Northern Transmissions' Best Albums of 2024

We've collected the best albums of 2024 on one list so you don't have to miss, featuring Christopher Owens, Charli XCX, DIIV and many more!

Published: December 17, 2024 16:06

Source

The musician born Josh Tillman chose the title for his sixth album in a decidedly Father John Misty kind of way: He found the Sanskrit word in a novel by Bruce Wagner, who shares with the musician a certain impish LA mysticism. Mahāśmaśāna translates to “great cremation ground,” so it’s no surprise to find the singer-songwriter in “what’s it all mean?” mode, trawling tragicomic corners of the American Southwest in search of answers about life, death, and humanity. After trying his hand at big-band jazz on 2022’s *Chloë and the Next 20th Century*, Tillman returns to the big, sweeping ’70s-style pop rock that’s earned him a place among his generation’s most intriguing songwriters. He channels Leonard Cohen’s *Death of a Ladies’ Man* on the sprawling title track, whose swooning orchestration and ambitious lyrics take stock of, well, everything. “She Cleans Up” tells a rollicking tale involving female aliens, high-dollar kimonos, and rabbits with guns, and on dystopian power ballad “Screamland,” he offers an all-American refrain: “Stay young/Get numb/Keep dreaming.”

DIIV has always been a musical shape-shifter—subtly mutating into new forms that are deeply felt by those who pay close attention to its sonic textures. The band’s debut album, 2012’s *Oshin*, was double-dipped in the chiming guitars of classic indie pop and post-punk’s intense persistence; *Is the Is Are*, from 2016, stretched lush dream-pop weavings across its wide canvas, while 2019’s *Deceiver* dove headlong into shoegaze’s bottomless bliss. For its first album in five years, the quartet led by Zachary Cole Smith takes its catalog into several thrilling new turns: At various points, *Frog in Boiling Water* conjures the sweeping drama of goth à la *Seventeen Seconds*-era The Cure, slowcore’s crushing and hypnotic beauty, and the metallic textures of vintage grunge. DIIV has never sounded so devastating, so ominous, and so utterly pristine as it does on *Frog in Boiling Water*—a triumph in fidelity that’s owed as much to veteran indie-rock producer Chris Coady (Beach House, Future Islands) as it is to the band’s locked-in interplay. Smith and Andrew Bailey’s guitars drip like melted candles over the vast expanse of “Soul-net,” while “Brown Paper Bag” stomps and splashes with every cymbal crash, courtesy of drummer Ben Newman. This might be the heaviest music DIIV has ever put to tape, and its doomy sound perfectly matches the album’s foreboding themes. Borrowing its title from a central metaphor in Daniel Quinn’s 1996 novel *The Story of B*, *Frog in Boiling Water* takes aim at what the band refers to as “the slow, sick, and overwhelmingly banal collapse of society under end-stage capitalism,” and a close read of Smith’s lyrics indeed reveals a sense of wide-scale distrust, as well as general societal malaise. But even at its most despairing, DIIV never forgets that retaining a sense of humanity is key to surviving what lies ahead: “The worst of times/Leave them behind,” Smith implores over the soaring riffs of “Reflected.” “But keep that lump in your throat.”

UK rock polymaths black midi accomplished so much in such a short time—and at such a young age—that the group’s sudden announcement of their indefinite hiatus in 2024 couldn’t help but raise questions. Geordie Greep’s solo debut *The New Sound* doesn’t so much provide answers as it does multiple pathways forward. black midi acolytes will recognize a few stylistic touches here and there that have carried over to Greep’s boundless musical map: jazz fusion breakdowns; multi-suite songwriting indebted to prog’s knotty weirdness; and Greep’s increasing penchant for all-caps storytelling, which previously reared its head on black midi’s swan-song-for-now *Hellfire* in 2022. Otherwise, *The New Sound* lives up to its title by reintroducing Greep as a musically omnivorous showman, as he leaps into the spotlight with outsized bravado and a wild-eyed sense of sonic fearlessness. Featuring an expansive cast of supporting players and session musicians—including black midi drummer Morgan Simpson—*The New Sound* is far-flung in locale and genre: Cobbled together over the course of a year from studio time in London and São Paulo, its 11 tracks are positively boundless in stylistic flourish. The easy bossa nova swing of “Terra” and the jazz-hands ascent of first single “Holy, Holy” recall Steely Dan bandleader Donald Fagen’s classic 1982 solo LP *The Nightfly*, while the two-wheeled angst of “Motorbike” isn’t far off from the discordant post-punk abstractions of the London-based Speedy Wunderground scene that black midi was often associated with. If that all sounds hard to pin down, just wait until you dig into the lyric sheet for this one, as Greep’s logorrheic maelstrom tackles the dark, impotent lasciviousness of male sexuality with explicit gusto. It’s provocative without being needlessly shocking, an impressive tightrope walk that marks *The New Sound*’s loopy idiosyncrasies as a whole.

The LA-by-way-of-Miami duo of Mica Tenenbaum and Matthew Lewin pick up where they left things on their debut, 2021’s *Mercurial World*, and make everything just a bit bigger. Opener “She Looked Like Me!” begins innocently enough, with hushed vocals from Tenenbaum backed by twinkling keys and a buzzing bass synth. Before long, though, massive drum hits give the song an unrelenting pulse, blending the energy of a hyperpop anthem with the rise-and-fall restraint of a classic-rock song. “Image” is a disco-inspired cut that dances around synths that speed up and slow down according to their own whimsy, as Tenenbaum’s voice floats effortlessly above the fray. “What\'s the best you’ve got?/I forgot all my common sense/I need all the common sense/Time to start the clock from the top,” she sings, letting the feel-good vibes of the club-ready instrumental imbue her abstract lyrics with visceral meaning. Even when the duo concoct songs that fear the future or suggest wariness at where the world is headed, the jams suggest that the AI apocalypse will still feature plenty of dancing.

Chat Pile’s sludgy mix of nu metal and ’90s underground rock isn’t anything new, but it’s hard to imagine it existing so comfortably at any other time. Part of it’s their willingness to traverse what in another era would’ve been uncrossable cultural lines: Pledging your allegiance to the funny, post-punk surrealism of a band like Pere Ubu (“Camcorder”) at the same time as the single-entendre misery of Korn (“Funny Man”), for example. If metal is, on some level, guitar-country, Chat Pile is firmly set in its rhythm section, which is as rumbling and inescapable as the power lines and strip-mined hills of the Middle America outside their window, leaving the guitars primarily to peel paint. Where guys this misanthropic might’ve been considered social liabilities in their past (or at least dangers to their parents and church youth group), now they sound content to stay in their rooms and pig out on memes about the world they’ve always known was in ruin. “Tape” is the peak here not because it’s the hardest but because it’s the funkiest, whatever funk means to bands like this. Forget alienation—they’re laughing.

When artists experience the kind of career-defining breakthrough that Waxahatchee’s Katie Crutchfield enjoyed with 2020’s *Saint Cloud*, they’re typically faced with a difficult choice: lean further into the sound that landed you there, or risk disappointing your newfound audience by setting off into new territory. On *Tigers Blood*, the Kansas City-based singer-songwriter chooses the former, with a set of country-indebted indie rock that reaches the same, often dizzying heights as its predecessor. But that doesn’t mean its songs came from the same emotional source. “When I made *Saint Cloud*, I\'d just gotten sober and I was just this raw nerve—I was burgeoning with anxiety,” she tells Apple Music. “And on this record, it sounds so boring, but I really feel like I was searching for normal. I think I\'ve really settled into my thirties.” Working again with longtime producer Brad Cook (Bon Iver, Snail Mail, Hurray for the Riff Raff), Crutchfield enlisted the help of rising guitar hero MJ Lenderman, with whom she duets on the quietly romantic lead single (and future classic) “Right Back to It.” Originally written for Wynonna Judd—a recent collaborator—“365” finds Crutchfield falling into a song of forgiveness, her voice suspended in air, arching over the soft, heart-like thump of an acoustic guitar. Just as simple but no less moving: the Southern rock of “Ice Cold,” in which Crutchfield seeks equilibrium and Lenderman transcendence, via solo. In the absence of inner tumult, Crutchfield says she had to learn that the songs will still come. “I really do feel like I\'ve reached this point where I have a comfort knowing that they will show up,” she says. “When it\'s time, they\'ll show up and they\'ll show up fast. And if they\'re not showing up, then it\'s just not time yet.”

Perhaps more so than any other Irish band of their generation, Fontaines D.C.’s first three albums were intrinsically linked to their homeland. Their debut, 2019’s *Dogrel*, was a bolshy, drizzle-soaked love letter to the streets of Dublin, while Brendan Behan-name-checking follow-up *A Hero’s Death* detailed the group’s on-the-road alienation and estrangement from home. And 2022’s *Skinty Fia* viewed Ireland from the complicated perspective of no longer actually being there. On their fourth album, however, Fontaines D.C. have shifted their attention elsewhere. *Romance* finds the five-piece wandering in a futuristic dystopia inspired by Japanese manga classic *Akira*, Paolo Sorrentino’s 2013 film *La Grande Bellezza*, and Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn’s *Pusher* films. “We didn’t set out to make a trilogy of albums but that’s sort of what happened,” drummer Tom Coll tells Apple Music of those first three records. “They were such a tight world, and this time we wanted to step outside of it and change it up. A big inspiration for this record was going to Tokyo for the first time. It’s such a visual, neon-filled, supermodern city. It was so inspiring. It brought in all these new visual references to the creative process for the first time.” Recorded with Arctic Monkeys producer James Ford (their previous three albums were all made with Dan Carey), *Romance* also brings in a whole new palette of sounds and colors to the band’s work. From the clanking apocalyptic dread of the opening title track, hip-hop-inspired first single “Starburster,” and the warped grunge and shoegaze hybrids of “Here’s the Thing” and “Sundowner,” it opens a whole new chapter for Fontaines D.C., while still finding time for classic indie rock anthems such as “Favourite”’s wistful volley of guitars or the Nirvana-like “Death Kink.” “Every album we do feels like a huge step in one direction for us, but *Romance* is probably a little bit more outside of our previous records,” says Coll. “It’s exciting to surprise people.” Read on as he dissects *Romance*, one track at a time. **“Romance”** “This is one that we wrote really late at night in the studio. It just fell out of us. It was one of those real moments of feeling, ‘Right, that’s the first track on the album.’ It’s kind of like a palate cleanser for everything that’s come before. It’s like the opening scene. I feel like every time we’ve done a record there’s been one tune that’s always stuck out like, ‘This is our opening gambit...’” **“Starburster”** “Grian \[Chatten, singer\] wrote most of this tune on his laptop, so there were lots of chopped-up strings and stuff—it was quite a hip-hop creative process. It’s probably the song that is furthest away from the old us on this album. This tune was the first single and we always try and shock people a bit. It’s fun to do that.” **“Here’s the Thing”** “This was written in the last hour of being in the studio. We had maybe 12 or 13 tracks ready to go and just started jamming, and it presented itself in an hour. \[Guitarist Conor\] Curley had this really gnarly, ’90s, piercing tone, and it just went from there.” **“Desire”** “This has been knocking around for ages. It was one of those tunes that took so many goes to get to where it was meant to sit. It started as a band setup and then we went really electronic with it. Then in the studio, we took it all back. It took a while for it to sit properly. Grian did 20 or 30 vocal layers on that, he really arranged it in an amazing way. Carlos \[O’Connell, guitarist\] and Grian were the main string arrangers on this record. This was the first record where we actually got a string quartet in—before, people would just send it over. So being able to sit in the room and watch a string quartet take center stage on a song was amazing.” **“In the Modern World”** “Grian wrote this song when he was in LA. He was really inspired by Lana Del Rey and stuff like that. Hollywood and the glitz and the glamour, but it’s actually this decrepit place. It’s that whole idea of faded glamour.” **“Bug”** “This felt like a really easy song for us to write. That kind of buzzy, all-of-us-in-the-same-room tune. I really fought for this one to be on the record. I feel like, with songs like that, trying to skew them and put a spin on them that they don’t need is overwriting. If it feels right then there’s no point in laboring over it. That song is what it is and it’s great. It’s going to be amazing live.” **“Motorcycle Boy”** “This one is inspired by The Smashing Pumpkins a bit. We actually recorded it six months before the rest of the album. This tune was the real genesis of the record and us finding a path and being like, ‘OK, we can explore down here...’ That was one that really set the wheels in motion for the album. It really informed where we were going.” **“Sundowner”** “On this album, we were probably coming from more singular points than we have before. A lot of the lads brought in tunes that were pretty much there. I was sharing a room with Curley in London, and he was working on this really shoegaze-inspired tune for ages. I think he always thought that Grian would sing it, but when he put down the guide vocals in the studio it sounded great. We were all like, ‘You are singing this now.’” **“Horseness Is the Whatness”** “Carlos sent me a demo of that tune ages and ages ago. It was just him on an acoustic, and it was such a powerful lyric. I think it’s amazing. We had to kind of deconstruct it and build it back up again in terms of making it fit for this record. Carlos had made three or four drum loops for me and it was a really fun experience to try and recreate that. I don’t know how we’re going to play it live but we’ll sort it out!” **“Death Kink”** “Again, this came from one of the jams of us setting up for a studio session. It’s another one of those band-in-a-room-jamming-out kind of tunes. On tour in America, we really honed where everything should sit in the set. This is going to be such a fun tune to play live. We’ve started playing it already and it’s been so sick.” **“Favourite”** “‘Favourite’ was another one we wrote when we were rehearsing. It happened pretty much as it is now. We were kind of nervous about touching it again for the album because that first recording was so good. That’s the song that hung around in our camp for the longest. When we write songs on tour, often we end up getting bored of them over time but ‘Favourite’ really stuck. We had a lot of conversations about the order on this album and I felt it was really important to move from ‘Romance’ to ‘Favourite.’ It feels like a journey from darkness into light, and finishing on ‘Favourite’ leaves it in a good spot.”

The idea of method acting is that you “become” the character you’re playing and the lines between self and acting dissolve. On Nilüfer Yanya’s third album, she’s been considering how that relates to her own work. “There’s a parallel between not acting anymore and my relationship with music and writing and performing,” the London singer-songwriter says. “I don’t really feel like I do a performance, so I don’t really feel like I’m trying to be someone else. That’s why I find performing quite challenging sometimes because I just have to be myself on stage; there’s no costume or masks that I put on.” Maybe that’s why on *My Method Actor* things are getting a bit existential. The excitement of her debut—2019’s *Miss Universe*—and the desire to push against it by doing something totally different with 2022 follow-up *PAINLESS* had left her in a jarring place when she and her collaborator, producer Wilma Archer, got into the studio. Writing music was not glamorous, it was simply her job and her life. “It’s a weird one making a third album, because it’s like: ‘What is pushing me to do this?’” she says. “Where is that desire coming from? Where am I going with this? Where am I going to be on the other side of this?” But this is an album that revels in ruminating on these heavy questions, and we hear an artist—and a person—growing as a result. Teeming with beautiful, accomplished melodies, the album waxes and wanes between scuzzier sounds of frustration and something far more polished and freeing. “It’s a journey, but you don’t really know where it’s going,” she says. “But it’s about not worrying too much about the outcome; it’s learning to trust myself, to really listen to myself.” Across *My Method Actor*, Yanya dredges through all the feelings and upheavals, realizing that there might not be a linear, clear-cut happy ending. “Maybe it’s about letting go. Maybe there’ll never be a point where I feel totally comfortable on stage—or even being a person,” she says, laughing. “These transformations and realizations will happen so often you can’t let it upturn your whole world every time. You have to take it as it comes.” Read on as she guides us through that journey, track by track. **“Keep on Dancing”** “It feels like an introduction. It nearly didn’t make it to the album—it was going really well but it kind of hit a wall towards the end where it wasn’t leveling up the way some of the other songs were, so we restructured it. It starts by asking lots of questions, it sets up the tone of the record. There’s a bit of anger, a bit of resentment. It doesn’t feel like it’s trying too hard to be clever, it’s more like a natural flow of ideas. It’s an energy.” **“Like I Say (I runaway)”** “I had a really fun time writing over the initial idea that Will \[Archer\] had sent me, making all the bits fall in the right place, picking up on the instinctive harmonies and the rhythm of it. The chorus took us both by surprise—it took a while, it felt like it was gonna be really instant but it kept falling on its face. It’s quite a simple structure but the phrasing of it makes it interesting.” **“Method Actor”** “I felt like I was definitely constructing a character in my head, imagining I was in someone else’s life. It was like you’re a flower on the wall, but you’re the narrator at the same time. Feelings of anxiety, social anxiety…it also feels a bit violent to me. There’s a lot of violent imagery and it sounds a bit aggressive. It’s kind of like a dance in the first verse and then the chorus hits you, the guitar wakes you up. It’s quite visceral. There’s always a kind of release that comes with writing something a bit more aggressive. I try not to be an aggressive person, so maybe this is a nice way of letting it out. It feels a bit cathartic.” **“Binding”** “It started with the guitar loop which you hear first. ‘Binding’ was actually the demo name for this, but it really stuck with us because it sounds like a constant loop, constant binding, something twisting and turning. It was really instantly very pretty, and it was enjoyable trying to come up with melodies. It feels like you’re needing something more, wanting something more—something strong to numb the pain, or something stronger to feel. Like you’re numbing yourself on this weird journey. I always imagine it like you’re in a car, and the road’s going on and on and on—and it’s not necessarily an enjoyable journey.” **“Mutations”** “This one, I always imagine a siren—there’s kind of a warning going out. You’re being told to take cover or escape. There’s an urgency in the music and the message. Before the sunset, before the end of the day, before the lights, you need to find a way to disappear or to hide. It’s dark, but in the song you’re either receiving or sending the message—so you’re trying to help somebody, or they’re trying to help you. So there’s something nice about that. But there’s something sinister about the reality the song is set in—it’s very rhythmic, there’s not very many breaks, it’s tight and enclosed.” **“Ready for Sun (touch)”** “The song itself is quite cinematic—it’s sonically quite different to what’s come before, it’s a bit more modern, less grungy. It’s about being ready to step outside again, ready to be less concealed, more exposed. You wanna feel sun on your skin when you’ve been in the shade too long. I say ‘exposed,’ but also it’s about feeling safe enough to come out into the open. It’s wanting to feel touch again, wanting to feel things again. It’s raw feeling, raw emotion.” **“Call It Love”** “I was thinking about a phoenix bursting into flames. Metamorphosis. There’s a lot of talk about flames and fire in this album, but this one definitely fits with the journey themes of the record too. There’s a deep knowing that it’s OK to trust yourself and what you know to be true. It’s being your own guide. You have a sense of self and, even if it’s blurry, you have a center. The overlap of desire and shame, too—how we sometimes feel ashamed of acting on our desires. So the phoenix comes to mind because it’s about allowing your calling to guide you somewhere, to let that consume you and destroy you so you are born out from the ashes. It’s a bit dramatic. But sonically, it’s a lot more chilled out, there’s a groove to the way the guitars intertwine.” **“Faith’s Late”** “I feel like a lot of the questions I ask are quite intense, so I almost want to avoid it. This one is talking about identity. Even the word ‘faith’ feels quite loaded. It’s about belonging, or not belonging, to somewhere—never feeling like you belong somewhere. Always feeling like you’re in the wrong place at the wrong time. It’s also about being disappointed in the state of the world, and sort of wanting to give up. But the string arrangement at the end is particularly beautiful, I think. In contrast to the themes, you’re trying to make something beautiful out of something you’d prefer to avoid. And so there’s still life, there’s still beauty, even continuing out of the mess.” **“Made Out of Memory”** “This has a lighter touch. It has an ’80s pop kind of feel production-wise, but the core lyric is based off someone saying how humans are just made up of memories of other people. So when you’re trying to leave somebody behind or breaking up with somebody, if you’re not seeing someone anymore—even a friend or a family member—it’s kind of hacking off a piece of yourself each time. How do you break up with somebody without breaking up with yourself? There’s an art to that.” **“Just a Western”** “I remember Will sent me the guitar ages ago and I really liked it, but nothing was automatically clicking. But I liked the unusual chord pattern. I was thinking of the old Western movies that would come on daytime TV when I was younger. They’d be black-and-white films, cowboys riding off into the sunset. This song has that imagery in it for me; the sunset, something ending. One of the lyrics that jumps out for me is ‘I won’t call in a favour/Won’t do it for free anymore.’ It’s saying you’re not going to do somebody else’s dirty work for them, you’re stating your own new boundaries.” **“Wingspan”** “We were originally trying to make a full song, and it wasn’t really working in a long-form way. Realizing that the song was maybe a condensed version makes it more impactful. I don’t really write short songs like this. A lot of the lyrics are based on this poetry attempt from a couple years ago—so it was like a puzzle coming together, finally having a place for these words to go. It’s about realizing that you’ve ended up somewhere but it’s a port for another place to take off—are arrivals and departures the same thing?”

The Smile, a trio featuring Radiohead prime movers Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood along with ex-Sons of Kemet drummer Tom Skinner, sounds more like a proper band than a side project on their second album. Sure, they’re a proper band that unavoidably sounds a *lot* like Radiohead, but with some notable distinctions—much leaner arrangements, bass parts by Greenwood and Yorke with a very different character from what Radiohead bassist Colin Greenwood might have laid down, and a formal fixation on conveying tension in their melodies and rhythms. Their debut, *A Light for Attracting Attention*, was full of tight, wrenching grooves and guitar parts that sounded as though the strings were coiling into knots. This time around they head in the opposite direction, loosening up to the point that the music often feels extremely light and airy. The guitar in the first half of “Bending Hectic” is so delicate and minimal that it sounds like it could get blown away with a slight breeze, while the warm and lightly jazzy “Friend of a Friend” feels like it’s helplessly pushed and pulled along by strong, unpredictable winds. The loping rhythm and twitchy riffs in “Read the Room” are surrounded by so much negative space that it sounds eerily hollow, like Yorke is singing through the skeletal remains of a ’70s metal song. There are some surprises along the way, too. A few songs veer into floaty lullaby sections, and more than half include orchestral tangents that recall Greenwood’s film score work for Paul Thomas Anderson and Jane Campion. The most unexpected moment comes at the climax of “Bending Hectic,” which bursts into heavy grunge guitar, stomping percussion, and soaring vocals. Most anyone would have assumed Yorke and Greenwood had abandoned this type of catharsis sometime during the Clinton administration, but as it turns out they were just waiting for the right time to deploy it.

In a short time, Claire Cottrill has become one of pop music’s most fascinating chameleons. Even as her songwriting and soft vocals often possess her singular touch, the prodigious 25-year-old has exhibited a specific creative restlessness in her sonic approach. After pivoting from the lo-fi bedroom pop of her early singles to the sounds of lush, rustic 2000s indie rock on 2019’s star-making *Immunity* and making a hard pivot towards monastic folk on 2021’s *Sling*, the baroque, ’70s soul-inflected chamber-pop that makes up her third album, *Charm*, feels like yet another revelation in an increasingly essential catalog. *Charm* is Cottrill’s third consecutive turn in the studio with a producer of distinctive aesthetic; while *Immunity*’s flashes of color were provided by Rostam Batmanglij and Jack Antonoff worked the boards on *Sling*, these 11 songs possess the undeniable warmth of studio impresario and Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings founding member Leon Michels. Along with several Daptone compatriots and NYC jazz auteur Marco Benevento, Michels provides the perfect support to Cotrill’s wistful, gorgeously tumbling songcraft; woodwinds flutter across the squishy synth pads of “Slow Dance,” while “Echo” possesses an electro-acoustic hum not unlike legendary UK duo Broadcast and the simmering soul of “Juna” spirals out into miniature psychedelic curlicues. At the center of it all is Cottrill’s unbelievably intimate vocal touch, which perfectly captures and complements *Charm*’s lyrical theme of wanting desire while staring uncertainty straight in the eye.

It’s no surprise that “PARTYGIRL” is the name Charli xcx adopted for the DJ nights she put on in support of *BRAT*. It’s kind of her brand anyway, but on her sixth studio album, the British pop star is reveling in the trashy, sugary glitz of the club. *BRAT* is a record that brings to life the pleasure of colorful, sticky dance floors and too-sweet alcopops lingering in the back of your mouth, fizzing with volatility, possibility, and strutting vanity (“I’ll always be the one,” she sneers deliciously on the A. G. Cook- and Cirkut-produced opening track “360”). Of course, Charli xcx—real name Charlotte Aitchison—has frequently taken pleasure in delivering both self-adoring bangers and poignant self-reflection. Take her 2022 pop-girl yet often personal concept album *CRASH*, which was preceded by the diaristic approach of her excellent lockdown album *how i’m feeling now*. But here, there’s something especially tantalizing in her directness over the intoxicating fumes of hedonism. Yes, she’s having a raucous time with her cool internet It-girl friends, but a night out also means the introspection that might come to you in the midst of a party, or the insurmountable dread of the morning after. On “So I,” for example, she misses her friend and fellow musician, the brilliant SOPHIE, and lyrically nods to the late artist’s 2017 track “It’s Okay to Cry.” Charli xcx has always been shaped and inspired by SOPHIE, and you can hear the influence of her pioneering sounds in many of the vocals and textures throughout *BRAT*. Elsewhere, she’s trying to figure out if she’s connecting with a new female friend through love or jealousy on the sharp, almost Uffie-esque “Girl, so confusing,” on which Aitchison boldly skewers the inanity of “girl’s girl” feminism. She worries she’s embarrassed herself at a party on “I might say something stupid,” wishes she wasn’t so concerned about image and fame on “Rewind,” and even wonders quite candidly about whether she wants kids on the sweet sparseness of “I think about it all the time.” In short, this is big, swaggering party music, but always with an undercurrent of honesty and heart. For too long, Charli xcx has been framed as some kind of fringe underground artist, in spite of being signed to a major label and delivering a consistent run of albums and singles in the years leading up to this record. In her *BRAT* era, whether she’s exuberant and self-obsessed or sad and introspective, Charli xcx reminds us that she’s in her own lane, thriving. Or, as she puts it on “Von dutch,” “Cult classic, but I still pop.”

At just 25 years old, with four solo studio albums and three as guitarist for North Carolina band Wednesday under his belt, MJ Lenderman already seems like an all-timer. The vivid, arch songwriting, the swaying between reverence and irreverence for his forebears, steeped in modern culture while still sounding timeless—he evokes the easy comfort of a well-worn favorite and the butterflies of a new relationship with someone who is going to have a massive, rich, and argued-about discography for decades. The songs go down easy but are dark around the edges, with down-home strings and lap steel adorning tales of jerking off into showers and the existential loneliness of a smartwatch. But in a fun way. And just as 2021’s “Knockin” both referenced erstwhile golfer John Daly’s cover of Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” and lifted its chorus for good measure, “You Don’t Know the Shape I’m In” honors The Band’s classic while rendering it redundant. But album closer “Bark at the Moon” represents Lenderman’s blending of sad-sack character sketches and meta classic-rock references in its final form: “I’ve never seen the Mona Lisa/I’ve never really left my room/I’ve been up too late with Guitar Hero/Playing ‘Bark at the Moon.’” Then he punctuates the line with an “Awoo/Bark at the moon,” not to the tune of the Ozzy song, but to Warren Zevon’s “Werewolves of London.” Packing that many jokes into half a verse is impressive enough—more so that the impact is even more heartbreaking than it is funny.

Few artists have done more for carrying the banner of guitar rock proudly into the 21st century than St. Vincent. A notorious shredder, she cut her teeth as a member of Sufjan Stevens’ touring band before releasing her debut album *Marry Me* in 2007. Since then, her reputation as a six-string samurai has been cemented in the wake of a run of critically acclaimed albums and collaborations (she co-wrote Taylor Swift’s No 1. single “Cruel Summer”). A shape-shifter of the highest order, St. Vincent, aka Annie Clark, has always put visual language on equal footing with her sonic output. Most recently, she released 2021’s *Daddy’s Home*, a conceptual period piece that pulled inspiration from ’70s soul and glam set in New York City. That project marked the end of an era visually—gone are the bleach-blonde wigs and oversized Times Square-ready trench coats—as well as creatively. With *All Born Screaming*, she bids adieu to frequent collaborator Jack Antonoff, who produced *Daddy’s Home*, and instead steps behind the boards for the first time to produce the project herself. “For me, this record was spending a lot of time alone in my studio, trying to find a new language for myself,” Clark tells Apple Music’s Hanuman Welch. “I co-produced all my other records, but this one was very much my fingerprints on every single thing. And a lot of the impetus of the record was like, ‘Okay: I\'m in the studio and everything has to start with chaos.’” For Clark, harnessing that chaos began by distilling the elemental components of what makes her sound like, well, her. Guitar players, in many respects, are some of the last musicians defined by the analog. Pedal boards, guitar strings, and pass-throughs are all manipulated to create a specific tone. It’s tactile, specialized, and at times, yes, chaotic. “What I mean by chaos,” Clark says, “is electricity actually moving through circuitry. Whether it\'s modular synths or drum machines, just playing with sound in a way that was harnessing chaos. I\'ve got six seconds of this three-hour jam, but that six seconds is lightning in a bottle and so exciting, and truly something that could only have happened once and only happened in a very tactile way. And then I wrote entire songs around that.” Those songs cover the spectrum from sludgy, teeth-vibrating offerings like “Flea” all the way to the lush album cut (and ode to late electronic producer SOPHIE) “Sweetest Fruit.” Clark relished in balancing these light and dark sounds and sentiments—and she didn’t do so alone. “I got to explore and play and paint,” she says. “And I also luckily had just great friends who came in to play on the record and brought their amazing energy to it.” *All Born Screaming* features appearances from Dave Grohl, Warpaint’s Stella Mozgawa, and Welsh artist Cate Le Bon, among others. Le Bon pulled double duty on the album by performing on the title track as well as offering clarity for some of the murkier production moments. “I was finding myself a little bit in the weeds, as everyone who self-produces does,” Clark says. “And so I just called Cate and was like, ‘I need you to just come hold my hand for a second.’ She came in and was a very stabilizing force, I think, at a time in the making of the record when I needed someone to sort of hold my hand and pat my head and give me a beer, like, ‘It\'s going to be okay.’” With *All Born Screaming*, Clark manages to capture the bloody nature of the human experience—including the uncertainty and every lightning-in-a-bottle moment—but still manages to make it hum along like a Saturday morning cartoon. “The album, to me, is a bit of a season in hell,” she says. “You are a little bit walking on your knees through some broken glass—but in a fun way, kids. We end with this sort of, ‘Yes, life is difficult, but it\'s so worth living and we\'ve got to live it. Can\'t go over it, can\'t go under it, might as well go through it.’ It\'s black and white and the colors of a fire. That, to me, is sonically what the record is.”

There’s a sense of optimism that comes through Vampire Weekend’s fifth album that makes it float, a sense of hope—a little worn down, a little roughed up, a little tired and in need of a shave, maybe—but hope nonetheless. “By the time you’re pushing 40, you’ve hit the end of a few roads, and you’re probably looking for something—I don’t know what to say—a little bit deeper,” Ezra Koenig tells Apple Music. “And you’re thinking about these ideas. Maybe they’re corny when you’re younger. Gratitude. Acceptance. All that stuff. And I think that’s infused in the album.” Take something like “Mary Boone,” whose worries and reflections (“We always wanted money, now the money’s not the same”) give way to an old R&B loop (Soul II Soul’s “Back to Life”). Or the way the piano runs on “Connect”—like your friend fumbling through a Gershwin tune on a busted upright in the next room—bring the song’s manic energy back to earth. Musically, they’ve never sounded more sophisticated, but they’ve also never sounded sloppier or more direct (“Prep-School Gangsters”). They’re a tuxedo with ripped Converse or a garage band with a full orchestra (“Ice Cream Piano”). And while you can trainspot the micro-references and little details of their indie-band sound (produced brilliantly by Koenig and longtime collaborator Ariel Rechtshaid), what you remember most is the big picture of their songs, which are as broad and comforting as great pop (“Classical”). “Sometimes I talk about it with the guys,” Koenig says. “We always need to have an amateur quality to really be us. There needs to be a slight awkward quality. There needs to be confidence and awkwardness at the same time.” Next to the sprawl of *Father of the Bride*, *OGWAU* (“og-wow”—try it) feels almost like a summary of the incredible 2007-2013 run that made them who they are. But they’re older now, and you can hear that, too, mostly in how playful and relaxed the album is. Listen to the jazzy bass and prime-time saxophone on “Classical” or the messy drums on “Prep-School Gangsters” (courtesy of Blood Orange’s Dev Hynes), or the way “Hope” keeps repeating itself like a school-assembly sing-along. It’s not cool music, which is of course what makes it so inimitably cool. Not that they seem to worry about that stuff anymore. “I think a huge element for that is time, which is a weird concept,” Koenig says. ”Some people call it a construct. I’ve heard it’s not real. That’s above my pay grade, but I will say, in my experience, time is great because when you’re bashing your head against the wall, trying to figure out how to use your brain to solve a problem, and when you learn how to let go a little bit, time sometimes just does its thing.” For a band that once announced themselves as the preppiest, most ambitious guys in the indie-rock room, letting go is big.

Few genres feel as inherently collaborative as jazz, and even fewer contemporary artists embody that spirit quite like Kamasi Washington. After bringing a whole new generation of listeners to jazz through his albums *The Epic* and *Heaven and Earth*, as well as his collaborations with Kendrick Lamar, the Los Angeles native and saxophonist amassed an impressively eclectic set of guests to join his forthcoming bandleader project *Fearless Movement*. Among the guests were Los Angeles rapper D Smoke and funk legend George Clinton, who joined him for “Get Lit.” “That was definitely a beautiful moment,” Washington tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “The sessions were magical; it was like being in a studio with just geniuses.” Originally written by Washington’s longtime drummer Ronald Bruner Jr. (also known as the brother of bass virtuoso Thundercat), “Get Lit” sat around for a bit before the divine inspiration struck to invite Clinton and D Smoke to build upon it. After Washington attended the former’s art exhibition and the latter’s Hollywood Bowl concert in Los Angeles, it couldn’t have been clearer to him who the band needed to make the song shine. Washington compares Clinton’s involvement to magic, marveling in the studio at just how the Parliament-Funkadelic icon operates. “It\'s like we\'re listening to it and he\'s living in it,” he says, conveying how natural it felt having him participate. “When he decides to add something to some music, it\'s like water.” As for D Smoke, Washington was so impressed by the two-time Grammy nominee’s sense of musicality. “He plays keys, he understands harmony, and all that other stuff. He just knew exactly what to do.” As implied by “Get Lit,” the contributors on *Fearless Movement* come from varied backgrounds and scenes, from the modern R&B styles of singer BJ the Chicago Kid to the shape-shifting sounds of Washington’s *To Pimp a Butterfly* peer Terrace Martin. Still, the name that will stand out for many listeners is André 3000, who locked in with the band on the improvisational piece “Dream State.” The Outkast rapper turned critically acclaimed flautist arrived with a veritable arsenal of flutes, inspiring all the players present. “André has one of the most powerful creative spirits that I\'ve ever experienced,” Washington says. “We just created that whole song in the moment together without knowing where we was going.” Allowing himself to give in to the uncertainty and promise of that particular moment succinctly encapsulates the wider ethos behind all of *Fearless Movement*. “A lot of times, I feel like you can get stuck holding on to what you have because you\'re unwilling to let it go,” he says. “This album is really speaking on that idea of just being comfortable in what you are and where you want to go.”

Where the ’60s-ish folk singer Jessica Pratt’s first few albums had the insular feel of music transmitted from deep within someone’s psyche, *Here in the Pitch* is open and ready—cautiously, gently—to be heard. The sounds aren’t any bigger, nor are they jockeying any harder for your attention. (There is no jockeying here, this is a jockey-free space.) But they do take up a little more room, or at least seem more comfortable in their quiet grandeur—whether it’s the lonesome western-movie percussion of “Life Is” or the way the featherlight *sha-la-la*s of “Better Hate” drift like a dazzled girl out for a walk among the bright city lights. This isn’t private-press psychedelia anymore, it’s *Pet Sounds* by The Beach Boys and the rainy-day ballads of Burt Bacharach—music whose restraint and sophistication concealed a sense of yearning rock ’n’ roll couldn’t quite express (“World on a String”). And should you worry that her head is in the clouds, she levels nine blows in a tidy, professional 27 minutes. They don’t make them like they used to—except that she does.

It can be dangerous, Nick Cave says, to look back on one’s body of work and seek meaning in the music you’ve made. “Most records, I couldn\'t really tell you by listening what was going on in my life at the time,” he tells Apple Music. “But the last three, they\'re very clear impressions of what life has actually been like. I was in a very strange place.” In the years following the 2015 death of his son Arthur, Cave’s work—in song; in the warm counsel of his newsletter, The Red Hand Files; in the extended conversation-turned-book he wrote with journalist Seán O’Hagan, *Faith, Hope and Carnage*—has been marked by grief, meeting unimaginable loss with more imagination still. It’s made for some of the most remarkable and moving music of his nearly 50-year career, perhaps most notably the feverish minimalism of 2019’s *Ghosteen*, which he intended to act as a kind of communique to his dead son, wherever he might be. Though Cave would lose another son, Jethro, in 2022, *Wild God* finds the 66-year-old singer-songwriter someplace new, marveling at the beauty all around him, reuniting with The Bad Seeds, who—with the exception of multi-instrumentalist songwriting foil Warren Ellis—had slowly receded from view. Once a symbol of post-punk antipathy, he is now open to the world like never before. “Maybe there is a feeling like things don\'t matter in the same way as perhaps they did before,” he says. “These terrible things happened, the world has done its worst. I feel released in some way from those sorts of feelings. *Wild God* is much more playful, joyous, vibrant. Because life is good. Life is better.” It’s an album that feels like an embrace. That much you can hear in the first seconds of “Song of the Lake,” a swirl of ascendant synths and thick, chewy bass (compliments of Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood) upon which Cave tells a tale of brokenness that never quite resolves, as though to fully heal or be put back together again has never really been the point of all this, of being human. The mood is largely improvisational and loose, Cave leaning into moments of catharsis like a man who’d been waiting for them. He offers levity (the colossal, delirious title track) and light (“Frogs,” “Final Rescue Attempt”). On “O Wow O Wow (How Wonderful She Is),” a tribute to the late Anita Lane, his former creative and romantic partner, he conjures a sense of play that would have seemed impossible a few years ago. “I think that it\'s just an immense enjoyment in playing,” he says of the band\'s influence on the album. “I think the songs just have these delirious, ecstatic surges of energy, which was a feeling in the studio when we recorded it. We\'re not taking it too seriously in a way, although it\'s a serious record. We were having a good time. I was having a really good time.” There is no shortage of heartbreak or darkness to be found here. But “Joy,” the album’s finest moment (and original namesake), is a monument to optimism, a radical thought. For six minutes, he sounds suspended in twilight, pulling words out of thin air, synths fluttering and humming and flickering around him, peals of piano and French horn coming and going like comets. “We’ve all had too much sorrow, now is the time for joy,” he sings, quoting a ghost who’s come to his bedside, a “flaming boy” in sneakers. “Joy doesn\'t necessarily mean happiness,” Cave says upon reflection. “Joy in a way is a form of suffering, in the sense that it understands the notion of suffering, and it\'s these momentary ecstatic leaps we are capable of that help us rise out of that suffering for a moment of time. It is sort of an explosion of positive feeling, and I think the record\'s full of that, full of these moments. In fact, the record itself is that.” While that may sound like a complete departure from its most recent predecessors, *Wild God* shares a similar intention, an urge to communicate with his late children, from this world to theirs. That may never fade. “If there\'s one impulse I have, it’s that I would like my kids who are no longer with us to know that we are okay, that \[wife\] Susie and I are okay,” Cave says. “I think that\'s why when I listened to the record back, I just listened to it with a great big smile on my face. Because it\'s just full of life and it\'s full of reasons to be happy. I think this record can definitely improve the condition of my children. All of the things that I create these days are an attempt to do that.” Read on as Cave takes us inside a few highlights from the album: **“Wild God”** “I was actually going to call the record *Joy*, but chose *Wild God* in the end because I thought the word ‘joy’ may be misunderstood in a way. ‘Wild God’ is just two pieces of music chopped together—an edit. That song didn\'t really work quite right. So we thought, ‘Well, let\'s get someone else to mix it.’ And me and Warren thought about that for a while. I personally really loved the sound of \[producer Dave Fridmann’s work with\] MGMT, and The Flaming Lips, stuff—it had this immediacy about it that I really liked. So we went to Buffalo with the recordings and Dave did a song each day, disappeared into the control room and mixed it without inviting us in. It was the strangest thing. And then he emerges from the studio and says, ‘Come in and tell me what you think.’ When we came in it sounded so different. We were shocked. And then after we played it again, we heard that he traded in all the intricacies and stateliness of The Bad Seeds for just pure unambiguous emotion.” **“Frogs”** “Improvising and ad-libbing is still very much the way we go about making music. ‘Frogs’ is essentially a song that I had some words to, but I just walked in and started singing over the top of this piece of music that we\'d constructed without any real understanding of the song itself. There\'s no formal construction—it just keeps going, very randomly. There\'s a sort of freedom and mystery to that stuff that I find really compelling. I sang it as a guide, but listening to it back was like, ‘Wow, I don\'t know how to go and repeat that in any way, but it feels like it\'s talking about something way beyond what the song initially had to offer.’” **“Joy”** “‘Joy’ is a wholly improvised one-take without me having any real understanding of what Warren is doing musically. It’s written in that same questing way of first takes. I\'m just singing stuff over a kind of chord pattern that he\'s got. I sort of intuit it in some way that it’s a blues form to it, so I’m attempting to sing a blues vocal over the top, rhyming in a blues tradition.” **“Final Rescue Attempt”** “That was a song that we weren\'t putting on the record. It was a late addition, just hanging around. And I think Dave Fridmann actually said, ‘Look, I\'ve mixed this song. It doesn\'t seem to be on the record. What the fuck?’ It feels a little different in a way to me. But it\'s a very beautiful song, very beautiful. And I guess it was just so simple in its way, or at least the first verse literally describes the situation that I think is actually in the book, *Faith, Hope and Carnage*, where Susie decided to come back to me after eight months or so, and rode back to my house where I was living, on a bicycle. It’s a depiction of that scene, so maybe I shied away from it for that reason. I don\'t know. But I\'m really glad.” **“O Wow O Wow (How Wonderful She Is)”** “That song is an attempt to encapsulate what Anita Lane was like, and we all loved her very much and were all shocked to the core by her death. In her early days when we were together, she was this bright, shiny, happy, laughing, flaming thing, and we were the dark, drug-addicted men that circled around her. And I wanted to just write a song that had that. She was a laughing creature, and I wanted to work out a way of expressing that. It\'s such a beautifully innocent song in a way.”

Listening to Adrianne Lenker’s music can feel like finding an old love letter in a library book: somehow both painfully direct and totally mysterious at the same time, filled with gaps in logic and narrative that only confirm how intimate the connection between writer and reader is. Made with a small group in what one imagines is a warm and secluded room, *Bright Future* captures the same folksy wonder and open-hearted intensity of Big Thief but with a slightly quieter approach, conjuring visions of creeks and twilights, dead dogs (“Real House”) and doomed relationships (“Vampire Empire”) so vivid you can feel the humidity pouring in through the screen door. She’s vulnerable enough to let her voice warble and crack and confident enough to linger there for as long as it takes to get her often devastating emotional point across. “Just when I thought I couldn’t feel more/I feel a little more,” she sings on “Free Treasure.” Believe her.

As someone who invited fame and courted infamy, first with inflammatory albums like *Wolf* and later with his flamboyant fashion sense via GOLF WANG, Tyler Okonma is less knowable than most stars in the music world. While most celebrities of his caliber and notoriety either curate their public lives to near-plasticized extremes or become defined by tabloid exploits, the erstwhile Odd Futurian chiefly shares what he cares to via his art and the occasional yet ever-quotable interview. As his Tyler, The Creator albums pivoted away from persona-building and toward personal narrative, as on the acclaimed *IGOR* and *CALL ME IF YOU GET LOST*, his mystique grew grandiose, with the undesirable side effect of greater speculation. The impact of fan fixation plays no small part on *CHROMAKOPIA*, his seventh studio album and first in more than three years. Reacting to the weirdness, opening track “St. Chroma” finds Tyler literally whispering the details of his upbringing, while lead single “Noid” more directly rages against outsiders who overstep both online and offline. As on his prior efforts, character work plays its part, particularly on “I Killed You” and the two-hander “Hey Jane.” Yet the veil between truth and fiction feels thinner than ever on family-oriented cuts like “Like Him” and “Tomorrow.” Lest things get too damn serious, Tyler provocatively leans into sexual proclivities on “Judge Judy” and “Rah Tah Tah,” both of which should satisfy those who’ve been around since the *Goblin* days. When monologue no longer suits, he calls upon others in the greater hip-hop pantheon. GloRilla, Lil Wayne, and Sexyy Red all bring their star power to “Sticky,” a bombastic number that evolves into a Young Buck interpolation. A kindred spirit, it seems, Doechii does the most on “Balloon,” amplifying Tyler’s energy with her boisterous and profane bars. Its title essentially distillable to “an abundance of color,” *CHROMAKOPIA* showcases several variants of Tyler’s artistry. Generally disinclined to cede the producer’s chair to anyone else, he and longtime studio cohort Vic Wainstein execute a musical vision that encompasses sounds as wide-ranging as jazz fusion and Zamrock. His influences worn on stylishly cuffed sleeves, Neptunes echoes ring loudly on the introspective “Darling, I” while retro R&B vibes swaddle the soapbox on “Take Your Mask Off.”

IDLES’ fifth album is a collection of love songs. For singer Joe Talbot, it couldn’t be anything else. “At the time of writing this album, I was quite lost,” he tells Apple Music. “Not musically, it was a beautiful time for music. But emotionally, my nervous system needed organizing, and I needed to sort my shit out. So I did. That came from me realizing that I needed love in my life, and that I had sometimes lost my narrative in the art, which is that love is all I’ve ever sung about.” From a band wearied by other people’s attempts to pin narrow labels like “punk” or “political” to their expansive, thoughtful music, that’s as concise a summary as you’ll get. It’s also an accurate one. The Bristol five-piece’s music has always viewed the world with an empathetic eye, processing the human effects and impulses around subjects as varied as grief, immigration, kindness, toxic masculinity, and anxiety. And on their fourth album, 2021’s *CRAWLER*, the aggression and sinew of earlier songs gave way to more space and restraint as Talbot turned inward to reckon with his experiences with addiction. For *TANGK*, that experimentation continued while the band’s initial ideas were developed with Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich in London during late 2022, before the record was completed with *CRAWLER* co-producer Kenny Beats joining the team to record in the south of France. They’ve emerged with an album where an Afrobeat rhythm played out on an obscure drum machine (“Grace”) or a gentle piano melody recorded on an iPhone (“A Gospel”) hit with as much impact as a gale-force guitar riff (“Gift Horse”). Exploring the thrills and the scars of love in multiple forms, Talbot leans ever more into singing over firebrand fury. “I’ve got a kid now, and part of my learning is to have empathy when I parent,” he says. “And with that comes delicacy. To use empathy is a delicate and graceful act. And that’s coming out in my art, because I’m also being delicate and graceful with myself, forgiving myself, and giving myself time to learn. I don’t want to lie.” Discover more with Talbot’s track-by-track guide to *TANGK*. **“IDEA 01”** “It was the first thing \[guitarist and co-producer Mark\] Bowen worked on, and Bowen, being the egotistical maniac that he is, called it ‘IDEA 01’ because he forgot that it was actually idea seven. But, bless him, he does like attention. But, yes, it was the first song that was written in Nigel’s studio. Bowen sat at the piano and started playing, and it was beautiful. ‘IDEA 01’ is different vignettes around old friends that I haven’t seen since Devon \[where Talbot grew up\], and the relationships I had with them and their families, and how crazy certain people’s families are. Bowen’s beautiful piano part reminded me of this song we wrote on the last album, ‘Kelechi.’ Kelechi was a good friend of mine who sadly passed away, and I hadn’t seen him since I waved him off to move to Manchester with his family. I just had this feeling I was never going to see him again. Maybe I’m writing that in my head now, but he was a beautiful, beautiful man. I loved him. I think maybe if we were still friends, part of me could have helped him, but that’s, again, fantasy I think.” **“Gift Horse”** “I was trying to get this disco thing going, so I gave Jon \[Beavis, drummer\] a bunch of disco beats to work on. And Dev \[bassist Adam Devonshire\] is bang into The Rapture and !!! and LCD Soundsystem, and he turned out that bassline real quick. I wrote a song around it, and it felt great. It was what my intentions of the album were: to make people dance and not think, because love is a very complex thing that doesn’t need to be thought. It can just be acted, and worked on, and danced with. I just wanted to make people move, and get that physicality of the live experience in people’s bones. I had this concept of a gift horse as a theme of a song, and it sang to me. I like that grotesque phrase, ‘Never look a gift horse in the mouth.’ It’s about my daughter, and I’m very grateful for her, and our relationship, and I wanted to write a beast of a tune around her.” **“POP POP POP”** “I read \[‘freudenfreude’\] online somewhere. It was like, words that don’t exist that should exist. Schadenfreude is such a dark thing, to enjoy other people’s misery, so the idea of someone enjoying someone else’s joy is great. Being a parent, you suddenly are entwined with someone else’s joys and lows. I love seeing her dance, and have a good time, and grow as a person, and learn, so I wanted to write a song about it.” **“Roy”** “It’s an allegorical story that sums up a lot of my behavior towards my partners over a 15-year period where I was in a cycle of absolute worship and then fear, jealousy and assholery. I wanted to dedicate it to my girlfriend, who I call Roy. She’s not called Roy. I wanted it to be about the idea of a man who is in love and then his fears take over, and he starts acting like a prick to push that person away. Then he wakes up in the morning with a horrible hangover, realizing what he’s done, and he apologizes. He is then forgiven in the chorus, and rejoicing ensues.” **“A Gospel”** “It’s a reflection on breakups, which I think are a learning curve. I think all my exes deserve a medal, and they’ve taught me a lot. It’s really a tender moment of a dream I used to have, then \[it\] dances between different tiny memories, tiny vignettes of what happened before, and me just giving a nod to those moments and saying goodbye, which is beautiful. No heartbreak, really. I’ve been through the heartbreak now. It’s just me smiling and being like, ‘Yeah, you were right. Thank you very much.’” **“Dancer” (with LCD Soundsystem)** “The best form of dance is to express yourself freely within a group who are also expressing themselves freely, the true embodiment of communion. The last time I had this sense of euphoria from that was an Oh Sees gig at the \[Sala\] Apolo in Barcelona. I closed my eyes and let the mosh push me from one side of the room to the other and back. I didn’t open my eyes once, I just smiled and was carried by this organism of beautiful rage. Dancing’s a really big part of my personality. I love it. My mum always danced. Even in her most ill days \[Talbot’s mother passed away during the recording of 2017 debut *Brutalism*\], she would always get up and dance, and enjoy herself. I dance with my daughter every day that I have her. I think it’s magic and important.” **“Grace”** “It all came out of nowhere. I had this beat in mind for a while—I was thinking of an aggro Afrobeat kind of track. But it didn’t come out like that. It came out like what happens when Nigel Godrich gets his hands on your Afrobeat stuff. I asked Nigel to make the beat, and he chose the LinnDrum \[’80s drum machine\]. The LinnDrum changes the sound of a beat, the tone of a drum, the cadence of a beat, it changed the beat completely. It’s a very, very delicate thing, a beat. It sounded like a different song to me. It sounded amazing. And that’s where the bassline came from. And then that’s where the vocals came from. It felt a bit uneasy for a long time because it came out of nowhere. Me and Bowen were like, ‘Is this right? Is this complete?’ I think it just has to feel like you, like it is part of you and what you mean at the moment, that’s all. An album’s an episode of where you’re at in the world in that point in time.” **“Hall & Oates”** “I wanted to write a glam-rock pounder about falling in love with your boys. My ex and I used to joke about this thing where you make love to someone for the first time, and then the next day, you’re walking on air, and it feels like Hall & Oates is playing. The birds are singing, you’re bouncing around and everything’s great. I wanted to use that analogy for when you make friends with someone for the first time, and they make you feel good, lighter, stronger, excited to see them again. And that’s what happened in lockdown: I made friends with \[Bristol-based singer-songwriter\] Willie J Healey and my mate Ben, and we went on bike rides whenever we could, getting out and feeling good post-lockdown. It gave me a sense of purpose again. It felt like I was falling in love.” **“Jungle”** “I was trying to write a jungle tune for ages. The guitar line was a jungle bassline that I had but it just never fit what we were writing. And then Bowen started playing the chords on the guitar and it transformed it into something completely different. It completely revitalized what I’d been dragging through the mud for five years. Bowen made it IDLES, made it real, made it believable, made it beautiful. And then it reminded me of getting nicked, so I wrote a song about different times that I’ve been in trouble.” **“Gratitude”** “This was a real struggle. Bowen was really obsessed about doing interesting counts with the beats. I just wanted to make people dance and create infectious beats. We were coming from very different angles, but we loved this song that Bowen had made. I was like, ‘I get it, Bowen. This is insane. I love it, but I can’t get it.’ We hung on to it for ages, and then Nigel really helped us out, he created spaces and bits here and there by turning things down and moving everything slightly. Then Kenny helped me out, and got rid of the stupid counts, I think, and helped me write it on a 4/4 beat. And then they changed it back. I just come in in weird places. Everyone chipped in, because everyone believed in the song.” **“Monolith”** “I was fascinated by films where four or five notes are repeated throughout and create this monolithic motif. There’s a sense of continuity but the mood changes depending on certain things like tone and instruments. I wanted to do that over a song, and we got our friend Colin \[Webster\] from \[London noise rock unit\] Sex Swing to do the sax, we did it on different instruments that Nigel had. Nigel went away and basically put it all through the hollow-body bass. It reminded me of a documentary from a series called *The Blues* that Martin Scorsese curated. *The Soul of a Man* \[directed by Wim Wenders\] is about a song \[Blind Willie Johnson’s ‘Dark Was the Night’\] getting sent into space. If any aliens get this capsule, they’ll hear this song being played from a blues artist. It created a really beautiful and deep picture in my mind. It felt like this monolith drifting in the ether. I started singing a blues riff behind it, a Skip James kind of thing. I think it’s a beautiful way to finish the album—us drifting in the ether.”

With a career spanning four decades, Kim Deal holds the distinction of being part of two indie-rock giants—Pixies and The Breeders—counting among her fans the likes of Kurt Cobain and Olivia Rodrigo, two era-defining talents who invited her on tour three decades apart. But somehow, Deal had never set out to write a proper solo album outside of a 10-song 7-inch vinyl series in 2013. Hunkering down in the Florida Keys during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic ignited that initial spark, but the island naturally seeped into her creative psyche for years, having routinely retreated there with her parents before they were too old to travel. As a result, the intersection of memory and family comes across vividly throughout *Nobody Loves You More*. On “Summerland,” written as a loving tribute to the Keys, she reflects on their tradition with a soothing ukulele giving way to grand, whimsical orchestral swells worthy of Harry Nilsson. While on the tender title track, a vintage slow dance leads over majestic horns as she sings with open-hearted grace. It pairs elegantly with the gentle lullaby “Are You Mine?”, a touching ode to her mother, who battled dementia. These songs may sound like timeless tunes of the golden oldies era, but Deal also amps up the guitars, grounding them in reality with her usual humor and insouciance. “A Good Time Pushed,” the closest thing here to a Breeders ripper, suggests the end of a relationship before it’s even started: “We’re having a good time/I’ll see you around.” With songs dating back to the early 2000s, *Nobody Loves You More* varies stylistically, with Deal connecting to her own truth through personal loss, triumph, and failure. The fiercely paced “Disobedience” mirrors her enduring defiance, where she promises to stick around on her own terms: “I know what I want/Till I’m thrown off.”

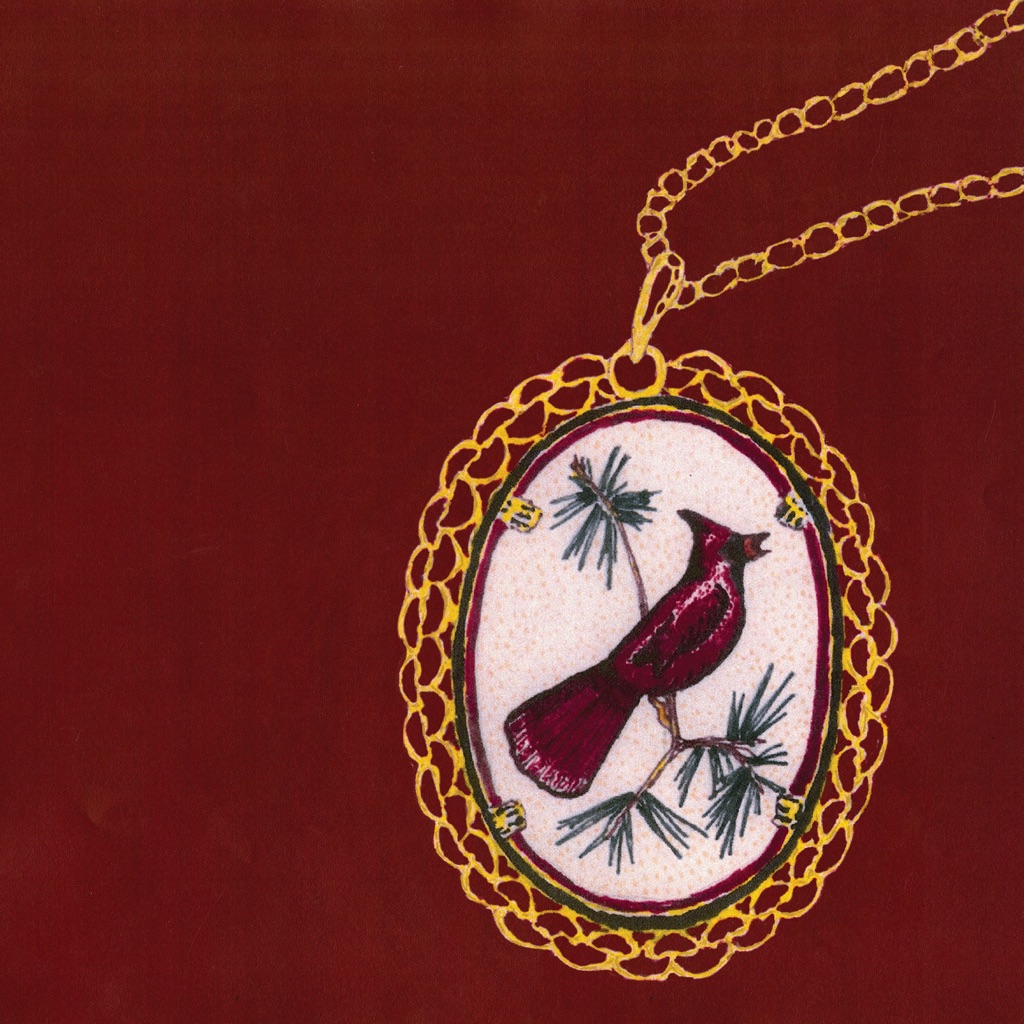

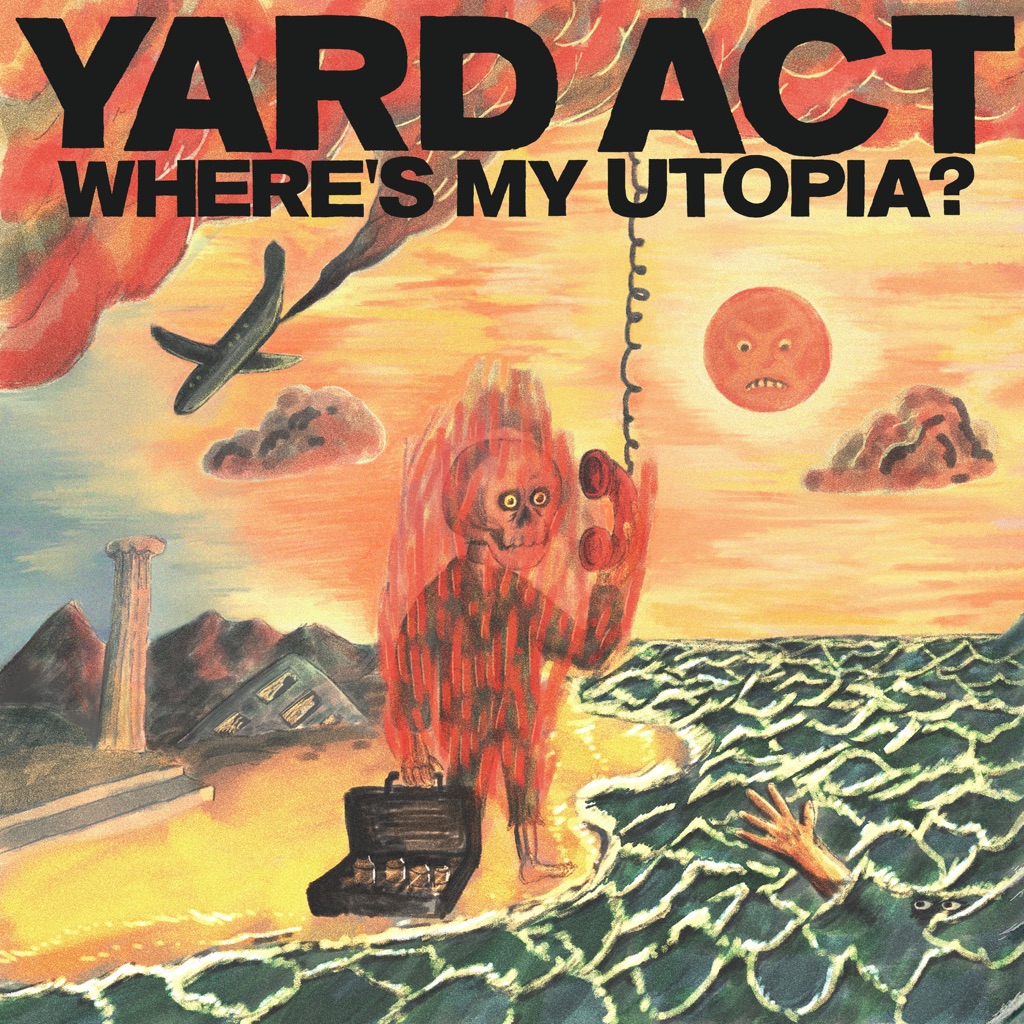

There was a point early in the creation of the swaggering second record by Yard Act when the Leeds quartet realized they were holding themselves back and needed to let go. “We were putting some drones and synths on the track ‘Fizzy Fish,’ which was the first one we wrote for the record, and someone raised the point that we weren’t going to be able to do it live,” vocalist James Smith tells Apple Music. “But we quickly agreed we’d worry about that later. Once we cut our losses with the idea of how we could do it, there was no real discussion on the areas the album went to.” That sense of daring is at the heart of *Where’s My Utopia?*. The four-piece has emerged with a kaleidoscopic pop record that dramatically builds upon the playful post-punk of their 2022 debut *The Overload*, its expansive sound taking in Gorillaz-meets-Ian Dury future funk, art-rock wigouts, orchestral epics, careening disco punk, and explosive indie sing-alongs. *The Overload* earned them a Mercury nomination and the chance to rerecord 2022 single “100% Endurance” with star fan Elton John, and its follow-up finds Smith searching for meaning in the wake of all his dreams coming true. “The record is about me realizing that the thing I’d wanted since being a teenager wasn’t going to magically solve all the problems that I live with,” Smith explains, “and the idea that everyone just has problems regardless of what position they’re in. I’m starting to wonder now if we just create them for ourselves because it shouldn’t be this hard.” It’s a narrative arc delivered with Smith’s trademark humor but always laced with poignancy, their anthemic hooks even sharper than those that fired their debut to success. *Where’s My Utopia?* is a bold, brilliant second album from one of the decade’s most imaginative bands. Smith guides us through it, track by track. **“An Illusion”** “This song definitely sets the score for ‘This isn’t a minimalist guitar post-punk album this time.’ The chorus lyric really sets up the whole premise of the situation I ended up in—that I’m in love with an illusion—and the idea that being in a successful band would solve my problems. Then, whilst my head was so buried in this world that I couldn’t get out of because of how much energy and time it was sucking out of me, all my other principles fell by the wayside. This song’s probably harder on myself than most are. The verses are about me being pissed, which I was for 18 months, and basically being just a bit useless, which I’ve got out of now. I stopped drinking off the back of the touring, I learned that I had to.” **“We Make Hits”** “This was one of the last songs written. We wrote it in Ryan \[Needham, bassist\]’s spare bedroom in a break from touring. I think Ryan had been going for that kind of French disco, Daft Punk, Justice vibes and everything fell out of me quite fast. I started by writing the story of me and Ryan and how we started the band. With this song, we were acknowledging that we’d always had ambition and we’d always wanted to do something bigger with music. Even though, at our core, all we wanted to do was make music, we always knew we would quite like to see what it was like on the other side and achieve something.” **“Down by the Stream”** “This was written in Turin. Everyone else had gone out for a meal and I decided to stay in the hotel room and wrote it using Jay \[Russell, drummer\]’s laptop. I’ve been looking back on my childhood a little bit more since my son was born and projecting him into scenarios I was in, even though historical truth and accuracy is a vague thing in terms of songwriting. It’s not literal, but it draws on my childhood. I was framing myself as this struggling person who was having a bit of a rough time, doing the woe-is-me thing about being in a successful band. I realized that if I was going to ask that empathy of the listener, then I should make sure that there was some corruption within me as well and highlight that I’m not some innocent person. It’s me dragging myself through the mud to let people know that I’m capable of being a dickhead just like everyone else.” **“The Undertow”** “‘Down by the Stream’ starts by the stream and then the stream leads to the sea, and that’s where the sharks start circling. We’ve ended up at sea on ‘The Undertow.’ The stream is the journey into adulthood and the sea is the murky open waters of adulthood and being out on your own in the big, bad world, then getting caught by the undertow of the industry. This is a thank-you note to my wife, really, who’s supported me through this entire caper that I’ve ended up on and been solid as a rock through it. There’s a part of me that’ll never be able to understand why I was selfish enough to do this for a living and leave my family behind to do it, so I’ll always live with that.” **“Dream Job”** “I caught myself writing the chorus in an interview when we were in Europe. Someone asked how it felt to have done a song with Elton John and have a Mercury nomination and all these things and I wasn’t really in the room and I just went, ‘Yeah, it’s ace, it’s wicked.’ I just started listing all these positive words without actually taking stock of what they were saying. It’s funny because I don’t really know how those things have affected me. I definitely wanted them and I’m glad I got them but they just happen and you move on. You get asked about them a lot, and the truth is that you don’t really think of them. I feel like the second you start wearing your achievements with pride, you’re dead in the water. I think the whole album is trying to strike that balance between being cynical and maybe a bit arsey, but also going, at the same time, ‘Things are great!’ It can be both, and it is both for us, and that’s life, even if it’s your life or my life in this band I’m in.” **“Fizzy Fish”** “The lyrics changed a lot on this one—I was literally writing about Fizzy Fish sweets for about three verses originally. With those seeds, you don’t really know where you’re going with them a lot of the time, but you let your mind chase after it and see where it goes. The Fizzy Fish, it was nostalgia, it was going back to the playground and that’s me having a conversation with another version of me from my childhood or a parallel universe. Again, it’s set in a lake, going with the water theme, because that’s a stagnant body of water that’s separate from the sea. It stands alone from the rest of the album. It’s set in my subconscious. ‘The Undertow’ through to ‘Grifter’s Grief’ is one narrative arc that follows me going into this successful Yard Act. ‘Fizzy Fish’ is me learning to cope with this newfound spotlight and who I am, whether I’ve changed from who I was, whether that’s positive or negative and the fact you have to create new masks to deal with a public-facing job because you don’t want to give too much of yourself away but, ultimately, to connect with people is the entire reason you’re making music.” **“Petroleum”** “This is based on an incident that happened at a gig at Bognor Regis at the start of 2023, the point within the story where I hit the bottom. I bottled the gig. Not anything drastic, we got through a set, but I was really disappointed in myself and my performance that night. I told the audience I was bored and I didn’t want to be there. We’d bitten off more than we could chew and I hadn’t had a break in 18 months, and I had a bad gig. This looks at the idea of what is expected of musicians when they perform live and this consumerist demand that they deliver. I realized that people don’t actually want honesty, they want the version of honesty they’ve paid to see. It’s learning to deal with these extra masks that we develop. I was trying to get to the core of ‘How can I channel a true version of how I’m feeling into an enjoyable performance that people deserve to see?’ This whole song reignited my passion for playing live and I’ve since learned how to process my emotions and funnel them into a performance that creates something that I’m proud of.” **“When the Laughter Stops” (feat. Katy J Pearson)** “It’s maybe a reaction to a lot of people saying, ‘Oh, Yard Act is the fun band, the jokers, and they don’t take it too seriously,’ and we don’t—because you can’t—but it’s that whole sad-clown complex. We’re not base level: We feel things just the same as everyone else! A lot of this album is rooted in that paranoia of not being able to maintain this—because it felt like I couldn’t do it if what it took to make a living from this job was those first 18 months over and over again. Fortunately, it’s changed, it’s fine but it has to stay at this level for it to be OK. If it drops back below, it’s hard work being in a band.” **“Grifter’s Grief”** “This is to do with the fact that my entire job now is based around sucking electricity out of giant venues and getting on aeroplanes and constantly burning up road miles and air miles and sea miles just to selfishly make a living whilst the planet burns. I spoke to my dad about it and he was kicking off about something and I was like, ‘Yeah but, Dad, I do that, I get on planes all the time.’ He went, ‘Yeah, but you need to do it to work.’ And I was like, ‘But I don’t. I could get a job that doesn’t involve that.’ It’s that everyone’s selfish inherently, I think.” **“Blackpool Illuminations”** “This is probably the most important song on the album. When we do the zany and comical stuff, we’re always trying to do it so you can pull the rug from under people with a song like this and prove what we’re capable of if we really put our minds to it. We supported Foals in Blackpool in May 2022. I had such nostalgic memories of Blackpool from going as a kid. My wife and son came and joined us for those two nights with Foals, and we had a couple of days and weekend in Blackpool because I wanted to show my baby where I had holidays as a child. Seeing him walking along the promenade, I saw myself in him and realized that he was just following the exact same footsteps that I did when I was a kid. \[The song\] follows my journey through childhood to that moment, really—these footprints of the past that we leave and then the future treads over them in a very similar way.” **“A Vineyard for the North”** “This is the note of hope that comes at the end. Climate change punctuates the album but I didn’t want to write too heavily about it. I read an article that French vineyard owners are starting to buy land in the south of England—because of the rising temperature, the south of England is now \[in\] prime condition for growing grapes for champagne. I was thinking how, as it gets hotter, it works its way up the country. It’s clutching at straws in a sense but it’s more to do with human nature and our ability to adapt and problem solve. I don’t think the answer is that everyone in the north starts buying vineyards and growing grapes. But, in essence, it is that things will change and we’ll have to adapt, and there’s hope and there are avenues we can always take.”