FLOOD's Best Albums of 2023

From rap to pop to R&B to punk, this year was defined by a lack of homogeneity.

Source

You’ll be hard-pressed to find a description of boygenius that doesn’t contain the word “supergroup,” but it somehow doesn’t quite sit right. Blame decades of hoary prog-rock baggage, blame the misbegotten notion that bigger and more must be better, blame a culture that is rightfully circumspect about anything that feels like overpromising, blame Chickenfoot and Audioslave. But the sentiment certainly fits: Teaming three generational talents at the height of their powers on a project that is somehow more than the sum of its considerable parts sounds like it was dreamed up in a boardroom, but would never work if it had been. In fall 2018, Phoebe Bridgers, Lucy Dacus, and Julien Baker released a self-titled six-song EP as boygenius that felt a bit like a lark—three of indie’s brightest, most charismatic artists at their loosest. Since then, each has released a career-peak album (*Punisher*, *Home Video*, and *Little Oblivions*, respectively) that transcended whatever indie means now and placed them in the pantheon of American songwriters, full stop. These parallel concurrent experiences raise the stakes of a kinship and a friendship; only the other two could truly understand what each was going through, only the other two could mount any true creative challenge or inspiration. Stepping away from their ascendant solo paths to commit to this so fully is as much a musical statement as it is one about how they want to use this lightning-in-a-bottle moment. If *boygenius* was a lark, *the record* is a flex. Opening track “Without You Without Them” features all three voices harmonizing a cappella and feels like a statement of intent. While Bridgers’ profile may be demonstrably higher than Dacus’ or Baker’s, no one is out in front here or taking up extra oxygen; this is a proper three-headed hydra. It doesn’t sound like any of their own albums but does sound like an album only the three of them could make. Hallmarks of each’s songwriting style abound: There’s the slow-building climactic refrain of “Not Strong Enough” (“Always an angel, never a god”) which recalls the high drama of Baker’s “Sour Breath” and “Turn Out the Lights.” On “Emily I’m Sorry,” “Revolution 0,” and “Letter to an Old Poet,” Bridgers delivers characteristically devastating lines in a hushed voice that belies its venom. Dacus draws “Leonard Cohen” so dense with detail in less than two minutes that you feel like you’re on the road trip with her and her closest friends, so lost in one another that you don’t mind missing your exit. As with the EP, most songs feature one of the three taking the lead, but *the record* is at its most fully realized when they play off each other, trading verses and ideas within the same song. The subdued, acoustic “Cool About It” offers three different takes on having to see an ex; “Not Strong Enough” is breezy power-pop that serves as a repudiation of Sheryl Crow’s confidence (“I’m not strong enough to be your man”). “Satanist” is the heaviest song on the album, sonically, if not emotionally; over a riff with solid Toadies “Possum Kingdom” vibes, Baker, Bridgers, and Dacus take turns singing the praises of satanism, anarchy, and nihilism, and it’s just fun. Despite a long tradition of high-wattage full-length star team-ups in pop history, there’s no real analogue for what boygenius pulls off here. The closest might be Crosby, Stills & Nash—the EP’s couchbound cover photo is a wink to their 1969 debut—but that name doesn’t exactly evoke feelings of friendship and fellowship more than 50 years later. (It does, however, evoke that time Bridgers called David Crosby a “little bitch” on Twitter after he chastised her for smashing her guitar on *SNL*.) Their genuine closeness is deeply relatable, but their chemistry and talent simply aren’t. It’s nearly impossible for a collaboration like this to not feel cynical or calculated or tossed off for laughs. If three established artists excelling at what they are great at, together, without sacrificing a single bit of themselves, were so easy to do, more would try.

Like it did for listeners, Polly Jean Harvey’s 10th album came to her by surprise. “I\'d come off tour after \[2016’s\] *Hope Six Demolition Project*, and I was taking some time where I was just reassessing everything,” she tells Apple Music of what would become a seven-year break between records, during which it was rumored the iconic singer-songwriter might retire altogether. “Maybe something that we all do in our early fifties, but I\'d really wanted to see if I still felt I was doing the best that I could be with my life. Not wanting to sound doom-laden, but at 50, you do start thinking about a finite amount of time and maximizing what you do with that. I wanted to see what arose in me, see where I felt I needed to go with this last chapter of my life.” Harvey turned her attention to soundtrack work and poetry. In 2022, she published *Orlam*, a magical realist novel-in-verse set in the western English countryside where she grew up, written in a rare regional dialect. To stay sharp, she’d make time to practice scales on piano and guitar, to dig into theory. “Then I just started,” she says. “Melodies would arise, and instead of making up vowel sounds and consonant sounds, I\'d just pull at some of the poems. I wasn\'t trying to write a song, but then I had all these poems everywhere, overflowing out of my brain and on tables everywhere, bits of paper and drawings. Everything got mixed up together.” Written over the course of three weeks—one song a day—*I Inside the Old Year Dying* combines Harvey’s latest disciplines, lacing 12 of *Orlam*’s poems through similarly dreamy and atmospheric backdrops. The language is obscure but evocative, the arrangements (longtime collaborators Flood and John Parish produced) often vaporous and spare. But the feeling in her voice (especially on the title track and opener “Prayer at the Gate”) is inescapable. “I stopped thinking about songs in terms of traditional song structure or having to meet certain expectations, and I viewed them like I do the freedom of soundtrack work—it was just to create the right emotional underscore to the scene,” she says. “It was almost like the songs were just there, really wanting to come out. It fell out of me very easily. I felt a lot freer as a writer—from this album and hopefully onwards from now.”

Young Fathers occupy a unique place in British music. The Mercury Prize-winning trio are as adept at envelope-pushing sonic experimentalism and opaque lyrical impressionism as they are at soulful pop hooks and festival-primed choruses—frequently, in the space of the same song. Coming off the back of an extended hiatus following 2018’s acclaimed *Cocoa Sugar*, the Edinburgh threesome entered their basement studio with no grand plan for their fourth studio album other than to reconnect to the creative process, and each other. Little was explicitly discussed. Instead, Alloysious Massaquoi, Kayus Bankole, and Graham “G” Hastings—all friends since their school days—intuitively reacted to a lyric, a piece of music, or a beat that one of them had conceived to create multifaceted pieces of work that, for all their complexities and contradictions, hit home with soul-lifting, often spiritual, directness. Through the joyous clatter of opener “Rice,” the electro-glam battle cry “I Saw,” the epic “Tell Somebody,” and the shape-shifting sonic explosion of closer “Be Your Lady,” Young Fathers express every peak and trough of the human condition within often-dense tapestries of sounds and words. “Each song serves an integral purpose to create something that feels cohesive,” says Bankole. “You can find joy in silence, you can find happiness in pain. You can find all these intricate feelings and diverse feelings that reflect reality in the best possible way within these songs.” Across 10 dazzling tracks, *Heavy Heavy* has all that and more, making it the band’s most fully realized and affecting work to date. Let Massaquoi and Bankole guide you through it, track by track. **“Rice”** Alloysious Massaquoi: “What we’re great at doing is attaching ourselves to what the feeling of the track is and then building from that, so the lyrics start to come from that point of view. \[On ‘Rice’\] that feeling of it being joyous was what we were connecting to. It was the feeling of fresh morning air. You’re on a journey, you’re moving towards something, it feels like you’re coming home to find it again. For me, it was finding that feeling of, ‘OK, I love music again,’ because during COVID it felt redundant to me. What mattered to me was looking after my family.” **“I Saw”** AM: “We’d been talking about Brexit, colonialism, about forgetting the contributions of other countries and nations so that was in the air. And when we attached ourselves to the feeling of the song, it had that call-to-arms feeling to it, it’s like a march.” Kayus Bankole: “It touches on Brexit, but it also touches on how effective turning a blind eye can be, that idea that there’s nothing really you can do. It’s a call to arms, but there’s also this massive question mark. I get super-buzzed by leaving question marks so you can engage in some form of conversation afterwards.” **“Drum”** AM: “It’s got that sort of gospel spiritual aspect to it. There’s an intensity in that. It’s almost like a sermon is happening.” KB: “The intensity of it is like a possession. A good, spiritual thing. For me, speaking in my native tongue \[Yoruba\] is like channeling a part of me that the Western world can’t express. I sometimes feel like the English language fails me, and in the Western world not a lot of people speak my language or understand what I’m saying, so it’s connecting to my true self and expressing myself in a true way.” **“Tell Somebody”** AM: “It was so big, so epic that we just needed to be direct. The lyrics had to be relatable. It’s about having that balance. You have to really boil it down and think, ‘What is it I’m trying to say here?’ You have 20 lines and you cut it down to just five and that’s what makes it powerful. I think it might mean something different to everyone in the group, but I know what it means to me, through my experiences, and that’s what I was channeling. The more you lean into yourself, the more relatable it is.” **“Geronimo”** AM: “It’s talking about relationships: ‘Being a son, brother, uncle, father figure/I gotta survive and provide/My mama said, “You’ll never ever please your woman/But you’ll have a good time trying.”’ It’s relatable again, but then you have this nihilistic cynicism from Graham: ‘Nobody goes anywhere really/Dressed up just to go in the dirt.’ It’s a bit nihilistic, but given the reality of the world and how things are, I think you need the balance of those things. Jump on, jump off. It’s like: *decide*. You’re either hot or you’re cold. Don’t be lukewarm. You either go for it or you don’t. Then encapsulating all that within Geronimo, this Native American hero.” **“Shoot Me Down”** AM: “‘Shoot Me Down’ is definitely steeped in humanity. You’ve got everything in there. You’ve got the insecurities, the cynicism, you’ve got the joy, the pain, the indifference. You’ve got all those things churning around in this cauldron. There’s a level of regret in there as well. Again, when you lean into yourself, it becomes more relatable to everybody else.” **“Ululation”** KB: “It’s the first time we’ve ever used anyone else on a track. A really close friend of mine, who I call a sister, called me while we were making ‘Uluation’: ‘I need a place to stay, I’m having a difficult time with my husband, I’m really angry at him…’ I said if you need a place to chill just come down to the studio and listen to us while we work but you mustn’t say a word because we’re working. We’re working on the track and she started humming in the background. Alloy picked up on it and was like, ‘Give her a mic!’ She’s singing about gratitude. In the midst of feeling very angry, feeling like shit and that life’s not fair, she still had that emotion that she can practice gratitude. I think that’s a beautiful contrast of emotions.” **“Sink Or Swim”** AM: “It says a similar thing to what we’re saying on ‘Geronimo’ but with more panache. The music has that feeling of a carousel, you’re jumping on and jumping off. If you watch Steve McQueen’s Small Axe \[film anthology\], in *Lovers Rock*, when they’re in the house party before the fire starts—this fits perfectly to that. It’s that intensity, the sweat and the smoke, but with these direct lines thrown in: ‘Oh baby, won’t you let me in?’ and ‘Don’t always have to be so deep.’ Sometimes you need a bit of directness, you need to call a spade a spade.” **“Holy Moly”** AM: “It’s a contrast between light and dark. You’re forcing two things that don’t make sense together. You have a pop song and some weird beat, and you’re forcing them to have this conversation, to do something, and then ‘Holy Moly’ comes out of that. It’s two different worlds coming together and what cements it is the lyrics.” **“Be Your Lady”** KB: “It’s the perfect loop back to the first track so you could stay in the loop of the album for decades, centuries, and millenniums and just bask in these intricate parts. ‘Be Your Lady’ is a nice wave goodbye, but it’s also radical as fuck. That last line ‘Can I take 10 pounds’ worth of loving out of the bank please?’ I’m repeating it and I’m switching the accents of it as well because I switch accents in conversation. I sometimes speak like someone who’s from Washington, D.C. \[where Bankole has previously lived\], or someone who’s lived in the Southside of Edinburgh, and I sometimes speak like someone who’s from Lagos in Nigeria.” AM: “I wasn’t convinced about that track initially. I was like, ‘What the fuck is this?’” KB: “That’s good, though. That’s the feeling that you want. That’s why I feel it’s radical. It’s something that only we can do, it comes together and it feels right.”

WIN ACCESS TO A SOUNDCHECK AND TICKETS TO A UK HEADLINE SHOW OF YOUR CHOOSING BY PRE-ORDERING* ANY ALBUM FORMAT OF 'HEAVY HEAVY' BY 6PM GMT ON TUESDAY 31ST JANUARY. PREVIOUS ORDERS WILL BE COUNTED AS ENTRIES. OPEN TO UK PURCHASES ONLY. FAQ young-fathers.com/comp/faq Young Fathers - Alloysious Massaquoi, Kayus Bankole and G. Hastings - announce details of their brand new album Heavy Heavy. Set for release on February 3rd 2023 via Ninja Tune, it’s the group’s fourth album and their first since 2018’s album Cocoa Sugar. The 10-track project signals a renewed back-to-basics approach, just the three of them in their basement studio, some equipment and microphones: everything always plugged in, everything always in reach. Alongside the announcement ‘Heavy Heavy’, Young Fathers will make their much anticipated return to stages across the UK and Europe beginning February 2023 - known for their electrifying performances, their shows are a blur of ritualistic frenzy, marking them as one of the most must-see acts operating today. The tour will include shows at the Roundhouse in London, Elysee Montmartre in Paris, Paradiso in Amsterdam, O2 Academy in Leeds and Glasgow, Olympia in Dublin, Astra in Berlin, Albert Hall in Manchester, Trix in Antwerp, Mojo Club in Hamburg and more (full dates below) To mark news of the album and the tour, Young Fathers today release a brand new single, “I Saw”. It’s the second track to be released from the album (following standalone single “Geronimo” in July) and brims with everything fans have come to love from a group known for their multi-genre versatility - kinetic rhythms, controlled chaos and unbridled soul. Accompanied by a video created by 23 year old Austrian-Nigerian artist and filmmaker David Uzochukwu, the track demonstrates the ambitious ideas that lay at the heart of this highly-anticipated record. Speaking about the title, the band write that Heavy Heavy could be a mood, or it could describe the smoothed granite of bass that supports the sound… or it could be a nod to the natural progression of boys to grown men and the inevitable toll of living, a joyous burden, relationships, family, the natural momentum of a group that has been around long enough to witness massive changes. “You let the demons out and deal with it,” reckons Kayus of the album. “Make sense of it after.” For Young Fathers, there’s no dress code required. Dancing, not moshing. Hips jerking, feet slipping, brain firing in Catherine Wheel sparks of joy and empathy. Underground but never dark. Still young, after some years, even as the heavy, heavy weight of the world seems to grow day by day.

“You can feel a lot of motion and energy,” Caroline Polachek tells Apple Music of her second solo studio album. “And chaos. I definitely leaned into that chaos.” Written and recorded during a pandemic and in stolen moments while Polachek toured with Dua Lipa in 2022, *Desire, I Want to Turn Into You* is Polachek’s self-described “maximalist” album, and it weaponizes everything in her kaleidoscopic arsenal. “I set out with an interest in making a more uptempo record,” she says. “Songs like ‘Bunny Is a Rider,’ ‘Welcome to My Island,’ and ‘Smoke’ came onto the plate first and felt more hot-blooded and urgent than anything I’d done before. But of course, life happened, the pandemic happened, I evolved as a person, and I can’t really deny that a lunar, wistful side of my writing can never be kept out of the house. So it ended up being quite a wide constellation of songs.” Polachek cites artists including Massive Attack, SOPHIE, Donna Lewis, Enya, Madonna, The Beach Boys, Timbaland, Suzanne Vega, Ennio Morricone, and Matia Bazar as inspirations, but this broad church only really hints at *Desire…*’s palette. Across its 12 songs we get trip-hop, bagpipes, Spanish guitars, psychedelic folk, ’60s reverb, spoken word, breakbeats, a children’s choir, and actual Dido—all anchored by Polachek’s unteachable way around a hook and disregard for low-hanging pop hits. This is imperial-era Caroline Polachek. “The album’s medium is feeling,” she says. “It’s about character and movement and dynamics, while dealing with catharsis and vitality. It refuses literal interpretation on purpose.” Read on for Polachek’s track-by-track guide. **“Welcome to My Island”** “‘Welcome to My Island’ was the first song written on this album. And it definitely sets the tone. The opening, which is this minute-long non-lyrical wail, came out of a feeling of a frustration with the tidiness of lyrics and wanting to just express something kind of more primal and urgent. The song is also very funny. We snap right down from that Tarzan moment down to this bitchy, bratty spoken verse that really becomes the main personality of this song. It’s really about ego at its core—about being trapped in your own head and forcing everyone else in there with you, rather than capitulating or compromising. In that sense, it\'s both commanding and totally pathetic. The bridge addresses my father \[James Polachek died in 2020 from COVID-19\], who never really approved of my music. He wanted me to be making stuff that was more political, intellectual, and radical. But also, at the same time, he wasn’t good at living his own life. The song establishes that there is a recognition of my own stupidity and flaws on this album, that it’s funny and also that we\'re not holding back at all—we’re going in at a hundred percent.” **“Pretty in Possible”** “If ‘Welcome to My Island’ is the insane overture, ‘Pretty in Possible’ finds me at street level, just daydreaming. I wanted to do something with as little structure as possible where you just enter a song vocally and just flow and there\'s no discernible verses or choruses. It’s actually a surprisingly difficult memo to stick to because it\'s so easy to get into these little patterns and want to bring them back. I managed to refuse the repetition of stuff—except for, of course, the opening vocals, which are a nod to Suzanne Vega, definitely. It’s my favorite song on the album, mostly because I got to be so free inside of it. It’s a very simple song, outside a beautiful string section inspired by Massive Attack’s ‘Unfinished Sympathy.’ Those dark, dense strings give this song a sadness and depth that come out of nowhere. These orchestral swells at the end of songs became a compositional motif on the album.” **“Bunny Is a Rider”** “A spicy little summer song about being unavailable, which includes my favorite bassline of the album—this quite minimal funk bassline. Structurally on this one, I really wanted it to flow without people having a sense of the traditional dynamics between verses and choruses. Timbaland was a massive influence on that song—especially around how the beat essentially doesn\'t change the whole song. You just enter it and flow. ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ was a set of words that just flowed out without me thinking too much about it. And the next thing I know, we made ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ thongs. I love getting occasional Instagram tags of people in their ‘Bunny Is a Rider’ thongs. An endless source of happiness for me.” **“Sunset”** “This was a song I began writing with Sega Bodega in 2020. It sounded completely nothing like the others. It had a folk feel, it was gypsy Spanish, Italian, Greek feel to it. It completely made me look at the album differently—and start to see a visual world for them that was a bit more folk, but living very much in the swirl of city life, having this connection to a secret, underground level of antiquity and the universalities of art. It was written right around a month or two after Ennio Morricone passed away, so I\'d been thinking a lot about this epic tone of his work, and about how sunsets are the biggest film clichés in spaghetti westerns. We were laughing about how it felt really flamenco and Spanish—not knowing that a few months later, I was going to find myself kicked out of the UK because I\'d overstayed my visa without realizing it, and so I moved my sessions with Sega to Barcelona. It felt like the song had been a bit of a premonition that that chapter-writing was going to happen. We ended up getting this incredible Spanish guitarist, Marc Lopez, to play the part.” **“Crude Drawing of an Angel”** “‘Crude Drawing of an Angel’ was born, in some ways, out of me thinking about jokingly having invented the word ‘scorny’—which is scary and horny at the same time. I have a playlist of scorny music that I\'m still working on and I realized that it was a tone that I\'d never actually explored. I was also reading John Berger\'s book on drawing \[2005’s *Berger on Drawing*\] and thinking about trace-leaving as a form of drawing, and as an extremely beautiful way of looking at sensuality. This song is set in a hotel room in which the word ‘drawing’ takes on six different meanings. It imagines watching someone wake up, not realizing they\'re being observed, whilst drawing them, knowing that\'s probably the last time you\'re going to see them.” **“I Believe”** “‘I Believe’ is a real dedication to a tone. I was in Italy midway through the pandemic and heard this song called ‘Ti Sento’ by Matia Bazar at a house party that blew my mind. It was the way she was singing that blew me away—that she was pushing her voice absolutely to the limit, and underneath were these incredible key changes where every chorus would completely catch you off guard. But she would kind of propel herself right through the center of it. And it got me thinking about the archetype of the diva vocally—about how really it\'s very womanly that it’s a woman\'s voice and not a girl\'s voice. That there’s a sense of authority and a sense of passion and also an acknowledgment of either your power to heal or your power to destroy. At the same time, I was processing the loss of my friend SOPHIE and was thinking about her actually as a form of diva archetype; a lot of our shared taste in music, especially ’80s music, kind of lined up with a lot of those attitudes. So I wanted to dedicate these lyrics to her.” **“Fly to You” (feat. Grimes and Dido)** “A very simple song at its core. It\'s about this sense of resolution that can come with finally seeing someone after being separated from them for a while. And when a lot of misunderstanding and distrust can seep in with that distance, the kind of miraculous feeling of clearing that murk to find that sort of miraculous resolution and clarity. And so in this song, Grimes, Dido, and I kind of find our different version of that. But more so than anything literal, this song is really about beauty, I think, about all of us just leaning into this kind of euphoric, forward-flowing movement in our singing and flying over these crystalline tiny drum and bass breaks that are accompanied by these big Ibiza guitar solos and kind of Nintendo flutes, and finding this place where very detailed electronic music and very pure singing can meet in the middle. And I think it\'s something that, it\'s a kind of feeling that all of us have done different versions of in our music and now we get to together.” **“Blood and Butter”** “This was written as a bit of a challenge between me and Danny L Harle where we tried to contain an entire song to two chords, which of course we do fail at, but only just. It’s a pastoral, it\'s a psychedelic folk song. It imagines itself set in England in the summer, in June. It\'s also a love letter to a lot of the music I listened to growing up—these very trance-like, mantra-like songs, like Donna Lewis’ ‘I Love You Always Forever,’ a lot of Madonna’s *Ray of Light* album, Savage Garden—that really pulsing, tantric electronic music that has a quite sweet and folksy edge to it. The solo is played by a hugely talented and brilliant bagpipe player named Brighde Chaimbeul, whose album *The Reeling* I\'d found in 2022 and became quite obsessed with.” **“Hopedrunk Everasking”** “I couldn\'t really decide if this song needed to be about death or about being deeply, deeply in love. I then had this revelation around the idea of tunneling, this idea of retreating into the tunnel, which I think I feel sometimes when I\'m very deeply in love. The feeling of wanting to retreat from the rest of the world and block the whole rest of the world out just to be around someone and go into this place that only they and I know. And then simultaneously in my very few relationships with losing someone, I did feel some this sense of retreat, of someone going into their own body and away from the world. And the song feels so deeply primal to me. The melody and chords of it were written with Danny L Harle, ironically during the Dua Lipa tour—when I had never been in more of a pop atmosphere in my entire life.” **“Butterfly Net”** “‘Butterfly Net’ is maybe the most narrative storyteller moment on the whole album. And also, palette-wise, deviates from the more hybrid electronic palette that we\'ve been in to go fully into this 1960s drum reverb band atmosphere. I\'m playing an organ solo. I was listening to a lot of ’60s Italian music, and the way they use reverbs as a holder of the voice and space and very minimal arrangements to such incredible effect. It\'s set in three parts, which was somewhat inspired by this triptych of songs called ‘Chansons de Bilitis’ by Claude Debussy that I had learned to sing with my opera teacher. I really liked that structure of the finding someone falling in love, the deepening of it, and then the tragedy at the end. It uses the metaphor of the butterfly net to speak about the inability to keep memories, to keep love, to keep the feeling of someone\'s presence. The children\'s choir \[London\'s Trinity Choir\] we hear on ‘Billions’ comes in again—they get their beautiful feature at the end where their voices actually become the stand-in for the light of the world being onto me.” **“Smoke”** “It was, most importantly, the first song for the album written with a breakbeat, which inspired me to carry on down that path. It’s about catharsis. The opening line is about pretending that something isn\'t catastrophic when it obviously is. It\'s about denial. It\'s about pretending that the situation or your feelings for someone aren\'t tectonic, but of course they are. And then, of course, in the chorus, everything pours right out. But tonally it feels like I\'m at home base with ‘Smoke.’ It has links to songs like \[2019’s\] ‘Pang,’ which, for me, have this windswept feeling of being quite out of control, but are also very soulful and carried by the music. We\'re getting a much more nocturnal, clattery, chaotic picture.” **“Billions”** “‘Billions’ is last for all the same reasons that \'Welcome to My Island’ is first. It dissolves into total selflessness, whereas the album opens with total selfishness. The Beach Boys’ ‘Surf’s Up’ is one of my favorite songs of all time. I cannot listen to it without sobbing. But the nonlinear, spiritual, tumbling, open quality of that song was something that I wanted to bring into the song. But \'Billions\' is really about pure sensuality, about all agenda falling away and just the gorgeous sensuality of existing in this world that\'s so full of abundance, and so full of contradictions, humor, and eroticism. It’s a cheeky sailboat trip through all these feelings. You know that feeling of when you\'re driving a car to the beach, that first moment when you turn the corner and see the ocean spreading out in front of you? That\'s what I wanted the ending of this album to feel like: The song goes very quiet all of a sudden, and then you see the water and the children\'s choir comes in.”

A Wednesday song is a quilt. A short story collection, a half-memory, a patchwork of portraits of the American south, disparate moments that somehow make sense as a whole. Karly Hartzman, the songwriter/vocalist/guitarist at the helm of the project, is a story collector as much as she is a storyteller: a scholar of people and one-liners. Rat Saw God, the Asheville quintet’s new and best record, is ekphrastic but autobiographical and above all, deeply empathetic. Across the album’s ten tracks Hartzman, guitarist MJ Lenderman, bassist Margo Shultz, drummer Alan Miller, and lap/pedal steel player Xandy Chelmis build a shrine to minutiae. Half-funny, half-tragic dispatches from North Carolina unfurling somewhere between the wailing skuzz of Nineties shoegaze and classic country twang, that distorted lap steel and Hartzman’s voice slicing through the din. Rat Saw God is an album about riding a bike down a suburban stretch in Greensboro while listening to My Bloody Valentine for the first time on an iPod Nano, past a creek that runs through the neighborhood riddled with broken glass bottles and condoms, a front yard filled with broken and rusted car parts, a lonely and dilapidated house reclaimed by kudzu. Four Lokos and rodeo clowns and a kid who burns down a corn field. Roadside monuments, church marquees, poppers and vodka in a plastic water bottle, the shit you get away with at Jewish summer camp, strange sentimental family heirlooms at the thrift stores. The way the South hums alive all night in the summers and into fall, the sound of high school football games, the halo effect from the lights polluting the darkness. It’s not really bright enough to see in front of you, but in that stretch of inky void – somehow – you see everything. Rat Saw God was written in the months immediately following Twin Plagues’ completion, and recorded in a week at Asheville’s Drop of Sun studio. While Twin Plagues was a breakthrough release critically for Wednesday, it was also a creative and personal breakthrough for Hartzman. The lauded record charts feeling really fucked up, trauma, dropping acid. It had Hartzman thinking about the listener, about her mom hearing those songs, about how it feels to really spill your guts. And in the end, it felt okay. “I really jumped that hurdle with Twin Plagues where I was not worrying at all really about being vulnerable – I was finally comfortable with it, and I really wanna stay in that zone.” The album opener, “Hot Rotten Grass Smell,” happens in a flash: an explosive and wailing wall-of-sound dissonance that’d sound at home on any ‘90s shoegaze album, then peters out into a chirping chorus of peepers, a nighttime sound. And then into the previously-released eight-and-half-minute sprawling, heavy single, “Bull Believer.” Other tracks, like the creeping “What’s So Funny” or “Turkey Vultures,” interrogate Hartzman’s interiority - intimate portraits of coping, of helplessness. “Chosen to Deserve” is a true-blue love song complete with ripping guitar riffs, skewing classic country. “Bath County” recounts a trip Hartzman and her partner took to Dollywood, and time spent in the actual Bath County, Virginia, where she wrote the song while visiting, sitting on a front porch. And Rat Saw God closer “TV in the Gas Pump” is a proper traveling road song, written from one long ongoing iPhone note Hartzman kept while in the van, its final moments of audio a wink toward Twin Plagues. The reference-heavy stand-out “Quarry” is maybe the most obvious example of the way Hartzman seamlessly weaves together all these throughlines. It draws from imagery in Lynda Barry’s Cruddy; a collection of stories from Hartzman’s family (her dad burned down that cornfield); her current neighbors; and the West Virginia street from where her grandma lived, right next to a rock quarry, where the explosions would occasionally rock the neighborhood and everyone would just go on as normal. The songs on Rat Saw God don’t recount epics, just the everyday. They’re true, they’re real life, blurry and chaotic and strange – which is in-line with Hartzman’s own ethos: “Everyone’s story is worthy,” she says, plainly. “Literally every life story is worth writing down, because people are so fascinating.” But the thing about Rat Saw God - and about any Wednesday song, really - is you don’t necessarily even need all the references to get it, the weirdly specific elation of a song that really hits. Yeah, it’s all in the details – how fucked up you got or get, how you break a heart, how you fall in love, how you make yourself and others feel seen – but it’s mostly the way those tiny moments add up into a song or album or a person.

“We have to be friends”—the first song written for *PARANOÏA, ANGELS, TRUE LOVE*—had a profound impact on its author. “I was like, ‘What the hell is going to be this record? This is going to be my awakening,” Chris tells Apple Music’s Proud Radio. “The song was all-knowing of something and admonishing me finally to stop being blind or something. So I started to take music even more seriously and more spiritually.” Even before that track, the French alt-pop talent had begun to embrace spirituality and prayer following the death of his mother in 2019—a loss that also colored much of 2022’s *Redcar les adorables étoiles (prologue)*. But letting it into his music took him to deeper places than ever before. “This journey of music has been very extreme because I wanted to devote myself and I went to extreme places that changed me forever,” adds Chris. “An awakening is just the beginning of a spiritual journey, so I wouldn\'t say I\'m there, it would be arrogant. But it\'s definitely the opening of a clear path of spirituality through music.” After the high-concept, operatic *Redcar*, this album—a three-part epic lasting almost two hours that’s rooted in (and whose name nods to) Tony Kushner’s 1991 play *Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes*, an exploration of AIDS in 1980s America—confirms our arrival into the most ambitious Christine and the Queens era yet. The songs here will demand more of you than the smart pop that made Christine and the Queens famous—but they will also richly reward your attention, with sprawling, synth-led outpourings that reveal something new with every listen. Here, Chris (who collaborated with talent including superproducer MIKE DEAN and 070 Shake) reaches for trip-hop (the Marvin Gaye-sampling “Tears can be so soft”), classical music (the sublime “Full of life,” which layers Chris’ reverbed vocals over the instantly recognizable Pachelbel’s Canon), ’80s-style drums (“We have to be friends”), and the kind of haunting, atmospheric ballads this artist excels at (“To be honest”). Oh, and the album’s narrator? Madonna. “I was like, ‘If Madonna was just like a stage character, it would be brilliant,’” says Chris. “I pitch it like fast, quite intensely: ‘I need you to be the voice of everything. You need to be this voice of, maybe it\'s my mom, maybe it\'s the Queen Mary, maybe it\'s a computer, maybe it\'s everything.’ And she was like, ‘You\'re crazy, I\'ll do it.’” Chris gave the narrator a name: Big Eye. “The whole thing was insane, which is the best thing,” he says. “The record itself solidified itself in maybe less than a month. I was writing a new song every day. It was quite consistent and a wild journey. And as I was singing the song, the character was surfacing in the words. I was like, ‘Oh, this is a character.’ Big Eye was the name I gave the character because it\'s this very all-encompassing, slightly worrying angel voice, could be dystopian.” For Chris, this album was a teacher and a healer—even a “shaman.” “I discovered so much more of myself and rediscovered why I loved music so hard,” he says. “And it\'s this great light journey of healing I adore.” It also cracked open his heart. “This record for me is a message of love,” he adds. “It comes from me, but it comes from the invisible as well. Honestly, I felt a bit cradled by extra strength. Even the collaboration I had, this whole journey was about friendship, finding meaning in pain too. It opened my heart.”

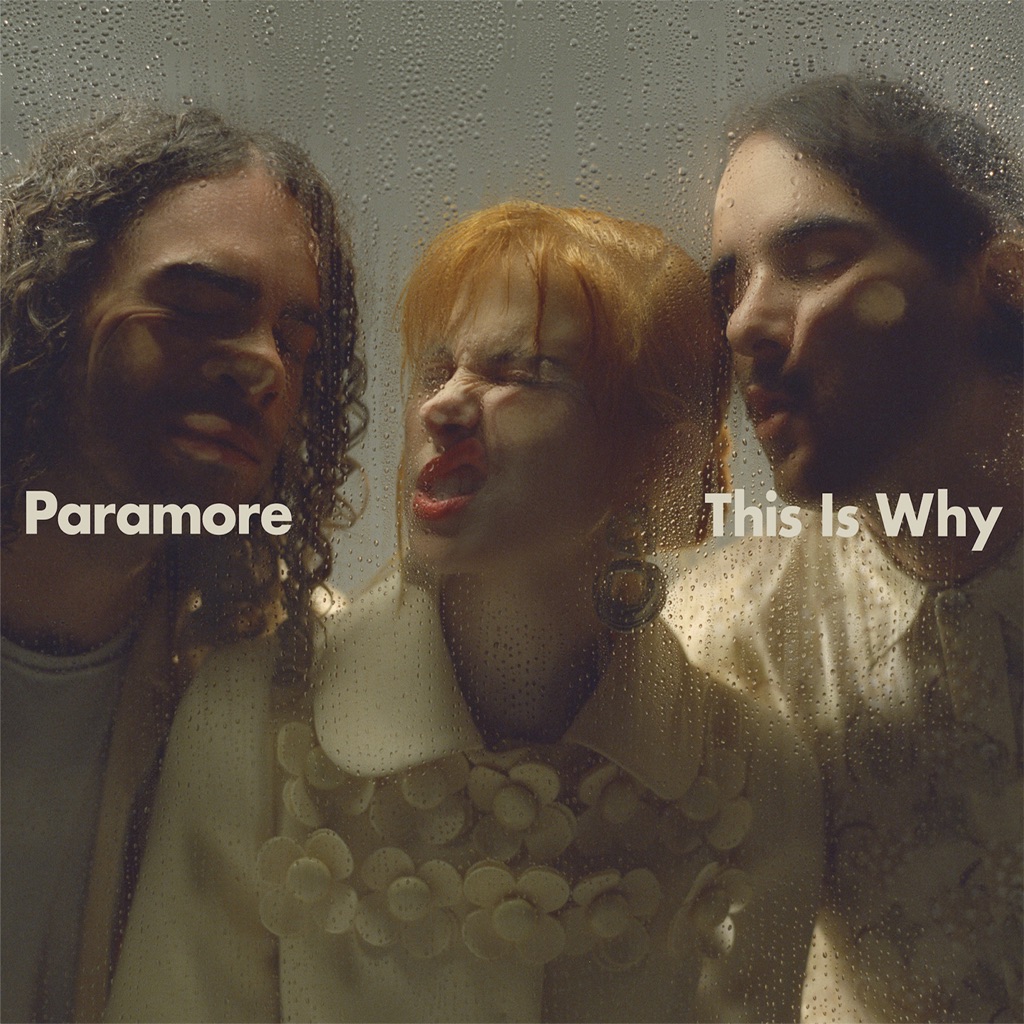

Few rock bands this side of Y2K have committed themselves to forward motion quite like Paramore. But in order to summon the aggression of their sixth full-length, the Tennessee outfit needed to look back—to draw on some of the same urgency that defined them early on, when they were teenaged upstarts slinging pop punk on the Warped Tour. “I think that\'s why this was a hard record to make,” Hayley Williams tells Apple Music of *This Is Why*. “Because how do you do that without putting the car in reverse completely?” In the neon wake of 2017’s *After Laughter*—an unabashed pop record—guitarist Taylor York says he found himself “really craving rock.” Add to that a combination of global pandemic, social unrest, apocalyptic weather, and war, and you have what feels like a suitable backdrop (if not cause) for music with edges. “I think figuring out a smarter way to make something aggressive isn\'t just turning up the distortion,” York says. “That’s where there was a lot of tension, us trying to collectively figure out what that looks like and can all three of us really get behind it and feel represented. It was really difficult sometimes, but when we listened back at the end, we were like, ‘Sick.’” What that looks like is a set of spiky but highly listenable (and often danceable) post-punk that draws influence from early-2000s revivalists like Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Bloc Party, The Rapture, Franz Ferdinand, and Hot Hot Heat. Throughout, Williams offers relatable glimpses of what it’s been like to live through the last few years, whether it’s feelings of anxiety (the title cut), outrage (“The News”), or atrophy (“C’est Comme Ça”). “I got to yell a lot on this record, and I was afraid of that, because I’ve been treating my voice so kindly and now I’m fucking smashing it to bits,” she says. “We finished the first day in the studio and listened back to the music and we were like, ‘Who is this?’ It simultaneously sounds like everything we\'ve ever loved and nothing that we\'ve ever done before ourselves. To me, that\'s always a great sign, because there\'s not many posts along the way that tell you where to go. You\'re just raw-dogging it. Into the abyss.”

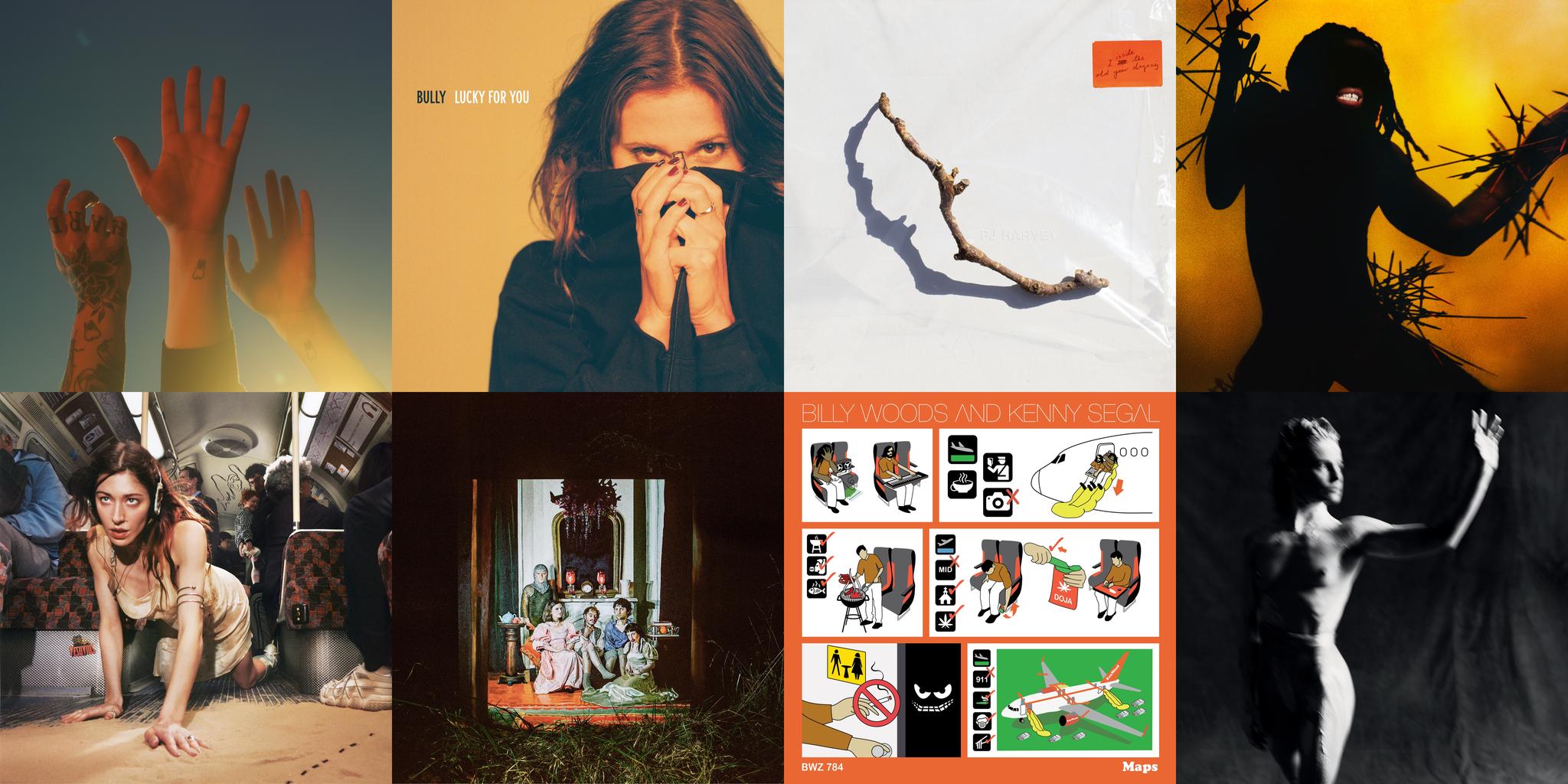

Like all great stylists, the artist born Sean Bowie has a gift for presenting sounds we know in ways we don’t. So, while the surfaces of *Praise a Lord…*, Yves Tumor’s fifth LP, might remind you of late-’90s and early-2000s electro-rock, the album’s twisting song structures and restless detail (the background panting of “God Is a Circle,” the industrial hip-hop of “Purified by the Fire,” and the houselike tilt of “Echolalia”) offer almost perpetual novelty all while staying comfortably inside the constraints of three-minute pop. Were the music more challenging, you’d call it subversive, and in the context of Bowie as a gender-nonconforming Black artist playing with white, glam-rock tropes, it is. But the real subversion is that they deliver you their weird art and it feels like pleasure.

Post-humanism was a passion and a coping mechanism on yeule’s breakthrough album, 2022’s *Glitch Princess*, art-pop that escaped into the simulation and drew raw emotion from its artifice. Their third full-length finds the shape-shifting musician regaining their bearings as a human being, and trading short-circuiting electronica for the fuzzy sounds of shoegaze and ‘90s alt-rock. The effect is that of an AI yearning to be flesh and blood: “If only I could be/Real enough to love,” they sing over downcast guitar chords on “ghosts” as their voice glitches into decay. On the bleakly gorgeous “software update,” yeule fantasizes about a lover downloading their mind after their body is gone, over a swelling, reverberating wall of sound. There’s a tactile quality to the album’s digital processing reminiscent of ‘90s Warp Records staples like Boards of Canada or Aphex Twin, shot through with the melancholy that accompanies nostalgia for a time that’s long gone and barely remembered.

For the last two decades, Sufjan Stevens’ music has taken on two distinct forms. On one end, you have the ornate, orchestral, and positively stuffed style that he’s excelled at since the conceptual fantasias of 2003’s star-making *Michigan*. On the other, there’s the sparse and close-to-the-bone narrative folk-pop songwriting that’s marked some of his most well-known singles and albums, first fully realized on the stark and revelatory *Seven Swans* from 2004. His 10th studio full-length, *Javelin*, represents the fullest and richest merging of those two approaches that Stevens has achieved to date. Even as it’s been billed as his first proper “songwriter’s album” since 2015’s autobiographical and devastating *Carrie & Lowell*, *Javelin* is a kaleidoscopic distillation of everything Stevens has achieved in his career so far, resulting in some of the most emotionally affecting and grandiose-sounding music he’s ever made. *Javelin* is Stevens’ first solo record of vocal-based music since 2020’s *The Ascension*, and it’s relatively straightforward compared to its predecessor’s complexity. Featuring contributions from vocalists and frequent collaborators like Nedelle Torrisi, adrienne maree brown, Hannah Cohen, and The National’s Bryce Dessner (who adds his guitar skills to the heart-bursting epic “Shit Talk”), the record certainly sounds like a full-group effort in opposition to the angsty isolation that streaked *The Ascension*. But at the heart of *Javelin* is Stevens’ vocals, the intimacy of which makes listeners feel as if they’re mere feet away from him. There’s callbacks to Stevens’ discography throughout, from the *Age of Adz*-esque digital dissolve that closes out “Genuflecting Ghost” to the rustic Flannery O’Connor evocations of “Everything That Rises,” recalling *Seven Swans*’ inspirational cues from the late fiction writer. Ultimately, though, *Javelin* finds Stevens emerging from the depressive cloud of *The Ascension* armed with pleas for peace and a distinct yearning to belong and be embraced—powerful messages delivered on high, from one of the 21st century’s most empathetic songwriters.

ANOHNI’s music revolves around the strength found in vulnerability, whether it’s the naked trembling of her voice or the way her lyrics—“It’s my fault”; “Why am I alive?”; “You are an addict/Go ahead, hate yourself”—cut deeper the simpler they get. Her first album of new material with her band the Johnsons since 2010’s *Swanlights* sets aside the more experimental/electronic quality of 2016’s *HOPELESSNESS* for the tender avant-soul most listeners came to know her by. She mourns her friends (“Sliver of Ice”), mourns herself (“It’s My Fault”), and catalogs the seemingly limitless cruelty of humankind (“It Must Change”) with the quiet resolve of someone who knows that anger is fine but the true warriors are the ones who kneel down and open their hearts.

“As I got older I learned I’m a drinker/Sometimes a drink feels like family,” Mitski confides with disarming honesty on “Bug Like an Angel,” the strummy, slow-build opening salvo from her seventh studio album that also serves as its lead single. Moments later, the song breaks open into its expansive chorus: a convergence of cooed harmonies and acoustic guitar. There’s more cracked-heart vulnerability and sonic contradiction where that came from—no surprise considering that Mitski has become one of the finest practitioners of confessional, deeply textured indie rock. Recorded between studios in Los Angeles and her recently adopted home city of Nashville, *The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We* mostly leaves behind the giddy synth-pop experiments of her last release, 2022’s *Laurel Hell*, for something more intimate and dreamlike: “Buffalo Replaced” dabbles in a domestic poetry of mosquitoes, moonlight, and “fireflies zooming through the yard like highway cars”; the swooning lullaby “Heaven,” drenched in fluttering strings and slide guitar, revels in the heady pleasures of new love. The similarly swaying “I Don’t Like My Mind” pithily explores the daily anxiety of being alive (sometimes you have to eat a whole cake just to get by). The pretty syncopations of “The Deal” build to a thrilling clatter of drums and vocals, while “When Memories Snow” ropes an entire cacophonous orchestra—French horn, woodwinds, cello—into its vivid winter metaphors, and the languid balladry of “My Love Mine All Mine” makes romantic possessiveness sound like a gift. The album’s fuzzed-up closer, “I Love Me After You,” paints a different kind of picture, either postcoital or defiantly post-relationship: “Stride through the house naked/Don’t even care that the curtains are open/Let the darkness see me… How I love me after you.” Mitski has seen the darkness, and on *The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We*, she stares right back into the void.

The first song on Lil Yachty’s *Let’s Start Here.* is nearly seven minutes long and features breathy singing from Yachty, a freewheeling guitar solo, and a mostly instrumental second half that calls to mind TV depictions of astral projecting. “the BLACK seminole.” is an extremely fulfilling listen, but is this the same guy who just a few months earlier delivered the beautifully off-kilter and instantly viral “Poland”? Better yet, is this the guy who not long before that embedded himself with Detroit hip-hop culture to the point of a soft rebrand as *Michigan Boy Boat*? Sure is. It’s just that, as he puts it on “the BLACK seminole.,” he’s got “No time to joke around/The kid is now a man/And the silence is filled with remarkable sounds.” We could call the silence he’s referring to the years since his last studio album, 2020’s *Lil Boat 3*, but he’s only been slightly less visible than we’re used to, having released the aforementioned *Michigan Boy Boat* mixtape while also lending his discerning production ear to Drake and 21 Savage’s ground-shaking album *Her Loss*. Collaboration, though, is the name of the game across *Let’s Start Here.*, an album deeply indebted to some as yet undisclosed psych-rock influences, with repeated production contributions from onetime blog-rock darlings Miles Benjamin Anthony Robinson and Patrick Wimberly, as well as multiple appearances from Diana Gordon, a Queens, New York-hailing singer who made a noise during the earliest parts of her career as Wynter Gordon. Also present are R&B singer Fousheé and Beaumont, Texas, rap weirdo Teezo Touchdown, though rapping is infrequent. In fact, none of what Yachty presents here—which includes dalliances with Parliament-indebted acid funk (“running out of time”), ’80s synthwave (“sAy sOMETHINg,” “paint THE sky”), disco (“drive ME crazy!”), symphonic prog rock (“REACH THE SUNSHINE.”), and a heady monologue called “:(failure(:”—is in any way reflective of any of Yachty’s previous output. Which begs the question, where did all of this come from? You needn’t worry about that, says Yachty on the “the ride-,” singing sternly: “Don’t ask no questions on the ride.”

As Olivia Rodrigo set out to write her second album, she froze. “I couldn\'t sit at the piano without thinking about what other people were going to think about what I was playing,” she tells Apple Music. “I would sing anything and I\'d just be like, ‘Oh, but will people say this and that, will people speculate about whatever?’” Given the outsized reception to 2021’s *SOUR*—which rightly earned her three Grammys and three Apple Music Awards that year, including Top Album and Breakthrough Artist—and the chatter that followed its devastating, extremely viral first single, “drivers license,” you can understand her anxiety. She’d written much of that record in her bedroom, free of expectation, having never played a show. The week before it was finally released, the then-18-year-old singer-songwriter would get to perform for the first time, only to televised audiences in the millions, at the BRIT Awards in London and on *SNL* in New York. Some artists debut—Rodrigo *arrived*. But looking past the hype and the hoo-ha and the pressures of a famously sold-out first tour (during a pandemic, no less), trying to write as anticipated a follow-up album as there’s been in a very long time, she had a realization: “All I have to do is make music that I would like to hear on the radio, that I would add to my playlist,” she says. “That\'s my sole job as an artist making music; everything else is out of my control. Once I started really believing that, things became a lot easier.” Written alongside trusted producer Dan Nigro, *GUTS* is both natural progression and highly confident next step. Boasting bigger and sleeker arrangements, the high-stakes piano ballads here feel high-stakes-ier (“vampire”), and the pop-punk even punkier (“all-american bitch,” which somehow splits the difference between Hole and Cat Stevens’ “Here Comes My Baby”). If *SOUR* was, in part, the sound of Rodrigo picking up the pieces post-heartbreak, *GUTS* finds her fully healed and wholly liberated—laughing at herself (“love is embarrassing”), playing chicken with disaster (the Go-Go’s-y “bad idea right?”), not so much seeking vengeance as delighting in it (“get him back!”). This is Anthem Country, joyride music, a set of smart and immediately satisfying pop songs informed by time spent onstage, figuring out what translates when you’re face-to-face with a crowd. “Something that can resonate on a recording maybe doesn\'t always resonate in a room full of people,” she says. “I think I wrote this album with the tour in mind.” And yet there are still moments of real vulnerability, the sort of intimate and sharply rendered emotional terrain that made Rodrigo so relatable from the start. She’s straining to keep it together on “making the bed,” bereft of good answers on “logical,” in search of hope and herself on gargantuan closer “teenage dream.” Alone at a piano again, she tries to make sense of a betrayal on “the grudge,” gathering speed and altitude as she goes, each note heavier than the last, “drivers license”-style. But then she offers an admission that doesn’t come easy if you’re sweating a reaction: “It takes strength to forgive, but I don’t feel strong.” In hindsight, she says, this album is “about the confusion that comes with becoming a young adult and figuring out your place in this world and figuring out who you want to be. I think that that\'s probably an experience that everyone has had in their life before, just rising from that disillusionment.” Read on as Rodrigo takes us inside a few songs from *GUTS*. **“all-american bitch”** “It\'s one of my favorite songs I\'ve ever written. I really love the lyrics of it and I think it expresses something that I\'ve been trying to express since I was 15 years old—this repressed anger and feeling of confusion, or trying to be put into a box as a girl.” **“vampire”** “I wrote the song on the piano, super chill, in December of \[2022\]. And Dan and I finished writing it in January. I\'ve just always been really obsessed with songs that are very dynamic. My favorite songs are high and low, and reel you in and spit you back out. And so we wanted to do a song where it just crescendoed the entire time and it reflects the pent-up anger that you have for a situation.” **“get him back!”** “Dan and I were at Electric Lady Studios in New York and we were writing all day. We wrote a song that I didn\'t like and I had a total breakdown. I was like, ‘God, I can\'t write songs. I\'m so bad at this. I don\'t want to.’ Being really negative. Then we took a break and we came back and we wrote ‘get him back!’ Just goes to show you: Never give up.” **“teenage dream”** “Ironically, that\'s actually the first song we wrote for the record. The last line is a line that I really love and it ends the album on a question mark: ‘They all say that it gets better/It gets better the more you grow/They all say that it gets better/What if I don\'t?’ I like that it’s like an ending, but it\'s also a question mark and it\'s leaving it up in the air what this next chapter is going to be. It\'s still confused, but it feels like a final note to that confusion, a final question.”

“I feel like there are two sides of me,” says the Nashville-based singer-songwriter and guitar virtuoso known as Sunny War. “One of them is very self-destructive, and the other is trying to work with that other half to keep things balanced.” That’s the central conflict on her fourth album, the eclectic and innovative Anarchist Gospel, which documents a time when it looked like the self-destructive side might win out. Extreme emotions can make that battle all the more perilous, yet from such trials Sunny has crafted a set of songs that draw on a range of ideas and styles, as though she’s marshaling all her forces to get her ideas across: ecstatic gospel, dusty country blues, thoughtful folk, rip-roaring rock and roll, even avant garde studio experiments. She melds them together into a powerful statement of survival, revealing a probing songwriter who indulges no comforting platitudes and a highly innovative guitarist who deploys spidery riffs throughout every song. Because it promises not healing but resilience and perseverance, because it doesn’t take shit for granted, Anarchist Gospel holds up under such intense emotional pressure, acknowledging the pain of living while searching for something that lies just beyond ourselves, some sense of balance between the bad and the good.

Veteran LA noise-rock trio HEALTH’s 2023 LP *RAT WARS* builds on their noise-centric industrial exercises, accentuating their hardcore tendencies with dance grooves, haunted synths, and wall-of-sound guitar lines. Taking influences from Nine Inch Nails, Ministry, and contemporaries like A Place to Bury Strangers, HEALTH builds deeply twisted odes to sweaty nights on the club floor and long mornings trying to fend off the sun. Like its predecessor, 2019’s *VOL. 4 :: SLAVES OF FEAR*, *RAT WARS* blends pain and catharsis, emptiness and ecstasy. On “UNLOVED,” the trio of Benjamin Miller, Jake Duzsik, and John Famiglietti cook up a track built around military-grade snare drums, gnarling synths, and hi-hats that slosh like boots in deep rain puddles. Duzsik takes the vocal lead, conjuring up a deeply dark tale as he croons in an almost-snarl, “And it was not my fault you were unloved when you were a child/I wasn\'t there.”

Blur’s first record since 2015’s *The Magic Whip* arrived in the afterglow of triumph, two weeks after a pair of joyful reunion shows at Wembley Stadium. However, celebration isn’t a dominant flavor of *The Ballad of Darren*. Instead, the album asks questions that tend to nag at you more firmly in middle age: Where are we now? What’s left? Who have I become? The result is a record marked by loss and heartbreak. “I’m sad,” Damon Albarn tells Apple Music’s Matt Wilkinson. “I’m officially a sad 55-year-old. It’s OK being sad. It’s almost impossible not to have some sadness in your life by the age of 55. If you’ve managed to get to 55—I can only speak because that’s as far as I’ve managed to get—and not had any sadness in your life, you’ve had a blessed, charmed life.” The songs were initially conceived by Albarn as he toured with Gorillaz during the autumn of 2022, before Blur brought them to life at Albarn’s studios in London and Devon in early 2023. Guitarist Graham Coxon, bassist Alex James, and drummer Dave Rowntree add to the visceral tug of Albarn’s words and music with invention and nuance. On “St. Charles Square,” where the singer sits alone in a basement flat, suffering consequences and spooked by regrets, temptations, and ghosts from his past, Coxon’s guitar gasps with anguish and shivers with anxiety. “That became our working relationship,” says Coxon. “I had to glean from whatever lyrics might be there, or just the melody, or just the chord sequences, what this is going to be—to try to focus that emotional drive, try and do it with guitars.” To hear Coxon, James, and Rowntree join Albarn, one by one, in the relatively optimistic rhythms of closer “The Heights” is to sense a band rejuvenated by each other’s presence. “It was potentially quite daunting making another record at this stage of your career,” says James. “But, actually, from the very first morning, it was just effortless, joyous, weightless. The very first time we ever worked together, the four of us in a room, we wrote a song that we still play today \[‘She’s So High’\]. It was there instantly. And then we spent years doing it for hours every day. Like, 15 years doing nothing else, and we’ve continued to dip back in and out of it. That’s an incredibly precious thing we’ve got.” Blur’s own bond may be healthy but *The Ballad of Darren* carries a heavy sense of dropped connections. On the sleepy, piano-led “Russian Strings,” Albarn’s in Belgrade asking, “Where are you now?/Are you coming back to us?/Are you online?/Are you contactable again?” before wondering, “Why don’t you talk to me anymore?” against the electro pulses and lopsided waltz of “Goodbye Albert.” The heartbreak is most plain on “Barbaric,” where the shock and uncertainty of separation pierces Coxon’s pretty jangle: “We have lost the feeling that we thought we’d never lose/It is barbaric, darling.” As intimate as that feels, there’s usually enough ambiguity to Albarn’s reflections to encourage your own interpretations. “That’s why I kind of enjoy writing lyrics,” he says. “It’s to sort of give them enough space to mean different things to people.” On “The Heights,” there’s a sense that some connections can be reestablished, perhaps in another time, place, or dimension. Here, at the end, Albarn sings, “I’ll see you in the heights one day/I’ll get there too/I’ll be standing in the front row/Next to you”—placing us at a gig, just as opener “The Ballad” did with the Coxon’s line “I met you at an early show.” The song reaches a discordant finale of strobing guitars that stops sharply after a few seconds, leaving you in silence. It’s a feeling of being ejected from something compelling and intense. “I think these songs, they start with almost an innocence,” says Coxon. “There’s sort of an obliteration of these characters that I liken to writers like Paul Auster, where these characters are put through life, like we all are put through life, and are sort of spat out. So the difference between the gig at the beginning and that front row at the end is very different—the taste and the feeling of where that character is is so different. It’s almost like spirit, it’s not like an innocent young person anymore. And that’s something about the journey of the album.”

Each album from Oneohtrix Point Never, the project of songwriter and producer Daniel Lopatin, is informed by an open-ended theme or prompt. This allows each release to feel tied to some general philosophy while still being wholly unique. On 2015’s *Garden of Delete*, he made songs built around made-up scrapped vocals from pop stars; 2018’s *Age Of* pictured a world gone insane, with nothing left but artificial intelligence to determine what cultural touchstones were deemed worth keeping. On his 2023 album *Again*, the artist once again concocts a daring concept, this time imagining the project as a conversation between his current and former selves. On the album he asks, “What’s worth keeping? What do we throw away?” Among the detritus that inherently comes alongside radical technological development, what will outlast us? Lopatin recruited a number of collaborators for the project, including Robert Ames, Lee Ranaldo, Jim O’Rourke, Xiu Xiu, and Lovesliescrushing. While they’re mostly disparate in spirit, each artist has at times toyed with the interplay between electric and acoustic clashes, which Lopatin highlights on *Again*. Gorgeously arranged string suites come crashing against grating synths on the title track; massive electronic drums launch Lopatin’s voice towards the heavens on “Krumville.” Acoustic guitar strums get similarly propelled on “Memories of Music.” Lopatin collides sounds from different eras of his discography, highlighting both the diversity of his work and the underlying ideas he returns to time and again. There’s no such thing as *one* Oneohtrix Point Never signature sound; Lopatin’s ear is too shifty, too excited by what comes next and how it emerges. His trademark is a hodgepodge of inspirations—from full orchestral symphonies to barely perceptible VCR buzz. On *Again*, Daniel Lopatin taps into all these worlds—the ones he has created and the futures he imagines—to capture a moment in time, before it shifts once again.