Classic Rock's 50 Best Rock Albums of 2024

If one thing can be said with any certainty about this year, it's that – once again – rock did not die. Instead, it did what it always does. It flourished, it cropped up in unexpected places, and it k

Published: December 13, 2024 08:46

Source

“We made this record in two and a half weeks,” Black Crowes singer Chris Robinson tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “People always go, ‘Whoa, you must\'ve been really nervous, you haven\'t made a Black Crowes record in a hundred years.’ We\'re in here to get it. We\'ve done everything that we\'ve done because it feels good.” The Black Crowes never slunk from excess, from the kind of glorious hyperbole that fortified the popular arrival of their anachronistic Southern rock strut at the exact moment grunge dominated the mainstream. There was, of course, the famous and relentless feud between Chris and Rich Robinson, respectively flamboyant and pensive brothers who evoked opposite sides of the same acid sheet. All of that jibed with records of extravagant indulgence—hour-long major-label escapades that declared freaks and priests belonged in the same congregation whether it was Saturday night or Sunday morning. The Black Crowes didn’t just want to sound rock ’n’ roll; they wanted to live its dichotomies, vainglories, and sagas, too. But after a 15-year stalemate that included an eight-year break without speaking, the Robinsons reconciled and have returned with an efficient and charged 37-minute album, *Happiness Bastards*, that posits the two have moved beyond mere rapprochement. These 10 songs alternately ferry the pomp, grit, sneer, and swagger that made The Black Crowes interesting nearly 35 years ago, without the theatrics that always suggested they were actually trying twice as hard. Opener “Bedside Manners” finds Chris strutting around Rich’s sharp little riff like some lost ’70s rock god, dismissing a wanton lover one last time. With the help of stylistic descendant Lainey Wilson, they glide across and through the acoustic beauty of “Wilted Rose” like The Doobie Brothers dosed on both gospel and doom. And “Flesh Wound”—one of the sharpest and most surprising songs in their entire catalog, somewhere between Tom Petty sparkle and J. Geils Band verve—is the sort of song you want playing as you hit the road, leaving a love affair that only ever let you down. In the context of The Black Crowes’ contentious past, it’s tempting to hear that and the other kiss-offs on *Happiness Bastards* as potential relics of a more fraught moment in the Family Robinson. Or when Chris sings “Tomorrow owes nothing to the past” early in the swaying closer “Kindred Friend,” a mea culpa for lost time, it’s easy to hear a fraternal apology. The Black Crowes, though, resonated the first time around not just because they supplied unabashed retro chic in spades but because they implied that classic rock done well had something timeless to offer. Arguably the least fussy and most focused record this long-wayward band has ever made, *Happiness Bastards* reinforces that idea and The Black Crowes’ place within it.

Nineteen albums into their genre-defining career, heavy metal gods Judas Priest are still on top. *Invincible Shield* continues in the anthemic, fan-friendly tradition of 2018’s *Firepower* with songs inspired by internet-induced rage (“Panic Attack”), political charlatans (“Devil in Disguise”), and the Salem witch trials (“Trial by Fire”), among many other topics. “As the metal messenger of Priest, I\'m always looking for opportunities to touch on subjects and ideas that I haven\'t done before,” vocalist Rob Halford tells Apple Music. “You’re searching for something fresh, something new. It’s the same with all of us in Priest. I think this is so important in music—to be interesting, engaging, and entertaining. I think Priest have been doing that for 50 years. Otherwise, we\'d have been dissipated many decades ago.” Below, he comments on each song on *Invincible Shield*, plus the three bonus tracks included in the deluxe edition. **“Panic Attack”** “When you talk about topics and subjects and ideas and so forth, it\'s all been done. Let\'s face it. Whenever I do a title for a song, I search it, because I hate doing things that have been done before. But ‘Panic Attack,’ I just love that phrase. I used to have panic attacks before I got sober, and they’re very debilitating. In this case, it’s someone reacting to something they’ve seen on the internet.” **“The Serpent and the King”** “The devil is the serpent, and the king is God. Is the devil a deity? I don’t know. But I think the serpent came to me first, and then naturally my mind went to the king. And then I always try to use at least one word in a Priest album that I\'ve never used before, like ‘sulfur.’ We know what sulfur is, we know what it smells like. So, we’ve got the devil and God in conflict. Good and evil, positive and negative, black and white. It’s a constant battle.” **“Invincible Shield”** “This is resilience, determination, protection. As I was sitting there with a blank piece of paper and pencil, what came into my head was the invincibility of who we are as people in all aspects of life and living, and the shield that we defend ourselves with. It’s about standing up for yourself within our world of heavy metal.” **“Devil in Disguise”** “I\'m a news hound. Like most old people, you start to engage in politics more as you age. When you\'re a younger person, for the most part, you don\'t give a fuck about politics. But as you get older, you start thinking, \'Why do I want to do an Elvis—pull out my gun and shoot the TV?\' So, this song came from just thinking about the political spectrum, but also thinking about the snake oil salesmen of this world. In the old westerns, the snake oil guy would come into town saying, ‘This potion will cure baldness. This one will make the horse eat.’ We’re not far removed from that, are we?” **“Gates of Hell”** “There are some deep, dark moments on this record, and this one goes to purgatory. You get there if you ride with me. It\'s that unity aspect of this beautiful metal community that we\'ve got. Sign on the line, let the Priest sell your soul. I was thinking of the PMRC, and I was thinking about devil music, and the people that used to come and stand outside the venues with placards: \'Judas Priest is the devil,\' and all that fun stuff. This is kind of throwing it back in their faces.” **“Crown of Horns”** “It\'s about finding love. I think if you can find love, it makes you complete. And it\'s a very deep song for me, spiritually. It\'s about finding Christ, really, but I wrap it up in that beautiful sphere of love. Love is all that matters. Love beats hate worldwide no matter where you\'re from. It\'s what keeps us all together.” **“As God Is My Witness”** “I think what\'s happening with me here is there\'s a lot of mortality going in my mind. Life can be a battle. I mean, it can be a battle trying to get the particular brand of bread that you want—‘they’re out of the bread!’ Originally, we were going to call this song ‘Hell to Pay,’ but ‘As God Is My Witness’ felt better. It’s something people actually say, like, ‘You’ve got another thing coming,’ or ‘Breaking the law.’ These phrases are out in the world, and they’re fun to utilize.” **“Trial by Fire”** “I saw something on Netflix about the Salem witch trials. The horrific way all those women were treated was out of pure superstition. The power of religion is profound in the way it affects humanity, and some of that is trauma. That was kind of the spark for this, but it’s also a bit of a reference to the way the public, when they get a story or an incident—and this is human nature—become the judge, the jury, and the executioner. We are so fast to create our opinions.” **“Escape From Reality”** “The bulk of that song comes from \[guitarist\] Glenn \[Tipton\]. He has these riff vaults. The thing about a riff is that it doesn’t matter if he wrote it in 1970 or 2023. Within *Invincible Shield*, it’s an affirmation of the heaviness of Judas Priest in this slow-tempo context. I think it’s the only one on the album with that kind of groove. Some of the messages on this album are quite personal, and ‘Escape From Reality’ is one of those. It’s about wishing you could go back in time to fix certain things, whatever they might be. It could be as simple as an argument in a relationship, or something big and traumatic.” **“Sons of Thunder”** “When you sit astride a Harley or whatever it is, it epitomizes freedom. The bike represents so many things with Judas Priest, and we\'re the only heavy metal band that\'s utilized the bike consistently. Those things that are attached to the bike—it\'s loud, it smells, it pisses people off—that\'s metal. I just wanted to have a bit of fun with that. And it\'s a little bit of a nod to *Sons of Anarchy*, because that free spirit, that part of Americana, is with us.” **“Giants in the Sky”** “The touchstones for this were Ronnie \[James Dio\] and Lemmy, two of my dear friends. Originally it was going to be called ‘The Mighty Have Fallen,’ but I thought that just sounds too bleak. Let\'s give it some lift. Let\'s give it some transcendence. I was also thinking about rock ’n’ roll radio. When I was growing up in England, we had one station. The first time I came to America, I couldn’t believe how many stations there were. And right now, as you and I are speaking, somebody in the world is playing Ronnie or Lemmy over the radio. They’re the giants in the sky.” **“Fight of Your Life”** “This is a bonus track. I really wanted it in the main track listing, but I didn’t get my way. I’m not a fan of brutal sports, but I do understand the athleticism and the skill of MMA and boxing, and even the fun stuff like wrestling. And you are fighting for your life. It’s a struggle and you’re pushing through. But I love this song. To me, it’s like, ‘Can we please put this song up for the NFL or NBA?’” **“Vicious Circle”** “Sometimes relationships can be in a vicious circle. ‘With the wicked schemes, cut deep the way that you can try/It makes me wonder how you sleep.’ So, again, we\'re in the political arena, aren\'t we? ‘I stand against you as you rage. My fate has struck your gilded cage.’ It\'s about the way personal relationships can sometimes get into a vicious circle, but it\'s also addressing the political spectrum.” **“The Lodger”** “Bob Halligan Jr. wrote this. He wrote ‘Some Heads Are Gonna Roll’ and ‘(Take These) Chains.’ He came to a show a few years ago, just to see the band. It was so great to see him, and I love what he’d done with those two tracks, so I said, ‘If you’ve got anything, send it to me.’ Maybe a month later, he sends me this. It’s about a guy who kills his wife and then his sister. It’s like a mini-movie about revenge and justice. Bob has a great talent for words and imagery, and I really love the dark and mysterious atmosphere of this song.”

For his seventh solo outing, Iron Maiden vocalist Bruce Dickinson almost made a concept album. Instead, he made an album with a concept. Some of the songs on *The Mandrake Project* detail episodes from a 12-issue comic series (also called *The Mandrake Project*) created by Dickinson, scripted by Tony Lee, and illustrated by Staz Johnson. “It was never intended to be this big,” Dickinson tells Apple Music. “At first, I had an idea about doing one comic only, like a little bit of extra vibe around the album. I was already thinking in the comic world, because originally the title of the album was taken from a Doctor Strange episode called ‘If Eternity Should Fail!’ I came up with these two characters, Dr. Necropolis and Professor Lazarus, and it’s a really dark story. It\'s not a superhero story. It’s more like a *Watchmen*-style comic in 12 episodes.” With longtime producer and guitarist Roy Z, Dickinson wrote songs that tie in with the comic storyline, like “Afterglow of Ragnarok” and “Resurrection Men,” and others that are completely unrelated, like “Many Doors to Hell,” about a female vampire, and “Fingers in the Wounds,” which imagines Jesus resurrected as a social media influencer. And then there’s “Eternity Has Failed,” an earlier version of which was nicked by Iron Maiden for their 2015 album, *The Book of Souls*. Below, the singer details each track. **“Afterglow of Ragnarok”** “This is meant to be like a hallucination from mandrake juice. Dr. Necropolis is a brilliant scientist, and an orphan. He’s interested in bringing back his brother who died at birth. He’s wondering why he survived and his brother died. And he’s tortured by this voice in his head, which he assumes is his brother. The voice just says, ‘Save me,’ over and over. It hits Necropolis like a depression. He gets into drugs and sex magic and the occult to try and contact his brother and try to figure out a way to bring him back. That’s what drives him and propels him through the story.” **“Many Doors to Hell”** “This is about a female vampire who wants to be human again. She wants to feel what it\'s like to not just bite people in the neck, but to maybe kiss them or make love. Instead of the weird vampire orgasm of drinking blood and stuff, she wants to feel what it\'s like to be a woman again. She\'s fed up with living forever with dead people. So she\'s waiting for the moment when she can step outside. And that moment is when there\'s an eclipse. During the eclipse, she can go out and she can be human. And maybe there\'s a way back for her to be human permanently.” **“Rain on the Graves”** “The title is a phrase I’d written down 10 years before I actually wrote the song. I was in a part of England called the Lake District, a very beautiful area that lots of poets and artists lived in. William Wordsworth had a cottage there and wrote a lot of his best poetry there. He’s buried in the local church, which is where this wedding was that I was invited to, and I decided to find his grave. It was raining and really atmospheric, and I sat there for about 40 minutes just thinking about what an incredible creative mind he had. Years later, Roy and I decided to write this song, which is kind of like ‘Cross Road Blues’ by Robert Johnson, where he meets the devil, but instead of at a crossroads it takes place in a graveyard.” **“Resurrection Men”** “This one is related to the comic. The Resurrection Men are Professor Lazarus and Dr. Necropolis. While I was doing the beginning bit with these open guitar chords, I noticed the tremolo button on the amp. I went, ‘Hang on, what does this button do?’ It was the full-on Dick Dale surf sound, so I thought, ‘What would a Tarantino heavy metal opening sound like?’ So I played that on guitar. I thought Roy would redo it, but he decided to keep mine. And then I put the bongos on it later, because if you’ve got a Tarantino thing, you’ve got to have bongos on it as well.” **“Fingers in the Wounds”** “The fingers in the wounds are the stigmata of Christ. I think it was St. Francis who had the stigmata appear, which proved that he was holy. The song is about the wonderful world of influencers, but with a twist: What if Jesus came back as an influencer? Like, ‘Put your fingers in your iPhones, put your fingers in my wounds, I’ll sell you a piece of my cloth. I can sell pearls to oysters, feed them to swine.’ It’s the way that everything on the internet now is just degraded by trolls and idiots and fake news and all that stuff. And all these influencers are just worthless, fake people. What have they done in their lives to justify all these people following them around like little dogs? I hate all that. That’s why I’m not part of it.” **“Eternity Has Failed”** “Originally, it was entitled ‘If Eternity Should Fail.’ The title comes from a Doctor Strange episode. It was going to be the title track to the record, but then Maiden co-opted it onto their record. By the time I returned to it, I\'d already got this idea for the comic series pretty well developed, so I thought I\'d just tweak a couple of the words to make it reflect the story more. So we did that, and then stuck a few more bits on, like the flutes and percussion at the beginning that give it that spaghetti western type of feel. The last bit of spoken word is the last slide of episode one of the comic.” **“Mistress of Mercy”** “Who is the mistress of mercy? It’s music. I wrote this on acoustic guitar, but the middle bit, the funny little Jeff Beck-type guitar riff, I wrote on a keyboard. And then Roy played it on guitar. I wanted a mashup of something that was really thrashing, like some garage band going apeshit, along with the acoustic feel. The idea is that the music is the dominatrix. She holds you, pins you down, but you can’t help but adore her and love her. The ecstasy, the harmony, the melody drives you absolutely crazy. That’s what the song is about.” **“Face in the Mirror”** “This is a melancholy tune. It\'s about alcoholism, but also it\'s about the way people judge other people and judge themselves. It\'s sung from the point of view of somebody who is a drunk, but he\'s turning around and saying, ‘You\'re laughing at me because I\'m lying on the ground, but when I hold my glass up, I can see right through you. I can see all your bullshit. I can see all your lies. You’re going to judge me because I’m an alcoholic, but take a look in my mirror, because you might see yourself as well.’” **“Shadow of the Gods”** “This one goes back to just after *Tyranny of Souls*. This and the title track from that album were written as a pair for a project that never happened called The Three Tremors, which was supposed to be three metal singers, like The Three Tenors in classical music. It was going to be me, Rob Halford, and Ronnie James Dio. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen because Ronnie passed away. So I recorded ‘A Tyranny of Souls’ for myself and then kept this one. When I revisited it, I put a couple references to the comic in it. There’s a part two-thirds of the way through that sounds very reminiscent of Judas Priest because that’s who was supposed to sing it.” **“Sonata (Immortal Beloved)”** “This is the oldest song on the record. It’s almost 25 years old. There’s a sample of Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight Sonata’ running underneath the drum machine, so Roy and I were just calling it ‘Sonata’ for a while. Roy later told me it was inspired by the film *Immortal Beloved*. He went to the movies, came home, and pulled an all-nighter, layering keyboards and guitars just for the hell of it. When he sent it to me, I didn’t have any ideas, but I just gave it a try and what came out was about 80% of the vocal, including the spoken word. I just did it freestyle, with no notes or anything. I don’t think that’s happened to me ever again in that way, with that level of detail.”

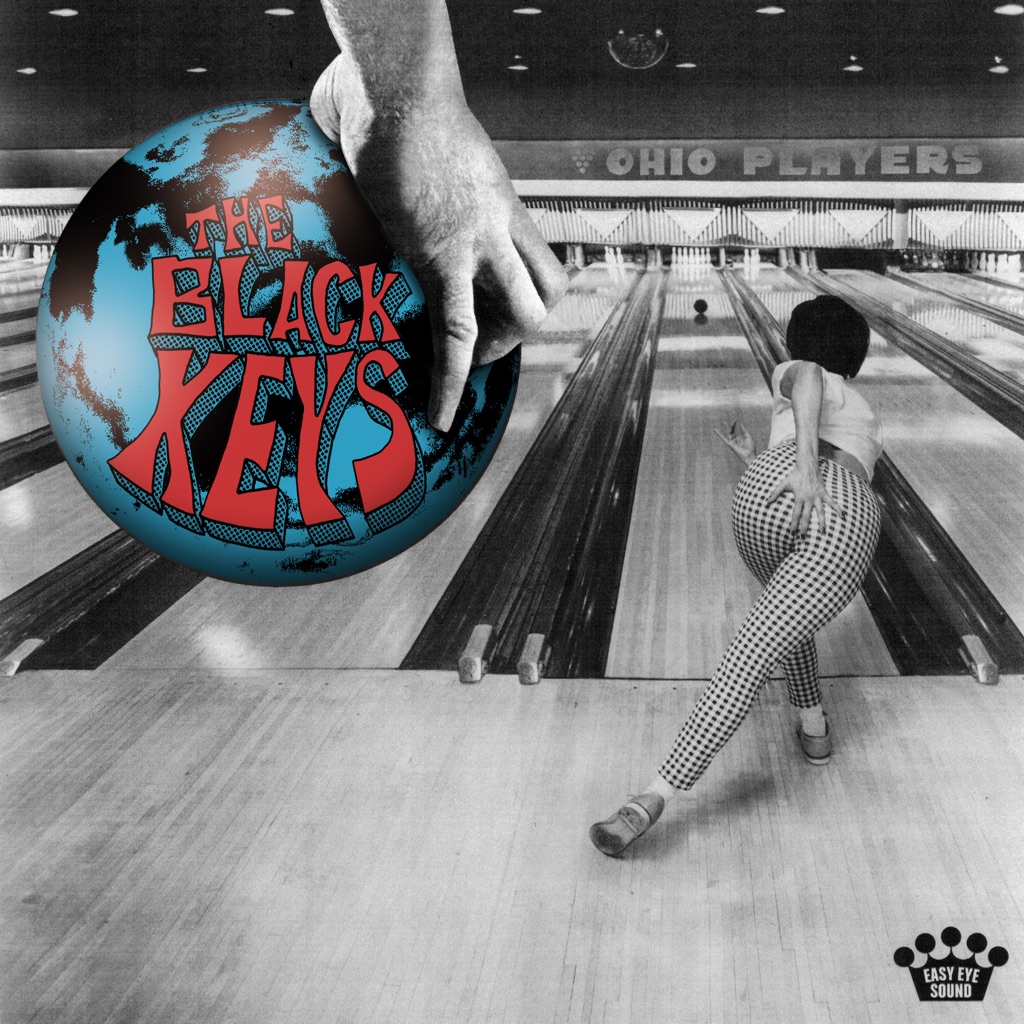

The Black Keys have spent the past two decades carrying the banner of blues-rock revivalism into the present. The duo have sold more records than most pop stars and have proven, time and time again, that rock has always been here—if you were willing to look. The band, made up of Dan Auerbach and Patrick Carney, emerged from Akron, Ohio, in the early aughts as a welcome counterbalance to what was monopolizing record shelf space at the time. The New York City alternative scene was thriving, with bands including The Strokes, LCD Soundsystem, and Interpol dictating the sound coming out of venues, warehouses, and loft spaces up and down the East Coast. Auerbach and Carney, meanwhile, were crafting a sound that was more Mississippi Delta than Mercury Lounge. The duo’s shared love of Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Thin Lizzy, and T. Rex formed the foundation of their lo-fi sound, and they spent the next two decades expanding their range, introducing elements of psychedelia and big-chorus anthems that made them festival-headlining mainstays. Now, The Black Keys are returning with album number 12, the aptly titled *Ohio Players*, a project that bubbles over with the energy of two dudes just here for a good time. “I think once we experienced success, it was like, ‘Let’s try to keep it going and not make the same record again,’” Carney tells ALT CTRL Radio’s Hanuman Welch. “But what happened during this process was the pandemic hits, and after a year of not seeing each other, we walk in the studio to start working on our next record, and something had just changed between us. It was like we finally became best friends; everything was enjoyable. Creatively, we were starting to kind of push things a little bit, but as soon as we finished \[2022 album\] *Dropout Boogie*, before it was even released, we started working on this record. The intention was to call our friends to come in and work with us.” Past collaborations have netted The Black Keys the sort of accolades other bands work their entire careers hoping to achieve. The duo’s *El Camino*, co-produced by Danger Mouse, won Grammys for Best Rock Album and Best Rock Performance in 2013. But *Ohio Players* is the first time the band has truly collaborated in the sense of sharing writing and performing duties. And then they brought on some friends. The album’s first single, “Beautiful People (Stay High),” was co-written by Beck and Dan the Automator, and is the result of supporting Beck on tour 20 years ago after meeting him at a 2003 *SNL* after-party. “I just busted out this promo CD,” Carney remembers. “And I was like, ‘This is my band.’ And two weeks later, Beck reached out and took us on tour. So, this track is a result of this relationship and fandom that I have for Beck. We’ve been talking about making music off and on for years, and right when we finished our last record, we’re like, ‘Get down, it’s time.’” The Black Keys managed to enlist another generational talent for the project: Oasis’ Noel Gallagher. “\[Collaboration\] can always fall flat on its face,” says Carney. “And so, we basically spent 80 grand running the gamble of, ‘This could not work,’ because we didn\'t have a song. So, we booked the smallest, tiniest studio in London, really, Toe Rag—it’s where The White Stripes did *Elephant*. It was, like, zero frills. We showed up, and Noel was there—a guy we’ve briefly met a couple of times, and a legend—and we’re now going to write a song from scratch. Within two hours, we had it, and within another two hours, we had the take. Noel was like, ‘I’ve never actually done this before.’” Two decades in, the novelty of working with people whose music they love still hasn’t worn off. “The thing I’m most proud of, as a fan of music, is to have gotten in the studio with people who I’m a fan of and make something I’m proud of and that they’re proud of,” adds Carney. “It just is a really amazing feeling.”

The White Stripes were nothing if not a formal exercise in exploring the possibilities of self-imposed limitation—in instrumentation, in color scheme, in verifiable biographical information. Since the duo’s dissolution in 2011, Jack White has continued playing with form (and color schemes), from the just-one-of-the-boys-in-the-band vibes of The Raconteurs to 2022’s sonically experimental *Fear of the Dawn* and its more restrained companion *Entering Heaven Alive*. Despite—or perhaps *to* spite—those who longed for a simpler, noisier, more monochromatic time, White tinkered away. The rollout for *No Name*, White’s sixth solo album, was characteristically mischievous: It first appeared as a white-label LP given away at Third Man Records before being posted online without song titles, sparking an excitement that felt fresh, largely because the sound did not. Meg White is not walking through that door anytime soon, but the 13 tracks here channel the unadorned, wild-eyed ferocity of the band that made him famous more efficiently and consistently than anything he’s done since. There’s plenty of swagger from top to bottom, but most of all there’s *hooks*: big, fat, noisy guitars played in the catchiest combinations possible. “That’s How I’m Feeling” may not relieve “Seven Nation Army” of its ubiquity anytime soon, but it is a ready-made capital-A anthem with a euphoric jump-scare chorus that sticks on first listen and doesn’t get unstuck. “Bless Yourself,” “Tonight (Was a Long Time Ago),” and “Number One With a Bullet” are just as infectious, while “Bombing Out” may be the fastest, heaviest thing White has ever put out in any of his many guises. The casualness of it all is a flex—as meticulous and exacting as White can be, *No Name*’s modest arrival is a reminder of how easily he could have kept churning out earworm White Stripes songs. Good for him that he didn’t want to; good for us that he does now.

IDLES’ fifth album is a collection of love songs. For singer Joe Talbot, it couldn’t be anything else. “At the time of writing this album, I was quite lost,” he tells Apple Music. “Not musically, it was a beautiful time for music. But emotionally, my nervous system needed organizing, and I needed to sort my shit out. So I did. That came from me realizing that I needed love in my life, and that I had sometimes lost my narrative in the art, which is that love is all I’ve ever sung about.” From a band wearied by other people’s attempts to pin narrow labels like “punk” or “political” to their expansive, thoughtful music, that’s as concise a summary as you’ll get. It’s also an accurate one. The Bristol five-piece’s music has always viewed the world with an empathetic eye, processing the human effects and impulses around subjects as varied as grief, immigration, kindness, toxic masculinity, and anxiety. And on their fourth album, 2021’s *CRAWLER*, the aggression and sinew of earlier songs gave way to more space and restraint as Talbot turned inward to reckon with his experiences with addiction. For *TANGK*, that experimentation continued while the band’s initial ideas were developed with Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich in London during late 2022, before the record was completed with *CRAWLER* co-producer Kenny Beats joining the team to record in the south of France. They’ve emerged with an album where an Afrobeat rhythm played out on an obscure drum machine (“Grace”) or a gentle piano melody recorded on an iPhone (“A Gospel”) hit with as much impact as a gale-force guitar riff (“Gift Horse”). Exploring the thrills and the scars of love in multiple forms, Talbot leans ever more into singing over firebrand fury. “I’ve got a kid now, and part of my learning is to have empathy when I parent,” he says. “And with that comes delicacy. To use empathy is a delicate and graceful act. And that’s coming out in my art, because I’m also being delicate and graceful with myself, forgiving myself, and giving myself time to learn. I don’t want to lie.” Discover more with Talbot’s track-by-track guide to *TANGK*. **“IDEA 01”** “It was the first thing \[guitarist and co-producer Mark\] Bowen worked on, and Bowen, being the egotistical maniac that he is, called it ‘IDEA 01’ because he forgot that it was actually idea seven. But, bless him, he does like attention. But, yes, it was the first song that was written in Nigel’s studio. Bowen sat at the piano and started playing, and it was beautiful. ‘IDEA 01’ is different vignettes around old friends that I haven’t seen since Devon \[where Talbot grew up\], and the relationships I had with them and their families, and how crazy certain people’s families are. Bowen’s beautiful piano part reminded me of this song we wrote on the last album, ‘Kelechi.’ Kelechi was a good friend of mine who sadly passed away, and I hadn’t seen him since I waved him off to move to Manchester with his family. I just had this feeling I was never going to see him again. Maybe I’m writing that in my head now, but he was a beautiful, beautiful man. I loved him. I think maybe if we were still friends, part of me could have helped him, but that’s, again, fantasy I think.” **“Gift Horse”** “I was trying to get this disco thing going, so I gave Jon \[Beavis, drummer\] a bunch of disco beats to work on. And Dev \[bassist Adam Devonshire\] is bang into The Rapture and !!! and LCD Soundsystem, and he turned out that bassline real quick. I wrote a song around it, and it felt great. It was what my intentions of the album were: to make people dance and not think, because love is a very complex thing that doesn’t need to be thought. It can just be acted, and worked on, and danced with. I just wanted to make people move, and get that physicality of the live experience in people’s bones. I had this concept of a gift horse as a theme of a song, and it sang to me. I like that grotesque phrase, ‘Never look a gift horse in the mouth.’ It’s about my daughter, and I’m very grateful for her, and our relationship, and I wanted to write a beast of a tune around her.” **“POP POP POP”** “I read \[‘freudenfreude’\] online somewhere. It was like, words that don’t exist that should exist. Schadenfreude is such a dark thing, to enjoy other people’s misery, so the idea of someone enjoying someone else’s joy is great. Being a parent, you suddenly are entwined with someone else’s joys and lows. I love seeing her dance, and have a good time, and grow as a person, and learn, so I wanted to write a song about it.” **“Roy”** “It’s an allegorical story that sums up a lot of my behavior towards my partners over a 15-year period where I was in a cycle of absolute worship and then fear, jealousy and assholery. I wanted to dedicate it to my girlfriend, who I call Roy. She’s not called Roy. I wanted it to be about the idea of a man who is in love and then his fears take over, and he starts acting like a prick to push that person away. Then he wakes up in the morning with a horrible hangover, realizing what he’s done, and he apologizes. He is then forgiven in the chorus, and rejoicing ensues.” **“A Gospel”** “It’s a reflection on breakups, which I think are a learning curve. I think all my exes deserve a medal, and they’ve taught me a lot. It’s really a tender moment of a dream I used to have, then \[it\] dances between different tiny memories, tiny vignettes of what happened before, and me just giving a nod to those moments and saying goodbye, which is beautiful. No heartbreak, really. I’ve been through the heartbreak now. It’s just me smiling and being like, ‘Yeah, you were right. Thank you very much.’” **“Dancer” (with LCD Soundsystem)** “The best form of dance is to express yourself freely within a group who are also expressing themselves freely, the true embodiment of communion. The last time I had this sense of euphoria from that was an Oh Sees gig at the \[Sala\] Apolo in Barcelona. I closed my eyes and let the mosh push me from one side of the room to the other and back. I didn’t open my eyes once, I just smiled and was carried by this organism of beautiful rage. Dancing’s a really big part of my personality. I love it. My mum always danced. Even in her most ill days \[Talbot’s mother passed away during the recording of 2017 debut *Brutalism*\], she would always get up and dance, and enjoy herself. I dance with my daughter every day that I have her. I think it’s magic and important.” **“Grace”** “It all came out of nowhere. I had this beat in mind for a while—I was thinking of an aggro Afrobeat kind of track. But it didn’t come out like that. It came out like what happens when Nigel Godrich gets his hands on your Afrobeat stuff. I asked Nigel to make the beat, and he chose the LinnDrum \[’80s drum machine\]. The LinnDrum changes the sound of a beat, the tone of a drum, the cadence of a beat, it changed the beat completely. It’s a very, very delicate thing, a beat. It sounded like a different song to me. It sounded amazing. And that’s where the bassline came from. And then that’s where the vocals came from. It felt a bit uneasy for a long time because it came out of nowhere. Me and Bowen were like, ‘Is this right? Is this complete?’ I think it just has to feel like you, like it is part of you and what you mean at the moment, that’s all. An album’s an episode of where you’re at in the world in that point in time.” **“Hall & Oates”** “I wanted to write a glam-rock pounder about falling in love with your boys. My ex and I used to joke about this thing where you make love to someone for the first time, and then the next day, you’re walking on air, and it feels like Hall & Oates is playing. The birds are singing, you’re bouncing around and everything’s great. I wanted to use that analogy for when you make friends with someone for the first time, and they make you feel good, lighter, stronger, excited to see them again. And that’s what happened in lockdown: I made friends with \[Bristol-based singer-songwriter\] Willie J Healey and my mate Ben, and we went on bike rides whenever we could, getting out and feeling good post-lockdown. It gave me a sense of purpose again. It felt like I was falling in love.” **“Jungle”** “I was trying to write a jungle tune for ages. The guitar line was a jungle bassline that I had but it just never fit what we were writing. And then Bowen started playing the chords on the guitar and it transformed it into something completely different. It completely revitalized what I’d been dragging through the mud for five years. Bowen made it IDLES, made it real, made it believable, made it beautiful. And then it reminded me of getting nicked, so I wrote a song about different times that I’ve been in trouble.” **“Gratitude”** “This was a real struggle. Bowen was really obsessed about doing interesting counts with the beats. I just wanted to make people dance and create infectious beats. We were coming from very different angles, but we loved this song that Bowen had made. I was like, ‘I get it, Bowen. This is insane. I love it, but I can’t get it.’ We hung on to it for ages, and then Nigel really helped us out, he created spaces and bits here and there by turning things down and moving everything slightly. Then Kenny helped me out, and got rid of the stupid counts, I think, and helped me write it on a 4/4 beat. And then they changed it back. I just come in in weird places. Everyone chipped in, because everyone believed in the song.” **“Monolith”** “I was fascinated by films where four or five notes are repeated throughout and create this monolithic motif. There’s a sense of continuity but the mood changes depending on certain things like tone and instruments. I wanted to do that over a song, and we got our friend Colin \[Webster\] from \[London noise rock unit\] Sex Swing to do the sax, we did it on different instruments that Nigel had. Nigel went away and basically put it all through the hollow-body bass. It reminded me of a documentary from a series called *The Blues* that Martin Scorsese curated. *The Soul of a Man* \[directed by Wim Wenders\] is about a song \[Blind Willie Johnson’s ‘Dark Was the Night’\] getting sent into space. If any aliens get this capsule, they’ll hear this song being played from a blues artist. It created a really beautiful and deep picture in my mind. It felt like this monolith drifting in the ether. I started singing a blues riff behind it, a Skip James kind of thing. I think it’s a beautiful way to finish the album—us drifting in the ether.”

Arriving 20 years after the open political ire of *American Idiot*, Green Day’s 14th album sees the veteran California punk trio energized by a new wave of worrying trends. Now in his early fifties, singer/guitarist Billie Joe Armstrong retains the snotty defiance that has always been his calling card, whether the stakes are high or low. He doesn’t mince words on opener and lead single “The American Dream Is Killing Me,” calling out the nation’s boom in conspiracy theories and reimagining the classic patriotic lyric “my country, ’tis of thee” as “my country under siege.” While less of a concept album than the rock opera turned stage musical *American Idiot*, *Saviors* still latches on to some recurring themes in the name of getting a point across, such as updating 1950s-era rock ’n’ roll tropes: “Bobby Sox” swaps the aw-shucks question “Do you wanna be my girlfriend?” with “Do you wanna be my boyfriend?” while the timeless-sounding romantic ballad “Suzie Chapstick” is timestamped with a reference to absently scrolling Instagram. And “Living in the ’20s” may flash a guitar solo ripped straight from rock’s earliest days, but it also cites the more modern markers of mass shootings and pleasure robots. Armstrong’s urgent venting is delivered within some of Green Day’s catchiest songs since the 1990s, and longtime producer Rob Cavallo proves just as crucial to the album’s punchy, uncrowded sound as bassist Mike Dirnt and drummer Tré Cool. After all, Cavallo helmed the band’s 1994 smash *Dookie*, and *Saviors* sneaks in a few nods to that ripe era too. The sheer simplicity of the chugging chords opening “Strange Days Are Here to Stay” evokes the former album’s hit single “Basket Case,” while the mortality-minded closer “Fancy Sauce” borrows Nirvana’s coupling of “stupid and contagious.” The bubblegum anthem “Look Ma, No Brains!” harks back even further to Green Day’s DIY roots (and before that, pop-punk godfathers the Ramones), further cementing the idea that righteous anger goes down easier smuggled inside a pop song.

For their 14th album, Swedish prog wizards Opeth created a concept record around the reading of a will. Partly inspired by a talk-show segment and partly by the massively popular TV show *Succession*, Opeth guitarist/vocalist Mikael Åkerfeldt decided to write about an inheritance with a twist. “I stumbled upon the idea of putting the whole story as it would’ve been written in a legal document, like a proper old piece of paper with paragraphs like, ‘My daughter will get the country house,’ and things like that,” he tells Apple Music. “But it’s more like a confession of sorts, where the patriarch reveals secrets about himself, his paranoia, and his regrets. And some of these secrets will immediately affect his children in an existential kind of way.” *The Last Will and Testament* also marks Åkerfeldt’s return to the death-metal vocal style of Opeth’s early days. “I wanted to bring back the screaming vocal, but at first, I felt a bit like a fraud because I wasn’t listening to brutal music,” he explains. “I’m listening to Dexter Gordon and David Crosby. But after I finished two songs with that kind of vocal, I thought it was fucking awesome.” Add guest appearances from Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson (on flute and narration) and Europe vocalist Joey Tempest, and you’ve got another fascinating installment in Opeth’s catalog. Below, Åkerfeldt comments on each track. **“§1”** “This was the first song written for the album. It’s when I dipped my toe in the water, so to speak, to see where I was on a musical level. At the time, I didn’t really have the lyrics ready, but I wanted to try out that screaming vocal. So, this song is kind of the guinea pig for that. And usually, when I start writing for a record, I come out all guns blazing. So, it’s kind of heavy, evil, fast, and a bit insane. Lyrically, the kids are being summoned to attend the reading of their late father’s last will and testament. There’s also a couple of solicitors in place. The reading starts, and he’s explaining that there’s going to be prizes. But they might not be what you wanted.” **“§2”** “I can hear that I was quite comfortable with whatever I was doing musically here. And that kind of stands out because it has two guests on there. On ‘Paragraph One’ you have a voice-over thing by Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull, and he’s heavily featured in ‘Paragraph Two’ as well. And so is Joey Tempest, from Europe. For some reason, he loves Opeth, which is awesome for me because I grew up with Europe. The song itself is pretty adventurous, I think. It’s probably one of the songs that will take a long time to sink in with the listener. There’s also a calm section that I kind of nicked from Paul Simon’s ‘Still Crazy After All These Years.’” **“§3”** “This is more of a classic heavy metal song, I would say. The opening was inspired by a theme you often hear in jazz music, like Django Reinhardt, but also some classical music and fusion-rock bands. And the musical *Chess*, believe it or not, which was written by Benny and Björn from ABBA. From there, it kind of becomes a normal heavy metal song, but with more emotions than your basic Iron Maiden song. I’m not saying Iron Maiden doesn’t have emotions, but this is kind of a sad song—to me at least. Lyrically, there’s some explanation about infidelity that happened and what that led to.” **“§4”** “This is an interesting tune because it’s almost like a couple of different songs in one, which is not so uncommon for Opeth. I started off trying to write something called 12-note music, which is an experimental classical thing where you have 12 notes in an octave, and you can’t play the same note twice—meaning it’s going to be fucked up. So, the beginning of the song is hard to sing along to. It’s a bit Zappa-esque. That leads into kind of a metal-y call-and-response with death metal vocals and clean vocals, and then it stops and goes into a harp section. I actually found the harp player from an article in a Swedish newspaper, which is weird. That leads to the next section, which is Ian Anderson playing the flute. Then it builds into the most vicious, evil-sounding music on the record.” **“§5”** “This is maybe the last song I wrote for the record, or one of the last. You can tell that I’m comfortable in my songwriting here because it’s quite experimental. There’s not a lot of acoustic guitars on this record, but this song is built around an acoustic lick and clean vocals, and all of it gradually becomes heavier. In some parts, maybe the heaviest sections on the record. And really good death-metal vocals on that track, if I do say so myself. There’s also a Middle Eastern-sounding midsection, which I never dared to do before. If you just hear the song once, you probably won’t know what the fuck is happening. You need some time with it.” **“§6”** “During the recording, everybody feared this song because it’s so difficult. It doesn’t sound difficult, but for some reason, it’s really, *really* difficult. I’m not really a good guitar player or a good musician, but for some reason I have a knack for writing really complex music. And this song, it’s almost like it spirals out of control in a way, like you’re losing control of the horse and it just stampedes. I’ve never done cocaine in my life, but it sounds like what I imagine a cocaine rush is. I think that’s got something to do with me not tampering with the tempo of the song, which resulted in us almost not being able to play the fucking thing.” **“§7”** “This always felt like the ending song of a record, even if there’s one after. But it’s still the end of the testament, as it were. It’s more of a groovy song. I don’t really like that word, but sometimes it’s the only word that applies. It’s slower than the other songs, and less crazy. It’s also the first song in our history where every band member sings. There’s a multipart harmony vocal that happens a couple of times, and everyone is on it. I can tell you there were people who had never been in front of a microphone before, which was quite fun.” **“A Story Never Told”** “At this point, the testament is done. But everything that’s been said in the testament doesn’t really apply because here comes the twist to the story. The inheritance has been settled, a few years have passed, and a letter arrives, revealing a secret. The song itself is a ballad, and I’m a sucker for ballads. I wanted to write a beautiful ballad, not just because I love ballads, but because the seven songs prior to ‘A Story Never Told’ are so intense that there’s no room for breath, really. And this song feels like a good ending, with a beautiful Gilmour/Blackmore-esque solo by \[Opeth guitarist\] Fredrik \[Åkesson\] at the finish.”

It can be dangerous, Nick Cave says, to look back on one’s body of work and seek meaning in the music you’ve made. “Most records, I couldn\'t really tell you by listening what was going on in my life at the time,” he tells Apple Music. “But the last three, they\'re very clear impressions of what life has actually been like. I was in a very strange place.” In the years following the 2015 death of his son Arthur, Cave’s work—in song; in the warm counsel of his newsletter, The Red Hand Files; in the extended conversation-turned-book he wrote with journalist Seán O’Hagan, *Faith, Hope and Carnage*—has been marked by grief, meeting unimaginable loss with more imagination still. It’s made for some of the most remarkable and moving music of his nearly 50-year career, perhaps most notably the feverish minimalism of 2019’s *Ghosteen*, which he intended to act as a kind of communique to his dead son, wherever he might be. Though Cave would lose another son, Jethro, in 2022, *Wild God* finds the 66-year-old singer-songwriter someplace new, marveling at the beauty all around him, reuniting with The Bad Seeds, who—with the exception of multi-instrumentalist songwriting foil Warren Ellis—had slowly receded from view. Once a symbol of post-punk antipathy, he is now open to the world like never before. “Maybe there is a feeling like things don\'t matter in the same way as perhaps they did before,” he says. “These terrible things happened, the world has done its worst. I feel released in some way from those sorts of feelings. *Wild God* is much more playful, joyous, vibrant. Because life is good. Life is better.” It’s an album that feels like an embrace. That much you can hear in the first seconds of “Song of the Lake,” a swirl of ascendant synths and thick, chewy bass (compliments of Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood) upon which Cave tells a tale of brokenness that never quite resolves, as though to fully heal or be put back together again has never really been the point of all this, of being human. The mood is largely improvisational and loose, Cave leaning into moments of catharsis like a man who’d been waiting for them. He offers levity (the colossal, delirious title track) and light (“Frogs,” “Final Rescue Attempt”). On “O Wow O Wow (How Wonderful She Is),” a tribute to the late Anita Lane, his former creative and romantic partner, he conjures a sense of play that would have seemed impossible a few years ago. “I think that it\'s just an immense enjoyment in playing,” he says of the band\'s influence on the album. “I think the songs just have these delirious, ecstatic surges of energy, which was a feeling in the studio when we recorded it. We\'re not taking it too seriously in a way, although it\'s a serious record. We were having a good time. I was having a really good time.” There is no shortage of heartbreak or darkness to be found here. But “Joy,” the album’s finest moment (and original namesake), is a monument to optimism, a radical thought. For six minutes, he sounds suspended in twilight, pulling words out of thin air, synths fluttering and humming and flickering around him, peals of piano and French horn coming and going like comets. “We’ve all had too much sorrow, now is the time for joy,” he sings, quoting a ghost who’s come to his bedside, a “flaming boy” in sneakers. “Joy doesn\'t necessarily mean happiness,” Cave says upon reflection. “Joy in a way is a form of suffering, in the sense that it understands the notion of suffering, and it\'s these momentary ecstatic leaps we are capable of that help us rise out of that suffering for a moment of time. It is sort of an explosion of positive feeling, and I think the record\'s full of that, full of these moments. In fact, the record itself is that.” While that may sound like a complete departure from its most recent predecessors, *Wild God* shares a similar intention, an urge to communicate with his late children, from this world to theirs. That may never fade. “If there\'s one impulse I have, it’s that I would like my kids who are no longer with us to know that we are okay, that \[wife\] Susie and I are okay,” Cave says. “I think that\'s why when I listened to the record back, I just listened to it with a great big smile on my face. Because it\'s just full of life and it\'s full of reasons to be happy. I think this record can definitely improve the condition of my children. All of the things that I create these days are an attempt to do that.” Read on as Cave takes us inside a few highlights from the album: **“Wild God”** “I was actually going to call the record *Joy*, but chose *Wild God* in the end because I thought the word ‘joy’ may be misunderstood in a way. ‘Wild God’ is just two pieces of music chopped together—an edit. That song didn\'t really work quite right. So we thought, ‘Well, let\'s get someone else to mix it.’ And me and Warren thought about that for a while. I personally really loved the sound of \[producer Dave Fridmann’s work with\] MGMT, and The Flaming Lips, stuff—it had this immediacy about it that I really liked. So we went to Buffalo with the recordings and Dave did a song each day, disappeared into the control room and mixed it without inviting us in. It was the strangest thing. And then he emerges from the studio and says, ‘Come in and tell me what you think.’ When we came in it sounded so different. We were shocked. And then after we played it again, we heard that he traded in all the intricacies and stateliness of The Bad Seeds for just pure unambiguous emotion.” **“Frogs”** “Improvising and ad-libbing is still very much the way we go about making music. ‘Frogs’ is essentially a song that I had some words to, but I just walked in and started singing over the top of this piece of music that we\'d constructed without any real understanding of the song itself. There\'s no formal construction—it just keeps going, very randomly. There\'s a sort of freedom and mystery to that stuff that I find really compelling. I sang it as a guide, but listening to it back was like, ‘Wow, I don\'t know how to go and repeat that in any way, but it feels like it\'s talking about something way beyond what the song initially had to offer.’” **“Joy”** “‘Joy’ is a wholly improvised one-take without me having any real understanding of what Warren is doing musically. It’s written in that same questing way of first takes. I\'m just singing stuff over a kind of chord pattern that he\'s got. I sort of intuit it in some way that it’s a blues form to it, so I’m attempting to sing a blues vocal over the top, rhyming in a blues tradition.” **“Final Rescue Attempt”** “That was a song that we weren\'t putting on the record. It was a late addition, just hanging around. And I think Dave Fridmann actually said, ‘Look, I\'ve mixed this song. It doesn\'t seem to be on the record. What the fuck?’ It feels a little different in a way to me. But it\'s a very beautiful song, very beautiful. And I guess it was just so simple in its way, or at least the first verse literally describes the situation that I think is actually in the book, *Faith, Hope and Carnage*, where Susie decided to come back to me after eight months or so, and rode back to my house where I was living, on a bicycle. It’s a depiction of that scene, so maybe I shied away from it for that reason. I don\'t know. But I\'m really glad.” **“O Wow O Wow (How Wonderful She Is)”** “That song is an attempt to encapsulate what Anita Lane was like, and we all loved her very much and were all shocked to the core by her death. In her early days when we were together, she was this bright, shiny, happy, laughing, flaming thing, and we were the dark, drug-addicted men that circled around her. And I wanted to just write a song that had that. She was a laughing creature, and I wanted to work out a way of expressing that. It\'s such a beautifully innocent song in a way.”

Bon Jovi\'s career has been defined by optimism since its leader, the ever-affable Jon Bon Jovi, hustled his way onto New York rock radio in the early ’80s, with songs like “Wanted Dead or Alive” and “Keep the Faith” serving as shout-along anthems. On *Forever*, the New Jersey band\'s 16th album, the band\'s outlook remains bright—although this go-round, marking their 40th anniversary, they\'re celebrating themselves, too. “In the last decade, it\'s been hard to find joy for a lot of reasons; there\'s a lot of joy in this,” Bon Jovi tells Apple Music\'s Zane Lowe. Personal and global challenges—the departure of longtime guitarist Richie Sambora, the pandemic, vocal cord issues that resulted in experimental surgery for the lead singer—weighed heavily. “It was a decade in the making because of that: trials and tribulations. I don\'t want to sound pompous about it, but talk to me about a career after 20. And when you get to 40, now we can start talking about this for real.” *Forever* is a loud and proud shedding of those troubles, 12 tracks that honor and burnish their legacy as one of the MTV era\'s hugest rock bands. Opening track “Legendary” turns the doubt that hovered over the band into a reason for celebration, finding reasons to “raise my hands up to the sky” in old songs and old friends—and in the act of being alive. “Living Proof” harkens back to talk-box-assisted Bon Jovi jams of yore like “Livin\' on a Prayer” in chugging sound and unyielding spirit, with Jon Bon Jovi, his voice a little huskier but still unmistakable, wondering, “Is there anything left for a sinner like me?” and realizing the answer is right under his own roof. Perhaps appropriately given the album\'s name, *Forever* finds Bon Jovi getting a little meta, reflecting on their individual and collective journeys. “We Made It Look Easy” is a charging anthem that calls back to the days when the band was “chasing the dawn/Getting lost in a song,” while “I Wrote You a Song” is a slow-blooming ballad that\'ll have arena audiences raising their lighters, or their phone flashlights. “My First Guitar,” a sparkling power-pop track, is an ode to the instrument on which Jon Bon Jovi cut his teeth, a story inspired by him actually retrieving it—still in its cardboard case—from the New Jersey neighbor who bought it years ago. Its romanticism—“She\'s the only one who knows the way I feel,” he croons—underscores just how passionate Bon Jovi and his bandmates still are about music four-plus decades into their storied career. “Nobody wants to go through the dark periods to get to the light,” he tells Apple Music. “But when you get to the light, it\'s even more joyous.”