Exclaim!'s Top 10 Folk and Country Albums of 2018

Today (December 6), Exclaim! presents the best folk and country albums of 2018 as part of our Best of 2018 coverage.

Did Kacey Musgraves...

Published: December 06, 2018 14:00

Source

*“Excited for you to sit back and experience *Golden Hour* in a whole new, sonically revolutionized way,” Kacey Musgraves tells Apple Music. “You’re going to hear how I wanted you to hear it in my head. Every layer. Every nuance. Surrounding you.”* Since emerging in 2013 as a slyly progressive lyricist, Kacey Musgraves has slipped radical ideas into traditional arrangements palatable enough for Nashville\'s old guard and prudently changed country music\'s narrative. On *Golden Hour*, she continues to broaden the genre\'s horizons by deftly incorporating unfamiliar sounds—Bee Gees-inspired disco flourish (“High Horse”), pulsating drums, and synth-pop shimmer (“Velvet Elvis”)—into songs that could still shine on country radio. Those details are taken to a whole new level in Spatial Audio with Dolby Atmos. Most endearing, perhaps, is “Oh, What a World,” her free-spirited ode to the magic of humankind that was written in the glow of an acid trip. It’s all so graceful and low-key that even the toughest country purists will find themselves swaying along.

Album page: www.paradiseofbachelors.com/shop/pob-041 Artist pages: www.paradiseofbachelors.com/jennifer-castle/ Other options: lnk.to/PoB41 ALBUM ABSTRACT: A sublime meditation on mortality and memory, ghosts and grief, Angels of Death casts a series of spells against forgetting and finality, in the form of mystic-minimalist country-soul torch songs about writing, time travel, and spectral visitations. Castle wrote and recorded this breathtaking follow-up to the acclaimed Pink City (2014) in a 19th century church near the shores of Lake Erie, where her family also lived and experienced a constellation of losses that inhabit these bruised musings. ALBUM NARRATIVE: The fictional concept of death rears its head in so many of my songs, always on the periphery, or as a side note, or a reminder, a punchline or the bottom line, always sniffing around like a death dog. For once I wanted to try to put it in my center vision. In order to talk about death, I armed myself with the only antidote I know: writing. Is this a record about death or a record about writing? Hard to tell in the end. I began to think of poetry as time travel. I tried to write messages to the future. – Jennifer Castle Among the surviving songs by ancient Greek poet Sappho (630–570 BCE), sometimes known to her contemporaries as the “Tenth Muse,” is a quiet, confident prayer for immortality through writing: “The Muses have filled my life/With delight/And when I die I shall not be forgotten.” The alternative is this terrible curse of oblivion: “When you lie dead, no one will remember you/For you have no share in the Muses’ roses.” Though often portrayed today as heavy-lidded, passive conduits of creativity, the Muses of Greek mythology were much stranger and more sinister creatures than their iterations in contemporary culture. In his Metamorphoses, Oviddepicts them as a species of weird angels, airborne and arboreal: “The Muse was speaking: wings sounded in the air, and voices came out of the high branches.” On Jennifer Castle’s new album Angels of Death, her third full-length record under her given name (previous releases were credited to Castlemusic), the Ontario songwriter summons a kindred classical vision of the Muses as domestic familiars intimately in league with death. In “Rose Waterfalls,” which boasts a melody that cascades like its title, muses stage a home invasion, a pestilence of inspiration. “No one said that poetry was easy,” Castle allows at the outset, but muses leave me while i make my coffee and muses don’t come watching in the bath and muses if you ever catch me in the news you can kill me muses any way you choose A sublime meditation on mortality and memory, ghosts and grief, Angels of Death casts a series of spells against forgetting and finality, in the form of mystic-minimalist country-soul torch songs about writing, time travel, and spectral visitations. Castle wrote and recorded this breathtaking follow-up to the acclaimed Pink City (2014) in a 19th century church near the shores of Lake Erie, where her family also lived and experienced a constellation of losses, struggles, and hard-won growth. The residue of those changes inhabits these bruised musings. We have, all of us, survived these types of ordinary interpersonal traumas, but they are no less devastating or meaningful for their universality. (As Joan Didion writes in her 2005 treatise on grief, The Year of Magical Thinking, “Life changes in the instant. The ordinary instant.”) The title track finds Castle wrestling, like Jacob, with the radiant angels of death “hanging in the room,” while she attempts to navigate, or write, her way through the “loopholes and catacombs of time”—the line is borrowed, with permission, from fellow Canadian poet Al Purdy—like Ariadne in the labyrinth, with her spool of silver thread. The idea, Castle explains, is that “we might resurface, in various forms, to join forces with the living, and that the living can in turn conjure the energies of the dead.” “Stars of Milk” poses the question of how to discern such otherworldly transmissions: can you hear me calling from underneath the fountain does my voice sound like nothing more than water pushing upwards Real-life muses haunt Angels of Death as well. In addition to Al Purdy, whose verse appears as a result of an invitation from Jason Collett of Broken Social Scene to incorporate a Purdy poem, Castle cites Cuban American artist Ana Mendieta, Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, and Spanish artist Susana Salinas (the addressee of “Stars of Milk”) among those whose work served as catalysts. Castle speaks of manifesting phenomena and people by writing them, or singing them, into existence. That is, I suppose, one definition of a spell—“the majesty of turning/flesh into the storyline,” as she sings in “Grim Reaper,” or vice versa. Magical and psychic manifestations aside, the album is grounded by workaday circumstances and poignant personal details, like this miniature stanza-story from the gently galloping, melodically intoxicating “Texas”: i go down to texas to kiss my grandmother goodbye she forgets things but when i look her in the eye i see my father and he’s been gone so very long in the name of time travel help him to hear my little song The Grim Reaper harvests, and the benevolent Angels remain to comfort with their small gifts of grief, which magnify beauty and pain alike. “And they whip me/with the belt of Orion,” Jennifer jokes, “when they find out/I’m not a young American.” The thesis of the album is the brittle, beautiful piano ballad “Tomorrow’s Mourning,” a skeletal song about “passing through/the ever omnipresent song” of death that surrounds us, and “singing along/’cause there’s no way out.” “You’re either the one gone, or death’s witness,” Castle observes. She wept while recording it, the first time that had ever happened, she says. The arrangements of these remarkable recordings hang in the air like the angels they describe, hovering aloft on pedal steel, strings, and keys. Sonically, songs like “Crying Shame” and “Grim Reaper,” in their disciplined atomization of chords and carefully chosen words, are refined to the point of being barely there. Space is sculpted in silence, and the songs resemble gossamer webs, visible only at an angle, sunlight refracting through dew. Castle’s voice is an instrument of exquisite ethereality and expressive linearity, limpid and narrow and pure as a mountain brook. Over the course of her fruitful career in music, she has collaborated with U.S. Girls, Owen Pallett, Doug Paisley, Fucked Up, and Kath Bloom; she has toured with Destroyer, Steve Gunn, Cass McCombs, Kurt Vile, Iron & Wine, and M. Ward, among others. Daniel Romano has even recorded a song called “Jennifer Castle.” But never before has she sounded so certain of her uncertainty, or so possessed by the urgency of her explorations. Angels of Death was produced by Castle and longtime collaborator Jeff McMurrich. Although augmented by notable other players at subsequent sessions, the core band comprised Paul Mortimer on lead guitar, David Clarke on acoustic guitar, Jonathan Adjemian on organ/piano, Mike Smith on bass (he also wrote the string arrangements), Robbie Gordon on drums, and Castle on guitar and vocals. Much of it, and most of Jennifer’s vocal tracks, were recorded live in the church over one cold weekend; “the moon,” Castle reflects, “was a member of the band.” Each side of the LP ends with a reprise of a 2008 song entitled “We Always Change,” a bit of wordplay, since “reprise” means a repetition or iteration. And so the record ends with metamorphoses—sequential transformations into a tree, the sea, a flame—much as it began with an enveloping presence neither fog, nor mist, nor cloud (“but you get the gist.”) Indeed, we always change. There’s no way out. We’re just passing through the ever omnipresent song. So let us, each of us, take our share in the Muses’ roses before we depart. Sappho knows. + Deluxe 140g virgin vinyl LP features heavy-duty high-gloss board jacket, color inner sleeve with lyrics, color LP labels, and high-res Bandcamp download code. + CD edition features high-gloss gatefold jacket with LP replica artwork. + RIYL: The Weather Station, Itasca, Steve Gunn, Aldous Harding, Joan Shelley, Cass McCombs, U.S. Girls, Meg Baird, Bill Callahan, Julie Byrne, Nadia Reid, Joanna Newsom, Angel Olsen, Mary Margaret O’Hara, Linda Perhacs, Judee Sill, Sibylle Baier, Vashti Bunyan, Kath Bloom, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, Felt. Other additional purchase options (physical/download/streaming): smarturl.it/PoB41

Haley Heynderickx - Vocals, Acoustic & Electric Guitar Lily Breshears - Electric Bass, Piano, Backing Vocals Tim Sweeney - Upright Bass, Electric Bass Phillip Rogers - Drums & Percussion, Backing Vocals Denzel Mendoza - Trombone, Backing Vocals All songs written by Haley Heynderickx Produced by Zak Kimball Co-produced by Haley Heynderickx Engineered & Mixed by Zak Kimball at Nomah Studios in Portland, Oregon Mastered by Timothy Stollenwerk at Stereophonic Mastering in Portland, Oregon Vinyl cut by Adam Gonsalves at Telegraph Mastering in Portland, Oregon Cover Photo by Alessandra Leimer Design by Vincent Bancheri

Phil Elverum’s 2017 album as Mount Eerie (*A Crow Looked at Me*) broke new ground for confessionalism, detailing the sickness and death of his wife, Geneviève, with a directness and specificity that felt at once heartbreaking and borderline artless—the chaos of real life, arranged in simple folk song. *Now Only* dips further into Elverum’s stream of consciousness, reflecting on everything from Jack Kerouac and the weight of paternity (“Distortion”) to an evening on Skrillex’s tour bus (“Now Only”) and the triangulation of grief through art (“Two Paintings by Nikolai Astrup”).

WRITTEN AND RECORDED between March 14th and October 9th, 2017 at home in the same room ORDER A PHYSICAL COPY HERE: www.pwelverumandsun.com P.W. ELVERUM & SUN box 1561 Anacortes, Wash. U.S.A. 98221 PRESS RELEASE: Now Only, written shortly following the release of A Crow Looked At Me and the first live performances of those songs, is a deeper exploration of that style of candid, undisguised lyrical writing. It portrays Elverum’s continuing immersion in the strange reality of Geneviève’s death, chronicling the evolution of his relationship to her and her memory, and of the effect the artistic exploration of his grief has had on his own life. The scope of Now Only encompasses not only hospitals and deathbeds, but also a music festival, childhood memories of conversations with Elverum’s mother, profound paintings and affecting artworks he encounters, a documentary about Jack Kerouac, and most significantly, memories of his life with Geneviève. These moments and thoughts resonate with each other, creating a more complex and nuanced picture of mourning and healing. The power of these songs comes not from the small, sharp moments of cutting phrases or shocks, but the echoes that weave the songs together, the way a life is woven. The music, fully realized by Elverum alone at home, is fleshed out texturally and seems to react to the words in real time. In a moment of confusion, dissonance abruptly makes itself known; in a moment of clarity, gentle piano arises. On the title track, the blunt declaration of “people get cancer and die” is subverted by a melody that can only be described as pop. As Elverum reinvents his lyrical process, he is also refining his musical vocabulary. Elverum’s life during the period he wrote Now Only was defined by the duality of existing with the praise and attention garnered by A Crow Looked At Me and the difficult reality of maintaining a house with a small child by himself, as well as working to preserve Geneviève’s artistic legacy. Consumed with the day to day of raising his daughter, Elverum felt his musical self was so distant that it seemed fictional. Stepping into the role of Phil Elverum of Mount Eerie held the promise of positive empathy and praise, but also the difficulty of inhabiting the intense grief that produced the music. These moments, both public and domestic, are chronicled in these songs. They are songs of remembrance, and songs about the idea of remembrance, about living on the cusp of the past and present and reluctantly witnessing a beloved person’s history take shape. Time continues.

New Zealand’s Marlon Williams has quite simply got one of the most extraordinary, effortlessly distinctive voices of his generation—a fact well known to fans of his first, self-titled solo album, and his captivating live shows. An otherworldly instrument with an affecting vibrato, it’s a voice that’s earned repeated comparisons to the great Roy Orbison, and even briefly had Williams, in his youth, consider a career in classical singing, before realizing his temperament was more Stratocaster than Stradivarius. But it’s the art of songwriting that has bedeviled the artist, and into which he has grown exponentially on his second album, Make Way For Love, out in February of 2018. It’s Marlon Williams like you’ve never heard him before—exploring new musical terrain and revealing himself in an unprecedented way, in the wake of a fractured relationship. Like any good New Zealander, Williams doesn’t boast or sugarcoat: songwriting is still not his favorite endeavor. “I mean, I find it ecstatic to finish a song,” he explains. “To have done one doesn’t feel like an accomplishment as much as a relief and maybe a curiosity, you know? To have come through to the other side and have something. But it certainly always feels messy.” In the past, his default approach to was storytelling. On 2015’s Marlon Williams, the musician took a cue from traditional folk and bluegrass, and wove dark, character-driven tales: “Hello Miss Lonesome”, “Strange Things” and “Dark Child”. But when it came to sharing his own life in song, he was more reticent. “I’ve always had this sort of hang up about putting too much of myself into my music,” he admits. “All of the projects I’ve ever been in, there was a conscientious effort to try and have this barrier between myself and the emotional crux of the music. I’ve loved writing characters into my songs, or at least pretending that it wasn’t me that it was about.” Sensing that people wanted more Marlon from Marlon, on album number two he was determined to deliver. And while he’s still a firm believer in the art of cover songs—his live shows regularly feature covers of songs by artists ranging from Townes Van Zandt to Yoko Ono—Williams wanted the new record to be all original material. By the autumn of last year, with a recording deadline looming the following February, it was crunch time for the musician, a reflexive procrastinator. “I hadn’t written for two years!” he recalls. What was needed was a lyrical spark. A triggering event, perhaps. As it turns out, life delivered just that. In early December, Williams and his longtime girlfriend, musician Aldous (Hannah) Harding, broke up—the end of a relationship that brought together two of Down Under’s most acclaimed talents of recent years, who’d managed to navigate the challenges of having equally ascendant—though separate—careers, until they couldn’t. While personally wrenching, the split seemed to open the floodgates for Williams as a writer. “Then I wrote about fifteen songs in a month,” he recalls. The biggest challenge? Condensing often complex, conflicted emotions and doing them justice. “Just narrowing the possibilities into a three-minute song makes me feel dirty”, he explains. Also, not making a breakup record that was too much of a downer. “I had a lot of good friends saying, ‘Don’t worry about sounding too sad,’” he says. “They were saying, ‘Just go with it.’” Sure enough, while Make Way For Love draws on Williams’ own story, in remarkably universal terms it captures the vagaries of relationships that we’ve all been through: the bliss (opener “Come To Me”); ache (“Love Is a Terrible Thing”, a ballad that likens post-breakup emptiness to “a snowman melting in the spring”); nagging questions (“Can I Call You”, which wonders aloud what his ex is drinking, who she’s with, and if she’s happy); and bitterness (“The Fire Of Love”, whose lyrics Williams says he “agonized over” more than any). On “Party Boy”, over an urgent, moody gallop that recalls his last album’s “Hello Miss Lonesome”, Williams conjures the image (a composite of people he knows, he says) of that guy who has just the stuff to keep the party going ‘til dawn, and who you might catch “sniffin’ around” your “pride and joy.” There’s “Beautiful Dress”, on which Williams seems to channel balladeer Elvis on the verse and the Future Feminist herself, Ahnoni, on a lilting, tremulous hook; in contrast, the brooding “I Didn’t Make A Plan”, casts Williams as the cad. In a deep-voiced delivery akin to Leonard Cohen—unusual for the singer—he callously, matter-of-factly tosses a lover aside, just cuz. It’s brutal, but so, sometimes, is life. And there’s “Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore”, a duet with Harding, recorded after the two broke up, with Williams directing Harding’s recording via a late-night long distance phone call. “It made the most sense to have her singing on it,” he says. “But it wasn’t that easy to make that happen.” Williams flipped the script recording-wise as well. After three weeks of pre-production five doors from his mother’s house in his native Lyttelton, New Zealand (for several years, Williams has made his home in Melbourne) with regular collaborator Ben Edwards—“really the only person I’d ever worked with before”—Williams and his backing band, The Yarra Benders, then decamped 7000 miles away, to Northern California’s Panoramic Studios, to record with producer Noah Georgeson, who’s helmed baroque pop and alt-folk gems by Joanna Newsom, Adam Green, Little Joy and Devendra Banhart. “I was a really big fan of those Cate Le Bon records he did [Mug Museum, Crab Day],” Williams says. “I was obsessed with those albums.” If the idea in going so far from home to make the new record was to shake things up and get out of his Kiwi comfort zone, Williams succeeded—to the point where at first he wondered if he’d gone too far. “The first couple of days I nearly had a breakdown,” he recalls. “Just cause I got there and I’m working with Noah on this really personal record having only met twice before over a coffee. I was like, ‘I wish we’d talked about it a little bit more’ and figured out exactly how the dynamic was going to work.” Williams is a worrier. But he needn’t worry. He and Georgeson settled into a zone over twelve days of recording, helped by the bonding experience of what Williams describes as the “greatest prank of all time”, with Georgeson convincing both Williams and multi-instrumentalist Dave Khan that there was a ghost in the studio, using an effect on his keyboard. Georgeson made his mark on the record as well, adding a fresh perspective on songs that had been well developed in pre-production, and alongside the incredible performances by The Yarra Benders, they have, in Make Way For Love, a triumph on their hands. The record also moves Williams several paces away from “country”—the genre that’s been affixed to him more than any in recent years, but one that’s always been a bit too reductive to be wholly accurate. Going back to his high school years band The Unfaithful Ways and his subsequent Sad But True series of collaborations with fellow New Zealander Delaney Davidson, and on through his first solo LP, Williams has proven himself plenty adept with country sounds, but also bluegrass, folk, blues and even retro pop. “I think I’ve always been sort of mischievously passive when people use that term [“country”] to describe me,” he says. “I like letting labels be and sort of just play that out.” Make Way For Love, with forays into cinematic strings, reverb, rollicking guitar and at least one quiet piano ballad, is more expansive—while still retaining, on “Party Boy” and “I Know A Jeweller”, some cowboy vibes, the record will likely invoke as many Scott Walker and Ennio Morricone mentions as it does country ones. “I think just having the time,” he explains, “and having just finished a cycle of playing these quite heavily country-leaning songs for the last three or four years, and playing them a lot, has definitely pushed me into exploring other things. As ever, you can expect some memorable videos with the new album. As reluctant as he’s been to put his lyrical heart on his sleeve in the past, Williams has never been shy about visuals and the more performative aspects of his art. Unlike many of his folk and alt-country brethren, Williams embraces the chameleonic possibilities offered by music videos. Since The Unfaithful Ways, he’s appeared in nearly all of his videos, assuming a variety of characters—multiple ones, in the Roshomon-like “Dark Child.” He’s gotten naked and visceral, in “Hello Miss Lonesome” and loose and playful in this past summer’s one-off, “Vampire Again”, which saw Williams as a goofy Nosferatu—his most lighthearted persona to date. “For me, I think that ambiguity is such an important part of my process and my art,” he explains, “that [videos are] just another way to further muddy the waters, you know? And I look for that, I think.” He’ll further muddy the waters with a new video for opening single “Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore”, directed by Ben Kitnick, in which Williams plays an overwhelmed waiter at a restaurant full of demanding hipsters. On the live front, Williams—who’s been a road dog in recent years, touring with Justin Townes Earle, Band Of Horses, City & Colour and Iron & Wine’s Sam Beam —had a comparatively low-key 2017, though appearances at Newport Folk Festival, Pickathon and Into The Great Wide Open kept him in game shape, not to mention February support dates in New Zealand for none other than Bruce Springsteen. In 2018, Williams will head out on a 50 plus date world tour, taking the music of Make Way For Love far and wide. They’re songs that need to be heard by anyone who’s ever loved, and lost, and loved again. If “breakup record” is a trope—and certainly it is—then Marlon Williams has done it proud. Like the best of the lot—Beck’s Sea Change, Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago, Phosphorescent’s harrowing “Song For Zula” and Joni Mitchell’s masterpiece Blue (written perhaps not coincidentally, following her own breakup with another gifted musician) Make Way For Love doesn’t shy away from heartbreak, but rather stares it in the face, and mines beauty from it. Delicate and bold, tender and searing, it’s a mightily personal new step for the Kiwi, and ultimately, on the record’s final, title track, Williams dusts himself off and is ready to move forward. Set to a doo-wop backdrop and in language he calls “deliberately archaic”, that superb voice sings: “Here is the will/ Here is the way/ The way into love/ Oh, let the wonder of the ages/ Be revealed as love.” John Norris October 2017

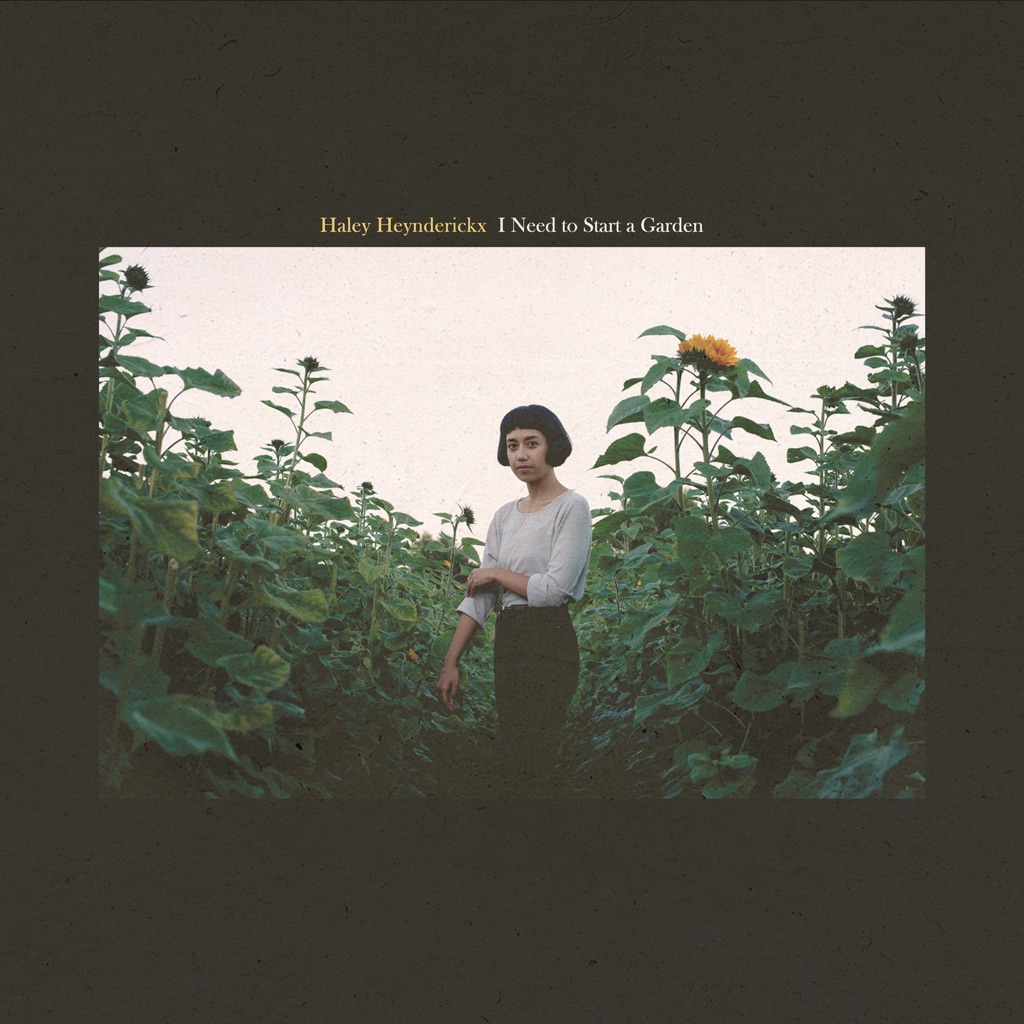

Neko Case’s ‘Hell-On,’ an indelible collection of colorful, enigmatic storytelling that features some of her most daring, through-composed arrangements to date, is available now. Produced by Neko Case, ‘Hell-On’ is simultaneously her most accessible and most challenging album, in a rich and varied career that’s offered plenty of both. ‘Hell-On’ is rife with withering self-critique, muted reflection, anthemic affirmation and Neko’s unique poetic sensibility. Neko enlisted Bjorn Yttling of (Peter Bjorn & John) to co-produce 6 tracks with her in Stockholm, Sweden where she mixed the 12 track album with Lasse Martin. ‘Hell-On’ features performances by Beth Ditto, Mark Lanegan, k.d. Lang, AC Newman, Eric Bachmann, Kelly Hogan, Doug Gillard, Laura Veirs, Joey Burns and many more.