The Vinyl Factory's 50 Favourite Albums of 2021

Vinyl Factory's favourite albums of 2020 – the fifty records that the editorial team loved during the past 12 months.

Published: December 09, 2021 18:48

Source

The jazz great Pharoah Sanders was sitting in a car in 2015 when by chance he heard Floating Points’ *Elaenia*, a bewitching set of flickering synthesizer etudes. Sanders, born in 1940, declared that he would like to meet the album’s creator, aka the British electronic musician Sam Shepherd, 46 years his junior. *Promises*, the fruit of their eventual collaboration, represents a quietly gripping meeting of the two minds. Composed by Shepherd and performed upon a dozen keyboard instruments, plus the strings of the London Symphony Orchestra, *Promises* is nevertheless primarily a showcase for Sanders’ horn. In the ’60s, Sanders could blow as fiercely as any of his avant-garde brethren, but *Promises* catches him in a tender, lyrical mode. The mood is wistful and elegiac; early on, there’s a fleeting nod to “People Make the World Go Round,” a doleful 1971 song by The Stylistics, and throughout, Sanders’ playing has more in keeping with the expressiveness of R&B than the mountain-scaling acrobatics of free jazz. His tone is transcendent; his quietest moments have a gently raspy quality that bristles with harmonics. Billed as “a continuous piece of music in nine movements,” *Promises* takes the form of one long extended fantasia. Toward the middle, it swells to an ecstatic climax that’s reminiscent of Alice Coltrane’s spiritual-jazz epics, but for the most part, it is minimalist in form and measured in tone; Shepherd restrains himself to a searching seven-note phrase that repeats as naturally as deep breathing for almost the full 46-minute expanse of the piece. For long stretches you could be forgiven for forgetting that this is a Floating Points project at all; there’s very little that’s overtly electronic about it, save for the occasional curlicue of analog synth. Ultimately, the music’s abiding stillness leads to a profound atmosphere of spiritual questing—one that makes the final coda, following more than a minute of silence at the end, feel all the more rewarding.

“Sometimes I’ll be in my own space, my own company, and that’s when I\'m really content,” Little Simz tells Apple Music. “It\'s all love, though. There’s nothing against anyone else; that\'s just how I am. I like doing my own thing and making my art.” The lockdowns of 2020, then, proved fruitful for the North London MC, singer, and actor. She wrestled writer’s block, revived her cult *Drop* EP series (explore the razor-sharp and diaristic *Drop 6* immediately), and laid grand plans for her fourth studio album. Songwriter/producer Inflo, co-architect of Simz’s 2019 Mercury-nominated, Ivor Novello Award-winning *GREY Area*, was tapped and the hard work began. “It was straight boot camp,” she says of the *Sometimes I Might Be Introvert* sessions in London and Los Angeles. “We got things done pronto, especially with the pace that me and Flo move at. We’re quite impulsive: When we\'re ready to go, it’s time to go.” Months of final touches followed—and a collision between rap and TV royalty. An interest in *The Crown* led Simz to approach Emma Corrin (who gave an award-winning portrayal of Princess Diana in the drama). She uses her Diana accent to offer breathless, regal addresses that punctuate the 19-track album. “It was a reach,” Simz says of inviting Corrin’s participation. “I’m not sure what I expected, but I enjoyed watching her performance, and wrote most of her words whilst I was watching her.” Corrin’s speeches add to the record’s sense of grandeur. It pairs turbocharged UK rap with Simz at her most vulnerable and ambitious. There are meditations on coming of age in the spotlight (“Standing Ovation”), a reunion with fellow Sault collaborator Cleo Sol on the glorious “Woman,” and, in “Point and Kill,” a cleansing, polyrhythmic jam session with Nigerian artist Obongjayar that confirms the record’s dazzling sonic palette. Here, Simz talks us through *Sometimes I Might Be Introvert*, track by track. **“Introvert”** “This was always going to intro the album from the moment it was made. It feels like a battle cry, a rebirth. And with the title, you wouldn\'t expect this to sound so huge. But I’m finding the power within my introversion to breathe new meaning into the word.” **“Woman” (feat. Cleo Sol)** “This was made to uplift and celebrate women. To my peers, my family, my friends, close women in my life, as well as women all over the world: I want them to know I’ve got their back. Linking up with Cleo is always fun; we have such great musical chemistry, and I can’t imagine anyone else bringing what she did to the song. Her voice is beautiful, but I think it\'s her spirit and her intention that comes through when she sings.” **“Two Worlds Apart”** “Firstly, I love this sample; it’s ‘The Agony and the Ecstasy’ by Smokey Robinson, and Flo’s chopped it up really cool. This is my moment to flex. You had the opener, followed by a nice, smoother vibe, but this is like, ‘Hey, you’re listening to a *rap* album.’” **“I Love You, I Hate You”** “This wasn’t the easiest song for me to write, but I\'m super proud that I did. It’s an opportunity for me to lay bare my feelings on how that \[family\] situation affected me, growing up. And where I\'m at now—at peace with it and moving on.” **“Little Q, Pt. 1 (Interlude)”** “Little Q is my cousin, Qudus, on my dad\'s side. We grew up together, but then there was a stage where we didn\'t really talk for some years. No bad blood, just doing different things, so when we reconnected, we had a real heart-to-heart—and I heard about all he’d been through. It made me feel like, ‘Damn, this is a blood relative, and he almost lost his life.’ I thank God he didn’t, but I thought of others like him. And I felt it was important that his story was heard and shared. So, I’m speaking from his perspective.” **“Little Q, Pt. 2”** “I grew up in North London and \[Little Q\] was raised in South, and as much as we both grew up in endz, his experience was obviously different to mine. Being a product of an environment or system that isn\'t really for you, it’s tough trying to navigate that.” **“Gems (Interlude)”** “This is another turning point, reminding myself to take time: ‘Breathe…you\'re human. Give what you can give, but don\'t burn out for anyone. Put yourself first.’ Just little gems that everyone needs to hear once in a while.” **“Speed”** “This track sends another reminder: ‘This game is a marathon, not a sprint. So pace yourself!’ I know where I\'m headed, and I\'m taking my time, with little breaks here and there. Now I know when to really hit the gas and also when to come off a bit.” **“Standing Ovation”** “I take some time to reflect here, like, ‘Wow, you\'re still here and still going. It’s been a slow burn, but you can afford to give yourself a pat on the back.’ But as well as being in the limelight, let\'s also acknowledge the people on the ground doing real amazing work: our key workers, our healers, teachers, cleaners. If you go to a toilet and it\'s dirty, people go in from 9 to 5 and make sure that shit is spotless for you, so let\'s also say thank you.” **“I See You”** “This is a really beautiful and poetic song on love. Sometimes as artists we tend to draw from traumatic times for great art, we’re hurt or in pain, but it was nice for me to be able to draw from a place of real joy in my life for this song. Even where it sits \[on the album\]: right in the center, the heart.” **“The Rapper That Came to Tea (Interlude)”** “This title is a play on \[Judith Kerr’s\] children\'s book *The Tiger Who Came to Tea*, and this is about me better understanding my introversion. I’m just posing questions to myself—I might not necessarily have answers for them, I think it\'s good to throw them out there and get the brain working a bit.” **“Rollin Stone”** “This cut reminds me somewhat of ’09 Simz, spitting with rapidness and being witty. And I’m also finding new ways to use my voice on the second half here, letting my evil twin have her time.” **“Protect My Energy”** “This is one of the songs I\'m really looking forward to performing live. It’s a stepper, and it got me really wanting to sing, to be honest. I very much enjoy being around good company, but these days I enjoy my personal space and I want to protect that.” **“Never Make Promises (Interlude)”** “This one is self-explanatory—nothing is promised at all. It’s a short intermission to lead to the next one, but at one point it was nearly the album intro.” **“Point and Kill” (feat. Obongjayar)** “This is a big vibe! It feels very much like Nigeria to me, and Obongjayar is one of my favorites at the moment. We recorded this in my living room on a whim—and I\'m very, very grateful that he graced this song. The title comes from a phrase used in Nigeria to pick out fish at the market, or a store. You point, they kill. But also metaphorically, whatever I want, I\'m going to get in the same way, essentially.” **“Fear No Man”** “This track continues the same vibe, even more so. It declares: ‘I\'m here. I\'m unapologetically me and I fear no one here. I\'m not shook of anyone in this rap game.’” **“The Garden (Interlude)”** “This track is just amazing musically. It’s about nurturing the seeds you plant. Nurture those relationships, and everything around you that\'s holding you down.” **“How Did You Get Here”** “I want everyone to know *how* I got here; from the jump, school days, to my rap group, Space Age. We were just figuring it out, being persistent. I cried whilst recording this song; it all hit me, like, ‘I\'m actually recording my fourth album.’ Sometimes I sit and I wonder if this is all really true.” **“Miss Understood”** “This is the perfect closer. I could have ended on the last track, easily, but, I don\'t know, it\'s kind of like doing 99 reps. You\'ve done 99, that\'s amazing, but you can do one more to just make it 100, you can. And for me it was like, ‘I\'m going to get this one in there.’”

Madvillain superfans will no doubt recall the Four Tet 2005 remix EP stuffed with inventive versions of cuts from the now-certified classic rap album *Madvillainy*. Coming a decade and a half later, *Sound Ancestors* sees Kieran Hebden link once again with iconic hip-hop producer Madlib, this time for a set of all-new material, the product of a years-long and largely remote collaboration process. With source material arranged, edited, and recontextualized by the UK-born artist, the album represents a truly unique shared vision, exemplified by the reggae-tinged boom-bap of “Theme De Crabtree” and the neo-soul-infused clatter of “Dirtknock.” Such genre blends turn these 16 tracks into an excitingly twisty journey through both men’s seemingly boundless creativity, leading to the lithe jazz-hop of “Road of the Lonely Ones” and the rugged B-boy business of “Riddim Chant.”

“I like the simple stuff,” murmurs Loraine James on “Simple Stuff,” a standout track on the London producer’s second album for Hyperdub. Perhaps her idea of simplicity is different from others’, because *Reflection* (like its predecessor *For You and I*) is a virtuosic display of dazzlingly complex drum programming and deeply nuanced emotional expression. James’ music sits where club styles like drum ’n’ bass and UK funky meet more idiosyncratic strains of IDM; her beats snap and lurch, wrapping grime- and drill-inspired drums in ethereal synths and glitchy bursts of white noise. Recorded in 2020, while the club world was paused, *Reflection* captures much of the anxiety and melancholy of that strange, stressful year. “It feels like the walls are caving in,” she whispers on the contemplative title track, an unexpected ambient oasis amid a landscape of craggy, desiccated beats. Despite the frequently overcast mood, however, guest turns on songs like “Black Ting” show a belief in the possibility of change. “The seeds we sow bear beautiful fruit,” raps Iceboy Violet on the Black Lives Matter-influenced closing track, “We’re Building Something New.” Tender and abrasive in equal measure, *Reflection* is that rarest of things: a work of experimental music that really does make another world feel possible.

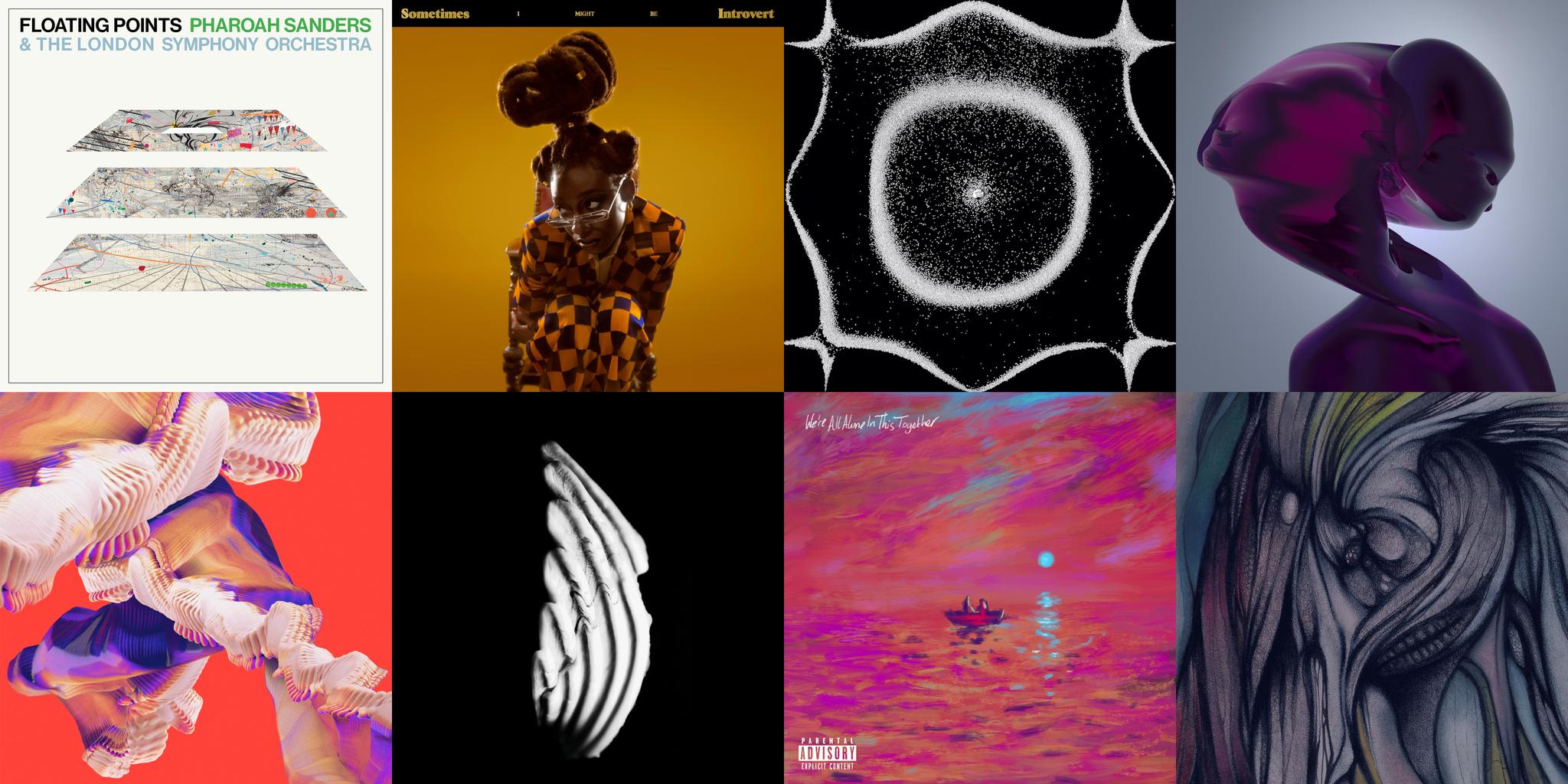

On their endlessly eclectic sophomore album, Bicep considers a musical inquiry most often circled by jazz and jam bands: What if tracks don’t need to be immutable, permanent records, but should instead transform and evolve? Taking inspiration from their first major tour—a two-year trek between festivals and clubs during which they’d regularly rework their tracks from the road—the Northern Irish duo freed themselves from the idea that songs had to be fixed. “Club music has to draw you out,” Matt McBriar tells Apple Music. “Headphone music has to pull you in. More often than not, we’d wind up with six different versions of each song. Eventually it was like, ‘Why do we have to choose?’” As a result, the album versions on *Isles* are simply jumping-off points—the best headphones-inclined versions the pair could cut (dance-floor edits will inevitably materialize when they bring the tracks into clubbier environments). “There’s no straight house or techno on this album; those versions will come later,” Andy Ferguson says. “We wanted to explore home listening to its fullest extent, and then explore the live show to its fullest extent. Rather than try to do both at once, we decided to serve each.” Taking this approach presented an interesting challenge: In order for the songs to be malleable *and* recognizable, they needed to have a strong foundation. “They couldn’t be reliant on a single composition, they had to work in different forms,” McBriar says. “We had to make sure they had strong DNA.” Below, the pair—self-described geeks and gear-heads eager to get technical—take us inside the creative process behind each track. **Atlas** McBriar: “This was the first track we finished after coming back from the tour. We tried to capture the feelings from the peak of the live show, that optimism and euphoria in the room when we performed. It set the tone for the rest of the album in terms of our process. Although we initially recorded several different melodies, the final form came together a few months later in a single afternoon on our modular. This riff was the strongest.” **Cazenove** Ferguson: “This was another early demo, and was sparked by our obsessive interest in ’90s technology—the old MPC controllers that Timbaland and Dilla used. That old equipment doesn’t produce instantly crisp sounds or perfect beats, but that’s where the beauty is. It’s fuzzy and imprecise. We were experimenting with a lot of ’90s lo-fi samplers and bit crushers, and the idea was to build a rhythm by feeding our MPC through a reverse reverb patch on the Lexicon PCM96. From there we just added layer upon layer. We wanted something fast and playful, but with a lot less emphasis on the dance floor.” **Apricots** McBriar: “This actually began as an ambient piece, and the strings sat on our hard drive for a year before we considered some vocals. One day, we picked up an amazing, recently released record called *Beating Heart - Malawi*. The vocals and polyrhythms of ‘Gebede-Gebede Ulendo Wasabwera’ stood out. They were captivating. We pitched snippets of them to our strings before building the rest of the track around them. The second sample is from the 1975 \[Bulgarian folk\] album *Le Mystere Des Voix Bulgares*. We connected with the mysterious chanting, and felt like it had parallels to the Celtic folk we grew up hearing.” **Saku (feat. Clara La San)** McBriar: “This began as a footwork-inspired track with a hang drum melody; we’d been looking into polyrhythms and more interesting drum programming. But when we slowed down the tempo from 150 to 130 BPM, it totally flipped the vibe for us. We experimented with several different vocals samples—including ‘Gebede-Gebede Ulendo Wasabwera’ before it wound up on ‘Apricots’—but ended up sending a stripped-back version to Clara La San, who brought a strong ’90s UKG/R&B vibe. We added some haunting synths at the end to bring contrast and some opposing dark and light elements. It was great to pull so many of our influences into one track.” **Lido** Ferguson: “This track was born from one of our many experiments with granular synthesis. We cut a single piano note from a catalog of 1970s samples and fed it into one of our granular samplers. As we experimented with recording it live, the synthesizer glitches and jumps added all this character and texture. It was pretty disorderly and hard to control, but we loved the madness it produced. There are a ton of layers to this track despite it sounding so simple. And mixing it was a lot of work, trying to get that balance between soothing and subtle chaos.” **X (feat. Clara La San)** McBriar: “This track was built around our Psycox SY-1M Syncussion. We’d been hunting for a Pearl original for years. It has all these uncompromising, metallic fizzes and bleeps that are so difficult to tame, you really need to start with it as the center of the track. Most tracks on the album began on the piano, but not this one. The frantic synth melody was actually improvised one afternoon on our Andromeda A6; it was a single take on a heavily customized and edited patch that we\'ve never been able to replicate. It was just one of those moments when you hit ‘record’ and get it right.” **Rever (feat. Julia Kent)** Ferguson: “We started this track in Bali in 2016. We were on tour and had access to a studio full of local instruments, and knew right away that we wanted to use them. We recorded long sessions of us playing them live, but never ended up using them in one of our finished tracks. Several years later, we were working with Julia Kent, who had recorded the strings for another demo, but it just wasn’t working. She tried some of the Bali instrumentals instead. It sounded really unique. The chopped-up vocal came last, edited and re-pitched to fit, almost like a melody.” **Sundial** McBriar: “One of the simplest tracks on the album, ‘Sundial’ grew from a faulty Jupiter 6 arp recording. Our trigger wasn’t working properly and the arp was randomly skipping notes. This was a small segment taken from a recording of Andy playing around with the arp while we were trying to figure out what was going wrong. We actually loved what it produced and wrote some chords around it, guided by the feeling of that recording.” **Fir** Ferguson: “We have a real soft spot for choral vox synths, and this track was born from an experiment with those. It\'s actually one of the fastest songs we\'ve ever made, and grew purely out of those days in the studio when we just jammed, trying new things. No direction, no preconceived ideas, we just felt it out.” **Hawk (feat. machina)** Ferguson: “The melody on ‘Hawk’ is actually our voices mapped and re-pitched to a granular sampler. We experimented a lot with re-pitching on this album; it brings this unique quality to vocals and melodies. We have a rare-ish Japanese synth, the Kawai SX-240, which creates all those super weird synth noises. Again, this track was the product of lots of experimentation. Machina\'s vocal\'s were actually for another demo which we were struggling on and it just worked perfectly.”

Belfast-born, London-based duo Bicep (Matt McBriar and Andy Ferguson) release their hotly anticipated second album, “Isles”, on 22 January 2021 via Ninja Tune. Two years in the making, “Isles” expands on the artful energy of their 2018 debut “Bicep”, while digging deeper into the sounds, experiences and emotions that have influenced their lives and work, from early days in Belfast to their move to London a decade ago. “We have strong mixed emotions, connected to growing up on an island” they say, “wanting to leave, wanting to return”. “Isles” is, in part, a meditation on these contradictions, the struggle between the expansive and the introspective, isolation and euphoria. The breadth of music they’ve been exposed to in London during this time informs “Isles’” massive sonic palette; both cite the joy of discovering Hindi vocals overheard from distant rooftops, snatches of Bulgarian choirs drifting from passing cars, hitting Shazam in a kebab house in the vain hopes of identifying a Turkish pop song. But time away from home has also made the pair more reflective about the move between islands which led them here. For two natives of Belfast, any talk of islands, communities and identities will also have other, more domestic connotations. Before this project, it was an aspect of their lives they’d been reluctant to talk about. “It’s always been an unquantifiable topic for us” says Matt. “We’re not religious, but we're both from different religious backgrounds. There was always a lot of interest in us talking about that part of things in the early days, but we weren’t interested. We always felt that one of the things we loved about dance music was that freedom it gave you to be released from talking about those things. It provided a middle ground. I think we took for granted how much that meant at that time”. “Isles” is, perhaps, a chance to explore this background in ways that don’t conform to the stale, sensationalist narratives about Northern Ireland that predominate elsewhere; to ground those experiences in reality, and reflect on the gaps music can and can’t bridge. “You’d enter the club and it would be people from both sides of the tracks and they’d be hugging” says Andy, referring to massively influential Belfast club Shine, where both cut their musical teeth. “And the following week, they’d be with their mates rioting. It felt like the safest place but, on paper, it should have been the most dangerous”. Musically, too, they find echoes of those days in their work. “It was like being smacked in the head with a hammer” Matt says, of the tunes that defined that scene, and which find expression in “Isles’” most raw and energetic corners. “It was either very intense, in-your-face Italo tinged electro or really aggressive techno”. ‘Atlas’, the first track drawn from the record, speaks to these roots. Released to massive acclaim in March, making both the Radio 1 and Radio 6 playlists, its euphoric energy and bittersweet heft hit all the harder in uncertain times. It is, as Resident Advisor called it, “music that commiserates with you while you try to dance out your anxieties”. Lead single ‘Apricots’ has a similar feel, steeped in a shimmering bath of warm synths, its spare percussion and arresting vocals bring the big room chills of 90s rave, while still evoking something lost or forlorn. It’s a tone perfectly captured in ‘Apricots’ soulful and disorienting video by Mark Jenkin, fresh from winning 2020’s Bafta for Outstanding Debut by a British Director for his film ‘Bait’, or the album’s striking, explosive artwork by Studio Degrau, creators of the iconic imagery for the duo’s first album. “The previous record was written from a very happy and almost naïve place” says Andy. “On your first album, you can finally express what you can’t on an A-side or an EP. But, touring it for three years, you figure out what makes a good song; what gives it longevity”. Drawing on this experience, the pair wanted “Isles” to be a “a snapshot in time” of their work in this period, rather than a start-to-finish concept album. To do this, they drew from a massive pool of 150 demos. Whittling the record down to ten tracks was their first major challenge. “That’s the creative element in the beginning” Matt says. “The blue sky approach; stitching stuff together and jamming over the top. But then you get to the next phase where you tell a story with what you’ve got, get them to communicate what we feel when we listen to them. We’d spend a week working on a track and find a breakthrough moment where it would work in so many iterations. It comes alive as a piece”. “On an album, you want loads of detail for people listening at home” adds Andy. These details are everywhere on “Isles”. ‘Saku’s two step polyrhythms and Clara La San’s honey-sweet vocals feint toward UK Garage before diving, chest-first, into cosmic synths. Like 90’s RnB channelled through peak John Carpenter, it’s a track that demands, and rewards, multiple listens, suffused with the melancholic undercurrent that gives “Isles” its cathartic punch. ‘Cazenove’, another standout, pairs pitch-shifted choral elements with moody pizzicato strings and rave synths, combining to form a slowly building retro-futurist soundscape, Studio Ghibli one moment, Studio 54 the next. This globe-trotting sound was forged as their own rapid ascent through the musical ranks began. After starting their legendary FeelMyBicep blog in 2008, its humble trove of Italo, house and disco deep cuts grew into a runaway success, regularly chalking up over 100,000 visitors a month. Once the blog had spawned a record label and club night, the duo were propelled on to the international stage via sought-after DJ sets that reflected the eclecticism of their online curations. Following success with productions for Throne of Blood and Aus Music, Bicep were signed to Ninja Tune in 2017, where they released their wildly acclaimed self-titled debut album the following year, attaining a Top 20 entry in the UK charts, and a cover feature in Mixmag to add to the magazine’s gong for “Album of the Year”. Tracks like ‘Opal’ — and the subsequent Four Tet remix— as well as he record’s lead single ‘Glue’, with and its iconic Joe Wilson-directed video, became touchpoints for electronic music in 2017, with the latter named DJ Mag “Track of the Year”. The ‘Glue’ video, alongside Bicep’s RA Live performance were also recently included in the lauded ‘Electronic’ exhibition, first shown at the Philharmonie de Paris last year and most recently at London’s Design Museum. The album was followed by a massively successful tour, which saw them raise the roof at Primavera, Coachella and Glastonbury. The pair sold out their two forthcoming Brixton Academy shows in a matter of minutes, and amassed a 10,000 person waiting list once tickets were all gone. Plans for an extensive “Isles” tour in 2021 are still in the offing, with the duo offering only cryptic clues as to what it will entail. “This is the home listening version”, says Matt, “the live version will be much, much harder”. Bicep’s booked events will now take place as and when venue schedules become more clear, with additional headline dates across the UK, EU and US hoped for in 2021, including a headline slot at Field Day in London, as well as performances at Parklife, Roskilde, Creamfields, Primavera, MELT! And more. With the live music & touring industry in a state of flux, Bicep recently undertook a one-off ticketed livestream performance—one of the first of its kind for an electronic artist—broadcast across 5 different timezones, and watched by people in over 70 countries, with visuals by close BICEP LIVE visual collaborator Black Box Echo. Bicep will also launch their ‘FeelMyBicep Radio’ show on Apple Music in October, giving listeners an insight into the music that has shaped everything in the world of Bicep, with shows set to continue monthly throughout the coming year. Bicep are also ambassadors for Youth Music, a charity working to change the lives of young people through music and music production. Both take an active role in mentoring young people coming through YM programmes, reflecting their own eagerness to give back as musicians who themselves received industry support when they were coming up. For more information please see www.youthmusic.org.uk/what-we-do

It’s perhaps fitting that Dave’s second album opens with the familiar flicker and countdown of a movie projector sequence. Its title was handed to him by iconic film composer Hans Zimmer in a FaceTime chat, and *We’re All Alone in This Together* sets evocative scenes that laud the power of being able to determine your future. On his 2019 debut *PSYCHODRAMA*, the Streatham rapper revealed himself to be an exhilarating, genre-defying artist attempting to extricate himself from the hazy whirlwind of his own mind. Two years on, Dave’s work feels more ambitious, more widescreen, and doubles down on his superpower—that ability to absorb perspectives around him within his otherworldly rhymes and ideas. He’s addressing deeply personal themes from a sharp, shifting lens. “My life’s full of plot holes,” he declares on “We’re All Alone.” “And I’m filling them up.” As it has been since his emergence, Dave is skilled, mature, and honest enough to both lay bare and uplift the Black British experience. “In the Fire” recruits four sons of immigrant UK families—Fredo, Meekz, Giggs, and Ghetts (all uncredited, all lending incendiary bars)—and closes on a spirited Dave verse touching on early threats of deportation and homelessness. With these moments in the can, the earned boasts of rare kicks and timepieces alongside Stormzy for “Clash” are justified moments of relief from past struggles. And these loose threads tie together on “Three Rivers”—a somber, piano-led track that salutes the contributions of Britain’s Windrush generation and survivors of war-torn scenarios, from the Middle East to Africa. In exploring migration—and the questions it asks of us—Dave is inevitably led to his Nigerian heritage. Lagos newcomer Boj puts down a spirited, instructional hook in Yoruba for “Lazarus,” while Wizkid steps in to form a smooth double act on “System.” “Twenty to One,” meanwhile, is “Toosie Slide” catchy and precedes “Heart Attack”—arguably the showstopper at 10 minutes and loaded with blistering home truths on youth violence. On *PSYCHODRAMA* Dave showed how music was his private sanctuary from a life studded by tragedy. *We’re All Alone in This Together* suggests that relationship might have changed. Dave is now using his platform to share past pains and unique stories of migration in times of growing isolation. This music keeps him—and us—connected.

The record is his first bonafide 140bpm record. All of the tracks on the record have been road-tested in Calibre's DJ sets over the last 2/3 years with many of them being sought-out by his hardcore fans. It was only a matter of time then that he put them out for all to consume. With a nod to the dancefloor, the clear idea for the album came about following the release of his most personal album to date ‘Planet Hearth’. “It still works in the headspace but ultimately it's been written for the sweaty club experience we miss now, also after an album like Planet Hearth it felt very liberating to do,” he remarks. When writing albums, he often just puts it down to the general chaos of life, not citing any one influence but generally just waits to see what comes. With one of the tracks on the album written 7 years ago on the island of Valentia, It became a project that he spent the intervening years collecting tracks for, not really knowing when he was going to put it together as an album. “The whole album is special to me, everything on there has import and meaning beyond for me, I have spent much time on all these and hope they are special for other people too.”

“I can only work by being really open,” Welsh electronic producer Lewis Roberts, aka Koreless, tells Apple Music. “If I don’t start a piece of music by being inquisitive and playful, I lose interest very quickly.” This inherent curiosity forms the basis of his shape-shifting releases. Coming to prominence with his post-dubstep-influenced debut EP, 2011’s *4D*, and then working with labelmate Sampha before releasing its synth-heavy follow-up, *Yugen*, in 2013, Koreless has spent the past six years without any solo releases. Instead, he collaborated with Sharon Eyal’s groundbreaking dance company L-E-V for 2019’s Bold Tendencies festival, produced for FKA twigs’ acclaimed album *MAGDALENE*, and endlessly refined his long-awaited debut album—the aptly titled *Agor*, which means “open” in Welsh. Throughout its rigorously edited 10 tracks, Koreless toys with notions of tension and release, building expectations through crescendos of intensity before thwarting the cathartic payout with an immediate cut to blissful spaciousness. “You can accelerate a rhythm so much that it stops being heard as rhythm and, instead, becomes a single tone,” he explains. “That’s what I’m doing with these arrangements—pushing you to a threshold point until you burst through the chaos into an entirely new feeling and experience.” Here, he dives deeper into each of *Agor*’s tracks. **“Yonder”** “‘Yonder’ is a prelude to the record, like the lights coming up for a moment before we begin. It feels like an empty stage where nothing is really happening yet; it’s just providing a general feel. It was important to start like this, because the rest of the record can be quite melody-heavy, so I wanted something to welcome the listener in first.” **“Black Rainbow”** “I wanted ‘Black Rainbow’ to be a digital folk song. It builds in intensity as I’m squeezing every drop out of it. But then we reach a threshold that we break through, and it just becomes very blissful. The song is like taking off and accelerating into total bliss rather than into chaos. That’s one of the aims behind the record—to enable these ruptures and then to accelerate into a peaceful state.” **“Primes”** “This track is my homage to someone like Oren Ambarchi, since it’s just made of sine waves, which are the perfect, irreducible sound. You can’t get any simpler than a sine wave; it’s what you’re left with when you strip everything else away. I really like working with sines because they’re very general and there’s something comforting about their generality. I used to work a lot more with them, and this is probably their only place on the record. It plays like shards of sine wave dust.” **“White Picket Fence”** “I like using vocals almost like instruments and capturing the material quality of them, rather than having an artist feature. I like an anonymous, slightly inhuman vocal, which is why these vocals are just played through a keyboard. There’s a comforting safety to a vocal that sounds like it’s been grown in a lab, and on this track, I’m trying to separate them from any personality as much as possible and just keep them as these angelic, general voices.” **“Act(S)”** “This was the same tune as ‘White Picket Fence,’ but I decided to chop it halfway. It felt like ‘White Picket Fence’ needed to finish there and that this ending had a certain sculptural difference to it. I love when albums have extra sections tagged on at the end of a song. They aren’t interludes but rather a moment to breathe.” **“Joy Squad”** “I like when you’re in a club and you hear a song that is a bit of a roller-coaster and that can take you on a wild and unexpected ride without ruining everyone’s night. I was trying to find a version of that with ‘Joy Squad.’ I think of it as being a giant in terms of visualizing the sonic scale, because it’s quite an empty soundworld, so everything fills up much bigger in that space—it doesn’t just feel like microtones.” **“Frozen”** “I was exploring how you can use a vocal to get it to sound like percussion. Both this and ‘Joy Squad’ are using vocals in that way to make very short, percussive sounds. This is about finding that moment of beauty before failure—like having blind faith just before everything falls apart—and that was the structure of the song. I wanted to create a digital, sugary sweetness and I was getting there through very heavy-handed vocal processing.” **“Shellshock”** “The themes of ‘Shellshock’ are similar to ‘Frozen’ in trying to tread this line between something super-sweet and sincere and then some kind of creeping fear underneath. All of this builds to create that same sense of rupture and disassembly we find in ‘Black Rainbow.’” **“Hance”** “This one’s a little machine—it feels like a Heath Robinson device, a bionic music box. This is a short track, but it might have been one of the ones that took the longest to make. With a lot of these shorter ideas, I didn’t want to make them into full songs—they are enough however long they are. It’s a nice palate cleanser before we end.” **“Strangers”** “This was the last track to be written for the record. It felt like a lot of the previous songs had been really labored over and almost strangled tight, whereas ‘Strangers’ came together really quickly. It feels less constrained and like there’s more life to it because of that. It was fun to make and it works really well to tie everything together as the final tune. It is a joyful ending.”

“Right then, I’m ready,” Adele says quietly at the close of *30*’s opening track, “Strangers By Nature.” It feels like a moment of gentle—but firm—self-encouragement. This album is something that clearly required a few deep breaths for Tottenham’s most celebrated export. “There were moments when I was writing these songs, and even when I was mixing them and stuff like that, where I was like, ‘Maybe I don\'t need to put this album out,’” she tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “Like, ‘Maybe I should write another.’ Just because music is my therapy. I\'m never going into the studio to be like, ‘Right, I need another hit.’ It\'s not like that for me. When something is more powerful and overwhelming \[to\] me, I like to go to a studio, because it\'s normally a basement and there\'s no fucking windows and no reception, so no one can get ahold of me. So I\'m basically running away. And no one would\'ve known I\'d written that record. Maybe I just had to get it out of my system.” But, almost two years after much of it was completed, Adele did release *30*. And remarkably, considering the world has been using her back catalog to channel its rawest emotions since 2008, this is easily Adele’s most vulnerable record. It concerns itself with Big Things Only—crippling guilt over her 2019 divorce, motherhood, daring to date as one of the world’s most famous people, falling in love—capturing perfectly the wobbly resolve of a broken heart in repair. Its songs often feel sentimental in a way that’s unusually warm and inviting, very California, and crucially: *earned*. “The album is for my son, for Angelo,” she says. “I knew I had to tell his story in a song because it was very clear he was feeling it, even though I thought I was doing a very good job of being like, ‘Everything’s fine.’ But I also knew I wasn’t being as present. I was just so consumed by so many different feelings. And he plucked up the courage to very articulately say to me, ‘You’re basically a ghost. You might as well not be here.’ What kind of poet is that? For him to be little and say ‘I can’t see you’ to my face broke my heart.” This is also Adele’s most confident album sonically. She fancied paying tribute to Judy Garland with Swedish composer Ludwig Göransson (“Strangers By Nature”), so she did. “I’d watched the Judy Garland biopic,” she says. “And I remember thinking, ‘Why did everyone stop writing such incredible melodies and cadences and harmonies?’” She felt comfortable working heartbreaking bedside chats with her young son and a voice memo documenting her own fragile mental state into her music on “My Little Love.” “While I was writing it, I just remember thinking of any child that’s been through divorce or any person that has been though a divorce themselves, or anyone that wants to leave a relationship and never will,” she says. “I thought about all of them, because my divorce really humanized my parents for me.” The album does not steep in sorrow and regret, however: There’s a Max Martin blockbuster with a whistled chorus (“Can I Get It”), a twinkling interlude sampling iconic jazz pianist Erroll Garner (“All Night Parking”), and the fruits of a new creative partnership with Dean Josiah Cover—aka Michael Kiwanuka, Sault, and Little Simz producer Inflo. “The minute I realized he \[Inflo\] was from North London, I wouldn’t stop talking to him,” she says. “We got no work done. It was only a couple of months after I’d left my marriage, and we got on so well, but he could feel that something was wrong. He knew that something dark was happening in me. I just opened up. I was dying for someone to ask me how I was.” One of the Inflo tracks, “Hold On,” is the album’s centerpiece. Rolling through self-loathing (“I swear to god, I am such a mess/The harder that I try, I regress”) into instantly quotable revelations (“Sometimes loneliness is the only rest we get”) before reaching show-stopping defiance (“Let time be patient, let pain be gracious/Love will soon come, if you just hold on”), the song accesses something like final-form Adele. It’s a rainbow of emotions, it’s got a choir (“I got my friends to come and sing,” she tells Apple Music), and she hits notes we’ll all only dare tackle in cars, solo. “I definitely lost hope a number of times that I’d ever find my joy again,” she says. “I remember I didn’t barely laugh for about a year. But I didn’t realize I was making progress until I wrote ‘Hold On’ and listened to it back. Later, I was like, ‘Oh, fuck, I’ve really learned a lot. I’ve really come a long way.’” So, after all this, is Adele happy that *30* found its way to the world? “It really helped me, this album,” she says. “I really think that some of the songs on this album could really help people, really change people’s lives. A song like ‘Hold On’ could actually save a few lives.” It’s also an album she feels could support fellow artists. “I think it’s an important record for them to hear,” she says. “The ones that I feel are being encouraged not to value their own art, and that everything should be massive and everything should be ‘get it while you can’… I just wanted to remind them that you don’t need to be in everyone’s faces all the time. And also, you can really write from your stomach, if you want.”

Twelve years after Joy Orbison’s “Hyph Mngo” upended dubstep and forever changed the course of bass music, the UK DJ/producer, born Peter O’Grady, has yet to put out his debut album. In fact, “I’ve never wanted to write an album,” he tells Apple Music. So, *Still Slipping Vol. 1*, the most substantial offering he’s released yet, might present something of a conceptual hurdle: Its 14 tracks and 46-minute runtime would seem to have all the outward trappings of a bona fide full-length. O’Grady, however, insists that it is not. Instead, he claims, it’s a mixtape. “I listen to a lot of rap mixtapes,” he says. “There’s something quite playful and a little bit more personal about them. Dance albums always feel very put on a pedestal. But with hip-hop tapes, there’s so much energy and excitement. It feels really fresh and unpretentious.” A similar energy runs through *Still Slipping Vol. 1*: Though its muted production constitutes some of the most experimental material in Joy Orbison’s catalog, it’s propelled by lithe garage and drum ’n’ bass rhythms, and it’s stitched together with Voice Notes from O’Grady’s family members. Reminiscing about his grandfather, laughing about a weekend of daiquiris, or even, in the case of one charming recording of his mother, simply praising the young musician’s production chops, these spoken bits lend an intimate air; you feel like you’re eavesdropping on his private life. O’Grady made the record during the 2020 COVID lockdown; cooped up at home, he saw no one for months, communicating with his family only via FaceTime. That sense of isolation bleeds through into some of the record’s darker tracks, like the gothic trap of “Bernard?” or the bit-crushed textures and paranoid jitter of “Glorious Amateurs.” But the spirit of collaboration also courses through the music. Working with an array of rappers, singers, and fellow producers—at first socially distanced and eventually in person—O’Grady took the opportunity to try out new sounds and styles, folding in the grit of post-punk on “’Rraine” and the reflective tenor of dub poetry on “Swag W/ Kav,” a flickering UK garage floor-filler. Here, he explains the backstories behind selected songs from the mixtape. **“W/ Dad & Frankie”** “My dad’s not a massive talker. You’ve got to get stuff out of him. He didn’t know he was being recorded; he was just in a good mood with his brother. My dad was a bit of a mod in the suedehead era, and they’re talking about clothing. I liked it because it’s a nice moment between my dad and his brother, but it’s also painting a picture of something that I find quite interesting. I’m quite influenced by post-punk, and kicking off the record, I was thinking about that; there’s a guitar sample in there.” **“Sparko” (feat. Herron)** “Sam Herron and I did all of this just sending loops and ideas back and forth. I’m really into vocals and vocal melodies, but also the industrial side of things—I’m always trying to bring the soul out of something that’s quite abstract or a bit tougher. This track is him pushing it one way and me pushing it the other way and, hopefully, getting this interesting balance. It came together really quickly; it’s probably one of the last things I did on the record. I like it because it has this really good energy. It’s quite danceable. I play a lot of stuff around that BPM range when I DJ longer sets. We all come from a broken-beat background at 140 BPM, which maybe seems less interesting to us now. At slower tempos, you have more space.” **“Swag W/ Kav” (feat. James Massiah & Bathe)** “I was listening to a lot of 2-step and garage again. It’s something that I’m really influenced by, but I’m so sensitive about doing it, because I hold it in such high regard. Now there’s a throwback aspect, and the trend is really popular. But I think it’s hard for people now to imagine how sophisticated it seemed. I wanted to carry that sophistication on; I wanted to carry that energy into the track. I wanted to write a garage track that you could play like a minimal house track—something you could slip in at the right party and it wouldn’t be a throwback.” **“Better” (feat. Léa Sen)** “When I made this, I was thinking about people like Photek. I’m a massive Photek fan, and the way he approached house music and soulful vocal stuff always sat well with me. It’s uplifting but also melancholic. Drum ’n’ bass was always like that for me. But the nice thing about Léa is she’s 21 and she doesn’t necessarily know a lot of the things I was thinking about. I feel like her vocal is more like her doing a Frank Ocean vocal, which I love.” **“Bernard?”** “This is one I didn’t make during COVID, actually. It was originally called ‘Amtrak’ because I made it on an Amtrak train going from New York to Washington. The reason it’s called ‘Bernard?’ is because of Bernard Sumner. I’m a big New Order fan, and when I made it, I was thinking, ‘What if New Order made a hip-hop beat?’” **“Runnersz”** “This was one of the first Voice Notes I got sent where I was like, ‘Yeah, I have got to use this.’ Mia is my cousin; she’s also Ray Keith’s daughter—my uncle, who does the drum ’n’ bass stuff. I remember her being born, and now she’s 21 or something. She and her sister seemed to grow up quickly in lockdown, and it made me think about them now coming to clubs and falling in love and stuff like that.” **“’Rraine” (feat. Edna)** “Lorraine is my mom’s name, but my dad never says Lorraine—he just says ’Rraine. This is a song that me and Edna wrote, and then it morphed into what it is now. I do a lot of sessions with rappers and singers, and this was one of the beats I was giving to rappers. I got a few different vocals on it, but then I did a session with Edna. She’s in a band called Goat Girl—more post-punk type stuff. Weirdly, she really took to that track. It became this sort of—I don’t even know how I’d describe it. I’m a big Cocteau Twins fan, and I guess I was thinking about that kind of thing, but it isn’t really that, is it? It’s definitely leaning into my emo stuff.” **“Glorious Amateurs”** “I can’t even remember how this one came about. Someone once said to me that I write music like it’s coming out of a tube of toothpaste or something. This is one of the few that I would say I agree with that assessment. My manager didn’t really want to put it on the record, and I pushed. I said, ‘No, this one has to go on there.’” **“Froth Sipping”** “This was quite an old one, actually. When we were putting the tape together, we were going through a lot of my demos and I was like, ‘Oh, that’s actually quite good.’ I don’t really remember how I did a lot of it. I feel like it was quite modular-based. I think it’s even got some of the same ideas as ‘81B.’ I used to do a lot of that—build tracks out of other tracks. Things would just morph into other things.” **“Layer 6”** “I was with my mum and dad at Christmas, and my mum was talking about my radio show. She was like, ‘You should listen to Pete’s radio show. I think you’d like it.’ And my dad turns to me and goes, ‘It’s not for me though, is it? I’m nearly 70. Your mum can sit there and say it’s great, but it’s not really for her either.’ My parents have got really good musical taste, but they’re not musical people as such—they don’t play instruments. So, it’s kind of a sweet moment where my mum is trying to make sense of what I do and say something positive.” **“Playground” (feat. Goya Gumbani)** “This one, again, is thinking about stuff like Cocteau Twins. There was that really interesting point in post-punk—if you listen to the first Bauhaus record, that’s pretty much like a dub record. That fascinates me. I was thinking about that a bit when I made that beat. Goya, who’s the rapper, just has a really good ear. He came round and I was playing things and he was like, ‘Oh, that one.’ He could hear what he calls his ‘pocket,’ where the vocals would sit. It changed quite a bit once he jumped on it. I had been working on it with this vocalist who I was thinking could be the new Elizabeth Fraser. I was envisioning myself in this goth band. And then I played it for Goya, because the track wasn’t working out. It was two worlds colliding.” **“Born Slipping” (feat. TYSON)** “I like the idea of going out on a bit of a bang. It’s pretty straight up. It’s not trying to be anything particularly different, really. It’s quite an honest thing. It’s a bit garage-y, I love that. I’ve always loved a good vocal chop and a nice dubby synth. It’s the kind of thing that if I played it to my mates that I grew up with, they’d be like, ‘Oh yeah, why don’t you do this more?’”

Drummer Jamire Williams gained a high profile from 11 years in New York playing with Robert Glasper, Jason Moran, Dr. Lonnie Smith, and other major jazz artists. Since moving back to his native Houston, he has put a greater focus on his own genre-defying sound. *But Only After You Have Suffered*, for the groundbreaking International Anthem label, is a major step in that pursuit. While it is not his debut—his innovative 2016 solo drum album, *///// Effectual*, has that distinction—*But Only After You Have Suffered* finds Williams expanding his sonic palette, melodic sensibility, and curatorial scope as never before. Still, there are common threads: keyboardist Chassol and percussionist Carlos Niño, who played unobtrusive but significant roles on *///// Effectual*, are part of the mix here as well. Burniss Travis and Brandon Owens are among the bassists, joining a host of vocal guests, including the operatic Lisa E. Harris and the deeply soulful, richly contrasting Corey King and Kenneth Whalum. The roster of bold instrumentalists also includes Moran on piano, alto saxophonist Sam Gendel, DJ Flash Gordon Parks, bass clarinetist Jason Arce, and guitarist Matthew Stevens, as well as rappers Mic Holden, Fat Tony, and Zeroh. Darkly esoteric and inescapably grooving, *But Only After You Have Suffered* is a confident summation of Williams’ distinctively hybrid aesthetic, merging jazz, hip-hop, abstract pop, and futurist R&B in new ways.

Listening to Liz Harris’ music as Grouper, the word that comes to mind is “psychedelic.” Not in the cartoonish sense—if anything, the Astoria, Oregon-based artist feels like a monastic antidote to spectacle of almost any kind—but in the subtle way it distorts space and time. She can sound like a whisper whose words you can’t quite make out (“Pale Interior”) and like a primal call from a distant hillside (“Followed the ocean”). And even when you can understand what she’s saying, it doesn’t sound like she meant to be heard (“The way her hair falls”). The paradox is one of closeness and remove, of the intimacy of singer-songwriters and the neutral, almost oracular quality of great ambient music. That the tracks on *Shade*, her 12th LP, were culled from a 15-year period is fitting not just because it evokes Harris’ machine consistency (she found her creative truth and she’s sticking to it), but because of how the staticky, white-noise quality of her recordings makes you aware of the hum of the fridge and the hiss of the breeze: With Grouper, it’s always right now.

There’s a handful of eyebrow-raising verses across Tyler, The Creator’s *CALL ME IF YOU GET LOST*—particularly those from 42 Dugg, Lil Uzi Vert, YoungBoy Never Broke Again, Pharrell, and Lil Wayne—but none of the aforementioned are as surprising as the ones Tyler delivers himself. The Los Angeles-hailing MC, and onetime nucleus of the culture-shifting Odd Future collective, made a name for himself as a preternaturally talented MC whose impeccable taste in streetwear and calls to “kill people, burn shit, fuck school” perfectly encapsulated the angst of his generation. But across *CALL ME IF YOU GET LOST*, the man once known as Wolf Haley is just a guy who likes to rock ice and collect stamps on his passport, who might whisper into your significant other’s ear while you’re in the restroom. In other words, a prototypical rapper. But in this case, an exceptionally great one. Tyler superfans will remember that the MC was notoriously peeved at his categoric inclusion—and eventual victory—in the 2020 Grammys’ Best Rap Album category for his pop-oriented *IGOR*. The focus here is very clearly hip-hop from the outset. Tyler made an aesthetic choice to frame *CALL ME IF YOU GET LOST* with interjections of shit-talking from DJ Drama, founder of one of 2000s rap’s most storied institutions, the Gangsta Grillz mixtape franchise. The vibes across the album are a disparate combination of sounds Tyler enjoys (and can make)—boom-bap revival (“CORSO,” “LUMBERJACK”), ’90s R&B (“WUSYANAME”), gentle soul samples as a backdrop for vivid lyricism in the Griselda mold (“SIR BAUDELAIRE,” “HOT WIND BLOWS”), and lovers rock (“I THOUGHT YOU WANTED TO DANCE”). And then there’s “RUNITUP,” which features a crunk-style background chant, and “LEMONHEAD,” which has the energy of *Trap or Die*-era Jeezy. “WILSHIRE” is potentially best described as an epic poem. Giving the Grammy the benefit of the doubt, maybe they wanted to reward all the great rapping he’d done until that point. *CALL ME IF YOU GET LOST*, though, is a chance to see if they can recognize rap greatness once it has kicked their door in.

Some songs find their place in the world instantly and others take a while. Joy Crookes has been hanging on to some of the tracks on her debut album, *Skin*, since she was a teenager, waiting for the right moment for them to shine. This collection paints a portrait of a young woman of 23, finding her place in the world and understanding herself through her family—for better and worse—mixed in with songs that deal with social injustice and the Black Lives Matter movement. There’s also casual sex (“I Don’t Mind”) and the winding ancestral journeys that bring a family to London (“19th Floor”), as the South Londoner, of Bangladeshi and Irish heritage, pays tribute to the people and places that made her. “Biologically, our skin is one of the strongest organs in our body, but socially and externally, in terms of our identity, it can be used against us,” Crookes tells Apple Music of the album title. “And it’s not just a racial thing; it’s who we are that is used against us.” Read on as the singer-songwriter guides us through the powerful *Skin*, track by track. **“I Don’t Mind”** “I was in a casual relationship, or a casual situation-ship, at that time, and I kind of had to let the person know that it wasn\'t going to be anything more than what it was. I played the track to him and he didn\'t really get the picture. He was like, ‘I don’t really like this one.’ When I produced it, I was listening to Kanye’s *808s & Heartbreak* and Solange. I was really interested in how sonically there\'s a lot of grit and beauty in both of their production styles, so that was the inspiration.” **“19th Floor”** “The spoken bit at the beginning is me saying goodbye to my grandma on the 19th floor of her building in London. This is what I do every time I say goodbye to her, and she always gives me that beautiful ‘Okay, I love you.’ The strings were recorded in Abbey Road in Studio Two, which is The Beatles’ room and is also where Massive Attack recorded ‘Unfinished Sympathy.’ And the song is about how far my family’s come to give me the life that I have.” **“Poison”** “I wrote ‘Poison’ when I was 15. I was very angry—I think it was the angriest I\'d been in a very long time and one of the most angry points in my life. I had bought The Clash\'s box set, and there was a blank notebook in it that said ‘The future is unwritten’ on the cover. One of the lines I wrote in there was ‘You’re scared of snakes.’ I looked at that and wrote ‘Poison’ in like 10 minutes.” **“Trouble”** “It was kind of inspired by Prince’s ‘When Doves Cry.’ You know, when you love someone, you\'re so close to them, but you hurt the ones you love. The syncopation and beats in Bollywood music can sometimes kind of be reminiscent of Caribbean kind of syncopation.” **“When You Were Mine”** “I was writing a happy song but about a weird subject, as is usual with me. It\'s about my first love becoming gay after our relationship. The song is about being jealous of their love, but also celebrating the fact that my ex is who he is. The brass was inspired by \[legendary Ghanaian musician\] Ebo Taylor, who has an amazing way of making brass sound kind of drunk.” **“To Lose Someone”** “The conversation at the start of this song was recorded in a nail shop in Brixton. It was two days after my ex and I broke up, and my mum was giving me advice. There\'s a cello interlude there by \[arranger, composer, and cellist\] Amy Langley. And the song is about when you enter a relationship, you have to compromise or remove some of your baggage in order to be together. But at the same time knowing that when you do love someone, you are inevitably going to lose them at some point.” **“Unlearn You”** “There’s a line in this song: ‘Got a plate of pink cupcakes to sugarcoat the aftertaste.’ When I came out about something that happened to me to do with abuse, I was taken to a cupcake shop. The cupcakes were literally to sugarcoat the aftertaste. The scariest line is ‘I didn\'t ever wear a dress in case he thought I was asking for it.’ It’s a really difficult song to sing, not just in terms of the content, but the notes. It helped to write a song about my experiences. It gave me perspective and actually helped me heal.” **“Kingdom”** “I love post-punk music and bands like ESG and Young Marble Giants. I wrote it the day after the December 2019 election, when the Tory party were reelected. I think the whole of London was pissed off. And I was fucking pissed off. It\'s talking about my experience as someone that voted and didn\'t get the result I wanted, and what that meant for the future of our next few generations. I was fucking vexed.” **“Feet Don’t Fail Me Now”** “It\'s about a character that finds it easier to be complicit or performative in fear of actually speaking up about how they feel. And it was in light of the Black Lives Matter protests last year and the movement. I didn\'t have any answers, so I kind of just wanted to write a song that gave a little bit of the sign of the times, and also one that held myself accountable. Because I think we were all guilty of being complacent and performative because of fear, and the fear of cancel culture.” **“Wild Jasmine”** “‘Wild Jasmine’ is inspired by Tony Allen. There\'s kind of something South Asian about the way the guitar moves in that song. It’s about me telling my mom not to trust a man, or love him. Her name is Jasmine, and she is just like the plant—the plant naturally has to grow wild and it grows however it wants to. It felt like this man was not letting her do that. Are you going to accept wholefully, or wholesomely, who that person is? And it felt like he wasn’t.” **“Skin”** “This is kind of inspired by Frank Sinatra and his classic ballad-type songs. I wrote it the day after one of my friends was very much on the brink, and who felt like they weren\'t needed on this planet anymore. It was my way of telling them that they were, and that they have a life worth living—that’s literally what I said to them. And then I went in the next day. I was crying in the studio and I wrote them that song.” **“Power”** “It\'s about the abuse of power. And I think Boris Johnson is guilty of abusing power, as is Trump, as is Nigel Farage, as are all the arseholes, Priti Patel. People think it\'s a feminism song, but it\'s just about the abuse of power in general. Musically, I was inspired by Nina Simone and that kind of messiness and up-front vocal.” **“Theek Ache”** “Everyone always pronounces this wrong. ‘Theek ache’ is translated in the song; it means it’s okay. It’s a big warm hug at the end of the album after you\'ve listened to all these fucking heavy songs. I wrote it after drinking with Jodie Comer. It\'s just saying, ‘Sure, I\'m going to make mistakes, and I\'m going to be a human being, and I\'m going to make fuck-ups, and then I\'m going to go through this, that, and the other. But you know, it’s OK—I’ll have my kitten heels, cigarettes, and a mattress at the end of the night.’”

“Quivering in Time” is the debut album by DJ and producer Eris Drew on T4T LUV NRG, the label she runs with partner Octo Octa. In 2020, after the release of Trans Love Vibration (NAIVE, 2018) and Transcendental Access Point (Interdimensional Transmissions, 2020), Eris moved from her hometown of Chicago to rural New Hampshire and recorded the nine beautiful songs featured here. Her first album feels something like her DJ sets, with stacked layers of vinyl samples and turntable manipulations serving as a fast-moving foundation for hand-played keyboard riffs, walls of percussion and sampled, scratched and strummed guitar tones. On each song for the album Eris expresses the anxiety and hope of her present. She wrote, recorded, and mixed the album as she stared into the forest through her studio window, collapsing present and past into future, her memories and body literally quivering in time. The songs are cast with Eris’s experiences and intentions. The plucky progressive Loving Clav is in the form of an evocation (“good times come to me now....”), while the tracks Time to Move Close and Show U LUV express Eris’s longing for togetherness. The hardcore Pick ‘Em Up (“...and it might be a different story”) and organ-heavy Ride Free are funky odes to psychedelics, hard dancing and the subjectivity of real lived experience. The twinkling house of Howling Wind and the tempo-shifting bop of Sensation capture the mystery of the forest cabin where Eris spent most of the last 15 months. Two booming hip house dubs round out the album, Baby and Quivering in Time, each an itchy track about hope and personal resilience. As with her prior work, Eris’s approach to music making is unique and genre-dissolving. Ultimately, her special sound is a metaphor for her main message, which is that every person deserves to be themself.

“I don’t like to agonize over things,” Arlo Parks tells Apple Music. “It can tarnish the magic a little. Usually a song will take an hour or less from conception to end. If I listen back and it’s how I pictured it, I move on.” The West London poet-turned-songwriter is right to trust her “gut feeling.” *Collapsed in Sunbeams* is a debut album that crystallizes her talent for chronicling sadness and optimism in universally felt indie-pop confessionals. “I wanted a sense of balance,” she says. “The record had to face the difficult parts of life in a way that was unflinching but without feeling all-consuming and miserable. It also needed to carry that undertone of hope, without feeling naive. It had to reflect the bittersweet quality of being alive.” *Collapsed in Sunbeams* achieves all this, scrapbooking adolescent milestones and Parks’ own sonic evolution to form something quite spectacular. Here, she talks us through her work, track by track. **Collapsed in Sunbeams** “I knew that I wanted poetry in the album, but I wasn\'t quite sure where it was going to sit. This spoken-word piece is actually the last thing that I did for the album, and I recorded it in my bedroom. I liked the idea of speaking to the listener in a way that felt intimate—I wanted to acknowledge the fact that even though the stories in the album are about me, my life and my world, I\'m also embarking on this journey with listeners. I wanted to create an avalanche of imagery. I’ve always gravitated towards very sensory writers—people like Zadie Smith or Eileen Myles who hone in on those little details. I also wanted to explore the idea of healing, growth, and making peace with yourself in a holistic way. Because this album is about those first times where I fell in love, where I felt pain, where I stood up for myself, and where I set boundaries.” **Hurt** “I was coming off the back of writer\'s block and feeling quite paralyzed by the idea of making an album. It felt quite daunting to me. Luca \[Buccellati, Parks’ co-producer and co-writer\] had just come over from LA, and it was January, and we hadn\'t seen each other in a while. I\'d been listening to plenty of Motown and The Supremes, plus a lot of Inflo\'s production and Cleo Sol\'s work. I wanted to create something that felt triumphant, and that you could dance to. The idea was for the song to expose how tough things can be but revolve around the idea of the possibility for joy in the future. There’s a quote by \[Caribbean American poet\] Audre Lorde that I really liked: ‘Pain will either change or end.’ That\'s what the song revolved around for me.” **Too Good** “I did this one with Paul Epworth in one of our first days of sessions. I showed him all the music that I was obsessed with at the time, from ’70s Zambian psychedelic rock to MF DOOM and the hip-hop that I love via Tame Impala and big ’90s throwback pop by TLC. From there, it was a whirlwind. Paul started playing this drumbeat, and then I was just running around for ages singing into mics and going off to do stuff on the guitar. I love some of the little details, like the bump on someone’s wrist and getting to name-drop Thom Yorke. It feels truly me.” **Hope** “This song is about a friend of mine—but also explores that universal idea of being stuck inside, feeling depressed, isolated, and alone, and being ashamed of feeling that way, too. It’s strange how serendipitous a lot of themes have proved as we go through the pandemic. That sense of shame is present in the verses, so I wanted the chorus to be this rallying cry. I imagined a room full of people at a show who maybe had felt alone at some point in their lives singing together as this collective cry so they could look around and realize they’re not alone. I wanted to also have the little spoken-word breakdown, just as a moment to bring me closer to the listener. As if I’m on the other side of a phone call.” **Caroline** “I wrote ‘Caroline’ and ‘For Violet’ on the same, very inspired day. I had my little £8 bottle of Casillero del Diablo. I was taken back to when I first started writing at seven or eight, where I would write these very observant and very character-based short stories. I recalled this argument that I’d seen taken place between a couple on Oxford Street. I only saw about 30 seconds of it, but I found myself wondering all these things. Why was their relationship exploding out in the open like that? What caused it? Did the relationship end right there and then? The idea of witnessing a relationship without context was really interesting to me, and so the lyrics just came out as a stream of consciousness, like I was relaying the story to a friend. The harmonies are also important on this song, and were inspired by this video I found of The Beatles performing ‘This Boy.’ The chorus feels like such an explosion—such a release—and harmonies can accentuate that.” **Black Dog** “A very special song to me. I wrote this about my best friend. I remember writing that song and feeling so confused and helpless trying to understand depression and what she was going through, and using music as a form of personal catharsis to work through things that felt impossible to work through. I recorded the vocals with this lump in my throat because it was so raw. Musically, I was harking back to songs like ‘Nude’ and ‘House of Cards’ on *In Rainbows*, plus music by Nick Drake and tracks from Sufjan Stevens’ *Carrie & Lowell*. I wanted something that felt stripped down.” **Green Eyes** “I was really inspired by Frank Ocean here—particularly ‘Futura Free’ \[from 2016’s *Blonde*\]. I was also listening to *Moon Safari* by Air, Stereolab, Unknown Mortal Orchestra, Tirzah, Beach House, and a lot of that dreamy, nostalgic pop music that I love. It was important that the instrumental carry a warmth because the song explores quite painful places in the verses. I wanted to approach this topic of self-acceptance and self-discovery, plus people\'s parents not accepting them and the idea of sexuality. Understanding that you only need to focus on being yourself has been hard-won knowledge for me.” **Just Go** “A lot of the experiences I’ve had with toxic people distilled into one song. I wanted to talk about the idea of getting negative energy out of your life and how refreshed but also sad it leaves you feeling afterwards. That little twinge from missing someone, but knowing that you’re so much better off without them. I was thinking about those moments where you’re trying to solve conflict in a peaceful way, but there are all these explosions of drama. You end up realizing, ‘You haven’t changed, man.’ So I wanted a breakup song that said, simply, ‘No grudges, but please leave my life.’” **For Violet** “I imagined being in space, or being in a desert with everything silent and you’re alone with your thoughts. I was thinking about ‘Roads’ by Portishead, which gives me that similar feeling. It\'s minimal, it\'s dark, it\'s deep, it\'s gritty. The song covers those moments growing up when you realize that the world is a little bit heavier and darker than you first knew. I think everybody has that moment where their innocence is broken down a little bit. It’s a story about those big moments that you have to weather in friendships, and asking how you help somebody without over-challenging yourself. That\'s a balance that I talk about in the record a lot.” **Eugene** “Both ‘Black Dog’ and ‘Eugene’ represent a middle chapter between my earlier EPs and the record. I was pulling from all these different sonic places and trying to create a sound that felt warmer, and I was experimenting with lyrics that felt a little more surreal. I was talking a lot about dreams for the first time, and things that were incredibly personal. It felt like a real step forward in terms of my confidence as a writer, and to receive messages from people saying that the song has helped get them to a place where they’re more comfortable with themselves is incredible.” **Bluish** “I wanted it to feel very close. Very compact and with space in weird places. It needed to mimic the idea of feeling claustrophobic in a friendship. That feeling of being constantly asked to give more than you can and expected to be there in ways that you can’t. I wanted to explore the idea of setting boundaries. The Afrobeat-y beat was actually inspired by Radiohead’s ‘Identikit’ \[from 2016’s *A Moon Shaped Pool*\]. The lyrics are almost overflowing with imagery, which was something I loved about Adrianne Lenker’s *songs* album: She has these moments where she’s talking about all these different moments, and colors and senses, textures and emotions. This song needed to feel like an assault on the senses.” **Portra 400** “I wanted this song to feel like the end credits rolling down on one of those coming-of-age films, like *Dazed and Confused* or *The Breakfast Club*. Euphoric, but capturing the bittersweet sentiment of the record. Making rainbows out of something painful. Paul \[Epworth\] added so much warmth and muscularity that it feels like you’re ending on a high. The song’s partly inspired by *Just Kids* by Patti Smith, and that idea of relationships being dissolved and wrecked by people’s unhealthy coping mechanisms.”

Performed with Shirley Tetteh, James Mollison, Edward Wakili-Hick, Nubya Garcia, Dwayne Kilvington, Lyle Barton, Twm Dylan, Jake Long, Rudi Creswick, and Ahnansé. Space 1 Produced, Performed, Recorded by Nala Sinephro (Modular Synths, Synths, Harp) Mixed by Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 2 Performed by James Mollison (Saxophone), Lyle Barton (Piano), Shirley Tetteh (Guitar), Nala Sinephro (Synths), Jake Long (Drums), Rudi Creswick (Double Bass) Composed by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mixed by Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 3 Performed by Nala Sinephro (Modular Synths, Synths), Edward Wakili-Hick (Drums), Dwayne Kilvington (Synth Bass) Produced by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mixed by Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 4 Performed by Nubya Garcia (Saxophone) , Lyle Barton (Keys), Nala Sinephro (Synths), Jake Long (Drums), Twm Dylan (Double Bass), Nubya Garcia appears courtesy of Concord Jazz Composed by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Ben Bell and Nala Sinephro Mixed by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 5 Performed by Nala Sinephro (Modular Synths, Synths, Harp), Ahnansé (Saxophone), Shirley Tetteh (Guitar) Produced by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Nala Sinephro and Rick David Mixed by Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 6 Performed, Composed by Nala Sinephro (Synthesizer), James Mollison (Saxophone), Jake Long (Drums) Produced by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mixed by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 7 Produced, Performed, Recorded by Nala Sinephro (Modular Synths, Synths, Harp) Mixed by Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 8 Performed by Nala Sinephro (Modular Synths, Synths, Harp) and Ahnansé (Saxophone) Produced by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mixed and Mastered by Nala Sinephro Painting by Daniela Yohannes Design by Maziyar Pahlevan

TRACK CLIPS: soundcloud.com/on-rotation-music/adam-pits-a-recurring-nature-onro01-snippets We’re incredibly proud to announce the details of the first release on our label - an 8-track debut album from our resident Adam Pits. Inspired by nature and written during the first lockdown, the album shows off Adam’s classical cello background as well as a broad range of electronic styles you’ll already be familiar with. In his own words: “2020 became a year of turning misfortunes into new opportunities. The feelings of clubbing neglect and social deprivation were prominent and as a result I found myself locked away in the studio with nothing better to do than to write the music that I wished I was hearing on a large sound system in a room full of sweaty rave-goers. I was lucky enough to be surrounded by friends who were able to drag me out of the studio and get outside for some real TLC from nature. After copious amounts of elderflower picking and mushroom foraging I found myself at peace with the idea that maybe the studio wasn't my only safe place. This ended up being the catalyst for many of the ideas in the album, and in turn, helped me realise the similarities between the beauty of repetition in both music and nature. A Recurring Nature has come out as a genuine representation of where I’m at in my musical journey. Whilst seeking to express the aspects of music that most resonated with me, I wanted to also test myself against the elements where I felt least comfortable.” The LP will come in both digital and 2x12” vinyl formats, with the latter featuring full art from Patch and mastering from the renowned Analogcut studio. Pressed at Record Industry and distributed by One Eye Witness. We’ve poured a huge amount of time into making this the best it can be, we’re very happy with the results and hope you enjoy it as much as we do! We’ll see you on the next one!

Written after the birth of her first child (and just before the arrival of her second), *Colourgrade* finds London’s Tirzah Mastin taking a more experimental approach, wrapping moments of unadorned beauty in sheets of distortion, noise, woozy synthesizers, and listing guitars. It’s decidedly lo-fi—not the sort of album that actively invites you in. And yet, like its predecessor—her acclaimed 2018 debut LP, *Devotion*—this is naturally intimate music, alt-R&B that offers brief meditations on the coming together of both bodies (“Tectonic”) and collaborators (“Hive Mind,” which, in addition to seal-like background effects, features vocals from touring bandmate and South London artist Coby Sey). Working again alongside longtime friend and collaborator Mica Levi, Mastin sounds free here, at ease even as she obfuscates. On “Beating,” as she sings to her partner over a skittering drum machine and a layer of gaseous hiss, she stops for a moment to clear her throat, as if in quiet conversation late at night. “You got me/I got you,” she sings. “We made life/It’s beating.”

The American Negro is an unapologetic critique, detailing the systemic and malevolent psychology that afflicts people of color. This project dissects the chemistry behind blind racism, using music as the medium to restore dignity and self-worth to my people. It should be evident that any examination of black music is an examination of the relationship between black and white America. This relationship has shaped the cultural evolution of the world and its negative roots run deep into our psyche. Featuring various special guests performing over a deeply soulful, elaborate orchestration, The American Negro reinvents the black native tongue through this album and it’s attendant short film (TAN) and 4-part podcast (invisible Blackness). The American Negro - both as a collective experience and as individual expressions - is insightful, provocative and inspiring and should land at the center of our ongoing reckoning with race, racism and the writing of the next chapter of American history.