Please note: prices do not include VAT/sales tax (where applicable). Erratics & Unconformities is the first album by Craven Faults. It follows three EPs: Netherfield Works, Springhead Works and Nunroyd Works. Real-time journeys across decades and continents, and swathes of post-industrial northern Britain. The journey on Erratics & Unconformities picks up where Netherfield Works left off. We take the canal towpath out of the city. We fork north shortly afterwards. Is this where it started? The terrain gradually becomes more rugged. Familiar. Wild. Evidence of human activity is less immediate in this glacial landscape. It’s there if you seek it. But easy to ignore. If you listen carefully, you can still hear the weight of the ice-sheet carving its way through the rock. Scepter Studios, Manhattan. September 1967. Vox amplifiers driven to within an inch of their lives. An insistent rhythm. Familiar. Wild. We head across the city to 30th Street Studios a year later. More refined. Capturing a moment four years after its inception. We call into Command Studios in London on an evening in March 1972 before the pace drops. A moment to take in our surroundings. Music born in New York that has travelled beyond our solar system. A sense of weightlessness. We go as far back as 1906. Central Park. Tone poems underappreciated at the time - a visionary. We pay a visit to the village of Wümme in northern Germany. Forward momentum. There’s a nod to the rhythm of the loom. The studio building echoes with its own history by way of an early 70s Elka drum machine. We come to Van Gelder Studio in 1962 by a process of addition and elimination. We stay for the next three years. We’re also put in mind of the time we spent at Dierks Studios in 1972. A treasured record bought at sixteen. It takes time to reveal itself completely. Perhaps it never does. It would be lost now. 8th January 2013 – 19:16 – Farfisa drone through diode filter and phaser – 26 mins 38 seconds Everything in its own time. The output from the old textile mill Craven Faults calls home is no longer as linear as it once was. There was no clear start point for the project, rather simply rediscovering the joy in experimentation with no material goals. Some of the recordings that make up Erratics & Unconformities go back almost seven years. Tracks have come and gone in that time. They don’t leave until they’ve undertaken a stringent quality control process. It started slowly, but has picked up momentum in the last eighteen months. Recorded and re-recorded to the correct level of imperfection, and then left to breathe. Mixed and re-mixed. Carefully compiled when the time was right. 3rd July 2019 – 12:34 – Mixdown The journey is just as important as the destination.

McDermott is releasing Roped In, a gorgeous, intimate, and often spare album that pulls back from the collaborative nature established on Going Steady for a collection of fragile drone pieces anchored by McDermott’s intricate but direct guitar playing and haunting pedal steel work from Portland, Oregon’s Barry Walker. Featuring contributions from William Tyler on guitar and Mary Lattimore on harp.

“Life seems to provide no end of things to explore without too much investigation,” Laura Marling tells Apple Music. The London singer-songwriter is discussing how, after six albums (three of which were Mercury Prize-nominated), she found the inspiration needed for her seventh, *Song For Our Daughter*. One thing which proved fruitful was turning 30. In an evolution of 2017’s exquisite rumination on womanhood *Semper Femina*, growing, as she says, “a bit older” prompted Marling to consider how she might equip her her own figurative daughter to navigate life’s complexities. “In light of the cultural shift, you go back and think, ‘That wasn’t how it should have happened. I should have had the confidence and the know-how to deal with that situation in a way that I didn’t have to come out the victim,’” says Marling of the album’s central message. “You can’t do anything about it, obviously, so you can only prepare the next generation with the tools and the confidence \[to ensure\] they \[too\] won’t be victims.” This feeling reaches a crescendo on the title track, which sees Marling consider “our daughter growing old/All of the bullshit that she might be told” amid strings that permeate the entire record. While *Song for Our Daughter* is undoubtedly a love letter to women, it is also a deeply personal album where whimsical melodies (“Strange Girl”) collide with Marling at her melancholic best (the gorgeously sparse “Blow by Blow”—a surprisingly honest chronicle of heartbreak—or the exceptional, haunting “Hope We Meet Again”). And its roaming nature is exactly how Marling wanted to soundtrack the years since *Semper Femina*. “There is no cohesive narrative,” she admits. “I wrote this album over three years, and so much had changed. Of course, no one knows the details of my personal life—nor should they. But this album is like putting together a very fragmented story that makes sense to me.” Let Marling guide you through that story, track by track. **Alexandra** “Women are so at the forefront of my mind. With ‘Alexandra,’ I was thinking a lot about the women who survive the projected passion of so-called ‘great men.’ ‘Alexandra’ is a response to Leonard Cohen’s ‘Alexandra Leaving,’ but it’s also the idea that for so long women have had to suffer the very powerful projections that people have put on them. It’s actually quite a traumatizing experience, I think, to only be seen through the eyes of a man’s passion; just as a facade. And I think it happens to women quite often, so in a couple of instances on this album I wanted to give voice to the women underneath all of that. The song has something of Crosby, Stills & Nash about it—it’s a chugging, guitar-riffy job.” **Held Down** “Somebody said to me a couple of years ago that the reason why people find it hard to attach to me \[musically\] is that it\'s not always that fun to hear sad songs. And I was like, ‘Oh, well, I\'m in trouble, because that\'s all I\'ve got!’ So this song has a lightness to it and is very light on sentiment. It’s just about two people trying to figure out how to not let themselves get in the way of each other, and about that constant vulnerability at the beginning of a relationship. The song is almost quite shoegazey and is very simple to play on the guitar.” **Strange Girl** “The girl in this song is an amalgamation of all my friends and I, and of all the things we\'ve done. There’s something sweet about watching someone you know very well make the same mistakes over and over again. You can\'t tell them what they need to know; they have to know it themselves. That\'s true of everyone, including myself. As for the lyrics about the angry, brave girl? Well, aren’t we all like that? The fullness and roundness of my experience of women—the nuance and all the best and worst things about being a complicated little girl—is not always portrayed in the way that I would portray it, and I think women will recognize something in this song. My least favorite style of music is Americana, so I was conscious to avoid that sound here. But it’s a lovely song; again, it has chords which are very Crosby, Stills & Nash-esque.” **Only the Strong** “I wanted the central bit of the album to be a little vulnerable tremble, having started it out quite boldly. This song has a four-beat click in it, which was completely by accident—it was coming through my headphones in the studio, so it was just a happy accident. The strings on this were all done by my bass player Nick \[Pini\] and they are all bow double-bass strings. They\'re close to the human voice, so I think they have a specific, resonant effect on people. I also went all out on the backing vocals. I wanted it to be my own chorus, like my own subconscious backing me up. The lyric ‘Love is a sickness cured by time\' is actually from a play by \[London theater director\] Robert Icke, though I did ask his permission to use it. I just thought that was the most incredible ointment to the madness of infatuation.” **Blow by Blow** “I wrote this song on the piano, but it’s not me playing here—I can\'t play the piano anywhere near as well as my friend Anna here. This song is really straightforward, and I kind of surprised myself by that. I don\'t like to be explicit. I like to be a little bit opaque, I guess, in the songwriting business. So this is an experiment, and I still haven’t quite made my mind up on how I feel about it. Both can exist, but I think what I want from my music or art or film is an uncanny familiarity. This song is a different thing for me, for sure—it speaks for itself. I’d be rendering it completely naked if I said any more.” **Song for Our Daughter** “This song is kind of the main event, in my mind. I actually wrote it around the time of the Trayvon Martin \[shooting in 2012\]. All these young kids being unarmed and shot in America. And obviously that\'s nothing to do with my daughter, or the figurative daughter here, but I \[was thinking about the\] institutional injustice. And what their mothers must be feeling. How helpless, how devastated and completely unable to have changed the course of history, because nothing could have helped them. I was also thinking about a story in Roman mythology about the Rape of Lucretia. She was the daughter of a nobleman and was raped—no one believed her and, in that time, they believed that if you had been ‘spoilt’ by something like that, then your blood would turn black. And so she rode into court one day and stabbed herself in the heart, and bled and died. It’s not the cheeriest of analogies, but I found that this story that existed thousands of years ago was still so contemporary. The strings were arranged by \[US instrumentalist, arranger, and producer\] Rob Moose, and when he sent them to me he said, ‘I don\'t know if this is what you wanted, but I wanted to personify the character of the daughter in the strings, and help her kind of rise up above everything.’ And I was like, ‘That\'s amazing! What an incredible, incredible leap to make.’ And that\'s how they ended up on the record.” **Fortune** “Whenever I get stuck in a rut or feel uninspired on the guitar, I go and play with my dad, who taught me. He was playing with this little \[melody\]—it\'s just an E chord going up the neck—so I stole it and then turned it into this song. I’m very close with my sisters, and at the time we were talking and reminiscing about the fact that my mother had a ‘running-away fund.’ She kept two-pence pieces in a pot above the laundry machine when we were growing up. She had recently cashed it in to see how much money she had, and she had built up something like £75 over the course of a lifetime. That was her running-away fund, and I just thought that was so wonderfully tragic. She said she did it because her mother did it. It was hereditary. We are living in a completely different time, and are much closer to equality, so I found the idea of that fund quite funny.” **The End of the Affair** “This song is loosely based on *The End of the Affair* by Graham Greene. The female character, \[Sarah\], is elusive; she has a very secret role that no one can be part of, and the protagonist of the book, the detective \[Maurice Bendrix\], finds it so unbearably erotic. He finds her secretness—the fact that he can\'t have her completely—very alluring. And in a similar way to ‘Alexandra Leaving,’ it’s about how this facade in culture has appeared over women. I was also drawing on my own experience of great passions that have to die very quietly. What a tragedy that is, in some ways, to have to bear that alone. No one else is obviously ever part of your passions.” **Hope We Meet Again** “This was actually the first song we recorded on the album, so it was like a tester session. There’s a lot of fingerpicking on this, so I really had to concentrate, and it has pedal steel, which I’m not usually a fan of because it’s very evocative of Americana. I originally wrote this for a play, *Mary Stuart* by Robert Icke, who I’ve worked with a lot over the last couple of years, and adapted the song to turn it back into a song that\'s more mine, rather than for the play. But originally it was supposed to highlight the loneliness of responsibility of making your own decisions in life, and of choosing your own direction. And what the repercussions of that can sometimes be. It\'s all of those kind of crossroads where deciding to go one way might be a step away from someone else.” **For You** “In all honesty, I think I’m getting a bit soft as I get older. And I’ve listened to a lot of Paul McCartney and it’s starting to affect me in a lot of ways. I did this song at home in my little bunker—this is the demo, and we just kept it exactly as it was. It was never supposed to be a proper song, but it was so sweet, and everyone I played it to liked it so much that we just stuck it on the end. The male vocals are my boyfriend George, who is also a musician. There’s also my terrible guitar solo, but I left it in there because it was so funny—I thought it sounded like a five-year-old picking up a guitar for the first time.”

Laura Marling’s exquisite seventh album Song For Our Daughter arrives almost without pre-amble or warning in the midst of uncharted global chaos, and yet instantly and tenderly offers a sense of purpose, clarity and calm. As a balm for the soul, this full-blooded new collection could be posited as Laura’s richest to date, but in truth it’s another incredibly fine record by a British artist who rarely strays from delivering incredibly fine records. Taking much of the production reins herself, alongside long-time collaborators Ethan Johns and Dom Monks, Laura has layered up lush string arrangements and a broad sense of scale to these songs without losing any of the intimacy or reverence we’ve come to anticipate and almost take for granted from her throughout the past decade.

Caribou’s Dan Snaith is one of those guys you might be tempted to call a “producer” but at this point is basically a singer-songwriter who happens to work in an electronic medium. Like 2014’s *Our Love* and 2010’s *Swim*, the core DNA of *Suddenly* is dance music, from which Snaith borrows without constraint or historical agenda: deep house on “Lime,” UK garage on “Ravi,” soul breakbeats on “Home,” rave uplift on “Never Come Back.” But where dance tends to aspire to the communal (the packed floor, the oceanic release of dissolving into the crowd), *Suddenly* is intimate, almost folksy, balancing Snaith’s intricate productions with a boyish, unaffected singing style and lyrics written in nakedly direct address: “If you love me, come hold me now/Come tell me what to do” (“Cloud Song”), “Sister, I promise you I’m changing/You’ve had broken promises I know” (“Sister”), and other confidences generally shared in bedrooms. (That Snaith is singing a lot more makes a difference too—the beat moves, but he anchors.) And for as gentle and politely good-natured as the spirit of the music is (Snaith named the album after his daughter’s favorite word), Caribou still seems capable of backsliding into pure wonder, a suggestion that one can reckon the humdrum beauty of domestic relationships and still make time to leave the ground now and then.

A Powys trio whose free-spirited invention and exuberant intensity flows through experimental pop: hypnotic, exhilarating and defiantly unique. The Welsh band Islet return with the release of their long-awaited new album. 'Eyelet' was recorded at home tucked away in the hills of rural Mid Wales. It took form the months following the birth of band members Emma and Mark Daman Thomas’ second child and the death of fellow band member Alex Williams’ mother. Alex came to live with Emma and Mark, and the band enlisted Rob Jones (Pictish Trail, Charles Watson) to produce. Winner of 2020 Neutron Prize www.godisinthetvzine.co.uk/2020/09/30/news-islet-win-the-neutron-prize-2020/ Shortlisted for Welsh Music Prize 2020

The West Midlands-born and London-based electronic duo Delmer Darion (comprising Oliver Jack and Tom Lenton) announce their debut album ‘Morning Pageants’ will be released on the 16th October via Practise Music. Their debut album has been five years in the making: a sprawling, industrial ten-track account of the death of the devil, inspired by a line in the Wallace Stevens poem ‘Esthétique du Mal’: “The death of Satan was a tragedy for the imagination.” A vast aural landscape is covered from the opening melodies coded in the constructed language of Solresol. When sequenced together, ‘Morning Pageants’ is shrouded in the same intricate noise of self-sampling and tape degradation. De-centred rhythmic assemblies of analogue drum machines play through a series of guitar pedals, thunderous bass swells from a self oscillating filter feedback patch, and folk songs dissolve into thin air. The artwork for Morning Pageants was designed by Oliver, based from a series of 16th Century prints called “The Dance of Death” by Hans Holbein, depicting different people being led away by Death. Recreating one of the prints, he replaced the figure being led away with an original drawing of Satan. The final artwork is printed on Nepalese Lokta paper, a waxy yellow paper that has been used for lots of sacred texts. Even if you’re not following the descent of the devil step by step through their unspooling archives, you’ll have little chance not to be transfixed.

“It was just a big experiment, the process of making this album,” Tom Misch tells Apple Music. “There wasn\'t too much thought process behind it.” On this freewheeling passion project born of breakneck jam sessions, songwriter and producer Misch unites with virtuoso jazz drummer Yussef Dayes for a sound that fluidly combines elements of jazz, hip-hop, and electronica. Freddie Gibbs—the album\'s sole vocal feature—adds menace on “Nightrider,” “The Real” riffs on Dilla-era soul chops, and “Sensational” throws a nod to the swirling solos of percussive greats. This wickedly unrestrained vision has landed the Southeast London pair a maiden release on the pioneering jazz imprint Blue Note Records. “It\'s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be associated,” says Dayes, reeling off Blue Note luminaries including Coltrane, Hancock, and Blakey. “It makes you want to work harder, because those guys, they were on another level.” The process also prompted a bout of déjà vu for Misch. “I have this memory of seeing this guy on drums, like, 15 years ago in a talent show in this school, and thinking, ‘This guy\'s insane.’ When we were working on the album, I was like, \'Shit. Are you that dude who...\' So it was kind of a weird one,” he says. “I was always performing at school,” Dayes admits. “It\'s a way for me to express what I\'m feeling. A chance for me to connect with the people that are into the music and give them some energy and vice versa. But with us two collaborating, coming from two different fields, we have to meet in the middle. It\'s give and take from both of us.” Here, the pair run through the album track by track. **What Kinda Music** Tom Misch: “This was one of the first tracks we did. I had a session with Loyle Carner in summer 2018. We were recording and I called up Yussef to try some drums on this track I was producing. He came down and recorded the drums for what is now ‘Angel,’ on Loyle\'s \[*Not Waving, But Drowning*\] album. So, he left the studio, and then Yussef and I were there for the rest of the day. The origins of \'What Kinda Music,\' \'The Real,\' and \'Storm Before the Calm\' came from that day. It was just a crazy day.” Yussef Dayes: “From there, we realized it wasn\'t a one-track collaboration. We felt like it could be a tape or something. Sometimes you collaborate and it doesn’t quite click, but if from the get-go it\'s clicking and it\'s sounding good, you know there\'s something there. It\'s a unique sound this track; I felt like that was a fresh sound that neither me or Tom had explored completely, so I wanted to see us start with the off-kilter thing.” **Festival** TM: “This was a day with me, Yussef, and a bassist, Tom Dressler. We recorded a bunch of stuff over the three days. And the basis for this song was something we recorded there. I knew I liked the vibe, but I wanted to sing on it, and it took a while to execute the vocals. It\'s about when you\'re younger, you have this natural presence as in you\'re in the *now*, generally, when you\'re young. And then you kind of lose that as you grow older. It\'s saying how you still have that, that you\'re still able to be present. Yussef was like, ‘I want to call it \"Festival Tune.\"’ So I was like, \'Fair enough.\'” YD: “This is a big tune. It sounds like it could score a David Attenborough documentary, you know? On something about the planet, for the real earth people. It\'s just emphatic. I can imagine this being performed at Glastonbury; I can hear people singing along.” **Nightrider (feat. Freddie Gibbs)** TM: “The vibe of the instrumental felt kind of woozy, a bit hazy. And I remember going on the *Knight Rider* trailer on YouTube, playing it with the music, and it was just a perfect combination. We knew we wanted to get a rapper on the record, and I wrote down a list of people that we like. I\'m just going through the list and Yussef said, \'Let\'s do Freddie Gibbs.\' I\'m really chuffed about getting him because I\'m a big fan of Freddie. It really adds a different vibe to the record.” YD: “We recorded this with a good friend of mine, \[producer and engineer\] Miles James. We were just were rocking. We recorded the drums and bass down in Eastbourne and then we came back and produced it up. It\'s the same thing again. My job is...my drumbeat should be able to give everybody the music that they hear on top of it. I just was like, \'Yeah, we\'ve got to get Freddie on this, man.\' I\'d been in contact with him already, just sending him beats, and I just thought this needed that extra, that little touch, man.” **Tidal Wave** TM: “You can just hear the rawness of it, the moments where we\'re just shouting and stuff. Really low in the mix you can hear me shout out, \'All right, now it\'s like a chorus, so play drumming.\' Because at that point, even though we were just jamming, I knew it had potential to be a song.” YD: “This was me, Tom, and Rocco Palladino on bass. We set up, pressed record, and just jammed some ideas. We did that twice on this record, and this was the second time, just three hours worth of music. It was just one of those days, man, just light up the incense and catch a vibe, man. Not even thinking. I was just trying to do some different stuff on the drums, different cymbals that I hadn\'t used before, some wood blocks and stuff, and try to switch up a bit.” **Sensational** TM: “This represents a bit of the rawness on the record. It’s just a little cut from a day of jamming, a little insight, and I hit up Tobie Tripp, he’s an amazing strings player. I got him to lay some violin on it and double up the guitar part.” YD: “I wanted to make sure there\'s skits and interludes and off-cuts on the records, because all my favorite albums, when I listen to the Fugees or D\'Angelo, those albums play with skits in between that tie it together. I think \'Sensational\' is one of those things—it\'s like some country-western shit, sort of, like some Django shit. This is, I suppose, my bag, man. This kinda shit. I\'d love to get a rapper on this for a remix maybe.” **The Real** TM: “For me, this was kind of like me going back to being a beatmaker. The drums are from that day I was in the studio with Loyle, and then I went home and I started chopping some Aretha Franklin. That\'s what I like about this one. It\'s kind of me going back to what I used to do.” YD: “This is definitely one of my favorites. It\'s from the same day as \'Angel.\' This is one of the beats from that day, and I recorded the drums and then I forgot about this. Tom went away, he put the Aretha sample to it, processed the drums a bit, and came back later. I was like, \'Wow, what\'s this? I don\'t even remember this.\' I love that kind of stuff. I love gospel music. That\'s a big influence to me, man. That\'s a dream of mine, to record with a live choir at some point, and obviously Aretha Franklin, that\'s legendary.” **Lift Off (feat. Rocco Palladino)** TM: “I linked up with Rocco through Yussef. They have a proper sort of musical bromance. And it\'s cool to play with them, because they\'re very much in sync. It\'s been interesting finding my voice within that trio. It\'s brought out something different in me.” YD: “I\'ve known Rocco for about 10 years now. I think we\'ve started performing together the last three years now. He\'s crazy, man. You always can tell, because bass players—they\'re very specific, man. He\'s definitely the best at what he does, and obviously he comes from... \[Welsh musician and producer Pino Palladino\], his dad\'s an amazing bass player, too. He knows what he\'s doing, man. Let\'s put it that way.” **I Did It for You** TM: “We just clicked record and we were jamming for a whole day. And this is one of the joints that came up in the evening. We jammed something, then we\'d go up to the control room, we listen. I remember thinking, \'Shit, that sounded really nice.\' I knew I wanted to sing on that one. I was like, \'Yeah, this is a vibe.\'” YD: “We recorded this nearly two years ago, it was one of the first tracks. I\'d been to Brazil a few years back, years ago, and I remember Tom wanting to go. I think he did in the end, so that track was kind of inspired by some of those rhythms and that kind of energy. It\'s closer to Tom\'s sound, I think.” **Last 100** TM: “I was playing some piano, messing around, Yussef was up on the drum kit. It was after a session. We\'re just messing around before we go home, and then I start playing those chords. And I recorded it on my iPhone. I was like, \'This is nice.\' We came back to it the next day and recorded the bassist. This is kind of like the love tune on the record. It\'s a summery, feel-good one.” YD: “You have the initial session and then obviously some of the tracks you need to produce up, so you spend a couple of weeks on them. Tom would write his vocals or add little synths to it, to get those sections there, but the drums are obviously the main thing you want to record and get that first. Then after that, it’s just adding the structure around it. ‘Last 100’ is definitely one of those ones we produced up and got the arrangement and added different instrumentation and backing vocals.” **Kyiv** TM: “So this one was actually recorded in London, but the live video was recorded in Kiev. That was a very, very cold day. It was about minus five degrees. And we were recording the live video for ‘Lift Off’ in this ex-community center in Kiev. It\'s an amazing old building. It looks like a Call of Duty zombie level. It was pretty cool. It was interesting to be in that part of Europe, the fashion and the architecture, ex-Soviet kind of architecture. And everyone in fur jackets and stuff. I want to go back.” YD: “It was in a mad building. It was like a freezer in there. They said we had one reel left, and we’d already wrapped up ‘Lift Off,’ then Rocco started playing these chords and we just recorded real quickly. It just came. What I like to do is still like to make it like it was a song. You play your part. The music is still the most important thing, even though you want to freestyle and you want to solo and all this stuff. You want to make a beat. You want to make something people will listen to as well. It’s just that know-how, how to, even if you are freestyling, just make it into the thing straight away, man.” **Julie Mangos** YD: “That’s our dads speaking on this one. It\'s a medley of little skits and stuff that we\'ve recorded. My dad’s talking about Deptford Market, where he used to sell Caribbean and West Indian food. He\'s describing what it was like in the market. About 20 years ago, he had a stall down there, and we used to have fruit imported and pick it up from the docks. This is just me and Tom trying to give a bit of context to where we\'re coming from. To get our dads on the record, and family involved—it\'s a touch, man.” TM: “Both our dads have been quite involved in coming down throughout making this record. Just coming and listening, giving their opinions on stuff. I called my dad, another day. Clicked record without him knowing, and I asked him what he thought of the record. So we put those on. I think my dad knew that this is something that I really wanted to do, making this record. Because I\'d tell him how excited I was about working with Yussef, and the way the tracks were sounding initially. There\'s a lot of excitement making this record. I think he sensed that.” **Storm Before the Calm (feat. Kaidi Akinnibi)** TM: “Kaidi is an amazing saxophone player. I met him when I was about 12 and he was seven or something. We met at a jazz youth club called Tomorrow’s Warriors. He was just insane at the sax at that time. Then fast-forward 10 years, I hit him up and we start jamming, and he featured on one of my tracks from \[2017 EP\] *5 Day Mischon*. And then we hit him up again, and he\'s been playing in my band, he\'s been touring with me. Thought we\'d try him on this track, and he just destroyed it.” YD: “He\'s 20 years old, and he\'s killing it already. It\'s one of the first ones we recorded as well. It\'s *that* same day, man. The same day, the \'Angel\' day, we recorded this one as well. This one’s got these dark synths, it\'s like a storm. It was always going to be the outro or the intro, but I think it just closes off with a different vibe before you check out. We were just trying to experiment with synths and the OP-1, which is this mad little synth I’ve got, and just span different sounds.”

Over the last decade, Khruangbin (pronounced “krung-bin”) has mastered the art of setting a mood, of creating atmosphere. But on *Mordechai*, follow-up to their 2018 breakthrough *Con Todo El Mundo*, the Houston trio makes space in their globe-spinning psych-funk for something that’s been largely missing until now: vocals. The result is their most direct work to date. From the playground disco of “Time (You and I)” to the Latin rhythms of “Pelota”—inspired by a Japanese film, but sung in Spanish—to the balmy reassurances of “If There Is No Question,” much of *Mordechai* has the immediacy of an especially adventurous pop record. Even moments of hallucinogenic expanse (“One to Remember”) or haze (“First Class”) benefit from the added presence of a human voice. “Never enough paper, never enough letters,” they sing from inside a shower of West African guitar notes on “So We Won’t Forget,” the album’s high point. “You don’t have to be silent.”

If there is a recurring theme to be found in Phoebe Bridgers’ second solo LP, “it’s the idea of having these inner personal issues while there\'s bigger turmoil in the world—like a diary about your crush during the apocalypse,” she tells Apple Music. “I’ll torture myself for five days about confronting a friend, while way bigger shit is happening. It just feels stupid, like wallowing. But my intrusive thoughts are about my personal life.” Recorded when she wasn’t on the road—in support of 2017’s *Stranger in the Alps* and collaborative releases with Lucy Dacus and Julien Baker (boygenius) in 2018 and with Conor Oberst (Better Oblivion Community Center) in 2019—*Punisher* is a set of folk and bedroom pop that’s at once comforting and haunting, a refuge and a fever dream. “Sometimes I\'ll get the question, like, ‘Do you identify as an LA songwriter?’ Or ‘Do you identify as a queer songwriter?’ And I\'m like, ‘No. I\'m what I am,’” the Pasadena native says. “The things that are going on are what\'s going on, so of course every part of my personality and every part of the world is going to seep into my music. But I don\'t set out to make specific things—I just look back and I\'m like, ‘Oh. That\'s what I was thinking about.’” Here, Bridgers takes us inside every song on the album. **DVD Menu** “It\'s a reference to the last song on the record—a mirror of that melody at the very end. And it samples the last song of my first record—‘You Missed My Heart’—the weird voice you can sort of hear. It just felt rounded out to me to do that, to lead into this album. Also, I’ve been listening to a lot of Grouper. There’s a note in this song: Everybody looked at me like I was insane when I told Rob Moose—who plays strings on the record—to play it. Everybody was like, ‘What the fuck are you taking about?’ And I think that\'s the scariest part of it. I like scary music.” **Garden Song** “It\'s very much about dreams and—to get really LA on it—manifesting. It’s about all your good thoughts that you have becoming real, and all the shitty stuff that you think becoming real, too. If you\'re afraid of something all the time, you\'re going to look for proof that it happened, or that it\'s going to happen. And if you\'re a miserable person who thinks that good people die young and evil corporations rule everything, there is enough proof in the world that that\'s true. But if you\'re someone who believes that good people are doing amazing things no matter how small, and that there\'s beauty or whatever in the midst of all the darkness, you\'re going to see that proof, too. And you’re going to ignore the dark shit, or see it and it doesn\'t really affect your worldview. It\'s about fighting back dark, evil murder thoughts and feeling like if I really want something, it happens, or it comes true in a totally weird, different way than I even expected.” **Kyoto** “This song is about being on tour and hating tour, and then being home and hating home. I just always want to be where I\'m not, which I think is pretty not special of a thought, but it is true. With boygenius, we took a red-eye to play a late-night TV show, which sounds glamorous, but really it was hurrying up and then waiting in a fucking backstage for like hours and being really nervous and talking to strangers. I remember being like, \'This is amazing and horrible at the same time. I\'m with my friends, but we\'re all miserable. We feel so lucky and so spoiled and also shitty for complaining about how tired we are.\' I miss the life I complained about, which I think a lot of people are feeling. I hope the parties are good when this shit \[the pandemic\] is over. I hope people have a newfound appreciation for human connection and stuff. I definitely will for tour.” Punisher “I don\'t even know what to compare it to. In my songwriting style, I feel like I actually stopped writing it earlier than I usually stop writing stuff. I usually write things five times over, and this one was always just like, ‘All right. This is a simple tribute song.’ It’s kind of about the neighborhood \[Silver Lake in Los Angeles\], kind of about depression, but mostly about stalking Elliott Smith and being afraid that I\'m a punisher—that when I talk to my heroes, that their eyes will glaze over. Say you\'re at Thanksgiving with your wife\'s family and she\'s got an older relative who is anti-vax or just read some conspiracy theory article and, even if they\'re sweet, they\'re just talking to you and they don\'t realize that your eyes are glazed over and you\'re trying to escape: That’s a punisher. The worst way that it happens is like with a sweet fan, someone who is really trying to be nice and their hands are shaking, but they don\'t realize they\'re standing outside of your bus and you\'re trying to go to bed. And they talk to you for like 45 minutes, and you realize your reaction really means a lot to them, so you\'re trying to be there for them, too. And I guess that I\'m terrified that when I hang out with Patti Smith or whatever that I\'ll become that for people. I know that I have in the past, and I guess if Elliott was alive—especially because we would have lived next to each other—it’s like 1000% I would have met him and I would have not known what the fuck I was talking about, and I would have cornered him at Silverlake Lounge.” **Halloween** “I started it with my friend Christian Lee Hutson. It was actually one of the first times we ever hung out. We ended up just talking forever and kind of shitting out this melody that I really loved, literally hanging out for five hours and spending 10 minutes on music. It\'s about a dead relationship, but it doesn\'t get to have any victorious ending. It\'s like you\'re bored and sad and you don\'t want drama, and you\'re waking up every day just wanting to have shit be normal, but it\'s not that great. He lives right by Children\'s Hospital, so when we were writing the song, it was like constant ambulances, so that was a depressing background and made it in there. The other voice on it is Conor Oberst’s. I was kind of stressed about lyrics—I was looking for a last verse and he was like, ‘Dude, you\'re always talking about the Dodger fan who got murdered. You should talk about that.’ And I was like, \'Jesus Christ. All right.\' The Better Oblivion record was such a learning experience for me, and I ended up getting so comfortable halfway through writing and recording it. By the time we finished a whole fucking record, I felt like I could show him a terrible idea and not be embarrassed—I knew that he would just help me. Same with boygenius: It\'s like you\'re so nervous going in to collaborating with new people and then by the time you\'re done, you\'re like, ‘Damn, it\'d be easy to do that again.’ Your best show is the last show of tour.” Chinese Satellite “I have no faith—and that\'s what it\'s about. My friend Harry put it in the best way ever once. He was like, ‘Man, sometimes I just wish I could make the Jesus leap.’ But I can\'t do it. I mean, I definitely have weird beliefs that come from nothing. I wasn\'t raised religious. I do yoga and stuff. I think breathing is important. But that\'s pretty much as far as it goes. I like to believe that ghosts and aliens exist, but I kind of doubt it. I love science—I think science is like the closest thing to that that you’ll get. If I\'m being honest, this song is about turning 11 and not getting a letter from Hogwarts, just realizing that nobody\'s going to save me from my life, nobody\'s going to wake me up and be like, ‘Hey, just kidding. Actually, it\'s really a lot more special than this, and you\'re special.’ No, I’m going to be the way that I am forever. I mean, secretly, I am still waiting on that letter, which is also that part of the song, that I want someone to shake me awake in the middle of the night and be like, ‘Come with me. It\'s actually totally different than you ever thought.’ That’d be sweet.” **Moon Song** “I feel like songs are kind of like dreams, too, where you\'re like, ‘I could say it\'s about this one thing, but...’ At the same time it’s so hyper-specific to people and a person and about a relationship, but it\'s also every single song. I feel complex about every single person I\'ve ever cared about, and I think that\'s pretty clear. The through line is that caring about someone who hates themselves is really hard, because they feel like you\'re stupid. And you feel stupid. Like, if you complain, then they\'ll go away. So you don\'t complain and you just bottle it up and you\'re like, ‘No, step on me again, please.’ It’s that feeling, the wanting-to-be-stepped-on feeling.” Savior Complex “Thematically, it\'s like a sequel to ‘Moon Song.’ It\'s like when you get what you asked for and then you\'re dating someone who hates themselves. Sonically, it\'s one of the only songs I\'ve ever written in a dream. I rolled over in the middle of the night and hummed—I’m still looking for this fucking voice memo, because I know it exists, but it\'s so crazy-sounding, so scary. I woke up and knew what I wanted it to be about and then took it in the studio. That\'s Blake Mills on clarinet, which was so funny: He was like a little schoolkid practicing in the hallway of Sound City before coming in to play.” **I See You** “I had that line \[‘I\'ve been playing dead my whole life’\] first, and I\'ve had it for at least five years. Just feeling like a waking zombie every day, that\'s how my depression manifests itself. It\'s like lethargy, just feeling exhausted. I\'m not manic depressive—I fucking wish. I wish I was super creative when I\'m depressed, but instead, I just look at my phone for eight hours. And then you start kind of falling in love and it all kind of gets shaken up and you\'re like, ‘Can this person fix me? That\'d be great.’ This song is about being close to somebody. I mean, it\'s about my drummer. This isn\'t about anybody else. When we first broke up, it was so hard and heartbreaking. It\'s just so weird that you could date and then you\'re a stranger from the person for a while. Now we\'re super tight. We\'re like best friends, and always will be. There are just certain people that you date where it\'s so romantic almost that the friendship element is kind of secondary. And ours was never like that. It was like the friendship element was above all else, like we started a million projects together, immediately started writing together, couldn\'t be apart ever, very codependent. And then to have that taken away—it’s awful.” **Graceland Too** “I started writing it about an MDMA trip. Or I had a couple lines about that and then it turned into stuff that was going on in my life. Again, caring about someone who hates themselves and is super self-destructive is the hardest thing about being a person, to me. You can\'t control people, but it\'s tempting to want to help when someone\'s going through something, and I think it was just like a meditation almost on that—a reflection of trying to be there for people. I hope someday I get to hang out with the people who have really struggled with addiction or suicidal shit and have a good time. I want to write more songs like that, what I wish would happen.” **I Know the End** “This is a bunch of things I had on my to-do list: I wanted to scream; I wanted to have a metal song; I wanted to write about driving up the coast to Northern California, which I’ve done a lot in my life. It\'s like a super specific feeling. This is such a stoned thought, but it feels kind of like purgatory to me, doing that drive, just because I have done it at every stage of my life, so I get thrown into this time that doesn\'t exist when I\'m doing it, like I can\'t differentiate any of the times in my memory. I guess I always pictured that during the apocalypse, I would escape to an endless drive up north. It\'s definitely half a ballad. I kind of think about it as, ‘Well, what genre is \[My Chemical Romance’s\] “Welcome to the Black Parade” in?’ It\'s not really an anthem—I don\'t know. I love tricking people with a vibe and then completely shifting. I feel like I want to do that more.”

“I just wanted people to see me broken down and to know that I’m not afraid to be broken down,” Angel Olsen tells Apple Music. “In fact, my whole life had broken down.” The singer is discussing why she chose to release *Whole New Mess*—a collection of raw, unvarnished tracks largely made up of demo-like recordings of the songs that would later become souped up and string-laden on 2019’s stunningly ambitious *All Mirrors*. “Originally, I wanted both to come out at the same time,” she explains. “But I wanted to make an honest account—untampered with by anybody. This was just me, the way that I would make demos.” Recorded at a church-turned-studio in Anacortes, Washington (“I couldn’t do it at home; I was still sitting in a lot of the feelings from the songs and I wanted to have a place to cook them”), *Whole New Mess* is a world away from the drama of *All Mirrors*, those galloping melodies and theatrical strings stripped away to leave a lone guitar, the occasional organ, and Olsen’s unmistakable vocals. *Whole New Mess* is, as the singer put it, “ragged,\" at times crackling as though it were an old vinyl LP. “It’s purposefully a mess,” she says, “because that’s how things are. A lot of the time, cleaning it up is the process. And I like to show where things start and how messy they are before they get to a point where they’re digestible for people when they come out.” Still, the record is as haunting as you’d expect, Olsen’s voice taking on an almost celestial quality on songs like “(Summer Song),” “Too Easy (Bigger Than Us),” or “Chance (Forever Love)” as it carries the full weight of the experiences and emotions that fueled these tracks. The dissolution of a relationship may have hit before they were written, but Olsen bristles at the idea that any of them document that alone. “I find it really infantilizing the way people just look at my work as heartbreak,” she says. “All I’m asking is for people to look a little further. That’s all.” Instead, this is an album “inspired by what I’ve been doing, by traveling constantly, by writing constantly for the last seven years and the things that I’ve learned,” she says. “It’s about the hardship that I’ve had to confront with people—not just romantically but just by accidentally \[building\] a business from the ground up and having to learn a lot of things along the way, the hard way.” By drawing the walls of her music in, she hopes people will see another side to her. “When I go out into the music world and I build my platform, I’m putting on wigs and glam dresses and putting on tons of makeup. Normally, when I get home, it’s a different story. It’s a different person. It’s a different life. I wanted to do something that was a little bit closer to who I actually am.” *Whole New Mess* is the first time the singer has delivered an album without a band since 2012’s *Half Way Home*. Doing it this way was, in part, a way of going back to her early songs and rediscovering how to, as she says, “feel strong in myself again outside of relying on so many band members or collaborators.” But it was also a necessary step to emancipate herself from these tracks, in order to let those same people back in to help her create the majesty of *All Mirrors*. And sitting in—and then letting go of—darker times to pave the way for something more beautiful chimes well with Olsen’s world view. “There’s a lot of hatred and anger and frustration happening in the world right now, and there’s a lot of destruction,” she says. “But all of that needs to happen before there can be progress. We really need to reexamine the way that we live, because we want to continue to live in this world and continue to be able to share the things that we enjoy. I really stand by ‘whole new mess’ as a phrase. I want to inspire people to think about what that means, whether it has to do with me personally and what I intended, or whether it inspires them to want to reexamine or look at those things in their own reality. I think there\'s a huge reckoning going on, and I\'ve been really inspired.”

No map is a match for Kate NV. On her third album, the Moscow electronic musician shreds conventional geographical boundaries, leaving border fences splintered in the rearview. Her music is, very roughly speaking, a mixture of Japanese city pop and the sort of avant-disco that used to soundtrack downtown New York spots like the Mudd Club. The synths and marimba are straight out of ’80s Tokyo; the sumptuous production and dubbed-out vocals suggest ZE Records artists like Cristina; the layered horns might as well be those of session players from Arthur Russell’s orbit. We haven’t even touched upon her singing, which flits between French, English, and Russian as she juggles experimental vocal techniques with the breathy sighs of dream pop. For all their idiosyncrasies, these songs have a way of sinking into your psyche. “Not Not Not” smooths its staccato phrasing into a form lilting and hypnotic; “Sayonara” smears slap bass, streaks of synth, and hiccupping sighs into a splotchy pointillism that’s both abstract and intuitive. On their own, any one of these tracks might be mistaken for an artifact from an alternate-universe ’80s; taken together, they amount to a triumph of world-building. Kate NV has said that she wrote these songs during an emotionally difficult period, but you’d never know it: Every one quivers with the thrill of unlimited possibility.

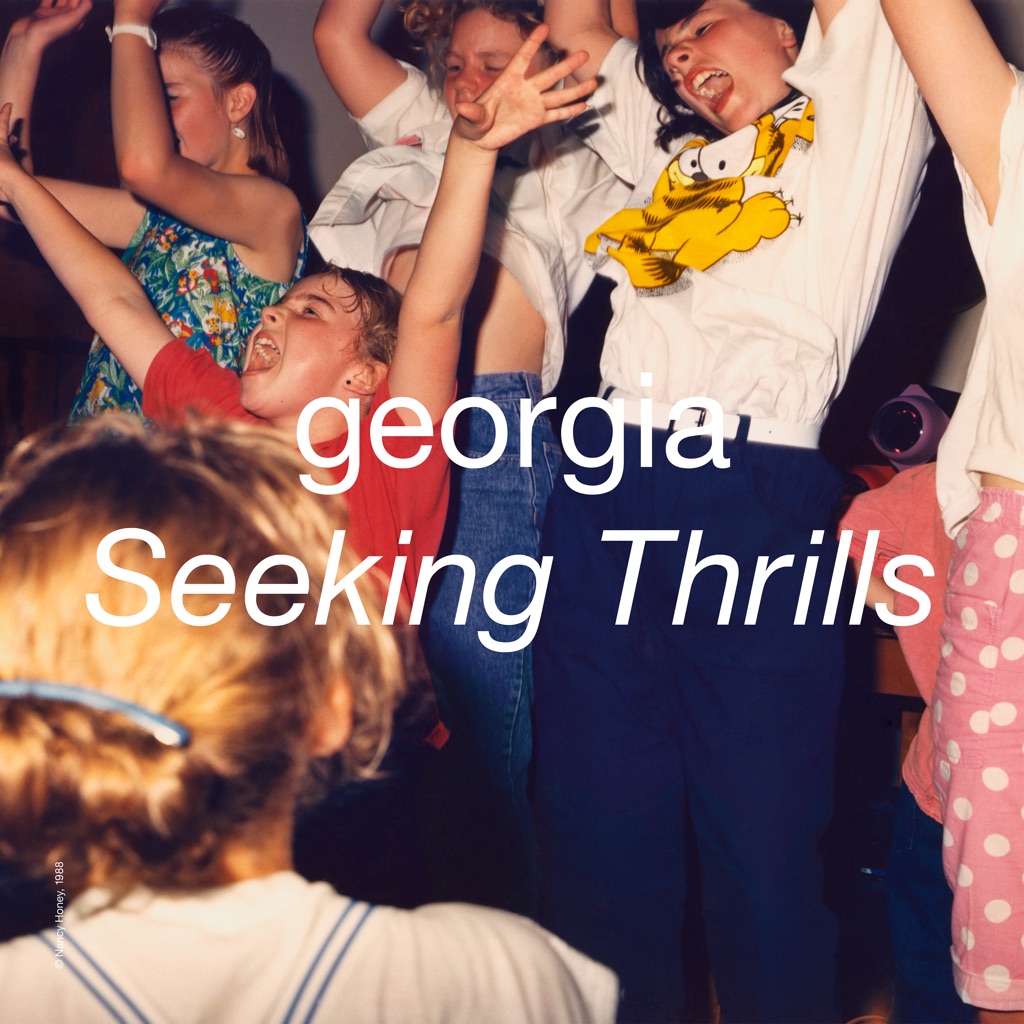

“I have such a personal connection to dance music,” Georgia Barnes tells Apple Music. “I grew up around the UK rave scene, being taken to the raves with my mum and dad \[Leftfield’s Neil Barnes\] because they couldn’t afford childcare. I\'d witness thousands of people dancing to a pulsating beat and I always found it fascinating, so I\'m returning to my roots. The story of dance music and house music is a familiar one—it helped my family, it gave us a roof over our heads.” Five years on from her self-titled debut, the Londoner channels the grooves and good times of the Detroit, Chicago, and Berlin club scenes on the single “About Work the Dancefloor,” “The Thrill,” and “24 Hours.” Tender, twinkling tracks like “Ultimate Sailor” recall Kate Bush and Björk, while her love of punk, dub, and Depeche Mode come through on “Ray Guns,” “Feel It,” and “Never Let You Go.” “My first record was a bit of an experiment,” she explains. “Then I knew exactly what needed to be done—I just locked myself away in the studio and researched all the songs that I love. I also got fit, I stopped drinking, I became a vegan, so these songs are a real reflection of a personal journey I went on—a lot happened in those five years.” Join Georgia on a track-by-track tour of *Seeking Thrills*. **Started Out** “Without ‘Started Out’ this album would be a completely different story. It really did help me break into the radio world, and it was really an important song to kickstart the campaign. Everything you\'re hearing I\'ve played: It\'s all analog synthesizers and programmed drum machines. We set the studio up like Frankie Knuckles or Marshall Jefferson did, so it’s got a real authenticity to it, which was important to me. I didn\'t just want to take the sounds and modernize them, I wanted to use the gear that they were using.” **About Work the Dancefloor** “During the making of this track I was very heavily listening to early techno music, so I wanted to create a song that just had that driving bassline and beat to it. And then I came up with that chorus, and I wanted it to be on a vocoder to have that real techno sound. Not many pop songs have a vocoder as the chorus—I think the only one is probably Beastie Boys’ ‘Intergalactic.’” **Never Let You Go** “I thought it\'d be really cool to have a punky electronic song on the record. So, ‘Never Let You Go’ started as this punk, garage-rock song, but it just sounded like it was for a different album. So then I wrote the chorus, which gave it this bit more pop direction. During the making of this record I was really disciplined, I wasn\'t drinking, I was on this very strict routine of working during the day and then finishing and having a good night’s sleep, so I think some of the songs have these elements of longing for something. I also liked the way Kate Bush wrote: Her lyrics were inspired by the elements, and I wanted to write about the sky like she did. It just all kind of came into one on that song.” **24 Hours** “This was written after I spent 24 hours in the Berghain club in Berlin. It was a life-changing experience. I was sober and observing all these amazing characters and having this kind of epiphany. I saw this guy and this girl notice each other on the floor, just find each other—they clearly didn\'t know each other before. They were dancing together and it was so beautiful. People do that even in an age where most people find each other on dating apps. That\'s where I got the line ‘If two hearts ever beat the same/We can beat it.’” **Mellow (feat. Shygirl)** “I wasn\'t drinking, but I\'ve had my fair share of doing crazy stuff. I wrote this song because I really wanted to go out and seek my hedonistic side. I wanted another female voice on it, and I heard Shygirl’s \[London singer and DJ Blane Muise\] music and really liked it. She understood the type of vibe I was going for because she likes to drink and she likes to go out with her girls. I didn\'t want many collaborations on the record, I just wanted that one moment in this song.” **Till I Own It** “I\'ve got a real emotional connection to this song. I was listening a lot to The Blue Nile, the Glaswegian band, who were quite ethereal and slow. I was interested in adding a song that was a bit more serious and emotive—so I wrote this because I just had this feeling of alienation in London at the time. Also, during the making of this record Brexit happened, so I wrote this song to reflect the changing landscape.” **I Can’t Wait** “‘I Can’t Wait’ is about the thrill of falling in love and that feeling that you get from starting something new. I was listening to a lot of reggae and dub and I\'d wanted to kind of create a rhythm with synthesizers that was almost like ragga. But this is definitely a pop record—and quite a sweet three-minute pop song.” **Feel It** “This was one of the first songs that I recorded for the second record. It’s got that kind of angry idea of punk singers. There are a couple of moments on this record where I was definitely listening to John Lydon and Public Image Ltd., and it\'s also an important song because I felt like it empowers the listener. I wanted people to listen to these songs and do something in their lives that is different, or to go and experience the dance floor. I think \'Feel It\' does that.” **Ultimate Sailor** “‘Ultimate Sailor’ was something that just came along unexpectedly. I really wanted to create a song that just put the listener somewhere. All the elemental things really inspired this record: skies, seas, mountains, pyramids. I think that is one of the things that\'s rubbed off on me from Kate Bush. She’s the artist that I play most in the studio.” **Ray Guns** “I had a concept before I wrote this song about an army of women shooting these rays of light out of these guns, creating love in the sky to influence the whole world. It\'s about collective energy again. I was influenced by all the Chicago house and Detroit techno, and how bravery came from this new explosive scene. And \'Ray Guns\' was meant to try and instill a sense of that power to the listener.” **The Thrill (feat. Maurice)** “At this point I was so influenced by Chicago house and just feeling like I wanted to create a song in homage to it. I wanted a song that took you on a journey to this Chicago house party, and then you have these vocals that induce this kind of trip. Maurice is actually me—it’s an alter ego! That\'s just my voice pitched down! I thought, ‘I’m going to fuck with people and put \'featuring Maurice.’” **Honey Dripping Sky** “I love the way Frank Ocean has the balls to just put two songs together and then take the listener on a journey. This song has a quite dub section at the end, and it\'s about the kind of journey that you go through on a breakup, so it’s really personal. It’s also quite an unusual track, and I wanted to end the album on a thrilling feeling. It\'s a statement to end on a song like that.”

Field Music’s new release is “Making A New World”, a 19 track song cycle about the after-effects of the First World War. But this is not an album about war and it is not, in any traditional sense, an album about remembrance. There are songs here about air traffic control and gender reassignment surgery. There are songs about Tiananmen Square and about ultrasound. There are even songs about Becontree Housing Estate and about sanitary towels. The songs grew from a project for the Imperial War Museum and were first performed at their sites in Salford and London in January 2019. The starting point was an image from a 1919 publication on munitions by the US War Department, made using “sound ranging”, a technique that utilised an array of transducers to capture the vibrations of gunfire at the front. These vibrations were displayed on a graph, similar to a seismograph, where the distances between peaks on different lines could be used to pinpoint the location of enemy armaments. This particular image showed the minute leading up to 11am on 11th November 1918, and the minute immediately after. One minute of oppressive, juddering noise and one minute of near-silence. “We imagined the lines from that image continuing across the next hundred years,” says the band’s David Brewis, “and we looked for stories which tied back to specific events from the war or the immediate aftermath.” If the original intention might have been to create a mostly instrumental piece, this research forced and inspired a different approach. These were stories itching to be told. The songs are in a kind of chronological order, starting with the end of the war itself; the uncertainty of heading home in a profoundly altered world (“Coffee or Wine”). Later we hear a song about the work of Dr Harold Gillies (the shimmering ballad, “A Change of Heir”), whose pioneering work on skin grafts for injured servicemen led him, in the 1940s, to perform some of the very first gender reassignment surgeries. We see how the horrors of the war led to the Dada movement and how that artistic reaction was echoed in the extreme performance art of the 60s and 70s (the mathematical head-spin of “A Shot To The Arm”). And then in the funk stomp of Money Is A Memory, we picture an office worker in the German Treasury preparing documents for the final instalment on reparation debts - a payment made in 2010, 91 years after the Treaty of Versailles was signed. A defining, blood-spattered element of 20th century history becomes a humdrum administrative task in a 21st century bureaucracy.

Squirrel Flower - the moniker of Ella O’Connor Williams - announces I Was Born Swimming, her debut album, out January 31st on Full Time Hobby (Polyvinyl in the US), and presents the lead single/video, ‘Red Shoulder’. The album’s title was inspired by Williams’ birth on August 11th 1996 - the hottest day of the year - born still inside a translucent caul sac membrane, surrounded by amniotic fluid. Throughout the 12 songs, landscapes change and relationships shift. The album’s lyrics feel like effortless expressions of exactly the way it feels to change — abstract, determined and hopeful. Squirrel Flower’s music is ethereal and warm, brimming over with emotional depth but with a steely eyed bite and confidence in it’s destination. The band on I Was Born Swimming plays with delicate intention, keeping the arrangements natural and light while Williams’ lead guitar is often fiercely untethered. The album was tracked live, with few overdubs, at The Rare Book Room Studio in New York City with producer Gabe Wax (Adrienne Lenker, Palehound, Cass McCombs). The musicians were selected by Wax and folded themselves into the songs effortlessly. At the heart of the album lives Williams’ haunting voice and melancholic, soulful guitar. The sounds expand and contract over diverse moods, cutting loose on the heavier riffs of ‘Red Shoulder’. “‘Red Shoulder’ is a song about destabilisation and dissociation,” explains Williams. “Something soft and tender becomes warped and sinister, turning into sensory overload and confusion. How can something so lovely turn painful and claustrophobic? The song ends with a heavy and visceral guitar solo, attempting to reground what went awry.” Williams comes from a deep-rooted musical family tree. Her grandparents were classical musicians who lived in the Gate Hill Co-op, an artistic cooperative from upstate New York that grew out of Black Mountain College. Ella’s father, Jesse Williams, spent most of his life as a touring jazz and blues performer and educator, and lends his bass playing to the album. Growing up in a family of hard working musicians fostered a love of music and started Williams down her own musical path. As a child, Williams adopted the alter ego of Squirrel Flower. A couple years later, she began singing with the Boston Children’s Chorus while studying music theory and teaching herself to play the guitar. As a teen, she discovered the Boston DIY and folk music scenes and began writing, recording, and performing her own songs, now returning to Squirrel Flower as her stage name. Sheer determination and belief quickly saw her make a name for herself in this newly discovered scene. Doing everything from making videos to the production of her music herself she recorded two EP’s and began touring, supporting the likes of Soccer Mommy and Adrienne Lenker (Big Thief). During this time the signature artful songcraft heard on I Was Born Swimming was formed.

Shopping return with their new album All Or Nothing – a record that speaks about commitment, leaps of faith and tests of courage. “A lot has happened in our personal lives since we last recorded and we knew this album was going to reflect that exciting and scary feeling that comes with change, heartbreak and personal evolution”, the band explains. Since their last record the band are now spread across the globe with Billy in LA and Andrew and Rachel in Glasgow, and the songs were written in a two week intensive period while they were all together. Taking a bold leap towards pop with their most vibrant & punchy production to date, mixed and produced by Nick Sylvester.

English songsmith Douglas Dare returns with his third and most stripped back studio album to date, Milkteeth, released on 21 February 2020 with Erased Tapes. Produced by Mike Lindsay — founding member of Tunng and one half of LUMP with Laura Marling — in his studio in Margate in just twelve days, Milkteeth sees Douglas become confident and comfortable enough with his own identity to reflect on both the joys and pains of youth. In doing so, he has established himself as a serious 21st century singer-songwriter with an enduring lyrical poise and elegant minimalist sound.

1. ሰሜን እና ደቡብ Semen Ena Debub North & South (Hailu Mergia) 2. የኔ ምርጫ Yene Mircha My Choice (Hailu Mergia) 3. ባይኔ ላይ ይሄዳል Bayine Lay Yihedal He Walks In My Vision (Asnakech Worku) 4. አቢቹ ነጋ ነጋ Abichu Nega Nega How Are You, Abichu (trad., arr. Hailu Mergia) 5. የኔ አበባ Yene Abeba My Flower (Hailu Mergia) 6. ሼመንደፈር Shemendefer Chemin de Fer Railway (Teddy Afro) It's been a long, winding road to Hailu Mergia's sixth decade of musical activity. From a young musician in the 60s starting out in Addis Ababa to the 70s golden age of dance bands to the new hope as an emigre in America to the drier period of the 90s and 2000s when he mainly played keyboard in his taxi while waiting in the airport queue or at home with friends. More recently, with the reissue of his classic works and a re-assessment of his role in Ethiopian music history, Mergia has played to audiences big and small in some of the most cherished venues around the world. With his 2018 critical breakthrough "Lala Belu" Mergia consolidated his legacy, producing the album on his own and connecting with listeners through his vision of modern Ethiopian music. Extensive touring after the record revealed an artist who is in no way stuck in the nostalgia for the “golden age” sound. The press agreed, including the New York Times, BBC and Pitchfork, calling his music “triumphantly in the present” in its Best 200 Albums of the 2010's list. Mergia's new album "Yene Mircha" ("My Choice" in Amharic) encapsulates many of the things that make the keyboardist, accordionist and composer-arranger remarkable—elements that have persisted to maintain his vitality all these years, through the ebb and flow of his career. The rock solid trio with whom he has toured the world most recently, DC-based Alemseged Kebede (bass) and Ken Joseph (drums), forms the nucleus around which an expanded band makes a potent response to the contemporary jazz future "Lala Belu" promised. "Yene Mircha" calcifies Mergia's prolific stream of creativity and his philosophy that there is a multitude of Ethiopian musical approaches, not just one sound. Enlisting the help of master mesenqo (traditional stringed instrument) player Setegn Atenaw, celebrated vocalist Tsehay Kassa and legendary saxophone player Moges Habte from his 70s outfit Walias Band, Mergia enhances his bright, electric band on this recording with an expanded line up on some songs. Mergia produced the album which features several of his original compositions along with songs by Asnakesh Worku and Teddy Afro. An artist still reinventing his sound every night on stage during his marathon live sets, this 74-year-old icon refuses to make the same album twice. His creative process in the studio—starting with the core band, then after listening extensively over weeks and months adding more sounds and instruments—is as urgent and risky as his concerts can be, pushing the band to the outer limits of group improvisation and back with chord extensions during his exploratory solos. "Yene Mircha" captures this live experience and fosters an expansive view of what else could be in store for this tireless practitioner of Ethiopian music.

Daniel Avery and Alessandro Cortini have different skill sets: The former’s a purveyor of heavy-hitting techno, while the latter specializes in shape-shifting modular-synth etudes (when he’s not playing with Nine Inch Nails). Their full-length debut together sounds more like Berliner Cortini than Londoner Avery: In place of four-to-the-floor rhythms and surging acid lines, there are floating pads, pensive arpeggios, and eerie ambient miniatures. But they also venture into spaces neither has explored before: “At First Sight” and “Enter Exit” are so flush with distortion that they verge on shoegaze, while the even more overdriven “Inside the Ruins” boasts the scorched-earth textures of doom metal. In addition to being formally inventive, *Illusion of Time* is emotionally exploratory, too, slipping between contrasting moods in a way that accentuates its immersive qualities—and makes its climactic payoff, with the blissed-out shimmer of “Water,” that much sweeter.

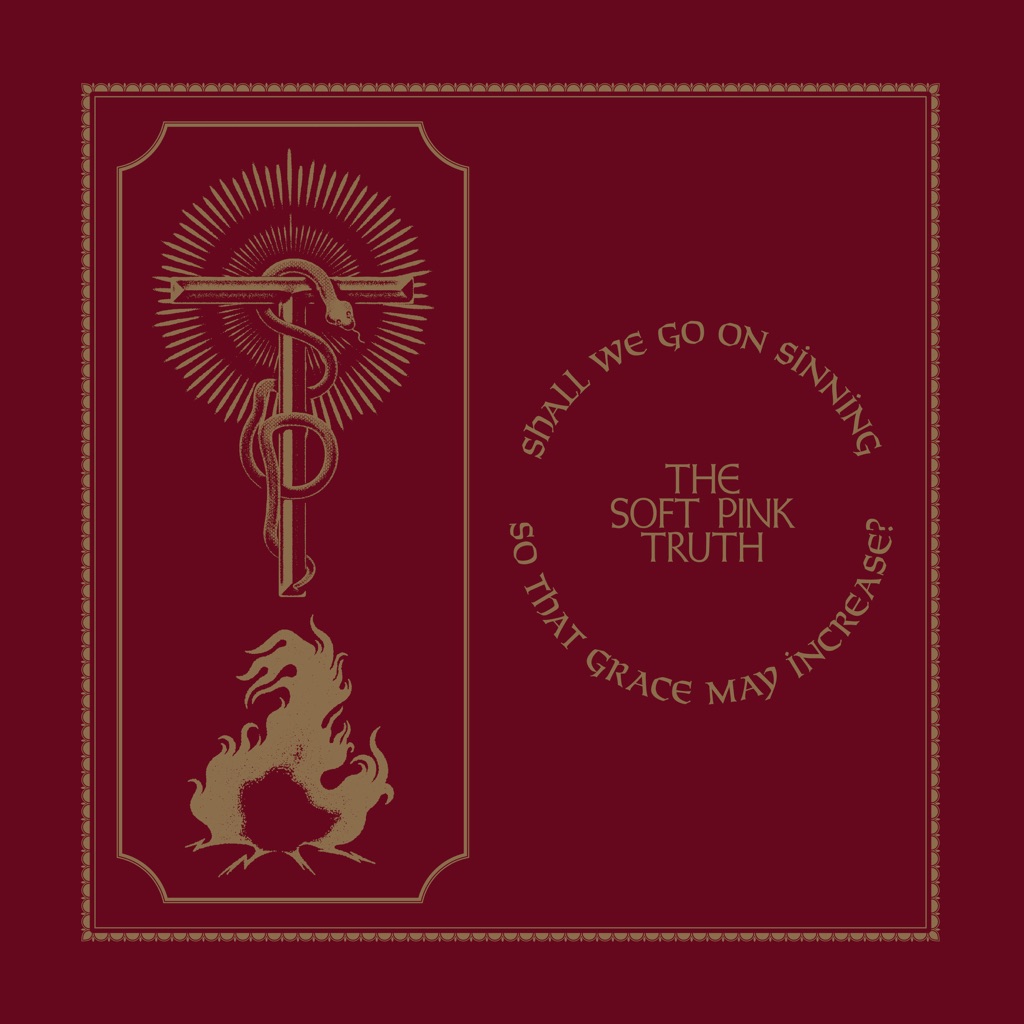

Drew Daniel’s solo alias The Soft Pink Truth was originally fueled by a distinctly madcap energy. Without the elaborate conceptual frameworks of his duo Matmos, Baltimore-based Daniel was free to let his imagination run wild. His 2003 debut, *Do You Party?*, braided politics with pleasure in gonzo glitch techno; with *Do You Want New Wave or Do You Want the Soft Pink Truth?* and then *Why Do the Heathen Rage?*, he turned his idiosyncratic IDM to covers of punk rock and black metal. But *Shall We Go On Sinning So That Grace May Increase?* steps away from those audacious hijinks. Composed with a rich array of electronic and acoustic tones, and suffused in vintage Roland Space Echo, the album strikes a balance between ambient and classical minimalism; created in response to politically motivated feelings of sadness and anger, it is also a meditation on community and interdependency. Guest vocalists Colin Self, Angel Deradoorian, and Jana Hunter make up the album’s choral core; percussionist Sarah Hennies lays down flickering bell-tone rhythms, while John Berndt and Horse Lords’ Andrew Bernstein weave sinewy saxophone into the mix, and Daniel’s partner, M.C. Schmidt, lends spare, contemplative piano melodies. The result is a nine-part suite as affecting as it is ambitious, where devotional vocal harmonies spill into softly pulsing house rhythms, and shimmering abstractions alternate with songs as gentle as lullabies.

The Soft Pink Truth is Drew Daniel, one half of acclaimed electronic duo Matmos, Shakespearean scholar and a celebrated producer and sound artist. Daniel started the project as an outlet to explore visceral and sublime sounds that fall outside of Matmos’ purview, drawing on his vast knowledge of rave, black metal and crust punk obscurities while subverting and critiquing established genre expectations. On the new album Shall We Go On Sinning So That Grace May Increase? Daniel takes a bold and surprising new direction, exploring a hypnagogic and ecstatic space somewhere between deep dance music and classical minimalism as a means of psychic healing. Shall We Go On Sinning… began life as an emotional response to the creeping rise of fascism around the globe, creativity as a form of self-care, resulting in an album of music that expressed joy and gratitude. Daniel explains: “The election of Donald Trump made me feel very angry and sad, but I didn’t want to make “angry white guy” music in a purely reactive mode. I felt that I needed to make music through a different process, and to a different emotional outcome, to get past a private feeling of powerlessness by making musical connections with friends and people I admire, to make something that felt socially extended and affirming.” What began with Daniel quickly evolved into a promiscuous and communal undertaking. Vocals provided by the chorus of Colin Self, Angel Deradoorian and Jana Hunter form the foundation of most of the tracks, sometimes left naked and unchanged as with the ethereal opening line (“Shall”) or the sensuous R&B refrains on “We”, at other times shrouded in effects and morphed into new forms. Stately piano melodies written by Daniel’s partner M.C. Schmidt as well as Koye Berry alongside entrancing vibraphone and percussion patterns from Sarah Hennies push tracks toward ecstatic and melodic peaks, while rich saxophone textures played by Andrew Bernstein (Horse Lords) and John Berndt are used to add color and texture throughout. The album’s overall sound was in part shaped by Daniel hosting Mitchell Brown of GASP during Maryland Deathfest. Daniel borrowed Brown’s Roland Space Echo tape unit which he then used extensively throughout to give the album a flickering, ethereal quality. By moving beyond simple plunderphonic sampling and opening up a genuine dialogue with other musicians, Daniel left room in his compositions for moments of genuine surprise, capturing the freeform, communal energy of a DJ set or live improvisation session more than a recording project. Shall We Go On Sinning, a biblical quote from Paul the Apostle, was chosen by Daniel because it describes a question that he was applying both to his creative practice and how one should live in the world. The melodies, jubilance, and meditative nature of album provides a much-needed escape from the contemporary hell-scape. The process of creating Shall We Go On Sinning, in and of itself, is the Soft Pink Truth’s way of championing creativity and community over rage and nihilism.