Hot Press's 50 Best Albums of 2024

Here are our top albums of the year – as voted for by the Hot Press critics...

Published: December 20, 2024 09:00

Source

Perhaps more so than any other Irish band of their generation, Fontaines D.C.’s first three albums were intrinsically linked to their homeland. Their debut, 2019’s *Dogrel*, was a bolshy, drizzle-soaked love letter to the streets of Dublin, while Brendan Behan-name-checking follow-up *A Hero’s Death* detailed the group’s on-the-road alienation and estrangement from home. And 2022’s *Skinty Fia* viewed Ireland from the complicated perspective of no longer actually being there. On their fourth album, however, Fontaines D.C. have shifted their attention elsewhere. *Romance* finds the five-piece wandering in a futuristic dystopia inspired by Japanese manga classic *Akira*, Paolo Sorrentino’s 2013 film *La Grande Bellezza*, and Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn’s *Pusher* films. “We didn’t set out to make a trilogy of albums but that’s sort of what happened,” drummer Tom Coll tells Apple Music of those first three records. “They were such a tight world, and this time we wanted to step outside of it and change it up. A big inspiration for this record was going to Tokyo for the first time. It’s such a visual, neon-filled, supermodern city. It was so inspiring. It brought in all these new visual references to the creative process for the first time.” Recorded with Arctic Monkeys producer James Ford (their previous three albums were all made with Dan Carey), *Romance* also brings in a whole new palette of sounds and colors to the band’s work. From the clanking apocalyptic dread of the opening title track, hip-hop-inspired first single “Starburster,” and the warped grunge and shoegaze hybrids of “Here’s the Thing” and “Sundowner,” it opens a whole new chapter for Fontaines D.C., while still finding time for classic indie rock anthems such as “Favourite”’s wistful volley of guitars or the Nirvana-like “Death Kink.” “Every album we do feels like a huge step in one direction for us, but *Romance* is probably a little bit more outside of our previous records,” says Coll. “It’s exciting to surprise people.” Read on as he dissects *Romance*, one track at a time. **“Romance”** “This is one that we wrote really late at night in the studio. It just fell out of us. It was one of those real moments of feeling, ‘Right, that’s the first track on the album.’ It’s kind of like a palate cleanser for everything that’s come before. It’s like the opening scene. I feel like every time we’ve done a record there’s been one tune that’s always stuck out like, ‘This is our opening gambit...’” **“Starburster”** “Grian \[Chatten, singer\] wrote most of this tune on his laptop, so there were lots of chopped-up strings and stuff—it was quite a hip-hop creative process. It’s probably the song that is furthest away from the old us on this album. This tune was the first single and we always try and shock people a bit. It’s fun to do that.” **“Here’s the Thing”** “This was written in the last hour of being in the studio. We had maybe 12 or 13 tracks ready to go and just started jamming, and it presented itself in an hour. \[Guitarist Conor\] Curley had this really gnarly, ’90s, piercing tone, and it just went from there.” **“Desire”** “This has been knocking around for ages. It was one of those tunes that took so many goes to get to where it was meant to sit. It started as a band setup and then we went really electronic with it. Then in the studio, we took it all back. It took a while for it to sit properly. Grian did 20 or 30 vocal layers on that, he really arranged it in an amazing way. Carlos \[O’Connell, guitarist\] and Grian were the main string arrangers on this record. This was the first record where we actually got a string quartet in—before, people would just send it over. So being able to sit in the room and watch a string quartet take center stage on a song was amazing.” **“In the Modern World”** “Grian wrote this song when he was in LA. He was really inspired by Lana Del Rey and stuff like that. Hollywood and the glitz and the glamour, but it’s actually this decrepit place. It’s that whole idea of faded glamour.” **“Bug”** “This felt like a really easy song for us to write. That kind of buzzy, all-of-us-in-the-same-room tune. I really fought for this one to be on the record. I feel like, with songs like that, trying to skew them and put a spin on them that they don’t need is overwriting. If it feels right then there’s no point in laboring over it. That song is what it is and it’s great. It’s going to be amazing live.” **“Motorcycle Boy”** “This one is inspired by The Smashing Pumpkins a bit. We actually recorded it six months before the rest of the album. This tune was the real genesis of the record and us finding a path and being like, ‘OK, we can explore down here...’ That was one that really set the wheels in motion for the album. It really informed where we were going.” **“Sundowner”** “On this album, we were probably coming from more singular points than we have before. A lot of the lads brought in tunes that were pretty much there. I was sharing a room with Curley in London, and he was working on this really shoegaze-inspired tune for ages. I think he always thought that Grian would sing it, but when he put down the guide vocals in the studio it sounded great. We were all like, ‘You are singing this now.’” **“Horseness Is the Whatness”** “Carlos sent me a demo of that tune ages and ages ago. It was just him on an acoustic, and it was such a powerful lyric. I think it’s amazing. We had to kind of deconstruct it and build it back up again in terms of making it fit for this record. Carlos had made three or four drum loops for me and it was a really fun experience to try and recreate that. I don’t know how we’re going to play it live but we’ll sort it out!” **“Death Kink”** “Again, this came from one of the jams of us setting up for a studio session. It’s another one of those band-in-a-room-jamming-out kind of tunes. On tour in America, we really honed where everything should sit in the set. This is going to be such a fun tune to play live. We’ve started playing it already and it’s been so sick.” **“Favourite”** “‘Favourite’ was another one we wrote when we were rehearsing. It happened pretty much as it is now. We were kind of nervous about touching it again for the album because that first recording was so good. That’s the song that hung around in our camp for the longest. When we write songs on tour, often we end up getting bored of them over time but ‘Favourite’ really stuck. We had a lot of conversations about the order on this album and I felt it was really important to move from ‘Romance’ to ‘Favourite.’ It feels like a journey from darkness into light, and finishing on ‘Favourite’ leaves it in a good spot.”

It’s no surprise that “PARTYGIRL” is the name Charli xcx adopted for the DJ nights she put on in support of *BRAT*. It’s kind of her brand anyway, but on her sixth studio album, the British pop star is reveling in the trashy, sugary glitz of the club. *BRAT* is a record that brings to life the pleasure of colorful, sticky dance floors and too-sweet alcopops lingering in the back of your mouth, fizzing with volatility, possibility, and strutting vanity (“I’ll always be the one,” she sneers deliciously on the A. G. Cook- and Cirkut-produced opening track “360”). Of course, Charli xcx—real name Charlotte Aitchison—has frequently taken pleasure in delivering both self-adoring bangers and poignant self-reflection. Take her 2022 pop-girl yet often personal concept album *CRASH*, which was preceded by the diaristic approach of her excellent lockdown album *how i’m feeling now*. But here, there’s something especially tantalizing in her directness over the intoxicating fumes of hedonism. Yes, she’s having a raucous time with her cool internet It-girl friends, but a night out also means the introspection that might come to you in the midst of a party, or the insurmountable dread of the morning after. On “So I,” for example, she misses her friend and fellow musician, the brilliant SOPHIE, and lyrically nods to the late artist’s 2017 track “It’s Okay to Cry.” Charli xcx has always been shaped and inspired by SOPHIE, and you can hear the influence of her pioneering sounds in many of the vocals and textures throughout *BRAT*. Elsewhere, she’s trying to figure out if she’s connecting with a new female friend through love or jealousy on the sharp, almost Uffie-esque “Girl, so confusing,” on which Aitchison boldly skewers the inanity of “girl’s girl” feminism. She worries she’s embarrassed herself at a party on “I might say something stupid,” wishes she wasn’t so concerned about image and fame on “Rewind,” and even wonders quite candidly about whether she wants kids on the sweet sparseness of “I think about it all the time.” In short, this is big, swaggering party music, but always with an undercurrent of honesty and heart. For too long, Charli xcx has been framed as some kind of fringe underground artist, in spite of being signed to a major label and delivering a consistent run of albums and singles in the years leading up to this record. In her *BRAT* era, whether she’s exuberant and self-obsessed or sad and introspective, Charli xcx reminds us that she’s in her own lane, thriving. Or, as she puts it on “Von dutch,” “Cult classic, but I still pop.”

Billie Eilish has always delighted in subverting expectations, but *HIT ME HARD AND SOFT* still, somehow, lands like a meteor. “This is the most ‘me’ thing I’ve ever made,” she tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “And purely me—not a character.” An especially wide-ranging and transportive project, even for her, it’s brimming with the guts and theatricality of an artist who has the world at her feet—and knows it. In a tight 45 minutes, Eilish does as she promises and hits listeners with a mix of scorching send-ups, trance excursions, and a stomping tribute to queer pleasure, alongside more soft-edged cuts like teary breakup ballads and jaunts into lounge-y jazz. But the project never feels zigzaggy thanks to, well, the Billie Eilish of it all: her glassy vocals, her knowing lyrics, her unique ability to make softness sound so huge. *HIT ME* is Eilish’s third album and, like the two previous ones, was recorded with her brother and longtime creative partner FINNEAS. In conceptualizing it, the award-winning songwriting duo were intent on creating the sort of album that makes listeners feel like they’ve been dropped into an alternate universe. As it happens, this universe has several of the same hallmarks as the one she famously drew up on her history-making debut, 2019’s *WHEN WE ALL FALL ASLEEP, WHERE DO WE GO?*. In many ways, this project feels more like that album’s sequel than 2021’s jazzy *Happier Than Ever*, which Eilish has said was recorded during a confusing, depressive pandemic haze. In the three years since, she has tried to return to herself—to go outside, hang out with friends, and talk more openly about sex and identity, all things that make her feel authentic and, for lack of a better word, normal. “As much as *Happier Than Ever* was coming from this place of, like, \'We\'re so good. This sounds so good,\' it was also not knowing at all who I was,’” she tells Apple Music. FINNEAS agrees, calling it their “identity crisis album.” But *HIT ME HARD AND SOFT* is, she says, the reverse. “The whole time we were making it, we were like, \'I don\'t know if I\'m making anything good, this might be terrible…’ But now I\'m like, \'Yeah, but I\'m comfortable in who I am now.\' I feel like I know who I am now.” As a songwriter, Eilish is still in touch with her vulnerabilities, but at 22, with a garage full of Grammys and Oscars, they aren’t as heavy. These days it’s heartache, not her own insecurities, that keeps her up at night, and the songs are juicier for it. “LUNCH,” a racy, bass-heavy banger that can’t help but hog the spotlight, finds Eilish crushing so hard on a woman that she compares the hook-up to a meal. “I’ve said it all before, but I’ll say it again/I’m interested in more than just being your friend,” she sings. The lyrics are so much more than lewd flirtations. They’re also a way of stepping back into the spotlight—older, wiser, more fully herself. Read below as Eilish and FINNEAS share the inside story behind a few standout songs. **“LUNCH”** BILLIE: “One of the verses was written after a conversation I had with a friend and they were telling me about this complete animal magnetism they were feeling. And I was like, ‘Ooh, I\'m going to pretend to be them for a second and just write...and I’m gonna throw some jokes in there.’ We took ourselves a little too seriously on *Happier Than Ever*. When you start to embrace cringe, you\'re so much happier. You have so much more fun.” **“BIRDS OF A FEATHER”** BILLIE: “This song has that ending where I just keep going—it’s the highest I\'ve ever belted in my life. I was alone in the dark, thinking, ‘You know what? I\'m going to try something.’ And I literally just kept going higher and higher. This is a girl who could not belt until I was literally 18. I couldn\'t physically do it. So I\'m so proud of that. I remember coming home and being like, ‘Mom! Listen!’” **“WILDFLOWER”** BILLIE: “To me, \[the message here is\] I\'m not asking for reassurance. I am 100% confident that you love me. That\'s not the problem. The problem is this thing that I can\'t shake. It’s a girl code song. It\'s about breaking girl code, which is one of the most challenging places. And it isn’t about cheating. It isn’t about anything even bad. It was just something I couldn’t get out of my head. And in some ways, this song helped me understand what I was feeling, like, ‘Oh, maybe this is actually affecting me more than I thought.’ I love this song for so many reasons. It\'s so tortured and overthinky.” **“THE GREATEST”** BILLIE: “To us, this is the heart of the album. It completes the whole thing. Making it was sort of a turning point. Everything went pretty well after that. It kind of woke us back up.” FINNEAS: “When you realize you\'re willing to go somewhere that someone else isn\'t, it\'s so devastating. And everybody has been in some dynamic in their life or their relationship like that. When you realize that you\'d sacrifice and wear yourself out and compromise all these things, but the person you\'re in love with won’t make those sacrifices, or isn’t in that area? To me, that\'s what that song is about. It\'s like, you don\'t even want to know how lonely this is.” **“L’AMOUR DE MA VIE”** FINNEAS: “The album is all about Billie. It\'s not a narrative album about a fictional character. But we have always loved songs within songs within songs. Here, you\'ve just listened to Billie sound so heartbroken in ‘THE GREATEST,’ and then she sings this song that\'s like the antibody to that. It’s like, ‘You know what? Fuck you anyway.’ And then she goes to the club.” **“BLUE”** “The first quarter of ‘BLUE’ is a song Finneas and I made when I was 14 called ‘True Blue.’ We played it at little clubs before I had anything out, and never \[released it\] because we aged out of it. Years went by. Then, for a time, the second album was going to include one additional song called ‘Born Blue.’ It was totally different, and it didn’t make the cut. We never thought about it again. Then, in 2022, I was doing my laundry and found out ‘True Blue’ had been leaked. At first I was like ‘Oh god, they fucking stole my shit again,’ but then I couldn\'t stop listening. I went on YouTube and typed ‘Billie Eilish True Blue’ to find all the rips of it, because I didn\'t even have the original. Then it hit us, like, ‘Ooh, you know what\'d be cool? What if we took both of these old songs, resurrected them, and made them into one?’ The string motif is the melody from the bridge of ‘THE GREATEST,’ which is also in ‘SKINNY,’ which starts the album. So it also ends the album.”

Listening to Adrianne Lenker’s music can feel like finding an old love letter in a library book: somehow both painfully direct and totally mysterious at the same time, filled with gaps in logic and narrative that only confirm how intimate the connection between writer and reader is. Made with a small group in what one imagines is a warm and secluded room, *Bright Future* captures the same folksy wonder and open-hearted intensity of Big Thief but with a slightly quieter approach, conjuring visions of creeks and twilights, dead dogs (“Real House”) and doomed relationships (“Vampire Empire”) so vivid you can feel the humidity pouring in through the screen door. She’s vulnerable enough to let her voice warble and crack and confident enough to linger there for as long as it takes to get her often devastating emotional point across. “Just when I thought I couldn’t feel more/I feel a little more,” she sings on “Free Treasure.” Believe her.

Few artists have done more for carrying the banner of guitar rock proudly into the 21st century than St. Vincent. A notorious shredder, she cut her teeth as a member of Sufjan Stevens’ touring band before releasing her debut album *Marry Me* in 2007. Since then, her reputation as a six-string samurai has been cemented in the wake of a run of critically acclaimed albums and collaborations (she co-wrote Taylor Swift’s No 1. single “Cruel Summer”). A shape-shifter of the highest order, St. Vincent, aka Annie Clark, has always put visual language on equal footing with her sonic output. Most recently, she released 2021’s *Daddy’s Home*, a conceptual period piece that pulled inspiration from ’70s soul and glam set in New York City. That project marked the end of an era visually—gone are the bleach-blonde wigs and oversized Times Square-ready trench coats—as well as creatively. With *All Born Screaming*, she bids adieu to frequent collaborator Jack Antonoff, who produced *Daddy’s Home*, and instead steps behind the boards for the first time to produce the project herself. “For me, this record was spending a lot of time alone in my studio, trying to find a new language for myself,” Clark tells Apple Music’s Hanuman Welch. “I co-produced all my other records, but this one was very much my fingerprints on every single thing. And a lot of the impetus of the record was like, ‘Okay: I\'m in the studio and everything has to start with chaos.’” For Clark, harnessing that chaos began by distilling the elemental components of what makes her sound like, well, her. Guitar players, in many respects, are some of the last musicians defined by the analog. Pedal boards, guitar strings, and pass-throughs are all manipulated to create a specific tone. It’s tactile, specialized, and at times, yes, chaotic. “What I mean by chaos,” Clark says, “is electricity actually moving through circuitry. Whether it\'s modular synths or drum machines, just playing with sound in a way that was harnessing chaos. I\'ve got six seconds of this three-hour jam, but that six seconds is lightning in a bottle and so exciting, and truly something that could only have happened once and only happened in a very tactile way. And then I wrote entire songs around that.” Those songs cover the spectrum from sludgy, teeth-vibrating offerings like “Flea” all the way to the lush album cut (and ode to late electronic producer SOPHIE) “Sweetest Fruit.” Clark relished in balancing these light and dark sounds and sentiments—and she didn’t do so alone. “I got to explore and play and paint,” she says. “And I also luckily had just great friends who came in to play on the record and brought their amazing energy to it.” *All Born Screaming* features appearances from Dave Grohl, Warpaint’s Stella Mozgawa, and Welsh artist Cate Le Bon, among others. Le Bon pulled double duty on the album by performing on the title track as well as offering clarity for some of the murkier production moments. “I was finding myself a little bit in the weeds, as everyone who self-produces does,” Clark says. “And so I just called Cate and was like, ‘I need you to just come hold my hand for a second.’ She came in and was a very stabilizing force, I think, at a time in the making of the record when I needed someone to sort of hold my hand and pat my head and give me a beer, like, ‘It\'s going to be okay.’” With *All Born Screaming*, Clark manages to capture the bloody nature of the human experience—including the uncertainty and every lightning-in-a-bottle moment—but still manages to make it hum along like a Saturday morning cartoon. “The album, to me, is a bit of a season in hell,” she says. “You are a little bit walking on your knees through some broken glass—but in a fun way, kids. We end with this sort of, ‘Yes, life is difficult, but it\'s so worth living and we\'ve got to live it. Can\'t go over it, can\'t go under it, might as well go through it.’ It\'s black and white and the colors of a fire. That, to me, is sonically what the record is.”

“We weren’t really expecting it at such a rate,” The Last Dinner Party’s guitarist and vocalist Lizzie Mayland tells Apple Music of the band’s rise, the story of which is well known by now. After forming in London in 2021, the five-piece’s effervescent live shows garnered an if-you-know-you-know kind of buzz, which went into overdrive when they released their stomping, euphoric debut single “Nothing Matters” in April 2023. All of which might have put a remarkable amount of pressure on them while making their debut record (not least given the band ended 2024 by winning the BRITs Rising Star Award then topped the BBC’s new-talent poll, Sound of 2024, in January). But The Last Dinner Party had written, recorded and finished *Prelude to Ecstasy* three months before anyone had even heard “Nothing Matters.” It meant, says lead singer Abigail Morris, that they “just had a really nice time” making it. “It is a painful record in some ways and it explores dark themes,” she adds, “but making it was just really fun, rewarding, and wholesome.” Produced by James Ford (Arctic Monkeys, Florence + the Machine, Jessie Ware), who Morris calls “the dream producer,” *Prelude to Ecstasy* is rooted in those hype-inducing live shows, its tracklist a reflection of the band’s frequent set list and its songs shaped and grown by playing them on stage. “We wanted to capture the live feels in the songs,” notes Morris. “That’s the whole point.” Featuring towering vocals, thrilling guitar solos, orchestral instrumentation, and a daring, do-it-all spirit, the album sounds like five band members having an intense amount of fun as they explore an intense set of emotions and experiences with unbridled expression and feeling. These songs—which expand and then shrink and then soar—navigate sexuality (“Sinner,” “My Lady of Mercy”), what it must be like to move through the world as a man (“Caesar on a TV Screen,” the standout, celestial “Beautiful Boy”), and craving the gaze of an audience (“Mirror”), as well as loss channeled into art, withering love, and the mother-daughter relationship. And every single one of them feels like a release. “It’s a cathartic, communal kind of freedom,” says Morris. “‘Cathartic’ is definitely the main word that we throw about when we talk about playing live and playing an album.” Read on as Morris and Mayland walk us through their band’s exquisite debut, one song at a time. **“Prelude to Ecstacy”** Abigail Morris: “I was thinking about it like an overture in a musical. Aurora \[Nishevci, keys player and vocalist\] composed it—she’s a fantastic composer, and it has themes from all the songs on the record. I don’t believe in shuffle except for playlists and I always liked the idea of \[an album\] having a start, middle, and end, and there is in this record. It sets the scene.” **“Burn Alive”** AM: “This was the first song that existed in the band—we’ve been opening the set with it the entire time. Lyrically, it always felt like a mission statement. I wrote it just after my father passed away, and it was the idea of, ‘Let me make my grief a commodity’—this kind of slightly sarcastic ‘I’m going to put my heart on the line and all my pain and everything for a buck.’ The idea of being ecstatic by being burned alive—by your pain and by your art and by your inspiration—in a kind of holy-fire way. What we’re here to do is be fully alive and committed to exorcising any demons, pain or joy.” **“Caesar on a TV Screen”** AM: “I wrote the beginning of this song over lockdown. I’d stayed over with my boyfriend at the time and then, to go back home, he lent me a suit. When I met him, I didn’t just find him attractive, I wanted to *be* him—he was also a singer in another band and he had this amazing confidence and charisma in a specifically masculine way. Getting to have his suit, I was like, ‘Now I am a man in a band.’ It’s this very specific sensuality and power you feel when you’re dressing as a man. I sat at the piano and had this character in my head—a Mick Jagger or a Caligula. I thought it would be fun to write a song from the perspective of feeling like a king, but you are only like that because you’re so vulnerable and so desperate to be loved and quite weak and afraid and childlike.” Lizzie Mayland: “There was an ending on the original version that faded away into this lone guitar, which was really beautiful, but we got used to playing it live with it coming back up again. So we put that back in. The song is very live, the way we recorded it.” **“The Feminine Urge”** AM: “The beginning of this song was based on an unreleased Lana Del Rey song called ‘Driving in Cars With Boys’—it slaps. I wanted to write about my mother and the mother wound. It’s about the relationship between mothers and daughters and how those go back over generations, and the shared traumas that come down. I think you get to a certain age as a woman where your mother suddenly becomes another woman, rather than being your mum. You turn 23 and you’re having lunch and it’s like, ‘Oh shit, we’re just two women who are living life together,’ and it’s very beautiful and very sweet and also very confronting. It’s the sudden realization of the mortality and fallibility of your mother that you don’t get when you’re a child. It’s also wondering, ‘If I have a daughter, what kind of mother would I be? Is it ethical to bring a child into a world like this? And what wound would I maybe pass on to her or not?’” **“On Your Side”** LM: “We put this and ‘Beautiful Boy’—the two slow ones—together. Again, that comes from playing live. Taking a slow moment in the set—people are already primed to pay attention rather than dancing.” AM: “The song is about a relationship breaking down and it’s nice to have that represented musically. It’s a very traditional structure, song-verse-chorus, and it’s not challenging or weird. It’s nice that the ending feels like this very beautiful decay. It’s sort of rotting, but it sounds very beautiful, but it is this death and gasping. I really like how that illustrates what the song’s about.” **“Beautiful Boy”** AM: “I come back to this as one that I’m most proud of. I wanted to say something really specific with the lyrics. It’s about a friend of mine, who’s very pretty. He’s a very beautiful boy. He went hitchhiking through Spain on his own and lost his phone and was just relying on the kindness of strangers, going on this beautiful Hemingway-esque trip. I remember being so jealous of him because I was like, ‘Well, I could never do that—as a woman I’d probably get murdered or something horrible.’ He made me think about the very specific doors that open when you are a beautiful man. You have certain privileges that women don’t get. And if you’re a beautiful woman, you have certain privileges that other people don’t get. I don’t resent him—he’s a very dear friend. Also, I think it’s important and interesting to write, as a woman, about your male relationships that aren’t romantic or sexual.” LM: “The flute was a turning point in this track. It’s such a lonely instrument, so vulnerable and so expressive. To me, this song is kind of a daydream. Like, ‘I wish life was like that, but it’s not.’ It feels like there’s a deeper sense of acceptance. It’s sweetly sad.” **“Gjuha”** AM: “We wanted to do an aria as an interlude. At first, we just started writing this thing on piano and guitar and Aurora had a saxophone. At some point, Aurora said it reminded her of an Albanian folk song. We’d been talking about her singing a song in Albanian for the album. She went away and came back with this beautiful, heart-wrenching piece. It’s about her feeling this pain and guilt of coming from a country, and a family who speak Albanian and are from Kosovo, but being raised in London and not speaking that language. She speaks about it so well.” **“Sinner”** LM: “It’s such a fun live moment because it’s kind of a turning point in the set: ‘OK, it’s party time.’ I was quite freaked out about the idea of being like, ‘This is a song about being queer.’ And I thought, ‘Are people going to get that?’ Because it’s not the most metaphorical or difficult lyrics, but it’s also not just like, ‘I like all gendered people.’ But people get it, which has been quite reassuring. It’s about belonging and about finding a safe space in yourself and your own sense of self. And marrying an older version of yourself with a current version of yourself. Playing it live and people singing it back is such a comforting feeling. I know Emily \[Roberts, lead guitarist, who also plays mandolin and flute\] was very inspired by St. Vincent and also LCD Soundsystem.” **“My Lady of Mercy”** AM: “For me, it’s the most overtly sexy song—the most obviously-about-sex song and about sexuality. I feel like it’s a nice companion to ‘Sinner’ because I think they’re about similar things—about queerness in tension with religion and with family and with guilt. I went to Catholic school, which is very informative for a young woman. I’m not a practicing Catholic now, but the imagery is always so pertinent and meaningful to me. I just thought it was really interesting to use religious imagery to talk about liking women and feeling free in your sexuality and reclaiming the guilt. I feel like Nine Inch Nails was a really big inspiration musically. This is testament to how much we trust James \[Ford\] and feel comfortable with him. We did loads of takes of me just moaning into the mic through a distortion. I could sit there and make fake orgasm sounds next to him.” LM: “I remember you saying you wanted to write a song for people to mosh to. Especially the breakdown that was always meant to be played live to a load of people throwing themselves around. It definitely had to be that big.” **“Portrait of a Dead Girl”** AM: “This song took a long time—it went through a lot of different phases. It was one we really evolved with as a band. The ending was inspired by Florence + the Machine’s ‘Dream Girl Evil.’ And Bowie’s a really big influence in general on us, but I think especially on this one. It feels very ’70s and like the Ziggy Stardust album. The portrait was actually a picture I found on Pinterest, as many songs start. It was an older portrait of a woman in a red dress sitting on a bed and then next to her is a massive wolf. At first, I thought that was the original painting, but then I looked at it again and the wolf has been put in. But I really loved that idea of comparing \[it to\] a relationship, a toxic one—feeling like you have this big wolf who’s dangerous but it’s going to protect you, and feeling safe. But you can’t be friends with a wolf. It’s going to turn around and bite you the second it gets a chance.” **”Nothing Matters”** AM: “This wasn’t going to be the first single—we always said it would be ‘Burn Alive.’ We had no idea that it was going to do what it did. We were like, ‘OK, let’s introduce ourselves,’ and then where it went is kind of beyond comprehension.” LM: “I was really freaked out—I spent the first couple of days just in my bed—but also so grateful for all the joy it’s been received with. When we played our first show after it came out, I literally had the phrase, ‘This is the best feeling in the world.’ I’ll never forget that.” AM: “It was originally just a piano-and-voice song that I wrote in my room, and then it evolved as everyone else added their parts. Songs evolve by us playing them on stage and working things out. That’s definitely what happened with this song—especially Emily’s guitar solo. It’s a very honest love song that we wanted to tell cinematically and unbridled, that expression of love without embarrassment or shame or fear, told through a lens of a very visual language—which is the most honest way that I could have written.” **“Mirror”** AM: “Alongside ‘Beautiful Boy,’ this is one of the most precious ones to me. When I first moved to London before the band, I was just playing on my own, dragging my piano around to shitty venues and begging people to listen. I wrote it when I was 17 or 18, and it’s the only one I’ve kept from that time. It’s changed meanings so many times. At first, one of them was an imagined relationship, I hadn’t really been in relationships until then and it was the idea of codependency and the feeling of not existing without this relationship. And losing your identity and having it defined by relationship in a sort of unhealthy way. Then—and I’ve never talked about this—but the ‘she’ in the verses I’m referring to is actually an old friend of mine. After my father died, she became obsessed with me and with him, and she’d do very strange, scary things like go to his grave and call me. Very frightening and stalker-y. I wrote the song being like, ‘I’m dealing with the dissolution of this friendship and this kind of horrible psychosis that she seems to be going through.’ Now this song has become similar to ‘Burn Alive.’ It’s my relationship with an audience and the feeling of always being a performer and needing someone looking at you, needing a crowd, needing someone to hear you. I will never forget the day that Emily first did that guitar solo. Then Aurora’s orchestral bit was so important to have on that record. We wanted it to have light motifs from the album. That ending always makes me really emotional. I think it’s a really touching bit of music and it feels so right for the end of this album. It feels cathartic.”

In a short time, Claire Cottrill has become one of pop music’s most fascinating chameleons. Even as her songwriting and soft vocals often possess her singular touch, the prodigious 25-year-old has exhibited a specific creative restlessness in her sonic approach. After pivoting from the lo-fi bedroom pop of her early singles to the sounds of lush, rustic 2000s indie rock on 2019’s star-making *Immunity* and making a hard pivot towards monastic folk on 2021’s *Sling*, the baroque, ’70s soul-inflected chamber-pop that makes up her third album, *Charm*, feels like yet another revelation in an increasingly essential catalog. *Charm* is Cottrill’s third consecutive turn in the studio with a producer of distinctive aesthetic; while *Immunity*’s flashes of color were provided by Rostam Batmanglij and Jack Antonoff worked the boards on *Sling*, these 11 songs possess the undeniable warmth of studio impresario and Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings founding member Leon Michels. Along with several Daptone compatriots and NYC jazz auteur Marco Benevento, Michels provides the perfect support to Cotrill’s wistful, gorgeously tumbling songcraft; woodwinds flutter across the squishy synth pads of “Slow Dance,” while “Echo” possesses an electro-acoustic hum not unlike legendary UK duo Broadcast and the simmering soul of “Juna” spirals out into miniature psychedelic curlicues. At the center of it all is Cottrill’s unbelievably intimate vocal touch, which perfectly captures and complements *Charm*’s lyrical theme of wanting desire while staring uncertainty straight in the eye.

Some people kill their nemeses with kindness; Sabrina Carpenter, the breakout pop star of summer 2024, takes the opposite tack, shooting withering one-liners at loser exes via featherlight melodies, a wink and a smile. The former Disney Channel star began her music career at age 15 with her 2014 debut single “Can’t Blame a Girl for Trying.” Now 25, the singer-songwriter is making the catchiest, funniest, and most honest music of her career at a moment when all the world’s watching. But on songs like “Please Please Please,” on which she begs her boyfriend not to embarrass her (again), she’s poking fun at herself, too. “A lot of what I really love about this album is the accountability,” she tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “I will call myself out just as much as I will call out someone else.” It’s not because Carpenter’s “vertically challenged,” as she puts it, that she named her sixth album *Short n’ Sweet*. “I thought about some of these relationships, how some of them were the shortest I’ve ever had and they affected me the most,” she tells Lowe. “And I thought about the way that I respond to situations: Sometimes it is very nice, and sometimes it’s not very nice.” Hence songs like “Dumb & Poetic,” a gentle acoustic ballad that’s also a blistering takedown of a guy who masks his sleazy tendencies with therapy buzzwords and a highbrow record collection, or the twangy, hilarious “Slim Pickins,” on which she croons: “Jesus, what’s a girl to do?/This boy doesn’t even know the difference between there, their, and they are/Yet he’s naked in my room.” With good humor and good taste (channeling Rilo Kiley here, Kacey Musgraves there, and on “Sharpest Tool,” a bit of The Postal Service), Carpenter reframes heartbreak through the lens of life’s absurdity. “When you’re at this point in your life where you’re almost at your wits’ end, everything is funny,” Carpenter tells Lowe. “So much of this album was made in the moments where there was something that I just couldn’t stop laughing about. And I was like, well, that might as well just be a whole song.” Carpenter wrote a good deal of the album on an 11-day trip to a tiny town in rural France, where the isolation unlocked her brutally honest side, resulting in unprecedentedly vulnerable music and one song she readily admits shouldn’t work on paper but hits anyway: “Espresso,” the song that catapulted her career with four delightfully strange-sounding words: “That’s that me espresso.” “There really are no rules to the things you say,” she tells Lowe on the songwriting process. “You’re just like, what sounds awesome? What feels awesome? And what gets the story across, whatever story that is?” Still, she’s painted herself in a bit of a corner when it comes to placing an order at coffee shops worldwide: “They’re just waiting for me to say it,” she laughs. “And I’m like, ‘Tea.’”

As someone who invited fame and courted infamy, first with inflammatory albums like *Wolf* and later with his flamboyant fashion sense via GOLF WANG, Tyler Okonma is less knowable than most stars in the music world. While most celebrities of his caliber and notoriety either curate their public lives to near-plasticized extremes or become defined by tabloid exploits, the erstwhile Odd Futurian chiefly shares what he cares to via his art and the occasional yet ever-quotable interview. As his Tyler, The Creator albums pivoted away from persona-building and toward personal narrative, as on the acclaimed *IGOR* and *CALL ME IF YOU GET LOST*, his mystique grew grandiose, with the undesirable side effect of greater speculation. The impact of fan fixation plays no small part on *CHROMAKOPIA*, his seventh studio album and first in more than three years. Reacting to the weirdness, opening track “St. Chroma” finds Tyler literally whispering the details of his upbringing, while lead single “Noid” more directly rages against outsiders who overstep both online and offline. As on his prior efforts, character work plays its part, particularly on “I Killed You” and the two-hander “Hey Jane.” Yet the veil between truth and fiction feels thinner than ever on family-oriented cuts like “Like Him” and “Tomorrow.” Lest things get too damn serious, Tyler provocatively leans into sexual proclivities on “Judge Judy” and “Rah Tah Tah,” both of which should satisfy those who’ve been around since the *Goblin* days. When monologue no longer suits, he calls upon others in the greater hip-hop pantheon. GloRilla, Lil Wayne, and Sexyy Red all bring their star power to “Sticky,” a bombastic number that evolves into a Young Buck interpolation. A kindred spirit, it seems, Doechii does the most on “Balloon,” amplifying Tyler’s energy with her boisterous and profane bars. Its title essentially distillable to “an abundance of color,” *CHROMAKOPIA* showcases several variants of Tyler’s artistry. Generally disinclined to cede the producer’s chair to anyone else, he and longtime studio cohort Vic Wainstein execute a musical vision that encompasses sounds as wide-ranging as jazz fusion and Zamrock. His influences worn on stylishly cuffed sleeves, Neptunes echoes ring loudly on the introspective “Darling, I” while retro R&B vibes swaddle the soapbox on “Take Your Mask Off.”

It can be dangerous, Nick Cave says, to look back on one’s body of work and seek meaning in the music you’ve made. “Most records, I couldn\'t really tell you by listening what was going on in my life at the time,” he tells Apple Music. “But the last three, they\'re very clear impressions of what life has actually been like. I was in a very strange place.” In the years following the 2015 death of his son Arthur, Cave’s work—in song; in the warm counsel of his newsletter, The Red Hand Files; in the extended conversation-turned-book he wrote with journalist Seán O’Hagan, *Faith, Hope and Carnage*—has been marked by grief, meeting unimaginable loss with more imagination still. It’s made for some of the most remarkable and moving music of his nearly 50-year career, perhaps most notably the feverish minimalism of 2019’s *Ghosteen*, which he intended to act as a kind of communique to his dead son, wherever he might be. Though Cave would lose another son, Jethro, in 2022, *Wild God* finds the 66-year-old singer-songwriter someplace new, marveling at the beauty all around him, reuniting with The Bad Seeds, who—with the exception of multi-instrumentalist songwriting foil Warren Ellis—had slowly receded from view. Once a symbol of post-punk antipathy, he is now open to the world like never before. “Maybe there is a feeling like things don\'t matter in the same way as perhaps they did before,” he says. “These terrible things happened, the world has done its worst. I feel released in some way from those sorts of feelings. *Wild God* is much more playful, joyous, vibrant. Because life is good. Life is better.” It’s an album that feels like an embrace. That much you can hear in the first seconds of “Song of the Lake,” a swirl of ascendant synths and thick, chewy bass (compliments of Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood) upon which Cave tells a tale of brokenness that never quite resolves, as though to fully heal or be put back together again has never really been the point of all this, of being human. The mood is largely improvisational and loose, Cave leaning into moments of catharsis like a man who’d been waiting for them. He offers levity (the colossal, delirious title track) and light (“Frogs,” “Final Rescue Attempt”). On “O Wow O Wow (How Wonderful She Is),” a tribute to the late Anita Lane, his former creative and romantic partner, he conjures a sense of play that would have seemed impossible a few years ago. “I think that it\'s just an immense enjoyment in playing,” he says of the band\'s influence on the album. “I think the songs just have these delirious, ecstatic surges of energy, which was a feeling in the studio when we recorded it. We\'re not taking it too seriously in a way, although it\'s a serious record. We were having a good time. I was having a really good time.” There is no shortage of heartbreak or darkness to be found here. But “Joy,” the album’s finest moment (and original namesake), is a monument to optimism, a radical thought. For six minutes, he sounds suspended in twilight, pulling words out of thin air, synths fluttering and humming and flickering around him, peals of piano and French horn coming and going like comets. “We’ve all had too much sorrow, now is the time for joy,” he sings, quoting a ghost who’s come to his bedside, a “flaming boy” in sneakers. “Joy doesn\'t necessarily mean happiness,” Cave says upon reflection. “Joy in a way is a form of suffering, in the sense that it understands the notion of suffering, and it\'s these momentary ecstatic leaps we are capable of that help us rise out of that suffering for a moment of time. It is sort of an explosion of positive feeling, and I think the record\'s full of that, full of these moments. In fact, the record itself is that.” While that may sound like a complete departure from its most recent predecessors, *Wild God* shares a similar intention, an urge to communicate with his late children, from this world to theirs. That may never fade. “If there\'s one impulse I have, it’s that I would like my kids who are no longer with us to know that we are okay, that \[wife\] Susie and I are okay,” Cave says. “I think that\'s why when I listened to the record back, I just listened to it with a great big smile on my face. Because it\'s just full of life and it\'s full of reasons to be happy. I think this record can definitely improve the condition of my children. All of the things that I create these days are an attempt to do that.” Read on as Cave takes us inside a few highlights from the album: **“Wild God”** “I was actually going to call the record *Joy*, but chose *Wild God* in the end because I thought the word ‘joy’ may be misunderstood in a way. ‘Wild God’ is just two pieces of music chopped together—an edit. That song didn\'t really work quite right. So we thought, ‘Well, let\'s get someone else to mix it.’ And me and Warren thought about that for a while. I personally really loved the sound of \[producer Dave Fridmann’s work with\] MGMT, and The Flaming Lips, stuff—it had this immediacy about it that I really liked. So we went to Buffalo with the recordings and Dave did a song each day, disappeared into the control room and mixed it without inviting us in. It was the strangest thing. And then he emerges from the studio and says, ‘Come in and tell me what you think.’ When we came in it sounded so different. We were shocked. And then after we played it again, we heard that he traded in all the intricacies and stateliness of The Bad Seeds for just pure unambiguous emotion.” **“Frogs”** “Improvising and ad-libbing is still very much the way we go about making music. ‘Frogs’ is essentially a song that I had some words to, but I just walked in and started singing over the top of this piece of music that we\'d constructed without any real understanding of the song itself. There\'s no formal construction—it just keeps going, very randomly. There\'s a sort of freedom and mystery to that stuff that I find really compelling. I sang it as a guide, but listening to it back was like, ‘Wow, I don\'t know how to go and repeat that in any way, but it feels like it\'s talking about something way beyond what the song initially had to offer.’” **“Joy”** “‘Joy’ is a wholly improvised one-take without me having any real understanding of what Warren is doing musically. It’s written in that same questing way of first takes. I\'m just singing stuff over a kind of chord pattern that he\'s got. I sort of intuit it in some way that it’s a blues form to it, so I’m attempting to sing a blues vocal over the top, rhyming in a blues tradition.” **“Final Rescue Attempt”** “That was a song that we weren\'t putting on the record. It was a late addition, just hanging around. And I think Dave Fridmann actually said, ‘Look, I\'ve mixed this song. It doesn\'t seem to be on the record. What the fuck?’ It feels a little different in a way to me. But it\'s a very beautiful song, very beautiful. And I guess it was just so simple in its way, or at least the first verse literally describes the situation that I think is actually in the book, *Faith, Hope and Carnage*, where Susie decided to come back to me after eight months or so, and rode back to my house where I was living, on a bicycle. It’s a depiction of that scene, so maybe I shied away from it for that reason. I don\'t know. But I\'m really glad.” **“O Wow O Wow (How Wonderful She Is)”** “That song is an attempt to encapsulate what Anita Lane was like, and we all loved her very much and were all shocked to the core by her death. In her early days when we were together, she was this bright, shiny, happy, laughing, flaming thing, and we were the dark, drug-addicted men that circled around her. And I wanted to just write a song that had that. She was a laughing creature, and I wanted to work out a way of expressing that. It\'s such a beautifully innocent song in a way.”

There’s a sense of optimism that comes through Vampire Weekend’s fifth album that makes it float, a sense of hope—a little worn down, a little roughed up, a little tired and in need of a shave, maybe—but hope nonetheless. “By the time you’re pushing 40, you’ve hit the end of a few roads, and you’re probably looking for something—I don’t know what to say—a little bit deeper,” Ezra Koenig tells Apple Music. “And you’re thinking about these ideas. Maybe they’re corny when you’re younger. Gratitude. Acceptance. All that stuff. And I think that’s infused in the album.” Take something like “Mary Boone,” whose worries and reflections (“We always wanted money, now the money’s not the same”) give way to an old R&B loop (Soul II Soul’s “Back to Life”). Or the way the piano runs on “Connect”—like your friend fumbling through a Gershwin tune on a busted upright in the next room—bring the song’s manic energy back to earth. Musically, they’ve never sounded more sophisticated, but they’ve also never sounded sloppier or more direct (“Prep-School Gangsters”). They’re a tuxedo with ripped Converse or a garage band with a full orchestra (“Ice Cream Piano”). And while you can trainspot the micro-references and little details of their indie-band sound (produced brilliantly by Koenig and longtime collaborator Ariel Rechtshaid), what you remember most is the big picture of their songs, which are as broad and comforting as great pop (“Classical”). “Sometimes I talk about it with the guys,” Koenig says. “We always need to have an amateur quality to really be us. There needs to be a slight awkward quality. There needs to be confidence and awkwardness at the same time.” Next to the sprawl of *Father of the Bride*, *OGWAU* (“og-wow”—try it) feels almost like a summary of the incredible 2007-2013 run that made them who they are. But they’re older now, and you can hear that, too, mostly in how playful and relaxed the album is. Listen to the jazzy bass and prime-time saxophone on “Classical” or the messy drums on “Prep-School Gangsters” (courtesy of Blood Orange’s Dev Hynes), or the way “Hope” keeps repeating itself like a school-assembly sing-along. It’s not cool music, which is of course what makes it so inimitably cool. Not that they seem to worry about that stuff anymore. “I think a huge element for that is time, which is a weird concept,” Koenig says. ”Some people call it a construct. I’ve heard it’s not real. That’s above my pay grade, but I will say, in my experience, time is great because when you’re bashing your head against the wall, trying to figure out how to use your brain to solve a problem, and when you learn how to let go a little bit, time sometimes just does its thing.” For a band that once announced themselves as the preppiest, most ambitious guys in the indie-rock room, letting go is big.

The Smile, a trio featuring Radiohead prime movers Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood along with ex-Sons of Kemet drummer Tom Skinner, sounds more like a proper band than a side project on their second album. Sure, they’re a proper band that unavoidably sounds a *lot* like Radiohead, but with some notable distinctions—much leaner arrangements, bass parts by Greenwood and Yorke with a very different character from what Radiohead bassist Colin Greenwood might have laid down, and a formal fixation on conveying tension in their melodies and rhythms. Their debut, *A Light for Attracting Attention*, was full of tight, wrenching grooves and guitar parts that sounded as though the strings were coiling into knots. This time around they head in the opposite direction, loosening up to the point that the music often feels extremely light and airy. The guitar in the first half of “Bending Hectic” is so delicate and minimal that it sounds like it could get blown away with a slight breeze, while the warm and lightly jazzy “Friend of a Friend” feels like it’s helplessly pushed and pulled along by strong, unpredictable winds. The loping rhythm and twitchy riffs in “Read the Room” are surrounded by so much negative space that it sounds eerily hollow, like Yorke is singing through the skeletal remains of a ’70s metal song. There are some surprises along the way, too. A few songs veer into floaty lullaby sections, and more than half include orchestral tangents that recall Greenwood’s film score work for Paul Thomas Anderson and Jane Campion. The most unexpected moment comes at the climax of “Bending Hectic,” which bursts into heavy grunge guitar, stomping percussion, and soaring vocals. Most anyone would have assumed Yorke and Greenwood had abandoned this type of catharsis sometime during the Clinton administration, but as it turns out they were just waiting for the right time to deploy it.

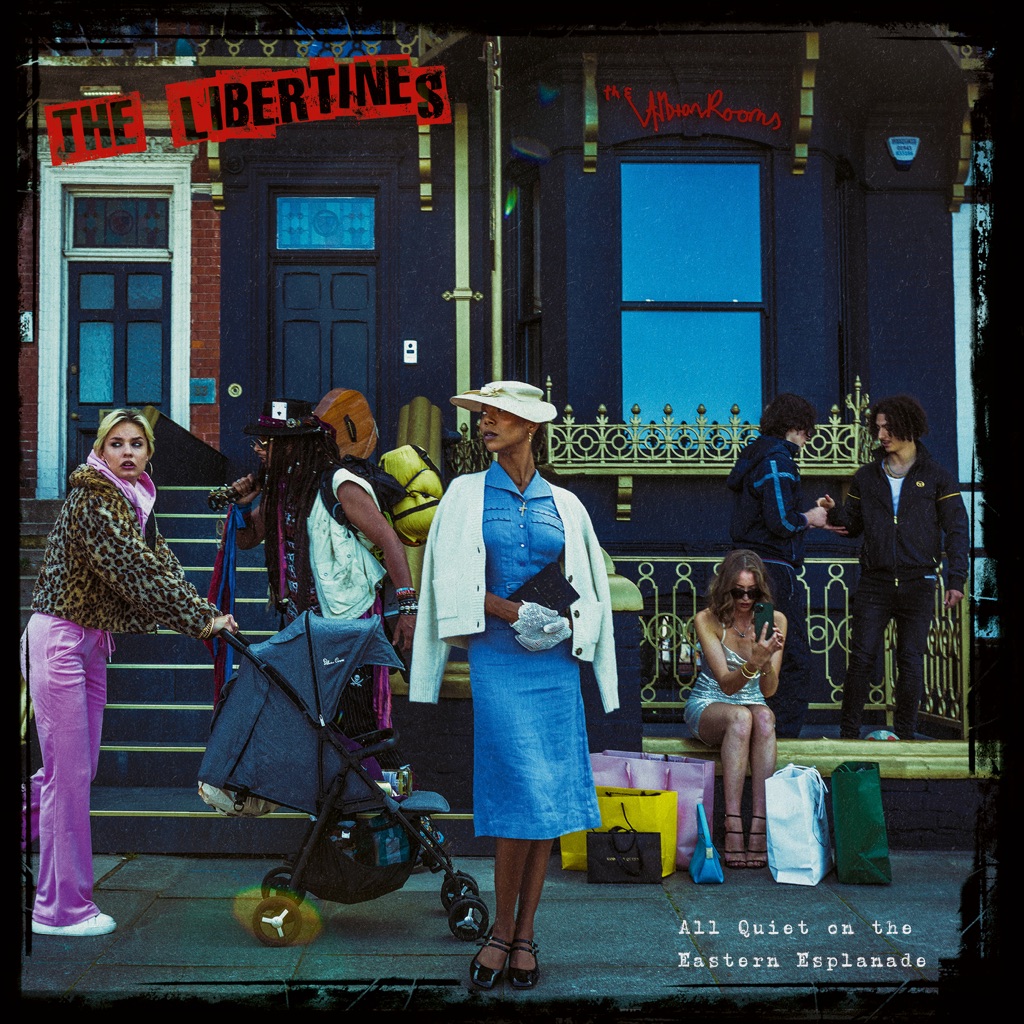

In the early 2000s, few would have bet on The Libertines making it to a fourth album album at all, let alone one as robust as *All Quiet on the Eastern Esplanade*. Intra-band strife, prison, and Pete Doherty’s well-documented drug problems seemed to have scuppered the mercurial talent shown on 2002 debut *Up the Bracket* and 2004’s self-titled follow-up for good. However, following 2015’s galvanizing reformation album, *Anthems for Doomed Youth*, *All Quiet on the Eastern Esplanade* finds the good ship Albion coming ashore with one of the strongest sets of songs of the band’s career. On an album recorded at The Albion Rooms, the group’s studio-cum-hotel in (UK seaside town) Margate, Kent, the ramshackle charm which sometimes felt like their songs could collapse at any moment has been bolstered by something far more muscular and sturdy. Rollicking opening track “Run Run Run” lands like The Clash at their anthemic peak, while closer “Songs They Never Play on the Radio” transforms a tune Doherty has been tinkering with in various forms for years into a swooning, Beatles-esque ballad. Where Libertines songs of old sprung from a mythical vision of England conjured from Doherty and fellow singer/guitarist/songwriter Carl Barât’s imagination, here they’re more rooted in the here and now. “Mustangs” is populated by a litany of colorful characters observed around Margate, Barât singing about day-drinking mums, day-dreaming nuns, and 24/7 ne’er-do-wells over a glorious Stones-y groove. While “Merry Old England” looks at a land of discarded crisp packets and B&B vouchers from the perspective of migrants traveling to the UK looking for work. “It’s a rich tapestry,” Doherty tells Apple Music. “It’s not just about Margate, it’s about England. I don’t think the English realize how the rest of the world gazes upon us with curiosity and wonder and bafflement, really.” Read on for Doherty and Barât’s track-by-track guide. **“Run Run Run”** PD: “It’s a bit of a belter that one, I love it. It’s got a bit of a Squeeze thing going on.” CB: “The song doesn’t have to be about running away from your past. It’s about running because that’s what you do. It can be in terror, or it can be a thing of great elation or purpose.” PD: “It’s just how you get your kicks, baby.” CB: “Yeah. It can be processing a trauma or getting your kicks. Either way.” **“Mustangs”** PD: “We spent an endless amount of time trying to get this together which isn’t normally our style. At one point it had 10 verses.” CB: “It was like a Velvet Underground epic. It was my \[T.S. Eliot poem\] ‘The Waste Land.’ It took a lot of shuffling in the sand to get that one to settle. It’s got a summer air to it, that kind of looseness. It’s got a Lou Reed-y narrative to it about all these characters in Margate.” **“I Have a Friend”** CB: “That’s a topical song given it’s about war and what’s going on in Ukraine.” PD: “It’s hard to look away from that. A few of us in the band have got Russian and Ukrainian roots. It was too much for me to take, we had to sit down and talk about it which merged into ‘I Have a Friend.’ It was just a desperate cry from all the darkness and confusion of all of this. I kept saying, ‘NATO are going to step in any day, are we too old to enlist?’ I said to my wife, ‘We can’t just sit here and watch it, we’ve got to go!’ She said, ’We’ve got a two-week-old baby.’” **“Merry Old England”** PD: “The people who travel here and risk life and limb to come to England and try and make a life for themselves is something we spend quite a lot of time talking about. A lot of these people are trained doctors, they speak four or five languages. It’s not that I’m pro-illegal immigration, I’ve just got this thing against borders. It’s very easy to create fear and anger and hostility about people.” CB: “It’s about discussing something that’s topical. There’s no didactic approach from us. Maybe we do have opinions, but it’s just a good song.” **“Man With the Melody”** CB: “That’s as old as time, that song.” PD: “From back when we were in Kentish Town. We didn’t have a B&B or our own recording studio or a bar. All we had was John \[Hassall, bassist\]’s basement with our little amps. He’d sit there in his skintight Dairy Queen T-shirt and his cowboy boots strumming this mad little song. We were secretly jealous of it because it was so melodic. So we took it apart, stripped it down and put it back together, put our own bits in and gave it a lick of paint. It’s got this creeping, gothic, Bram Stoker-ish element to it.” CB: “That’s Gary \[Powell, drummer\]’s singing debut. I think it’s the first time we’ve all sung on a song and shared it like that.” **“Oh Shit”** CB: “It’s essentially about the proprietor of The Albion Rooms and her husband. It’s about these young people jacking in their lives and just doing something different and worlds apart. It’s that sort of romance of the road, having no regard for their own immediate safety or life past what’s just straight in front of their faces, and being in love and all the experiences that come with that.” **“Night of the Hunter”** PD: “There’s a lot of references to tattoos. I’ve always been fascinated by that thing of ‘love’ and ‘hate’ tattooed on the knuckles. When we play it live it really slows down and I like this idea of all these people singing along to ‘ACAB’ which stands for ‘All coppers are bastards,’ which is an old skinhead tattoo. Prison is mostly full of young men, but you always get that old lag in there and they’ve got these weird tattoos and you make the mistake of asking, ‘Oh, what do those dots mean?’ Then you’re like, ‘Oh, fuck…’ You hear some really dark stuff.” **“Baron’s Claw”** PD: “That was mostly born in The Albion Rooms. We were all sleeping there and trying to put the album together. I had these chords and I was playing them and Carl’s room is directly above where I was sitting. It was six or seven in the morning and I was playing it louder and louder, just hoping that it would somehow penetrate his dreams. So I opened the window and then I was playing it on the stairs. He finally came down a bit grumpy, as he tends to be in the morning, and I thought, ‘I’ll wait for him to say something…’ And he didn’t. I waited and waited and then finally I got a little ‘So, was that a new tune, then?’ \[from him\]. Because I don’t think he believed it was.” CB: “You’re lucky. In the old days, if you were playing outside my window I would have told you to shut the fuck up.” PD: “The song’s about this quite shameful episode in our history when we \[Britain\] funded the White Russians against the Bolsheviks. This guy is over there with a unit of White Russians fighting the Red Army and then comes back without a hand. Is it based on a true story? Why not? It could have happened!” **“Shiver”** PD: “If you did a DNA test on that song it would be 23 percent me, 25 percent American bully, a bit of sausage dog, a bit of Scottish terrier, a dash of dachshund…It went on a lot of weird deviations that song.” CB: “We were in Jamaica and we wrote a really misty-eyed ballad about 25 years of friendship and going from rack and ruin and dreams and reasons for staying alive. We cut it down and used the middle eight for ‘Shiver’ and the other song got thrown on the scrapheap. That’s how decadent art can be.” PD: “It turns out with ‘Shiver’ that we’ve actually made a half-decent pop song. That song’s had more radio play in its first month than \[debut single\] ‘What a Waster’ has had in 25 years.” **“Be Young”** PD: “The message of this song was to be young and fall in love, because we were coming out with all this depressing data about the planet’s impending doom. We wrote it in Jamaica as this hurricane was crashing through the Caribbean. We just thought, ‘Well, we’ve got all this stuff in here about being born astride a grave and the world boiling in oil, so let’s throw in a chorus about just being young and in love.’” CB: “It’s difficult to write a song like that. Jim Morrison could say, ‘I just want to get my kicks before the whole shithouse goes up in flames.’ But he died in 1971, do you know what I mean? Now, you can’t have that mentality. You can’t say, ‘Just be young and fall in love.’” PD: “A lot of people do though, a lot of them just don’t give a fuck.” CB: “And more fool them.” **“Songs They Never Play on the Radio”** PD: “We got that song together years ago, at the very beginning. It’s got a checkered past. It’s like an old mate who you really believed in and you’ll always have a place for him in your heart, but he just sort of seemed to fade away. But then, it turns out he’s written the jingle for the new Audi advert and he’s sitting in a fucking mansion.” CB: “The bastard.” PD: “I took it under my wing and made it all jangly and jazzy. I could never quite do it with Babyshambles and I could never quite do it on my own, so I brought it to the table for this one. And then John said, ‘Why don’t you try it like this?’ He turned it into this Beatles thing, and it completely turned it on its head. I was aghast. We wrote another verse, gave it a lick of paint and here it is.”

For years, Childish Gambino’s *Atavista* hid in plain sight. When he released an unfinished version of the record on March 15, 2020, it spent just 12 hours on his website before he pulled it down. Reappearing on streaming a week later as *3.15.20*, the project brought up almost as many questions as sparkling neo-soul anthems, which still sounded slicker than the average as raw cuts titled after timestamps. Flash forward to 2024 and Donald Glover has upgraded and updated *3.15.20* with added tracks. He worked closely with Los Angeles producer DJ Dahi and Swedish producer and esteemed film and TV composer Ludwig Göransson, a longtime collaborator, to set a sumptuous tone seated back between the ’70s funk reverence of 2016’s *“Awaken, My Love!”* and the smooth Caribbean-inflected soul of 2014’s *Kauai*. Features from Ariana Grande, 21 Savage, and Summer Walker soar on reinvigorated mixes, while “Little Foot Big Foot” features a spotlight-ready Young Nudy, finding Gambino’s eye still fixed towards the future of the regional scene he portrayed in vivid color on FX’s *Atlanta*. *Atavista* is an ode to impermanence, never more directly than over the glimmering guitar of “Time” with Grande. (“One thing’s for certain, baby/We’re running out of time,” they harmonize on the chorus.) But in Gambino’s capable hands, *Atavista* also slows down to enjoy the view, the sonic equivalent of a luxe leather-interior BMW cruising an open California highway. “I did what I wanted to,” he revels on closing track “Final Church.” *Atavista* took many shapes over the years to reach a final form. In each warm refrain, tight sequence, and carefully chosen collaborator, Gambino demonstrates why some things are worth waiting for.

Eight albums deep into their career, Dublin rock outfit The Coronas are still as impassioned as ever, ricocheting with full hearts between romance and heartbreak on *Thoughts & Observations*. Vocalist Danny O’Reilly captains an atmospheric ship—resonant stadium rock on “Speak Up” and the exuberant “Singing Just for You (On Occasion)”; gently contemplative musings about the finer nuances of a relationship on “That’s Exactly What Love Is,” a duet with Gabrielle Aplin—drawing out the emotional core of each song through the texture of his vocal performance.

In the 18 months after Taylor Swift released *Midnights*, it often felt as though the universe had fully opened up to her. The Eras Tour was breaking records and blowing past the billion-dollar mark; its attendant concert film became the highest-grossing of all time. She generated interest and commerce and headlines everywhere she stepped foot, from tour stops to the tunnels of NFL stadiums. In 2023, she was named both *TIME* magazine’s Person of the Year and—just as iconic, tbh—Apple Music’s Artist of the Year. But do songs about that level of success speak to you? As the news broke that her highly private six-year relationship to Joe Alwyn had ended, Swifties started Swiftie-ing, quickly recirculating a clip on social media of Swift a few weeks earlier, onstage during an early Eras show, in tears as she sang “champagne problems”—a song she and Alwyn had written together. It was a reminder that, despite the superhero-like aura she now radiates, Swift, at her peak, still hurts like the rest of us. What sets her apart is her ability to sublimate that pain into pop. When she announced her 11th studio album in early 2024—while accepting another Grammy, as one does—we probably shouldn’t have been surprised. “I needed to make it,” she’d say of *THE TORTURED POETS DEPARTMENT* a few weeks later, to a crowd of—\[rubs eyes\]—96,000 in Melbourne, Australia. “I’ve never had an album where I’ve needed songwriting more than I needed it on *TORTURED POETS*.” Working again with trusted collaborators Jack Antonoff and Aaron Dessner, she returns to the soft, comfortable, bed-like sonics of *Midnights*. But the stakes feel noticeably higher here: This isn’t so much a breakup album as it is a deep-sea exploration of everything Swift has been feeling, a plunge through emotional debris. On “But Daddy I Love Him”—over strings and guitar that faintly recall her country roots—she lashes out at the crush of scrutiny and expectation she’s been subject to from the start. Naturally, catharsis comes after the chorus: “I’ll tell you something right now,” she sings. “I’d rather burn my whole life down than listen to one more second of all this bitching and moaning.” On “Florida!!!” she and Florence + the Machine team up for a pulpy escape fantasy wherein they Thelma and Louise their way down to the Sunshine State in hopes of starting over with new lives and identities: “Love left me like this,” they sing. “And I don’t want to exist.” At turns hilarious and heartbreaking, *TTPD* is a study in extremes, Swift leaning into heightened emotions with heightened, hyperbolic, ALL-CAPS language and imagery—how we think when we’re drunk on love or flattened by its sudden disappearance. Note the dark humor she weaves through the Post Malone-enriched opener “Fortnight” (“Your wife waters flowers/I wanna kill her”). Or the thrilling self-deprecation of “Down Bad,” a foray into science fiction wherein Swift likens the warmth of a relationship to being abducted by love-bombing extraterrestrials—only to be left “naked and alone, in a field in my same old town.” But this remains her most candid and unsparing work to date: As a listener, you frequently get the feeling that you’ve stumbled across emails she’d written but never sent, or into conversations you were never meant to hear. There’s a density and a specificity and a ferocity to her lyrical work here that makes 2012’s “All Too Well” feel sorta light by comparison. If you’re the kind of Swiftie who likes to live in the details, well, this one might be your Super Bowl. “You swore that you loved me, but where were the clues?” she asks on the devastating “So Long, London,” a high point. “I died on the altar waiting for the proof.” Alone at a piano on the haunting “loml,” she flips the script on someone who’d told her she was the love of their life, by telling them that they were the loss of hers: “I’ll still see it until I die.” The story, as you likely know, doesn’t end there. We get a glimpse of new beginnings in “The Alchemy” (“This happens once every few lifetimes/These chemicals hit me like white wine”) and something like triumph in the montage-ready synths of “I Can Do It With a Broken Heart,” when Swift, shattered on the floor, “as the crowd was chanting, ‘More!’,” still finds the strength to deliver: “’Cause I’m a real tough kid and I can handle my shit.” But we also get a sense of acceptance, of newfound perspective. On “Clara Bow”—named after a 1920s movie star who was able to survive the jump from silent film to sound—Swift reflects on the journey of a small-town girl made good, sung from the vantage of an industry obsessed with the next big thing. She zooms out and out and out until, in the album’s closing seconds, she’s singing about herself in the third person, in past tense, acknowledging that nothing is forever. “You look like Taylor Swift in this light, we’re loving it,” she sings. “You’ve got edge she never did/The future’s bright, dazzling.”

“My Saturn has returned,” the cosmic country singer-songwriter proclaimed to announce her fifth album (apologies to *A Very Kacey Christmas*), *Deeper Well*. If you’re reading this, odds are you know what that means: About every 30 years, the sixth planet from the sun comes back to the place in the sky where it was when you were born, and with it, ostensibly, comes growth. At 35, the chill princess of rule-breaking country/pop/what-have-you has caught up with Saturn and taken its lessons to heart. OUT: energy vampires, self-sabotaging habits, surface-level conversations. IN: jade stones, moon baths, long dinners with friends, listening closely to the whispered messages of the cosmos. (As for the wake-and-bake sessions she mentions on the title track—out, but wistfully so.) Musgraves followed her 2018 breakthrough album, the gently trippy *Golden Hour*, with 2021’s *star-crossed*, a divorce album billed as a “tragedy in three parts,” where electronic flourishes added to the drama. On *Deeper Well*, the songwriter’s feet are firmly planted on the ground, reflected in its warm, wooden, organic instrumentation—fingerpicked acoustic guitar, banjo, pedal steel. Here, Musgraves turns to nature for the answers to her ever-probing questions. “Heart of the Woods,” a campfire sing-along inspired by mycologist Paul Stamets and his *Fantastic Fungi* documentary, looks to mushroom networks beneath the forest floor for lessons on connectivity. And on “Cardinal,” a gorgeous ode to her late friend and mentor John Prine in the paisley mode of The Mamas & The Papas, potential dispatches from the beyond arrive as a bird outside her window in the morning. As Musgraves’ trust in herself and the universe deepens, so do her songwriting chops. On “Dinner With Friends,” a gratitude journal entry given the cosmic country treatment, she honors her roots in perfectly sly Musgravian fashion: “My home state of Texas, the sky there, the horses and dogs, but none of their laws.” And on the simple, searching “The Architect,” she condenses the big mysteries of human nature into one elegant, good-natured question: “Can I pray it away, am I shapeable clay/Or is this as good as it gets?”

LA-based alt-pop quartet The Marías explore pain, isolation, and the strength it takes to get better on their 2024 LP *Submarine*. The album, which follows their 2021 breakthrough debut *CINEMA*, finds the band expanding their sound to include underground dance music, disco, jazz, and more—all while pursuing melodic gold thanks to singer María Zardoya. Take the album’s second track, “Hamptons,” which blends garage drum grooves with whimsical synths and a textural tension that recalls trip-hop pioneers Portishead. Or, on “Real Life,” the group conjures up lounge jazz, managing to practically capture the heavy smoke that often fills those ambiance-heavy rooms. It’s sleek and sexy, a glowing encapsulation of the band’s mission to achieve mood with subtly complex compositions. On “Paranoia,” many of the album’s lyrical themes cohere. Zardoya takes aim at an untrusting lover, illustrating how a communication breakdown can result in total isolation: “Why do you think I have another/When you have always been the one/Your paranoia is annoying/Now all I wanna do is run away.”