***** 'a profound talent’ The Guardian **** ‘an immersive debut’ The Observer 8/10 ‘stunningly confident, in full possession of its art’ Uncut ‘raw, virtuosic’ Mojo Debut full length album, featuring the tracks: 01: Off to See the Hangman, Pt. I 02: Sometimes There's Blood 03: Idumea 04: Off to See the Hangman, Pt. II 05: Face Down Strut 06: Laika's Song 07: Oh, Command Me Lord ! 08: Sweep It Up 09: Requiem for John Fahey 10: Dance of the Everlasting Faint 11: Bleeding Finger Blues 12: Sack 'em Up, Pt. I / Sack 'em Up, Pt. II 13: It Was All Sackcloth and Ashes

A warm, convivial album that ranges from peppy swing (“Don’t Tell Noah”) to sobering ballads (“Something You Get Through”), *Last Man Standing*—like 2017’s *God’s Problem Child*—finds Willie Nelson, a few ticks into his eighties, tackling mortality with grace and wit. He reckons with the fact that he’ll one day go, while laughing—in great, gleeful appreciation—that he hasn’t seen that day yet. “‘Halitosis’ is a word I never could spell,” he cracks on “Bad Breath.” “But bad breath is better than no breath at all.” May we all age so well.

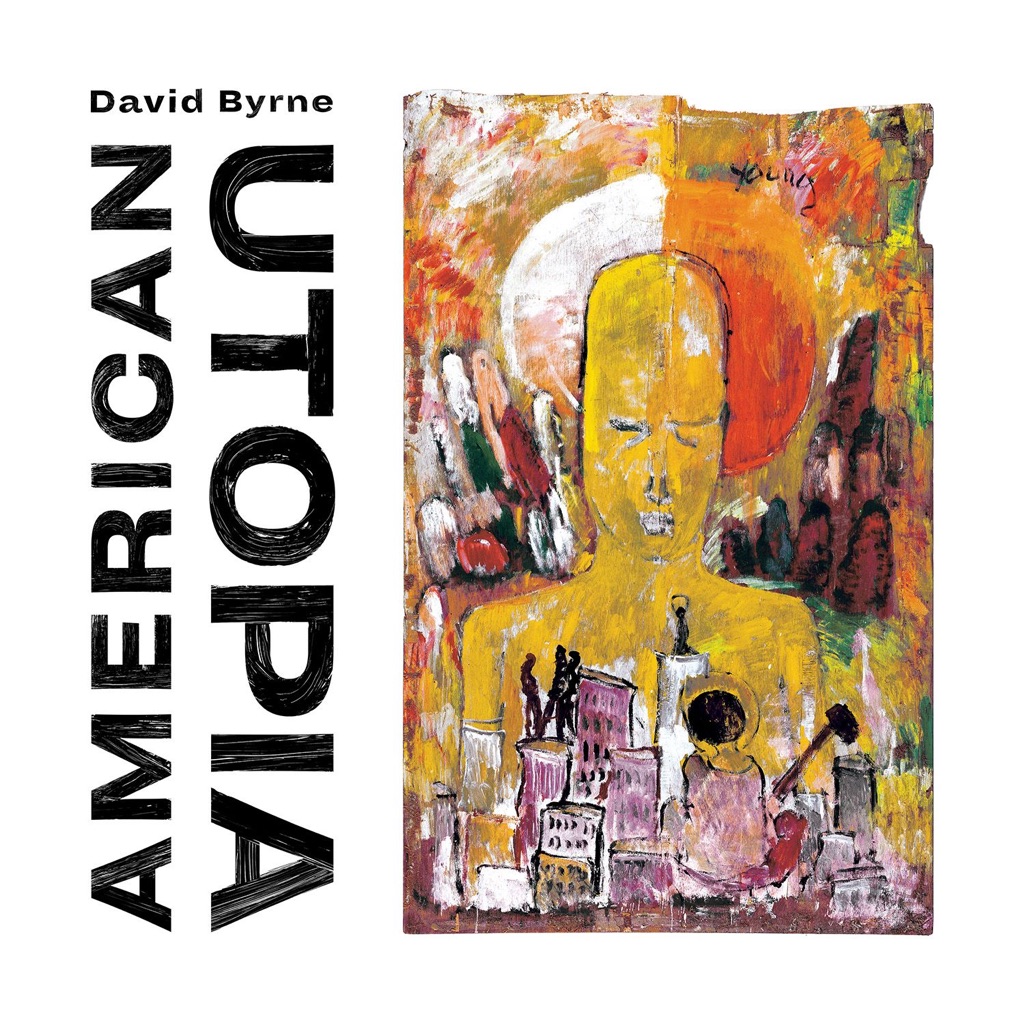

This record—Byrne’s first as a solo artist in 14 years—offers a timely examination of the American experiment, shot through with purpose and kinetic strangeness. Whether clinging to small pleasures with absurdist observations (“Every Day Is a Miracle”) or contemplating freedom amid harmonica-sprinkled funk (“Gasoline and Dirty Sheets”), the tremulous former Talking Heads leader brings trademark brio and unexpectedness. And as the giddy, percussive earworm “Everybody’s Coming to My House” hits (“We’re only tourists in this life/Only tourists, but the view is nice”), *American Utopia* puts forward a compelling case for optimism in even the darkest times.

The fourth Tune-Yards album bears more electronics and dance beats than its predecessors, but Merrill Garbus\' combination of sociopolitical savvy, outside-the-box creativity, and giddily infectious enthusiasm remains. While the R&B inflections and late-night club vibe of \"Heart Attack\" may represent something of a stylistic shift, the electronic beats of \"Private Life\" are sprinkled with the kind of world-music influences and playground-chant cadences that have been part of Tune-Yards\' tool kit for a while. And the minimalist, dub-like feel of the haunting \"Home\" comes off as organic as anything Garbus has done.

On Cosmic Wink, Jess Williamson’s third album following the self-published Native State and Heart Song, an artist emerges as another self in love, under California’s influence, and a part of an even wider consciousness. Cosmic Wink is a record about how vulnerability can feel something less vulnerable when love - true, deep love - creates a latticework of strength underneath the frame of our humanity.

Meet Me At The River is Landes’ self-described “Nashville record,” and she has assured its pedigree by enlisting the production skills of Fred Foster, the Country Music Hall of Fame member who played a pivotal role in the careers of Dolly Parton, Roy Orbison, and Kris Kristofferson. Two years ago, Landes reached out to Foster, and a four-hour visit to his Nashville home convinced both they were musical kindred spirits. With roots in both Louisville, Kentucky, and Branson, Missouri, Landes has been attracting ardent fans and critical acclaim since entering New York’s music scene in 2000. Along the way, she has collaborated with such contemporaries as Sufjan Stevens, Justin Townes Earle, and Norah Jones, creating music for albums, movies, and television that crosses folk, rock, and alternative genres.

Part string quartet, part radio play, part sound installation, Laurie Anderson and Kronos Quartet’s *Landfall* takes us on a journey through the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, which battered the Caribbean and the mainland United States in October 2012. Anderson is a thoughtful sound artist, blending electronic and acoustic music with voice narration to tell her tale of loss and destruction. Poignant moments include “Thunder Continues in the Aftermath,” a haunting echo of the departing storm with stunning digital effects, and the vivid, spine-tingling “Helicopters Hang Over Downtown.” The simple, narrated “Everything Is Floating” transforms tragedy into unexpected beauty.

Speaking to *The Guardian*, British singer-songwriter-producer Dev Hynes described his fourth LP under the Blood Orange name as “an exploration into my own and many types of black depression, an honest look at the corners of black existence, and the ongoing anxieties of queer/people of color.” Recorded on-the-go in studios around the world (Tokyo, Florence, Copenhagen) with whatever was lying around at the time (“If I go to a studio and they only have an acoustic guitar, then I’ll go with that.”), *Negro Swan* splices Hynes’ impressionistic R&B with recorded conversation and spoken word, the most haunting snippets taken from writer and transgender-rights activist Janet Mock (“Family”) and a surprisingly vulnerable Puff Daddy (“Hope”). The result is dreamy but incisive, melancholic but alive, lonesome but communal. “When you wake up/It’s not the first thing you wanna know,” he sings on “Charcoal Baby,” a highlight. “Can you still count/All the reasons that you’re not alone?”

Producer, multi-instrumentalist, composer, songwriter and vocalist Devonte Hynes returns with his fourth album as Blood Orange, Negro Swan. Raised in England, Hynes started out as a teenage punk in the UK band Test Icicles before releasing two orchestral acoustic pop records as Lightspeed Champion. In 2011, he released Coastal Grooves, the first of three solo albums under the moniker Blood Orange. His last album, Freetown Sound, was released to critical acclaim in 2016, and saw Hynes defined as one of the foremost musical voices of his time, receiving comparisons to the likes of KendrickLamar and D’Angelo for his own searing and soothing personal document of life as a black man in America. He has collaborated with Solange Knowles, FKA Twigs, and many other artists, and was recently one of four artists invited to the Kennedy Center to perform alongside Philip Glass. In addition to his production work, he scored the film Palo Alto, directed by Gia Coppola and starring James Franco. Hynes’ newest album, Negro Swan, was written and produced by Hynes. Says Hynes: "My newest album is an exploration into my own and many types of black depression, an honest look at the corners of black existence, and the ongoing anxieties of queer/people of color. A reach back into childhood and modern traumas, and the things we do to get through it all. The underlying thread through each piece on the album is the idea of HOPE, and the lights we can try to turn on within ourselves with a hopefully positive outcome of helping others out of their darkness."

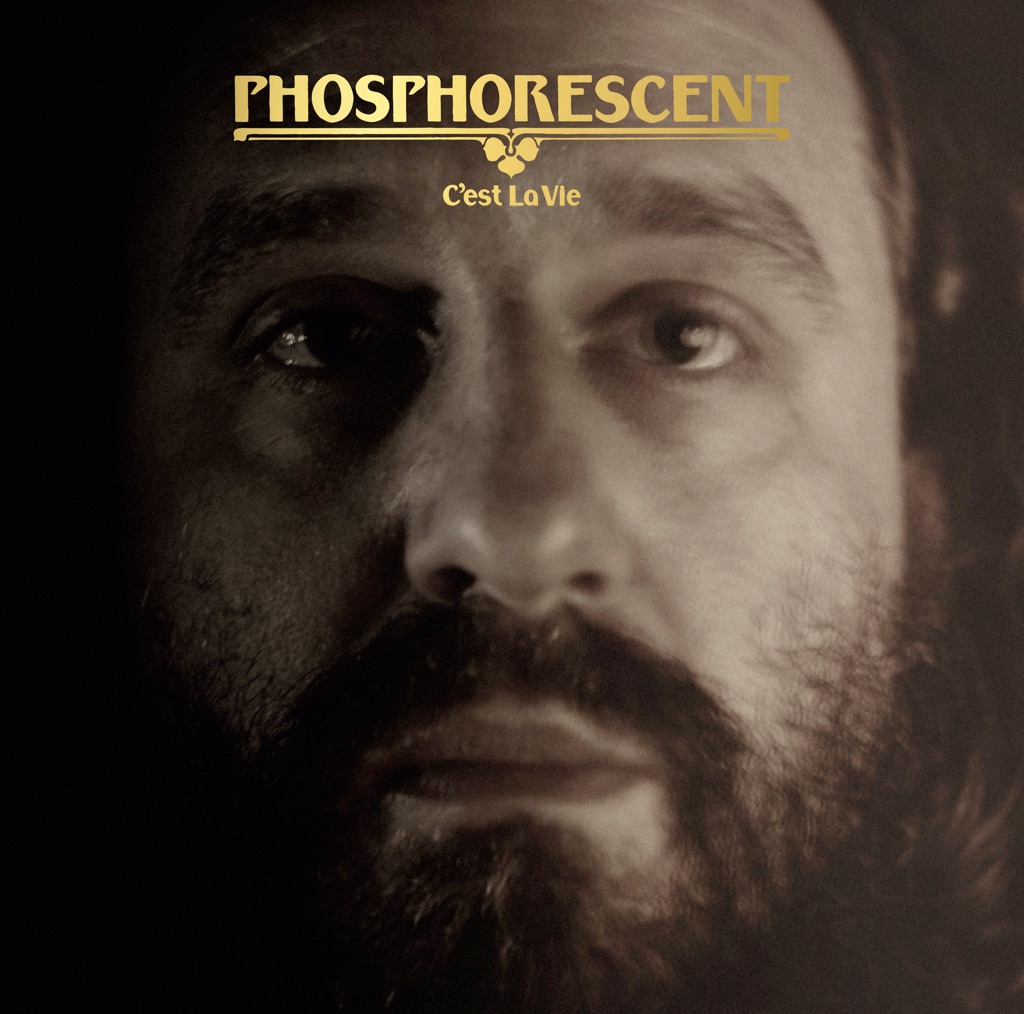

Singer-songwriter Matthew Houck’s seventh studio album opens with a similar desert incantation as 2013’s *Muchacho*, but what he summons differs dramatically from the heartbreak that panged throughout his last album. For starters, parenthood has shifted his perspective, and he explores the experience on the ebullient, country-pop-rock of “New Birth in New England” as well as the meditative, pedal steel-twined “My Beautiful Boy.” But more than those milestones, he revels in his long-fought-for stability. “I stood out in the rain like the rain might come and wash my eyes clean,” he sings on the synth-driven “C’est La Vie No. 2.” Rather than wait for an answer from the heavens, Houck gets on with living, asserting, “I don’t stand out in the rain to have my eyes washed clean no more.”

In the five years since Matthew Houck’s last record as Phosphorescent he fell in love, left New York for Nashville, became a father, built a studio from the ground up by hand, and became a father again. Oh, and somewhere along the way, he nearly died of meningitis. Life, love, new beginnings, death— “it’s laughable, honestly, the amount of ‘major life events’ we could chalk up if we were keeping score,” Houck says. “A lot can happen in five years.” On C’est La Vie, Houck’s first album of new Phosphorescent material since 2013’s gorgeous career defining and critically acclaimed Muchacho, he takes stock of these changes through the luminous, star-kissed sounds he has spent a career refining. By now, Houck has mastered the contours of this place, as intimate as it is grand, somewhere between dreamed and real, where the great lyrical songwriters meet experimental pioneers and somehow distill into the same person. It is Houck’s own personal musical cosmos, a mixture of the earthy and the wondrous, the troubled and the serene, and by now he commands it with depth and precision. When you ask Houck about the cumulative effect of all this life happening in such a short time, he turns philosophical: ”These significant moments in life can really make you feel your insignificance,” he says. "It's a paradox I guess, that these wildly profound events simultaneously highlight that maybe none of this matters at all..." On this album, Houck reckons with that void — the vanishing point where our individual significance melts into the stars — and sums it up thusly: C'est La Vie. From the album’s opening moments, Houck sings of this newfound landscape. Of the discovery of new paradigms and the disposal of those no longer useful. After the wordless, haunting Houck-choir opener of “Black Moon / Silver Waves”, he pointedly begins the title track “C’est La Vie No. 2” with the albums first lyrics: “I wrote all night / Like the fire of my words could burn a hole up to heaven / I don’t write all night burnin’ holes up to heaven no more.” "I was always pursuing this thing of Phosphorescent and becoming the artist that I wanted to become, that sometimes I didn’t even have a second for reflection,” Houck says of the hectic years spent creating, releasing and touring Muchacho. "I was plowing forward—just do, do, do and all else was secondary.” Not that this album exhibits any sense of settling down into complacency. On the contrary, this collection contains some of Houck’s most devastating works to date, but there’s a refreshing measured confidence that radiates throughout C’est La Vie. Sonically, C’est La Vie is his masterwork: Every sound, including his famously frayed, bemused voice, rings out as inviting and clear as a koi pond. Working in a studio he built from scratch (which certainly came with its own set of challenges) Houck once again set off to produce his own record, calling in musicians from his crack live band as well as friends new and old, and enlisting veteran Vance Powell to help mix the completed project. The writing process was more intuitive, less cerebral and with fewer revisions than anything he'd written before. It was a scary, liberating new approach, like painting with his eyes closed. "I let go of a lot of my writer-poet tricks, and let the lyrics be what they wanted to be,” he says. These lyrics marvel at life’s ability to uproot and re-deposit you into alien, revelatory landscapes: “If you’d have seen me last year, I’d have said, ‘I can’t even see you there from here.’” he sings, wryly, on “There From Here.” This has been one of Phosphorescent’s constant themes—the ever-present possibility for transformation. But for the first time, Houck seems to be laying down some burdens. “These rocks, they are heavy/I’ve been carrying them around all my days,” he sighs on the album’s closing ballad “These Rocks.” On that same song he also muses, with disarming forthrightness, about drinking: “I stayed drunk for a decade/I’ve been thinking of putting that stuff away.” The lyric makes Houck somewhat uncomfortable, both in its direct simplicity and its capacity to distract listeners into thinking he’d written a stereotypical “battle with the bottle” song. “I'm aware of how that verse resonates, but for me those lines take a backseat to the main driver of that song,” he says. “I originally assumed I'd rewrite and re-sing that lyric,” he says. "But the bones of that song were recorded live and it was the first time I ever played it. It was the first time the band ever heard it and I think it captured something perfect. And it was, y'know, true." So I had to ask myself, again, ‘Well, what is the point of what I’m doing here? I could re-record it but why not just let it be?” To hear Houck, he confronts this moment of mystery every time he records. “Oh yeah, this process is positively filled with moments where you go ‘What exactly the hell is it that I'm doing here?’” Houck laughs. “And the answer always comes back a resounding, ‘I don’t know.’” Ain't that just how it goes, C’est La Vie

Richard Swift believed in and sought real beauty. And so, even at its most caustic and sardonic, his masterpiece swan song The Hex is beautiful. Conceived in pieces over the last several years and completed just the month before his passing, The Hex is the grand statement Swift acolytes have been a-wishin-and-a-hopin' for all these years. After a career of sticking some of his finest songs on EPs and 45s, here are all his powers coalescing into a single, long-player statement. At its core, The Hex is an aching call out into the void for Swift’s mother (“Wendy”) and his sister (“Sister Song”) whom he lost in back-to-back years. You hear a man at his lowest and spiritually on his heels. The pain fueling Swift’s cries of “She’s never comin’ back” on the absolutely gutting standout “Nancy” is some sort of dark catharsis for anyone who’s ever lost a loved one to the cold abstraction of Death. Over a slow, Wall of Sound kick and a warbling synth, Swift’s cries climb higher-n-higher-n-higher into what may be his most devastating vocal performance on record. A cry of pain so real and so raw Swift had to treat the performance with just a little studio effect, without which the recorded grieving might be too much to bear. The Hex is presented here as “The Hex For Family and Friends.” An obsessive fan of Wall of Sound doo-wop, early Funkadelic, Bo Diddley, Beefheart and Link Wray, Swift gives them all a moment with the flashlight around The Hex campfire, one moment to make a strange shadow-cast face for us, his family and friends.

Building on his background as a classical pianist and composer, British producer Jon Hopkins uses vast electronic soundscapes to explore other worlds. Here, on his fifth album, he contemplates our own. Inspired by adventures with meditation and psychedelics, *Singularity* aims to evoke the magical awe of heightened consciousness. It’s a theme that could easily feel affected or clichéd, but Hopkins does it phenomenal justice with imaginative, mind-bending songs that feel both spontaneous and rigorously structured. Floating from industrial, polyrhythmic techno (“Emerald Rush\") to celestial, ambient atmospheres (“Feel First Life”), it’s a transcendent headphone vision quest you’ll want to go on again.

Please note: Digital files are 16bit. Singularity marks the fifth album from the UK electronic producer and composer and the follow up to 2013’s Mercury Prize nominated Immunity. Where Immunity charted the dark alternative reality of an epic night out, Singularity explores the dissonance between dystopian urbanity and the green forest. It is a journey that returns to where it began – from the opening note of foreboding to the final sound of acceptance. Shaped by his experiences with meditation and trance states, the album flows seamlessly from rugged techno to transcendent choral music, from solo acoustic piano to psychedelic ambient.

*“Excited for you to sit back and experience *Golden Hour* in a whole new, sonically revolutionized way,” Kacey Musgraves tells Apple Music. “You’re going to hear how I wanted you to hear it in my head. Every layer. Every nuance. Surrounding you.”* Since emerging in 2013 as a slyly progressive lyricist, Kacey Musgraves has slipped radical ideas into traditional arrangements palatable enough for Nashville\'s old guard and prudently changed country music\'s narrative. On *Golden Hour*, she continues to broaden the genre\'s horizons by deftly incorporating unfamiliar sounds—Bee Gees-inspired disco flourish (“High Horse”), pulsating drums, and synth-pop shimmer (“Velvet Elvis”)—into songs that could still shine on country radio. Those details are taken to a whole new level in Spatial Audio with Dolby Atmos. Most endearing, perhaps, is “Oh, What a World,” her free-spirited ode to the magic of humankind that was written in the glow of an acid trip. It’s all so graceful and low-key that even the toughest country purists will find themselves swaying along.

Swapping producer Chris Coady for Spaceman 3\'s Pete \"Sonic Boom\" Kember, Alex Scally and Victoria Legrand fully embrace their bliss on *7*, their haziest, dreamiest album yet. They move seamlessly from meditative to trippy, adopting swelling, stately, Spector-swilling-martinis-with-Eno arrangements on \"Last Ride\" and entering a reverb-drenched citadel of synths on \"L\'Inconnue.” Seeming more unabashedly themselves than ever, this is the sound of Beach House doubling down on the aqueous dream-pop perfection that made them indie heroes in the first place.

7 is our 7th full-length record. At its release, we will have been a band for over 13 years. We have now written and released a total of 77 songs together. Last year, we released an album of b-sides and rarities. It felt like a good step for us. It helped us clean the creative closet, put the past to bed, and start anew. Throughout the process of recording 7, our goal was rebirth and rejuvenation. We wanted to rethink old methods and shed some self-imposed limitations. In the past, we often limited our writing to parts that we could perform live. On 7, we decided to follow whatever came naturally. As a result, there are some songs with no guitar, and some without keyboard. There are songs with layers and production that we could never recreate live, and that is exciting to us. Basically, we let our creative moods, instead of instrumentation, dictate the album’s feel. In the past, the economics of recording have dictated that we write for a year, go to the studio, and record the entire record as quickly as possible. We have always hated this because by the time the recording happens, a certain excitement about older songs has often been lost. This time, we built a "home" studio, and began all of the songs there. Whenever we had a group of 3-4 songs that we were excited about, we would go to a “proper” recording studio and finish recording them there. This way, the amount of time between the original idea and the finished song was pretty short (of the album’s 11 songs, 8 were finished at Carriage House in Stamford, CT and 2 at Palmetto Studio in Los Angeles). 7 didn’t have a producer in the traditional sense. We much preferred this, as it felt like the ideas drove the creativity, not any one person’s process. James Barone, who became our live drummer in 2016, played on the entire record. His tastes and the trust we have in him really helped us keep rhythm at the center of a lot of these songs. We also worked with Sonic Boom (Peter Kember). Peter became a great force on this record, in the shedding of conventions and in helping to keep the songs alive, fresh and protected from the destructive forces of recording studio over-production/over-perfection. The societal insanity of 2016-17 was also deeply influential, as it must be for most artists these days. Looking back, there is quite a bit of chaos happening in these songs, and a pervasive dark field that we had little control over. The discussions surrounding women’s issues were a constant source of inspiration and questioning. The energy, lyrics and moods of much of this record grew from ruminations on the roles, pressures and conditions that our society places on women, past and present. The twisted double edge of glamour, with its perils and perfect moments, was an endless source (see “L’Inconnue,” “Drunk in LA,” “Woo,” “Girl Of The Year,” “Last Ride”). In a more general sense, we are interested by the human mind's (and nature’s) tendency to create forces equal and opposite to those present. Thematically, this record often deals with the beauty that arises in dealing with darkness; the empathy and love that grows from collective trauma; the place one reaches when they accept rather than deny (see “Dark Spring,” “Pay No Mind,” “Lemon Glow,” “Dive,” “Black Car,” “Lose Your Smile”). The title, 7, itself is simply a number that represents our seventh record. We hoped its simplicity would encourage people to look inside. No title using words that we could find felt like an appropriate summation of the album. The number 7 does represent some interesting connections in numerology. 1 and 7 have always shared a common look, so 7 feels like the perfect step in the sequence to act as a restart or “semi-first.” Most early religions also had a fascination with 7 as being the highest level of spirituality, as in "Seventh Heaven.” At our best creative moments, we felt we were channeling some kind of heavy truth, and we sincerely hope the listeners will feel that. Much Love, Beach House