MondoSonoro's Best Albums of 2023

Este mes Boygenius, es decir, el proyecto emprendido por Phoebe Bridgers, Lucy Dacus y Julien Baker, protagoniza nuestra portada

Published: November 30, 2023 07:49

Source

You’ll be hard-pressed to find a description of boygenius that doesn’t contain the word “supergroup,” but it somehow doesn’t quite sit right. Blame decades of hoary prog-rock baggage, blame the misbegotten notion that bigger and more must be better, blame a culture that is rightfully circumspect about anything that feels like overpromising, blame Chickenfoot and Audioslave. But the sentiment certainly fits: Teaming three generational talents at the height of their powers on a project that is somehow more than the sum of its considerable parts sounds like it was dreamed up in a boardroom, but would never work if it had been. In fall 2018, Phoebe Bridgers, Lucy Dacus, and Julien Baker released a self-titled six-song EP as boygenius that felt a bit like a lark—three of indie’s brightest, most charismatic artists at their loosest. Since then, each has released a career-peak album (*Punisher*, *Home Video*, and *Little Oblivions*, respectively) that transcended whatever indie means now and placed them in the pantheon of American songwriters, full stop. These parallel concurrent experiences raise the stakes of a kinship and a friendship; only the other two could truly understand what each was going through, only the other two could mount any true creative challenge or inspiration. Stepping away from their ascendant solo paths to commit to this so fully is as much a musical statement as it is one about how they want to use this lightning-in-a-bottle moment. If *boygenius* was a lark, *the record* is a flex. Opening track “Without You Without Them” features all three voices harmonizing a cappella and feels like a statement of intent. While Bridgers’ profile may be demonstrably higher than Dacus’ or Baker’s, no one is out in front here or taking up extra oxygen; this is a proper three-headed hydra. It doesn’t sound like any of their own albums but does sound like an album only the three of them could make. Hallmarks of each’s songwriting style abound: There’s the slow-building climactic refrain of “Not Strong Enough” (“Always an angel, never a god”) which recalls the high drama of Baker’s “Sour Breath” and “Turn Out the Lights.” On “Emily I’m Sorry,” “Revolution 0,” and “Letter to an Old Poet,” Bridgers delivers characteristically devastating lines in a hushed voice that belies its venom. Dacus draws “Leonard Cohen” so dense with detail in less than two minutes that you feel like you’re on the road trip with her and her closest friends, so lost in one another that you don’t mind missing your exit. As with the EP, most songs feature one of the three taking the lead, but *the record* is at its most fully realized when they play off each other, trading verses and ideas within the same song. The subdued, acoustic “Cool About It” offers three different takes on having to see an ex; “Not Strong Enough” is breezy power-pop that serves as a repudiation of Sheryl Crow’s confidence (“I’m not strong enough to be your man”). “Satanist” is the heaviest song on the album, sonically, if not emotionally; over a riff with solid Toadies “Possum Kingdom” vibes, Baker, Bridgers, and Dacus take turns singing the praises of satanism, anarchy, and nihilism, and it’s just fun. Despite a long tradition of high-wattage full-length star team-ups in pop history, there’s no real analogue for what boygenius pulls off here. The closest might be Crosby, Stills & Nash—the EP’s couchbound cover photo is a wink to their 1969 debut—but that name doesn’t exactly evoke feelings of friendship and fellowship more than 50 years later. (It does, however, evoke that time Bridgers called David Crosby a “little bitch” on Twitter after he chastised her for smashing her guitar on *SNL*.) Their genuine closeness is deeply relatable, but their chemistry and talent simply aren’t. It’s nearly impossible for a collaboration like this to not feel cynical or calculated or tossed off for laughs. If three established artists excelling at what they are great at, together, without sacrificing a single bit of themselves, were so easy to do, more would try.

For the last two decades, Sufjan Stevens’ music has taken on two distinct forms. On one end, you have the ornate, orchestral, and positively stuffed style that he’s excelled at since the conceptual fantasias of 2003’s star-making *Michigan*. On the other, there’s the sparse and close-to-the-bone narrative folk-pop songwriting that’s marked some of his most well-known singles and albums, first fully realized on the stark and revelatory *Seven Swans* from 2004. His 10th studio full-length, *Javelin*, represents the fullest and richest merging of those two approaches that Stevens has achieved to date. Even as it’s been billed as his first proper “songwriter’s album” since 2015’s autobiographical and devastating *Carrie & Lowell*, *Javelin* is a kaleidoscopic distillation of everything Stevens has achieved in his career so far, resulting in some of the most emotionally affecting and grandiose-sounding music he’s ever made. *Javelin* is Stevens’ first solo record of vocal-based music since 2020’s *The Ascension*, and it’s relatively straightforward compared to its predecessor’s complexity. Featuring contributions from vocalists and frequent collaborators like Nedelle Torrisi, adrienne maree brown, Hannah Cohen, and The National’s Bryce Dessner (who adds his guitar skills to the heart-bursting epic “Shit Talk”), the record certainly sounds like a full-group effort in opposition to the angsty isolation that streaked *The Ascension*. But at the heart of *Javelin* is Stevens’ vocals, the intimacy of which makes listeners feel as if they’re mere feet away from him. There’s callbacks to Stevens’ discography throughout, from the *Age of Adz*-esque digital dissolve that closes out “Genuflecting Ghost” to the rustic Flannery O’Connor evocations of “Everything That Rises,” recalling *Seven Swans*’ inspirational cues from the late fiction writer. Ultimately, though, *Javelin* finds Stevens emerging from the depressive cloud of *The Ascension* armed with pleas for peace and a distinct yearning to belong and be embraced—powerful messages delivered on high, from one of the 21st century’s most empathetic songwriters.

During the pandemic, Fontaines D.C. singer Grian Chatten returned to Skerries, the town on Ireland’s East Coast where he’d spent his teenage years. One night, walking along the beach, something came to him. “It was when the moon conjures a strip of light along the horizon towards you, like a path to heaven,” he tells Apple Music. “And there’s the gentle ebb and flow of an invisible ocean around it.” As he looked to sea, new music seeped into his head—a sort of pier-end lounge pop played out on brass and strings. It didn’t really fit with the ideas Fontaines had been fermenting for their next record; instead it opened up inspiration for a solo album. There were, thought Chatten, stories to be told about lives being etched out in coastal areas like Skerries. “The whole atmosphere of the place, there’s something slightly set about it,” he says. “I’m really into fantasy, the Muppets movies and *The Dark Crystal*, or even *Sweeney Todd*, where they demand a slight suspension of disbelief of the audience in order to achieve, or embellish on, a very human emotion. I wanted to live the town through those kind of lenses.” By late 2022, as Chatten endured some heavy personal turbulence, the songs he was writing helped process his own experiences. “It was like, ‘How do I actually feel right now?’” he says. “Just by painting a picture of the darkness, I gleaned an understanding from it. I was then able to cordon it off.” Unsurprisingly then, *Chaos for the Fly* is as intimate as Chatten has sounded on record. Built from mostly acoustic foundations, the songs explore grief, isolation, betrayal, and escapism—but their intensity is a little more insidious and measured than on Fontaines’ sinewy music. Even the corrosively jaundiced “All of the People” is delivered with steady calm, Chatten warning, “People are scum/I will say it again” under a soft shroud of piano and precisely picked guitar. “There’s probably times on the record where it becomes almost self-indulgent, the personal nature of it,” he says. “It’s a startlingly fair reflection of me, I suppose. I didn’t really realize that was possible.” Read on for his track-by-track guide. **“The Score”** “I had a 10-day break in between two tours. I find it very difficult to switch off, and my manager said, ‘You need to go off somewhere,’ so I went to Madrid. I got antsy without being able to write music—the whole point, really, of me being away—and I actually asked Carlotta \[Cosials, singer/guitarist\] from Hinds if she knew any good guitar shops, so I could grab a Spanish guitar, a nylon. She sent me the name of a place that was just around the corner, and I had ‘The Score’ later on that day. When it comes to the second chord, I think that opens the curtain a bit. There’s a sort of subverted cabaret about it, which I really like. And there’s also a misdirection of the modalities of the chords. It goes to a kind of surprising chord. There’s a nice sleight of hand to the first few seconds of it. I really wanted that to be the tone-setter of the album.” **“Last Time Every Time Forever”** “This was inspired by the sound of these fruit machines and slot machines that I grew up with. There was this casino in town, called Bob’s Casino. It’s about addiction or dependence on something, and I’m not really talking specifically about drugs and booze or anything like that. I’m just talking about compulsive behavior and escapism, which are things that kind of shift my gears—I can relate to the pursuit of another world. It has that weird push that it does in the drums. I think it sounds kind of like stunted growth, like it’s glitching.” **“Fairlies”** “After Madrid, we went down to a town called Jerez, which was the birthplace of flamenco, I believe. We were going to go out to get a beer or something, myself and my fiancée. She was getting ready and I wrote that tune. There’s loads of bootleg recordings of The La’s, and I think they really affected me when I was slightly younger, when we were setting off the band. There’s a tune, ‘Tears in the Rain.’ There’s something about the way Lee Mavers does all that weird stuff with his vocals that really affected the way I write a lot of melodies. The snappy, jaunty, almost poke-y, edgy melody of the chorus, that was inspired by Lee Mavers. The verses are more Lee Hazlewood and Leonard Cohen, maybe.” **“Bob’s Casino”** “I heard the intro to ‘Bob’s Casino’ \[that night on the beach\]. Similar to ‘Last Time Every Time Forever,’ ‘Bob’s Casino’ is a tune about a kind of addiction and inertia and isolation. I wanted it to sound as beautiful as it sounds in the addict’s head, or the isolated person’s head, when they achieve those moments of respite. I think that’s a much more realistic picture than a tune that sounds scared straight or something. A play, or any good piece of screenwriting, is usually helped by the bad guys or the antagonist being relatable, or seeing a side of them that makes you empathize with them, or even love them, briefly. It creates this nice 3D effect. I enjoyed writing from that character’s perspective because I feel like I’m expressing something. I’m not saying that I am that character. But the character has a good chance of winning sometimes within me. The more I write about it and express it, then maybe the less chance that character has of taking over.” **“All of the People”** “This is probably my proudest moment from the album. I’m giving myself compliments here, but I think there’s a surgical kind of precision to it. There’s nothing wasted. I really like the natural swells. I like how it swells when the lyric swells. I really do feel that fucking shit sometimes, as do a lot of people. I’m grateful for that song, for what it did for my head when I wrote it. I can stand back and look at it now. It’s like I’ve blown that poison into a bottle and I’ve sealed the bottle, and now I’ve put it on a shelf.” **“East Coast Bed”** “‘East Coast Bed’ is about the death of my beloved hurling coach, who was like a second mother to me growing up, a woman called Ronnie Fay. The whole idea of the East Coast bed is firstly this refuge that she offered me when I was growing up. And then eventually, we laid her in her own East Coast bed when we buried her. The song is essentially about death. Not necessarily in a grim way, but in a sad, melancholic, moving-on way. That synth part that Dan Carey \[producer\] did sounds like the soul moving on for me. That was him exercising his great sympathy for the music that he works on.” **“Salt Throwers off a Truck”** “I remember the title coming to me when we were writing \[2022 Fontaines D.C. album\] *Skinty Fia*. There were lads on the back of a truck, salting the road outside the rehearsal space. I thought that was an interesting sight: ‘Oh, that’s a good title to have to justify with a good lyric.’ I like the fact that it scours the world a little bit. There’s New York in there and, although they’re not mentioned explicitly, other places too. The last verse is inspired by my own granddad’s death last year in Barrow-in-Furness. It’s different people at different stages. To me, it feels like when a director puts the audience in the eyes of a bird. There’s an omnipresence to it that I really like. It’s like when Scrooge is visited by the Ghosts of Christmas Past and Present and Future, and he gets to fly around, and visit all of these different vignettes, or all these different families in their houses.” **“I Am so Far”** “I wrote that one during the dreaded and not-very-aesthetic-to-talk-about lockdown. It was this kind of bleak and beautiful, ‘all the time in the world and nothing to do’ sort of thing that interested me then. That’s why there’s so much drudgery on the track. I wrote that on the East Coast again. It does sound to me a little bit like water, with light on it.” **“Season for Pain”** “I think it’s an abdication. It’s like cutting something you love out of your life. It sounds sad, and it is sad, and it is dark, but it’s putting up a necessary wall. It’s terminating a friendship or relationship with someone that you truly love. It’s not going to be easy for anyone, but it’s gone too far. I think there’s something about the production that slightly isolates it from the album. It feels slightly afterthought-ish, which I like. I like the end, which came from a jam. We’d finished recording the track, the tape was still rolling, and we just started playing, and then that became the outro. The song is about moving on and it sounds like I’m moving on at the end.”

As much as Romy Madley Croft’s debut solo album is an absorbingly personal record, its roots lie in music intended for other people. In 2019, The xx singer/guitarist met—and immediately gelled with—Fred again.. during a period of creative exploration that lead her to Los Angeles to try writing chart-topping pop songs for other artists. “I ended up writing some quite honest songs about myself, thinking someone else was going to sing them, and realizing, ‘Actually, maybe these are my songs…’” Romy tells Apple Music. Arriving in 2020, airy, anthemic debut solo single “Lifetime” was written to uplift herself during the pandemic. In stark contrast to the hush and restraint of The xx, the song leaned into the rapturous dance music influences of Romy’s youth, and it’s a direction continued on *Mid Air*. “At the time \[that The xx emerged\], I was genuinely just suited to feeling more shy and being more guarded,” she says. “It was nice to share a different side, and it definitely opened up a lot more doors in terms of the way people see me. I wanted to find a way to balance melodic, storytelling pop writing with club-referenced music, and Robyn was a big reference. She makes very emotional songs within a dance/electronic sphere. Robyn is someone that I really admire. I’ve met her a few times and I’ve sort of mentioned to her that I’m on this journey with it and she’s been really encouraging and supportive.” Co-produced with Fred again.., bandmate Jamie xx and veteran hitmaker Stuart Price, *Mid Air* succeeds in building a dance floor on which Romy can shake out her feelings. The joy and freedom of the shiny synths and skyscraping melodies serve as a misdirect to the lyrical themes of grief and heartbreak, rooted in the loss of both her parents at a young age and, recently, another very close family member. “I wrote \[lead single\] ‘Strong’ and ‘Enjoy Your Life’ as part of an ongoing ambition to remember to check in and talk to people and let things out,” she says. “I’ve had to talk about grief and my parents way more than I would if the whole album was just love songs. I’m ready to talk about it more. It’s been amazing having conversations with people that I wouldn’t normally have, and hearing and learning and connecting. People come up to me in a club to talk to me about grief and I’m like, ‘Wow, actually, this is very special.’ The fact that people feel like they can talk to me means a lot.” Let Romy guide you through *Mid Air* track by track. **“Loveher”** “This is the first song that I made with Fred after writing these songs for other people, the first track that I wrote thinking, ‘This actually is my song to sing.’ Very much the first tentative steps into this project. It opens the album because I can hear that slight nervousness in it and I shed that as the tracks go on. I had done a songwriting session with King Princess and she was like, ‘This is who I love, I’m writing a song about a girl, there’s no question.’ I was really inspired by the way that she was very comfortable with that. I thought about myself at that similar age and I didn’t feel that way. I didn’t feel comfortable or reassured that it would be chill for me to say that. Maybe it would’ve been fine, but in my head I was worried about it. The more young, queer artists I hear talking about their exact experiences and being really amazing, visible, inspiring people, the more I’m inspired to do my own thing and talk about my actual experiences in a clear way.” **“Weightless”** “This song is about realizing, ‘Wow, I’m really feeling all these things and that’s OK,’ and really embracing that. It still feels like it’s from the earlier, tentative time, lyrically. It was originally written as an acoustic ballad, and I wanted it to become more than that, so I went on a journey to take it into an electronic space. It was a challenge I set myself—I still wanted it to work when you take it off the track and take it back to the guitar. That’s something I admire about a well-written song.” **“The Sea”** “The lyrics for ‘The Sea’ are inspired by a trip to Ibiza. Or my vision of what it would have been like in the early 2000s—the dream of Ibiza. I went for the first time for Oliver’s \[Sim, The xx bandmate\] 30th birthday. We went out clubbing and we went on a boat and it was exactly what I had hoped it was. I’ve been back since, for my honeymoon. I also got to play Pacha in 2022, which was really amazing. But that first time, I was listening to the instrumental while I was driving around and I was thinking, ‘I want this song to feel connected to this place. I want it to feel like a home in a summer situation.’ So that’s how I framed it, lyrically.” **“One Last Time”** “I wrote this thinking it was for someone else—I didn’t have anyone specifically in mind, but just as a fan, if I had to pick someone, Beyoncé is my number-one person. Thinking it wasn’t going to be me singing pushed me to try out something new, vocally. Just pushing my voice. It was fun to come back to it and sing it in my own way. It’s one of my favorites to sing.” **“DMC”** “I love an interlude. I feel like that’s quite a pop-album thing. My friend always says that she loves a DMC corner in the club—I don’t know if everyone knows DMC is a deep, meaningful conversation, but that’s what it means to me. Those moments where you have a kind of emotional exchange somewhere that ends up being the right place, even though it’s not typically the place you have those chats. This is just a little moment of stepping outside of where we’ve been, like we’re outside the club. You have a little reset and you carry on.” **“Strong”** “I wrote this one for myself, using songwriting as a way of processing grief and my relationship to it and putting it out there. I internalized a lot of things for a long time and thought I’d put it out of sight, out of mind. I think having time off tour and being in a good place in a relationship was when it all started to come up and I had to face those things. ‘Strong’ was me just reflecting on that at that point, and just feeling it out, and trying to write around that. It was great to put it in a song that is quite uplifting and high tempo. It keeps giving different meanings to me in different contexts.” **“Twice”** “I worked on this with an amazing songwriter called Ilsey, who co-wrote ‘Nothing Breaks Like a Heart’ \[by Mark Ronson and Miley Cyrus\]. I’d been writing for other people for a while and finding it hard to make connections. I wanted something a bit more real. Ilsey has got quite a country style, so when I got paired up with her, I opened up and said, ‘This is what I’m going through,’ and she helped me write this very storytelling-like song. I’d never had a songwriter help me lyrically before, but it was really cool. It’s another one that started as a guitar ballad, but I didn’t want it to stay that way. Stuart worked on it and it evolved into what it is now—echoes of a club and then building into being a big club-experience track.” **“Did I”** “This was sonically created around the same time as ‘Strong.’ I’ve written a lot of acoustic music and I wanted to put it into a different frame, so I was playing a lot of early-2000s trance to Fred. There’s already a blueprint embedded in trance—a haunting vocal and huge chords and builds and euphoria. It’s one of my favorites, so I’ve been playing it out in clubs recently. Lyrically it reflects a part of my relationship \[with my wife\], from back when we were younger and we broke up.” **“Mid Air” (feat. Beverly Glenn-Copeland)** “I consider this to be a transitional moment on the album. The fact that Fred and I made this piece of music together is a reflection of a weird moment we were both in—it’s more winding and introspective than everything else we did together. Although there’s a lot of euphoric sounds on the album, I’m not always super upbeat, there’s times when I have a bit of a weird time mentally. It’s kind of the aftermath of the night out: ‘Twice’ and ‘Did I’ connect as a mix and ‘Mid Air’ is the musical comedown. \[American singer and composer\] Beverly Glenn-Copeland’s voice comes in as a reminder, a self check-in. Then you come back into ‘Enjoy Your Life’ as a reaction to that.” **“Enjoy Your Life”** “This was probably the most challenging song to make because it contains a lot of different elements. I’m trying to say quite a lot in it and make it danceable and contain lots of samples. Finding the balance took quite a long time. When I heard \[Beverly Glenn-Copeland\] say, ‘My mother says to me/Enjoy your life,’ I thought it was such a beautifully simple disarming sentence, but I didn’t want to just say, ‘Yeah, life’s amazing.’ I wanted there to be a journey in the song. In the verses, I’m processing some stuff, I’m having a bit of a weird time, but I’m reminding myself: Life is short, enjoy your life. I wanted there to be enough of a narrative to give that context. Just to acknowledge and then also celebrate.” **“She’s on My Mind”** “I wanted to end the album with this because it feels like the end of the night when you’re at a party and someone puts a disco song on and everyone just has their hands in their air. It’s a fun one to end on. Just embracing and accepting how you feel. From the way that I start the album—the more tentative way of singing—to the end where the last thing I sing is, ‘I don’t care anymore,’ it’s a bit of a release of pressure.”

ANOHNI’s music revolves around the strength found in vulnerability, whether it’s the naked trembling of her voice or the way her lyrics—“It’s my fault”; “Why am I alive?”; “You are an addict/Go ahead, hate yourself”—cut deeper the simpler they get. Her first album of new material with her band the Johnsons since 2010’s *Swanlights* sets aside the more experimental/electronic quality of 2016’s *HOPELESSNESS* for the tender avant-soul most listeners came to know her by. She mourns her friends (“Sliver of Ice”), mourns herself (“It’s My Fault”), and catalogs the seemingly limitless cruelty of humankind (“It Must Change”) with the quiet resolve of someone who knows that anger is fine but the true warriors are the ones who kneel down and open their hearts.

As Olivia Rodrigo set out to write her second album, she froze. “I couldn\'t sit at the piano without thinking about what other people were going to think about what I was playing,” she tells Apple Music. “I would sing anything and I\'d just be like, ‘Oh, but will people say this and that, will people speculate about whatever?’” Given the outsized reception to 2021’s *SOUR*—which rightly earned her three Grammys and three Apple Music Awards that year, including Top Album and Breakthrough Artist—and the chatter that followed its devastating, extremely viral first single, “drivers license,” you can understand her anxiety. She’d written much of that record in her bedroom, free of expectation, having never played a show. The week before it was finally released, the then-18-year-old singer-songwriter would get to perform for the first time, only to televised audiences in the millions, at the BRIT Awards in London and on *SNL* in New York. Some artists debut—Rodrigo *arrived*. But looking past the hype and the hoo-ha and the pressures of a famously sold-out first tour (during a pandemic, no less), trying to write as anticipated a follow-up album as there’s been in a very long time, she had a realization: “All I have to do is make music that I would like to hear on the radio, that I would add to my playlist,” she says. “That\'s my sole job as an artist making music; everything else is out of my control. Once I started really believing that, things became a lot easier.” Written alongside trusted producer Dan Nigro, *GUTS* is both natural progression and highly confident next step. Boasting bigger and sleeker arrangements, the high-stakes piano ballads here feel high-stakes-ier (“vampire”), and the pop-punk even punkier (“all-american bitch,” which somehow splits the difference between Hole and Cat Stevens’ “Here Comes My Baby”). If *SOUR* was, in part, the sound of Rodrigo picking up the pieces post-heartbreak, *GUTS* finds her fully healed and wholly liberated—laughing at herself (“love is embarrassing”), playing chicken with disaster (the Go-Go’s-y “bad idea right?”), not so much seeking vengeance as delighting in it (“get him back!”). This is Anthem Country, joyride music, a set of smart and immediately satisfying pop songs informed by time spent onstage, figuring out what translates when you’re face-to-face with a crowd. “Something that can resonate on a recording maybe doesn\'t always resonate in a room full of people,” she says. “I think I wrote this album with the tour in mind.” And yet there are still moments of real vulnerability, the sort of intimate and sharply rendered emotional terrain that made Rodrigo so relatable from the start. She’s straining to keep it together on “making the bed,” bereft of good answers on “logical,” in search of hope and herself on gargantuan closer “teenage dream.” Alone at a piano again, she tries to make sense of a betrayal on “the grudge,” gathering speed and altitude as she goes, each note heavier than the last, “drivers license”-style. But then she offers an admission that doesn’t come easy if you’re sweating a reaction: “It takes strength to forgive, but I don’t feel strong.” In hindsight, she says, this album is “about the confusion that comes with becoming a young adult and figuring out your place in this world and figuring out who you want to be. I think that that\'s probably an experience that everyone has had in their life before, just rising from that disillusionment.” Read on as Rodrigo takes us inside a few songs from *GUTS*. **“all-american bitch”** “It\'s one of my favorite songs I\'ve ever written. I really love the lyrics of it and I think it expresses something that I\'ve been trying to express since I was 15 years old—this repressed anger and feeling of confusion, or trying to be put into a box as a girl.” **“vampire”** “I wrote the song on the piano, super chill, in December of \[2022\]. And Dan and I finished writing it in January. I\'ve just always been really obsessed with songs that are very dynamic. My favorite songs are high and low, and reel you in and spit you back out. And so we wanted to do a song where it just crescendoed the entire time and it reflects the pent-up anger that you have for a situation.” **“get him back!”** “Dan and I were at Electric Lady Studios in New York and we were writing all day. We wrote a song that I didn\'t like and I had a total breakdown. I was like, ‘God, I can\'t write songs. I\'m so bad at this. I don\'t want to.’ Being really negative. Then we took a break and we came back and we wrote ‘get him back!’ Just goes to show you: Never give up.” **“teenage dream”** “Ironically, that\'s actually the first song we wrote for the record. The last line is a line that I really love and it ends the album on a question mark: ‘They all say that it gets better/It gets better the more you grow/They all say that it gets better/What if I don\'t?’ I like that it’s like an ending, but it\'s also a question mark and it\'s leaving it up in the air what this next chapter is going to be. It\'s still confused, but it feels like a final note to that confusion, a final question.”

“You can feel a lot of motion and energy,” Caroline Polachek tells Apple Music of her second solo studio album. “And chaos. I definitely leaned into that chaos.” Written and recorded during a pandemic and in stolen moments while Polachek toured with Dua Lipa in 2022, *Desire, I Want to Turn Into You* is Polachek’s self-described “maximalist” album, and it weaponizes everything in her kaleidoscopic arsenal. “I set out with an interest in making a more uptempo record,” she says. “Songs like ‘Bunny Is a Rider,’ ‘Welcome to My Island,’ and ‘Smoke’ came onto the plate first and felt more hot-blooded and urgent than anything I’d done before. But of course, life happened, the pandemic happened, I evolved as a person, and I can’t really deny that a lunar, wistful side of my writing can never be kept out of the house. So it ended up being quite a wide constellation of songs.” Polachek cites artists including Massive Attack, SOPHIE, Donna Lewis, Enya, Madonna, The Beach Boys, Timbaland, Suzanne Vega, Ennio Morricone, and Matia Bazar as inspirations, but this broad church only really hints at *Desire…*’s palette. Across its 12 songs we get trip-hop, bagpipes, Spanish guitars, psychedelic folk, ’60s reverb, spoken word, breakbeats, a children’s choir, and actual Dido—all anchored by Polachek’s unteachable way around a hook and disregard for low-hanging pop hits. This is imperial-era Caroline Polachek. “The album’s medium is feeling,” she says. “It’s about character and movement and dynamics, while dealing with catharsis and vitality. It refuses literal interpretation on purpose.” Read on for Polachek’s track-by-track guide. **“Welcome to My Island”** “‘Welcome to My Island’ was the first song written on this album. And it definitely sets the tone. The opening, which is this minute-long non-lyrical wail, came out of a feeling of a frustration with the tidiness of lyrics and wanting to just express something kind of more primal and urgent. The song is also very funny. We snap right down from that Tarzan moment down to this bitchy, bratty spoken verse that really becomes the main personality of this song. It’s really about ego at its core—about being trapped in your own head and forcing everyone else in there with you, rather than capitulating or compromising. In that sense, it\'s both commanding and totally pathetic. The bridge addresses my father \[James Polachek died in 2020 from COVID-19\], who never really approved of my music. He wanted me to be making stuff that was more political, intellectual, and radical. But also, at the same time, he wasn’t good at living his own life. The song establishes that there is a recognition of my own stupidity and flaws on this album, that it’s funny and also that we\'re not holding back at all—we’re going in at a hundred percent.” **“Pretty in Possible”** “If ‘Welcome to My Island’ is the insane overture, ‘Pretty in Possible’ finds me at street level, just daydreaming. I wanted to do something with as little structure as possible where you just enter a song vocally and just flow and there\'s no discernible verses or choruses. It’s actually a surprisingly difficult memo to stick to because it\'s so easy to get into these little patterns and want to bring them back. I managed to refuse the repetition of stuff—except for, of course, the opening vocals, which are a nod to Suzanne Vega, definitely. It’s my favorite song on the album, mostly because I got to be so free inside of it. It’s a very simple song, outside a beautiful string section inspired by Massive Attack’s ‘Unfinished Sympathy.’ Those dark, dense strings give this song a sadness and depth that come out of nowhere. These orchestral swells at the end of songs became a compositional motif on the album.” **“Bunny Is a Rider”** “A spicy little summer song about being unavailable, which includes my favorite bassline of the album—this quite minimal funk bassline. Structurally on this one, I really wanted it to flow without people having a sense of the traditional dynamics between verses and choruses. Timbaland was a massive influence on that song—especially around how the beat essentially doesn\'t change the whole song. You just enter it and flow. ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ was a set of words that just flowed out without me thinking too much about it. And the next thing I know, we made ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ thongs. I love getting occasional Instagram tags of people in their ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ thongs. An endless source of happiness for me.” **“Sunset”** “This was a song I began writing with Sega Bodega in 2020. It sounded completely nothing like the others. It had a folk feel, it was gypsy Spanish, Italian, Greek feel to it. It completely made me look at the album differently—and start to see a visual world for them that was a bit more folk, but living very much in the swirl of city life, having this connection to a secret, underground level of antiquity and the universalities of art. It was written right around a month or two after Ennio Morricone passed away, so I\'d been thinking a lot about this epic tone of his work, and about how sunsets are the biggest film clichés in spaghetti westerns. We were laughing about how it felt really flamenco and Spanish—not knowing that a few months later, I was going to find myself kicked out of the UK because I\'d overstayed my visa without realizing it, and so I moved my sessions with Sega to Barcelona. It felt like the song had been a bit of a premonition that that chapter-writing was going to happen. We ended up getting this incredible Spanish guitarist, Marc Lopez, to play the part.” **“Crude Drawing of an Angel”** “‘Crude Drawing of an Angel’ was born, in some ways, out of me thinking about jokingly having invented the word ‘scorny’—which is scary and horny at the same time. I have a playlist of scorny music that I\'m still working on and I realized that it was a tone that I\'d never actually explored. I was also reading John Berger\'s book on drawing \[2005’s *Berger on Drawing*\] and thinking about trace-leaving as a form of drawing, and as an extremely beautiful way of looking at sensuality. This song is set in a hotel room in which the word ‘drawing’ takes on six different meanings. It imagines watching someone wake up, not realizing they\'re being observed, whilst drawing them, knowing that\'s probably the last time you\'re going to see them.” **“I Believe”** “‘I Believe’ is a real dedication to a tone. I was in Italy midway through the pandemic and heard this song called ‘Ti Sento’ by Matia Bazar at a house party that blew my mind. It was the way she was singing that blew me away—that she was pushing her voice absolutely to the limit, and underneath were these incredible key changes where every chorus would completely catch you off guard. But she would kind of propel herself right through the center of it. And it got me thinking about the archetype of the diva vocally—about how really it\'s very womanly that it’s a woman\'s voice and not a girl\'s voice. That there’s a sense of authority and a sense of passion and also an acknowledgment of either your power to heal or your power to destroy. At the same time, I was processing the loss of my friend SOPHIE and was thinking about her actually as a form of diva archetype; a lot of our shared taste in music, especially ’80s music, kind of lined up with a lot of those attitudes. So I wanted to dedicate these lyrics to her.” **“Fly to You” (feat. Grimes and Dido)** “A very simple song at its core. It\'s about this sense of resolution that can come with finally seeing someone after being separated from them for a while. And when a lot of misunderstanding and distrust can seep in with that distance, the kind of miraculous feeling of clearing that murk to find that sort of miraculous resolution and clarity. And so in this song, Grimes, Dido, and I kind of find our different version of that. But more so than anything literal, this song is really about beauty, I think, about all of us just leaning into this kind of euphoric, forward-flowing movement in our singing and flying over these crystalline tiny drum and bass breaks that are accompanied by these big Ibiza guitar solos and kind of Nintendo flutes, and finding this place where very detailed electronic music and very pure singing can meet in the middle. And I think it\'s something that, it\'s a kind of feeling that all of us have done different versions of in our music and now we get to together.” **“Blood and Butter”** “This was written as a bit of a challenge between me and Danny L Harle where we tried to contain an entire song to two chords, which of course we do fail at, but only just. It’s a pastoral, it\'s a psychedelic folk song. It imagines itself set in England in the summer, in June. It\'s also a love letter to a lot of the music I listened to growing up—these very trance-like, mantra-like songs, like Donna Lewis’ ‘I Love You Always Forever,’ a lot of Madonna’s *Ray of Light* album, Savage Garden—that really pulsing, tantric electronic music that has a quite sweet and folksy edge to it. The solo is played by a hugely talented and brilliant bagpipe player named Brighde Chaimbeul, whose album *The Reeling* I\'d found in 2022 and became quite obsessed with.” **“Hopedrunk Everasking”** “I couldn\'t really decide if this song needed to be about death or about being deeply, deeply in love. I then had this revelation around the idea of tunneling, this idea of retreating into the tunnel, which I think I feel sometimes when I\'m very deeply in love. The feeling of wanting to retreat from the rest of the world and block the whole rest of the world out just to be around someone and go into this place that only they and I know. And then simultaneously in my very few relationships with losing someone, I did feel some this sense of retreat, of someone going into their own body and away from the world. And the song feels so deeply primal to me. The melody and chords of it were written with Danny L Harle, ironically during the Dua Lipa tour—when I had never been in more of a pop atmosphere in my entire life.” **“Butterfly Net”** “‘Butterfly Net’ is maybe the most narrative storyteller moment on the whole album. And also, palette-wise, deviates from the more hybrid electronic palette that we\'ve been in to go fully into this 1960s drum reverb band atmosphere. I\'m playing an organ solo. I was listening to a lot of ’60s Italian music, and the way they use reverbs as a holder of the voice and space and very minimal arrangements to such incredible effect. It\'s set in three parts, which was somewhat inspired by this triptych of songs called ‘Chansons de Bilitis’ by Claude Debussy that I had learned to sing with my opera teacher. I really liked that structure of the finding someone falling in love, the deepening of it, and then the tragedy at the end. It uses the metaphor of the butterfly net to speak about the inability to keep memories, to keep love, to keep the feeling of someone\'s presence. The children\'s choir \[London\'s Trinity Choir\] we hear on ‘Billions’ comes in again—they get their beautiful feature at the end where their voices actually become the stand-in for the light of the world being onto me.” **“Smoke”** “It was, most importantly, the first song for the album written with a breakbeat, which inspired me to carry on down that path. It’s about catharsis. The opening line is about pretending that something isn\'t catastrophic when it obviously is. It\'s about denial. It\'s about pretending that the situation or your feelings for someone aren\'t tectonic, but of course they are. And then, of course, in the chorus, everything pours right out. But tonally it feels like I\'m at home base with ‘Smoke.’ It has links to songs like \[2019’s\] ‘Pang,’ which, for me, have this windswept feeling of being quite out of control, but are also very soulful and carried by the music. We\'re getting a much more nocturnal, clattery, chaotic picture.” **“Billions”** “‘Billions’ is last for all the same reasons that \'Welcome to My Island’ is first. It dissolves into total selflessness, whereas the album opens with total selfishness. The Beach Boys’ ‘Surf’s Up’ is one of my favorite songs of all time. I cannot listen to it without sobbing. But the nonlinear, spiritual, tumbling, open quality of that song was something that I wanted to bring into the song. But \'Billions\' is really about pure sensuality, about all agenda falling away and just the gorgeous sensuality of existing in this world that\'s so full of abundance, and so full of contradictions, humor, and eroticism. It’s a cheeky sailboat trip through all these feelings. You know that feeling of when you\'re driving a car to the beach, that first moment when you turn the corner and see the ocean spreading out in front of you? That\'s what I wanted the ending of this album to feel like: The song goes very quiet all of a sudden, and then you see the water and the children\'s choir comes in.”

After winning an Oscar (for scoring Pixar’s *Soul*) and five Grammys (four for his triumphant 2021 album, *WE ARE*), and leaving behind his day job as the bandleader on *The Late Show With Stephen Colbert*, Jon Batiste was itching to find a new frequency. And so, he tuned in, turned on, and went to Shangri-La, literally: the Malibu compound that legendary producer Rick Rubin lent him to record *World Music Radio*. “Shangri-La felt like the first stop of what this journey should be,” the singer and multi-instrumentalist tells Apple Music of the genre-bending 21-track collection, a bold but seamless tapestry that features guests ranging from Lana Del Rey and his fellow New Orleans native Lil Wayne to rising K-pop stars NewJeans and sax god Kenny G. It’s all overseen by a cosmic disc jockey of Batiste’s own creation called Billy Bob Bo Bob, a character he describes as “this DJ-storyteller griot who has traveled around the universe to search for what he calls ‘the vibe’”—a spiritual wavelength. “It’s a vibrational frequency of time and space coming together to create bliss and inspiration and purpose,” Batiste says. “And those who know how to tap into that signal, it transports them to this region of the universe that no scientist has been able to detect or find the origin of.” Here, the artist provides the creative inspirations behind the album’s many sonic highlights—some interstellar, others much closer to home. **“Raindance” (feat. Native Soul)** “It’s trap, it’s reggae, and it has an orchestral influence mixed with indigenous Native American chants. I went to the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota and found an incredible group of artists who are Native, and they showed me their traditions of drumming and singing and all of these incredible ideas about life and spirituality that are just a part of their generation’s long-sacred rituals and traditions.” **“Be Who You Are” (feat. JID, NewJeans & Camilo)** “One of the things that Billy Bob does is he takes moments that are happening in the present and, just as a DJ would, he may blend in an interpolation or a nod to a song that is on wax from the past. He’ll even sometimes bend time and space and take a performance that’s happened in the future. This song exemplifies that to a T, where you have echoes of ‘Pass the Dutchie,’ you have this K-pop section, then you have Camilo from Colombia coming in on the horns, and JID is rapping, and then I have my verse and *I’m* rapping. It’s a mission statement—I wouldn’t call it the deepest, but it’s the most banner track of what *World Music Radio* is all about.” **“Worship”** “We wanted to create an experience that brought you to a sense of real perspective and appreciation of your own humanity and the collective of humanity. When you hear these lyrics over and over again as the chords swell, and the synthesizers are crafted in this way that feels like samba-slash-Swedish House Mafia, something about both of those sounds together is catharsis. It creates a release in people when you’re collected in a community, whether it’s at a festival or at a game at a stadium.” **“My Heart” (feat. Rita Payés)** “Rita is a trombonist and singer from Catalonia, an unsigned artist in her early twenties who’s been playing and composing her own music. I was lucky enough to discover her online, and when we connected to write this song, I wanted to sing in the Catalonian dialect of Spanish to bring a certain feeling to the piece. It was already going to be an intimate and beautiful composition, but when we decided to put it in her native language, it really channeled something. Languages just have this ability to speak to art in different ways.” **“Clair de Lune” (feat. Kenny G)** “Kenny G is probably still the most acclaimed, or at least the most commercially successful, instrumental artist of all time. And on *World Music Radio*, we have several different languages and several different kinds of vocalists, but I was thinking, ‘Who is an instrumentalist who has reached cultures around the world in a really profound way?’ I’d put Kenny G on the top five of that list. And it’s crazy because he’s got so many people who hate him! But just getting to know him through this process, you see that it’s not a gimmick for him. And when you listen to him here, he plays in a way that he doesn’t play on any of his other records. He really stretches, you know? And I loved hearing him do that.” **“Butterfly”** “I really am proud of this one, of how transcending of any genre or any sort of classification it is. There’s a lot of textures and sonics and a very maximalist approach in a lot of the music here, but this is transcendent and simple. You can sing it as a nursery rhyme. You can sing it as a lullaby. You sing it as a ballad. I’ve heard kids sing it when we did a workshop at a school; it just has some timeless quality to it. But it’s a personal song for me, in my life as well, that was part of the inspiration—my wife \[journalist Suleika Jaouad, who recently survived a second bout with leukemia\] and particularly our relationship.” **“Uneasy” (feat. Lil Wayne)** “Wayne! That is \[area code\] 504 representing. You know, the 17th Ward where he hails from, I partially grew up there. He’s a little older than me, but we were in that neighborhood three minutes apart from each other, probably around the same time. And together with the ‘17th Ward Prelude,’ which leads into ‘Uneasy,’ this is definitely the most New Orleans segment of the record.” **“CALL NOW (504-305-8269)” (feat. Michael Batiste)** “Who do you get when you call? You get Billy Bob Bo Bob, the real number. And sometimes you get Jon Batiste.” **“MOVEMENT 18’ (Heroes)”** “When you let the subconscious mind, the nonlinear mind, be heard through the frequency of the radio station, what would it sound like? Those are my thoughts coming up and my ruminations on things some of my musical heroes have said to me. You got Wayne Shorter in there. You got Alvin Batiste and Quincy Jones and Duke Ellington. The Wayne sound that you hear is him actually playing with me, and it’s layered on top of the piano that I’m playing on the track.” **“Master Power”** “There’s a few radical choices in here with the sampling. If you study different calls to prayer, you’ll hear sounds from the Muslim traditions of prayer, and then also a Jewish cantor singing as well. Then there’s these biblical references in the lyrics, and it’s just very much a real amalgam of different forms of folk-slash-spiritual music. You dig?” **“Goodbye, Billy Bob”**/**“White Space”** “‘Goodbye, Billy Bob’ is what you’ll hear when a disc jockey on the radio is signing off, and ‘White Space’ is this last-call moment, this sort of lifting into the clouds and beyond, which is where Billy Bob is going. He’s leaving this experience that he’s curated through vibrations that he’s gathered from the planet Earth. He’s floating away.” **“Wherever You Are”** “If ‘Goodbye, Billy Bob’ is the end of the movie and ‘White Space’ is the last scene, then ‘Wherever You Are’ is when the credits roll. You have this emotional moment as you process all that just happened. You take it in, and you listen, and you hear the spacecraft taking off. ‘Is the mothership going up into orbit?’ Then you’re going on to whatever the next destination is.” **“Life Lesson” (feat. Lana Del Rey)** “Lana was in the process of finishing her album, and I was starting mine. She had come by to hang at Shangri-La, and we didn’t really have a plan of creating, but when we played each other some of our music, it was decided that I would help her to finish her record. So, that was the same time that we did ‘Candy Necklace.’ ‘Life Lesson’ wasn’t even intended to be on this album, but it felt as the movie took shape, this was the perfect bonus, the spiritual cousin of the things I was talking about. And I love that it was so organic. It was just one thing that we did amongst many other things that people haven’t even heard yet.”

Lana Del Rey has mastered the art of carefully constructed, high-concept alt-pop records that bask in—and steadily amplify—her own mythology; with each album we become more enamored by, and yet less sure of, who she is. This is, of course, part of her magic and the source of much of her artistic power. Her records bid you to worry less about parsing fact from fiction and, instead, free-fall into her theatrical aesthetic—a mix of gloomy Americana, Laurel Canyon nostalgia, and Hollywood noir that was once dismissed as calculation and is now revered as performance art. Up until now, these slippery, surrealist albums have made it difficult to separate artist from art. But on her introspective ninth album, something seems to shift: She appears to let us in a little. She appears to let down her guard. The opening track is called “The Grants”—a nod to her actual family name. Through unusually revealing, stream-of-conscious songs that feel like the most poetic voice notes you’ve ever heard, she chastises her siblings, wonders about marriage, and imagines what might come with motherhood and midlife. “Do you want children?/Do you wanna marry me?” she sings on “Sweet.” “Do you wanna run marathons in Long Beach by the sea?” This is relatively new lyrical territory for Del Rey, who has generally tended to steer around personal details, and the songs themselves feel looser and more off-the-cuff (they were mostly produced with longtime collaborator Jack Antonoff). It could be that Lana has finally decided to start peeling back a few layers, but for an artist whose entire catalog is rooted in clever imagery, it’s best to leave room for imagination. The only clue might be in the album’s single piece of promo, a now-infamous billboard in Tulsa, Oklahoma, her ex-boyfriend’s hometown. She settled the point fairly quickly on Instagram. “It’s personal,” she wrote.

A decade into their career, London duo Jungle is determined to make up for lost time. Josh Lloyd-Watson and Tom McFarland felt that they’d taken too long to follow up 2014’s self-titled Mercury-nominated debut, with second album *For Ever* arriving four years later. It injected their third album *Loving in Stereo*, released in 2021, with a creative restlessness, and that thrilling urgency continues on *Volcano*. “We’d just come off the road and went straight back into the studio,” Lloyd-Watson tells Apple Music. “We got the record done between November and December 2022 and wrapped it up in January, which is one of the quickest turnarounds we’ve done. You can feel that in the music.” It’s a record that both sharpens the pair’s melodic hooks and hones their nu-disco, soulful pop swagger—pushing them further away from being a band and deeper into how they’ve always imagined themselves. “It’s going back to what is essentially a production duo,” says Lloyd-Watson. “It’s a collective—we wouldn’t be where we are without the dancers, without the incredible vocalists, without all the people that come together to make the full thing. But ultimately, it feels like bits of it are heading much more towards something like Justice or Daft Punk, more dance-y.” Exploring themes of love found, loss, heartbreak, and rediscovery, *Volcano* is also a record that insists you move to its rhythm. This is Jungle at their most vibrant and infectious. Lloyd-Watson talks us through it, track by track. **“Us Against the World”** “This starts in almost chaotic fashion. I think we like that because it bamboozles you a little bit and you can’t really work out what’s going on. It’s frantic and a bit crazy and then it settles in and takes a while to find some solid harmony that Jungle would be known for. We’re embedded deep in harmony. It’s like a breakbeat track, a little bit on edge. I suppose the track can be taken as, ‘We’re about to climb this mountain together, this volcano.’ It’s a setting-off track. It’s us against the world.” **“Holding On”** “This is one that wasn’t necessarily made for Jungle, we made it with \[Dublin DJ/producer\] Krystal Klear and \[Essex singer-songwriter/producer\] Lydia Kitto. It has a much more clubby touch to it, it’s got heavier kicks and it’s got 909 hats, which we’ve never really used. It continues that more aggy side of what we wanted to do, we wanted to have a bit more of the disco-punk element to it, à la \[the South Bronx’s early-’80s punk-funk pioneers\] ESG, something that was anti the soft, midtempo Jungle that we know and love. It’s a bit strobe-y and then eventually it releases to this refrain, which sounds like some old soul sample that we made. I suppose it’s the first time you’re like, ‘OK, this is a Jungle record. I know what’s going on here.’” **“Candle Flame” (feat. Erick the Architect)** “Track three has always been the big one for us—\[2014 breakthrough hit\] ‘Busy Earnin’’ was track three \[on their debut album\]. We had this hook for a long time. It had been sitting at 104 BPM and we eventually got a bit bored of it down at that tempo and ramped it up so you get those sped-up, soul-pitched vocals. We wanted to have something that was really fun and carefree and had this atmosphere of a party. I think ‘Candle Flame’ is about the fire and the passion in early love, essentially. Erick the Architect, of Flatbush Zombies fame, jumped on it and did a verse which reminded me of a young Snoop Dogg. It had that fiery energy and just set the thing on fire really…like a candle flame!” **“Dominoes”** “‘Dominoes’ is another song that had this old soul vibe—it was a lot slower originally, it was down at 85 BPM. ‘Dominoes’ is a metaphor for falling in love and the cataclysmic events that happen as you adapt to being deeper and deeper in love and you change your whole life. It has a sample of the \[US R&B singer\] Gloria Ann Taylor song ‘Love Is a Hurtin’ Thing,’ which we took and then mixed with the vocals of our song, like this mashup thing. It’s got this cruising, The Avalanches vibe, a real summer jam. I suppose it’s the first time in the album when you get a little bit of respite and it’s not so explosive.” **“I’ve Been in Love” (feat. Channel Tres)** “This features Channel Tres and is from a session that we did a while back—basically before Channel Tres was even established as an artist. We wrote this over another song which was called ‘I’m Dying to Be in Your Arms,’ which you can hear in the middle of ‘I’ve Been in Love.’ We resampled the original track that he was on, which forms the middle eight. It tells the story of love past and the idea of coming out of that love.” **“Back on 74”** “The feeling of ‘Back on 74’ is a nostalgic one, it’s that feeling of having this place of your life where you grew up, where you had these really fond memories. 74 is a fictitious thing, but for us it’s like 74th Avenue or 74th Street or something, where, in your imagination or as a kid, you were playing out on the street. You’ve gone back to this place and it’s giving you this really nostalgic feeling but everything’s not quite the same. You’ve come out of something on ‘I’ve Been in Love’ and through ‘Back on 74,’ you have this desire to go home, back to a place that felt safe.” **“You Ain’t No Celebrity” (feat. Roots Manuva)** “This is probably the most raw and honest track on the record, a warning to people in your life that think they’re a bit of a princess or a bit of a diva—when they become demanding or a little bit self-righteous or a little bit expectant of certain things to fall their way. Roots Manuva was maybe relating to that feeling. He had these lyrics which were originally on another track, something we did with him way back in 2016 or something. He had these almost like nursery-rhyme, Mr Motivator-style hooks that weren’t even a verse, almost like this mantra. It explains the compromise that you have to have in a relationship with somebody, the push and pull, over easy and easy over, a constant back and forth.” **“Coming Back”** “This is a continuation of ‘You Ain’t No Celebrity’ but it’s a little bit more of a celebration. It takes the resentment and the anger and turns it into this more cheeky, throwaway, carnival vibe. It starts off with these shouted vocals, like, ‘I don’t miss you,’ these realizations about yourself, and the chorus goes on to say you keep coming back for more—once you’ve let go of somebody, somebody keeps wanting more from you. It explores the idea of expectation in relationships, but we end up with this almost carnival ending where everybody’s joining in, getting through it through fun.” **“Don’t Play” (feat. Mood Talk)** “‘Don’t Play’ is a sample from ‘Faith Is the Key,’ a really rare record by Enlightment, a Washington soul and gospel outfit. They put this record out in ’84 but then the record plant basically went under and their distributor went under, which made this record quite valuable, a holy grail for collectors. It surfaced again in 2000 and now copies are going for about £800. It had this amazing little hook in it and my cousin, who is Mood Talk, put this beat together and sampled it. We featured him on the record and we sang over the sample. ‘Don’t Play’ is, ‘Stop playing these games, I’m not bothered.’ That message can be applied at the beginning and it can be applied at the end of a relationship. There are always games on the in and the out…” **“Every Night”** “This is fun and guitar-based. We really wanted to make a song without a snare drum. It’s a fun song, a positive message about love, and it’s got gospel influences to some extent. It’s a bit of a party.” **“PROBLEMZ”** “This came out originally in 2022 and I suppose in some way, with \[its double A-side\] ‘GOOD TIMES,’ was the blueprint for the sound of the record. We left ‘GOOD TIMES’ off the record because it didn’t feel like it was right, it didn’t really feel like the production or the vibe was quite where this record was. But ‘PROBLEMZ’ is one of our favorite bits of music we’ve ever made and we didn’t want to leave it as some B-side. It’s got Latin American vibes and feels to it, especially in the flutes and the swing of the music, a classic disco feel. At the end, it goes to this place that’s almost like musical theater with the strings.” **“Good at Breaking Hearts”** “This is the first traditional ballad of the record. It’s like, ‘I’m only good at making mistakes—a bit of a juxtaposition in that you are only good at breaking hearts.’ It features \[London singer-songwriter\] JNR Williams and 33.3—which is mine and Lydia’s new project. JNR has an amazing voice and I’ve been working with him for two or three years, writing loads of songs with him. This is a song that we made for his album but he was like, ‘I don’t want it,’ and then as soon as it was done, he was like, ‘Oh, I wish I’d taken this!’ I said, ‘You should have trusted me, man!’ It’s a beautiful song. His voice has got touches of Nina Simone and Bill Withers and Stevie Wonder to him. He’s got an amazing voice.” **“Palm Trees”** “We made this out in LA originally. It was about this idea that you could escape to this place, like holiday-themed, ‘Here we come, palm trees!’ That feeling of ‘I’m just going to escape this and I want to go somewhere hot and I want to go somewhere where my troubles don’t affect me and I can leave all this stuff behind.’ It’s told through this story of a girl going to a club and taking a drug that sends her on this wild space disco trip.” **“Pretty Little Thing” (feat. Bas)** “This was something that got made in the same chunk of time in which ‘PROBLEMZ’ and ‘GOOD TIMES’ were made, and fans would know that it’s actually on the end of the video for ‘GOOD TIMES/PROBLEMZ’—on the credits we ran a little snippet of ‘Pretty Little Thing.’ It’s a ballad, a chance to reflect on moments and reflect on the old experience. \[Queens-via-Paris rapper\] Bas jumped on this and told his own story, which weirdly made sense of the whole thing anyway. It was serendipity.”

“I feel like there are two sides of me,” says the Nashville-based singer-songwriter and guitar virtuoso known as Sunny War. “One of them is very self-destructive, and the other is trying to work with that other half to keep things balanced.” That’s the central conflict on her fourth album, the eclectic and innovative Anarchist Gospel, which documents a time when it looked like the self-destructive side might win out. Extreme emotions can make that battle all the more perilous, yet from such trials Sunny has crafted a set of songs that draw on a range of ideas and styles, as though she’s marshaling all her forces to get her ideas across: ecstatic gospel, dusty country blues, thoughtful folk, rip-roaring rock and roll, even avant garde studio experiments. She melds them together into a powerful statement of survival, revealing a probing songwriter who indulges no comforting platitudes and a highly innovative guitarist who deploys spidery riffs throughout every song. Because it promises not healing but resilience and perseverance, because it doesn’t take shit for granted, Anarchist Gospel holds up under such intense emotional pressure, acknowledging the pain of living while searching for something that lies just beyond ourselves, some sense of balance between the bad and the good.

“Does anyone even know you?/Does anyone even care?” That’s just one of the many existential questions put forth by The Armed on *Perfect Saviors*. This time around, the multifaceted, multitasking, multicultural, willfully mysterious collective peer through the cracked lens of everyone’s smartphone to examine the cultural chaos, social media narcissism, virtue signaling, and performative blah-blah-blah of our current moment. You know: the Modern Malaise. On songs like “Sport of Measure” and “Sport of Form,” they’re not talking about Monday Night Football or the UFC or even (necessarily) the endless public humiliations of celebrity athletes. No, it’s a much nastier blood sport The Armed are interested in: The daily *Lord of the Flies* competition for likes, followers, and views. They even issued a press release about it: “*Perfect Saviors* is the soundtrack to a single movie with 7.5 billion roles.” According to vocalist and spokesperson Tony Wolski (who may or may not have formerly been known as Adam Vallely), the single “Everything’s Glitter” was inspired by David Bowie’s first US press tour. It looks at what Wolski—who directed the video for the track and co-produced *Perfect Saviors*—calls “the razor’s edge between icon and clown.” The song itself sounds like The Strokes being calmly fed into a Vitamix. So does “Clone,” which appears two songs earlier. Between them is “Modern Vanity,” which sounds like a seasick, drug-induced fantasy headache written by stone-cold teetotalers. Meanwhile, “Liar 2” is a dance track about being hopelessly depressed. Probably. The point here—and on “Modern Vanity,” and elsewhere on *Perfect Saviors*—seems to be the juxtaposition, the pairing of opposites. It’s what The Armed have thrived upon since their inception in 2009 but elevated to an art form on their celebrated 2021 album, *Ultrapop*. In fact, most of *Perfect Saviors* is a seesawing mashup of indie rock, post-hardcore, and strobe-effect electronics, but (usually) without the abrupt stylistic U-turns many of their sonically schizophrenic peers go in for. Toward the end of the record, we get some melancholy sax (“In Heaven”) and a Radiohead-style mood piece complete with free-jazz skronk, sad piano, sadder strings, and a slow fade into oblivion. That one’s called “Public Grieving.” As on the band’s previous outings, *Perfect Saviors* has cameos. But this time, the guest list is more crowded than usual. Featuring appearances from indie darling Julien Baker, avant-garde saxophonist Patrick Shiroishi, and Chavez/ex-Zwan guitarist Matt Sweeney alongside dudes from Jane’s Addiction, Queens of the Stone Age, and Red Hot Chili Peppers—plus too many more to list here—the album is crammed with people from other bands. At the same time, The Armed will put Iggy Pop in one of their videos (“Sport of Form”) without getting him to perform on the song itself. It’s the equivalent of taking a selfie with a rock star whose music you’re not actually familiar with. Which is probably the point.

No band could ever prepare for what the Foo Fighters went through after the death of longtime drummer Taylor Hawkins in March 2022, but in a way, it’s hard to imagine a band that could handle it better. From the beginning, their music captured a sense of perseverance that felt superheroic without losing the workaday quality that made them so approachable and appealing. These were guys you could imagine clocking into the studio with lunchpails and thermoses in hand—a post-grunge AC/DC who grew into rock-pantheon standard-bearers, treating their art not as rarified personal expression but the potential for a universal good time. The mere existence of *But Here We Are*, arriving with relatively little fanfare a mere 15 months after Hawkins’ death, tells you what you need to know: Foo Fighters are a rock band, rock bands make records. That’s just what rock bands do. And while this steadiness has been key to Dave Grohl’s identity and longevity, there is a fire beneath it here that he surely would have preferred to find some other way. Grief presents here in every form—the shock of opening track “Rescued” (“Is this happening now?!”), the melancholy of “Show Me How” (on which Grohl duets with his daughter Violet), the anger of 10-minute centerpiece “The Teacher,” and the fragile acceptance of the almost slowcore finale “Rest.” “Under You” processes all the stages in defiantly jubilant style. And after more than 20 years as one of the most polished arena-rock bands in the world, they play with a rawness that borders on ugly. Just listen to the discord of “The Teacher” or the frayed vocals of the title track or the sweet-and-sour chorus of “Nothing at All,” which sound more like Hüsker Dü or Fugazi than “Learn to Fly.” The temptation is to suggest that trauma forced them back to basics. The reality is that they sound like a band with a lot of life behind them trying to pave the road ahead.

Part of what makes Danny Brown and JPEGMAFIA such a natural pair is that they stick out in similar ways. They’re too weird for the mainstream but too confrontational for the subtle or self-consciously progressive set. And while neither of them would be mistaken for traditionalists, the sample-scrambling chaos of tracks like “Burfict!” and “Shut Yo Bitch Ass Up/Muddy Waters” situate them in a lineage of Black music that runs through the comedic ultraviolence of the Wu-Tang Clan back through the Bomb Squad to Funkadelic, who proved just because you were trippy didn’t mean you couldn’t be militant, too.

With A Hammer is the debut studio album by New York singer-songwriter Yaeji. “With A Hammer” was composed across a two-year period in New York, Seoul, and London, begun shortly after the release of “What We Drew” and during the lockdowns of the Coronavirus pandemic. It is a diaristic ode to self-exploration; the feeling of confronting one’s own emotions, and the transformation that is possible when we’re brave enough to do so. In this case, Yaeji examines her relationship to anger. It is a departure from her previous work, blending elements of trip-hop and rock with her familiar house-influenced style, and dealing with darker, more self-reflective lyrical themes, both in English and Korean. Yaeji also utilizes live instrumentation for the first time on this album—weaving in a patchwork ensemble of live musicians, and incorporating her own guitar playing. “With A Hammer” features electronic producers and close collaborators K Wata and Enayet, and guest vocals from London’s Loraine James and Baltimore’s Nourished by Time.

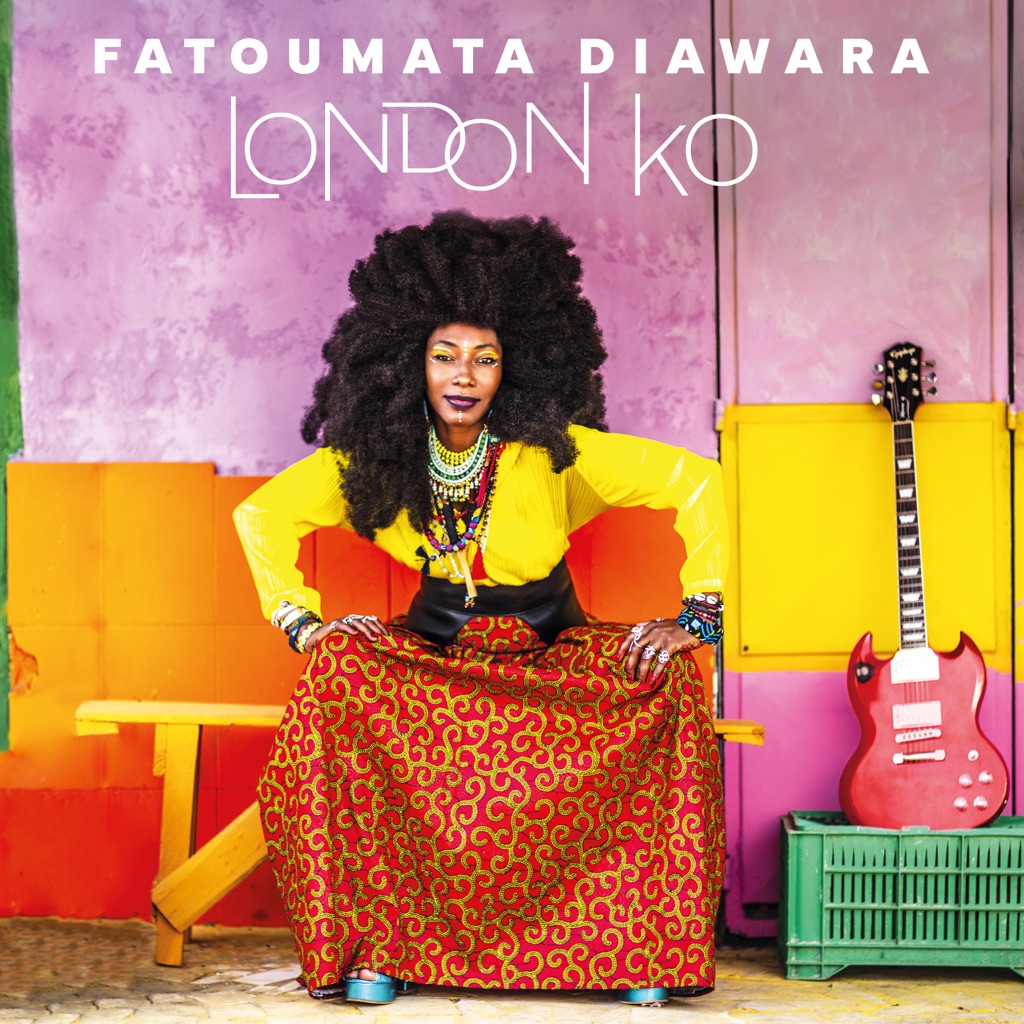

Ivorian-born Malian artist Fatoumata Diawara’s soothing, Grammy-nominated vocals have continued the magic of Malian music traditions since her debut, 2011’s *Fatou*. By staying close to her Wassoulou music style origins, the supremely cool superstar retains her pan-Africanness, but manages to incorporate new influences on her fourth studio album, *London Ko*. On \"Nsera\", shadows of Afrobeat icons Tony Allen and Fela Kuti grease the wheels for their fellow West African, who sings mesmerisingly in Bambara to open the show. English singer-songwriter Damon Albarn features here, while Ghanaian rapper M.anifest appears on “Mogokan”—reuniting Diawara with two of her collaborators from the 2012 Afrobeat album, *Rocket Juice and the Moon*. Elswhere, Cuban jazz pianist Robert Fonseca (”Blues”), African-American vocalist Angie Stone (“Somaw”) and Nigerian songstress Yemi Alade (“Tolon”) complete the clan with assured guest performances. Across the album, experiments with Afrofunk and jazz cement Diawara\'s status as an unmistakable genre-bender whose sound is nearly unclassifiable. But \"Maya\", a soulful ode that evokes memories of *Fatou* as it closes out the album, is a timely reminder that she is undeniable music royalty.

The nearly six-year period Kelela Mizanekristos took between 2017’s *Take Me Apart* and 2023’s *Raven* wasn’t just a break; it was a reckoning. Like a lot of Black Americans, she’d watched the protests following George Floyd’s murder with outrage and cautious curiosity as to whether the winds of social change might actually shift. She read, she watched, she researched; she digested the pressures of creative perfectionism and tireless productivity not as correlatives of an artistic mind but of capitalism and white supremacy, whose consecration of the risk-free bottom line suddenly felt like the arbitrary and invasive force it is. And suddenly, she realized she wasn’t alone. “Internally, I’ve always wished the world would change around me,” Kelela tells Apple Music. “I felt during the uprising and the \[protests of the early 2020s\] that there’s been an *external* shift. We all have more permission to say, ‘I don’t like that.’” Executive-produced by longtime collaborator Asmara (Asma Maroof of Nguzunguzu), 2023’s *Raven* is both an extension of her earlier work and an expansion of it. The hybrids of progressive dance and ’90s-style R&B that made *Take Me Apart* and *Cut 4 Me* compelling are still there (“Contact,” “Missed Call,” both co-produced by LSDXOXO and Bambii), as is her gift for making the ethereal feel embodied and deeply physical (“Enough for Love”). And for all her respect for the modalities of Black American pop music, you can hear the musical curiosity and experiential outliers—as someone who grew up singing jazz standards and played in a punk band—that led her to stretch the paradigms of it, too. But the album’s heart lies in songs like “Holier” and “Raven,” whose narratives of redemption and self-sufficiency jump the track from personal reflections to metaphors for the struggle with patriarchy and racism more broadly. “I’ve been pretty comfortable to talk about the nitty-gritty of relationships,” she says. “But this album contains a few songs that are overtly political, that feel more literally like *no, you will not*.” Oppression comes in many forms, but they all work the same way; *Raven* imagines a flight out.

“As I got older I learned I’m a drinker/Sometimes a drink feels like family,” Mitski confides with disarming honesty on “Bug Like an Angel,” the strummy, slow-build opening salvo from her seventh studio album that also serves as its lead single. Moments later, the song breaks open into its expansive chorus: a convergence of cooed harmonies and acoustic guitar. There’s more cracked-heart vulnerability and sonic contradiction where that came from—no surprise considering that Mitski has become one of the finest practitioners of confessional, deeply textured indie rock. Recorded between studios in Los Angeles and her recently adopted home city of Nashville, *The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We* mostly leaves behind the giddy synth-pop experiments of her last release, 2022’s *Laurel Hell*, for something more intimate and dreamlike: “Buffalo Replaced” dabbles in a domestic poetry of mosquitoes, moonlight, and “fireflies zooming through the yard like highway cars”; the swooning lullaby “Heaven,” drenched in fluttering strings and slide guitar, revels in the heady pleasures of new love. The similarly swaying “I Don’t Like My Mind” pithily explores the daily anxiety of being alive (sometimes you have to eat a whole cake just to get by). The pretty syncopations of “The Deal” build to a thrilling clatter of drums and vocals, while “When Memories Snow” ropes an entire cacophonous orchestra—French horn, woodwinds, cello—into its vivid winter metaphors, and the languid balladry of “My Love Mine All Mine” makes romantic possessiveness sound like a gift. The album’s fuzzed-up closer, “I Love Me After You,” paints a different kind of picture, either postcoital or defiantly post-relationship: “Stride through the house naked/Don’t even care that the curtains are open/Let the darkness see me… How I love me after you.” Mitski has seen the darkness, and on *The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We*, she stares right back into the void.

Having exorcised their fascination with post-punk on 2021’s *Drunk Tank Pink*, shame evolves on their third LP—with an expansive mix of anthems (“Fingers of Steel”), rippers (“Six-Pack,” “Different Person”), and ballads (“All the People,” the Phoebe Bridgers-featuring “Adderall”) that, like the Pixies before them, delivers the twists and abrasions of underground music with the straightforward warmth of classic rock. To note that they wrote most of it in a couple of weeks (and recorded it live in the studio) would sound like a corny bid for the scruffy vitality of rock ’n’ roll, were it not for the fact that you can tell.