There’s a sick irony to how a country that extols rhetoric of individual freedom, in the same gasp, has no problem commodifying human life as if it were meat to feed the insatiable hunger of capitalism. If this is American nihilism taken to its absolute zenith, then God’s Country, the first full length record from Oklahoma City noise rock quartet Chat Pile is the aural embodiment of such a concept. Having lived alongside the heaps of toxic refuse that the band derives its name from, the fatalism of daily life in the American Midwest permeates throughout the works of Chat Pile, and especially so on its debut LP. Exasperated by the pandemic, the hopelessness of climate change, the cattle shoot of global capitalism, and fueled by “...lots and lots and lots and lots and lots and lots of THC,” God’s Country is as much of an acknowledgement of the Earth’s most assured demise as it is a snarling violent act of defiance against it. Within its over 40 minute runtime, God’s Country displays both Chat Pile’s most aggressively unhinged and contemplatively nuanced moments to date, drawing from its preceding two EPs and its score for the 2021 film, Tenkiller. In the band’s own words, the album is, at its heart, “Oklahoma’s specific brand of misery.” A misery intent on taking all down with it and its cacophonous chaos on its own terms as opposed to idly accepting its otherwise assured fall. This is what the end of the world sounds like.

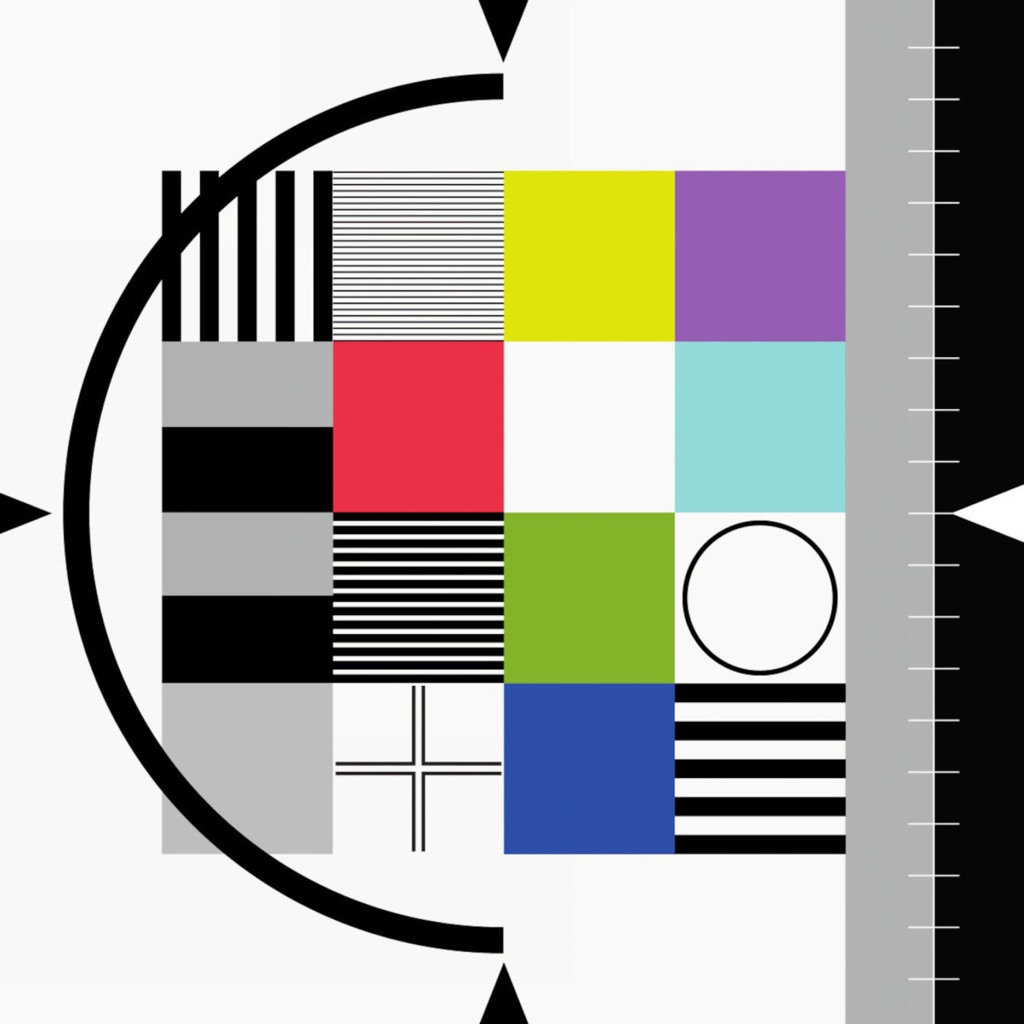

If The Smile ever seemed like a surprisingly upbeat name for a band containing two members of Radiohead (Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood, joined by Sons of Kemet drummer Tom Skinner), the trio used their debut gig to offer some clarification. Performing as part of Glastonbury Festival’s Live at Worthy Farm livestream in May 2021, Yorke announced, “We are called The Smile: not The Smile as in ‘Aaah!’—more the smile of the guy who lies to you every day.” To grasp the mood of their debut album, it’s instructive to go even deeper into a name that borrows the title of a 1970 Ted Hughes poem. In Hughes’ impressionist verse, some elemental force—compassion, humanity, love maybe—rises up to resist the deception and chicanery behind such disarming grins. And as much as the 13 songs on *A Light for Attracting Attention* sense crisis and dystopia looming, they also crackle with hope and insurrection. The pulsing electronics of opener “The Same” suggest the racing hearts and throbbing temples of our age of acute anxiety, and Yorke’s words feel like a call for unity and mobilization: “We don’t need to fight/Look towards the light/Grab it in with both hands/What you know is right.” Perennially contemplating the dynamics of power and thought, he surveys a world where “devastation has come” (“Speech Bubbles”) under the rule of “elected billionaires” (“The Opposite”), but it’s one where protest, however extreme, can still birth change (“The Smoke”). Amid scathing guitars and outbursts of free jazz, his invective zooms in on abuses of power (“You Will Never Work in Television Again”) before shaming inertia and blame-shifters on the scurrying beats and descending melodies of “A Hairdryer.” These aren’t exactly new themes for Yorke and it’s not a record that sits at an extreme outpost of Radiohead’s extended universe. Emboldened by Skinner’s fluid, intrepid rhythms, *A Light for Attracting Attention* draws frequently on various periods of Yorke and Greenwood’s past work. The emotional eloquence of Greenwood’s soundtrack projects resurfaces on “Speech Bubbles” and “Pana-Vision,” while Yorke’s fascination with digital reveries continues to be explored on “Open the Floodgates” and “The Same.” Elegantly cloaked in strings, “Free in the Knowledge” is a beautiful acoustic-guitar ballad in the lineage of Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees” and the original live version of “True Love Waits.” Of course, lesser-trodden ground is visited, too: most intriguingly, math-rock (“Thin Thing”) and folk songs fit for a ’70s sci-fi drama (“Waving a White Flag”). The album closes with “Skrting on the Surface,” a song first aired at a 2009 show Yorke played with Atoms for Peace. With Greenwood’s guitar arpeggios and Yorke’s aching falsetto, it calls back even further to *The Bends*’ finale, “Street Spirit (Fade Out).” However, its message about the fragility of existence—“When we realize we have only to die, then we’re out of here/We’re just skirting on the surface”—remains sharply resonant.

The Smile will release their highly anticipated debut album A Light For Attracting Attention on 13 May, 2022 on XL Recordings. The 13- track album was produced and mixed by Nigel Godrich and mastered by Bob Ludwig. Tracks feature strings by the London Contemporary Orchestra and a full brass section of contempoarary UK jazz players including Byron Wallen, Theon and Nathaniel Cross, Chelsea Carmichael, Robert Stillman and Jason Yarde. The band, comprising Radiohead’s Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood and Sons of Kemet’s Tom Skinner, have previously released the singles You Will Never Work in Television Again, The Smoke, and Skrting On The Surface to critical acclaim.

Like AC/DC before them, Beach House’s gift lies in managing to make what feels like the same album a hundred different ways. Even the new inflections on *Once Twice Melody*—the string section of “ESP,” the rhythmic nods to hip-hop (“Pink Funeral”) and Italo-disco (“Runaway”)—fit immediately into their plush, neon-lit world. And while specific moments conjure specific eras (“Superstar” the triumph of an ’80s John Hughes movie, “Once Twice Melody” a swirl of ’60s surrealism), the cumulative effect is something like a fairytale rendered in sound: majestic, inviting, but dark enough around the edges to keep you off-balance. And just like that (snap), they do it again.

Once Twice Melody is the 8th studio album by Beach House. It is a double album, featuring 18 songs presented in 4 chapters. Across these songs, many types of style and song structures can be heard. Songs without drums, songs centered around acoustic guitar, mostly electronic songs with no guitar, wandering and repetitive melodies, songs built around the string sections. In addition to new sounds, many of the drum machines, organs, keyboards and tones that listeners may associate with previous Beach House records remain present throughout many of the compositions. Beach House is Victoria Legrand, lead singer and multi-instrumentalist, and Alex Scally, guitarist and multi-instrumentalist. They write all of their songs together. Once Twice Melody is the first album produced entirely by the band. The live drums are by James Barone (same as their 2018 album, 7), and were recorded at Pachyderm studio in Minnesota and United Studio in Los Angeles. For the first time, a live string ensemble was used. Strings were arranged by David Campbell. The writing and recording of Once Twice Melody began in 2018 and was completed in July of 2021. Most of the songs were created during this time, though a few date back over the previous 10 years. Most of the recording was done at Apple Orchard Studio in Baltimore. Once Twice Melody was mixed largely by Alan Moulder but a few tracks were also mixed by Caesar Edmunds, Trevor Spencer, and Dave Fridmann.

“With my return to Warrington and Runcorn”, says Gordon Chapman-Fox, “The music began to reflect the social isolation of New Towns life. This was mirrored by its creation through two years of pandemic lockdown. “The music is perhaps the loneliest and most spacious I have created so far - the Open Spaces in the album title taking on multiple interpretations. The focus and feel of the album is not inspired by the architecture of new towns, but the lives lived in them. I think the precise planning new towns and creating specific zones for different activities - working, shopping and living - created an artificial way of life. One that failed to understand the sheer messiness of human existence. “Musically the canvas is more epic before. The first side comprising two epic tracks, and the second side introducing Euclidean sequencing to create disorientating, evolving melodies.” Chapman-Fox continues to find the wonder in his exploration of new towns and their impact on the lives and minds who worked and lived there. His Warrington-Runcorn New Town Development Plan output to date has reached far and wide and garnered incredible responses from fans and critics across the world. Resonating with new town locals, architects, designers and anyone who appreciates beautifully constructed, evocative electronic compositions. He continues to work on further Warrington-Runcorn material while touring Districts, Roads, Open Spaces throughout the UK for the rest of 2022 and into the new year.

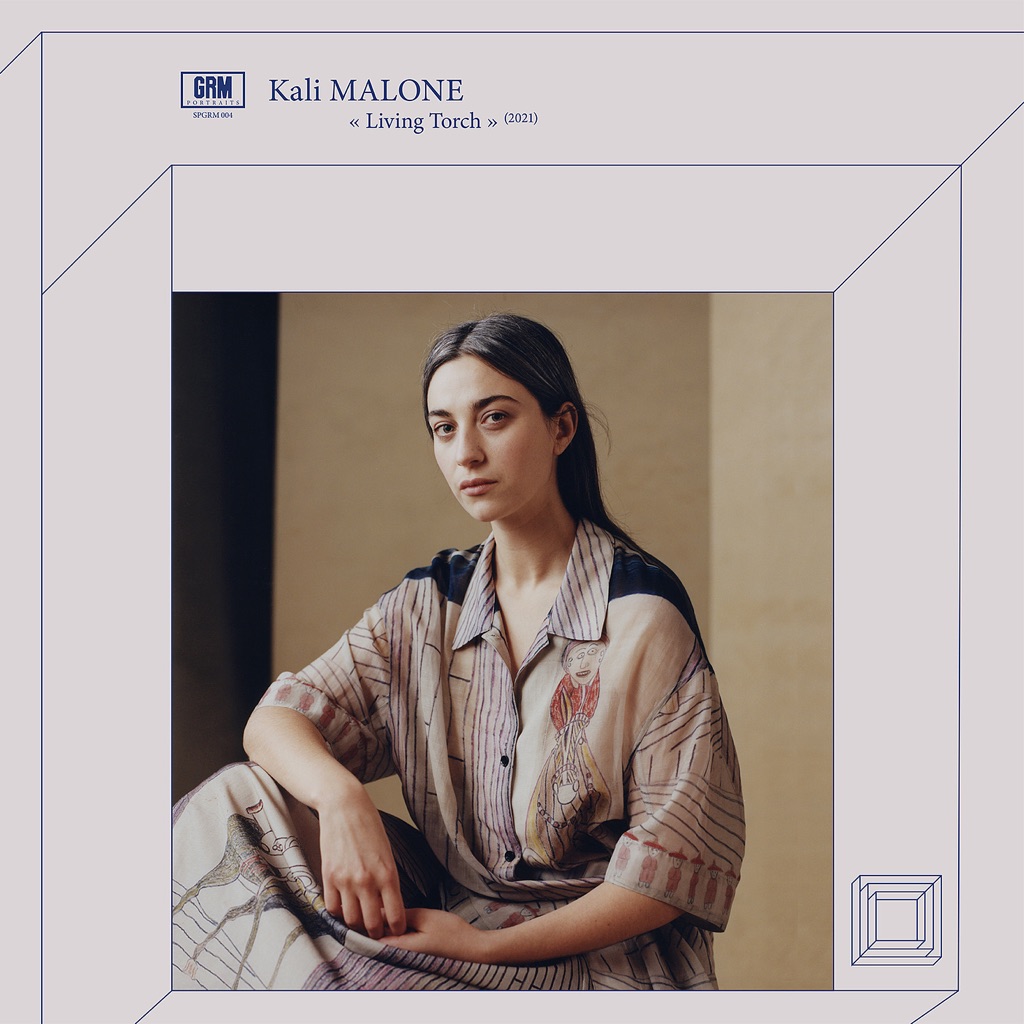

Stockholm-based Kali Malone is best-known for music that combines the rigor of electro-acoustic composition with the ruminative atmosphere of drone, doom metal, and medieval music—associations, no doubt, reinforced by her work with the pipe organ, which tends to put people in more primitive states of mind. As with a lot of her work (not to mention that of minimalist forebears like Eliane Radigue and La Monte Young), the process behind *Living Torch* is complex—pre-modern intonation, contemporary adaptations of Indian drone boxes. But the result is naturalistic and easy to listen to, conjuring dark hills, smoke-filled voids, and a pervasive sense of gloom that, while not threatening, point to forces and feelings modern life doesn’t tend to make time for. Listen loud and/or alone.

Living Torch, through its unique structural form and harmonic material, is a bold continuation of Kali Malone’s demanding and exciting body of work, while opening new perspectives and increasing the emotional potential of the music tenfold. As such, Living Torch is a major new piece by the composer and adds a significant milestone to an already fascinating repertoire. Departing from the pipe organ that Malone’s music is most notable for, Living Torch features a complex electroacoustic ensemble. Leafing through recordings from conventional instruments like the trombone and bass clarinet to more experimental machines like the boîte à bourdon, passing through sinewave generators and Éliane Radigue’s ARP 2500 synthesizer. Living Torch weaves its own history, its own genealogy, and that of its author. It extends her robust structural approach to a liberated palette of timbre. Living Torch was initially commissioned by GRM for its legendary loudspeaker orchestra, the Acousmonium, and premiered in its complete multichannel form at the Grand Auditorium of Radio France in a concert entirely dedicated to the artist. Composed at GRM studios in Paris between 2020-2021, Living Torch is a work of great intensity, an oeuvre-monde that is singularly placed at the crossroads of instrumental writing and electroacoustic composition. Living Torch proceeds from multiple lineages, including early modern music, American minimalism, and musique concrète. It’s a work as much turned towards exploring justly tuned harmony and canonic structures as towards the polyphony of unique timbres, the scaling of dynamic range, and the revelation of sound qualities. GRM (Groupe de Recherches Musicales), the pioneering institution of electroacoustic, acousmatic, and musique concrète, has been a unique laboratory for sonorous research since 1958. Witnessing the extreme vitality of the music championed by GRM, the Portraits GRM record series extends and expands this momentum with Kali Malone’s Living Torch. The French label-partner Shelter Press is proud to continue the collaboration with GRM, which Peter Rehberg of Editions MEGO set the foundation for in 2012.

When COVID-19 lockdowns prohibited Welsh Dadaist Cate Le Bon to fly back to the United States from Iceland, she found herself returning to her homeland to create a sixth studio album, *Pompeii*, a collection of avant-garde art pop far removed from the 2000s jangly guitar indie she once hung her hat on. In Cardiff, recording in a house “on a street full of seagulls,” as she tells Apple Music, “I instinctively knew where all the light switches were and I knew all these sounds that the house makes when it breathes in the night.” Created with co-producer Samur Khouja, the album obscures linear nostalgia to confront uncertainty and modern reality, with stacked horns, saxophones, and synths. “For a while I was flitting between despair and optimism,” she says. “I realized that those are two things that don\'t really have or prompt action. So I tried to lean into hope and curiosity instead of that. Then I kept thinking about the idea that we are all forever connected to everything. That’s probably the theme that ties together the record.” Below, Cate Le Bon breaks down *Pompeii*, track by track. **“Dirt on the Bed”** “This song is very set in the house. It\'s being haunted by yourself in a way—this idea of time travel and storing things inside of you that maybe don\'t serve you but you still have these memories inside of you that you\'re unconscious of. It was the first song that we started working on when Samur arrived in Wales. It’s pretty linear, but it blossoms in a way that becomes more frantic, which was in tune with the lockdown in a literal and metaphorical sense.” **“Moderation”** “I was reading an essay by an architect called Lina Bo Bardi. She wrote an essay in 1958 called ‘The Moon’ and it\'s about the demise of mankind, this chasm that\'s opened up between technical and scientific progress and the human capacity to think. All these incremental decisions that man has made that have led to climate disaster and people trying to get to the moon, but completely disregarding that we\'ve got a housing crisis, and all these things that don\'t really make sense. We\'ve lost the ability to account for what matters, and it will ultimately be the demise of man. We know all this, and yet we still crave the things that are feeding into this.” **“French Boys”** “This song definitely started on the bass guitar, of wanting this late-night, smoky, neon escapism. It’s a song about lusting after something that turns into a cliché. It’s this idea of trying to search for something to identify yourself \[with\] and becoming encumbered with something. I really love the saxophone on this one in the instrumental. It is a really beautiful moment between the guitars and the saxophones.” **“Pompeii”** “This is about putting your pain somewhere else, finding a vessel for your pain, removing yourself from the horrors of something, and using it more as a vessel for your own purposes. It’s about sending your pain to Pompeii and putting your pain in a stone.” **“Harbour”** “I made a demo with \[Warpaint’s\] Stella Mozgawa, who plays drums on the record. We spent a month together at her place in Joshua Tree, just jamming out some demos I had, and this was one of them that became a lot more realized. The effortless groove that woman puts behind everything, it\'s just insane to me. She was encouraging me to put down a bassline. That playfulness of the bass is probably a direct product of her infectiousness, but the song is really about \'What do you do in your final moment? What is your final gesture? Where do you run when you know there\'s no point running?\'” **“Running Away”** “‘Running Away’ was another song that I worked on with Stella in Joshua Tree. It\'s about disaffection, I suppose, and trying to figure out whether it\'s a product of aging, where you know how to stop yourself from getting hurt by switching something off, and whether that\'s a useful tool or not. It’s an exploration of knowing where the pitfalls of hurt are, because you have a bit more experience. Is it a useful thing to avoid them or not?” **“Cry Me Old Trouble”** “Searching for your touch songs of faith, when you tap into this idea that you\'re forever connected to anything, there\'s a danger—the guilt that is imposed on people through religion, this idea of being born a sinner. Of separating those two things of feeling like you are forever connected to everything without that self-sacrifice or martyrdom. It’s about being connected to old trouble and leaning into that, and this connection to everything that has come before us. We are all just inheriting the trouble from generations before.” **“Remembering Me”** “It’s really about haunting yourself. When the future\'s dark and you don\'t really know what\'s going to happen, people start thinking about their legacy and their identity, and all those things that become very challenged when everything is taken away from you and all the familiar things that make you feel like yourself are completely removed. \[During the pandemic\] a lot of people had the internet to express themselves and forge an identity, to make them feel validated.” **“Wheel”** “In one sense, it is very much about the time trials of loving someone, and how that can feel like the same loop over and over, but I think the language is a little bit different. It\'s a little more direct than the rest of the record. I was struggling to call people over the pandemic. What do you say? So, I would write to people in a diary, not with any idea that I would send it to them, but just to try and keep this sense of contact in my head. A lot of this was pulled from letters that I would write my friend. Instead of \'Dear Diary\' it was \'Dear Bradford,\' just because I missed him, but couldn\'t pick up the phone.”

Pompeii, Cate Le Bon’s sixth full-length studio album and the follow up to 2019’s Mercury-nominated Reward, bears a storied title summoning apocalypse, but the metaphor eclipses any “dissection of immediacy,” says Le Bon. Not to downplay her nod to disorientation induced by double catastrophe — global pandemic plus climate emergency’s colliding eco-traumas resonate all too eerily. “What would be your last gesture?” she asks. But just as Vesuvius remains active, Pompeii reaches past the current crises to tap into what Le Bon calls “an economy of time warp” where life roils, bubbles, wrinkles, melts, hardens, and reconfigures unpredictably, like lava—or sound, rather. Like she says in the opener, “Dirt on the Bed,” Sound doesn’t go away / In habitual silence / It reinvents the surface / Of everything you touch. Pompeii is sonically minimal in parts, and its lyrics jog between self-reflection and direct address. Vulnerability, although “obscured,” challenges Le Bon’s tendencies towards irony. Written primarily on bass and composed entirely alone in an “uninterrupted vacuum,” Le Bon plays every instrument (except drums and saxophones) and recorded the album largely by herself with long-term collaborator and co-producer Samur Khouja in Cardiff, Wales. Enforced time and space pushed boundaries, leading to an even more extreme version of Le Bon's studio process – as exits were sealed, she granted herself “permission to annihilate identity.” “Assumptions were destroyed, and nothing was rejected” as her punk assessments of existence emerged. Enter Le Bon’s signature aesthetic paradox: songs built for Now miraculously germinate from her interests in antiquity, philosophy, architecture, and divinity’s modalities. Unhinged opulence rests in sonic deconstruction that finds coherence in pop structures, and her narrativity favors slippage away from meaning. In “Remembering Me,” she sings: In the classical rewrite / I wore the heat like / A hundred birthday cakes / Under one sun. Reconstituted meltdowns, eloquently expressed. This mirrors what she says about the creative process: “as a changeable element, it’s sometimes the only point of control… a circuit breaker.” She’s for sure enlightened, or at least more highly evolved than the rest of us. Hear the last stanza on the album closer, “Wheel”: I do not think that you love yourself / I’d take you back to school / And teach you right / How to want a life / But, it takes more time than you’d tender. Reprimanding herself or a loved one, no matter: it’s an end note about learning how to love, which takes a lifetime and is more urgent than ever. To leverage visionary control, Le Bon invented twisted types of discipline into her absurdist decision making. Primary goals in this project were to mimic the “religious” sensibility in one of Tim Presley’s paintings, which hung on the studio wall as a meditative image and was reproduced as a portrait of Le Bon for Pompeii’s cover. Fist across the heart, stalwart and saintly: how to make “music that sounds like a painting?” Cate asked herself. Enter piles of Pompeii’s signature synths made on favourites such as the Yamaha DX7, amongst others; basslines inspired by 1980s Japanese city pop, designed to bring joyfulness and abandonment; vocal arrangements that add memorable depth to the melodic fabric of each song; long-term collaborator Stella Mozgawa’s “jazz-thinking” percussion patched in from quarantined Australia; and Khouja’s encouraging presence. The songs of Pompeii feel suspended in time, both of the moment and instant but reactionary and Dada-esque in their insistence to be playful, satirical, and surreal. From the spirited, strutting bass fretwork of “Moderation”, to the sax-swagger of “Running Away”; a tale exquisite in nature but ultimately doomed (The fountain that empties the world / Too beautiful to hold), escapism lives as a foil to the outside world. Pompeii’s audacious tribute to memory, compassion, and mortal salience is here to stay.

‘Paste’ is the new album by Moin, due for release on the 28th October 2022 via AD 93. The follow up to their well received debut album ‘Moot!’, the record draws influences from alternative guitar music in its many forms, using electronic manipulations and sampling techniques to redefine it's context, not settling on any one style but moving through them in search of new connections. By exploring these relationships, Moin delivers another collage of the known and unknown, punctuated by words that are just out of reach. Mastered and cut by Noel Summerville Artwork by Joe Andrews and Tom Halstead Mixed at Hackney Road Studios

Black Thought may be best-known as part of The Roots, performing night after late night for Jimmy Fallon’s TV audience, yet the Philadelphia native concurrently boasts a staggering reputation as a stand-alone rapper. Though he’s earned GOAT nods from listeners for earth-shaking features alongside Big Pun, Eminem, and Rapsody, his solo catalog long remained relatively modest in size. Meanwhile, Danger Mouse had a short yet monumental run in the 2000s that made him one of that decade’s most beloved and respected producers. His discography from that period contains no shortage of microphone dynamos, most notably MF DOOM (as DANGERDOOM) and Goodie Mob’s CeeLo Green (as Gnarls Barkley). Uniting these low-key hip-hop powerhouses is the stuff of hip-hop dreams, the kind of fantasy-league-style draft you’d encounter on rap message boards. Yet *Cheat Codes* is real—perhaps realer than real. Danger Mouse’s penchant for quirkily cinematic, subtly soulful soundscapes remains from the old days, but the growth from his 2010s work with the likes of composer Daniele Luppi gives “Aquamarine” and “Sometimes” undeniable big-screen energy. Black Thought luxuriates over these luxurious beats, his lyrical lexicon put to excellent use over the feverish funk of “No Gold Teeth” and the rollicking blues of “Close to Famous.” As if their team-up wasn’t enough, an intergenerational cabal of rapper guests bless the proceedings. From living legend Raekwon to A$AP Rocky to Conway the Machine, New York artists play a pivotal role here. A lost DOOM verse, apparently from *The Mouse and the Mask* sessions, makes its way onto the sauntering and sunny “Belize,” another gift for the fans.

Long before he made his name at jazz’s vanguard, editing together off-the-cuff live sessions like a hip-hop beatmaker, drummer, and producer, Makaya McCraven set out to create a comprehensive record of his collaborative process—a testament to the intuition of improvisation. Its sessions recorded over the course of seven years, between multiple projects and releases, *In These Times* is McCraven’s sixth album as a bandleader, and it showcases the virtuosic instrumentalists he has spent his career building an almost telepathic bond with—bassist Junius Paul and guitarist Jeff Parker among them. It’s also the warmest and most enveloping album he’s produced to date. Frenetic beat-splicing might underpin the polyrhythms of tracks such as “Seventh String” and “This Place That Place,” but the soft melodies played by Parker and harpist Brandee Younger always permeate—a reminder of the clarity of the moment of creation, rather than its post-production manipulation. Indeed, *In These Times* is a reflection of the past decade of McCraven’s instrumental expertise, but it’s also a powerful reminder of the freedom inherent in this time, in the here and now of making music together, when the artist lets go and surrounds us with the ineffable beauty of collective creation.

In These Times is the new album by Chicago-based percussionist, composer, producer, and pillar of our label family, Makaya McCraven. Although this album is “new," the truth it’s something that's been in process for a very long time, since shortly after he released his International Anthem debut In The Moment in 2015. Dedicated followers may note he’s had 6 other releases in the meantime (including 2018’s widely-popular Universal Beings and 2020’s We’re New Again, his rework of Gil Scott-Heron’s final album for XL Recordings); but none of which have been as definitive an expression of his artistic ethos as In These Times. This is the album McCraven’s been trying to make since he started making records. And his patience, ambition, and persistence have yielded an appropriately career-defining body of work. As epic and expansive as it is impressively potent and concise, the 11 song suite was created over 7+ years, as McCraven strived to design a highly personal but broadly communicable fusion of odd-meter original compositions from his working songbook with orchestral, large ensemble arrangements and the edit-heavy “organic beat music” that he’s honed over a growing body of production-craft. With contributions from over a dozen musicians and creative partners from his tight-knit circle of collaborators – including Jeff Parker, Junius Paul, Brandee Younger, Joel Ross, and Marquis Hill – the music was recorded in 5 different studios and 4 live performance spaces while McCraven engaged in extensive post-production work from home. The pure fact that he was able to so eloquently condense and articulate the immense human scale of the work into 41 fleeting minutes of emotive and engaging sound is a monumental achievement. It’s an evolution and a milestone for McCraven, the producer; but moreover it’s the strongest and clearest statement we’ve yet to hear from McCraven, the composer. In These Times is an almost unfathomable new peak for an already-soaring innovator who has been called "one of the best arguments for jazz's vitality" by The New York Times, as well as recently, and perhaps more aptly, a "cultural synthesizer." While challenging and pushing himself into uncharted territories, McCraven quintessentially expresses his unique gifts for collapsing space and transcending borders – blending past, present, and future into elegant, poly-textural arrangements of jazz-rooted, post-genre 21st century folk music.

For two decades, multi-instrumentalist Daniel Rossen has been known for his inventive, genre-meddling psychedelic folk and chamber pop as a key member in the era-defining Brooklyn indie-rock band Grizzly Bear as well as the duo Department of Eagles. Recorded at his new home in Santa Fe, his debut full-length album under his own name—following 2018’s Record Store Day-exclusive single “Deerslayer” and the EP *Silent Hour / Golden Mile* in 2012—is a majestic and masterful collection of songs that no doubt highlight his specific strengths: mournful fingerpicking, textural production, stacked horns and harmonies that play out like memories and an uncertain future, simultaneously. His specificity is clearest in an orchestral track like “Unpeopled Space,” where technical instrumentation distracts from Rossen’s vibrating tenor, his soft lyrics about nothingness.

Pop in your earpiece, close your eyes and embrace the wonders (and horrors) of augmented reality and prepare to travel 500 years into the future as Richard Dawson returns with…The Ruby Cord. These seven tracks plunge us into an unreal, fantastical and at times sinister future where social mores have mutated, ethical and physical boundaries have evaporated; a place where you no longer need to engage with anyone but yourself and your own imagination. It’s a leap into a future that is well within reach, in some cases already here.

Touch Sensitive Records proudly presents the Cork-based musician Elaine Howley’s debut solo album 'The Distance Between Heart and Mouth'. The product of an audio diary kept on a 4 track cassette machine throughout 2019 and 2020, the album recreates the intimacy of a radio show filled with Howley’s favourite sounds, pallets, and textures; effortlessly joining the dots between pop and experimentation, summoning the kaleidoscopic world of Trish Keenan & Broadcast, the bruised lo-fi soul of Tirzah and the dubbed-out blues of Leslie Winer. Over nine patient, spontaneous self-recorded and produced tracks, Elaine Howley traces the outline of a small space that could be considered one of the longest journeys to be taken - 'The Distance Between Heart And Mouth'. As a member of Crevice, Howlbux and, perhaps most notably, psychedelic rock group The Altered Hours, Elaine Howley is renowned as a singular voice in the Irish underground. 'The Distance Between Heart and Mouth' is her most personal statement to date. “I was thinking a lot about the themes of silencing and communication,” she explains. “My voice and a lot of my feelings were buried and I wanted to push that out using music. That is the intention of this album - trying to be brave enough to share and to open up; along with the internal and external barriers that exist when it comes to doing that." 'The Distance Between Heart and Mouth' is the product of an audio diary kept on a 4 track cassette machine throughout 2019 and 2020. Pulling on formative teenage musical influences alongside memories of a childhood spent home-recording Longwave 252 transmissions, Howley recreates the intimacy of a radio show filled with her favourite sounds, pallets, and textures; effortlessly joining the dots between pop and experimentation. "I brought all those early influences along with me. It was a private time to enjoy music - listening to my Walkman or making mixtapes. I hear the roots of the sounds I am drawn to beginning then. I found myself returning to, and recreating something of that time, for this record." The daily sit-down at her tape machine became an almost ritualistic experience over this period as Howley both experimented in sound and worked through her own vulnerabilities. “I wasn't burdening anyone or adding pressure to myself. I've always found music cathartic but this felt like a deeper level for me”. This release can be tangibly felt in lead single ‘Silent Talk’. “That track is about the urge to run and not share parts of myself but also about continuing to try to do that and about the patience people can show in waiting for me.” On second track ‘Autumn Speak’, we fully step into the album’s journey through the transition of Howley’s favourite season. “I was thinking about how resistance to decay through self preservation disrupts the process but cannot stop it and only serves to distort and delay. It’s a celebration of endings and allowing change to occur.” Such internal conflicts and strivings are captured sonically throughout the album as echoes and delays whirl into an endless expanse and samples run backwards and onwards. Themes regarding memory are also written throughout, particularly in ‘Song For Mary Black’, previously issued on Touch Sensitive’s ‘Wacker That’ compilation. “Mary Black was the first concert I saw and it had a huge impression on me. Growing up, I was a fan of the ‘A Woman’s Heart’ compilation of amazing Irish female voices. It made music feel closer to me than it had previously; it was local and it felt tangible. It reminded me of my Mam and Aunts.” Alongside those early inspiring voices and the defining sounds of her teenage years, we can hear the dubbed-out blues of Leslie Winer, the kaleidoscopic world of Trish Keenan & Broadcast, and the bruised lo-fi soul of Tirzah. Over nine tracks, Elaine Howley traces the outline of a small space that can be considered one of the longest journeys to be taken - 'The Distance Between Heart And Mouth'.

Moundabout – Flowers Rot, Bring Me Stones Some of the most striking ancient structures in Ireland are not its standing stones but the country’s neolithic “passage tombs” constructed between five and six thousand years ago. As this modern name suggests, they were in all likelihood actual liminal zones bridging this world and the next; charnel houses, stone age reliquaries, bone gardens, cairns vibrating between planes and states of being. One of the most interesting of these graves is Knowth at Brú na Bóinne. Its huge, many-passaged central burial chamber is surrounded by 17 small barrows, and among these constructions is over one third of all the rediscovered megalithic art in Western Europe. Kerbstones and pillars are carved with a hypnotising array of spiral, serpentiform and lozenge-shaped patterns; alongside is chiselled the oldest known representation of the moon made by man. Moundabout is a new folk project based in Ireland by Paddy Shine of Gnod and Phil Masterson of Los Langeros/Damp Howl/Bisect, but the words ‘new’ and ‘folk’ need to be treated with care here. Listening to Flowers Rot, Bring Me Stones is like entering a trance state while staring at one of the Knowth spiral carvings. Like following a ridged epidermal loop inwards, tracing the spiral of an ammonite towards the centre or peeling back the layers of an onion, immersion in this great album sees you travelling both temporally backwards and spatially inwards simultaneously. The listener is invited to see folk – orally transmitted music often concerning national identity and culture played on traditional instruments – as a glowing helix of a continuum stretching way back beyond the revival of the 1950s and 1960s to an eternal vibrancy that predates classical antiquity and Irish civilisation itself. As the album moves the listener, they are taken on a geographical and geological journey as well as psychological and spiritual, traveling inwards from the coast (‘The Sea’), as well as down beneath the strata (“How many bog bodies are waiting to be found?”) And when you have been primed, it takes you all the way back to commune with older gods on the album’s epic centrepiece, ‘Dick Dalys Dance’, creating the kind of prehistoric drones and trance-inducing rhythms that the echoing, celestially aligned corridors of the Brú na Bóinne were built to amplify. This is not new music but the deep sensations it provokes will be new to most listeners. Imagine for a few minutes something as glorious as a Nurse With Wound List for the 21st Century… were I given such a formidable task as to organise such a collection of mind-bending music, Flowers Rot, Bring Me Stones by Moundabout would be one of the first records I would include. John Doran, Wiltshire, 2021 ---

From his formative days associating with Raider Klan through his revealing solo projects *TA13OO* and *ZUU*, Denzel Curry has never been shy about speaking his mind. For *Melt My Eyez See Your Future*, the Florida native tackles some of the toughest topics of his MC career, sharing his existential notes on being Black and male in these volatile times. The album opens on a bold note with “Melt Session #1,” a vulnerable and emotional cut given further weight by jazz giant Robert Glasper’s plaintive piano. That hefty tone leads into a series of deeply personal and mindfully radical songs that explore modern crises and mental health with both thematic gravity and lyrical dexterity, including “Worst Comes to Worst” and the trap subversion “X-Wing.” Systemic violence leaves him reeling and righteous on “John Wayne,” while “The Smell of Death” skillfully mixes metaphors over a phenomenally fat funk groove. He draws overt and subtle parallels to jazz’s sociopolitical history, imagining himself in Freddie Hubbard’s hard-bop era on “Mental” and tapping into boom bap’s affinity for the genre on “The Ills.” Guests like T-Pain, Rico Nasty, and 6LACK help to fill out his vision, yielding some of the album’s highest highs.

Melt My Eyez See Your Future arrives as Denzel Curry’s most mature and ambitious album to date. Recorded over the course of the pandemic, Denzel shows his growth as both an artist and person. Born from a wealth of influences, the tracks highlight his versatility and broad tastes, taking in everything from drum’n’bass to trap. To support this vision and show the breadth of his artistry, Denzel has enlisted a wide range of collaborators and firmly plants his flag in the ground as one of the most groundbreaking rappers in the game.

“The de-evolution of man.” That’s how Viagra Boys frontman Sebastian Murphy sums up the theme of the band’s third album. “My inspirations were how divided everyone is, people’s ideas of why things are happening, and just general craziness—especially reactions to the pandemic,” he tells Apple Music. “I was also very inspired by a few documentaries about monkeys.” As always, the American-born vocalist of the Swedish punk group puts a witty and humorous spin on the subject matter, but its roots come from the genuine despair he feels viewing his home country from abroad. “I definitely use the States as a reference point because it’s a real melting pot of insanity, in my opinion,” he says. “I mean, those types of people definitely exist here in Sweden, but they’re not storming the Capitol or anything.” Below, he discusses each track. **“Baby Criminal”** “My girlfriend said, ‘I used to be a baby, now I’m just a criminal.’ She said she had that feeling once, and I could really relate to that. There’s been times in my life where I’ve excused everything I do because I was just a kid. And then it just got to this point where I’m dealing drugs and getting into trouble. I’m just a criminal. But I took a more playful twist on it—I made up a character named Jimmy, who’s this guy sitting in his basement making a nuclear reactor. That’s inspired by a true story. I think there was a kid in the States who did that when he was 14 or something.” **“Cave Hole”** “This is a freestanding interlude made by a guy called DJ Hayden. He works with our producer, and he was working side by side with us while we were recording some of these songs. He makes super-cool electronic music, and I just wanted to have a few weird interludes between the songs. I actually wanted to call the album *Cave Hole*. I like it because it reminds you of a K-hole, so I’m glad I got to fit it into the tracklist.” **“Troglodyte”** “If one of these school shooters or mass shooters were to live back in the days when we were apes, and they had these ideas of doing a mass murder or some shit like that, they wouldn’t have a chance because the other apes would just maul the shit out of them. It’s basically a mixture of me saying that we would have been better off as monkeys, and at the same time, it’s a fuck-you to a lot of these angry idiots with extreme right-wing ideas.” **“Punk Rock Loser”** “I’m painting a picture of this guy who’s a real asshole, but at the same time, I’ve been that asshole as well. It’s a song I could’ve written a couple of albums ago because I was that person. Sometimes I definitely feel like I’m a punk-rock loser. It’s like a flashback to my life five years ago. I’m making fun of it, and I’m also kind of romanticizing it in a way, like when you’re walking down the street and you feel like you’re the king of the world. I love that feeling, but it’s not often I get to feel that way.” **“Creepy Crawlers”** “This is very inspired by this dude I saw get interviewed by Channel 5 News. He started ranting about the vaccine causing kids to grow tails and animal hair. I’m like, ‘How do you know if the hair is human or animal?’ But I have a love for extreme absurdities, like stuff you would read in the *Weekly World News*—stories about two-headed babies or the idea of Hillary Clinton using adrenochrome to stay young, or the idea that the global elite are these reptiles plotting against us. So, this is me putting myself in the shoes of a conspiracy theorist.” **“The Cognitive Trade-Off Hypothesis”** “This is based on a documentary about chimpanzees that has the same title. It’s about this trade-off that happened millions of years ago, when we were all still chimpanzees and lived up in the trees. We could count at incredible speeds to assess a threat really easily, like a pack of predators coming in. When the chimpanzees moved from the trees down to the savanna, they suddenly developed a need to communicate with each other about these threats, like, ‘There’s a lion over there—maybe don’t go there.’ So, they developed the ability to speak, and the theory is that we traded our ability to count things really fast—really good short-term memories—for long-term memories. And my idea is, that’s what fucked us. Long-term memories gave us the ability to plan murder and shit like that. Monkeys don’t think about that. They live in the now.” **“Globe Earth”** “That’s another DJ Hayden thing, and the name is obviously from flat-earthers. When they try to diss us globe-earthers, that’s what they call us. Like, ‘You fucking globe-earther.’ I love it.” **“Ain’t No Thief”** “This is about being accused of something that I obviously did, but being a bit delusional about it, which I have been in many periods of my life. Especially when I was a speed freak, I would get accused of something and I would just be like, ‘How the fuck could you think that about me?’ Like this feeling of being betrayed because someone thinks that you’re a certain way, when in fact you are that way. It’s supposed to be a bit funny.” **“Big Boy”** “We were pretty drunk in the studio at, like, 3 am, and we had this idea of sounding like a ’70s rock band recording a blues song. So, we all got in there and we’re playing our instruments and it sounded like shit. But at the same time, it was cool. We ended up adding a hip-hop beat, and I made up lyrics on the spot that were the stupidest thing I could think of—feeling like a big boy. It goes back to that feeling you had when you were a kid, but you’re an adult. Like, ‘I’m a big boy. I’ve got an apartment with a big TV’—as if that makes you a grown person. It doesn’t. You can still be very childish and pay your rent.” **“ADD”** “I wanted to write a song about ADD because it’s been a part of my life since I was a teenager. I’ve just always had this inability to concentrate, and I forget things all the time. I’ll leave the house without my keys or put something down and forget it right away. Or someone sends me an important email and I’m like, ‘Oh, yeah, I’m going to answer this.’ And then I never do. It’s about this inability to do menial tasks—that’s what defines ADD for me. I just can’t motivate myself to do the easiest thing in the world.” **“Human Error”** “This is another DJ Hayden instrumental.” **“Return to Monke”** “I saw a meme that was just a picture of a monkey, and it said, ‘Return to Monke,’ spelled like that. I love meme culture, and especially that meme. So simple and yet so strong. When I wrote the song, I imagined us playing live and I pictured people in the crowd completely losing it and turning into monkeys—flying all over the place, throwing shit, taking off their clothes. It was inspired by Rage Against the Machine as well. I wanted to create a song that people could sing along to, like chanting in a cult. That phrase ‘leave society, be a monkey’ is just taking the piss out of these people who think the world is a big conspiracy against them. Maybe they should just leave.”

For fans of ’90s indie rock—your Sonic Youths, your Breeders, your Yo La Tengos—*Versions of Modern Performance* will serve as cosmic validation: Even the kids know the old ways are best. But who influenced you is never as important as what you took from them, a lesson that Chicago’s Horsegirl understands intuitively. Instead, the art is in putting it together: the haze of shoegaze and the deadpan of post-punk (“Option 8,” “Billy”), slacker confidence and twee butterflies (“Beautiful Song,” “World of Pots and Pans”). Their arty interludes they present not as free-jazz improvisers, but a teenage garage band in love with the way their amps hum (“Bog Bog 1,” “Electrolocation 2”).

Horsegirl are best friends. You don’t have to talk to the trio for more than five minutes to feel the warmth and strength of their bond, which crackles through every second of their debut full-length, Versions of Modern Performance. Penelope Lowenstein (guitar, vocals), Nora Cheng (guitar, vocals), and Gigi Reece (drums) do everything collectively, from songwriting to trading vocal duties and swapping instruments to sound and visual art design. “We made [this album] knowing so fully what we were trying to do,” the band says. “We would never pursue something if one person wasn’t feeling good about it. But also, if someone thought something was good, chances are we all thought it was good. ”Versions of Modern Performance was recorded with John Agnello (Kurt Vile, The Breeders, Dinosaur Jr.) at Electrical Audio. “It’s our debut bare-bones album in a Chicago institution with a producer who we feel like really respected what we were trying to do,” the band says. Horsegirl expertly play with texture, shape, and shade across the record, showcasing their fondness for improvisation and experimentation. Opener “Anti-glory” is elastic and bright post-punk, while the guitars in instrumental interlude “Bog Bog 1” smear across the song’s canvas like watercolors. “Dirtbag Transformation (Still Dirty)” and “World of Pots and Pans” have rough, blown-out pop charm. “The Fall of Horsegirl” is all sharp edges and dark corners.

Welsh producer/vocalist Kelly Lee Owens released her ultra-personal second album, *Inner Song*, in August 2020, in the thick of the pandemic. With any plans to tour the record scuttled, that winter she managed to decamp from her London home to Oslo—just before borders were closing again—for some uninterrupted studio time. Much like *Inner Song*’s rather short 35-day gestation, after a month of work with Norwegian avant-garde/noise producer Lasse Marhaug, Owens emerged with *LP.8*, her most experimental, liberating record yet. On her previous full-lengths—this is actually her third, not her eighth—Owens alternated between deep, plodding techno tracks and moody synth compositions, over which her lithe vocals floated effortlessly. But on *LP.8*, the contrasts—between the earthly and the ethereal—are felt more deeply. The opener, “Release,” plays like a lost Chris & Cosey cut, its crunchy precision finding that sweet spot between industrial and early techno. On the New Age-y “Anadlu,” “S.O (2),”and “Olga,” hints of Enya’s influence shine through, but the songs’ gauzy atmospheres are often counterweighted by brooding undertones. “Nana Piano” is a melancholy solo piano sketch, unfettered except for some gentle birdsong in the background. But the closing “Sonic 8” is Owens at her most direct and visceral: She channels all sorts of frustrations while intoning, “This is a wake-up call/This is an emergency” over a beat so skeletal and abrasive that it sounds like a frayed wire swinging dangerously close to the bathtub.

Born out of a series of studio sessions, LP.8 was created with no preconceptions or expectations: an unbridled exploration into the creative subconscious. After releasing her sophomore album Inner Song in the midst of the pandemic, Kelly Lee Owens was faced with the sudden realisation that her world tour could no longer go ahead. Keen to make use of this untapped creative energy, she made the spontaneous decision to go to Oslo instead. There was no overarching plan, it was simply a change of scenery and a chance for some undisturbed studio time. It just so happened that her flight from London was the last before borders were closed once again. The blank page project was underway. Arriving to snowglobe conditions and sub-zero temperatures, she began spending time in the studio with esteemed avant-noise artist Lasse Marhaug. Together, they envisioned making music somewhere in between Throbbing Gristle and Enya, artists who have had an enduring impact on Kelly’s creative being. In doing so, they paired tough, industrial sounds with ethereal Celtic mysticism, creating music that ebbs and flows between tension and release. One month later, Kelly called her label to tell them she had created something of an outlier, her ‘eighth album’. Lasse Marhaug is known for hundreds of avant-noise releases, previously working with the likes of Merzbow, Sunn O))) and Jenny Hval, for whom he produced her acclaimed albums Apocalypse, Girl, Blood Bitch and The Practice Of Love. A label mate of Kelly’s, Marhaug has recorded for Smalltown Supersound since 1997. Welsh electronic artist Kelly Lee Owens released her eponymous debut album in 2017 and followed this up with 2020’s Inner Song. She has collaborated with Björk, St. Vincent and John Cale. In April, she returns with LP.8.

Panda Bear’s music has always felt connected to the innocence and melancholy of ’60s pop, but *Reset* is the first time he’s made the connection so explicit. Built on simple loops of often familiar songs (The Drifters’ “Save the Last Dance for Me,” The Everly Brothers’ “Love of My Life”), the music here is both an homage to a bygone style and a rendering of how that style could play out in a modern context—in other words, time travel. Together with Sonic Boom—formerly of Spacemen 3 and himself an expert interpreter of ’60s pop and psychedelia—he gives you his handclaps (“Everyday”) and heartaches (“Danger”) and windswept *sha-la*s (“Edge of the Edge”). But they also summon the fatalism that made artists like The Shangri-Las so bewitching (“Go On”) and the space-age wonder that characterized producers like Joe Meek and the early electronic musician Raymond Scott (“Everything’s Been Leading to This”). And like the supposedly basic teenage sounds it came from, *Reset*’s smile conceals a yearning and complexity that runs deep.

Tresor (Treasure) is Gwenno Saunders’ third full length solo album and the second almost entirely in Cornish (Kernewek). Written in St. Ives, Cornwall, just prior to the Covid lockdowns of 2020 and completed in Cardiff during the pandemic along with her producer and musical collaborator, Rhys Edwards, Tresor reveals an introspective focus on home and self, a prescient work echoing the isolation and retreat that has been a central, global shared experience over the past two years. The wider project also includes a companion film, written and directed by Gwenno in collaboration with Anglesey based filmmaker and photographer Clare Marie Bailey. Tresor diverges from the stark themes of technological alienation in Y Dydd Olaf (The Final Day) and the meditations on the idea of the homeland on the slyly infectious Le Kov (The Place of Memory). Accessible and international in outlook, peppered with moments of offbeat humor, Le Kov presented Cornish to the world. It highlighted the struggle of Kernewek and the concerns of Cornish cultural visibility as the perceptions of a timeless and haunted landscape often clash with the reality of intense poverty and an economy devastated by the demands of tourism. The impact of Le Kov was resounding, providing for the Cornish language an unprecedented international platform, that saw Gwenno touring and headlining in Europe and Australia, and supporting acts such as Suede and the Manic Street Preachers. Her performance of ‘Tir ha Mor’ on Later with Jools Holland was a triumph, and the album prompted wider conversations on the state of the Cornish language with Michael Portillo, Jon Snow, and Nina Nannar. After Le Kov, interest in learning Cornish hit an all-time high, and the cultural role of the language was firmly in the spotlight. Cornish is now enjoying increased visibility in some commercial contexts, yet Cornish is importantly also a language which is spoken in families and communities. This context is the starting point for Tresor and it’s where this dreamy album finds its bite. Gwenno occupies a singular position, raised speaking Cornish alongside Welsh in the home with her family as a living mother tongue. Cornish is not only a cultural legacy or a politicized project; it is the language in which one thinks and dreams, a language of loving and longing. To be able to share in this private world is the gift of Tresor. On Tresor, Gwenno shifts focus from the external to the internal, exposing the walls of gems hidden within the caves. Inspired by powerful woman writers and artists such as Ithell Colquhoun, the Cornish language poet Phoebe Proctor, Maya Deren and Monica Sjöö, Tresor is an intimate view of the feminine interior experience, of domesticity and desire, a rare glimmer of life lived in and expressed through Cornish. Don’t ever be fooled by Gwenno’s pop sensibility and her ability to create plush and immersive moods. Gwenno always has something to say, often signposting powerful commentary with discordant notes and sonic friction. Tresor is no different: like a soothing mermaid’s call it lures the listener into strange and beautiful depths. Although Tresor evokes the waters that shape the Cornish experience, it is musically far reaching with influences spanning from Eden Ahbez to Aphex Twin. More overtly psychedelically tinged than her previous work, Tresor embeds found sounds ranging from Venice to Vienna, layering cultural and historical atmospheres, decoupling the use of Cornish from any geographic determinism. The personal and political are fully entwined in Tresor with stories showing the complex tension of both integration and resistance, of feeling decentered yet also fully belonging to several places at once. Languages are symbolically contradictory: they are indelibly embedded in place, yet they travel with bodies and in dreams, taking up root wherever they are planted or abandoned out of necessity. They signal identities and histories, yet are also indifferent tools of communication and commerce belonging to everyone and to no one. How do both speakers and non-speakers navigate these legacies? In Tresor Gwenno explores the perspective that living through Kernewek allows for an expression of imaginative spaces that are truly free. As such, Tresor also recalls the waters of the unconscious, the undulating elemental tides suggesting emotion, intuition, those features long associated with the archetypal anima. In “Anima” Gwenno asks how do we fully inhabit different parts of the self, acknowledging convergent cultural and personal histories, embracing the shadow. She explores how the power of the feminine voice inspired by the Cornish landscape asserts itself, presenting a richly melodic counterpoint to a place and people known for rugged survival and jagged edges. The title track “Tresor” (Treasure) confronts the contradictions that come with visibility as a woman and the challenges of wielding women’s power. “Tonnow” shows the watery depths of woman’s desire and knowing, an invitation to liberation. The Welsh language track, “NYCAW” (Nid yw Cymru ar Werth - Wales is not for Sale) widens the frame outward from the personal to the collective, condemning the urgent crisis caused by second home ownership in Wales, denouncing the neoliberal marketing of place that is shattering communities and exploiting cultures. Tresor the film, is inspired by surrealist filmmakers such as Sergei Parajanov, Agnes Varda, and Alejandro Jodorowsky, and reflects Gwenno’s growing interest in film and the intersection of music with visual components. Filmed in Wales and Cornwall, Tresor evokes a dreamworld from another time, surreal, and sensual, saturated with light and colour. Although Tresor is a project birthed from introspection and intimacy, the implications of the messages are much broader. Ultimately Gwenno is asking what are other ways of understanding and being in relation to one another? What are the spaces where we can best see each other and ourselves in our most raw and authentic state? Can we find balance individually and as a species, and can we sit with the discomfort that comes with growth? What are our roles in both shaping and being shaped by the cultures we move in, in a world that is ever changing, and where we all have a place? Tresor does not provide easy answers, for Gwenno shows us that we exist in paradox, our threads of place and story entwined like knotwork, our many selves shining as beautiful entanglements.

Listening to the Baltimore instrumental band Horse Lords’ mix of minimal art-rock and pan-African music is like looking at one of those optical illusions where you can’t tell if an image is static or moving, and if so, how fast. It can sound jarring and dissonant and almost purposefully ugly (“May Brigade”) but so trancelike in its repetitions that even its dissonances become beautiful (“Law of Movement”). And like Talking Heads or ’90s math-rock bands like Don Caballero, their kinship with punk isn’t just their intensity but their rebellion against the fantasy of rock music being something loose and free. They occasionally flirt with machines (the outro of “Mess Mend”), but their discipline is 100 percent human.

Horse Lords return with Comradely Objects, an alloy of erudite influences and approaches given frenetic gravity in pursuit of a united musical and political vision. The band’s fifth album doesn’t document a new utopia, so much as limn a thrilling portrait of revolution underway. Comradely Objects adheres to the essential instrumental sound documented on the previous four albums and four mixtapes by the quartet of Andrew Bernstein (saxophone, percussion, electronics), Max Eilbacher (bass, electronics), Owen Gardner (guitar, electronics), and Sam Haberman (drums). But the album refocuses that sound, pulling the disparate strands of the band’s restless musical purview tightly around propulsive, rhythmic grids. Comradely Objects ripples, drones, chugs, and soars with a new abandon and steely control.

Like so much art created in the depths of isolation in the pre-vaccine pandemic era, The Mountain Goats’ 20th studio album fantasizes about escapism. In between writing best-selling novels, John Darnielle passed his time at home in North Carolina watching vintage thrillers, which inspired a songwriting jag that reminded him of his early days cranking out stream-of-consciousness home recordings. “I immediately started going, ‘Oh, he\'s getting ready for a big fight,’ and I get very excited about that,” Darnielle tells Apple Music. “I just kept taking notes on what the governing plots and tropes and styles are. I got really interested in that, about the weight of those things. This was very much going back into the strike-while-the-iron\'s-hot mindset, which produces different sorts of songs.” These familiar—even comforting, despite their brutal context—tropes of vengeance and hopelessness provided a unifying theme for the songs, recorded in January 2021 and produced by Bully’s Alicia Bognanno. While The Mountain Goats’ two prior LPs, *Getting Into Knives* and *Dark in Here*—both recorded just under the wire before lockdown in March 2020, in Memphis and Muscle Shoals, respectively—were steeped in the classic blues and soul of their birthplaces, *Bleed Out* is loud and brash in ways that fit the songs’ desperate characters and wanton violence, as well as their creators’ own pent-up aggression. “I’m always leery of the word ‘catharsis,’” Darnielle says. “I think it\'s more of a grail—because you can\'t have it, it starts to seem really appealing. And the bloodshed, that\'s kind of universal in Mountain Goats. Just something I like.” Here Darnielle unpacks the album, scene by gory scene. **“Training Montage”** “The Van Damme movies, all the kung fu movies have a training montage, most of the Rocky movies have a training montage. It\'s a myth about subjecting yourself to a period of austerity and discipline for some reawakening. I think it predates the action movie, this idea that you\'re going to retreat for a winter of hard times and emerge in spring as a beautiful, powerful flower, a season in isolation to refocus oneself on some goal—maybe a noble goal, maybe not. And also, to start it with just acoustic guitar and voice, it sounds like a very early Mountain Goats record until the drum hits.” **“Mark on You”** “‘Mark on You’ is a specific story about somebody who\'s going after someone. Either this or \'Training Montage\' was probably the first song I wrote for this, and I was like, \'Oh man, this feels like a vein.\' Revenge is something you can ardently want and you never have to be satisfied by what you get because you\'re not going to get it.” **“Wage Wars Get Rich Die Handsome”** “When you are writing about a desire to make everybody pay for something that\'s causing you pain, you\'re writing about something universal anyway. But especially if everybody\'s under a lot of pressure, then everybody\'s feeling that. The band was super into that one.” **“Extraction Point”** “To me, in some ways it\'s a tribute to a band called Silkworm. Their songs are all very cinematic. They\'re often voiced by a narrator, but who seems to be situated within a specific context. That\'s basically what I have always done, but mine usually exists more in a folk context, whereas this is much more of a rock song. What I really like about it is there\'s something that just finished happening and you have to put together the details of what it was. And it looks like it was pretty gnarly, but the song is pretty, it\'s triumphant. I wasn\'t sitting there trying to write a Silkworm pastiche, but I do think it comes out showing some clear signs of its pedigree. Silkworm is one of the best bands who ever existed.” **“Bones Don’t Rust”** “‘Bones Don\'t Rust\' is sort of a pretty classic spy/action-movie story. And that one, speaking of influences, I feel it\'s a Stan Ridgway sort of tune in a lot of ways. He\'s another guy who does a narrator who\'s telling you a story from inside his world and you have to put the world and the story together from the clues he\'s dropping. He also plays a lot with genre, especially with spaghetti western stuff and noir tropes; I think this one has a little of both of those. The speaker is somebody who\'s been in the business of maybe being an assassin, maybe just a guy who breaks people\'s knees. The guy who comes in and does the dirty work and is now a little on the older side but knows he will be doing this until he drops.” **“First Blood”** “I watched *First Blood Part II* in Portland, Oregon, in the \'80s. And to tell you the god\'s honest truth, I bought a tab of acid off somebody and ate it and went in the movie theater, but it turned out to be bunk. I just sat there waiting for it to come on and nothing happened. This song is extremely meta about the nature of action movies. And especially with action movies in the \'70s, there\'s so many of these—*Walking Tall* and *Death Wish*—like, \'Well, sometimes you got to take the law in your own hands.\' John Rambo, if a guy is going over to Vietnam to be a one-man army freeing a bunch of brothers, that\'s not how it\'s going to work out. They\'re bloody-minded fantasies. It makes the point that this sort of thinking is latent for a lot of people and eventually, those people get jobs on benches in courtrooms and stuff.” **“Make You Suffer”** “I’m fond of ‘Make You Suffer’ because it\'s sort of pretty. There\'s a lot of songs whose message is the message of \'Make You Suffer,\' but \'Make You Suffer\' just goes ahead and says it outright. It\'s got a lovely little midtempo shuffle to it, it\'s got a nice melodic hook, and I think it\'s one of the meaner songs I\'ve ever written. You know how the Zodiac Killer sent these greeting cards to the cops and you\'d open it up and it would be this really threatening thing about how many schoolchildren he was going to shoot on a bus? There\'s something of a Mountain Goats song in there, like: \'Oh, this looks like a friendly thing, until I open it.\'” **“Guys on Every Corner”** “That is a stakeout song that comes from a lot of these action movies, especially Italian ones, but also plenty of American ones—mafia or various mafia-adjacent things. I like the element of sort of a private militia that is lurking everywhere.” **“Hostages”** “That\'s my other favorite one after \'Extraction Point.\' I like the ones that explore something and stick with the mood for a long time and see where it goes. Both are kind of like Grateful Dead jams—they\'re extensive. And I have to say, I think that\'s one of my best choruses ever. Because it leans in—if you\'re going to have a hostage drama, it should be extreme. I once heard it in some action movie or another where a guy says, \'Only an idiot takes hostages,\' because there\'s no good way out of a hostage situation. It\'s one of the more explicitly cinematic songs that\'s not actually taken from a particular movie.” **“Need More Bandages”** “That\'s one of the weirdest songs I\'ve written since the tape days, in terms of the music. The chord progression is a little more angular than I usually go. I\'m so tethered to melodic development chord progressions, and this has a lot of half steps in it and stuff that I find pretty interesting, and rhythmically it\'s like that, too. It\'s kind of got sort of a post-punk feel to it that I like.” **“Incandescent Ruins”** “This one\'s kind of cheating, because it\'s more of a science-fiction film than an action film. It\'s not from any particular movie, but it sounds sort of like a *Westworld* sort of theme, some sort of post-robot-overlord future in which there are mazes to escape from and stuff. The one style of songwriting I do pretty good is to sketch this entire imaginary world just through its details. It\'s one of my sort of really obscure skill sets.” **“Bleed Out”** “I wrote it on Sunday morning. I remember I was deep in the writing zone at that point, and what that means for my family is that dad is going to check out sometimes and then you don\'t really actually have a dad in the house for the next three to five hours. I wrote all these verses and was sending them one at a time to Peter \[Hughes, bassist\] going, \'Well, you got to hear what I got working here. This is pretty fun.\' At that point we\'d been together for a solid week, and that\'s a part of the studio experience that is hard to explain to the outside world. There\'s always a great deal of emotion, because you\'ve been doing this thing where you\'re sharing some part of your creativity with these people every single day, but it\'s a profound communal sharing. Once we landed on that groove, we played it for a good half an hour, 40 minutes before we started recording. It\'s like *Get Lonely*—the band name and the title make sense. The Mountain Goats bleed out.”

Subtlety is not The Chats’ strong point. Exhibit A is the blunt-as-it-comes title of the Queensland trio’s second album, a 13-song record in which only two of its tracks surpass the three-minute mark. Add the fact that bassist-vocalist Eamon Sandwith sings like a chainsaw, snarling and raging over a series of tightly coiled riffs that rarely dip under hyper-speed, and you have the sonic equivalent of a swift boot to the face. Recorded in six days, the album finds Sandwith’s everyman lyrical focus taking in subjects such as the cost of cigarettes (“The Price of Smokes”), hoon driving culture (“6L GTR”), and being busted for buying an under-14s train ticket (“Ticket Inspector”), all with a turn of phrase that’s unquestionably Australian. (“Starin’ at the ATM/It says insufficient funds/That’s just not good enough/’Cause right now I wanna get drunk,” he growls in “Paid Late”.) More sober themes occasionally pop their heads over the bar (“Emperor of the Beach” lambastes surfers who view the beach as their own), but even they’re delivered as delicately as a headbutt. And if you don’t like it? Well…you know what you can do.

When Animal Collective emerged from the fringes of New York’s underground in the early 2000s, it was hard to imagine they’d become what they did—a big-tent psychedelic band that could handle festival stages while still pushing the avant-garde; an art project that skirts the mainstream while still making music more visionary and unusual than most of their indie peers. Whereas 2016’s *Painting With* explored the manic side of their sound, *Time Skiffs* is, by and large, chill—a lazy river of sound that mixes the primitive and the New Age-y (“Cherokee”), the funky and the ethereal (“Prester John”). And while there’s always a tinge of uncertainty—the Cheshire Cats to their sweet-natured Alice—the music always resolves gently toward the light. If they’re not our Grateful Dead, nobody is.

Time Skiffs’ nine songs are love letters, distress signals, en plein air observations, and relaxation hymns, the collected transmissions of four people who have grown into relationships and parenthood and adult worry. But they are rendered with Animal Collective’s singular sense of exploratory wonder. Harmonies so rich you want to skydive through their shared air, textures so fascinating you want to decode their sorcery, rhythms so intricate you want to untangle their sources. Here is Animal Collective's past two decades, still in search of what’s next.

London duo Jockstrap first gained attention in 2018 with an almost unthinkable fusion of orchestral ’60s pop and avant-club music. On their debut album, conservatory grads Georgia Ellery and Taylor Skye continue to push against convention while expanding the outline of their sui generis sound. Skye’s electronic production is less audacious this time out; *I Love You Jennifer B* is more of a head listen than a body trip. There are a few notable exceptions: The opener, “Neon,” explodes acoustic strumming into industrial-strength orchestral prog; “Concrete Over Water” violently crossfades between a pensive melody reminiscent of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” and zigzagging synths recalling Hudson Mohawke’s trap-rave. But most of the album trains its focus on guitars, strings, and Ellery’s crystalline coo, leaving all the more opportunities to marvel at her unusual lyricism. Her writing returns again and again to questions of desire and regret, and while it can frequently be cryptic, she’s not immune to wide-screen sincerity: In “Greatest Hits,” when she sings, “I believe in dreams,” you believe her—never mind that she’s soon free-associating images of Madonna and Marie Antoinette. And on “Debra,” when she sings, “Grief is just love with nowhere to go” over a cascading beat that sounds like Kate Bush beamed back from the 22nd century, all of Jockstrap’s occasional impishness is rendered moot. At just 24 years old, these two are making some of the most grown-up pop music around.

When Georgia Ellery and Taylor Skye make music as Jockstrap, the process and result has one definition: pure modern pop alchemy. Meeting in 2016 when they shared the same com- position class while studying at London’s Guildhall School of Music & Drama, Ellery and Skye founded Jockstrap as a creative outlet for their rapidly-developing tastes. While Ellery had moved from Cornwall to the English capital to study jazz violin, Skye arrived from Leicester to study music production. Both were delving deep into the varied worlds of mainstream pop, EDM and post-dubstep (made by the likes of James Blake and Skrillex), as well as classical composition, ‘50s jazz and ‘60s folk singer-songwriters. The influence of the club and a dancier focus, which was hinted at on previous releases, now scorches through their new material like wildfire. Take the thumping, distorted breakbeats of ‘50/50’ –inspired by the murky quality of YouTube mp3 rips –as well as the sparkling synth eruptions of ‘Concrete Over Water’, as early evidence of where Jockstrap are heading next. Jockstrap’s discography is restless and inventive, traversing everything from liberating dancefloor techno to off-kilter electro pop, trip-hop and confessional song writing; an omnivorous sonic palette that takes on a cohesive maturity far beyond their ages of only 24 years old. They have cemented themselves as one of the most vital young groups to emerge from London’s melting pot of musical cultures.

Oh Sees albums often sound like lost classics from remote corners of underground rock—music as much about unearthing music as making it. Billed by singer/guitarist John Dwyer as “brain-stem-cracking scum-punk recorded tersely in the basement,” *A Foul Form* is as simple and exhilarating as its makers promise. But it’s also a reminder of how good rudimentary music can feel in the hands of a skilled band. These are songs called things like “Fucking Kill Me,” “Funeral Solution,” and “Social Butt”—and they sound like it. But they’re as catchy as Dwyer’s takes on psychedelic pop and as tightly played as his prog-metal ones, not to mention handy with fake British accents.

Building on the promise of nearly 10 years testing limits within club music, Batu presents his debut album Opal. Experimentation is a well-established facet of Omar McCutcheon’s identity within the leftfield techno zeitgeist, but more than ever on Opal he seizes the opportunity to incorporate ideas beyond dancefloor impetus into his animated, forward-leaning sound. Through the course of 11 tracks, rhythmic forms are mutated and manipulated, sonic matter bends across the frequency range and narrative structures coalesce and dissolve according to Batu’s own internal logic. Unpredictability lies at the heart of all this music, bound together by a consistent modernist glint. It’s a sound intrinsically connected to the superlative string of club 12”s, EPs and collaborations Batu has spun behind him thus far, even as it moves into unfamiliar terrain, guided by abstract inspiration from coastal landscapes and the mineral matter all life on Earth is built on. On Opal the visceral production isn’t necessarily geared towards shock tactics. Instead, emotional depths are explored through melodic and textural forms which take on an elemental quality. It’s a space which can accommodate the explicit heart and soul of the human voice, as recent collaborator serpentwithfeet demonstrates weaving a mesmerising vocal through ‘Solace’, but it can also take in broad sweeps of interpretive landscape. There’s also room for small fragments of instrumentation, recorded by Memotone, processed by Batu and subtly threaded throughout the album. Balancing micro and macro in specific sounds as much as moods, Batu’s finely-sculpted work calls to mind the immensity of passing time cast in cliff faces, and the intimate personal growth we experience in our own lifetimes. Mimicking the iridescent stone it takes its name from, Opal refracts Batu’s distinctive artistic imprint, giving us a deeper, more revealing impression of the artist as he explores ideas bigger – and indeed smaller.

Brittney Parks’ *Athena* was one of the more interesting albums of 2019. *Natural Brown Prom Queen* is better. Not only does Parks—aka the LA-based singer, songwriter, and violinist Sudan Archives—sound more idiosyncratic, but she’s able to wield her idiosyncrasies with more power and purpose. It’s catchy but not exactly pop (“Home Maker”), embodied but not exactly R&B (“Ciara”), weird without ever being confrontational (“It’s Already Done”), and it rides the line between live sound and electronic manipulation like it didn’t exist. She wants to practice self-care (“Selfish Soul”), but she also just wants to “have my titties out” (“NBPQ \[Topless\]”), and over the course of 55 minutes, she makes you wonder if those aren’t at least sometimes the same thing. And the album’s sheer variety isn’t so much an expression of what Parks wants to try as the multitudes she already contains.

Goat’s music captures the great horror movie turn of the innocent protagonist realizing the groovy party they’ve stumbled into is actually a pretense for ritual sacrifice. Mixing global funk and dance music with the seductive dread of psychedelic rock, *Oh Death* should be comfort food for anyone into the worlds of reissue labels and rare groove, but it also sharpens the teeth on an aesthetic that, in modern contexts, is often presented as bohemian background music—stuff that sounds cool but not much else. So, enjoy the Moroccan vibes of “Blow the Horns” or the collective liberation of “Under No Nation,” but make no mistake: these guys are waiting for you in your nightmares (“Soon You Die”).

Part of the appeal of Alex G’s homespun folk pop is how unsettling it is. For every Beatles-y melody (“Mission”) or warm, reassuring chorus (“Early Morning Waiting”) there’s the image of a cocked gun (“Runner”) or a mangled voice lurking in the mix like the monster in a fairy-tale forest (“S.D.O.S”). His characters describe adult perspectives with the terror and wonder of children (“No Bitterness,” “Blessing”), and several tracks make awestruck references to God. With every album, he draws closer to the conventions of American indie rock without touching them. And by the time you realize he isn’t just another guy in his bedroom with an acoustic guitar, it’s too late.