beach, CA], a residential studio on a mountain overlooking the ocean, afforded Le Bon the ability to preserve the remoteness she had captured during the writing of Reward in Staveley, Lake District. Over this extended period a cast of trusted and loved musicians joined Le Bon, Khouja and fellow co-producer Josiah Steinbrick — Stella Mozgawa (of Warpaint) on drums and percussion; Stephen Black (aka Sweet Baboo) on bass and saxophone and longtime collaborators Huw Evans (aka H.Hawkline) and Josh Klinghoffer on guitars — and were added to the album, “one by one, one on one”. The fact that these collaborators have appeared variously on Le Bon’s previous outputs no doubt goes some way to aid the preservation of a signature sound despite a relatively drastic change in approach. Be it on her more minimalist, acoustic-leaning 2009 debut album Me Oh My or critically acclaimed, liquid-riffed 2013 LP Mug Museum as well as 2016s Crab Day, Cate Le Bon’s solo work — and indeed also her production work, such as that carried out on recent Deerhunter album Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? (4AD, January 2019) — has always resisted pigeonholing, walking the tightrope between krautrock aloofness and heartbreaking tenderness; deadpan served with a twinkle in the eye, a flick of the fringe and a lick of the Telecaster. The multifaceted nature of Le Bon’s art — its ability to take on multiple meanings and hold motivations which are not immediately obvious — is evident right down to the album’s very name. “People hear the word ‘reward’ and they think that it’s a positive word” says Le Bon, “and to me it’s quite a sinister word in that it depends on the relationship between the giver and the receiver. I feel like it’s really indicative of the times we’re living in where words are used as slogans, and everything is slowly losing its meaning.” The record, then, signals a scrambling to hold onto meaning; it is a warning against lazy comparisons and face values. It is a sentiment nicely summed up by the furniture-making musician as she advises: “Always keep your hand behind the chisel.”

Calling an album *All My Heroes Are Cornballs* reads immediately as a brilliant indictment of celebrity culture, but what about when said whistleblower exists—to a steadily increasing number of fans—as a hero himself? “Some people *might* see me as a hero, and I *might* be a cornball to some people,” JPEGMAFIA tells Apple Music. “It can be turned on the person who created it. I’m not infallible or trying to say I\'m not a cornball. I\'m just saying, *all my heroes are cornballs*.” The album and declaration come just a year after *Veteran*, the project that brought the Brooklyn-born Baltimore MC and producer his most visibility. So what does Peggy do with all of the eyes and ears he now has at his disposal? The same thing he’s done from the beginning of his music-making career: tell people about themselves, whether they’re ready to hear it or not. Read on as JPEGMAFIA talks Apple Music through some of *All My Heroes Are Cornballs*\' more provocative selections. **“Beta Male Strategies”** “Going back to the title \[of the album\], I\'m letting you know off the bat, I\'m a false prophet. Don\'t get your hopes up, because everybody\'s human. I might put a MAGA hat on one day. It\'s unlikely, but you don\'t know, so it\'s just like, \'I\'m a false prophet/Bringin’ white folks this new religion/My fans need new addictions.’ It\'s not like I\'m the first artist to struggle with notoriety or anything like that. I\'m just framing it through my lens. I\'ve been underground and poor for years, so this is hilarious to me.\" **“Grimy Waifu”** \"‘Grimy Waifu’ is actually about a gun. They probably changed it now because the times are different, but \[when I was in the military\] they framed it like, ‘This is your gun. This is your girl. You gotta sleep with her…’ In the female squad, they probably did the opposite: ‘This is your n\*gga. Bring your n\*gga to bed.’ It\'s framed like it\'s a love song, but it\'s a song about me and my rifle.” **“PRONE!”** “The intention behind ‘PRONE!’ was to make a punk song with no instruments. This is a song that\'s made completely digitally. I feel like people in other genres, specifically rock—I go back to rock a lot because rock spends a lot of time trashing rap—a lot of people in rock had this idea that rappers aren\'t talented. In my opinion, we\'re fucking better than them. We\'re better writers, we think deeper, our concepts are harder—rap evolves faster and at a higher rate than any other genre. The only difference is rap has a bunch of n\*ggas doing it and rock has a bunch of white boys doing it. I made this song just to be like, \'I can do what you do and I don\'t even have to learn how to play drums. I\'m in here playing with my hands, bitch! And I can still do this shit.\'” **“All My Heroes Are Cornballs”** “Structurally it makes no sense, but thematically it’s the most straightforward song on here: rapping about the idea that the people we’re supposed to look up to are corny as shit. I feel like this one sums up everything, because I’m not doing anything weird vocally, I’m singing and then I’m rapping, but the execution of it doesn’t make sense: It starts off one way and I’m singing, and there’s like a long-ass hook where I don’t actually say anything and then there’s like a verse, and then the other hook that comes in is different, and then the end is like my homie ordering a bacon smokehouse meal. I came very close to cutting it, actually.” **“Thot Tactics”** “I actually wrote the rap first and that melody I had, and when I was writing the song, I would hum that melody over the part where it is now, and in the back of my head I told myself I’m gonna write something to that later, but I just sat down one day and I was like, nah, n\*gga, this is it! This is the song. I can’t hire En Vogue to do this, I gotta do it myself. I’m a DIY n\*gga. I want some shit done, I do it my muthafuckin’ self!” **“BasicBitchTearGas”** “I always told myself that one day I’d do a cover of ‘No Scrubs,’ and I just wanted to make that a reality. Bucket-list-type shit. I love this song, man. It’s one of the best songs ever written. And I really like recontextualizing songs that mean a lot to people, like pop music, because it exposes the reality of these songs. That these songs are *excellent*—regardless of how popular they are and regardless of the narrative that’s been built around some of these songs, these are excellently written, beautiful songs, and I wanna take time to appreciate them.” **“Papi I Missed U”** “I wanted to put something on record that was completely, exactly how the fuck I felt. There was no trolling, this is how I feel. And I want people to hear that and I want people to know that there\'s no fucking answer \[for it\]. I don\'t like you and there\'s nothing you can do about it. That\'s how they made my black ass feel for my whole fucking life. So when I say some shit like \'I hate old white n\*ggas, I\'m prejudiced…\' What now? I said it, I meant it, it is what it is. They don\'t give a fuck about our feelings, I don\'t give a fuck about theirs. It\'s returning all the shit they always give to me and give to black people. All this shit these racist types give to people of color, I\'m giving it right back to them and I\'m watching them scatter because they can\'t fucking take it.”

All tracks produced, written, mixed and mastered by JPEGMAFIA "Rap Grow Old & Die" contains additional production from Vegyn Album Artwork Design by Alec Marchant Recorded alone @ a space for me This album is really a thank you to my fans tbh. I started and finished it In 2018, mixed and mastered it in 2019 right after the Vince tour. I don’t usually work on something right after I release a project. But Veteran was the first time in my life I worked hard on something, and it was reciprocated back to me. So I wanted thank my people. And make an album that I put my my whole body into, as in all of me. All sides of Me baby. Not just a few. This the most ME album I’ve ever made in my life, Im trying to give y’all niggas a warm album you can live in and take a nap in maybe start a family and buy some Apple Jacks to. I’ve removed restrictions from my head and freed myself of doubt musically. I would have removed half this shit before but naw fuck it. Y’all catching every bit of this basic bitch tear gas. This is me, all me, in full form nigga, and this formless piece of audio is my punk musical . I hope it disappoints every last one of u. 💕💕

Look past its futurist textures and careful obfuscations, and there’s something deeply human about FKA twigs’ 21st-century R&B. On her second full-length, the 31-year-old British singer-songwriter connects our current climate to that of Mary Magdalene, a healer whose close personal relationship with Christ brought her scorn from those who would ultimately write her story: men. “I\'m of a generation that was brought up without options in love,” she tells Apple Music. “I was told that as a woman, I should be looked after. It\'s not whether I choose somebody, but whether somebody chooses me.” Written and produced by twigs, with major contributions from Nicolas Jaar, *MAGDALENE* is a feminist meditation on the ways in which we relate to one another and ourselves—emotionally, sexually, universally—set to sounds that are at once modern and ancient. “Now it’s like, ‘Can you stand up in my holy terrain?’” she says, referencing the titular lyric from her mid-album collaboration with Future. “‘How are we going to be equals in this? Spiritually, am I growing? Do you make me want to be a better person?’ I’m definitely still figuring it out.” Here, she walks us through the album track by track. **thousand eyes** “All the songs I write are autobiographical. Anyone that\'s been in a relationship for a long time, you\'re meshed together. But unmeshing is painful, because you have the same friends or your families know each other. No matter who you are, the idea of leaving is not only a heart trauma, but it\'s also a social trauma, because all of a sudden, you don\'t all go to that pub that you went to together. The line \[\'If I walk out the door/A thousand eyes\'\] is a reference to that. At the time, I was listening to a lot of Gregorian music. I’d started really getting into medieval chords before that, and I\'d found some musicians that play medieval music and done a couple sessions with them. Even on \[2014\'s\] *LP1*, I had ‘Closer,’ which is essentially a hymn. I spent a lot of time in choir as a child and I went to Sunday school, so it’s part of who I am at this stage.” **home with you** “I find things like that interesting in the studio, just to play around and bring together two completely different genres—like Elton John chords and a hip-hop riff. That’s what ‘home with you’ was for me: It’s a ballad and it\'s sad, but then it\'s a bop as well, even though it doesn\'t quite ever give you what you need. It’s about feeling pulled in all directions: as a daughter, or as a friend, or as a girlfriend, or as a lover. Everyone wanting a piece of you, but not expressing it properly, so you feel like you\'re not meeting the mark.” **sad day** “It’s like, ‘Will you take another chance with me? Can we escape the mundane? Can we escape the cyclical motion of life and be in love together and try something that\'s dangerous and exhilarating? Yeah, I know I’ve made you sad before, but will you give me another chance?\' I wrote this song with benny blanco and Koreless. I love to set myself challenges, and it was really exciting to me, the challenge of retaining my sound while working with a really broad group of people. I was lucky working with Benny, in the fact that he creates an environment where, as an artist, you feel really comfortable to be yourself. To me, that\'s almost the old-school definition of a producer: They don\'t have to be all up in your grill, telling you what to do. They just need to lay a really beautiful, fertile soil, so that you can grow to be the best you in the moment.” **holy terrain** “I’m saying that I want to find a man that can stand up next to me, in all of my brilliance, and not feel intimidated. To me, Future’s saying, ‘Hey, I fucked up. I filled you with poison. I’ve done things to make you jealous. Can you heal me? Can you tell me how to be a better man? I need the guidance, of a woman, to show me how to do that.’ I don\'t think that there are many rappers that can go there, and just put their cards on the table like that. I didn\'t know 100%, once I met Future, that it would be right. But we spoke on the phone and I played him the album and I told him what it was about: ‘It’s a very female-positive, femme-positive record.’ And he was just like, ‘Yeah. Say no more. I\'ve got this.’ And he did. He crushed it. To have somebody who\'s got patriarchal energy come through and say that, wanting to stand up and be there for a woman, wanting to have a woman that\'s an equal—that\'s real.” **mary magdalene** “Let’s just imagine for one second: Say Jesus and Mary Magdalene are really close, they\'re together all the time. She\'s his right-hand woman, she’s his confidante, she\'s healing people with him and a mystic in her own right. So, at that point, any man and woman that are spending that much time together, they\'re likely to be what? Lovers. Okay, cool. So, if Mary had Jesus\' children, that basically debunks the whole of history. Now, I\'m not saying that happened. What I\'m saying is that the idea of people thinking that might happen is potentially really dangerous. It’s easier to call her a whore, because as soon as you call a woman a whore, it devalues her. I see her as Jesus Christ\'s equal. She’s a male projection and, I think, the beginning of the patriarchy taking control of the narrative of women. Any woman that\'s done anything can be subject to that; I’ve been subject to that. It felt like an apt time to be talking about it.” **fallen alien** “When you\'re with someone, and they\'re sleeping, and you look at them, and you just think, \'No.\' For me, it’s that line, \[\'When the lights are on, I know you/When you fall asleep, I’ll kick you down/By the way you fell, I know you/Now you’re on your knees\'\]. You\'re just so sick of somebody\'s bullshit, you\'re just taking it all day, and then you\'re in bed next to them, and you\'re just like, ‘I can\'t take this anymore.’” **mirrored heart** “People always say, ‘Whoever you\'re with, they should be a reflection of yourself.’ So, if you\'re looking at someone and you think, ‘You\'re a shitbag,’ then you have to think about why it was that person, at that time, and what\'s connecting you both. What is the reflection? For others that have found a love that is a true reflection of themselves, they just remind me that I don\'t have that, a mirrored heart.” **daybed** “Have you ever forgotten how to spell a really simple word? To me, depression\'s a bit like that: Everything\'s quite abstract, and even slightly dizzy, but not in a happy way. It\'s like a very slow circus. Suddenly the fruit flies seem friendly, everything in the room just starts having a different meaning and you even have a different relationship with the way the sofa cushions smell. \[Masturbation\] is something to raise your endorphins, isn\'t it? It’s either that or try and go to the gym, or try and eat something good. You almost can\'t put it into words, but we\'ve all been there. I sing, \'Active are my fingers/Faux, my cunnilingus\': You\'re imagining someone going down on you, but they\'re actually not. You open your eyes, and you\'re just there, still on your sofa, still watching daytime TV.” **cellophane** “It\'s just raw, isn\'t it? It didn\'t need a thing. The vocal take that\'s on the record is the demo take. I had a Lyft arrive outside the studio and I’d just started playing the piano chords. I was like, ‘Hey, can you just give me like 20, 25 minutes?’ And I recorded it as is. I remember feeling like I wanted to cry, but I just didn\'t feel like it was that suitable to cry at a studio session. I often want everything to be really intricate and gilded, and I want to chip away at everything, and sculpt it, and mold it, and add layers. The thing I\'ve learned on *MAGDALENE* is that you don\'t need to do that all the time, and just because you can do something, it doesn\'t mean you should. That\'s been a real growing experience for me—as a musician, as a producer, as a singer, even as a dancer. Something in its most simple form is beautiful.”

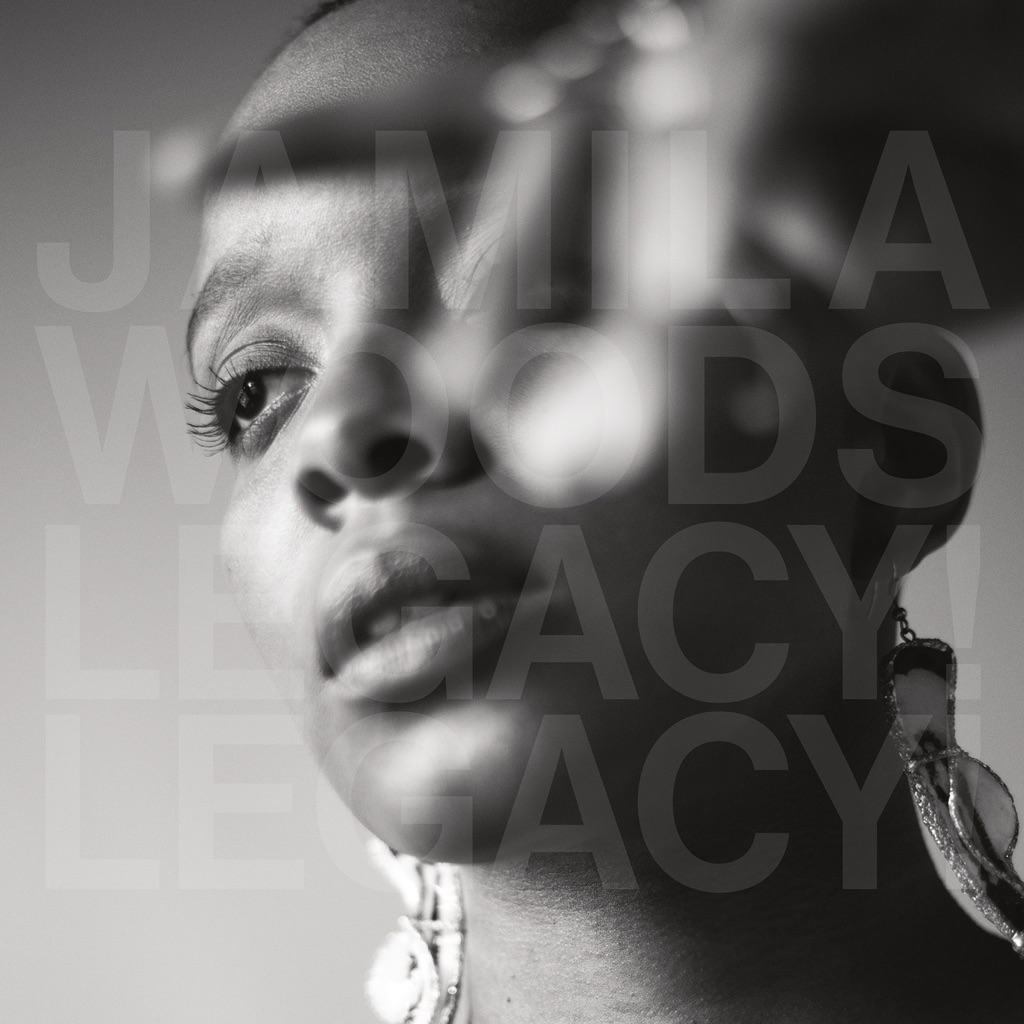

There’s nothing all that subtle about Jamila Woods naming each of these all-caps tracks after a notable person of color. Still, that’s the point with *LEGACY! LEGACY!*—homage as overt as it is original. True to her own revolutionary spirit, the Chicago native takes this influential baker’s dozen of songs and masterfully transmutes their power for her purposes, delivering an engrossingly personal and deftly poetic follow-up to her formidable 2016 breakthrough *HEAVN*. She draws on African American icons like Miles Davis and Eartha Kitt as she coos and commands through each namesake cut, sparking flames for the bluesy rap groove of “MUDDY” and giving flowers to a legend on the electro-laced funk of “OCTAVIA.”

In the clip of an older Eartha Kitt that everyone kicks around the internet, her cheekbones are still as pronounced as many would remember them from her glory days on Broadway, and her eyes are still piercing and inviting. She sips from a metal cup. The wind blows the flowers behind her until those flowers crane their stems toward her face, and the petals tilt upward, forcing out a smile. A dog barks in the background. In the best part of the clip, Kitt throws her head back and feigns a large, sky-rattling laugh upon being asked by her interviewer whether or not she’d compromise parts of herself if a man came into her life. When the laugh dies down, Kitt insists on the same, rhetorical statement. “Compromise!?!?” she flings. “For what?” She repeats “For what?” until it grows more fierce, more unanswerable. Until it holds the very answer itself. On the hook to the song “Eartha,” Jamila Woods sings “I don’t want to compromise / can we make it through the night” and as an album, Legacy! Legacy! stakes itself on the uncompromising nature of its creator, and the histories honored within its many layers. There is a lot of talk about black people in America and lineage, and who will tell the stories of our ancestors and their ancestors and the ones before them. But there is significantly less talk about the actions taken to uphold that lineage in a country obsessed with forgetting. There are hands who built the corners of ourselves we love most, and it is good to shout something sweet at those hands from time to time. Woods, a Chicago-born poet, organizer, and consistent glory merchant, seeks to honor black people first, always. And so, Legacy! Legacy! A song for Zora! Zora, who gave so much to a culture before she died alone and longing. A song for Octavia and her huge and savage conscience! A song for Miles! One for Jean-Michel and one for my man Jimmy Baldwin! More than just giving the song titles the names of historical black and brown icons of literature, art, and music, Jamila Woods builds a sonic and lyrical monument to the various modes of how these icons tried to push beyond the margins a country had assigned to them. On “Sun Ra,” Woods sings “I just gotta get away from this earth, man / this marble was doomed from the start” and that type of dreaming and vision honors not only the legacy of Sun Ra, but the idea that there is a better future, and in it, there will still be black people. Jamila Woods has a voice and lyrical sensibility that transcends generations, and so it makes sense to have this lush and layered album that bounces seamlessly from one sonic aesthetic to another. This was the case on 2016’s HEAVN, which found Woods hopeful and exploratory, looking along the edges resilience and exhaustion for some measures of joy. Legacy! Legacy! is the logical conclusion to that looking. From the airy boom-bap of “Giovanni” to the psychedelic flourishes of “Sonia,” the instrument which ties the musical threads together is the ability of Woods to find her pockets in the waves of instrumentation, stretching syllables and vowels over the harmony of noise until each puzzle piece has a home. The whimsical and malleable nature of sonic delights also grants a path for collaborators to flourish: the sparkling flows of Nitty Scott on “Sonia” and Saba on “Basquiat,” or the bloom of Nico Segal’s horns on “Baldwin.” Soul music did not just appear in America, and soul does not just mean music. Rather, soul is what gold can be dug from the depths of ruin, and refashioned by those who have true vision. True soul lives in the pages of a worn novel that no one talks about anymore, or a painting that sits in a gallery for a while but then in an attic forever. Soul is all the things a country tries to force itself into forgetting. Soul is all of those things come back to claim what is theirs. Jamila Woods is a singular soul singer who, in voice, holds the rhetorical demand. The knowing that there is no compromise for someone with vision this endless. That the revolution must take many forms, and it sometimes starts with songs like these. Songs that feel like the sun on your face and the wind pushing flowers against your back while you kick your head to the heavens and laugh at how foolish the world seems.

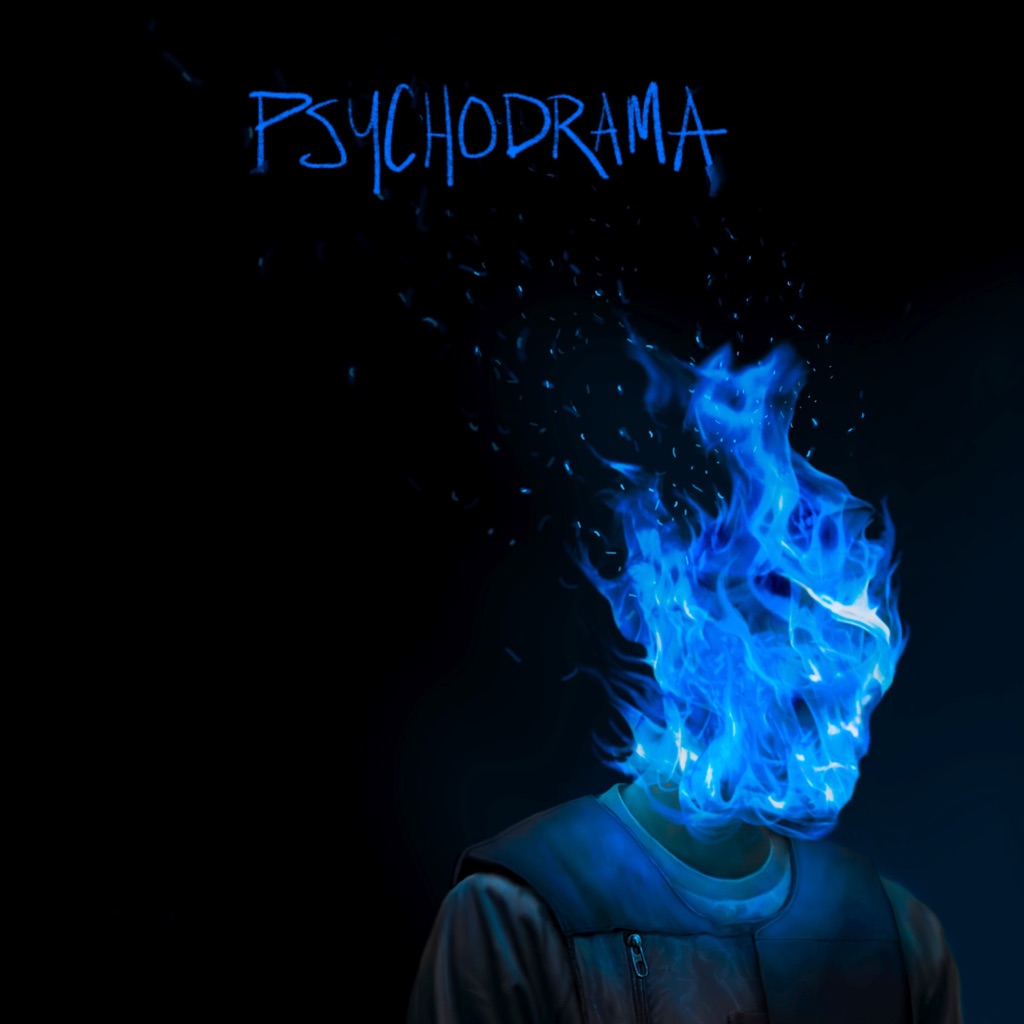

The more music Dave makes, the more out of step his prosaic stage name seems. The richness and daring of his songwriting has already been granted an Ivor Novello Award—for “Question Time,” 2017’s searing address to British politicians—and on his debut album he gets deeper, bolder, and more ambitious. Pitched as excerpts from a year-long course of therapy, these 11 songs show the South Londoner examining the human condition and his own complex wiring. Confession and self-reflection may be nothing new in rap, but they’ve rarely been done with such skill and imagination. Dave’s riveting and poetic at all times, documenting his experience as a young British black man (“Black”) and pulling back the curtain on the realities of fame (“Environment”). With a literary sense of detail and drama, “Lesley”—a cautionary, 11-minute account of abuse and tragedy—is as much a short story as a song: “Touched her destination/Way faster than the cab driver\'s estimation/She put the key in the door/She couldn\'t believe what she see on the floor.” His words are carried by equally stirring music. Strings, harps, and the aching melodies of Dave’s own piano-playing mingle with trap beats and brooding bass in incisive expressions of pain and stress, as well as flashes of optimism and triumph. It may be drawn from an intensely personal place, but *Psychodrama* promises to have a much broader impact, setting dizzying new standards for UK rap.

Big Thief has been known to tackle intensely personal themes: family histories, deaths, isolation, fear. Here, on their expansive third album, the New York indie rock band shifts its gaze outward and into the unknown. \"Just like a bad dream/You\'ll disappear,” frontwoman Adrianne Lenker coos on the title track. \"And I imagine you/Taking me outta here.” Through gentle strums and hushed, tumbling melodies, the band wonders: Who\'s out there? Are they as strange as we are? What’s real? The second F in the album’s title stands for “friend”—an optimistic embrace of all things unfamiliar or alien. Their songs—comforting, eerie, folksy, magnificent—do the same.

U.F.O.F., F standing for ‘Friend’, is the name of the highly anticipated third record by Big Thief, set to be released on 3rd May 2019 via 4AD. U.F.O.F. was recorded in rural western Washington at Bear Creek Studios. In a large cabin-like room, the band set up their gear to track live with engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who was also behind their previous albums. Having already lived these songs on tour, they were relaxed and ready to experiment. The raw material came quickly. Some songs were written only hours before recording and stretched out instantly, first take, vocals and all. “Making friends with the unknown… All my songs are about this,” says Lenker; “If the nature of life is change and impermanence, I’d rather be uncomfortably awake in that truth than lost in denial.”

The title of this group’s second album may suggest a mystical journey, but what you hear across these nine tracks is a thrilling and direct collaboration that speaks to the mastery of the individual members: London jazz supremo Shabaka Hutchings delivers commanding saxophone parts, keyboardist Dan Leavers supplies immersive electronic textures, and drummer Max Hallett provides a welter of galvanizing rhythms. The trio records under pseudonyms—“King Shabaka,” “Danalogue,” and “Betamax” respectively—and that fantastical edge is also part of their music, which looks to update the cosmic jazz legacy of 1970s outliers such as Alice Coltrane and Sun Ra. With the only vocals a spoken-word poem on the grinding “Blood of the Past,” the lead is easily taken by Hutchings’ urgent riffs. Tracks such as “Summon the Fire” have a delirious velocity that builds and peaks repeatedly, while the skittering beat on “Super Zodiac” imports the production techniques of Britain’s grime scene. There’s a science-fiction sheen to slower jams like “Astral Flying,” which makes sense—this is evocative time-travel music, after all. Even as you pick out the reference points, which also include drum \'n\' bass and psychedelic rock, they all interlock to chart a sound for the future.

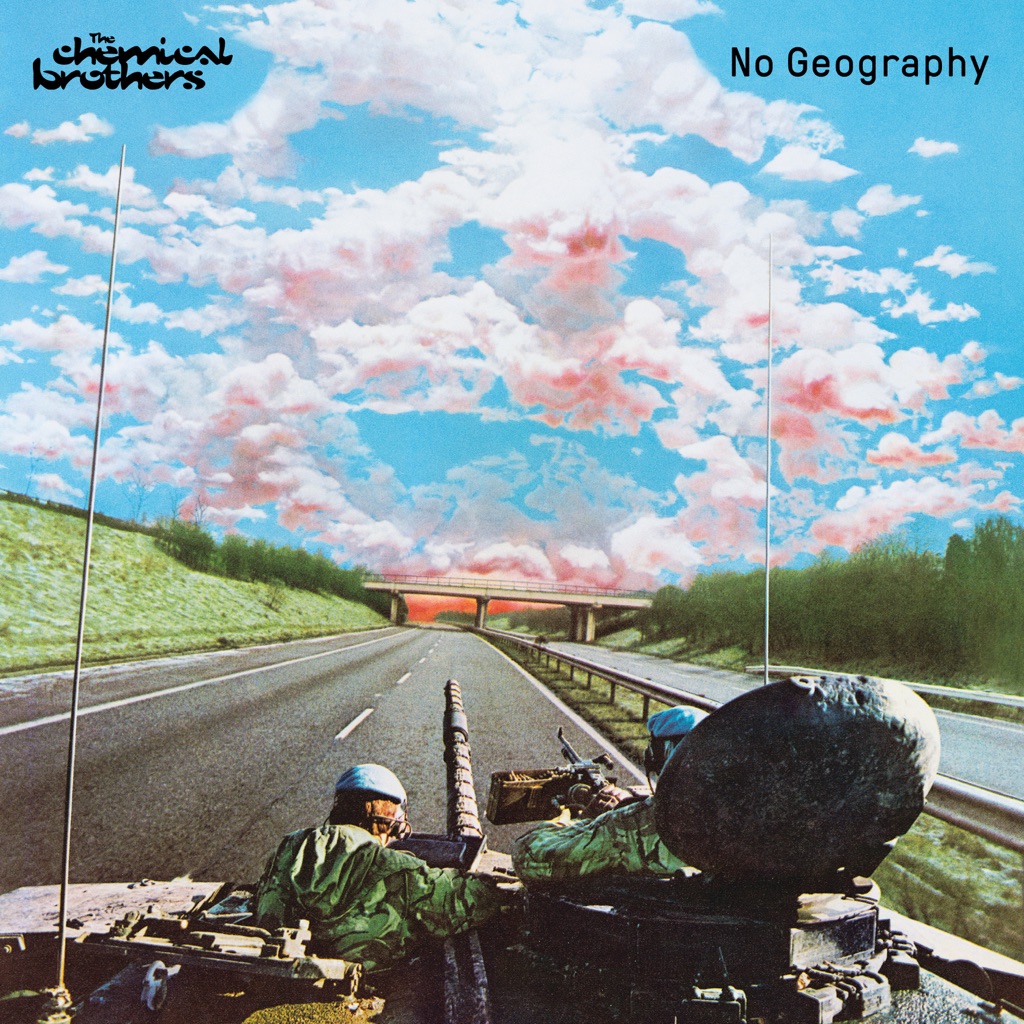

If *No Geography* is The Chemical Brothers\' most daring album in 20 years—and it is—that’s partly due to Tom Rowlands and Ed Simons tapping back into the mid-’90s, a time when they were helping to radically redefine the possibilities for UK dance music. To sow that spirit of experimentalism into their ninth album, the pair exhumed the old samplers they used to make their first two albums. “I set up a corner of my studio that was ‘The 1997 Corner,’” Tom tells Apple Music. “It was very rudimentary, the sort of thing that I’d have set up in my bedroom a long time ago. There’s a particular sound in these old samplers, and their limitations spur you being more creative in how you use samples and throw things together.” Another inspiring throwback was to play unfinished music in their live sets, allowing the songs to evolve and change on stage, as they had done while making 1995’s *Exit Planet Dust* and *Dig Your Own Hole* in 1997. The result is uplifting, aggressive, and contemplative, meshing breakbeats, samples, and multiple shades of dance music with a keen understanding of psychedelia and melody. Here, Tom takes us through the album track by track. **“Eve of Destruction”** “I saw \[Norwegian alt-pop singer-songwriter\] Aurora on TV, playing at Glastonbury, and I was blown away by the power of her voice and the raw feel she had. She came to the studio and we had such an inspiring time. She was so open to ideas and so full of ideas. She came up with Eve of Destruction as a character, this goddess of destruction. It starts with a discordant voice, but as the track grows, it turns into celebration. The response to this foreboding, forbidding nature of the lyric is to cut loose, to come together, go out and find a friend and be with other like-minded people.” **“Bango”** “Aurora’s response to playing her bits of music was so unexpected, brilliant, and inspiring. \[For ‘Bango’\] I’d play her something and she’d come back and with angular words and ideas about unbalanced relationship dynamics and gods bringing thunder upon you. That\'s the excitement of collaborating with someone—arriving at something that neither of you could have thought of on your own.” **“No Geography”** “The vocal sample is from a poem by Michael Brownstein, a ’70s New York poet. They did this series called the Dial-A-Poem Poets where you could phone up and have poets read to you. That bit seems to be dealing with the idea that the physical geography between people is not a barrier to their connection. But, yeah, on a bigger scale it’s saying something about people being connected and how we all share something together. It’s recognizing that we are codependent on each other, I suppose.” **“Got to Keep On”** “You’ve got the sparkly drums and the ‘Got to keep on making me high’ sample \[from Peter Brown’s ‘Dance with Me’\] and then it has this strange, off-kilter moment in the middle, which was a late night in the studio making everything as deranged as it can be—everything feeding back and all the machines squealing. It’s too much, basically. And when it’s too much, it’s just enough. And then it kind of resolves out and the bells come in. We love to have these really intense kind of psychedelic moments in our music and then it resolves into a joy—you’ve come through it, almost. It’s something that feels very natural to us.” **“Gravity Drops”** “This is the first breathing moment of the record, really. It’s got heavy beats but the music is moving around, and then you’ve got very full-on *d-d-d-drong* bits. It all comes from setting up the studio to play it live—we set up lots of instruments and processors so we can play it as a kind of jam and then see where we get to. This is definitely made of trying to have those sections where it just freaks us out. And then we go, ‘Yes, it’s freaked us out.’” **“The Universe Sent Me”** “Aurora really made this by coming up with these amazing images. Sonics-wise, there are a lot of ideas and a lot of movement. There are moments where it almost feels that whole thing has gone too far, the way it builds and then you’re back down. It’s a rolling psychedelic journey, for want of a better word.” **“We’ve Got to Try”** “This reminds me of records that we would play at \[legendary London club night\] The Social when we first started. We’d play quite a lot of soul next to mad acid records. When we were making this track, it really reminded me of that—this idea that we were trying to reach for but never really realized in our own music. If this song had arrived in our record bags, we’d have gone, ‘Wow! This is the sound of what we want to play.’” “Free Yourself” “This samples another Dial-A-Poem poet, Diane di Prima. We loved hearing that vocal in a nightclub. It was exciting to build a new context for that song, to have a new meaning. We played it live a lot in 2018, and that really fed into how the final thing turned out. It’s also got that ‘Waaaaaaaaaaaaaah’ kind of noise. We just like instant delirium noises.” **“MAH”** “Once, we would probably have felt this was too big a sample to use \[the line \'I’m mad as hell and I ain’t going to take it no more\' from El Coco’s ‘I’m Mad as Hell’\]. But the excitement of playing it live and the release of the music after the vocal was an amazing moment. Even though we\'re not the kind of artists who will be very explicit in what they\'re feeling, the record was made in a time when, every day, you had constant national discussion and arguments going on. Even though we’re speaking through a sample, another sentiment from another time, when we made the song and put this whole feeling together, it was like, ‘Yeah, that somehow relates to how I\'m feeling today.’” **“Catch Me I’m Falling”** “One of the sampled vocals is by Stephanie Dosen–we worked with her on *Further* and the score for *Hanna*–from a Snowbird track, which is her and Simon Raymonde, who used to be in the Cocteau Twins. The other is from \[Emmanuel Laskey’s\] ‘A Letter from Vietnam,’ this very emotive song from 1968. Stephanie’s singing in a different way—in a different room, in a different time—but the music we\'ve written somehow brings these two disparate things together and makes new sense out of them. But it only makes sense if the thing at the end of it is something you want to listen to, something that moves you.”

hey i'm j from glass beach, i used to make music under the name “casio dad”. this album began with demos written in 2015 & 2016 when i first moved to los angeles and spent almost a year living on my friend's couch. i met jonas and william on facebook after they heard the casio dad album on their college radio station in minnesota and we eventually ended up moving into an apartment together in north hollywood. after showing them the new demos i had been writing, jonas and william decided to join the band, playing bass and drums respectively, and we spent the next three years refining the demos into songs. thematically this album differs a lot from "he's not with us anymore", rather than focusing so much on internal feelings, this album looks outside, in an attempt to capture the external world in all its good, all its bad, and especially all its confusion. it revels in the lack of a focused narrative, portraying multiple perspectives at once and changing moods on a whim. the sound of glass beach is a fusion of our diverse range of influences including 1960s jazz, new wave, early synthesizer music, and emo, but all presented with the harshness and irreverence of punk music. we embrace the trend towards genrelessness caused by the increasing irrelevance of record labels and democratization of music brought about by the internet and enjoy playing with musical boundaries even to the point of absurdity.

W. H. Lung’s arrival at their debut album has been less conventional than most. A trait shared with the music they make, which weaves between shimmering synth pop and the infectious grooves of 70’s Berlin. The band never had any intention of playing live when forming, aiming instead to be a primarily studio-based project. That approach was challenged when they released their debut 10” ('Inspiration!/Nothing Is') in 2017, which meant that they were quickly in demand. Booking requests started to flood in and W. H. Lung found themselves cutting their teeth on festival stages that summer. Though whilst some new bands may have let that interest change the course of the project, W. H. Lung stayed true to their original reticence and worked mainly as a studio band with their formidable live shows kept sporadic. W. H. Lung have allowed this album to naturally gestate over the course of two years . The result is a remarkably considered debut - the production is crisp and pristine but not over-polished, the synths and electronics radiate and hum with a golden aura and the vocals weave between tender delivery and forceful eruptions. There is a palpable energy to the songs, as experienced in 10 glorious minutes of opening statement 'Simpatico People'. “I think it’s important to erase the distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture,” states Joseph E. This colliding of worlds not only exists in the potent mix between whip-smart arrangements, lyrics and seamlessly danceable music but also in the fact that they are named after a cash and carry in Manchester. As Tom P. explains, “I thought it was funny juxtaposing those kind of austere associations with W. H. Auden and other initialed poets, writers, artists, etc. with the fact that it’s really just a Chinese supermarket.”

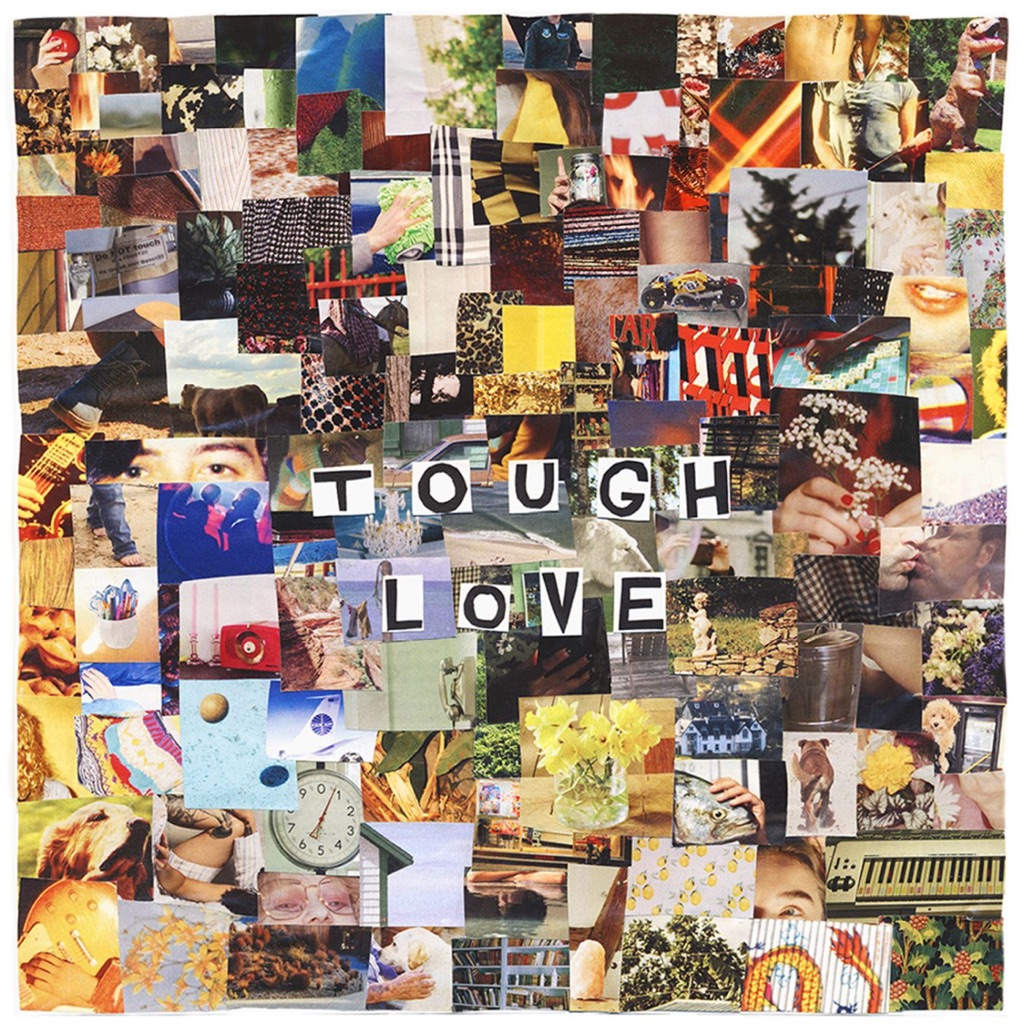

The debut album from Erin Anne, Tough Love is an unruly yet elegant collage of all the elements that make up her musical vocabulary: wildly shredded riffs and lo-fi acoustic ramblings, punk-rock energy and folky austerity, new-wave whimsy and high-flown pop theatrics. With a narrative voice at turns thoughtful and rebellious, confrontational and shy, the L.A.-based singer/songwriter spins her lyrics from such divergent sources as formative queer texts and her own moon-phase-specific dream journal, ultimately presenting a body of work that bravely documents the slow and strange process of becoming yourself.

Michael Kiwanuka never seemed the type to self-title an album. He certainly wasn’t expected to double down on such apparent self-assurance by commissioning a kingly portrait of himself as the cover art. After all, this is the singer-songwriter who was invited to join Kanye West’s *Yeezus* sessions but eventually snuck wordlessly out, suffering impostor syndrome. That sense of self-doubt shadowed him even before his 2012 debut *Home Again* collected a Mercury Prize nomination. “It’s an irrational thought, but I’ve always had it,” he tells Apple Music. “It keeps you on your toes, but it was also frustrating me. I was like, ‘I just want to be able to do this without worrying so much and just be confident in who I am as an artist.’” Notions of identity also got him thinking about how performers create personas—onstage or on social media—that obscure their true selves, inspiring him to call his third album *KIWANUKA* in an act of what he calls “anti-alter-ego.” “It’s almost a statement to myself,” he says. “I want to be able to say, ‘This is me, rain or shine.’ People might like it, people might not, it’s OK. At least people know who I am.” Kiwanuka was already known as a gifted singer and songwriter, but *KIWANUKA* reveals new standards of invention and ambition. With Danger Mouse and UK producer Inflo behind the boards—as they were on *Love & Hate* in 2016—these songs push his barrel-aged blend of soul and folk further into psychedelia, fuzz rock, and chamber pop. Here, he takes us through that journey song by song. **You Ain’t the Problem** “‘You Ain’t the Problem’ is a celebration, me loving humans. We forget how amazing we are. Social media’s part of this—all these filters hiding things that we think people won\'t like, things we think don\'t quite fit in. You start thinking this stuff about you is wrong and that you’ve got a problem being whatever you are and who you were born to be. I wanted to write a song saying, ‘You’re not the problem. You just have to continue being *you* more, go deeper within yourself.’ That’s where the magic comes—as opposed to cutting things away and trying to erode what really makes you.” **Rolling** “‘Rolling with the times, don’t be late.’ Everything’s about being an artist for me, I guess. I was trying to find my place still, but you can do things to make sure that you fit in or are keeping up with everything that’s happening—whether it’s posting stuff online or keeping up with the coolest records, knowing the right things. Or it could just be you’re in your mid-thirties, you haven’t got married or had kids yet, and people are like, ‘What?’ ‘Rolling with the times’ is like, go at your own pace. In my head, there was early Stooges records and French records like Serge Gainsbourg with the fuzz sounds. I wanted to make a song that sounded kind of crazy like that.” **I’ve Been Dazed** “Eddie Hazel from Funkadelic is my favorite guitar player. This has anthemic chords because he would always have really beautiful anthemic chords in the songs that he wrote. It just came out almost hymn-like. Lyrically, because it has this melancholy feel to it, I was singing about waking up from the nightmare of following someone else’s path or putting yourself down, low self-esteem—the things ‘You Ain\'t the Problem’ is defying. The feeling is, ‘Man, I\'ve been in this kind of nightmare, I just want to get out of it, I’m ready to go.’” **Piano Joint (This Kind of Love) \[Intro\]** “As a teenager, I’d just escape \[into some albums\], like I could teleport away from life and into that person’s world. I really wanted to have that feel with this record. It would be so vivid, there was no chance to get out of it, no gap in the songs—make it feel like one long piece. Some songs just flow into each other, but some needed interludes as passageways. This intro came when I was playing some bass and \[Inflo\] was playing some piano and I started singing my idea of a Marvin Gaye soul tune—a deep, dark, melancholic cut from one of his ’70s records. Then Danger Mouse had the idea, ‘Why don’t you pitch some of it down so it sounds different?’” **Piano Joint (This Kind of Love)** “I used to always love melancholy songs; the sadder it is, the happier I’d be afterwards. This was my moment to really exercise that part of me. Originally, it was going to be a piano ballad, and then I was like, ‘Why don’t we try playing some drums?’ Inflo’s a really good drummer, so I went in and played bass with him, and it sounded really good. I was thinking of that ’70s Gil Scott-Heron East Coast soul. Then we worked with this amazing string arranger, Rosie Danvers, who did almost all the strings on the last album. I said to her, ‘It’s my favorite song, just do something super beautiful.’ She just killed it.” **Another Human Being** “We were doing all the interludes and Danger Mouse had found loads of samples. This was a news report \[about the ’60s US civil rights sit-in protests\]. I remember thinking, ‘This sounds amazing, it goes into “Living in Denial” perfectly—it just changes that song.’ And, yeah, again, I’m ’70s-obsessed, but the ’60s and ’70s were so pivotal for young American black men and women, and it just gave a gravitas to the record. It goes to identity and something that resonates with me and my name and who I am. It gives me loads of confidence to continue to be myself.” **Living in Denial** “This is how me, Inflo, and Danger Mouse sound when we’re completely ourselves and properly linked together. No arguments, just let it happen, don’t think about it. I was trying to be a soul group—thinking of The Delfonics, The Isley Brothers, The Temptations, The Chambers Brothers. Again, the lyrics are that thing of seeking acceptance: You don’t need to seek it, just accept yourself and then whoever wants to hang with you will.” **Hero (Intro)** “‘Hero’ was the last song we completed. Once it started to sound good, I was sitting there with my acoustic, playing. We’d done the ‘Piano Joint’ intro and I was like, ‘Oh, we should pitch down this number as well and make it something that we really wouldn’t do with a straight rock ’n’ roll song.’” **Hero** “‘Hero’ was the hardest to come up with lyrics for. We had the music and melody for, like, two years. Any time I tried to touch it, I hated it—I couldn’t come up with anything. Then I was reading about Fred Hampton from the Black Panthers and I started thinking about all these people that get killed—or, like Hendrix, die an accidental death—who have so much to give or do so much in such a small time. I also love the thing where all these legends, Bowie and Bob Dylan, were creating larger-than-life personas that we were obsessed with. You didn’t really know who they were. That really made me sad, because I don’t disagree with it, but I know that’s not me. So, ‘Am I a hero?’ was also asking, ‘If I do that stuff, will I become this big artist that everyone respects?’—that ‘I’m not enough’ thing.” **Hard to Say Goodbye** “This is my love of Isaac Hayes and big orchestrations, lush strings, people like David Axelrod. Flo actually brought in this sample from a Nat King Cole song, just one chord, and we pitched it around, and then we replayed it with a 20-piece string orchestra packed into the studio. We had a double-bass cello, the whole works, and this really good piano player Kadeem \[Clarke\] who plays with Little Simz, and our friend Nathan \[Allen\] playing drums. That was pretty fun.” **Final Days** “At first, I didn’t know where this would fit on the record, like, ‘Man, this is cool, I just don’t *love*it.’ I wrote some lyrics and thought, ‘This is better, but it’s missing something.’ It always felt like space to me, so I said to Kennie \[Takahashi\], the engineer, ‘Are there any samples you can find of people in space?’ We found these astronauts about to crash, which is kind of dark, but it gave it this emotion it was missing. It gave me goosebumps. Later, we found out that it was a fake, some guys messing around in Italy in the ’60s for an art project or something.” **Interlude (Loving the People)** “‘Final Days’ was sounding amazing, but it needed to go somewhere else at the end. I had this melody on the Wurlitzer, and originally it was an instrumental bit that comes in for the end of ‘Final Days’ so that it ends somewhere completely different, like the spaceship’s landing at its destination. But I was like, ‘Let’s stretch it out. Let’s do more.’ Danger Mouse found this \[US congressman and civil rights leader\] John Lewis sample, and it sounded beautiful and moving over these chords, so we put it here.” **Solid Ground** “When everything gets stripped away—all the strings, all the sounds, all the interludes—I’m still just a dude that sits and plays a song on a guitar or piano. I felt like the album needed a glimpse of that. Rosie did a beautiful arrangement and then I finished it off—everyone was out somewhere, so I just played all the instruments, apart from drums and things like that. So, ‘Solid Ground’ is my little piece that I had from another place. Lyrically, it’s about finding the place where you feel comfortable.” **Light** “I just thought ‘Light’ was a nice dreamy piece to end the record with—a bit of light at the end of this massive journey. You end on this peaceful note, something positive. For me, light describes loads of things that are good—whether it’s obvious things like the light at the end of the tunnel or just a light feeling in my heart. The idea that the day’s coming—such a peaceful, exciting thing. We’re just always looking for it.” *All Apple Music subscribers using the latest version of Apple Music on iPhone, iPad, Mac, and Apple TV can listen to thousands of Dolby Atmos Music tracks using any headphones. When listening with compatible Apple or Beats headphones, Dolby Atmos Music will play back automatically when available for a song. For other headphones, go to Settings > Music > Audio and set the Dolby Atmos switch to “Always On.” You can also hear Dolby Atmos Music using the built-in speakers on compatible iPhones, iPads, MacBook Pros, and HomePods, or by connecting your Apple TV 4K to a compatible TV or AV receiver. Android is coming soon. AirPods, AirPods Pro, AirPods Max, BeatsX, Beats Solo3, Beats Studio3, Powerbeats3, Beats Flex, Powerbeats Pro, and Beats Solo Pro Works with iPhone 7 or later with the latest version of iOS; 12.9-inch iPad Pro (3rd generation or later), 11-inch iPad Pro, iPad (6th generation or later), iPad Air (3rd generation), and iPad mini (5th generation) with the latest version of iPadOS; and MacBook (2018 model and later).*

The title for Blonde Redhead vocalist Kazu Makino’s first solo album came when Makino learned of a club where men could go and get treated like children—a concept by turns private, eerie, liberating, and, if you surrender some pretenses, a little bit sweet. What follows is the kind of breathy experimental pop that conjures moods of almost unsettling intimacy, as close as a whisper and disjointed as a dream (“Meo,” “Adult Baby”). Even when Makino lets things lock into something a bit more straightforward (“Undo,” “Come Behind Me, So Good!”), the music maintains an intoxicating lack of balance, a sense of secrets disappearing under covers and behind corners. Featuring guest spots from Deerhoof drummer Greg Saunier and—on five of the album’s nine tracks—the venerated Japanese avant-pop composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, it’s a wholly unusual and uncommon album.

KAZU, Blonde Redhead vocalist and multi-instrumentalist Kazu Makino, intro her first solo LP Adult Baby, which will be released on her new imprint of the same name later this year and distributed by !K7. “Salty” (the first single) and all of Adult Baby are teeming with contributions from significant pioneers of the global pop, electronic, rock and indie scenes such as Ryuichi Sakamoto, Mauro Refosco (Atoms for Peace, Red Hot Chili Peppers, David Byrne) and Ian Chang (Son Lux, Landlady).

“We’ve never really had anyone say to us, ‘All right, this song is good but we should try to push it to another level,’” Hot Chip’s Joe Goddard tells Apple Music. Seven albums deep, the band—Goddard, Alexis Taylor, Al Doyle, Owen Clarke, and Felix Martin—decided to reach new levels by working with producers for the first time, drafting in Rodaidh McDonald (The xx, Sampha) and the late French touch prime mover Philippe Zdar. “They didn\'t really ask us to do anything mega crazy, but there were moments when they challenged us and pushed us out of our comfort zone, which was really healthy and good,” says Goddard. *A Bath Full of Ecstasy* handsomely vindicates the decision to solicit external opinion. Rather than abandon their winning synthesis of pop melodies, melancholy, and the sparkle of club music, the band has finessed it into their brightest, sharpest album yet. And they got there with the help of Katy Perry, hot sauce, and Taylor’s mother-in-law—discover how with their track-by-track guide. **“Melody of Love”** Alexis Taylor: “It’s about submitting to sound, and finding optimism within its abstract beauty. It’s about the personal as well as the more universal problems being faced by individuals, and overcoming those; it’s about connecting to something that resonates with you.” Joe Goddard: “I was initially imagining I would put it out without vocals on, without there really being a song. But I found this sample from a gospel track by The Mighty Clouds of Joy, and Alexis responded to the music very quickly and wrote these great words. Rodaidh is a very focused person, a bit like the T-1000, and was like, ‘OK, guys, we’re going to do this, this, this, this, this.’ And he cut it right down, which was a really good suggestion.” **“Spell”** AT: “This is a seduction song, but it’s not entirely clear who is in the driving seat, who has the upper hand, who holds the whip…” JG: “Alexis’ songwriting and lyrics are fantastic, but he is such an enormous lover of Prince, I felt like there would be places that he could go that would be slightly more sensual, sexual. And that he would really excel at it. But I don’t think it comes naturally to him. Then we were asked to do a few days in the studio with Katy Perry. We wrote a bunch of short demo ideas to play to her, and the beginning of ‘Spell’ was one of those. I think for Alexis, imagining writing something for her was quite freeing.” **“Bath Full of Ecstasy”** AT: “‘Bath Full of Ecstasy’ is a side-scrolling platform game in which the player takes control of one of the five band members on a quest to save the kingdom. A curse has ravaged the kingdom and eradicated all joy from the land, and the townsfolk and villagers can no longer see colors or hear music. With the help of the Bubble Bath Fairy, a magical microphone, and some friendly strangers along the way, the band must embark on a quest through five exciting worlds on a mission to find the secret source that will break the curse.” **“Echo”** JG: “The demo was another one that we wrote for the Katy Perry sessions. We were trying to do something a bit Neptunes-y, a bit Pharrell—quite simple hip-hop-y bassline and drums. Lyrically it deals with letting go of your past.” AT: “It was originally called ‘Hot Sauce’ and was written about my favorite hot sauce, made by my friend, the steel-pan legend Fimber Bravo.” Al Doyle: “This was Philippe bringing to the pool his concept of ‘air,’ putting in huge gaps and spaces and really reducing the sonic palette of the song—to the point where you’re almost like, ‘Oh wow, this is actually almost too sparse.’ But what is there is extremely powerful and crafted and razor-sharp.” **“Hungry Child”** JG: “It’s all about this real longing, obsessional kind of love—unrequited. Obviously, a classic subject for soul and disco music, and I was really channeling that. I love disco records that do that; I think there’s a real special power to them. And in Jamie Principle, Frankie Knuckles, that brilliant deep house classic Round Two, ‘New Day,’ you get this obsessional, dark love stuff as well.” AT: “I mainly played Mellotron and wrote the chorus—about things which are momentary but somehow affect you forever.” **“Positive”** AT: “The song talks about perceptions of homelessness, illness, the need for community, kind gestures or lack of, information, love. It’s a heartbreak song with those subjects and a fantasy relationship at the core.” JG: “It features this Eurorack synth stuff very heavily, which is screamingly modern-sounding.” **“Why Does My Mind”** AT: “A song written on Alex Chilton’s guitar, lent to me by Jason McPhail \[of Glasgow band V-Twin\], about the perplexing way in which my mind works.” **“Clear Blue Skies”** JG: “Once a record is 70 percent done, you’re thinking about how to complement the music that you already have. So we wanted to have a more gentle, drum-machine-led thing. I was really also inspired by ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ by Brian Eno, which has that feel. I find it really difficult, with the size of the universe, trying to find that meaning in small things. I find that really problematic sometimes—that’s the meaning of the song.” **“No God”** AT: “A love song, written with my mother-in-law in mind as the singer, for a TV talent show contest, but never delivered to her, and instead turned into a euphoric song about love for a person rather than God, or light.” JG: “The chorus and the verse are very, very simple pop music. It reminded us of ABBA at one point. We struggled to find a production that was interesting, that had the right balance of strangeness and poppiness. It reminds me a bit of Andrew Weatherall and Primal Scream, that kind of balearic house thing.” Owen Clarke: “It went reggae for a bit. It had a techno moment as well.”

A journey through the night. Nocturnal animals, living on the run. Can you leave that life behind?

Big Thief had only just finished work on their 3rd album, U.F.O.F. – “the celestial twin” – days before in a cabin studio in the woods of Washington State. Now it was time to birth U.F.O.F.’s sister album – “the earth twin” – Two Hands. 30 miles west of El Paso, surrounded by 3,000 acres of pecan orchards and only a stone’s throw from the Mexican border, Big Thief (a.k.a. Adrianne Lenker, Buck Meek, Max Oleartchik, and James Krivchenia) set up their instruments as close together as possible to capture their most important collection of songs yet. Where U.F.O.F.layered mysterious sounds and effects for levitation, Two Hands grounds itself on dried-out, cracked desert dirt. In sharp contrast to the wet environment of the U.F.O.F. session, the southwestern Sonic Ranch studio was chosen for its vast desert location. The 105-degree weather boiled away any clinging memories of the green trees and wet air of the previous session. Two Hands had to be completely different — an album about the Earth and the bones beneath it. The songs were recorded live with almost no overdubs. All but two songs feature entirely live vocal takes, leaving Adrianne’s voice suspended above the mix in dry air, raw and vulnerable as ever. “Two Hands has the songs that I’m the most proud of; I can imagine myself singing them when I’m old,” says Adrianne. “Musically and lyrically, you can’t break it down much further than this. It’s already bare-bones.” Lyrically this can be felt in the poetic blur of the internal and external. These are political songs without political language. They explore the collective wounds of our Earth. Abstractions of the personal hint at war, environmental destruction, and the traumas that fuel it. Across the album, there are genuine attempts to point the listener towards the very real dangers that face our planet. When Adrianne sings “Please wake up,” she’s talking directly to the audience. Engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who were both behind U.F.O.F., capture the live energy as instinctually and honestly as possible. Sarlo teamed up with James Krivchenia to mix the album, where they sought to emphasize raw power and direct energy inherent in the takes. The journey of a song from the stage to the record is often a difficult one. Big Thief’s advantage is their bond and loving centre as a chosen family. They spend almost 100% of their lives together working towards a sound that they all agree upon. A band with this level of togetherness is increasingly uncommon. If you ask drummer James Krivchenia, bassist Max Oleartchik or guitarist Buck Meek how they write their parts, they will describe — passionately — the experience of hearing Adrianne present a new song, listening intently for hints of parts that already exist in the ether and the undertones to draw out with their respective instruments. With raw power and intimacy, Two Hands folds itself gracefully into Big Thief’s impressive discography. This body of work grows deeper and more inspiring with each new album.