Indieheads Best of 2022

Highest voted albums from /r/indieheads in 2022, Reddit's Indie music community.

Source

Burial’s music has always been steeped in atmosphere; the omnipresent sounds of vinyl hiss, rainfall, and cavernous reverb are as much a part of his signature as cut-up breakbeats and mournful vocal melodies. But until *Antidawn*, the UK producer’s work had almost always remained rooted in dance music. This five-song, 44-minute EP—long enough to qualify as his third album, if he wanted it to—definitively breaks with the club. Like 2017’s *Subtemple / Beachfires*, *Antidawn* strips away virtually everything resembling a beat, save for a few brief rhythmic flourishes, so muted they’re barely noticeable beneath the static. What’s left is a purely ambient swirl of brooding synthesizers, crackling white noise, and eerily processed vocal snippets. It can be pretty doleful going: “Nowhere to go,” murmurs a voice in the opening “Strange Neighbourhood.” “I’m in a bad place,” intones another in “Antidawn.” But as is usual for Burial, even the blackest cloud is ringed with blinding light: Church organs suggest a hint of uplift, and many of his chords are major, rather than minor. All five tracks unspool like discrete parts of a single overarching composition; they’re murky enough that it can become easy to feel lost in the fog, casting about for a recognizable landmark. But even at his bleakest, Burial’s world radiates a sense of calm. The overall effect is as hypnotic as it is haunting: Burial distilled to his most desolate essence.

Antidawn reduces Burial’s music to just the vapours. The record explores an interzone between dislocated, patchwork songwriting and eerie, open-world, game space ambience. In the resulting no man's land, lyrics take precedence over song, lonely phrases colour the haze, a stark and fragmented structure makes time slow down. Antidawn seems to tell a story of a wintertime city, and something beckoning you to follow it into the night. The result is both comforting and disturbing, producing a quiet and uncanny glow against the cold. Sometimes, as it enters 'a bad place', it takes your breath away. And time just stops.

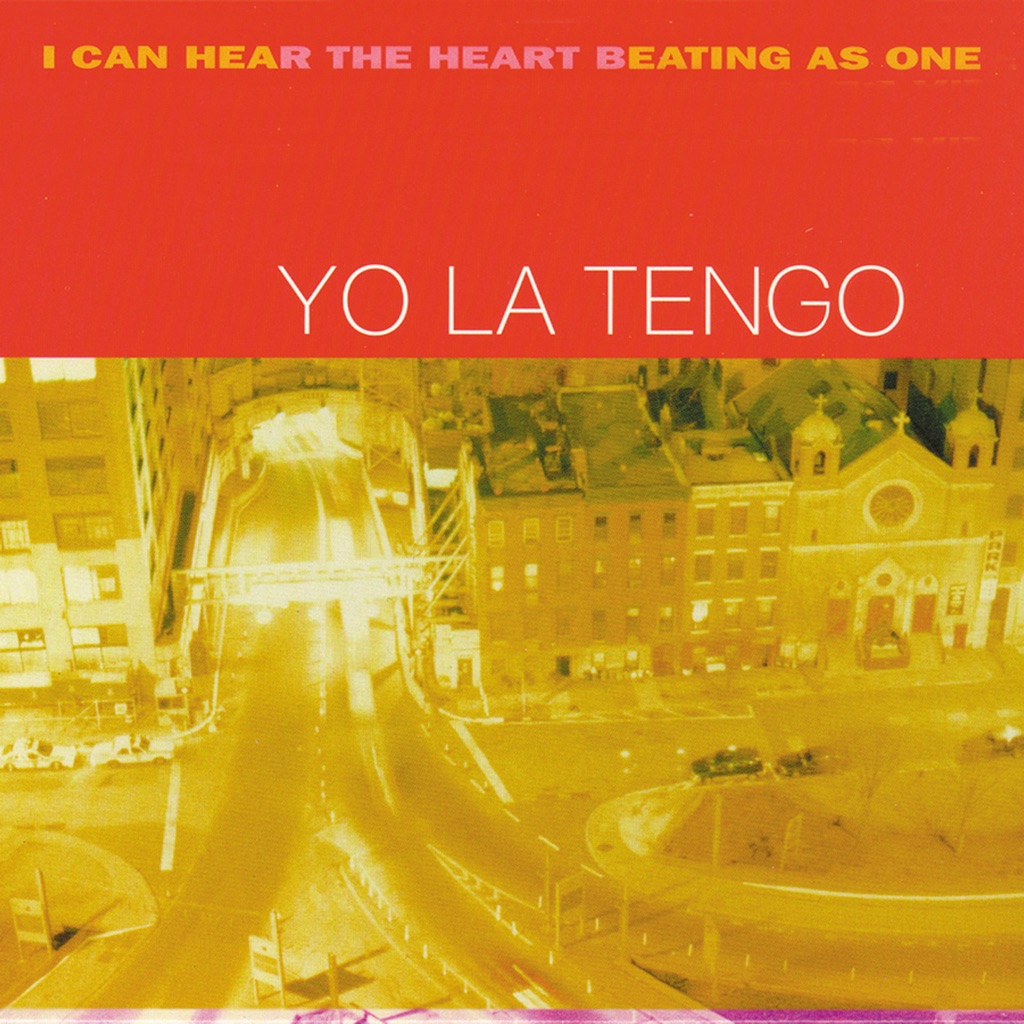

Years before the term “curator” entered the conversation as shorthand for artists who organize what’s already around them instead of generating something altogether new, the New Jersey-based indie band Yo La Tengo were curators: a group who seemed to take their influences more seriously than their originality, who brought together disparate styles—cheeky bossa nova (“Center of Gravity”), noisy Beach Boys covers (“Little Honda”), 10-minute drones (“Spec Bebop”), and two-minute country pop (“One PM Again”)—in ways that felt whole. To 21st-century ears, the range of *I Can Hear the Heart Beating as One* might sound familiar—after all, with the musical universe at your fingertips, why not listen to everything?—but in 1997, it was a quiet revolution: Here was indie rock without guitars (“Autumn Sweater”) and feedback-heavy art songs made by the quiet family who runs the corner store or lives upstairs (“We’re an American Band”). The template isn’t so much the pop album as the mixtape or playlist—a form that, when done well, can open your ears to new sounds and connections. And while they sing about romance with sweetness (“My Little Corner of the World”) and reticence (“Shadows”), you feel their bond the most when they say nothing at all (“Green Arrow”).

Today, Yo La Tengo’s undeniable classic 1997 album I Can Hear the Heart Beating as One is a quarter of a century old. To celebrate, a digital deluxe version of the album is released today offering a smorgasbord of extras: the band’s 1997 Peel Session featuring live takes of “Autumn Sweater,” “Shadows,” and a 9-minute pass through “I Heard You Looking,” as well as remixes of “Autumn Sweater” by µ-Ziq, Kevin Shields, and members of Tortoise, many of which have not previously been made available for streaming. “I remember that I wanted it sounding pretty organic, which is why I recorded it to a cassette and pitched it about a bit,” recalls µ-Ziq’s Mike Paradinas. “It really is all over the place.”

Part of the pleasure of exploring Sonic Youth is hearing how their instrumental passages evolved over the years, from the compacted intensity of stuff like “Expressway to Yr. Skull” to the looser, more meditative sound of “The Diamond Sea” and “Wildflower Soul.” Recorded between 2000 and 2010, the five tracks on *In/Out/In*—lengthy, improvised, focused but serene—are, at the least, interesting archival material from a band rarely ever less than great. But they also form a Venn diagram of the disparate territories the band yoked together: classic-rock groove (“Basement Contender”) and free-form noise (“Social Static”), music for headbanging (“Out & In”) and for daydreaming (“In & Out”). At the end of the punk-rock rainbow, they found the hippie’s freedom; at the horizon of the avant-garde, they found a backbeat.

*NOTE - For physical bundles with exclusive shirts, please visit sonicyouth.kfu.store (North America/non-EU ROW) and shop.bingomerch.com (EU)* In mulling over their career, it’s staggering to realize that Sonic Youth not only delivered a healthy slab of releases as a unit but also have a myriad of shelved material still waiting for broader ears. While the group’s current Bandcamp abode lays out a generous amount of it, a bunch more has yet to surface. And it’s a massive mountain to chip away at in the sense of the group output alone; individual members’ projects are a whole other game, needless to say. "In/Out/In" ably delivers a new slab of mostly-unheard Sonic righteousness, with a scope on the post 2000-era band in especially zoned/exploratory regions. The 80’s and 90’s continually saw Sonic Youth reminding everyone that their jams ran free alongside song craft and visible development album to album; there were Peel excursions, dipping toes into soundtrack work starting with 1986’s "Made In USA", and of course great impromptu expansive takes of tried and true previous material onstage. The millennial establishment of home turf studio spaces in NYC then NJ greatly egged on forays into improvisation and composition on their own clock as evidenced in "Goodbye 20th Century" and the plethora of SYR releases that trickled out side by side between major release albums. At this juncture they had already created a cultural template for a whole new breed of rock heads who, in turn, entered a feedback loop to SY itself, which cultivated more of its own new moves informed by the very fandom they had for their acolytes all the while pushing the band outward to uncharted fields. Jim O’Rourke’s residency had already influenced the band’s material in part into denser, longer, meditative paths. Mark Ibold’s entry for their swan song "The Eternal" also allowed for more of this exploration with Kim Gordon having more room to commit to third guitar. However "The Eternal" also took more cues from Ibold’s bottom-end swing and perhaps dialed back the expansiveness of the "NYC Ghosts and Flowers" and "Sonic Nurse" era a notch in a cool way, making it one of the best group efforts for me, anyway. Perhaps this fueled some of these tracks here, in an already comfortable zone with a new lineup and new drive to take sideroads to even more outer realms. "In/Out/In" reveals their last decade to be still heavy on the roll-tape and bug-out Sonic Youth. Not all recorded in one session but rather spread out over 2000-2010, the sequencing here is especially well thought out. Opening with the 2008 “Basement Contender” we get a super-unfiltered glimpse of the band at Kim and Thurston’s Northampton house creating a gentle springboard of Venusian choogle, with phased Lee lappings at cascading Thurston figures forming a simmering soundtrack. “Machine” offers another instrumental track from "The Eternal" sessions and is a steamy exercise in stop-start rhythmic grunt amidst a jungle of chiming and upward spiraling chord progressions. We’ve also got the extended score offering “Social Static” from the Chris Habib/Spencer Tunick film of the same name, draping white sheets of noise over your head then descending into a gauzy maw of car-alarm guitars and ambient-yet-disruptive turbulence that eventually subsides into a smoky coda. Two more tracks round out the set both culled from a Three Lobed box set of various artists from 2011 called "Not the Spaces You Know, But Between Them": “In & Out” quietly resembles Can in a cave with dripping stalactites of Kim’s wordless tone rumble and was recorded at a soundcheck in Pomona California and their home Hoboken turf in 2010. “Out & In” from 2000 was done in their late downtown NYC studio and serves to close out this LP’s last 12 minutes as a reminder of what they got up to with O’Rourke there. More gentle time shift chord framework erupts into molten fury three minutes in, before mutating into the sonic equivalent of a slowly collapsing star. Casting an audio net over the entire instrumental/outtake oeuvre of Sonic Youth’s long history isn’t something easily committed to a single release without a doubt. Hearing these tracks in comparison to, say, 1986’s "Made In USA" material shows the massive leaps they took over the years. Whereas ’86 showed them freshly discovering their go-with-the-flow instrumental abilities for a soundtrack, their last decade showed them complementing the ambience with assured twists and turns that only came to be through their inimitable and rooted telepathy. That, plus the freedom to compose in more comfortable environs other than dank Ludlow Street rental spaces (hard to believe "Daydream Nation" was created in a claustrophobic practice basement) most assuredly was a component in their continued paths of discovery. Shifting on the drop of a dime from quiet/deep forays into full on noised-out Autobahn stomps with Steve Shelley at the wheel, they painted detailed and varied brush strokes and continually created organic sounds that undoubtedly carried the signature sound of the band, while ringing loud with their continual drive to free themselves from just that. Enjoy this capsule. -Brian Turner, 2021-

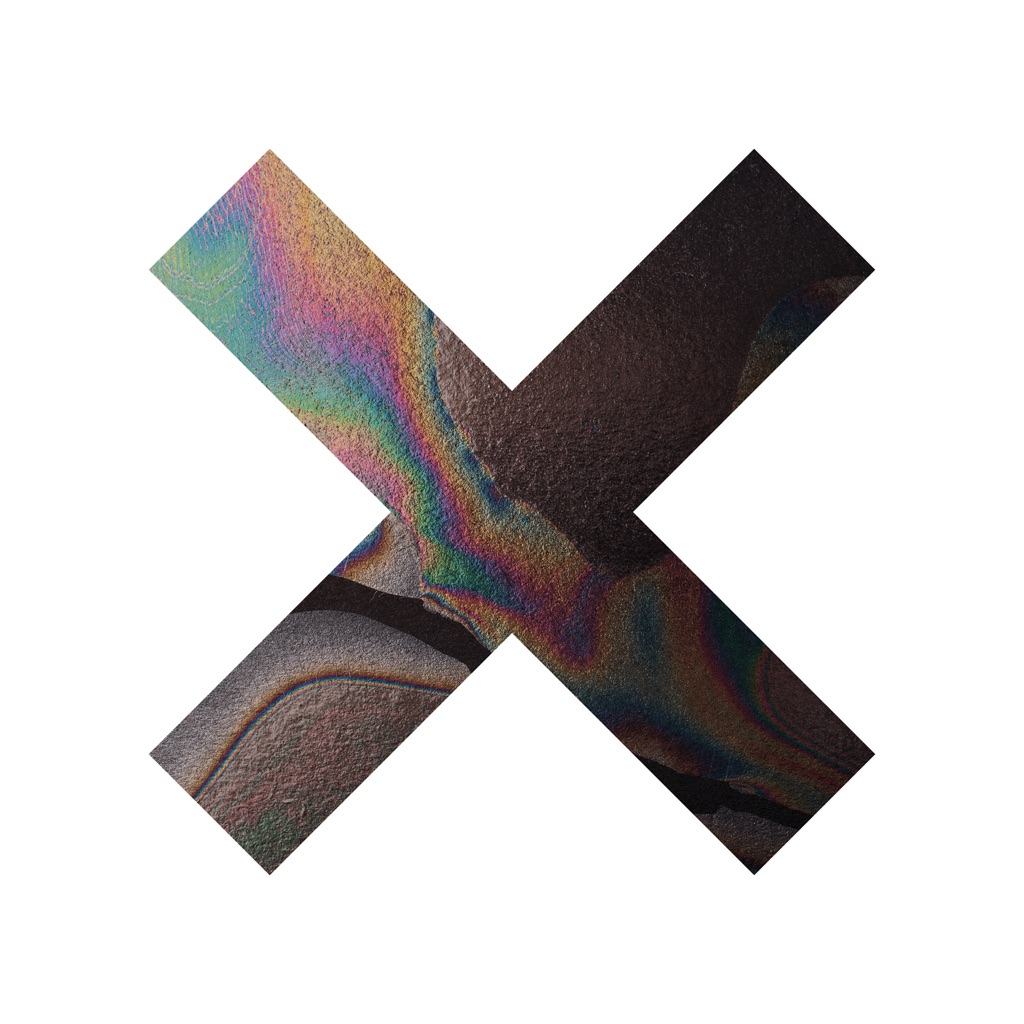

With Coexist, The xx defied any perceived "difficult second album" pressures to create a record that cemented their status as a truly global breakout act. On the follow up to their acclaimed, era-defining debut, the London based trio of Romy Madly Croft, Oliver Sim and Jamie Smith (aka Jamie xx) continued to deal in compelling, sparse atmospherics but expanded their musical world, especially through producer Jamie's growing electronic sound palette. Coexist surpassed expectations to become the best-selling vinyl record of 2012. Meanwhile, the band progressed from playing intimate venues to becoming an international must-see live act, curating their own festivals and collaborating with symphony orchestras. A final ambitious run of 25 shows at New York's legendary Armory venue rounded off the album campaign, witnessed by fellow artists (such as Beyonce, Jay-Z and Madonna) and fans alike. To celebrate 10 years of Coexist, The xx will release a limited edition, crystal clear vinyl pressing of the record, available to pre-order now. An expanded digital edition will also feature live versions of fan favourites "Angels", "Chained', "Reunion & Sunset" - find both here: thexx.ffm.to/coexist-deluxe

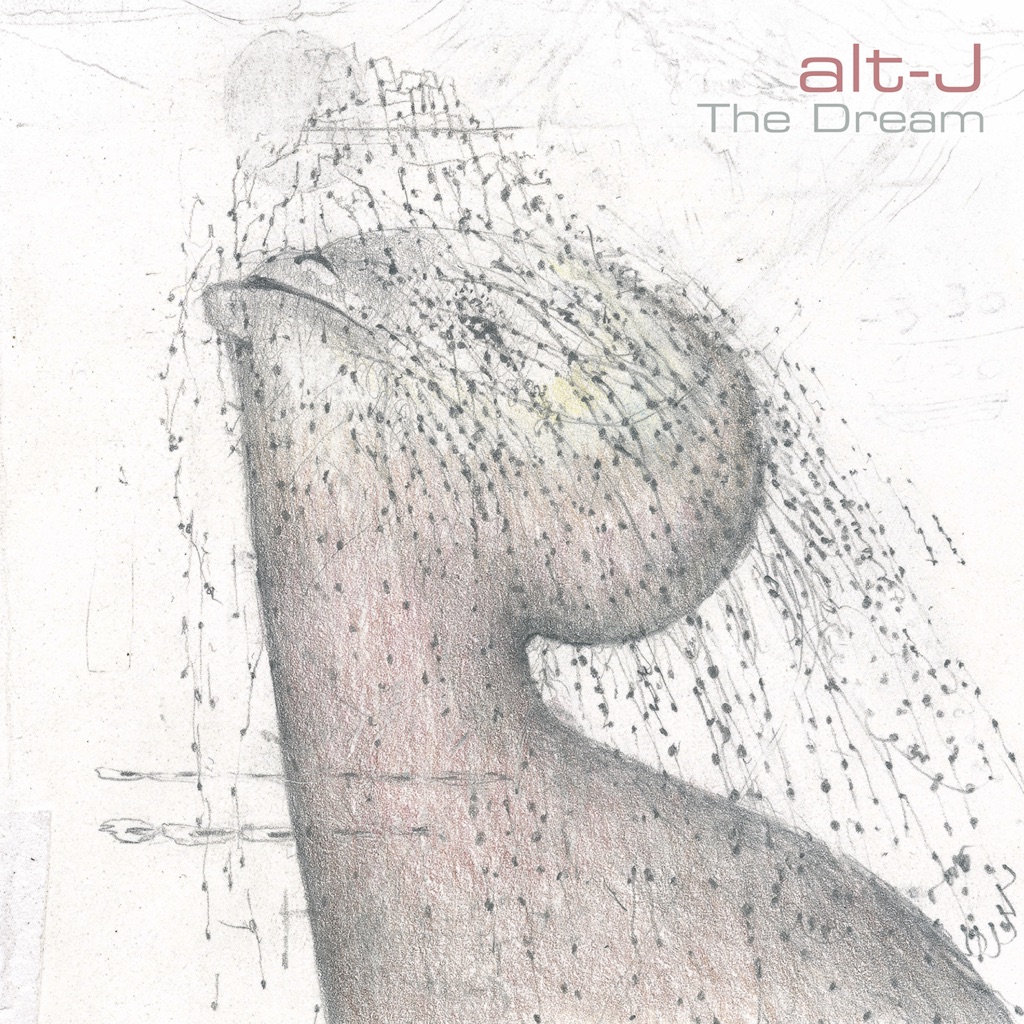

The body count on alt-J’s fourth album is high. At least three songs portray a death, another (“Losing My Mind”) explores the psyche of a serial killer, and “Get Better” is an intensely moving depiction of grief. That said, *The Dream* also delights in the pleasures of drinking Coke (“Bane”), instant attraction (“Powders”), and getting wasted at festivals (“U&ME”). “If you want to move people, it’s with storytelling,” singer/guitarist Joe Newman tells Apple Music. “You want to tell the best story, and that is by giving people both sides of the coin.” Here, that storytelling is set to characteristically adventurous music. The Leeds-formed trio finds improbable tessellations between pneumatic art-rock and Stravinsky, psychedelic folk and Chicago house, and Jimi Hendrix and Cormac McCarthy, binding those patterns with iron-strong hooks. “We’ve always seen ourselves as cowboy writers,” says Newman. “We don’t know how to write a pop song, but we know that we have catchy ideas. So we just sew them together, regardless of whether it makes much sense structurally. Maybe in this album, we’re also mastering the craft of writing more traditionally.” Pre-add *The Dream* now—once it’s released on February 11, the complete album will arrive in your library.

There’s something they don’t tell you about virality: It never seems to last. Beach Bunny, the Chicago-based indie-rock band fronted by Lili Trifilio, blew up on TikTok when the songs “Prom Queen” and “Cloud 9” (the latter from their 2020 debut LP, *Honeymoon*) made the rounds. But this is a band of pop songwriters—led by Trifilio’s undeniable ability to write a hook—and so, on Beach Bunny’s sophomore LP, they’re out to make a more permanent name for themselves. Backed by Fall Out Boy producer Sean O’Keefe, *Emotional Creature* is all “emotional experiences,” says Trifilio. “And viewing them in a positive, empowering light or feeling deeply shameful—it ties into a greater theme of how we, as humans, feel things,” and how social relationships influence those feelings, be it the Y2K Disney pop of “Entropy,” the rush of a crush on “Fire Escape,” or the proggy sci-fi synth detours of “Gravity” and “Scream.” “I hope it brings relatability,” Trifilio says of the album, “and maybe acts as a cathartic experience for people going through similar things as me. Music’s healing in that way, if you find tracks that resonate.” Below, Trifilio walks Apple Music through *Emotional Creature*, track by track. **“Entropy”** “There’s one Jonas Brothers song called ‘Burnin’ Up,’ and it has this transitional lead into the song. It kind of fades in, in a cool way. And with Kelly Clarkson and Avril or any of the big acts of the time, I think I was pulling from a vibe more than trying to mimic anything. The song has a late-’90s, early-2000s feel. I was leaning into that and trying things and seeing what worked and would fit that vibe.” **“Oxygen”** “I wanted to separate the verses and the choruses, and make the verses have that anxiety undertone—not just lyrically. I wanted the guitar riff a little more chaotic. The choruses are the breakthrough moment in this song where these reflections come together and it’s like, ‘OK, everything’s fine. Don’t stress out so much.’ It took me a while to write, just because it’s quite wordy. It was this ongoing poem, notes in my phone. Once it flowed, I was like, ‘OK, this is a pretty good song. We can put this on the album. It’s not just chaotic word vomit.’” **“Deadweight”** “‘Deadweight’ feels like a sequel to some *Honeymoon* tracks. It was 2019, and I was feeling very passionate. I wrote it in 10 minutes; it was super fast, like getting out my therapy session emotions. But I didn’t actually know how to end the song. I procrastinated till we got to the studio and then revealed to everyone that I didn’t have an ending. It reminds me of Vampire Weekend a little bit. And to fill you in on some Midwest history: There’s this place called the Wisconsin Dells, a chaotic water park land. It’s super corny, and they also love cheese. It’s just a really weird place. All of the resorts have really weird theme songs, and I feel like, listening back, we were like, ‘Oh my god, that sounds just like the Kalahari Resort’s theme song.’” **“Gone”** “The best time I write is if I’m feeling something pretty intense. It’s when, instead of journaling or calling my mom, I’m like, ‘All right, let’s try to get some lyrics out of this situation first.’ Other times, it’s just a bunch of notes on my phone that are all related. I just wanted it to sound aggressive, but also simple at the same time. It’s a straightforward punk song. I like that the chords have some dissonance to them. And the contents of the song are about being stuck in a situation and wanting out, not being sure what the right thing to do is.” **“Eventually”** “It’s about having panic attacks, but also finding love and how that can be so healing in those moments—to have loved ones. I think I wrote this right after having a panic attack, and I was like, ‘I don’t really know who to talk to about this, but I feel like I need to get this out of my system. I need to reflect on it somehow.’ There’s something bittersweet about it, this sad undertone.“ **“Fire Escape”** “‘I was excited about a trip that was coming up in a couple weeks with my boyfriend. We were long-distance, and I was so excited for this trip that I wrote a fantasy song about what it would be like. I did add some lyrics after the trip, too, capturing the entire event. I’ve always loved New York, and it’s funny because Chicago is, in a lot of ways, similar. It’s not the craziest transition when I’m there, but it still has such a magical mysticism to it. Things were getting a little bit better in my personal life, and I just wanted to write something happy.” **“Weeds”** “‘Weeds’ was one of the first songs I wrote for the album. It is one of my favorite songs on the record because it deviates from a lot of the breakup-angled songs I have. Those are super self-deprecating, and this was written from the perspective of being my own best friend. It’s me giving myself an intervention, almost. And musically, I think I took a lot of risks—experimenting and trying synths, stuff that isn’t as common on Beach Bunny things.” **“Gravity”** “A lot of this interlude was improvised. Sean was like, ‘Yeah, you want to do that? OK. We’re going to go get Starbucks or something. We’ll be back in a sec. You work on that.’ With the theme of the album being this salute to old sci-fi, in my head, it’s a movie-soundtrack moment.“ **“Scream”** “‘Scream’ was, by far, the hardest to write. The guitar was fleshed out, but it was very difficult to jam on. With my bandmates, if I bring them a song, we’ll do some trial and error. They just pick up on the vibe, and we know the direction of music. It usually works out pretty easily. But ‘Scream,’ for some reason, it felt like we were all very disjointed. It is so different from other Beach Bunny stuff; it was just difficult for everybody to figure out. Everyone saw that I was getting frustrated, so they left me alone with a bunch of synths, and I tried a bunch of stuff until it finally clicked. I don’t remember how long it took, but I remember after that day, everyone was exhausted and pissed but also happy that it was just done.” **“Infinity Room”** “There’s this UK artist. His name’s Tom Rosenthal. His songs make me cry all the time. They’re these really sweet, acoustic songs. He’s an amazing lyricist. And there was one song where he sampled bird sounds, and that blew my mind. I wrote it down long before I went to the studio. I was like, ‘I want to put birds on the record. I don’t know where, and I don’t know if that’s going to be weird, but I’m going to bring it up and see what people think.’ It ended up working really well. ‘Infinity Room’ reminds me of being in a greenhouse. It’s ambient nature vibes. The song’s lyrics, in themselves, are ethereal.” **“Karaoke”** “‘Karaoke’ was written early in the pandemic or right before the pandemic. I feel like that song is, in very simple terms, just about having a crush. It doesn’t have maybe that much depth to it, but it just has a lightheartedness about when you connect with someone cool. Sonically, it’s one of the more laidback songs on the record.” **“Love Song”** “As soon as this song was written, I was like, ‘OK, I want this album to have a happy ending.’ It really is just a sweet love song that I wanted to write with intention. It’s this big moment and that ties in all the themes. ‘Love Song’ feels like a reflection on all of the hard moments \[in a relationship\], but at the end, love perseveres and everything’s OK.”

Although Dry Cleaning began work on their second album before the London quartet had even released their 2021 debut, *New Long Leg*, there was little creative overlap between the two. “I definitely think of it as a different chapter,” drummer Nick Buxton tells Apple Music. “I think one of the nicest things was just knowing what we were in for a bit more,” adds singer Florence Shaw. “It was less about, ‘What are we doing?’ and more thinking about what we were playing.” Recorded in the same studio (Wales’ famous Rockfield Studios) with the same producer (PJ Harvey collaborator John Parish) as *New Long Leg*, *Stumpwork* sees Shaw, Buxton, bassist Lewis Maynard, and guitarist Tom Dowse hone the wiry post-punk and rhythmical bursts of their debut. The jangly guitar lines are melodically sharper and the grooves more locked in as Shaw’s observational, spoken-word vocals pull at the threads of life’s big topics, even when she’s singing about a missing tortoise. “When we finished *New Long Leg*, I always felt a bit like, ‘Ah, I’d like another chance at that.’ With this one, it definitely felt like, ‘Really happy with that,’” says Buxton. The quartet take us on a tour of *Stumpwork*, track by track. **“Anna Calls From the Arctic”** Nick Buxton: “It was a very late decision to start the album with this. I think it’s quite unusual because it’s very different from a lot of the other songs on the album.” Florence Shaw: “I quite liked that the album opened with a question: ‘Should I propose friendship?’ In the outro, we were thinking about the John Barry song ‘Capsule in Space,’ from *You Only Live Twice*. There’s quite a bit of that in the outro. At least, it was on the mood board.” **“Kwenchy Kups”** NB: “It’s named after those little plastic pots you get when you’re a kid—pots full of some luminous liquid, and you pierce the film on the lid with a straw.” FS: “We were at a studio in Easton in Bristol, and I wrote a lot of the lyrics on walks around the area. It’s a really nice little area, and there’s lots of interesting shops. We wanted to write a few more joyful songs, at least in tone, and the song is so cheerful-sounding. So, some of the lyrics came out of that, too, wanting to write something that was optimistic, the idea of watching animals or insects being just a simple, joyful thing to do.” **“Gary Ashby”** NB: “This is about a real tortoise.” FS: “On a walk in lockdown, I saw a ‘lost’ poster for ‘Gary Ashby.’ The rest of the story came out of imagining the circumstances of him disappearing and the idea that it’s obviously a family tortoise because he’s got this surname. It’s thinking about family and things getting lost in chaos, when things are a bit chaotic in the home and pets escape. We don’t know what happened to him. We don’t know if he’s alive or dead, which is a little bit disturbing, but hopefully we’ll find out one day.” **“Driver’s Story”** NB: “We were rehearsing at a little studio in the basement at our record label \[4AD\]. It was just me, Tom, and Lewis, and we weren’t there very long, but quite a few ideas for songs came out of that. The main bit of ‘Driver’s Story’ was one. It felt different to anything we’d done on *New Long Leg*. It’s just got such a nice, oozy feel to it. FS: “There’s a bit in the song about a jelly shoe and the idea of it being buried in your guts. A photographer called Maisie Cousins does photos of lots of bodily stuff and liquids, but with flowers and beautiful things as well. I was looking at a lot of those at the time. The jelly-shoe thing is about that—something pretty, plastic-y, mixed with guts.” Tom Dowse: “It’s got my dog barking on the end of it as well. He’s called Buckley. He is credited on the record.” **“Hot Penny Day”** TD: “I’d been listening to a lot of Rolling Stones, so this is an attempt at that. We were jamming it through, and it started to take on a bit more of a stoner-rock vibe. ‘Driver’s Story’ was also meant to be a bit more stoner-rock until John Parish got his hands in it and took the drugs out of it.” Lewis Maynard: “I found a bass wah pedal in my sister’s garage. I just plugged it in and started playing, and I was like, ‘This is fun.’ I’ve unfortunately not stopped playing bass wah.” NB: “It conjures up quite a lot of imagery. I was listening to some of Jonny Greenwood’s music for the film *Inherent Vice*, and it’s got a washed-out, desert-y feel. This sounds like Dry Cleaning in an alternate, parallel universe somewhere.” **“Stumpwork”** FS: “Quite a lot of the lyrics were gleaned from this archive of newspaper clippings that I went to in Woolwich Arsenal. It’s millions and millions of newspaper clippings on different subjects. There’s a bit \[in ‘Stumpwork’\] about toads crossing roads from this little article I found about a special tunnel being built, so that toads could traverse the street without being run over.” NB: “When we were trying to figure out a name for the record, it felt like the best option. We loved it, and it was really succinct. We liked that the word ‘work’ was in the title.” **“No Decent Shoes for Rain”** TD: “This was two of those jams from the basement of 4AD. We were quite unsure about this song. We took it to show John at the pre-production rehearsals, and he really liked it, and he didn’t really have anything to say about it, which is quite unusual. A lot of people ask, ‘Why did you record with John again?’ And it’s things like that—because he notices things that are good about you that you don’t notice. I was really self-conscious that the end section sounded too trad, classic rock. It sounded like the safest bit of guitar I’ve ever written. But once he said he was into it, I started to look at it from a different way, and it grew from that.” **“Don’t Press Me”** FS: “This has some recorder on it, which I had to play at half-time because it was really fast. I was like, ‘Oh, this would be nice if it had this little bit of a recorder on.’ I tried to play it, and I was completely incapable. I’d thought, ‘Oh, I’ll be able to do this. Kids play the recorder all the time. It’s easy.’ Even at half-time, I had to have loads of goes at it. So, it’s me playing the recorder, sped up, because I have no skills.” **“Conservative Hell”** NB: “I think this song’s really important because through the course of the record there’s two different types of song. There’s these upbeat, jangle, poppy ones and then there’s slightly slower, more groovy ones. This song has two very distinct elements that we’re really happy with. It’s nice as well to be so overtly political, which is not usually our scene.” FS: “The reason it ended up being such an on-the-nose phrase is I was thinking it would be really nice to write a song that was something like ‘Conservative Hell.’ And then, after a while, I was like, ‘That’s pretty good.’ I think it almost sounds like a silly headline, but accurate too.” **“Liberty Log”** FS: “The title comes from thinking about spring rolls. They’re like little logs, aren’t they? Then, later, I was thinking about a stupid monument, something that would be a really dumb statue in a town—just a big log and it’s called the Liberty Log.” LM: “This is one of the ones we took to the studio expecting it to be a shit-ton of editing, structuring, and that John would really fuck with it. We jammed it, and it just stayed the same. This one was first-take vibes, playing it in that way, expecting it to be changed.” **“Icebergs”** NB: “I think this is quite a bleak moment for us. Definitely the most icy-sounding track on the album. It feels like a really good end to the record to suddenly have this explosion of brass come in, and then it just peters out very slowly. I like that the album ends on quite an icy tone, even though that doesn’t necessarily represent us in how we feel about things. It’s a slightly more poignant ending rather than a nice, lovely outro.”

The bright, kaleidoscopic vignettes that defined Melody’s Echo Chamber’s first decade have softened into misty pastel watercolors on the French singer/songwriter Mélody Prochet’s third album, *Emotional Eternal*. Following 2018’s *Bon Voyage*—a dense, disorienting psych-pop set whose release was overshadowed by an accident that left Prochet hospitalized for several months—the artist moved from Paris to the Alps, became a mother, and fused all those experiences into a lighter, more lithe album that seeks peace somewhere between reverie and reality. Slipping between English and French, Prochet is a bewitching pied piper, her breathy incantations guiding a playful procession of sitar (“Pyramids in the Clouds”), horns (“A Slow Dawning of Peace”), and strings (“Personal Message”) through weightless, winding melodies that are held down by a persistent, propulsive bass. It all leads to “Alma\_the Voyage,” a swooning, swirling orchestral ode to the artist’s daughter that balances all the headiness with pure heart as Prochet gushes, “I’m so lucky to have you, and so proud to hold you.”

Like most people on this embattled earth, Maggie Rogers spent the better part of 2020 in isolation—in her case, in Maine, where *Surrender* took shape. “I started this record there,” she tells Apple Music. “And I was really drawn to big drums and distorted guitar, because I missed music that made me feel something physically. I missed the physicality of being at a festival”: a big feeling, she says—a little overwhelming, a little cold, a little drunk. The noise was a symbol of chaos, but also of liberation. “Like, in all the craziness in the world, being able to play with something like that,” she says, “it was as if it could make my body let go of the tension I was feeling.” So think of the album’s title as a possibility, or even a goal: that even at her most commanding—the electro-pop of “Shatter,” the country swagger of “Begging for Rain” and barroom folk of “I’ve Got a Friend”—Rogers can explore what it means to relinquish control without sacrificing the polish and muscle that makes her music pop. “When we’re cheek to cheek, I feel it in my teeth,” she sings on “Want Want”: an arthouse on paper, a blockbuster in sound. When Rogers started the album, she was so burned out from touring she could barely talk. “I hadn’t been to a grocery store in four years,” she says. “I was ready to bite. And this record is the bite. But when I listen back, there’s so much joy. I think that’s the thing that surprised me more than anything—that *that* was the place I escaped to, and it was the thing that became the way I survived it, or the way I worked through it. This idea of joy as a form of rebellion, as something that can be radical and contagious and connective and angry.” “Are you ready to start?” she sings on “Anywhere With You.” And then she repeats herself, a little louder each time.

Harriette Pilbeam played in low-key indie bands around Brisbane for years before debuting as Hatchie, but this project quickly vaulted her to international attention. Soon she was touring with Kylie Minogue and honing a vision of pop that looks back on dreamy ’90s alternative with fresh eyes. Pilbeam’s second album as Hatchie finds her sounding more polished and classic than ever before, with those gauzy layers of melody bolstered by more danceable rhythms. The sing-along choruses are more palpable than ever too, as heard on “This Enchanted” and “Quicksand,” the latter co-written with Olivia Rodrigo collaborator Dan Nigro. The aptly titled “The Rhythm” pushes especially close to the club, evoking warm flashbacks to Madonna. While Hatchie’s previous work slotted in neatly alongside shoegazing cult favorites, *Giving the World Away* might prove to be her anointment as a chart-friendly pop star.

Released on April 22nd. Giving the World Away tells a story of confidence found, as Hatchie unifies themes of trust, ambition, love and self-realization by embracing vulnerability as a strength. “It’s the concept of giving your heart away,” says Hatchie’s Harriette Pilbeam, “putting everything on the line...the entire album is really me realising that I actually need to do that in order to grow and accept myself.” Its story comes to life in the way it’s told: new songs are intentionally glossy and hi-fi, joyful and arena-sized in sound, articulating Pilbeam’s newfound strength and certainty. In fact, Giving the World Away is a record intentionally built for everyone’s empowerment, telling Pilbeam’s personal story while also inviting it in others to move from the personal to the public, taking the intimate and making it visible . “My last record I wanted people to sing along to,” she says. “This one was more about something you can move to. After kind of floating through young adulthood, I realised a lot of the things I'd been missing out on by under-appreciating myself. It's led me to making different decisions not only in regards to my music but also my personal life, the way I dress, the way I socialise, the way I treat my body etc.” Giving the World Away is about finally finding one’s footing, embracing visibility, and moving past fear of the future to welcome its bigger decisions and higher stakes.

Built to Spill’s mix of punk immediacy and classic-rock sprawl is one of indie’s defining sounds. Released 30 years into their career, *When the Wind Forgets Your Name* changes nothing. If anything, part of the Idaho band’s enduring appeal is leader and chief songwriter Doug Martsch’s ability to turn his rainy-day melancholy into something that feels not only sustainable but uplifting too. His inspirational songs are only gently so (“Alright”), and his epics unfold with a steadiness that makes them seem low-key no matter how loud they get (“Fool’s Gold,” “Comes a Day”). “I don’t wanna be constantly taking these long hard looks at myself,” Martsch sings on “Rocksteady.” “This psychology’s been inside of me/I don’t know how to be anybody else.”

Since its inception in 1992, Built to Spill founder Doug Martsch intended his beloved band to be a collaborative project, an ever-evolving group of incredible musicians making music and playing live together. “I wanted to switch the lineup for many reasons. Each time we finish a record I want the next one to sound totally different. It’s fun to play with people who bring in new styles and ideas,” says Martsch. “And it’s nice to be in a band with people who aren’t sick of me yet.” Following several albums and EPs on Pacific Northwest independent labels, including the unmistakably canonical indie rock classic, There’s Nothing Wrong With Love, released on Sub Pop offshoot Up Records in 1994, Martsch signed with Warner Brothers from 1995 to 2016. He and his rotating cast of cohorts recorded six more, inarguably great albums during that time – Perfect From Now On, Keep It Like a Secret, Ancient Melodies of the Future, You In Reverse, Untethered Moon, There Is No Enemy. There was also a live album, and a solo record, Now You Know. While the band’s impeccable recorded catalog is the entry point, Built to Spill live is an essential FORCE of its own: heavy, psychedelic, melodic and visceral tunes blaring from amps that sound as if they’re powered by Mack trucks. Now in 2022, Built to Spill returns with When the Wind Forgets Your Name, Martsch’s unbelievably great new album (and also his eighth full-length)... with a fresh new label. “I’m psyched: I’ve wanted to be on Sub Pop since I was a teenager. And I think I’m the first fifty year-old they’ve ever signed.” (The rumors are true, we love quinquagenarians…) When the Wind Forgets Your Name continues expanding the Built to Spill universe in new and exciting ways. In 2018 Martsch’s good fortune and keen intuition brought him together with Brazilian lo-fi punk artist and producer Le Almeida, and his long-time collaborator, João Casaes, both of the psychedelic jazz rock band, Oruã. On discovering their music Martsch fell in love with it right away. So when he needed a new backing band for shows in Brazil, he asked them to join. “We rehearsed at their studio in downtown Rio de Janeiro and I loved everything about it. They had old crappy gear. The walls were covered with xeroxed fliers. They smoked tons of weed,” Martsch says. The Brazil dates went so well Martsch, Almeida, and Casaes made the decision to continue playing together throughout 2019, touring the US and Europe. During soundchecks they learned new songs Martsch had written, and when the touring ended, they recorded the bass and drum tracks at his rehearsal space in Boise. After Almeida and Casaes flew home, Martsch began overdubbing guitars and vocals by himself. Martsch, Almeida, and Casaes had planned to mix the album together later in 2020 somewhere in Brazil or the US, but the pandemic kept them from reuniting in person. “We were able to send the tracks back and forth though, so we were still able to collaborate on the mixing process.” What emerged is When the Wind Forgets Your Name, a complex and cohesive blend of the artists’ distinct musical ideas. Alongside Built to Spill’s poetic lyrics and themes, the experimentation and attention to detail produces an album full of unique, vivid, and timeless sounds. The spare, power trio guitar riff in “Gonna Lose” is an anxiety-fueled joyride in song (“What could be more disorienting than being on acid in a dream?”). “Spiderweb” and “Never Alright” are classic-sounding, guitar-driven odes to REM and Dinosaur Jr (“No one can ever help no one not get their heart broken”). If there is such a thing as a Built to Spill sound, “Rocksteady” is maybe the band’s furthest departure from it yet with its reggae and dub-inspired instrumentation. The album also contains bittersweet songs like the lo-fi ‘60s-style anthem “Fool’s Gold,” with its mellotron strings, and bluesy, wailing guitars (“Fool’s gold made me rich for a little while”), and “Understood,” a song about misunderstanding, which also takes inspiration from Evel Knievel’s failed stunt in Martsch’s hometown when he was a child. (“The deaf hear, the blind see. Just different things than you and me.”) Martsch was also able to champion his love of comics by recruiting Alex Graham to illustrate the cover of When the Wind Forgets Your Name. “Alex published Dog Biscuits (Fantagraphics Books) online during the pandemic and it really spoke to me. I was thrilled when she agreed to paint the album cover.” What evolved was even better than he had imagined, with Graham also drawing a fifty panel comic strip for the gatefold. “I just asked for a painting and a comic. She created it all completely on her own.” Almeida and Casaes have returned to their duties in Oruã, and Martsch has begun playing with yet another Built to Spill lineup that features Prism Bitch’s Teresa Esguerra on drums and Blood Lemon’s Melanie Radford on bass. Built to Spill and Oruã are currently touring and have a string of shows planned together in September. Martsch concludes, “Making When the Wind Forgets Your Name was such a great experience. I had an incredible time traveling and recording with Almeida and Casaes. I also learned so much about Brazilian culture and music while creating it. My Portuguese was terrible when I first met Almeida and Casaes, but by the end of the year it was even worse.” (He also learned that when Billy Idol sings “Eyes Without a Face” it sounds like “Help the Fish'' in Portuguese.) It may have taken us 30 years of obvious fandom and courtship, but on September 9, 2022, Sub Pop Records is unabashedly proud to finally release an excellent new album from Built to Spill: When the Wind Forgets Your Name. Sometimes persistence pays off.

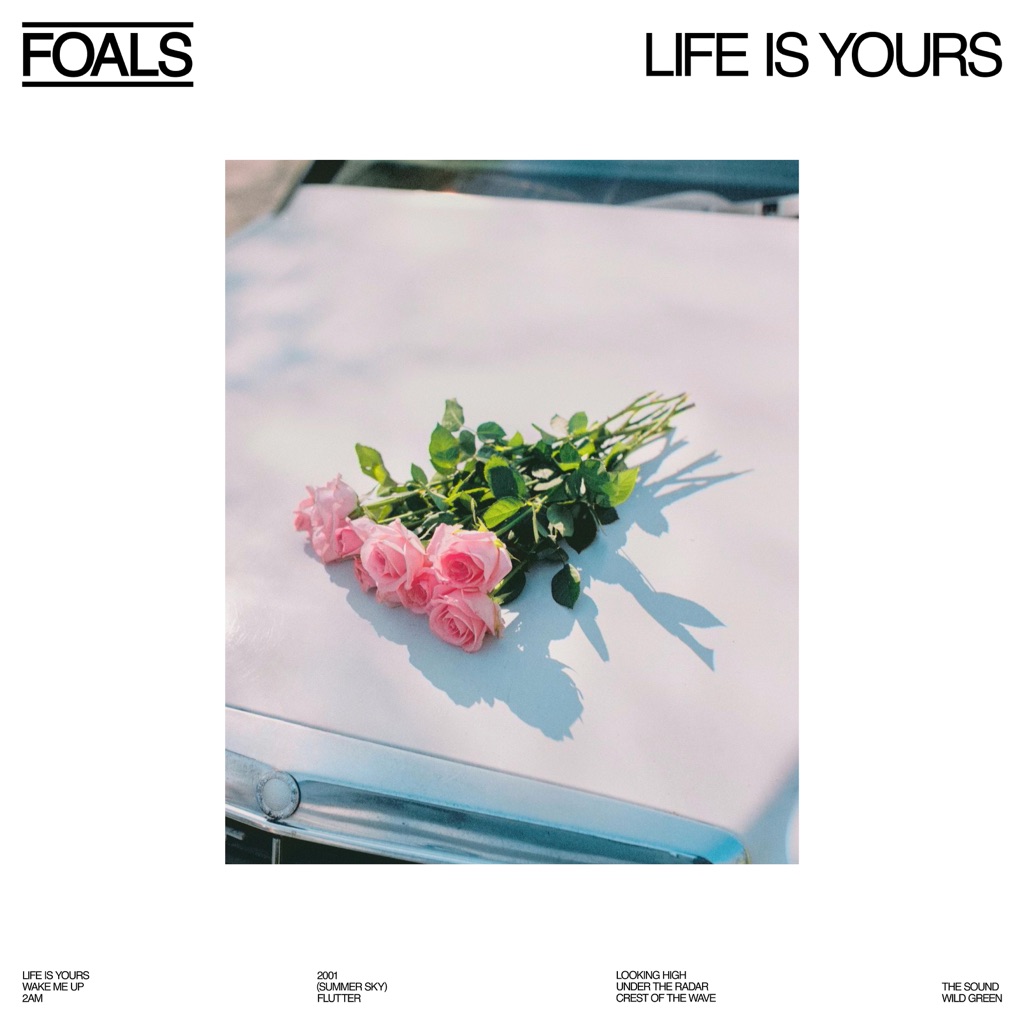

Yannis Philippakis doesn’t think that Foals will make another album like *Life Is Yours*. After the sprawling rock explorations of 2019’s two-part *Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost*, their seventh album is a product of the environment in which it was made: a series of grueling lockdowns, dreaming of lost nights and nocturnal roaming, yearning to be back out on the road. It was a period in which everyone was desperate to get out of the house, but only Foals could’ve turned it into the most buoyant and danceable record of their career. “I can’t see us making a record that’s as dancy and up and energized and simple as this again,” singer and guitarist Philippakis tells Apple Music. It’s not like the London-based trio ever seems inclined to repeat a trick anyway. “Everyone always says, ‘How come the sound changes so much from album to album?’” says guitarist and keyboardist Jimmy Smith. “Well, you go through three years, musically and emotionally, and you’re not the same person.” What marks Foals out as one of the most important guitar bands of their generation is how they always sound like themselves, wherever they take their sound: whether it’s the mix of melancholy and defiance in Philippakis’ voice; the wiry, sleek guitar lines; the swarming synths; or drummer Jack Bevan’s rhythmic propulsion. The anthemic grooves of *Life Is Yours* were made for dancing to, but delve deeper and you’ll find Philippakis in a contemplative mood. “It’s a positive and fun record made for communal moments, but the title is quite solemn advice,” he says. “It’s meant as an antidote to depression. On every record, there’s been a balancing act that goes on between the levels of melancholy.” Here, they get the blend just right. In many ways, *Life Is Yours* feels like a compilation of Foals’ best bits. Philippakis and Smith take us through it, track by track. **“Life Is Yours”** Yannis Philippakis: “Whatever is happening in the verse between the vocal and the keyboard part and the beat and the bassline felt like the DNA for the album, the blueprint. It was the bit I liked most. The song came right out of \[next track\] ‘Wake Me Up’—we were jamming it and then Jimmy went into that keyboard bit. The next day I said, ‘Let’s split it.’ Lyrically, the song is set along that coast between Seattle and Vancouver, where my partner is from, conversations that happen in private in car journeys along the Pacific Northwest.” **“Wake Me Up”** Jimmy Smith: “There’s always a bit of choice about which song to put out first, but this had the most immediate impact.” YP: “And it’s the most bombastic. We just felt that the message and the immediacy of the grooves and the boldness of the parts would be a wake-up call. It would demarcate the new era of the band and also be the kind of song that should come out after a pandemic. It felt like it was energizing and defiant, it wasn’t introspective. Normally we throw curveballs out first, we put something out that shocks people. I guess maybe it did in some way, but it also felt like it sets you up for what’s to come.” **“2am”** YP: “This started off more melancholic. I messed around with a keyboard during the depths of lockdown, late at night. I was missing the pub, missing the potential that a nightlife allows—the potential to make mistakes, the potential for wrong decisions, for wild decisions, for waking up in a very different place to the one you intended when you went out, the type of infinite choice that can occur if you do a night out well. It got moved into a bigger and poppier direction when we started recording with \[producer\] Dan Carey.” JS: “There was a smoky late-night version, which we were all down for. But as soon as we experienced the Dan Carey version, it made the smoky version seem unbelievably slow and dull.” **“2001”** YP: “This is one that really benefited from working on it with \[producer\] A. K. Paul. It’s almost a collaboration with A. K. Paul; he plays the bass on it and he wrote the chorus bass. It reminds me of The Rapture and ‘House of Jealous Lovers.’ Lyrically, I was thinking about the frustration that people were feeling in lockdown. It made me think about being a teenager and feeling frustrated when you are cooped up and you don’t have autonomy—and how the cure for that is to run away to the seaside and have a wild weekend. It’s partly looking back at when we moved to Brighton \[in 2001\], the excitement of leaving Oxford and us living in a house together for the first time. We moved there and it was a really exciting time for the band and an exciting time for the music scene.” **“(summer sky)”** YP: “This was essentially a jam with A. K. Paul. We’d wanted to work with him for a long time. We come from two different worlds, so it was a really fruitful collaboration.” JS: “Pretty much everything he did was amazing. He had to edit out a lot of his own stuff, but it was pretty special. We just sat on a sofa, watching it happen, watching this man use his amazing brain to make the song better.” **“Flutter”** YP: “I was looping something on the guitar and the vocal part came very quickly. We were playing it over and over, and Jack sat back on a beat, and the riff came out of that same jam. Everything was there in the first few hours, basically. We didn’t work on it more as we wanted it to be simple, like, ‘Let this be a slice of the moment.’” **“Looking High”** JS: “This is one of the ones that I started. It was an experiment of very, very simple guitar playing and pop structuring, that two-chord pattern back and forth, and I had a drum machine playing a Wu-Tang beat which I copied from ‘Protect Ya Neck.’ It all slotted in really quickly, and then Yannis added the other parts of the song, the more reflective, dancier bits in the drop-downs. When I listen, it feels like that moment at a show when you lose yourself a little bit and then it snaps back into the verse and it’s completely different. I really like the to-ing and fro-ing; there’s a cleanliness to it.” **“Under the Radar”** JS: “It came straight out of the practice room when we were writing. There’s a few on the record that were written on the spot, like nothing brought in from the past.” YP: “Probably 30 percent of our songs come from jams, but we always jam our ideas. No one ever comes in with a complete song, as in, ‘That’s it, learn the song.’ We tried to keep this really simple. It felt quite different for us. I think it feels New Wave-y, like something we haven’t written before.” **“Crest of the Wave”** YP: “This goes back to a recording session we did in about 2012, with Jono Ma from Jagwar Ma. It was this syrupy, sweaty jam known as ‘Isaac,’ and we parked it because I couldn’t find the vocals, but this time I did. Something happened between the bassline changing and the vocals, and we just cracked it. To me, it feels like a companion to \[2010 single\] ‘Miami’ because it’s set in Saint Lucia. It’s got longing and a bittersweet feeling of rejection in it; it’s somewhere idyllic, but you’re melancholic. There’s high humidity and there’s tears.” **“The Sound”** YP: “We don’t normally do that uplifting, classic penultimate track. This is us at our most electronic and clubby. It’s inspired by Caribou, that slightly dusty and dirty vibe; there’s crackle and a slight wildness to it. I like the fact that there’s a slightly West African-style guitar part that contrasts with the clubbiness of the synths. I had a lot of fun with the vocals on that. I wanted to layer up lots of shards of lyrics and approach it in a slightly Karl Hyde-ian way.” **“Wild Green”** JS: “The album finishes in such an organic way, it almost falls apart. I love how it just drops straight into the studio ambience. It seemed to happen quite naturally.” YP: “It’s about life cycles, the cycle of spring, expectation of spring and regeneration. In the first half of the song, there’s lyrics about wanting to fold oneself in the corner of the day and wait for the spring to reemerge. Then there’s a shift. Once you get to the second half of the song, spring is passed and now it’s actually the wind-down and it’s departure and it’s death. It’s not in a dark way, but it’s passing through states. It’s about the passing of time. That’s why it felt like a good album closer, because it’s basically saying, in a veiled way, farewell to the listener.”

“Every time I go in, I\'m trying to do something I haven\'t done before,” Jack White tells Apple Music. “And it\'s not like something that *other* people have never done before. It’s whatever it is to get me to a different zone so I\'m not repeating myself.” On *Fear of the Dawn*—the first of two solo LPs White is releasing in 2022, and the first in over four years—that zone is the world of digital studio effects, new territory for an artist who’s long been an avatar and champion for all matters analog. Here, working in lockdown and playing most of the instruments himself as a result, White’s challenged himself to make a rock record that’s every bit as immediate and textured as what he’s made before. The guitars are scrambled and fried, blown out and buffed to an often blinding shine (see: the crispy title track; “The White Raven”). Keys squiggle and giggle (“Morning, Noon and Night”), drums stutter and skitter and hiccup (“That Was Then, This is Now,” “What’s the Trick?”). It’s a real studio record, saturated and collage-like—White flexing his muscles as a producer. “I don\'t know how many, but there\'s dozens and dozens of tracks,” he says of the recording process. “I never used to do that. I made mistakes—I would play drums last, which you\'re not supposed to do. But then I started to feed off of that. I liked that it was wrong. It\'s nice that time goes on and you get better at certain things in the studio.” And having been so dogmatic from the start—famously dedicated to tape, vinyl, and primary colors—White sounds free to experiment on *Fear of the Dawn*, whether he’s dusting off a Cab Calloway sample and joining forces with Q-Tip for “Hi-De-Ho” or pasting together shards of radioactive guitar and mutating vocals on “Into the Twilight.” But that doesn’t mean he’s any less disciplined. “It\'s delicate—when you have eight tracks only, there\'s not much you can do,” he says. “If someone says you can have as many tracks as you want, now you got to be your own boss. You got to be hard on yourself. All the years of the razor blade editing gets you to a point where I don\'t want to waste my energy on that when I could put that energy to this now.”

Recorded by King Gizz in Bangkok, Shanghai and Melbourne in 2019 and 2020 Mixed by Stu Mackenzie and Joey Walker Produced by Stu Mackenzie Mastering by Joe Carra Cover design by Jason Galea

On his third solo album, Fred Gibson (better known as Fred again..) returns with his fingers firmly on the pulse of everything around him. Rounding out a deeply personal trilogy, *Actual Life 3* sees the London-based producer, DJ, and singer-songwriter once more thrive on the challenges of sound reinvention and renewal. “I think the feeling that I’ve become really obsessed with is taking very fleeting moments and exposing as much beauty as is in them,” he tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “You know how sometimes if you see something in normal timing, and then you see it in slow-mo, like, ‘Oh wow. There\'s a whole new emotional framing for this.’” Fred first envisioned this unique narrative in 2020 for his debut, *Actual Life*, released over lockdown as a remedy to the melancholic uncertainty of the time. Delivering three distinct chapters across 2021, the BRIT Award-winning producer (and longtime mentee of Brian Eno) dives deeper in his cache of bright snippets and samples from everyday scenes, fusing soul, R&B, and bass house elements for jaw-droppingly euphoric and intimate tracks. “Sometimes I’m conscious of it and sometimes I’m not,” he says. “But one thing I know is that when I’m there, I make loads of ideas.” Much of this LP was made on the move, via long airport stops, tube journeys, or lunchtime breaks. And, like its predecessors, this collection is predominantly influenced by this process, with tracks labeled after the people he’s worked with, or the inspirations behind them. Here, Gibson draws euphoria from fleeting emotions, filtering vocals from names including London rapper and singer BERWYN, Toronto poet Mustafa Ahmed, and G.O.O.D Music’s 070 Shake across woozy synths and deep, intrepid basslines. But *Actual Life 3* also differs in its greater worldly experience. As is the case with hits he’s penned for the likes of Ed Sheeran, BTS, George Ezra, and Stormzy, tracks including “Delilah (pull me out of this)” (sampling Delilah Montagu’s 2021 single “Lost Keys”) and “Bleu (better with time)” (slicing verses from Yung Bleu’s 2020 track “You’re Mines Still”) arrive with the boost of rapturous unveilings at Gibson’s online DJ sets and gig slots. Although getting the music to people’s ears on these occasions offered an ideal proving ground for his blossoming tracks, it was moments of solitude that gave him the most to work with. “When you\'re on your own,” he explains, “you can just be in the world—any place that gives you a conveyor belt of humanity, buzzing away in the background, often when there\'s a bubbling undercurrent of slight excitement, I think that’s just the ultimate gift.”

The way *Florist* comes on is so quiet and unassuming, you might wonder if the band is actually playing music. That is, of course, until it’s obvious that they are, and that the rain and breeze and crickets that so unassumingly complement their songs aren’t just accessories but foundational: This is music about rivers that wants to make you pay more attention to rivers. Some songs stand out—“Red Bird Pt. 2,” “Sci - Fi Silence,” “Spring in Hours,” “Organ’s Drone”—but they’re best absorbed in the same casual, front-porch mode in which it sounds like the music was made, and through which vocalist Emily Sprague’s naive wisdom transmits.

19 tracks that culminate the decade-long journey of friendship and collaboration

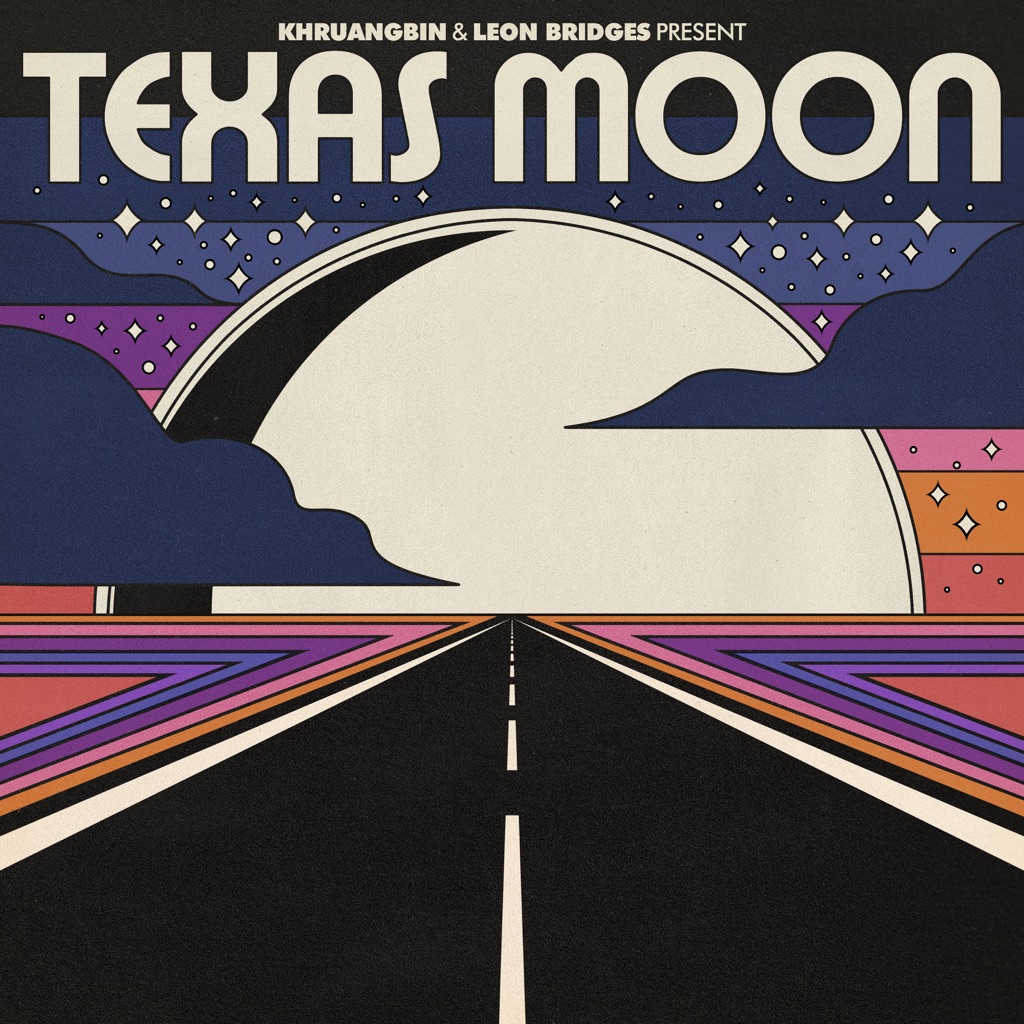

Texas connection aside (Bridges is from Fort Worth, Khruangbin from Houston), Leon Bridges and Khruangbin make a natural pair: Bridges, the throwback soul man who brings R&B’s past into vivid focus, and Khruangbin, a one-band jukebox whose encyclopedic sense of groove has made them one of the more sneakily pleasurable artists of the 2010s. A companion to 2020 collaboration *Texas Sun*, *Texas Moon* is, first and foremost, a mood: dusky, mellow, warm, windows down. The artists can take on Philly soul with a psychedelic slant (“Doris”), mix disco with West African juju (“B-Side”), and play country cadences with ambient, indie-rock warmth (“Mariella”), all with an effortlessness that would make their melting pot state proud.

Two of the acts boldly leading Texas music into the future have now delivered a second chapter of their groundbreaking collaboration, further extending the region’s sonic possibilities. Singer/songwriter Leon Bridges, from Ft. Worth, and trailblazing Houston trio Khruangbin have joined forces for the Texas Moon EP, a follow-up to 2020’s acclaimed Texas Sun project. While the five new songs are clearly a continuation of the first EP, they also have an identity all their own—Bridges calls it “more introspective,” while Khruangbin bassist Laura Lee says it “feels more night time.” When Texas Sun was released, AllMusic called the results “intoxicating” and Paste noted that “their talents and character go together so well.” Now comes the next stage—a set of songs that touch on themes like love, faith, and death while exploring new dimensions of inventive, hypnotic grooves. Significantly, both parties’ musical directions were clearly affected by their time working together. Khruangbin’s most recent album, Mordechai, moved their own vocals much further forward, a change they readily admit was a direct result of working with Bridges. Meanwhile, since these recordings began, in addition to his genre-defying album Gold-Digger’s Sound, Bridges has put out several other challenging, shared tracks, including work with John Mayer, Lucky Daye, and Jazmine Sullivan. Texas Moon represents a genuine and rare achievement, with two of the most respected and innovative acts of their generation truly collaborating to create something new. “As far as an essentially instrumental band, these guys are kind of the top for me,” says Bridges. “I’m honored to have been the first singer that they’ve incorporated in their music.” “It feels really special to me,” says Lee. “It’s not Khruangbin, it’s not Leon, it’s this world we created together.”

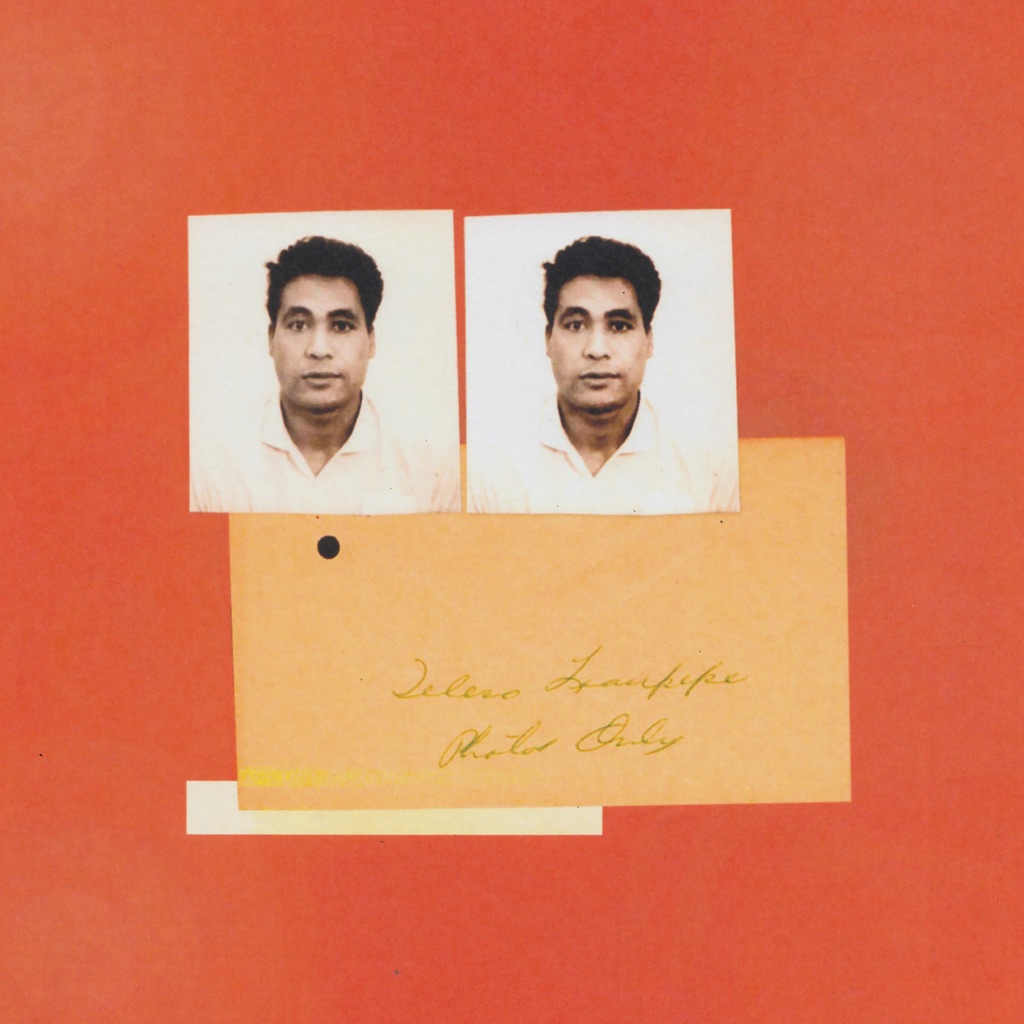

Gang of Youths frontman David Le’aupepe’s life was turned upside down in 2018 when his beloved father, Tattersall, passed away. Dealing with his dad’s loss was one thing—uncovering the secrets that came to light in the wake of his passing was another. His father was born in Samoa in 1938, not New Zealand in 1948, as Le’aupepe had believed. Tattersall also had two sons in New Zealand before faking his death and moving to Australia—half-brothers that Le’aupepe was, until his father’s passing, unaware he had. “\[These\] were things that my dad hid or made sure that we didn’t find out about because, I think, there was a lot of guilt and sadness and scandal around his life before he came to Australia,” Le’aupepe tells Apple Music’s Matt Wilkinson. The singer wasn’t, however, angry when these revelations came to light. “My dad was amazing, but he was a complicated man,” says Le’aupepe. “He was my hero. And naturally, when you find out more about your hero, you get excited. Also, I wanted big brothers growing up, and I just supplemented them with the band and people from church and stuff like that. So, I was actually able to claim a part of myself, a part of my heritage, a part of all this stuff, while also simultaneously reconnecting with these two blokes who I just loved instantly. It was a really, really cool thing.” Tattersall’s passing is a lyrical theme that binds Gang of Youths’ third album together (“I prayed the day you passed/But the heavens didn’t listen,” begins Le’aupepe on opener “you in everything”), but the events of his life and death are captured most concisely in the sparse, poetic piano ballad “brothers.” “There’s a sense of the storytelling traditions of old,” says Le’aupepe of the song. “I listen to a lot of Paul Kelly, Archie Roach—the greatest songwriters who wrote and told stories. Joni Mitchell’s ‘Cactus Tree’ is another one. I love a cinematic slow reveal of what the story’s about. And obviously, cinema’s played a huge role in influencing where this album’s gone visually and sonically.” So, too, has the singer’s Polynesian heritage. While songs such as “the angel of 8th ave.” and “the man himself” merge the band’s penchant for big-tent indie rock with a distinct hint of Britpop (“spirit boy”), and “the kingdom is within you” flirts with UK garage, the album is rich with a mélange of Polynesian musical influences. Witness the presence of Cook Islands drum group the Nuanua Drummers and the Auckland Gospel Choir on “in the wake of your leave,” or the spoken-word verse in “spirit boy,” delivered in the Māori language te reo. “the man himself,” meanwhile, features samples of Pacific Island hymns, captured by British composer David Fanshawe. “There was a sense of wanting to make the record feel like it wasn’t just us mining my people’s past or our people’s collective past for inspiration,” says Le’aupepe, “but that we were in a mode of wanting to move forward and \[take\] what’s happening now in terms of a creative direction.” That the London-based, Sydney-born band managed to largely self-produce (with occasional coproduction from Peter Katis and Peter Hutchings) such an expansive album in their rehearsal room in the East London suburb of Hackney is nothing short of remarkable. “It felt like this anarchic confluence of values,” says Le’aupepe. “It was really, really interesting seeing how together we are, and working in that close, confined space has given us a unity of opinion, or a unity of ‘this is where we’re going to go with it.’ And I think that was all cultivated in the sessions for *angel in realtime.*”

Gang of Youths David Le'aupepe – lead vocals, production, engineering (all tracks); guitar (1, 2, 5, 6); backing vocals, piano (2, 6); bass (3), keyboards (3, 5, 6), synthesizer (6) Donnie Borzestowski – drums, production, engineering (all tracks); percussion (1, 5, 6), piano (1), backing vocals (2, 4, 6–13) Max Dunn – production, engineering (all tracks); bass (1, 2, 4–13), banjo (1, 5), piano (1, 6), backing vocals (2), guitar (3); autoharp, keyboards (5), Tom Hobden – production, engineering (all tracks); backing vocals (2, 5), viola (2, 4–6, 11), violin (2–6, 11), piano (4, 7, 9–13) Jung Kim – guitar, production, engineering (all tracks);, backing vocals (2), piano (3, 8) Additional musicians Daniel Ricciardo – backing vocals (2, 11) Auckland Gospel Choir – backing vocals (2, 11) Seumanu Simon Matāfai – music direction (2), piano (6) Anuanua Drummers – percussion (2, 6) Ian Burdge – cello (5, 11) Johnny Griffiths – clarinet, flute, saxophone (5) Ilid Jones – cor anglais, oboe (5) Nick Etwell – flugelhorn, trumpet (5, 11) Matt Gunner – French horn (5, 11) Dave Williamson – trombone (5, 11) Indiana Dunn – backing vocals, percussion (6) James Larter – marimba (6) Kaumātua – spoken voice (6) Tony Gibbs – spoken voice (6) Aemon Beech - percussion (1) Anna Pamin – percussion (11) Blake Friend – percussion (11) Peter Hutchings – synthesizer (11) Technical Peter Hutchings – production (2, 11), engineering (2, 3, 6, 11), mixing (11) Peter Katis – production (2), mixing (5) Count – mastering (1, 2, 5, 6), mixing (1, 2, 6) Joe LaPorta – mastering (3) Craig Silvey – mixing (3, 11) Richard Woodcraft – engineering (1, 5, 6, 11) Gergő Láposi – orchestral engineering (1) Péter Barabás – orchestral engineering (1) Dani Bennett Spragg – mixing assistance (11) Emily Wheatcroft Snape – engineering assistance (2, 11) Jamie Sprosen – engineering assistance (2, 11) Luke O'Dea – engineering assistance (3) Tess Dunn – engineering assistance (6)

When COVID-19 lockdowns prohibited Welsh Dadaist Cate Le Bon to fly back to the United States from Iceland, she found herself returning to her homeland to create a sixth studio album, *Pompeii*, a collection of avant-garde art pop far removed from the 2000s jangly guitar indie she once hung her hat on. In Cardiff, recording in a house “on a street full of seagulls,” as she tells Apple Music, “I instinctively knew where all the light switches were and I knew all these sounds that the house makes when it breathes in the night.” Created with co-producer Samur Khouja, the album obscures linear nostalgia to confront uncertainty and modern reality, with stacked horns, saxophones, and synths. “For a while I was flitting between despair and optimism,” she says. “I realized that those are two things that don\'t really have or prompt action. So I tried to lean into hope and curiosity instead of that. Then I kept thinking about the idea that we are all forever connected to everything. That’s probably the theme that ties together the record.” Below, Cate Le Bon breaks down *Pompeii*, track by track. **“Dirt on the Bed”** “This song is very set in the house. It\'s being haunted by yourself in a way—this idea of time travel and storing things inside of you that maybe don\'t serve you but you still have these memories inside of you that you\'re unconscious of. It was the first song that we started working on when Samur arrived in Wales. It’s pretty linear, but it blossoms in a way that becomes more frantic, which was in tune with the lockdown in a literal and metaphorical sense.” **“Moderation”** “I was reading an essay by an architect called Lina Bo Bardi. She wrote an essay in 1958 called ‘The Moon’ and it\'s about the demise of mankind, this chasm that\'s opened up between technical and scientific progress and the human capacity to think. All these incremental decisions that man has made that have led to climate disaster and people trying to get to the moon, but completely disregarding that we\'ve got a housing crisis, and all these things that don\'t really make sense. We\'ve lost the ability to account for what matters, and it will ultimately be the demise of man. We know all this, and yet we still crave the things that are feeding into this.” **“French Boys”** “This song definitely started on the bass guitar, of wanting this late-night, smoky, neon escapism. It’s a song about lusting after something that turns into a cliché. It’s this idea of trying to search for something to identify yourself \[with\] and becoming encumbered with something. I really love the saxophone on this one in the instrumental. It is a really beautiful moment between the guitars and the saxophones.” **“Pompeii”** “This is about putting your pain somewhere else, finding a vessel for your pain, removing yourself from the horrors of something, and using it more as a vessel for your own purposes. It’s about sending your pain to Pompeii and putting your pain in a stone.” **“Harbour”** “I made a demo with \[Warpaint’s\] Stella Mozgawa, who plays drums on the record. We spent a month together at her place in Joshua Tree, just jamming out some demos I had, and this was one of them that became a lot more realized. The effortless groove that woman puts behind everything, it\'s just insane to me. She was encouraging me to put down a bassline. That playfulness of the bass is probably a direct product of her infectiousness, but the song is really about \'What do you do in your final moment? What is your final gesture? Where do you run when you know there\'s no point running?\'” **“Running Away”** “‘Running Away’ was another song that I worked on with Stella in Joshua Tree. It\'s about disaffection, I suppose, and trying to figure out whether it\'s a product of aging, where you know how to stop yourself from getting hurt by switching something off, and whether that\'s a useful tool or not. It’s an exploration of knowing where the pitfalls of hurt are, because you have a bit more experience. Is it a useful thing to avoid them or not?” **“Cry Me Old Trouble”** “Searching for your touch songs of faith, when you tap into this idea that you\'re forever connected to anything, there\'s a danger—the guilt that is imposed on people through religion, this idea of being born a sinner. Of separating those two things of feeling like you are forever connected to everything without that self-sacrifice or martyrdom. It’s about being connected to old trouble and leaning into that, and this connection to everything that has come before us. We are all just inheriting the trouble from generations before.” **“Remembering Me”** “It’s really about haunting yourself. When the future\'s dark and you don\'t really know what\'s going to happen, people start thinking about their legacy and their identity, and all those things that become very challenged when everything is taken away from you and all the familiar things that make you feel like yourself are completely removed. \[During the pandemic\] a lot of people had the internet to express themselves and forge an identity, to make them feel validated.” **“Wheel”** “In one sense, it is very much about the time trials of loving someone, and how that can feel like the same loop over and over, but I think the language is a little bit different. It\'s a little more direct than the rest of the record. I was struggling to call people over the pandemic. What do you say? So, I would write to people in a diary, not with any idea that I would send it to them, but just to try and keep this sense of contact in my head. A lot of this was pulled from letters that I would write my friend. Instead of \'Dear Diary\' it was \'Dear Bradford,\' just because I missed him, but couldn\'t pick up the phone.”

Pompeii, Cate Le Bon’s sixth full-length studio album and the follow up to 2019’s Mercury-nominated Reward, bears a storied title summoning apocalypse, but the metaphor eclipses any “dissection of immediacy,” says Le Bon. Not to downplay her nod to disorientation induced by double catastrophe — global pandemic plus climate emergency’s colliding eco-traumas resonate all too eerily. “What would be your last gesture?” she asks. But just as Vesuvius remains active, Pompeii reaches past the current crises to tap into what Le Bon calls “an economy of time warp” where life roils, bubbles, wrinkles, melts, hardens, and reconfigures unpredictably, like lava—or sound, rather. Like she says in the opener, “Dirt on the Bed,” Sound doesn’t go away / In habitual silence / It reinvents the surface / Of everything you touch. Pompeii is sonically minimal in parts, and its lyrics jog between self-reflection and direct address. Vulnerability, although “obscured,” challenges Le Bon’s tendencies towards irony. Written primarily on bass and composed entirely alone in an “uninterrupted vacuum,” Le Bon plays every instrument (except drums and saxophones) and recorded the album largely by herself with long-term collaborator and co-producer Samur Khouja in Cardiff, Wales. Enforced time and space pushed boundaries, leading to an even more extreme version of Le Bon's studio process – as exits were sealed, she granted herself “permission to annihilate identity.” “Assumptions were destroyed, and nothing was rejected” as her punk assessments of existence emerged. Enter Le Bon’s signature aesthetic paradox: songs built for Now miraculously germinate from her interests in antiquity, philosophy, architecture, and divinity’s modalities. Unhinged opulence rests in sonic deconstruction that finds coherence in pop structures, and her narrativity favors slippage away from meaning. In “Remembering Me,” she sings: In the classical rewrite / I wore the heat like / A hundred birthday cakes / Under one sun. Reconstituted meltdowns, eloquently expressed. This mirrors what she says about the creative process: “as a changeable element, it’s sometimes the only point of control… a circuit breaker.” She’s for sure enlightened, or at least more highly evolved than the rest of us. Hear the last stanza on the album closer, “Wheel”: I do not think that you love yourself / I’d take you back to school / And teach you right / How to want a life / But, it takes more time than you’d tender. Reprimanding herself or a loved one, no matter: it’s an end note about learning how to love, which takes a lifetime and is more urgent than ever. To leverage visionary control, Le Bon invented twisted types of discipline into her absurdist decision making. Primary goals in this project were to mimic the “religious” sensibility in one of Tim Presley’s paintings, which hung on the studio wall as a meditative image and was reproduced as a portrait of Le Bon for Pompeii’s cover. Fist across the heart, stalwart and saintly: how to make “music that sounds like a painting?” Cate asked herself. Enter piles of Pompeii’s signature synths made on favourites such as the Yamaha DX7, amongst others; basslines inspired by 1980s Japanese city pop, designed to bring joyfulness and abandonment; vocal arrangements that add memorable depth to the melodic fabric of each song; long-term collaborator Stella Mozgawa’s “jazz-thinking” percussion patched in from quarantined Australia; and Khouja’s encouraging presence. The songs of Pompeii feel suspended in time, both of the moment and instant but reactionary and Dada-esque in their insistence to be playful, satirical, and surreal. From the spirited, strutting bass fretwork of “Moderation”, to the sax-swagger of “Running Away”; a tale exquisite in nature but ultimately doomed (The fountain that empties the world / Too beautiful to hold), escapism lives as a foil to the outside world. Pompeii’s audacious tribute to memory, compassion, and mortal salience is here to stay.

*Read a personal, detailed guide to Björk’s 10th LP—written by Björk herself.* *Fossora* is an album I recorded in Iceland. I was unusually here for a long time during the pandemic and really enjoyed it, probably the longest I’d been here since I was 16. I really enjoyed shooting down roots and really getting closer with friends and family and loved ones, forming some close connections with my closest network of people. I guess it was in some ways a reaction to the album before, *Utopia*, which I called a “sci-fi island in the clouds” album—basically because it was sort of out of air with all the flutes and sort of fantasy-themed subject matters. It was very much also about the ideal and what you would like your world to be, whereas *Fossora* is sort of what it is, so it’s more like landing into reality, the day-to-day, and therefore a lot of grounding and earth connection. And that’s why I ended up calling *Fossora* “the mushroom album.” It is in a way a visual shortcut to that, it’s all six bass clarinets and a lot of deep sort of murky, bottom-end sound world, and this is the shortcut I used with my engineers, mixing engineers and musicians to describe that—not sitting in the clouds but it’s a nest on the ground. “Fossora” is a word that I made up from Latin, the female of *fossor*, which basically means the digger, the one who digs into the ground. The word fossil comes from this, and it’s kind of again, you know, just to exaggerate this feeling of digging oneself into the ground, both in the cozy way with friends and loved ones, but also saying goodbye to ancestors and funerals and that kind of sort of digging. It is both happy digging and also the sort of morbid, severe digging that unfortunately all of us have to do to say goodbye to parents in our lifetimes. **“Atopos” (feat. Kasimyn)** “Atopos” is the first single because it is almost like the passport or the ID card (of the album), it has six bass clarinets and a very fast gabba beat. I spent a lot of time on the clarinet arrangements, and I really wanted this kind of feeling of being inside the soil—very busy, happy, a lot of mushrooms growing really fast like a mycelium orchestra. **“Sorrowful Soil” and “Ancestress” (feat. Sindri Eldon)** Two songs about my mother. “Sorrowful Soil” was written just before she passed away, it\'s probably capturing more the sadness when you discover that maybe the last chapter of someone\'s life has started. I wanted to capture this emotion with what I think is the best choir in Iceland, The Hamrahlid Choir. I arranged for nine voices, which is a lot—usually choirs are four voices like soprano, alto, or bass. It took them like a whole summer to rehearse this, so I\'m really proud of this achievement to capture this beautiful recording. “Ancestress” deals with after my mother passing away, and it\'s more about the celebration of her life or like a funeral song. It is in chronological order, the verses sort of start with my childhood and sort of follow through her life until the end of it, and it\'s kind of me learning how to say goodbye to her. **“Fungal City” (feat. serpentwithfeet)** When I was arranging for the six bass clarinets I wanted to capture on the album all different flavors. “Atopos” is the most kind of aggressive fast, “Victimhood” is where it’s most melancholic and sort of Nordic jazz, I guess. And then “Fungal City” is maybe where it\'s most sort of happy and celebrational. I even decided to also record a string orchestra to back up with this kind of happy celebration and feeling and then ended up asking serpentwithfeet to sing with me the vocals on this song. It is sort of about the capacity to love and this, again, meditation on our capacity to love. **“Mycelia”** “Mycelia” is a good example of how I started writing music for this album. I would sample my own voice making several sounds, several octaves. I really wanted to break out of the normal sort of chord structures that I get stuck in, and this was like the first song, like a celebration, to break out of that. I was sitting in the beautiful mountain area in Iceland overlooking a lake in the summer. It was a beautiful day and I think it captured this kind of high energy, high optimism you get in Iceland’s highlands. **“Ovule”** “Ovule” is almost like the feminine twin to “Atopos.” Lyrically it\'s sort of about being ready for love and removing all luggage and becoming really fresh—almost like a philosophical anthem to collect all your brain cells and heart cells and soul cells in one point and really like a meditation about love. It imagines three glass eggs, one with ideal love, one with the shadows of love, and one with day-to-day mundane love, and this song is sort of about these three worlds finding equilibrium between these three glass eggs, getting them to coexist.