A general observation: You don’t go see Rick Rubin at Shangri-La if you’re just going to fuck around. For their sixth LP, The Strokes turn to the Mage of Malibu to produce their most focused collection of songs since 2003’s *Room on Fire*—the very beginning of a period marked by discord, disinterest, and addiction. Only their fourth record since, *The New Abnormal* finds the fivesome sounding fully engaged and totally revitalized, offering glimpses of themselves as we first came to know them at the turn of the millennium—young saviors of rock, if not its last true stars—while also providing the sort of perspective and even grace that comes with age. “Bad Decisions” is at turns riffy and elegiac, Julian Casablancas’ corkscrewing chorus melody a close enough relative to 1981’s “Dancing With Myself” that Billy Idol and Tony James are credited as songwriters. Though not as immediate, “Not the Same Anymore” is equally toothsome, a heart-stopping soul number that manages to capture feelings of both triumph and deep regret, with Casablancas opening himself up and delivering what might be his finest vocal performance to date. “I was afraid,” he sings, amid a weave of cresting guitars. “I fucked up/I couldn’t change/It’s too late.” For a band that forged an entire mythology around appearing as though they couldn’t be bothered, this is an exciting development. It’s cool to care, too.

Adrianne Lenker had an entire year of touring planned with her indie-folk band Big Thief before the pandemic hit. Once the tour got canceled, Lenker decided to go to Western Massachusetts to stay closer to her sister. After ideas began to take shape, she decided to rent a one-room cabin in the Massachusetts mountains to write in isolation over the course of one month. “The project came about in a really casual way,” Lenker tells Apple Music. “I later asked my friend Phil \[Weinrobe, engineer\] if he felt like getting out of the city to archive some stuff with me. I wasn\'t thinking that I wanted to make an album and share it with the world. It was more like, I just have these songs I want to try and record. My acoustic guitar sounds so warm and rich in the space, and I would just love to try and make something.” Having gone through an intense breakup, Lenker began to let her emotions flow through the therapy of writing. Her fourth solo LP, simply titled *songs* (released alongside a two-track companion piece called *instrumentals*), is modest in its choice of words, as this deeply intimate set highlights her distinct fingerpicking style over raw, soul-searching expressions and poignant storytelling motifs. “I can only write from the depths of my own experiences,” she says. “I put it all aside because the stuff that became super meaningful and present for me was starting to surface, and unexpectedly.” Let Lenker guide you through her cleansing journey, track by track. **two reverse** “I never would have imagined it being the first track, but then as I listened, I realized it’s got so much momentum and it also foreshadows the entire album. It\'s one of the more abstract ones on the record that I\'m just discovering the meaning of it as time goes on, because it is a little bit more cryptic. It\'s got my grandmother in there, asking the grandmother spirit to tell stories and being interested in the wisdom that\'s passed down. It\'s also about finding a path to home and whatever that means, and also feeling trapped in the jail of the body or of the mind. It\'s a multilayered one for me.” **ingydar** “I was imagining everything being swallowed by the mouth of time, and just the cyclical-ness of everything feeding off of everything else. It’s like the simple example of a body decomposing and going into the dirt, and then the worm eating the dirt, and the bird eating the worm, and then the hawk or the cat eating the bird. As something is dying, something is feeding off of that thing. We\'re simultaneously being born and decaying, and that is always so bewildering to me. The duality of sadness and joy make so much sense in that light. Feeling deep joy and laughter is similar to feeling like sadness in a way and crying. Like that Joni Mitchell line, \'Laughing and crying, it\'s the same release.\'” **anything** “It\'s a montage of many different images that I had stored in my mind from being with this person. I guess there\'s a thread of sweetness through it all, through things as intense as getting bit by a dog and having to go to the ER. It\'s like everything gets strung together like when you\'re falling in love; it feels like when you\'re in a relationship or in that space of getting to know someone. It doesn\'t matter what\'s happening, because you\'re just with them. I wanted to encapsulate something or internalize something of the beauty of that relationship.” **forwards beckon rebound** “That\'s actually one of my favorite songs on the album. I really enjoy playing it. It feels like a driving lullaby to me, like something that\'s uplifting and motivating. It feels like an acknowledgment of a very flawed part of humanness. It\'s like there\'s both sides, the shadow and the light, deciding to hold space for all of it as opposed to rejecting the shadow side or rejecting darkness but deciding to actually push into it. When we were in the studio recording that song, this magic thing happened because I did a lot of these rhythms with a paintbrush on my guitar. I\'m just playing the guitar strings with it. But it sounded like it was so much bigger, because the paintbrush would get all these overtones.” **heavy focus** “It\'s another love song on the album, I feel. It was one of the first songs that I wrote when I was with this person. The heavy focus of when you\'re super fixated on somebody, like when you\'re in the room with them and they\'re the only one in the room. The kind when you\'re taking a camera and you\'re focusing on a picture and you\'re really focusing on that image and the way it\'s framed. I was using the metaphor of the camera in the song, too. That one feels very bittersweet for me, like taking a portrait of the spirit of the energy of the moment because it\'s the only way it lasts; in a way, it\'s the only way I\'ll be able to see it again.” **half return** “There’s this weird crossover to returning home, being around my dad, and reverting back to my child self. Like when you go home and you\'re with your parents or with siblings, and suddenly you\'re in the role that you were in all throughout your life. But then it crosses into the way I felt when I had so much teenage angst with my 29-year-old angst.” **come** “This thing happened while we were out there recording, which is that a lot of people were experiencing deaths from far away because of the pandemic, and especially a lot of the elderly. It was hard for people to travel or be around each other because of COVID. And while we were recording, Phil\'s grandmother passed away. He was really close with her. I had already started this song, and a couple of days before she died, she got to hear the song.” **zombie girl** “There’s two tracks on the record that weren\'t written during the session, and this is one of them. It\'s been around for a little while. Actually, Big Thief has played it a couple of times at shows. It was written after this very intense nightmare I had. There was this zombie girl with this really scary energy that was coming for me. I had sleep paralysis, and there were these demons and translucent ghost hands fluttering around my throat. Every window and door in the house that I was staying in was open and the people had just become zombies, and there was this girl who was arched and like crouched next to my bed and looking at me. I woke up absolutely terrified. Then the next night, I had this dream that I was with this person and we were in bed together and essentially making love, but in a spirit-like way that was indescribable. It was like such a beautiful dream. I was like really close with this person, but we weren\'t together and I didn\'t even know why I was having that dream, but it was foreshadowing or foretelling what was to come. The verses kind of tell that story, and then the choruses are asking about emptiness. I feel like the zombie, the creature in the dream, represents that hollow emptiness, which may be the thing that I feel most avoidant of at times. Maybe being alone is one of the things that scares me most.” **not a lot, just forever** “The ‘not a lot’ in the title is the concept of something happening infinitely, but in a small quantity. I had never had that thought before until James \[Krivchenia, Big Thief drummer\] brought it up. We were talking about how something can happen forever, but not a lot of it, just forever. Just like a thin thread of something that goes eternally. So maybe something as small as like a bird shedding its feather, or like maybe how rocks are changed over time. Little by little, but endlessly.” **dragon eyes** “That one feels the most raw, undecorated, and purely simple. I want to feel a sense of belonging. I just want a home with you or I just want to feel that. It\'s another homage to love, tenderness, and grappling with my own shadows, but not wanting to control anyone and not wanting to blame anyone and wanting to see them and myself clearly.” **my angel** “There is this guardian angel feeling that I\'ve always had since I was a kid, where there\'s this person who\'s with me. But then also, ‘Who is my angel? Is it my lover, is it part of myself? Is it this material being that is truly from the heavens?’ I\'ve had some near-death experiences where I\'m like, \'Wow, I should have died.\' The song\'s telling this near-death experience of being pushed over the side of the cliff, and then the angel comes and kisses your eyelids and your wrists. It feels like a piercing thing, because you\'re in pain from having fallen, but you\'re still alive and returning to your oxygen. You expect to be dead, and then you somehow wake up and you\'ve been protected and you\'re still alive. It sounds dramatic, but sometimes things feel that dramatic.”

“My music is not as collaborative as it’s been in the past,” Jeff Parker tells Apple Music. “I’m not inviting other people to write with me. I’m more interested in how people\'s instrumental voices can fit into the ideas I’m working on.” As his career has evolved, the jazz guitarist and member of post-rock band Tortoise has become more comfortable writing compositions as a solitary exercise. While 2016\'s *The New Breed* featured a host of contributors, *Suite for Max Brown* finds the Los Angeles-based player eager to move away from the delirious funk-jazz of earlier works and towards something more unified and focused on repetition and droning harmonies. “I used to ask my collaborators to bring as much of the songwriting to the compositions as I do. Now, I’m just trying to prove to myself that I can do it on my own.” Parker handles most of the instruments on *Max Brown*, but familiar faces pop up throughout. The opening track, “Build a Nest,” features vocals from Parker’s daughter, Ruby, and “Gnarciss” includes performances from Makaya McCraven on the drums, Rob Mazurek on trumpet, and Josh Johnson on alto saxophone. Other frequenters of Parker’s orbit, like drummer Jamire Williams, appear throughout. But *Max Brown* is Parker’s record first and foremost, and the LP finds him less willing to give in to jazz’s typical demands of dynamic improvisation and community-oriented song-building. Here, Parker asserts himself as an ecstatic solo voice, where on earlier albums the soft-spoken musician may have been more willing to give way to his fellow bandmates. *Suite for Max Brown* is an ambitious sonic experiment that succeeds in its moves both big and small. “I like when music is able to enhance the environment of everyday life,” Parker says. “I would like people to be able to find themselves within the music.” Above all, *Suite for Max Brown* pays homage to the most important figures in Parker’s life. *The New Breed*, which was finished shortly after Parker’s father passed away, took its title from a store his father owned; *Max Brown* is derived from his mother’s nickname, and Parker felt an urgent desire to honor her while she was still able to hear it. “My mother has always been really supportive and super proud of the work I’ve done,” he says. “I wanted to dedicate an album to her while she’s still alive to see the results. She loves it, which means so much.” It’s an ode to his mother’s ambition, and a record that stands in awe of her achievements, even though they’re quite different from Jeff’s. “She had a stable job and collected a 401(k). My career as a musician is 180 degrees the opposite of that, but I’m still inspired by her work ethic.”

“I’m always looking for ways to be surprised,” says composer and multi-instrumentalist Jeff Parker as he explains the process, and the thinking, behind his new album, Suite for Max Brown, released via a new partnership between the Chicago–based label International Anthem and Nonesuch Records. “If I sit down at the piano or with my guitar, with staff paper and a pencil, I’m eventually going to fall into writing patterns, into things I already know. So, when I make music, that’s what I’m trying to get away from—the things that I know.” Parker himself is known to many fans as the longtime guitarist for the Chicago–based quintet Tortoise, one of the most critically revered, sonically adventurous groups to emerge from the American indie scene of the early nineties. The band’s often hypnotic, largely instrumental sound eludes easy definition, drawing freely from rock, jazz, electronic, and avant-garde music, and it has garnered a large following over the course of nearly thirty years. Aside from recording and touring with Tortoise, Parker has worked as a side man with many jazz greats, including Nonesuch labelmate Joshua Redman on his 2005 Momentum album; as a studio collaborator with other composer-musicians, including Makaya McCraven, Brian Blade, Meshell N’Degeocello, his longtime friend (and Chicago Underground ensemble co-founder) Rob Mazurek; and as a solo artist. Suite for Max Brown is informally a companion piece to The New Breed, Parker’s 2016 album on International Anthem, which London’s Observer honored as the best jazz album of the year, declaring that “no other musician in the modern era has moved so seamlessly between rock and jazz like Jeff Parker. As guitarist for Chicago post-rock icons Tortoise, he’s taken the group in new and challenging directions that have kept them at the forefront of pop creativity for the last twenty years. As of late, however, Parker has established himself as one of the most formidable solo talents in modern jazz.” Though Parker collaborates with a coterie of musicians under the group name The New Breed, theirs is by no means a conventional “band” relationship. Parker is very much a solo artist on Suite for Max Brown. He constructs a digital bed of beats and samples; lays down tracks of his own on guitar, keyboards, bass, percussion, and occasionally voice; then invites his musician friends to play and improvise over his melodies. But unlike a traditional jazz session, Parker doesn’t assemble a full combo in the studio for a day or two of live takes. His accompanists are often working alone with Parker, reacting to what Parker has provided them, and then Parker uses those individual parts to layer and assemble into his final tracks. The process may be relatively solitary and cerebral, but the results feel like in-the-moment jams—warm-hearted, human, alive. Suite for Max Brown brims with personality, boasting the rhythmic flow of hip hop and the soulful swing of jazz. “In my own music I’ve always sought to deal with the intersection of improvisation and the digital era of making music, trying to merge these disparate elements into something cohesive,” Parker explains. “I became obsessed maybe ten or fifteen years ago with making music from samples. At first it was more an exercise in learning how to sample and edit audio. I was a big hip-hop fan all my life, but I never delved into the technical aspects of making that music. To keep myself busy, I started to sample music from my own library of recordings, to chop them up, make loops and beats. I would do it in my spare time. I could do it when I was on tour—in the van or on an airplane, at a soundcheck, whenever I had spare time I was working on this stuff. After a while, as you can imagine, I had hours and hours of samples I had made and I hadn’t really done anything with them “So I made The New Breed based off these old sample-based compositions and mixed them with improvising,” he continues. “There was a lot of editing, a lot of post-production work that went into that. That’s in a nutshell how I make a lot of my music; it’s a combination of sampling, editing, retriggering audio, and recording it, moving it around and trying to make it into something cohesive—and make it music that someone would enjoy listening to. With Max Brown, it’s evolved. I played a lot of the music myself. It’s me playing as many of the instruments as I could. I engineered most it myself at home or during a residency I did at the Headlands Center for the Arts [in Sausalito, California] about a year ago.” His New Breed band-mates and fellow travelers on Max Brown include pianist-saxophonist Josh Johnson; bassist Paul Bryan, who co-produced and mixed the album with Parker; piccolo trumpet player Rob Mazurek, his frequent duo partner; trumpeter Nate Walcott, a veteran of Conor Oberst’s Bright Eyes; drummers Jamire Williams, Makaya McCraven, and Jay Bellerose, Parker’s Berklee School of Music classmate; cellist Katinka Klejin of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra; and even his seventeen-year-old daughter Ruby Parker, a student at the Chicago High School of the Arts, who contributes vocals to opening track, “Build A Nest.” Ruby’s presence at the start is fitting, since Suite for Max Brown is a kind of family affair: “That’s my mother’s maiden name. Maxine Brown. Everybody calls her Max. I decided to call it Suite for Max Brown. The New Breed became a kind of tribute to my father because he passed away while I was making the album. The New Breed was a clothing store he owned when I was a kid, a store in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where I was born. I thought it would be nice this time to dedicate something to my mom while she’s still here to see it. I wish that my father could have been around to hear the tribute that I made for him. The picture on the cover of Max Brown is of my mom when she was nineteen.” There is a multi-generational vibe to the music too, as Parker balances his contemporary digital explorations with excursions into older jazz. Along with original compositions, Parker includes “Gnarciss,” an interpretation of Joe Henderson’s “Black Narcissus” and John Coltrane’s “After the Rain” (from his 1963 Impressions album). Parker recalls, “I was drawn to jazz music as a kid. That was the first music that really resonated with me once I got heavily into music. When I was nine or ten years old, I immediately gravitated to jazz because there were so many unexpected things. Jazz led me into improvising, which led me into experimenting in a general way, into an experimental process of making music.” Coltrane is a touchstone in Parker’s musical evolution. In fact, Parker recalls, he inadvertently found himself on a new musical path one night about fifteen years ago when he was deejaying at a Chicago bar and playing ‘Trane: “I used to deejay a lot when I lived in Chicago. This was before Serrato and people deejaying with computers. I had two records on two turntables and a mixer. I was spinning records one night and for about ten minutes I was able to perfectly synch up a Nobukazu Takemura record with the first movement of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme and it had this free jazz, abstract jazz thing going on with a sequenced beat underneath. It sounded so good. That’s what I’m trying to do with Max Brown. It’s got a sequenced beat and there are musicians improvising on top or beneath the sequenced drum pattern. That’s what I was going for. Man vs machine. “It’s a lot of experimenting, a lot of trial and error,” he admits. “I like to pursue situations that take me outside myself, where the things I come up with are things I didn’t really know I could do. I always look at this process as patchwork quilting. You take this stuff and stitch it together until a tapestry forms.” —Michael Hill

In 2016’s *American Band*, Drive-By Truckers co-founders Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley expressed their concerns about the sharp political divides that cut across US racial and socioeconomic lines. Since then, those complex moral issues have only gotten worse—leaving the Southern rock band no other choice but to report back on what they’ve learned. Hood is responsible for the bulk of the songs: He speaks directly to his children on issues like gun violence (“Thoughts and Prayers”) and child separation federal policies (“Babies in Cages”), expressing regret over the mess they’ve inherited. Cooley is at his most serious-minded on the powerful “Grievance Merchants,” offering a pointed critique on the rise of white supremacist ideology. The melancholy, fiddle-laced “21st Century USA” continues the band’s MO of defending the working class, conjuring the image of an economically depressed rural county and the employees who deserve their fair share.

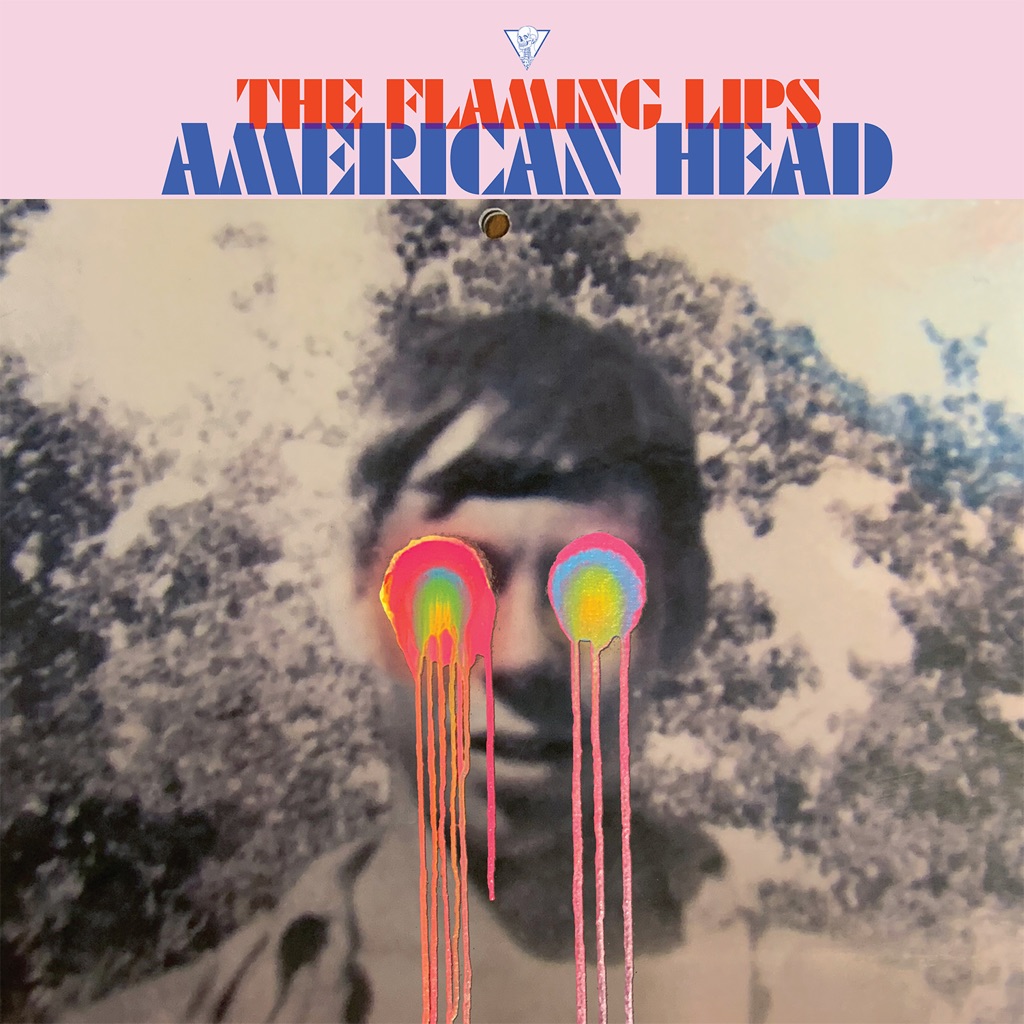

As a kid in the late ’60s, Wayne Coyne lived in fear of losing his oldest brother to drugs. “A lot of times, when he left the house on his motorcycle, I just thought, ‘He’s going to crack,’” the Flaming Lips frontman tells Apple Music. “If he didn\'t come home ’til 4:00, I would literally be up in my bed, scared that he was dead somewhere. That’s a real thing.” The Lips’ 16th studio LP is a haunting exploration of how we see the world as children and adults, high and sober, innocent and experienced—and its cover is a photo of Coyne’s brother in 1968. Featuring guest vocals from Kacey Musgraves, it’s also—by Flaming Lips standards—a song-oriented reimagining of American classic rock that’s inspired, in part, by a passage in the late Tom Petty’s biography about Petty and his band Mudcrutch stopping to record in Coyne’s native Oklahoma in 1974, as they traveled cross-country to make a go of it in LA. “There\'s never been anybody who’s ever uncovered it or ever noticed it or anything,” Coyne says of the Tulsa session. “But in that little gap, I wondered what that music would have been. So \[multi-instrumentalist\] Steven \[Drozd\] and I just took it further. Like, ‘What if Tom Petty and his band would have run into my older brother, if my brother went up there and they all got addicted to drugs and they got caught up in all this violence and they never became Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, but they made this very sad, fucked-up, beautiful record in Tulsa?’ And then we said, ‘Let\'s make that record.’ Here, Coyne tells the story of every song therein. **Will You Return / When You Come Down** “A lot of music is trying to tell you, ‘Dude, go blow your mind.’ And ‘Being insane is great.’ Steven and I\'ve always been like, ‘Dude, I think I\'m insane anyway.’ And I think we\'re glad to finally be embarrassed enough or old enough or whatever it is to say, ‘Yeah, we\'re singing about drugs.’ Part of it is our friends that have died from crashing their car. Part of it is our friends that have died from drug overdoses. And a part of the song is survivor’s guilt, while part of me was glad that I wasn\'t the one who died. But now as you look at yourself later, you’re like, ‘I wish was there with you.’ I think when you\'re a teenager and your friends die in a car accident, part of you has this fantasy you\'ll see them in heaven. Or if we live a thousand lives, you’ll be something else and I\'ll meet you again. And all of these are just fantasies, so you really have to face the horrible truth that you\'re never going to see that person again. The song’s you singing to these ghosts and hoping that they understand how you feel about it.” **Watching the Lightbugs Glow** “We like to always leave room for instrumentals. We like that it just floats along. You don\'t have to listen to it so intensely. Once we convinced Kacey Musgraves to sing on one track \[‘God and the Policeman’\], I thought, ‘Well, while we\'re there, why don\'t we try to do two songs?’ So we came up with another song, and then we end up coming up with a third song \[‘Flowers of Neptune 6’\], and she ended up liking all the things that we presented. I asked her about the song \[2018’s\] ‘Mother.’ She talked about this idea of light bugs, and they were floating around in her yard and she got one with a leaf and she put it in the house and she played some music for it and they danced together. All of this was on a very pleasant acid trip, but she did say that not all of her acid trips were pleasant—she understood sometimes they go horribly bad. While we were coming with this thing, I thought, well, let\'s just have her do kind of a wordless melodic thing, and we would let it be about that story. We could relate to it and she could relate to it and it would be real. And it would be true. I think that\'s why we put it second. Like, ‘Let\'s just not be in such a hurry to say more stuff, just let it just float along with the mood.’ But I wouldn\'t have done it without her. We would have never done it as one of us singing. It was made for her.” **Flowers of Neptune 6** “‘Flowers of Neptune’ came from an insanely great demo that Steven made, but it was long enough that we could envision it being a bigger, more epic song. As we started to make it, we were like, ‘I don\'t think it\'s as good if it keeps going too long, because it\'s got such a crescendo of emotion. Let’s just make it two songs.’ One, ‘Lightbugs,’ could be a little bit more fun and kind of floaty and melancholy—but optimistic. The other, ‘Flowers of Neptune,’ could be more powerful and personal. There is some connection to that idea that our older brothers and their friends, they were these characters that we didn\'t relate to. They were crazy and they were going to go to jail. They were going to go off to war, they were going to get in a fight, they were going to get in a motorcycle accident and we weren’t. And then at some point we realized their life and ours is the same. I am me because of them. You can\'t really express it, but in a song you can, because it\'s big and it\'s crescendos and it\'s emotional and you find somehow you\'re able to express this thing that we would never, ever consider saying to our real brothers, in real life. You\'d just be too embarrassed. But music wants you to go all the way.” **Dinosaurs on the Mountain** “I remember being in the back of the station wagon with my family as we were traveling down a highway, in the middle of the night, on our way to Pittsburgh. And seeing these giant trees, pretending that they were dinosaurs, falling over and killing each other. And also remembering that this is like the last time that I felt that I could just see fantasy and not worry that we\'re driving down a highway, my father might be falling asleep, and we could crash the car and die—all these things you start to think about when you\'re becoming an adult. The times we went back after, I didn\'t see the dinosaurs in the trees. They were just trees. You can\'t get that back. It’s trying to make that into a song that an adult can relate to instead of being like a children\'s storybook or a Disney movie.” **At the Movies on Quaaludes** “I only did quaaludes once, and I have to say, I didn\'t feel anything. There\'s a line at the very beginning of the novel *The Outsiders*—which when you live in Oklahoma, you read in junior high and high school because it\'s set in Tulsa—about coming out of a movie theater. You were so immersed in the movie that you forgot, ‘Oh yeah, this is real life out here.’ My brothers and their friends, they would go to movies all the time in the middle of the day and they would just be so completely fucked up. There was hardly any moments that they weren\'t on some drugs. And I just remembered for myself sometimes, the shock of being in a movie theater, so immersed in that, and you walk outside and you\'re back in real life, whereas I think sometimes they never came back to real life. It\'s just one big, long movie. So there\'s something wonderful about that. It\'s like a dream that you know is never going to come true, but the better to dream it and know it isn\'t going to come true. Or is it worse to not dream it at all?” **Mother I’ve Taken LSD** “This one is devastating for me. It has to be 1968, 1969—there’s a lot of talk about LSD. It’s in the news every day, and when we would be at school, dudes in suits would come with a briefcase full of drugs and say, ‘Don\'t take drugs. And especially don\'t take LSD, because it\'ll make you think that you can fly, and you\'ll go to the top of a bridge and jump off and you\'ll die.’ So all this is in our minds and I\'m only seven or eight years old. It’s like, ‘Fuck. The Beatles think it\'s cool, but the police think it\'s horrible. What do I do here?’ So my brother and my mother are sitting on the porch and they’re having a conversation. I remember my brother saying, ‘Well, mother, I\'ve taken LSD.’ I just couldn\'t believe it. My own brother is doing the things that the police are coming to school to tell me about and he’s going to go insane. I\'m singing about it like it\'s sad for her, but really, it was just sad for me. It’s stayed with me my whole life because it was such a blow.” **Brother Eye** “Steven was like, ‘Why don\'t you just write down some words and I\'ll make up a song around your words?’ Which we never do. Usually, he\'s got a melody and I\'ll put lyrics to it, or I\'ll have lyrics and stuff and he\'ll help me with melodies. I think I wrote out, \'Mother, I don\'t want you to die.’ And then he was like, ‘Well, you have too many songs about mothers. Let\'s do one about brothers.’ His older brothers and his younger brother, all of them, his whole family is dead. When his oldest brother died, I know it devastated him, and we really don\'t sing about it. But in this way of me presenting words to him, I know that he put it in a way of saying we\'re just doing a song. But both of us knew somewhere in there, we\'re singing about this heavy thing. When it came time to be like, ‘Well, are you going to sing it or am I going to sing it?’ I just told him, ‘I think you’ve got to sing that.’ And he was just like, ‘Oh shit.’” **You n Me Sellin’ Weed** “When I was 16 and 17, I started selling pot because everybody around me was selling pot and some were making better money than they were working in a restaurant like I was. But I didn\'t want to do it for very long, because I did fear that I\'d get put in jail or something worse. The second verse is about that. It sounds pretty gentle, but it\'s really about a friend of ours who was involved in a murder. He owed the drug dealer a lot of money and the drug dealer was threatening to kill his little girl. So he went over to his house and he stabbed \[the dealer\] to death. He was put in jail for murder and he was sentenced to spend the rest of his life there. And a year or two later, he committed suicide in jail. It\'s a blissful story about a state of mind for just a moment, before the violence and all these things rush in and kill you. I was very lucky that my experience stayed an adventure. That time could have been where everything went badly and our family destroyed itself. Because we saw it happen and because we knew them and they were just like us, I think it changed us to say, ‘Let\'s not let that happen.’” **Mother Please Don’t Be Sad** “When I was 17, there was a robbery happening in the restaurant that I was working in. The guys came in and I thought for sure that I was going to be killed. This song is what I was saying to myself while I laid on the floor, waiting to be shot in the head. I was going to stop at my mother\'s house after I got off work that night and leave my dirty work uniform there, and talk to her for a little bit. I\'m laying on the floor and I know that I\'m going to die. And I\'m thinking, ‘Mother is going to wonder where I\'m at because I\'m going to be late, and she\'s going to start to worry. Then the cops are going to show up like they do in all these horrible movies, and they\'re going to tell her that I died in the robbery.’ And that line, ‘Mother, please don\'t be sad’: I said that laying on the floor there because I just knew it was going to be horrible. It was me that was going to die, but I just thought I\'ll be dead in a second, and it\'s going to be horrible for her. I wanted her to know that I wasn\'t doing something dangerous, I wasn\'t doing something fucked up. I was just at work and this happened, so don\'t worry about it. This was just the chaos of the world. Sometimes there\'s nothing you can do. You\'re just in the wrong place at the wrong time.” **When We Die When We’re High** “That beat that Steve plays—in the hands of a lot of drummers, it would be flashy and it would be pompous, but he\'s doing these things that are just so effortless that you don\'t realize what an insane beat it is. And man, that one note with that beat, that\'s got a good menacing joy about it. And then to put that title to it. A friend of ours was killed in a car accident, and everybody in the car was completely zonked out. The car hits a telephone pole and part of his head is just completely taken off and he\'s just dead right there at the scene. This is real stuff. And part of you, what you do to get around just how brutal and how horrible this is, is you do music. Well, he was so high when he died that he wouldn\'t know he was dead. He\'s going to wake up later in the afterlife, everything will be cool. We\'re saying, ‘If you\'re high when you die, do you really die?’ It\'s ridiculous, but it\'s fun to sing.” **Assassins of Youth** “I think in the beginning, it was intended to be on that Deap Lips collaboration that we did with the girls from Deap Vally, and it just never really went anywhere. Something about it reminded us of ABBA. And what I liked about ABBA is that they\'re singing about something that sounds rebellious and revolutionary, but it\'s very sweet-sounding at the same time. And because English too wasn\'t their first language, I always felt like they didn\'t quite know what they were talking about, which was better. So we took this ridiculously overused line, ‘assassins of youth,’ and we pretended that we were like ABBA—we’re not quite sure what it means in English, but we know what it means in Swedish or whatever. It\'s just great, triumphant classic-rock stuff. It presents itself like it\'s an important message. And then when you dissect it, you’re like, ‘I\'m not sure what you\'re saying.’ That, to me, is wonderful.” **God and the Policeman (feat. Kacey Musgraves)** “When Kacey heard it, she came back to me and was like, ‘Now, this is the one. This is the one I want to be on, for sure.’ I kept looking at it like Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton. I thought it would be perfect for her, a song about a fugitive on the run. On the run from what, I don’t know, but it tied into another drug story, a friend of ours who got caught up in a bad drug deal. It sounds like I\'ve told this one before, but another guy I know, a drug dealer was telling him, ‘Well, if you don\'t pay me, I\'m going to kill you.’ So he went over to \[the dealer’s house\], and the drug dealer, he thought that he was bringing him what he owed him and he just went over there and killed the guy. And he said, ‘See you later. I\'ll never see my friends again. Better than being killed by this biker drug dealer.’ I can\'t talk too much about it, but I feel like enough time has gone by, I really don\'t even know if he\'s alive anymore.” **My Religion Is You** “It still feels like a folk song or religious song or something, but nothing in our life—my life, anyway—was ever so heavy that I had to turn to God. I always had my mother, my father, and plenty of people around to explain the mysteries of pain and all that to me. I remember, when we initially went to school, our first and second grade, we went to a Catholic school. And there\'d be a lot of talk about Jesus sacrificing himself for us. I didn\'t really understand. I would ask my mother, like, ‘Well, what do they mean? Why is Jesus dying? I don\'t want him to die. Why does he have to die for me?’ And she\'d say, ‘Well, these aren\'t things that most people have to deal with. It\'s for people who don\'t really have families and brothers. People don\'t love them, so Jesus loves them. They don\'t have anybody that will listen to them. So they need God to listen to them.’ And I said, ‘Well, my religion is you.’ She\'s like, ‘Yeah, I know.’”

Everything changed for The Beths when they released their debut album, Future Me Hates Me, in 2018. The indie rock band had long been nurtured within Auckland, New Zealand’s tight-knit music scene, working full-time during the day and playing music with friends after hours. Full of uptempo pop rock songs with bright, indelible hooks, the LP garnered them critical acclaim from outlets like Pitchfork and Rolling Stone, and they set out for their first string of shows overseas. They quit their jobs, said goodbye to their hometown, and devoted themselves entirely to performing across North America and Europe. They found themselves playing to crowds of devoted fans and opening for acts like Pixies and Death Cab for Cutie. Almost instantly, The Beths turned from a passion project into a full-time career in music. Songwriter and lead vocalist Elizabeth Stokes worked on what would become The Beths’ second LP, Jump Rope Gazers, in between these intense periods of touring. Like the group’s earlier music, the album tackles themes of anxiety and self-doubt with effervescent power pop choruses and rousing backup vocals, zeroing in on the communality and catharsis that can come from sharing stressful situations with some of your best friends. Stokes’s writing on Jump Rope Gazers grapples with the uneasy proposition of leaving everything and everyone you know behind on another continent, chasing your dreams while struggling to stay close with loved ones back home. "If you're at a certain age, all your friends scatter to the four winds,” Stokes says. “We did the same thing. When you're home, you miss everybody, and when you're away, you miss everybody. We were just missing people all the time.” With songs like the rambunctious “Dying To Believe” and the tender, shoegazey “Out of Sight,” The Beths reckon with the distance that life necessarily drives between people over time. People who love each other inevitably fail each other. “I’m sorry for the way that I can’t hold conversations/They’re such a fragile thing to try to support the weight of,” Stokes sings on “Dying to Believe.” The best way to repair that failure, in The Beths’ view, is with abundant and unconditional love, no matter how far it has to travel. On “Out of Sight,” she pledges devotion to a dearly missed friend: “If your world collapses/I’ll be down in the rubble/I’d build you another,” she sings. “It was a rough year in general, and I found myself saying the words, 'wish you were here, wish I was there,’ over and over again,” she says of the time period in which the album was written. Touring far from home, The Beths committed themselves to taking care of each other as they were trying at the same time to take care of friends living thousands of miles away. They encouraged each other to communicate whenever things got hard, and to pay forward acts of kindness whenever they could. That care and attention shines through on Jump Rope Gazers, where the quartet sounds more locked in than ever. Their most emotive and heartfelt work to date, Jump Rope Gazers stares down all the hard parts of living in communion with other people, even at a distance, while celebrating the ferocious joy that makes it all worth it--a sentiment we need now more than ever.

The music of Darren Cunningham, the British electronic musician known as Actress, is notoriously difficult to categorize. Over the past 15 years, he has evaded the confines of more familiar dance music with avant-garde, abstract compositions that gaze inward. Although he references house, techno, dubstep, and R&B, he deconstructs, twists, and stretches them into practically unrecognizable forms. But make no mistake, his records are still intensely emotional—vivid soundscapes so full of depth and light that they can feel overwhelming. And *Karma & Desire*, his seventh LP, feels, in many ways, like mourning. Guided by meandering piano arpeggios and hushed vocals about heaven and prayer, it evokes funereal images of death and rebirth (“I’m thinking/Sinking/Down/In Heaven,” Zsela sings on “Angels Pharmacy”). A glitchy, fuzzy texture permeates the album, as if the tracks had been passed through an old-fashioned Instagram filter, and it builds a general sense of uneasiness. Actual beats are scarce, but those that do appear feel almost meditative (“Leaves Against the Sky,” “XRAY”), as if to provide relief from the amorphous expanse. It’s easy to see the metaphor for getting lost in dark corners of your own mind, and the solace that you feel when reality returns.

After recent mixtape “88”, Actress reveals new album "Karma & Desire". ‘Walking Flames’ featuring Sampha is out now. “Karma & Desire” includes guest collaborations from Sampha, Zsela and Aura T-09 and more. It’s “a romantic tragedy set between the heavens and the underworld” says Actress (Darren J. Cunningham) “the same sort of things that I like to talk about – love, death, technology, the questioning of one's being”. The presence of human voices take the questing artist into new territory. ‘Walking Flames’: “These are like graphics that I’ve never seen / My face on another human being / The highest resolution / Don't breathe the birth of a new day.” Flute-like melodies contributed by Canadian organist and instrument builder Kara-Lis Coverdale.

one long song recorded nowhere between May 2019 and May 2020 released Aug. 7th, 2020 as a 2xLP by P.W. Elverum & Sun box 1561 Anacortes, Wash. U.S.A. 98221

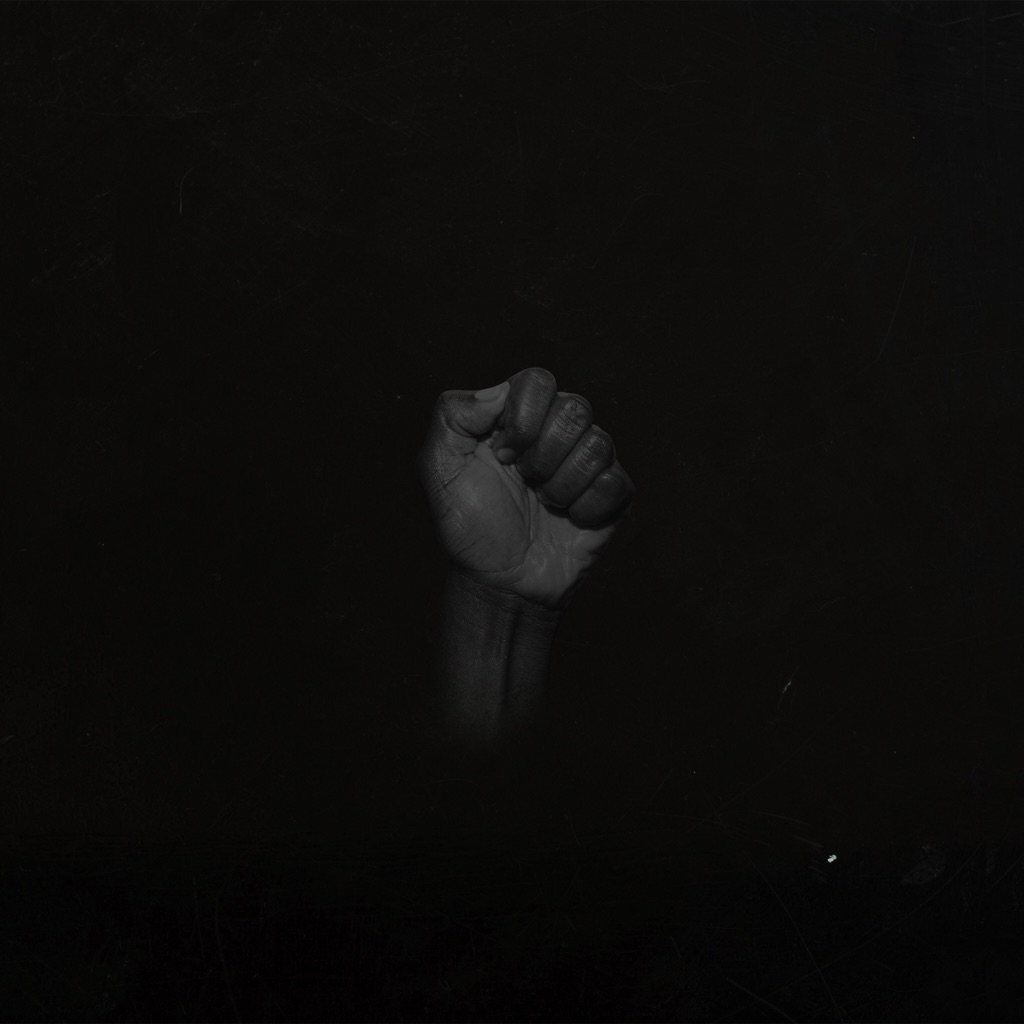

Released on Juneteenth 2020, the third album by the enigmatic-slash-anonymous band Sault is an unapologetic dive into Black identity. Tapping into ’90s-style R&B (“Sorry Ain’t Enough”), West African funk (“Bow”), early ’70s soul (“Miracles”), churchy chants (“Out the Lies”), and slam-poetic interludes (“Us”), the flow here is more mixtape or DJ set than album, a compendium of the culture rather than a distillation of it. What’s remarkable is how effortless they make revolution sound.

Proceeds will be going to charitable funds

Chaos Wonderland is the seventh full-length album by Colorama, depending on who you believe (it’s the ninth if you include the ‘mini’ albums). Why Chaos Wonderland? Colorama frontman Carwyn Ellis explains, “well.. I’ve travelled a lot these last few years and I’ve seen a lot of places in total flux, upheaval and yes - chaos. Nowhere more so than at home. But at the same time, I’ve seen much to make me cheerful, not least in the beautiful sights I’ve witnessed, along with the warmth and inherent goodness of the vast majority of people I’ve encountered”. It was recorded at Shawn Lee’s ‘Shop’ Studio in early 2018, during the gaps in between Ellis’ stints touring around the world with the Pretenders. Shawn Lee has had an incredibly productive (30-odd solo albums to date) career, featuring collaborations with a myriad of different artists including Clutchy Hopkins, Tony Joe White, Darondo, Money Mark, Tommy Guerrero, Psapp, Little Barrie and Saint Etienne, with whom he worked on the ‘Home Counties’ album, which is where he and Carwyn Ellis first worked together, on their 2017 single, ‘Dive’. With both musicians being prodigiously talented multi-instrumentalists, the album was recorded surprisingly quickly, and with very little added help, although Lay Low, the brilliant Icelandic singer, added her vocal magic to the funky paean to love, ‘Me & She’. Other highlights include ‘Dusty Road’, about an outcast on the run, the cosmic tiki-flavoured ‘Black Hole’, boombastic opener ‘And’ and the smoothly soulful ‘Reconciliation’, which takes on a whole new meaning in the current environment we’ve found ourselves in. The album was recorded, then Carwyn got inundated with other projects, and time flew by... Fast forward to 2020. In March, everything ground to a halt for most of us in the UK, including Carwyn. This busiest of musicians now found he had time on his hands and... music to release! So, finally, we have Chaos Wonderland, the ‘new’ album by Colorama.

Fontaines D.C. singer Grian Chatten was with bandmates Tom Coll and Conor Curley in a pub somewhere in the US when the words “Happy is living in a closed eye” came to him. It was possibly in Chicago, he thinks, and certainly during their 2019 tour. “We were playing pool and drinking some shit Guinness,” he tells Apple Music. “I was drinking an awful lot and there was a sense of running away on that tour—because we were so overworked. The gigs were really good and full of energy, but it almost felt like a synthetic, anxious energy. We were all burning the candle at both ends. I think my subconscious was trying to tell me when I wrote that line that I was not really facing reality properly. Ever since I\'ve read Oscar Wilde, I\'ve always been fascinated by questioning the validity of living soberly or healthily.” The line eventually made its way into “Sunny” a track from the band’s second album *A Hero’s Death*. Like much of the record, that unsteady waltz is an absorbing departure from the rock ’n’ roll punch of their Mercury-nominated debut, *Dogrel*. Released in April 2019, *Dogrel* quickly established the Irish five-piece as one of the most exciting guitar bands on their side of the Atlantic, throwing them into an exacting tour and promo schedule. When the physical and mental strains of life on the road bore down—on many nights, Chatten would have to visit dark memories to reengage with the thoughts and feelings behind some songs—the five-piece sought relief and refuge in other people’s music. “We found ourselves enjoying mostly gentler music that took us out of ourselves and calmed us down, took us away from the fast-paced lifestyle,” says Chatten. “I think we began to associate a particular sound and kind of music, one band in particular would have been The Beach Boys, that helped us feel safe and calm and took us away from the chaos.” That, says Chatten, helps account for the immersive and expansive sound of *A Hero’s Death*. With their world being refracted through the heat haze of interstate highways and the disconcerting fog of days without much sleep, there’s a dreaminess and longing in the music. It’s in the percussive roll of “Love Is the Main Thing” and the harmonies swirling around the title track’s rigorous riffs. It drifts through the uneasy reflection of “Sunny.” “‘Sunny’ is hard for me to sing,” says Chatten, “just because there are so many long fucking notes. And I have up until recently been smoking pretty hard. But I enjoy the character that I feel when I sing it. I really like the embittered persona and the gin-soaked atmosphere.” While *Dogrel*’s lyrics carried poetic renderings of life in modern Dublin, *A Hero’s Death* burrows inward. “Dublin is still in the language that I use, the colloquialisms and the way that I express things,” says Chatten. “But I consider this to be much more a portrait of an inner landscape. More a commentary on a temporal reality. It\'s a lot more about the streets within my own mind.” Throughout, Chatten can be found examining a sense of self. He does it with bracing defiance on “I Don’t Belong” and “I Was Not Born,” and with aching resignation on “Oh Such a Spring”—a lament for people who go to work “just to die.” ”I worked a lot of jobs that gave me no satisfaction and forced me to shelve temporarily who I was,” says Chatten. “I felt very strongly about people I love being in the service industry and having to become somebody else and suppress their own feelings and their own views, their own politics, to make a living. How it feels after a shift like that, that there is blood on your hands almost. You’re perpetuating this lie, because it’s a survival mechanism for yourself.” Ambitious and honest, *A Hero’s Death* is the sound of a band protecting their ideals when the demands of being rock’s next big thing begin to exert themselves. ”One of the things we agreed upon when we started the band was that we wouldn\'t write a song unless there was a purpose for its existence,” says Chatten. “There would be no cases of churning anything out. It got to a point, maybe four or five tunes into writing the album, where we realized that we were on the right track of making art that was necessary for us, as opposed to necessary for our careers. We realized that the heart, the core of the album is truthful.”

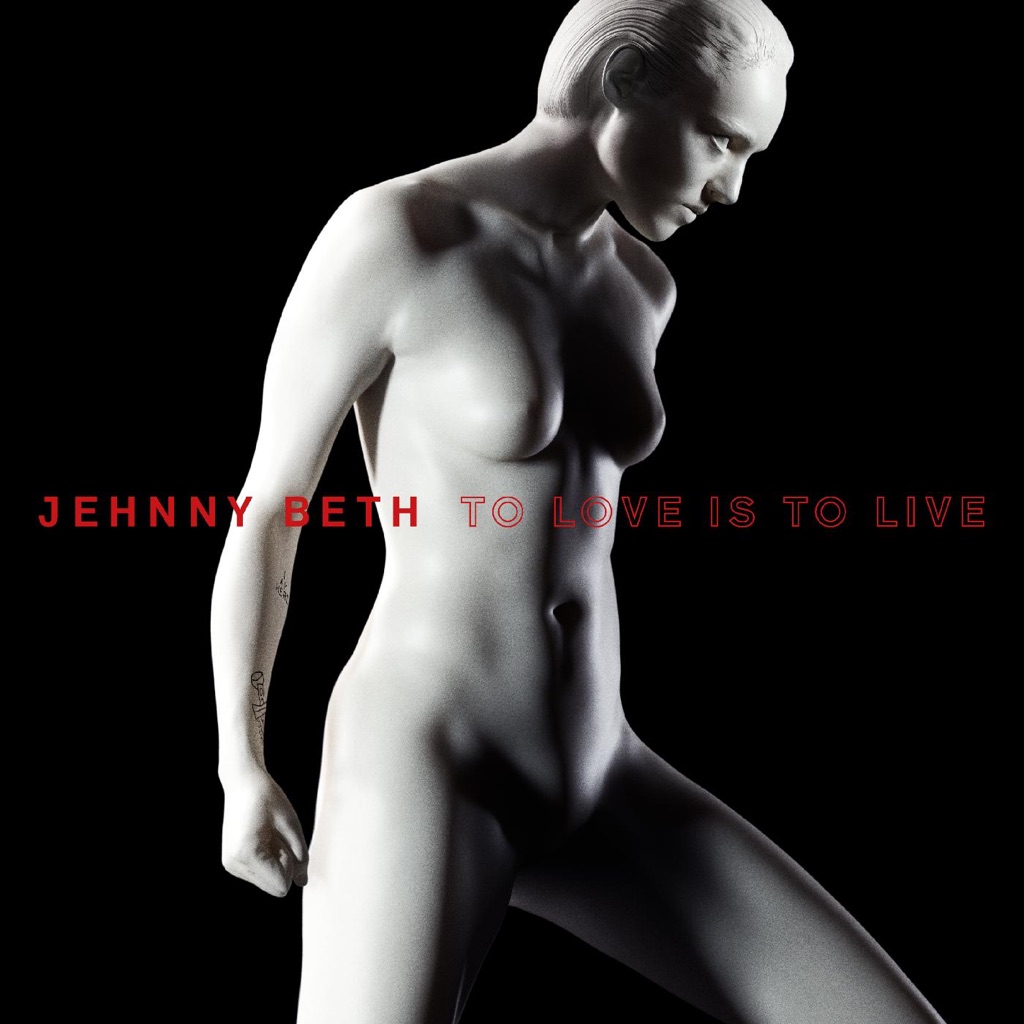

“I needed to change things in my personal life, but also in the way that I was working,” Jehnny Beth tells Apple Music of her debut solo LP. “It was exhilarating for me to begin from a clean slate, starting something new and feeling that fear of the unknown again.” Best known as the lead singer and co-writer for UK post-punk band Savages, Beth was repeatedly told that it was too much of a risk to branch out on her own and that she should build on what she had done before. She followed her instinct instead, relying on her own resources and several collaborators to bring her project to life, including British producers/audio engineers Flood and Atticus Ross and longtime creative partner Johnny Hostile. *TO LOVE IS TO LIVE* is a natural display of Beth’s experimental curiosity—unleashing unsettling synths and industrial percussive elements as she gets in touch with feelings of self-doubt and her sexuality. “It was an inner voice, something that was calling me to do this—otherwise, there’s the danger of losing myself completely,” Beth says. “I didn\'t want to be enslaved to one genre of music, and I didn\'t want to be one of those singers who are slaves to their dance.” Here, Beth walks us through the album, one song at a time. **I Am** “When I heard Atticus Ross’ production, I knew it was going to be the opener. With Savages, my voice was connected to the intensity of the guitars and the drums with that classic punk-rock band scenario. And he was creating the same intensity but with strings, and instruments that were different. I love that it creates a sense of suspense and wonder. When you finish the track, you\'re left with questions like \'What is coming next?\' The song was written by me and Johnny Hostile, and it was during the very early stages of exploration. During one of our lab experiments, we tried to pitch my voice in different styles and tonologies, and we found one that was really pitched down. There\'s a multiplicity of voices on the record. And I think the purpose is to unlock the forbidden thoughts and intimate thoughts that we believe are shameful. I think that we push them down. But as humans, we have contradictory thoughts—and we battle with the idea of identity and the idea of good and bad all the time. There is danger in trying to repress those hidden voices and not giving the space for them. So that\'s why it was important to open with that voice and not my voice.” **Innocence** “It was produced by Flood in his studio in London. He has this capacity of getting obsessed with details and muting all the important parts. You don\'t understand what he\'s listening to or why he\'s even listening to that. So I got frustrated, and he kicked me out of the studio and asked me to come back an hour later. And then I was very frustrated and angry. I came back and heard the mix, and then came this moment where I was hearing myself in a way that I had never heard myself before. It brought me to tears. I wrote the lyrics early on in the process of making the record; I placed it as the starting point of the journey—the same way a novelist would start with the shameful thoughts for his novel, and start from there to grow. Not trying to avoid it, but put it at the center—and I asked myself what is the thought that keeps you up at night that you never reveal to anyone. And it was the idea of lost innocence, in the sense of feeling isolated and not being able to connect with the rest of humanity. It\'s about the reality of living in busy cities as well. The more you close your eyes to people, the more walled up you become. You see the reality of a city which doesn\'t treat everybody equally or the same way, and the anger that it creates.” **Flower** “It\'s a classic scenario of distance being sexier than the touch, and celebrating female nudity in a hypnotic way. I was inspired by all the girls in Jumbo\'s, which is an LA pole-dancing club I go to when I\'m in LA. I really love the atmosphere of the club and how freeing it is, and how exciting and frightening it is at the same time. I love that tension. Hostile composed it for me, and when it was finished, I felt it wasn\'t for me. I wasn\'t sure, so I sent it to my friend Romy Madley Croft \[The xx vocalist/guitarist\], and she replied in capital letters that I have to have this song on the record and that it was great to hear me in a different context. I decided that I was going to check with myself if I was feeling uncomfortable. And if I was feeling uncomfortable, it was a good sign that I was going in the right direction.” **We Will Sin Together** “It’s an invitation to do bad things together and the realization that love is part of that. That there\'s no right or wrong; there\'s only in and out. If you decide to break a sweat and participate in life, you are going to make mistakes. So for me, it\'s what I call a post-romantic love song. It tries to reach beyond the ancestral codes of romanticism, because they too often generate frustration. Romy sang backing vocals on it. We were working on the song in LA and I asked her to sit behind the mic. I love her voice. I think it naturally carries a lot of emotion and never sounds fabricated, and it also suits the song perfectly. It\'s one of my favorite tracks of the record.” **A Place Above (feat. Cillian Murphy)** “I had written the texts and I wondered if \[Irish actor\] Cillian could read it. Because, again, I wanted this multiplicity of voices on the record. I knew he was a fan of Savages, and I was a fan of his; I think he has one of the best voices in modern cinema. He did it without hearing any music, which I think was great and perfect. I remember what Cillian wrote to me when he wrote the text. He said, ‘It\'s big stuff.’ And then he said, \'It should be done in a slow way, a quiet way.\' He made it personal, as if you were hearing someone\'s personal thoughts that you suddenly had access to. It’s a little bit like in *Wings of Desire* \[German film director Wim Wenders’ 1987 film\]. The angels have access to people\'s thoughts and minds, and they can hear their secret thoughts.” **I’m the Man** “What I wanted to say with this song is that the root of evil isn\'t just on the other side—it lives inside of each of us. It\'s implanted in our core by generations of parents or grandparents in society, and we must stay strong and aware to overcome the aggressive power to control us. It\'s about facing my own responsibility for the evil of this world. It\'s important for arts, in general, to show our own complexities to our faces. I wanted to portray the evil of this world and put it on me, wear the mask of people. Because it\'s impossible for me, as an artist, to draw a line between good and bad and just pretend that I\'m always standing on the right side of the fence. Sometimes it\'s about looking on the other side, trying to understand your own thoughts and your own darkness and your own violence.” **The Rooms** “It’s a resolution moment, kind of a resting in contrast to ‘I’m the Man.’ I wrote and recorded hours of piano and vocals on my own in the studio. It\'s a calm description of an orgy where women have all the power. It comes from a line by Francis Bacon, who said something like, ‘When I went into the rooms of pleasure, I didn\'t stay in the rooms where they celebrate acceptable modes of loving, I went into the rooms which are kept secret.’ It\'s a beautiful way to describe desire and exploration.” **Heroine** “I think ‘Heroine’ is a cry to be free. I have had quite a journey with this song, because it was originally called ‘Heroism.’ Because I wanted to talk about the idea of freedom and role models and the fact that freedom is, in fact, frightening. I was told I should play the heroine in ‘Heroine.’ I couldn\'t really step into the shoes of that big character that way, that was positive in a way. You need to be able to embody positive characters as much as you embody frightening and contradictory characters. So that was the realization for me. Sometimes you look for role models around, but you have to also be able to see what\'s within you. And for me to hold the people around me to get there, to take me there.” **How Could You (feat. Joe Talbot)** “One of my favorite songs about jealousy is ‘Why’d Ya Do It?’ by Marianne Faithfull from *Broken English*, and I always wanted to write something about jealousy. I\'ve had to work very hard to conquer jealousy in order to live, and it wasn\'t easy. I had to fight against all my conditioning and invent new rules for myself. I\'ve learned so much from the process, but it\'s something you constantly need to check yourself with. Because jealous people always think they\'re right. Which I think is my main problem with it; when I was jealous, I was tempted to think I was right, because jealousy makes you think that there isn\'t a greater pain than yours. I couldn\'t imagine a better person as Joe \[Talbot, IDLES vocalist\] to be a jealous man on this song. Because he knows, and he understands, what it means to take control of this human instinct. And he\'s been jealous. He\'s been a bad guy; he knows what it\'s like. When I discovered IDLES, I thought they were shining a light into what it means to be a man in a band. I knew Joe was going to write something brilliant about anger and jealousy, and he did.” **French Countryside** “I wrote it as if I was writing a soundtrack for *Call Me by Your Name*. That\'s what I had in mind: the summer, the countryside, and the promise of love. I wrote the lyrics much before that. I wrote them in a plane when I thought we were going to crash, and I was making a list of promises of what I would do better if I survived. And obviously when the plane landed safely, I forgot about my list of promises. When I revisited the idea I realized, oh god, we forget about the urgency of life. I was suddenly facing those ideas again, and I really wanted to make something before I go too. It contrasts so much with the rest of the record, but that\'s really on purpose.” **Human** “I knew I wanted to make a record that would give a sense of the journey, holding a narrative from start to finish. It was part of my early discussions with Atticus. I didn\'t want to make a collection of songs. I wanted the record to be a world you can live in. He had this idea of reintroducing the dark voice at that point with the same lyrics. And again, bringing in those orchestral strings, and that sort of drama and intensity and suspense. So we\'re going back to the beginning, but we\'ve evolved. The idea of the lyrics came to me when I was reading about people who go to digital rehab, because they\'ve lost the sense of self and connection to their life. It felt that it was interesting to finish the album by saying I used to be a human being and now I live in the web. Because I think we can relate to that more and more.”

All copies of the cassette are now sold out. They will ship to arrive on or around the release date of June 19. SO THIS TAPE STARTED while the entire band was decamped at an undisclosed location working on the next Mountain Goats album, and I had brought books with me to read, and one of them was Pierre Chuvin’s A Chronicle of the Last Pagans, which I was reading as research material for another thing I’m working on; and it’s been a long time since I sat around playing music and thinking about antiquity, but I used to do it all the time, and several of you know that because the old tapes are all littered with stories about Ajax and Agamemnon and the cult of Cybele, stories which, when I was learning them, got me so fired up that as soon as I got out of class I’d drive home in my yellow 1969 Superbeetle and write songs about them. At our undisclosed location, one morning, immersed day and night in our work but also beginning to get the feeling that the increasingly febrile pitch of the newsfeed would continue to rise until it reached registers not seen in a while, I had a thought—what if the next Mountain Goats album was just songs about these pagans? And I wrote down the title “Aulon Raid.” I GOT HOME about seven days later and the world was a very different place by then, and I took my old boombox down from the shelf where it sits flanked by brass deities from a former period of my life, and I got a wild idea to stand it on its end to reduce the unpleasant clicking that made it unusable—the hum & grind are one thing, basically ambient noise that adds to the pleasure of the sound if you’re into it, but the clicking I’m talking about developed sometime in the early 2000s and is not a conscriptable effect, it renders the Panasonic unusable. Unless you stand it on its end, I learned, by accident, one day during the early weeks of the new days. AS THESE DAYS WERE DEVELOPING, I realized, as I’d feared a week before, that the work schedule my band and I had planned for spring probably wouldn’t be panning out. The four members of the band split up our touring income equally, nightly pay & sales of merchandise; before we split up that income, we pay several people from gross receipts: Brandon, our soundman and tour manager of over a decade; Trudy, who works the merch table with style and flair; and Avel, who manages the stage no matter how unmanageable I become. I can’t do what I do without these people and I take great pleasure in trying to make their job a fun place to work. All seven of us rely on the Mountain Goats for our paycheck. The boombox and I knew we had to do something. Back in the early nineties, when I’d first met Peter Hughes, I wanted to make a tape to be on his label, Sonic Enemy. It was Christmas break and I was on a hot streak, so I decided to try to make a full tape over the course of the break. That tape became Transmissions to Horace, which consisted entirely of work done on a daily basis during that span. I haven’t tried anything like that in a while. I WROTE A SONG EVERY DAY for the next ten days while reading A Chronicle of the Last Pagans, starting with “Aulon Raid” and working in exactly the style I used to work in: read until something jumps out at me; play guitar and ad-lib out loud until I get a phrase I like; write the lyrics, get the song together, record immediately. Those original lyrics, exactly as written on the cardstock I save from comic books I buy, with corrections and everything, will be randomly inserted into orders; each is one of a kind, an original first draft of the lyrics to the first all-boombox Mountain Goats album since All Hail West Texas. It seems unlikely that I will ever again offer original drafts of lyrics for sale or otherwise, but pandemics call for wild measures. I dedicate this tape to everybody who’s waited a long time for the wheels to sound their joyous grind: may they grind us into a safe future where we gather once again in rooms to sing songs about pagan priests & hidden shelters, and where we see each other face to face. Hail the Panasonic! Hail the inscrutable engines of chance! Hail Cybele! —John Darnielle, Durham, NC, March 2020

In the months leading up to his first tour date supporting 2019’s *Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest*, Bill Callahan was struck by what he describes to Apple Music as “the perfect inspiration for the perfect goal”: Before he left home, he’d try to write and record another album. “I\'m the type of person that can only do one thing at a time,” he says. “I just knew that if I didn\'t finish it before the tour, then it would be a year before I could even think about working on these songs. And I knew that if I did finish it, I would feel like a million bucks.” So Callahan drew up some deadlines for himself and began finishing and fleshing out songs he had lying around, work he hadn’t been able to find a home for previously. *Gold Record* is the short story collection to his other LPs\' novels—a set of self-contained worlds and character studies every bit as detailed and disarming as anything the 54-year-old singer-songwriter has released to date. It also includes an update to 1999’s “Let’s Move to the Country,” a song (originally under his Smog pseudonym) that was calling out for some added perspective. “I have a natural inclination to try to make a narrative out of a whole record,” he says. “But this time, it’s really just a bunch of songs that stand on their own, not really connected to the others. That\'s why I called it *Gold Record*—it’s kind of like a greatest hits record, though singles record is maybe more accurate.” Here, he takes us inside every song on the album. **Pigeons** “I noticed when I got married that I finally understood this word ‘community.’ I was always hearing it, but it never really meant anything to me. But then when I got married—and especially when I had a kid—that word became my favorite word. It meant so much. This song is just about the feeling of marriage, how it connects you to life processes, to birth and death and your neighbors. I think if you have a partner, you can\'t be the selfish person you used to be, because there\'s actually someone listening to you when you\'re being that way, so it kind of steers you into being more considerate and a more generous person. Because when someone is hearing what you\'re saying, then you are hearing what you\'re saying for the first time. That leads to being married to the world, I think.” **Another Song** “I actually wrote that song for a producer who contacted me. They were making a covers record with Emmylou Harris, and so I wrote that for her. The record never happened, so I just used it for myself. I think that one has a different feel because I got \[guitarist\] Matt Kinsey to play bass on that one song, and he has a pretty distinct and melodic kind of up-front way of playing bass.” **35** “It\'s definitely an experience that I had, where I felt like I’d read all the great books and would just be disappointed or feel alienated from any new authors that I would try to read. In your late teens and early twenties is when you read great books and you kind of take them on as if they are books about you, or books that reflect your inner world perfectly. But whenever I try to go back to those, I\'m just not interested. I look at it as a good thing: You are kind of unformed in your twenties, and then hopefully, by the time you hit 30, you are somewhat formed. I think that it\'s like you\'re getting your wings to fly. When you\'re unformed, when you\'re a fledgling person, you can\'t really express a lot. I think it\'s a good thing to have that feeling of not connecting necessarily with art, because it prompts you to work on your own.” **Protest Song** “That song is probably the oldest new song on the record. I started it ten years ago, got the idea and just never finished it. But I considered putting it on *Shepherd*, just as I considered putting it on \[2013’s\] *Dream River*. It didn\'t seem to fit either of those. It was kind of a revenge song. At the time I used to watch a lot of late-night shows, just because I was curious about what kind of music gets on there. At least at the time, it was almost invariably the worst people out there, in my opinion. So it was just kind of like a revenge fantasy, on the musicians that are performing. That accent I use is just a film noir that lives inside me.” **The Mackenzies** “When I bought my first car 30 years ago, the couple who was selling it invited me into their house and made me a cocktail. I just kind of hung out with them for a while, which was just a very pleasant and unusual thing. It was a used Dodge minivan, and he was a Dodge mechanic. I figured it was probably the safest person to buy a car from, a mechanic. They were maternal and paternal, to a complete stranger, me just coming out to their house. They also had one of those very homey houses that some people have. Some people master the art of comfort—they have the best couches and chairs and shag carpet and stuff. That\'s what stuck with me—their warmth, their instant warmth. But maybe that\'s because I was giving them a check for five grand. The song is fairly new, but those people had been in my head for a long time. I guess I always believe that if it\'s something you always think about, then that means it\'s very important—it\'s a good way to find out about what you should be writing about, if you have recurring thoughts.” **Let’s Move to the Country** “I always like playing it live, but I kind of stopped and then resurrected it a couple of years ago on tour. It seemed like there was something missing, and because of developments in my personal life, it just seemed like I should write a new chapter to the song. The original is from the perspective of someone who can\'t even say the words ‘baby’ or ‘family.’ The updated version is someone that can. It\'s sort of a mystery, and deciding if you\'re going to have a second one or not is kind of almost as big a decision as having one kid, because it could be looked at as whether or not you\'re happy having kids. I\'m totally not saying that people that only have one kid aren\'t happy having kids, but by having this second kid, you\'re definitely making some kind of deeper commitment, I think. You\'re saying, ‘Okay, I\'m willing to get deeper into this.’” **Breakfast** “I think it just started from an image I had of a woman making breakfast for her man—doing that kind of affectionate thing, but not having affection for the person. What are the dynamics of that? What\'s going on in that type of relationship? Why is she still feeding him and feeding the relationship when she\'s not happy? I was trying to explore that kind of dynamic that relationships can get into sometimes. I also find it interesting with couples: who gets up first and the way that changes sometimes, depending on what\'s going on. Who\'s getting out of bed first, and who\'s laying in bed longer?” **Cowboy** “It’s kind of nostalgic for the way TV used to be. There would be a later movie, and then later there was a late, late movie. If you were staying up to watch that, it would usually be after *The Tonight Show*. That meant something. It meant you\'re up pretty late, for whatever reason. You might be being irresponsible, or you might just be indulging yourself. Now that TV is on demand, I don\'t think anyone really watches late-night shows at night anymore—they just watch the highlights the next day. So on one level, it\'s about that loss of sense of place that TV used to give you, because it was a much more fixed thing. And that kind of correlates to watching a Western, because that\'s about a time that is also gone. I was just thinking about that, the time of your life when you can just watch a movie at two in the morning.” **Ry Cooder** “He\'s someone that I\'ve been familiar with maybe since his \[1984\] *Paris, Texas* soundtrack, but I hadn\'t really explored his records very much. Maybe three or four years ago I started digging into all of them and was really being blown away by how great so many of his records are and how different each one is and how he really uplifts and kind of puts a spotlight on international musicians. Unlike \[1986’s\] *Graceland*—where people think that Paul Simon kind of was just using those people—Ry Cooder really seems to want people to know about all this other kind of music. If you watch or read an interview with him from now, he\'s totally stoked about music and not at all jaded or bored or anything. I just thought that he deserved a ballad, a tribute. Because I think he\'s great.” **As I Wander** “I tried to make it a song about everything that I possibly could. I was trying to sum up human existence and sum up the record, even though it wasn\'t written with that intent necessarily. All the perspectives on the record are very distinct, and limited to just that narrative. But with ‘As I Wander,’ I tried to hold all narratives at the same time. Just like a great big spaghetti junction where all the highways meet up and swirl around.”

ROCK FALCON and THE LEES OF MEMORY present MOON SHOT a NICK RASKULINECZ & JOHN DAVIS production of a JOHN DAVIS BRAND MUSIC film starring BRANDON FISHER & NICK SLACK Mission Control: Rock Falcon, Nashville, TN, Music City, USA Systems Supervisor: Nathan Yarborough Remote Overdubbing Installation: Electric Church Mastering Engineer: Ted Jensen Lacquers: Wes Garland/NRP Cover Art: Stirling Snow with Mark H. Roberts Package Design: George Middlebrooks Lunar Photography: NASA Songs by John Davis except for "Drift Into A Dream" and "The Summer Sun" composed by Brandon Fisher & John Davis. © & ℗ 2020 John Davis brand Music (BMI). Administered by Words And Music, a division of Big Deal Music.