NPR Music's 50 Best Albums of 2022

We ranked our 50 favorite records of the year, from hip-hop to classical and everything in between.

Published: December 12, 2022 10:00

Source

Unique, strong, and sexy—that’s how Beyoncé wants you to feel while listening to *RENAISSANCE*. Crafted during the grips of the pandemic, her seventh solo album is a celebration of freedom and a complete immersion into house and dance that serves as the perfect sound bed for themes of liberation, release, self-assuredness, and unfiltered confidence across its 16 tracks. *RENAISSANCE* is playful and energetic in a way that captures that Friday-night, just-got-paid, anything-can-happen feeling, underscored by reiterated appeals to unyoke yourself from the weight of others’ expectations and revel in the totality of who you are. From the classic four-on-the-floor house moods of the Robin S.- and Big Freedia-sampling lead single “BREAK MY SOUL” to the Afro-tech of the Grace Jones- and Tems-assisted “MOVE” and the funky, rollerskating disco feeling of “CUFF IT,” this is a massive yet elegantly composed buffet of sound, richly packed with anthemic morsels that pull you in. There are soft moments here, too: “I know you can’t help but to be yourself around me,” she coos on “PLASTIC OFF THE SOFA,” the kind of warm, whispers-in-the-ear love song you’d expect to hear at a summer cookout—complete with an intricate interplay between vocals and guitar that gives Beyoncé a chance to showcase some incredible vocal dexterity. “CHURCH GIRL” fuses R&B, gospel, and hip-hop to tell a survivor’s story: “I\'m finally on the other side/I finally found the extra smiles/Swimming through the oceans of tears we cried.” An explicit celebration of Blackness, “COZY” is the mantra of a woman who has nothing to prove to anyone—“Comfortable in my skin/Cozy with who I am,” ” Beyoncé muses on the chorus. And on “PURE/HONEY,” Beyoncé immerses herself in ballroom culture, incorporating drag performance chants and a Kevin Aviance sample on the first half that give way to the disco-drenched second half, cementing the song as an immediate dance-floor favorite. It’s the perfect lead-in to the album closer “SUMMER RENAISSANCE,” which propels the dreamy escapist disco of Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” even further into the future.

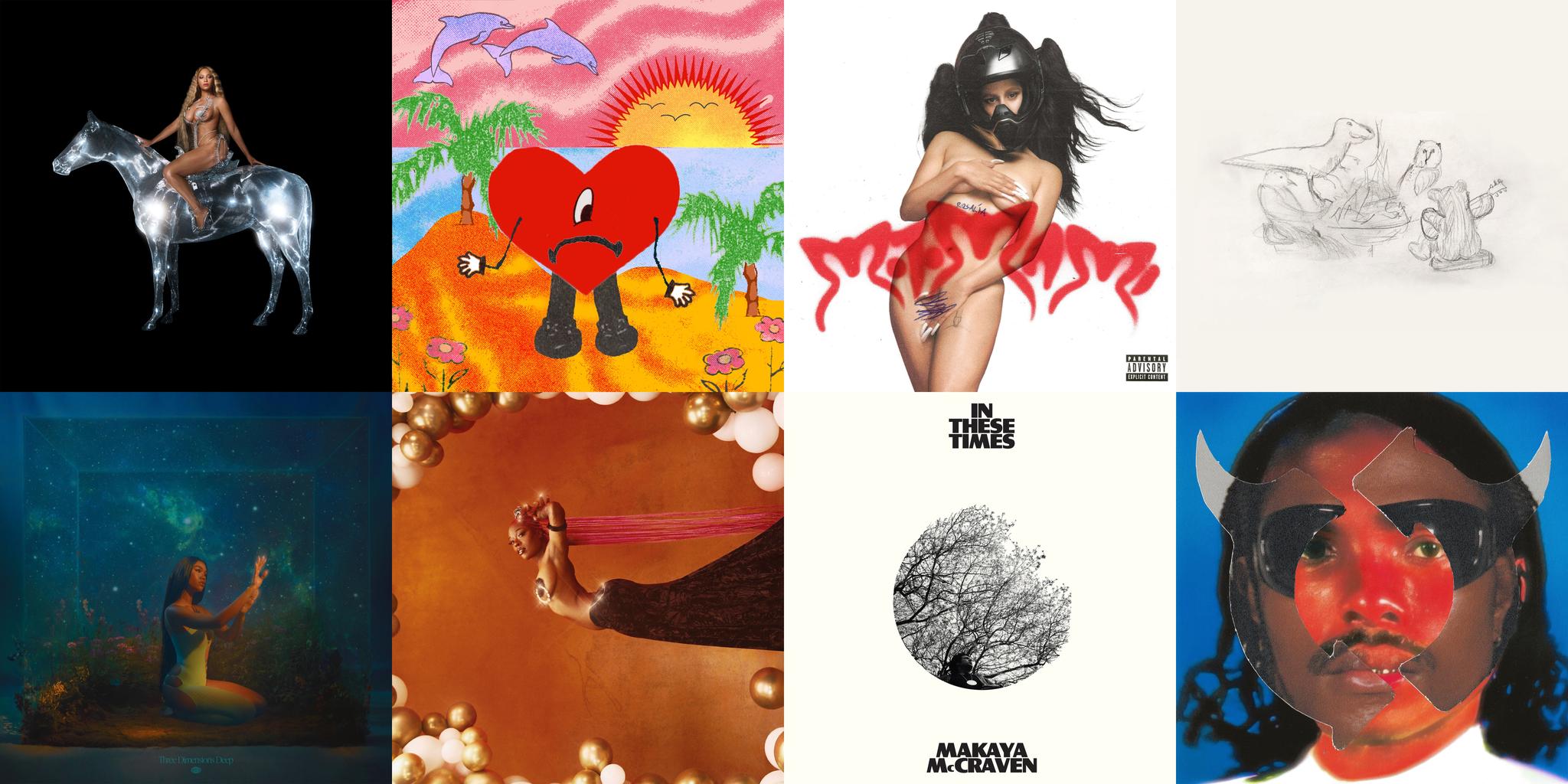

“I like to prepare myself and prepare the surroundings to work my music,” Bad Bunny tells Apple Music about his process. “But when I get a good idea that I want to work on in the future, I hold it until that moment.” After he blessed his fans with three projects in 2020, including the forward-thinking fusion effort *EL ÚLTIMO TOUR DEL MUNDO*, one could forgive the Latin superstar for taking some time to plan his next moves, musically or otherwise. Somewhere between living out his kayfabe dreams in the WWE and launching his acting career opposite the likes of Brad Pitt, El Conejo Malo found himself on the beach, sipping Moscow Mules and working on his most diverse full-length yet. And though its title and the cover’s emoting heart mascot might suggest a shift into sad-boy mode, *Un Verano Sin Ti* instead reveals a different conceptual aim as his ultimate summer playlist. “It\'s a good vibe,” he says. “I think it\'s the happiest album of my career.” Recorded in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, the album features several cuts in the same elevated reggaetón mode that largely defined *YHLQMDLG*. “Efecto” and “Un Ratito” present ideal perreo opportunities, as does the soon-to-be-ubiquitous Rauw Alejandro team-up “Party.” Yet, true to its sunny origins, *Un Verano Sin Ti* departs from this style for unexpected diversions into other Latin sounds, including the bossa nova blend “Yo No Soy Celoso” and the dembow hybrid “Tití Me Preguntó.” He embraces his Santo Domingo surroundings with “Después De La Playa,” an energizing mambo surprise. “We had a whole band of amazing musicians,” he says about making the track with performers who\'d typically play on the streets. “It\'s part of my culture. It\'s part of the Caribbean culture.” With further collaborations from familiars Chencho Corleone and Jhayco, as well as unanticipated picks Bomba Estéreo and The Marías, *Un Verano Sin Ti* embodies a wide range of Latin American talent, with Bad Bunny as its charismatic center.

“I literally don’t take breaks,” ROSALÍA tells Apple Music. “I feel like, to work at a certain level, to get a certain result, you really need to sacrifice.” Judging by *MOTOMAMI*, her long-anticipated follow-up to 2018’s award-winning and critically acclaimed *EL MAL QUERER*, the mononymous Spanish singer clearly put in the work. “I almost feel like I disappear because I needed to,” she says of maintaining her process in the face of increased popularity and attention. “I needed to focus and put all my energy and get to the center to create.” At the same time, she found herself drawing energy from bustling locales like Los Angeles, Miami, and New York, all of which she credits with influencing the new album. Beyond any particular source of inspiration that may have driven the creation of *MOTOMAMI*, ROSALÍA’s come-up has been nothing short of inspiring. Her transition from critically acclaimed flamenco upstart to internationally renowned star—marked by creative collaborations with global tastemakers like Bad Bunny, Billie Eilish, and Oneohtrix Point Never, to name a few—has prompted an artistic metamorphosis. Her ability to navigate and dominate such a wide array of musical styles only raised expectations for her third full-length, but she resisted the idea of rushing things. “I didn’t want to make an album just because now it’s time to make an album,” she says, citing that several months were spent on mixing and visuals alone. “I don’t work like that.” Some three years after *EL MAL QUERER*, ROSALÍA’s return feels even more revolutionary than that radical breakout release. From the noisy-yet-referential leftfield reggaetón of “SAOKO” to the austere and *Yeezus*-reminiscent thump of “CHICKEN TERIYAKI,” *MOTOMAMI* makes the artist’s femme-forward modus operandi all the more clear. The point of view presented is sharp and political, but also permissive of playfulness and wit, a humanizing mix that makes the album her most personal yet. “I was like, I really want to find a way to allow my sense of humor to be present,” she says. “It’s almost like you try to do, like, a self-portrait of a moment of who you are, how you feel, the way you think.\" Things get deeper and more unexpected with the devilish-yet-austere electronic punk funk of the title track and the feverish “BIZCOCHITO.” But there are even more twists and turns within, like “HENTAI,” a bilingual torch song that charms and enraptures before giving way to machine-gun percussion. Add to that “LA FAMA,” her mystifying team-up with The Weeknd that fuses tropical Latin rhythms with avant-garde minimalism, and you end up with one of the most unique artistic statements of the decade so far.

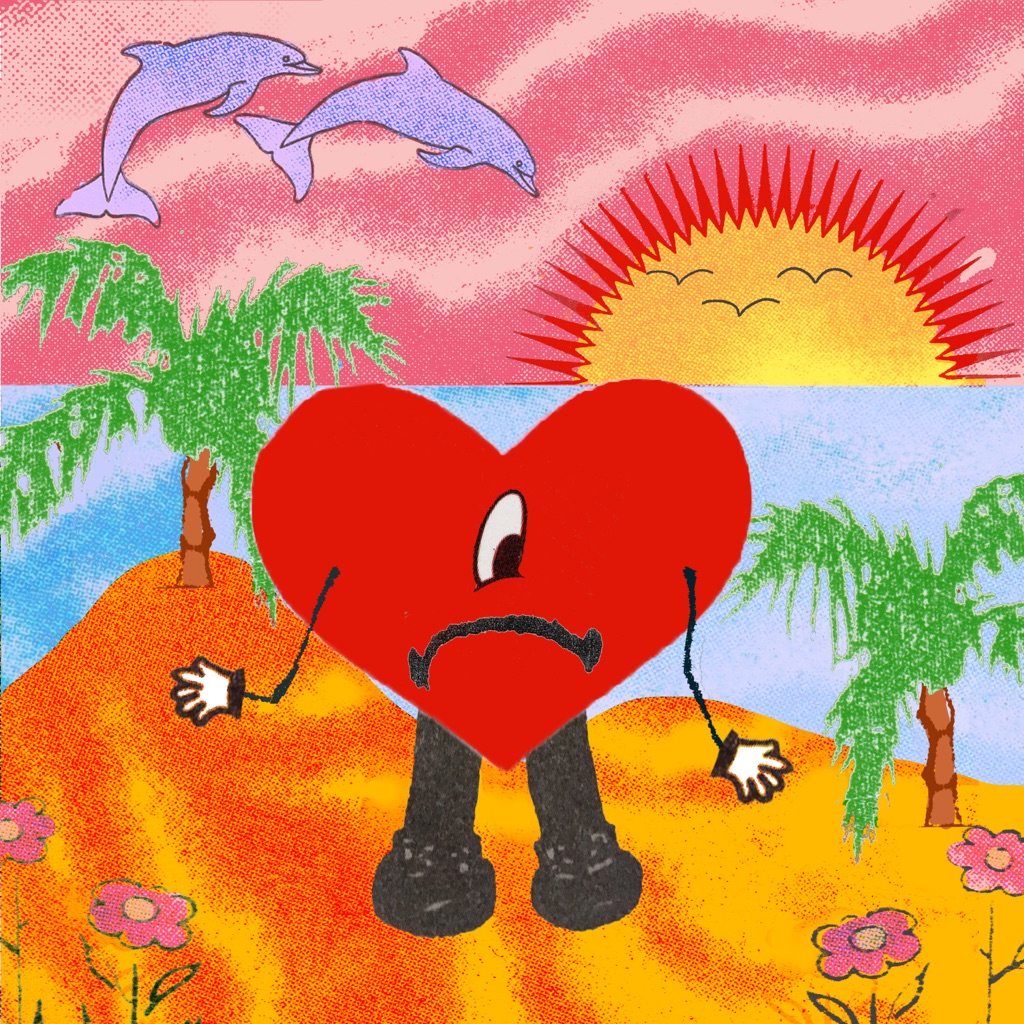

Like its title suggests, *Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe in You* continues Big Thief’s shift away from their tense, early music toward something folkier and more cosmically inviting. They’ve always had an interest in Americana, but their touchpoints are warmer now: A sweetly sawing fiddle (“Spud Infinity”), a front-porch lullaby (“Dried Roses”), the wonder of a walk in the woods (“Promise Is a Pendulum”) or comfort of a kitchen where the radio’s on and food sizzles in the pan (“Red Moon”). Adrianne Lenker’s voice still conveys a natural reticence—she doesn’t want to believe it’s all as beautiful as it is—but she’s also too earnest to deny beauty when she sees it.

Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe in You is a sprawling double-LP exploring the deepest elements and possibilities of Big Thief. To truly dig into all that the music of Adrianne Lenker, Max Oleartchik, Buck Meek, and James Krivchenia desired in 2020, the band decided to write and record a rambling account of growth as individuals, musicians, and chosen family over 4 distinct recording sessions. In Upstate New York, Topanga Canyon, The Rocky Mountains, and Tucson, Arizona, Big Thief spent 5 months in creation and came out with 45 completed songs. The most resonant of this material was edited down into the 20 tracks that make up DNWMIBIY, a fluid and adventurous listen. The album was produced by drummer James Krivchenia who initially pitched the recording concept for DNWMIBIY back in late 2019 with the goal of encapsulating the many different aspects of Adrianne’s songwriting and the band onto a single record. In an attempt to ease back into life as Big Thief after a long stretch of Covid-19 related isolation, the band met up for their first session in the woods of upstate New York. They started the process at Sam Evian’s Flying Cloud Recordings, recording on an 8-track tape machine with Evian at the knobs. It took a while for the band to realign and for the first week of working in the studio, nothing felt right. After a few un-inspired takes the band decided to take an ice-cold dip in the creek behind the house before running back to record in wet swimsuits. That cool water blessing stayed with Big Thief through the rest of the summer and many more intuitive, recording rituals followed. It was here that the band procured ‘Certainty’ and ‘Sparrow’. For the next session in Topanga Canyon, California, the band intended to explore their bombastic desires and lay down some sonic revelry in the experimental soundscape-friendly hands of engineer Shawn Everett. Several of the songs from this session lyrically explore the areas of Lenker’s thought process that she describes as “unabashedly as psychedelic as I naturally think,” including ‘Little Things’, which came out of this session. The prepared acoustic guitars and huge stomp beat of today’s ‘Time Escaping’ create a matching, otherworldly backdrop for the subconscious dream of timeless, infinite mystery. When her puppy Oso ran into the vocal booth during the final take of the song, Adrianne looked down and spoke “It’s Music!” to explain in the best terms possible the reality of what was going on to the confused dog. “It’s Music Oso!” The third session, high in the Colorado Rockies, was set up to be a more traditional Big Thief recording experience, working with UFOF and Two Hands engineer Dom Monks. Monks' attentiveness to song energies and reverence for the first take has become a huge part of the magic of Thief’s recent output. One afternoon in the castle-like studio, the band was running through a brand new song ‘Change’ for the first time. Right when they thought it might be time to do a take, Monks came out of the booth to let them know that he’d captured the practice and it was perfect as it was. The final session, in hot-as-heaven Tucson, Arizona, took place in the home studio of Scott McMicken. The several months of recording had caught up to Big Thief at this point so, in order to bring in some new energy, they invited long-time friend Mat Davidson of Twain to join. This was the first time that Big Thief had ever brought in a 5th instrumentalist for such a significant contribution. His fiddle, and vocals weave a heavy presence throughout the Tucson tracks. If the album's main through-line is its free-play, anything-is-possible energy, then this environment was the perfect spot to conclude its creation — filling the messy living room with laughter, letting the fire blaze in the backyard, and ripping spontaneous, extended jams as trains whistled outside. All 4 of these sessions, in their varied states of fidelity, style, and mood, when viewed together as one album seem to stand for a more honest, zoomed-out picture of lived experience than would be possible on a traditional, 12 song record. This was exactly what the band hoped would be the outcome of this kind of massive experiment. When Max’s mom asked on a phone call what it feels like to be back together with the band playing music for the first time in a year, he described to the best of abilities: “Well it’s like, we’re a band, we talk, we have different dynamics, we do the breaths, and then we go on stage and suddenly it feels like we are now on a dragon. And we can’t really talk because we have to steer this dragon.” The attempt to capture something deeper, wider, and full of mystery, points to the inherent spirit of Big Thief. Traces of this open-hearted, non-dogmatic faith can be felt through previous albums, but here on Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You lives the strongest testament to its existence.

Learning to channel her intensity in lockdown was where Amber Mark began to fuse together ideas for her much-anticipated debut album, *Three Dimensions Deep*. “It was like putting pieces of a puzzle together,” the singer-songwriter tells Apple Music. “I had these songs. I didn’t have a concept or know exactly where I wanted to go with it all. So, on a paper to-go bag, from some food I had got delivered, I began to section it out into three clear parts.” For her deeply ruminative record, Mark soars through a galaxy of stirring anthems, helmed primarily by producer Julian Bunetta (a key part of One Direction’s hitmaking machine). “He’s my sensei,” she says, “and one of the only producers that I work with. My anxiety means I tend to make music by myself, but I left my comfort zone for this album. I used to be very against the idea of writing camps, but trusted Julian, and agreed to do one, which was so amazing.” On her endearing quest for healing, Mark embraces stages of grief (“One”), loss (“Healing Hurts”), and deep insecurity (“On & On”), advancing her sound and herself under the sharp light of futurist-feel R&B. “There’s been so much growth involved whilst making this album,” she says. “Just through the different points in my life—losing my mother, moving around. But since 2020, I’ve just been seeing the world differently.” Read on for her insights on each track from her debut album. **“One”** “I started really questioning myself at the start of 2019. You go into business with others, and you won’t always agree on things. So, this song initially came from a state of anger; I was angry, and I wanted to get it out. I’ve been attracted to the idea of rap-singing more, and lyrically, this is the perfect song to dip my toe in with and experiment.” **“What It Is”** “I’m a sucker for big, very in-your-face harmonies. I had just seen the Bee Gees film \[*The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend A Broken Heart*\] and was so inspired by their journey. I remember writing this in one day. It’s a very bold song for me, and it started with writing out what this album means, conceptually.” **“Most Men”** “I wanted to express on the conversations you have with friends, trying to console them after a breakup, after something fucked up went down. And it’s always advice that I give to myself: ‘You need to be able to find happiness on your own—find the joy of being alone in these moments.’” **“Healing Hurts”** “I had just gone through a breakup, and I’m kind of processing on this song. After my mom passed away, that period showed me that time is the ultimate healer. And, as I know that, I know I’ll move on from this and get over the heartbreak. But right now, I’m in my bed, and I’m emotional!” **“Bubbles”** “This is also quite specific to the breakup—the aftermath. ‘Push those feelings aside, go out, and have fun.’ We wrote this at the \[writing\] retreat—where we all became close really quickly. We had dinners and got to know each other. It was like taking a vacation with great friends, except they would all be doing tequila shots. I used to, in my late teens, early twenties, but the idea doesn’t appeal to me anymore. I’m *always* down for a glass of bubbles, though, and somehow that became the joke of the trip.” **“Softly”** “When I was younger, living in Nepal, I had a very, very intense Craig David obsession. The beauty stores sold bootleg CDs there, and I bought his first two albums. I heard \[2001 single\] ‘Rendezvous’ quite recently on a summer day in New York and fell in love with it again. That synthesized harp is such a big staple of the early-’00s sound. I was like, ‘I need to sample this shit! We have to bring this back.’” **“FOMO”** “I was starting to have a little bit of cabin fever whilst \[writing\], a little frustrated at not getting anywhere. Looking at my friend’s \[Instagram\] Stories—they’re out, having fun, doing shit, and I’m missing all these amazing opportunities to be with them. So, I ended up getting inspiration from that—staying home and wrote this song about it.” **“Turnin’ Pages”** “This is where we really start to address my inner turmoil. This is the next chapter.” **“Foreign Things”** “Because the feeling of running away and leaving life behind is something that’s *so* tempting—this is about being faced with those problems, head-on, when you can longer hide or escape from them.” **“On & On”** “This song is a long-standing favorite of mine on the album. This touches on a lot of old insecurities and the ways I was dealing with them, which was not working. So, in need of a sign, this is where my mom comes into play: She would always say, ‘You have to surrender to the issues that you’re dealing with.’” **“Out of This World”** “This is the introduction to section three, essentially. Another ‘mom’ song, but here, things start getting a little spacey, sonically. The song is from her perspective, and it’s her talking to me, trying to console me.” **“Cosmic”** “I love playing with the idea of higher dimensions, associating them with the afterlife or the soul, because so many scientists have theories that prove they exist. They have the math for it but can’t portray it. So, I’m tapping more into the spirituality of science here.” **“Darkside”** “OK, I am *obsessed* with super-cheesy ’80s sounds, especially the really wet snares. And I was inspired by a really beautiful song I Shazamed in my yoga class. I went home, sampled it, and that was the start of this track. In my head, the approach was, ‘How can I make this sound like a really weird Prince, Phil Collins, and Michael Jackson love child?’” **“Worth It”** “I wrote this after releasing \[2020 single\] ‘Generous.’ People loved it, but I also received comments like, ‘Ah, it’s a different sound!’ ‘It’s not the same Amber Mark. I miss \[2017 EP\] *3:33am* Amber.’ So, I made a beat, thinking, ‘Oh, y’all want old Amber Mark? Fuck y’all. I’m going to make a beat that sounds exactly like her.’ I was giving them what they wanted…in an angry way.” **“Competition”** “This is another from a writing camp. On one of the nights, we decided to separate into teams and play a game. We had to write a song in 30 minutes, and I was also the judge, which was weird, as I was playing. But this song we ended up choosing as the best. It’s all about how it’s not actually competition. Wouldn’t it be better if we all work together?” **“Bliss”** “This is the comedown from the out-of-body experience, sonically. It’s about that euphoric state that you never even imagined possible. I was really falling in love at the time we wrote this. I’d never experienced anything like it. I wanted to talk about it. I mean, I didn’t even know this stage even existed.” **“Event Horizon”** “We were in mixing mode \[on the album\] when I wrote this. A really close friend of mine, Lincoln Bliss, sent me some stuff he had worked on to a BPM; I ask all my really talented musician friends to just send me shit I can try to make a beat from. He wrote this beautiful guitar riff that sounded like a lullaby. Normally, I sing gibberish for a few hours before I start writing. I tried to come up with the melody, but I wanted it to feel like a dream state. So, I’m also musing on some key questions I have about the universe. And finally, I ask, ‘What is the end when there is no time?’”

Brittney Parks’ *Athena* was one of the more interesting albums of 2019. *Natural Brown Prom Queen* is better. Not only does Parks—aka the LA-based singer, songwriter, and violinist Sudan Archives—sound more idiosyncratic, but she’s able to wield her idiosyncrasies with more power and purpose. It’s catchy but not exactly pop (“Home Maker”), embodied but not exactly R&B (“Ciara”), weird without ever being confrontational (“It’s Already Done”), and it rides the line between live sound and electronic manipulation like it didn’t exist. She wants to practice self-care (“Selfish Soul”), but she also just wants to “have my titties out” (“NBPQ \[Topless\]”), and over the course of 55 minutes, she makes you wonder if those aren’t at least sometimes the same thing. And the album’s sheer variety isn’t so much an expression of what Parks wants to try as the multitudes she already contains.

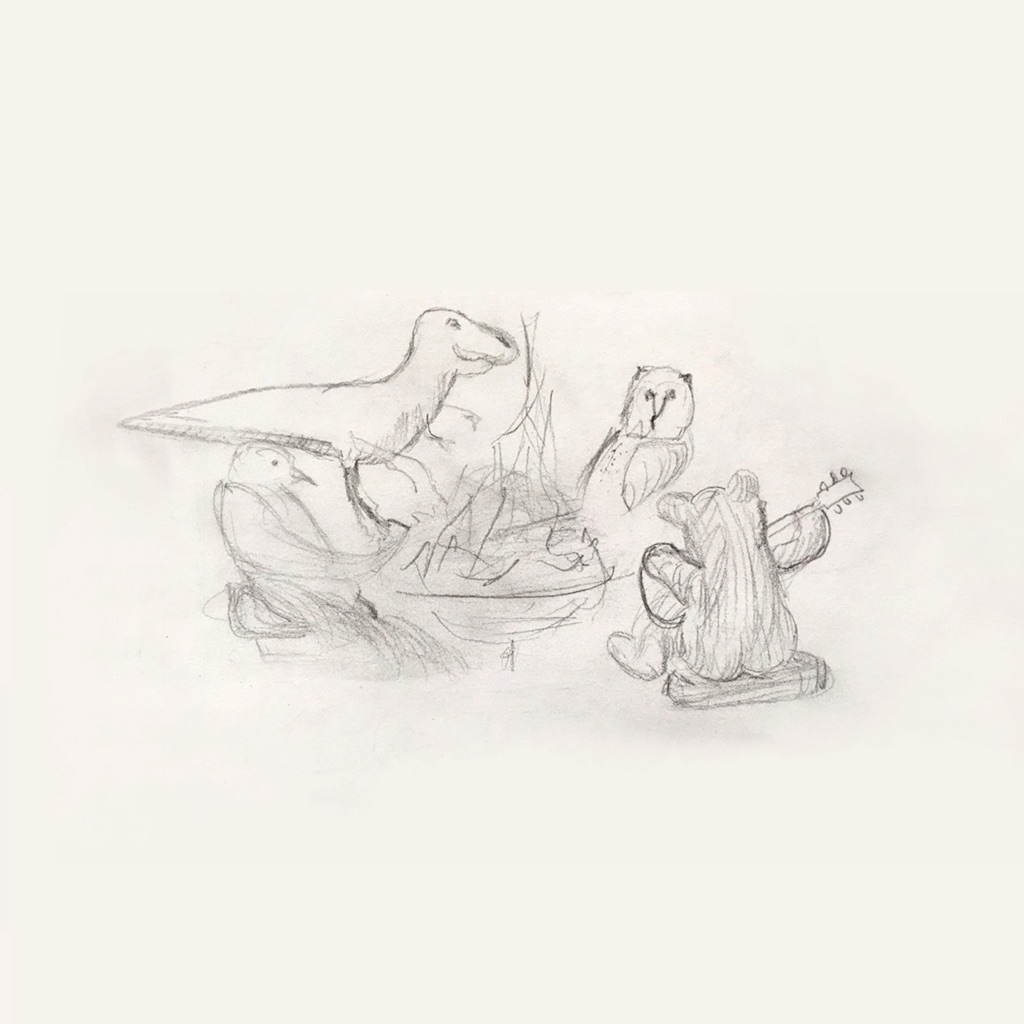

Long before he made his name at jazz’s vanguard, editing together off-the-cuff live sessions like a hip-hop beatmaker, drummer, and producer, Makaya McCraven set out to create a comprehensive record of his collaborative process—a testament to the intuition of improvisation. Its sessions recorded over the course of seven years, between multiple projects and releases, *In These Times* is McCraven’s sixth album as a bandleader, and it showcases the virtuosic instrumentalists he has spent his career building an almost telepathic bond with—bassist Junius Paul and guitarist Jeff Parker among them. It’s also the warmest and most enveloping album he’s produced to date. Frenetic beat-splicing might underpin the polyrhythms of tracks such as “Seventh String” and “This Place That Place,” but the soft melodies played by Parker and harpist Brandee Younger always permeate—a reminder of the clarity of the moment of creation, rather than its post-production manipulation. Indeed, *In These Times* is a reflection of the past decade of McCraven’s instrumental expertise, but it’s also a powerful reminder of the freedom inherent in this time, in the here and now of making music together, when the artist lets go and surrounds us with the ineffable beauty of collective creation.

In These Times is the new album by Chicago-based percussionist, composer, producer, and pillar of our label family, Makaya McCraven. Although this album is “new," the truth it’s something that's been in process for a very long time, since shortly after he released his International Anthem debut In The Moment in 2015. Dedicated followers may note he’s had 6 other releases in the meantime (including 2018’s widely-popular Universal Beings and 2020’s We’re New Again, his rework of Gil Scott-Heron’s final album for XL Recordings); but none of which have been as definitive an expression of his artistic ethos as In These Times. This is the album McCraven’s been trying to make since he started making records. And his patience, ambition, and persistence have yielded an appropriately career-defining body of work. As epic and expansive as it is impressively potent and concise, the 11 song suite was created over 7+ years, as McCraven strived to design a highly personal but broadly communicable fusion of odd-meter original compositions from his working songbook with orchestral, large ensemble arrangements and the edit-heavy “organic beat music” that he’s honed over a growing body of production-craft. With contributions from over a dozen musicians and creative partners from his tight-knit circle of collaborators – including Jeff Parker, Junius Paul, Brandee Younger, Joel Ross, and Marquis Hill – the music was recorded in 5 different studios and 4 live performance spaces while McCraven engaged in extensive post-production work from home. The pure fact that he was able to so eloquently condense and articulate the immense human scale of the work into 41 fleeting minutes of emotive and engaging sound is a monumental achievement. It’s an evolution and a milestone for McCraven, the producer; but moreover it’s the strongest and clearest statement we’ve yet to hear from McCraven, the composer. In These Times is an almost unfathomable new peak for an already-soaring innovator who has been called "one of the best arguments for jazz's vitality" by The New York Times, as well as recently, and perhaps more aptly, a "cultural synthesizer." While challenging and pushing himself into uncharted territories, McCraven quintessentially expresses his unique gifts for collapsing space and transcending borders – blending past, present, and future into elegant, poly-textural arrangements of jazz-rooted, post-genre 21st century folk music.

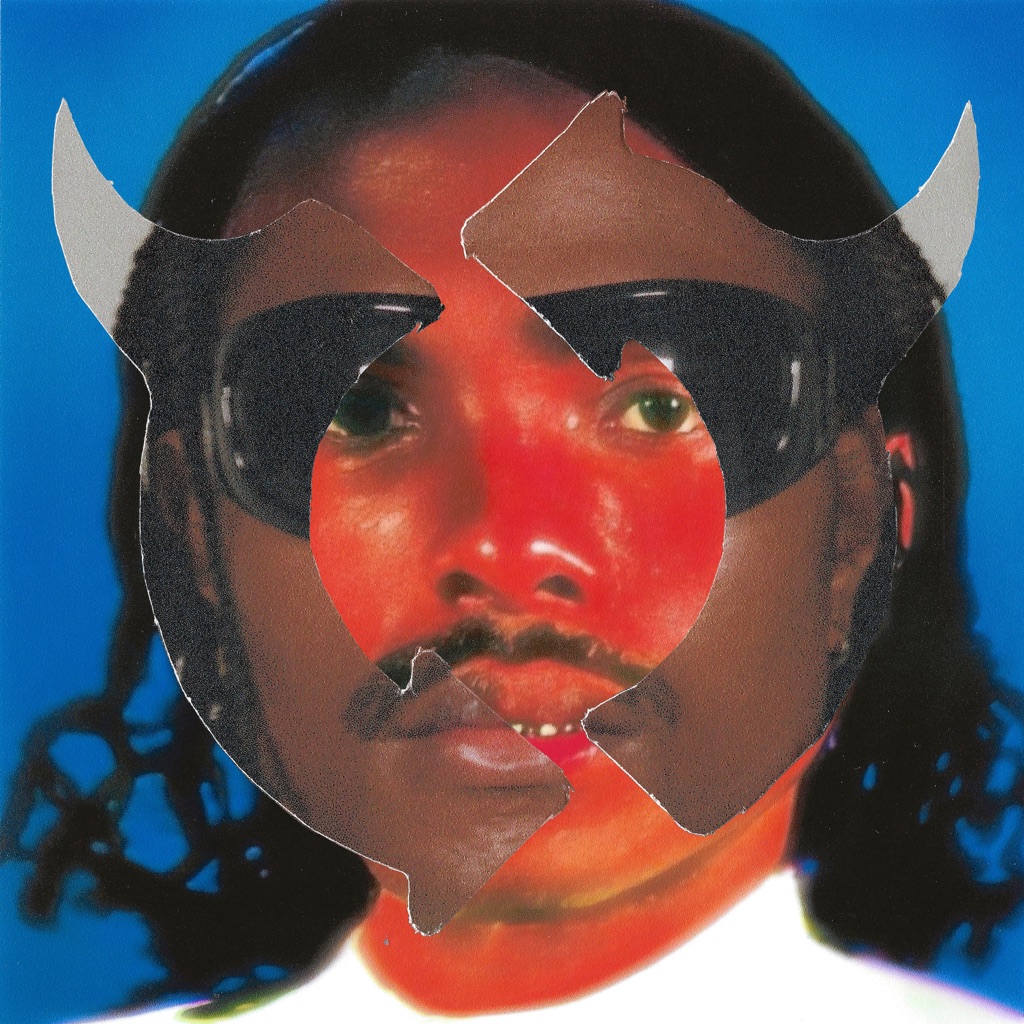

“I want to love unconditionally now.” Read on as Steve Lacy opens up about how he made his sophomore album in this exclusive artist statement. “Someone asked me if I felt pressure to make something that people might like. I felt a disconnect, my eyes squinted as I looked up. As I thought about the question, I realized that we always force a separation between the artist (me) and audience (people). But I am not separate. I am people, I just happen to be an artist. Once I understood this, the album felt very easy and fun to make. *Gemini Rights* is me getting closer to what makes me a part of all things, and that is: feelings. Feelings seem like the only real things sometimes. “I write about my anger, sadness, longing, confusion, happiness, horniness, anger, happiness, confusion, fear, etc., all out of love and all laughable, too. The biggest lesson I learned at the end of this album process was how small we make love. I want to love unconditionally now. I will make love bigger, not smaller. To me, *Gemini Rights* is a step in the right direction. I’m excited for you to have this album as your own as it is no longer mine. Peace.” —Steve Lacy

Tibetan Buddhists often meditate on bardo, a transitional state between life, death, and rebirth. The sense of hovering between the end and a new beginning runs through *The Blue Hour*, a cycle of 40 songs co-written by Rachel Grimes, Angélica Negrón, Shara Nova, Caroline Shaw, and Sarah Kirkland Snider for singer-songwriter Nova and A Far Cry, the Boston-based, self-conducted chamber orchestra. The work takes its lyrics from “On Earth,” a long poem by Carolyn Forché that recounts the thoughts of a dying woman and uses them to cultivate genuine feelings of universal empathy. Its miniature movements include heartfelt ballads, echoes of Bach and Abbess Hildegard (in Caroline Shaw’s mesmerizing *Firmament*), haunting laments, operatic cadenzas, punchy incantations, and much else, the whole proving greater than the sum of its considerable parts.

“You can’t come get this work until it’s dry. I made this album while the streets were closed during the pandemic. Made entirely with the greatest producers of all time—Pharrell and Ye. ONLY I can get the best out of these guys. ENJOY!!” —Pusha T, in an exclusive message provided to Apple Music

S.G. Goodman’s 2020 debut album *Old Time Feeling* announced the Kentucky singer-songwriter as one of roots rock’s finest new voices. Its follow-up is no sophomore slump, further showing the depths of Goodman’s talents as a writer and performer. Recorded in Athens, Georgia, alongside co-producer Drew Vandenberg, *Teeth Marks* is an immersive listen and often surprising, with Goodman eschewing genre confines in favor of a sonic world big enough to suit her larger-than-life songs. Goodman has a knack for finding the universal in small details, as on standout “Dead Soldiers,” which was (its title slang for empty beer bottles) inspired by a friend’s battle with alcoholism. A pair of songs at the album’s center—“If You Were Someone I Loved” and “You Were Someone I Loved”—tell twin tales of the devastating effects of a lack of compassion, with particular regard to the opioid epidemic. Mixed emotions abound, too, like on “Work Until I Die,” which pairs a jaunty beat with a decidedly less playful take on labor.

Part of the appeal of Alex G’s homespun folk pop is how unsettling it is. For every Beatles-y melody (“Mission”) or warm, reassuring chorus (“Early Morning Waiting”) there’s the image of a cocked gun (“Runner”) or a mangled voice lurking in the mix like the monster in a fairy-tale forest (“S.D.O.S”). His characters describe adult perspectives with the terror and wonder of children (“No Bitterness,” “Blessing”), and several tracks make awestruck references to God. With every album, he draws closer to the conventions of American indie rock without touching them. And by the time you realize he isn’t just another guy in his bedroom with an acoustic guitar, it’s too late.

“God” figures in the ninth album from Philadelphia, PA based Alex Giannascoli's LP’s title, its first song, and multiple of its thirteen tracks thereafter, not as a concrete religious entity but as a sign for a generalized sense of faith (in something, anything) that fortifies Giannascoli, or the characters he voices, amid the songs’ often fraught situations. Beyond the ambient inspiration of pop, Giannascoli has been drawn in recent years to artists who balance the public and hermetic, the oblique and the intimate, and who present faith more as a shared social language than religious doctrine. As with his previous records, Giannascoli wrote and demoed these songs by himself, at home; but, for the sake of both new tones and “a routine that was outside of my apartment,” he asked some half-dozen engineers to help him produce the “best” recording quality, whatever that meant. The result is an album more dynamic than ever in its sonic palette. Recorded by Mark Watter, Kyle Pulley, Scoops Dardaris at Headroom Studios in Philadelphia, PA Eric Bogacz at Spice House in Philadelphia, PA Jacob Portrait at SugarHouse in New York, NY & Clubhouse in Rhinebeck, NY Connor Priest, Steve Poponi at Gradwell House Recording in Haddon Heights, NJ Earl Bigelow at Watersong Music in Bowdoinham, ME home in Philadelphia, PA Additional vocals by Jessica Lea Mayfield on “After All” Additional vocals by Molly Germer on “Mission” Guitar performed by Samuel Acchione on “Mission”, “Blessing”, “Early Morning Waiting”, “Forgive” Banjo performed by Samuel Acchione on “Forgive” Bass performed by John Heywood on “Blessing”, “Early Morning Waiting”, “Forgive” Drums performed by Tom Kelly on “No Bitterness”, “Blessing”, “Forgive” Strings arranged and performed by Molly Germer on “Early Morning Waiting”, “Miracles”

Samuel Barber’s *Knoxville: Summer of 1915* is the centerpiece of *Walking in the Dark*, American soprano Julia Bullock’s debut solo album. Her impassioned interpretation plumbs the mix of comforting nostalgia and existential longing Barber writes into the music. Bullock’s couplings are fascinatingly varied. Her version of “Brown Baby,” recorded by Nina Simone and others, has both tenderness and a roiling sense of outrage, while the Connie Converse song “One by One” distills a rare combination of poise and poignancy. The gospel-tinged “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free” highlights Bullock’s acute response to words, and her rapt account of Sandy Denny’s “Who Knows Where the Time Goes” brings the album to a breathtaking conclusion.

Chicago rapper/producer Saba’s first full-length since 2018’s critically acclaimed *CARE FOR ME* looks existentially inward instead of projecting outward. Whereas its predecessor was often perceived through the lens of grief, with his cousin John Walt’s tragic death weighing considerably on the proceedings, his third album explodes such listener myopia with a thoughtful and thought-provoking expression of American Blackness. Though its title might suggest scarcity on a surface level, these 14 songs exude richness in their textures and complexity in their themes. “Stop That” imbues its gauzy trap beat with self-motivating logic, while “Come My Way” gets to reminiscing over a laidback R&B groove. His choice of collaborators demonstrates a carefully curated approach, with 6LACK and Smino bringing a sense of community to the funk-infused “Still” and fellow Chicago native G Herbo helping to unravel multigenerational programming on the gripping “Survivor’s Guilt.” The presence of hip-hop elder statesman Black Thought on the title track only serves to further validate Saba’s experiences, the connection implicitly showing solidarity with sentiments and values of the preceding songs.

Silky-smooth vocals and alt-R&B jams ignite an assured debut LP.

As founding director of the Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice, drummer Terri Lyne Carrington has sought to expand the jazz canon, in part by creating a repository of works by women composers. The book *New Standards: 101 Lead Sheets by Women Composers* is a major step in that direction. With the album *New Standards, Vol. 1*, Carrington begins her effort to record every tune that she and her colleagues have compiled. Co-produced by guitarist Matthew Stevens, the album covers a wide aesthetic range, richly representative of jazz in its time, from tonal harmony to free improvisation, from ballads to driving grooves and much in between. The featured composers are also diverse, from the late and unheralded Sara Cassey (“Wind Flower”) to the iconic Abbey Lincoln (“Throw It Away”); from such veterans as Carla Bley (“Two Hearts \[Lawns\]”), Marilyn Crispell (“Rounds”), and Eliane Elias (“Moments”) to younger blood including Anat Cohen (“Ima”), Brandee Younger (“Respected Destroyer”), Marta Sanchez (“Unchanged”), Gretchen Parlato (“Circling”), Shamie Royston (“Uplifted Heart”), and Patricia Zarate Perez (“Continental Cliff”). The stellar core quintet grows to include many guests: standouts include Somi and Melanie Charles in a shared vocal feature on “Throw It Away” and Julian Lage in an increasingly rare acoustic guitar turn on “Ima.”

When Kendrick Lamar popped up on two tracks from Baby Keem’s *The Melodic Blue* (“range brothers” and “family ties”), it felt like one of hip-hop’s prophets had descended a mountain to deliver scripture. His verses were stellar, to be sure, but it also just felt like way too much time had passed since we’d heard his voice. He’d helmed 2018’s *Black Panther* compilation/soundtrack, but his last proper release was 2017’s *DAMN.* That kind of scarcity in hip-hop can only serve to deify an artist as beloved as Lamar. But if the Compton MC is broadcasting anything across his fifth proper album *Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers*, it’s that he’s only human. The project is split into two parts, each comprising nine songs, all of which serve to illuminate Lamar’s continually evolving worldview. Central to Lamar’s thesis is accountability. The MC has painstakingly itemized his shortcomings, assessing his relationships with money (“United in Grief”), white women (“Worldwide Steppers”), his father (“Father Time”), the limits of his loyalty (“Rich Spirit”), love in the context of heteronormative relationships (“We Cry Together,” “Purple Hearts”), motivation (“Count Me Out”), responsibility (“Crown”), gender (“Auntie Diaries”), and generational trauma (“Mother I Sober”). It’s a dense and heavy listen. But just as sure as Kendrick Lamar is human like the rest of us, he’s also a Pulitzer Prize winner, one of the most thoughtful MCs alive, and someone whose honesty across *Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers* could help us understand why any of us are the way we are.

Listeners expecting the stylish soul-funk of Sault’s 2020 albums *Untitled (Rise)* and *Untitled (Black Is)* might be momentarily thrown by the cosmic choral-and-orchestral suite of *Air*, but thematically, it fits: Like all their music, *Air* is, at heart, a study of Black artistic traditions, in this case early-’70s Alice Coltrane (“Solar”), the soulful ambience of Stevie Wonder’s *Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants* (“Heart”), even a little of the modern-classical side of artists like Anthony Braxton. And as sci-fi as the sound can seem, the core feeling is one of uplifting Earth—a message confirmed as equally by the skyward arc of the strings as by the prayer-like recitation on “Time Is Precious.” Or, as producer Inflo tells Apple Music, not fantasy, but “art in reality”—air.

When Angel Olsen came to craft her sixth album, *Big Time*, the US singer-songwriter had been through, well, a big time. In 2021—just three days after she came out to her parents—her father died; soon after, she lost her mother. Amid it all (and, of course, with the global pandemic as a backdrop), Olsen was falling deep for someone new. *Big Time*, then, is an album that explores the light of new love alongside the dark devastation of loss and grief. Understandably, Olsen—who started work on *Big Time* just three weeks after her mother’s funeral—questioned whether she could make it at all. “It was a heavy time in my life,” she tells Apple Music. “It was the first time I walked into a studio and I had the option of canceling, because of some of the stuff that was going on. But I told my manager, ‘I just wanna try it.’” Working with producer Jonathan Wilson (Father John Misty, Conor Oberst) in a studio in Topanga Canyon, Olsen kept her expectations low and the brief loose. “Essentially, what I told everyone was, ‘I don’t need to turn a pedal steel on its head here, I just want to hear a classic,’” she says. “What would the Neil Young backing band do if they reined it in a little and put the vocals as the main instrument? If you overthink things, you’re really going down into a hole.” The starting point was “All the Good Times,” a song Olsen wrote on tour in 2017/18, and which she envisaged giving to a country singer like Sturgill Simpson. But it had planted a seed. On *Big Time*, she goes all in on country and Americana, inspired by her cherished hometown of Asheville, North Carolina, as well as by artists including Lucinda Williams, Big Star, and Dolly Parton. That sound reaches its peak on the title track, a woozy, waltzing love song that nods to the brighter side of this album’s title: “I’m loving you big time, I’m loving you more,” Olsen sings to her partner Beau Thibodeaux, with whom she wrote the song. In its embrace of simplicity, *Big Time* feels like a deep exhale—and a stark contrast to 2019’s glossy, high-drama *All Mirrors* (though you will find shades of that here, such as on the string- and piano-laden “Through the Fires” or closer “Chasing the Sun”). That undone palette also lays Olsen’s lyrics bare. And if you’ve ever been shattered by the singer-songwriter’s piercing lyricism, you may want to steel yourself. Here, Olsen’s words are more affecting, honest, and raw than ever before, as she navigates not just love and loss but also self-acceptance (“I need to be myself/I won\'t live another lie,” she sings on “Right Now”), our changed world post-pandemic (“Go Home”), and moving forward after the worst has happened. And on the album’s exquisite final track, “Chasing the Sun,” Olsen allows herself to do just that, however tentatively. “Everyone’s wondered where I’ve gone,” she sings. “Having too much fun… Spending the day/Driving away the blues.”

Fresh grief, like fresh love, has a way of sharpening our vision and bringing on painful clarifications. No matter how temporary we know these states to be, the vulnerability and transformation they demand can overpower the strongest among us. Then there are the rare, fertile moments when both occur, when mourning and limerence heighten, complicate and explain each other; the songs that comprise Angel Olsen’s Big Time were forged in such a whiplash. Big Time is an album about the expansive power of new love, but this brightness and optimism is tempered by a profound and layered sense of loss. During Olsen’s process of coming to terms with her queerness and confronting the traumas that had been keeping her from fully accepting herself, she felt it was time to come out to her parents, a hurdle she’d been avoiding for some time. “Finally, at the ripe age of 34, I was free to be me,” she said. Three days later, her father died and shortly after her mother passed away. The shards of this grief—the shortening of her chance to finally be seen more fully by her parents—are scattered throughout the album. Three weeks after her mother’s funeral she was on a plane to Los Angeles to spend a month in Topanga Canyon, recording this incredibly wise and tender new album. Loss has long been a subject of Olsen’s elegiac songs, but few can write elegies with quite the reckless energy as she. If that bursting-at-the-seams, running downhill energy has come to seem intractable to her work, this album proves Olsen is now writing from a more rooted place of clarity. She’s working with an elastic, expansive mastery of her voice—both sonically and artistically. These are songs not just about transformational mourning, but of finding freedom and joy in the privations as they come.

Building on the widespread acclaim of his 2020 Blue Note debut *Omega*, alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins delivers another momentous statement with his sophomore release, *The 7th Hand*. For the most part a showcase of the same incendiary quartet with pianist Micah Thomas, bassist Darryl Johns, and drummer Kweku Sumbry, this outing also includes a collaboration with another of Sumbry’s projects, the Farafina Kan Percussion Ensemble, on “Don’t Break,” and two tracks (including the radiant “Witness”) featuring flutist Elena Pinderhughes, known for her work with Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah. Wilkins envisioned this album as an interconnected suite, with episodes ranging from the tripwire rhythm of “Emanation” and the uptempo fury of “Lighthouse” to the hypnotic melodies of “Shadow” and “Fugitive Ritual, Selah.” The final track, lasting nearly a half hour, sends the quartet into a whole other zone of freely improvised, slowly building heat.

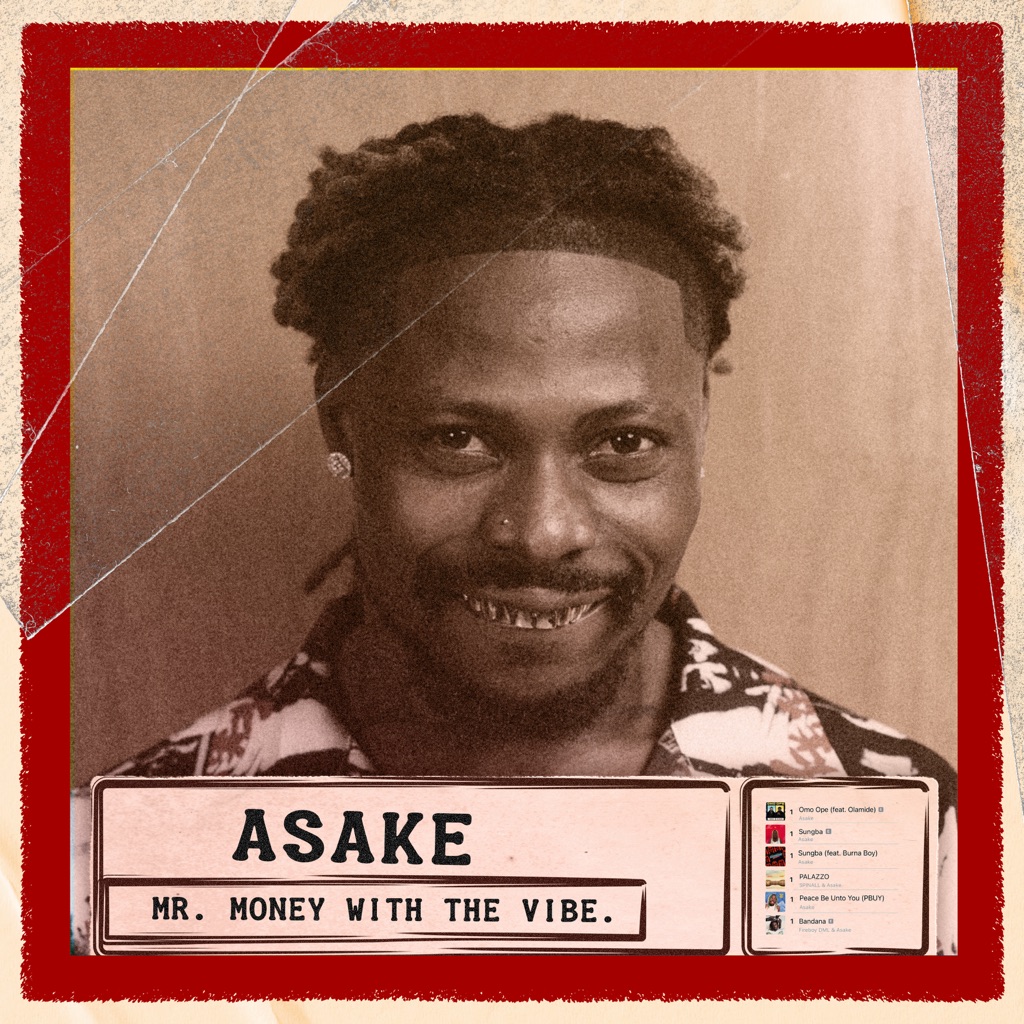

When Ahmed Ololade put out his *Ololade Asake* EP in February 2022, few people knew what to expect from an eclectic artist whose Olamide-assisted “Omo Ope” remix had announced his belated arrival to mainstream audiences. In the seven months between *Ololade Asake* and the release of this, his debut album, the Lagos-based artist scored further hits and seized control of the Afropop zeitgeist with his dizzying mix of street-inspired lyricism, signature chanted vocals, and a fascinating fusion of amapiano, hip-hop, and Fuji instrumentals. *Mr. Money With The Vibe* sees Asake lean into the larger-than-life persona that songs like “Sungba” and “PALAZZO” established. He details his new realities with swagger—contemplating romance, life, and his position in the game over beats delicately crafted by close creative ally Magicsticks. His flair for experimenting within the amapiano framework continues here as he loops the call-and-response pattern of classic Afrobeat over the log drums, sax, and piano on “Organise.” Elsewhere, he brings back a revamped version of blog-era favorite “Joha” and offers a soulful ode to the grind on “Nzaza.” Russ joins for a cautionary tale on “Reason,” and a blistering remix of “Sungba” sees Burna Boy make an appearance here—but the narrative of *Mr. Money With The Vibe* belongs to Asake alone as he continues to blaze a new path for street-pop.

DJ Drama and Jeezy—who became famous as Young Jeezy—were equally important to trap music becoming the dominant sound of hip-hop in the mid-aughts. Though trap is less of a powerhouse in 2022 than it was then, *SNOFALL*, a project released almost 20 years after their first pairing (2004’s *Tha Streetz Iz Watchin’* mixtape), confirms that together they are as capable as they ever were of producing—to borrow a phrase common in Drama parlance—quality street music. *SNOFALL* itself sounds a great deal like their earliest collaborative work. The project features the very producers who helped him define their shared era, names like D. Rich, Cool & Dre, J.U.S.T.I.C.E. League, and Don Cannon. And Jeezy is as pugnacious an MC as he ever was, if slightly wizened. Here he opts less for flexing on detractors than educating the legions of younger G’s he once took so much pride in motivating to chase paper. He uses songs like “Street Cred” to instill a vision of legal hustling, warning them that “street cred” never paid any of his bills, fed his family, took him out of the country for months at a time, or helped him close a million-dollar deal. None of which is to say that the balling has slowed in any way, shape, or fashion. Look no further than “Still Havin,” “Grammy,” or “My Accountant” for an understanding that the Jeezy brand is still and will always be “rich gangsta shit.”

Rather than a set of songs, think of Colombian-born, Berlin-based artist Lucrecia Dalt’s eighth album, *¡Ay!*, as a room cast in sound: smokey, low-lit, seductive but vaguely threatening; a place where fantasy and reality meet in deep, inky shadow. Dalt’s takes on the bolero, son, ranchera, and merengue that form the romantic spine of Latin pop are genuine enough to feel folkloric and off-kilter enough to conjure the art and experimental music she’s known for—a contrast that pulls *¡Ay!* along on its hovering, dreamlike course. Squint and you can imagine hearing “Dicen” in a dusty bar somewhere or swaying to “La Desmesura” or “Bochinche.” But like the great exotica artists of the ’50s, Dalt teeters between the foreign and the comforting so gracefully, you don’t recognize how strange she is until you’re in her pocket. *¡Ay!* is lounge music for the beyond.

Lucrecia Dalt channels sensory echoes of growing up in Colombia on her new album ¡Ay!, where the sound and syncopation of tropical music encounter adventurous impulse, lush instrumentation, and metaphysical sci-fi meditations in an exclamation of liminal delight. In sound and spirit, ¡Ay! is a heliacal exploration of native place and environmental tuning, where Dalt reverses the spell of temporal containment. Through the spiraling tendencies of time and topography, Lucrecia has arrived where she began.

In the context of Nilüfer Yanya’s second album, the word “painless” has a few different meanings. “I was enjoying the process of making the record, and thinking, ‘Why do you have to beat yourself up in order to make something?’” the London singer/guitarist tells Apple Music. “Obviously, you have to work hard, but often the idea of really struggling is something that people inflict on others, just because it\'s the idea they sell to them, like, ‘Oh, you need to go through this.’” Yanya felt that she hadn\'t given herself enough time and space to make her 2019 debut, *Miss Universe*—a record based loosely, and playfully, around the concept of self-help and wellness, and what happens when you get too in your head about things. So, in the thick of the pandemic, she eased into making *PAINLESS*, writing the songs more collaboratively—mostly with producer Will Archer—than she had been used to. “I kind of felt a bit like, ‘Am I cheating?’ Because you\'re sharing the work, it feels lighter,” she says. \"But then because of that, I kind of delved in deeper and it got a bit darker.” (The album title actually comes from the “shameless” lyric “Until you fall, it\'s painless.”) Those depths can be felt both in Yanya\'s vocal dynamics and the sense of urgency that underpins much of the album, particularly on opener “the dealer” and “stabilise,” the first single. “I think the rhythm plays a big part in these songs,” Yanya says. “You feel like there needs to be an escape somewhere.” Here Yanya talks through *PAINLESS*, track by track. **“the dealer”** “It\'s like when someone\'s hiding behind their layers, or not being honest, but then also you\'re not being honest with yourself. My favorite lyric is \'I hope it\'s just the summertime you grew attached to,\' because it\'s like you\'re lying to yourself. You’re not saying, \'Oh, it was this person that made the difference, or it was this person that I miss.\' You\'re just saying, \'I had a great time,\' and you\'re not being honest about why.” **“L/R”** “\[Producer\] Bullion played me this beat, and it had this pitched drum in it. It just made me feel really happy and warm. It had this kind of marching feeling to it, which I really liked. It took us like a year to finish it, but the initial idea came really quickly. I like the almost spoken element to it, because it sounds like you\'re speaking rather than singing, but then the chorus is very much singing—and it took a while to get that right. It\'s kind of about so many things. In my notebook at the time, I\'d written, \'Do less things\'—like, less is more. That was my thinking behind the song: trying to enjoy simple things and not overcomplicate things.” **“shameless”** “It\'s a really intimate song. I felt like it was about someone that\'s trying to run away from stuff in their life, but they kind of don\'t have much hope. The vocals are very celestial—not something I really experimented with in the past. At first, I was going to kind of speak the words, but it needed a lighter touch, like something even more delicate.” **“stabilise”** “That was the first one me and Will did together. All the others kind of grew off that song. It\'s about environments and the way they impact you, and not being able to escape your environment, taking it with you wherever you go. And it kind of becomes your cage or the way you view things. You know when you\'ve been somewhere too long and then it\'s hard to imagine the world another way? Definitely a very lockdown song.” **“chase me”** “I really liked the line \'Through corridors your love will chase me,\' because it was like the safe feeling you can get when you know you are loved, but you don\'t necessarily want it. It\'s almost like an ego song for me. It\'s very confident.” **“midnight sun”** “I was digging into more of an overall feeling and a mood. I feel like it\'s a song about confidence and finding your own voice in order to speak up, whether that\'s about your own feelings or bigger issues: ‘I can\'t keep my mouth shut this time. I can\'t keep my head down. I\'m not going along with this anymore.’” **“trouble”** “That song is so sad—in a beautiful way, if I may say so. It also felt like quite a brave one for me because it\'s very different. When I was writing, I was like, \'Am I doing a straight-up pop song?\' It\'s not. I think it definitely has that take on it. The vocals needed to be more intimate. Like one voice, and it just all keeps spilling out. It\'s quite challenging to sing. ‘Trouble’ is one of those words—I think I heard it in a Cat Stevens song—\'Trouble, set me free\'—and I really loved the way it was being referred to almost like a person. In the lyrics here, it\'s something that\'s quite persistent and it\'s not going away. Something\'s definitely broken that you can\'t fix.” **“try”** “This one is about getting better, and feeling the need to connect on a deeper level, finding new depths and making new connections, but becoming confused, tired, and dejected with the effort it takes.” **“company”** “It\'s about giving up and you\'re not in a happy place. Originally it started out as, like, you\'re in a relationship that you are just really not sure about and you\'re trying to give signs across that you\'re trying to get rid of someone. But I think the song now is definitely about your inner demons, and they\'re not really going away.” **“belong with you”** “I did this with Jazzi Bobbi, who\'s in my band. She does more electronic stuff, so that definitely comes into play. I feel like builds are always my favorite things in songs, and at the beginning we actually tried to overcomplicate the song and there was like a whole other section and it changed tempo and it just wasn\'t working. And I was like, \'We just need to keep building and that\'s it.\' What it\'s about is like you\'re tied into something, but you know you\'re too good for it or you want to leave. I feel like these are all the songs, in a way. It’s like, escape—but you can\'t escape.” **“the mystic”** “It\'s about watching other people get on with their lives and feeling like you\'re being left behind. I spend a lot of time doing music, so that\'s where I put all my energy, and I was like, \'Oh, I thought we were all still doing that.\' Other people have got other plans and you\'re like, \'Oh, you\'re a grown-up. You\'re going to move in with your boyfriend,\' or, \'Oh, you can drive now.\' The verse is really sad, because it\'s about watching that happen, and feeling very insecure and unconfident.” **“anotherlife”** “For me, this has a completely different energy. It\'s kind of like you\'re admitting you\'re lost now, but in a parallel universe or in the future, you won\'t always be lost. It\'s not always bad to be in that kind of lost, super-emotional, flung-out state. I find sometimes when something bad happens and you get really upset, it\'s kind of— I don\'t want to say cleansing, but you see things with this new kind of brilliance and clarity. And that\'s kind of a beautiful moment.”

Nilüfer Yanya runs head first into the depths of emotional vulnerability on her anticipated sophomore record PAINLESS. Recorded between a basement studio in Stoke Newington and Riverfish Music in Penzance, the record is a more sonically direct effort, narrowing her previously broad palette to a handful of robust ideas. Yanya's debut album Miss Universe (2019) earned a Best New Music tag from Pitchfork and saw support tours with Sharon Van Etten, Mitski and The XX.

A couple of years before she became known as one half of Wet Leg, Rhian Teasdale left her home on the Isle of Wight, where a long-term relationship had been faltering, to live with friends in London. Every Tuesday, their evening would be interrupted by the sound of people screaming in the property below. “We were so worried the first time we heard it,” Teasdale tells Apple Music. Eventually, their investigations revealed that scream therapy sessions were being held downstairs. “There’s this big scream in the song ‘Ur Mum,’” says Teasdale. “I thought it’d be funny to put this frustration and the failure of this relationship into my own personal scream therapy session.” That mix of humor and emotional candor is typical of *Wet Leg*. Crafting tightly sprung post-punk and melodic psych-pop and indie rock, Teasdale and bandmate Hester Chambers explore the existential anxieties thrown up by breakups, partying, dating apps, and doomscrolling—while also celebrating the fun to be had in supermarkets. “It’s my own experience as a twentysomething girl from the Isle of Wight moving to London,” says Teasdale. The strains of disenchantment and frustration are leavened by droll, acerbic wit (“You’re like a piece of shit, you either sink or float/So you take her for a ride on your daddy’s boat,” she chides an ex on “Piece of shit”), and humor has helped counter the dizzying speed of Wet Leg’s ascent. On the strength of debut single “Chaise Longue,” Teasdale and Chambers were instantly cast by many—including Elton John, Iggy Pop, and Florence Welch—as one of Britain’s most exciting new bands. But the pair have remained committed to why they formed Wet Leg in the first place. “It’s such a shame when you see bands but they’re habitually in their band—they’re not enjoying it,” says Teasdale. “I don’t want us to ever lose sight of having fun. Having silly songs obviously helps.” Here, she takes us through each of the songs—silly or otherwise—on *Wet Leg*. **“Being in Love”** “People always say, ‘Oh, romantic love is everything. It’s what every person should have in this life.’ But actually, it’s not really conducive to getting on with what you want to do in life. I read somewhere that the kind of chemical storm that is produced in your brain, if you look at a scan, it’s similar to someone with OCD. I just wanted to kind of make that comparison.” **“Chaise Longue”** “It came out of a silly impromptu late-night jam. I was staying over at Hester’s house when we wrote it, and when I stay over, she always makes up the chaise longue for me. It was a song that never really was supposed to see the light of day. So it’s really funny to me that so many people are into it and have connected with it. It’s cool. I was as an assistant stylist \[on Ed Sheeran’s ‘Bad Habits’ video\]. Online, a newspaper \[*The New York Times*\] was doing the top 10 videos out this week, and it was funny to see ‘Chaise Longue’ next to this video I’d been working on. Being on set, you have an idea of the budget that goes into getting all these people together to make this big pop-star video. And then you scroll down and it’s our little video that we spent about £50 on. Hester had a camera and she set up all the shots. Then I edited it using a free trial version of Final Cut.” **“Angelica”** “The song is set at a party that you no longer want to be at. Other people are feeling the same, but you are all just fervently, aggressively trying to force yourself to have a good time. And actually, it’s not always possible to have good times all the time. Angelica is the name of my oldest friend, so we’ve been to a lot of rubbish parties together. We’ve also been to a lot of good parties together, but I thought it would be fun to put her name in the song and have her running around as the main character.” **“I Don’t Wanna Go Out”** “It’s kind of similar to ‘Angelica’—it’s that disenchantment of getting fucked up at parties, and you’re gradually edging into your late twenties, early thirties, and you’re still working your shitty waitressing job. I was trying to convince myself that I was working these shitty jobs so that I could do music on the side. But actually, you’re kind of kidding yourself and you’re seeing all of your friends starting to get real jobs and they’re able to buy themselves nice shampoo. You’re trying to distract yourself from not achieving the things that you want to achieve in life by going to these parties. But you can’t keep kidding yourself, and I think it’s that realization that I’ve tried to inject into the lyrics of this song.” **“Wet Dream”** “The chorus is ‘Beam me up.’ There’s this Instagram account called beam\_me\_up\_softboi. It’s posts of screenshots of people’s texts and DMs and dating-app goings-on with this term ‘softboi,’ which to put it quite simply is someone in the dating scene who’s presenting themselves as super, super in touch with their feelings and really into art and culture. And they use that as currency to try and pick up girls. It’s not just men that are softbois; women can totally be softbois, too. The character in the song is that, basically. It’s got a little bit of my own personal breakup injected into it. This particular person would message me since we’d broken up being like, ‘Oh, I had a dream about you. I dreamt that we were married,’ even though it was definitely over. So I guess that’s why I decided to set it within a dream: It was kind of making fun of this particular message that would keep coming through to me.” **“Convincing”** “I was really pleased when we came to recording this one, because for the bulk of the album, it is mainly me taking lead vocals, which is fine, but Hester has just the most beautiful voice. I hope she won’t mind me saying, but she kind of struggles to see that herself. So it felt like a big win when she was like, ‘OK, I’m going to do it. I’m going to sing. I’m going to do this song.’ It’s such a cool song and she sounds so great on it.” **“Loving You”** “I met this guy when I was 20, so I was pretty young. We were together for six or seven years or something, and he was a bit older, and I just fell so hard. I fell so, so hard in love with him. And then it got pretty toxic towards the end, and I guess I was a bit angry at how things had gone. So it’s just a pretty angry song, without dobbing him in too much. I feel better now, though. Don’t worry. It’s all good.” **“Ur Mum”** “It’s about giving up on a relationship that isn’t serving you anymore, either of you, and being able to put that down and walk away from it. I was living with this guy on the Isle of Wight, living the small-town life. I was trying to move to London or Bristol or Brighton and then I’d move back to be with this person. Eventually, we managed to put the relationship down and I moved in with some friends in London. Every Tuesday, it’d get to 7 pm and you’d hear that massive group scream. We learned that downstairs was home to the Psychedelic Society and eventually realized that it was scream therapy. I thought it’d be funny to put this frustration and the failure of this relationship into my own personal scream therapy session.” **“Oh No”** “The amount of time and energy that I lose by doomscrolling is not OK. It’s not big and it’s not clever. This song is acknowledging that and also acknowledging this other world that you live in when you’re lost in your phone. When we first wrote this, it was just to fill enough time to play a festival that we’d been booked for when we didn’t have a full half-hour set. It used to be even more repetitive, and the lyrics used to be all the same the whole way through. When it came to recording it, we’re like, ‘We should probably write a few more lyrics,’ because when you’re playing stuff live, I think you can definitely get away with not having actual lyrics.” **“Piece of shit”** “When I’m writing the lyrics for all the songs with Wet Leg, I am quite careful to lean towards using quite straightforward, unfussy language and I avoid, at all costs, using similes. But this song is the one song on the album that uses simile—‘like a piece of shit.’ Pretty poetic. I think writing this song kind of helped me move on from that \[breakup\]. It sounds like I’m pretty wound up. But actually, it’s OK now, I feel a lot better.” **“Supermarket”** “It was written just as we were coming out of lockdown and there was that time where the highlight of your week would be going to the supermarket to do the weekly shop, because that was literally all you could do. I remember queuing for Aldi and feeling like I was queuing for a nightclub.” **“Too Late Now”** “It’s about arriving in adulthood and things maybe not being how you thought they would be. Getting to a certain age, when it’s time to get a real job, and you’re a bit lost, trying to navigate through this world of dating apps and social media. So much is out of our control in this life, and ‘Too late now, lost track somehow,’ it’s just being like, ‘Everything’s turned to shit right now, but that’s OK because it’s unavoidable.’ It sounds very depressing, but you know sometimes how you can just take comfort in the fact that no matter what you do, you’re going to die anyway, so don’t worry about it too much, because you can’t control everything? I guess there’s a little bit of that in ‘Too Late Now.’”

Brooklyn-based, Asian American musician and composer OHYUNG’s music is continuously shifting, investigating, and deconstructing the possibilities of form. Written and recorded mostly over just a 72-hour period, OHYUNG’s first album on NNA Tapes, the immersive and mesmerizing, imagine naked! focuses on expansion and atmospheric depth. It is a collection of loving ambient expressions of persistence, repetition, and variation. Each song is titled after a line from t. tran le’s poem, “Vegetalscape,” which acts as an artistic companion to the album. The poem works to spotlight little things that le imparts beauty upon despite the challenges of living with mental illness, such as a bedroom garden, or a sibling’s voice singing in the shower. OHYUNG’s engulfing, gentle landscapes take on the context of something more literary than their wordless atmosphere—each line feels as though it informs the timbre of its connected piece—and they reflect le’s poem as these snapshots of small items and instances, and brief melodies are appreciated and made beautiful beyond their size. The music of imagine naked! is full and complex, each track using its time to articulate an entire spectrum of lived emotion with remarkable elegance and simplicity. Some of the songs revel in quiet magnificence: lead single “symphonies sweeping!” is the extension of a breathless instant, the moment between the orchestra’s end and the recognition of applause, as notes linger and hang in the air; “my hands hold flora!” begins as a low tone over a bleak, crackling background, but that gives way to something more bright and shimmering; the joyful and effervescent “i’m remembering!” is a kind memory, like recalling the details of a loved one’s face—an exuberance brought by clarity. Other pieces seem to notice discomfort, like on “tucked in my stomach!,” which plays like a harsh self-reflection, emphasizing sharp, piercing tones. The melancholic piano notes on “yes my weeping frame!” fall over one another like a waterfall or a stream of tears. The title track, “imagine naked!,” is unencumbered by any additions, with somber drones that capture the vulnerability of being bare. The final three songs close the album with a calming, sustained exhale. “philodendrons trail!” feels fresh and clean, and “oxalis unfold!” opens incrementally towards a warm light. The serene grand finale of “releases like gloves!’ (not included on the CD version) is entirely a world of its own—orange and purple sky, soundtracked by far-off refrains and the pressure of worry hissing away like steam. On this album, OHYUNG shifts again, deliberately moving away from the experimental, electronic, hip-hop, and noise influenced work of their previous records, Untitled (Chinese Man with Flame), PROTECTOR, and GODLESS, and expanding on the space found in their work as a composer on films like Bambirak, which won the 2021 Short Film Jury Award for International Fiction at Sundance Film Festival, and the Gotham Award-nominated Test Pattern. By focusing on longer, more drawn-out, and textural compositions as an exercise in patience and as a means to cope with the difficult, oscillating new experience of time brought on by the pandemic, OHYUNG has found yet another new way to consider reality and feeling. imagine naked! is humanist music that seeks to explore the mundane strangeness that defines our everyday and that breathes air, or purpose, or just some kind of color into ourselves and the people and the environment around us.

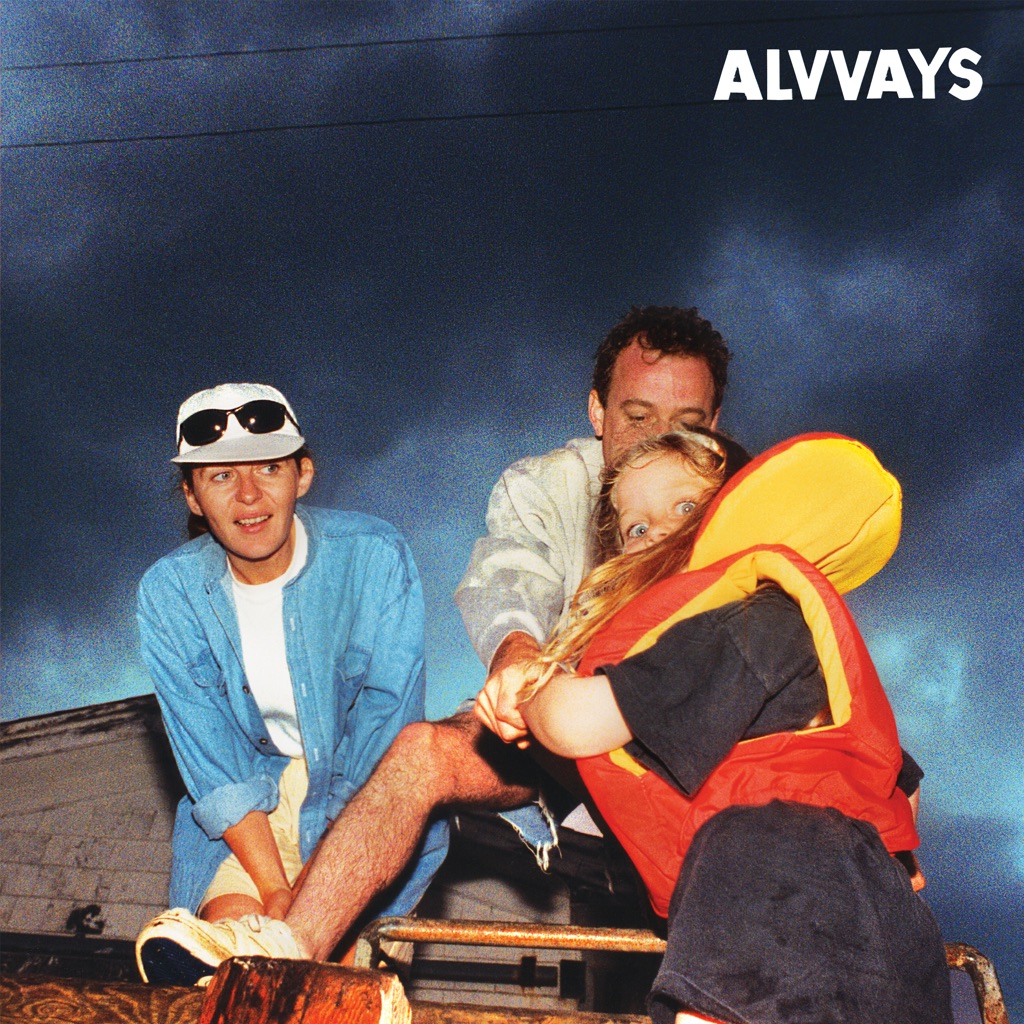

Alvvays never intended to take five years to finish their third album, the nervy joyride that is the compulsively lovable Blue Rev. In fact, the band began writing and cutting its first bits soon after releasing 2017’s Antisocialites, that stunning sophomore record that confirmed the Toronto quintet’s status atop a new generation of winning and whip-smart indie rock. Global lockdowns notwithstanding, circumstances both ordinary and entirely unpredictable stunted those sessions. Alvvays toured more than expected, a surefire interruption for a band that doesn’t write on the road. A watchful thief then broke into singer Molly Rankin’s apartment and swiped a recorder full of demos, one day before a basement flood nearly ruined all the band’s gear. They subsequently lost a rhythm section and, due to border closures, couldn’t rehearse for months with their masterful new one, drummer Sheridan Riley and bassist Abbey Blackwell. At least the five-year wait was worthwhile: Blue Rev doesn’t simply reassert what’s always been great about Alvvays but instead reimagines it. They have, in part and sum, never been better. There are 14 songs on Blue Rev, making it not only the longest Alvvays album but also the most harmonically rich and lyrically provocative. There are newly aggressive moments here—the gleeful and snarling guitar solo at the heart of opener “Pharmacist,” or the explosive cacophony near the middle of “Many Mirrors.” And there are some purely beautiful spans, too—the church- organ fantasia of “Fourth Figure,” or the blue-skies bridge of “Belinda Says.” But the power and magic of Blue Rev stems from Alvvays’ ability to bridge ostensible binaries, to fuse elements that seem antithetical in single songs—cynicism and empathy, anger and play, clatter and melody, the soft and the steely. The luminous poser kiss-off of “Velveteen,” the lovelorn confusion of “Tile by Tile,” the panicked but somehow reassuring rush of “After the Earthquake”. The songs of Blue Rev thrive on immediacy and intricacy, so good on first listen that the subsequent spins where you hear all the details are an inevitability. This perfectly dovetailed sound stems from an unorthodox—and, for Alvvays, wholly surprising—recording process, unlike anything they’ve ever done. Alvvays are fans of fastidious demos, making maps of new tunes so complete they might as well have topographical contour lines. But in October 2021, when they arrived at a Los Angeles studio with fellow Canadian Shawn Everett, he urged them to forget the careful planning they’d done and just play the stuff, straight to tape. On the second day, they ripped through Blue Rev front-to-back twice, pausing only 15 seconds between songs and only 30 minutes between full album takes. And then, as Everett has done on recent albums by The War on Drugs and Kacey Musgraves, he spent an obsessive amount of time alongside Alvvays filling in the cracks, roughing up the surfaces, and mixing the results. This hybridized approach allowed the band to harness each song’s absolute core, then grace it with texture and depth. Notice the way, for instance, that “Tom Verlaine” bursts into a jittery jangle; then marvel at the drums and drum machines ricocheting off one another, the harmonies that crisscross, and the stacks of guitar that rise between riff and hiss, subtle but essential layers that reveal themselves in time. Every element of Alvvays leveled up in the long interim between albums: Riley is a classic dynamo of a drummer, with the power of a rock deity and the finesse of a jazz pedigree. Their roommate, in-demand bassist Blackwell, finds the center of a song and entrenches it. Keyboardist Kerri MacLellan joined Rankin and guitarist Alec O’Hanley to write more this time, reinforcing the band’s collective quest to break patterns heard on their first two albums. The results are beyond question: Blue Rev has more twists and surprises than Alvvays’ cumulative past, and the band seems to revel in these taken chances. This record is fun and often funny, from the hilarious reply-guy bash of “Very Online Guy” to the parodic grind of “Pomeranian Spinster.” Alvvays’ self-titled debut, released when much of the band was still in its early 20s, offered speculation about a distant future—marriage, professionalism, interplanetary citizenship. Antisocialites wrestled with the woes of the now, especially the anxieties of inching toward adulthood. Named for the sugary alcoholic beverage Rankin and MacLellan used to drink as teens on rural Cape Breton, Blue Rev looks both back at that country past and forward at an uncertain world, reckoning with what we lose whenever we make a choice about what we want to become. The spinster with her Pomeranians or Belinda with her babies? The kid fleeing Bristol by train or the loyalist stunned to see old friends return? “How do I gauge whether this is stasis or change?” Rankin sings during the first verse of the plangent and infectious “Easy on Your Own?” In that moment, she pulls the ties tight between past, present, and future to ask hard questions about who we’re going to become, and how. Sure, it arrives a few years later than expected, but the answer for Alvvays is actually simple: They’ve changed gradually, growing on Blue Rev into one of their generation’s most complete and riveting rock bands.

Early adopters of Memphis spitter and recent CMG signee GloRilla will recognize the title of the MC’s debut EP, *Anyways, Life’s Great...*, as a quip from her breakout hit “F.N.F (Let’s Go).” But if the bars on the rest of the EP are any indication of what the woman born Gloria Hallelujah Woods has in store for fans, she’ll have project titles until her dying days, and plenty of demand for them. Woods, who was still riding high from the success of “F.N.F (Let’s Go)” as well as the Cardi B collaboration “Tomorrow 2” upon the release of *Anyways, Life’s Great...*, has a gruff rhyme style that strikes a perfect balance between bravado and relatability, something she attributes to taking the time to develop who she was on the mic. “My normal voice, it ain\'t all soft and stuff, like a normal female voice,” she tells Apple Music. “So when I first started rapping, I used to try to sound girly. I really just had to find myself, find my voice and how I rap. And I really got a Memphis sound, too.” For the well-informed, that much is apparent from her accent and the way she punctuates some of her statements with “mane,” as she does frequently across the EP. What she also does is tell fair-weather fans about themselves (“No More Love”), take disappointing sexual partners to task (“Nut Quick”), celebrate how far she’s come as an artist (“Blessed”), and take off her cool to get vulnerable (“Out Loud Thinking”). Runaway success like the kind GloRilla first encountered with “F.N.F (Let’s Go)” has been the downfall of plenty a promising MC, but to let her tell it, having a hit right out of the gate only gave her a blueprint for success. “I learned to rap how I feel and to keep putting out that real authentic shit,” she says of “F.N.F”\'s reception. “And to continue to smoke weed, because I was high as a motherfucker when I wrote that song.” Below, GloRilla sheds even more light on a few key tracks from *Anyways, Life’s Great...*. **“PHATNALL”** “Out here in Memphis—a lot of people do this all over the world—when people die, they get their names tatted on their face. So I’m like, my ex is really dead to me. They so dead to me, I might get their name tatted on my face.” **“Tomorrow 2” (feat. Cardi B)** “My team was tryna surprise me \[with a Cardi guest verse\], but I ended up finding out because I was texting her to get on another song and she ended up telling me! She sent me the verse and I was like, ‘Oh my god! She killed this.’\" **“Blessed”** “I made ‘Blessed’ after I had linked with \[CMG founder Yo\] Gotti. We was in New York—this was before we had went public about the signing—and I was just feeling super blessed. Like that was a time when everything was just happening for me. My life was changing. And that’s just how I came up with that. Just in the studio, high, smoking weed.” **“Nut Quick”** “There\'s a lot of dudes out here that nut quick. They be cool and all, they just got sexual problems. I know a lot of females feeling me. Like, you cool, but you just nut quick.” **“F.N.F (Let’s Go)”** “A lot of times I record something and I’ll be like, ‘Ooh, this the one.’ I say that about a lot of my songs. ‘F.N.F,’ it just really happened to be *the one*. So when that song blew up—when I first posted the trailer—I started seeing a change then.” **“Out Loud Thinking”** “I was going through a really rough time in my life when I recorded this song. I remember I was in line at the drive-through at Taco Bell mixed with KFC. I was just playing a beat and I shed a couple tears and thought of writing that song.”

The musical vortexes of Caterina Barbieri rewire time and space. Listening to the Italian composer and modular synth virtuoso has felt like traveling at light-speed and slow-motion all at once since 2017’s breakthrough double-album Patterns Of Consciousness. 2019’s acclaimed Ecstatic Computation pushed even further with the lead single “Fantas”, where a haunting melody hurtling towards its supernova climax felt like witnessing the life and death of a burning star. Far beyond any new age trope or modern synth trend, her music stands alone in its ecstatic intensity and cataclysmic emotional impact. Marking the debut album on her new label light-years, Barbieri now delivers her most profound work yet — a journey through inner-space as vast as a universe and as intimate as a heartbeat. The Spirit Exit opens and we fall in. Spirit Exit is Caterina Barbieri’s time machine, primarily composed with a modular synth rig she thinks of more like a mechanical fortune teller. Whereas previous releases were constructed on lengthy tours, capturing only snapshots of continually evolving works, Spirit Exit represents the producer’s first album fully written and recorded in her home studio amidst Milan’s two-month pandemic lockdown in 2020. It was during this extended isolation she found inspiration from female philosophers, mystics and poets spread across time, but united in their strength at cultivating vast internal worlds. St. Teresa D’Avila’s foundational 16th century mystical text The Interior Castle, philosopher Rosi Braidotti’s posthuman theories and the metaphysical poetry of Emily Dickinson act as thematic anchors throughout Spirit Exit, imbuing a life and death gravity into the composer’s most perception-altering music to date. More than any release before it, Spirit Exit crystallizes Barbieri’s densely layered, blindingly bright synth arrangements while introducing stunning new elements that feel as if they’ve always belonged. Strings and guitar flawlessly thread into the composer’s web of modular patches, while her revelatory singing voice often cuts right through them. Melodies remain Barbieri’s great passion and obsession — she thinks of them as knots she’s trying to untangle, existential metaphors formed through tensely spiraling arpeggios — and on Spirit Exit they grow as large as planets before cracking into atoms. Parts of one song can haunt another. The synth progression unraveling through “Knot Of Spirit” is reborn on “Broken Melody”, an explosive peak with vocals that flash like a lightning storm. The sweeping “At Your Gamut” perfects the producer’s dramatic, slow-burning openers, but in her first ever use of sampling, it later gets crushed, accelerated and unrecognizably transformed into the ghostly hook surging through “Terminal Clock” — an otherworldly sound rushing across what feels like the artist’s first track for a dancefloor. Caterina Barbieri’s music has always transported listeners, its perpetual movement achieved through complexities that needn’t be solved, but simply felt. Spirit Exit articulates that endless ascension — destination unknown, resolution always just out of reach — with a newfound humanity. It’s the result of a one-of-a-kind artist deeply reflecting on what music means to them, only to return with an even greater understanding of what it can be. As the album closes on “The Landscape Listens” — a song that approaches death with all the gentle grace of Brian Eno’s “An Ending (Ascent)” — it brings to mind the full line of Emily Dickinson’s poem “There’s a certain slant of light”. “When it comes — the landscape listens / Shadows — hold their breath.” Spirit Exit is a special kind of seance, an album so otherworldly and inexplicably moving it leaves even its ghosts in a stunned silence.