Indieheads Best of 2022

Highest voted albums from /r/indieheads in 2022, Reddit's Indie music community.

Source

In 2005, Swedish singer/songwriter Jens Lekman released *Oh You’re So Silent Jens*, a collection of the songs he’d written from 2003 up until that point. Filled with wry if gently despondent observations and potent melodies, the album placed him among indie pop’s upper tier of troubadours—but in 2011 it was taken out of print, vanishing some of his most beloved songs from availability. *The Cherry Trees Are Still In Blossom*, an update of *Silent* that blends bits of those early-2000s recordings with newly laid-down tracks, breathes new energy into songs that already sparkled because of their tightly knotted lyrics and Lekman’s deadpan yet melodic delivery. *Cherry* warmly updates Lekman’s earliest material in a way that allows longtime listeners to reflect on his two decades of musical growth while also inviting newer audiences to listen to cuts like the gently undulating “Maple Leaves” (here, with a live string quartet swapped in for the original’s sample-heavy track) and the brightly world-weary “Black Cab” on endless repeat.

All my friends were playing in these bass-guitar-drum bands,” speaks Jens Lekman, casting his mind back over twenty years to his first rudimentary experiments with sampling using his father’s old cassette recorder, and an instinct to create music that would set him far apart from his Swedish pop peers. “I’m going to sound like Scott Walker. But I’m going to do it in my bedroom.” Works of sweeping, maximalist, orchestral wonder sung in a sumptuous tenor, weaving lifts from obscure fleamarket vinyl records with by turns burningly romantic and mordantly funny true-life tales from the sleepy-shadowy suburbs of Gothenburg – Lekman’s early songs come from a different time, a different place. An era when the internet was young, limitless and disruptive, sample culture was turning music inside out, and anything felt possible. After initially finding an audience through peer-to-peer file sharing sites, Lekman signed to Secretly Canadian Records in 2003, and went on to release a slew of cherished material, including three cult limited-edition EPs – Maple Leaves, Rocky Dennis and Julie – later collected on the 2005 compilation album Oh You’re So Silent Jens. His DIY fantasias found their fullest and most celebrated form in 2007 on his second album proper, the exquisite Night Falls Over Kortedala – Lekman’s self-professed “dream record”. It went to number one in Sweden and was later hailed as one of the 200 best albums of the 2000s by Pitchfork, as well as one of the top 100 albums of the 21st century so far by The Guardian. Now, like Oh You’re So Silent Jens, it no longer exists in its original form. Oh You’re So Silent Jens enigmatically disappeared in 2011; Night Falls Over Kortedala followed suit in early 2022. Lekman’s impulse for giving old music fresh life and context has led him to remake the records under new names, each delicately positioned in dialogue with the past – the same albums, just different. The Cherry Trees Are Still In Blossom and The Linden Trees Are Still In Blossom are a pair of lovingly and painstakingly assembled reduxes each keeping the same core tracklisting, spirit and source material as the originals, but blending brand new versions of some tracks, in part or in whole, together with many tracks left largely as they were. Both records are fleshed out with rare, previously unreleased, and even previously unfinished old songs, as well as other contemporaneous material such as cassette diaries. On The Cherry Trees, two of Lekman’s best-loved early breakout singles are completely reimagined – ‘Maple Leaves’ as a tender ballad burnished with warm strings; tragi-comic illegal taxi ride to oblivion ‘Black Cab’ in two different versions, a handsome full band pop song and a gentle acoustic lullaby. The Linden Trees repackages all the true-life tales, magic, and mystery of Night Falls for a new age, yet in wholly familiar form, from the joyous ‘The Opposite of Hallelujah’ to hilariously uplifting missive ‘A Postcard to Nina’ and open-hearted love-song ‘Your Arms Around Me’. Taken together, the new albums form a sort of belated farewell to Lekman’s formative days as a bedroom Scott Walker, panning for sample gold in stacks of vintage vinyl. Albeit not a farewell to the original albums themselves, which will live on in fans’ record collections, and perhaps illicit corners of the internet. Spread to the wind. “I feel like these new records are like portals that can lead you to the old records if you want,” Lekman reflects. “I think that they can lead you to another time and a place, where you could work with music in a different way.”

Questions of value, respect, and legacy preoccupy the Detroit-raised rapper and producer Quelle Chris on his seventh solo album, *Deathfame*. The underground mainstay has been called everyone’s favorite rapper’s favorite rapper’s favorite rapper; here he wrestles with what that reputation entails, unpacking the satisfactions and sacrifices of quiet integrity. There’s skeptical indignation (“King in Black”) and smirking pride (“Feed the Heads”), but Chris leads with humility and grace on the gorgeous bluesy number “Alive Ain’t Always Living,” on which he makes clear, “You can keep the feast and wine. I just want my peace of mind.” That song extends a fruitful running partnership with the Oakland-based producer and pianist Chris Keys, although Quelle handles most of the album’s production himself, stretching his elastic flows with obtuse basslines and dusty drums. It’s bittersweet work, wry and wise, and destined for the longevity Chris ultimately claims as his goal.

When an artist consistently creates at the forward edge, there are no guardrails. Quelle Chris has been comfortable at the boundaries, leading Hip-Hop since he started. Quelle’s vision extends beyond genre or format. He continued broadening his creative ambitions even beyond his own legendary four album run (BYIG, Everything's Fine, Guns, Innocent Country 2) and worked with Chris Keys to compose part of the score for the Oscar-winning film “Judas and The Black Messiah” with director Shaka King. The new album, “DEATHFAME,” is a sonic treatment produced by Quelle himself, along with Chris Keys and Knxwledge. The record carries on like an incredible lost tape found at a flea market. It explores, unflinchingly, every moment of the trials the early 2020s has brought to all of us. Guests Navy Blue and Pink Siifu lend brilliance to the dynamic and unexpected new album coming May 13th on Mello Music Group.

Welsh producer/vocalist Kelly Lee Owens released her ultra-personal second album, *Inner Song*, in August 2020, in the thick of the pandemic. With any plans to tour the record scuttled, that winter she managed to decamp from her London home to Oslo—just before borders were closing again—for some uninterrupted studio time. Much like *Inner Song*’s rather short 35-day gestation, after a month of work with Norwegian avant-garde/noise producer Lasse Marhaug, Owens emerged with *LP.8*, her most experimental, liberating record yet. On her previous full-lengths—this is actually her third, not her eighth—Owens alternated between deep, plodding techno tracks and moody synth compositions, over which her lithe vocals floated effortlessly. But on *LP.8*, the contrasts—between the earthly and the ethereal—are felt more deeply. The opener, “Release,” plays like a lost Chris & Cosey cut, its crunchy precision finding that sweet spot between industrial and early techno. On the New Age-y “Anadlu,” “S.O (2),”and “Olga,” hints of Enya’s influence shine through, but the songs’ gauzy atmospheres are often counterweighted by brooding undertones. “Nana Piano” is a melancholy solo piano sketch, unfettered except for some gentle birdsong in the background. But the closing “Sonic 8” is Owens at her most direct and visceral: She channels all sorts of frustrations while intoning, “This is a wake-up call/This is an emergency” over a beat so skeletal and abrasive that it sounds like a frayed wire swinging dangerously close to the bathtub.

Born out of a series of studio sessions, LP.8 was created with no preconceptions or expectations: an unbridled exploration into the creative subconscious. After releasing her sophomore album Inner Song in the midst of the pandemic, Kelly Lee Owens was faced with the sudden realisation that her world tour could no longer go ahead. Keen to make use of this untapped creative energy, she made the spontaneous decision to go to Oslo instead. There was no overarching plan, it was simply a change of scenery and a chance for some undisturbed studio time. It just so happened that her flight from London was the last before borders were closed once again. The blank page project was underway. Arriving to snowglobe conditions and sub-zero temperatures, she began spending time in the studio with esteemed avant-noise artist Lasse Marhaug. Together, they envisioned making music somewhere in between Throbbing Gristle and Enya, artists who have had an enduring impact on Kelly’s creative being. In doing so, they paired tough, industrial sounds with ethereal Celtic mysticism, creating music that ebbs and flows between tension and release. One month later, Kelly called her label to tell them she had created something of an outlier, her ‘eighth album’. Lasse Marhaug is known for hundreds of avant-noise releases, previously working with the likes of Merzbow, Sunn O))) and Jenny Hval, for whom he produced her acclaimed albums Apocalypse, Girl, Blood Bitch and The Practice Of Love. A label mate of Kelly’s, Marhaug has recorded for Smalltown Supersound since 1997. Welsh electronic artist Kelly Lee Owens released her eponymous debut album in 2017 and followed this up with 2020’s Inner Song. She has collaborated with Björk, St. Vincent and John Cale. In April, she returns with LP.8.

For the Singapore-born singer and producer, virtual reality *is* reality. Her yeule persona, named for a *Final Fantasy* character, is something of a high-concept art-pop cyborg, a Tumblr kid-turned-Twitch streamer whose aesthetics draw from art-house anime, digital RPGs, and niche online subcultures like seapunk and witch house. Her second album, *Glitch Princess*, takes her sound even further down the post-Grimes cyber-pop rabbit hole; industrial screeches, 8-bit bleeps, and humanoid spoken-word interludes abound. (Five tracks feature co-production from Danny L Harle, a master at divining emotion from digital artifice.) “I like making up my own world/And the people who live inside me,” yeule murmurs like a shy Vocaloid in the opener, “My Name Is Nat Ćmiel.” But there’s a rawness pulsing through the project, a decidedly human heartbeat—most strikingly on “Don’t Be So Hard on Your Own Beauty,” a poignant indie-rock ballad hiding in the midst of the digital decay.

Mastered by Heba Kadry Mixed by Geoff Swan Purchase of the entire album includes a .pdf with a download for The Things They Did for Me Out of Love

a tape called component system with the auto reverse

Following 2019’s Still Young, frequent collaborators and friends Jeff Rosenstock & Laura Stevenson have returned with Younger Still, their 2nd 4-song EP of Neil Young covers. This time, the duo put their spin on classics “Comes a Time,” and “Everybody Knows This is Nowhere,” alongside deeper cuts like “Razor Love” and “Hey Babe.” The duo originally started working on a new EP in 2019, recording two of its four songs in Rosenstock’s apartment in Brooklyn before moving to Los Angeles. As the events of 2020 & the global pandemic unfolded, the EP was never fully realized and both musicians focused on their respective solo projects. Rosenstock released the critically acclaimed album NO DREAM and not-critically-acclaimed 2020 DUMP in 2020 (as well as the NO DREAM ska counterpart, SKA DREAM, in 2021), and continued focusing on writing and recording music for the Emmy-nominated Cartoon Network series, Craig of the Creek. While across the country in NY, Stevenson was busy as well. She gave birth to her first child and released her beautiful self-titled sixth album in 2021. Prior to this, Stevenson has been featured in outlets such as Pitchfork, SPIN, and NPR (Tiny Desk) and has toured with artists such as Lucy Dacus, The Hold Steady, and others. As soon as both of their intense schedules allowed, Stevenson hopped on a plane in the summer of 2022 and the duo got back together at Rosenstock’s home in Los Angeles to record four different songs for a whole new EP in the basement. Rosenstock & Stevenson will be hitting the road for a handful of intimate shows together in November and December, playing Neil Young covers and selects from both of their vast catalogs.

There’s a light but pervasive melancholy that surrounds *FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE*, Brian Eno’s 22nd solo album—a sense of weightlessness that feels both blissful and a little threatening. Are we cruising safely through the clouds or are our wings about to burn (“Icarus or Blériot”)? Are our lives too busy to consider the microscopic worms in the ground beneath our feet, especially when they don’t participate in capitalism (“Who Gives a Thought”)? How long will the world go on without us (“Garden of Stars”)? As much as these songs are elegies for a vanishing future, they’re also beautiful meditations on the fragility of the present—a mode Eno has been working in comfortably since the mid-’70s. The sound design is as beautiful and expansive as you’d expect, and Eno’s voice—an underrated instrument—is both common and quietly transcendent, the sound of a boy wandering an empty earth. He’s always interesting. But this is one of the first times in years he’s sounded so vital.

On *Small World*, Joseph Mount shrinks his scope. Whereas its predecessor, 2019’s *Metronomy Forever*, was a sprawling 17 tracks, *Small World* consists of just nine. “Often, I want to do the opposite of what I’ve just done,” Mount tells Apple Music. “I wanted to be really musically focused and concise.” This album’s title is, too, a reflection of the shrunken world in which it was made. Written in summer 2020—and recorded between November of that year and early 2021—these songs were crafted in the thick of the pandemic and explore loneliness (the Elliott Smith-meets-Red Hot Chili Peppers “Loneliness on the run”), the optimism we clung to (“Things will be fine”), and the incomprehensible weight of it all (“Life and Death”). This isn’t, however, a record to transport us back to the worst moments of lockdown. “The way I made music during the pandemic was to escape from feeling like I was in a pandemic,” says Mount. “This album is designed to be listened to when you’re free.” The soothing and organic sound of *Small World* might surprise listeners who’ve been with Metronomy since day one—not least because of Mount’s voice, which has dropped a few octaves, sounding at times like Benjamin Biolay’s or Serge Gainsbourg’s. “When I first started writing songs, I imagined I was a producer and that, one day, I would get a female singer to sing them,” says Mount who has, of course, since produced for artists including Robyn and Jessie Ware. “I would always sing in a falsetto voice and really high up. Even though it was never necessarily comfortable, it’s just what I did. This was me trying to be a bit more mature. I want to grow up with Metronomy. You’ve got to develop it and turn it into what you want it to be.” Read on as Mount guides us through his seventh album, one song at a time. **“Life and Death”** “This was the last thing I wrote for the record. I felt like I’d mined the experiences of being locked down for nice songs. And I hadn’t really done anything that acknowledged the actual gravity of the situation, and just how horrible it is and how many people died. This is my song, which is supposed to be a bit despairing about everything. But like all the songs on the record, the music isn’t supposed to make you feel bad or upset. It’s meant to be supportive.” **“Things will be fine”** “The first thing I wrote for the record. It encapsulated everything I wanted it to be, in terms of the sound and the lyrics. I’ve got two children and I was having to say to them, ‘Everything is going to be OK.’ But I had no knowledge that backed that up. It’s also about when you’re young, and for the first time you realize that the world is quite a horrible place. And then you realize you’ve been protected by your parents, which is what they’re there to do.” **“It’s good to be back”** “I was imagining this character, a musician who’s in their late thirties, trying to write a record that connects with young people. I was imagining a fictitious conversation with a record label: ‘Oh, you want to reach the kids? You need to use drum machines and synthesizers.’ And then doing that but putting in an acoustic guitar. Which, to me, is this really fun juxtaposition of ideas. The song was about being back at home, and about when our tours were canceled or postponed. When you come back from being away, it always takes a week or two to lock back into the same routines with one another.” **“Loneliness on the run”** “‘Loneliness on the run’ is a song about being far away from people that you love. And wanting them to try and manage their bad feelings. I wrote something about visualizing your loneliness, or your anger, and then throwing it out the window or chasing it away. So, that was the idea. At the end of this song, I guess the album does shift a gear and it becomes a little less introspective and starts forgetting the bad stuff.” **“Love Factory”** “I liked the idea of industrializing love, making it this thing which is churned out. This factory is operating at astonishing capacity. We are doing incredibly well at creating love here. It’s supposed to be a relentless song to reflect that.” **“I lost my mind”** “It’s about feeling like you are doubting your own sanity. It’s not something that I’ve felt, but during the pandemic, it was something that I was very aware of—how friends of ours in quite different situations were just in apartments, on their own, feeling very isolated and out of touch. I wanted it to feel like it was following that in the music as well. It does wig out, and I decided to put a whistling sound in, which helped push it over the edge.” **“Right on time”** “The other thing about imagining where I want to be in a few years is also this awareness that you can’t keep writing songs about falling for people because it’s happened. It happened a long time ago. Having said that, the next two songs on the album are exactly that. But I think they’re going to be the last songs I write like it. It’s just another mindlessly optimistic song about enjoying the sunshine. I remember the summer of 2020. It was super hot. Everyone suddenly had this realization that, yes, you can be unable to see your family and be suffering with all kinds of stuff, but it’s unbelievably sunny and nice outside. Just finding somewhere where you can have the sun hitting your face makes you feel better.” **“Hold me tonight” (feat. Porridge Radio)** “The first demo I have of the song is just my voice and a guitar. It was a Velvet Underground-style thing I was thinking of: very sparse. Relatively near the end of recording the album, I was listening to this song, and I was like, ‘We should just restart and have someone else singing it.’ I thought it should be a girl’s voice and they should be singing about their side of this story, which is, of course, going to be that you love each other and everything’s great. I sent Dana \[Margolin, of Porridge Radio\] the track and what she sent back was this totally ruined situation where she turned the whole thing on its head. She turned it into something absolutely genuine for her, and it rescued the song for me in a way.” **“I have seen enough”** “I thought I’d try and write a song in French, and the idea for it was about the horror of life—but how you can’t look away. It’s too beautiful at the same time. And in the end, the French wasn’t really good enough, so it’s English! To nutshell it, it’s about just enjoying and appreciating what you have around you. And I guess the way that it would relate to the pandemic is just all of the horrors that were going on and still being able to find pleasurable things. Finding happiness within it all.”

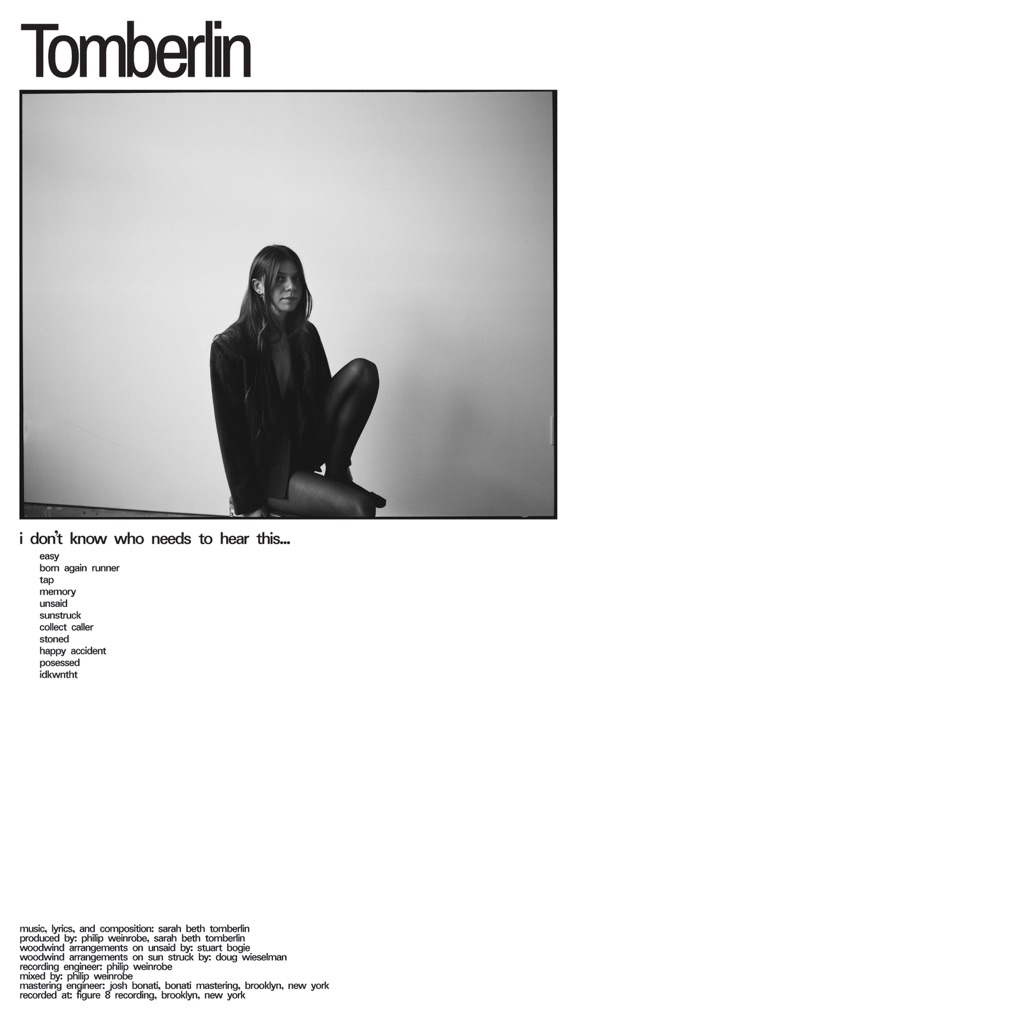

Tomberlin, the moniker of indie folk artist Sarah Beth Tomberlin, might’ve titled her second full-length LP *i don’t know who needs to hear this…*, but she knows who did: “I did,” she tells Apple Music. “On this record, there’s a lot of searching for space for myself,” she says. “A lot of my songs are me holding up a point-and-shoot camera that has the focus ability, zooming in and zooming out on these small moments.” Before this album, the Baptist pastor’s daughter wrote songs about faith and self-doubt from the distance of her own loneliness; her first full-length, 2018’s *At Weddings*, was acclaimed for its spareness, the way she could write a sacred moment in a fingerpicked guitar riff. Now she’s developed a new language for relationships, and blows it up to enormous size with orchestral instrumentation: horns and Una Corda (“easy”), pedal steel (“born again runner”) and tenor saxophone (“collect caller”). The record is her exploring “just how to be in the world,” she says. “I just turned 27 and *At Weddings* was when I was 21. This is a different chapter of life, with new circumstances and things to investigate.” Below, Tomberlin walks through her album, track by track. **“easy”** “I wrote this song on acoustic guitar, and it was very simplistic. I wanted it to have a little bit more of a being-at-sea feeling, of rocking out in the ocean, rudderless. I remember telling Philip \[Weinrobe\], who co-produced with me, that I didn\'t want it to be a guitar song. We had already been using the Una Corda, this certain kind of piano, on the record. I loved how it sounded—eerie, but really beautiful as well. We combined those two elements and we kind of built it out from there. We turned all the lights off and had candles lit. It was very witchy. We were all in a circle, in this room, with the mics in front of us—really listening, not being too loud so the instruments didn\'t bleed into each other.” **“born again runner”** “The title is attributed to an Emmylou Harris song, \'Born to Run,\' which my dad always says reminds him of me. It\'s a song for him. It\'s a song about loving my dad and wanting to have a relationship with him, even though we\'re very different people.” **“tap”** “I moved to New York in September 2020. I assimilated by going on really long walks through the city, across the Williamsburg Bridge and into Brooklyn, on the West Side Highway, by the water. I was missing being in the country and the woods. I was trying to find ways to connect myself. The first line I had for the song was ‘I\'m not a tree/I\'m in a forest of buildings.\' It\'s about things that disconnect us. I was thinking of how narrative singers can struggle with wanting to put ourselves in a good light. No one is a perfect person. We also pulled a bunch of twigs and grass and flowers from the garden and were hitting the drums with them, so it has this extra brushy, freaky, witchy thing going on.” **“memory”** “I actually did a session with Danny Harle—he co-produced Caroline Polachek\'s record \[*Pang*\]. He wanted to meet when I lived in LA, so we rented a studio space and he was like, \'It\'s no pressure. Let\'s just hang out and see if something happens.\' We spent maybe three hours working on music, and it was just us meeting really for the first time. I really liked the lyrics that I came up with, and that\'s how I wrote that song, which was wild to me. I was really stressed out about writing something with someone in the room. It\'s like writing a paper when the deadline is the next day and somehow you write something good.” **“unsaid”** “It was February \[2020\], before everything went to shit. I wrote it about LA and trying to figure out how to be planted there, because it\'s not really a city. In my opinion, it\'s just this sprawl. It was really hard for me to know how to feel grounded there. It\'s beautiful and fake. Making that song was like trying to comfort myself.” **“sunstruck”** “This one is definitely about examining a relationship with a person that was sputtering on again, off again. A lot of time had passed, we were still friends, and I got some recent news about some changes in their life, and a desire to work on themselves. It was a magic thing to hear, and that song fell out afterwards. I felt released from that relationship. And often, growth comes from being uncomfortable, some drought and some storms. It is a bit mournful of examination, but it ends in a hopeful way.“ **“collect caller”** “Stuart \[Bogie\], who is in fact a legend of New York, plays saxophone on this song, and wow. He came in for a couple songs. I kept saying, \'I’ve collected all the deep-feeling musicians for this record,\' because some people can play an instrument well, but some people, they\'re so mathematical about playing. We somehow collected the people that just deeply feel the music, and Stuart is one of those people. I love him.” **“stoned”** “‘Stoned’ I wrote when I was feeling a bit exasperated—anger but trying to have compassion. I think the anger that I was feeling was just and right, but I didn’t want to become hardened by it. I wasn\'t a big partier growing up; no one\'s asking the pastor\'s kid to go rage. But I was a young adult at this time, and living in Louisville, and someone invited me to a party. It was like, oh, this is in my John Hughes movie, everyone is jumping in the pool, taking their clothes off. I was walking away from it barefoot, drenched wet, holding my shoes, the sun was coming up, it was probably 5 am. When I started writing this song, I was thinking about that moment a lot, of experiencing this fun thing, but actually being in my head. Walking away from it alone and feeling very alone.” **“happy accident”** “\[Cass McCombs\] invited me to come jam one day. I played him some new stuff and he actually hit up Saddle Creek being like, \'Hey, does Tomberlin need someone to produce? I\'m interested in working with her,\' which blew my mind. He\'s a legend to me. I knew that I wanted to recruit Cass for this song, and he played on \'stoned\' as well. On \'stoned,\' I\'m playing the lead rhythm guitar and he\'s doing all the solo-y stuff.” **“possessed”** “I think it\'s cool to have a really short song. I need to get better at that. It\'s really a private song, almost trying to motivate myself. Writer’s block vibes. I thought it would be a fun intro to the record for a while. It\'s really cinematic to draw it back a bit. Each song is its own world, and I love that about different records, and I wanted it to be this way. But there is a sonic thread that sews it together throughout.” **“idkwnthat”** “I was walking around in Brooklyn and going through my voice memos and clicked ‘new recording 430’ or whatever. I don\'t label them. I\'m sitting by the window playing guitar; I sound really tired. I\'m singing that song to myself. Even though I\'m saying, \'I don\'t know who needs to hear this,\' obviously I did. That was the first song that we recorded in the process of the record. Everyone says it\'s a weird time. I feel like it\'s always a fucking weird time to be alive as a person in the world, but especially right now, I guess. This record does go through a flurry of different feelings and emotions. It\'s good to feel all of them. So it felt like a perfect way to end the record.”

Chicago rapper/producer Saba’s first full-length since 2018’s critically acclaimed *CARE FOR ME* looks existentially inward instead of projecting outward. Whereas its predecessor was often perceived through the lens of grief, with his cousin John Walt’s tragic death weighing considerably on the proceedings, his third album explodes such listener myopia with a thoughtful and thought-provoking expression of American Blackness. Though its title might suggest scarcity on a surface level, these 14 songs exude richness in their textures and complexity in their themes. “Stop That” imbues its gauzy trap beat with self-motivating logic, while “Come My Way” gets to reminiscing over a laidback R&B groove. His choice of collaborators demonstrates a carefully curated approach, with 6LACK and Smino bringing a sense of community to the funk-infused “Still” and fellow Chicago native G Herbo helping to unravel multigenerational programming on the gripping “Survivor’s Guilt.” The presence of hip-hop elder statesman Black Thought on the title track only serves to further validate Saba’s experiences, the connection implicitly showing solidarity with sentiments and values of the preceding songs.

Faye Webster announces Car Therapy Sessions, an EP of new and re-imagined songs by Webster recorded at Spacebomb Studios with a 24 piece orchestra. The orchestra was headed by Trey Pollard who was responsible for both conducting and arranging, and Drew Vandenburg produced and mixed the EP. Car Therapy Sessions will be available digitally on 29th April and on vinyl in the fall. “I have a vivid memory of walking around London in 2018 listening to a mix of Jonny, which I had just written. I remember thinking “I want to perform this song with an orchestra”. I truly have had my heart set on it since then, always talking about it and figuring out how or when to make it happen,” says Webster. On the EP, Webster reimagines three songs from her critically acclaimed 2021 release I Know I’m Funny haha and 2019’s Atlanta Millionaires Club. The songs “Kind Of”, “Sometimes” and “Cheers” take on a cinematic and glimmering new sheen. In addition to the title track -“Car Therapy” - she also shares a sprawling and emotional work - “Suite: Jonny” - which combines fan-favorites “Jonny” and “Jonny (Reprise).” The two songs originally appeared on the Atlanta Millionaire’s Club tracklist, two different views on the same narrative. Here they’re presented together. It’s remarkable how beautifully Webster’s work can take on this orchestral treatment. Like Cole Porter, or Judy Garland - her delicate and emotional delivery packs a gut punch when dramatized by the EP’s robust arrangements.

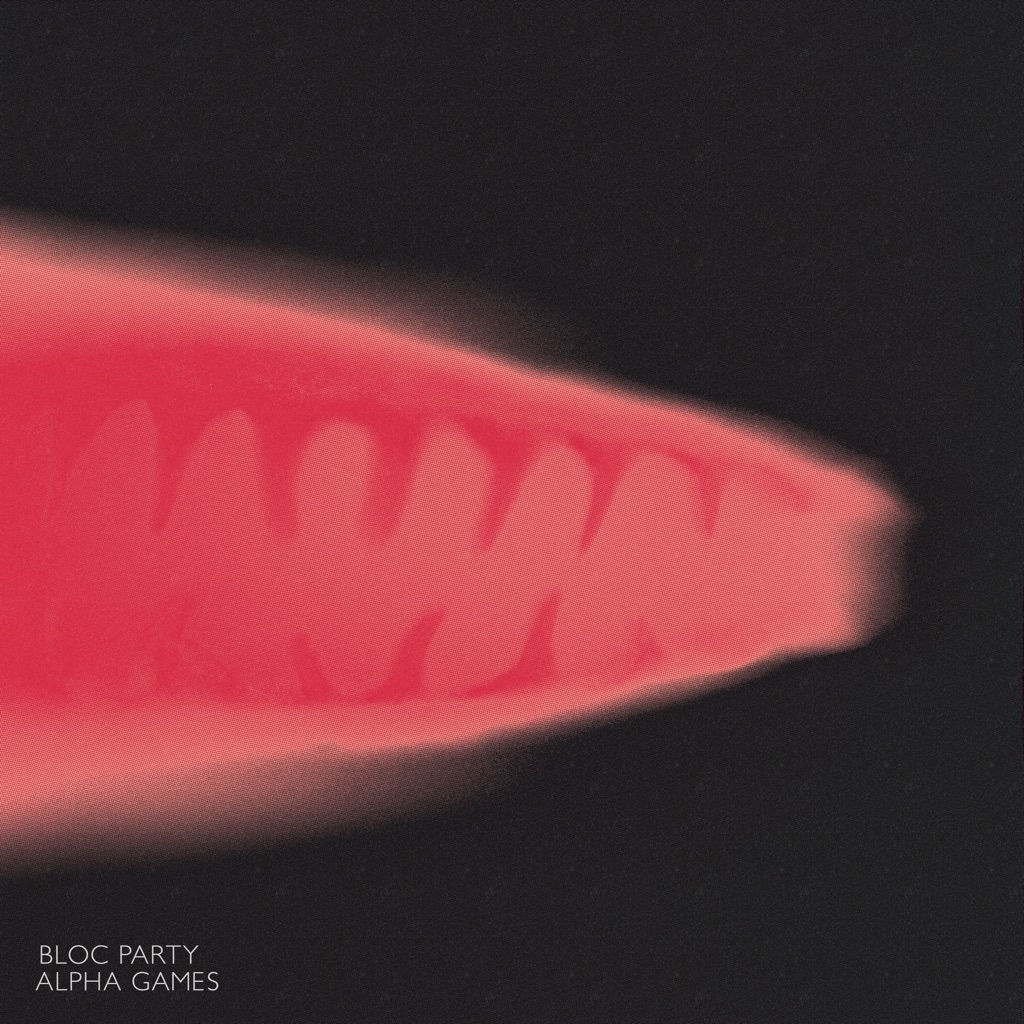

Kele Okereke isn’t usually someone who looks backwards. “As soon as we finish a record and deliver it, that’s usually the point I stop listening to it as it becomes someone else’s,” Bloc Party’s singer/guitarist tells Apple Music. However, during 2018 and 2019, the band revisited their past as they played their debut album, 2005’s *Silent Alarm*, in full at live dates around the world. During sound checks, new music began to emerge—tracks that would eventually appear on their sixth studio album, *Alpha Games*. “The energy we were putting into the *Silent Alarm* songs, which were in our blood and our muscle memory, felt connected to these new songs on some level,” he says. Despite that genesis, *Alpha Games* is still a forward-looking record—not least because it’s the first to be truly made by this iteration of Bloc Party, with Okereke and fellow founding member Russell Lissack (guitar) joined by Justin Harris (bass) and Louise Bartle (drums). While the latter duo have been in post since 2015, previous album *Hymns*, made in 2016, was largely written by Okereke and Lissack, in the studio and directly into a computer. “We could manipulate anything any way that we felt like, and that can be quite eye-opening,” Okereke says. “But we knew this record needed to *feel* different, which it soon did, thanks to the spontaneous alchemy that came from four different personalities and perspectives coming together. The magical part of writing songs with other people is that you don’t know where you’re going to end up.” Where they’ve ended up is as captivating as it is diverse. *Alpha Games* takes in hulking riffs (“Traps”), undulating grooves (“Callum Is a Snake”), cinematic electronica (“Sex Magik”), and brooding post-rock (“The Girls Are Fighting”)—all tied together by unifying themes of conflict and anger, dishonesty and duplicity. “There’s something fascinating about menacing things going on beneath the surface,” says Okereke. Let him guide you through the record, track by track. **“Day Drinker”** “It was two separate ideas that I could see potential in but needed to be finessed. In the final production session before we recorded the album, it all slotted into place. Lyrically, it really encapsulates what I see the record as being about: this kind of struggle for dominance. And what better way to exhibit and explore that than in the relationship between siblings? It’s about two warring siblings, an older brother who’s jealous of his younger brother’s success. We were able to carry that idea through in the instrumental section towards the end. The way that Russell and I are following each other with our guitar lines was, to me, supposed to signify two brothers dueling.” **“Traps”** “Justin had an idea for a version of the bassline, which we heard something in and added more parts around it. As it took shape, we’d play it in sound checks, and whenever we did, all of our crew would stop and listen. We knew then that there was something arresting about it. It gave us an indication of where we should be going with the album.” **“You Should Know the Truth”** “I like it because the musical refrain is so sweet and childlike but the words are so dark. It feels like one of the darkest things that I’ve ever sung, insomuch as it’s about coming clean after years of living a lie and the harm that can produce. But I love that most people won’t really get that \[meaning\]—if they don’t listen to the words then it’ll just be a pretty song. I quite like that, because a lot of my favorite music, like the Pixies, has such rousing melodies and violent imagery, marrying the dark and the light.” **“Callum Is a Snake”** “Callum is a real person, for sure, but Callum is not his real name. I think the song is less about him than it is about putting someone on blast, knowing that you’ve been fucked over and not wanting someone to get away with it. It’s about a very calm and calculated bout of aggression towards someone, because you can see what they’re doing and they need to stop, otherwise there will be consequences.” **“Rough Justice”** “This was one of the songs in which I could see lots of different scenes, like vignettes, as if I was a narrator watching them come together. I didn’t have a clear vision about what it was about, but looking back now I can see. It brings to mind a passage from the Bret Easton Ellis novel *Glamorama*, in which we find out that all of these socialite party people are actually an underground terrorist cell. That always stuck with me—that sense of there being a public face and a private face.” **“The Girls Are Fighting”** “The conflict here is about two women coming to blows because someone has been selling them dreams and lying to them, in order to get something he wanted out of them. That’s a theme that recurs throughout the record. It was a fascinating thing for me to explore, because I’ve always found those moments when people drop their masks of politeness, and real passion or violence erupts, to be strangely attractive.” **“Of Things Yet to Come”** “I guess it’s the most tender of the songs on the record. We were conscious that we wanted *Alpha Games* to have no lags and for all the energy to be up, but I feel like this is the one song when the energy isn’t up. It’s important because although there isn’t such palpable aggression in it, there is a tremendous sense of regret at the way life has panned out—and looking back wistfully and recognizing that you could have been a better person to someone.” **“Sex Magik”** “This song is ultimately about a very short-lived relationship—actually ‘tryst’ is probably a better word—with someone, without being fully aware of what they’re entirely about. You then recognize that you’re being led down a path that you’re not really sure you should be going down. Both ‘Sex Magik’ and ‘Traps,’ to me, feel quite sexual, but from different perspectives. In ‘Traps,’ it’s quite predatory: The singer is looking at someone he wants to take advantage of. In ‘Sex Magik,’ though, it’s the opposite side of that experience—someone realizing that maybe they’re being taken advantage of.” **“By Any Means Necessary”** “To me, it’s about ruthless ambition and knowing that you’ll stop at nothing to achieve what it is you’re setting out for, even at the cost of your humanity. That song feels like an assassin, psyching themselves up before the hit.” **“In Situ”** “Although ‘In Situ’ was one of the earlier songs we wrote, we didn’t really develop it properly until the end of the process. I was left with a bit of freedom, lyrically, so wrote them on the fly. It’s about this sense of inertia—this sense that after the pandemic, a lot of people reconciled what was going on in their lives. It’s about feeling you’re in your habitat, your space, having this life that has a sense of routine. I was sleeping in the same bed, not on a tour bus, so I was feeling quite domesticated. I think there was part of me that was worried the moss would grow over me and I’d forget what I’d done for such a big part of my life.” **“If We Get Caught”** “It definitely has a whimsical edge to it, but there’s a sense of impending doom. Although it’s a beautiful sentiment, about this tender moment between two people, there is this sense that very soon the shit is going to hit the fan. ‘If We Get Caught’ is like a final goodbye—a moment of tenderness before heads start to roll.” **“The Peace Offering”** “There’s all this rage and angst and conflict within the songs prior, but in ‘The Peace Offering’ there’s a sense of cold detachment. What happens after the fires of rage burn out and you’re left numb and disconnected? This song is about that feeling of letting your hate go but not letting love come into its place. Sometimes you have to cauterize the wound and move on. It’s ultimately about not looking for forgiveness, realizing that you’re never going to agree and that maybe it’s better to just part.”

Kele Okereke isn’t usually someone who looks backwards. “As soon as we finish a record and deliver it, that’s usually the point I stop listening to it as it becomes someone else’s,” Bloc Party’s singer/guitarist tells Apple Music. However, during 2018 and 2019, the band revisited their past as they played their debut album, 2005’s Silent Alarm, in full at live dates around the world. During sound checks, new music began to emerge—tracks that would eventually appear on their sixth studio album, Alpha Games. “The energy we were putting into the Silent Alarm songs, which were in our blood and our muscle memory, felt connected to these new songs on some level,” he says. Despite that genesis, Alpha Games is still a forward-looking record—not least because it’s the first to be truly made by this iteration of Bloc Party, with Okereke and fellow founding member Russell Lissack (guitar) joined by Justin Harris (bass) and Louise Bartle (drums). While the latter duo have been in post since 2015, previous album Hymns, made in 2016, was largely written by Okereke and Lissack, in the studio and directly into a computer. “We could manipulate anything any way that we felt like, and that can be quite eye-opening,” Okereke says. “But we knew this record needed to feel different, which it soon did, thanks to the spontaneous alchemy that came from four different personalities and perspectives coming together. The magical part of writing songs with other people is that you don’t know where you’re going to end up.” Where they’ve ended up is as captivating as it is diverse. Alpha Games takes in hulking riffs (“Traps”), undulating grooves (“Callum Is a Snake”), cinematic electronica (“Sex Magik”), and brooding post-rock (“The Girls Are Fighting”)—all tied together by unifying themes of conflict and anger, dishonesty and duplicity. “There’s something fascinating about menacing things going on beneath the surface,” says Okereke. Let him guide you through the record, track by track. “Day Drinker” “It was two separate ideas that I could see potential in but needed to be finessed. In the final production session before we recorded the album, it all slotted into place. Lyrically, it really encapsulates what I see the record as being about: this kind of struggle for dominance. And what better way to exhibit and explore that than in the relationship between siblings? It’s about two warring siblings, an older brother who’s jealous of his younger brother’s success. We were able to carry that idea through in the instrumental section towards the end. The way that Russell and I are following each other with our guitar lines was, to me, supposed to signify two brothers dueling.” “Traps” “Justin had an idea for a version of the bassline, which we heard something in and added more parts around it. As it took shape, we’d play it in sound checks, and whenever we did, all of our crew would stop and listen. We knew then that there was something arresting about it. It gave us an indication of where we should be going with the album.” “You Should Know the Truth” “I like it because the musical refrain is so sweet and childlike but the words are so dark. It feels like one of the darkest things that I’ve ever sung, insomuch as it’s about coming clean after years of living a lie and the harm that can produce. But I love that most people won’t really get that [meaning]—if they don’t listen to the words then it’ll just be a pretty song. I quite like that, because a lot of my favorite music, like the Pixies, has such rousing melodies and violent imagery, marrying the dark and the light.” “Callum Is a Snake” “Callum is a real person, for sure, but Callum is not his real name. I think the song is less about him than it is about putting someone on blast, knowing that you’ve been fucked over and not wanting someone to get away with it. It’s about a very calm and calculated bout of aggression towards someone, because you can see what they’re doing and they need to stop, otherwise there will be consequences.” “Rough Justice” “This was one of the songs in which I could see lots of different scenes, like vignettes, as if I was a narrator watching them come together. I didn’t have a clear vision about what it was about, but looking back now I can see. It brings to mind a passage from the Bret Easton Ellis novel Glamorama, in which we find out that all of these socialite party people are actually an underground terrorist cell. That always stuck with me—that sense of there being a public face and a private face.” “The Girls Are Fighting” “The conflict here is about two women coming to blows because someone has been selling them dreams and lying to them, in order to get something he wanted out of them. That’s a theme that recurs throughout the record. It was a fascinating thing for me to explore, because I’ve always found those moments when people drop their masks of politeness, and real passion or violence erupts, to be strangely attractive.” “Of Things Yet to Come” “I guess it’s the most tender of the songs on the record. We were conscious that we wanted Alpha Games to have no lags and for all the energy to be up, but I feel like this is the one song when the energy isn’t up. It’s important because although there isn’t such palpable aggression in it, there is a tremendous sense of regret at the way life has panned out—and looking back wistfully and recognizing that you could have been a better person to someone.” “Sex Magik” “This song is ultimately about a very short-lived relationship—actually ‘tryst’ is probably a better word—with someone, without being fully aware of what they’re entirely about. You then recognize that you’re being led down a path that you’re not really sure you should be going down. Both ‘Sex Magik’ and ‘Traps,’ to me, feel quite sexual, but from different perspectives. In ‘Traps,’ it’s quite predatory: The singer is looking at someone he wants to take advantage of. In ‘Sex Magik,’ though, it’s the opposite side of that experience—someone realizing that maybe they’re being taken advantage of.” “By Any Means Necessary” “To me, it’s about ruthless ambition and knowing that you’ll stop at nothing to achieve what it is you’re setting out for, even at the cost of your humanity. That song feels like an assassin, psyching themselves up before the hit.” “In Situ” “Although ‘In Situ’ was one of the earlier songs we wrote, we didn’t really develop it properly until the end of the process. I was left with a bit of freedom, lyrically, so wrote them on the fly. It’s about this sense of inertia—this sense that after the pandemic, a lot of people reconciled what was going on in their lives. It’s about feeling you’re in your habitat, your space, having this life that has a sense of routine. I was sleeping in the same bed, not on a tour bus, so I was feeling quite domesticated. I think there was part of me that was worried the moss would grow over me and I’d forget what I’d done for such a big part of my life.” “If We Get Caught” “It definitely has a whimsical edge to it, but there’s a sense of impending doom. Although it’s a beautiful sentiment, about this tender moment between two people, there is this sense that very soon the shit is going to hit the fan. ‘If We Get Caught’ is like a final goodbye—a moment of tenderness before heads start to roll.” “The Peace Offering” “There’s all this rage and angst and conflict within the songs prior, but in ‘The Peace Offering’ there’s a sense of cold detachment. What happens after the fires of rage burn out and you’re left numb and disconnected? This song is about that feeling of letting your hate go but not letting love come into its place. Sometimes you have to cauterize the wound and move on. It’s ultimately about not looking for forgiveness, realizing that you’re never going to agree and that maybe it’s better to just part.”

CLBBNG features four remixes including “Nothing Is Safe,” from There Existed An Addiction To Blood, the group’s horrorcore album of 2019, which has a dance remix, and an instrumental rework (titled "Drop Low"); Meanwhile, remixes of “Get Up” (titled “Get Mine”), and “Dominoes” (titled “Drop That”) from CLPPNG, the group’s Sub Pop debut of 2014, round out the tracklisting. Clipping has wanted to make a record of dance remixes for some time, and inspiration struck when they performed what has to be the all time tiniest desk concert (see for yourself!) for NPR Music’s Tiny Desk Concert. Jonathan Snipes elaborated further, “I had come up with the name CLBBNG mostly as a joke when we made the first album for Sub Pop (titled CLPPNG). I made a couple of remixes back then (none of the tracks released in this volume), but some combination of losing interest and getting distracted by other projects meant that we didn't release them at the time. When we recorded drums with Chukwudi Hodge for "Say the Name" in 2019, we also had him play a four-on-the-floor disco beat over the top of the "Nothing is Safe" instrumental with the idea that someday we'd make a sprawling dark-disco Moroder-esque version of the song. When we were asked to do "Tiny Desk" I thought maybe it was the time to finally make that track. Soon after we were asked to do another virtual performance inside Minecraft, and I thought it would be fun to make more dance remixes and create an entire "CLBBNG" club/rave set. It's versions of these edits and remixes that have made it on to this, the first CLBBNG EP. I have a deep love and appreciation for dance music, and I relish any excuse to make it myself. It's a lot of fun to bring those sensibilities to clipping songs, and I'm excited to continue making CLBBNG releases in the future.” Additionally, four of Clipping’s songs, including the “Nothing Is Safe” remix, are being featured on a new app developed with Modify Music which also launches today on iOS and Android app stores. This is a real time mixing app, that has each song separated into four “stems” that can be mixed on the fly. Alongside the original stems, the listener will have the option to switch out and mix in alternative stems that Jonathan Snipes produced just for the app. The app can be found here: modifymusic.com/artists/clipping/

In early 2020, Turnover were touring Europe fresh off a US tour for their new album, Altogether. As the pandemic caused borders to begin closing in around them, the band cut the tour short and got one of the last flights home - not knowing stages around the world would be dark for almost two years. Since 2012, the band has been touring full time, averaging 200 shows each year. In their time away from the road, the band had the opportunity to explore and deepen aspects of their lives that they hadn’t been able to in the past. “I tried to be as positive as possible about the change in my life. Instead of thinking about the things covid was taking from me I wanted to focus on what it could give me,” says singer Austin Getz. The title track of the band’s new album, Myself in the Way, speaks to this mindset. “I can’t put myself in the way of love again,” sings Getz, “I promise I’m going to go all the way with you,” is specifically about Getz getting engaged to his longtime partner, but applies to the general outlook he had toward life in lockdown. “I was living in Sebastopol, California at the time and felt like I truly lived there for the first time since I wasn’t leaving for tour. I was able to go meditate at the Zen Buddhist dojo down the road, run and bike around the hills in Sonoma county, learn about plants and gardening, take some Spanish and arboriculture classes, and get involved with the volunteer fire department. Just do a bunch of new things to challenge and inspire me in a natural way.” Turnover’s other members also used the time to deepen interests they hadn’t been able to fully explore before covid. Bass player Dan Dempsey was in New York City and responded to lockdown by spending more time practicing his visual art in drawing and painting. He painted the album’s cover during this period and developed a style that has become a central theme for the band in its current iteration. Drummer Casey Getz found work at a Virginia Beach state park as touring continued to be postponed. He was in search of and inspired by having a work-life balance different than he’d experienced since he was younger. Through this, he was able to nurture current relationships more and find new ones, something touring made much more difficult. This led to Casey playing drums with a group of longtime friends in Virginia Beach and further developing his drumming style - adding a new prowess for fluidity and improvisation through lengthy jam sessions with the group. Guitarist Nick Rayfield was focused on sharpening his guitar and piano playing and was able to devote energy to skateboarding and his retail business more than he had been able to for the last few years. This was also the band’s first album with Rayfield making songwriting contributions after touring with them for years as a live member, adding a new creative element to the songs. Over 18 months Turnover weaved these individual experiences into a collective work, recording the LP over two sessions with longtime collaborator Will Yip at Studio 4. Austin is credited, for the first time, as co-producer. “I had specific ideas for sound design on this album. I knew a lot of sounds I wanted to hear and use. We wanted everything to be able to be heard and have its own place. I was inspired by the way Magical Mystery Tour and Dark Side of the Moon sounded. We decided to go a lot wider with it and utilize panning and stereo more than we had in the past, while also wanting it to sound tighter and smaller than some of our earlier records. We were inspired by drum and bass sounds from Chic and Quincy Jones records from the 70s, so we put the drums in the control room to get them to sound smaller. We used an active pickup bass and a jazz bass to get that percussive sound from the bass so the low end wasn’t as rumbling and subby. We let the synths share some of that low end that the drums and bass gave up. Quincy's approach to arrangements were a huge inspiration in this record as well. The horn and string lines I wanted to sound like classic era disco, mixed with modern synth and vocal sounds. I had been experimenting with my own vocal styles a lot and utilized autotune and vocoder on this album almost as instruments on certain songs as a stylistic choice.” The band has always been DIY, but post pandemic they have taken that to a different level. They appreciate more than ever how lucky they are to get to be together and have fun creating things with their friends. They have found that they are usually best suited for executing their own vision, not only musically, but with all its accompaniments as well. For this album they made all their own videos in collaboration with friends and using Dempsey's drawings and paintings. Change is authentic and true to Turnover as a band and as individuals. Chart a course through their discography and find a band continually reinventing themselves with a unique artistic ambition. Myself In The Way arrives finding Turnover doing the same within their own persons, pushing the band into new and exciting parallel depths of expression.

Alongside Moor Mother’s 2021 album, *Black Encyclopedia of the Air*, *Jazz Codes* explores the question of how accessible a generally inaccessible artist can get without sacrificing the density of their ideas. It isn’t to say it’s easy music (45 tightly collaged minutes of spoken word, free jazz, electronic loops, and fragmentary hip-hop)—only that it makes space for the listener in ways she hasn’t always in the past. Given the album’s subject matter—jazz history, the nature and place of Black art—it’s easy to hear the shift as one from personal expression to stewardship and communication: She wants you to understand where she’s coming from as a gesture of respect to those who came before, whether Woody Shaw (“WOODY SHAW”), Mary Lou Williams (“ODE TO MARY”), or Joe McPhee (“JOE MCPHEE NATION TIME”). Her fellow travelers—multi-hyphenate Black artists like AKAI SOLO and Melanie Charles—show you she isn’t alone. And while the difficulty lingers, it gets explicit purpose, courtesy of professor, artist, and activist Thomas Stanley on the outro: “Ultimately, perhaps, it is good that people abandoned jazz/Replaced it with musical products better-suited to capitalism’s designs/Now jazz jumps up like Lazarus if we allow it, to rediscover itself as a living music.”

Called “the poet laureate of the apocalypse” by Pitchfork, Moor Mother is announcing ‘Jazz Codes'. Coming out on July 1, it is her second album for ANTI- and a companion to her celebrated 2021 release ’Black Encyclopedia of the Air‘. ’Jazz Codes’ uses poetry as a starting point, but the collection moves toward more melody, more singing voices, more choruses and more complexity. In its warm, densely layered course through jazz, blues, soul, hip-hop, ’Jazz Codes’ sets the ear blissfully adrift and unhitches the mind from habit. Through her work, Ayewa illuminates the principles of her interdisciplinary collaborative practice Black Quantum Futurism, a theoretical framework for creating counter-chronologies and envisioning Black quantum womanist futures that rupture exclusionary versions of history and future through art, writing, music, and performance. Moor Mother - aka the songwriter, composer, vocalist, poet, and visual artist Camae Ayewa – is also a professor at the University of Southern California's Thornton School of Music. She released her debut album Fetish Bones in 2016 and has since put out an abundance of acclaimed music, both as a solo artist and in collaboration with other musicians who share her drive to dig up the untold. She is a member of many other groups including the free jazz group Irreversible Entanglements, 700 bliss and moor jewelry. She has also toured and recorded with The Art Ensemble of Chicago and Nicole Mitchell.

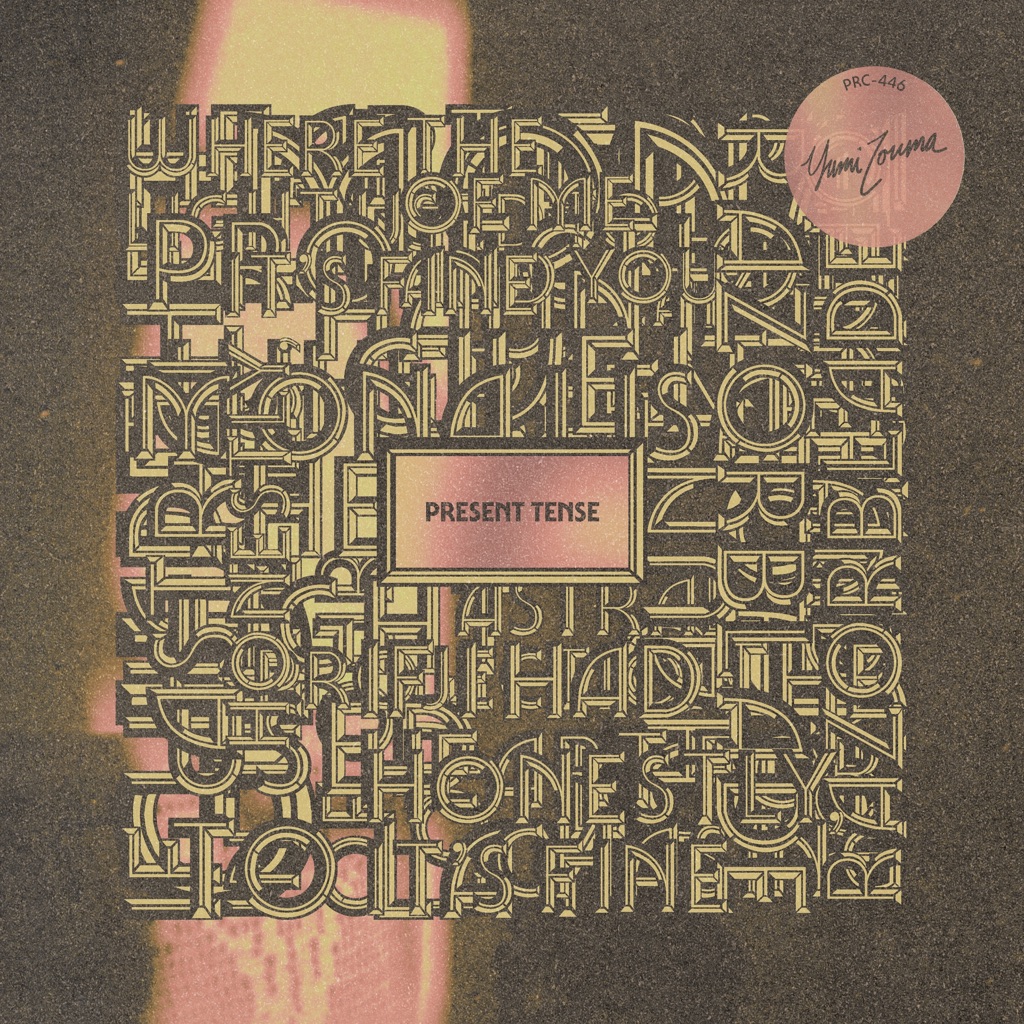

Yumi Zouma’s Josh Burgess likens the band’s songwriting process to gardening, “Someone brings in a seed and through collaboration, it grows into a song that is vastly different from its original form.” Like any garden, this one requires dedicated tending, a practice that seems rather inconvenient if not straight-up difficult, considering the fact that the four members live in disparate parts of the world – calling New York, London, and New Zealand home – but long-distance has always been a feature of their songwriting process, not a bug. Their new album, Present Tense, is the product of those efforts, a work Christie Simpson describes as “a gallery wall displaying these different moments in each of our lives. A process of curation, revisiting the past and making it relevant to the present.” You might assume that while some artists have struggled to rethink their processes during a pandemic, Yumi Zouma would be perfectly suited to lockdown, but the opposite proved to be true. Without looming tour dates driving them to release new music, the prolific band found themselves at a standstill. On the day that the World Health Organisation declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the band released their third LP, Truth or Consequences, via Polyvinyl, and had sold out their first American tour. After Yumi Zouma’s first show in Washington DC, the tour was canceled and the four members went their separate ways, an experience memorialized on Present Tense opener “Give It Hell.” “It was disorientating,” Charlie Ryder admits. “We generally work at a quick clip and average about a record a year, but with no foreseeable plans, we lost our momentum.” So they set a date. By September 1st, 2021, the album needed to be finished, regardless of whether they’d be able to tour it or even meet to record together. Before the September deadline goaded the band into action, they had what felt like endless amounts of time to record the album. What began in fits and starts became a committed practice again as Yumi Zouma dug through demos from as early as 2018 to collaborate on and make relevant to the peculiar moment in time the band, and world, was experiencing. “The lyrics on these songs feel like premonitions, in some regards,” Simpson reflects. “So much has changed for us, both personally and as a band, that things I wrote because the words sounded good together now speak to me in ways I didn’t anticipate.” Remote and in-person sessions in studios in Wellington, Florence, New York, Los Angeles, and London all played a role, and Yumi Zouma brought in new collaborators from different disciplines to broaden their sound. Studio recordings of drummer Olivia Campion were incorporated into every song, while pedal steel, pianos, saxophones, woodwinds, and strings were played by friends around the globe who were able to lend their talents and support. The band enlisted multiple mixers in Ash Workman (Christine & The Queens, Metronomy), Kenny Gilmore (Weyes Blood, Julia Holter), and Jake Aron (Grizzly Bear, Chairlift), and recruited the mastering expertise of Antoine Chabert (Daft Punk, Charlotte Gainsbourg) for the first time. “This is our fourth album, so we wanted to pivot slightly, create more extreme versions of songs,” Ryder says. “Working with other artists helped with that, and took us far outside of our normal comfort zone.” You can hear the impulse on “In The Eyes Of Our Love,” a song that’s seemingly twice as fast as any prior release, and closer to the classic rock of Dire Straits than the dream pop aesthetics that the band has built their career on so far. Campion’s drums crash in hard from the outset, sending the accompanying band into a revelry that only breaks upon arriving at the first bridge, when Simpson sings: “But we won’t lose sight of what we said/ I'll sing from the dirt instead.” There’s a defiance heard throughout Present Tense, a refusal to bend to what might seem fated, communicated not only through lyrics but in the boldness of these arrangements, metamorphosing between tracks without ever losing momentum. The triumphant chorus of “Where The Light Used To Lay” belies any of the pain beneath its surface, a technique Simpson likens to the work of folk-adjacent rock acts like Bruce Springsteen and Phoebe Bridgers. “We wanted quiet moments to give into a big, brash chorus, something that approaches cliché,” Simpson says. “The chorus feels like a dramatic encapsulation of who we want to be as a band,” Ryder adds. Two years away from the road gave Yumi Zouma a new appreciation for the friendship they’ve sustained and the opportunity an abundance of time off-cycle offered. “We used to run on adrenaline, and if a song wasn’t working we’d just nip it in the bud and move on. This process gave us the opportunity to really sit with songs and rethink them until they felt like they belonged in the collection,” Burgess says. Album closer “Astral Projection” is one such song, originally conceived by Burgess, who felt as if he’d been handed a sliver of brilliance after the song had been rewritten and abandoned by Ryder and Simpson. “It was as if I’d been given this rescue cat who had the potential to be great,” he says, laughing. Between them, the song developed into a bass-driven slowburner, moody and oddly prescient,“A hint of panic can do wonders for distance,” Simpson sings, her voice mirrored by Burgess’s. The outro twinkles like a summer skyline at dusk, violets and grays intermingling with the bright glow of a thousand open windows. “I daydream about playing that one live,” Burgess says. “In bed, I’ll close my eyes before sleep and imagine the drumbeat kicking in.” It’s a craving the members of Yumi Zouma all share, one they hope will be satiated someday soon. Dedicated to an embattled past, Present Tense is the band’s offering to a tenuous future.“To 2020, and the memory of all that was lost,” they write in the album’s liner notes. “Kia Kaha.”

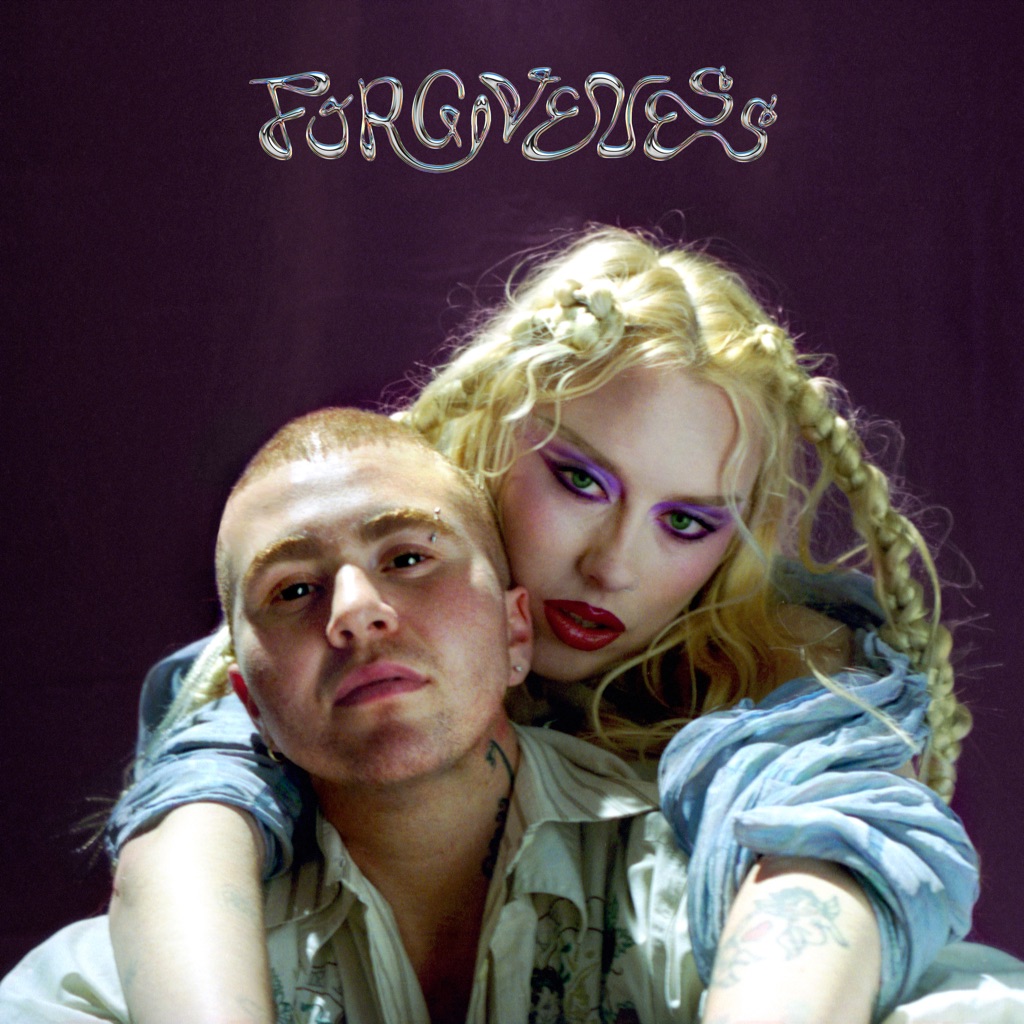

In the near-decade since LA-based best-friend duo Girlpool, Avery Tucker and Harmony Tividad, infiltrated the indie pop-rock scene with their gorgeous harmonies and punky melodies as teenagers, a lot has changed: They instituted additional instrumentalists, they started veering away from their charmingly minimal and diaristic songwriting, and Avery began transitioning before their third LP, *What Chaos Is Imaginary*. *Forgiveness*, the pair’s fourth full-length, is the product of that growth. Their ear for sparse composition has evolved; instead of speaking world-weary truths in the space between spiky guitar riffs, they’ve grounded their sincerity in ethereal production, spacey synth, and songs that interrogate gender, relationships, and everything in between. Once celebrated for their youthful exuberance, Girlpool has never lost their heart, they’ve simply gained wisdom.

Shygirl toyed with simply self-titling her debut album, but *Nymph* felt far more evocative—and fitting. “A nymph is an alluring character but also an ambiguous one,” the artist and DJ, whose real name is Blane Muise, tells Apple Music. “You don’t quite know what they’re about, so you can project onto them a little bit of what you want.” Co-written with collaborators including Mura Masa, BloodPop®, and longtime producer Sega Bodega, it’s an album that defies categorization, its stunning, shape-shifting tracks blending everything from rap and UK garage to folktronica and Eurodance. Along the way, it reveals fascinating new layers to the South London singer, rapper, and songwriter. While *Nymph* contains moments that match the “bravado” (her word) of earlier EPs *Cruel Practice* and *ALIAS*, Shygirl says this album is “ultimately the story of my relationship with vulnerability.” As ever, sensuality is central, but she resists the “sex-positive” label. “With a track like ‘Shlut,’ I’m not saying my desire is good or bad,” she says. “I’m just saying it’s authentically who I am.” Read on as Shygirl guides us through her beguiling debut album, one song at a time. **“Woe”** “This song is me acclimatizing to the audience’s presence and how vocal they are. Sometimes it’s annoying to have all these other voices \[around you\] when you’re trying to figure out your own. But then, on the flip of that, isn’t it nice that people actually want something from you? I often do that: give myself space to express some frustration or an emotion, then look at it in different ways. Sometimes I do that with sensitivity, and sometimes I’m just taking the piss out of myself. Like, ‘OK now, just get over it.’” **“Come For Me”** “For me, this song is a conversation between myself and \[producer\] Arca because we hadn’t met in person when we made it. She would send me little sketches of beats, then I would respond with vocal melodies. Working on this track was one of the first times I was experimenting with vocal production on Logic, manipulating my voice and stuff. It was really daunting to send ideas over to Arca because she’s such an amazing producer. But she was so responsive, and that was really empowering for me.” **“Shlut”** “I said to Sega \[Bodega\], ‘I want to use more guitar.’ I love that style of music, more folky stuff, because I used to listen to Keane and Florence + the Machine in my younger days. So, that’s definitely an undercurrent influence here, but the beat is a horse galloping. The horse was a very prevalent idea when I was making this album because it’s this powerful animal that is oftentimes in a domestic setting being controlled by someone. At the same time, there’s an element of choice in that relationship because the horse could easily not be tamed. I love that and relate to it a lot.” **“Little Bit”** “I have to give Sega credit for the beat. The way I work, mostly, is in the same room \[as my collaborators\], and we start from scratch. When most producers send me beats, I’m not inspired by them. But when Sega plays me stuff, I’m like ‘Wait, no—can I have that?’ I think because we started working together in 2015, he can probably anticipate what I want now. I never imagined hearing myself on a beat like this. It reminds me of a 50 Cent beat, which takes me back to my childhood. So, even the way I’m rapping here is nostalgic. I’m being playful and inserting myself into a sonic narrative that I didn’t think I would occupy.” **“Firefly”** “I started this song with Sega and \[producer\] Kingdom at a studio in LA, but then Sega had to leave for some reason. I was feeling a bit childish because I was like, ‘What’s more important than being in this room right now?’ So, then, with just me and Kingdom, I was like, ‘If I was going to make an R&B-style song, this is what it would sound like.’ I’d been listening to a lot of Janet Jackson, and I’d just watched her documentary. But really, I was kind of just taking the piss as I started freestyling the melodies. I really like being a bit flippant with melodies and not being too formulaic.” **“Coochie (a bedtime story)”** “The title is a Madonna reference. When I was shooting a Burberry campaign last year, her song ‘Bedtime Story’ was playing on repeat. It became the soundtrack to this moment where I was acclimatizing to a space \[in my career\] that was bigger than I had anticipated. I started writing this song at an Airbnb in Brighton with Sega and \[co-writers\] Cosha, Mura Masa, and Karma Kid. We were up super late one evening, and I was just sitting there, humming to myself. And I was like, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to have a cute song about coochie?’ Growing up as a girl, there’s not even a cute word for \[your vagina\]. Everything is so sexualized or anatomical. I was like, ‘I need to make this cute song that I would have liked to hear when I was younger.’” **“Heaven”** “This track is quite experimental. The production started quite garage-y, but then it got weird fast. And then we reworked it again because I wanted it to sound sweet. I was thinking about when I broke up with my ex-boyfriend; there were moments where I was like, ‘Can we just forget everything and get back together?’ Obviously, you can’t just forget everything—it’s childish to want to erase those parts, but I can have that space in my music. In some moments, my ex was my peace and my place of absolute escape. And that’s what I equated to heaven at that point.” **“Nike”** “This is me revisiting my childhood, being that teenager at the back of the bus. It started when \[co-writer\] Oscar Scheller played me this recording he’d made of girls talking on the bus, and in the original production, we even had that \[chatter\] in there. You know when a girl is talking and saying nothing but also saying everything? I was that person! My friends used to ask me for advice about stuff I had no experience in, and I would dish it out with such vim. I thought it would be funny to dip back into that space on this track and be playful with it. Because no matter how sensitive I get, there is always this part of me with real bravado.” **“Poison”** “I love Eurodance music. When I DJ, it’s what I play the most. I just find it really fun and sexy and flirtatious, and I relate to the upfront lyrics. Some of my audience probably isn’t as familiar with my musical references here, such as Cascada and Inna, so it’s fun to introduce them to that sound a little bit. And I love that we found a real accordion player to play on the track. I really enjoy the tone and texture that you can get from using a real instrument.” **“Honey”** “I made this track predominantly with \[producer\] Vegyn. It came out of a real jam session where we had music playing in the room, and I was speaking on the mic over it. You get the texture of that as the song starts. There’s a lot of feedback that reminds me of The Cardigans and stuff with that ’90s electronica vibe. For me, this track is all about sensualness. I had this idea of being in an orgasmic experience that keeps on intensifying, so I wanted to replicate that sonically. That’s why I’m repeating myself a lot and why the melody tends to rearrange just a little bit as I rearrange the order of the words as well.” **“Missin u”** “This song is about me being annoyed at my ex-boyfriend. We’d broken up like six times, and we weren’t even together at this point, and I was just being really petulant about that. I write poems when I’m feeling any intensity of emotion, and so I wrote this poem where I was just really dismissive of the whole situation. Then, when I was in the studio with Sega, I put the poem to the beat he was working on. I wanted this track to feel a bit disruptive at the end of the album. Because no matter how sensitive I get, there is also this sharper energy to me and my approach to lyrics.” **“Wildfire”** “This track has a very Joshua Tree title because I wrote it with Noah Goldstein at his house there. I was imagining looking across a bonfire at someone I don’t even know but kind of fancy and seeing the fire reflecting in their eyes. I romanticize situations a lot in this way, so this song is really me riffing off that idea. It’s main-character syndrome, I guess! I don’t really like closed beginnings and endings. If I was to write a story, I would always give myself space for it to continue, and I think ‘Wildfire’ does that a little bit. That’s why it’s the final track.”