The cover art for Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ 17th album couldn’t feel more removed from the man once known as a snarling, terrifying prince of poetic darkness. This heavenly forest with its vibrant flowers, rays of sun, and woodland creatures feels comically opposed to anything Cave has ever represented—but perhaps that’s the point. This pastel fairy tale sets the scene for *Ghosteen*, his most minimalist, supernatural work to date, in which he slips between realms of fantasy and reality as a means to accept life and death, his past and future. In his very first post on The Red Hand Files—the website Cave uses to receive and respond to fan letters—he spoke of rebuilding his relationship with songwriting, which had been damaged while enduring the grief that followed his son Arthur’s death in 2015. He wrote, “I found with some practise the imagination could propel itself beyond the personal into a state of wonder. In doing so the colour came back to things with a renewed intensity and the world seemed clear and bright and new.” It is within that state of wonder that *Ghosteen* exists. “The songs on the first album are the children. The songs on the second album are their parents,” Cave has explained. Those eight “children” are misty, ambient stories of flaming mares, enchanted forests, flying ships, and the eponymous, beloved Ghosteen, described as a “migrating spirit.” The second album features two longer pieces, connected by the spoken-word “Fireflies.” He tells fantasy stories that allude to love and loss and letting go, and occasionally brings us back to reality with detailed memories of car rides to the beach and hotel rooms on rainy days. These themes aren’t especially new, but the feeling of this album is. There are no wild murder ballads or raucous, bluesy love songs. Though often melancholy, it doesn’t possess the absolute devastation and loneliness of 2016’s *Skeleton Tree*. Rather, these vignettes and symbolic myths are tranquil and gentle, much like the instrumentation behind them. With little more than synths and piano behind Cave’s vocals, *Ghosteen* might feel uneventful at times, but the calmness seems to help his imagination run free. On “Bright Horses,” he sings of “Horses broken free from the fields/They are horses of love, their manes full of fire.” But then he pulls back the curtain and admits, “We’re all so sick and tired of seeing things as they are/Horses are just horses and their manes aren’t full of fire/The fields are just fields, and there ain’t no lord… This world is plain to see, it don’t mean we can’t believe in something.” Through these dreamlike, surreal stories, Cave is finding his path to peace. And he’s learned that he isn’t alone on his journey. On “Galleon Ship,” he begins, “If I could sail a galleon ship, a long, lonely ride across the sky,” before realizing: “We are not alone, it seems, so many riders in the sky/The winds of longing in their sails, searching for the other side.”

Few songwriters have Bill Callahan’s eye for wry detail: “Like motel curtains, we never really met,” the singer-songwriter declares on “Angela,” using his weather-worn baritone. On his first studio album in five years—an unusually long gap for Callahan—one of the enduring voices in alternative music continues to pare back the extraneous in his sound. A noise musician and mighty mumbler when he broke through under the moniker of Smog in the early 1990s, Callahan now favors minimal indie-folk brushstrokes such as a guitar strum, a sighing pedal steel guitar, or simply barely audible room ambience. The 20 songs here insinuate themselves with bittersweet melodies and a conversational tone, and they’re a strong reminder of Callahan\'s dry sense of humor: “The panic room is now a nursery,” the recently married new father sings on “Son of the Sea.” But if he’s comparatively settled in life, Callahan still knows how to hit an unnerving note with a matter-of-fact ease.

The voice murmuring in our ear, with shaggy-dog and other kinds of stories, is an old friend we're so glad to hear again. Bill’s gentle, spacey take on folk and roots music is like no other; scraps of imagery, melody and instrumentation tumble suddenly together in moments of true human encounters.

It\'s hard to imagine Bruce Springsteen describing a project of his as a concept album—too much prog baggage, too much expectation of some big, grand, overarching *story*. But nothing he\'s done across five decades as one of rock\'s most accomplished storytellers has had the singular, specific focus and locus, lyrically and musically, as this long-gestating solo effort—a lush meditation on the landscape of the western United States and the people who are drawn there, or got stuck there. Neither a bare-bones acoustic effort like *Nebraska* nor a fully tricked-out E Street Band affair, this set of 13 largely subdued character-driven songs (his first new ones since 2014\'s *High Hopes*, following five years immersed in memoir) is ornamented with strings and horns and slide guitar and banjo that sound both dusty and Dusty. They trade in the most familiar of American iconography—trains, hitchhikers, motels, sunsets, diners, Hollywood, and, of course, wild horses—but aren\'t necessarily antiquated; the clichés are jumping-off points, aiming for timelessness as much as nostalgia. The battered stuntman of “Drive Fast” could be licking, and cataloging, his wounds in 1959 or 2019. As convulsive and pivotal as the current moment may feel, restlessness and aimlessness and disenfranchisement are evergreen, and the songs are built to feel that way. In true Springsteen fashion, the personal is elevated to the mythical.

The title of this group’s second album may suggest a mystical journey, but what you hear across these nine tracks is a thrilling and direct collaboration that speaks to the mastery of the individual members: London jazz supremo Shabaka Hutchings delivers commanding saxophone parts, keyboardist Dan Leavers supplies immersive electronic textures, and drummer Max Hallett provides a welter of galvanizing rhythms. The trio records under pseudonyms—“King Shabaka,” “Danalogue,” and “Betamax” respectively—and that fantastical edge is also part of their music, which looks to update the cosmic jazz legacy of 1970s outliers such as Alice Coltrane and Sun Ra. With the only vocals a spoken-word poem on the grinding “Blood of the Past,” the lead is easily taken by Hutchings’ urgent riffs. Tracks such as “Summon the Fire” have a delirious velocity that builds and peaks repeatedly, while the skittering beat on “Super Zodiac” imports the production techniques of Britain’s grime scene. There’s a science-fiction sheen to slower jams like “Astral Flying,” which makes sense—this is evocative time-travel music, after all. Even as you pick out the reference points, which also include drum \'n\' bass and psychedelic rock, they all interlock to chart a sound for the future.

In some ways, Aldous Harding’s third album, *Designer*, feels lighter than her first two—particularly 2017’s stunning, stripped-back, despairing *Party*. “I felt freed up,” Harding (whose real name is Hannah) tells Apple Music. “I could feel a loosening of tension, a different way of expressing my thought processes. There was a joyful loosening in an unapologetic way. I didn’t try to fight that.” Where *Party* kept the New Zealand singer-songwriter\'s voice almost constantly exposed and bare, here there’s more going on: a greater variety of instruments (especially percussion), bigger rhythms, additional vocals that add harmonies and echoes to her chameleonic voice, which flips between breathy baritone and wispy falsetto. “I wanted to show that there are lots of ways to work with space, lots of ways you can be serious,” she says. “You don’t have to be serious to be serious. I’m not a role model, that’s just how I felt. It’s a light, unapologetic approach based on what I have and what I know and what I think I know.” Harding attributes this broader musical palette to the many places and settings in which the album was written, including on tour. “It’s an incredibly diverse record, but it somehow feels part of the same brand,” she says. “They were all written at very different times and in very different surroundings, but maybe that’s what makes it feel complete.” The bare, devastating “Heaven Is Empty” came together on a long train ride and “The Barrel” on a bike ride, while intimate album closer “Pilot” took all of ten minutes to compose. “It was stream of consciousness, and I don’t usually write like that,” she says. “Once I’d written it all down, I think I made one or two changes to the last verse, but other than that, I did not edit that stream of consciousness at all.” The piano line that anchors “Damn” is rudimentary, for good reason: “I’m terrible at piano,” she says. “But it was an experiment, too. I’m aware that it’s simple and long, and when you stretch out simple it can be boring. It may be one of the songs people skip over, but that’s what I wanted to do.” The track is, as she says, a “very honest self-portrait about the woman who, I expect, can be quite difficult to love at times. But there’s a lot of humor in it—to me, anyway.”

Aldous Harding’s third album, Designer is released on 26th April and finds the New Zealander hitting her creative stride. After the sleeper success of Party (internationally lauded and crowned Rough Trade Shop’s Album of 2017), Harding came off a 200-date tour last summer and went straight into the studio with a collection of songs written on the road. Reuniting with John Parish, producer of Party, Harding spent 15 days recording and 10 days mixing at Rockfield Studios, Monmouth and Bristol’s J&J Studio and Playpen. From the bold strokes of opening track ‘Fixture Picture’, there is an overriding sense of an artist confident in their work, with contributions from Huw Evans (H. Hawkline), Stephen Black (Sweet Baboo), drummer Gwion Llewelyn and violinist Clare Mactaggart broadening and complimenting Harding’s rich and timeless songwriting.

A raw and scintillating state-of-Dublin address.

Part of the fun of listening to Lana Del Rey’s ethereal lullabies is the sly sense of humor that brings them back down to earth. Tucked inside her dreamscapes about Hollywood and the Hamptons are reminders—and celebrations—of just how empty these places can be. Here, on her sixth album, she fixes her gaze on another place primed for exploration: the art world. Winking and vivid, *Norman F\*\*\*\*\*g Rockwell!* is a conceptual riff on the rules that govern integrity and authenticity from an artist who has made a career out of breaking them. In a 2018 interview with Apple Music\'s Zane Lowe, Del Rey said working with songwriter Jack Antonoff (who produced the album along with Rick Nowels and Andrew Watt) put her in a lighter mood: “He was so *funny*,” she said. Their partnership—as seen on the title track, a study of inflated egos—allowed her to take her subjects less seriously. \"It\'s about this guy who is such a genius artist, but he thinks he’s the shit and he knows it,” she said. \"So often I end up with these creative types. They just go on and on about themselves and I\'m like, \'Yeah, yeah.\' But there’s merit to it also—they are so good.” This paradox becomes a theme on *Rockwell*, a canvas upon which she paints with sincerity and satire and challenges you to spot the difference. (On “The Next Best American Record,” she sings, “We were so obsessed with writing the next best American record/’Cause we were just that good/It was just that good.”) Whether she’s wistfully nostalgic or jaded and detached is up for interpretation—really, everything is. The album’s finale, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have - but I have it,” is packaged like a confessional—first-person, reflective, sung over simple piano chords—but it’s also flamboyantly cinematic, interweaving references to Sylvia Plath and Slim Aarons with anecdotes from Del Rey\'s own life to make us question, again, what\'s real. When she repeats the phrase “a woman like me,” it feels like a taunt; she’s spent the last decade mixing personas—outcast and pop idol, debutante and witch, pinup girl and poet, sinner and saint—ostensibly in an effort to render them all moot. Here, she suggests something even bolder: that the only thing more dangerous than a complicated woman is one who refuses to give up.

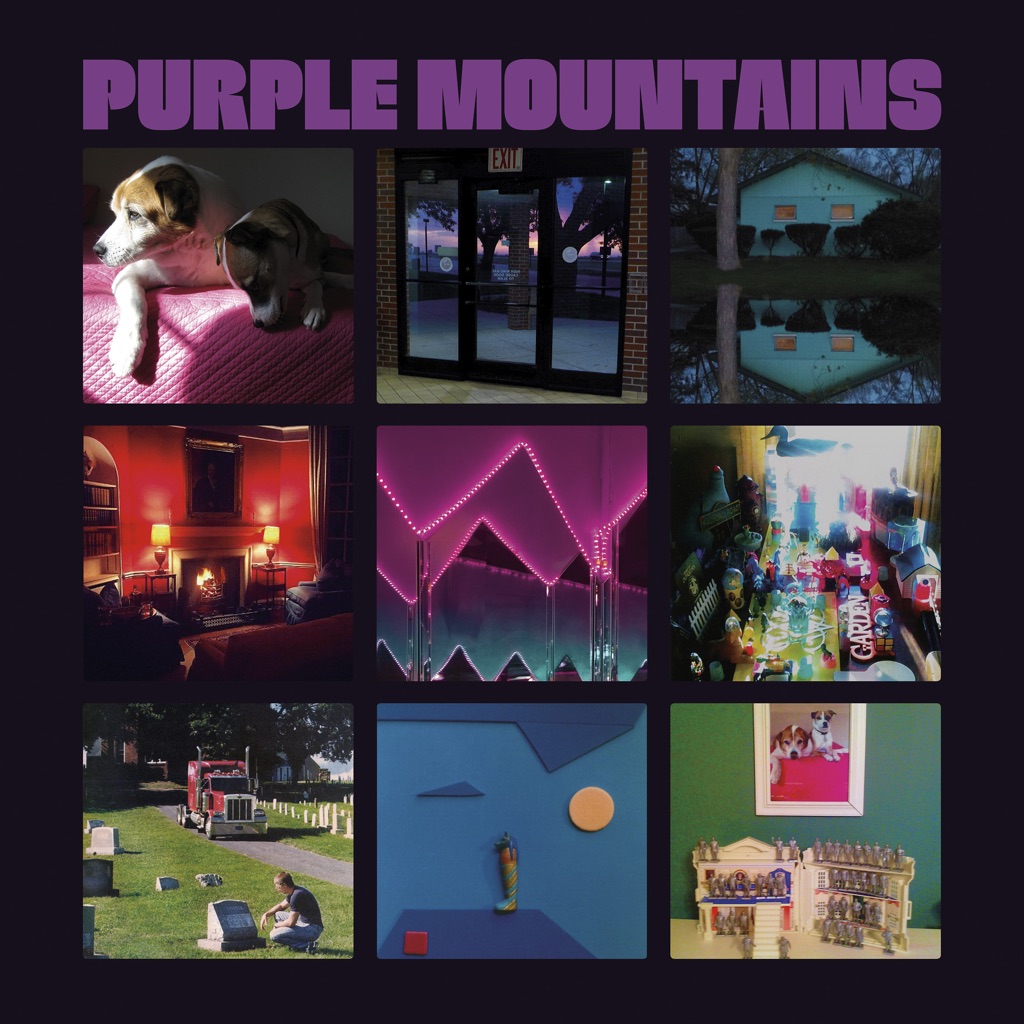

When David Berman disbanded Silver Jews in 2009, the world stood to lose one of the best writers in indie rock, a guy who catalogued the magic and misery of everyday life with wit, heart, and the ragged glory of the occupationally down-and-out. After a 10-year break professedly spent reading books and arguing with people on Reddit, Berman enlisted members of the Brooklyn band Woods to back him on *Purple Mountains*. Berman’s pain had never been laid quite so bare, nor had it ever sounded quite so urgent. “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion,” he sings on the swaggering “That’s Just the Way I Feel.” “Day to day, I’m neck and neck with giving in.” And “Margaritas at the Mall” turns an ordinary happy hour into a jeremiad about the cold comforts of capitalism in a godless world. That the music—country-tinged indie rock—was as polished and competent as it was only highlighted Berman’s intensity: less a rock singer than a street preacher, someone who needed to avail himself of his visions stat. But even at his most desperate, he remained achingly funny, turning statements of existential loneliness into the kind of bumper sticker Zen that made him seem like an ordinary guy no matter how highfalutin he could get. “Well, if no one’s fond of fuckin’ me, maybe no one’s fuckin’ fond of me,” he sings on the album-closing “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” sounding not all that far off from the George Strait one-twos he reportedly loved. Above all, though, his writing is beautiful, attuned to detail in ways that make ordinary scenarios shimmer with quiet magic. Just listen to “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan,” which turns a quiet night in a big city into an allegory of finding solace in the weather of what comes to us. Shortly after the release of *Purple Mountains*, Berman died, at the age of 52, a tragic end to what felt like a triumphant return. “The dead know what they\'re doing when they leave this world behind,” he sings on “Nights That Won’t Happen.” “When the here and the hereafter momentarily align.”

David Berman comes in from the cold after ten long years. His new musical expression is a meltdown unparalleled in modern memory. He warns us that his findings might be candid, but as long as his punishment comes in such bite-sized delights of all-American jukebox fare, we'll hike the Purple Mountains with pleasure forever.

The mighty upsetter returns with 9 brand new tracks recorded with longtime friend and collaborator Adrian Sherwood at the controls. “It's the most intimate album Lee has ever made, but at the same time the musical ideas are very fresh. I'm extremely proud of what we've come up as a piece of work". - A.M.S This new set is the culmination of over two years work and recording sessions that span Jamaica, Brazil and the UK. Determined to craft a work of lasting power, Sherwood likens to the album to the work that Rick Rubin did with Johnny Cash on the American Recordings series, a deeply personal work (the album title refers to Lee’s birth name) and arguably the strongest batch of original material that Perry has released for many years. From the atmospheric field recording and wah-wah guitar of album opener “Cricket On The Moon”, to the gothic cello embellishment on “Let It Rain”, the chopped-and-compressed horn section of “Makumba Rock”, to the layered, carefully arranged backing vocals like a heavenly chorus throughout the record, this is an album with true love, care and attention poured into it’s every groove. It culminates in the truly extraordinary “Autobiography Of The Upsetter”, in which Scratch narrates the story of his life from growing up on a plantation in 1930s colonial Jamaica to becoming a worldwide musical superstar. The story of Lee Perry and Adrian Sherwood collaborating stretches back to the mid-1980s, and a fortuitous meeting brokered by underground broadcasting legend Steve Barker between the dub innovator and UK upstart. This led to the creation of On-U classics such as Time Boom X De Devil Dead and The Mighty Upsetter, as well as Lee gracing Dub Syndicate records with some vital vocal injections. N.B Please order 'pre-order' items separately from other items, otherwise your in-stock items won't be shipped until the pre-order release date.

JAIME I wrote this record as a process of healing. Every song, I confront something within me or beyond me. Things that are hard or impossible to change, words and music to describe what I’m not good at conveying to those I love, or a name that hurts to be said: Jaime. I dedicated the title of this record to my sister who passed away as a teenager. She was a musician too. I did this so her name would no longer bring me memories of sadness and as a way to thank her for passing on to me everything she loved: music, art, creativity. But, the record is not about her. It’s about me. It’s not as veiled as work I have done before. I’m pretty candid about myself and who I am and what I believe. Which, is why I needed to do it on my own. I wrote and arranged a lot of these songs on my laptop using Logic. Shawn Everett helped me make them worthy of listening to and players like Nate Smith, Robert Glasper, Zac Cockrell, Lloyd Buchanan, Lavinia Meijer, Paul Horton, Rob Moose and Larry Goldings provided the musicianship that was needed to share them with you. Some songs on this record are years old that were just sitting on my laptop, forgotten, waiting to come to life. Some of them I wrote in a tiny green house in Topanga, CA during a heatwave. I was inspired by traveling across the United States. I saw many beautiful things and many heartbreaking things: poverty, loneliness, discouraged people, empty and poor towns. And of course the great swathes of natural, untouched lands. Huge pink mountains, seemingly endless lakes, soaring redwoods and yellow plains that stretch for thousands of acres. There were these long moments of silence in the car when I could sit and reflect. I wondered what it was I wanted for myself next. I suppose all I want is to help others feel a bit better about being. All I can offer are my own stories in hopes of not only being seen and understood, but also to learn to love my own self as if it were an act of resistance. Resisting that annoying voice that exists in all of our heads that says we aren’t good enough, talented enough, beautiful enough, thin enough, rich enough or successful enough. The voice that amplifies when we turn on our TVs or scroll on our phones. It’s empowering to me to see someone be unapologetically themselves when they don’t fit within those images. That’s what I want for myself next and that’s why I share with you, “Jaime”. Brittany Howard

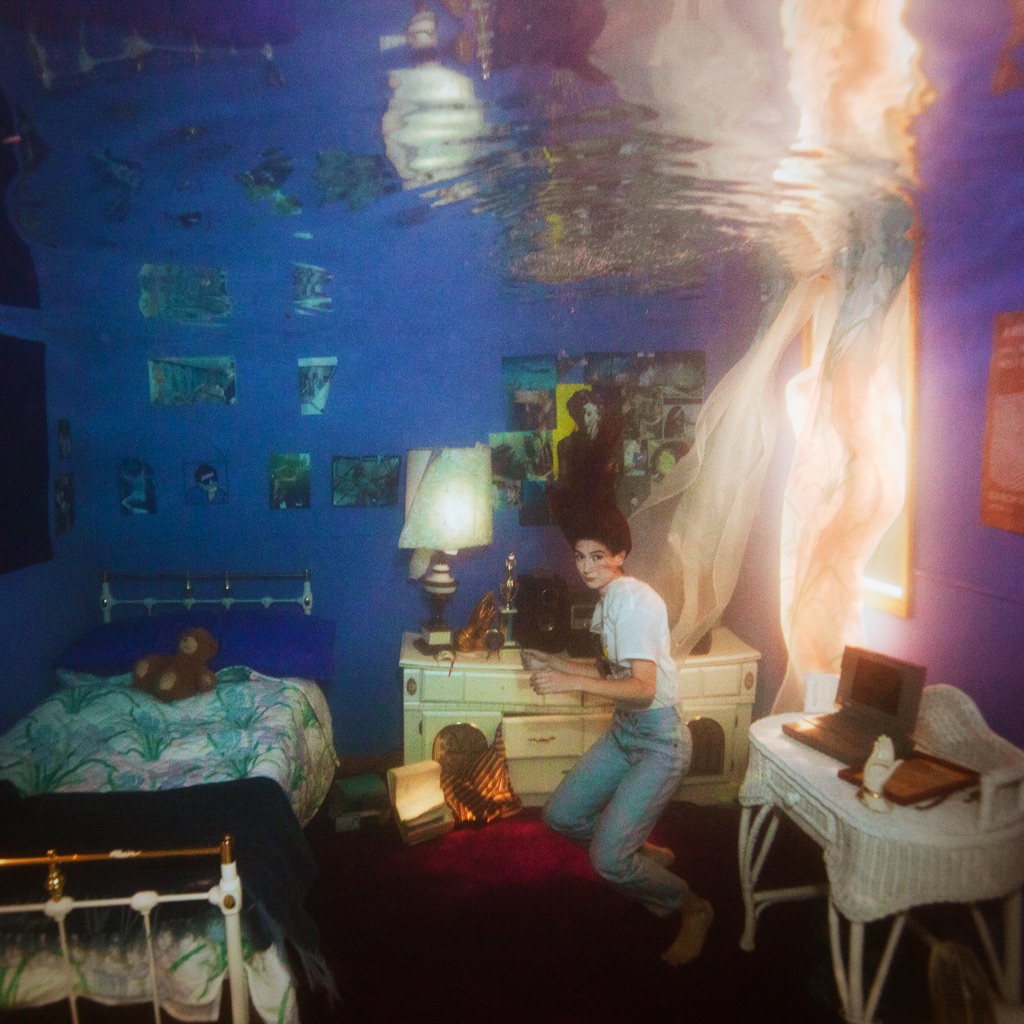

A successful child actor turned indie-rock sweetheart with Rilo Kiley, a solo artist beloved by the famed and famous, Jenny Lewis would appear to have led a gilded life. But her truth—and there have been intimations both in song lyrics and occasionally in interviews—is of a far darker inheritance. “I come from working-class showbiz people who ended up in jail, on drugs, both, or worse,” Lewis tells Apple Music. “I grew up in a pretty crazy, unhealthy environment, but I somehow managed to survive.” The death of her mother in 2017 (with whom she had reconnected after a 20-year estrangement) and the end of her 12-year relationship with fellow singer-songwriter Johnathan Rice set the stage for Lewis’ fourth solo album, where she finally reconciles her public and private self. A bountiful pop record about sex, drugs, death, and regret, with references to everyone from Elliott Smith to Meryl Streep, *On the Line* is the Lewis aesthetic writ large: an autobiographical picaresque burnished by her dark sense of humor. Here, Lewis takes us through the album track by track. **“Heads Gonna Roll”** “I’m a big boxing fan, and I basically wanted to write a boxing ballad. There’s a line about ‘the nuns of Harlem\'—that’s for real. I met a priest backstage at a Dead & Company show in a cloud of pot smoke. He was a fan of my music, and we struck up a conversation and a correspondence. I’d just moved to New York at the time and was looking to do some service work. And so this priest hooked me up with the nuns in Harlem. I would go up there and get really stoned and hang out with theses nuns, who were the purest, most lovely people, and help them put together meal packages. The nuns of Harlem really helped me out.” **“Wasted Youth”** “For me, the thing that really brings this song, and the whole record, together is the people playing on it. \[Drummer\] Jim Keltner especially. He’s played on so many incredible records, he’s the heartbeat of rock and roll and you don’t even realize it. Jim and Don Was were there for so much of this record, and they were the ones that brought Ringo Starr into the sessions—playing with him was just surreal. Benmont Tench is someone I’d worked with before—he’s just so good at referencing things from the past but playing something that sounds modern and new at the same time. He created these sounds that were so melodic and weird, using the Hammond organ and a bunch of pedals. We call that ‘the fog’—Benmont adds the fog.” **“Red Bull & Hennessy”** “I was writing this song, almost predicting the breakup with my longtime partner, while he was in the room. I originally wanted to call it ‘Spark,’ ’cause when that spark goes out in a relationship it’s really hard to get it back.” **“Hollywood Lawn”** “I had this for years and recorded three or four different versions; I did a version with three female vocalists a cappella. Then I went to Jamaica with Savannah and Jimmy Buffett—I actually wrote some songs with Jimmy for the *Escape to Margaritaville* musical that didn’t get used. We didn’t use that version, but I really arranged the s\*\*\* out of it there, and some of the lyrics are about that experience.” **“Do Si Do”** “Wrote this for a friend who went off his psych meds abruptly, which is so dangerous—you have to taper off. I asked Beck to produce it for a reason: He gets in there and wants to add and change chords. And whatever he suggests is always right, of course. That’s a good thing to remember in life: Beck is always right.” “Dogwood” “This is my favorite song on the record. I wrote it on the piano even though I don’t think I’m a very good piano player. I probably should learn more, but I’m just using the instrument as a way to get the song out. This was a live vocal, too. When I’m playing and singing at the same time, I’m approaching the material more as a songwriter rather than a singer, and that changes the whole dynamic in a good way.” **“Party Clown”** “I’d have to describe this as a Faustian love song set at South by Southwest. There’s a line in there where I say, ‘Can you be my puzzle piece, baby?/When I cry like Meryl Streep?’ It’s funny, because Meryl actually did a song of mine, ‘Cold One,’ in *Ricki and the Flash*.” **“Little White Dove”** “Toward the end of the record, I would write songs at home and then visit my mom in the hospital when she was sick. I started this on bass, had the chord structure down, and wrote it at the pace it took to walk from the hospital elevator to the end of the hall. I was able to sing my mom the chorus before she passed.” **“Taffy”** “That one started out as a poem I’d written on an airplane, then it turned into a song. It’s a very specific account of a weekend spent in Wisconsin, and there are some deep Wisconsin references in there. I’m not interested in platitudes, either as a writer or especially as a listener. I want to hear details. That’s why I like hip-hop so much. All those details, names that I haven’t heard, words that have meanings that I don’t understand and have to look up later. I’m interested in those kinds of specifics. That’s also what I love about Bob Dylan songs, too—they’re very, very specific. You can paint an incredibly vivid picture or set a scene or really project a feeling that way.” **“On the Line”** “This is an important song for me. If you read the credits on this record, it says, ‘All songs by Jenny Lewis.’ Being in a band like Rilo Kiley was all about surrendering yourself to the group. And then working with Johnathan for so long, I might have lost a little bit of myself in being a collaborator. It’s nice to know I can create something that’s totally my own. I feel like this got me back to that place.” **“Rabbit Hole”** “The record was supposed to end with ‘On the Line’—the dial tone that closes the song was supposed to be the last thing you hear. But I needed to write ‘Rabbit Hole,’ almost as a mantra for myself: ‘I’m not gonna go/Down the rabbit hole with you.’ I figured the song would be for my next project, but I played it for Beck and he insisted that we put it on this record. It almost feels like a perfect postscript to this whole period of my life.”

Singer-songwriter Natalie Mering’s fourth album as Weyes Blood conjures the feeling of a beautiful object on a shelf just out of reach: You want to touch it, but you can’t, and so you do the next best thing—you dream about it, ache for it, and then you ache some more. Grand, melodramatic, but keenly self-aware, the music here pushes Mering’s \'70s-style chamber pop to its cinematic brink, suffusing stories of everything from fumbled romance (the McCartney-esque “Everyday”) to environmental apocalypse (“Wild Time”) with a dreamy, foggy almost-thereness both gorgeous and profoundly unsettling. A self-described “nostalgic futurist,” Mering doesn’t recreate the past so much as demonstrate how the past is more or less a fiction to begin with, a story we love hearing no matter how sad its unreachability makes us. Hence the album’s centerpiece, “Movies,” which wonders—gorgeously, almost religiously—why life feels so messy by comparison. As to the thematic undercurrent of apocalypse, well, if extinction is as close as science says it is, we might as well have something pretty to play us out.

The phantom zone, the parallax, the upside down—there is a rich cultural history of exploring in-between places. Through her latest, Titanic Rising, Weyes Blood (a.k.a. Natalie Mering) has, too, designed her own universe to soulfully navigate life’s mysteries. Maneuvering through a space-time continuum, she intriguingly plays the role of melodic, sometimes melancholic, anthropologist. Tellingly, Mering classifies Titanic Rising as the Kinks meet WWII or Bob Seger meets Enya. The latter captures the album’s willful expansiveness (“You can tell there’s not a guy pulling the strings in Enya’s studio,” she notes, admiringly). The former relays her imperative to connect with listeners. “The clarity of Bob Seger is unmistakable. I’m a big fan of conversational songwriting,” she adds. “I just try to do that in a way that uses abstract imagery as well.” “An album is like a Rubik’s Cube,” she says. “Sometimes you get all the dimensions—the lyrics, the melody, the production—to line up. I try to be futuristic and ancient at once, which is a difficult alchemy. It’s taken a lot of different tries to get it right.” As concept-album as it may sound, it’s also a devoted exercise in realism, albeit occasionally magical. Here, the throwback-cinema grandeur of “A Lot’s Gonna Change” gracefully coexists with the otherworldly title track, an ominous instrumental. Titanic Rising, written and recorded during the first half of 2018, is the culmination of three albums and years of touring: stronger chops and ballsier decisions. It’s an achievement in transcendent vocals and levitating arrangements—one she could reach only by flying under the radar for so many years. “I used to want to belong,” says the L.A. based musician. “I realized I had to forge my own path. Nobody was going to do that for me. That was liberating. I became a Joan of Arc solo musician.” The Weyes Blood frontwoman grew up singing in gospel and madrigal choirs. “Classical and Renaissance music really influenced me,” says Mering, who first picked up a guitar at age 8. (Listen closely to Titanic Rising, and you’ll also hear the jazz of Hoagy Carmichael mingle with the artful mysticism of Alejandro Jodorowsky and the monomyth of scholar Joseph Campbell.) “Something to Believe,” a confessional that makes judicious use of the slide guitar, touches on that cosmological upbringing. “Belief is something all humans need. Shared myths are part of our psychology and survival,” she says. “Now we have a weird mishmash of capitalism and movies and science. There have been moments where I felt very existential and lost.” As a kid, she filled that void with Titanic. (Yes, the movie.) “It was engineered for little girls and had its own mythology,” she explains. Mering also noticed that the blockbuster romance actually offered a story about loss born of man’s hubris. “It’s so symbolic that The Titanic would crash into an iceberg, and now that iceberg is melting, sinking civilization.” Today, this hubris also extends to the relentless adoption of technology, at the expense of both happiness and attention spans. The track “Movies” marks another Titanic-related epiphany, “that movies had been brainwashing people and their ideas about romantic love.” To that end, Mering has become an expert at deconstructing intimacy. Sweeping and string-laden, “Andromeda” seems engineered to fibrillate hearts. “It’s about losing your interest in trying to be in love,” she says. “Everybody is their own galaxy, their own separate entity. There is a feeling of needing to be saved, and that’s a lot to ask of people.” Its companion track, “Everyday,” “is about the chaos of modern dating,” she says, “the idea of sailing off onto your ships to nowhere to deal with all your baggage.” But Weyes Blood isn’t one to stew. Her observations play out in an ethereal saunter: far more meditative than cynical. “I experience reality on a slower, more hypnotic level,” she says. “I’m a more contemplative kind of writer.” To Mering, listening and thinking are concurrent experiences. “There are complicated influences mixed in with more relatable nostalgic melodies,” she says. “In my mind my music feels so big, a true production. I’m not a huge, popular artist, but I feel like one when I’m in the studio. But it’s never taking away from the music. I’m just making a bigger space for myself.”

In the three years since her seminal album *A Seat at the Table*, Solange has broadened her artistic reach, expanding her work to museum installations, unconventional live performances, and striking videos. With her fourth album, *When I Get Home*, the singer continues to push her vision forward with an exploration of roots and their lifelong influence. In Solange\'s case, that’s the culturally rich Houston of her childhood. Some will know these references — candy paint, the late legend DJ Screw — via the city’s mid-aughts hip-hop explosion, but through Solange’s lens, these same touchstones are elevated to high art. A diverse group of musicians was tapped to contribute to *When I Get Home*, including Tyler, the Creator, Chassol, Playboi Carti, Standing on the Corner, Panda Bear, Devin the Dude, The-Dream, and more. There are samples from the works of under-heralded H-town legends: choreographer Debbie Allen, actress Phylicia Rashad, poet Pat Parker, even the rapper Scarface. The result is a picture of a particular Houston experience as only Solange could have painted it — the familiar reframed as fantastic.

It was on a mountainside in Cumbria that the first whispers of Cate Le Bon’s fifth studio album poked their buds above the earth. “There’s a strange romanticism to going a little bit crazy and playing the piano to yourself and singing into the night,” she says, recounting the year living solitarily in the Lake District which gave way to Reward. By day, ever the polymath, Le Bon painstakingly learnt to make solid wood tables, stools and chairs from scratch; by night she looked to a second-hand Meers — the first piano she had ever owned —for company, “windows closed to absolutely everyone”, and accidentally poured her heart out. The result is an album every bit as stylistically varied, surrealistically-inclined and tactile as those in the enduring outsider’s back catalogue, but one that is also intensely introspective and profound; her most personal to date. This sense of privacy maintained throughout is helped by the various landscapes within which Reward took shape: Stinson Beach, LA, and Brooklyn via Cardiff and The Lakes. Recording at Panoramic House [Stinson Beach, CA], a residential studio on a mountain overlooking the ocean, afforded Le Bon the ability to preserve the remoteness she had captured during the writing of Reward in Staveley, Lake District. Over this extended period a cast of trusted and loved musicians joined Le Bon, Khouja and fellow co-producer Josiah Steinbrick — Stella Mozgawa (of Warpaint) on drums and percussion; Stephen Black (aka Sweet Baboo) on bass and saxophone and longtime collaborators Huw Evans (aka H.Hawkline) and Josh Klinghoffer on guitars — and were added to the album, “one by one, one on one”. The fact that these collaborators have appeared variously on Le Bon’s previous outputs no doubt goes some way to aid the preservation of a signature sound despite a relatively drastic change in approach. Be it on her more minimalist, acoustic-leaning 2009 debut album Me Oh My or critically acclaimed, liquid-riffed 2013 LP Mug Museum as well as 2016s Crab Day, Cate Le Bon’s solo work — and indeed also her production work, such as that carried out on recent Deerhunter album Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared? (4AD, January 2019) — has always resisted pigeonholing, walking the tightrope between krautrock aloofness and heartbreaking tenderness; deadpan served with a twinkle in the eye, a flick of the fringe and a lick of the Telecaster. The multifaceted nature of Le Bon’s art — its ability to take on multiple meanings and hold motivations which are not immediately obvious — is evident right down to the album’s very name. “People hear the word ‘reward’ and they think that it’s a positive word” says Le Bon, “and to me it’s quite a sinister word in that it depends on the relationship between the giver and the receiver. I feel like it’s really indicative of the times we’re living in where words are used as slogans, and everything is slowly losing its meaning.” The record, then, signals a scrambling to hold onto meaning; it is a warning against lazy comparisons and face values. It is a sentiment nicely summed up by the furniture-making musician as she advises: “Always keep your hand behind the chisel.”

Our third long player (this time a double!) and second on Thin Wrist / Black Editions. From our label: 75 Dollar Bill is one of the essential groups at the heart of NYC's underground. Centered on the telepathic union of Che Chen's microtonal electric guitar and Rick Brown's odd metered percussion, their long-form sound is unmistakable and compelling. Their second album, 2016's Wood Metal Plastic Pattern Rhythm Rock (Thin Wrist), presented the essence of their sound with vivid clarity. Since then the group have travelled and performed extensively, bringing their music to a wider audience and performing everywhere from bustling sidewalks and intimate clubs to large concert halls and overseas festivals. The countless miles and performances of the last few years have resulted in their expansive new double album I WAS REAL. Over four sides the group expands in bold new directions, embracing brilliant fuller orchestrations, joyous rockers and entrancing new textures. The record is enhanced by the presence of eight additional players over its nine tracks while also showing off the duo's strength when stripped down to its core. Requiring a variety of approaches, the album was recorded over a four year period, in four different studios in a range of different ensemble configurations. The album also features several “studio as instrument” constructions that harken back to the collage-experiments of the band’s early cassette tapes, while at the same time pointing to new territories altogether. The players involved highlight the “social” aspect of the band and the eight guests that appear on the record are some of the band’s closest friends and collaborators. While Che Chen and Rick Brown are always at the core of 75 Dollar Bill, the band is much like an extended family, changing shape for different music and different situations. Some pieces were conceived in the band's very early days and others are much newer, but the music is unmistakably 75 Dollar Bill. As Steve Gunn has written on their work: “Strings come in underneath Che Chen's supreme guitar tone. Rick Brown's trance percussion offers a guiding support with bass, strings, and horns supporting the melody. They have gathered all the moving parts perfectly.” I WAS REAL is a monumental signature work capturing the group at the peak of their powers.

Michael Kiwanuka never seemed the type to self-title an album. He certainly wasn’t expected to double down on such apparent self-assurance by commissioning a kingly portrait of himself as the cover art. After all, this is the singer-songwriter who was invited to join Kanye West’s *Yeezus* sessions but eventually snuck wordlessly out, suffering impostor syndrome. That sense of self-doubt shadowed him even before his 2012 debut *Home Again* collected a Mercury Prize nomination. “It’s an irrational thought, but I’ve always had it,” he tells Apple Music. “It keeps you on your toes, but it was also frustrating me. I was like, ‘I just want to be able to do this without worrying so much and just be confident in who I am as an artist.’” Notions of identity also got him thinking about how performers create personas—onstage or on social media—that obscure their true selves, inspiring him to call his third album *KIWANUKA* in an act of what he calls “anti-alter-ego.” “It’s almost a statement to myself,” he says. “I want to be able to say, ‘This is me, rain or shine.’ People might like it, people might not, it’s OK. At least people know who I am.” Kiwanuka was already known as a gifted singer and songwriter, but *KIWANUKA* reveals new standards of invention and ambition. With Danger Mouse and UK producer Inflo behind the boards—as they were on *Love & Hate* in 2016—these songs push his barrel-aged blend of soul and folk further into psychedelia, fuzz rock, and chamber pop. Here, he takes us through that journey song by song. **You Ain’t the Problem** “‘You Ain’t the Problem’ is a celebration, me loving humans. We forget how amazing we are. Social media’s part of this—all these filters hiding things that we think people won\'t like, things we think don\'t quite fit in. You start thinking this stuff about you is wrong and that you’ve got a problem being whatever you are and who you were born to be. I wanted to write a song saying, ‘You’re not the problem. You just have to continue being *you* more, go deeper within yourself.’ That’s where the magic comes—as opposed to cutting things away and trying to erode what really makes you.” **Rolling** “‘Rolling with the times, don’t be late.’ Everything’s about being an artist for me, I guess. I was trying to find my place still, but you can do things to make sure that you fit in or are keeping up with everything that’s happening—whether it’s posting stuff online or keeping up with the coolest records, knowing the right things. Or it could just be you’re in your mid-thirties, you haven’t got married or had kids yet, and people are like, ‘What?’ ‘Rolling with the times’ is like, go at your own pace. In my head, there was early Stooges records and French records like Serge Gainsbourg with the fuzz sounds. I wanted to make a song that sounded kind of crazy like that.” **I’ve Been Dazed** “Eddie Hazel from Funkadelic is my favorite guitar player. This has anthemic chords because he would always have really beautiful anthemic chords in the songs that he wrote. It just came out almost hymn-like. Lyrically, because it has this melancholy feel to it, I was singing about waking up from the nightmare of following someone else’s path or putting yourself down, low self-esteem—the things ‘You Ain\'t the Problem’ is defying. The feeling is, ‘Man, I\'ve been in this kind of nightmare, I just want to get out of it, I’m ready to go.’” **Piano Joint (This Kind of Love) \[Intro\]** “As a teenager, I’d just escape \[into some albums\], like I could teleport away from life and into that person’s world. I really wanted to have that feel with this record. It would be so vivid, there was no chance to get out of it, no gap in the songs—make it feel like one long piece. Some songs just flow into each other, but some needed interludes as passageways. This intro came when I was playing some bass and \[Inflo\] was playing some piano and I started singing my idea of a Marvin Gaye soul tune—a deep, dark, melancholic cut from one of his ’70s records. Then Danger Mouse had the idea, ‘Why don’t you pitch some of it down so it sounds different?’” **Piano Joint (This Kind of Love)** “I used to always love melancholy songs; the sadder it is, the happier I’d be afterwards. This was my moment to really exercise that part of me. Originally, it was going to be a piano ballad, and then I was like, ‘Why don’t we try playing some drums?’ Inflo’s a really good drummer, so I went in and played bass with him, and it sounded really good. I was thinking of that ’70s Gil Scott-Heron East Coast soul. Then we worked with this amazing string arranger, Rosie Danvers, who did almost all the strings on the last album. I said to her, ‘It’s my favorite song, just do something super beautiful.’ She just killed it.” **Another Human Being** “We were doing all the interludes and Danger Mouse had found loads of samples. This was a news report \[about the ’60s US civil rights sit-in protests\]. I remember thinking, ‘This sounds amazing, it goes into “Living in Denial” perfectly—it just changes that song.’ And, yeah, again, I’m ’70s-obsessed, but the ’60s and ’70s were so pivotal for young American black men and women, and it just gave a gravitas to the record. It goes to identity and something that resonates with me and my name and who I am. It gives me loads of confidence to continue to be myself.” **Living in Denial** “This is how me, Inflo, and Danger Mouse sound when we’re completely ourselves and properly linked together. No arguments, just let it happen, don’t think about it. I was trying to be a soul group—thinking of The Delfonics, The Isley Brothers, The Temptations, The Chambers Brothers. Again, the lyrics are that thing of seeking acceptance: You don’t need to seek it, just accept yourself and then whoever wants to hang with you will.” **Hero (Intro)** “‘Hero’ was the last song we completed. Once it started to sound good, I was sitting there with my acoustic, playing. We’d done the ‘Piano Joint’ intro and I was like, ‘Oh, we should pitch down this number as well and make it something that we really wouldn’t do with a straight rock ’n’ roll song.’” **Hero** “‘Hero’ was the hardest to come up with lyrics for. We had the music and melody for, like, two years. Any time I tried to touch it, I hated it—I couldn’t come up with anything. Then I was reading about Fred Hampton from the Black Panthers and I started thinking about all these people that get killed—or, like Hendrix, die an accidental death—who have so much to give or do so much in such a small time. I also love the thing where all these legends, Bowie and Bob Dylan, were creating larger-than-life personas that we were obsessed with. You didn’t really know who they were. That really made me sad, because I don’t disagree with it, but I know that’s not me. So, ‘Am I a hero?’ was also asking, ‘If I do that stuff, will I become this big artist that everyone respects?’—that ‘I’m not enough’ thing.” **Hard to Say Goodbye** “This is my love of Isaac Hayes and big orchestrations, lush strings, people like David Axelrod. Flo actually brought in this sample from a Nat King Cole song, just one chord, and we pitched it around, and then we replayed it with a 20-piece string orchestra packed into the studio. We had a double-bass cello, the whole works, and this really good piano player Kadeem \[Clarke\] who plays with Little Simz, and our friend Nathan \[Allen\] playing drums. That was pretty fun.” **Final Days** “At first, I didn’t know where this would fit on the record, like, ‘Man, this is cool, I just don’t *love*it.’ I wrote some lyrics and thought, ‘This is better, but it’s missing something.’ It always felt like space to me, so I said to Kennie \[Takahashi\], the engineer, ‘Are there any samples you can find of people in space?’ We found these astronauts about to crash, which is kind of dark, but it gave it this emotion it was missing. It gave me goosebumps. Later, we found out that it was a fake, some guys messing around in Italy in the ’60s for an art project or something.” **Interlude (Loving the People)** “‘Final Days’ was sounding amazing, but it needed to go somewhere else at the end. I had this melody on the Wurlitzer, and originally it was an instrumental bit that comes in for the end of ‘Final Days’ so that it ends somewhere completely different, like the spaceship’s landing at its destination. But I was like, ‘Let’s stretch it out. Let’s do more.’ Danger Mouse found this \[US congressman and civil rights leader\] John Lewis sample, and it sounded beautiful and moving over these chords, so we put it here.” **Solid Ground** “When everything gets stripped away—all the strings, all the sounds, all the interludes—I’m still just a dude that sits and plays a song on a guitar or piano. I felt like the album needed a glimpse of that. Rosie did a beautiful arrangement and then I finished it off—everyone was out somewhere, so I just played all the instruments, apart from drums and things like that. So, ‘Solid Ground’ is my little piece that I had from another place. Lyrically, it’s about finding the place where you feel comfortable.” **Light** “I just thought ‘Light’ was a nice dreamy piece to end the record with—a bit of light at the end of this massive journey. You end on this peaceful note, something positive. For me, light describes loads of things that are good—whether it’s obvious things like the light at the end of the tunnel or just a light feeling in my heart. The idea that the day’s coming—such a peaceful, exciting thing. We’re just always looking for it.” *All Apple Music subscribers using the latest version of Apple Music on iPhone, iPad, Mac, and Apple TV can listen to thousands of Dolby Atmos Music tracks using any headphones. When listening with compatible Apple or Beats headphones, Dolby Atmos Music will play back automatically when available for a song. For other headphones, go to Settings > Music > Audio and set the Dolby Atmos switch to “Always On.” You can also hear Dolby Atmos Music using the built-in speakers on compatible iPhones, iPads, MacBook Pros, and HomePods, or by connecting your Apple TV 4K to a compatible TV or AV receiver. Android is coming soon. AirPods, AirPods Pro, AirPods Max, BeatsX, Beats Solo3, Beats Studio3, Powerbeats3, Beats Flex, Powerbeats Pro, and Beats Solo Pro Works with iPhone 7 or later with the latest version of iOS; 12.9-inch iPad Pro (3rd generation or later), 11-inch iPad Pro, iPad (6th generation or later), iPad Air (3rd generation), and iPad mini (5th generation) with the latest version of iPadOS; and MacBook (2018 model and later).*

Big Thief has been known to tackle intensely personal themes: family histories, deaths, isolation, fear. Here, on their expansive third album, the New York indie rock band shifts its gaze outward and into the unknown. \"Just like a bad dream/You\'ll disappear,” frontwoman Adrianne Lenker coos on the title track. \"And I imagine you/Taking me outta here.” Through gentle strums and hushed, tumbling melodies, the band wonders: Who\'s out there? Are they as strange as we are? What’s real? The second F in the album’s title stands for “friend”—an optimistic embrace of all things unfamiliar or alien. Their songs—comforting, eerie, folksy, magnificent—do the same.

U.F.O.F., F standing for ‘Friend’, is the name of the highly anticipated third record by Big Thief, set to be released on 3rd May 2019 via 4AD. U.F.O.F. was recorded in rural western Washington at Bear Creek Studios. In a large cabin-like room, the band set up their gear to track live with engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who was also behind their previous albums. Having already lived these songs on tour, they were relaxed and ready to experiment. The raw material came quickly. Some songs were written only hours before recording and stretched out instantly, first take, vocals and all. “Making friends with the unknown… All my songs are about this,” says Lenker; “If the nature of life is change and impermanence, I’d rather be uncomfortably awake in that truth than lost in denial.”

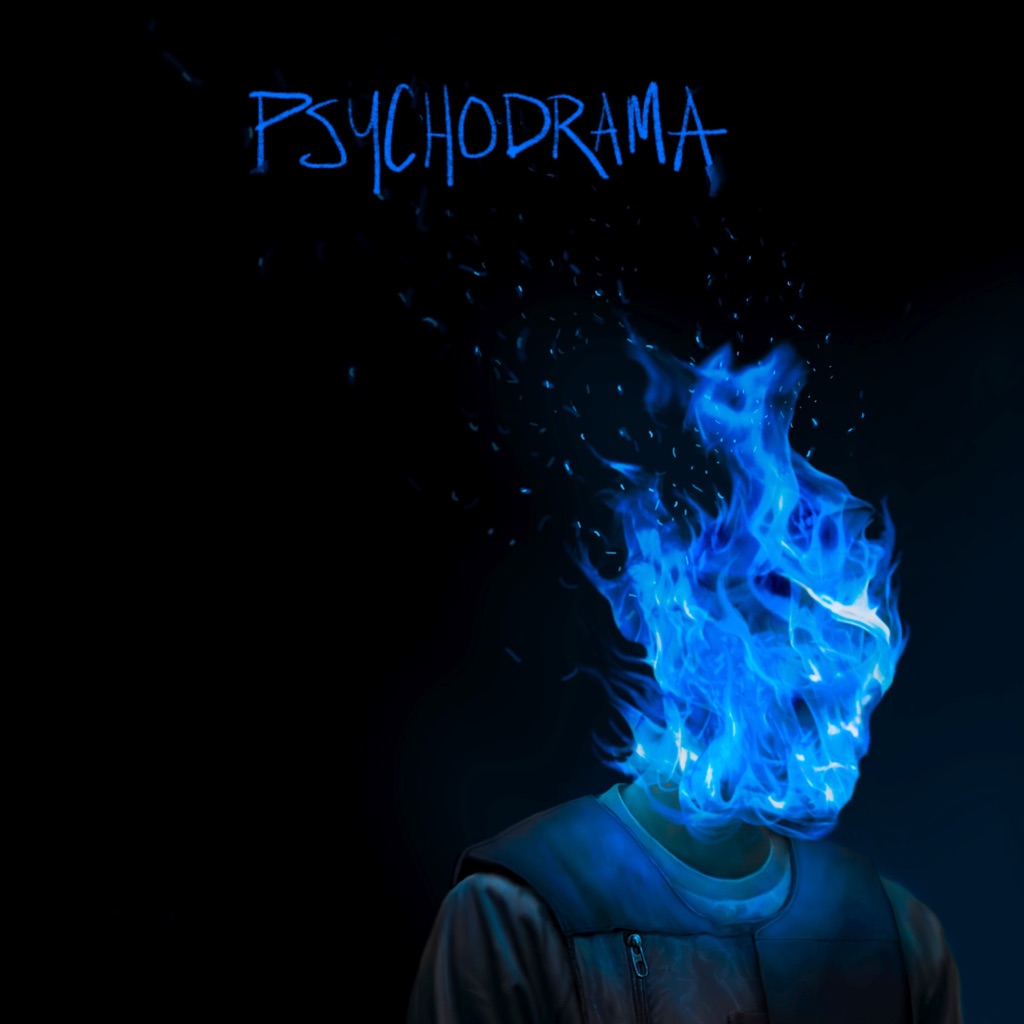

The more music Dave makes, the more out of step his prosaic stage name seems. The richness and daring of his songwriting has already been granted an Ivor Novello Award—for “Question Time,” 2017’s searing address to British politicians—and on his debut album he gets deeper, bolder, and more ambitious. Pitched as excerpts from a year-long course of therapy, these 11 songs show the South Londoner examining the human condition and his own complex wiring. Confession and self-reflection may be nothing new in rap, but they’ve rarely been done with such skill and imagination. Dave’s riveting and poetic at all times, documenting his experience as a young British black man (“Black”) and pulling back the curtain on the realities of fame (“Environment”). With a literary sense of detail and drama, “Lesley”—a cautionary, 11-minute account of abuse and tragedy—is as much a short story as a song: “Touched her destination/Way faster than the cab driver\'s estimation/She put the key in the door/She couldn\'t believe what she see on the floor.” His words are carried by equally stirring music. Strings, harps, and the aching melodies of Dave’s own piano-playing mingle with trap beats and brooding bass in incisive expressions of pain and stress, as well as flashes of optimism and triumph. It may be drawn from an intensely personal place, but *Psychodrama* promises to have a much broader impact, setting dizzying new standards for UK rap.

On her fifth proper full-length album, Sharon Van Etten pushes beyond vocals-and-guitar indie rock and dives headlong into spooky maximalism. With production help from John Congleton (St. Vincent), she layers haunting drones with heavy, percussive textures, giving songs like “Comeback Kid” and “Seventeen” explosive urgency. Drawing from Nick Cave, Lucinda Williams, and fellow New Jersey native Bruce Springsteen, *Remind Me Tomorrow* is full of electrifying anthems, with Van Etten voicing confessions of reckless, lost, and sentimental characters. The album challenges the popular image of Van Etten as *just* a singer-songwriter and illuminates her significant talent as composer and producer, as an artist making records that feel like a world of their own.

“How people may emotionally connect with music I’ve been involved in is something that part of me is completely mystified by,” Thom Yorke tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “Human beings are really different, so why would it be that what I do connects in that way? I discovered maybe around \[Radiohead\'s album\] *The Bends* that the bit I didn’t want to show, the vulnerable bit… that bit was the bit that mattered.” *ANIMA*, Yorke’s third solo album, further weaponizes that discovery. Obsessed by anxiety and dystopia, it might be the most disarmingly personal music of a career not short of anxiety and dystopia. “Dawn Chorus” feels like the centerpiece: It\'s stop-you-in-your-tracks beautiful with a claustrophobic “stream of consciousness” lyric that feels something like a slowly descending panic attack. And, as Yorke describes, it was the record\'s biggest challenge. “There’s a hit I have to get out of it,” he says. “I was trying to develop how ‘Dawn Chorus’ was going to work, and find the right combinations on the synthesizers I was using. Couldn’t find it, tried it again and again and again. But I knew when I found it I would have my way into the song. Things like that matter to me—they are sort of obsessive, but there is an emotional connection. I was deliberately trying to find something as cold as possible to go with it, like I sing essentially one note all the way through.” Yorke and longtime collaborator Nigel Godrich (“I think most artists, if they\'re honest, are never solo artists,” Yorke says) continue to transfuse raw feeling into the album’s chilling electronica. “Traffic,” with its jagged beats and “I can’t breathe” refrain, feels like a partner track to another memorable Yorke album opener, “Everything in Its Right Place.” The extraordinary “Not the News,” meanwhile, slaloms through bleeps and baleful strings to reach a thunderous final destination. It’s the work of a modern icon still engaged with his unique gift. “My cliché thing I always say is, \'You know you\'re in trouble when people stop listening to sad music,\'” Yorke says. “Because the moment people stop listening to sad music, they don\'t want to know anymore. They\'re turning themselves off.”

“It was baby steps—we didn’t say, hey, we’re going to make an album or go on tour,” The Raconteurs co-frontman Jack White explains to Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “We just thought, let’s get together and record a couple of songs and see how that goes.” The time felt right for White and Brendan Benson to reconnect following a series of jam sessions with drummer Patrick Keeler, something they hadn’t done in over a decade due to their commitments to other projects. During that time, White pursued his solo career and formed The Dead Weather with Raconteurs bassist Jack Lawrence, all while running Third Man Records; Benson launched his own record label and released 2012’s *What Kind of World* and 2013’s *You Were Right*. Though their third album touches on the power-pop stomp of *Broken Boy Soldiers* and the country-folk of *Consolers of the Lonely*, the band now seems to have one mission in mind: Play some good ol’ fashioned classic rock that pays homage to their musical roots. White and Benson are both based in Nashville now, but their native Michigan is never far from their hearts. “Well, I’m Detroit born and raised/But these days, I’m living with another,” White and Benson harmonize on the single “Bored and Razed.” The guitars nod to pioneering Michigan bands like Grand Funk Railroad and The Amboy Dukes, while the scuzzy, frantic Stooges-like garage rock of “Don’t Bother Me” features White, unsurprisingly, imploring you to put down your damn phone. But *Help Us Stranger* is not just strut and swagger: From reflective folk rock (“Only Child”) and piano balladry (“Shine the Light on Me”) to heartbreaking blues (“Now That You’re Gone”), White and Benson keep it fresh with their engaging, mood-shifting songwriting. They sound like they’re genuinely having fun, happy that they’re still together after all these years. “We played a show in London with The Strokes, and what struck me was, \'Ah, it’s so great to see any band have the original members they started with even three years later, let alone 15, 20 years later,\'” says White. “Everyone’s for the same goal of trying to make some sort of music happen that didn’t exist before. But the proof is, those same people are in the room together.”

With powerhouse pipes, razor-sharp wit, and a tireless commitment to self-love and self-care, Lizzo is the fearless pop star we needed. Born Melissa Jefferson in Detroit, the singer and classically trained flautist discovered an early gift for music (“It chose me,” she tells Apple Music) and began recording in Minneapolis shortly after high school. But her trademark self-confidence came less naturally. “I had to look deep down inside myself to a really dark place to discover it,” she says. Perhaps that’s why her third album, *Cuz I Love You*, sounds so triumphant, with explosive horns (“Cuz I Love You”), club drums (“Tempo” featuring Missy Elliott), and swaggering diva attitude (“No, I\'m not a snack at all/Look, baby, I’m the whole damn meal,” she howls on the instant hit “Juice\"). But her brand is about more than mic-drop zingers and big-budget features. On songs like “Better in Color”—a stomping, woke plea for people of all stripes to get together—she offers an important message: It’s not enough to love ourselves, we also have to love each other. Read on for Lizzo’s thoughts on each of these blockbuster songs. **“Cuz I Love You”** \"I start every project I do with a big, brassy orchestral moment. And I do mean *moment*. It’s my way of saying, ‘Stand the fuck up, y’all, Lizzo’s here!’ This is just one of those songs that gets you amped from the jump. The moment you hear it, you’re like, ‘Okay, it’s on.’ It’s a great fucking way to start an album.\" **“Like a Girl”** \"We wanted take the old cliché and flip it on its head, shaking out all the negative connotations and replacing them with something empowering. Serena Williams plays like a girl and she’s the greatest athlete on the planet, you know? And what if crying was empowering instead of something that makes you weak? When we got to the bridge, I realized there was an important piece missing: What if you identify as female but aren\'t gender-assigned that at birth? Or what if you\'re male but in touch with your feminine side? What about my gay boys? What about my drag queens? So I decided to say, ‘If you feel like a girl/Then you real like a girl,\' and that\'s my favorite lyric on the whole album.\" **“Juice”** \"If you only listen to one song from *Cuz I Love You*, let it be this. It’s a banger, obviously, but it’s also a state of mind. At the end of the day, I want my music to make people feel good, I want it to help people love themselves. This song is about looking in the mirror, loving what you see, and letting everyone know. It was the second to last song that I wrote for the album, right before ‘Soulmate,\' but to me, this is everything I’m about. I wrote it with Ricky Reed, and he is a genius.” **“Soulmate”** \"I have a relationship with loneliness that is not very healthy, so I’ve been going to therapy to work on it. And I don’t mean loneliness in the \'Oh, I don\'t got a man\' type of loneliness, I mean it more on the depressive side, like an actual manic emotion that I struggle with. One day, I was like, \'I need a song to remind me that I\'m not lonely and to describe the type of person I *want* to be.\' I also wanted a New Orleans bounce song, \'cause you know I grew up listening to DJ Jubilee and twerking in the club. The fact that l got to combine both is wild.” **“Jerome”** \"This was my first song with the X Ambassadors, and \[lead singer\] Sam Harris is something else. It was one of those days where you walk into the studio with no expectations and leave glowing because you did the damn thing. The thing that I love about this song is that it’s modern. It’s about fuccboi love. There aren’t enough songs about that. There are so many songs about fairytale love and unrequited love, but there aren’t a lot of songs about fuccboi love. About when you’re in a situationship. That story needed to be told.” **“Cry Baby”** “This is one of the most musical moments on a very musical album, and it’s got that Minneapolis sound. Plus, it’s almost a power ballad, which I love. The lyrics are a direct anecdote from my life: I was sitting in a car with a guy—in a little red Corvette from the ’80s, and no, it wasn\'t Prince—and I was crying. But it wasn’t because I was sad, it was because I loved him. It was a different field of emotion. The song starts with \'Pull this car over, boy/Don\'t pretend like you don\'t know,’ and that really happened. He pulled the car over and I sat there and cried and told him everything I felt.” **“Tempo”** “‘Tempo\' almost didn\'t make the album, because for so long, I didn’t think it fit. The album has so much guitar and big, brassy instrumentation, but ‘Tempo’ was a club record. I kept it off. When the project was finished and we had a listening session with the label, I played the album straight through. Then, at the end, I asked my team if there were any honorable mentions they thought I should play—and mind you, I had my girls there, we were drinking and dancing—and they said, ‘Tempo! Just play it. Just see how people react.’ So I did. No joke, everybody in the room looked at me like, ‘Are you crazy? If you don\'t put this song on the album, you\'re insane.’ Then we got Missy and the rest is history.” **“Exactly How I Feel”** “Way back when I first started writing the song, I had a line that goes, ‘All my feelings is Gucci.’ I just thought it was funny. Months and months later, I played it at Atlantic \[Records\], and when that part came up, I joked, ‘Thanks for the Gucci feature, guys!\' And this executive says, ‘We can get Gucci if you want.\' And I was like, ‘Well, why the fuck not?\' I love Gucci Mane. In my book, he\'s unproblematic, he does a good job, he adds swag to it. It doesn’t go much deeper than that, to be honest. The rest of the song has plenty of meaning: It’s an ode to being proud of your emotions, not feeling like you have to hide them or fake them, all that. But the Gucci feature was just fun.” **“Better in Color”** “This is the nerdiest song I have ever written, for real. But I love it so much. I wanted to talk about love, attraction, and sex *without* talking about the boxes we put those things in—who we feel like we’re allowed to be in love with, you know? It shouldn’t be about that. It shouldn’t be about gender or sexual orientation or skin color or economic background, because who the fuck cares? Spice it up, man. Love *is* better in color. I don’t want to see love in black and white.\" **“Heaven Help Me”** \"When I made the album, I thought: If Aretha made a rap album, what would that sound like? ‘Heaven Help Me’ is the most Aretha to me. That piano? She would\'ve smashed that. The song is about a person who’s confident and does a good job of self-care—a.k.a. me—but who has a moment of being pissed the fuck off and goes back to their defensive ways. It’s a journey through the full spectrum of my romantic emotions. It starts out like, \'I\'m too cute for you, boo, get the fuck away from me,’ to \'What\'s wrong with me? Why do I drive boys away?’ And then, finally, vulnerability, like, \'I\'m crying and I\'ve been thinking about you.’ I always say, if anyone wants to date me, they just gotta listen to this song to know what they’re getting into.\" **“Lingerie”** “I’ve never really written sexy songs before, so this was new for me. The lyrics literally made me blush. I had to just let go and let God. It’s about one of my fantasies, and it has three different chord changes, so let me tell you, it was not easy to sing. It was very ‘Love On Top’ by Beyoncé of me. Plus, you don’t expect the album to end on this note. It leaves you wanting more.”

Edwyn Collins has announced details of the release of his 9th solo album, Badbea, which is released on Friday 29th March 2019. Having released his last album, Understated in March 2013, Badbea is his first release since moving both home and studio to Helmsdale on the North East coast of Scotland in 2014. Building a new studio from scratch, the impressive Clashnarrow Studios which sits on the hills overlooking Helmsdale, Collins completed work on Badbea with co-producer Sean Read (Dexys, The Rockingbirds) and long-term musical cohorts Carwyn Ellis (Colorama) & James Walbourne (The Pretenders / The Rails). The track listing of Badbea is as follows: 1. It’s All About You 2. In The Morning 3. I Guess We Were Young 4. It All Makes Sense To Me 5. Outside 6. Glasgow To London 7. Tensions Rising 8. Beauty 9. I Want You 10. I’m OK Jack 11. Sparks The Spark 12. Badbea

Bassist/vocalist Esperanza Spalding is in many ways a conceptual artist: Her 2016 record *Emily\'s D+Evolution*, for instance, was a feature for her alter ego, while 2018’s *12 Little Spells*, her seventh LP, follows in that spirit. Each of its tracks (and their attendant scope-expanding videos) is like an incantation dedicated to a different body part. This deluxe edition of the album actually offers 16 spells; blood, hair, joints, and shoulders have also been accounted for now. While Spalding is a talented soloist, overall *12 Little Spells* is hardly a platform to showcase that side of her. The wild shapes of Spalding’s melodies, and the way they sound against the sand-and-glass chords of Matthew Stevens’ guitar, are like nothing else being done in music. The subtle funky twists in her song forms—the harmonic utter strangeness and post-tonality of “To Tide Us Over,” “The Longing Deep Down,” and “Now Know”—underline her ability to bring highly complex ideas into an easily accessible groove-driven setting (with help from ace drummer Justin Tyson). The album’s \"spells\" conceit stems from Spalding’s interest in music therapy, which she’s pursuing on a formal academic level, with an eye toward social justice applications (on “Dancing the Animal” she sings, “Google ‘humanity,\' but while you do/Guard the animal in you”). But as she said in an interview with The Daily Beast, “You can go as far with me as you want or just enjoy it as some dope music.”

“We’ve never really had anyone say to us, ‘All right, this song is good but we should try to push it to another level,’” Hot Chip’s Joe Goddard tells Apple Music. Seven albums deep, the band—Goddard, Alexis Taylor, Al Doyle, Owen Clarke, and Felix Martin—decided to reach new levels by working with producers for the first time, drafting in Rodaidh McDonald (The xx, Sampha) and the late French touch prime mover Philippe Zdar. “They didn\'t really ask us to do anything mega crazy, but there were moments when they challenged us and pushed us out of our comfort zone, which was really healthy and good,” says Goddard. *A Bath Full of Ecstasy* handsomely vindicates the decision to solicit external opinion. Rather than abandon their winning synthesis of pop melodies, melancholy, and the sparkle of club music, the band has finessed it into their brightest, sharpest album yet. And they got there with the help of Katy Perry, hot sauce, and Taylor’s mother-in-law—discover how with their track-by-track guide. **“Melody of Love”** Alexis Taylor: “It’s about submitting to sound, and finding optimism within its abstract beauty. It’s about the personal as well as the more universal problems being faced by individuals, and overcoming those; it’s about connecting to something that resonates with you.” Joe Goddard: “I was initially imagining I would put it out without vocals on, without there really being a song. But I found this sample from a gospel track by The Mighty Clouds of Joy, and Alexis responded to the music very quickly and wrote these great words. Rodaidh is a very focused person, a bit like the T-1000, and was like, ‘OK, guys, we’re going to do this, this, this, this, this.’ And he cut it right down, which was a really good suggestion.” **“Spell”** AT: “This is a seduction song, but it’s not entirely clear who is in the driving seat, who has the upper hand, who holds the whip…” JG: “Alexis’ songwriting and lyrics are fantastic, but he is such an enormous lover of Prince, I felt like there would be places that he could go that would be slightly more sensual, sexual. And that he would really excel at it. But I don’t think it comes naturally to him. Then we were asked to do a few days in the studio with Katy Perry. We wrote a bunch of short demo ideas to play to her, and the beginning of ‘Spell’ was one of those. I think for Alexis, imagining writing something for her was quite freeing.” **“Bath Full of Ecstasy”** AT: “‘Bath Full of Ecstasy’ is a side-scrolling platform game in which the player takes control of one of the five band members on a quest to save the kingdom. A curse has ravaged the kingdom and eradicated all joy from the land, and the townsfolk and villagers can no longer see colors or hear music. With the help of the Bubble Bath Fairy, a magical microphone, and some friendly strangers along the way, the band must embark on a quest through five exciting worlds on a mission to find the secret source that will break the curse.” **“Echo”** JG: “The demo was another one that we wrote for the Katy Perry sessions. We were trying to do something a bit Neptunes-y, a bit Pharrell—quite simple hip-hop-y bassline and drums. Lyrically it deals with letting go of your past.” AT: “It was originally called ‘Hot Sauce’ and was written about my favorite hot sauce, made by my friend, the steel-pan legend Fimber Bravo.” Al Doyle: “This was Philippe bringing to the pool his concept of ‘air,’ putting in huge gaps and spaces and really reducing the sonic palette of the song—to the point where you’re almost like, ‘Oh wow, this is actually almost too sparse.’ But what is there is extremely powerful and crafted and razor-sharp.” **“Hungry Child”** JG: “It’s all about this real longing, obsessional kind of love—unrequited. Obviously, a classic subject for soul and disco music, and I was really channeling that. I love disco records that do that; I think there’s a real special power to them. And in Jamie Principle, Frankie Knuckles, that brilliant deep house classic Round Two, ‘New Day,’ you get this obsessional, dark love stuff as well.” AT: “I mainly played Mellotron and wrote the chorus—about things which are momentary but somehow affect you forever.” **“Positive”** AT: “The song talks about perceptions of homelessness, illness, the need for community, kind gestures or lack of, information, love. It’s a heartbreak song with those subjects and a fantasy relationship at the core.” JG: “It features this Eurorack synth stuff very heavily, which is screamingly modern-sounding.” **“Why Does My Mind”** AT: “A song written on Alex Chilton’s guitar, lent to me by Jason McPhail \[of Glasgow band V-Twin\], about the perplexing way in which my mind works.” **“Clear Blue Skies”** JG: “Once a record is 70 percent done, you’re thinking about how to complement the music that you already have. So we wanted to have a more gentle, drum-machine-led thing. I was really also inspired by ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ by Brian Eno, which has that feel. I find it really difficult, with the size of the universe, trying to find that meaning in small things. I find that really problematic sometimes—that’s the meaning of the song.” **“No God”** AT: “A love song, written with my mother-in-law in mind as the singer, for a TV talent show contest, but never delivered to her, and instead turned into a euphoric song about love for a person rather than God, or light.” JG: “The chorus and the verse are very, very simple pop music. It reminded us of ABBA at one point. We struggled to find a production that was interesting, that had the right balance of strangeness and poppiness. It reminds me a bit of Andrew Weatherall and Primal Scream, that kind of balearic house thing.” Owen Clarke: “It went reggae for a bit. It had a techno moment as well.”