The New Yorker: Amanda Petrusich's Favorite Records of 2019

Amanda Petrusich on her favorite music of the year and of the decade, including records from Bon Iver, Frank Ocean, FKA twigs, Thom Yorke, and more.

Published: December 03, 2019 11:00

Source

Our third long player (this time a double!) and second on Thin Wrist / Black Editions. From our label: 75 Dollar Bill is one of the essential groups at the heart of NYC's underground. Centered on the telepathic union of Che Chen's microtonal electric guitar and Rick Brown's odd metered percussion, their long-form sound is unmistakable and compelling. Their second album, 2016's Wood Metal Plastic Pattern Rhythm Rock (Thin Wrist), presented the essence of their sound with vivid clarity. Since then the group have travelled and performed extensively, bringing their music to a wider audience and performing everywhere from bustling sidewalks and intimate clubs to large concert halls and overseas festivals. The countless miles and performances of the last few years have resulted in their expansive new double album I WAS REAL. Over four sides the group expands in bold new directions, embracing brilliant fuller orchestrations, joyous rockers and entrancing new textures. The record is enhanced by the presence of eight additional players over its nine tracks while also showing off the duo's strength when stripped down to its core. Requiring a variety of approaches, the album was recorded over a four year period, in four different studios in a range of different ensemble configurations. The album also features several “studio as instrument” constructions that harken back to the collage-experiments of the band’s early cassette tapes, while at the same time pointing to new territories altogether. The players involved highlight the “social” aspect of the band and the eight guests that appear on the record are some of the band’s closest friends and collaborators. While Che Chen and Rick Brown are always at the core of 75 Dollar Bill, the band is much like an extended family, changing shape for different music and different situations. Some pieces were conceived in the band's very early days and others are much newer, but the music is unmistakably 75 Dollar Bill. As Steve Gunn has written on their work: “Strings come in underneath Che Chen's supreme guitar tone. Rick Brown's trance percussion offers a guiding support with bass, strings, and horns supporting the melody. They have gathered all the moving parts perfectly.” I WAS REAL is a monumental signature work capturing the group at the peak of their powers.

Big Thief had only just finished work on their 3rd album, U.F.O.F. – “the celestial twin” – days before in a cabin studio in the woods of Washington State. Now it was time to birth U.F.O.F.’s sister album – “the earth twin” – Two Hands. 30 miles west of El Paso, surrounded by 3,000 acres of pecan orchards and only a stone’s throw from the Mexican border, Big Thief (a.k.a. Adrianne Lenker, Buck Meek, Max Oleartchik, and James Krivchenia) set up their instruments as close together as possible to capture their most important collection of songs yet. Where U.F.O.F.layered mysterious sounds and effects for levitation, Two Hands grounds itself on dried-out, cracked desert dirt. In sharp contrast to the wet environment of the U.F.O.F. session, the southwestern Sonic Ranch studio was chosen for its vast desert location. The 105-degree weather boiled away any clinging memories of the green trees and wet air of the previous session. Two Hands had to be completely different — an album about the Earth and the bones beneath it. The songs were recorded live with almost no overdubs. All but two songs feature entirely live vocal takes, leaving Adrianne’s voice suspended above the mix in dry air, raw and vulnerable as ever. “Two Hands has the songs that I’m the most proud of; I can imagine myself singing them when I’m old,” says Adrianne. “Musically and lyrically, you can’t break it down much further than this. It’s already bare-bones.” Lyrically this can be felt in the poetic blur of the internal and external. These are political songs without political language. They explore the collective wounds of our Earth. Abstractions of the personal hint at war, environmental destruction, and the traumas that fuel it. Across the album, there are genuine attempts to point the listener towards the very real dangers that face our planet. When Adrianne sings “Please wake up,” she’s talking directly to the audience. Engineer Dom Monks and producer Andrew Sarlo, who were both behind U.F.O.F., capture the live energy as instinctually and honestly as possible. Sarlo teamed up with James Krivchenia to mix the album, where they sought to emphasize raw power and direct energy inherent in the takes. The journey of a song from the stage to the record is often a difficult one. Big Thief’s advantage is their bond and loving centre as a chosen family. They spend almost 100% of their lives together working towards a sound that they all agree upon. A band with this level of togetherness is increasingly uncommon. If you ask drummer James Krivchenia, bassist Max Oleartchik or guitarist Buck Meek how they write their parts, they will describe — passionately — the experience of hearing Adrianne present a new song, listening intently for hints of parts that already exist in the ether and the undertones to draw out with their respective instruments. With raw power and intimacy, Two Hands folds itself gracefully into Big Thief’s impressive discography. This body of work grows deeper and more inspiring with each new album.

Over the decade-plus since he arrived seemingly fully formed as the platonic ideal of indie DIY made good, Justin Vernon has pushed back against the notion that he and Bon Iver are synonymous. He is quick to deflect credit to core longtime collaborators like Chris Messina and Brad Cook, while April Base, the studio and headquarters he built just outside his native Eau Claire, Wisconsin, has become a cultural hub playing host to a variety of experimental projects. The fourth Bon Iver full-length album shines a brighter light on Bon Iver as a unit with many moving parts: Renovations to April Base sent operations to Sonic Ranch in Tornillo, Texas, for much of the production, but the spirit of improvisation and tinkering and revolving-door personnel that marked 2016’s out-there *22, A Million* remained intact. “This record in particular felt like a very outward record; Justin felt outward to me,” says Cook, who grew up with Vernon and has played with him through much of his career. “He felt like he was in a new place, and he was reaching out for new input in a different way. We\'re just more in the foreground inevitably because the process became just a little bit more transparent.” Vernon, Cook, and Messina talk through that process on each of *i,i*\'s 13 tracks. **“Yi”** Justin Vernon: “That was a phone recording of me and my friend Trevor screwing around in a barn, turning a radio on and off. We chopped it up for about five years, just a hundred times. There’s something in that ‘Are you recording? Are you recording?’ that felt like the spirit that flows into the next song.” **“iMi”** Brad Cook: “It was like an old friend that you didn\'t know what to do with for a long time. When we got to Texas, a lot of different people took a crack at trying to make something out of that song. And then Andrew Sarlo, who works with Big Thief and is just a badass young producer, he took the whack that broke through the wall. Once the band got their hands on it, Justin added some of the acoustic stuff to it, and it just totally blew it wide open.” **“We”** Vernon: “I was working on this idea one morning with this engineer, Josh Berg, who happened to be out with us. And this guy Bobby Raps from Minneapolis was also at my studio just kind of hanging around, and he brought this dude named Wheezy who does some Young Thug beats, some Future beats. So I had this little baritone-guitar bass loop thing, and Wheezy put his beat on there. All these songs had a life, or had a birth, before Texas, but Texas was like graduation for every single one. That\'s why we went for so long and allowed for so much perspective to sink into all the tunes. It\'s a fucking banger; I love that one.” **“Holyfields,”** Vernon: “The whole song is an improvised moment with barely any editing, and we just improv\'d moves. I sang some scratch vocals that day when we made it up, and they were weirdly close to what ended up being on the album. We didn\'t really chop away at that one—it kind of just was born with all its hair and everything.” **“Hey, Ma”** Vernon: “It just felt like a good strong song; we knew people would get it in their head. A couple of these tunes, and some of the tunes from the last album, I sort of peck around the studio with BJ Burton from time to time, and 90 percent of the stuff we make is death techno or something. So, there\'s another one that sort of just hung around with a stake in the ground, so to speak. And then our team—the three of us and the rest of everyone—just kept etching away at it, and it ended up becoming the song that felt emblematic of the record.” **\"U (Man Like)\"** Cook: “We had Bruce \[Hornsby\] come out to Justin\'s studio for a session for his *Absolute Zero* record. Bruce was playing a bunch of musical ideas that he had just sort of done at his house, and that piano figure in that song—I feel like we were tracking 15 seconds later. It was like, \'Wait, can we listen to this again?\'” Vernon: “I\'m not so good at coming up with full songs on the spot, but I can kind of map them out with my voice, or inflection. Then it takes a long time to chip away at them. Messina might have an idea for what that line should be, or Brad, or me. The melody that I sang that first day probably sounds remarkably like the melody that\'s on the album.” **“Naeem”** Vernon: “We did a collaboration with a dance group called TU Dance, and that was one of the songs. So we\'ve been performing \'Naeem\' as a part of this thing for a while. It\'s in a different state, but it\'s the finale of this big collaboration. And it just seemed very anthemic, and a very important part of whatever this record was going to be. It feels really nice to have a little bit more straightforward—not always bombastic, not always sonically trying to flip your lid or something.” **“Jelmore”** Vernon: “Basically an improvisation with me and this guy Buddy Ross. Again I probably didn\'t sing any final lyrics, but it\'s based on an improvisation, much like the song \'\_\_\_\_45\_\_\_\_\_\' from \[*22, A Million*\]. And when we were down outside El Paso, me and Chris were over on one part of this studio and Brad was with the band in a big studio across the property, and they sort of took \'Jelmore\' upon themselves and filled it in with all the lovely live-ness that\'s there. As the record goes on, it feels like there\'s a lot of these things that are sort of bare but have a lot of live energy to them.” **“Faith”** Vernon: “A basement improv that sat around for many years; maybe could have been on the last album, was for a while. I don\'t know, man—it\'s a song about having faith.” **“Marion”** Chris Messina: “I think that\'s one that Justin\'s been noodling around with for a while; for a few years, he would pick up that guitar and you would just kind of hear that riff. And we didn\'t really know what was going to happen to it. It\'s another one that exists in the TU Dance show. But what\'s cool about the version that\'s on the record is we did that as a live take with a six-piece ensemble that Rob Moose wrote for and conducted, and it was saxophone, trombone, trumpet, French horn, harmonica, and I think that\'s it that we did live. And then Justin was singing live and playing guitar live.” **“Salem”** Vernon: “OP-1 loop, weird Indigo Girls/Rickie Lee Jones vibes. I got really into acid and the Grateful Dead this year, so there\'s definitely some early psych vibes in there. The record really is supposed to be thought of as the fall record for this band, if you think of the other ones as seasons. Salem and burning leaves—these longings and these deaths, it\'s very much in there in that song, so it\'s a really autumn-y song.” **“Sh’Diah”** Vernon: “It stands for Shittiest Day in American History—the day after Trump got elected. It\'s another that sort of hung around as an improvised idea, and we finally got to figure out where we\'re going to land Mike Lewis, our favorite instrumentalist alive today in music. He gets to play over it, and the band got to do all this crazy layering over it. It\'s just one of my favorite moods on the album.” **“RABi”** Messina: “Justin\'s singing a cool thing on it, the guitar vibe is comforting and persistent, but we just weren\'t really sure where it needed to go. And then Brad and the rest of the dudes got their hands on it and it came back as just a dream sequence; it was so sick. We all kind of heard it and it was like, whoa, how can this not close out the record? This is definitely \'see you later.\'” Vernon: “Just some ‘life feels good now, don\'t it?\' There\'s a lot to be sad about, there\'s a lot to be confused about, there\'s a lot to be thankful for. And leaning on gratitude and appreciation of the people around you that make you who you are, make you feel safe, and provide that shelter so you can be who you want to be, there\'s still that impetus in life. We need that. It\'s a nice way to close the record, we all thought.”

Look past its futurist textures and careful obfuscations, and there’s something deeply human about FKA twigs’ 21st-century R&B. On her second full-length, the 31-year-old British singer-songwriter connects our current climate to that of Mary Magdalene, a healer whose close personal relationship with Christ brought her scorn from those who would ultimately write her story: men. “I\'m of a generation that was brought up without options in love,” she tells Apple Music. “I was told that as a woman, I should be looked after. It\'s not whether I choose somebody, but whether somebody chooses me.” Written and produced by twigs, with major contributions from Nicolas Jaar, *MAGDALENE* is a feminist meditation on the ways in which we relate to one another and ourselves—emotionally, sexually, universally—set to sounds that are at once modern and ancient. “Now it’s like, ‘Can you stand up in my holy terrain?’” she says, referencing the titular lyric from her mid-album collaboration with Future. “‘How are we going to be equals in this? Spiritually, am I growing? Do you make me want to be a better person?’ I’m definitely still figuring it out.” Here, she walks us through the album track by track. **thousand eyes** “All the songs I write are autobiographical. Anyone that\'s been in a relationship for a long time, you\'re meshed together. But unmeshing is painful, because you have the same friends or your families know each other. No matter who you are, the idea of leaving is not only a heart trauma, but it\'s also a social trauma, because all of a sudden, you don\'t all go to that pub that you went to together. The line \[\'If I walk out the door/A thousand eyes\'\] is a reference to that. At the time, I was listening to a lot of Gregorian music. I’d started really getting into medieval chords before that, and I\'d found some musicians that play medieval music and done a couple sessions with them. Even on \[2014\'s\] *LP1*, I had ‘Closer,’ which is essentially a hymn. I spent a lot of time in choir as a child and I went to Sunday school, so it’s part of who I am at this stage.” **home with you** “I find things like that interesting in the studio, just to play around and bring together two completely different genres—like Elton John chords and a hip-hop riff. That’s what ‘home with you’ was for me: It’s a ballad and it\'s sad, but then it\'s a bop as well, even though it doesn\'t quite ever give you what you need. It’s about feeling pulled in all directions: as a daughter, or as a friend, or as a girlfriend, or as a lover. Everyone wanting a piece of you, but not expressing it properly, so you feel like you\'re not meeting the mark.” **sad day** “It’s like, ‘Will you take another chance with me? Can we escape the mundane? Can we escape the cyclical motion of life and be in love together and try something that\'s dangerous and exhilarating? Yeah, I know I’ve made you sad before, but will you give me another chance?\' I wrote this song with benny blanco and Koreless. I love to set myself challenges, and it was really exciting to me, the challenge of retaining my sound while working with a really broad group of people. I was lucky working with Benny, in the fact that he creates an environment where, as an artist, you feel really comfortable to be yourself. To me, that\'s almost the old-school definition of a producer: They don\'t have to be all up in your grill, telling you what to do. They just need to lay a really beautiful, fertile soil, so that you can grow to be the best you in the moment.” **holy terrain** “I’m saying that I want to find a man that can stand up next to me, in all of my brilliance, and not feel intimidated. To me, Future’s saying, ‘Hey, I fucked up. I filled you with poison. I’ve done things to make you jealous. Can you heal me? Can you tell me how to be a better man? I need the guidance, of a woman, to show me how to do that.’ I don\'t think that there are many rappers that can go there, and just put their cards on the table like that. I didn\'t know 100%, once I met Future, that it would be right. But we spoke on the phone and I played him the album and I told him what it was about: ‘It’s a very female-positive, femme-positive record.’ And he was just like, ‘Yeah. Say no more. I\'ve got this.’ And he did. He crushed it. To have somebody who\'s got patriarchal energy come through and say that, wanting to stand up and be there for a woman, wanting to have a woman that\'s an equal—that\'s real.” **mary magdalene** “Let’s just imagine for one second: Say Jesus and Mary Magdalene are really close, they\'re together all the time. She\'s his right-hand woman, she’s his confidante, she\'s healing people with him and a mystic in her own right. So, at that point, any man and woman that are spending that much time together, they\'re likely to be what? Lovers. Okay, cool. So, if Mary had Jesus\' children, that basically debunks the whole of history. Now, I\'m not saying that happened. What I\'m saying is that the idea of people thinking that might happen is potentially really dangerous. It’s easier to call her a whore, because as soon as you call a woman a whore, it devalues her. I see her as Jesus Christ\'s equal. She’s a male projection and, I think, the beginning of the patriarchy taking control of the narrative of women. Any woman that\'s done anything can be subject to that; I’ve been subject to that. It felt like an apt time to be talking about it.” **fallen alien** “When you\'re with someone, and they\'re sleeping, and you look at them, and you just think, \'No.\' For me, it’s that line, \[\'When the lights are on, I know you/When you fall asleep, I’ll kick you down/By the way you fell, I know you/Now you’re on your knees\'\]. You\'re just so sick of somebody\'s bullshit, you\'re just taking it all day, and then you\'re in bed next to them, and you\'re just like, ‘I can\'t take this anymore.’” **mirrored heart** “People always say, ‘Whoever you\'re with, they should be a reflection of yourself.’ So, if you\'re looking at someone and you think, ‘You\'re a shitbag,’ then you have to think about why it was that person, at that time, and what\'s connecting you both. What is the reflection? For others that have found a love that is a true reflection of themselves, they just remind me that I don\'t have that, a mirrored heart.” **daybed** “Have you ever forgotten how to spell a really simple word? To me, depression\'s a bit like that: Everything\'s quite abstract, and even slightly dizzy, but not in a happy way. It\'s like a very slow circus. Suddenly the fruit flies seem friendly, everything in the room just starts having a different meaning and you even have a different relationship with the way the sofa cushions smell. \[Masturbation\] is something to raise your endorphins, isn\'t it? It’s either that or try and go to the gym, or try and eat something good. You almost can\'t put it into words, but we\'ve all been there. I sing, \'Active are my fingers/Faux, my cunnilingus\': You\'re imagining someone going down on you, but they\'re actually not. You open your eyes, and you\'re just there, still on your sofa, still watching daytime TV.” **cellophane** “It\'s just raw, isn\'t it? It didn\'t need a thing. The vocal take that\'s on the record is the demo take. I had a Lyft arrive outside the studio and I’d just started playing the piano chords. I was like, ‘Hey, can you just give me like 20, 25 minutes?’ And I recorded it as is. I remember feeling like I wanted to cry, but I just didn\'t feel like it was that suitable to cry at a studio session. I often want everything to be really intricate and gilded, and I want to chip away at everything, and sculpt it, and mold it, and add layers. The thing I\'ve learned on *MAGDALENE* is that you don\'t need to do that all the time, and just because you can do something, it doesn\'t mean you should. That\'s been a real growing experience for me—as a musician, as a producer, as a singer, even as a dancer. Something in its most simple form is beautiful.”

Album page: www.paradiseofbachelors.com/pob-042 Artist page: www.paradiseofbachelors.com/jake-xerxes-fussell Other online purchasing options (physical/download/streaming): smarturl.it/PoB42 ALBUM NARRATIVE On his third and most finely wrought album yet, guitarist, singer, and master interpreter Fussell is joined for the first time by a full band featuring Nathan Bowles (drums), Casey Toll (bass), Nathan Golub (pedal steel), Libby Rodenbough (violin, vocals), and James Anthony Wallace (piano, organ). An utterly transporting selection of traditional narrative folksongs addressing the troubles and delights of love, work, and wine (i.e., the things that matter), collected from a myriad of obscure sources and deftly metamorphosed, Out of Sight contains, among other moving curiosities, a fishmonger’s cry that sounds like an astral lament (“The River St. Johns”); a cotton mill tune that humorously explores the unknown terrain of death and memory (“Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues”); and a fishermen’s shanty/gospel song equally concerned with terrestrial boozing and heavenly transcendence (“Drinking of the Wine”). Jake has written a fascinating essay—below, followed by some words by Will Oldham aka Bonnie "Prince" Billy—about the nine songs he chose and his journey to them (longer version available upon request). * Like all things having to do with traditional music, there are multiple sources for these songs, many layers of transmission and interpretation. “Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues” I heard from my friend Art Rosenbaum, who learned it from a Pete Seeger recording from the late ’40s. Seeger had picked it up from an older source, an unattributed singer at an industrial school for women in western North Carolina. I like thinking of the song as a sort of resistance piece sung created by overworked and underpaid textile workers, which it is, but I also love the sardonic humor and imagery: an inscrutable floor manager who’d “take the nickels off a dead man’s eyes / To buy Coca-Colas and Eskimo Pies.” I first heard the Irish tragicomedy “Michael Was Hearty” via my pal Nathan Salsburg, guitar wizard and curator of the Alan Lomax Archive, who played me a YouTube video of an Irish Traveller and ballad singer named Thomas McCarthy, whose a cappella delivery of the song is striking and singular. I immediately wanted to commit the words to memory, but I had to come up with another way to perform it that worked for my way of singing, so I worked out a waltz arrangement on my guitar and taught it to my band. Some great imagery in there too: “High was the step in the jig that he sprung / He had good looks and soothering tongue”—don’t we all know somebody like that? This one dates to probably sometime around the end of the 1800s. “Oh Captain” is my bastardized reinterpretation of a beautiful deckhand’s song recorded by the singer, composer, and musicologist Willis Laurence James for Paramount Records in the early 1920s, with piano accompaniment. It’s a very unusual recording. James spent much of his life collecting and interpreting and writing about African American worksongs, yet few have recognized his short, obscure stint as a recording artist. Turns out he was a trained singer who taught in the music department for years at Spelman College, whose library still holds his archive. I became fascinated with him and his work, so this song is my little homage to Dr. James. In the mid-2000s when I was living in Oxford, Mississippi, I went to an estate sale at an antebellum house in town and found a first edition of Carl Sandburg’s famous 1927 book The American Songbag, which contains “Three Ravens.” Inside was an index card with a charming calligraphed “If found, please return to,” written by the banjo player and singer John Hartford, along with his Tennessee address. I’d been listening a lot to the music of Ruth Crawford Seeger, a member of the Seeger family of folk music fame, but also an important and influential avant-garde composer. Her music resides in that interesting place where modern abstract forms and traditional abstract forms collide. Her collection 19 American Folk Songs for Piano includes a wonderful minute-long version of “Three Ravens.” I couldn’t get enough of it, so I went back to my Hartford copy of the Sandburg book (from whom Seeger herself got the tune) and learned it. The great ballad singer and collector Bobby McMillon, of western North Carolina, has recorded a fine version of “The Rainbow Willow” under the title “Locks and Bolts,” the more common title. My friends Sally Anne Morgan and Sarah Louise (aka House and Land) have also recorded a beautiful rendering. I combined various versions from the Ozarks into the one that I sing, but the story is pretty much the same. Murder is so commonplace in old songs that I don’t know if the term “murder ballad” is very useful. Maybe we should be breaking it down to which type of murder, and what was the motive, and what sort of weapon was used, things like that. I’d say this is more of a love song than a death song, anyway. “The River St. Johns” comes straight from one of Stetson Kennedy’s Florida WPA recordings of a gentleman named Harden Stuckey doing his interpretation of a fishmonger’s cry, which he recalls from a childhood memory. What compelling imagery there: “I’ve got fresh fish this morning, ladies / They are gilded with gold, and you may find a diamond in their mouths.” I can’t help but believe him. “Jubilee” is from the great Jean Ritchie’s family tradition. Her father probably sang it as more of a play-party type piece, or at least that’s what Art Rosenbaum tells me, but it’s taken on different forms since. I’m not sure where I first heard it, but it’s been making the rounds in old-time music circles for decades now, and I’ve always appreciated its basic insight: “Swing and turn, live and learn.” “Drinking of the Wine” is a spiritual number, you might could say. The version to which I’m most faithful is one that was recorded by a group of Virginia menhaden fishermen singing it as a net-hauling shanty on a boat off the coast of New Jersey in the early 1950s. Clara Ward also recorded it, as have many gospel singers, as well as the great North Carolina banjo player and folk music promoter Bascom Lamar Lunsford. “16–20” is my very loose rearrangement of a tune that I’ve known for years. This was a popular dance piece among guitarists in the lower Chattahoochee River Valley of Georgia and Alabama, including my old friends George Daniel and Robert Thomas, from whom I learned it. I can’t say that this current working of it bears much resemblance to their “16–20,” which was more of an upbeat buckdancer’s choice, but it’s always evolving for me, which is good because it’s one that I will never stop playing. – Jake Xerxes Fussell, Durham, NC, 2019 * "In our house we’ve listened to more Jake Fussell than any other individual artist over the past year, with the possible exception of Laurie Spiegel. We’ve had the opportunity to witness several intimate performances of Fussell’s (to my mind, he creates a new standard for the value of up-close musical experience) here in Louisville. As long as Jake Fussell is making records and playing shows, there is ample cause for optimism in this world. "Fussell’s repertoire, and the manner in which he creates, constructs and presents it, displays such a beautiful and complex relationship to time and currency. He’s able to listen to and understand the presence of an old recording, of crusty dusty written-out pieces of music and memories of musical encounters. And then he overlays his own now-ness on those pre-existing presences so that the lives of older musical forces, in effect, link arms with Fussell’s in-progress trajectory and skip down the brick road, picking up desperate and willing compatriots along the way. Meaning: Jake lives in music as a true time-artist, using the qualities of time itself as irreplaceable elements of content. "When Jake sings a sad song, he presents it in such a way that makes me want to say “Hey, but everything’s okay because you’re Jake Xerxes Fussell!” Hopefully it’s okay by him that I wouldn’t accept full-fledged nihilism from him even if he were standing naked on the ledge of a tall building with “this World is Shit” written on his shaved chest in, well, shit. His deal with his songs is too strong and blatantly valuable." – Bonnie “Prince” Billy * + Fussell’s third and most finely wrought album yet is also his first recorded with a full band (featuring Nathan Bowles) + Deluxe LP edition features 150g virgin vinyl; heavy-duty reverse board matte jacket with notes on song sources; color LP labels; and high-res Bandcamp download code.CD edition features gatefold reverse board matte jacket with LP replica art and notes. + RIYL: Michael Hurley, Bob Dylan, John Prine, Townes Van Zandt, Ry Cooder, Dave Van Ronk, Jim Dickinson, Raccoon Records, Bonnie “Prince” Billy, Nathan Bowles, Nathan Salsburg, William Tyler, Daniel + Artist page/tour dates/back catalog: www.paradiseofbachelors.com/jake-xerxes-fussell

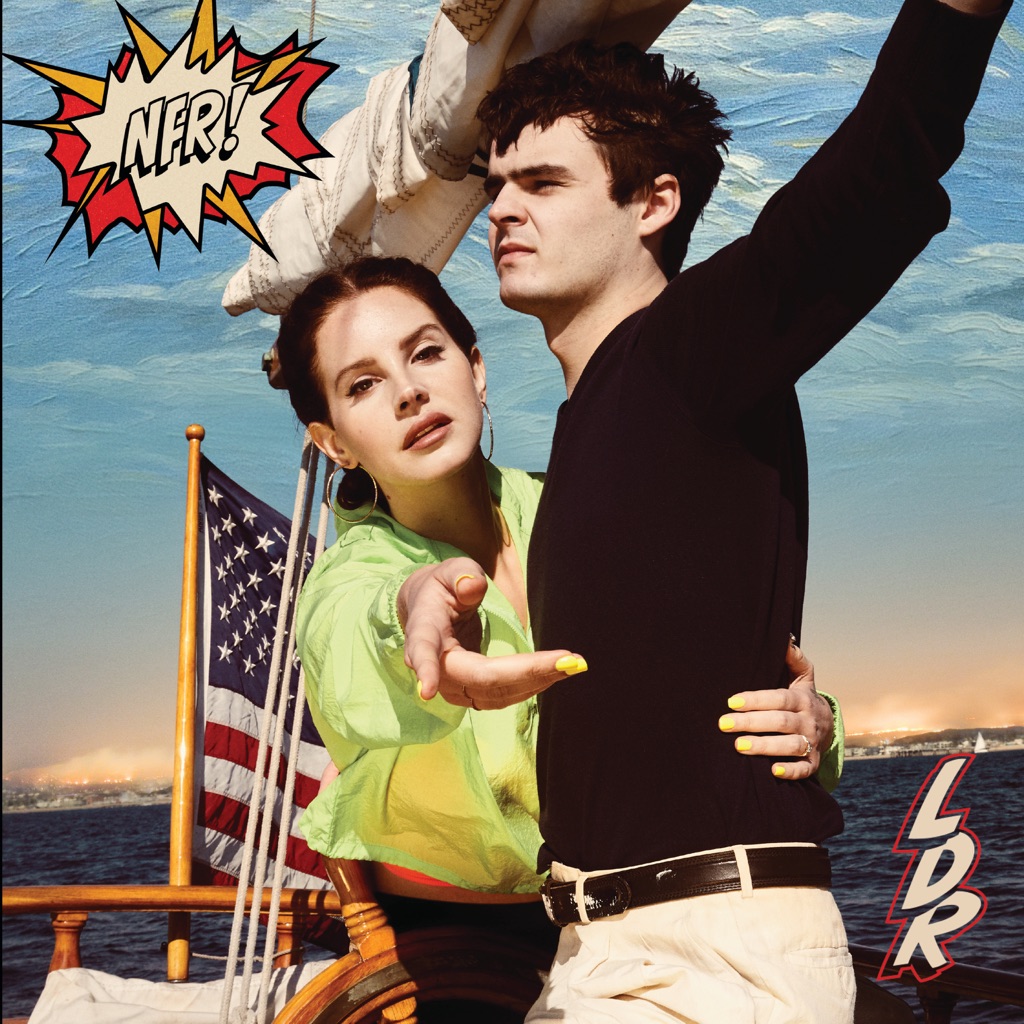

Part of the fun of listening to Lana Del Rey’s ethereal lullabies is the sly sense of humor that brings them back down to earth. Tucked inside her dreamscapes about Hollywood and the Hamptons are reminders—and celebrations—of just how empty these places can be. Here, on her sixth album, she fixes her gaze on another place primed for exploration: the art world. Winking and vivid, *Norman F\*\*\*\*\*g Rockwell!* is a conceptual riff on the rules that govern integrity and authenticity from an artist who has made a career out of breaking them. In a 2018 interview with Apple Music\'s Zane Lowe, Del Rey said working with songwriter Jack Antonoff (who produced the album along with Rick Nowels and Andrew Watt) put her in a lighter mood: “He was so *funny*,” she said. Their partnership—as seen on the title track, a study of inflated egos—allowed her to take her subjects less seriously. \"It\'s about this guy who is such a genius artist, but he thinks he’s the shit and he knows it,” she said. \"So often I end up with these creative types. They just go on and on about themselves and I\'m like, \'Yeah, yeah.\' But there’s merit to it also—they are so good.” This paradox becomes a theme on *Rockwell*, a canvas upon which she paints with sincerity and satire and challenges you to spot the difference. (On “The Next Best American Record,” she sings, “We were so obsessed with writing the next best American record/’Cause we were just that good/It was just that good.”) Whether she’s wistfully nostalgic or jaded and detached is up for interpretation—really, everything is. The album’s finale, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have - but I have it,” is packaged like a confessional—first-person, reflective, sung over simple piano chords—but it’s also flamboyantly cinematic, interweaving references to Sylvia Plath and Slim Aarons with anecdotes from Del Rey\'s own life to make us question, again, what\'s real. When she repeats the phrase “a woman like me,” it feels like a taunt; she’s spent the last decade mixing personas—outcast and pop idol, debutante and witch, pinup girl and poet, sinner and saint—ostensibly in an effort to render them all moot. Here, she suggests something even bolder: that the only thing more dangerous than a complicated woman is one who refuses to give up.

Maggie Rogers spent the first three years of her career retracing one chance encounter: In 2016, a video of her singing a song that moved Pharrell to tears during a master class at NYU went viral, earning her a record deal, magazine features, and headlining tours (watch it and you’ll understand). But the Maryland native, then 22, was still figuring out who she was, and this sudden flood of fame was a lot to bear. Determined to take control of her own narrative, she assembled a debut album powerful enough to shift the conversation. Measured, subtle, and wise beyond her years, it feels like the introduction she always wanted to make. Like her 2017 EP, *Now That the Light Is Fading*, *Heard It In A Past Life* is a thoughtfully sewn patchwork of anthemic synth-pop, brooding acoustic folk, and soft-lit electronica, the latter of which was inspired by a year spent dancing through Berlin’s nightclub scene. But here, her vision feels both more daring and more polished. On “Retrograde,” long stretches of propulsive synths are punctuated by high-pitched *hah-hah-hah*s; “Say It” blends R&B with light, breathy indie-pop; and “The Knife” could be a sultry come-on or a daring confession. On the Greg Kurstin-produced “Light On,” Rogers seems to make peace with her surreal story. “And I am findin’ out/There’s just no other way/And I’m still dancin’ at the end of the day,” she sings, a bittersweet hat-tip to the moment that got her here. And to her fans, a promise: “If you leave the light on/Then I’ll leave the light on.”

Mdou Moctar immediately stands out as one of the most innovative artists in contemporary Saharan music. His unconventional interpretations of Tuareg guitar and have pushed him to the forefront of a crowded scene. Back home, he's celebrated for his original compositions and verbose poetry, an original creator in a genre defined by cover bands. In the exterior, where Saharan rock has become one of the continents biggest musical exports, he's earned a name for himself with his guitar moves. Mdou shreds with a relentless and frenetic energy that puts his contemporaries to shame. Mdou Moctar hails from a small village in central Niger in a remote region steeped in religious tradition. Growing up in an area where secular music was all but prohibited, he taught himself to play on a homemade guitar cobbled together out of wood. It was years before he found a “real” guitar and taught himself to play in secret. His immediately became a star amongst the village youth. In a surprising turn, his songs began to win over local religious leaders with their lyrics of respect, honor, and tradition. In 2008, Mdou traveled to Nigeria to record his debut album of spacey autotune, drum machine, and synthesizer. The album became a viral hit on the mp3 networks of West Africa, and was later released on the compilation “Music from Saharan Cellphones.” In 2013, he released “Afelan,” compiled from field recordings of his performances recorded in his village. Then he shifted gears, producing and starring the first Tuareg language film, a remake of Prince's Purple Rain (“Rain the Color Blue with a Little Red in it”). Finally, in 2017, he created a solo folk album, “Sousoume Tamachek,” a mellow blissed out recording evoking the calm desert soundscape. Without a band present, he played every instrument on the record. "I am a very curious person and I want to push Tuareg music far,” he says. A long time coming, “Ilana” is Mdou's first true studio album with a live band. Recorded in Detroit at the tail end of a US tour by engineer Chris Koltay (the two met after bonding over ZZ Top's “Tres Hombres”), the band lived in the studio for a week, playing into the early hours. Mdou was accompanied by an all-star band: Ahmoudou Madassane's (Les Filles de Illighadad) lighting fast rhythm guitar, Aboubacar Mazawadje's machine gun drums, and Michael Coltun's structured low-end bass. The album was driven by lots of spontaneity – Mdou's preferred method of creation – jumping into action whenever inspiration struck. The resulting tracks were brought back to Niger to add final production: additional guitar solos, overdubs of traditional percussion, and a general ambiance of Agadez wedding vibes. The result is Mdou's most ambitious record to date. “Ilana” takes the tradition laid out by the founders into hyperdrive, pushing Tuareg guitar into an ever louder and blistering direction. In contrast to the polished style of the typical “world music” fare, Mdou trades in unrelenting grit and has no qualms about going full shred. From the spaghetti western licks of “Tarhatazed,” the raw wedding burner “Ilana,” to the atmospheric Julie Cruise-ish ballad "Tumastin,” Mdou's new album seems at home amongst some of the great seminal Western records. But Mdou disagrees with the classification. Mdou grew up listening to the Tuareg guitar greats, and it was only in the past few years on tour that he was introduced to the genre. "I don't know what rock is exactly, I have no idea,” he says, I only know how to play in my style." For Mdou, this style is to draw on both modern and traditional sources and combine elements into new forms. In “Ilana” Mdou reaches back into Tuareg folklore for inspiration, riffing on the hypnotic loops of takamba griots, or borrowing vocal patterns from polyphonic nomad songs, and combining them with his signature guitar. You can hear the effect in tracks like “Kamane Tarhanin,” where a call and response lyric lifts up over a traditional vocal hum before breaking into a wailing solo with tapping techniques learned from watching Youtube videos of Eddie Van Halen. There is an urgency in Mdou's music, and the fury of the tracks are matched by their poignant messages. The title track “Ilana” is a commentary on uranium exploitation by France in Niger: “Our benefits are only dust / And our heritage is taken by the people of France / occupying the valley of our ancestors.” Other times, he delves into the complexities of love, but always with delicate poetics: “Oh my love, think of my look when I walked toward the evening / Tears fell from my face, from the tears that fell green trees grew / And love rested in the shade.” As Mdou travels the world, he divides his time between two places, alternating from lavish weddings in Agadez to sold out concerts in Berlin nightclubs. It offers a unique perspective, but also means that he needs to address different audiences. At home, his compositions send a message to his people. Abroad, his music is an opportunity to be heard and represent his people on a world stage. For the cover art, Mdou conceptualized a Saharan bird flying over the desert. “This bird is my symbol because he resembles my artistic look. I wear a turban in two colors. The jewelry in its beak is the symbol of Agadez.” It's a poignant idea, as the bird flies off over the desert, it carries its home wherever it goes. It's not so different than what Mdou hopes he can do with his music. "I'm just an ambassador, like a messenger of music, telling what is happening in my world.” “Ilana” is an invitation to listen, at a time when a message could not be needed more.

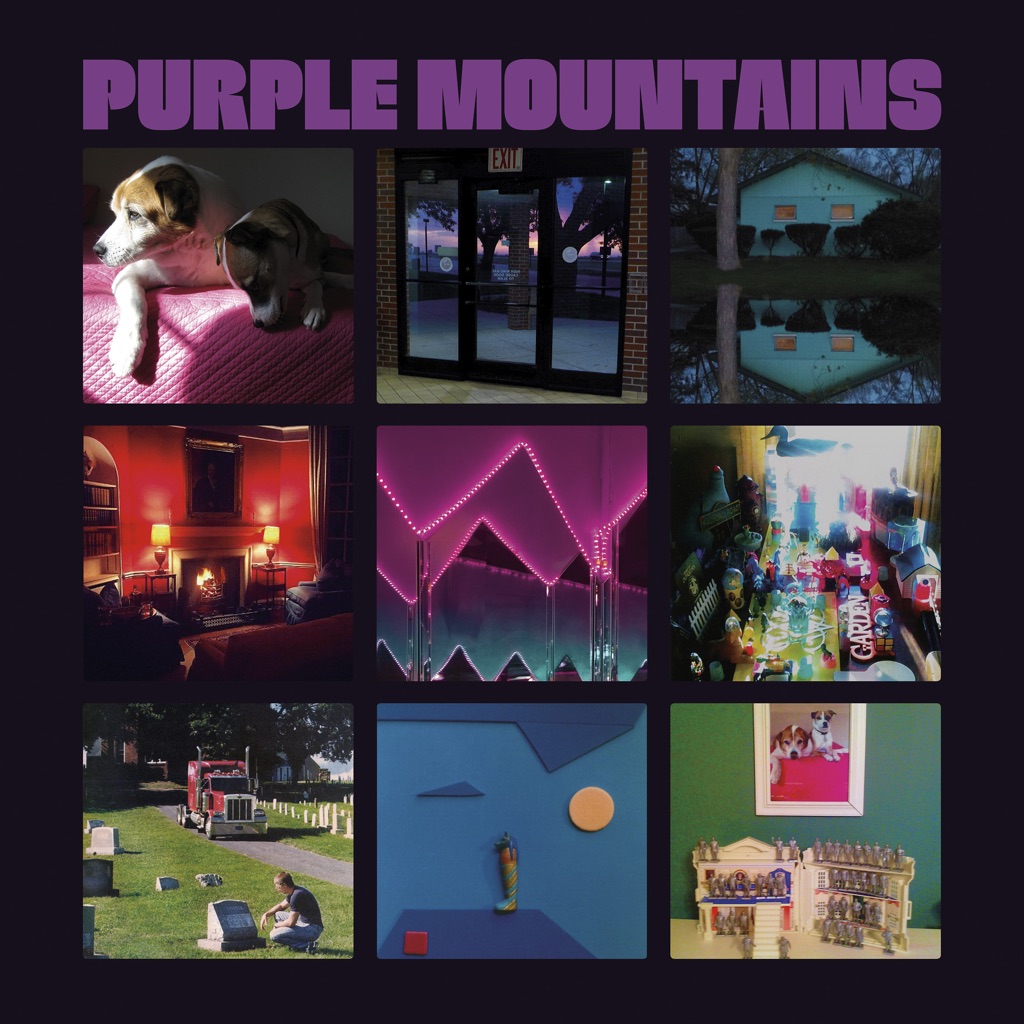

When David Berman disbanded Silver Jews in 2009, the world stood to lose one of the best writers in indie rock, a guy who catalogued the magic and misery of everyday life with wit, heart, and the ragged glory of the occupationally down-and-out. After a 10-year break professedly spent reading books and arguing with people on Reddit, Berman enlisted members of the Brooklyn band Woods to back him on *Purple Mountains*. Berman’s pain had never been laid quite so bare, nor had it ever sounded quite so urgent. “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion,” he sings on the swaggering “That’s Just the Way I Feel.” “Day to day, I’m neck and neck with giving in.” And “Margaritas at the Mall” turns an ordinary happy hour into a jeremiad about the cold comforts of capitalism in a godless world. That the music—country-tinged indie rock—was as polished and competent as it was only highlighted Berman’s intensity: less a rock singer than a street preacher, someone who needed to avail himself of his visions stat. But even at his most desperate, he remained achingly funny, turning statements of existential loneliness into the kind of bumper sticker Zen that made him seem like an ordinary guy no matter how highfalutin he could get. “Well, if no one’s fond of fuckin’ me, maybe no one’s fuckin’ fond of me,” he sings on the album-closing “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” sounding not all that far off from the George Strait one-twos he reportedly loved. Above all, though, his writing is beautiful, attuned to detail in ways that make ordinary scenarios shimmer with quiet magic. Just listen to “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan,” which turns a quiet night in a big city into an allegory of finding solace in the weather of what comes to us. Shortly after the release of *Purple Mountains*, Berman died, at the age of 52, a tragic end to what felt like a triumphant return. “The dead know what they\'re doing when they leave this world behind,” he sings on “Nights That Won’t Happen.” “When the here and the hereafter momentarily align.”

David Berman comes in from the cold after ten long years. His new musical expression is a meltdown unparalleled in modern memory. He warns us that his findings might be candid, but as long as his punishment comes in such bite-sized delights of all-American jukebox fare, we'll hike the Purple Mountains with pleasure forever.

On her fifth proper full-length album, Sharon Van Etten pushes beyond vocals-and-guitar indie rock and dives headlong into spooky maximalism. With production help from John Congleton (St. Vincent), she layers haunting drones with heavy, percussive textures, giving songs like “Comeback Kid” and “Seventeen” explosive urgency. Drawing from Nick Cave, Lucinda Williams, and fellow New Jersey native Bruce Springsteen, *Remind Me Tomorrow* is full of electrifying anthems, with Van Etten voicing confessions of reckless, lost, and sentimental characters. The album challenges the popular image of Van Etten as *just* a singer-songwriter and illuminates her significant talent as composer and producer, as an artist making records that feel like a world of their own.

“How people may emotionally connect with music I’ve been involved in is something that part of me is completely mystified by,” Thom Yorke tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “Human beings are really different, so why would it be that what I do connects in that way? I discovered maybe around \[Radiohead\'s album\] *The Bends* that the bit I didn’t want to show, the vulnerable bit… that bit was the bit that mattered.” *ANIMA*, Yorke’s third solo album, further weaponizes that discovery. Obsessed by anxiety and dystopia, it might be the most disarmingly personal music of a career not short of anxiety and dystopia. “Dawn Chorus” feels like the centerpiece: It\'s stop-you-in-your-tracks beautiful with a claustrophobic “stream of consciousness” lyric that feels something like a slowly descending panic attack. And, as Yorke describes, it was the record\'s biggest challenge. “There’s a hit I have to get out of it,” he says. “I was trying to develop how ‘Dawn Chorus’ was going to work, and find the right combinations on the synthesizers I was using. Couldn’t find it, tried it again and again and again. But I knew when I found it I would have my way into the song. Things like that matter to me—they are sort of obsessive, but there is an emotional connection. I was deliberately trying to find something as cold as possible to go with it, like I sing essentially one note all the way through.” Yorke and longtime collaborator Nigel Godrich (“I think most artists, if they\'re honest, are never solo artists,” Yorke says) continue to transfuse raw feeling into the album’s chilling electronica. “Traffic,” with its jagged beats and “I can’t breathe” refrain, feels like a partner track to another memorable Yorke album opener, “Everything in Its Right Place.” The extraordinary “Not the News,” meanwhile, slaloms through bleeps and baleful strings to reach a thunderous final destination. It’s the work of a modern icon still engaged with his unique gift. “My cliché thing I always say is, \'You know you\'re in trouble when people stop listening to sad music,\'” Yorke says. “Because the moment people stop listening to sad music, they don\'t want to know anymore. They\'re turning themselves off.”