If there is a recurring theme to be found in Phoebe Bridgers’ second solo LP, “it’s the idea of having these inner personal issues while there\'s bigger turmoil in the world—like a diary about your crush during the apocalypse,” she tells Apple Music. “I’ll torture myself for five days about confronting a friend, while way bigger shit is happening. It just feels stupid, like wallowing. But my intrusive thoughts are about my personal life.” Recorded when she wasn’t on the road—in support of 2017’s *Stranger in the Alps* and collaborative releases with Lucy Dacus and Julien Baker (boygenius) in 2018 and with Conor Oberst (Better Oblivion Community Center) in 2019—*Punisher* is a set of folk and bedroom pop that’s at once comforting and haunting, a refuge and a fever dream. “Sometimes I\'ll get the question, like, ‘Do you identify as an LA songwriter?’ Or ‘Do you identify as a queer songwriter?’ And I\'m like, ‘No. I\'m what I am,’” the Pasadena native says. “The things that are going on are what\'s going on, so of course every part of my personality and every part of the world is going to seep into my music. But I don\'t set out to make specific things—I just look back and I\'m like, ‘Oh. That\'s what I was thinking about.’” Here, Bridgers takes us inside every song on the album. **DVD Menu** “It\'s a reference to the last song on the record—a mirror of that melody at the very end. And it samples the last song of my first record—‘You Missed My Heart’—the weird voice you can sort of hear. It just felt rounded out to me to do that, to lead into this album. Also, I’ve been listening to a lot of Grouper. There’s a note in this song: Everybody looked at me like I was insane when I told Rob Moose—who plays strings on the record—to play it. Everybody was like, ‘What the fuck are you taking about?’ And I think that\'s the scariest part of it. I like scary music.” **Garden Song** “It\'s very much about dreams and—to get really LA on it—manifesting. It’s about all your good thoughts that you have becoming real, and all the shitty stuff that you think becoming real, too. If you\'re afraid of something all the time, you\'re going to look for proof that it happened, or that it\'s going to happen. And if you\'re a miserable person who thinks that good people die young and evil corporations rule everything, there is enough proof in the world that that\'s true. But if you\'re someone who believes that good people are doing amazing things no matter how small, and that there\'s beauty or whatever in the midst of all the darkness, you\'re going to see that proof, too. And you’re going to ignore the dark shit, or see it and it doesn\'t really affect your worldview. It\'s about fighting back dark, evil murder thoughts and feeling like if I really want something, it happens, or it comes true in a totally weird, different way than I even expected.” **Kyoto** “This song is about being on tour and hating tour, and then being home and hating home. I just always want to be where I\'m not, which I think is pretty not special of a thought, but it is true. With boygenius, we took a red-eye to play a late-night TV show, which sounds glamorous, but really it was hurrying up and then waiting in a fucking backstage for like hours and being really nervous and talking to strangers. I remember being like, \'This is amazing and horrible at the same time. I\'m with my friends, but we\'re all miserable. We feel so lucky and so spoiled and also shitty for complaining about how tired we are.\' I miss the life I complained about, which I think a lot of people are feeling. I hope the parties are good when this shit \[the pandemic\] is over. I hope people have a newfound appreciation for human connection and stuff. I definitely will for tour.” Punisher “I don\'t even know what to compare it to. In my songwriting style, I feel like I actually stopped writing it earlier than I usually stop writing stuff. I usually write things five times over, and this one was always just like, ‘All right. This is a simple tribute song.’ It’s kind of about the neighborhood \[Silver Lake in Los Angeles\], kind of about depression, but mostly about stalking Elliott Smith and being afraid that I\'m a punisher—that when I talk to my heroes, that their eyes will glaze over. Say you\'re at Thanksgiving with your wife\'s family and she\'s got an older relative who is anti-vax or just read some conspiracy theory article and, even if they\'re sweet, they\'re just talking to you and they don\'t realize that your eyes are glazed over and you\'re trying to escape: That’s a punisher. The worst way that it happens is like with a sweet fan, someone who is really trying to be nice and their hands are shaking, but they don\'t realize they\'re standing outside of your bus and you\'re trying to go to bed. And they talk to you for like 45 minutes, and you realize your reaction really means a lot to them, so you\'re trying to be there for them, too. And I guess that I\'m terrified that when I hang out with Patti Smith or whatever that I\'ll become that for people. I know that I have in the past, and I guess if Elliott was alive—especially because we would have lived next to each other—it’s like 1000% I would have met him and I would have not known what the fuck I was talking about, and I would have cornered him at Silverlake Lounge.” **Halloween** “I started it with my friend Christian Lee Hutson. It was actually one of the first times we ever hung out. We ended up just talking forever and kind of shitting out this melody that I really loved, literally hanging out for five hours and spending 10 minutes on music. It\'s about a dead relationship, but it doesn\'t get to have any victorious ending. It\'s like you\'re bored and sad and you don\'t want drama, and you\'re waking up every day just wanting to have shit be normal, but it\'s not that great. He lives right by Children\'s Hospital, so when we were writing the song, it was like constant ambulances, so that was a depressing background and made it in there. The other voice on it is Conor Oberst’s. I was kind of stressed about lyrics—I was looking for a last verse and he was like, ‘Dude, you\'re always talking about the Dodger fan who got murdered. You should talk about that.’ And I was like, \'Jesus Christ. All right.\' The Better Oblivion record was such a learning experience for me, and I ended up getting so comfortable halfway through writing and recording it. By the time we finished a whole fucking record, I felt like I could show him a terrible idea and not be embarrassed—I knew that he would just help me. Same with boygenius: It\'s like you\'re so nervous going in to collaborating with new people and then by the time you\'re done, you\'re like, ‘Damn, it\'d be easy to do that again.’ Your best show is the last show of tour.” Chinese Satellite “I have no faith—and that\'s what it\'s about. My friend Harry put it in the best way ever once. He was like, ‘Man, sometimes I just wish I could make the Jesus leap.’ But I can\'t do it. I mean, I definitely have weird beliefs that come from nothing. I wasn\'t raised religious. I do yoga and stuff. I think breathing is important. But that\'s pretty much as far as it goes. I like to believe that ghosts and aliens exist, but I kind of doubt it. I love science—I think science is like the closest thing to that that you’ll get. If I\'m being honest, this song is about turning 11 and not getting a letter from Hogwarts, just realizing that nobody\'s going to save me from my life, nobody\'s going to wake me up and be like, ‘Hey, just kidding. Actually, it\'s really a lot more special than this, and you\'re special.’ No, I’m going to be the way that I am forever. I mean, secretly, I am still waiting on that letter, which is also that part of the song, that I want someone to shake me awake in the middle of the night and be like, ‘Come with me. It\'s actually totally different than you ever thought.’ That’d be sweet.” **Moon Song** “I feel like songs are kind of like dreams, too, where you\'re like, ‘I could say it\'s about this one thing, but...’ At the same time it’s so hyper-specific to people and a person and about a relationship, but it\'s also every single song. I feel complex about every single person I\'ve ever cared about, and I think that\'s pretty clear. The through line is that caring about someone who hates themselves is really hard, because they feel like you\'re stupid. And you feel stupid. Like, if you complain, then they\'ll go away. So you don\'t complain and you just bottle it up and you\'re like, ‘No, step on me again, please.’ It’s that feeling, the wanting-to-be-stepped-on feeling.” Savior Complex “Thematically, it\'s like a sequel to ‘Moon Song.’ It\'s like when you get what you asked for and then you\'re dating someone who hates themselves. Sonically, it\'s one of the only songs I\'ve ever written in a dream. I rolled over in the middle of the night and hummed—I’m still looking for this fucking voice memo, because I know it exists, but it\'s so crazy-sounding, so scary. I woke up and knew what I wanted it to be about and then took it in the studio. That\'s Blake Mills on clarinet, which was so funny: He was like a little schoolkid practicing in the hallway of Sound City before coming in to play.” **I See You** “I had that line \[‘I\'ve been playing dead my whole life’\] first, and I\'ve had it for at least five years. Just feeling like a waking zombie every day, that\'s how my depression manifests itself. It\'s like lethargy, just feeling exhausted. I\'m not manic depressive—I fucking wish. I wish I was super creative when I\'m depressed, but instead, I just look at my phone for eight hours. And then you start kind of falling in love and it all kind of gets shaken up and you\'re like, ‘Can this person fix me? That\'d be great.’ This song is about being close to somebody. I mean, it\'s about my drummer. This isn\'t about anybody else. When we first broke up, it was so hard and heartbreaking. It\'s just so weird that you could date and then you\'re a stranger from the person for a while. Now we\'re super tight. We\'re like best friends, and always will be. There are just certain people that you date where it\'s so romantic almost that the friendship element is kind of secondary. And ours was never like that. It was like the friendship element was above all else, like we started a million projects together, immediately started writing together, couldn\'t be apart ever, very codependent. And then to have that taken away—it’s awful.” **Graceland Too** “I started writing it about an MDMA trip. Or I had a couple lines about that and then it turned into stuff that was going on in my life. Again, caring about someone who hates themselves and is super self-destructive is the hardest thing about being a person, to me. You can\'t control people, but it\'s tempting to want to help when someone\'s going through something, and I think it was just like a meditation almost on that—a reflection of trying to be there for people. I hope someday I get to hang out with the people who have really struggled with addiction or suicidal shit and have a good time. I want to write more songs like that, what I wish would happen.” **I Know the End** “This is a bunch of things I had on my to-do list: I wanted to scream; I wanted to have a metal song; I wanted to write about driving up the coast to Northern California, which I’ve done a lot in my life. It\'s like a super specific feeling. This is such a stoned thought, but it feels kind of like purgatory to me, doing that drive, just because I have done it at every stage of my life, so I get thrown into this time that doesn\'t exist when I\'m doing it, like I can\'t differentiate any of the times in my memory. I guess I always pictured that during the apocalypse, I would escape to an endless drive up north. It\'s definitely half a ballad. I kind of think about it as, ‘Well, what genre is \[My Chemical Romance’s\] “Welcome to the Black Parade” in?’ It\'s not really an anthem—I don\'t know. I love tricking people with a vibe and then completely shifting. I feel like I want to do that more.”

HAIM only had one rule when they started working on their third album: There would be no rules. “We were just experimenting,” lead singer and middle sibling Danielle Haim tells Apple Music. “We didn’t care about genre or sticking to any sort of script. We have the most fun when nothing is off limits.” As a result, *Women in Music Pt. III* sees the Los Angeles sisters embrace everything from thrillingly heavy guitar to country anthems and self-deprecating R&B. Amid it all, gorgeous saxophone solos waft across the album, transporting you straight to the streets of their hometown on a sunny day. In short, it’s a fittingly diverse effort for a band that\'s always refused, in the words of Este Haim, to be “put in a box.” “I just hope people can hear how much fun we had making it,” adds Danielle, who produced the album alongside Rostam Batmanglij and Ariel Rechtshaid—a trio Alana Haim describes as “the Holy Trinity.” “We wanted it to sound fun. Everything about the album was just spontaneous and about not taking ourselves too seriously.” Yet, as fun-filled as they might be, the tracks on *Women in Music Pt. III* are also laced with melancholy, documenting the collective rock bottom the Haim sisters hit in the years leading up to the album’s creation. These songs are about depression, seeking help, grief, failing relationships, and health issues (Este has type 1 diabetes). “A big theme in this album is recognizing your sadness and expelling it with a lot of aggression,” says Danielle, who wanted the album to sound as raw and up close as the subjects it dissects. “It feels good to scream it in song form—to me that’s the most therapeutic thing I can do.” Elsewhere, the band also comes to terms with another hurdle: being consistently underestimated as female musicians. (The album’s title, they say, is a playful “invite” to stop asking them about being women in music.) The album proved to be the release they needed from all of those experiences—and a chance to celebrate the unshakable sibling support system they share. “This is the most personal record we’ve ever put out,” adds Alana. “When we wrote this album, it really did feel like collective therapy. We held up a mirror and took a good look at ourselves. It’s allowed us to move on.” Let HAIM guide you through *Women in Music Pt. III*, one song at a time. **Los Angeles** Danielle Haim: “This was one of the first songs we wrote for the album. It came out of this feeling when we were growing up that Los Angeles had a bad rep. It was always like, ‘Ew, Los Angeles!’ or ‘Fuck LA!’ Especially in 2001 or so, when all the music was coming out of New York and all of our friends ended up going there for college. And if LA is an eyeroll, the Valley—where we come from—is a constant punchline. But I always had such pride for this city. And then when our first album came out, all of a sudden, the opinion of LA started to change and everyone wanted to move here. It felt a little strange, and it was like, ‘Maybe I don’t want to live here anymore?’ I’m waiting for the next mass exodus out of the city and people being like, ‘This place sucks.’ Anyone can move here, but you’ve got to have LA pride from the jump.” **The Steps** Danielle: “With this album, we were reckoning with a lot of the emotions we were feeling within the business. This album was kind of meant to expel all of that energy and almost be like ‘Fuck it.’ This song kind of encapsulates the whole mood of the record. The album and this song are really guitar-driven \[because\] we just really wanted to drive that home. Unfortunately, I can already hear some macho dude being like, ‘That lick is so easy or simple.’ Sadly, that’s shit we’ve had to deal with. But I think this is the most fun song we’ve ever written. It’s such a live, organic-sounding song. Just playing it feels empowering.” Este Haim: “People have always tried to put us in a box, and they just don’t understand what we do. People are like, ‘You dance and don’t play instruments in your videos, how are you a band?’ It’s very frustrating.” **I Know Alone** Danielle: “We wrote this one around the same time that we wrote ‘Los Angeles,’ just in a room on GarageBand. Este came up with just that simple bassline. And we kind of wrote the melody around that bassline, and then added those 808 drums in the chorus. It’s about coming out of a dark place and feeling like you don\'t really want to deal with the outside world. Sometimes for me, being at home alone is the most comforting. We shout out Joni Mitchell in this song; our mom was such a huge fan of hers and she kind of introduced us to her music when we were really little. I\'d always go into my room and just blast Joni Mitchell super loud. And I kept finding albums of hers as we\'ve gotten older and need it now. I find myself screaming to slow Joni Mitchell songs in my car. This song is very nostalgic for her.” **Up From a Dream** Danielle: “This song literally took five minutes to write, and it was written with Rostam. It’s about waking up to a reality that you just don’t want to face. In a way, I don’t really want to explain it: It can mean so many different things to different people. This is the heaviest song we’ve ever had. It’s really cool, and I think this one will be really fun to play live. The guitar solo alone is really fun.” **Gasoline** Danielle: “This was another really quick one that we wrote with Rostam. The song was a lot slower originally, and then we put that breakbeat-y drumbeat on it and all of a sudden it turned into a funky sort of thing, and it really brought the song to life. I love the way that the drums sound. I feel like we really got that right. I was like literally in a cave of blankets, a fort we created with a really old Camco drum set from the ’70s, to make sure we got that dry, tight drum sound. That slowed-down ending is due to Ariel. He had this crazy EDM filter he stuck on the guitar, and I was like, ‘Yes, that’s fucking perfect.’” Alana Haim: “I think there were parts of that song where we were feeling sexy. I remember I had gone to go get food, and when I came back Danielle had written the bridge. She was like, ‘Look what I wrote!’ And I was like, ‘Oh! Okay!’” **3 AM** Alana: “It’s pretty self-explanatory—it’s about a booty call. There have been around 10 versions of this song. Someone was having a booty call. It was probably me, to be honest. We started out with this beat, and then we wrote the chorus super quickly. But then we couldn’t figure out what to do in the verses. We’d almost given up on it and then we were like, ‘Let’s just try one last time and see if we can get there.’ I think it was close to 3 am when we figured out the verse and we had this idea of having it introduced by a phone call. Because it *is* about a booty call. And we had to audition a bunch of dudes. We basically got all of our friends that were guys to be like, ‘Hey, this is so crazy, but can you just pretend to be calling a girl at 3 am?’ We got five or six of our friends to do it, and they were so nervous and sheepish. They were the worst! I was like, ‘Do you guys even talk to girls?’ I think you can hear the amount of joy and laughs we had making this song.” **Don’t Wanna** Alana: “I think this is classic HAIM. It was one of the earlier songs which we wrote around the same time as ‘Now I’m in It.’ We always really, really loved this song, and it always kind of stuck its head out like, ‘Hey, remember me?’ It just sounded so good being simple. We can tinker around with a song for years, and with this one, every time we added something or changed it, it lost the feeling. And every time we played it, it just kind of felt good. It felt like a warm sweater.” **Another Try** Alana: “I\'ve always wanted to write a song like this, and this is my favorite on the record. The day that we started it, I was thinking that I was going to get back together with the love of my life. I mean, now that I say that, I want to barf, because we\'re not in a good place now, but at that point we were. We had been on and off for almost 10 years and I thought we were going to give it another try. And it turns out, the week after we finished the song, he had gotten engaged. So the song took on a whole new meaning very quickly. It’s really about the fact I’ve always been on and off with the same person, and have only really had one love of my life. It’s kind of dedicated to him. I think Ariel had a lot of fun producing this song. As for the person it’s about? He doesn’t know about it, but I think he can connect the dots. I don’t think it’s going to be very hard to figure out. The end of the song is supposed to feel like a celebration. We wanted it to feel like a dance party. Because even though it has such a weird meaning now, the song has a hopeful message. Who knows? Maybe one day we’ll figure it out. I am still hopeful.” **Leaning on You** Alana: “This is really a song about finding someone that accepts your flaws. That’s such a rare thing in this world—to find someone you love that accepts you as who you are and doesn\'t want to change you. As sisters, we are the CEOs of our company: We have super strong personalities and really strong opinions. And finding someone that\'s okay with that, you would think would be celebrated, but it\'s actually not. It\'s really hard to find someone that accepts you and accepts what you do as a job and accepts everything about you. And I think ‘Leaning on You’ is about when you find that person that really uplifts you and finds everything that you do to be incredible and interesting and supports you. It’s a beautiful thing.” Danielle: “We wrote this song just us sitting around a guitar. And we just wanted to keep it like that, so we played acoustic guitar straight into the computer for a very dry, unique sound that I love.” **I’ve Been Down** Danielle: “This is the last one we wrote on the album. This was super quick with stream-of-consciousness lyrics. I wanted it to sound like you were in the room, like you were right next to me. That chorus—‘I’ve been down, I’ve been down’—feels good to sing. It\'s very therapeutic to just kind of scream it in song form. To me, it’s the most therapeutic thing I can do. The backing vocals on this are like the other side of your brain.” **Man From the Magazine** Este: \"When we were first coming out, I guess it was perplexing for some people that I would make faces when I played, even though men have been doing it for years. When they see men do it, they are just, to quote HAIM, ‘in it.’ But of course, when a woman does it, it\'s unsettling and off-putting and could be misconstrued as something else. We got asked questions about it early on, and there was this one interviewer who asked if I made the faces I made onstage in bed. Obviously he wasn’t asking about when I’m in bed yawning. My defense mechanism when stuff like that happens is just to try to make a joke out of it. So I kind of just threw it back at him and said, ‘Well, there\'s only one way to find out.’ And of course, there was a chuckle and then we moved on. Now, had someone said that to me, I probably would\'ve punched them in the face. But as women, we\'re taught kind of just to always be pleasant and be polite. And I think that was my way of being polite and nice. Thank god things are changing a bit. We\'ve been talking about shit like this forever, but I think now, finally, people are able to listen more intently.” Danielle: “We recorded this song in one take. We got the feeling we wanted in the first take. The first verse is Este\'s super specific story, and then, on the second verse, it feels very universal to any woman who plays music about going into a guitar store or a music shop and immediately either being asked, ‘Oh, do you want to start to play guitar?’ or ‘Are you looking for a guitar for your boyfriend?’ And you\'re like, ‘What the fuck?’ It\'s the worst feeling. And I\'ve talked to so many other women about the same experience. Everyone\'s like, ‘Yeah, it\'s the worst. I hate going in the guitar stores.’ It sucks.” **All That Ever Mattered** Alana: “This is one of the more experimental songs on the record. Whatever felt good on this track, we just put it in. And there’s a million ways you could take this song—it takes on a life of its own and it’s kind of chaotic. The production is bananas and bonkers, but it did really feel good.” Danielle: “It’s definitely a different palette. But to us it was exciting to have that crazy guitar solo and those drums. It also has a really fun scream on it, which I always like—it’s a nice release.” **FUBT** Alana: “This song was one of the ones that was really hard to write. It’s about being in an emotionally abusive relationship, which all three of us have been in. It’s really hard to see when you\'re in something like that. And the song basically explains what it feels like and just not knowing how to get out of it. You\'re just kind of drowning in this relationship, because the highs are high and the lows are extremely low. You’re blind to all these insane red flags because you’re so immersed in this love. And knowing that you\'re so hard on yourself about the littlest things. But your partner can do no wrong. When we wrote this song, we didn’t really know where to put it. But it felt like the end to the chapter of the record—a good break before the next songs, which everyone knew.” **Now I’m in It** Danielle: “This song is about feeling like you\'re in something and almost feeling okay to sit in it, but also just recognizing that you\'re in a dark place. I was definitely in a dark place, and it was just like I had to look at myself in the mirror and be like, ‘Yeah, this is fucked up. And you need to get your shit together and you need to look it in the face and know that you\'re here and work on yourself.’ After writing this song I got a therapist, which really helped me.” **Hallelujah** Alana: “This song really did just come from wanting to express how important it is to have the love of your family. We\'re very lucky that we each have two sisters as backup always. We wrote this with our friend Tobias Jesso Jr., and we all just decided to write verses separately, which is rare for us. I think we each wanted to have our own take on the lyric ‘Why me, how\'d I get this hallelujah’ and what it meant to each of us. I wrote about losing a really close friend of mine at such a young age and going through a tragedy that was unexplainable. I still grapple with the meaning of that whole thing. It was one of the hardest times in my life, and it still is, but I was really lucky that I had two siblings that were really supportive during that time and really helped me get through it. If you talk to anybody that loses someone unexpectedly, you really do become a different person. I feel like I\'ve had two chapters of my life at this point: before it happened and after it happened. And I’ve always wanted to thank my sisters at the same time because they were so integral in my healing process going through something so tragic.” **Summer Girl** Alana: This song is collectively like our baby. Putting it out was really fun, but it was also really scary, because we were coming back and we didn’t know how people were going to receive it. We’d played it to people and a lot of them didn’t really like it. But we loved everything about it. You can lose your confidence really quickly, but thankfully, people really liked it. Putting out this song really did give us back our confidence.” Danielle: “I\'ve talked about it a lot, but this song is about my boyfriend getting cancer a couple of years ago, and it was truly the scariest thing that I have ever been through. I just couldn\'t stop thinking about how he was feeling. I get spooked really easily, but I felt like I had to buck the fuck up and be this kind of strong figure for him. I had to be this kind of sunshine, which was hard for me, but I feel like it really helped him. And that’s kind of where this song came from. Being the summer when he was just in this dark, dark place.”

If I Break Horses’s third album holds you in its grip like a great film, it’s no coincidence. Faced with making the follow-up to 2014’s plush Chiaroscuro, Horses’s Maria Lindén decided to take the time to make something different, with an emphasis on instrumental, cinematic music. As she watched a collection of favourite films on her computer (sound muted) and made her own soundtrack sketches, these sonic workouts gradually evolved into something more: “It wasn’t until I felt an urge to add vocals and lyrics,” says Lindén, “that I realized I was making a new I Break Horses album.” That album is Warnings, an intimate and sublimely expansive return that, as its recording suggests, sets its own pace with the intuitive power of a much-loved movie. And, as its title suggests, its sumptuous sound worlds – dreamy mellotrons, haunting loops, analogue synths – and layered lyrics crackle with immersive dramatic tensions on many levels. “It’s not a political album,” says Lindén, “though it relates to the alarmist times we live in. Each song is a subtle warning of something not being quite right.” As Lindén notes, the process of making Warnings involved different kinds of dramas. “It has been some time in the making. About five years, involving several studios, collaborations that didn’t work out, a crashed hard drive with about two years of work, writing new material again instead of trying to repair it. New studio recordings, erasing everything, then recording most of the album myself at home…” Yet the pay-off for her long-haul immersion is clear from statement-of-intent album opener ‘Turn’, a waltzing kiss-off to an ex swathed in swirling synths over nine emotive minutes. On ‘Silence’, Lindén suggests deeper sorrows in the interplay of serene surface synths, hypnotic loops and elemental images: when she sings “I feel a shiver,” you feel it, too. Elsewhere, on three instrumental interludes, Lindén’s intent to experiment with sound and structure is clear. Meanwhile, there are art-pop songs here more lush than any she has made. ‘I’ll Be the Death of You’ occupies a middle ground between Screamedelica and early OMD, while ‘Neon Lights’ brings to mind Kraftwerk on Tron’s light grid. ‘I Live At Night’ slow-burns like a song made for night-time LA drives; ‘Baby You Have Travelled for Miles without Love in Your Eyes’ is an electronic lullaby spiked with troubling needle imagery. ‘Death Engine’’s dark-wave dream-pop provides an epic centrepiece, of sorts, before the vocoder hymnal of closer ‘Depression Tourist’ arrives like an epiphany, the clouds parting after a long, absorbing journey. For Lindén, Warnings is a remarkable re-routing of a journey begun when I Break Horses’s debut album, Hearts (2011), drew praise from Pitchfork, The Guardian, NME, The Independent and others for its luxurious grandeur and pulsing sense of art-pop life. With the electro-tangents of 2014’s Chiaroscuro, Lindén forged a new, more ambitious voice with total confidence. Along the way, I Break Horses toured with M83 and Sigur Rós; latterly, U2 played Hearts’ ecstatic ‘Winter Beats’ through the PA before their stage entrance on 2018’s ‘Experience + Innocence’ tour. Good choice. A new friend on Warnings is US producer/mixing engineer Chris Coady, whose graceful way with dense sound (credits include Beach House, TV on the Radio) was not the sole reason Lindén invited him to mix the album. “Before reaching out to Chris I read an interview where he said, ‘I like to slow things down. Almost every time I love the sound of something slowed down by half, but sometimes 500% you can get interesting shapes and textures.’ And I just knew he’d be the right person for this album.” If making Warnings was a slow process, so be it: that steady gestation was a price worth paying for its lavish accretions of detail and meaning, where secrets aplenty await listeners eager to immerse themselves. “Nowadays, the attention span equals nothing when it comes to how most people consume music,” Lindén says. “And it feels like songs are getting shorter, more ‘efficient’. I felt an urge to go against that and create an album journey from start to finish that takes time and patience to listen to. Like, slow the fuck down!” Happily, Warnings provides all the incentives required.

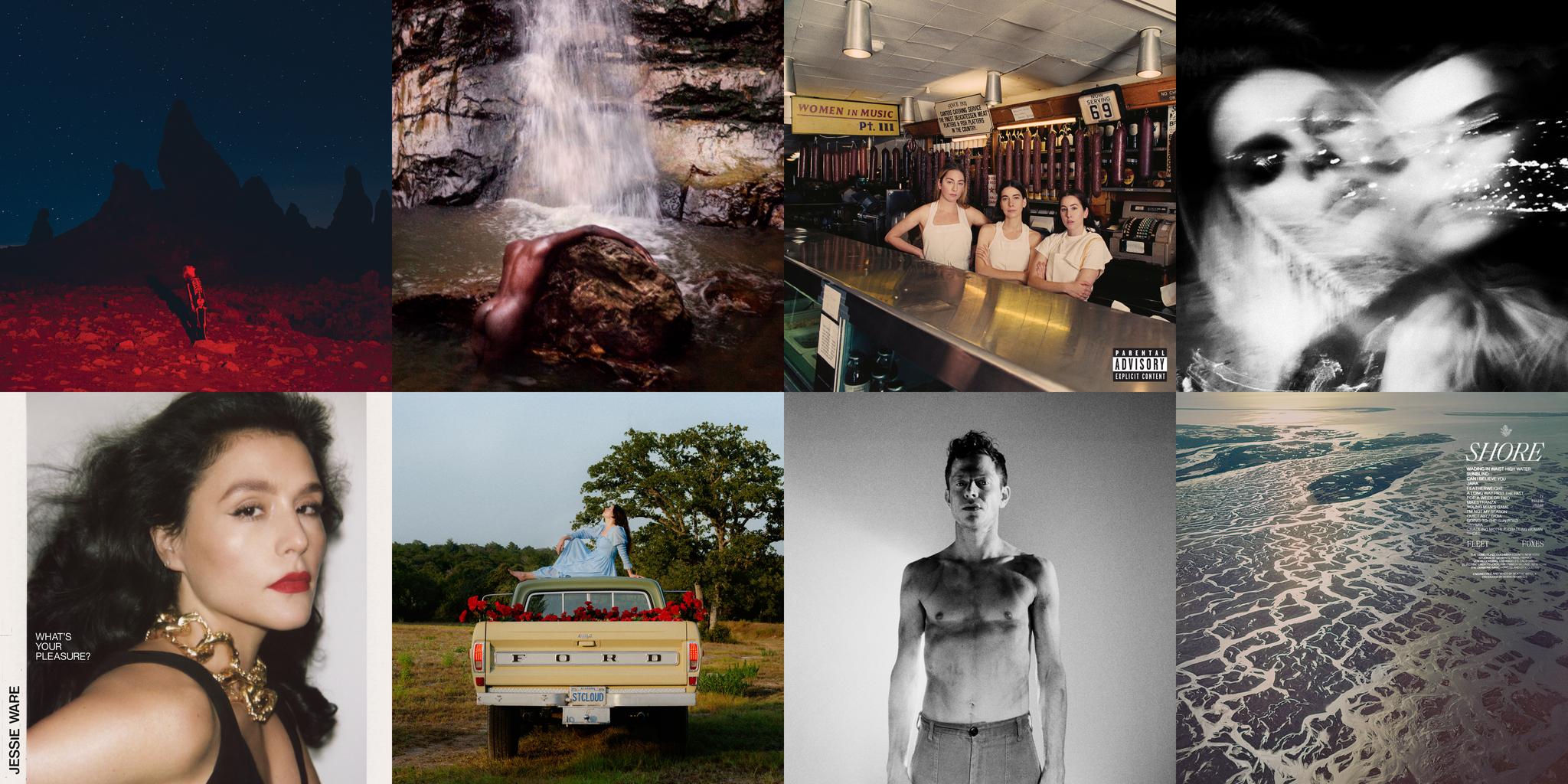

When it came to crafting her fourth album, Jessie Ware had one word in mind. “Escapism,” the Londoner tells Apple Music of *What’s Your Pleasure?*, a collection of suitably intoxicating soul- and disco-inspired pop songs to transport you out of your everyday and straight onto a crowded dance floor. “I wanted it to be fun. The premise was: Will this make people want to have sex? And will this make people want to dance? I’ve got a family now, so going out and being naughty and debauched doesn’t happen that much.” And yet the singer (and, in her spare time, wildly popular podcaster) could have never foreseen just how much we would *all* be in need of that release by the time *What’s Your Pleasure?* came to be heard—amid a global pandemic and enforced lockdowns in countless countries. “A lot of shit is going on,” says Ware. “As much as I don’t think I’m going to save the world with this record, I do think it provides a bit of escapism. By my standards, this album is pretty joyful.” Indeed, made over two years with Simian Mobile Disco’s James Ford and producers including Clarence Coffee Jr. (Dua Lipa, Lizzo) and Joseph Mount of Metronomy, *What’s Your Pleasure?* is a world away from the heartfelt balladry once synonymous with Ware. Here, pulsating basslines reign supreme, as do whispered vocals, melodramatic melodies, and winking lyrics. At times, it’s a defiant throwback to the dance scene that first made Ware famous (“I wanted people to think, ‘When is she going to calm this album down?’”); at others, it’s a thrilling window into what might come next (note “Remember Where You Are,” the album’s gorgeous, Minnie Riperton-esque outro). But why the sudden step change? “A low point in music” and \"a shitty time,” says Ware, nodding to a 2018 tour that left her feeling so disillusioned with her day job that her mother suggested she quit singing altogether. “I needed a palate cleanser to shock the system. I needed to test myself. I needed to be reminded that music should be fun.” *What’s Your Pleasure?*, confirms Ware, has more than restored the spring in her step. “I feel like what I can do after this is limitless,” she says. “That’s quite a different situation to how I felt during the last album. Now, I have a newfound drive. I feel incredibly empowered, and it’s an amazing feeling.” Here\_,\_ Let Ware walk you through her joyous fourth record, one song at a time. **Spotlight** “I wrote this in the first writing session. James was playing the piano and we were absolutely crooning. That’s what the first bit of this song is—which really nods to musical theater and jazz. We thought about taking it out, but then I realized that the theatrical aspect is kind of essential. The album had to have that light and shade. It also felt like a perfect entry point because of that intro. It’s like, ‘Come into my world.’ I think it grabs you. It’s also got a bit of the old Jessie in there, with that melancholy. This song felt like a good indicator of where the rest of the album was going to go. That’s why it felt right to start the record with that.” **What’s Your Pleasure?** “We had been writing and writing all day, and nothing was working. We\'d gone for a lunch, and we were like, ‘You know, sometimes this happens.’ Later, we were just messing about, and I was like, ‘I really want to imagine that I\'m in the Berghain and I want to imagine that I\'m dancing with someone and they are so suggestive, and anything goes.’ It\'s sex, it\'s desire, it\'s temptation. We were like, ‘Let’s do this as outrageously as possible.’ So we imagined we were this incredibly confident person who could just say anything. When we wrote it, it just came out—20 minutes and then it was done. James came up with that amazing beat, which almost reminds me of a DJ Shadow song. We were giggling the whole time we were writing it. It\'s quite poppy accidentally, but I think with the darkness of all the synths, it’s just the perfect combination.” **Ooh La La** “This is another very cheeky one. It’s very much innuendo. In my head, there are these prim and proper lovers—it’s all very polite, but actually there’s no politeness about. So it’s quite a naughty number. The song has got an absolute funk to it, but it’s really catchy and it’s still quite quirky. It’s not me letting rip on the vocal. It’s actually quite clipped.” **Soul Control** “I had Janet Jackson in my head in this one. It’s a really energetic number. There is a sense of indulgence in these songs, because I wasn’t trying to play to a radio edit and I was really relishing that. But it’s not self-indulgent, because it’s very much fun. These are the highest tempos I’ve ever done, and I think I surprised myself by doing that. I wanted to keep the energy up—I wanted people to think, ‘When is she going to calm this album down?’” **Save a Kiss** “It’s funny because I was a bit scared of this song. I remember Ed Sheeran telling me, ‘When you get a bit scared by a song, it usually means that there’s something really good in it.’ My fans like emotion from me, so I wanted to do a really emotive dance song. We just wanted it to feel as bare as possible and really feel like the lyrics and the melody could really like sing out on this one. We had loads of other production in it, and it was very much like a case of James and I stripping everything back. It was the hardest one to get right. But I’m very excited about playing it. It has the yearning and the wanting that I feel my fans want, and I just wanted it to feel a bit over the top. I also wanted this song to have a bit of Kate Bush in there and some of the drama of her music.” **Adore You** “I wrote this when I got pregnant. It was my first session with Joseph Mount and I was a bit awkward and he was a bit awkward. When I\'m really nervous I sing really quietly because I don\'t want people to hear anything. But that actually kind of worked. I love this—it shows a vulnerability and a softness. Actually it was me thinking about my unborn child and thinking about, like, I\'m falling for you and this bump and feeling like it\'s going to be a reality soon. I think Joe did such an amazing job on just making it feel hypnotic and still romantic and tender, but with this kind of mad sound. I think it’s a really beautiful song. It was supposed to be an offering before I went away and had a baby, to tell my fans that I’ll be back. They really loved it and I thought, ‘I can\'t not put this on the record, because it\'s like it\'s an important song for the journey of this album.’ I’m really proud of the fact that this is a pure collaboration, and I have such fond memories of it.” **In Your Eyes** “This was the first song that me and James wrote for this whole album. I think you can feel the darkness in it. And that maybe I was feeling the resentment and torturing myself. I think that the whirring arpeggio and the beats in this song very much suggest that it’s a stream of consciousness. There’s a desperation about it. I think that was very much the time and place that I was in. I’m very proud of this song, and it’s actually one of my favorites. Jules Buckley did such an amazing job on the strings—it makes me feel like we\'re in a Bond film or something. But it was very much coming off the back of having quite a low point in music.” **Step Into My Life** “I made this song with \[London artist\] Kindness \[aka Adam Bainbridge\]. I’ve known them for a long time. In my head I wanted that almost R&B delivery with the verse and for it to feel really intimate and kind of predatory, but with this very disco moment in the chorus. I love that Adam’s voice is in there, in the breakdown. It feels like a conversation—the song is pure groove and attitude. You can’t help but nod your head. It feels like one that you can play at the beginning of a party and get people on the dance floor.” **Read My Lips** “James and I did this one on our own, and it’s supposed to be quite bubblegummy. We were giving a nod to \[Lisa Lisa & Cult Jam with Full Force song\] ‘I Wonder If I Take You Home.’ The bassline in this song is so good. We also recorded my vocal slower and lower, so that when you turn it back to normal speed, the vocals sound more cutesy because it sounds brighter and higher. I wanted it to sound slightly squeaky. My voice is naturally quite low and melancholic, so I don’t know how I’m going to sing this one live. I’ll have to pinch my nose or something!” **Mirage (Don’t Stop)** “The bassline here is ridiculous! That’s down to Matt Tavares \[of BADBADNOTGOOD\]. He’s a multi-instrumentalist and is just so talented and enthusiastic, and I also wrote this with \[British DJ and producer\] Benji B and \[US producer\] Clarence Coffee Jr. I think it really signified that I had got my confidence and my mojo back when I went into that session. Usually I\'d be like, ‘Oh, my god, I can\'t do this with new people.’ But it just clicked as sometimes it does. I was unsure about whether the lyric ‘Don\'t stop moving’ felt too obvious. But Benji B was very much like, ‘No, man. You want people to dance. It’s the perfect message.’ And I think of Benji B as like the cool-ometer. So I was like, \'Cool, if Benji B thinks it cool, then I\'m okay with that.’” **The Kill** “There’s an almost hypnotic element to this song. It’s very dark, almost like the end of the night when things are potentially getting too loose. It’s also a difficult one to talk about. It’s about someone feeling like they know you well—maybe too well. There are anxieties in there, and it\'s meant to be cinematic. I wanted that relentlessly driving feeling like you\'d be in a car and you just keep going on, like you’re almost running away from something. Again, Jules Buckley did an amazing job with the strings here—I wanted it to sound almost like it was verging on Primal Scream or Massive Attack. And live, it could just build and build and build. There is, though, a lightness at the end of it, and an optimism—like you’re clawing your way out of this darkness.” **Remember Where You Are** “I’m incredibly proud of this song. I wrote it when Boris Johnson had just got into Downing Street and things were miserable. Everything that could be going wrong was going wrong, which is behind the lyric ‘The heart of the city is on fire.’ And it sounds relatively upbeat, but actually, it\'s about me thinking, ‘Remember where you are. Remember that just a cuddle can be okay. Remember who’s around you.’ Also, it was very much a semi-sign-off and about saying, ‘This is where I’m going and this is the most confident I’ve ever been.’ It was a bold statement. I think it stands up as one of the best songs I\'ve ever written.”

“Place and setting have always been really huge in this project,” Katie Crutchfield tells Apple Music of Waxahatchee, which takes its name from a creek in her native Alabama. “It’s always been a big part of the way I write songs, to take people with me to those places.” While previous Waxahatchee releases often evoked a time—the roaring ’90s, and its indie rock—Crutchfield’s fifth LP under the Waxahatchee alias finds Crutchfield finally embracing her roots in sound as well. “Growing up in Birmingham, I always sort of toed the line between having shame about the South and then also having deep love and connection to it,” she says. “As I started to really get into alternative country music and Lucinda \[Williams\], I feel like I accepted that this is actually deeply in my being. This is the music I grew up on—Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, the powerhouse country singers. It’s in my DNA. It’s how I learned to sing. If I just accept and embrace this part of myself, I can make something really powerful and really honest. I feel like I shed a lot of stuff that wasn\'t serving me, both personally and creatively, and it feels like *Saint Cloud*\'s clean and honest. It\'s like this return to form.” Here, Crutchfield draws us a map of *Saint Cloud*, with stories behind the places that inspired its songs—from the Mississippi to the Mediterranean. WEST MEMPHIS, ARKANSAS “Memphis is right between Birmingham and Kansas City, where I live currently. So to drive between the two, you have to go through Memphis, over the Mississippi River, and it\'s epic. That trip brings up all kinds of emotions—it feels sort of romantic and poetic. I was driving over and had this idea for \'**Fire**,\' like a personal pep talk. I recently got sober and there\'s a lot of work I had to do on myself. I thought it would be sweet to have a song written to another person, like a traditional love song, but to have it written from my higher self to my inner child or lower self, the two selves negotiating. I was having that idea right as we were over the river, and the sun was just beating on it and it was just glowing and that lyric came into my head. I wanted to do a little shout-out to West Memphis too because of \[the West Memphis Three\]—that’s an Easter egg and another little layer on the record. I always felt super connected to \[Damien Echols\], watching that movie \[*Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills*\] as a teenager, just being a weird, sort of dark kid from the South. The moment he comes on the screen, I’m immediately just like, ‘Oh my god, that guy is someone I would have been friends with.’ Being a sort of black sheep in the South is especially weird. Maybe that\'s just some self-mythology I have, like it\'s even harder if you\'re from the South. But it binds you together.” BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA “Arkadelphia Road is a real place, a road in Birmingham. It\'s right on the road of this little arts college, and there used to be this gas station where I would buy alcohol when I was younger, so it’s tied to this seediness of my past. A very profound experience happened to me on that road, but out of respect, I shouldn’t give the whole backstory. There is a person in my life who\'s been in my life for a long time, who is still a big part of my life, who is an addict and is in recovery. It got really bad for this person—really, really bad. \[\'**Arkadelphia**\'\] is about when we weren’t in recovery, and an experience that we shared. One of the most intense, personal songs I\'ve ever written. It’s about growing up and being kids and being innocent and watching this whole crazy situation play out while I was also struggling with substances. We now kind of have this shared recovery language, this shared crazy experience, and it\'s one of those things where when we\'re in the same place, we can kind of fit in the corner together and look at the world with this tent, because we\'ve been through what we\'ve been through.” RUBY FALLS, TENNESSEE “It\'s in Chattanooga. A waterfall that\'s in a cave. My sister used to live in Chattanooga, and that drive between Birmingham and Chattanooga, that stretch of land between Alabama, Georgia, into Tennessee, is so meaningful—a lot of my formative time has been spent driving that stretch. You pass a few things. One is Noccalula Falls, which I have a song about on my first album called ‘Noccalula.’ The other is Ruby Falls. \[‘**Ruby Falls**’\] is really dense—there’s a lot going on. It’s about a friend of mine who passed away from a heroin overdose, and it’s for him—my song for all people who struggle with that kind of thing. I sang a song at his funeral when he died. This song is just all about him, about all these different places that we talked about, or that we’d spend so much time at Waxahatchee Creek together. The beginning of the song is sort of meant to be like the high. It starts out in the sky, and that\'s what I\'m describing, as I take flight, up above everybody else. Then the middle part is meant to be like this flashback but it\'s taking place on earth—it’s actually a reference to *Just Kids*, Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe. It’s written with them in mind, but it\'s just about this infectious, contagious, intimate friendship. And the end of the song is meant to represent death or just being below the surface and being gone, basically.” ST. CLOUD, FLORIDA “It\'s where my dad is from, where he was born and where he grew up. The first part of \[\'**St. Cloud**\'\] is about New York. So I needed a city that was sort of the opposite of New York, in my head. I wasn\'t going to do like middle-of-nowhere somewhere; I really did want it to be a place that felt like a city. But it just wasn’t cosmopolitan. Just anywhere America, and not in a bad way—in a salt-of-the-earth kind of way. As soon as the idea to just call the whole record *Saint Cloud* entered my brain, it didn\'t leave. It had been the name for six months or something, and I had been calling it *Saint Cloud*, but then David Berman died and I was like, ‘Wow, that feels really kismet or something,’ because he changed his middle name to Cloud. He went by David Cloud Berman. I\'m a fan; it feels like a nice way to \[pay tribute\].” BARCELONA, SPAIN “In the beginning of\* \*‘**Oxbow**’ I say ‘Barna in white,’ and ‘Barna’ is what people call Barcelona. And Barcelona is where I quit drinking, so it starts right at the beginning. I like talking about it because when I was really struggling and really trying to get better—and many times before I actually succeeded at that—it was always super helpful for me to read about other musicians and just people I looked up to that were sober. It was during Primavera \[Sound Festival\]. It’s sort of notoriously an insane party. I had been getting close to quitting for a while—like for about a year or two, I would really be not drinking that much and then I would just have a couple nights where it would just be really crazy and I would feel so bad, and it affected all my relationships and how I felt about music and work and everything. I had the most intense bout of that in Barcelona right at the beginning of this tour, and as I was leaving I was going from there to Portugal and I just decided, ‘I\'m just going to not.’ I think in my head I was like, ‘I\'m actually done,’ but I didn\'t say that to everybody. And then that tour went into another tour, and then to the summer, and then before you know it I had been sober six months, and then I was just like, ‘I do not miss that at all.’ I\'ve never felt more like myself and better. It was the site of my great realization.”

Mike Hadreas’ fifth LP under the Perfume Genius guise is “about connection,” he tells Apple Music. “And weird connections that I’ve had—ones that didn\'t make sense but were really satisfying or ones that I wanted to have but missed or ones that I don\'t feel like I\'m capable of. I wanted to sing about that, and in a way that felt contained or familiar or fun.” Having just reimagined Bobby Darin’s “Not for Me” in 2018, Hadreas wanted to bring the same warmth and simplicity of classic 1950s and \'60s balladry to his own work. “I was thinking about songs I’ve listened to my whole life, not ones that I\'ve become obsessed over for a little while or that are just kind of like soundtrack moments for a summer or something,” he says. “I was making a way to include myself, because sometimes those songs that I love, those stories, don\'t really include me at all. Back then, you couldn\'t really talk about anything deep. Everything was in between the lines.” At once heavy and light, earthbound and ethereal, *Set My Heart on Fire Immediately* features some of Hadreas’ most immediate music to date. “There\'s a confidence about a lot of those old dudes, those old singers, that I\'ve loved trying to inhabit in a way,” he says. “Well, I did inhabit it. I don\'t know why I keep saying ‘try.’ I was just going to do it, like, ‘Listen to me, I\'m singing like this.’ It\'s not trying.” Here, he walks us through the album track by track. **Whole Life** “When I was writing that song, I just had that line \[‘Half of my whole life is done’\]—and then I had a decision afterwards of where I could go. Like, I could either be really resigned or I could be open and hopeful. And I love the idea. That song to me is about fully forgiving everything or fully letting everything go. I’ve realized recently that I can be different, suddenly. That’s been a kind of wild thing to acknowledge, and not always good, but I can be and feel completely different than I\'ve ever felt and my life can change and move closer to goodness, or further away. It doesn\'t have to be always so informed by everything I\'ve already done.” **Describe** “Originally, it was very plain—sad and slow and minimal. And then it kind of morphed, kind of went to the other side when it got more ambient. When I took it into the studio, it turned into this way dark and light at the same time. I love that that song just starts so hard and goes so full-out and doesn\'t let up, but that the sentiment and the lyric and my singing is still soft. I was thinking about someone that was sort of near the end of their life and only had like 50% of their memories, or just could almost remember. And asking someone close to them to fill the rest in and just sort of remind them what happened to them and where they\'ve been and who they\'d been with. At the end, all of that is swimming together.” **Without You** “The song is about a good moment—or even just like a few seconds—where you feel really present and everything feels like it\'s in the right place. How that can sustain you for a long time. Especially if you\'re not used to that. Just that reminder that that can happen. Even if it\'s brief, that that’s available to you is enough to kind of carry you through sometimes. But it\'s still brief, it\'s still a few seconds, and when you tally everything up, it\'s not a lot. It\'s not an ultra uplifting thing, but you\'re not fully dragged down. And I wanted the song to kind of sound that same way or at least push it more towards the uplift, even if that\'s not fully the sentiment.” **Jason** “That song is very much a document of something that happened. It\'s not an idea, it’s a story. Sometimes you connect with someone in a way that neither of you were expecting or even want to connect on that level. And then it doesn\'t really make sense, but you’re able to give each other something that the other person needs. And so there was this story at a time in my life where I was very selfish. I was very wild and reckless, but I found someone that needed me to be tender and almost motherly to them. Even if it\'s just for a night. And it was really kind of bizarre and strange and surreal, too. And also very fueled by fantasy and drinking. It\'s just, it\'s a weird therapeutic event. And then in the morning all of that is just completely gone and everybody\'s back to how they were and their whole bundle of shit that they\'re dealing with all the time and it\'s like it never happened.” **Leave** “That song\'s about a permanent fantasy. There\'s a place I get to when I\'m writing that feels very dramatic, very magical. I feel like it can even almost feel dark-sided or supernatural, but it\'s fleeting, and sometimes I wish I could just stay there even though it\'s nonsense. I can\'t stay in my dark, weird piano room forever, but I can write a song about that happening to me, or a reminder. I love that this song then just goes into probably the poppiest, most upbeat song that I\'ve ever made directly after it. But those things are both equally me. I guess I\'m just trying to allow myself to go all the places that I instinctually want to go. Even if they feel like they don\'t complement each other or that they don\'t make sense. Because ultimately I feel like they do, and it\'s just something I told myself doesn\'t make sense or other people told me it doesn\'t make sense for a long time.” **On the Floor** “It started as just a very real song about a crush—which I\'ve never really written a song about—and it morphed into something a little darker. A crush can be capable of just taking you over and can turn into just full projection and just fully one-sided in your brain—you think it\'s about someone else, but it\'s really just something for your brain to wild out on. But if that\'s in tandem with being closeted or the person that you like that\'s somehow being wrong or not allowed, how that can also feel very like poisonous and confusing. Because it\'s very joyous and full of love, but also dark and wrong, and how those just constantly slam against each other. I also wanted to write a song that sounded like Cyndi Lauper or these pop songs, like, really angsty teenager pop songs that I grew up listening to that were really helpful to me. Just a vibe that\'s so clear from the start and sustained and that every time you hear it you instantly go back there for your whole life, you know?” **Your Body Changes Everything** “I wrote ‘Your Body Changes Everything’ about the idea of not bringing prescribed rules into connection—physical, emotional, long-term, short-term—having each of those be guided by instinct and feel, and allowed to shift and change whenever it needed to. I think of it as a circle: how you can be dominant and passive within a couple of seconds or at the exact same time, and you’re given room to do that and you’re giving room to someone else to do that. I like that dynamic, and that can translate into a lot of different things—into dance or sex or just intimacy in general. A lot of times, I feel like I’m supposed to pick one thing—one emotion, one way of being. But sometimes, I’m two contradicting things at once. Sometimes, it seems easier to pick one, even if it’s the worse one, just because it’s easier to understand. But it’s not for me.” **Moonbend** “That\'s a very physical song to me. It\'s very much about bodies, but in a sort of witchy way. This will sound really pretentious, but I wasn\'t trying to write a chorus or like make it like a sing-along song, I was just following a wave. So that whole song feels like a spell to me—like a body spell. I\'m not super sacred about the way things sound, but I can be really sacred about the vibe of it. And I feel like somehow we all clicked in to that energy, even though it felt really personal and almost impossible to explain, but without having to, everybody sort of fell into it. The whole thing was really satisfying in a way that nobody really had to talk about. It just happened.” **Just a Touch** “That song is like something I could give to somebody to take with them, to remember being with me when we couldn\'t be with each other. Part of it\'s personal and part of it I wasn\'t even imagining myself in that scenario. It kind of starts with me and then turns into something, like a fiction in a way. I wanted it to be heavy and almost narcotic, but still like honey on the body or something. I don\'t want that situation to be hot—the story itself and the idea that you can only be with somebody for a brief amount of time and then they have to leave. You don\'t want anybody that you want to be with to go. But sometimes it\'s hot when they\'re gone. It’s hard to be fully with somebody when they\'re there. I take people for granted when they\'re there, and I’m much less likely to when they\'re gone. I think everybody is like that, but I might take it to another level sometimes.” **Nothing at All** “There\'s just some energetic thing where you just feel like the circle is there: You are giving and receiving or taking, and without having to say anything. But that song, ultimately, is about just being so ready for someone that whatever they give you is okay. They could tell you something really fucked up and you\'re just so ready for them that it just rolls off you. It\'s like we can make this huge dramatic, passionate thing, but if it\'s really all bullshit, that\'s totally fine with me too. I guess because I just needed a big feeling. I don\'t care in the end if it\'s empty.” **One More Try** “When I wrote my last record, I felt very wild and the music felt wild and the way that I was writing felt very unhinged. But I didn\'t feel that way. And with this record I actually do feel it a little, but the music that I\'m writing is a lot more mature and considered. And there\'s something just really, really helpful about that. And that song is about a feeling that could feel really overwhelming, but it\'s written in a way that feels very patient and kind.” **Some Dream** “I think I feel very detached a lot of the time—very internal and thinking about whatever bullshit feels really important to me, and there\'s not a lot of room for other people sometimes. And then I can go into just really embarrassing shame. So it\'s about that idea, that feeling like there\'s no room for anybody. Sometimes I always think that I\'m going to get around to loving everybody the way that they deserve. I\'m going to get around to being present and grateful. I\'m going to get around to all of that eventually, but sometimes I get worried that when I actually pick my head up, all those things will be gone. Or people won\'t be willing to wait around for me. But at the same time that I feel like that\'s how I make all my music is by being like that. So it can be really confusing. Some of that is sad, some of that\'s embarrassing, some of that\'s dramatic, some of it\'s stupid. There’s an arc.” **Borrowed Light** “Probably my favorite song on the record. I think just because I can\'t hear it without having a really big emotional reaction to it, and that\'s not the case with a lot of my own songs. I hate being so heavy all the time. I’m very serious about writing music and I think of it as this spiritual thing, almost like I\'m channeling something. I’m very proud of it and very sacred about it. But the flip side of that is that I feel like I could\'ve just made that all up. Like it\'s all bullshit and maybe things are just happening and I wasn\'t anywhere before, or I mean I\'m not going to go anywhere after this. This song\'s about what if all this magic I think that I\'m doing is bullshit. Even if I feel like that, I want to be around people or have someone there or just be real about it. The song is a safe way—or a beautiful way—for me to talk about that flip side.”

AN IMPRESSION OF PERFUME GENIUS’ SET MY HEART ON FIRE IMMEDIATELY By Ocean Vuong Can disruption be beautiful? Can it, through new ways of embodying joy and power, become a way of thinking and living in a world burning at the edges? Hearing Perfume Genius, one realizes that the answer is not only yes—but that it arrived years ago, when Mike Hadreas, at age 26, decided to take his life and art in to his own hands, his own mouth. In doing so, he recast what we understand as music into a weather of feeling and thinking, one where the body (queer, healing, troubled, wounded, possible and gorgeous) sings itself into its future. When listening to Perfume Genius, a powerful joy courses through me because I know the context of its arrival—the costs are right there in the lyrics, in the velvet and smoky bass and synth that verge on synesthesia, the scores at times a violet and tender heat in the ear. That the songs are made resonant through the body’s triumph is a truth this album makes palpable. As a queer artist, this truth nourishes me, inspires me anew. This is music to both fight and make love to. To be shattered and whole with. If sound is, after all, a negotiation/disruption of time, then in the soft storm of Set My Heart On Fire Immediately, the future is here. Because it was always here. Welcome home.

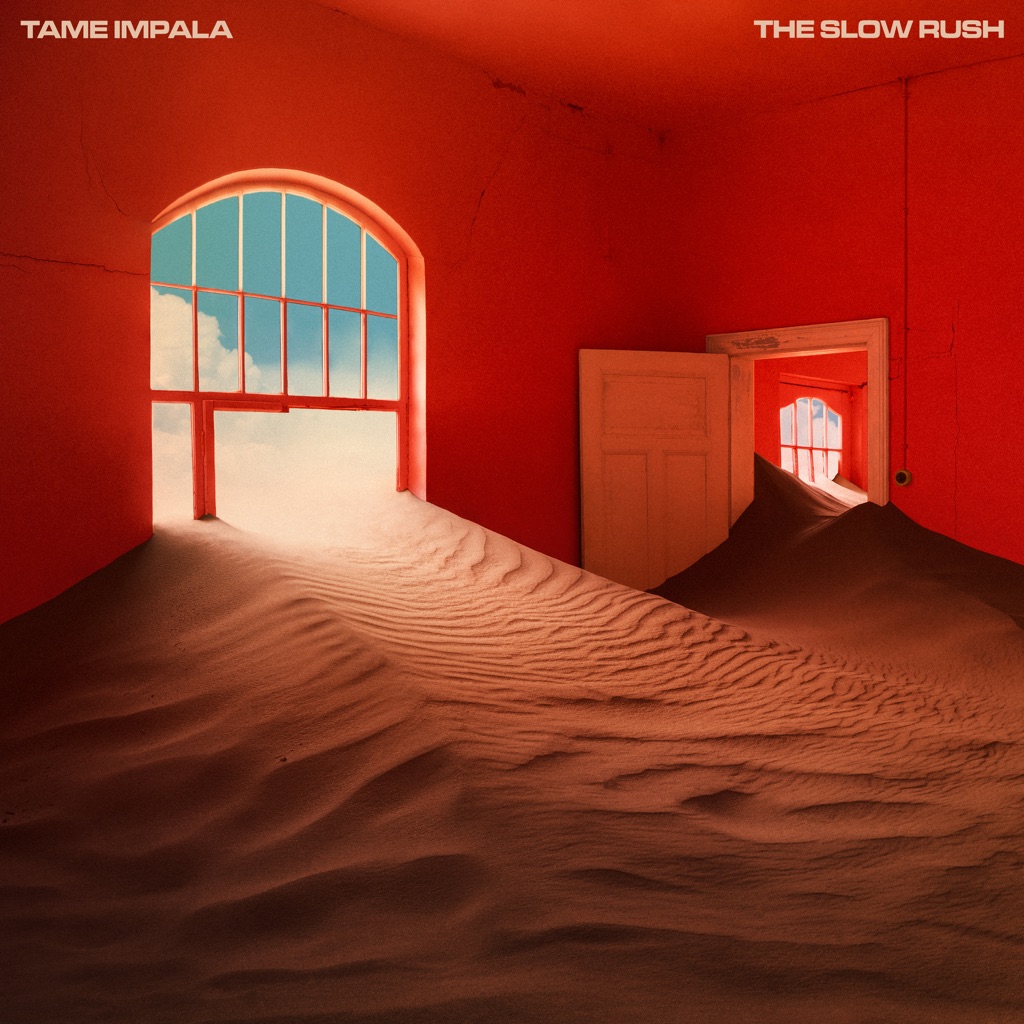

“This feels like \[2017’s\] *Crack-Up*’s friendly brother,” Robin Pecknold tells Apple Music of his fourth LP under the Fleet Foxes name. Written and recorded alongside producer-engineer Beatriz Artola (Adele, J Cole, The Kills) throughout much of 2019 and 2020, *Shore* is an album of gratitude—one that found its lyrical focus in quarantine, as Pecknold began taking day-long drives from his New York apartment up to Lake Minnewaska and into the Catskills and back, stopping only to get gas or jot down ideas as they came to him. “It was like the car was the safest place to be,” he says. “I had this optimistic music but I’d been writing these kind of downer lyrics and it just wasn\'t gelling. It was realizing that in the grand scheme of things, this music is pretty unimportant compared to what\'s going on.” At the album\'s heart is “Sunblind,” an opening statement that pays glimmering tribute to some of Pecknold’s late musical heroes—from Richard Swift to Elliott Smith to David Berman, Curtis Mayfield, Jimi Hendrix, Judee Sill, and more. “I wanted the album to be for these people,” Pecknold says. “I’m trying to celebrate life in a time of death, trying to find something to hold on to that exists outside of time, something that feels solid or stable.” Here, Pecknold walks us through every song on the album. **Wading in Waist-High Water** “I would have a piece of music and then I would try and sing it, but I would always try and pitch my voice up an octave or manipulate my voice to make it match the calming, mourning tone of the music a little more. And then a friend of mine sent me a clip of Uwade Akhere covering \[2008’s\] ‘Mykonos’ on Instagram, and I was just in love with the texture of her voice and just how easy it was. That was a signal that this was going to be a different kind of album in some ways. It was like I finally found a song where I was like, ‘You know what? This is just going to be more of what I want it to be if someone else sings it.’ And that\'s been an awesome mindset to be in lately, just thinking more about writing for other voices and what other voices can naturally evoke without just trying to make my voice do a ton of different things to get to an emotional resonance.” **Sunblind** “I knew I wanted it to be kind of a mission statement for the record—kind of cite-your-sources energy a little bit. And then find a way to get from this list of names of dead musicians that I\'m inspired by—whose music has really helped me in my life—to somewhere that felt like you were taking the wheel and doing something with that feeling. Or trying to live in honor of that, at least in a way that they\'re no longer able to, or in a way that carries their point of view forward into the future. ‘Sunblind’ is like giving the record permission to go all these places or something. Once it felt like it was doing that, then the whole record kind of made more sense to me, or felt like it all tied into each other in a way that it hadn\'t when that song wasn\'t done.” **Can I Believe You** “That riff is the oldest thing on the album, because I wrote that in the middle of the *Crack-Up* tour and tried working on it then but never got anywhere with it really. Once I was thinking less about some second party that\'s untrustworthy and more just one person\'s own hang-ups with letting people in—like my own hang-ups with that—then the lyrics flowed a little better. Those choral voices are actually 400 or 500 people from Instagram that sent clips of them singing that line to me. And then we spent days editing them together and cleaning them up. There\'s this big hug of vocals around the lead vocal that’s talking about trust or believability.” **Jara** “I wanted ‘Can I Believe You’ to be kind of a higher-energy headbanger-type song, and then after that, have a more steady groove—a loop-based, almost builder-type song. That\'s the single-friend kind of placement on the record. Jara is a reference to Victor Jara, the Chilean folk singer. A national hero there who was killed by Pinochet’s army. But it\'s not about Victor Jara— it\'s more like with ‘Sunblind,’ where you\'re trying to eulogize someone, to honor someone or place them in some kind of canon.” **Featherweight** “It\'s the first minor-key song, but it\'s also the first one that\'s without a super prominent drumbeat. It’s lighter on its feet. I thought it was following a train of thought—where with ‘Jara’ there is a bit of envy of a political engagement, in ‘Featherweight,’ I feel like it\'s kind of examining privilege a little bit more. This period of time accommodated that in a very real way for me, just making my problems seem smaller. Acknowledging that I\'ve made problems for myself sometimes in my life when there weren\'t really any.” **A Long Way Past the Past** “Everything I tried was either too Michael McDonald or too Sly Stone or too Stevie Wonder. At that tempo it was just hard to find the instrumentation that didn\'t feel too pastiche or something. While I was writing the lyrics to it, I was thinking, ‘How much am I living in the past? How much can I leave that behind? How much of my identity is wrapped up in memories?’ And asking for help from a friend to maybe fend through that or come on the other side of that. So I thought it was funny to have that be the lyric on the most maybe nostalgic piece of music on the record in terms of what it\'s referencing.” **For a Week or Two** “The first couple Fleet Foxes records, it was a rural vibe as opposed to an urban vibe. I think on the first album, that was just the music I liked, but it wasn\'t like the lyrics were talking about a bunch of personal experiences I had in nature, because I was just 20 years old making that album and I didn\'t have a lot to draw from. ‘For a Week or Two,’ that\'s really about a bunch of long backpacking trips that I was taking for a while. And just the feeling that you have when you\'re doing that, of not being anyone and just being this body in space and never catching your reflection in anything. Carrying very little, and finding some peace in that.” **Maestranza** “Musically, I think for a while it had something in it that had a disco or roller-skating kind of energy that I was trying to find a way out of, and then we found this other palette of instruments that felt less that way. I was trying to go for a Bill Withers-y thing. I feel like a lot of the people that get mentioned in ‘Sunblind,’ their resonance is there, influencing throughout the record. In the third verse, it’s about missing your friends, missing your people, but knowing that since we\'re all going through the same thing that we\'re kind of connected through that in a way that\'s really special and kind of unique to this period. I feel more distant from people but also closer in terms of my actual daily experience.” **Young Man’s Game** “I thought it would be funny if Hamilton \[Leithauser\]’s kids were on it. My original idea was to have it sung by a 10-year-old boy, and then that was just too gimmicky or something. But I wanted there to be kids on it because it\'s referencing immaturity or naivete—things about being young. Because people say ’a young man’s game’ in kind of a positive way. Sometimes they\'re sad they aged out or something. But in this song I use it more in the negative sense of ‘glad you\'ve moved on from some of these immature delusions’ or something. When I was younger I would be much too insecure to make a goofy song, needing everything to be perfect or dramatic or whatever mindset I was in.” **I’m Not My Season** “A friend of mine had been telling me about her experience helping a family member with addiction. As she was describing that, I was imagining this sailing lesson I had taken where we were learning how to rescue someone who had fallen overboard and you have to circle the boat around the right way and throw the ropes from the right place. Time is just something that\'s happening around us, but there\'s some kind of core idea that you\'re not what\'s happening to you. Like wind on a flag.” **Quiet Air / Gioia** “The chords had this kind of expectant feel or something, like an ominous quality, that\'s never really resolving. And I think that kind of led me to want to write about imagining someone, speaking to somebody who is courting danger. Some of the lyrics in the song come from talking to a friend of mine who is a climate scientist, and just her perspective on how screwed we are or aren’t. Just thinking about that whole issue hinges on particulate matter in air that is invisible. You can just be looking at the sky and looking at what will eventually turn into an enormous calamity, and it\'s quietly occurring, quietly accruing. It\'s happening on a time scale that we\'re not prepared to accept or deal with. The ending is this more ecstatic thing. Just imagining some weird pagan dance, like rite of spring or something, where it just kind of builds into this weird kind of joy. Like dancing while the world burns.” **Going-to-the-Sun Road** “The Sun Road is a place in Montana, a 60-mile stretch of road that’s only open for a couple months every year. It’s where they filmed the intro to *The Shining*, where they\'re driving to the lodge and it’s just very scenic. I grew up fairly close to there. A lot of the studios that I worked at on this record were places that I had always wanted to go and work, places where I’ve been like, ‘Oh, one day I\'ll make a record there.’ That song is about being tired of traveling, wanting to slow down a bit and wanting to not fight so hard personally against yourself. Or trying to have as many adventures as possible, but then having this one place—almost like a Rosebud kind of thing—where it\'s like going to the Sun Road is the last big adventure. The one that\'s always on the horizon that you have to look forward to that keeps you going.” **Thymia** “Getting back to work on the record \[after the pandemic hit\] was so rewarding. And I feel like if there was a relationship being discussed on the record, it\'s between me and my love affair with music. ‘Thymia’ I think means ‘boisterous spirit’ or something. The image and the lyrics to that song in my head were kind of me driving around with some camping gear in my back seat that\'s clanging out a rhythm of some kind. And that feeling of, even if I\'m driving alone, there\'s something. That sound is pulling me to the thought of music. It\'s kind of accompanying me. I\'ve known it for a long time. Even though it\'s ephemeral, it\'s the most solid thing that I have.” **Cradling Mother, Cradling Woman** “I wanted to use the sample of Brian Wilson because that clip meant a lot to me growing up, him layering vocals on ‘Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder).’ That song has the most stuff I\'ve ever put on a song, and it\'s the most overdubby—very much in that lineage of just layer after layer after layer. Emotionally, it’s similar to that idea of, like, ‘My clothes are torn but the air is clean.’ That feeling like it can be okay to be a little ragged and you can still feel good, like being exhausted at the end of a long run or something. That image of the maternal and feminine would again be a reference to music. Like my receiver, cradling me again. Kind of like being subsumed by music and comforted and consoled by it.” **Shore** “‘Cradling Mother’ could be the climax maybe, and ‘Shore’ felt like an epilogue. In the same way that ‘Wading in Waist-High Water’ is a prologue. Lyrically, it\'s tying up some loose ends, talking to the kin that you rely on—your family or your heroes—and thanking them. It references the shore as this stable place and questions whether you\'re really at the boundary between danger and safety when you\'re there. I\'d actually had a surfing accident where I snapped my leash and I really felt like I was going to drown. It took me 15 minutes to swim to shore and I kept getting pummeled by waves. I was so happy to make it back. I\'ve been pretty afraid since then to do that much surfing in bad conditions. But to me, that image was this comforting thing that then kind of dissolves. The vocals break apart and then it\'s like you\'re getting back in the water and you\'re catching one sound and your voices are blending together and falling apart. You\'re subsumed by water, and then the seas calm, but you\'re floating into the future.”

Today, on the Autumnal Equinox, Fleet Foxes released their fourth studio album Shore at 6:31 am PT/9:31 am ET. The bright and hopeful album, released via Anti-. Shore was recorded before and during quarantine in Hudson (NY), Paris, Los Angeles, Long Island City and New York City from September 2018 until September 2020 with the help of recording and production engineer Beatriz Artola.The fifteen song, fifty-five minute Shore was initially inspired by frontman Robin Pecknold’s musical heroes such as Arthur Russell, Nina Simone, Sam Cooke, Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guebrou and more who, in his experience, celebrated life in the face of death. “I see “shore” as a place of safety on the edge of something uncertain, staring at Whitman’s waves reciting ‘death,’” commented Pecknold. “Tempted by the adventure of the unknown at the same time you are relishing the comfort of the stable ground beneath you. This was the mindset I found, the fuel I found, for making this album.” Pecknold continues: Since the unexpected success of the first Fleet Foxes album over a decade ago, I have spent more time than I’m happy to admit in a state of constant worry and anxiety. Worried about what I should make, how it will be received, worried about the moves of other artists, my place amongst them, worried about my singing voice and mental health on long tours. I’ve never let myself enjoy this process as much as I could, or as much as I should. I’ve been so lucky in so many ways in my life, so lucky to be born with the seeds of the talents I have cultivated and lucky to have had so many unreal experiences. Maybe with luck can come guilt sometimes. I know I’ve welcomed hardship wherever I could find it, real or imagined, as a way of subconsciously tempering all this unreal luck I’ve had. By February 2020, I was again consumed with worry and anxiety over this album and how I would finish it. But since March, with a pandemic spiraling out of control, living in a failed state, watching and participating in a rash of protests and marches against systemic injustice, most of my anxiety around the album disappeared. It just came to seem so small in comparison to what we were all experiencing together. In its place came a gratitude, a joy at having the time and resources to devote to making sound, and a different perspective on how important or not this music was in the grand scheme of things. Music is both the most inessential and the most essential thing. We don’t need music to live, but I couldn’t imagine life without it. It became a great gift to no longer carry any worry or anxiety around the album, in light of everything that is going on. A tour may not happen for a year, music careers may not be what they once were. So it may be, but music remains essential. This reframing was another stroke of unexpected luck I have been the undeserving recipient of. I was able to take the wheel completely and see the album through much better than I had imagined it, with help from so many incredible collaborators, safe and lucky in a new frame of mind.