Rough Trade UK's Albums of the Year 2021

Buy and pre-order vinyl records, books + merchandise online from Rough Trade, independent purveyors of great music, since 1976.

Source

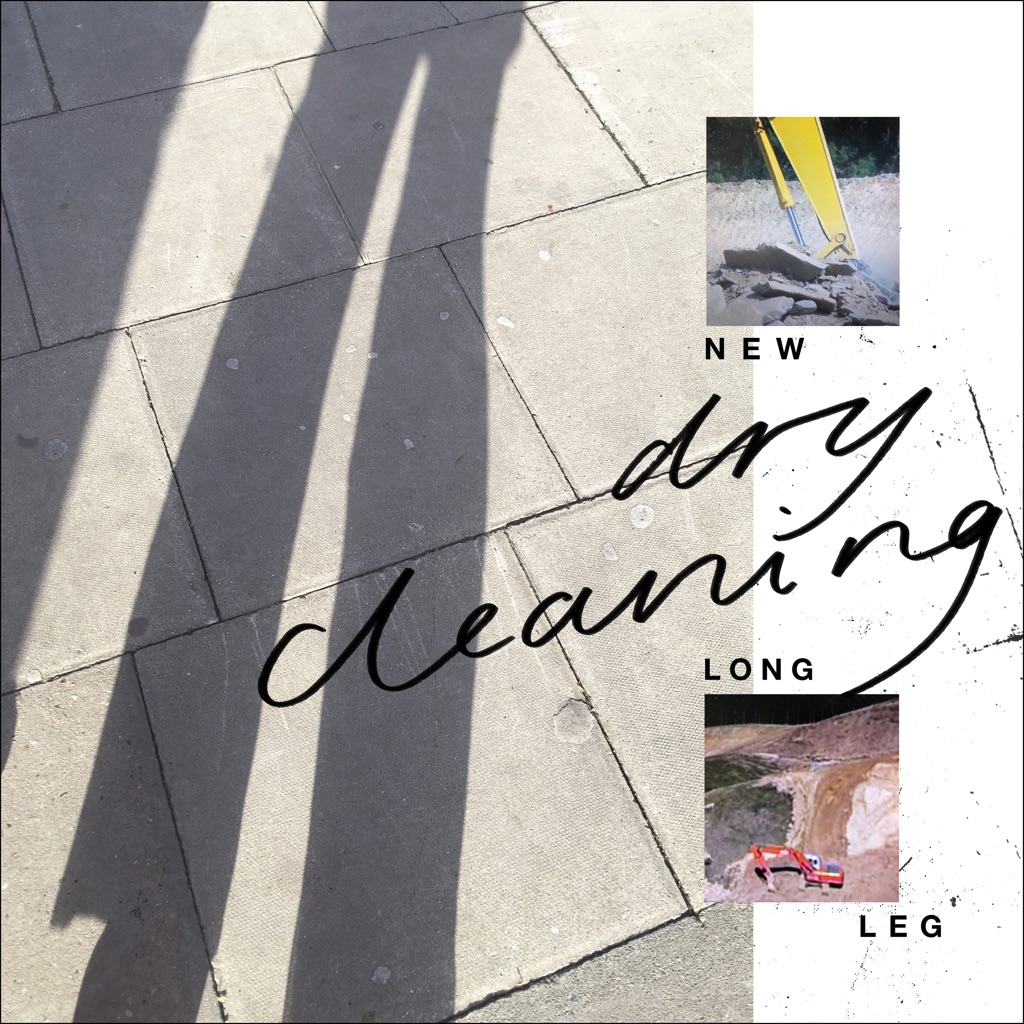

“Straight away,” Dry Cleaning drummer Nick Buxton tells Apple Music. “Immediately. Within the first sentence, literally.” That is precisely how long it took for Buxton and the rest of his London post-punk outfit to realize that Florence Shaw should be their frontwoman, as she joined in with them during a casual Sunday night jam in 2018, reading aloud into the mic instead of singing. Though Buxton, guitarist Tom Dowse, and bassist Lewis Maynard had been playing together in various forms for years, Shaw—a friend and colleague who’s also a visual artist and university lecturer—had no musical background or experience. No matter. “I remember making eye contact with everyone and being like, ‘Whoa,’” Buxton says. “It was a big moment.” After a pair of 2019 EPs comes the foursome’s full-length debut, *New Long Leg*, an hypnotic tangle of shape-shifting guitars, mercurial rhythms, and Shaw’s deadpan (and often devastating) spoken-word delivery. Recorded with longtime PJ Harvey producer John Parish at the historic Rockfield Studios in Wales, it’s a study in chemistry, each song eventually blooming from jams as electric as their very first. Read on as Shaw, Buxton, and Dowse guide us through the album track by track. **“Scratchcard Lanyard”** Nick Buxton: “I was quite attracted to the motorik-pedestrian-ness of the verse riffs. I liked how workmanlike that sounded, almost in a stupid way. It felt almost like the obvious choice to open the album, and then for a while we swayed away from that thinking, because we didn\'t want to do this cliché thing—we were going to be different. And then it becomes very clear to you that maybe it\'s the best thing to do for that very reason.” **“Unsmart Lady”** Florence Shaw: “The chorus is a found piece of text, but it suited what I needed it for, and that\'s what I was grasping at. The rest is really thinking about the years where I did lots and lots of jobs all at the same time—often quite knackering work. It’s about the female experience, and I wanted to use language that\'s usually supposed to be insulting, commenting on the grooming or the intelligence of women. I wanted to use it in a song, and, by doing that, slightly reclaim that kind of language. It’s maybe an attempt at making it prideful rather than something that is supposed to make you feel shame.” **“Strong Feelings”** FS: “It was written as a romantic song, and I always thought of it as something that you\'d hear at a high school dance—the slow one where people have to dance together in a scary way.” **“Leafy”** NB: “All of the songs start as jams that we play all together in the rehearsal room to see what happens. We record it on the phone, and 99 percent of the time you take that away and if it\'s something that you feel is good, you\'ll listen to it and then chop it up into bits, make changes and try loads of other stuff out. Most of the jams we do are like 10 minutes long, but ‘Leafy’ was like this perfect little three-minute segment where we were like, ‘Well, we don\'t need to do anything with that. That\'s it.’” **“Her Hippo”** FS: “I\'m a big believer in not waiting for inspiration and just writing what you\'ve got, even if that means you\'re writing about a sense of nothingness. I think it probably comes from there, that sort of feeling.” **“New Long Leg”** NB: “I\'m really proud of the work on the album that\'s not necessarily the stuff that would jump out of your speakers straight away. ‘New Long Leg’ is a really interesting track because it\'s not a single, yet I think it\'s the strongest song on the album. There\'s something about the quality of what\'s happening there: Four people are all bringing something, in quite an unusual way, all the way around. Often, when you hear music like that, it sounds mental. But when you break it down, there\'s a lot of detail there that I really love getting stuck into.” **“John Wick”** FS: “I’m going to quote Lewis, our bass player: The title ‘John Wick’ refers to the film of the same name, but the song has nothing to do with it.” Tom Dowse: “Giving a song a working title is quite an interesting process, because what you\'re trying to do is very quickly have some kind of onomatopoeia to describe what the song is. ‘Leafy’ just sounded leafy. And ‘John Wick’ sounded like some kind of action cop show. Just that riff—it sounded like crime was happening and it painted a picture straight away. I thought it was difficult to divorce it from that name.” **“More Big Birds”** TD: “One of the things you get good at when you\'re a band and you\'re lucky enough to get enough time to be together is, when someone writes a drum part like that, you sit back. It didn\'t need a complicated guitar part, and sometimes it’s nice to have the opportunity to just hit a chord. I love that—I’ll add some texture and let the drums be. They’re almost melodic.” **“A.L.C”** FS: “It\'s the only track where I wrote all the lyrics in lockdown—all the others were written over a much longer period of time. But that\'s definitely the quickest I\'ve ever written. It\'s daydreaming about being in public and I suppose touches on a weird change of priorities that happened when your world just gets really shrunk down to your little patch. I think there\'s a bit of nostalgia in there, just going a bit loopy and turning into a bit of a monster.” **“Every Day Carry”** FS: “It was one of the last ones we recorded and I was feeling exhausted from trying so fucking hard the whole recording session to get everything I wanted down. I had sheets of paper with different chunks that had already been in the song or were from other songs, and I just pieced it together during the take as a bit of a reward. It can be really fun to do that when you don\'t know what you\'re going to do next, if it\'s going to be crap or if it\'s going to be good. That\'s a fun thing—I felt kind of burnt out, so it was nice to just entertain myself a bit by doing a surprise one.”

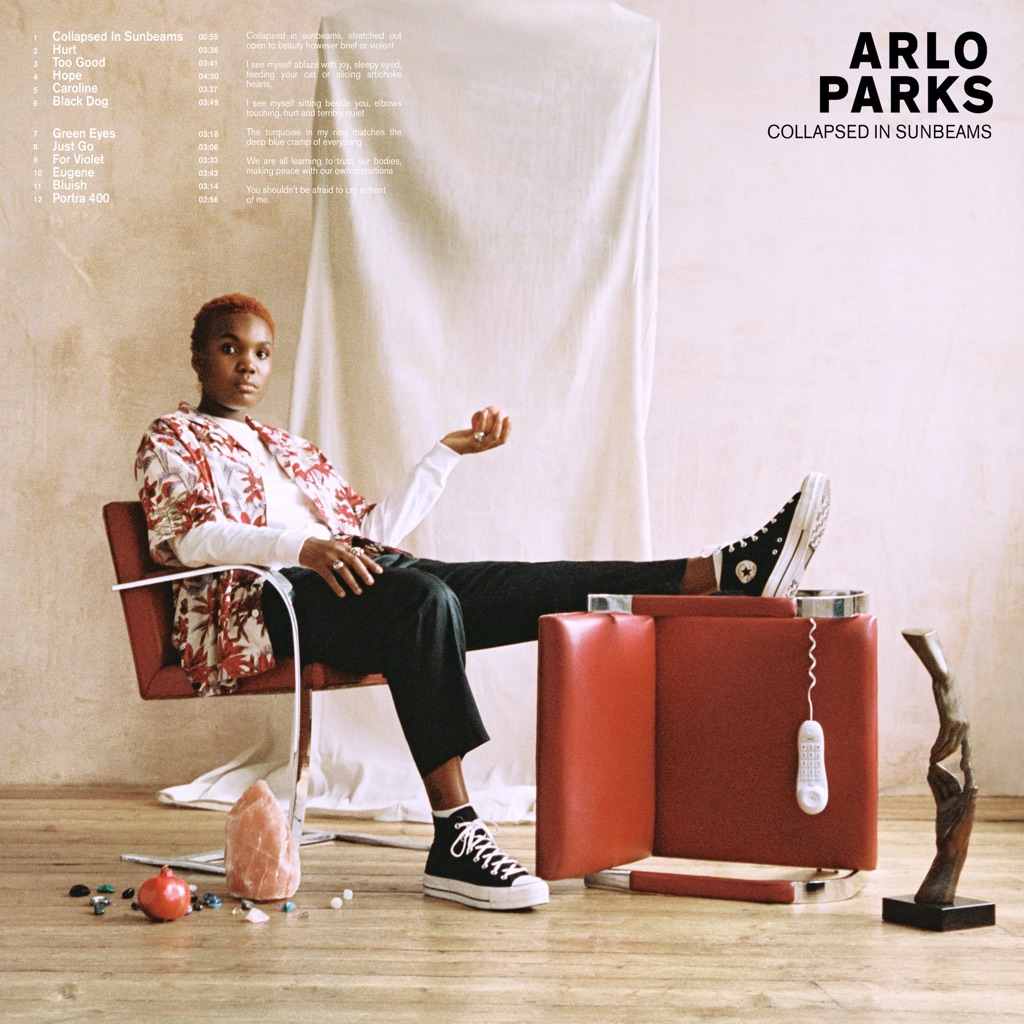

“I don’t like to agonize over things,” Arlo Parks tells Apple Music. “It can tarnish the magic a little. Usually a song will take an hour or less from conception to end. If I listen back and it’s how I pictured it, I move on.” The West London poet-turned-songwriter is right to trust her “gut feeling.” *Collapsed in Sunbeams* is a debut album that crystallizes her talent for chronicling sadness and optimism in universally felt indie-pop confessionals. “I wanted a sense of balance,” she says. “The record had to face the difficult parts of life in a way that was unflinching but without feeling all-consuming and miserable. It also needed to carry that undertone of hope, without feeling naive. It had to reflect the bittersweet quality of being alive.” *Collapsed in Sunbeams* achieves all this, scrapbooking adolescent milestones and Parks’ own sonic evolution to form something quite spectacular. Here, she talks us through her work, track by track. **Collapsed in Sunbeams** “I knew that I wanted poetry in the album, but I wasn\'t quite sure where it was going to sit. This spoken-word piece is actually the last thing that I did for the album, and I recorded it in my bedroom. I liked the idea of speaking to the listener in a way that felt intimate—I wanted to acknowledge the fact that even though the stories in the album are about me, my life and my world, I\'m also embarking on this journey with listeners. I wanted to create an avalanche of imagery. I’ve always gravitated towards very sensory writers—people like Zadie Smith or Eileen Myles who hone in on those little details. I also wanted to explore the idea of healing, growth, and making peace with yourself in a holistic way. Because this album is about those first times where I fell in love, where I felt pain, where I stood up for myself, and where I set boundaries.” **Hurt** “I was coming off the back of writer\'s block and feeling quite paralyzed by the idea of making an album. It felt quite daunting to me. Luca \[Buccellati, Parks’ co-producer and co-writer\] had just come over from LA, and it was January, and we hadn\'t seen each other in a while. I\'d been listening to plenty of Motown and The Supremes, plus a lot of Inflo\'s production and Cleo Sol\'s work. I wanted to create something that felt triumphant, and that you could dance to. The idea was for the song to expose how tough things can be but revolve around the idea of the possibility for joy in the future. There’s a quote by \[Caribbean American poet\] Audre Lorde that I really liked: ‘Pain will either change or end.’ That\'s what the song revolved around for me.” **Too Good** “I did this one with Paul Epworth in one of our first days of sessions. I showed him all the music that I was obsessed with at the time, from ’70s Zambian psychedelic rock to MF DOOM and the hip-hop that I love via Tame Impala and big ’90s throwback pop by TLC. From there, it was a whirlwind. Paul started playing this drumbeat, and then I was just running around for ages singing into mics and going off to do stuff on the guitar. I love some of the little details, like the bump on someone’s wrist and getting to name-drop Thom Yorke. It feels truly me.” **Hope** “This song is about a friend of mine—but also explores that universal idea of being stuck inside, feeling depressed, isolated, and alone, and being ashamed of feeling that way, too. It’s strange how serendipitous a lot of themes have proved as we go through the pandemic. That sense of shame is present in the verses, so I wanted the chorus to be this rallying cry. I imagined a room full of people at a show who maybe had felt alone at some point in their lives singing together as this collective cry so they could look around and realize they’re not alone. I wanted to also have the little spoken-word breakdown, just as a moment to bring me closer to the listener. As if I’m on the other side of a phone call.” **Caroline** “I wrote ‘Caroline’ and ‘For Violet’ on the same, very inspired day. I had my little £8 bottle of Casillero del Diablo. I was taken back to when I first started writing at seven or eight, where I would write these very observant and very character-based short stories. I recalled this argument that I’d seen taken place between a couple on Oxford Street. I only saw about 30 seconds of it, but I found myself wondering all these things. Why was their relationship exploding out in the open like that? What caused it? Did the relationship end right there and then? The idea of witnessing a relationship without context was really interesting to me, and so the lyrics just came out as a stream of consciousness, like I was relaying the story to a friend. The harmonies are also important on this song, and were inspired by this video I found of The Beatles performing ‘This Boy.’ The chorus feels like such an explosion—such a release—and harmonies can accentuate that.” **Black Dog** “A very special song to me. I wrote this about my best friend. I remember writing that song and feeling so confused and helpless trying to understand depression and what she was going through, and using music as a form of personal catharsis to work through things that felt impossible to work through. I recorded the vocals with this lump in my throat because it was so raw. Musically, I was harking back to songs like ‘Nude’ and ‘House of Cards’ on *In Rainbows*, plus music by Nick Drake and tracks from Sufjan Stevens’ *Carrie & Lowell*. I wanted something that felt stripped down.” **Green Eyes** “I was really inspired by Frank Ocean here—particularly ‘Futura Free’ \[from 2016’s *Blonde*\]. I was also listening to *Moon Safari* by Air, Stereolab, Unknown Mortal Orchestra, Tirzah, Beach House, and a lot of that dreamy, nostalgic pop music that I love. It was important that the instrumental carry a warmth because the song explores quite painful places in the verses. I wanted to approach this topic of self-acceptance and self-discovery, plus people\'s parents not accepting them and the idea of sexuality. Understanding that you only need to focus on being yourself has been hard-won knowledge for me.” **Just Go** “A lot of the experiences I’ve had with toxic people distilled into one song. I wanted to talk about the idea of getting negative energy out of your life and how refreshed but also sad it leaves you feeling afterwards. That little twinge from missing someone, but knowing that you’re so much better off without them. I was thinking about those moments where you’re trying to solve conflict in a peaceful way, but there are all these explosions of drama. You end up realizing, ‘You haven’t changed, man.’ So I wanted a breakup song that said, simply, ‘No grudges, but please leave my life.’” **For Violet** “I imagined being in space, or being in a desert with everything silent and you’re alone with your thoughts. I was thinking about ‘Roads’ by Portishead, which gives me that similar feeling. It\'s minimal, it\'s dark, it\'s deep, it\'s gritty. The song covers those moments growing up when you realize that the world is a little bit heavier and darker than you first knew. I think everybody has that moment where their innocence is broken down a little bit. It’s a story about those big moments that you have to weather in friendships, and asking how you help somebody without over-challenging yourself. That\'s a balance that I talk about in the record a lot.” **Eugene** “Both ‘Black Dog’ and ‘Eugene’ represent a middle chapter between my earlier EPs and the record. I was pulling from all these different sonic places and trying to create a sound that felt warmer, and I was experimenting with lyrics that felt a little more surreal. I was talking a lot about dreams for the first time, and things that were incredibly personal. It felt like a real step forward in terms of my confidence as a writer, and to receive messages from people saying that the song has helped get them to a place where they’re more comfortable with themselves is incredible.” **Bluish** “I wanted it to feel very close. Very compact and with space in weird places. It needed to mimic the idea of feeling claustrophobic in a friendship. That feeling of being constantly asked to give more than you can and expected to be there in ways that you can’t. I wanted to explore the idea of setting boundaries. The Afrobeat-y beat was actually inspired by Radiohead’s ‘Identikit’ \[from 2016’s *A Moon Shaped Pool*\]. The lyrics are almost overflowing with imagery, which was something I loved about Adrianne Lenker’s *songs* album: She has these moments where she’s talking about all these different moments, and colors and senses, textures and emotions. This song needed to feel like an assault on the senses.” **Portra 400** “I wanted this song to feel like the end credits rolling down on one of those coming-of-age films, like *Dazed and Confused* or *The Breakfast Club*. Euphoric, but capturing the bittersweet sentiment of the record. Making rainbows out of something painful. Paul \[Epworth\] added so much warmth and muscularity that it feels like you’re ending on a high. The song’s partly inspired by *Just Kids* by Patti Smith, and that idea of relationships being dissolved and wrecked by people’s unhealthy coping mechanisms.”

“Sometimes I’ll be in my own space, my own company, and that’s when I\'m really content,” Little Simz tells Apple Music. “It\'s all love, though. There’s nothing against anyone else; that\'s just how I am. I like doing my own thing and making my art.” The lockdowns of 2020, then, proved fruitful for the North London MC, singer, and actor. She wrestled writer’s block, revived her cult *Drop* EP series (explore the razor-sharp and diaristic *Drop 6* immediately), and laid grand plans for her fourth studio album. Songwriter/producer Inflo, co-architect of Simz’s 2019 Mercury-nominated, Ivor Novello Award-winning *GREY Area*, was tapped and the hard work began. “It was straight boot camp,” she says of the *Sometimes I Might Be Introvert* sessions in London and Los Angeles. “We got things done pronto, especially with the pace that me and Flo move at. We’re quite impulsive: When we\'re ready to go, it’s time to go.” Months of final touches followed—and a collision between rap and TV royalty. An interest in *The Crown* led Simz to approach Emma Corrin (who gave an award-winning portrayal of Princess Diana in the drama). She uses her Diana accent to offer breathless, regal addresses that punctuate the 19-track album. “It was a reach,” Simz says of inviting Corrin’s participation. “I’m not sure what I expected, but I enjoyed watching her performance, and wrote most of her words whilst I was watching her.” Corrin’s speeches add to the record’s sense of grandeur. It pairs turbocharged UK rap with Simz at her most vulnerable and ambitious. There are meditations on coming of age in the spotlight (“Standing Ovation”), a reunion with fellow Sault collaborator Cleo Sol on the glorious “Woman,” and, in “Point and Kill,” a cleansing, polyrhythmic jam session with Nigerian artist Obongjayar that confirms the record’s dazzling sonic palette. Here, Simz talks us through *Sometimes I Might Be Introvert*, track by track. **“Introvert”** “This was always going to intro the album from the moment it was made. It feels like a battle cry, a rebirth. And with the title, you wouldn\'t expect this to sound so huge. But I’m finding the power within my introversion to breathe new meaning into the word.” **“Woman” (feat. Cleo Sol)** “This was made to uplift and celebrate women. To my peers, my family, my friends, close women in my life, as well as women all over the world: I want them to know I’ve got their back. Linking up with Cleo is always fun; we have such great musical chemistry, and I can’t imagine anyone else bringing what she did to the song. Her voice is beautiful, but I think it\'s her spirit and her intention that comes through when she sings.” **“Two Worlds Apart”** “Firstly, I love this sample; it’s ‘The Agony and the Ecstasy’ by Smokey Robinson, and Flo’s chopped it up really cool. This is my moment to flex. You had the opener, followed by a nice, smoother vibe, but this is like, ‘Hey, you’re listening to a *rap* album.’” **“I Love You, I Hate You”** “This wasn’t the easiest song for me to write, but I\'m super proud that I did. It’s an opportunity for me to lay bare my feelings on how that \[family\] situation affected me, growing up. And where I\'m at now—at peace with it and moving on.” **“Little Q, Pt. 1 (Interlude)”** “Little Q is my cousin, Qudus, on my dad\'s side. We grew up together, but then there was a stage where we didn\'t really talk for some years. No bad blood, just doing different things, so when we reconnected, we had a real heart-to-heart—and I heard about all he’d been through. It made me feel like, ‘Damn, this is a blood relative, and he almost lost his life.’ I thank God he didn’t, but I thought of others like him. And I felt it was important that his story was heard and shared. So, I’m speaking from his perspective.” **“Little Q, Pt. 2”** “I grew up in North London and \[Little Q\] was raised in South, and as much as we both grew up in endz, his experience was obviously different to mine. Being a product of an environment or system that isn\'t really for you, it’s tough trying to navigate that.” **“Gems (Interlude)”** “This is another turning point, reminding myself to take time: ‘Breathe…you\'re human. Give what you can give, but don\'t burn out for anyone. Put yourself first.’ Just little gems that everyone needs to hear once in a while.” **“Speed”** “This track sends another reminder: ‘This game is a marathon, not a sprint. So pace yourself!’ I know where I\'m headed, and I\'m taking my time, with little breaks here and there. Now I know when to really hit the gas and also when to come off a bit.” **“Standing Ovation”** “I take some time to reflect here, like, ‘Wow, you\'re still here and still going. It’s been a slow burn, but you can afford to give yourself a pat on the back.’ But as well as being in the limelight, let\'s also acknowledge the people on the ground doing real amazing work: our key workers, our healers, teachers, cleaners. If you go to a toilet and it\'s dirty, people go in from 9 to 5 and make sure that shit is spotless for you, so let\'s also say thank you.” **“I See You”** “This is a really beautiful and poetic song on love. Sometimes as artists we tend to draw from traumatic times for great art, we’re hurt or in pain, but it was nice for me to be able to draw from a place of real joy in my life for this song. Even where it sits \[on the album\]: right in the center, the heart.” **“The Rapper That Came to Tea (Interlude)”** “This title is a play on \[Judith Kerr’s\] children\'s book *The Tiger Who Came to Tea*, and this is about me better understanding my introversion. I’m just posing questions to myself—I might not necessarily have answers for them, I think it\'s good to throw them out there and get the brain working a bit.” **“Rollin Stone”** “This cut reminds me somewhat of ’09 Simz, spitting with rapidness and being witty. And I’m also finding new ways to use my voice on the second half here, letting my evil twin have her time.” **“Protect My Energy”** “This is one of the songs I\'m really looking forward to performing live. It’s a stepper, and it got me really wanting to sing, to be honest. I very much enjoy being around good company, but these days I enjoy my personal space and I want to protect that.” **“Never Make Promises (Interlude)”** “This one is self-explanatory—nothing is promised at all. It’s a short intermission to lead to the next one, but at one point it was nearly the album intro.” **“Point and Kill” (feat. Obongjayar)** “This is a big vibe! It feels very much like Nigeria to me, and Obongjayar is one of my favorites at the moment. We recorded this in my living room on a whim—and I\'m very, very grateful that he graced this song. The title comes from a phrase used in Nigeria to pick out fish at the market, or a store. You point, they kill. But also metaphorically, whatever I want, I\'m going to get in the same way, essentially.” **“Fear No Man”** “This track continues the same vibe, even more so. It declares: ‘I\'m here. I\'m unapologetically me and I fear no one here. I\'m not shook of anyone in this rap game.’” **“The Garden (Interlude)”** “This track is just amazing musically. It’s about nurturing the seeds you plant. Nurture those relationships, and everything around you that\'s holding you down.” **“How Did You Get Here”** “I want everyone to know *how* I got here; from the jump, school days, to my rap group, Space Age. We were just figuring it out, being persistent. I cried whilst recording this song; it all hit me, like, ‘I\'m actually recording my fourth album.’ Sometimes I sit and I wonder if this is all really true.” **“Miss Understood”** “This is the perfect closer. I could have ended on the last track, easily, but, I don\'t know, it\'s kind of like doing 99 reps. You\'ve done 99, that\'s amazing, but you can do one more to just make it 100, you can. And for me it was like, ‘I\'m going to get this one in there.’”

“I don\'t think it\'s an incredible, incredible album, but I do think it\'s an honest portrayal of what we were like and what we sounded like when those songs were written,” Black Country, New Road frontman Isaac Wood tells Apple Music of his Cambridge post-punk outfit’s debut LP. “I think that\'s basically all it can be, and that\'s the best it can be.” Intended to capture the spark of their early years—and electrifying early performances—*For the First Time* is an urgent collision of styles and signifiers, a youthful tangling of Slint-ian post-rock and klezmer meltdowns, of lowbrow and high, Kanye and the Fonz, Scott Walker and “the absolute pinnacle of British engineering.” Featuring updates to singles “Sunglasses” and “Athens, France,” it’s also a document of their banding together after the public demise of a previous incarnation of the outfit, when all they wanted to do was be in a room with one another again, playing music. “I felt like I was able to be good with these people,” Wood says of his six bandmates. “These were the people who had taught me and enabled me to be a good musician. Had I played the record back to us then, I would be completely over the moon about it.” Here, Wood walks us through the album start to finish. **Instrumental** “It was the first piece we wrote. So to fit with making an accurate presentation of our sound or our journey as musicians, we thought it made sense to put one of the first things we wrote first.” **Athens, France** “We knew we were going to be rerecording it, so I listened back to the original and I thought about what opportunities I might take to change it up. I just didn\'t do the best job at saying the thing I was wanting to say. And so it was just a small edit, just to try and refine the meaning of the song. It wouldn’t be very fun if I gave that all away, but the simplest—and probably most accurate—way to explain it would be that the person whose perspective was on this song was most certainly supposed to be the butt of a joke, and I think it came across that that wasn\'t the case, and that\'s what made me most uncomfortable.” **Science Fair** “I’m not so vividly within this song; I’m more of an outsider. I have a fair amount of personal experience with science fairs. I come from Cambridge—and most of the band do as well—and there\'s many good science fairs and engineering fairs around there that me and my father would attend quite frequently. It’s a funny thing, something that I did a lot and never thought about until the minute that the idea for the song came into my head. It’s the sort of thing that’s omnipresent, but in the background. It\'s the same with talking about the Cirque du Soleil: Just their plain existence really made me laugh.” **Sunglasses** “It was a genuine realization that I felt slightly more comfortable walking down the street if I had a pair of sunglasses on. It wasn\'t necessarily meditating on that specific idea, but it was jotted down and then expanded and edited, expanded and messed around with, and then became what it was. Sunglasses exist to represent any object, those defense mechanisms that I recognize in myself and find in equal parts effective and kind of pathetic. Sometimes they work and other times they\'re the thing that leads to the most narcissistic, false, and ignorant ways of being. I just broke the pair that my fiancée bought for me, unfortunately. Snapped in half.” **Track X** “I wrote that riff ages and ages ago, around the time I first heard *World of Echo* by Arthur Russell, which is possibly my favorite record of all time. I was playing around with the same sort of delay effects that he was using, trying to play some of his songs on guitar, sort of translate them from the cello. We didn\'t play it for ages and ages, and then just before we recorded this album, we had the idea to resurrect it and put it together with an old story that I had written. It’s a love story—love and loss and all that\'s in between. It just made sense for it to be something quieter, calmer. And because it was arranged most recently, it definitely gives the most glimpse of our new material.” **Opus** “‘Opus’ and ‘Instrumental’ were written on the same day. We were in a room together without any music prepared, for the first time in a few months, and we were all feeling quite down. It was a highly emotional time, and I think the music probably equal parts benefits and suffers from that. It\'s rich with a fair amount of typical teenage angst and frustration, even though we were sort of past our teens by that point. I mean, it felt very strange but very, very good to be playing together again. It took us a little while to realize that we might actually be able to do it. It was just a desire to get going and to make something new for ourselves, to build a new relationship musically with each other and the world, to just get out there and play a show. We didn\'t really have our sights set particularly high—we just really wanted to play live at the pub.”

When IDLES released their third album, *Ultra Mono*, in September 2020, singer Joe Talbot told Apple Music that it was focused on being present and, he said, “accepting who you are in that moment.” On the Bristol band’s fourth record, which arrived 14 months later, that perspective turns sharply back to the past as Talbot examines his struggles with addiction. “I started therapy and it was the first time I really started to compartmentalize the last 20 years, starting with my mum’s alcoholism and then learning to take accountability for what I’d done, all the bad decisions I’d made,” he tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “But also where these bad decisions came from—as a forgiveness thing but way more as a responsibility thing. Two years sober, all that stuff, and I came out and it was just fluid, we \[Talbot and guitarist Mark Bowen\] both just wrote it and it was beautiful.” Talbot is unshrinkingly honest in his self-examination. Opener “MTT 420 RR” considers mortality via visceral reflections on a driving incident that the singer was fortunate to escape alive, before his experiences with the consuming cycle of addiction cut through the pneumatic riffs of “The Wheel.” There’s hope here, too. During soul-powered centerpiece “The Beachland Ballroom,” Talbot is as impassioned as ever and newly melodic (“It was a conversation we had, I wanted to start singing”). It’s a song where he’s on his knees but he can discern some light. “The plurality of it is that perspective of *CRAWLER*, the title,” he says. “Recovery isn’t just a beautiful thing, you have to go through a lot of processes that are ugly and you’ve got to look at yourself and go, ‘Yeah, you were not a good person to these people, you did this.’ That’s where the beauty comes from—afterwards you have a wider perspective of where you are. And also from other people’s perspectives, you see these things, you see people recovering or completely enthralled in addiction, and it’s all different angles. We wanted to create a picture of recovery and hope but from ugly and beautiful angles. You’re on your knees, some people are begging, some people are working, praying, whatever it is—you’ve got to get through it.” *CRAWLER* may be IDLES’ most introspective work to date, but their social and political focus remains sharp enough on the tightly coiled “The New Sensation” to skewer Conservative MP Rishi Sunak’s suggestion that some people, including artists and musicians, should abandon their careers and retrain in a post-pandemic world. With its rage and wit, its bleakness and hope, and its diversions from the band’s post-punk foundations into ominous electronica (“MTT 420 RR”), glitchy psych textures (“Progress”), and motorik rhythms butting up against free jazz (“Meds”), *CRAWLER* upholds Talbot’s earliest aims for the band. In 2009, he resolved to create something with substance and impact—an antidote to the bands he’d watched in Bristol and London. “They looked beautiful but bored,” he says. “They were clothes hangers, models. I was so sick of paying money to see bored people. Like, ‘What are you doing? Where’s the love?’ I was at a place where I needed an outlet, and luckily I found four brothers who saved my life. And the rest is IDLES.”

The intense process of making a debut album can have enduring effects on a band. Some are less expected than others. “It made my clothes smell for weeks afterwards,” Squid’s drummer/singer Ollie Judge tells Apple Music. During the British summer heatwave of 2020, the UK five-piece—Judge and multi-instrumentalists Louis Borlase, Arthur Leadbetter, Laurie Nankivell, and Anton Pearson—decamped to producer Dan Carey’s London studio for three weeks. There, Carey served them the Swiss melted-cheese dish raclette, hence the stench, and also helped the band expand the punk-funk foundations of their early singles into a capricious, questing set that draws on industrial, jazz, alt-rock, electronic, field recordings, and a Renaissance-era wind instrument called the rackett. The songs regularly reflect on disquieting aspects of modern life—“2010” alone examines greed, gentrification, and the mental-health effects of working in a slaughterhouse—but it’s also an album underpinned by the kindness of others. Before Carey hosted them in a COVID-safe environment at his home studio, the band navigated the restrictions of lockdown with the help of people living near Judge’s parents in Chippenham in south-west England. A next-door neighbor, who happens to be Foals’ guitar tech, lent them equipment, while a local pub owner opened up his barn as a writing and rehearsal space. “It was really nice, so many people helping each other out,“ says Borlase. “There’s maybe elements within the music, on a textural level, of how we wished that feel of human generosity was around a bit more in the long term.” Here, Borlase, Judge, and Pearson guide us through the record, track by track. **“Resolution Square”** Anton Pearson: “It’s a ring of guitar amps facing the ceiling, playing samples. On the ceiling was a microphone on a cord that swung around like a pendulum. So you get that dizzying effect of motion. It’s a bit like a red shift effect, the pitch changing as the microphone moves. We used samples of church bells and sounds from nature. It felt like a really nice thing to start with, kind of waking up.” Ollie Judge: “It sounds like cars whizzing by on the flyover, but it’s all made out of sounds from nature. So it’s playing to that push and pull between rural and urban spaces.” **“G.S.K.”** OJ: “I started writing the lyrics when I was on a Megabus from Bristol to London. I was reading *Concrete Island* by J. G. Ballard, and that is set underneath that same flyover that you go on from Bristol to London \[the Chiswick Flyover\]. I decided to explore the dystopic nature of Britain, I guess. It’s a real tone-setter, quite industrial and a bit unlike the sound world that we’ve explored before. Lots of clanging.” **“Narrator”** OJ: “It’s almost like a medley of everything we’ve done before: It’s got the punk-funk kind of stuff, and then newer industrial kind of sounds, and a foray into electronic sounds.” Louis Borlase: “It’s actually one of the freest ones when it comes to performing it. The big build-up that takes you through to the very end of the song is massively about texture in space, therefore it’s also massively about communication. That takes us back to the early days of playing in the Verdict \[jazz venue\] together, in Brighton, where we used to have very freeform music. It was very much about just establishing a tonality and a harmony and potentially a rhythm, and just kind of riding with it.” **“Boy Racers”** OJ: “It’s a song of two halves. The familiar, almost straightforward pop song, and then it ends in a medieval synth solo.” LB: “We had started working on it quite crudely, ready to start performing it on tour, in March 2020, just before lockdown. In lockdown, we started sending each other files and letting it develop via the internet. Just at the point where everything stops rhythmically and everything gets thrown up into the air—and enter said rackett solo—it’s the perfect depiction of when we were able to start seeing each other again. That whole rhythmic element stopped, and we left the focus to be what it means to have something that’s very free.” **“Paddling”** OJ: “The big, gooey pop centerpiece of the album. There’s a video of us playing it live from quite a few years ago, and it’s changed so much. We added quite a bit of nuance.” AP: “It was a combined effort between the three of us, lyrically. It started off about coming-of-age themes and how that related to readings about *The Wind in the Willows* and Mole—about things feeling scary when they’re new sometimes. That kind of naivety can trip you up. Then also about the whole theme of the book, about greed and consumerism, and learning to enjoy simple things. That book says such a beautiful thing about joy and how to get enjoyment out of life.” **“Documentary Filmmaker”** OJ: “It was quite Steve Reich-inspired, even to the point where when I played my girlfriend the album for the first time she said, ‘Oh, I thought that was Steve Reich. That was really nice.’” LB: “It started in a bedroom jam at Arthur’s family house. We had quite a lazy summer afternoon, no pressure in writing, and that’s preserved its way through to what it is on the album.” AP: “Sometimes we set out with ideas like that and they move into the more full-band setting. We felt was really important to keep this one in that kind of stripped-back nature.” **“2010”** OJ: “I think it’s a real shift towards future Squid music. It’s more like an alternative rock song than a post-punk band. It’s definitely a turning point: Our music has been known to be quite anecdotal and humorous in places, but this is quite mature. It doesn’t have a tongue-in-cheek moment.” LB: “Lyrically, it’s tackling some themes which are quite distressing and expose some of the problematic aspects of society. Trying to make that work, you’re owing a lot to the people involved, people that are affected by these issues, and you don’t want to make something that doesn’t feel truly thought about.” **“The Flyover”** AP: “It moulds really nicely into ‘Peel St.’ after it, which is quite fun—that slow morphing from something quite calm into something quite stressful. Arthur sent some questions out to friends of the band to answer, recorded on their phones. He multi-tracked them so there’s only ever like three people talking at one time. It’s just such a hypnotic and beautiful thing to listen to. Lots of different people talking about their lives and their perspectives.” **“Peel St.”** AP: “That’s the first thing we came up with when we met up in Chippenham, after having been separate for so long. It was this wave of excitement and joy. I don’t know why, when we’re all so happy, something like that comes out. That rhythmic pattern grew from those first few days, because it was really emotional.” LB: “It was joyful, but when we were all in that barn on the first day, I don’t think any of us were quite right. We called it ‘Aggro’ before we named it ‘Peel St.,’ because we would feel pretty unsettled playing it. It was a workout mentally and physically.” **“Global Groove”** OJ: “I got loads of inspiration from a retrospective on Nam June Paik—who’s like the godfather of TV art, or video installations—at the Tate. It’s a lot about growing up with the 24-hour news cycle and how unhealthy it is to be bombarded with mostly bad news—but then sometimes a nice story about an animal \[gets added\] on the end of the news broadcast. Growing up with various atrocities going on around you, and how the 24-hour news cycle must desensitize you to large-scale wars and death.” **“Pamphlets”** LB: “It’s probably the second oldest track on the album. The three of us were staying at Ollie’s parents’ house a couple of summers ago and it was the first time we bought a whiteboard. We now write music using a whiteboard, we draw stuff up, try and keep it visual. It also makes us feel quite efficient. ‘Pamphlets’ became an important part of our set, particularly finishing a set, because it’s quite a long blow-out ending. But when we brought it back to Chippenham last year, it had changed so much, because it had had so much time to have so many audiences responding to it in different ways. It’s very live music.”

'Flock’ is the record that Jane Weaver always wanted to make, the most genuine version of herself, complete with unpretentious Day-Glo pop sensibilities, wit, kindness, humour and glamour. A consciously positive vision for negative times, a brooding and ethereal creation. The album features an untested new fusion of seemingly unrelated compounds fused into an eco-friendly hum; pop music for post-new-normal times. Created from elements that should never date, its pop music reinvented. Still prevalent are the cosmic sounds, but ‘Flock’ is a natural rebellion to the recent releases which sees her decidedly move away from conceptual roots in favour of writing pop music. Produced on a complicated diet of bygone Lebanese torch songs, 1980's Russian Aerobics records and Australian Punk. Amongst this broadcast of glistening sounds is ‘The Revolution Of Super Visions’, an untelevised Mothership connection, with Prince floating by as he plays scratchy guitar; it also features a funky whack-a-mole bass line and synth worms. It underlines the discordant pop vibe that permeates ‘Flock’ and concludes on ‘Solarised’, a super-catchy, totally infectious apocalypse, a radio-friendly groove for last dance lovers clinging together in an effort to save themselves before the end of the night. The musician’s exposure to an abundance of lost records served as a reminder that you still feel like an outsider in this world and that by overcoming fears you can achieve artistic freedom. Jane Weaver continues to metamorphosise…

As they worked on their third album, Wolf Alice would engage in an exercise. “We liked to play our demos over the top of muted movie trailers or particular scenes from films,” lead singer and guitarist Ellie Rowsell tells Apple Music. “It was to gather a sense of whether we’d captured the right vibe in the music. We threw around the word ‘cinematic’ a lot when trying to describe the sound we wanted to achieve, so it was a fun litmus test for us. And it’s kinda funny, too. Especially if you’re doing it over the top of *Skins*.” Halfway through *Blue Weekend*’s opening track, “The Beach,” Wolf Alice has checked off cinematic, and by its (suitably titled) closer, “The Beach II,” they’ve explored several film scores’ worth of emotion, moods, and sonic invention. It’s a triumphant guitar record, at once fan-pleasing and experimental, defiantly loud and beautifully quiet and the sound of a band hitting its stride. “We’ve distilled the purest form of Wolf Alice,” drummer Joel Amey says. *Blue Weekend* succeeds a Mercury Prize-winning second album (2017’s restless, bombastic *Visions of a Life*), and its genesis came at a decisive time for the North Londoners. “It was an amazing experience to get back in touch with actually writing and creating music as a band,” bassist Theo Ellis says. “We toured *Visions of a Life* for a very long time playing a similar selection of songs, and we did start to become robot versions of ourselves. When we first got back together at the first stage of writing *Blue Weekend*, we went to an Airbnb in Somerset and had a no-judgment creative session and showed each other all our weirdest ideas and it was really, really fun. That was the main thing I’d forgotten: how fun making music with the rest of the band is, and that it’s not just about playing a gig every evening.” The weird ideas evolved during sessions with producer Markus Dravs (Arcade Fire, Coldplay, Björk) in a locked-down Brussels across 2020. “He’s a producer that sees the full picture, and for him, it’s about what you do to make the song translate as well as possible,” guitarist Joff Oddie says. “Our approach is to throw loads of stuff at the recordings, put loads of layers on and play with loads of sound, but I think we met in the middle really nicely.” There’s a Bowie-esque majesty to tracks such as “Delicious Things” and “The Last Man on Earth”; “Smile” and “Play the Greatest Hits” were built for adoring festival crowds, while Rowsell’s songwriting has never revealed more vulnerability than on “Feeling Myself” and the especially gorgeous “No Hard Feelings” (“a song that had many different incarnations before it found its place on the record,” says Oddie. “That’s a testament to the song. I love Ellie’s vocal delivery. It’s really tender; it’s a beautiful piece of songwriting that is succinct, to the point, and moves me”). On an album so confident in its eclecticism, then, is there an overarching theme? “Each song represents its own story,” says Rowsell. “But with hindsight there are some running themes. It’s a lot about relationships with partners, friends, and with oneself, so there are themes of love and anxiety. Each song, though, can be enjoyed in isolation. Just as I find solace in writing and making music, I’d be absolutely chuffed if anyone had a similar experience listening to this. I like that this album has different songs for different moods. They can rage to ‘Play the Greatest Hits,’ or they can feel powerful to ‘Feeling Myself,’ or ‘they can have a good cathartic cry to ‘No Hard Feelings.’ That would be lovely.”

In August 2019, New York singer-songwriter Cassandra Jenkins thought she had the rest of her year fully mapped out, starting with a tour of North America as a guitarist in David Berman’s newly launched project Purple Mountains. But when Berman took his own life that month, everything changed. “All of a sudden, I was just unmoored and in shock,” she tells Apple Music. “I really only spent four days with David. But those four days really knocked me off my feet.” For the next few months, she wrote as she reflected, obsessively collecting ideas and lyrics, as well as recordings of conversations with friends and strangers—cab drivers and art museum security guards among them. The result is her sophomore LP, a set of iridescent folk rock that came together almost entirely over the course of one week, with multi-instrumentalist Josh Kaufman in his Brooklyn studio. “I was trying to articulate this feeling of getting comfortable with chaos,” she says. “And learning how to be comfortable with the idea that things are going to fall apart and they\'re going to come back together. I had shed a lot of skin very quickly.” Here, Jenkins tells us the story of each song on the album. **Michelangelo** “I think sequencing the record was an interesting challenge because, to me, the songs feel really different from one another. ‘Michelangelo’ is the only one that I came in with that was written—I had a melody that I wanted to use and I thought, ‘Okay, Josh, let’s make this into a little rock song and take the guitar solo in the middle.’ That was the first song we recorded, so it was just our way of getting into the groove of recording, with what sounds like a familiar version of what I\'ve done in the past.” **New Bikini** “I was worried when I was writing it that it sounded too starry-eyed and a little bit naive, saying, ‘The water cures everything.’ I think it was this tension between that advice—from a lot of people with good intentions—and me being like, ‘Well, it\'s not going to bring this person back from the dead and it\'s not going to change my DNA and it\'s not going to make this person better.’” **Hard Drive** “I just love talking to people, to strangers. The heart of the song is people talking about the nature of things, but often, what they\'re doing is actually talking about themselves and expressing something about themselves. I think that every person that I meet has wisdom to give and it\'s just a matter of turning that key with people. Because when you turn it and you open that door, you can be given so much more than you ever expected. Really listening, being more of a journalist in my own just day-to-day life—rather than trying to influence my surroundings, just letting them hit me.” **Crosshairs** “You could look at this as a kind of role-playing song, which isn\'t explicitly sexual, but that\'s definitely one aspect of it. It’s the idea that when you\'re assuming a different role within yourself, it actually can open up chambers within you that are otherwise not seeing the light of day. I was looking at the parts of me that are more masculine, the parts of me that are explicitly feminine, and seeing where everything is in between, while also trying to do the same for someone else in my life.” **Ambiguous Norway** “The song is titled after one of David\'s cartoons, a drawing of a house with a little pinwheel on the top. It\'s about that moment where I was experiencing this grief of David passing away, where I was really saturated in it. I threw myself onto this island in Norway—Lyngør—thinking I could sort of leave that behind to a certain extent, and just realizing that it really didn\'t matter what corner of the planet I found myself on, I was still interacting with the impression of David\'s death and finding that there was all of these coincidences everywhere I went. I felt like I was in this wide-eyed part of the grieving process where it becomes almost psychedelic, like I was seeing meaning in everything and not able at all to just put it into words because it was too big and too expansive.” **Hailey** “It\'s challenging to write a platonic love song—it doesn\'t have all the ingredients of heartbreak or lust or drama that I think a lot of those songs have. It\'s much more simple than that. I just wanted to celebrate her and also celebrate someone who\'s alive now, who\'s making me feel motivated to keep going when things get tough, and to have confidence in myself, because that\'s a really beautiful thing and it\'s rare to behold. I think a lot of the record is mourning, and this was kind of the opposite.” **The Ramble** “I made these binaural recordings as I walked around and birdwatched in the morning, in April \[2020\], when it was pretty much empty. I was a stone\'s throw away from all the hospitals that were cropping up in Central Park, while simultaneously watching nature flourish in this incredible way. I recorded a guitar part and then I sent that to all of my friends around the country and said, ‘Just write something, send it back to me. Don\'t spend a lot of time on it.’ I wanted to capture the feeling that things change, but it’s nature\'s course to find its way through. Just to go out with my binoculars and be in nature and observe birds is my way of really dissolving and letting go of a lot of my fears and anxieties—and I wanted to give that to other people.”

Madvillain superfans will no doubt recall the Four Tet 2005 remix EP stuffed with inventive versions of cuts from the now-certified classic rap album *Madvillainy*. Coming a decade and a half later, *Sound Ancestors* sees Kieran Hebden link once again with iconic hip-hop producer Madlib, this time for a set of all-new material, the product of a years-long and largely remote collaboration process. With source material arranged, edited, and recontextualized by the UK-born artist, the album represents a truly unique shared vision, exemplified by the reggae-tinged boom-bap of “Theme De Crabtree” and the neo-soul-infused clatter of “Dirtknock.” Such genre blends turn these 16 tracks into an excitingly twisty journey through both men’s seemingly boundless creativity, leading to the lithe jazz-hop of “Road of the Lonely Ones” and the rugged B-boy business of “Riddim Chant.”

Over the course of her first four albums as The Weather Station, Toronto’s Tamara Lindeman has seen her project gradually blossom from a low-key indie-folk oddity into a robust roots-rock outfit powered by motorik rhythms and cinematic strings. But all that feels like mere baby steps compared to the great leap she takes with *Ignorance*, a record where Lindeman soundly promotes herself from singer-songwriter to art-rock auteur (with a dazzling, Bowie-worthy suit made of tiny mirrors to complete the transformation). It’s a move partly inspired by the bigger rooms she found herself playing in support of her 2017 self-titled release, but also by the creative stasis she was feeling after a decade spent in acoustic-strummer mode. “Whenever I picked up the guitar, I just felt like I was repeating myself,” Lindeman tells Apple Music. “I felt like I was making the same decisions and the same chord changes, and it just felt a little stale. I just really wanted to embrace some of this other music that I like.” To that end, Lindeman built *Ignorance* around a dream-team band, pitting pop-schooled players like keyboardist John Spence (of Tegan and Sara’s live band) and drummer Kieran Adams (of indie electro act DIANA) against veterans of Toronto’s improv-jazz scene, like saxophonist Brodie West and flautist Ryan Driver. The results are as rhythmically vigorous as they are texturally scrambled, with Lindeman’s pristine Christine McVie-like melodies mediating between the two. Throughout the record, Lindeman distills the biggest, most urgent issues of the early 2020s—climate change, social injustice, unchecked capitalism—into intimate yet enigmatic vignettes that convey the heavy mental toll of living in a world that seems to be slowly caving in from all sides. “With a lot of the songs on the record, it could be a personal song or it could be an environmental song,” Lindeman explains. “But I don\'t think it matters if it\'s either, because it\'s all the same feelings.” Here, Lindeman provides us with a track-by-track survey of *Ignorance*’s treacherous psychic terrain. **Robber** “It\'s a very strange thing to be the recipient of something that\'s stolen, which is what it means to be a non-Indigenous Canadian. We\'re all trying to grapple with the question of: What does it mean to even be here at all? We\'re the beneficiaries of this long-ago genocide, essentially. I think Canadians in general and people all over the world are sort of waking up to our history—so to sing \'I never believed in the robber\' sort of feels like how we all were taught not to see certain things. The first page in the history textbook is: ‘People lived here.’ And then the next 265 pages are all about the victors—the takers.” **Atlantic** “I was thinking about the weight of the climate crisis—like, how can you look out the window and love the world when you know that it is so threatened, and how that threat and that grief gets in the way of loving the world and being able to engage with it.” **Tried to Tell You** “Something I thought about a lot when I was making the album was how strange our society is—like, how we’ve built a society on a total lack of regard for biological life, when we are biological. Our value system is so odd—it\'s ahuman in this funny way. We\'re actually very soft, vulnerable creatures—we fall in love easily and our hearts are so big. And yet, so much of the way that we try to be is to turn away from everything that\'s soft and mysterious and instinctual about the way that we actually are. There\'s a distinct lack of humility in the way that we try to be, and it doesn\'t do us any good. So this just started out as a song about a friend who was turning away from someone that they were very clearly deeply in love with, but at the same time, I felt like I was writing about everyone, because everyone is turning away from things that we clearly deeply love.” **Parking Lot** “What\'s beautiful about birds is that they\'re everywhere, and they show up in our big, shitty cities, and they\'re just this constant reminder of the nonhuman perspective—like when you really watch a bird, and you try to imagine how it\'s perceiving the world around it and why it\'s doing what it does. For me, there\'s such a beauty in encountering the nonhuman, but also a sadness, and those two ideas are connected in the song.” **Loss** “This song started with that chord change and that repetition of \'loss is loss is loss is loss.\' So I stitched in a snapshot of a person—I don\'t know who—having this moment where they realize that the pain of trying to avoid the pain is not as bad as the pain itself. The deeper feeling beneath that avoidance is loss and sadness and grief, so when you can actually see it, and acknowledge that loss is loss and that it\'s real, you also acknowledge the importance of things. I took a quote from a friend of mine who was talking about her journey into climate activism, and she said, ‘At some point, you have to live as if the truth is true.’ I just loved that, so I quoted her in the song, and I think about that line a lot.\" **Separated** “With some of these songs, I\'m almost terrified by some of the lyrics that I chose to include—I\'m like, \'What? I said that?\' To be frank, I wrote this song in response to the way that people communicate on social media. There\'s so much commitment: We commit to disagree, we commit to one-upping each other and misunderstanding each other on purpose, and it\'s not dissimilar to a broken relationship. Like, there\'s a genuine choice being made to perpetuate the conflict, and I feel like that\'s not really something we like to talk about.” **Wear** “This one\'s a slightly older song. I think I wrote it when I was still out on the road touring a lot. And it just seemed like the most perfect, deep metaphor: ‘I tried to wear the world like some kind of garment.’ I\'m always really happy when I can hit a metaphor that has many layers to it, and many threads that I can pull out over the course of the song—like, the world is this garment that doesn\'t fit and doesn\'t keep you warm and you can\'t move in. And you just want to be naked, and you want to take it off and you want to connect, and yet you have to wear it. I think it speaks to a desire to understand the world and understand other people—like, \'Is everyone else comfortable in this garment, or is it just me that feels uncomfortable?\'” **Trust** “This song was written in a really short time, and that doesn\'t usually happen to me, because I usually am this very neurotic writer and I usually edit a lot and overthink. It\'s a very heavy song. And it\'s about that thing that\'s so hard to wrap your head around when you\'re an empathetic person: You want to understand why some people actively choose conflict, why they choose to destroy. I wasn\'t actually thinking about a personal relationship when I wrote this song; I was thinking about the world and various things that were happening at the time. I think the song is centered in understanding the softness that it takes to stand up for what matters, even when it\'s not cool.” **Heart** “Along with \'Robber,\' this was one of my favorite recording moments. It had a pretty loose shape, and there\'s this weird thing that I was obsessed with where the one chord is played through the whole song, and everything is constantly tying back to this base. I just loved what the band did and how they took it in so many different directions. This song really freaked me out \[lyrically\]. I was not comfortable with it. But I was talked into keeping it, and all for the better, because obviously, I do believe that the sentiments shared on the song—though they are so, so fucking soft!—are the best things that you can share.” **Subdivisions** “This was one of the first songs written before the record took shape in my mind and before it structurally came together. I think we recorded it in, like, an hour, and everyone\'s performance was just perfect. I like these big, soft, emotional songs, and from a craft perspective, I think it\'s one of my better songs. I\'ve never really written a chorus like that. I don\'t even feel like it\'s my song. I don\'t feel like I wrote it or sang it, but it just feels like falling deeper and deeper into some very soft place—which is, I think, the right way to end the record.”

“I’m not sure how I’m going to feel about people dancing to my own sadness,” David Balfe tells Apple Music. “When I was writing this at first, it was never meant for the public. I pressed 25 copies and gave them to my friends, who this record is about.” *For Those I Love* is about one of the Dublin artist’s friends in particular: his closest friend, collaborator and bandmate, the poet and musician Paul Curran—who died by suicide in February 2018. This extraordinary album is a love letter to that friendship. A self-produced, spoken-word masterpiece set to tenderly curated samples and exhilarating house beats, breaks and synths (“our youth was set to a backdrop of listening to house music in s\*\*t cars, so it made perfect sense to retell those stories with an electronic palette”), it’s also a tribute to working-class communities, art, grief and survival. “Growing up where we did in Dublin, my friends and I learned very young that life is a very fragile and temporary thing,” Balfe says. “We first navigated the world in survival mode, but we soon realized that you have to express love. Because it haunts you as a regret if you don’t. An expression of love could be the difference between somebody’s being here or not being here. For us, that’s where being that vocal about love came from. I hope that’s not rare.” Read on for Balfe’s track-by-track guide to his important, thrilling record. **I Have a Love** “I wrote 75 or 76 songs for this album—this was the 15th, and it was also the first one that actually made it onto the record. It set the tone for how I wanted it all to feel and sound and flow, with the density and the texture that I wanted. The vast majority of samples that made it on had a very weighted significance to myself and my friends—they were very complementary to or important within the singular relationships that I was writing about. Here, the opening piano chords are from Sampha’s \'(No One Knows Me) Like the Piano.\' It’s is a very important song for myself and Paul. It dominated so much of the soundtrack to our intimate moments. I had written the instrumental before Paul had passed away and it was already going to be a track about my relationship with him. I was very lucky that I got to play that instrumental for him before he passed, and I got to share some of the lyrics. They very much had to do with this endless love that we both had. After Paul passed, the weight of the song and the samples themselves took on quite a different life me, and allowed me to reframe how I was writing the lyrics. I revisited \'(No One Knows Me),\' and I revisited \[the song’s other sample\] \'Let Love Flow On\' by Sonya Spence. Despite having this disco heart, I’ve always found that to be a warm safety blanket of a song. A gorgeous reassurance of hope and love against the difficulties of live and tragedy. The main refrain—\'I have a love, and it never fades\' was written long before Paul passed, and I was very lucky to have been able to share with him. I think a lot of people have the impression that it was something I had written in response to his death, but it wasn’t. It was a response to our friendship and 13 years of being inseparable. It’s quite curious and tragic that it held so much more weight in the aftermath. So I rewrote the whole history of that song and the whole history of our life around that refrain afterwards. It’s a strange song for me.” **You Stayed / To Live** “This is a song that’s very much rooted in storytelling. So many of my relationships with my friends involved fields and barren wasteland—hanging out and spending time just being together, discussing and planning our ideas. It was rare to walk into these areas without there being a fire of some kind. I’m still entranced by it—I find even the visual of fire to be very intoxicating. Anyway, most of the record was made in the shed at my ma’s—but this was made up in the box bedroom. It was a Thursday night after training, and I was laying on the bed writing about this time that myself and Paul stole a couch and walked it over the motorway to this field at three in the morning, intending to set it on fire the next day and film it. We woke up the next morning and the couch had already been set on fire. There’s something magic about that field—time does not work in a linear fashion there. As I was writing the song, one of the cars across the road got set on fire—over a debt, I found out. There are so many things about the recording of this album that has made me rethink how I engage with the world in regard to fate, or observations of spirituality. And I get it: everything holds this other significance when you’ve gone through that kind of tragedy, and you read into things as a source of comfort more than anything. And you allow yourself to be enchanted by it. Really, of course, it’s all just chance.” **To Have You** “This is built around ‘Everything I Own’ by Barbara Mason. The start of the track also has this audio clip from when the band I was in with Paul \[Burnt Out\] were filming the video for a track called ‘Dear James,’ and the song continues from there. We wanted to have this atmospheric smoke bellowing out of our bins in the lane behind my house. One of my best mates, Robbie, was like, ‘I can make a smoke bomb out of tin foil and ping pong balls.’ And we did it. For us, it was just this moment of such monumental success. It was like this really traditional, hands-on success of our labor. I wanted to bring a reminder for myself and my friends of the things that we had done together and felt so much collective beauty for. We’re never going to lose that memory now. This is also the only song on the album that includes my harp playing, which has allowed me to not feel guilty about buying a harp in the first place and not following through with learning how to play it. Paul was always like, ‘You’re a f\*\*king lunatic for buying that. But deadly, cool. Go for it.’” **Top Scheme** “The synth patch that I used is something I built years and years ago for a project that I did with one of my best mates, Pamela \[Connolly\], who’s now in a great band called Pillow Queens. We made music together in my ma’s shed for years for a project called Mothers and Fathers, and I wanted to bring a nod to that—it was important to me that I acknowledge so many of the different parts of my shared musical history with my friends for this album. Myself and Paul also had plans to start a separate project called Top Scheme, which was going to involve biting social commentary over some electronic, very aggressive, off-grid punk. We’d started making demos, but kept putting it off to focus on Burnt Out. I wanted to write a spiritual successor to that project and was very conscious where it would fit into the record. The song starts the curve from speaking very much about the love that we all shared together, into capturing about the worlds we grew up in—with this song speaking very specifically about the economic and social inequality that we faced being in a 1990s’ working-class community. It also speaks about the worlds we started to move into—when the geography of your world opens and suddenly you feel that sense of alienation that you once felt as a young child. You might be experiencing an economic disparity or a social divide that you’re unable to bridge. You hear people absolutely dehumanize others and reduce people down to scumbags based on their economic standing or, particularly as this song speaks about, really punishing people verbally for being addicts. Stripping them of their humanity, not caring about the sickness that ails them and seeing them as a plague. Just seeing them as a plague. This song speaks to that anger and disassociation—but there’s also supposed to be a very dark humor across it.” **The Myth / I Don’t** “This is the darkest moment on the record, and it’s the most difficult one to revisit because I am very much walking back into a mental and physical space that I’ve fortunately recovered from. It talks about where I was at before I had access to therapy and medication, then when I did and was trying to justify the exorbitant cost of dealing both those things—trying to value your own health over economic stability. It was very important that the music was sonically intoxicating. It spirals and I tried to make its density change and shift over time—with the shape of each sound morphing slowly and sometimes frantically towards its peak. I wanted it to feel like the same chaos, discomfort, and internal fear I felt during that period, but also capture the same drive toward this one singular end point. It needed to move towards this sonic oblivion at the end, because that’s what I was seeking at that point in my life. It’s also worth noting that for all the darkness that that song does bring, the times where I’ve gotten to perform it have probably been the most giving and actually traditionally cathartic things that I’ve been able to experience.” **The Shape of You** “Some of the samples took months to clear, but the Smokey Robinson one here went through like clockwork, overnight. I don’t know why, I didn’t ask why, I don’t need to know why. It’s a defining moment on the record for me—I listened to ‘The Tracks of My Tears’ when everything was going to s\*\*t and I felt heard in somebody else’s music, and suddenly understood that within my own music I could have somebody speak for me with an elegance that I would never be able to get. The beauty of sampling is being able to be intelligent enough to recognize when the choice to use other people who have walked that ground before is the right one. The lyrics cover me breaking my leg at a Belgian punk festival in 2007 and experiencing this terrifying, very chaotic time—before the relief and beauty and safety I felt when I saw my best friend arrive at the hospital. Everything that could possibly go wrong had gone wrong, but your best mate is there beside you, and you suddenly feel like it’s all going to be OK—and that you might even find some value in the chaos of it all.” **Birthday / The Pain** “One of the important things about this track is the juxtaposition of its make-up. It was quite a methodical choice. I understood that if I was to write about something like a dead body on bricks being found on my street while I was six years old with the sonic palette you would usually anticipate, then it would never have the comfort level for people to engage with that story. It’s a little bit of a cheat in order to allow people to find an entry point into the reality of that kind of world. The song’s built around a sample from ‘She Won’t be Gone Long’ by The Sentiments. It’s a slow dance, that song, and I find it to be quite a comfort to fall into the rhythm of it. The other special part of the song is the inclusion of crowd chanting at the start—from a specific game at Tolka Park, where our \[soccer\] team, Shelbourne FC, play. It was the first match of the season after Paul had passed and we were scattering his ashes that night on the pitch after the game. It was one of those games where you channel everything you have left in your life into those 90 minutes, into that jersey. It was 3-2 Shels in the end, with a 93rd minute penno. It’s all of us and the fans chanting, recorded on my phone. It was important to be able to bring the importance of that audio, that team, those friends and those strangers onto the record.” **You Live / No One Like You** “I think this is the best song, musically. It has all the warmth and texture that I want in a piece of music. I wasn’t trying to write pop anthems here—and that’s nothing against great pop anthems at all—because you can get so much into the weeds, the maths and the make-up of a song that way. But really it’s my favorite because it’s a song where I get to most clearly speak about my greatest love: my friends, and the survival that we’ve had together. It’s the song I get to most directly speak about them by name and channel years and years of friendship into this one moment. It’s therefore the song that gives me the most hope. And it gave me the most hope when I recorded it, too. It’s a lot easier to feel affected by something when you observe it than when you live it, I think, and to see my friends so emotionally invested and elated when they see and hear themselves immortalized, that’s where the value lies for me. It’s also nice to be able to revisit and revel in so many of monoliths of Irish culture—stemming back to people like John B. Keane and Brendan Behan. The song is very much a place of warmth, where I can go to remember what’s good, what’s left and what I value still.” **Leave Me Not Love** “I felt it was important to me to be able to close the book on this record and bring the listener back around to its inception. To really focus on that eternal return to the same, coming back to the original notes and scale that open the album. Where this track moves in quite a different direction to the others is at the end. It’s perhaps the only time where I unapologetically express something without hope. I turn back to the reality that I lived at the time, which was something explicitly void of hope and embedded in pain. I felt it would have been disingenuous of me not to bring the album back to the really graphic darkness that’s still there. I think I’m responsible enough to offer pockets and avenues that I have found to escape it, while stripping away any pretense and present the reality of that grief. What follows is ‘Cryin’ Like a Baby’ by Jackson C. Frank, which is a song that was very important to Paul and I, and speaks very directly, with a finesse I couldn’t have found by myself, to the days directly after Paul’s passing. It was the only way to end the record.”