Bandcamp Daily's 25 Most Essential Albums of 2021

The records we couldn’t stop playing.

Published: December 17, 2021 15:01

Source

A lot changed for Amythyst Kiah between the 2013 release of her debut album *Dig* and the making of *Wary + Strange*. The singer, songwriter, and instrumentalist gained significant notoriety as part of the roots music supergroup Our Native Daughters, with whom she earned a Grammy nomination (Best American Roots Song) for the song “Black Myself,” on which Kiah was the sole songwriter. Kiah reprises that powerful track here, though she does so in a way truer to her own personal musical sensibilities by fusing her love for both old-time music, which she studied at East Tennessee State University, and indie rock. *Wary + Strange* finds a rich middle ground between these seemingly disparate genres, primarily via the strength of Kiah’s songwriting and singing, the latter of which deserves just as much celebration as her masterful guitar playing, as well as studio assists from producer Tony Berg (Phoebe Bridgers, Andrew Bird).

“I don’t like to agonize over things,” Arlo Parks tells Apple Music. “It can tarnish the magic a little. Usually a song will take an hour or less from conception to end. If I listen back and it’s how I pictured it, I move on.” The West London poet-turned-songwriter is right to trust her “gut feeling.” *Collapsed in Sunbeams* is a debut album that crystallizes her talent for chronicling sadness and optimism in universally felt indie-pop confessionals. “I wanted a sense of balance,” she says. “The record had to face the difficult parts of life in a way that was unflinching but without feeling all-consuming and miserable. It also needed to carry that undertone of hope, without feeling naive. It had to reflect the bittersweet quality of being alive.” *Collapsed in Sunbeams* achieves all this, scrapbooking adolescent milestones and Parks’ own sonic evolution to form something quite spectacular. Here, she talks us through her work, track by track. **Collapsed in Sunbeams** “I knew that I wanted poetry in the album, but I wasn\'t quite sure where it was going to sit. This spoken-word piece is actually the last thing that I did for the album, and I recorded it in my bedroom. I liked the idea of speaking to the listener in a way that felt intimate—I wanted to acknowledge the fact that even though the stories in the album are about me, my life and my world, I\'m also embarking on this journey with listeners. I wanted to create an avalanche of imagery. I’ve always gravitated towards very sensory writers—people like Zadie Smith or Eileen Myles who hone in on those little details. I also wanted to explore the idea of healing, growth, and making peace with yourself in a holistic way. Because this album is about those first times where I fell in love, where I felt pain, where I stood up for myself, and where I set boundaries.” **Hurt** “I was coming off the back of writer\'s block and feeling quite paralyzed by the idea of making an album. It felt quite daunting to me. Luca \[Buccellati, Parks’ co-producer and co-writer\] had just come over from LA, and it was January, and we hadn\'t seen each other in a while. I\'d been listening to plenty of Motown and The Supremes, plus a lot of Inflo\'s production and Cleo Sol\'s work. I wanted to create something that felt triumphant, and that you could dance to. The idea was for the song to expose how tough things can be but revolve around the idea of the possibility for joy in the future. There’s a quote by \[Caribbean American poet\] Audre Lorde that I really liked: ‘Pain will either change or end.’ That\'s what the song revolved around for me.” **Too Good** “I did this one with Paul Epworth in one of our first days of sessions. I showed him all the music that I was obsessed with at the time, from ’70s Zambian psychedelic rock to MF DOOM and the hip-hop that I love via Tame Impala and big ’90s throwback pop by TLC. From there, it was a whirlwind. Paul started playing this drumbeat, and then I was just running around for ages singing into mics and going off to do stuff on the guitar. I love some of the little details, like the bump on someone’s wrist and getting to name-drop Thom Yorke. It feels truly me.” **Hope** “This song is about a friend of mine—but also explores that universal idea of being stuck inside, feeling depressed, isolated, and alone, and being ashamed of feeling that way, too. It’s strange how serendipitous a lot of themes have proved as we go through the pandemic. That sense of shame is present in the verses, so I wanted the chorus to be this rallying cry. I imagined a room full of people at a show who maybe had felt alone at some point in their lives singing together as this collective cry so they could look around and realize they’re not alone. I wanted to also have the little spoken-word breakdown, just as a moment to bring me closer to the listener. As if I’m on the other side of a phone call.” **Caroline** “I wrote ‘Caroline’ and ‘For Violet’ on the same, very inspired day. I had my little £8 bottle of Casillero del Diablo. I was taken back to when I first started writing at seven or eight, where I would write these very observant and very character-based short stories. I recalled this argument that I’d seen taken place between a couple on Oxford Street. I only saw about 30 seconds of it, but I found myself wondering all these things. Why was their relationship exploding out in the open like that? What caused it? Did the relationship end right there and then? The idea of witnessing a relationship without context was really interesting to me, and so the lyrics just came out as a stream of consciousness, like I was relaying the story to a friend. The harmonies are also important on this song, and were inspired by this video I found of The Beatles performing ‘This Boy.’ The chorus feels like such an explosion—such a release—and harmonies can accentuate that.” **Black Dog** “A very special song to me. I wrote this about my best friend. I remember writing that song and feeling so confused and helpless trying to understand depression and what she was going through, and using music as a form of personal catharsis to work through things that felt impossible to work through. I recorded the vocals with this lump in my throat because it was so raw. Musically, I was harking back to songs like ‘Nude’ and ‘House of Cards’ on *In Rainbows*, plus music by Nick Drake and tracks from Sufjan Stevens’ *Carrie & Lowell*. I wanted something that felt stripped down.” **Green Eyes** “I was really inspired by Frank Ocean here—particularly ‘Futura Free’ \[from 2016’s *Blonde*\]. I was also listening to *Moon Safari* by Air, Stereolab, Unknown Mortal Orchestra, Tirzah, Beach House, and a lot of that dreamy, nostalgic pop music that I love. It was important that the instrumental carry a warmth because the song explores quite painful places in the verses. I wanted to approach this topic of self-acceptance and self-discovery, plus people\'s parents not accepting them and the idea of sexuality. Understanding that you only need to focus on being yourself has been hard-won knowledge for me.” **Just Go** “A lot of the experiences I’ve had with toxic people distilled into one song. I wanted to talk about the idea of getting negative energy out of your life and how refreshed but also sad it leaves you feeling afterwards. That little twinge from missing someone, but knowing that you’re so much better off without them. I was thinking about those moments where you’re trying to solve conflict in a peaceful way, but there are all these explosions of drama. You end up realizing, ‘You haven’t changed, man.’ So I wanted a breakup song that said, simply, ‘No grudges, but please leave my life.’” **For Violet** “I imagined being in space, or being in a desert with everything silent and you’re alone with your thoughts. I was thinking about ‘Roads’ by Portishead, which gives me that similar feeling. It\'s minimal, it\'s dark, it\'s deep, it\'s gritty. The song covers those moments growing up when you realize that the world is a little bit heavier and darker than you first knew. I think everybody has that moment where their innocence is broken down a little bit. It’s a story about those big moments that you have to weather in friendships, and asking how you help somebody without over-challenging yourself. That\'s a balance that I talk about in the record a lot.” **Eugene** “Both ‘Black Dog’ and ‘Eugene’ represent a middle chapter between my earlier EPs and the record. I was pulling from all these different sonic places and trying to create a sound that felt warmer, and I was experimenting with lyrics that felt a little more surreal. I was talking a lot about dreams for the first time, and things that were incredibly personal. It felt like a real step forward in terms of my confidence as a writer, and to receive messages from people saying that the song has helped get them to a place where they’re more comfortable with themselves is incredible.” **Bluish** “I wanted it to feel very close. Very compact and with space in weird places. It needed to mimic the idea of feeling claustrophobic in a friendship. That feeling of being constantly asked to give more than you can and expected to be there in ways that you can’t. I wanted to explore the idea of setting boundaries. The Afrobeat-y beat was actually inspired by Radiohead’s ‘Identikit’ \[from 2016’s *A Moon Shaped Pool*\]. The lyrics are almost overflowing with imagery, which was something I loved about Adrianne Lenker’s *songs* album: She has these moments where she’s talking about all these different moments, and colors and senses, textures and emotions. This song needed to feel like an assault on the senses.” **Portra 400** “I wanted this song to feel like the end credits rolling down on one of those coming-of-age films, like *Dazed and Confused* or *The Breakfast Club*. Euphoric, but capturing the bittersweet sentiment of the record. Making rainbows out of something painful. Paul \[Epworth\] added so much warmth and muscularity that it feels like you’re ending on a high. The song’s partly inspired by *Just Kids* by Patti Smith, and that idea of relationships being dissolved and wrecked by people’s unhealthy coping mechanisms.”

The Pakistani musician began writing her second album, and then her younger brother died. And so, instead of the dark, edgy dance record she’d intended on making, Aftab turned to the Urdu ghazals she grew up with—an ancient form of lyric poetry centered around loss and longing. On *Vulture Prince*, Aftab makes the art form her own, trading the traditional percussion-heavy instrumentation for heavenly string arrangements (harp, violin, upright bass); she even ventures into reggae territory on “Last Night,” a slinky rendition of a Rumi poem. She translates another poem, this time by Mirza Ghalib, on “Diya Hai,” the last song she performed for her brother Maher, and a haunting expression of all-encompassing grief.

In Claire Rousay’s music, a field recording is never just a record of a place—it also represents a trace of a personal memory, perhaps even a portal to another world. The Texas experimental musician is constantly recording, translating the murmurs and footfalls of the world around her into dreamy abstractions. Unlike some of her records, where she has run personal correspondence through text-to-speech generators—rendering the most intimate details in surreal, robotic tones—language does not play a central role on *A Softer Focus*. Yet this short, enveloping album is among her most lyrical, emotionally direct works to date. It begins with clatter—fingers tapping on an iPhone, perhaps the rustle of dishes being cleared—but with “Discrete (The Market),” uncharacteristically harmonic sounds rise in the mix, suffusing everything with a warm glow. The reassuringly consonant piano, cello, and synthesizer constitute the record’s nostalgic through line, recalling post-classical composers like Sarah Davachi. But no matter how lulling Rousay’s melodies become, the line between music and sound remains provocatively fuzzy. In “Diluted Dreams,” sparkling drones are shot through with the sounds of passing traffic and kids playing on the street; “Stoned Gesture” flickers in the light of fireworks exploding overhead. Only Rousay knows the precise meaning of these sounds, but for the rest of us, they are suggestive triggers, as evocative as the scent of a freshly cut lawn or hot pavement after a summer rain.

That motherhood is transformative is an understatement. For those who have the experience, it can change who they are and how they perceive the world, with fresh eyes, an open heart, and a devotion so deep it feels like being unmade. Thus, it\'s fitting that Cleo Sol’s *Mother* begins with a monument to maternal love—its abundant patience and grace for which she has a new understanding. “The train never stopped, never had time to unpack your trauma,” the British singer-songwriter croons gently on the opening track, “Don’t Let Me Fall.” “Keep fighting the world, that’s how you get love, mama.” Likewise, “Heart Full of Love” is an ode to her own child (who adorns the cover) that strives to portray both the power of that singular feeling and the gratitude that’s leveled her in its presence: “Thank you for sending me an angel straight from heaven, when my hope was gone, you made me strong...Thank you for being amazing, teaching me to hold on.” The rest of *Mother* unfurls like a letter addressed to a little one who, once removed from the safety of the womb, may come to know cruelty more often than mercy. On the piano-laden centerpiece “We Need You,” she pours into whoever may hear it a reminder of their worth, while a choir summons the divine. “We need your heart, we need your soul,” they sing, “we need your strength through this cold world, we need your voice, speak your truth.” Similar affirmations pepper the album, as Cleo imbues the lyrics with a tenderness that lands like a hug; her voice itself is so elegant and serene these songs, despite the lushness of the instrumentation, nearly resemble lullabies. It’s easy to be given to pessimism, but what she offers here is a balm, brimming with the kind of compassionate optimism that only new life can bring.

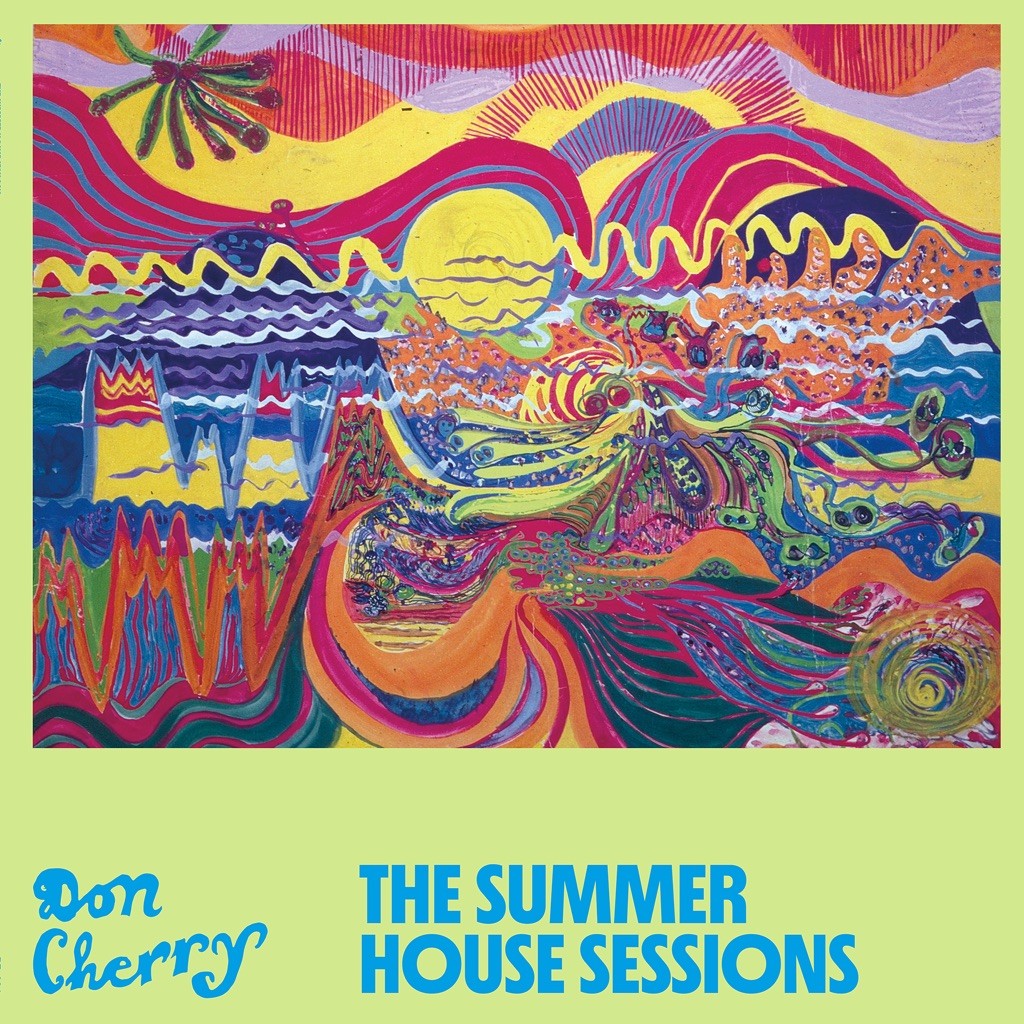

In 1968, Don Cherry had already established himself as one of the leading voices of the avant-garde. Having pioneered free jazz as a member of Ornette Coleman’s classic quartet, and with a high profile collaboration with John Coltrane under his belt, the globetrotting jazz trumpeter settled in Sweden with his partner Moki and her daughter Neneh. There, he assembled a group of Swedish musicians and led a series of weekly workshops at the ABF, or Workers’ Educational Association, from February to April of 1968, with lessons on extended forms of improvisation including breathing, drones, Turkish rhythms, overtones, silence, natural voices, and Indian scales. That summer, saxophonist and recording engineer Göran Freese—who later recorded Don’s classic Organic Music Society and Eternal Now LPs—invited Don, members of his two working bands, and a Turkish drummer to his summer house in Kummelnäs, just outside of Stockholm, for a series of rehearsals and jam sessions that put the prior months’ workshops into practice. Long relegated to the status of a mysterious footnote in Don’s sessionography, tapes from this session, as well as one professionally mixed tape intended for release, were recently found in the vaults of the Swedish Jazz Archive, and the lost Summer House Sessions are finally available over fifty years after they were recorded. On July 20, the musicians gathered at Freese’s summer house included Bernt Rosengren (tenor saxophone, flutes, clarinet), Tommy Koverhult (tenor saxophone, flutes), Leif Wennerström (drums), and Torbjörn Hultcrantz (bass) from Don’s Swedish group; Jacques Thollot (drums) and Kent Carter (bass) from his newly formed international band New York Total Music Company; Bülent Ateş (hand drum, drums), who was visiting from Turkey; and Don (pocket trumpet, flutes, percussion) himself. Lacking a common language, the players used music as their common means of communication. In this way, these frenetic and freewheeling sessions anticipate Don’s turn to more explicitly pan-ethnic expression, preceding his epochal Eternal Rhythm dates by four months. The octet, comprising musicians from America, France, Sweden, and Turkey, was a perfect vehicle for Don’s budding pursuit of “collage music,” a concept inspired in part by the shortwave radio on which Don listened to sounds from around the world. Using the collage metaphor, Don eliminated solos and the introduction of tunes, transforming a wealth of melodies, sounds, and rhythms into poetic suites of different moods and changing forms. The Summer House Sessions ensemble joyously layers manifold cultural idioms, traversing the airy peaks and serene valleys of Cherry’s earthly vision. In the Swedish Jazz Archive quite a few other recordings from the same day were to be found. Some of the highlights are heard as bonus material on the CD edition of this album. The octet is augmented by producer and saxophone player Gunnar Lindqvist, who led the Swedish free jazz orchestra G.L. Unit on the album Orangutang, and drummer Sune Spångberg, who recorded with Albert Ayler in 1962. The bonus CD also includes a track without Cherry featuring Jacques Thollot joined by five Swedes including Lindqvist, Tommy Koverhult, Sune Spångberg, and others. With liner notes by Magnus Nygren and album art featuring a cover painting by Moki Cherry: Untitled, ca. 1967–68.

Fake Fruit distill Pink Flag era Wire, Pylon, and Mazzy Star to expound on the absurdity of modern life. Front woman Hannah D’Amato leads the group through three minute clap backs of minimal, moody post-punk.

The jazz great Pharoah Sanders was sitting in a car in 2015 when by chance he heard Floating Points’ *Elaenia*, a bewitching set of flickering synthesizer etudes. Sanders, born in 1940, declared that he would like to meet the album’s creator, aka the British electronic musician Sam Shepherd, 46 years his junior. *Promises*, the fruit of their eventual collaboration, represents a quietly gripping meeting of the two minds. Composed by Shepherd and performed upon a dozen keyboard instruments, plus the strings of the London Symphony Orchestra, *Promises* is nevertheless primarily a showcase for Sanders’ horn. In the ’60s, Sanders could blow as fiercely as any of his avant-garde brethren, but *Promises* catches him in a tender, lyrical mode. The mood is wistful and elegiac; early on, there’s a fleeting nod to “People Make the World Go Round,” a doleful 1971 song by The Stylistics, and throughout, Sanders’ playing has more in keeping with the expressiveness of R&B than the mountain-scaling acrobatics of free jazz. His tone is transcendent; his quietest moments have a gently raspy quality that bristles with harmonics. Billed as “a continuous piece of music in nine movements,” *Promises* takes the form of one long extended fantasia. Toward the middle, it swells to an ecstatic climax that’s reminiscent of Alice Coltrane’s spiritual-jazz epics, but for the most part, it is minimalist in form and measured in tone; Shepherd restrains himself to a searching seven-note phrase that repeats as naturally as deep breathing for almost the full 46-minute expanse of the piece. For long stretches you could be forgiven for forgetting that this is a Floating Points project at all; there’s very little that’s overtly electronic about it, save for the occasional curlicue of analog synth. Ultimately, the music’s abiding stillness leads to a profound atmosphere of spiritual questing—one that makes the final coda, following more than a minute of silence at the end, feel all the more rewarding.

The highly-anticipated and debut album Black Acid Soul, due for its long awaited release on September 3rd via Foundation Music/BMG. With a voice that has stopped critics in their tracks, Lady Blackbird is a revelatory new talent with music that transcends the jazz scene through which the LA-based artist is rooted. Reflecting influences as varied as Billie Holiday, Gladys Knight, Tina Turner and Chaka Khan, with critics drawing comparisons to Adele, Amy and Celeste, Lady Blackbird’s distinct and beguiling talent is not one to be missed. Honouring the great's has come as a musical process to Lady Blackbird, having recorded her highly anticipated debut album Black Acid Soul in legendary Studio B (Prince’s room) in Sunset Sound, produced by Grammy-nominated Chris Seefried. Minimal yet rich, classic yet timely, the album connects backwards to Miles Davis (his pianist, Deron Johnson, plays Steinway Baby Grand, Mellotron and Casio Synth throughout) and forwards to Pete Tong (he made the Bruise mix of ‘Collage’ his Number Two Essential Selection tune of 2020) and, yes, Victoria Beckham – Matthew Herbert’s remix of second single ‘Beware The Stranger’ soundtracked the designer’s Spring/Summer 2020 Fashion show. Its 11 tracks have a sound, feeling and attitude that speak of Lady Blackbird's deep experiences in music.

When Low started out in the early ’90s, you could’ve mistaken their slowness for lethargy, when in reality it was a mark of almost supernatural intensity. Like 2018’s *Double Negative*, *Hey What* explores new extremes in their sound, mixing Alan Sparhawk and Mimi Parker\'s naked harmonies with blocks of noise and distortion that hover in drumless space—tracks such as “Days Like These” and “More” sound more like 18th-century choral music than 21st-century indie rock. Their faith—they’ve been practicing Mormons most of their lives—has never been so evident, not in content so much as purity of conviction: Nearly 30 years after forming, they continue to chase the horizon with a fearlessness that could make anyone a believer.

Performed with Shirley Tetteh, James Mollison, Edward Wakili-Hick, Nubya Garcia, Dwayne Kilvington, Lyle Barton, Twm Dylan, Jake Long, Rudi Creswick, and Ahnansé. Space 1 Produced, Performed, Recorded by Nala Sinephro (Modular Synths, Synths, Harp) Mixed by Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 2 Performed by James Mollison (Saxophone), Lyle Barton (Piano), Shirley Tetteh (Guitar), Nala Sinephro (Synths), Jake Long (Drums), Rudi Creswick (Double Bass) Composed by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mixed by Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 3 Performed by Nala Sinephro (Modular Synths, Synths), Edward Wakili-Hick (Drums), Dwayne Kilvington (Synth Bass) Produced by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mixed by Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 4 Performed by Nubya Garcia (Saxophone) , Lyle Barton (Keys), Nala Sinephro (Synths), Jake Long (Drums), Twm Dylan (Double Bass), Nubya Garcia appears courtesy of Concord Jazz Composed by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Ben Bell and Nala Sinephro Mixed by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 5 Performed by Nala Sinephro (Modular Synths, Synths, Harp), Ahnansé (Saxophone), Shirley Tetteh (Guitar) Produced by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Nala Sinephro and Rick David Mixed by Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 6 Performed, Composed by Nala Sinephro (Synthesizer), James Mollison (Saxophone), Jake Long (Drums) Produced by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mixed by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 7 Produced, Performed, Recorded by Nala Sinephro (Modular Synths, Synths, Harp) Mixed by Nala Sinephro Mastered by Rick David Space 8 Performed by Nala Sinephro (Modular Synths, Synths, Harp) and Ahnansé (Saxophone) Produced by Nala Sinephro Recorded by Rick David and Nala Sinephro Mixed and Mastered by Nala Sinephro Painting by Daniela Yohannes Design by Maziyar Pahlevan

How did you first experience the poetry, music, and film of Willie Dunn? In a Montreal coffeehouse during the mid-1960s? On a CBC Indian Magazine broadcast with host Johnny Yesno? At a Toronto record store or Native Friendship Centre at the turn of the 1970s? Waiting outside of the Mohawk Nation Longhouse? Maybe in your parent’s record collection on the Rez? A White Roots of Peace gathering? Pow wow? The Mariposa Folk Festival? Or was it that Save James Bay Benefit back in ‘73? On a good friend’s stereo? Sitting around a crackling campfire? How about an old NFB film reel or VHS tape in high school? Or while attending Manitou College? A German concert hall in the 1980s? Maybe a direct action protest on the colonial streets of Canada? Busking in Ottawa during the 1990s? College radio? At Willie’s celebration of life service in 2013 alongside Alanis Obomsawin and Willy Mitchell? LITA’s Grammy-nominated Native North America (Vol. 1) compilation or the very anthology you hold in your hands? There should be no judgement for coming to things when you do. All that’s important is remaining open to life-changing messages such as these… Willie Dunn shared truth through song and celluloid. His original composition, “I Pity the Country,” is an unparalleled statement on the greed and hate created by humankind, recorded in 1971 and still unfortunately needed today. “It’s like the reason you’re supposed to make music,” said Kurt Vile about the song to MOJO Magazine in 2015. With “Charlie,” Willie was the first to deliver the devastating story of Chanie Wenjack and the Canadian residential school system to the music community, nearly 50 years before the much-celebrated Secret Path, yet ignored outside of Indian Country and the folk festival circuit. Dunn’s film technique, featured in 1968’s The Ballad of Crowfoot (NFB), predates the “Ken Burns effect” to great effect. Are you catching the drift? Willie Dunn was not only a trailblazing leader in his time, but well ahead of the curve, simply without the PR push and big money backing of major label players. “He was our Leonard Cohen,” said singer-songwriter Eric Landry about his musical hero. The only difference is that Willie refused to play the Hollywood showbiz game. In talent, he is Cohen, Dylan, and Cash rolled into one and along with Buffy Sainte-Marie, Floyd Red Crow Westerman, and A. Paul Ortega, brought a new set of perspectives and realities to the folk music tradition. Willie spoke directly to his people and Mother Earth through his creations, not only from experience, but by examining his roots and connecting with the world in which he lived. We are humbled to help honour Willie Dunn. May he never be forgotten… PEACE