Rough Trade's Albums of the Year 2020

Buy and pre-order vinyl records, books + merchandise online from Rough Trade, independent purveyors of great music, since 1976.

Source

Midwestern by birth and temperament, Freddie Gibbs has always seemed a little wary of talking himself up—he’s more show than tell. But between 2019’s Madlib collaboration (*Bandana*) and the Alchemist-led *Alfredo*, what wasn’t clear 10 years ago is crystal now: Gibbs is in his own class. The wild, shape-shifting flow of “God Is Perfect,” the chilling lament of “Skinny Suge” (“Man, my uncle died off a overdose/And the fucked-up part of that is I know I supplied the n\*\*\*a that sold it”), a mind that flickers with street violence and half-remembered Arabic, and beats that don’t bang so much as twinkle, glide, and go up like smoke. *Alfredo* is seamless, seductive, but effortless, the work of two guys who don’t run to catch planes. On “Something to Rap About,” Gibbs claims, “God made me sell crack so I had something to rap about.” But the way he flows now, you get the sense he would’ve found his way to the mic one way or the other.

www.muddguts.shop/products/habibi-anywhere-but-here-lp-presale

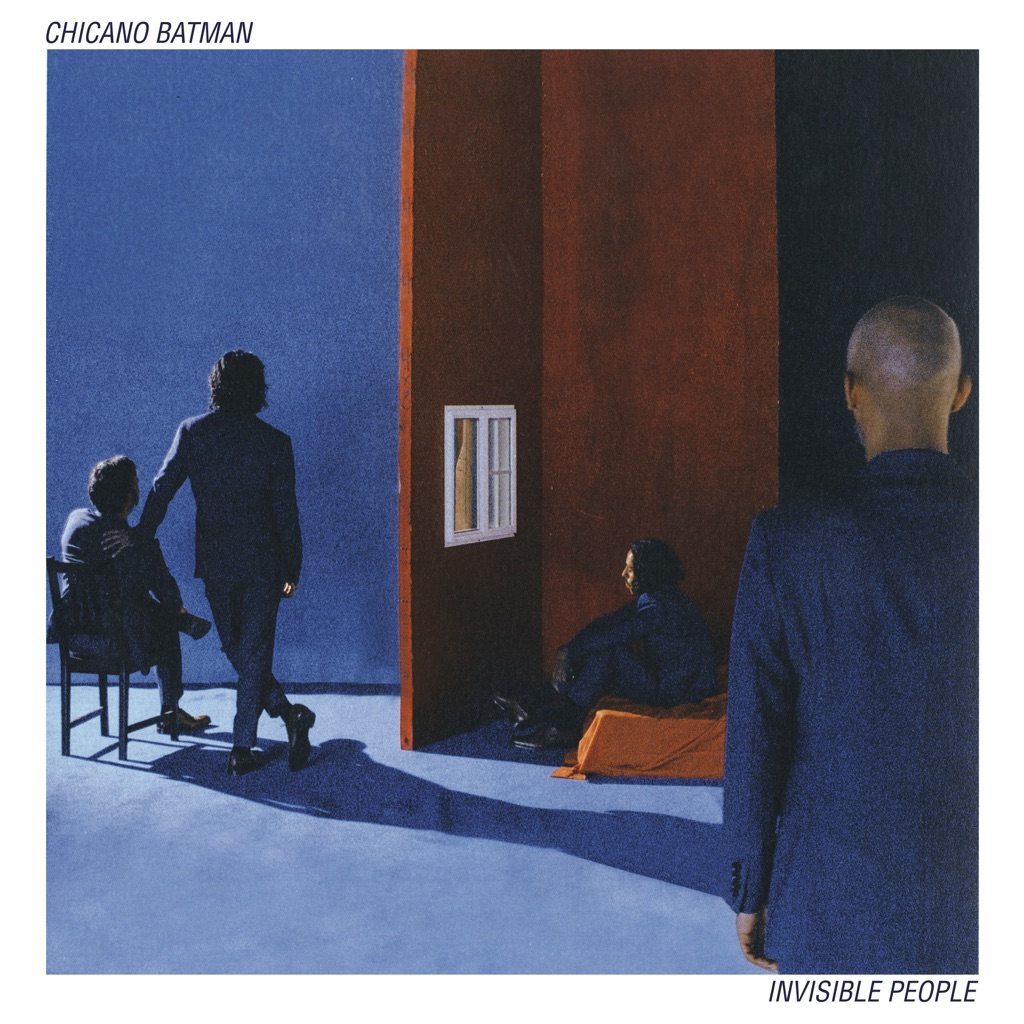

Los Angeles psych-soul four-piece Chicano Batman announce Invisible People, out May 1st via ATO Records. The album is both the band’s most sonically-varied and cohesive. It is a statement of hope, a proclamation that we are all invisible people, and that despite race, class, or gender we can overcome our differences and stand together. For the album, Chicano Batman worked with Shawn Everett, the GRAMMY-award winning mixing engineer known for his work with Alabama Shakes, War on Drugs and Julian Casablancas. With Leon Michels’ producing and Everett’s mixing steering the record’s direction, the band’s lush Tropicalia-tinged sound has transformed into their most polished and densely layered. Invisible People is an illuminating and encapsulating sonic landscape, one that hasn’t lost the essence that put Chicano Batman on the map.

Stephen Bruner’s fourth album as Thundercat is shrouded in loss—of love, of control, of his friend Mac Miller, who Bruner exchanged I-love-yous with over the phone hours before Miller’s overdose in late 2018. Not that he’s wallowing. Like 2017’s *Drunk*—an album that helped transform the bassist/singer-songwriter from jazz-fusion weirdo into one of the vanguard voices in 21st-century black music—*It Is What It Is* is governed by an almost cosmic sense of humor, juxtaposing sophisticated Afro-jazz (“Innerstellar Love”) with deadpan R&B (“I may be covered in cat hair/But I still smell good/Baby, let me know, how do I look in my durag?”), abstractions about mortality (“Existential Dread”) with chiptune-style punk about how much he loves his friend Louis Cole. “Yeah, it’s been an interesting last couple of years,” he tells Apple Music with a sigh. “But there’s always room to be stupid.” What emerges from the whiplash is a sense that—as the title suggests—no matter how much we tend to label things as good or bad, happy or sad, the only thing they are is what they are. (That Bruner keeps good company probably helps: Like on *Drunk*, the guest list here is formidable, ranging from LA polymaths like Miguel Atwood-Ferguson, Louis Cole, and coproducer Flying Lotus to Childish Gambino, Ty Dolla $ign, and former Slave singer Steve Arrington.) As for lessons learned, Bruner is Zen as he runs through each of the album’s tracks. “It’s just part of it,” he says. “It’s part of the story. That’s why the name of the album is what it is—\[Mac’s death\] made me put my life in perspective. I’m happy I’m still here.” **Lost in Space / Great Scott / 22-26** \"Me and \[keyboardist\] Scott Kinsey were just playing around a bit. I like the idea of something subtle for the intro—you know, introducing somebody to something. Giving people the sense that there’s a ride about to happen.\" **Innerstellar Love** \"So you go from being lost in space and then suddenly thrust into purpose. The feel is a bit of an homage to where I’ve come from with Kamasi \[Washington, who plays the saxophone\] and my brother \[drummer Ronald Bruner, Jr.\]: very jazz, very black—very interstellar.\" **I Love Louis Cole (feat. Louis Cole)** \"It’s quite simply stated: Louis Cole is, hands down, one of my favorite musicians. Not just as a performer, but as a songwriter and arranger. \[*Cole is a polymathic solo artist and multi-instrumentalist, as well as a member of the group KNOWER.*\] The last time we got to work together was on \[*Drunk*’s\] \'Bus in These Streets.\' He inspires me. He reminds me to keep doing better. I’m very grateful I get to hang out with a guy like Louis Cole. You know, just me punching a friend of his and falling asleep in his laundry basket.\" **Black Qualls (feat. Steve Lacy, Steve Arrington & Childish Gambino)** \"Steve Lacy titled this song. \'Qualls\' was just a different way of saying ‘walls.\' And black walls in the sense of what it means to be a young black male in America right now. A long time ago, black people weren’t even allowed to read. If you were caught reading, you’d get killed in front of your family. So growing up being black—we’re talking about a couple hundred years later—you learn to hide your wealth and knowledge. You put up these barriers, you protect yourself. It’s a reason you don’t necessarily feel okay—this baggage. It’s something to unlearn, at least in my opinion. But it also goes beyond just being black. It’s a people thing. There’s a lot of fearmongering out there. And it’s worse because of the internet. You gotta know who you are. It’s about this idea that it’s okay to be okay.\" **Miguel’s Happy Dance** \"Miguel Atwood-Ferguson plays keys on this record, and also worked on the string arrangement. Again, y’know, without getting too heavily into stuff, I had a rough couple of years. So you get Miguel’s happy dance.\" **How Sway** \"I like making music that’s a bit fast and challenging to play. So really, this is just that part of it—it’s like a little exercise.\" **Funny Thing** \"The love songs here are pretty self-explanatory. But I figure you’ve gotta be able to find the humor in stuff. You’ve gotta be able to laugh.\" **Overseas (feat. Zack Fox)** \"Brazil is the one place in the world I would move. São Paulo. I would just drink orange juice all day and play bass until I had nubs for fingers. So that’s number one. But man, you’ve also got Japan in there. Japan. And Russia! I mean, everything we know about the politics—it is what it is. But Russian people are awesome. They’re pretty crazy. But they’re awesome.\" **Dragonball Durag** \"The durag is the ultimate power move. Not like a superpower, but just—you know, it translates into the world. You’ve got people with durags, and you’ve got people without them. Personally, I always carry one. Man, you ever see that picture of David Beckham wearing a durag and shaking Prince Charles’ hand? Victoria’s looking like she wants to rip his pants off.\" **How I Feel** \"A song like \'How I Feel’—there’s not a lot of hidden meaning there \[*laughs*\]. It’s not like something really bad happened to me when I was watching *Care Bears* when I was six and I’m trying to cover it up in a song. But I did watch *Care Bears*.\" **King of the Hill** \"This is something I made with BADBADNOTGOOD. It came out a little while ago, on the Brainfeeder 10-year compilation. We kind of wrestled with whether or not it should go on the album, but in the end it felt right. You’re always trying to find space and time to collaborate with people, but you’re in one city, they’re in another, you’re moving around. Here, we finally got the opportunity to be in the same room together and we jumped at it. I try and be open to all kinds of collaboration, though. Magic is magic.\" **Unrequited Love** \"You know how relationships go: Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose \[*laughs*\]. But really, it’s not funny \[*more laughs*\]. Sometimes you—\[*laughing*\]—you get your heart broken.\" **Fair Chance (feat. Ty Dolla $ign & Lil B)** \"Me and Ty spend a lot of time together. Lil B was more of a reach, but we wanted to find a way to make it work, because some people, you know, you just resonate with. This is definitely the beginning of more between him and I. A starting point. But you know, to be honest it’s an unfortunate set of circumstances under which it comes. We were all very close to Mac \[Miller\]. It was a moment for all of us. We all became very aware of that closeness in that moment.\" **Existential Dread** \"You know, getting older \[*laughs*\].\" **It Is What It Is** \"That’s me in the middle, saying, ‘Hey, Mac.’ That’s me, getting a chance to say goodbye to my friend.\"

GRAMMYs 2021 Winner - Best Progressive R&B Album Thundercat has released his new album “It Is What It Is” on Brainfeeder Records. The album, produced by Flying Lotus and Thundercat, features musical contributions from Ty Dolla $ign, Childish Gambino, Lil B, Kamasi Washington, Steve Lacy, Steve Arrington, BADBADNOTGOOD, Louis Cole and Zack Fox. “It Is What It Is” has been nominated for a GRAMMY in the Best Progressive R&B Category and with Flying Lotus also receiving a nomination in the Producer of the Year (Non-Classical). “It Is What It Is” follows his game-changing third album “Drunk” (2017). That record completed his transition from virtuoso bassist to bonafide star and cemented his reputation as a unique voice that transcends genre. “This album is about love, loss, life and the ups and downs that come with that,” Bruner says about “It Is What It Is”. “It’s a bit tongue-in-cheek, but at different points in life you come across places that you don’t necessarily understand… some things just aren’t meant to be understood.” The tragic passing of his friend Mac Miller in September 2018 had a profound effect on Thundercat and the making of “It Is What It Is”. “Losing Mac was extremely difficult,” he explains. “I had to take that pain in and learn from it and grow from it. It sobered me up… it shook the ground for all of us in the artist community.” The unruly bounce of new single ‘Black Qualls’ is classic Thundercat, teaming up with Steve Lacy (The Internet) and Funk icon Steve Arrington (Slave). It’s another example of Stephen Lee Bruner’s desire to highlight the lineage of his music and pay his respects to the musicians who inspired him. Discovering Arrington’s output in his late teens, Bruner says he fell in love with his music immediately: “The tone of the bass, the way his stuff feels and moves, it resonated through my whole body.” ‘Black Qualls’ emerged from writing sessions with Lacy, whom Thundercat describes as “the physical incarnate of the Ohio Players in one person - he genuinely is a funky ass dude”. It references what it means to be a black American with a young mindset: “What it feels like to be in this position right now… the weird ins and outs, we’re talking about those feelings…” Thundercat revisits established partnerships with Kamasi Washington, Louis Cole, Miguel Atwood-Ferguson, Ronald Bruner Jr and Dennis Hamm on “It Is What Is Is” but there are new faces too: Childish Gambino, Steve Lacy, Steve Arrington, plus Ty Dolla $ign and Lil B on ‘Fair Chance’ - a song explicitly about his friend Mac Miller’s passing. The aptly titled ‘I Love Louis Cole’ is another standout - “Louis Cole is a brush of genius. He creates so purely,” says Thundercat. “He makes challenging music: harmony-wise, melody-wise and tempo-wise but still finds a way for it to be beautiful and palatable.” Elsewhere on the album, ‘Dragonball Durag’ exemplifies both Thundercat’s love of humour in music and indeed his passion for the cult Japanese animé. “I have a Dragon Ball tattoo… it runs everything. There is a saying that Dragon Ball runs life,” he explains. “The durag is a superpower, to turn your swag on. It does something… it changes you,” he says smiling. Thundercat’s music starts on his couch at home: “It’s just me, the bass and the computer”. Nevertheless, referring to the spiritual connection that he shares with his longtime writing and production partner Flying Lotus, Bruner describes his friend as “the other half of my brain”. “I wouldn’t be the artist I am if Lotus wasn’t there,” he says. “He taught me… he saw me as an artist and he encouraged it. No matter the life changes, that’s my partner. We are always thinking of pushing in different ways.” Comedy is an integral part of Thundercat’s personality. “If you can’t laugh at this stuff you might as well not be here,” he muses. He seems to be magnetically drawn to comedians from Zack Fox (with whom he collaborates regularly) to Dave Chappelle, Eric Andre and Hannibal Buress whom he counts as friends. “Every comedian wants to be a musician and every musician wants to be a comedian,” he says. “And every good musician is really funny, for the most part.” It’s the juxtaposition, or the meeting point, between the laughter and the pain that is striking listening to “It Is What It Is”: it really is all-encompassing. “The thing that really becomes a bit transcendent in the laugh is when it goes in between how you really feel,” Bruner says. “You’re hoping people understand it, but you don’t even understand how it’s so funny ‘cos it hurts sometimes.” Thundercat forms a cornerstone of the Brainfeeder label; he released “The Golden Age of Apocalypse” (2011), “Apocalypse” (2013), followed by EP “The Beyond / Where The Giants Roam” featuring the modern classic ‘Them Changes’. He was later “at the creative epicenter” (per Rolling Stone) of the 21st century’s most influential hip-hop album Kendrick Lamar’s “To Pimp A Butterfly”, where he won a Grammy for his collaboration on the track ‘These Walls’ before releasing his third album “Drunk” in 2017. In 2018 Thundercat and Flying Lotus composed an original score for an episode of Golden Globe and Emmy award winning TV series “Atlanta” (created and written by Donald Glover).

Cenizas was made between 2017 and 2019.

Richard Russell is many things—musician, DJ, producer, and co-founder of XL Recordings. Making a second album as Everything Is Recorded revealed another calling, though. “Giggs once said to me that I was a time traveler, and I didn’t know what he was talking about,” Russell tells Apple Music. “But this made me aware that a big part of my work is being a connector between people and between eras. With the samples, I’m taking records from the ’70s and ’80s mostly and I’m presenting them to artists who are of now and the future, trying to connect these different times to make something exciting and present.” *FRIDAY FOREVER* tells the turbulent story of a night out and the next day through narrators including UK rap superstar Aitch, punk godhead Penny Rimbaud, and R&B riser Infinite Coles. Russell’s method was to find collaborators based on an emotional connection to their music and what the samples and sketches he’d been working on might inspire in them. They’ve coalesced into a record that bottles the havoc and adventure of a night out before peering uneasily through the bottom of that bottle the following morning. “When I started making music, which was the rave era, I never made an album, I made a bunch of different tracks,” he says. “This is my rave album—but because I’ve made it at this point in my life, it’s as much about the aftermath as it is about the rave.” Here, he takes us though the story track by track. **09:46 PM / EVERY FRIDAY THEREAFTER (Intro) \[feat. Maria Somerville & Berwyn\]** “It’s very minimal. You mainly hear Maria Somerville, Berwyn doing backing vocals and me playing an MS-20 synth. But there\'s definitely some spiritual quality there. Friday night was Sabbath in my family house growing up. It was taken very seriously and I used to participate in that. But then I used to be trying to escape and get on the Northern Line and go into town and go clubbing. So there\'s just a hint of that feeling, and I think it is a spiritual feeling, Friday night is a spiritual moment in different ways for me.” **10:51 PM / THE NIGHT (feat. Berwyn & Maria Somerville)** “Its a very minimal, noisy bit of music. I left all the feedback in, all the noise, didn\'t clean it up at all. Totally raw. I\'ve got a metal water canister and I\'m banging that with a drumstick. I\'m stomping on the floor and I\'m banging on the wooden stair outside my studio. And I just looped me doing that over the Smog sample \[‘Hollow Out Cakes’\]. And then there\'s this great performance by Berwyn. Berwyn is like two people in that song, because there\'s a great song performance and a great rap performance. I think there\'s a bit of danger to it, there\'s edge there, there’s anticipation and there\'s tension.” **12:12 AM / PATIENTS (F\*\*\*\*\*G UP A FRIDAY) \[feat. Aitch & Infinite Coles\]** “Aitch was able to very easily and directly capture that sense of being in the club and things being out of hand. From the first time I heard him—my teenage son played a freestyle of his to me before it had all gone nuts for him—I thought he was amazing. I just thought, ‘What a flow. What a voice. What an attitude.’ He came to the studio and did those two verses incredibly quickly. Infinite is offering a slightly more introspective take on the night out. There\'s very little music in this apart from the 909 drum machine, and the reference there is Schoolly D’s ‘P.S.K.,’ which is one of my favorite rap songs of all time. The music\'s got to spark something for the vocalist, and I think it sparked something for Aitch and Infinite. They both delivered amazing performances.” **01:32 AM / WALK ALONE (feat. Infinite Coles & Berwyn)** “Infinite’s voice has always sounded how I imagine the Paradise Garage to have sounded—although it was a little bit before my time. I started working in Vinylmania Records in New York two to three years after the Paradise Garage closed. That was the record shop that Larry Levan \[Paradise Garage DJ\] used to go to. The record I sampled on here—Man Friday, ‘Love Honey, Love Heartache’—was released on the Vinylmania record label and was produced by Larry Levan. This song is a complete homage and appreciation of \'80s New York, updating that sound—which is incredibly resonant now. What happened at the Paradise Garage had such a seismic, eternal impact on clubbing. There would be no clubbing as we know it really without the Paradise Garage, which in turn was heavily influenced by The Loft.” **02:56 AM / I DONT WANT THIS FEELING TO STOP (feat. FLOHIO)** “I love the Mikey Dread sample \[‘Dizzy’\]. That was on his album *Pave the Way*, which is great. I was actually cutting it up live in the studio and tweaking it, slowing it down, speeding it up, and filtering it while Flohio was writing and doing her vocal performance. That felt very much like a club-type environment, and you can kind of feel that in there, it\'s got that energy. That sample—\'I don\'t want this feeling to stop, I like it\'—caught that peak club moment and that feeling, *which can\'t last* but is what people are looking for on their night out. Then Flohio ran with that. It was a really, really fun, quick, spontaneous song to record.” **03:15 AM / CAVIAR (feat. Ghostface Killah & Infinite Coles)** “This beat was me and Ben Reed, who plays with Frank Ocean sometimes, just jamming. I was playing a really simple 4/4 beat on an MPC, banging it out robotically, and he came up with that rolling bassline. I was like, ‘Yeah, that\'s it. Got something.’ Infinite told this story about an experience he\'d had heading in a taxi in New York to an after-party and these misadventures they were getting into. Infinite \[and I\] talked about doing something with \[Infinite’s father\] Ghostface. We sent the whole thing to him and he just sent that verse back. We couldn\'t believe it when we got it. It was incredible. He\'s such an incredible vocalist in a way that goes beyond any type of genre—he’s just one of the great voices of all time. And obviously Wu-Tang is as resonant and as powerful as ever. So we were really honored for him to join it. And funnily enough, it has my son on it too, playing the live drums that come in halfway through.” **04:21 AM / THAT SKY (feat. Maria Somerville & James Massiah)** “\[We were\] playing around with the Sun Ra sample, and that very free, loose kind of lo-fi feeling it gave, jamming over it with different keyboards, guitar. Maria came in and her voice has this real ethereal beauty to it. I felt like we were getting into that kind of chill-out moment—you’re back at someone\'s house, this is the kind of music you want to hear. I was trying to imagine myself in that spot and what you want to hear. Then James Massiah comes in and he\'s actually telling you about what\'s been happening in his night so far.” **05:10 AM / DREAM I NEVER HAD (feat. A.K. Paul)** “It’s a slightly psychedelic, woozy, kind of melodic fever dream as you’re drifting off. Things not being totally real and things not being totally clear. The Teardrop Explodes sample \[‘Tiny Children’\]—that’s my childhood bedroom music. That came out when I was 10, and Julian Cope’s a hero, I totally love that song. It was really easy to build the rest of it around that. Samples are like giving someone a gift that might spark some kind of response. You’ve got to think about the recipient of the gift. I would think, ‘The sample of Mikey Dread, I want to play that to Flohio. The sample of Julian Cope, I want to play that to A.K. Paul.’ A.K. Paul’s got that sort of Prince-influenced vocal and guitar—Prince had that psychedelic edge.” **09:35 AM / PRETENDING NOTHINGS WRONG (feat. Kean Kavanagh)** “There’s two samples here. There\'s Tangerine Dream, which is those very ominous chords, and then Lamont Dozier saying, ‘Pretending nothing’s wrong when all the time the pain goes on.’ And then Kean Kavanagh…I think those lyrics are just brilliant. We wrote those together, this incredibly visceral, pretty brutal thing that everyone’s experienced: He talks about putting his face down on the lino and feeling the cold of the floor to try to cool himself down, and putting his finger down his throat, and it’s grim. That was the feeling. Then you have this conversation between him and Berwyn, catching up about what the hell happened last night. Those next-day phone conversations are pretty funny, and it was nice to capture that. The song is fairly eerie, but the humor’s very important. That era I started in, there was a lot of humor to all that music, in the hardcore thing. It’s very British. It has to happen naturally, but a lot of music makers are very funny. So when that crops up, it\'s a nice thing.” **10:02 AM / BURNT TOAST (feat. Berwyn & A.K. Paul)** “It’s got that laconic, mellow kind of feel to it. Berwyn\'s rap is quite dark. It\'s a really, really good lyric. And I think A.K. brings that melodic feeling to it. It’s tough and it nods back maybe to a ’90s Bristol sound with that slightly dusty and dark atmospheric, and hip-hop influence. It’s slightly folky as well—a feeling that I think is present on the record.” **11:55 AM / THIS WORLD (feat. Infinite Coles & Maria Somerville)** “I’m as proud of this as of anything I\'ve ever done—just because it has so much feeling to it. \[Before embarking on *FRIDAY FOREVER*\] I was doing a bunch of stuff with Infinite. We did this song, \'This World’s Gonna Break Your Heart,’ which was based on a Maddy Prior & The Carnival Band sample—‘Poor Little Jesus.’ It was beautiful and it really felt like a morning-after song. Then he wrote ‘CAVIAR,’ and he also had a lyric for ‘PATIENTS.’ And I was reading an interview with Francis Ford Coppola, who said, ‘If you want to tell a story, it’s a good idea to have the ending first.’ It suddenly struck me that here was the story: Even in these three songs was a story of going out, things reaching some type of a crescendo, and then the next day. And that made me think we should make a record based on that. I could approach it like a movie, cast it, and tell the cast members, ‘Well, here\'s the story and you can kind of write your scene.’ I play guitar on this, we kept that from the demo, and Owen Pallett added the strings, and there\'s some vocals from Maria right at the end, and it’s really very beautiful, I think.” **11:59 AM / CIRCLES (Outro) \[feat. Penny Rimbaud\]** “It’s a reprise of ‘THIS WORLD.’ Crass were incredibly important to me. Anyone who identifies with that punk spirit, whether they know it or not, they’re relating to Crass. Crass was such a part of the formula: punk being about a DIY approach, about self-reliance, but also being about a communal spirit, and not being pushed around and doing what you think is right. Penny \[Rimbaud, Crass frontman\] embodied that. He does spoken word and is a very spiritual man. When I played him ‘THIS WORLD’ and said, ‘Do you think you could add something on this theme?’ he said, ‘Well, perhaps, but you have to remember I’m an optimist.’ And when he said that, I thought, ‘Actually, so am I. Nonetheless, there’s still something in the idea that this world’s going to break your heart.’ And he was into that. It brings things all the way round. He’s saying, ‘I knew then that I had come down to earth.’ So this really finishes off this kind of journey. I recorded 20 or 30 friends and people who were in the studio just saying the words ‘This world\'s going to break our hearts.’ But then Penny says, ‘With joy.’ That’s an optimistic note, and, as we record this \[interview, during the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak\], a bit of optimism feels very, very important and possibly something people are going to struggle to find for the time being. It feels like a timely song, I suppose.”

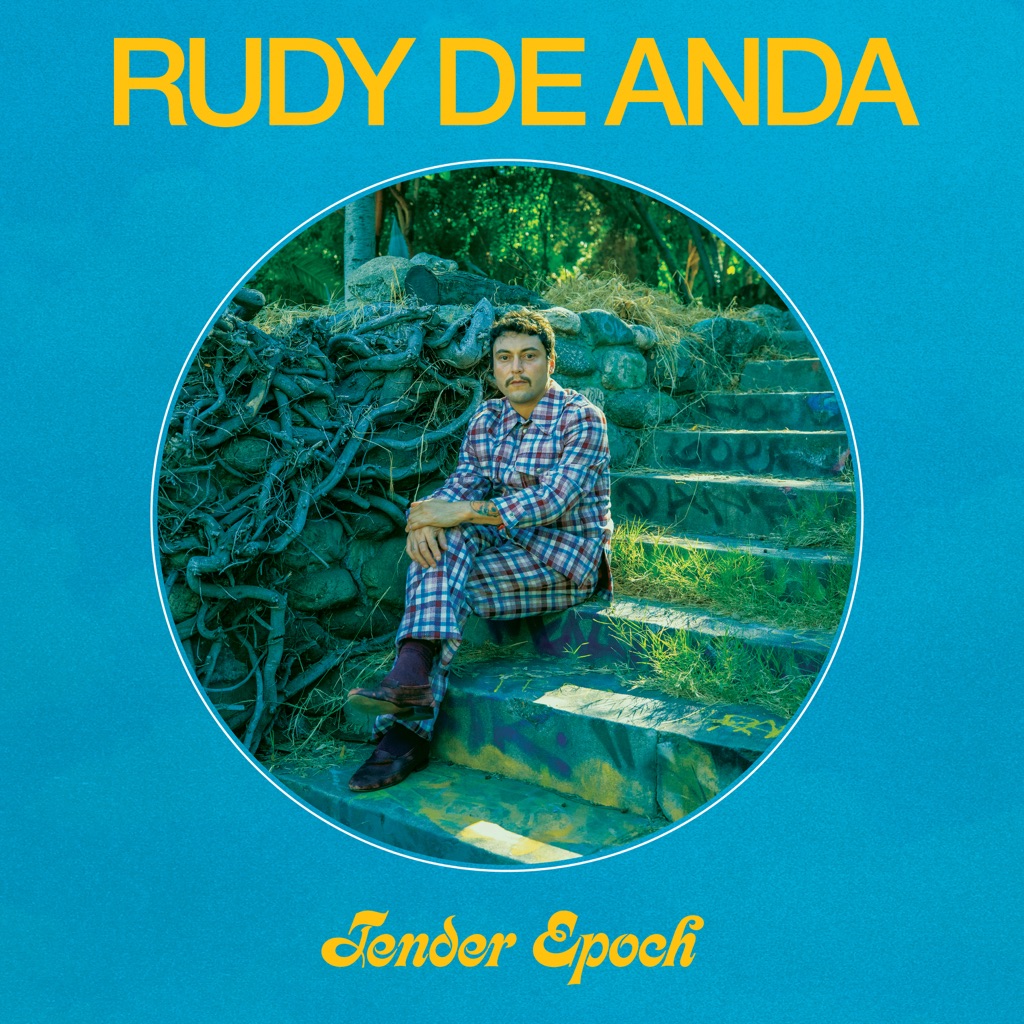

Restlessness is the first step towards pleasure. We make comfort out of discomfort, pleasure out of pain. That journey isn’t always a straight line, but at least we’re going somewhere real. “I had to move, Lord I couldn’t be still” is the unsettled way that Video Age’s new album and title track, Pleasure Line, begins. But as the song unfolds, it uplifts us into a romantic space of possibility and love. Just as “love” is both a noun and a verb, Pleasure Line is both a road to be traveled and the act of crossing that road. Video Age’s first two albums were about loneliness and discovering oneself, but Pleasure Line takes on a whole new attitude, considering songwriting partners Ross Farbe and Ray Micarelli are both getting married this year (just a few weeks apart from each other, too). But these songs aren’t expressions of one-dimensional puppy love—this is euphoria with depth, ecstasy with complications. Video Age’s third album, due out from Winspear on August 7, 2020, pairs neon-bright 80s pop melodies with a vast range of influences (including Janet Jackson, David Bowie, and Paul McCartney) to create an optimistic sound all their own. The influences vary song to song, but they’re all tinted with the same rosy hue. These are catchy, memorable songs that radiate big “glass half-full” energy. Pleasure Line is a salve that protects against cynicism—listening to this album, you can’t help but feel the world around you is full of romantic potential.

You don’t need to know that Fiona Apple recorded her fifth album herself in her Los Angeles home in order to recognize its handmade clatter, right down to the dogs barking in the background at the end of the title track. Nor do you need to have spent weeks cooped up in your own home in the middle of a global pandemic in order to more acutely appreciate its distinct banging-on-the-walls energy. But it certainly doesn’t hurt. Made over the course of eight years, *Fetch the Bolt Cutters* could not possibly have anticipated the disjointed, anxious, agoraphobic moment in history in which it was released, but it provides an apt and welcome soundtrack nonetheless. Still present, particularly on opener “I Want You to Love Me,” are Apple’s piano playing and stark (and, in at least one instance, literal) diary-entry lyrics. But where previous albums had lush flourishes, the frenetic, woozy rhythm section is the dominant force and mood-setter here, courtesy of drummer Amy Wood and former Soul Coughing bassist Sebastian Steinberg. The sparse “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” is backed by drumsticks seemingly smacking whatever surface might be in sight. “Relay” (featuring a refrain, “Evil is a relay sport/When the one who’s burned turns to pass the torch,” that Apple claims was excavated from an old journal from written she was 15) is driven almost entirely by drums that are at turns childlike and martial. None of this percussive racket blunts or distracts from Apple’s wit and rage. There are instantly indelible lines (“Kick me under the table all you want/I won’t shut up” and the show-stopping “Good morning, good morning/You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in”), all in the service of channeling an entire society’s worth of frustration and fluster into a unique, urgent work of art that refuses to sacrifice playfulness for preaching.

Adopted by the United Nations in 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights proclaims the sanctity of human dignities, freedoms, and well-being. If, today, it remains a far-off destination, its values continue to guide and inspire. Max Richter’s *Voices* is a beautiful sonic journey through the Declaration’s principal ideas, combining resonating soundscapes with passages from the document. These appear first in a recording by one of its authors, Eleanor Roosevelt, and are then narrated by actor Kiki Layne, with fragments echoed in more than 70 different languages—each voice crowdsourced via social media. The whole project was 10 years in the making. “The original impetus for *Voices* was the events around Guantanamo, when the revelations came out about the way people had been treated there,” Richter tells Apple Music. “I felt in that moment that the world had gone wrong in a new way, and I wanted to make a piece of music to reflect on it—almost to process it.” There’s a structure and repetition to the Declaration that appeals to Richter, providing a framework for the album. “The way the word *everyone* comes back all the time is very clever,” he says. “It’s got a ritualistic quality—it’s very powerful.” At the core of *Voices* lies a string orchestra that’s “upside down” in terms of its proportions. “It’s all basses and cellos—dark-sounding instruments,” says Richter. “But what I wanted to do is make music which had a sense of hopefulness, luminosity. So I set myself a challenge to make bright music from dark materials. It’s like alchemy—trying to make gold out of base metal.” A “Voiceless Mix” of each piece means listeners will also be able to hear Richter’s score without narration. “It’ll be a chance to think about it all,” he says, “like revisiting a landscape but arriving from another direction.” Here, he guides us through *Voices*, piece by piece. **All Human Beings** “*All Human Beings* sets everything up. It starts with a choral drone, which makes you listen—we have to pay attention to the texts, and I don’t want the music to get in the way of them. So the sound is very reduced and drone-like while we hear readings by Eleanor Roosevelt and Kiki Layne. Then it slowly grows in density and complexity. Once the readings are over, the music blossoms to become something in itself, rather than an accompaniment. I’ve worked a lot with this choir, Tenebrae. They specialize in Renaissance music, and I love that clean sound.” **Origins** “A big part of this project is the idea of a piece of music as a place to think about the world we’ve made and the world we want to make. So the first part of *Origins* is really just that—a chance to reflect on what we’ve just heard, the spoken texts, and the things we’ve just felt. *Origins* starts very simply as a solo piano piece and, with a solo cello, becomes more melodic as it progresses.” **Journey Piece** “*Journey Piece* is mostly choral—it’s quite a short piece. But it speaks to the concept of displacement. In our comfortable Western lives, we think of travel as being something you do for work or pleasure. But a lot of people travel very much against their will. The texts here reflect on these things, and *Journey Piece* is a place to think about them.” **Chorale** “*Chorale* is scored for the orchestra with soprano and violin solos. The title comes from the cyclical nature of the material, echoing the verse structure of J.S. Bach’s chorales. Over its span, the music and the soprano line rise continuously, so the intention is that the music gets brighter the longer it plays.” **Hypocognition** “*Hypocognition* means not being able to express something because you don’t have a name for it. I thought that was an interesting idea. And I think it points to the inability to be in someone else’s shoes, to see someone else’s point of view. The piece is largely electronic and has a conversational relationship with the text. The text is, in a way, the data or frontal-lobe information. And the music evokes the feelings. So, you’re given some information and then given a space to think about it.” **Prelude 6** “‘A little piano piece which seems simple but isn’t. And I think that’s a metaphor for our situation. We all know what the problems are, but it’s not easy to fix them. The piece is in two overlapping time signatures, so it has a slightly unsettled quality.” **Murmuration** “*Murmuration* explores again the idea of migration, of movement against your will, and it occupies a hybrid space between acoustic and electronic music. The sounds are mostly choral, which evoke a sense of ritual, but there is a lot of synthesis and computing going on, which provides a kind of amniotic fluid for the music to inhabit. It just floats in this space.” **Cartography** “*Cartography* is the art of mapmaking, the study of places, so the piece has similar preoccupations to *Murmuration*. It’s a very solitary kind of piece, though, and it sits within a deep silence. Again, it’s a piece that’s not as simple as it sounds—it’s irregular and repetitive and is very much in the style of a lot of my piano music.” **Little Requiems** “The text here is all about motherhood and children, and the need to afford them protection. The less able somebody is, the less they’re able to look after themselves. And, of course, children are disproportionately the victims of everything that’s going on, whether it’s migration or the situation in Syria, for example. It affects the powerless disproportionately. The music here features the string orchestra underneath a rising soprano solo, which allows you the mental space to think about that and the sampled texts.” **Mercy** “*Mercy* is scored for violin solo and piano, and was the first piece I wrote for the album. The title comes from Portia’s speech in Shakespeare’s *The Merchant of Venice*: ‘The quality of mercy is not strained.’ It’s a wonderful speech, all about forgiveness. But it’s about rights, too—if you cut me, do I not bleed? The message is that all people are the same. All through *Voices*, you’ll hear little clues of *Mercy*, so the whole album ends up being a sort of theme-and-variations in reverse.”

Hailing from Melbourne, but with a sound stretching from 60s and 70s afrobeat and exotica to Fela Kuti-esque repetition, the proto-garage rhythmic fury of The Monks and the grooves of Os Mutantes, there’s an enticing lost world exoticism to the music of Bananagun. It’s the sort of stuff that could’ve come from a dusty record crate of hidden gems; yet as the punchy, colourfully vibrant pair of singles Do Yeah and Out of Reach have proven over the past 12 months, the band are no revivalists. On debut album The True Story of Bananagun, they make a giant leap forward with their outward-looking blend of global tropicalia. The True Story of Bananagun marks Bananagun’s first full foray into writing and recording as a complete band, having originally germinated in the bedroom ideas and demos of guitarist, vocalist and flautist Nick van Bakel. The multi-instrumentalist grew up on skate videos, absorbing the hip-hop beats that soundtracked them - taking on touchstones like Self Core label founder Mr. Dibbs and other early 90’s turntablists. That love of the groove underpins Bananagun - even if the rhythms now traverse far beyond those fledgling influences. "We didn't want to do what everyone else was doing,” the band’s founder says. “We wanted it to be vibrant, colourful and have depth like the jungle. Like an ode to nature." Van Bakel was joined first by cousin Jimi Gregg on drums – the pair’s shared love of the Jungle Book apparently made him a natural fit – and the rest of the group are friends first and foremost, put together as a band because of a shared emphasis on keeping things fun. Jack Crook (guitar/vocals), Charlotte Tobin (djembe/percussion) and Josh Dans (bass) complete the five-piece and between them there’s a freshness and playful spontaneity to The True Story of Bananagun, borne out of late night practice jams and hangs at producer John Lee’s Phaedra Studios. “We were playing a lot leading up to recording so we’re all over it live”, van Bakel fondly recalls of the sessions that became more like a communal hang out, with Zoe Fox and Miles Bedford there too to add extra vocals and saxophone. “It was a good time, meeting there every night, using proper gear [rather than my bedroom setups.] It felt like everyone had a bit of a buzz going on.” Tracks like The Master and People Talk Too Much bounce around atop hybrid percussion that fuses West African high life with Brazilian tropicalia; the likes of She Now hark to a more westernised early rhythm ‘n’ blues beat, remoulded and refreshed in the group’s own inimitable summery style. Freak Machine is perhaps the closest to those early 90’s beats, but even then the group add layers and layers of bright guitars, harmonic flower-pop vocals and other sounds to transmute the source material to an entirely new plain. Elsewhere there’s a 90 second track called Bird Up! that cut and pastes kookaburra and parrot calls as an homage to the wildlife surrounding van Bakel’s home 80 kilometres from Melbourne. Oh, and there are hooks galore too – try and stop yourself from humming along to Out of Reach’s swooping vocal melody. Bananagun are first and foremost a band enthused with the joy of living and The True Story of Bananagun is a ebullient listen; van Bakel - as the main songwriter - is keen not to let any lyrical themes overpower that. There’s more to this record than blissed out grooves and tripped out fuzz though: The Master is about learning to be your own master and resisting the urge to compare yourself to others; She Now addresses gender identity and extolls the importance of people being able to identify how they feel. Then there’s closing track Taking The Present For Granted, which perhaps sums up the band’s ethos on life, trying to take in the world around you and appreciating the here and now. A keen meditator, van Bakel says of the track: “so often people are having a shit time stuck in their own existential crisis, but if you get outside you head and participate in life and appreciate how beautiful it all is you can have a better time.” Even the band’s seemingly innocuous name has an underlying message of connectivity that matches the universality of the music. “It’s like non-violent combat! Or the guy who does a stick up, but it’s just a banana, not a gun, and he tells the authorities not to take themselves too seriously.” The True Story of Bananagun then is perhaps a tale of finding beauty in even these most turbulent of times.

Field Music’s new release is “Making A New World”, a 19 track song cycle about the after-effects of the First World War. But this is not an album about war and it is not, in any traditional sense, an album about remembrance. There are songs here about air traffic control and gender reassignment surgery. There are songs about Tiananmen Square and about ultrasound. There are even songs about Becontree Housing Estate and about sanitary towels. The songs grew from a project for the Imperial War Museum and were first performed at their sites in Salford and London in January 2019. The starting point was an image from a 1919 publication on munitions by the US War Department, made using “sound ranging”, a technique that utilised an array of transducers to capture the vibrations of gunfire at the front. These vibrations were displayed on a graph, similar to a seismograph, where the distances between peaks on different lines could be used to pinpoint the location of enemy armaments. This particular image showed the minute leading up to 11am on 11th November 1918, and the minute immediately after. One minute of oppressive, juddering noise and one minute of near-silence. “We imagined the lines from that image continuing across the next hundred years,” says the band’s David Brewis, “and we looked for stories which tied back to specific events from the war or the immediate aftermath.” If the original intention might have been to create a mostly instrumental piece, this research forced and inspired a different approach. These were stories itching to be told. The songs are in a kind of chronological order, starting with the end of the war itself; the uncertainty of heading home in a profoundly altered world (“Coffee or Wine”). Later we hear a song about the work of Dr Harold Gillies (the shimmering ballad, “A Change of Heir”), whose pioneering work on skin grafts for injured servicemen led him, in the 1940s, to perform some of the very first gender reassignment surgeries. We see how the horrors of the war led to the Dada movement and how that artistic reaction was echoed in the extreme performance art of the 60s and 70s (the mathematical head-spin of “A Shot To The Arm”). And then in the funk stomp of Money Is A Memory, we picture an office worker in the German Treasury preparing documents for the final instalment on reparation debts - a payment made in 2010, 91 years after the Treaty of Versailles was signed. A defining, blood-spattered element of 20th century history becomes a humdrum administrative task in a 21st century bureaucracy.

If there was any concern that the red-bearded Queens emcee had abandoned his lyrical signature in favor of oceanography, *Only for Dolphins* opener “Capoeira” quashes that notion quickly. Here, the always entertaining Action Bronson clobbers his way through all of his favorite topics like a pro wrestling gauntlet match. The whistles and clicks made by its titular aquatic mammal play like hip-hop producer drops throughout, but apart from that the album recalls much of his canon and its easygoing greatness. A psychotropic joyride, “C12H16N2” trips through a Lincoln Center screening of Martin Scorsese’s *The Irishman* and its similarly ritzy after-party. From the reggae blasts of “Cliff Hanger” and “Golden Eye” to the lounge dirge of closer “Hard Target,” no matter what type of beat comes his way, Bronsolino mightily molds it to his whim.

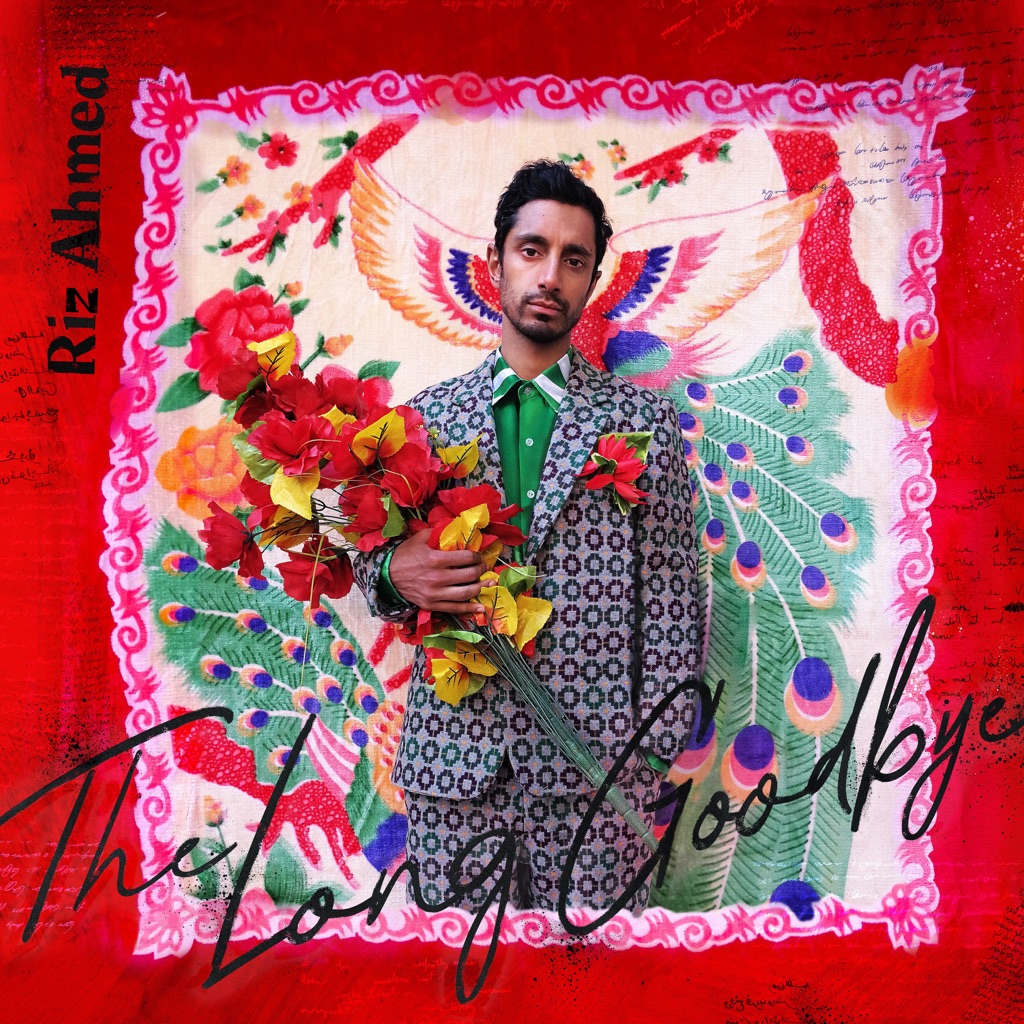

*The Long Goodbye* is a turbulent exploration of identity and belonging, and serves as a painstaking yet necessary passage for British rapper and actor Riz Ahmed. It’s the first music released under his full name, and alongside Swet Shop Boys compadre Redinho—who handles production—he weaves a rich tapestry of formative influences, turning a romantic relationship into a detailed extended metaphor for life in post-Brexit Britain. “It’s a breakup album, but with your country,” he explains. Taking cues from Sufi devotional music and poetry, the result is an urgent, chaotic piece that holds up a mirror to the rising tide of division in the land he calls home. “I wanted to make something that lets people into the feeling of this heartbreak, the anger, the denial, the acceptance, the realization, self-esteem and self-love,” he says. Further contextualized through feature skits, the album stars an extended support cast that includes the artist’s mother, Oscar winner Mahershala Ali, activist Yara Shahidi, and *People Just Do Nothing* actor Asim Chaudhry (playing the glorious Chabuddy G). Here, Ahmed talks us through each of the album’s tracks. **The Break Up (Shikwa)** “‘Shikwa’ is an epic poem by Muhammad Iqbal. It’s Iqbal complaining to God saying, ‘Yo, you abandoned us. Look at us. We\'re being killed in the streets. We\'re homeless, we\'re unloved, we\'re unwashed, we\'re uneducated, we\'ve lost our way. God, where are you?\' With Sufi poetry, they use this metaphor of being separated from your beloved as a way of talking about feeling distant from God. It\'s a way of saying, \'I want to feel spirituality back in my life.\' I had written a lot of the tracks that take you through this journey, and then I realized how many haven\'t been answered in the backstory, and I need to explain how we get to this point where one day I come home and she\'s changed the locks. Let me give you the full story, the messy truth of this relationship.” **Toba Tek Singh** “Toba Tek Singh is a place in Pakistan and it\'s also the name of a short story by this satirical writer \[Saadat Hasan\] Manto, who was often jailed for his writing. It\'s about a character who refuses to choose between India and Pakistan, who refuses to pick a side and makes their home in no man’s land instead—in a space between the two countries. We\'re living in a world that\'s increasingly polarized and it\'s being painted in terms of \'us versus them.\' But there are a lot of us who neither belong to \'us\' nor \'them\'—we are culturally hybrid and we have complex identities. And to me I always think that we\'re in this ‘no man\'s land’ but actually there\'s so many of us there, it\'s not ‘no man\'s land,’ it\'s *our* land.” **Mindy: Take Half** “This is really setting up the concept for the next track, \'Fast Lava,’ which is, ‘How did Britain become Great Britain? How did America become the richest country in the world? On whose backs was that built? If there is going to be a separation, then there needs to be some reparations.’” **Fast Lava** “‘I’ll spit my truth and it\'s Brown.’ I think that means actually no longer apologizing for your identity or having to edit your identity. It\'s about saying, ‘You know what, I\'ve been told to hide who I am. I\'ve been told to kind of tailor who I am to your tastes, for your acceptance. But actually, if you\'re going to try and kick me out, then if you\'re going to stop playing rough with me, then why should I hide who I am anymore?’” **Ammi: Come Home** “That\'s \[Ammi\] my mum, and what she\'s saying in Urdu is, \'Look, I told you, she\'ll be no good for you. There\'s no common ground between you culturally. When are you going to listen to me? Now what can we do? What we are going to do is pray? You know what, just leave with your head held high and come back home if you have to.’ I just say, ‘Mummy, can you leave me a voicemail?’ and she does it. It’s probably the reason I\'m an actor, \'cause she\'s just got such a big personality. She\'s such a natural performer.” **Any Day (feat. Jay Sean)** “This is me taking my mum’s advice: ‘You know what, just leave it, man. Just let it go. Let go of the idea that she\'s ever going to accept you.’ It\'s that moment of looking back at the relationship with all of the nostalgia and feeling a bit of heartache. I was so happy Jay Sean could jump on it, too—an absolute pioneer and also a West Londoner.” **Mahershala: Don’t Do Anything Stupid** “So Mahershala is someone I\'ve got to know, just as we were both gaining some momentum in our careers. He\'s just a real dude with a massive heart, and he\'s just been so supportive. We\'re at the point of the story now where I\'ve taken my mum’s advice, ended the relationship, but now I\'m really depressed. Now I\'m feeling really isolated and rejected, and that\'s what Mahershala talks to, leading into the next track.” **Can I Live** “This is about how rejection, hatred, and prejudice affects our mental health. It makes us hate ourselves, it makes us question ourselves. And over the course of the track, what you have is, I question my place in this relationship, in this world, in this country. I also question what the fuck I\'m doing as an artist. I\'m like, ‘What good is it doing\'? I say \'East and West are clashing but cash is the only outcome.’ By me kind of performing my trauma and performing my pain, is it kind of minstrels-y? What is it? Am I putting my foot down or am I tap-dancing to the man?” **Yara: Look Inside** “Yara is such a young woman but such an inspirational leader, an amazing young voice. She comes in with real wisdom at this point to say, ‘You know what? Just because you\'re not accepted in a relationship doesn\'t mean you can\'t still have acceptance in your life. It doesn\'t mean you can\'t have love in your life.\'” **Where You From** “I guess this is a question that is so common, and to some of us can be annoying. But it\'s also a question we all ask ourselves sometimes: Where are you really from? And a lot of us have quite complex identities. Maybe I\'m not from this place or that place. Maybe I\'m from this \'no man\'s land\' in between, and if I am from this ‘no man\'s land,\' it doesn\'t mean we can\'t plant a flag there and make it habitable. Let\'s still find some dignity.” **Mogambo** “This is an anthem of resilience. You may kind of feel like your position is sometimes under threat, or feel sometimes like you’re on the back foot, but they can\'t take us all out, mate. It\'s like a middle finger.” **Chabuddy: Go Southall** “Chabuddy comes in with the voicemail. It gives it the old ‘You know what? Connect. Connect with other people in this no man’s land with you.’ Let’s go Southall. There are people with you on this journey. Not ‘let\'s get on a plane and go to India, or LA\'—nah, let\'s go Southall: No Man\'s Land HQ.” **Deal With It** “‘Slap two pagans saying that’s too Asian.’ It’s about being your unapologetic self. It’s saying, ‘I don’t need your acceptance, Britney. I don’t need you to love me, I accept myself.’” **Hasan: You Came Out on Top** “Hasan \[Minhaj\] comes on and lets you know that by going on this journey, reconnecting with self-love, you’ve come out resilient. You’ve come out on top.” **Karma** “It’s like a victory lap, I guess. It’s saying we’ve all been through some crazy shit and we’re still here. We’re not going anywhere, because the people that are pushed to the periphery of a society are often the people that make that society special.”

Special Clear Vinyl Edition (50 Only) Comes w/ Enamel Pin and is a Bandcamp Exclusive. Available in LP, Special Edition LP and CD Formats. First 200 LPs hand-numbered. Special Edition LPs come with enamel pin (limited to 200). One thing you won’t be able to avoid on Bambara’s Stray is death. It’s everywhere and inescapable, abstract and personified – perhaps the key to the whole record. Death, however, won’t be the first thing that strikes you about the group’s fourth – and greatest – album to date. That instead will be its pulverising soundscape; by turns, vast, atmospheric, cool, broiling and at times – on stand out tracks like “Sing Me To The Street” and “Serafina” – simply overwhelming. Bambara – twin brothers Reid and Blaze Bateh, singer/guitarist and drummer respectively, and bassist William Brookshire – have been evolving their midnight-black noise into something more subtle and expansive ever since the release of their 2013 debut Dreamviolence. That process greatly accelerated on 2018’s Shadow On Everything, their first on Wharf Cat and a huge stride forward for the band both lyrically and sonically. The album was rapturously received by the press, listeners and their peers. NPR called it a “mesmerising...western, gothic opus,” Bandcamp called the "horror-house rampage" "one of the year's most gripping listens," and Alexis Marshall of Daughters named it his “favorite record of 2018.” Shadow also garnered much acclaim on the other side of the Atlantic. Influential British 6Music DJ Steve Lamacq, dubbed them the best band of 2019’s SXSW, and Joe Talbot of the UK band IDLES said, "The best thing I heard last year was easily Bambara and their album Shadow On Everything." The question was, though, how to follow it? To start, the band did what they always do: they locked themselves in their windowless Brooklyn basement to write. Decisions were made early on to try and experiment with new instrumentation and song structures, even if the resulting compositions would force the band to adapt their storied live set, known for its tenacity and technical prowess. Throughout the songwriting process, the band pulled from their deep well of creative references, drawing on the likes of Leonard Cohen, Ennio Morricone, Sade, classic French noir L’Ascenseur Pour L’Echafraud, as well as Southern Gothic stalwarts Flannery O’Connor and Harry Crews. Once the building blocks were set in place, they met with producer Drew Vandenberg, who mixed Shadow On Everything, in Athens, GA to record the foundation of Stray. After recruiting friends Adam Markiewicz (The Dreebs) on violin, Sean Smith (Klavenauts) on trumpet and a crucial blend of backing vocals by Drew Citron (Public Practice) and Anina Ivry-Block (Palberta), Bambara convened in a remote cabin in rural Georgia, where Reid laid down his vocals. The finished product represents both the band's most experimental and accessible work to date. The addition of Citron and Ivory-Block’s vocals create a hauntingly beautiful contrast to Bateh’s commanding baritone on tracks like “Sing Me to the Street”, “Death Croons” and “Stay Cruel," while the Dick Dale inspired guitar riffs on “Serafina” and "Heat Lightning" and the call-and-response choruses throughout the album showcase Bambara’s ability to write songs that immediately demand repeat listens. While the music itself is evocative and propulsive, a fever dream all of its own, the lyrical content pushes the record even further into its own darkly thrilling realm. If the songs on Shadow On Everything were like chapters in a novel, then this time they’re short stories. Short stories connected by death and its effect on the characters in contact with it. “Death is what you make it” runs a lyric in “Sweat,” a line which may very well be the thread that ties the pages of these stories together. But it would be wrong to characterize Stray as simply the sound of the graveyard. Light frequently streams through and, whether refracted through the love and longing found on songs like “Made for Me” or the fantastical nihilism on display in tracks like the anthemic “Serafina,” reveals this album to be the monumental step forward that it is. Here Bambara sound like they’ve locked into what they were always destined to achieve, and the effect is nothing short of electrifying.

Disq have assembled a razor-sharp, teetering-on-the-edge-of-chaos melange of sounds, experiences, memories, and influences. Collector ought to be taken literally—it is a place to explore and catalogue the Madison, Wisconsin band’s relationships to themselves, their pasts, and the world beyond the American Midwest as they careen from their teens into their 20s. This turbulence is backdropped by gnarled power pop, anxious post-punk, warm psych-folk, and hectic, formless, tongue-in-cheek indie rock. Collector, like the band itself, is defined and tightly-contoured by the ties between the five members. Raina Bock (bass/vocals) and Isaac deBroux-Slone (guitar/vocals) have known each other from infancy, growing up and into music together. Through gigging around Madison, they met and befriended Shannon Connor (guitar/keys/vocals), Logan Severson (guitar/vocals), and Brendan Manley (drums)—three equally dedicated and adventurous musicians committed to coaxing genre boundaries. Produced by Rob Schnapf, Collector is a set of songs largely pulled from each of the five members’ demo piles over the years. They’re organic representations of each moment in time, gathered together to tell a mixtape-story of growing up in 21st century America. The songs are marked by urgency, introspection, tongue-in-cheek nihilism, and a shrewd understanding of pop and rock structures and their corollaries—as well as a keen desire to dialogue with and upset them.

The dream of 1970s downtown New York—contrasting avant-garde art rock and jittery No Wave skronk—is alive in Brooklyn post-punks Public Practice. On their debut album, *Gentle Grip*, the quartet (featuring members of indie-pop group Beverly and clangorous punks WALL) reimagines vintage sounds for modern counterculture, delivered through frontwoman Sam York’s disaffected staccato voice. Anti-capitalist anthem “Disposable” is dystopic B-52’s, making a good partner to the anti-materialist, bass-forward banger “Compromised.” “My Head” is unexpectedly groovy, like something straight out of the downtrodden dance music of Liquid Liquid; “Disposable” is punk-funk New Wave. While Public Practice wears their influences on their sleeve, the band has managed to shape those familiar sounds into something entirely new on *Gentle Grip*: an innovative and tense disco for listeners begging to be challenged.

Digital id out on 5/15 & LPs & CDs ship on 6/26. First 150 black vinyl records hand-numbered on a first come, first served basis. Public Practice is reanimating the spirit of late ‘70s New York with their intoxicating brand of no wave-tinged dark disco. The band came in hot with their punchy balance of punk, funk, and pop on the critically acclaimed Distance is a Mirror EP in 2018, paving the way for their highly anticipated freshman record. Now, after a year of intimate and experimental songwriting in their home studio, they have fleshed out the energetic, playfully oblique sound captured on their debut full-length Gentle Grip. Together, the foursome creates bold, slinky rhythms and groove-filled hooks that get under your skin and into your dancing shoes. The musicians’ unique chemistry and approach to songwriting is part of what makes their world so intriguing. Magnetic singer and lyricist Sam York and guitarist and principal sonic architect Vince McClelland, who were creative music partners for years prior to Public Practice’s formation, come to the table with an anarchic perspective that aims to eradicate creative barriers by challenging the very idea of what a song can be. Paradoxically, Drew Citron, on bass/vocals/synth, and drummer/producer Scott Rosenthal are uncannily adept at working within the framework of classic pop structures. But instead of clashing, these contrasting styles challenge and complement one another, resulting in an album full of spiraling tensions and unexpected turns. Inspired by influential New York bands like Liquid Liquid and ESG, the foursome has a natural inclination toward music that sounds rough-hewn. “We were thinking about classic New York dance albums, and the thing that stuck out is that many sounded like they were recorded in less-than-ideal situations,” McClelland says. “There was always something about them that felt somewhat home-cooked.” McClelland has spent the past few years constructing a home studio with carefully chosen and occasionally hand-made equipment in an effort to recreate that “cobbled together” sound. As three quarters of Public Practice are engineers as well as instrumentalists, their collection of gear, combined with the recording rig McClelland built, allowed the band to record Gentle Grip largely at their own hybrid practice space/studio in Brooklyn. “Having a space and setup that is unique, you're always going to have more of a signature sound,” McClelland explains. They spent the better part of 2019 playing with sounds, riffing on McClelland’s demos, and recording a number of songs live to tape. Although a handful of sessions occurred in traditional recording studios, the band’s autonomy and ability to record themselves imbues their music with a sense of freedom and gives it a distinct character — a home-cooked sound that is purely Public Practice. York, who writes all of Public Practice’s lyrics, with the exception of the McClelland-penned “How I Like It,” explores the complexities and contradictions of modern life overtop danceable rhythms and choruses that disarmingly open up the doors to self-reflection. “You don’t want to live a lie / But it’s easy" York sings on “Compromised," the record’s brisk, gyrating lead single. As York puts it, “No one's moral compass reads truth north at all times. We all want to be our best green recycling selves, but still want to buy the shiny new shoes — how do you emotionally navigate through that? How do you balance material desires with the desire to be seen as morally good?” Towards the slinkier end of the album's auditory spectrum, songs like the supremely danceable “My Head” — which is about tuning out the incessant influx of external noise and finding your own internal groove — are more personally political but still hearken the last days of disco. While York’s songwriting focuses on the existential, McClelland has a serious aptitude for the technical aspects of music-making. He talks about music like an engineer with a sculptor’s mind and is especially drawn to ideas and structures antithetical to the standard pop repertoire. This unconventional creative drive gives rise to songs that play around with chord changes, instrumentation, and timbral qualities like “Hesitation,” Gentle Grip’s final track, which was constructed around the same note repeated on three different instruments. It also accounts for the bold experimentation found on songs like “See You When I Want To,” which was created by the band improvising with sounds over a steady beat while York free-associated lyrics. Far-ranging as Gentle Grip may be topically and stylistically, on their debut long-player Public Practice never lose sight of the fact that they want to have fun, and they want you to have fun too — a fact is inescapably evident in their frenetic live set, with York’s stage presence casting a spell like a young Debbie Harry, or Gudrun Gut circa Malaria! They make it almost impossible not to dance, and reveal that they are a band with a knack not only for curious, catchy songwriting but also for old school New York drama. And whether they are poking holes in commonly held ideas centered around relationships, creativity, capitalism, or chord structures, Public Practice stay on the same plane as their audience and remain part of conversation. After all, who wants to stand on top of a soapbox when there’s a dark, sweaty dance floor out there with room for all of us?

Much of Grimes’ fifth LP is rooted in darkness, a visceral response to the state of the world and the death of her friend and manager Lauren Valencia. “It’s like someone who\'s very core to the project just disappearing,” she tells Apple Music of the loss. “I\'ve known a lot of people who\'ve died, but cancer just feels so demonic. It’s like someone who wants to live, who\'s a good person, and their life is just being taken away by this thing that can\'t be explained. I don\'t know, it just felt like a literal demon.” *Miss Anthropocene* deals heavily in theological ideas, each song meant to represent a new god in what Grimes loosely envisioned as “a super contemporary pantheon”—“Violence,” for example, is the god of video games, “My Name Is Dark (Art Mix)” the god of political apathy, and “Delete Forever” the god of suicide. The album’s title is that of the most “urgent” and potentially destructive of gods: climate change. “It’s about modernity and technology through a spiritual lens,” she says of the album, itself an iridescent display of her ability as a producer, vocalist, and genre-defying experimentalist. “I’ve also just been feeling so much pressure. Everyone\'s like, ‘You gotta be a good role model,’ and I was kind of thinking like, ‘Man, sometimes you just want to actually give in to your worst impulses.’ A lot of the record is just me actually giving in to those negative feelings, which feels irresponsible as a writer sometimes, but it\'s also just so cathartic.” Here she talks through each of the album\'s tracks. **So Heavy I Fell Through the Earth (Art Mix)** “I think I wanted to make a sort of hard Enya song. I had a vision, a weird dream where I was just sort of falling to the earth, like fighting a Balrog. I woke up and said, ‘I need to make a video for this, or I need to make a song for this.’ It\'s sort of embarrassing, but lyrically, the song is kind of about when you decide to get pregnant or agree to get pregnant. It’s this weird loss of self, or loss of power or something. Because it\'s sort of like a future life in subservience to this new life. It’s about the intense experience deciding to do that, and it\'s a bit of an ego death associated with making that decision.” **Darkseid** “I forget how I met \[Lil\] Uzi \[Vert\]. He probably DMed me or something, just like, ‘Wanna collaborate and hang out and stuff?’ We ended up playing laser tag and I just did terribly. But instrumentally, going into it I was thinking, ‘How do I make like a super kind of goth banger for Uzi?’ When that didn\'t really work out, I hit up my friend Aristophanes, or Pan. Just because I think she\'s fucking great, and I think she\'s a great lyricist and I just love her vocal style, and she kind of sounds good on everything, and it\'s especially dark stuff. Like she would make this song super savage and intense. I should let Pan explain it, but her translation of the lyrics is about a friend of hers who committed suicide.” **Delete Forever** “A lot of people very close to me have been super affected by the opioid crisis, or just addiction to opiates and heroin—it\'s been very present in my life, always. When Lil Peep died, I just got super triggered and just wanted to go make something. It seemed to make sense to keep it super clean sonically and to keep it kind of naked. so it\'s a pretty simple production for me. Normally I just go way harder. The banjo at the end is comped together and Auto-Tuned, but that is my banjo playing. I really felt like Lil Peep was about to make his great work. It\'s hard to see anyone die young, but especially from this, ’cause it hit so close to home.” **Violence** “This sounds sort of bad: In a way it feels like you\'re giving up when you sing on someone else\'s beats. I literally just want to produce a track. But it was sort of nice—there was just so much less pain in that song than I think there usually is. There\'s this freedom to singing on something I\'ve never heard before. I just put the song on for the first time, the demo that \[producer/DJ\] i\_o sent me, and just sang over it. I was like, \'Oh!\' It was just so freeing—I never ever get to do that. Everyone\'s like, ‘What\'s the meaning? What\'s the vibe?’ And honestly, it was just really fucking fun to make. I know that\'s not good, that everyone wants deeper meanings and emotions and things, but sometimes just the joy of music is itself a really beautiful thing.” **4ÆM** “I got really obsessed with this Bollywood movie called *Bajirao Mastani*—it’s about forbidden love. I was like, ‘Man, I feel like the sci-fi version of this movie would just be incredible.’ So I was just sort of making fan art, and I then I really wanted to get kind of crazy and futuristic-sounding. It’s actually the first song I made on the record—I was kind of blocked and not sure of the sonic direction, and then when I made this I was like, ‘Oh, wow, this doesn\'t sound like anything—this will be a cool thing to pursue.’ It gave me a bunch of ideas of how I could make things sound super future. That was how it started.” **New Gods** “I really wish I started the record with this song. I just wanted to write the thesis down: It\'s about how the old gods sucked—well, I don\'t want to say they sucked, but how the old gods have definitely let people down a bit. If you look at old polytheistic religions, they\'re sort of pre-technology. I figured it would be a good creative exercise to try to think like, ‘If we were making these gods now, what would they be like?’ So it\'s sort of about the desire for new gods. And with this one, I was trying to give it a movie soundtrack energy.” **My Name Is Dark (Art Mix)** “It\'s sort of written in character, but I was just in a really cranky mood. Like it\'s just sort of me being a whiny little brat in a lot of ways. But it\'s about political apathy—it’s so easy to be like, ‘Everything sucks. I don\'t care.’ But I think that\'s a very dangerous attitude, a very contagious one. You know, democracy is a gift, and it\'s a thing not many people have. It\'s quite a luxury. It seems like such a modern affliction to take that luxury for granted.” **You’ll miss me when I’m not around** “I got this weird bass that was signed by Derek Jeter in a used music place. I don\'t know why—I was just trying to practice the bass and trying to play more instruments. This one feels sort of basic for me, but I just really fell in love with the lyrics. It’s more like ‘Delete Forever,’ where it feels like it\'s almost too simple for Grimes. But it felt really good—I just liked putting it on. Again, you gotta follow the vibe, and it had a good vibe. Ultimately it\'s sort of about an angel who kills herself and then she wakes up and she still made it to heaven. And she\'s like, \'What the fuck? I thought I could kill myself and get out of heaven.’ It\'s sort of about when you\'re just pissed and everyone\'s being a jerk to you.” **Before the Fever** “I wanted this song to represent literal death. Fevers are just kind of scary, but a fever is also sort of poetically imbued with the idea of passion and stuff too. It\'s like it\'s a weirdly loaded word—scary but compelling and beautiful. I wanted this song to represent this trajectory where like it starts sort of threatening but calm, and then it slowly gets sort of more pleading and like emotional and desperate as it goes along. The actual experience of death is so scary that it\'s kind of hard to keep that aloofness or whatever. I wanted it to sort of be like following someone\'s psychological trajectory if they die. Specifically a kind of villain. I was just thinking of the Joffrey death scene in *Game of Thrones*. And it\'s like, he\'s so shitty and such a prick, but then, when he dies, like, you feel bad for him. I kind of just wanted to express that feeling in the song.” **IDORU** “The bird sounds are from the Squamish birdwatching society—their website has lots of bird sounds. But I think this song is sort of like a pure love song. And it just feels sort of heavenly—I feel very enveloped in it, it kind of has this medieval/futurist thing going on. It\'s like if ‘Before the Fever’ is like the climax of the movie, then ‘IDORU’ is the end title. It\'s such a negative energy to put in the world, but it\'s good to finish with something hopeful so it’s not just like this mean album that doesn\'t offer you anything.”