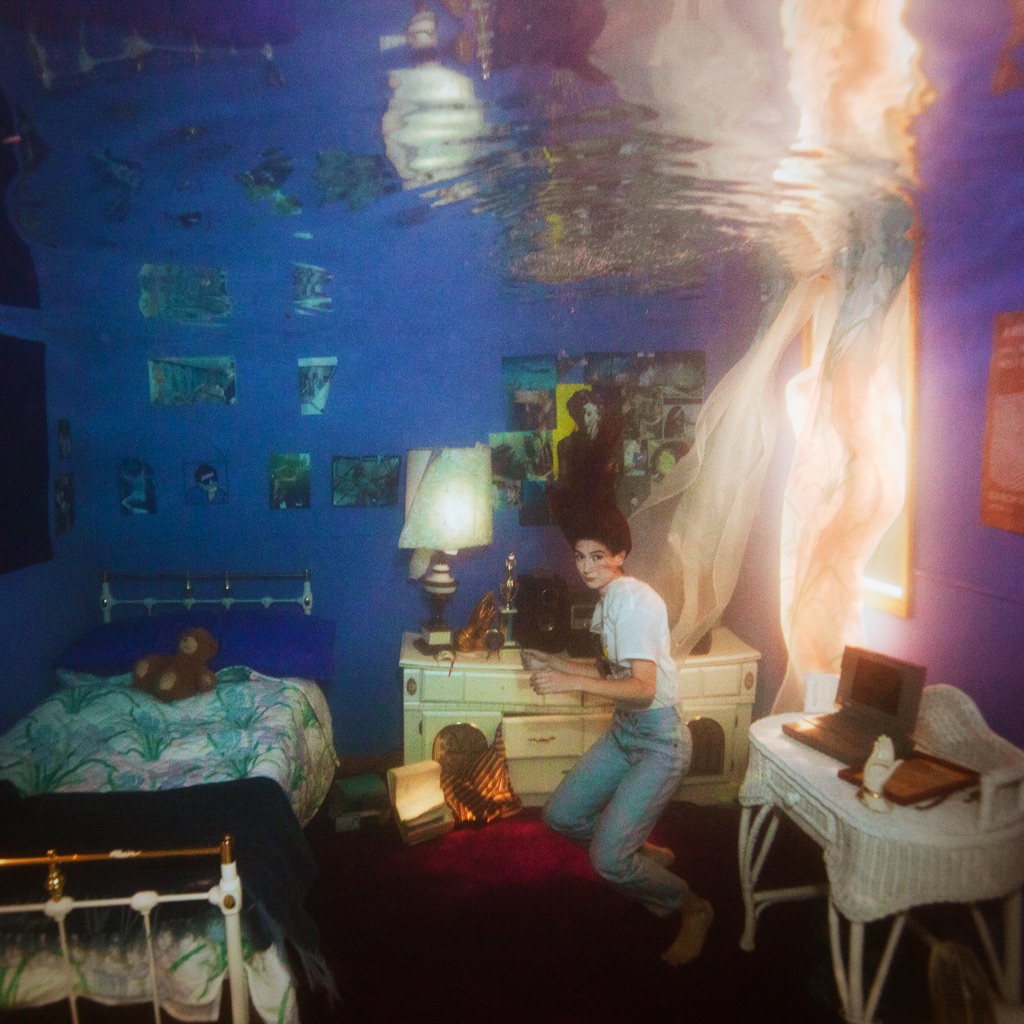

Singer-songwriter Natalie Mering’s fourth album as Weyes Blood conjures the feeling of a beautiful object on a shelf just out of reach: You want to touch it, but you can’t, and so you do the next best thing—you dream about it, ache for it, and then you ache some more. Grand, melodramatic, but keenly self-aware, the music here pushes Mering’s \'70s-style chamber pop to its cinematic brink, suffusing stories of everything from fumbled romance (the McCartney-esque “Everyday”) to environmental apocalypse (“Wild Time”) with a dreamy, foggy almost-thereness both gorgeous and profoundly unsettling. A self-described “nostalgic futurist,” Mering doesn’t recreate the past so much as demonstrate how the past is more or less a fiction to begin with, a story we love hearing no matter how sad its unreachability makes us. Hence the album’s centerpiece, “Movies,” which wonders—gorgeously, almost religiously—why life feels so messy by comparison. As to the thematic undercurrent of apocalypse, well, if extinction is as close as science says it is, we might as well have something pretty to play us out.

The phantom zone, the parallax, the upside down—there is a rich cultural history of exploring in-between places. Through her latest, Titanic Rising, Weyes Blood (a.k.a. Natalie Mering) has, too, designed her own universe to soulfully navigate life’s mysteries. Maneuvering through a space-time continuum, she intriguingly plays the role of melodic, sometimes melancholic, anthropologist. Tellingly, Mering classifies Titanic Rising as the Kinks meet WWII or Bob Seger meets Enya. The latter captures the album’s willful expansiveness (“You can tell there’s not a guy pulling the strings in Enya’s studio,” she notes, admiringly). The former relays her imperative to connect with listeners. “The clarity of Bob Seger is unmistakable. I’m a big fan of conversational songwriting,” she adds. “I just try to do that in a way that uses abstract imagery as well.” “An album is like a Rubik’s Cube,” she says. “Sometimes you get all the dimensions—the lyrics, the melody, the production—to line up. I try to be futuristic and ancient at once, which is a difficult alchemy. It’s taken a lot of different tries to get it right.” As concept-album as it may sound, it’s also a devoted exercise in realism, albeit occasionally magical. Here, the throwback-cinema grandeur of “A Lot’s Gonna Change” gracefully coexists with the otherworldly title track, an ominous instrumental. Titanic Rising, written and recorded during the first half of 2018, is the culmination of three albums and years of touring: stronger chops and ballsier decisions. It’s an achievement in transcendent vocals and levitating arrangements—one she could reach only by flying under the radar for so many years. “I used to want to belong,” says the L.A. based musician. “I realized I had to forge my own path. Nobody was going to do that for me. That was liberating. I became a Joan of Arc solo musician.” The Weyes Blood frontwoman grew up singing in gospel and madrigal choirs. “Classical and Renaissance music really influenced me,” says Mering, who first picked up a guitar at age 8. (Listen closely to Titanic Rising, and you’ll also hear the jazz of Hoagy Carmichael mingle with the artful mysticism of Alejandro Jodorowsky and the monomyth of scholar Joseph Campbell.) “Something to Believe,” a confessional that makes judicious use of the slide guitar, touches on that cosmological upbringing. “Belief is something all humans need. Shared myths are part of our psychology and survival,” she says. “Now we have a weird mishmash of capitalism and movies and science. There have been moments where I felt very existential and lost.” As a kid, she filled that void with Titanic. (Yes, the movie.) “It was engineered for little girls and had its own mythology,” she explains. Mering also noticed that the blockbuster romance actually offered a story about loss born of man’s hubris. “It’s so symbolic that The Titanic would crash into an iceberg, and now that iceberg is melting, sinking civilization.” Today, this hubris also extends to the relentless adoption of technology, at the expense of both happiness and attention spans. The track “Movies” marks another Titanic-related epiphany, “that movies had been brainwashing people and their ideas about romantic love.” To that end, Mering has become an expert at deconstructing intimacy. Sweeping and string-laden, “Andromeda” seems engineered to fibrillate hearts. “It’s about losing your interest in trying to be in love,” she says. “Everybody is their own galaxy, their own separate entity. There is a feeling of needing to be saved, and that’s a lot to ask of people.” Its companion track, “Everyday,” “is about the chaos of modern dating,” she says, “the idea of sailing off onto your ships to nowhere to deal with all your baggage.” But Weyes Blood isn’t one to stew. Her observations play out in an ethereal saunter: far more meditative than cynical. “I experience reality on a slower, more hypnotic level,” she says. “I’m a more contemplative kind of writer.” To Mering, listening and thinking are concurrent experiences. “There are complicated influences mixed in with more relatable nostalgic melodies,” she says. “In my mind my music feels so big, a true production. I’m not a huge, popular artist, but I feel like one when I’m in the studio. But it’s never taking away from the music. I’m just making a bigger space for myself.”

Look past its futurist textures and careful obfuscations, and there’s something deeply human about FKA twigs’ 21st-century R&B. On her second full-length, the 31-year-old British singer-songwriter connects our current climate to that of Mary Magdalene, a healer whose close personal relationship with Christ brought her scorn from those who would ultimately write her story: men. “I\'m of a generation that was brought up without options in love,” she tells Apple Music. “I was told that as a woman, I should be looked after. It\'s not whether I choose somebody, but whether somebody chooses me.” Written and produced by twigs, with major contributions from Nicolas Jaar, *MAGDALENE* is a feminist meditation on the ways in which we relate to one another and ourselves—emotionally, sexually, universally—set to sounds that are at once modern and ancient. “Now it’s like, ‘Can you stand up in my holy terrain?’” she says, referencing the titular lyric from her mid-album collaboration with Future. “‘How are we going to be equals in this? Spiritually, am I growing? Do you make me want to be a better person?’ I’m definitely still figuring it out.” Here, she walks us through the album track by track. **thousand eyes** “All the songs I write are autobiographical. Anyone that\'s been in a relationship for a long time, you\'re meshed together. But unmeshing is painful, because you have the same friends or your families know each other. No matter who you are, the idea of leaving is not only a heart trauma, but it\'s also a social trauma, because all of a sudden, you don\'t all go to that pub that you went to together. The line \[\'If I walk out the door/A thousand eyes\'\] is a reference to that. At the time, I was listening to a lot of Gregorian music. I’d started really getting into medieval chords before that, and I\'d found some musicians that play medieval music and done a couple sessions with them. Even on \[2014\'s\] *LP1*, I had ‘Closer,’ which is essentially a hymn. I spent a lot of time in choir as a child and I went to Sunday school, so it’s part of who I am at this stage.” **home with you** “I find things like that interesting in the studio, just to play around and bring together two completely different genres—like Elton John chords and a hip-hop riff. That’s what ‘home with you’ was for me: It’s a ballad and it\'s sad, but then it\'s a bop as well, even though it doesn\'t quite ever give you what you need. It’s about feeling pulled in all directions: as a daughter, or as a friend, or as a girlfriend, or as a lover. Everyone wanting a piece of you, but not expressing it properly, so you feel like you\'re not meeting the mark.” **sad day** “It’s like, ‘Will you take another chance with me? Can we escape the mundane? Can we escape the cyclical motion of life and be in love together and try something that\'s dangerous and exhilarating? Yeah, I know I’ve made you sad before, but will you give me another chance?\' I wrote this song with benny blanco and Koreless. I love to set myself challenges, and it was really exciting to me, the challenge of retaining my sound while working with a really broad group of people. I was lucky working with Benny, in the fact that he creates an environment where, as an artist, you feel really comfortable to be yourself. To me, that\'s almost the old-school definition of a producer: They don\'t have to be all up in your grill, telling you what to do. They just need to lay a really beautiful, fertile soil, so that you can grow to be the best you in the moment.” **holy terrain** “I’m saying that I want to find a man that can stand up next to me, in all of my brilliance, and not feel intimidated. To me, Future’s saying, ‘Hey, I fucked up. I filled you with poison. I’ve done things to make you jealous. Can you heal me? Can you tell me how to be a better man? I need the guidance, of a woman, to show me how to do that.’ I don\'t think that there are many rappers that can go there, and just put their cards on the table like that. I didn\'t know 100%, once I met Future, that it would be right. But we spoke on the phone and I played him the album and I told him what it was about: ‘It’s a very female-positive, femme-positive record.’ And he was just like, ‘Yeah. Say no more. I\'ve got this.’ And he did. He crushed it. To have somebody who\'s got patriarchal energy come through and say that, wanting to stand up and be there for a woman, wanting to have a woman that\'s an equal—that\'s real.” **mary magdalene** “Let’s just imagine for one second: Say Jesus and Mary Magdalene are really close, they\'re together all the time. She\'s his right-hand woman, she’s his confidante, she\'s healing people with him and a mystic in her own right. So, at that point, any man and woman that are spending that much time together, they\'re likely to be what? Lovers. Okay, cool. So, if Mary had Jesus\' children, that basically debunks the whole of history. Now, I\'m not saying that happened. What I\'m saying is that the idea of people thinking that might happen is potentially really dangerous. It’s easier to call her a whore, because as soon as you call a woman a whore, it devalues her. I see her as Jesus Christ\'s equal. She’s a male projection and, I think, the beginning of the patriarchy taking control of the narrative of women. Any woman that\'s done anything can be subject to that; I’ve been subject to that. It felt like an apt time to be talking about it.” **fallen alien** “When you\'re with someone, and they\'re sleeping, and you look at them, and you just think, \'No.\' For me, it’s that line, \[\'When the lights are on, I know you/When you fall asleep, I’ll kick you down/By the way you fell, I know you/Now you’re on your knees\'\]. You\'re just so sick of somebody\'s bullshit, you\'re just taking it all day, and then you\'re in bed next to them, and you\'re just like, ‘I can\'t take this anymore.’” **mirrored heart** “People always say, ‘Whoever you\'re with, they should be a reflection of yourself.’ So, if you\'re looking at someone and you think, ‘You\'re a shitbag,’ then you have to think about why it was that person, at that time, and what\'s connecting you both. What is the reflection? For others that have found a love that is a true reflection of themselves, they just remind me that I don\'t have that, a mirrored heart.” **daybed** “Have you ever forgotten how to spell a really simple word? To me, depression\'s a bit like that: Everything\'s quite abstract, and even slightly dizzy, but not in a happy way. It\'s like a very slow circus. Suddenly the fruit flies seem friendly, everything in the room just starts having a different meaning and you even have a different relationship with the way the sofa cushions smell. \[Masturbation\] is something to raise your endorphins, isn\'t it? It’s either that or try and go to the gym, or try and eat something good. You almost can\'t put it into words, but we\'ve all been there. I sing, \'Active are my fingers/Faux, my cunnilingus\': You\'re imagining someone going down on you, but they\'re actually not. You open your eyes, and you\'re just there, still on your sofa, still watching daytime TV.” **cellophane** “It\'s just raw, isn\'t it? It didn\'t need a thing. The vocal take that\'s on the record is the demo take. I had a Lyft arrive outside the studio and I’d just started playing the piano chords. I was like, ‘Hey, can you just give me like 20, 25 minutes?’ And I recorded it as is. I remember feeling like I wanted to cry, but I just didn\'t feel like it was that suitable to cry at a studio session. I often want everything to be really intricate and gilded, and I want to chip away at everything, and sculpt it, and mold it, and add layers. The thing I\'ve learned on *MAGDALENE* is that you don\'t need to do that all the time, and just because you can do something, it doesn\'t mean you should. That\'s been a real growing experience for me—as a musician, as a producer, as a singer, even as a dancer. Something in its most simple form is beautiful.”

Part of the fun of listening to Lana Del Rey’s ethereal lullabies is the sly sense of humor that brings them back down to earth. Tucked inside her dreamscapes about Hollywood and the Hamptons are reminders—and celebrations—of just how empty these places can be. Here, on her sixth album, she fixes her gaze on another place primed for exploration: the art world. Winking and vivid, *Norman F\*\*\*\*\*g Rockwell!* is a conceptual riff on the rules that govern integrity and authenticity from an artist who has made a career out of breaking them. In a 2018 interview with Apple Music\'s Zane Lowe, Del Rey said working with songwriter Jack Antonoff (who produced the album along with Rick Nowels and Andrew Watt) put her in a lighter mood: “He was so *funny*,” she said. Their partnership—as seen on the title track, a study of inflated egos—allowed her to take her subjects less seriously. \"It\'s about this guy who is such a genius artist, but he thinks he’s the shit and he knows it,” she said. \"So often I end up with these creative types. They just go on and on about themselves and I\'m like, \'Yeah, yeah.\' But there’s merit to it also—they are so good.” This paradox becomes a theme on *Rockwell*, a canvas upon which she paints with sincerity and satire and challenges you to spot the difference. (On “The Next Best American Record,” she sings, “We were so obsessed with writing the next best American record/’Cause we were just that good/It was just that good.”) Whether she’s wistfully nostalgic or jaded and detached is up for interpretation—really, everything is. The album’s finale, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have - but I have it,” is packaged like a confessional—first-person, reflective, sung over simple piano chords—but it’s also flamboyantly cinematic, interweaving references to Sylvia Plath and Slim Aarons with anecdotes from Del Rey\'s own life to make us question, again, what\'s real. When she repeats the phrase “a woman like me,” it feels like a taunt; she’s spent the last decade mixing personas—outcast and pop idol, debutante and witch, pinup girl and poet, sinner and saint—ostensibly in an effort to render them all moot. Here, she suggests something even bolder: that the only thing more dangerous than a complicated woman is one who refuses to give up.

“Laying in the grass, we were dragging on loud/Got my hand in your hand and my head in the clouds.” This is the scene, set with acoustic atmospherics and frontman Jade Lilitri’s familiar, layered, honey-sweet-but-burnt-around-the-edges vocals, that flickers to life at the start of oso oso’s new full-length, basking in the glow. The track, simply called “intro,” is just that: an intimate, humble, and hopeful prologue that prefaces a record radically committed to letting the light in—because Lilitri knows the darkness like the back of his hand. The spacious opening proposition of “intro” gives way to “the view,” an electric, invigorating indie rock banger that showcases Lilitri’s slick, effortless melodic excellence and lyrical precision (“I’ll grow, we’ll see/There’s something good in me”). The title track follows, driving home the record’s thesis on a chorus like a roman candle cracking a mid-July night sky: “These days, it feels like all I know is this phase/I hope I’m basking in the glow of something bigger I don’t know.” Lead single “dig” rounds out this first act with rainy-day riffing and hushed, staccato vocal delivery on the verse before its tense, charged chorus: “There’s this hole in my soul/So how far do you wanna go?” Lilitri asks, his voice ethereal and couched in bubblegum harmony. It’s a slow build, twining the best parts of emo around pop punk sensibilities and, eventually, wide-open alt-rock anthemics at the track’s climax before sinking back, in a slow-motion fall, to a deserted shoegaze outro. It’s an ambitious, complex scheme, and one that captures the spirit of the record: clutching tight to the unbridled glee of the short, sunny, major-key moments before they dissolve. basking in the glow is a wrestle, and it is hard work; it is the sound of refusing to capitulate to darkness, every goddamn day. It is a practice, or perhaps a battle plan (“I see my demise, I feel it coming/I got one sick plan to save me from it,” Lilitri sings, his voice and hurried guitar crackling as if they’re coming through a bedroom tape recorder.) It is filled with the delightful, subtle melodic imagination that characterizes the sound Lilitri has perfected with oso oso, but this time out, he’s put this sound to use declaring happiness (“I got a glimpse of this feeling, I’m trying to stay in that lane,” on “impossible game”) and sketching out, with keen, desperate detail, warm memories to hold onto (“‘Oh c’mon Charlie, a little louder’/I say as I hear her singing out from the shower,” on “charlie”). This “one sick plan” and its bright disposition does falter and fade. The darkness does return—it always will—but Lilitri has come to terms with it, armoring himself with the good he’s found. Even as the record ends with a relationship’s demise, Lilitri is clear-eyed, leaving us squarely in the sunlight: “And in the end I think that’s fine/Cause you and I had a very nice time.”

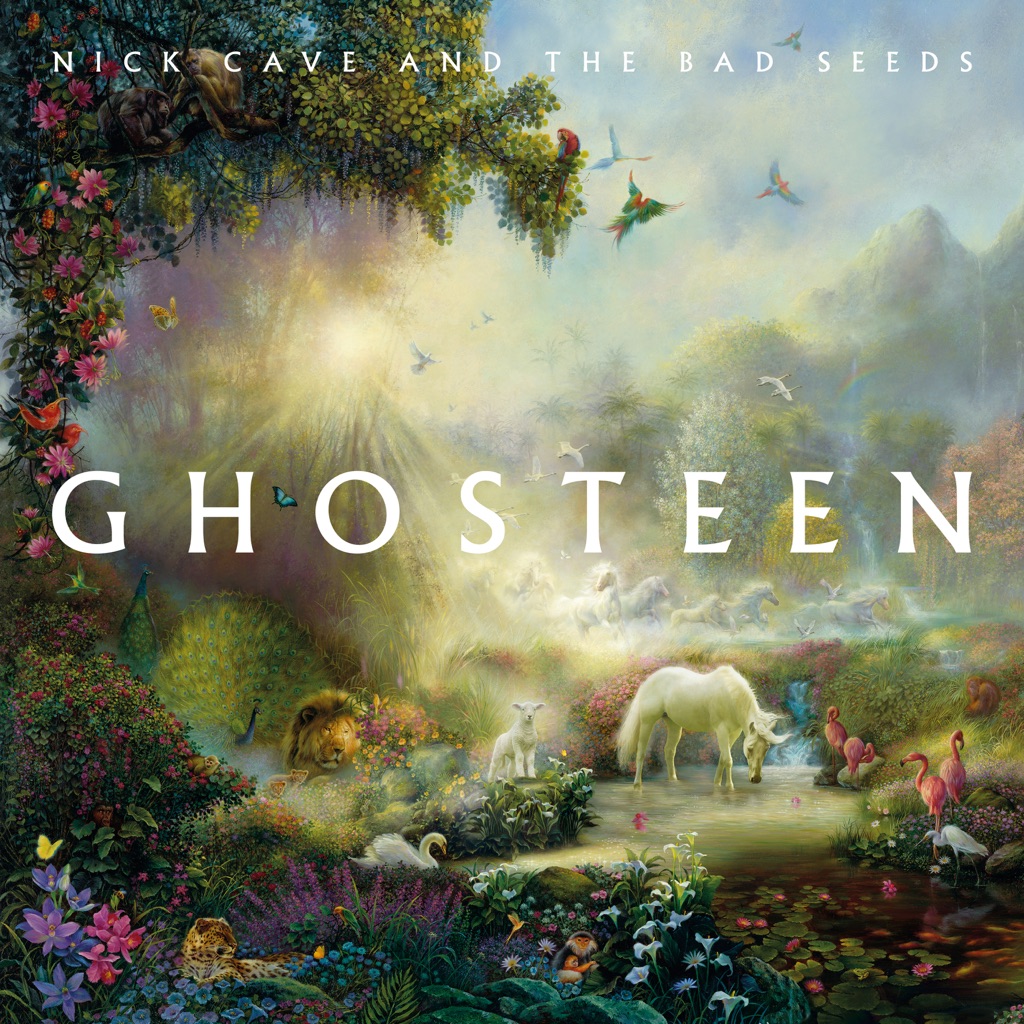

The cover art for Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ 17th album couldn’t feel more removed from the man once known as a snarling, terrifying prince of poetic darkness. This heavenly forest with its vibrant flowers, rays of sun, and woodland creatures feels comically opposed to anything Cave has ever represented—but perhaps that’s the point. This pastel fairy tale sets the scene for *Ghosteen*, his most minimalist, supernatural work to date, in which he slips between realms of fantasy and reality as a means to accept life and death, his past and future. In his very first post on The Red Hand Files—the website Cave uses to receive and respond to fan letters—he spoke of rebuilding his relationship with songwriting, which had been damaged while enduring the grief that followed his son Arthur’s death in 2015. He wrote, “I found with some practise the imagination could propel itself beyond the personal into a state of wonder. In doing so the colour came back to things with a renewed intensity and the world seemed clear and bright and new.” It is within that state of wonder that *Ghosteen* exists. “The songs on the first album are the children. The songs on the second album are their parents,” Cave has explained. Those eight “children” are misty, ambient stories of flaming mares, enchanted forests, flying ships, and the eponymous, beloved Ghosteen, described as a “migrating spirit.” The second album features two longer pieces, connected by the spoken-word “Fireflies.” He tells fantasy stories that allude to love and loss and letting go, and occasionally brings us back to reality with detailed memories of car rides to the beach and hotel rooms on rainy days. These themes aren’t especially new, but the feeling of this album is. There are no wild murder ballads or raucous, bluesy love songs. Though often melancholy, it doesn’t possess the absolute devastation and loneliness of 2016’s *Skeleton Tree*. Rather, these vignettes and symbolic myths are tranquil and gentle, much like the instrumentation behind them. With little more than synths and piano behind Cave’s vocals, *Ghosteen* might feel uneventful at times, but the calmness seems to help his imagination run free. On “Bright Horses,” he sings of “Horses broken free from the fields/They are horses of love, their manes full of fire.” But then he pulls back the curtain and admits, “We’re all so sick and tired of seeing things as they are/Horses are just horses and their manes aren’t full of fire/The fields are just fields, and there ain’t no lord… This world is plain to see, it don’t mean we can’t believe in something.” Through these dreamlike, surreal stories, Cave is finding his path to peace. And he’s learned that he isn’t alone on his journey. On “Galleon Ship,” he begins, “If I could sail a galleon ship, a long, lonely ride across the sky,” before realizing: “We are not alone, it seems, so many riders in the sky/The winds of longing in their sails, searching for the other side.”

“A real-ass n\*gga from the 305/I was raised off of Trina, Trick, Rick, and Plies,” Denzel Curry says on “CAROLMART.” Since his days as a member of Raider Klan, the Miami MC has made it a point to forge a path distinct from the influences he shouts out here. But with *ZUU*, Curry’s fourth studio album, he returns to the well from which he sprang. The album is conspicuously street-life-oriented; Curry paints a picture of a Miami he certainly grew up in, but also one rap fans may not have associated him with previously. Within *ZUU*, there are references to the city’s storied history as a drug haven (“BIRDZ”), odes to Curry’s family (“RICKY”), and retellings of his personal come-up (“AUTOMATIC”), along with a unique exhibition of Miami slang on “YOO.” Across it all, Curry is the verbose, motormouthed MC he made his name as, a profile that is especially recognizable on the album closer “P.A.T.,” where he dips in and out of a bevy of flows over the kind of scuzzy, lo-fi production that set the table for another generation of South Florida rap stars.

Big Thief had only just finished work on their 3rd album, U.F.O.F. – “the celestial twin” – days before in a cabin studio in the woods of Washington State. Now it was time to birth U.F.O.F.’s sister album – “the earth twin” – Two Hands. 30 miles west of El Paso, surrounded by 3,000 acres of pecan orchards and only a stone’s throw from the Mexican border, Big Thief (a.k.a. Adrianne Lenker, Buck Meek, Max Oleartchik, and James Krivchenia) set up their instruments as close together as possible to capture their most important collection of songs yet. Where U.F.O.F.layered mysterious sounds and effects for levitation, Two Hands grounds itself on dried-out, cracked desert dirt. In sharp contrast to the wet environment of the U.F.O.F. session, the southwestern Sonic Ranch studio was chosen for its vast desert location. The 105-degree weather boiled away any clinging memories of the green trees and wet air of the previous session. Two Hands had to be completely different — an album about the Earth and the bones beneath it. The songs were recorded live with almost no overdubs. All but two songs feature entirely live vocal takes, leaving Adrianne’s voice suspended above the mix in dry air, raw and vulnerable as ever. “Two Hands has the songs that I’m the most proud of; I can imagine myself singing them when I’m old,” says Adrianne. “Musically and lyrically, you can’t break it down much further than this. It’s already bare-bones.” Lyrically this can be felt in the poetic blur of the internal and external. These are political songs without political language. They explore the collective wounds of our Earth. Abstractions of the personal hint at war, environmental destruction, and the traumas that fuel it. Across the album, there are genuine attempts to point the listener towards the very real dangers that face our planet. When Adrianne sings “Please wake up,” she’s talking directly to the audience. Engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who were both behind U.F.O.F., capture the live energy as instinctually and honestly as possible. Sarlo teamed up with James Krivchenia to mix the album, where they sought to emphasize raw power and direct energy inherent in the takes. The journey of a song from the stage to the record is often a difficult one. Big Thief’s advantage is their bond and loving centre as a chosen family. They spend almost 100% of their lives together working towards a sound that they all agree upon. A band with this level of togetherness is increasingly uncommon. If you ask drummer James Krivchenia, bassist Max Oleartchik or guitarist Buck Meek how they write their parts, they will describe — passionately — the experience of hearing Adrianne present a new song, listening intently for hints of parts that already exist in the ether and the undertones to draw out with their respective instruments. With raw power and intimacy, Two Hands folds itself gracefully into Big Thief’s impressive discography. This body of work grows deeper and more inspiring with each new album.

In a lot of ways, you can map Alex Giannascoli’s story onto a broader story of music and art in the 2010s. Born outside Philadelphia in 1993, he started self-releasing albums online while still in high school, building a small but devoted cult that scrutinized his collage-like indie folk like it was scripture. His music got denser, more expressive, and more accomplished, he signed to venerated indie label Domino, and he worked with Frank Ocean, all—more or less—without leaving his bedroom. In other words, Giannascoli didn’t have to leave his dream-hive to find an audience; he brought his audience in, and on his terms, too. “Something I can never stress enough is I try and explain this stuff, but it never accurately reflects the process,” Giannascoli tells Apple Music, “because I’m not actually thinking that much when I’m doing it.” Recorded in the same building-block fashion as his previous albums (and with the same home studio setup), *House of Sugar* represents a new peak for Giannascoli—not just as a songwriter, but as a producer who can spin peculiar moods out of combinations that don’t make any immediate sense. It can be blissful (“Walk Away”), it can be ominous (“Sugar”), it can be grounded one minute (“Cow,” “Hope,” “Southern Sky”) and abstract the next (“Near,” “Project 2”)—a range that gives the overall experience the disjointed, saturated feeling of a half-remembered dream. Often, the prettier the music is, the bleaker the lives of the characters in the lyrics get, whether it’s the drug casualty of “Hope” or the gamblers of “SugarHouse,” who keep coming back to the tables no matter how often they lose—a contrast, Giannascoli says, that was inspired in part by the 2018 sci-fi film *Annihilation*. “From afar, everything looks bright and beautiful,” he says, “but the closer you get, the more violent it becomes.” Despite his rising profile, Giannascoli tries to remain intuitive, following inspiration whenever it shows up, keeping what he calls “that lens” on whenever possible. “I never say to myself, ‘This isn’t where I thought \[the music\] was going to go,’” he says. “Because usually I don’t have that thought in mind to begin with. And I never really end up getting surprised, because the music is unfolding before me as I make it.”

House of Sugar— Alex G’s ninth overall album and his third for Domino — emerges as his most meticulous, cohesive album yet: a statement of artistic purpose, showing off his ear for both persistent earworms and sonic adventurism.

There are musicians who suffer for their art, and then there’s Stefan Babcock. The guitarist and lead screamer for Toronto pop-punk ragers PUP has often used his music as a bullhorn to address the physical and mental toll of being in a touring rock band. The band’s 2016 album *The Dream Is Over* was inspired by Babcock seeking treatment for his ravaged vocal cords and being told by a doctor he’d never be able to sing again. Now, with that scare behind him, he’s using the aptly titled *Morbid Stuff* to address a more insidious ailment: depression. “*The Dream Is Over* was riddled with anxiety and uncertainties, but I think I was expressing myself in a more immature way,” Babcock tells Apple Music. “I feel I’ve found the language to better express those things.” Certainly, *Morbid Stuff* pulls no punches: This is an album whose idea of an opening line is “I was bored as fuck/Sitting around and thinking all this morbid stuff/Like if anyone I slept with is dead.” But of course, this being PUP—a band that built their fervent fan base through their wonderfully absurd high-concept videos—they can’t help but make a little light of the darkest subject matter. “I’m pretty aware of the fact I’m making money off my own misery—what Phoebe Bridgers called ‘the commodification of depression,’” Babcock says. “It’s a weird thing to talk about mood disorders for a living. But my intention with this record was to explore the darker things with a bit of humor, and try to make people feel less alone while they listen to it.” To that end, Babcock often directs his most scathing one-liners at himself. On the instant shout-along anthem “Free at Last,” he issues a self-diagnosis that hits like a glass of cold water in the face: “Just because you’re sad again/It doesn’t make you special at all.” “The conversation around mental health that’s happening now is such a positive thing,” Babcock says, “but one of the small drawbacks is that people are now so sympathetic to it that some people who suffer from mood disorders—and I speak from experience here—tend to use it as a crutch. I can sometimes say something to my bandmates or my girlfriend that’s pretty shitty, and they’ll be like, ‘It’s okay, Stefan’s in a different headspace right now’—and that’s *not* okay. It’s important to remind myself and other people that being depressed and being an asshole are not mutually exclusive.” Complementing Babcock’s fearless lyricism is the band’s growing confidence to step outside of the circle pit: “Scorpion Hill” begins as a lonesome barstool serenade before kicking into a dusty cowpunk gallop, while the power-pop rave-up “Closure” simmers into a sweet psychedelic breakdown that nods to one of Babcock’s all-time favorite bands, Built to Spill. And the closing “City” is PUP’s most vulnerable statement to date, a pulverizing power ballad where Babcock takes stock of his conflicted relationship with Toronto, his lifelong home. “The beginning of ‘Scorpion Hill’ and ‘City’ are by far the most mellow, softest moments we’ve ever created as a band,” Babcock says. “And I think on the last two records, we never would’ve gone there—not because we didn’t want to, but just because we didn’t think people would accept PUP if PUP wasn’t always cranked up to 10. And this time, we felt a bit more confident to dial it back in certain parts when it felt right. I feel like we’ve grown a lot as a band and shed some of our inhibitions.”

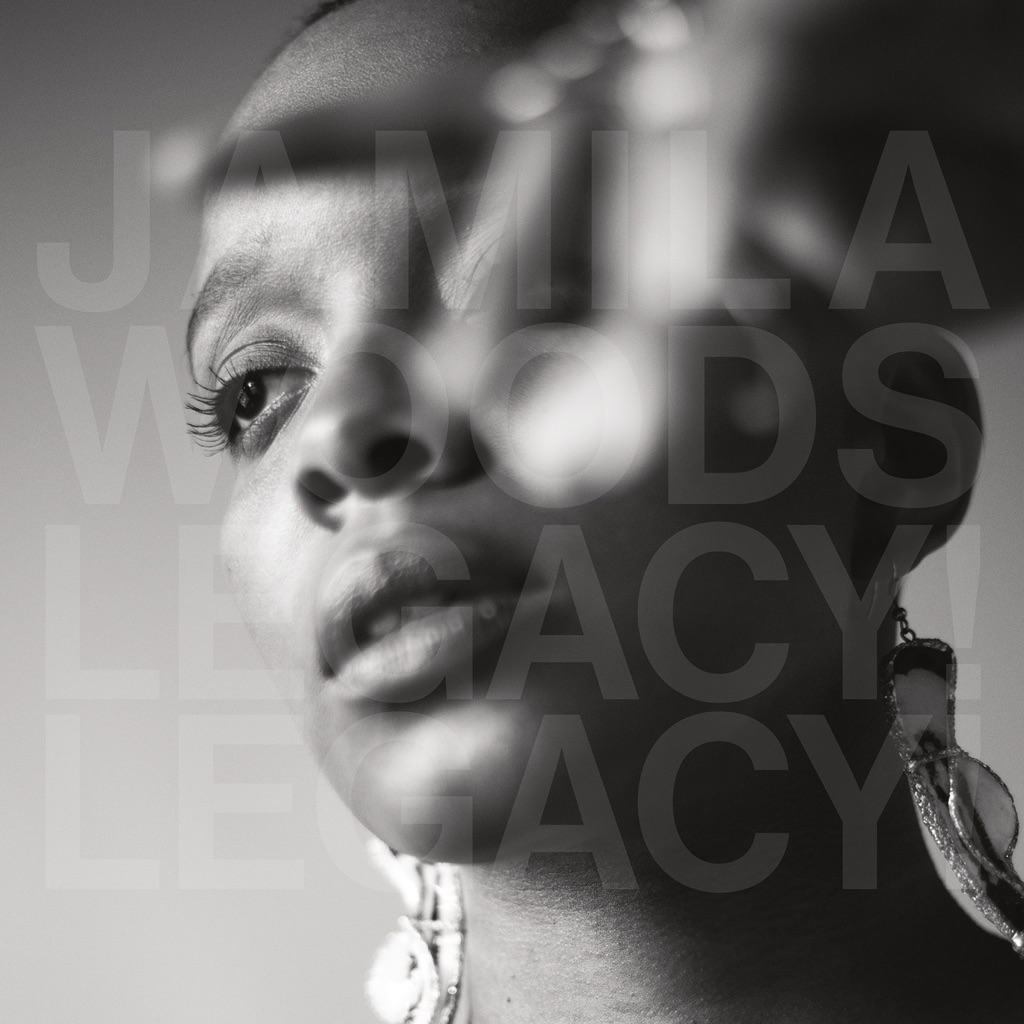

There’s nothing all that subtle about Jamila Woods naming each of these all-caps tracks after a notable person of color. Still, that’s the point with *LEGACY! LEGACY!*—homage as overt as it is original. True to her own revolutionary spirit, the Chicago native takes this influential baker’s dozen of songs and masterfully transmutes their power for her purposes, delivering an engrossingly personal and deftly poetic follow-up to her formidable 2016 breakthrough *HEAVN*. She draws on African American icons like Miles Davis and Eartha Kitt as she coos and commands through each namesake cut, sparking flames for the bluesy rap groove of “MUDDY” and giving flowers to a legend on the electro-laced funk of “OCTAVIA.”

In the clip of an older Eartha Kitt that everyone kicks around the internet, her cheekbones are still as pronounced as many would remember them from her glory days on Broadway, and her eyes are still piercing and inviting. She sips from a metal cup. The wind blows the flowers behind her until those flowers crane their stems toward her face, and the petals tilt upward, forcing out a smile. A dog barks in the background. In the best part of the clip, Kitt throws her head back and feigns a large, sky-rattling laugh upon being asked by her interviewer whether or not she’d compromise parts of herself if a man came into her life. When the laugh dies down, Kitt insists on the same, rhetorical statement. “Compromise!?!?” she flings. “For what?” She repeats “For what?” until it grows more fierce, more unanswerable. Until it holds the very answer itself. On the hook to the song “Eartha,” Jamila Woods sings “I don’t want to compromise / can we make it through the night” and as an album, Legacy! Legacy! stakes itself on the uncompromising nature of its creator, and the histories honored within its many layers. There is a lot of talk about black people in America and lineage, and who will tell the stories of our ancestors and their ancestors and the ones before them. But there is significantly less talk about the actions taken to uphold that lineage in a country obsessed with forgetting. There are hands who built the corners of ourselves we love most, and it is good to shout something sweet at those hands from time to time. Woods, a Chicago-born poet, organizer, and consistent glory merchant, seeks to honor black people first, always. And so, Legacy! Legacy! A song for Zora! Zora, who gave so much to a culture before she died alone and longing. A song for Octavia and her huge and savage conscience! A song for Miles! One for Jean-Michel and one for my man Jimmy Baldwin! More than just giving the song titles the names of historical black and brown icons of literature, art, and music, Jamila Woods builds a sonic and lyrical monument to the various modes of how these icons tried to push beyond the margins a country had assigned to them. On “Sun Ra,” Woods sings “I just gotta get away from this earth, man / this marble was doomed from the start” and that type of dreaming and vision honors not only the legacy of Sun Ra, but the idea that there is a better future, and in it, there will still be black people. Jamila Woods has a voice and lyrical sensibility that transcends generations, and so it makes sense to have this lush and layered album that bounces seamlessly from one sonic aesthetic to another. This was the case on 2016’s HEAVN, which found Woods hopeful and exploratory, looking along the edges resilience and exhaustion for some measures of joy. Legacy! Legacy! is the logical conclusion to that looking. From the airy boom-bap of “Giovanni” to the psychedelic flourishes of “Sonia,” the instrument which ties the musical threads together is the ability of Woods to find her pockets in the waves of instrumentation, stretching syllables and vowels over the harmony of noise until each puzzle piece has a home. The whimsical and malleable nature of sonic delights also grants a path for collaborators to flourish: the sparkling flows of Nitty Scott on “Sonia” and Saba on “Basquiat,” or the bloom of Nico Segal’s horns on “Baldwin.” Soul music did not just appear in America, and soul does not just mean music. Rather, soul is what gold can be dug from the depths of ruin, and refashioned by those who have true vision. True soul lives in the pages of a worn novel that no one talks about anymore, or a painting that sits in a gallery for a while but then in an attic forever. Soul is all the things a country tries to force itself into forgetting. Soul is all of those things come back to claim what is theirs. Jamila Woods is a singular soul singer who, in voice, holds the rhetorical demand. The knowing that there is no compromise for someone with vision this endless. That the revolution must take many forms, and it sometimes starts with songs like these. Songs that feel like the sun on your face and the wind pushing flowers against your back while you kick your head to the heavens and laugh at how foolish the world seems.

For a project so shrouded in mystery in the run-up to its release, the origin story behind Better Oblivion Community Center isn\'t particularly enigmatic at all: Phoebe Bridgers and Conor Oberst started writing some songs together in Los Angeles, unclear what their final destination would be until they had enough good ones that a proper album seemed inevitable. Plus, the anonymity and secrecy allowed them to subvert any expectations that might come from news of high-profile singer-songwriter types teaming up. “We just realized that the songs were their own style and they didn\'t sound like either of us,” Bridgers tells Apple Music. “I don\'t think that they would have felt comfortable on one of my records or one of Conor\'s records. And even the band name—Conor came up with it and we didn\'t think about it as a real thing, and then people were like, \'Whoa, clearly it\'s this elaborate concept,\' and we\'re like, \'Really? Cool.\'” Let Bridgers and Oberst guide you through each track of their no-longer-enigmatic debut. **“Didn\'t Know What I Was in For”** Oberst: “When you sit down and write a song with someone, you kind of find out pretty fast—even if you\'re friends with them—if you gel on a creative level.” Bridgers: “I think it\'s really important to be able to have bad ideas in front of someone to create with them, and realizing I could do that with him was really important to our dynamic. We were able to tell each other what we actually thought about style and all that stuff, starting with that song.” **“Sleepwalkin’”** Oberst: “That was one of the first ones we started recording with a rhythm section, and I knew it was gonna be fun and actually be rock music, and I got excited for that.” Bridgers: “We did mostly real live takes of the band stuff, which was really fun. When I record my records, I overdub into oblivion because I like deleting and reworking and rethinking halfway through, so it\'s pretty different for me.” **“Dylan Thomas”** Oberst: “That was the last one we wrote, so we kind of had our method a little more dialed. It immediately felt like a good thing to put out there first, as far as people getting the whole concept quickly: that it\'s two singers and maybe more upbeat than people would think. I guess \[Dylan Thomas\] is a kind of antiquated reference for 2019, but he\'s always been one of my favorite poets.” **“Service Road”** Oberst: “That one is kind of like a heavy song, lyrically. I don\'t know if I would have been able to get to all that stuff without Phoebe\'s help—she\'s very empathetic in her writing.” Bridgers: “It\'s funny, I didn\'t really think about it like, \'Oh, helping Conor write something heavy\'; it was just immediately pretty familiar territory and I didn\'t really have to think twice about it.” Oberst: “It\'s cool when you find someone to write songs with, where a lot of it can go unsaid and you can be automatically on the same page without having to explain a bunch of stuff up front. \'Cause I feel like other times when I\'ve been in co-writing situations, if you\'re coming from super-different places, it takes a bunch of legwork to even get to a starting point.” **“Exception to the Rule”** Oberst: “That one changed the most from the demo to the actual recording. It really came into its own in the recording, with all the pulsing keyboard—that was not at all the way the demo was. That\'s always fun, when something changes in the recording process.” **“Chesapeake”** Bridgers: “I kind of started it as my own song with my friend Christian helping me out. We were getting together, ranting about music, and we were like, \'What if we wrote a song about what we think is stupid in music?\' and kind of ranted for hours over those chords. And then Conor, who was tripping on mushrooms, wanders into the room, like, \'Are you guys gonna just talk about writing this song or when are you gonna actually write it?\' We were kind of brushing him off, and then he started writing with us and then it immediately became real. And yeah, he gave us a run for our money on mushrooms.” **“My City”** Bridgers: “I think it\'s funny when people call LA \'this town.\' It\'s fucking so corny and funny, and the amount that I hear it is really disturbing. Like, \'Yeah, this town spits you out in a heartbeat.\' We started talking about that and then it became a lyric, and then weirdly kind of started being about Los Angeles. One of my favorite ways to write with Conor is just to go on a rant about something and then he spits out beautiful lyrics with whatever I said.” **“Forest Lawn”** Oberst: “Yeah, I guess there are a lot of LA references on this record. Phoebe would talk about when she was a teenager they would hang out and party and smoke weed in Forest Lawn. Every teenager in every town ends up going to a cemetery. Youth and reckless abandon amongst dead bodies—there\'s something kind of nice about that image to me.” **“Big Black Heart”** Bridgers: “I feel like—well, I know—that I subliminally stole the riff from a Tigers Jaw song. An early 2000s emo band...” Oberst: “She\'s like, \'I wanna email them and ask them if we can use it.\' And I was like, \'Damn, Phoebe, you\'re extremely ethical. I really appreciate your ethics.\'\" Bridgers: “They were very sweet, and they were like, \'What the fuck are you talking about? That\'s not stealing it.\'” Oberst: “I think Phoebe has a great scream and she never uses it, so I convinced her to bring that in, which is cool.” **“Dominos”** Oberst: “That\'s a cover. Taylor Hollingsworth is a songwriter from Birmingham, Alabama, a guy I\'ve played with a lot, that we both love as a person and as a musician. We just love that song. I had called him and got him to record those little samples on the phone of him talking. I kind of lied a little bit, like, \'Yeah, Taylor, I\'m making this sound collage for a song I\'m working on.\' When we finally played it for him, he was totally floored and got a little teary-eyed. He\'s like, \'I can\'t believe you guys recorded my song.\' So, that was really sweet.”

There’s a reason Taylor Swift sounds so confident and cool on *Lover*, her seventh album and the most free-spirited yet. She’s in *love*—pure, steady, starry-eyed, shout-it-from-the-rooftops love. Arriving 13 years after her eponymous debut album—and following a string of songs that sometimes felt like battle scars from public breakups and celebrity feuds—this project comes off clear-eyed, thick-skinned, and grown-up. It may be a sign that the 29-year-old has entered a new phase of her life: She’s now impressively private (she and her long-term boyfriend are rarely seen together in public), politically fired up (this album finds her fighting for queer and women’s rights), and eager to see the big picture (fans have speculated that the gut-wrenching “Soon You’ll Get Better” is about her mother’s battles with cancer). As a result, she’s never sounded stronger or more in control. She calls out dark-age bigots on the Pride anthem “You Need to Calm Down,” sends up the patriarchy on “The Man,” perfects flippant indifference on “I Forgot That You Existed,” and dares to sing her own praises on “ME!,” a duet with Brendon Urie of Panic! At the Disco. Tonally, these songs couldn’t be more different than 2017’s vengeful and self-conscious *Reputation*. Most of the album is baked in the atmospheric synths and ’80s drums favored by collaborator Jack Antonoff (“The Archer,” “Lover”). And yet some of the best moments are also the most surprising. “It’s Nice to Have a Friend” is daydreamy and delicate, illuminated with laidback strumming, twinkling trumpet, and high-pitched *ooh-ooh*s. And the percussive, playful “I Think He Knows” is a rollercoaster of a song, spiking and dipping from chatty whispers to breathy shout-singing in a matter of seconds.

If there is an overarching concept behind *uknowhatimsayin¿*, Danny Brown’s fifth full-length, it’s that it simply doesn’t have one. “Half the time, when black people say, ‘You know what I\'m sayin\',’ they’re never saying nothing,” Danny Brown tells Apple Music. “This is just songs. You don\'t have to listen to it backwards. You don\'t have to mix it a certain way. You like it, or you don’t.” Over the last decade, Brown has become one of rap’s most distinct voices—known as much for his hair and high register as for his taste for Adderall and idiosyncratic production. But with *uknowhatimsayin¿*, Brown wants the focus to lie solely on the quality of his music. For help, he reached out to Q-Tip—a personal hero and longtime supporter—to executive produce. “I used to hate it when people were like, ‘I love Danny Brown, but I can\'t understand what he\'s saying half the time,’” Brown says. “Do you know what I\'m saying now? I\'m talking to you. This isn\'t the Danny that parties and jumps around. No, this the one that\'s going to give you some game and teach you and train you. I\'ve been through it so you don\'t have to. I\'m Uncle Danny now.” Here, Uncle Danny tells you the story behind every song on the album. **Change Up** “‘Change Up’ was a song that I recorded while trying to learn how to record. I had just started to build the studio in my basement. I didn\'t know how to use Pro Tools or anything. It was really me just making a song to record. But I played it for Q-Tip and he lost his mind over it. Maybe he heard the potential in it, because now it\'s one of my favorite songs on the album as well. At first, I wasn\'t thinking too crazy about it, but to him, he was like, \'No, you have to jump the album off like this.\' It\'s hard not to trust him. He’s fuckin’ Q-Tip!” **Theme Song** “I made ‘Theme Song’ when I was touring for \[2016’s\] *Atrocity Exhibition*. My homeboy Curt, he’s a barber too, and I took him on tour with me to cut my hair, but he also makes beats. He brought his machine and he was just making beats on the bus. And then one day I just heard that beat and was like, ‘What you got going on?’ In our downtime, I was just writing lyrics to it. I played that for Q-Tip and he really liked that song, but he didn\'t like the hook, he didn\'t like the performance of the vocals. He couldn\'t really explain to me what he wanted. In the three years that we\'ve been working on this album, I think I recorded it over 300 times. I had A$AP Ferg on it from a time he was hanging out at my house when he was on tour. We did a song called \'Deadbeat\' but it wasn\'t too good. I just kept his ad libs and wrote a few lyrics, and then wrote a whole new song, actually.” **Dirty Laundry** “The original song was part of a Samiyam beat. He lives in LA, but every time he visits back home in Michigan he always stops over at my house and hangs out. And he was going through beats and he played me three seconds of that beat, and I guess it was the look on my face. He was like, \'You like that?\' and I was like, \'Yeah!\' I had to reform the way the song was written because the beats were so different from each other. Q-Tip guided me through the entire song: \'Say this line like this…\' or \'Pause right there...\' He pretty much just coached me through the whole thing. Couldn\'t ask for anybody better.” **3 Tearz (feat. Run the Jewels)** “I’m a huge fan of Peggy. We got each other\'s number and then we talked on the phone. I was like, \'Man, you should just come out to Detroit for like a week and let’s hang out and see what we do.\' He left a bunch of beats at my studio, and that was just one. I put a verse on, never even finished it. I was hanging out with EL-P and I was playing him stuff. I played that for him and he lost his mind. El got Mike on it and they laced it. Then Q-Tip heard it and he\'s like, \'Aww, man!\' He kind of resequenced the beat and added the organs. That was tight to see Tip back there jamming out to organs.” **Belly of the Beast (feat. Obongjayar)** “I probably had that beat since \[2011’s\] *XXX*. That actual rap I wrote for \[2013’s\] *Old*, but it was to a different beat. Maybe it was just one of those dry times. I set it to that beat kind of just playing around. Then Steven \[Umoh\] heard that—it was totally unfinished, but he was like, ‘Yo, just give it to me.’ He took it and then he went back to London and he got Obongjayar down there on it. The rest was history.” **Savage Nomad** “Actually, Q-Tip wanted the name of the album to be *Savage Nomad*. Sometimes you just make songs to try to keep your pen sharp, you know? I think I was just rapping for 50 bars straight on that beat, didn\'t have any direction. But Q-Tip resequenced it. I think Tip likes that type of stuff, when you\'re just barring out.” **Best Life** “That was when me and Q-Tip found our flip. We were making songs together, but nothing really stood out yet. I recorded the first verse but I didn\'t have anything else for it, and I sent Tip a video of me playing it and he called me back immediately like, \'What the fuck? You have to come out here this weekend.\' Once we got together, I would say he kind of helped me with writing a little bit, too. I ended up recording another version with him, but then he wanted to use the original version that I did. He said it sounded rawer to him.” **uknowhatimsayin¿ (feat. Obongjayar)** “A lot of time you put so much effort when you try too hard to say cool shit and to be extra lyrical. But that song just made itself one day. I really can\'t take no credit because I feel like it came from a higher power. Literally, I put the beat on and then next thing I know I probably had that song done at five minutes. I loved it so much I had to fight for it. I can\'t just be battle-rapping the entire album. You have to give the listeners a break, man.” **Negro Spiritual (feat. JPEGMAFIA)** “That was when Peggy was at my house in Detroit, that was one of the songs we had recorded together. I played it for Flying Lotus. He’s like, \'Man, you got to use this,\' and I was like, \'Hey, if you can get Q-Tip to like it, then I guess.\' At the end of the day, it\'s really not on me to say what I\'m going to use, what I\'m not going to use. I didn\'t even know it was going to be on the album. When we started mixing the album, and I looked, he had like a mood board with all the songs, and \'Negro Spiritual\' was up there. I was like, \'Are we using that?\'” **Shine (feat. Blood Orange)** “The most down-to-earth one. I made it and I didn\'t have the Blood Orange hook, though. Shout out to Steven again. He went and worked his magic. Again, I was like, \'Hey, you\'re going to have to convince Q-Tip about this song.\' Because before Blood Orange was on it, I don\'t think he was messing with it too much. But then once Blood Orange got on it, he was like, \'All right, I see the vision.\'” **Combat** “Literally my favorite song on the album, almost like an extra lap around a track kind of thing. Q-Tip told me this story of when he was back in the late ’80s: They\'d play this Stetsasonic song in the Latin Quarter and people would just go crazy and get to fighting. He said one time somebody starts cutting this guy, cutting his goose coat with a razor, and \[Tip\] was like, \'You could just see the feathers flying all over the air, people still dancing.\' So we always had this thing like, we have to make some shit that\'s going to make some goose feathers go up in the air. That was the one right there. That was our whole goal for that, and once we made it, we really danced around to that song. We just hyped up to that song for like three days. You couldn\'t stop playing it.”

“It feels right that our fourth album is not 10, 11 songs,” Vampire Weekend frontman Ezra Koenig explains on his Beats 1 show *Time Crisis*, laying out the reasoning behind the 18-track breadth of his band\'s first album in six years. “It felt like it needed more room.” The double album—which Koenig considers less akin to the stylistic variety of The Beatles\' White Album and closer to the narrative and thematic cohesion of Bruce Springsteen\'s *The River*—also introduces some personnel changes. Founding member Rostam Batmanglij contributes to a couple of tracks but is no longer in the band, while Haim\'s Danielle Haim and The Internet\'s Steve Lacy are among the guests who play on multiple songs here. The result is decidedly looser and more sprawling than previous Vampire Weekend records, which Koenig feels is an apt way to return after a long hiatus. “After six years gone, it\'s a bigger statement.” Here Koenig unpacks some of *Father of the Bride*\'s key tracks. **\"Hold You Now\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “From pretty early on, I had a feeling that\'d be a good track one. I like that it opens with just acoustic guitar and vocals, which I thought is such a weird way to open a Vampire Weekend record. I always knew that there should be three duets spread out around the album, and I always knew I wanted them to be with the same person. Thank God it ended up being with Danielle. I wouldn\'t really call them country, but clearly they\'re indebted to classic country-duet songwriting.” **\"Rich Man\"** “I actually remember when I first started writing that; it was when we were at the Grammys for \[2013\'s\] *Modern Vampires of the City*. Sometimes you work so hard to come up with ideas, and you\'re down in the mines just trying to come up with stuff. Then other times you\'re just about to leave, you listen to something, you come up with a little idea. On this long album, with songs like this and \'Big Blue,\' they\'re like these short-story songs—they\'re moments. I just thought there\'s something funny about the narrator of the song being like, \'It\'s so hard to find one rich man in town with a satisfied mind. But I am the one.\' It\'s the trippiest song on the album.” **\"Married in a Gold Rush\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “I played this song for a couple of people, and some were like, \'Oh, that\'s your country song?\' And I swear, we pulled our hair out trying to make sure the song didn\'t sound too country. Once you get past some of the imagery—midnight train, whatever—that\'s not really what it\'s about. The story is underneath it.” **\"Sympathy”** “That\'s the most metal Vampire Weekend\'s ever gotten with the double bass drum pedal.” **\"Sunflower\" (feat. Steve Lacy)** “I\'ve been critical of certain references people throw at this record. But if people want to say this sounds a little like Phish, I\'m with that.” **\"We Belong Together\" (feat. Danielle Haim)** “That\'s kind of two different songs that came together, as is often the case of Vampire Weekend. We had this old demo that started with programmed drums and Rostam having that 12-string. I always wanted to do a song that was insanely simple, that was just listing things that go together. So I\'d sit at the piano and go, \'We go together like pots and pans, surf and sand, bottles and cans.\' Then we mashed them up. It\'s probably the most wholesome Vampire Weekend song.”

From the outset of his fame—or, in his earliest years as an artist, infamy—Tyler, The Creator made no secret of his idolization of Pharrell, citing the work the singer-rapper-producer did as a member of N.E.R.D as one of his biggest musical influences. The impression Skateboard P left on Tyler was palpable from the very beginning, but nowhere is it more prevalent than on his fifth official solo album, *IGOR*. Within it, Tyler is almost completely untethered from the rabble-rousing (and preternaturally gifted) MC he broke out as, instead pushing his singing voice further than ever to sound off on love as a life-altering experience over some synth-heavy backdrops. The revelations here are mostly literal. “I think I’m falling in love/This time I think it\'s for real,” goes the chorus of the pop-funk ditty “I THINK,” while Tyler can be found trying to \"make you love me” on the R&B-tinged “RUNNING OUT OF TIME.” The sludgy “NEW MAGIC WAND” has him begging, “Please don’t leave me now,” and the album’s final song asks, “ARE WE STILL FRIENDS?” but it’s hardly a completely mopey affair. “IGOR\'S THEME,” the aforementioned “I THINK,” and “WHAT\'S GOOD” are some of Tyler’s most danceable songs to date, featuring elements of jazz, funk, and even gospel. *IGOR*\'s guests include Playboi Carti, Charlie Wilson, and Kanye West, whose voices are all distorted ever so slightly to help them fit into Tyler\'s ever-experimental, N.E.R.D-honoring vision of love.

What happens when the reigning queen of bubblegum pop goes through a breakup? Exactly what you’d think: She turns around and creates her most romantic, wholehearted, blissed-out work yet. Written with various pop producers in LA (Captain Cuts), New York (Jack Antonoff), and Sweden, as well as on a particularly formative soul-searching trip to the Italian coast, Jepsen’s fourth album *Dedicated* is poptimism at its finest: joyous and glitzy, rhythmic and euphoric, with an extra layer of kitsch. It’s never sad—that just isn’t Jepsen—but the “Call Me Maybe” star *does* get more in her feelings; songs like “No Drug Like Me” and “Right Words Wrong Time” aren\'t about fleeing pain so much as running to it. As Jepsen puts it on the synth ballad “Too Much,” she’d do anything to get the rush of being in love, even if it means risking heartache again and again. “Party for One,” the album’s standout single, is an infectious, shriek-worthy celebration of being alone that also acknowledges just how difficult that can be: “Tried to let it go and say I’m over you/I’m not over you/But I’m trying.”

Calling an album *All My Heroes Are Cornballs* reads immediately as a brilliant indictment of celebrity culture, but what about when said whistleblower exists—to a steadily increasing number of fans—as a hero himself? “Some people *might* see me as a hero, and I *might* be a cornball to some people,” JPEGMAFIA tells Apple Music. “It can be turned on the person who created it. I’m not infallible or trying to say I\'m not a cornball. I\'m just saying, *all my heroes are cornballs*.” The album and declaration come just a year after *Veteran*, the project that brought the Brooklyn-born Baltimore MC and producer his most visibility. So what does Peggy do with all of the eyes and ears he now has at his disposal? The same thing he’s done from the beginning of his music-making career: tell people about themselves, whether they’re ready to hear it or not. Read on as JPEGMAFIA talks Apple Music through some of *All My Heroes Are Cornballs*\' more provocative selections. **“Beta Male Strategies”** “Going back to the title \[of the album\], I\'m letting you know off the bat, I\'m a false prophet. Don\'t get your hopes up, because everybody\'s human. I might put a MAGA hat on one day. It\'s unlikely, but you don\'t know, so it\'s just like, \'I\'m a false prophet/Bringin’ white folks this new religion/My fans need new addictions.’ It\'s not like I\'m the first artist to struggle with notoriety or anything like that. I\'m just framing it through my lens. I\'ve been underground and poor for years, so this is hilarious to me.\" **“Grimy Waifu”** \"‘Grimy Waifu’ is actually about a gun. They probably changed it now because the times are different, but \[when I was in the military\] they framed it like, ‘This is your gun. This is your girl. You gotta sleep with her…’ In the female squad, they probably did the opposite: ‘This is your n\*gga. Bring your n\*gga to bed.’ It\'s framed like it\'s a love song, but it\'s a song about me and my rifle.” **“PRONE!”** “The intention behind ‘PRONE!’ was to make a punk song with no instruments. This is a song that\'s made completely digitally. I feel like people in other genres, specifically rock—I go back to rock a lot because rock spends a lot of time trashing rap—a lot of people in rock had this idea that rappers aren\'t talented. In my opinion, we\'re fucking better than them. We\'re better writers, we think deeper, our concepts are harder—rap evolves faster and at a higher rate than any other genre. The only difference is rap has a bunch of n\*ggas doing it and rock has a bunch of white boys doing it. I made this song just to be like, \'I can do what you do and I don\'t even have to learn how to play drums. I\'m in here playing with my hands, bitch! And I can still do this shit.\'” **“All My Heroes Are Cornballs”** “Structurally it makes no sense, but thematically it’s the most straightforward song on here: rapping about the idea that the people we’re supposed to look up to are corny as shit. I feel like this one sums up everything, because I’m not doing anything weird vocally, I’m singing and then I’m rapping, but the execution of it doesn’t make sense: It starts off one way and I’m singing, and there’s like a long-ass hook where I don’t actually say anything and then there’s like a verse, and then the other hook that comes in is different, and then the end is like my homie ordering a bacon smokehouse meal. I came very close to cutting it, actually.” **“Thot Tactics”** “I actually wrote the rap first and that melody I had, and when I was writing the song, I would hum that melody over the part where it is now, and in the back of my head I told myself I’m gonna write something to that later, but I just sat down one day and I was like, nah, n\*gga, this is it! This is the song. I can’t hire En Vogue to do this, I gotta do it myself. I’m a DIY n\*gga. I want some shit done, I do it my muthafuckin’ self!” **“BasicBitchTearGas”** “I always told myself that one day I’d do a cover of ‘No Scrubs,’ and I just wanted to make that a reality. Bucket-list-type shit. I love this song, man. It’s one of the best songs ever written. And I really like recontextualizing songs that mean a lot to people, like pop music, because it exposes the reality of these songs. That these songs are *excellent*—regardless of how popular they are and regardless of the narrative that’s been built around some of these songs, these are excellently written, beautiful songs, and I wanna take time to appreciate them.” **“Papi I Missed U”** “I wanted to put something on record that was completely, exactly how the fuck I felt. There was no trolling, this is how I feel. And I want people to hear that and I want people to know that there\'s no fucking answer \[for it\]. I don\'t like you and there\'s nothing you can do about it. That\'s how they made my black ass feel for my whole fucking life. So when I say some shit like \'I hate old white n\*ggas, I\'m prejudiced…\' What now? I said it, I meant it, it is what it is. They don\'t give a fuck about our feelings, I don\'t give a fuck about theirs. It\'s returning all the shit they always give to me and give to black people. All this shit these racist types give to people of color, I\'m giving it right back to them and I\'m watching them scatter because they can\'t fucking take it.”

All tracks produced, written, mixed and mastered by JPEGMAFIA "Rap Grow Old & Die" contains additional production from Vegyn Album Artwork Design by Alec Marchant Recorded alone @ a space for me This album is really a thank you to my fans tbh. I started and finished it In 2018, mixed and mastered it in 2019 right after the Vince tour. I don’t usually work on something right after I release a project. But Veteran was the first time in my life I worked hard on something, and it was reciprocated back to me. So I wanted thank my people. And make an album that I put my my whole body into, as in all of me. All sides of Me baby. Not just a few. This the most ME album I’ve ever made in my life, Im trying to give y’all niggas a warm album you can live in and take a nap in maybe start a family and buy some Apple Jacks to. I’ve removed restrictions from my head and freed myself of doubt musically. I would have removed half this shit before but naw fuck it. Y’all catching every bit of this basic bitch tear gas. This is me, all me, in full form nigga, and this formless piece of audio is my punk musical . I hope it disappoints every last one of u. 💕💕

It\'s hard to imagine Bruce Springsteen describing a project of his as a concept album—too much prog baggage, too much expectation of some big, grand, overarching *story*. But nothing he\'s done across five decades as one of rock\'s most accomplished storytellers has had the singular, specific focus and locus, lyrically and musically, as this long-gestating solo effort—a lush meditation on the landscape of the western United States and the people who are drawn there, or got stuck there. Neither a bare-bones acoustic effort like *Nebraska* nor a fully tricked-out E Street Band affair, this set of 13 largely subdued character-driven songs (his first new ones since 2014\'s *High Hopes*, following five years immersed in memoir) is ornamented with strings and horns and slide guitar and banjo that sound both dusty and Dusty. They trade in the most familiar of American iconography—trains, hitchhikers, motels, sunsets, diners, Hollywood, and, of course, wild horses—but aren\'t necessarily antiquated; the clichés are jumping-off points, aiming for timelessness as much as nostalgia. The battered stuntman of “Drive Fast” could be licking, and cataloging, his wounds in 1959 or 2019. As convulsive and pivotal as the current moment may feel, restlessness and aimlessness and disenfranchisement are evergreen, and the songs are built to feel that way. In true Springsteen fashion, the personal is elevated to the mythical.

In 2016’s *Private Energy*, Roberto Carlos Lange, a.k.a. Helado Negro, celebrated his identity while highlighting themes like racially targeted enforcement and gender fluidity. The Brooklyn-based singer-producer’s follow-up, *This Is How You Smile*, allows him to wind down and find his center. *Smile* is by turns more self-reflective, a vivid reverie of personal memories bedded in delicate acoustic strums and atmospheric dreamscapes. Lange\'s articulate, compassionate voice softens the album\'s dense arrangements (which are interspersed with field recordings and ambient interludes). On “País Nublado,” a balmy bossa nova groove ambles against Lange’s pithy haikus. Serene piano strokes lead the way over his soulful, whispered baritone on both “Running” and “Please Won’t Please.” “Seen My Aura” is more effervescent by comparison, but just as chill—a lysergic funk jam where Lange’s naturalistobservations take flight.

Helado Negro returns with This Is How You Smile, an album that freely flickers between clarity and obscurity, past and present geographies, bright and unhurried seasons. Miami-born, New York-based artist Roberto Carlos Lange embraces a personal and universal exploration of aura – seen, felt, emitted – on his sixth album and second for RVNG Intl.

SASAMI (Sasami Ashworth) has been making music in almost every way possible for the last decade, and between playing keys, bass, guitar within Cherry Glazerr and Dirt Dress; contributing vocal, string, and horn arrangements to studio albums by the likes of Vagabon, Curtis Harding, Wild Nothing, and Hand Habits; arranging for films and commercials; and even playing French horn in an orchestra - she has gained a reputation as an all-around musical badass. Now taking a turn to focus on her own music, SASAMI's self-titled debut will be out March 2019 on Domino. pre-order the LP at www.dominomusic.com/releases/sasami/sasami-lp-mart-exclusive