Nashville’s one-man hit factory presses pause on the production line for a soulful solo debut. 13 years in the writing, the tracks on *Traveller* possess choruses as effortlessly infectious as anything Stapleton has gifted to high profile clients like Adele and Luke Bryan but there’s a fascinating desperation to the themes here. From the wild, sleepless delirium at the heart of “Parachute” to the bandit bluegrass on “Outlaw State of Mind”, this is country rock that’s unafraid to explore drink, drugs, and a very dark underbelly.

The former Drive-By Trucker delivers his most diverse album yet in *Something More Than Free*, a beautifully observed and finely conceived collection of windswept rock that finds the singer/songwriter exploring questions of place and identity. While “Speed Trap Town” perfectly captures the feeling of growing up in rural America, “24 Frames” ponders faith and family—all with the lyrical acuity of Townes Van Zandt and the melodic aplomb of Tom Petty.

Courtney Barnett\'s 2015 full-length debut established her immediately as a force in independent rock—although she\'d bristle at any sort of hype, as she sneers on the noise-pop gem \"Pedestrian at Best\": \"Put me on a pedestal and I\'ll only disappoint you/Tell me I\'m exceptional, I promise to exploit you.\" Warnings aside, her brittle riffing and deadpan lyrics—not to mention indelible hooks and nagging sense of unease with the world—helped put *Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometimes I Just Sit* into the upper echelon of 2010s indie rock. The Melbourne-based singer-songwriter stares at stained ceilings and checks out open houses as she reflects on love, death, and the quality of supermarket produce, making *Sometimes* a crowd-pleaser almost in spite of itself. Propulsive tracks like the hip-shaking \"Elevator Operator\" and the squalling \"Dead Fox\" pair Barnett\'s talked-sung delivery with grungy, hooky rave-ups that sound beamed in from a college radio station\'s 1995 top-ten list. Her singing style isn\'t conversational as much as it is like a one-sided phone call from a friend who spends a lot of time in her own head, figuring out the meaning of life in real time while trying to answer the question \"How are you?\"—and sounding captivating every step of the way. But Barnett can also command blissed-out songs that bury pithy social commentary beneath their distorted guitars—\"Small Poppies\" hides notes about power and cruelty within its wobbly chords, while the marvelous \"Depreston\" rolls thoughts on twentysomething thriftiness, half-glimpsed lives, and shifting ideas of \"home\" across its sun-bleached landscape. While the topics of conversation can be heavy, Barnett\'s keen ear for what makes a potent pop song and her inability to be satisfied with herself make *Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometimes I Just Sit* a fierce opening salvo.

Blessed with a voice of limited but perfect range for his tales of everyday people, James McMurtry remains a songwriter’s songwriter, a man whose lyrics make other songwriters consider rewriting what they originally considered good enough. Working with C.C. Adcock and Mike Napolitano as producers, McMurtry achieves a balance between austere and small-band intimacy, centering the songs on his acoustic guitar’s simple cowboy chords and letting others work around it. His lyrics tell tales of people who remember the past too well (“Carlisle’s Haul”) and who feel like they’re sitting in the perfect seat for observation (“These Things I’ve Come to Know”).

Simmering with slow-burning soul, Natalie Prass’ debut features sophisticated arrangements supported by strings and a horn section. Gorgeous melodies and memorable hooks grace its nine songs and give the album a cohesive mood. Standout tracks like “Bird of Prey” and “Your Fool” play like a cross between Dusty Springfield and classic Philly soul without sounding overtly retro. Her understated, intimate voice is both delicate and darkly sly, a perfect pairing to the sensibilities of producer Matthew E. White and the Spacebomb Records house band. The result is an impressive and assured debut that deserves close attention.

Sufjan Stevens has taken creative detours into textured electro-pop, orchestral suites, and holiday music, but *Carrie & Lowell* returns to the feathery indie folk of his quietly brilliant early-’00s albums, like *Michigan* and *Seven Swans*. Using delicate fingerpicking and breathy vocals, songs like “Eugene,” “The Only Thing,” and the Simon & Garfunkel-influenced “No Shade in the Shadow of The Cross” are gorgeous reflections on childhood. When Stevens whispers in multi-tracked harmony over the album’s title track—an impressionistic portrait of his mother and stepfather that glows with nostalgic details—he delivers a haunting centerpiece.

Thanks to multiple hit singles—and no shortage of critical acclaim—2012’s *good kid, m.A.A.d city* propelled Kendrick Lamar into the hip-hop mainstream. His 2015 follow-up, *To Pimp a Butterfly*, served as a raised-fist rebuke to anyone who thought they had this Compton-born rapper figured out. Intertwining Afrocentric and Afrofuturist motifs with poetically personal themes and jazz-funk aesthetics, *To Pimp A Butterfly* expands beyond the gangsta rap preconceptions foisted upon Lamar’s earlier works. Even from the album’s first few seconds—which feature the sound of crackling vinyl and a faded Boris Gardiner soul sample—it’s clear *To Pimp a Butterfly* operates on an altogether different cosmic plane than its decidedly more commercial predecessor. The album’s Flying Lotus-produced opening track, “Wesley’s Theory,” includes a spoken-word invocation from musician Josef Leimberg and an appearance by Parliament-Funkadelic legend George Clinton—names that give *To Pimp a Butterfly* added atomic weight. Yet Lamar’s lustful and fantastical verses, which are as audacious as the squirmy Thundercat basslines underneath, never get lost in an album packed with huge names. Throughout *To Pimp a Butterfly*, Lamar goes beyond hip-hop success tropes: On “King Kunta,” he explores his newfound fame, alternating between anxiety and big-stepping braggadocio. On “The Blacker the Berry,” meanwhile, Lamar pointedly explores and expounds upon identity and racial dynamics, all the while reaching for a reckoning. And while “Alright” would become one of the rapper’s best-known tracks, it’s couched in harsh realities, and features an anthemic refrain delivered in a knowing, weary rasp that belies Lamar’s young age. He’s only 27, and yet he’s already seen too much. The cast assembled for this massive effort demonstrates not only Lamar’s reach, but also his vast vision. Producers Terrace Martin and Sounwave, both veterans of *good kid, m.A.A.d city*, are among the many names to work behind-the-boards here. But the album also includes turns from everyone from Snoop Dogg to SZA to Ambrose Akinmusire to Kamasi Washington—an intergenerational reunion of a musical diaspora. Their contributions—as well as the contributions of more than a dozen other players—give *To Pimp a Butterfly* a remarkable range: The contemplations of “Institutionalized” benefit greatly from guest vocalists Bilal and Anna Wise, as do the hood parables of “How Much A Dollar Cost,” which features James Fauntleroy and Ronald Isley. Meanwhile, Robert Glasper’s frenetic piano on “For Free? (Interlude)” and Pete Rock’s nimble scratches on “Complexion (A Zulu Love)” give *To Pimp a Butterfly* added energy.

Don\'t let the opening track on Ashley Monroe\'s third album fool you: \"On to Something Good\" may be full of high-tone, major-key hope, but it\'s just the setup for the emotional ride you\'re about to take. The rest of *The Blade* cuts pretty deep as the country firebrand revisits all sorts of painful heartbreak, moving swiftly between the title track\'s hushed balladry and grand, guitar-slinging honky-tonk (\"I Buried Your Love Alive\")—all backed by a lush, big-room Nashville sound.

On her ninth album, Patty Griffin takes a left turn, incorporating bracing jazz and blues influences into her trademark contemporary folk sound. Griffin’s weathered voice is still central: Country tones seep into her melodies, and she expertly crafts poetic turns of phrase—particularly on “250,000 Miles,” a shattering exploration of maternal grief. But syncopated rhythms enliven tracks like “Gunpowder” and “There Isn’t One Way,” while “Noble Ground” boasts a raunchy blues swagger that’s wholly captivating.

“Strange Bird” from Andrew Combs’ second full-length album, *All These Dreams*, captures the warm, windswept feeling of Harry Nilsson’s version of “Everybody’s Talkin’,” with a whistle solo that reminds us just how effortless great songs make great talent sound. “Rainy Dog Song,” “Nothing to Lose,” and “Suwannee County” recall an early-‘70s country-influenced, acoustic-based pop music where the song was key. Much credit goes to Nashville producers Jordan Lehning and Skylar Wilson, who provide the songs with the spit-shine they deserve.

(p) and (c) Coin Records, Marketed and Distributed by Thirty Tigers/Red All Rights Reserved

We love the gritty guitars and fierce attitude of Steve Earle’s definitive brand of country-rock, but there’s been a dash of blues in his sound (and his soul) from the start. Earle fully embraces his inner bluesman on *Terraplane*, taking an old-school approach on tunes that tap into everything from Big Joe Williams (\"You\'re the Best Lover That I Ever Had\") to a fiddle-flecked jugband sound (\"Ain\'t Nobody\'s Daddy Now\"). But ever the iconoclast, Earle embarks on bold detours like the spoken Faustian-bargain tale \"The Tennessee Kid.”

Drake surprised everyone at the beginning of 2015 when he dropped *If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late*, an impressive 17-track release that combines the contemplative and confrontational with plenty of cavernous production from longtime collaborator Noah “40” Shebib. While Drizzy joins mentor Lil Wayne in questioning the loyalty of old friends on the woozy, Wondagurl-produced “Used To,” “Energy” is the cold-blooded highlight—on which he snarls, “I got enemies.” Later, amid the electrifying barbs of “6PM in New York,” Drake considers his own mortality and legacy: “28 at midnight. I wonder what’s next for me.”

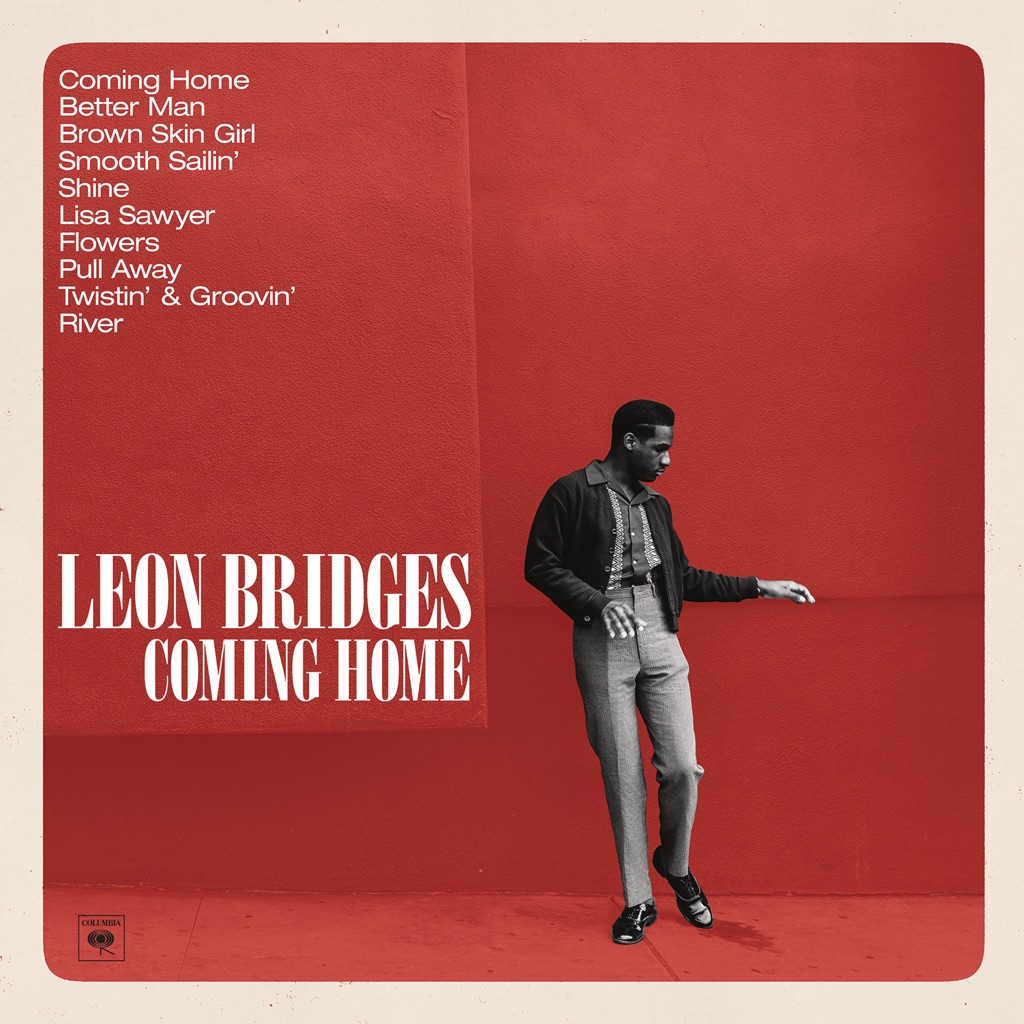

Leon Bridges’ retro-soul debut is so impressively dead-on you might wonder where he parked his time machine. Channeling the buttoned-up charm of Sam Cooke and the mellower side of Otis Redding (as well as contemporary throwbacks like Raphael Saadiq), *Coming Home* captures a moment in the early \'60s where gospel met blues and blossomed into doo-wop and soul. It was the period-perfect title track that helped Bridges gain an audience beyond his Texas hometown, but the swaying dedication to his mother, “Lisa Sawyer,” is every bit as lovely.

On Florence + The Machine’s third album, their focus is clear from the cover art. While the group\'s first two albums featured frontwoman Florence Welch posed in a theatrical side profile with her eyes closed, this one finds her eyes open and staring straight into the camera. This sense of immediacy and alertness infuses the band’s most mature, cohesive album yet, starting with propulsive opener, “Ship to Wreck.” Lush arrangements combine a rock band, strings, and brass with Welch’s volcanic, soaring voice, serving high drama on tracks like the driving “What Kind of Man” and the transcendent “Mother.”

Retreating from the garage snarl of 2013’s Monomania to the gauzy, melodic textures of 2010’s *Halcyon Digest*, Deerhunter have made their warmest record yet. The psychedelic swoops of “Breaker”, synth pulse of “Ad Astra” and lysergic funk of “Snakeskin” all expertly find the biting point between invention and accessibility. The gorgeous sonics are regularly just a salve for caustic lyrics though, and Bradford Cox’s outsider spirit rages with paranoia and self-laceration throughout.

The second album by California-based singer/songwriter Jessica Pratt is also her first conceived as an actual album. Her 2012 self-titled debut fell together by happenstance, as enough songs were completed for a full release, while 2015’s *On Your Own Love Again* was deliberately written and recorded at home, in Los Angeles and San Francisco, over the previous two years. Though it’s tempting to refer to these gorgeous, gentle songs as reminiscent of the Laurel Canyon sound, only Judee Sill in the early ‘70s came close to this level of exquisite reflection and musical sophistication, as well as a few of Pratt\'s peers like Mia Doi Todd.

Seeing the world through a Pratt's eyes is a surpassingly beautiful thing. But subtly, oh so subtly, and with such sweet flakes of humor falling. Tunes and vibe to the max.

Following his scintillating debut under the Father John Misty moniker—2012’s *Fear Fun*—journeyman singer/songwriter Josh Tillman delivers his most inspired and candid album yet. Filled with gorgeous melodies and grandiose production, *I Love You, Honeybear* finds Tillman applying his immense lyrical gifts to questions of love and intimacy. “Chateau Lobby 4 (In C for Two Virgins)” is a radiant folk tune, burnished by gilded string arrangements and mariachi horn flourishes. Elsewhere, Tillman pushes his remarkable singing voice to new heights on the album’s powerful centerpiece, “When You’re Smiling and Astride Me,” a soulful serenade of epic proportions. “I’d never try to change you,” he sings, clearly moved. “As if I could, and if I were to, what’s the part that I’d miss most?”

*A word about the refurbished deluxe edition 2xLP* With the new repressing of the deluxe, tri-colored vinyl that is now available again for purchase, we ask just one favor that will also serve as your only and final warning: The deluxe, pop-up-art-displaying jacket WILL warp the new vinyl if said vinyl is inserted back into the jacket sleeves and inserted into your record shelf. To prevent this, we ask that you keep the new LPs outside the deluxe jacket, in the separate white jackets that they ship in. Think of these 2 parts of the same deluxe package as “neighbors, not roommates” on your shelf, and your records will remain unwarped for many years to come (assuming you don’t leave them out in extreme temperatures or expose them to other forces of nature that would normally cause a record to warp…)! *The LP is cut at 45 rpm. Please adjust your turntable speed accordingly!* “I Love You, Honeybear is a concept album about a guy named Josh Tillman who spends quite a bit of time banging his head against walls, cultivating weak ties with strangers and generally avoiding intimacy at all costs. This all serves to fuel a version of himself that his self-loathing narcissism can deal with. We see him engaging in all manner of regrettable behavior. “In a parking lot somewhere he meets Emma, who inspires in him a vision of a life wherein being truly seen is not synonymous with shame, but possibly true liberation and sublime, unfettered creativity. These ambitions are initially thwarted as jealousy, self-destruction and other charming human character traits emerge. Josh Tillman confesses as much all throughout. “The album progresses, sometimes chronologically, sometimes not, between two polarities: the first of which is the belief that the best love can be is finding someone who is miserable in the same way you are and the end point being that love isn’t for anyone who isn’t interested in finding a companion to undertake total transformation with. I won’t give away the ending, but sex, violence, profanity and excavations of the male psyche abound. “My ambition, aside from making an indulgent, soulful, and epic sound worthy of the subject matter, was to address the sensuality of fear, the terrifying force of love, the unutterable pleasures of true intimacy, and the destruction of emotional and intellectual prisons in my own voice. Blammo. “This material demanded a new way of being made, and it took a lot of time before the process revealed itself. The massive, deranged shmaltz I heard in my head, and knew had to be the sound of this record, originated a few years ago while Emma and I were hallucinating in Joshua Tree; the same week I wrote the title track. I chased that sound for the entire year and half we were recording. The means by which it was achieved bore a striking resemblance to the travails, abandon and transformation of learning how to love and be loved; see and be seen. There: I said it. Blammo.” -Josh Tillman (A.K.A. Father John Misty) All LP versions are 45 rpm. All purchases come with digital downloads.

The peerless indie trio’s first LP in a decade is 33 minutes of pure, lean, honest-to-goodness rock. Corin Tucker is in full command of her howitzer of a voice on standouts like “Surface Envy.” Carrie Brownstein’s haughty punk sneer leads the glorious “A New Wave.” Janet Weiss’ masterful drumming navigates the songwriting’s hairpin tonal shifts, from the glittering “Hey Darling” to the turbulent album closer, “Fade.\" *No Cities to Love* is an electrifying step forward for one of the great American rock bands.

“We sound possessed on these songs,” says guitarist/vocalist Carrie Brownstein about Sleater-Kinney’s eighth studio album, No Cities to Love. “Willing it all–the entire weight of the band and what it means to us–back into existence.” The new record is the first in 10 years from the acclaimed trio–Brownstein, vocalist/guitarist Corin Tucker, and drummer Janet Weiss–who came crashing out of the ’90s Pacific Northwest riot grrrl scene, setting a new bar for punk’s political insight and emotional impact. Formed in Olympia, WA in 1994, Sleater-Kinney were hailed as “America’s best rock band” by Greil Marcus in Time Magazine, and put out seven searing albums in 10 years before going on indefinite hiatus in 2006. But the new album isn’t about reminiscing, it’s about reinvention–the ignition of an unparalleled chemistry to create new sounds and tell new stories. “I always considered Corin and Carrie to be musical soulmates in the tradition of the greats,” says Weiss, whose drums fuel the fire of Tucker and Brownstein’s vocal and guitar interplay. “Something about taking a break brought them closer, desperate to reach together again for their true expression.” The result is a record that grapples with love, power and redemption without restraint. “The three of us want the same thing,” says Weiss. “We want the songs to be daunting.” Produced by long-time Sleater-Kinney collaborator John Goodmanson, who helmed many of the band’s earlier albums including 1997 breakout set Dig Me Out, No Cities to Love is indeed formidable from the first beat. Lead track “Price Tag” is a pounding anthem about greed and the human cost of capitalism, establishing both the album’s melodic drive and its themes of power and powerlessness–giving voice, as Tucker says, to those who “struggle to be heard against the dominant culture or status quo.” “Bury Our Friends” has Tucker and Brownstein joining vocal forces, locking arms to defeat a pressing fear of insignificance. It’s also emblematic of the band’s give and take, and commitment to working and reworking each song until it’s as strong as it can be. “‘Bury Our Friends’ was written in the 11th hour,” says Tucker. “Carrie had her great chime-y guitar riff, but we had gone around in circles with how to make that part into a cohesive song. I think Carrie finally cracked the chorus idea and yelled, ‘Sing with me!’” “A New Wave” similarly went through many iterations during the writing process, with five or six potential choruses, before crystallizing. It enters with an insistent guitar riff, and a battle between acceptance and defiance–“Every day I throw a little party,” howls Brownstein, “but a fit would be more fitting.” The album’s meditative title track was inspired by the trend of atomic tourism and its function as a metaphor for someone enthralled and impressed by power. “That form of power, that presence, is not only destructive it’s also hollowed-out, past its prime,” says Brownstein. “The character in that song has made a ritual out of seeking structures and people in which to find strength, yet they keep coming up empty.” Sleater-Kinney’s decade apart made room for family and other fruitful collaborations, as well as an understanding of what the band’s singular chemistry demands. “Creativity is about where you want your blood to flow, because in order to do something meaningful and powerful there has to be life inside of it,” says Brownstein. “Sleater-Kinney isn’t something you can do half-assed or half-heartedly. We have to really want it. This band requires a certain desperation, a direness. We have to be willing to push because the entity that is this band will push right back.” “The core of this record is our relationship to each other, to the music, and how all of us still felt strongly enough about those to sweat it out in the basement and to try and reinvent our band,” adds Tucker. With No Cities to Love, “we went for the jugular.” –Evie Nagy

Kristin Diable has a soulful Southern vocal power that could do exquisite damage to the Dusty Springfield catalog. Her producer Dave Cobb (Sturgill Simpson) gives her a spacious, tastefully reverbed setting that lets her sing with as much or as little firepower as she needs. Female backing vocals occasionally follow her around, while usually a piano sits front and center, with drums and electric guitars added for groove and seasoning. “I’ll Make Time for You,” “Hold Steady,” and “Eyes to the Horizon” provide various angles to assess her work. “True Devotion” has a skip in its step not far removed from vintage Aretha during her early Atlantic days.