Gaffa (Sweden)'s Best Albums of 2019

GAFFA.se – allt om musik

Published: February 22, 2022 20:31

Source

Look past its futurist textures and careful obfuscations, and there’s something deeply human about FKA twigs’ 21st-century R&B. On her second full-length, the 31-year-old British singer-songwriter connects our current climate to that of Mary Magdalene, a healer whose close personal relationship with Christ brought her scorn from those who would ultimately write her story: men. “I\'m of a generation that was brought up without options in love,” she tells Apple Music. “I was told that as a woman, I should be looked after. It\'s not whether I choose somebody, but whether somebody chooses me.” Written and produced by twigs, with major contributions from Nicolas Jaar, *MAGDALENE* is a feminist meditation on the ways in which we relate to one another and ourselves—emotionally, sexually, universally—set to sounds that are at once modern and ancient. “Now it’s like, ‘Can you stand up in my holy terrain?’” she says, referencing the titular lyric from her mid-album collaboration with Future. “‘How are we going to be equals in this? Spiritually, am I growing? Do you make me want to be a better person?’ I’m definitely still figuring it out.” Here, she walks us through the album track by track. **thousand eyes** “All the songs I write are autobiographical. Anyone that\'s been in a relationship for a long time, you\'re meshed together. But unmeshing is painful, because you have the same friends or your families know each other. No matter who you are, the idea of leaving is not only a heart trauma, but it\'s also a social trauma, because all of a sudden, you don\'t all go to that pub that you went to together. The line \[\'If I walk out the door/A thousand eyes\'\] is a reference to that. At the time, I was listening to a lot of Gregorian music. I’d started really getting into medieval chords before that, and I\'d found some musicians that play medieval music and done a couple sessions with them. Even on \[2014\'s\] *LP1*, I had ‘Closer,’ which is essentially a hymn. I spent a lot of time in choir as a child and I went to Sunday school, so it’s part of who I am at this stage.” **home with you** “I find things like that interesting in the studio, just to play around and bring together two completely different genres—like Elton John chords and a hip-hop riff. That’s what ‘home with you’ was for me: It’s a ballad and it\'s sad, but then it\'s a bop as well, even though it doesn\'t quite ever give you what you need. It’s about feeling pulled in all directions: as a daughter, or as a friend, or as a girlfriend, or as a lover. Everyone wanting a piece of you, but not expressing it properly, so you feel like you\'re not meeting the mark.” **sad day** “It’s like, ‘Will you take another chance with me? Can we escape the mundane? Can we escape the cyclical motion of life and be in love together and try something that\'s dangerous and exhilarating? Yeah, I know I’ve made you sad before, but will you give me another chance?\' I wrote this song with benny blanco and Koreless. I love to set myself challenges, and it was really exciting to me, the challenge of retaining my sound while working with a really broad group of people. I was lucky working with Benny, in the fact that he creates an environment where, as an artist, you feel really comfortable to be yourself. To me, that\'s almost the old-school definition of a producer: They don\'t have to be all up in your grill, telling you what to do. They just need to lay a really beautiful, fertile soil, so that you can grow to be the best you in the moment.” **holy terrain** “I’m saying that I want to find a man that can stand up next to me, in all of my brilliance, and not feel intimidated. To me, Future’s saying, ‘Hey, I fucked up. I filled you with poison. I’ve done things to make you jealous. Can you heal me? Can you tell me how to be a better man? I need the guidance, of a woman, to show me how to do that.’ I don\'t think that there are many rappers that can go there, and just put their cards on the table like that. I didn\'t know 100%, once I met Future, that it would be right. But we spoke on the phone and I played him the album and I told him what it was about: ‘It’s a very female-positive, femme-positive record.’ And he was just like, ‘Yeah. Say no more. I\'ve got this.’ And he did. He crushed it. To have somebody who\'s got patriarchal energy come through and say that, wanting to stand up and be there for a woman, wanting to have a woman that\'s an equal—that\'s real.” **mary magdalene** “Let’s just imagine for one second: Say Jesus and Mary Magdalene are really close, they\'re together all the time. She\'s his right-hand woman, she’s his confidante, she\'s healing people with him and a mystic in her own right. So, at that point, any man and woman that are spending that much time together, they\'re likely to be what? Lovers. Okay, cool. So, if Mary had Jesus\' children, that basically debunks the whole of history. Now, I\'m not saying that happened. What I\'m saying is that the idea of people thinking that might happen is potentially really dangerous. It’s easier to call her a whore, because as soon as you call a woman a whore, it devalues her. I see her as Jesus Christ\'s equal. She’s a male projection and, I think, the beginning of the patriarchy taking control of the narrative of women. Any woman that\'s done anything can be subject to that; I’ve been subject to that. It felt like an apt time to be talking about it.” **fallen alien** “When you\'re with someone, and they\'re sleeping, and you look at them, and you just think, \'No.\' For me, it’s that line, \[\'When the lights are on, I know you/When you fall asleep, I’ll kick you down/By the way you fell, I know you/Now you’re on your knees\'\]. You\'re just so sick of somebody\'s bullshit, you\'re just taking it all day, and then you\'re in bed next to them, and you\'re just like, ‘I can\'t take this anymore.’” **mirrored heart** “People always say, ‘Whoever you\'re with, they should be a reflection of yourself.’ So, if you\'re looking at someone and you think, ‘You\'re a shitbag,’ then you have to think about why it was that person, at that time, and what\'s connecting you both. What is the reflection? For others that have found a love that is a true reflection of themselves, they just remind me that I don\'t have that, a mirrored heart.” **daybed** “Have you ever forgotten how to spell a really simple word? To me, depression\'s a bit like that: Everything\'s quite abstract, and even slightly dizzy, but not in a happy way. It\'s like a very slow circus. Suddenly the fruit flies seem friendly, everything in the room just starts having a different meaning and you even have a different relationship with the way the sofa cushions smell. \[Masturbation\] is something to raise your endorphins, isn\'t it? It’s either that or try and go to the gym, or try and eat something good. You almost can\'t put it into words, but we\'ve all been there. I sing, \'Active are my fingers/Faux, my cunnilingus\': You\'re imagining someone going down on you, but they\'re actually not. You open your eyes, and you\'re just there, still on your sofa, still watching daytime TV.” **cellophane** “It\'s just raw, isn\'t it? It didn\'t need a thing. The vocal take that\'s on the record is the demo take. I had a Lyft arrive outside the studio and I’d just started playing the piano chords. I was like, ‘Hey, can you just give me like 20, 25 minutes?’ And I recorded it as is. I remember feeling like I wanted to cry, but I just didn\'t feel like it was that suitable to cry at a studio session. I often want everything to be really intricate and gilded, and I want to chip away at everything, and sculpt it, and mold it, and add layers. The thing I\'ve learned on *MAGDALENE* is that you don\'t need to do that all the time, and just because you can do something, it doesn\'t mean you should. That\'s been a real growing experience for me—as a musician, as a producer, as a singer, even as a dancer. Something in its most simple form is beautiful.”

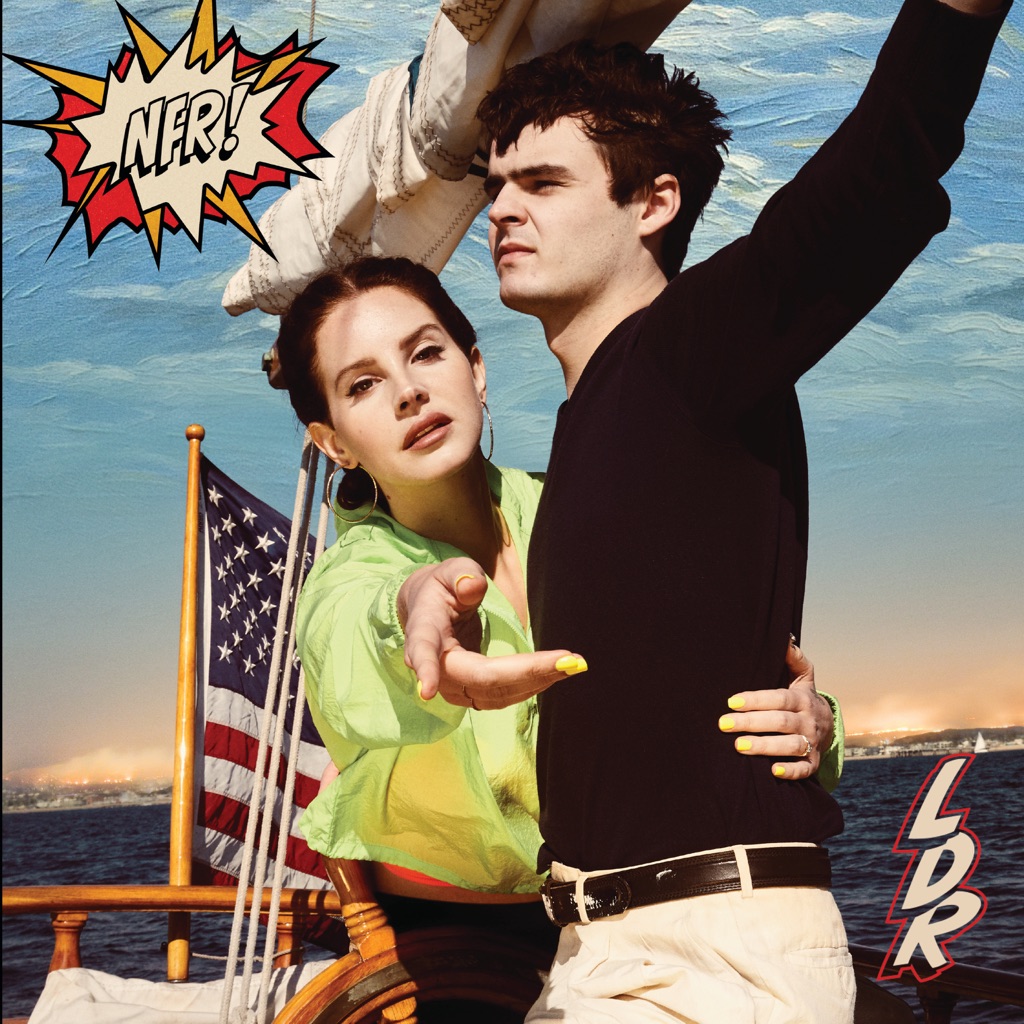

Part of the fun of listening to Lana Del Rey’s ethereal lullabies is the sly sense of humor that brings them back down to earth. Tucked inside her dreamscapes about Hollywood and the Hamptons are reminders—and celebrations—of just how empty these places can be. Here, on her sixth album, she fixes her gaze on another place primed for exploration: the art world. Winking and vivid, *Norman F\*\*\*\*\*g Rockwell!* is a conceptual riff on the rules that govern integrity and authenticity from an artist who has made a career out of breaking them. In a 2018 interview with Apple Music\'s Zane Lowe, Del Rey said working with songwriter Jack Antonoff (who produced the album along with Rick Nowels and Andrew Watt) put her in a lighter mood: “He was so *funny*,” she said. Their partnership—as seen on the title track, a study of inflated egos—allowed her to take her subjects less seriously. \"It\'s about this guy who is such a genius artist, but he thinks he’s the shit and he knows it,” she said. \"So often I end up with these creative types. They just go on and on about themselves and I\'m like, \'Yeah, yeah.\' But there’s merit to it also—they are so good.” This paradox becomes a theme on *Rockwell*, a canvas upon which she paints with sincerity and satire and challenges you to spot the difference. (On “The Next Best American Record,” she sings, “We were so obsessed with writing the next best American record/’Cause we were just that good/It was just that good.”) Whether she’s wistfully nostalgic or jaded and detached is up for interpretation—really, everything is. The album’s finale, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have - but I have it,” is packaged like a confessional—first-person, reflective, sung over simple piano chords—but it’s also flamboyantly cinematic, interweaving references to Sylvia Plath and Slim Aarons with anecdotes from Del Rey\'s own life to make us question, again, what\'s real. When she repeats the phrase “a woman like me,” it feels like a taunt; she’s spent the last decade mixing personas—outcast and pop idol, debutante and witch, pinup girl and poet, sinner and saint—ostensibly in an effort to render them all moot. Here, she suggests something even bolder: that the only thing more dangerous than a complicated woman is one who refuses to give up.

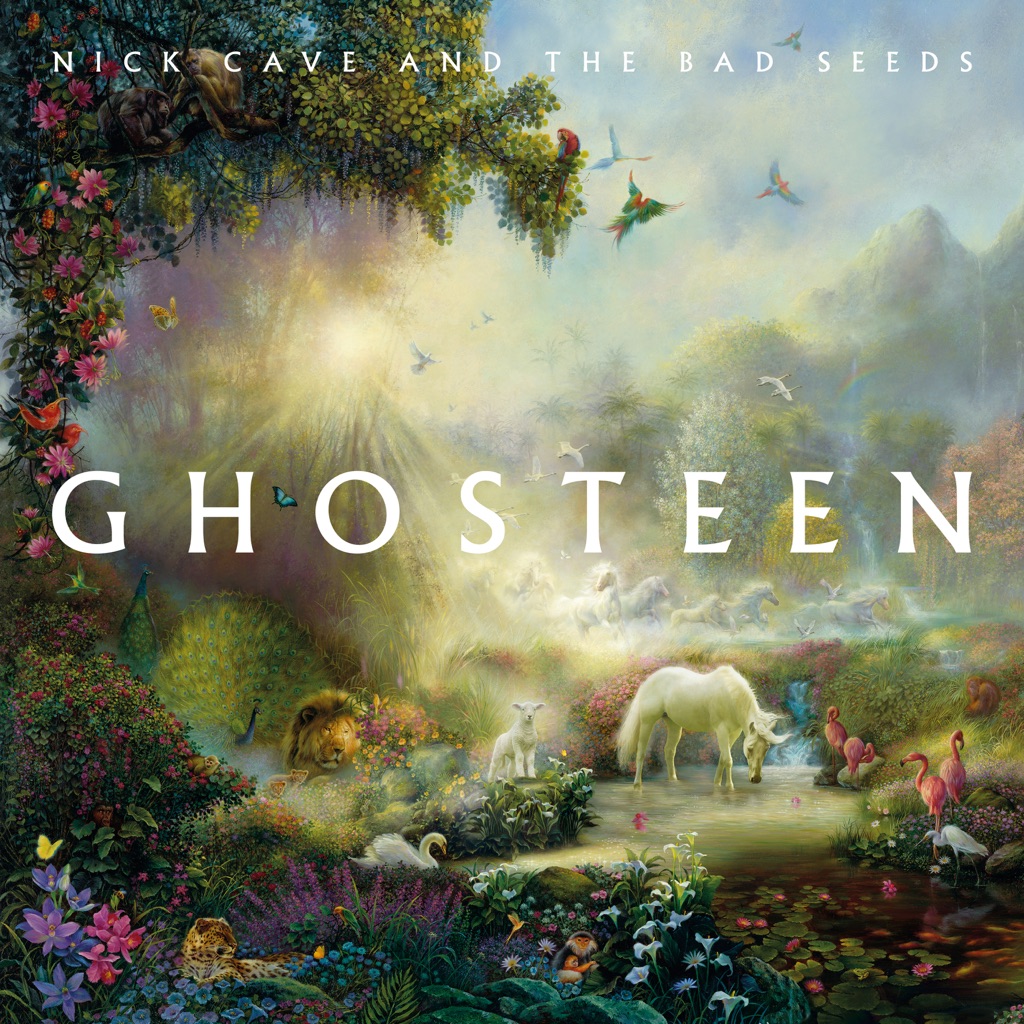

The cover art for Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ 17th album couldn’t feel more removed from the man once known as a snarling, terrifying prince of poetic darkness. This heavenly forest with its vibrant flowers, rays of sun, and woodland creatures feels comically opposed to anything Cave has ever represented—but perhaps that’s the point. This pastel fairy tale sets the scene for *Ghosteen*, his most minimalist, supernatural work to date, in which he slips between realms of fantasy and reality as a means to accept life and death, his past and future. In his very first post on The Red Hand Files—the website Cave uses to receive and respond to fan letters—he spoke of rebuilding his relationship with songwriting, which had been damaged while enduring the grief that followed his son Arthur’s death in 2015. He wrote, “I found with some practise the imagination could propel itself beyond the personal into a state of wonder. In doing so the colour came back to things with a renewed intensity and the world seemed clear and bright and new.” It is within that state of wonder that *Ghosteen* exists. “The songs on the first album are the children. The songs on the second album are their parents,” Cave has explained. Those eight “children” are misty, ambient stories of flaming mares, enchanted forests, flying ships, and the eponymous, beloved Ghosteen, described as a “migrating spirit.” The second album features two longer pieces, connected by the spoken-word “Fireflies.” He tells fantasy stories that allude to love and loss and letting go, and occasionally brings us back to reality with detailed memories of car rides to the beach and hotel rooms on rainy days. These themes aren’t especially new, but the feeling of this album is. There are no wild murder ballads or raucous, bluesy love songs. Though often melancholy, it doesn’t possess the absolute devastation and loneliness of 2016’s *Skeleton Tree*. Rather, these vignettes and symbolic myths are tranquil and gentle, much like the instrumentation behind them. With little more than synths and piano behind Cave’s vocals, *Ghosteen* might feel uneventful at times, but the calmness seems to help his imagination run free. On “Bright Horses,” he sings of “Horses broken free from the fields/They are horses of love, their manes full of fire.” But then he pulls back the curtain and admits, “We’re all so sick and tired of seeing things as they are/Horses are just horses and their manes aren’t full of fire/The fields are just fields, and there ain’t no lord… This world is plain to see, it don’t mean we can’t believe in something.” Through these dreamlike, surreal stories, Cave is finding his path to peace. And he’s learned that he isn’t alone on his journey. On “Galleon Ship,” he begins, “If I could sail a galleon ship, a long, lonely ride across the sky,” before realizing: “We are not alone, it seems, so many riders in the sky/The winds of longing in their sails, searching for the other side.”

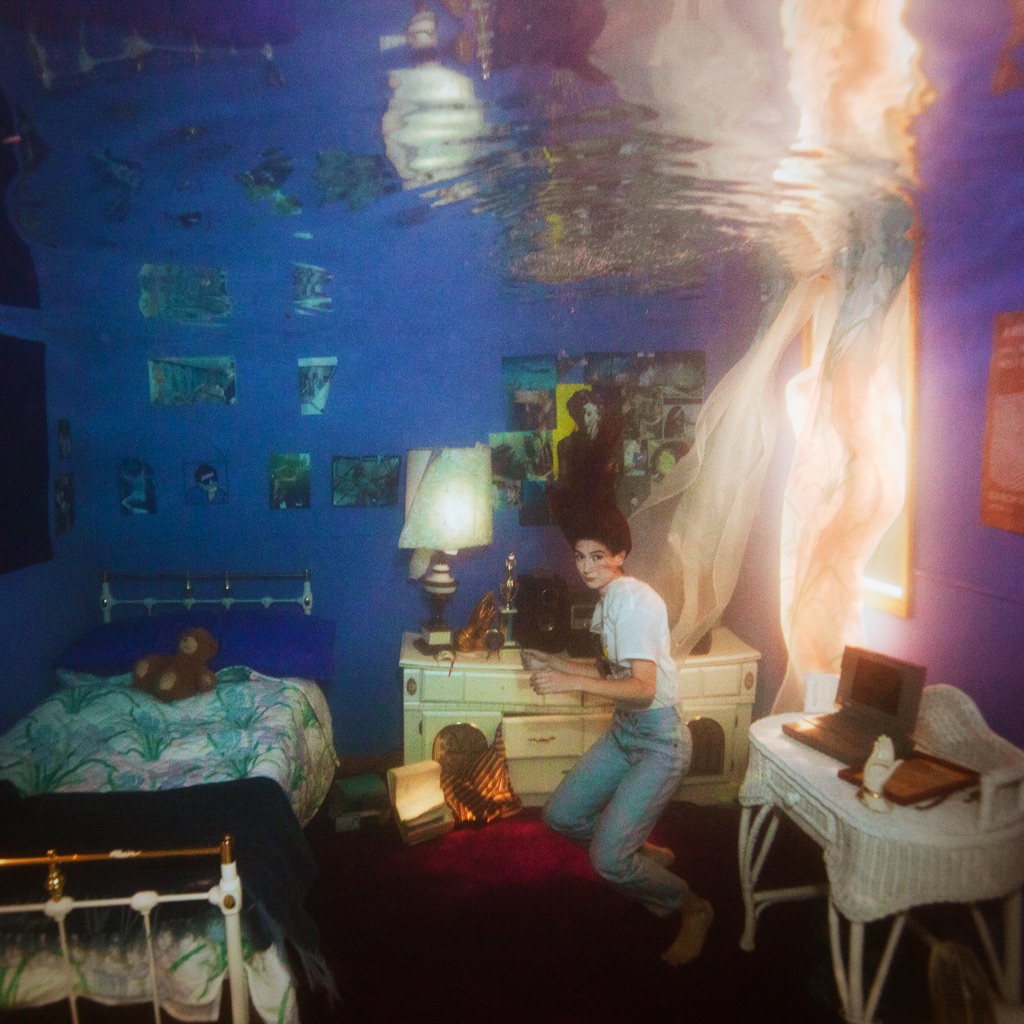

Beginning with the haunting alt-pop smash “Ocean Eyes” in 2016, Billie Eilish made it clear she was a new kind of pop star—an overtly awkward introvert who favors chilling melodies, moody beats, creepy videos, and a teasing crudeness à la Tyler, The Creator. Now 17, the Los Angeles native—who was homeschooled along with her brother and co-writer, Finneas O’Connell—presents her much-anticipated debut album, a melancholy investigation of all the dark and mysterious spaces that linger in the back of our minds. Sinister dance beats unfold into chattering dialogue from *The Office* on “my strange addiction,” and whispering vocals are laid over deliberately blown-out bass on “xanny.” “There are a lot of firsts,” says FINNEAS. “Not firsts like ‘Here’s the first song we made with this kind of beat,’ but firsts like Billie saying, ‘I feel in love for the first time.’ You have a million chances to make an album you\'re proud of, but to write the song about falling in love for the first time? You only get one shot at that.” Billie, who is both beleaguered and fascinated by night terrors and sleep paralysis, has a complicated relationship with her subconscious. “I’m the monster under the bed, I’m my own worst enemy,” she told Beats 1 host Zane Lowe during an interview in Paris. “It’s not that the whole album is a bad dream, it’s just… surreal.” With an endearingly off-kilter mix of teen angst and experimentalism, Billie Eilish is really the perfect star for 2019—and here is where her and FINNEAS\' heads are at as they prepare for the next phase of her plan for pop domination. “This is my child,” she says, “and you get to hold it while it throws up on you.” **Figuring out her dreams:** **Billie:** “Every song on the album is something that happens when you’re asleep—sleep paralysis, night terrors, nightmares, lucid dreams. All things that don\'t have an explanation. Absolutely nobody knows. I\'ve always had really bad night terrors and sleep paralysis, and all my dreams are lucid, so I can control them—I know that I\'m dreaming when I\'m dreaming. Sometimes the thing from my dream happens the next day and it\'s so weird. The album isn’t me saying, \'I dreamed that\'—it’s the feeling.” **Getting out of her own head:** **Billie:** “There\'s a lot of lying on purpose. And it\'s not like how rappers lie in their music because they think it sounds dope. It\'s more like making a character out of yourself. I wrote the song \'8\' from the perspective of somebody who I hurt. When people hear that song, they\'re like, \'Oh, poor baby Billie, she\'s so hurt.\' But really I was just a dickhead for a minute and the only way I could deal with it was to stop and put myself in that person\'s place.” **Being a teen nihilist role model:** **Billie:** “I love meeting these kids, they just don\'t give a fuck. And they say they don\'t give a fuck *because of me*, which is a feeling I can\'t even describe. But it\'s not like they don\'t give a fuck about people or love or taking care of yourself. It\'s that you don\'t have to fit into anything, because we all die, eventually. No one\'s going to remember you one day—it could be hundreds of years or it could be one year, it doesn\'t matter—but anything you do, and anything anyone does to you, won\'t matter one day. So it\'s like, why the fuck try to be something you\'re not?” **Embracing sadness:** **Billie:** “Depression has sort of controlled everything in my life. My whole life I’ve always been a melancholy person. That’s my default.” FINNEAS: “There are moments of profound joy, and Billie and I share a lot of them, but when our motor’s off, it’s like we’re rolling downhill. But I’m so proud that we haven’t shied away from songs about self-loathing, insecurity, and frustration. Because we feel that way, for sure. When you’ve supplied empathy for people, I think you’ve achieved something in music.” **Staying present:** **Billie:** “I have to just sit back and actually look at what\'s going on. Our show in Stockholm was one of the most peak life experiences we\'ve had. I stood onstage and just looked at the crowd—they were just screaming and they didn’t stop—and told them, \'I used to sit in my living room and cry because I wanted to do this.\' I never thought in a thousand years this shit would happen. We’ve really been choking up at every show.” FINNEAS: “Every show feels like the final show. They feel like a farewell tour. And in a weird way it kind of is, because, although it\'s the birth of the album, it’s the end of the episode.”

Singer-songwriter Natalie Mering’s fourth album as Weyes Blood conjures the feeling of a beautiful object on a shelf just out of reach: You want to touch it, but you can’t, and so you do the next best thing—you dream about it, ache for it, and then you ache some more. Grand, melodramatic, but keenly self-aware, the music here pushes Mering’s \'70s-style chamber pop to its cinematic brink, suffusing stories of everything from fumbled romance (the McCartney-esque “Everyday”) to environmental apocalypse (“Wild Time”) with a dreamy, foggy almost-thereness both gorgeous and profoundly unsettling. A self-described “nostalgic futurist,” Mering doesn’t recreate the past so much as demonstrate how the past is more or less a fiction to begin with, a story we love hearing no matter how sad its unreachability makes us. Hence the album’s centerpiece, “Movies,” which wonders—gorgeously, almost religiously—why life feels so messy by comparison. As to the thematic undercurrent of apocalypse, well, if extinction is as close as science says it is, we might as well have something pretty to play us out.

The phantom zone, the parallax, the upside down—there is a rich cultural history of exploring in-between places. Through her latest, Titanic Rising, Weyes Blood (a.k.a. Natalie Mering) has, too, designed her own universe to soulfully navigate life’s mysteries. Maneuvering through a space-time continuum, she intriguingly plays the role of melodic, sometimes melancholic, anthropologist. Tellingly, Mering classifies Titanic Rising as the Kinks meet WWII or Bob Seger meets Enya. The latter captures the album’s willful expansiveness (“You can tell there’s not a guy pulling the strings in Enya’s studio,” she notes, admiringly). The former relays her imperative to connect with listeners. “The clarity of Bob Seger is unmistakable. I’m a big fan of conversational songwriting,” she adds. “I just try to do that in a way that uses abstract imagery as well.” “An album is like a Rubik’s Cube,” she says. “Sometimes you get all the dimensions—the lyrics, the melody, the production—to line up. I try to be futuristic and ancient at once, which is a difficult alchemy. It’s taken a lot of different tries to get it right.” As concept-album as it may sound, it’s also a devoted exercise in realism, albeit occasionally magical. Here, the throwback-cinema grandeur of “A Lot’s Gonna Change” gracefully coexists with the otherworldly title track, an ominous instrumental. Titanic Rising, written and recorded during the first half of 2018, is the culmination of three albums and years of touring: stronger chops and ballsier decisions. It’s an achievement in transcendent vocals and levitating arrangements—one she could reach only by flying under the radar for so many years. “I used to want to belong,” says the L.A. based musician. “I realized I had to forge my own path. Nobody was going to do that for me. That was liberating. I became a Joan of Arc solo musician.” The Weyes Blood frontwoman grew up singing in gospel and madrigal choirs. “Classical and Renaissance music really influenced me,” says Mering, who first picked up a guitar at age 8. (Listen closely to Titanic Rising, and you’ll also hear the jazz of Hoagy Carmichael mingle with the artful mysticism of Alejandro Jodorowsky and the monomyth of scholar Joseph Campbell.) “Something to Believe,” a confessional that makes judicious use of the slide guitar, touches on that cosmological upbringing. “Belief is something all humans need. Shared myths are part of our psychology and survival,” she says. “Now we have a weird mishmash of capitalism and movies and science. There have been moments where I felt very existential and lost.” As a kid, she filled that void with Titanic. (Yes, the movie.) “It was engineered for little girls and had its own mythology,” she explains. Mering also noticed that the blockbuster romance actually offered a story about loss born of man’s hubris. “It’s so symbolic that The Titanic would crash into an iceberg, and now that iceberg is melting, sinking civilization.” Today, this hubris also extends to the relentless adoption of technology, at the expense of both happiness and attention spans. The track “Movies” marks another Titanic-related epiphany, “that movies had been brainwashing people and their ideas about romantic love.” To that end, Mering has become an expert at deconstructing intimacy. Sweeping and string-laden, “Andromeda” seems engineered to fibrillate hearts. “It’s about losing your interest in trying to be in love,” she says. “Everybody is their own galaxy, their own separate entity. There is a feeling of needing to be saved, and that’s a lot to ask of people.” Its companion track, “Everyday,” “is about the chaos of modern dating,” she says, “the idea of sailing off onto your ships to nowhere to deal with all your baggage.” But Weyes Blood isn’t one to stew. Her observations play out in an ethereal saunter: far more meditative than cynical. “I experience reality on a slower, more hypnotic level,” she says. “I’m a more contemplative kind of writer.” To Mering, listening and thinking are concurrent experiences. “There are complicated influences mixed in with more relatable nostalgic melodies,” she says. “In my mind my music feels so big, a true production. I’m not a huge, popular artist, but I feel like one when I’m in the studio. But it’s never taking away from the music. I’m just making a bigger space for myself.”

When Chris Stewart set out to write and record his third album as Black Marble, he was newly living in Los Angeles, fresh off a move from New York. The environment brought much excitement and possibility, but the distance had proved too much for the car he brought along. With it out of commission indefinitely, he purchased a bus pass and planned his daily commute from his Echo Park apartment to his downtown studio, where he began to shape Bigger Than Life. The route wound all through the city, from the small local shops of Echo Park to the rising glass of the business district, to the desperation of Skid Row. The hurried energy of the environment provided a backdrop for the daily trip. When Stewart finally arrived at his studio, he’d look through his window at the mountains and the sky, seeing the beauty that makes L.A. unique — the same beauty his fellow commuters, some pushed to the edge of human endurance, had seen. That was the headspace he was in when he began to map out the syncopated drums and staccato arpeggiation of Bigger Than Life, an ode to his new condition and a shimmering synth-pop response to its cacophony. “The album comes out of seeing and experiencing a lot of turmoil but wanting to create something positive out of it,” Stewart explains. “I wanted to take a less selfish approach on this record. Maybe I’m just getting older, but that approach starts to feel a little self-indulgent. Like, ‘Oh, look at me I’m so complicated, I get that life isn’t fair,’ It’s like, yeah, so does everyone. So with this record, it’s less about how I see things and more about the way things just are. Seeing myself as a part of a lineage of people trying to do a little something instead of trying to create a platform for myself individually.” As with every Black Marble album, Stewart recorded, produced, and played everything you hear on Bigger Than Life using entirely analog gear, though the process was new. This time around, he wrote everything on his MPC and sequenced it live to his synths — only using the computer to record, not to create. “I try new approaches every time, which helps me stay engaged but also its kind of a trick I play on the creative side of my brain,” Stewart says. “Keeping one side of my mind busy on organizational creativity I think frees up the other side where the inspirational creativity comes from.” He also approached his vocals in a new way this time, bringing them forward in the mix and retreating from the reverb-drenched affect he has utilized in the past. The result is the finest vocal performance of his career, still processed and distant-sounding, but more immediate than ever before. The beguiling vocal hooks, always present in Black Marble’s music but formerly obscured by the production, are now the focal point of songs like “One Eye Open” and “Feels.” “Everything about this record from the album art to the title, to the themes to all the sounds on the record is my response to this particular time,” Stewart says. “Music is what I choose to do in response to this time. I think it’s a time where it’s easy to feel powerless, but I’m trying to express humility, because I think gratitude comes from humility and that’s a powerful thing. The people that practice the least humility also seem to be the least grateful. I’m learning the two are connected.”

On her fifth proper full-length album, Sharon Van Etten pushes beyond vocals-and-guitar indie rock and dives headlong into spooky maximalism. With production help from John Congleton (St. Vincent), she layers haunting drones with heavy, percussive textures, giving songs like “Comeback Kid” and “Seventeen” explosive urgency. Drawing from Nick Cave, Lucinda Williams, and fellow New Jersey native Bruce Springsteen, *Remind Me Tomorrow* is full of electrifying anthems, with Van Etten voicing confessions of reckless, lost, and sentimental characters. The album challenges the popular image of Van Etten as *just* a singer-songwriter and illuminates her significant talent as composer and producer, as an artist making records that feel like a world of their own.

With powerhouse pipes, razor-sharp wit, and a tireless commitment to self-love and self-care, Lizzo is the fearless pop star we needed. Born Melissa Jefferson in Detroit, the singer and classically trained flautist discovered an early gift for music (“It chose me,” she tells Apple Music) and began recording in Minneapolis shortly after high school. But her trademark self-confidence came less naturally. “I had to look deep down inside myself to a really dark place to discover it,” she says. Perhaps that’s why her third album, *Cuz I Love You*, sounds so triumphant, with explosive horns (“Cuz I Love You”), club drums (“Tempo” featuring Missy Elliott), and swaggering diva attitude (“No, I\'m not a snack at all/Look, baby, I’m the whole damn meal,” she howls on the instant hit “Juice\"). But her brand is about more than mic-drop zingers and big-budget features. On songs like “Better in Color”—a stomping, woke plea for people of all stripes to get together—she offers an important message: It’s not enough to love ourselves, we also have to love each other. Read on for Lizzo’s thoughts on each of these blockbuster songs. **“Cuz I Love You”** \"I start every project I do with a big, brassy orchestral moment. And I do mean *moment*. It’s my way of saying, ‘Stand the fuck up, y’all, Lizzo’s here!’ This is just one of those songs that gets you amped from the jump. The moment you hear it, you’re like, ‘Okay, it’s on.’ It’s a great fucking way to start an album.\" **“Like a Girl”** \"We wanted take the old cliché and flip it on its head, shaking out all the negative connotations and replacing them with something empowering. Serena Williams plays like a girl and she’s the greatest athlete on the planet, you know? And what if crying was empowering instead of something that makes you weak? When we got to the bridge, I realized there was an important piece missing: What if you identify as female but aren\'t gender-assigned that at birth? Or what if you\'re male but in touch with your feminine side? What about my gay boys? What about my drag queens? So I decided to say, ‘If you feel like a girl/Then you real like a girl,\' and that\'s my favorite lyric on the whole album.\" **“Juice”** \"If you only listen to one song from *Cuz I Love You*, let it be this. It’s a banger, obviously, but it’s also a state of mind. At the end of the day, I want my music to make people feel good, I want it to help people love themselves. This song is about looking in the mirror, loving what you see, and letting everyone know. It was the second to last song that I wrote for the album, right before ‘Soulmate,\' but to me, this is everything I’m about. I wrote it with Ricky Reed, and he is a genius.” **“Soulmate”** \"I have a relationship with loneliness that is not very healthy, so I’ve been going to therapy to work on it. And I don’t mean loneliness in the \'Oh, I don\'t got a man\' type of loneliness, I mean it more on the depressive side, like an actual manic emotion that I struggle with. One day, I was like, \'I need a song to remind me that I\'m not lonely and to describe the type of person I *want* to be.\' I also wanted a New Orleans bounce song, \'cause you know I grew up listening to DJ Jubilee and twerking in the club. The fact that l got to combine both is wild.” **“Jerome”** \"This was my first song with the X Ambassadors, and \[lead singer\] Sam Harris is something else. It was one of those days where you walk into the studio with no expectations and leave glowing because you did the damn thing. The thing that I love about this song is that it’s modern. It’s about fuccboi love. There aren’t enough songs about that. There are so many songs about fairytale love and unrequited love, but there aren’t a lot of songs about fuccboi love. About when you’re in a situationship. That story needed to be told.” **“Cry Baby”** “This is one of the most musical moments on a very musical album, and it’s got that Minneapolis sound. Plus, it’s almost a power ballad, which I love. The lyrics are a direct anecdote from my life: I was sitting in a car with a guy—in a little red Corvette from the ’80s, and no, it wasn\'t Prince—and I was crying. But it wasn’t because I was sad, it was because I loved him. It was a different field of emotion. The song starts with \'Pull this car over, boy/Don\'t pretend like you don\'t know,’ and that really happened. He pulled the car over and I sat there and cried and told him everything I felt.” **“Tempo”** “‘Tempo\' almost didn\'t make the album, because for so long, I didn’t think it fit. The album has so much guitar and big, brassy instrumentation, but ‘Tempo’ was a club record. I kept it off. When the project was finished and we had a listening session with the label, I played the album straight through. Then, at the end, I asked my team if there were any honorable mentions they thought I should play—and mind you, I had my girls there, we were drinking and dancing—and they said, ‘Tempo! Just play it. Just see how people react.’ So I did. No joke, everybody in the room looked at me like, ‘Are you crazy? If you don\'t put this song on the album, you\'re insane.’ Then we got Missy and the rest is history.” **“Exactly How I Feel”** “Way back when I first started writing the song, I had a line that goes, ‘All my feelings is Gucci.’ I just thought it was funny. Months and months later, I played it at Atlantic \[Records\], and when that part came up, I joked, ‘Thanks for the Gucci feature, guys!\' And this executive says, ‘We can get Gucci if you want.\' And I was like, ‘Well, why the fuck not?\' I love Gucci Mane. In my book, he\'s unproblematic, he does a good job, he adds swag to it. It doesn’t go much deeper than that, to be honest. The rest of the song has plenty of meaning: It’s an ode to being proud of your emotions, not feeling like you have to hide them or fake them, all that. But the Gucci feature was just fun.” **“Better in Color”** “This is the nerdiest song I have ever written, for real. But I love it so much. I wanted to talk about love, attraction, and sex *without* talking about the boxes we put those things in—who we feel like we’re allowed to be in love with, you know? It shouldn’t be about that. It shouldn’t be about gender or sexual orientation or skin color or economic background, because who the fuck cares? Spice it up, man. Love *is* better in color. I don’t want to see love in black and white.\" **“Heaven Help Me”** \"When I made the album, I thought: If Aretha made a rap album, what would that sound like? ‘Heaven Help Me’ is the most Aretha to me. That piano? She would\'ve smashed that. The song is about a person who’s confident and does a good job of self-care—a.k.a. me—but who has a moment of being pissed the fuck off and goes back to their defensive ways. It’s a journey through the full spectrum of my romantic emotions. It starts out like, \'I\'m too cute for you, boo, get the fuck away from me,’ to \'What\'s wrong with me? Why do I drive boys away?’ And then, finally, vulnerability, like, \'I\'m crying and I\'ve been thinking about you.’ I always say, if anyone wants to date me, they just gotta listen to this song to know what they’re getting into.\" **“Lingerie”** “I’ve never really written sexy songs before, so this was new for me. The lyrics literally made me blush. I had to just let go and let God. It’s about one of my fantasies, and it has three different chord changes, so let me tell you, it was not easy to sing. It was very ‘Love On Top’ by Beyoncé of me. Plus, you don’t expect the album to end on this note. It leaves you wanting more.”

It’s no longer possible to call Bring Me the Horizon a rock band. On their sixth album, the Sheffield four-piece draw on so many genres and ideas, they evade any attempt at categorization. “I’ve always thought there’s too many borders, too many bridges, that people don\'t cross in music,” frontman Oli Sykes tells Apple Music. “The real world has too much of that as it is. I guess that’s our crusade.” *amo*—Portuguese for “love”—stretches from bittersweet pop to electronic experimentalism, calling on an art-pop visionary, a legendary beatboxer, and an extreme-metal icon along the way. Here, Sykes breaks down their crusade, track by track. **i apologise if you feel something** “We knew it was almost impossible to give anyone a heads- up of what this album was going to sound like. It was important for that first track just to be like, ‘Forget whatever you think it’s going to sound like, because you\'re not going to be able to guess from anything we’ve shown you before.” **MANTRA** “At the end of the writing process, I had a bit of a meltdown. Even though we did have a lot of stuff, we didn\'t have that song where we were like, ‘This is what we\'re going to show the world first.’ ‘MANTRA’ was born out of that: \[It\'s\] not so different that people are alienated, but \[it\'s\] giving you a taste that it\'s not the same as the last record. It’s about the similarities between starting a relationship and starting a cult—how you can throw away your whole life for something and you have to put all belief and faith into this thing that might or might not be right for you.” **nihilist blues (feat. Grimes)** “We had no idea if Grimes would even be interested in doing a song with us. But she was really just gushing, like, ‘This is one of the greatest songs I’ve ever heard.’ I’ve always loved dance songs that had a dark edge—something almost primitive that triggers me. Getting it into our sound was really exciting.” **in the dark** “When we first started writing this, it sounded more like something we would have written on the last album. But it turned into this dark, poppy ballad that we all really loved. I love bittersweet, dark pop songs.” **wonderful life (feat. Dani Filth)** “I did all the lyrics and vocals in a day in the studio. I think it was the day The 1975 released ‘Give Yourself a Try\'—that inspired me to get up on the mic and just say stuff that came out. I dropped \[Cradle of Filth frontman\] Dani Filth a line on Instagram to see if he’d be interested in working on the song. He didn\'t believe it was me at first. I think he said something very quintessentially English, like ‘If this is indeed you, young man, then, yes, I would love to.’” **ouch** “It was one of those bittersweet realizations that you’re happy something\'s happened, but a lot of heartache or pain came with getting to that realization. I just wanted to present the lyrics in a way that wasn’t too dark, a way that feels low-key—and the jammy sound came from that.” **medicine** “‘ouch’ is a kind of prelude to this, quite linked to its vibe. It\'s that idea that you often don’t realize you’re in a toxic relationship until you\'re out the other side. It\'s not like a ‘f\*\*\* you’ song, it\'s just, ‘This is finally me having my say, and I\'m actually going to think about how it affected me and not how it affected you for once.’” **sugar honey ice & tea** “It sounds ridiculous, but just with the drums and everything, we approached it differently and ended up making something that felt quite fresh. It started off a lot more, dare I say, hip-hop- sounding, electro, and there’s elements in there that still remain. We kept a little bit of each version it went through.” **why you gotta kick me when I’m down?** “I was quite scolded by the way I was treated when I was going through hard times with my divorce and stuff that no one knew about. I was quite hurt by the way I was treated by people that I thought were there for me. The song’s saying, ‘I totally get it, it\'s fine, but stop pretending it’s coming from a place of love or care, because it’s not—it’s coming from a place of your own problems where you don\'t want someone to change or grow.’” **fresh bruises** “This was a very organic song, it came very naturally. It was one we just wanted to make—a song that wasn’t verse, chorus, verse, chorus, but more of an electronic vibe. The kind of music I listen to is like that, centered around a hook, and it has a drop and it has a buildup. Not in an EDM sense, but more like lo-fi electronic, avant-garde. It just felt cool to make something more jammy and free like that.” **mother tongue** “\[Love\] is really all this addresses—saying to someone, ‘There’s no need to play games, just be open about the way you feel and everything will be fine.’” **heavy metal (feat. Rahzel)** “Getting \[beatboxing legend\] Rahzel was \[keyboardist\] Jordan \[Fish\]’s idea, because we had this beat that almost sounded like there was beatboxing on it. We used to be this death-metal-sounding, crazy band, and now we play pop music—it’s something that pisses some people off. We’re so confident and proud of what we\'re doing, and at the same time, we’re human and we have our insecurities. This track is just a little in-joke that it can still ruin our day if some kid goes, ‘This is the biggest load of s\*\*\* I’ve ever heard. What happened to this band?’” **i don’t know what to say** “It’s about a friend that passed away from cancer. It’s me trying to figure out what to say in that situation and my regret that I didn\'t see him in his final few days—but also an explanation why. To do my best to talk about how speechless I am at his strength and his courage, and the way he took it all in stride. You’ll hear that story echoed from so many people who have lost people to cancer—they just become unrealistically strong and courageous.”

\"Kids in the Dark\" ushers in Bat for Lashes\' fifth album on a wave of cinematic synths that sounds like sunset and open road. It\'s the perfect introduction to a conceptual cycle that finds London-bred singer-songwriter Natasha Khan inhaling a throwback version of her new LA home base. Khan is no stranger to inhabiting complex characters (the widow of 2016\'s *The Bride*) and motifs (the fairy-tale fantasies of her debut, *Fur and Gold*), and likewise, *Lost Girls* hinges on Nikki Pink, whom Khan has described as \"a more Technicolor version\" of herself. In addition to its clear nods to the 1987 film *The Lost Boys*, the record takes cues from the original screenplay Khan was working on upon her relocation, inspired by \'80s kid flicks and vampire films, and blows them out in neon songs, tinged with drama and romance. The saxophone-laden instrumental \"Vampires\" calls to mind retro climactic scenes where imminent peril is blocked out by hope, while the disarmingly bright \"So Good\" embodies the kind of glamorous and carefree existence we often ascribe to the past. \"Why does it hurt so good?\" she begs on the hook, projecting all of the delight and none of the suffering. Khan is a master of conjuring thematic atmosphere, but here, she inhabits her era with particular gusto. In a pop culture landscape that remains obsessed with nostalgia, on *Lost Girls*, Khan transforms the familiar tropes of the past into something that feels fresh and revelatory—we are able to see old things anew, through the eyes of a person she\'s never been in a time and place she\'s never lived.

Over the decade-plus since he arrived seemingly fully formed as the platonic ideal of indie DIY made good, Justin Vernon has pushed back against the notion that he and Bon Iver are synonymous. He is quick to deflect credit to core longtime collaborators like Chris Messina and Brad Cook, while April Base, the studio and headquarters he built just outside his native Eau Claire, Wisconsin, has become a cultural hub playing host to a variety of experimental projects. The fourth Bon Iver full-length album shines a brighter light on Bon Iver as a unit with many moving parts: Renovations to April Base sent operations to Sonic Ranch in Tornillo, Texas, for much of the production, but the spirit of improvisation and tinkering and revolving-door personnel that marked 2016’s out-there *22, A Million* remained intact. “This record in particular felt like a very outward record; Justin felt outward to me,” says Cook, who grew up with Vernon and has played with him through much of his career. “He felt like he was in a new place, and he was reaching out for new input in a different way. We\'re just more in the foreground inevitably because the process became just a little bit more transparent.” Vernon, Cook, and Messina talk through that process on each of *i,i*\'s 13 tracks. **“Yi”** Justin Vernon: “That was a phone recording of me and my friend Trevor screwing around in a barn, turning a radio on and off. We chopped it up for about five years, just a hundred times. There’s something in that ‘Are you recording? Are you recording?’ that felt like the spirit that flows into the next song.” **“iMi”** Brad Cook: “It was like an old friend that you didn\'t know what to do with for a long time. When we got to Texas, a lot of different people took a crack at trying to make something out of that song. And then Andrew Sarlo, who works with Big Thief and is just a badass young producer, he took the whack that broke through the wall. Once the band got their hands on it, Justin added some of the acoustic stuff to it, and it just totally blew it wide open.” **“We”** Vernon: “I was working on this idea one morning with this engineer, Josh Berg, who happened to be out with us. And this guy Bobby Raps from Minneapolis was also at my studio just kind of hanging around, and he brought this dude named Wheezy who does some Young Thug beats, some Future beats. So I had this little baritone-guitar bass loop thing, and Wheezy put his beat on there. All these songs had a life, or had a birth, before Texas, but Texas was like graduation for every single one. That\'s why we went for so long and allowed for so much perspective to sink into all the tunes. It\'s a fucking banger; I love that one.” **“Holyfields,”** Vernon: “The whole song is an improvised moment with barely any editing, and we just improv\'d moves. I sang some scratch vocals that day when we made it up, and they were weirdly close to what ended up being on the album. We didn\'t really chop away at that one—it kind of just was born with all its hair and everything.” **“Hey, Ma”** Vernon: “It just felt like a good strong song; we knew people would get it in their head. A couple of these tunes, and some of the tunes from the last album, I sort of peck around the studio with BJ Burton from time to time, and 90 percent of the stuff we make is death techno or something. So, there\'s another one that sort of just hung around with a stake in the ground, so to speak. And then our team—the three of us and the rest of everyone—just kept etching away at it, and it ended up becoming the song that felt emblematic of the record.” **\"U (Man Like)\"** Cook: “We had Bruce \[Hornsby\] come out to Justin\'s studio for a session for his *Absolute Zero* record. Bruce was playing a bunch of musical ideas that he had just sort of done at his house, and that piano figure in that song—I feel like we were tracking 15 seconds later. It was like, \'Wait, can we listen to this again?\'” Vernon: “I\'m not so good at coming up with full songs on the spot, but I can kind of map them out with my voice, or inflection. Then it takes a long time to chip away at them. Messina might have an idea for what that line should be, or Brad, or me. The melody that I sang that first day probably sounds remarkably like the melody that\'s on the album.” **“Naeem”** Vernon: “We did a collaboration with a dance group called TU Dance, and that was one of the songs. So we\'ve been performing \'Naeem\' as a part of this thing for a while. It\'s in a different state, but it\'s the finale of this big collaboration. And it just seemed very anthemic, and a very important part of whatever this record was going to be. It feels really nice to have a little bit more straightforward—not always bombastic, not always sonically trying to flip your lid or something.” **“Jelmore”** Vernon: “Basically an improvisation with me and this guy Buddy Ross. Again I probably didn\'t sing any final lyrics, but it\'s based on an improvisation, much like the song \'\_\_\_\_45\_\_\_\_\_\' from \[*22, A Million*\]. And when we were down outside El Paso, me and Chris were over on one part of this studio and Brad was with the band in a big studio across the property, and they sort of took \'Jelmore\' upon themselves and filled it in with all the lovely live-ness that\'s there. As the record goes on, it feels like there\'s a lot of these things that are sort of bare but have a lot of live energy to them.” **“Faith”** Vernon: “A basement improv that sat around for many years; maybe could have been on the last album, was for a while. I don\'t know, man—it\'s a song about having faith.” **“Marion”** Chris Messina: “I think that\'s one that Justin\'s been noodling around with for a while; for a few years, he would pick up that guitar and you would just kind of hear that riff. And we didn\'t really know what was going to happen to it. It\'s another one that exists in the TU Dance show. But what\'s cool about the version that\'s on the record is we did that as a live take with a six-piece ensemble that Rob Moose wrote for and conducted, and it was saxophone, trombone, trumpet, French horn, harmonica, and I think that\'s it that we did live. And then Justin was singing live and playing guitar live.” **“Salem”** Vernon: “OP-1 loop, weird Indigo Girls/Rickie Lee Jones vibes. I got really into acid and the Grateful Dead this year, so there\'s definitely some early psych vibes in there. The record really is supposed to be thought of as the fall record for this band, if you think of the other ones as seasons. Salem and burning leaves—these longings and these deaths, it\'s very much in there in that song, so it\'s a really autumn-y song.” **“Sh’Diah”** Vernon: “It stands for Shittiest Day in American History—the day after Trump got elected. It\'s another that sort of hung around as an improvised idea, and we finally got to figure out where we\'re going to land Mike Lewis, our favorite instrumentalist alive today in music. He gets to play over it, and the band got to do all this crazy layering over it. It\'s just one of my favorite moods on the album.” **“RABi”** Messina: “Justin\'s singing a cool thing on it, the guitar vibe is comforting and persistent, but we just weren\'t really sure where it needed to go. And then Brad and the rest of the dudes got their hands on it and it came back as just a dream sequence; it was so sick. We all kind of heard it and it was like, whoa, how can this not close out the record? This is definitely \'see you later.\'” Vernon: “Just some ‘life feels good now, don\'t it?\' There\'s a lot to be sad about, there\'s a lot to be confused about, there\'s a lot to be thankful for. And leaning on gratitude and appreciation of the people around you that make you who you are, make you feel safe, and provide that shelter so you can be who you want to be, there\'s still that impetus in life. We need that. It\'s a nice way to close the record, we all thought.”

In the three years since her seminal album *A Seat at the Table*, Solange has broadened her artistic reach, expanding her work to museum installations, unconventional live performances, and striking videos. With her fourth album, *When I Get Home*, the singer continues to push her vision forward with an exploration of roots and their lifelong influence. In Solange\'s case, that’s the culturally rich Houston of her childhood. Some will know these references — candy paint, the late legend DJ Screw — via the city’s mid-aughts hip-hop explosion, but through Solange’s lens, these same touchstones are elevated to high art. A diverse group of musicians was tapped to contribute to *When I Get Home*, including Tyler, the Creator, Chassol, Playboi Carti, Standing on the Corner, Panda Bear, Devin the Dude, The-Dream, and more. There are samples from the works of under-heralded H-town legends: choreographer Debbie Allen, actress Phylicia Rashad, poet Pat Parker, even the rapper Scarface. The result is a picture of a particular Houston experience as only Solange could have painted it — the familiar reframed as fantastic.

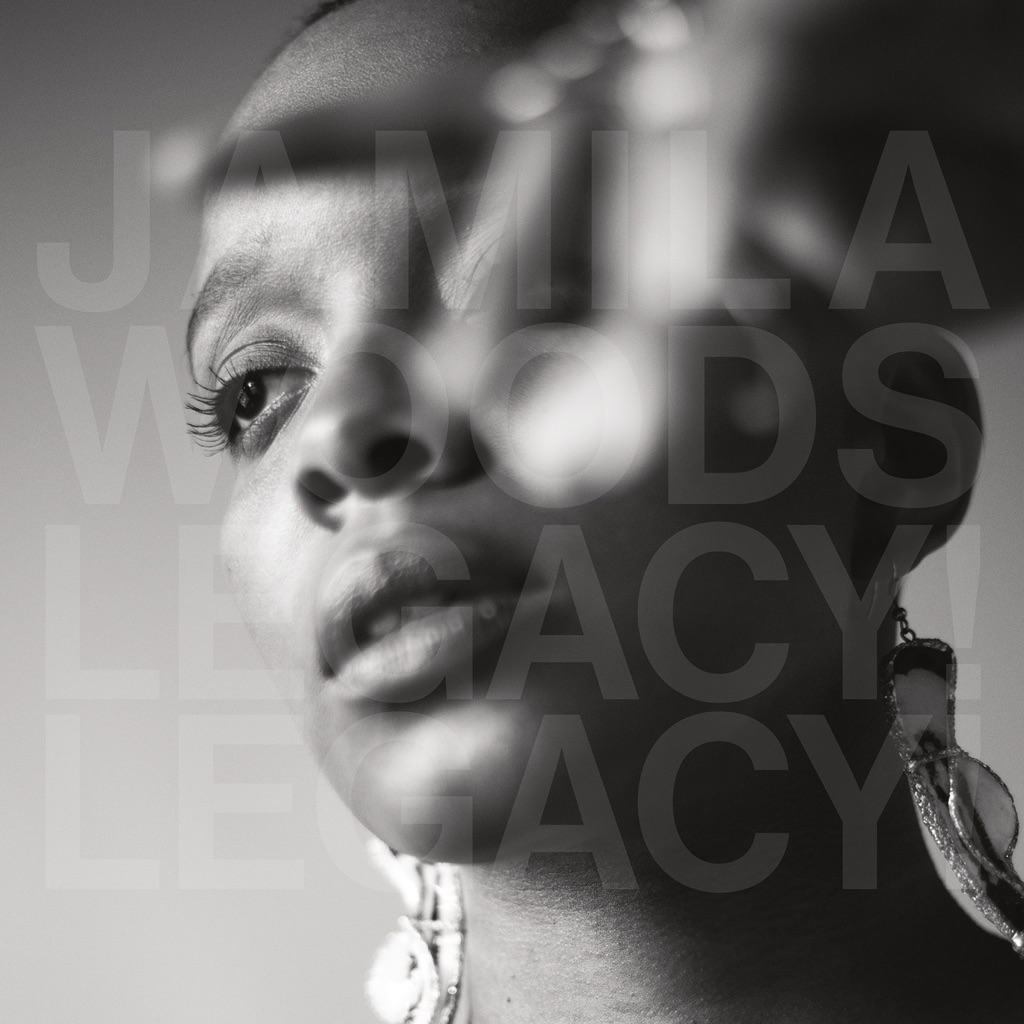

There’s nothing all that subtle about Jamila Woods naming each of these all-caps tracks after a notable person of color. Still, that’s the point with *LEGACY! LEGACY!*—homage as overt as it is original. True to her own revolutionary spirit, the Chicago native takes this influential baker’s dozen of songs and masterfully transmutes their power for her purposes, delivering an engrossingly personal and deftly poetic follow-up to her formidable 2016 breakthrough *HEAVN*. She draws on African American icons like Miles Davis and Eartha Kitt as she coos and commands through each namesake cut, sparking flames for the bluesy rap groove of “MUDDY” and giving flowers to a legend on the electro-laced funk of “OCTAVIA.”

In the clip of an older Eartha Kitt that everyone kicks around the internet, her cheekbones are still as pronounced as many would remember them from her glory days on Broadway, and her eyes are still piercing and inviting. She sips from a metal cup. The wind blows the flowers behind her until those flowers crane their stems toward her face, and the petals tilt upward, forcing out a smile. A dog barks in the background. In the best part of the clip, Kitt throws her head back and feigns a large, sky-rattling laugh upon being asked by her interviewer whether or not she’d compromise parts of herself if a man came into her life. When the laugh dies down, Kitt insists on the same, rhetorical statement. “Compromise!?!?” she flings. “For what?” She repeats “For what?” until it grows more fierce, more unanswerable. Until it holds the very answer itself. On the hook to the song “Eartha,” Jamila Woods sings “I don’t want to compromise / can we make it through the night” and as an album, Legacy! Legacy! stakes itself on the uncompromising nature of its creator, and the histories honored within its many layers. There is a lot of talk about black people in America and lineage, and who will tell the stories of our ancestors and their ancestors and the ones before them. But there is significantly less talk about the actions taken to uphold that lineage in a country obsessed with forgetting. There are hands who built the corners of ourselves we love most, and it is good to shout something sweet at those hands from time to time. Woods, a Chicago-born poet, organizer, and consistent glory merchant, seeks to honor black people first, always. And so, Legacy! Legacy! A song for Zora! Zora, who gave so much to a culture before she died alone and longing. A song for Octavia and her huge and savage conscience! A song for Miles! One for Jean-Michel and one for my man Jimmy Baldwin! More than just giving the song titles the names of historical black and brown icons of literature, art, and music, Jamila Woods builds a sonic and lyrical monument to the various modes of how these icons tried to push beyond the margins a country had assigned to them. On “Sun Ra,” Woods sings “I just gotta get away from this earth, man / this marble was doomed from the start” and that type of dreaming and vision honors not only the legacy of Sun Ra, but the idea that there is a better future, and in it, there will still be black people. Jamila Woods has a voice and lyrical sensibility that transcends generations, and so it makes sense to have this lush and layered album that bounces seamlessly from one sonic aesthetic to another. This was the case on 2016’s HEAVN, which found Woods hopeful and exploratory, looking along the edges resilience and exhaustion for some measures of joy. Legacy! Legacy! is the logical conclusion to that looking. From the airy boom-bap of “Giovanni” to the psychedelic flourishes of “Sonia,” the instrument which ties the musical threads together is the ability of Woods to find her pockets in the waves of instrumentation, stretching syllables and vowels over the harmony of noise until each puzzle piece has a home. The whimsical and malleable nature of sonic delights also grants a path for collaborators to flourish: the sparkling flows of Nitty Scott on “Sonia” and Saba on “Basquiat,” or the bloom of Nico Segal’s horns on “Baldwin.” Soul music did not just appear in America, and soul does not just mean music. Rather, soul is what gold can be dug from the depths of ruin, and refashioned by those who have true vision. True soul lives in the pages of a worn novel that no one talks about anymore, or a painting that sits in a gallery for a while but then in an attic forever. Soul is all the things a country tries to force itself into forgetting. Soul is all of those things come back to claim what is theirs. Jamila Woods is a singular soul singer who, in voice, holds the rhetorical demand. The knowing that there is no compromise for someone with vision this endless. That the revolution must take many forms, and it sometimes starts with songs like these. Songs that feel like the sun on your face and the wind pushing flowers against your back while you kick your head to the heavens and laugh at how foolish the world seems.

Matana Roberts returns with the fourth chapter of her extraordinary Coin Coin series — a project that has deservedly garnered the highest praise and widespread critical acclaim for its fierce aesthetic originality and unflinching narrative power. The first three Coin Coin albums, issued from 2011-2015, charted diverse pathways of modern/avant composition — Roberts calls it “panoramic sound quilting”—and ranged sequentially from large band to sextet to solo, unified by Roberts’ archival and often deeply personal research into legacies of the American slave trade and ancestries of American identity/experience. Roberts also emphasizes non-male subjects and thematizes these other-gendered stories with a range of vocal and verbal techniques: singspeak, submerged glossolalic recitation, guttural cathartic howl, operatic voice, gentle lullaby, group chant, and the recuperation of various American folk traditionals and spirituals, whether surfacing in fragmentary fashion or as unabridged set-pieces. The root of this vocality comes from her dedication to the legacy of her main chosen instrument, the alto saxophone. On Coin Coin Chapter Four: Memphis, Roberts convened a new band, with New Yorkers Hannah Marcus (guitars, fiddle, accordion) and percussionist Ryan Sawyer (Thurston Moore, Nate Wooley, Cass McCombs) joined by Montréal bassist Nicolas Caloia (Ratchet Orchestra) and Montréal-Cairo composer/improviser Sam Shalabi (Land Of Kush, Dwarfs Of East Agouza) on guitar and oud, along with prolific trombonist Steve Swell and vibraphonist Ryan White as special guests. Memphis unspools as a continuous work of 21st century liberation music, oscillating between meditative incantatory explorations, raucous melodic themes, and unbridled free-improv suites, quoting archly and ecstatically from various folk traditions along the way. Led by Roberts’ conduction and unique graphic score practice, her consummate saxophone and clarinet playing, and punctuated by her singing and speaking various texts generated from her own historical research and diaristic writings, Coin Coin Chapter Four is a glorious and spellbinding new instalment in this projected twelve-part Gesamtkunstwerk. Says Roberts: “As an arts adventurer dealing w/ the medium of sound and its many contradictions I am most interested in endurance, perseverance, migration, liberation, libation, improvisation and the many layers of cognitive dissonance therein as it relates to my birth country’s history. I speak memory, I sing an american survival through horn, song, sadness, a sometimes gladness. I stand on the backs of many people, from so many different walks of life and difference, that never had a chance to express themselves as expressively as I have been given the privilege. In these sonic renderings, I celebrate the me, I celebrate the we, in all that it is now, and all that is yet to come or will be... Thanks for listening.” Matana Roberts: alto sax, clarinet, wordspeak, voice Hannah Marcus: electric guitar, nylon string guitar, fiddle, accordion, voice Sam Shalabi: electric guitar, oud, voice Nicolas Caloia: double bass, voice Ryan Sawyer: drumset, vibraphone, jaw harp, bells, voice GUESTS: Steve Swell: trombone, voice Ryan White: vibraphone Thierry Amar: voice Nadia Moss: voice Jessica Moss: voice Recorded at Break Glass studios in Montréal, Québec by Jace Lasek, assisted by Dave Smith Mixed at Thee Mighty Hotel2Tango in Montréal, Québec by Radwan Moumneh Mastered at Greymarket in Montréal, Québec by Harris Newman

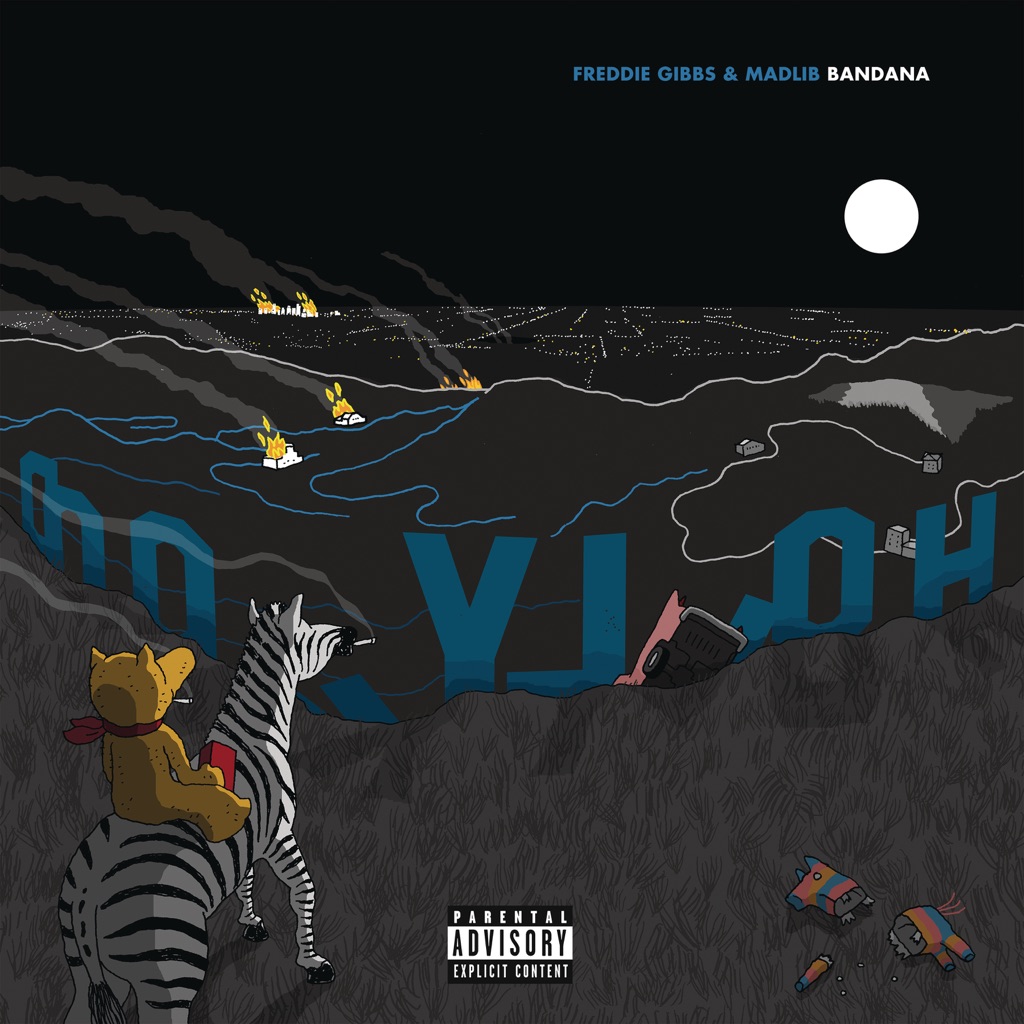

An eccentric like Madlib and a straightforward guy like Freddie Gibbs—how could it possibly work? If 2014’s *Piñata* proved that the pairing—offbeat producer, no-frills street rapper—sounded better and more natural than it looked on paper, *Bandana* proves *Piñata* wasn’t a fluke. The common ground is approachability: Even at their most cinematic (the noisy soul of “Flat Tummy Tea,” the horror-movie trap of “Half Manne Half Cocaine”), Madlib’s beats remain funny, strange, decidedly at human scale, while Gibbs prefers to keep things so real he barely uses metaphor. In other words, it’s remarkable music made by artists who never pretend to be anything other than ordinary. And even when the guest spots are good (Yasiin Bey and Black Thought on “Education” especially), the core of the album is the chemistry between Gibbs and Madlib: vivid, dreamy, serious, and just a little supernatural.

Rebirth takes place when everything falls apart. DIIV—Zachary Cole Smith [lead vocals, guitar], Andrew Bailey [guitar], Colin Caulfield [vocals, bass], and Ben Newman [drums]—craft the soundtrack to personal resurrection under the heavy weight of metallic catharsis upheld by robust guitars and vocal tension that almost snaps, but never quite… The same could be said of the journey these four musicians underwent to get to their third full-length album, Deceiver. Out of lies, fractured friendships, and broken promises, clarity would be found. “I’ve known everyone in the band for ten years plus separately and together as DIIV for at least the past five years,” says Cole. “On Deceiver, I’m talking about working for the relationships in my life, repairing them, and accepting responsibility for the places I’ve failed them. I had to re-approach the band. It wasn’t restarting from a clean slate, but it was a new beginning. It took time—as it did with everybody else in my life—but we all grew together and learned how to communicate and collaborate.” A whirlwind brought DIIV there. Amidst turmoil, the group delivered the critical and fan favorite Is the Is Are in 2016 following 2012’s Oshin. Praise came from The Guardian, Spin, and more. NME ranked it in the Top 10 among the “Albums of the Year.” Pitchfork’s audience voted Is the Is Are one of the “Top 50 Albums of 2016” as the outlet dubbed it, “gorgeous.” In the aftermath of Cole’s personal struggles, he “finally accepted what it means to go through treatment and committed,” emerging with a renewed focus and perspective. Getting back together with the band in Los Angeles would result in a series of firsts. This would be the first time DIIV conceived a record as a band with Colin bringing in demos, writing alongside Cole, and the entire band arranging every tune. “Cole and I approached writing vocal melodies the same way the band approached the instrumentals,” says Colin. “We threw ideas at the wall for months on end, slowly making sense of everything. It was a constant conversation about the parts we liked best versus which of them served the album best.” Another first, DIIV lived with the songs on the road. During a 2018 tour with Deafheaven, they performed eight untitled brand-new compositions as the bulk of the set. The tunes also progressed as the players did. “We went from playing these songs in the rehearsal space to performing them live at shows, figuring them out in real-time in front of hundreds of people, and approaching them from a broader range of reference points,” he goes on. “We’d never done that before. We got to internalize how everything worked on stage. We did all of the trimming before we went to the studio. It was an exercise in simplifying what makes a song. We really learned how to listen, write, and work as a band.” The vibe got heavier under influences ranging from Unwound and Elliot Smith to True Widow and Neurosis. They also enlisted producer Sonny Diperri [My Bloody Valentine, Nine Inch Nails, Protomartyr]. his presence dramatically expanded the sonic palette, making it richer and fuller than ever before. It marks a major step forward for DIIV. “He brought a lot of common sense and discipline to our process,” adds Cole. “We’d been touring these songs and playing them for a while, so he was able to encourage us to make decisions and own them.” The first single “Skin Game” charges forward with frenetic drums, layered vocals and clean, driven guitars that ricochet off each other. “I’d say it’s an imaginary dialogue between two characters, which could either be myself or people I know,” he says. “I spent six months in several different rehab facilities at the beginning of 2017. I was living with other addicts. Being a recovering addict myself, there are a lot of questions like, ‘Who are we? What is this disease?’ Our last record was about recovery in general, but I truthfully didn’t buy in. I decided to live in my disease instead. ‘Skin Game’ looks at where the pain comes from. I’m looking at the personal, physical, emotional, and broader political experiences feeding into the cycle of addiction for millions of us.” A trudging groove and wailing guitar punctuate a lulling apology on the magnetically melancholic “Taker.” According to Cole, it’s “about taking responsibility for your lies, their consequences, and the entire experience.” Meanwhile, the ominous bass line and crawling beat of “Blankenship” devolve into schizophrenic string bends as the vitriolic lyrics. Offering a dynamic denouement, the seven-minute “Acheron” flows through a hulking beat guided under gusts of lyrical fretwork and a distorted heavy apotheosis. Even after the final strains of distortion ring out on Deceiver, these four musicians will continue to evolve. “We’re still going,” Cole leaves off. “Hopefully we’ll be doing this for a long time.” Ultimately, DIIV’s rebirth is a hard-earned and well-deserved new beginning.

In their 25th year, German electro-industrial steamrollers Rammstein remain *der Goldstandard* for New German Hardness, with their mix of industrial sternness, techno hedonism, and metal aggression. Their seventh album lands somewhere between Faith No More and Franz Ferdinand, taut grooves meshing with bludgeoning riffs and disturbing stories. Lead single \"DEUTSCHLAND\" is scabrous, politically volatile doom-disco laying out conflicted feelings about living in their homeland, even tweaking the verse of the national anthem used in the country\'s fascist past. The rest follows the chug and bombast of albums like 2001\'s *Mutter* and 2009\'s *Liebe ist für alle da*: \"RADIO\" is like a heavy metal Kraftwerk, \"SEX\" is snaky glam-sludge, and \"PUPPE\" is a creeper with a coming-undone performance from lead singer Till Lindemann.

Michael Kiwanuka never seemed the type to self-title an album. He certainly wasn’t expected to double down on such apparent self-assurance by commissioning a kingly portrait of himself as the cover art. After all, this is the singer-songwriter who was invited to join Kanye West’s *Yeezus* sessions but eventually snuck wordlessly out, suffering impostor syndrome. That sense of self-doubt shadowed him even before his 2012 debut *Home Again* collected a Mercury Prize nomination. “It’s an irrational thought, but I’ve always had it,” he tells Apple Music. “It keeps you on your toes, but it was also frustrating me. I was like, ‘I just want to be able to do this without worrying so much and just be confident in who I am as an artist.’” Notions of identity also got him thinking about how performers create personas—onstage or on social media—that obscure their true selves, inspiring him to call his third album *KIWANUKA* in an act of what he calls “anti-alter-ego.” “It’s almost a statement to myself,” he says. “I want to be able to say, ‘This is me, rain or shine.’ People might like it, people might not, it’s OK. At least people know who I am.” Kiwanuka was already known as a gifted singer and songwriter, but *KIWANUKA* reveals new standards of invention and ambition. With Danger Mouse and UK producer Inflo behind the boards—as they were on *Love & Hate* in 2016—these songs push his barrel-aged blend of soul and folk further into psychedelia, fuzz rock, and chamber pop. Here, he takes us through that journey song by song. **You Ain’t the Problem** “‘You Ain’t the Problem’ is a celebration, me loving humans. We forget how amazing we are. Social media’s part of this—all these filters hiding things that we think people won\'t like, things we think don\'t quite fit in. You start thinking this stuff about you is wrong and that you’ve got a problem being whatever you are and who you were born to be. I wanted to write a song saying, ‘You’re not the problem. You just have to continue being *you* more, go deeper within yourself.’ That’s where the magic comes—as opposed to cutting things away and trying to erode what really makes you.” **Rolling** “‘Rolling with the times, don’t be late.’ Everything’s about being an artist for me, I guess. I was trying to find my place still, but you can do things to make sure that you fit in or are keeping up with everything that’s happening—whether it’s posting stuff online or keeping up with the coolest records, knowing the right things. Or it could just be you’re in your mid-thirties, you haven’t got married or had kids yet, and people are like, ‘What?’ ‘Rolling with the times’ is like, go at your own pace. In my head, there was early Stooges records and French records like Serge Gainsbourg with the fuzz sounds. I wanted to make a song that sounded kind of crazy like that.” **I’ve Been Dazed** “Eddie Hazel from Funkadelic is my favorite guitar player. This has anthemic chords because he would always have really beautiful anthemic chords in the songs that he wrote. It just came out almost hymn-like. Lyrically, because it has this melancholy feel to it, I was singing about waking up from the nightmare of following someone else’s path or putting yourself down, low self-esteem—the things ‘You Ain\'t the Problem’ is defying. The feeling is, ‘Man, I\'ve been in this kind of nightmare, I just want to get out of it, I’m ready to go.’” **Piano Joint (This Kind of Love) \[Intro\]** “As a teenager, I’d just escape \[into some albums\], like I could teleport away from life and into that person’s world. I really wanted to have that feel with this record. It would be so vivid, there was no chance to get out of it, no gap in the songs—make it feel like one long piece. Some songs just flow into each other, but some needed interludes as passageways. This intro came when I was playing some bass and \[Inflo\] was playing some piano and I started singing my idea of a Marvin Gaye soul tune—a deep, dark, melancholic cut from one of his ’70s records. Then Danger Mouse had the idea, ‘Why don’t you pitch some of it down so it sounds different?’” **Piano Joint (This Kind of Love)** “I used to always love melancholy songs; the sadder it is, the happier I’d be afterwards. This was my moment to really exercise that part of me. Originally, it was going to be a piano ballad, and then I was like, ‘Why don’t we try playing some drums?’ Inflo’s a really good drummer, so I went in and played bass with him, and it sounded really good. I was thinking of that ’70s Gil Scott-Heron East Coast soul. Then we worked with this amazing string arranger, Rosie Danvers, who did almost all the strings on the last album. I said to her, ‘It’s my favorite song, just do something super beautiful.’ She just killed it.” **Another Human Being** “We were doing all the interludes and Danger Mouse had found loads of samples. This was a news report \[about the ’60s US civil rights sit-in protests\]. I remember thinking, ‘This sounds amazing, it goes into “Living in Denial” perfectly—it just changes that song.’ And, yeah, again, I’m ’70s-obsessed, but the ’60s and ’70s were so pivotal for young American black men and women, and it just gave a gravitas to the record. It goes to identity and something that resonates with me and my name and who I am. It gives me loads of confidence to continue to be myself.” **Living in Denial** “This is how me, Inflo, and Danger Mouse sound when we’re completely ourselves and properly linked together. No arguments, just let it happen, don’t think about it. I was trying to be a soul group—thinking of The Delfonics, The Isley Brothers, The Temptations, The Chambers Brothers. Again, the lyrics are that thing of seeking acceptance: You don’t need to seek it, just accept yourself and then whoever wants to hang with you will.” **Hero (Intro)** “‘Hero’ was the last song we completed. Once it started to sound good, I was sitting there with my acoustic, playing. We’d done the ‘Piano Joint’ intro and I was like, ‘Oh, we should pitch down this number as well and make it something that we really wouldn’t do with a straight rock ’n’ roll song.’” **Hero** “‘Hero’ was the hardest to come up with lyrics for. We had the music and melody for, like, two years. Any time I tried to touch it, I hated it—I couldn’t come up with anything. Then I was reading about Fred Hampton from the Black Panthers and I started thinking about all these people that get killed—or, like Hendrix, die an accidental death—who have so much to give or do so much in such a small time. I also love the thing where all these legends, Bowie and Bob Dylan, were creating larger-than-life personas that we were obsessed with. You didn’t really know who they were. That really made me sad, because I don’t disagree with it, but I know that’s not me. So, ‘Am I a hero?’ was also asking, ‘If I do that stuff, will I become this big artist that everyone respects?’—that ‘I’m not enough’ thing.” **Hard to Say Goodbye** “This is my love of Isaac Hayes and big orchestrations, lush strings, people like David Axelrod. Flo actually brought in this sample from a Nat King Cole song, just one chord, and we pitched it around, and then we replayed it with a 20-piece string orchestra packed into the studio. We had a double-bass cello, the whole works, and this really good piano player Kadeem \[Clarke\] who plays with Little Simz, and our friend Nathan \[Allen\] playing drums. That was pretty fun.” **Final Days** “At first, I didn’t know where this would fit on the record, like, ‘Man, this is cool, I just don’t *love*it.’ I wrote some lyrics and thought, ‘This is better, but it’s missing something.’ It always felt like space to me, so I said to Kennie \[Takahashi\], the engineer, ‘Are there any samples you can find of people in space?’ We found these astronauts about to crash, which is kind of dark, but it gave it this emotion it was missing. It gave me goosebumps. Later, we found out that it was a fake, some guys messing around in Italy in the ’60s for an art project or something.” **Interlude (Loving the People)** “‘Final Days’ was sounding amazing, but it needed to go somewhere else at the end. I had this melody on the Wurlitzer, and originally it was an instrumental bit that comes in for the end of ‘Final Days’ so that it ends somewhere completely different, like the spaceship’s landing at its destination. But I was like, ‘Let’s stretch it out. Let’s do more.’ Danger Mouse found this \[US congressman and civil rights leader\] John Lewis sample, and it sounded beautiful and moving over these chords, so we put it here.” **Solid Ground** “When everything gets stripped away—all the strings, all the sounds, all the interludes—I’m still just a dude that sits and plays a song on a guitar or piano. I felt like the album needed a glimpse of that. Rosie did a beautiful arrangement and then I finished it off—everyone was out somewhere, so I just played all the instruments, apart from drums and things like that. So, ‘Solid Ground’ is my little piece that I had from another place. Lyrically, it’s about finding the place where you feel comfortable.” **Light** “I just thought ‘Light’ was a nice dreamy piece to end the record with—a bit of light at the end of this massive journey. You end on this peaceful note, something positive. For me, light describes loads of things that are good—whether it’s obvious things like the light at the end of the tunnel or just a light feeling in my heart. The idea that the day’s coming—such a peaceful, exciting thing. We’re just always looking for it.” *All Apple Music subscribers using the latest version of Apple Music on iPhone, iPad, Mac, and Apple TV can listen to thousands of Dolby Atmos Music tracks using any headphones. When listening with compatible Apple or Beats headphones, Dolby Atmos Music will play back automatically when available for a song. For other headphones, go to Settings > Music > Audio and set the Dolby Atmos switch to “Always On.” You can also hear Dolby Atmos Music using the built-in speakers on compatible iPhones, iPads, MacBook Pros, and HomePods, or by connecting your Apple TV 4K to a compatible TV or AV receiver. Android is coming soon. AirPods, AirPods Pro, AirPods Max, BeatsX, Beats Solo3, Beats Studio3, Powerbeats3, Beats Flex, Powerbeats Pro, and Beats Solo Pro Works with iPhone 7 or later with the latest version of iOS; 12.9-inch iPad Pro (3rd generation or later), 11-inch iPad Pro, iPad (6th generation or later), iPad Air (3rd generation), and iPad mini (5th generation) with the latest version of iPadOS; and MacBook (2018 model and later).*

Maggie Rogers spent the first three years of her career retracing one chance encounter: In 2016, a video of her singing a song that moved Pharrell to tears during a master class at NYU went viral, earning her a record deal, magazine features, and headlining tours (watch it and you’ll understand). But the Maryland native, then 22, was still figuring out who she was, and this sudden flood of fame was a lot to bear. Determined to take control of her own narrative, she assembled a debut album powerful enough to shift the conversation. Measured, subtle, and wise beyond her years, it feels like the introduction she always wanted to make. Like her 2017 EP, *Now That the Light Is Fading*, *Heard It In A Past Life* is a thoughtfully sewn patchwork of anthemic synth-pop, brooding acoustic folk, and soft-lit electronica, the latter of which was inspired by a year spent dancing through Berlin’s nightclub scene. But here, her vision feels both more daring and more polished. On “Retrograde,” long stretches of propulsive synths are punctuated by high-pitched *hah-hah-hah*s; “Say It” blends R&B with light, breathy indie-pop; and “The Knife” could be a sultry come-on or a daring confession. On the Greg Kurstin-produced “Light On,” Rogers seems to make peace with her surreal story. “And I am findin’ out/There’s just no other way/And I’m still dancin’ at the end of the day,” she sings, a bittersweet hat-tip to the moment that got her here. And to her fans, a promise: “If you leave the light on/Then I’ll leave the light on.”