Albumism's 100 Best Albums of 2021

With 2021 nearly in the books, the time has arrived to revisit and

celebrate the plentiful past year in new music.

Source

“Sometimes I’ll be in my own space, my own company, and that’s when I\'m really content,” Little Simz tells Apple Music. “It\'s all love, though. There’s nothing against anyone else; that\'s just how I am. I like doing my own thing and making my art.” The lockdowns of 2020, then, proved fruitful for the North London MC, singer, and actor. She wrestled writer’s block, revived her cult *Drop* EP series (explore the razor-sharp and diaristic *Drop 6* immediately), and laid grand plans for her fourth studio album. Songwriter/producer Inflo, co-architect of Simz’s 2019 Mercury-nominated, Ivor Novello Award-winning *GREY Area*, was tapped and the hard work began. “It was straight boot camp,” she says of the *Sometimes I Might Be Introvert* sessions in London and Los Angeles. “We got things done pronto, especially with the pace that me and Flo move at. We’re quite impulsive: When we\'re ready to go, it’s time to go.” Months of final touches followed—and a collision between rap and TV royalty. An interest in *The Crown* led Simz to approach Emma Corrin (who gave an award-winning portrayal of Princess Diana in the drama). She uses her Diana accent to offer breathless, regal addresses that punctuate the 19-track album. “It was a reach,” Simz says of inviting Corrin’s participation. “I’m not sure what I expected, but I enjoyed watching her performance, and wrote most of her words whilst I was watching her.” Corrin’s speeches add to the record’s sense of grandeur. It pairs turbocharged UK rap with Simz at her most vulnerable and ambitious. There are meditations on coming of age in the spotlight (“Standing Ovation”), a reunion with fellow Sault collaborator Cleo Sol on the glorious “Woman,” and, in “Point and Kill,” a cleansing, polyrhythmic jam session with Nigerian artist Obongjayar that confirms the record’s dazzling sonic palette. Here, Simz talks us through *Sometimes I Might Be Introvert*, track by track. **“Introvert”** “This was always going to intro the album from the moment it was made. It feels like a battle cry, a rebirth. And with the title, you wouldn\'t expect this to sound so huge. But I’m finding the power within my introversion to breathe new meaning into the word.” **“Woman” (feat. Cleo Sol)** “This was made to uplift and celebrate women. To my peers, my family, my friends, close women in my life, as well as women all over the world: I want them to know I’ve got their back. Linking up with Cleo is always fun; we have such great musical chemistry, and I can’t imagine anyone else bringing what she did to the song. Her voice is beautiful, but I think it\'s her spirit and her intention that comes through when she sings.” **“Two Worlds Apart”** “Firstly, I love this sample; it’s ‘The Agony and the Ecstasy’ by Smokey Robinson, and Flo’s chopped it up really cool. This is my moment to flex. You had the opener, followed by a nice, smoother vibe, but this is like, ‘Hey, you’re listening to a *rap* album.’” **“I Love You, I Hate You”** “This wasn’t the easiest song for me to write, but I\'m super proud that I did. It’s an opportunity for me to lay bare my feelings on how that \[family\] situation affected me, growing up. And where I\'m at now—at peace with it and moving on.” **“Little Q, Pt. 1 (Interlude)”** “Little Q is my cousin, Qudus, on my dad\'s side. We grew up together, but then there was a stage where we didn\'t really talk for some years. No bad blood, just doing different things, so when we reconnected, we had a real heart-to-heart—and I heard about all he’d been through. It made me feel like, ‘Damn, this is a blood relative, and he almost lost his life.’ I thank God he didn’t, but I thought of others like him. And I felt it was important that his story was heard and shared. So, I’m speaking from his perspective.” **“Little Q, Pt. 2”** “I grew up in North London and \[Little Q\] was raised in South, and as much as we both grew up in endz, his experience was obviously different to mine. Being a product of an environment or system that isn\'t really for you, it’s tough trying to navigate that.” **“Gems (Interlude)”** “This is another turning point, reminding myself to take time: ‘Breathe…you\'re human. Give what you can give, but don\'t burn out for anyone. Put yourself first.’ Just little gems that everyone needs to hear once in a while.” **“Speed”** “This track sends another reminder: ‘This game is a marathon, not a sprint. So pace yourself!’ I know where I\'m headed, and I\'m taking my time, with little breaks here and there. Now I know when to really hit the gas and also when to come off a bit.” **“Standing Ovation”** “I take some time to reflect here, like, ‘Wow, you\'re still here and still going. It’s been a slow burn, but you can afford to give yourself a pat on the back.’ But as well as being in the limelight, let\'s also acknowledge the people on the ground doing real amazing work: our key workers, our healers, teachers, cleaners. If you go to a toilet and it\'s dirty, people go in from 9 to 5 and make sure that shit is spotless for you, so let\'s also say thank you.” **“I See You”** “This is a really beautiful and poetic song on love. Sometimes as artists we tend to draw from traumatic times for great art, we’re hurt or in pain, but it was nice for me to be able to draw from a place of real joy in my life for this song. Even where it sits \[on the album\]: right in the center, the heart.” **“The Rapper That Came to Tea (Interlude)”** “This title is a play on \[Judith Kerr’s\] children\'s book *The Tiger Who Came to Tea*, and this is about me better understanding my introversion. I’m just posing questions to myself—I might not necessarily have answers for them, I think it\'s good to throw them out there and get the brain working a bit.” **“Rollin Stone”** “This cut reminds me somewhat of ’09 Simz, spitting with rapidness and being witty. And I’m also finding new ways to use my voice on the second half here, letting my evil twin have her time.” **“Protect My Energy”** “This is one of the songs I\'m really looking forward to performing live. It’s a stepper, and it got me really wanting to sing, to be honest. I very much enjoy being around good company, but these days I enjoy my personal space and I want to protect that.” **“Never Make Promises (Interlude)”** “This one is self-explanatory—nothing is promised at all. It’s a short intermission to lead to the next one, but at one point it was nearly the album intro.” **“Point and Kill” (feat. Obongjayar)** “This is a big vibe! It feels very much like Nigeria to me, and Obongjayar is one of my favorites at the moment. We recorded this in my living room on a whim—and I\'m very, very grateful that he graced this song. The title comes from a phrase used in Nigeria to pick out fish at the market, or a store. You point, they kill. But also metaphorically, whatever I want, I\'m going to get in the same way, essentially.” **“Fear No Man”** “This track continues the same vibe, even more so. It declares: ‘I\'m here. I\'m unapologetically me and I fear no one here. I\'m not shook of anyone in this rap game.’” **“The Garden (Interlude)”** “This track is just amazing musically. It’s about nurturing the seeds you plant. Nurture those relationships, and everything around you that\'s holding you down.” **“How Did You Get Here”** “I want everyone to know *how* I got here; from the jump, school days, to my rap group, Space Age. We were just figuring it out, being persistent. I cried whilst recording this song; it all hit me, like, ‘I\'m actually recording my fourth album.’ Sometimes I sit and I wonder if this is all really true.” **“Miss Understood”** “This is the perfect closer. I could have ended on the last track, easily, but, I don\'t know, it\'s kind of like doing 99 reps. You\'ve done 99, that\'s amazing, but you can do one more to just make it 100, you can. And for me it was like, ‘I\'m going to get this one in there.’”

As they worked on their third album, Wolf Alice would engage in an exercise. “We liked to play our demos over the top of muted movie trailers or particular scenes from films,” lead singer and guitarist Ellie Rowsell tells Apple Music. “It was to gather a sense of whether we’d captured the right vibe in the music. We threw around the word ‘cinematic’ a lot when trying to describe the sound we wanted to achieve, so it was a fun litmus test for us. And it’s kinda funny, too. Especially if you’re doing it over the top of *Skins*.” Halfway through *Blue Weekend*’s opening track, “The Beach,” Wolf Alice has checked off cinematic, and by its (suitably titled) closer, “The Beach II,” they’ve explored several film scores’ worth of emotion, moods, and sonic invention. It’s a triumphant guitar record, at once fan-pleasing and experimental, defiantly loud and beautifully quiet and the sound of a band hitting its stride. “We’ve distilled the purest form of Wolf Alice,” drummer Joel Amey says. *Blue Weekend* succeeds a Mercury Prize-winning second album (2017’s restless, bombastic *Visions of a Life*), and its genesis came at a decisive time for the North Londoners. “It was an amazing experience to get back in touch with actually writing and creating music as a band,” bassist Theo Ellis says. “We toured *Visions of a Life* for a very long time playing a similar selection of songs, and we did start to become robot versions of ourselves. When we first got back together at the first stage of writing *Blue Weekend*, we went to an Airbnb in Somerset and had a no-judgment creative session and showed each other all our weirdest ideas and it was really, really fun. That was the main thing I’d forgotten: how fun making music with the rest of the band is, and that it’s not just about playing a gig every evening.” The weird ideas evolved during sessions with producer Markus Dravs (Arcade Fire, Coldplay, Björk) in a locked-down Brussels across 2020. “He’s a producer that sees the full picture, and for him, it’s about what you do to make the song translate as well as possible,” guitarist Joff Oddie says. “Our approach is to throw loads of stuff at the recordings, put loads of layers on and play with loads of sound, but I think we met in the middle really nicely.” There’s a Bowie-esque majesty to tracks such as “Delicious Things” and “The Last Man on Earth”; “Smile” and “Play the Greatest Hits” were built for adoring festival crowds, while Rowsell’s songwriting has never revealed more vulnerability than on “Feeling Myself” and the especially gorgeous “No Hard Feelings” (“a song that had many different incarnations before it found its place on the record,” says Oddie. “That’s a testament to the song. I love Ellie’s vocal delivery. It’s really tender; it’s a beautiful piece of songwriting that is succinct, to the point, and moves me”). On an album so confident in its eclecticism, then, is there an overarching theme? “Each song represents its own story,” says Rowsell. “But with hindsight there are some running themes. It’s a lot about relationships with partners, friends, and with oneself, so there are themes of love and anxiety. Each song, though, can be enjoyed in isolation. Just as I find solace in writing and making music, I’d be absolutely chuffed if anyone had a similar experience listening to this. I like that this album has different songs for different moods. They can rage to ‘Play the Greatest Hits,’ or they can feel powerful to ‘Feeling Myself,’ or ‘they can have a good cathartic cry to ‘No Hard Feelings.’ That would be lovely.”

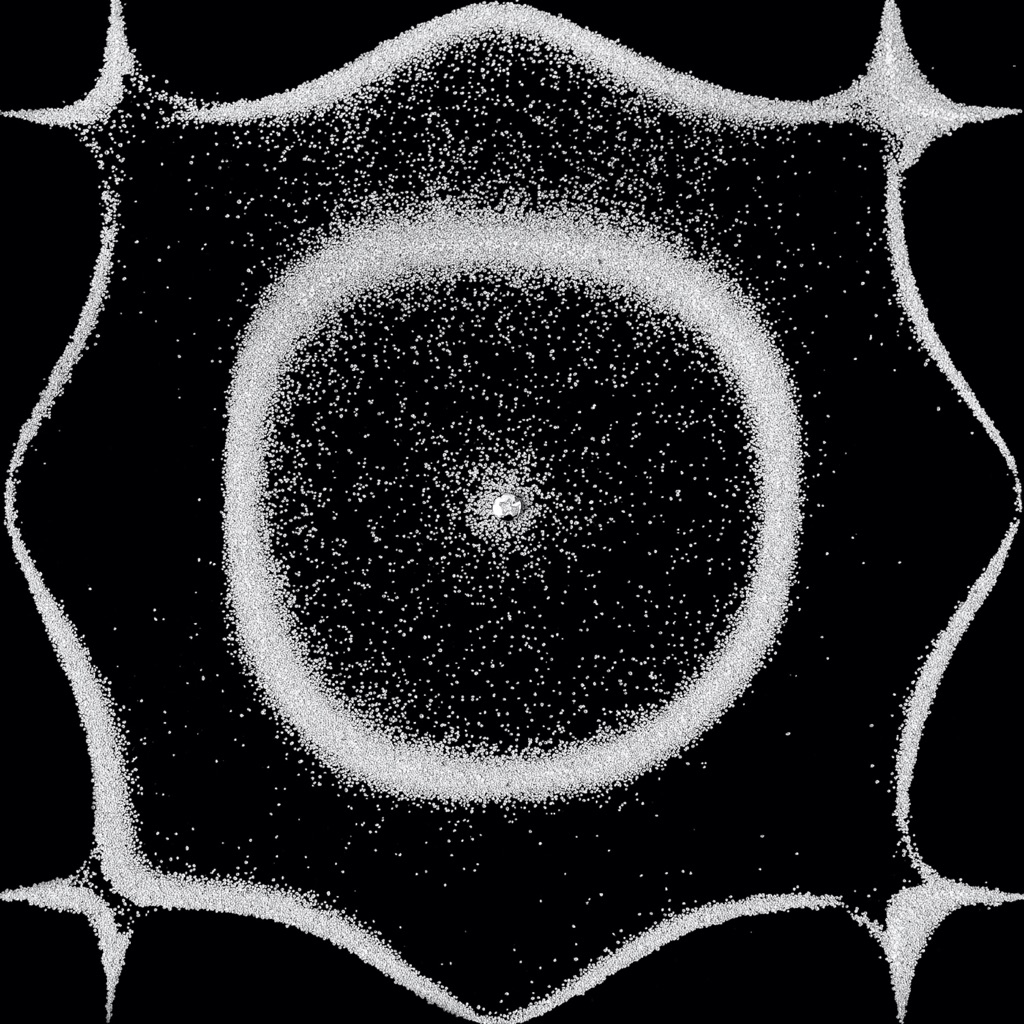

The jazz great Pharoah Sanders was sitting in a car in 2015 when by chance he heard Floating Points’ *Elaenia*, a bewitching set of flickering synthesizer etudes. Sanders, born in 1940, declared that he would like to meet the album’s creator, aka the British electronic musician Sam Shepherd, 46 years his junior. *Promises*, the fruit of their eventual collaboration, represents a quietly gripping meeting of the two minds. Composed by Shepherd and performed upon a dozen keyboard instruments, plus the strings of the London Symphony Orchestra, *Promises* is nevertheless primarily a showcase for Sanders’ horn. In the ’60s, Sanders could blow as fiercely as any of his avant-garde brethren, but *Promises* catches him in a tender, lyrical mode. The mood is wistful and elegiac; early on, there’s a fleeting nod to “People Make the World Go Round,” a doleful 1971 song by The Stylistics, and throughout, Sanders’ playing has more in keeping with the expressiveness of R&B than the mountain-scaling acrobatics of free jazz. His tone is transcendent; his quietest moments have a gently raspy quality that bristles with harmonics. Billed as “a continuous piece of music in nine movements,” *Promises* takes the form of one long extended fantasia. Toward the middle, it swells to an ecstatic climax that’s reminiscent of Alice Coltrane’s spiritual-jazz epics, but for the most part, it is minimalist in form and measured in tone; Shepherd restrains himself to a searching seven-note phrase that repeats as naturally as deep breathing for almost the full 46-minute expanse of the piece. For long stretches you could be forgiven for forgetting that this is a Floating Points project at all; there’s very little that’s overtly electronic about it, save for the occasional curlicue of analog synth. Ultimately, the music’s abiding stillness leads to a profound atmosphere of spiritual questing—one that makes the final coda, following more than a minute of silence at the end, feel all the more rewarding.

Shirley Manson struggles to explain how a Garbage record comes together. It just happens. “We don’t really speak to each other about anything, we just go into a room and what comes out is what comes out,” the singer tells Apple Music. “It’s usually a shambolic kind of journey. Somehow we end up with a record at the end of it all and we wonder how we did it. It’s a mystery, which I think is probably as it should be.” The quartet refines their chaotic process into another captivating collection of electronic-rock anthems on seventh album *No Gods No Masters*, a record that takes in snarling techno-punk, synth-pop flourishes, and atmospheric balladry across its 11 tracks (this version also includes a bonus disc of covers). Combining themes of personal turmoil with state-of-the-nation temperature-taking, it swerves from defiance to despair and back again, with Manson in exhilarating lyrical form throughout. “I was pleasantly surprised that I was able to articulate somewhat complex issues in quite a colorful way without being too heavy-handed,” she says. It all began with Manson and her bandmates—Duke Erikson, Steve Marker, and Butch Vig—in a room together in Palm Springs, California, thrashing out ideas. However, lockdown meant it had to be completed remotely. Manson says they drew on three decades’ worth of experience to get the job done. “I have to commend the whole band on being able to shape-shift and adapt,” she says. “I think one of the reasons we’ve had a long career is everybody in this band is capable of adapting.” Here, Manson unravels some of the mystery of how they do it by taking us through the album, track by track. **“The Men Who Rule the World”** “It was Butch’s call to open with this. I was like, ‘I don\'t know. I feel like maybe not.’ And then I tried a billion different ways of sequencing the record and each time I had to come back to ‘The Men Who Rule the World’—that was really pretty much the only place for it. It’s definitely a mood setter. I think it’s really good-natured, but it’s this sort of retelling of Noah’s Ark, it’s a biblical tale. It’s grand in theme, but it has a lot of humor in it, and also a lot of outrage. To me, that’s the perfect combo.” **“The Creeps”** “These lyrics tell a tale of great change in my mind. I had told myself that at the grand old age of 40, I was over the hill and I would never, ever be an artist again. I got paralyzed and depressed. I was driving along Los Feliz Boulevard, having been dropped by Interscope Records, and I saw a garage sale selling a shop-size poster of my band. I was so humiliated. But from that humiliation, I somehow managed to free myself from public perception and industry perception and expectations and focus on trying to have a good life and being creative and singing and making music and writing. My life bloomed from that point forward, so ‘The Creeps’ is important to me.” **“Uncomfortably Me”** “I think everyone can relate to that feeling of not being fully developed yet and feeling uncertain and fearful and not fitting in. Certainly, an overriding feeling my whole life is that I just never quite fit in at a dinner party, I never quite fit in a festival bill. I feel like I don’t even fit into my own band—I’m the only woman, I’m much younger, I come from Scotland and they’re American. I just feel like a permanent outsider. And the band do too, we just don’t fit in with any scene. It used to upset and frustrate me, but now I’m like, ‘It’s fucking great.’ In this world that has a plethora of bands and artists, we are here in a singular form.” **“Wolves”** “I stumbled upon this Eastern European fairy tale about the idea of two wolves that exist in each human being and wrestle with one another. You choose how you’re going to respond to a situation. Even though you think it’s just instinct, it’s actually a split-second choice. ‘Am I going to be an asshole or am I actually going to try and deal with this situation with kindness?’ It’s hard for me not to be an asshole. I want to attack; that’s just my natural state of being. If someone hurts or offends me, or makes me scared, my instinct is to destroy. As I’m getting older, I want to choose kindness instead and I want to try and control the hardcore wolf and let the kind, soft wolf out instead.” **“Waiting for God”** “I would have felt really disappointed in myself if I hadn’t touched on systemic racism on this record. It really is something that’s just become more and more pressing on me. When Trayvon Martin was murdered—this beautiful 17-year-old kid, walking home at night in a hoodie, holding a bag of Skittles in his hands and he gets shot by a white supremacist—and the way his death was treated in the press, the way that disgusting George Zimmerman got off by pleading his own fear, I think it triggered something in me. I finally started really paying attention. And I have great shame around the fact that it’s taken me this long and I’m 54 years old. But after the death of Trayvon Martin, I just saw this alarming spate of murders of Black kids in America, it was shocking. It felt like it was every day and nobody gave a shit.” **“Godhead”** “‘Godhead’ is really tongue-in-cheek, but it’s also stating the obvious, which is: If I was a male, I would be treated very differently in the world. I know this because of some of the misogyny and sexism I have endured as a professional musician. When I was in my thirties, it infuriated me to the point that I couldn’t really see straight. Now, I find it almost funny that the male is given all this gravitas in society because he’s got a silly cock and balls between his legs and women aren’t given the same amount of gravitas because we’ve got vaginas. When you start examining that patriarchal coloring of absolutely everything, that even God is sold to you as a male figure, you start to see this insidious madness that conditions males into feeling they’re more important. And it conditions females into thinking they are less important. And it’s really beginning to wear on me terribly.” **“Anonymous XXX”** “We kept on obsessing over Roxy Music and how modern they still sound, and how exciting and dangerous. The idea of danger in music seems to have been almost eradicated entirely, certainly in mainstream pop music. We were obsessing over Andy Mackay’s sax sound, and so we wrote a song using a synth sax. I wanted to write about this idea of anonymous sex. I find it so fascinating. What attracts us to having sex with people we don’t know? And why do we project all our longing onto these kinds of dalliances? It was that fascination with the hidden and the secrets and the self-deception.” **“A Woman Destroyed”** “I think this is my attempt to flip the narrative on what was happening with the Me Too movement, where I felt women were being portrayed poorly by the media. And it pissed me off that so much of the discussion was focusing on the victimization of women and what had women done to encourage their attacks on their bodies and on their freedoms. I wanted to create a female superhero who took revenge much like *A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night*, which is the Persian movie by Ana Lily Amirpour. I love that notion of this vampire taking revenge on those who hurt her. And so the song is a cinematic fantasy of revenge.” **“Flipping the Bird”** “I was inspired by *Men Explain Things to Me* by Rebecca Solnit, and this idea of suddenly being aware that a lot of the time, when you’re choosing to engage with men about certain subjects, they automatically assume that you know nothing and that they are the ones who know everything. I was also inspired by hanging out with Liz Phair and feeling a little taken over by her spirit. I wanted to sing a song like she does, where she always picks a really low register in her voice. It’s an acerbic look at the male ego and how women often choose, myself included, to form ourselves around this ego in the room in order to keep the peace and not have an angry man. We make these little compromises on the surface, but behind our eyes, there’s a whole other perception of what’s going down.” **“No Gods No Masters”** “I sing on this song, ‘No masters or gods to obey,’ and I was like, ‘Great, “no gods no masters” is the old punk slogan’ and that seemed like the perfect title for the whole record because of what was going on socially at the time. There was just so much dissent and rebellions against governments and the people really rising up, whether it was the Me Too movement, the Black Lives Matter movement—it was a glorious, beautiful thing to see. We all want good things for our babies, our families, our friends. And yet we so often then want to crush someone else’s spirit, who’s not our friend, who’s not our baby, who’s not our family. And it’s a mystery to me. And yet the world tumbles on, evolution continues. The future still holds. And that is a glorious thing. I love feeling hopeful about new generations who will eventually sort this shit out.” **“This City Will Kill You”** “This song is a goodbye and it’s an elegy, but it’s also hopeful. If you find yourself in shit, it doesn’t mean you have to stay there. It doesn’t mean your life is over. I still believe in the possibilities \[that\] you can turn pretty much anything around. I wanted that sense of comfort to be there, because it’s a dark record, it’s a difficult record. I wanted this to be, at the end of everything, like an embrace, like, ‘It’s going to be OK.’”

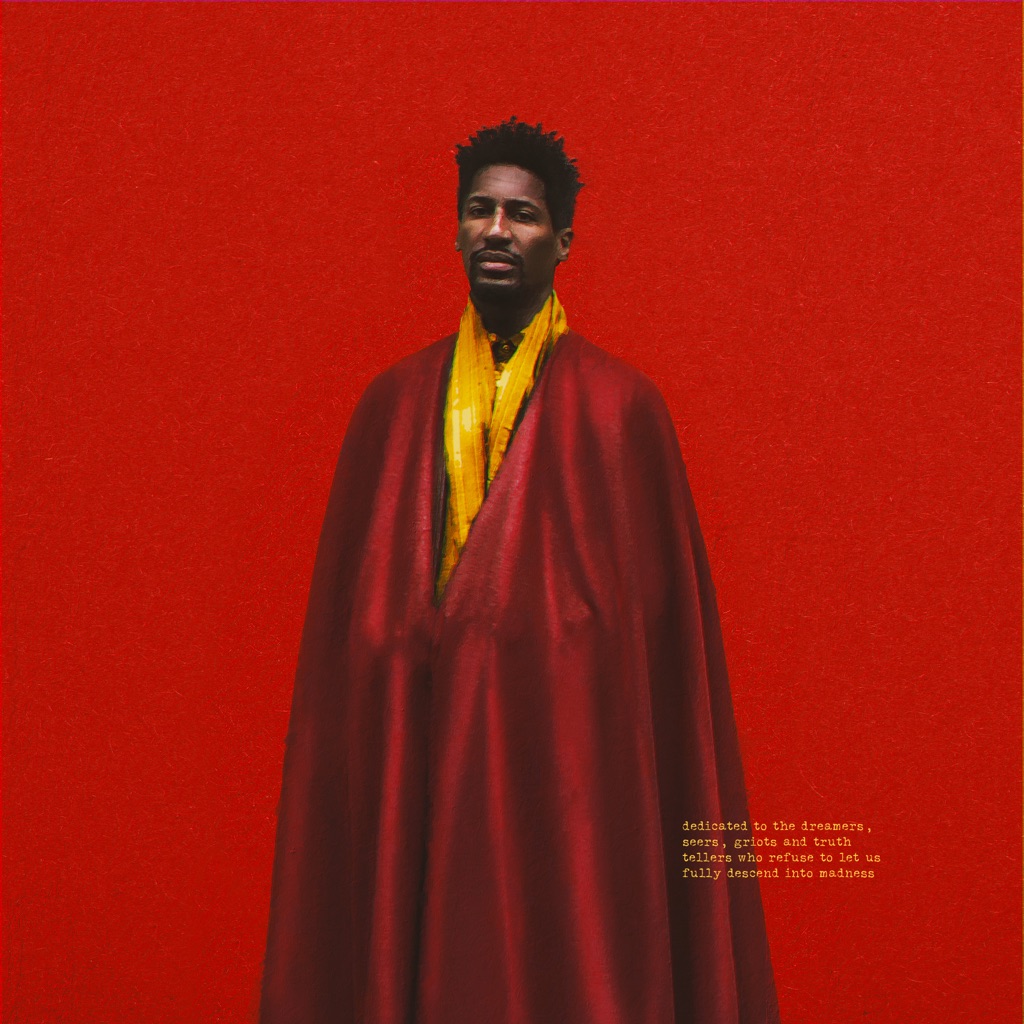

“I wanted to get a better sense of how African traditional cosmologies can inform my life in a modern-day context,” Sons of Kemet frontman Shabaka Hutchings tells Apple Music about the concept behind the British jazz group’s fourth LP. “Then, try to get some sense of those forms of knowledge and put it into the art that’s being produced.” Since their 2013 debut LP *Burn*, the Barbados-raised saxophonist/clarinetist and his bandmates (tuba player Theon Cross and drummers Tom Skinner and Eddie Hick) have been at the forefront of the new London jazz scene—deconstructing its conventions by weaving a rich sonic tapestry that fuses together elements of modal and free jazz, grime, dub, ’60s and ’70s Ethiopian jazz, and Afro-Caribbean music. On *Black to the Future*, the Mercury Prize-nominated quartet is at their most direct and confrontational with their sociopolitical message—welcoming to the fold a wide array of guest collaborators (most notably poet Joshua Idehen, who also collaborated with the group on 2018’s *Your Queen Is a Reptile*) to further contextualize the album’s themes of Black oppression and colonialism, heritage and ancestry, and the power of memory. If you look closely at the song titles, you’ll discover that each of them makes up a singular poem—a clever way for Hutchings to clue in listeners before they begin their musical journey. “It’s a sonic poem, in that the words and the music are the same thing,” Hutchings says. “Poetry isn\'t meant to be descriptive on the surface level, it\'s descriptive on a deep level. So if you read the line of poetry, and then you listen to the music, a picture should emerge that\'s more than what you\'d have if you considered the music or the line separately.” Here, Hutchings gives insight into each of the tracks. **“Field Negus” (feat. Joshua Idehen)** “This track was written in the midst of the Black Lives Matter protests in London, and it was a time that was charged with an energy of searching for meaning. People were actually starting to talk about Black experience and Black history as it related to the present, in a way that hadn\'t really been done in Britain before. The point of artists is to be able to document these moments in history and time, and be able to actually find a way of contextualizing them in a way that\'s poetic. The aim of this track is to keep that conversation going and keep the reflections happening. I\'ve been working with Joshua for 15 years and I really appreciate his perspective on the political realm. He\'s got a way of describing reality in a manner which makes you think deeply. He never loses humor and he never loses his sense of sharpness.” **“Pick Up Your Burning Cross” (feat. Moor Mother & Angel Bat Dawid)** “It started off with me writing the bassline, which I thought was going to be a grime bassline. But then in the pandemic lockdown, I added layers of horns and woodwinds. It took it completely out of the grime space and put it more in that Antillean-Caribbean atmosphere. It really showed me that there\'s a lot of intersecting links between these musics that sometimes you\'re not even aware of until you start really diving into their potential and start adding and taking away things. It was really great to actually discover that the tune had more to offer than I envisioned in the beginning. Angel Bat Dawid and Moor Mother are both on this one, and the only thing I asked them to do was to listen to the track and just give their honest interpretation of what the music brings out of them.” **“Think of Home”** “If you\'re thinking poetically, you\'ve got that frantic energy of \'Burning Cross,\' which signifies dealing with those issues of oppression. Then at the end of that process of dealing with them, you\'ve got to still remember the place that you come from. You\'ve got to think about the utopia, think about that serene tranquil place so that you\'re not consumed in the battle. It\'s not really trying to be a Caribbean track per se, but I was trying to get that feeling of when I think back to my days growing up in Barbados. This is the feeling I had when I remember the music that was made at that time.” **“Hustle” (feat. Kojey Radical)** “The title of the track links back to the title of our second album, *Lest We Forget What We Came Here to Do*. The answer to that question is to hustle. Our grandparents came and migrated to Britain, not to just be British per se, but so that they could then create a better life for themselves and their families and have the future be one with dignity and pride. I gave these words to Kojey and he said that he finds it difficult to depict these types of struggles considering that he\'s not in the present moment within the same struggle that he grew up in. He felt it was disingenuous for him to talk about the struggle. I told him that he\'s a storyteller, and storytelling isn\'t always autobiographical. His gift is to be able to tell stories for his community, and to remember that he\'s also an orator of their history regardless of where his personal journey has led him.” **“For the Culture” (feat. D Double E)** “Originally, we\'d intended D Double E to be on \'Pick Up Your Burning Cross.\' But he came into the studio and it really wasn\'t the vibe that he was in. We played him the demo of this track and his face lit up. He was like, \'Let\'s go into the studio. I know what to do.\' It was one take and that was it. I think this might be one of my favorite tunes on the album. The reason I called it \'For the Culture\' is that it puts me back into what it felt like to be a teenager in Barbados in the \'90s, going into the dance halls and really learning what it is to dance. It\'s not just all about it being hard and struggling and striving; there is that fun element of celebrating what it is to be sensual and to be alive and love music and partying and just joyfulness.” **“To Never Forget the Source”** “I gave this really short melody to the band, maybe like four bars for the melody and a very repeated bassline. We played it for about half an hour, where the drums and bass entered slowly and I played the melody again and again. The idea of this, when we recorded in the studio, is that it needs to be the vibe and spirit of how we are playing together. So it wasn\'t about stopping and starting and being anxious. We need to play it until the feeling is right. The clarinets and the flutes on this one is maybe the one I\'m most proud of in terms of adding a counterpoint line, which really offsets and emphasizes the original saxophone and tuba line.” **“In Remembrance of Those Fallen”** “The idea of \'In Remembrance of Those Fallen\' is to give homage to those people that have been fighting for liberation and freedom within all those anti-colonial movements, and remember the ongoing struggle for dignity within especially the Black world in Africa. It\'s trying to get that feeling of \'We can do this. We can go forward, regardless of what hurdles have been done and of what hurdles we\'ve encountered.\' But, musically, there\'s so many layers to this. I was excited with how, on one side, the drums are doing what you\'d describe as Afro-jazz, and on the other one, it\'s doing a really primal sound—but mixing it in a way where you feel the impact of those two contrasting drum patterns. This is at the heart of what I like about the drums in Kemet. Regardless of what they\'re doing, the end result becomes one pulsating, forward-moving machine.” **“Let the Circle Be Unbroken”** “I was listening to a lot of \[Brazilian composer\] Hermeto Pascoal while making the album, and my mind was going onto those beautiful melodies that Hermeto sometimes makes. Songs that feel like you remember them, but they\'ve got a level of harmonic intricacy, which means that there\'s something disorienting too. It\'s like you\'re hearing a nursery rhyme in a dream, hearing the basic contour of the melody, but there\'s just something below the surface that disorientates you and throws you off what you know of it. It\'s one of the only times I\'ve ever heard that midtempo soca descend into brutal free jazz.” **“Envision Yourself Levitating”** “This one also features one of my heroes on the saxophone, Kebbi Williams, who does the first saxophone solo on the track. His music has got that real New Orleans communal vibe to it. For me, this is the height of music making—when you can make music that\'s easy enough to play its constituent parts, but when it all pieces together, it becomes a complex tapestry. It\'s the first point in the album where I do an actual solo with backing parts. This is, in essence, what a lot of calypso bands do in Barbados. So when you\'ve got traditional calypso music, you\'ll get a performer who is singing their melody and then you\'ve got these horn section parts that intersect and interact with the melody that the calypsonian is singing. It\'s that idea of an interchange between the band backing the chief melodic line.” **“Throughout the Madness, Stay Strong”** “It\'s about optimism, but not an optimism where you have a smile on your face. An optimism where you\'re resigned to the place of defeat within the big spectrum of things. It\'s having to actually resign yourself to what has happened in the continued dismantling of Black civilization, and how Black people are regarded as a whole in the world within a certain light; but then understanding that it\'s part of a broader process of rising to something else, rising to a new era. Also, on the more technical side of the recording of this tune, this was the first tune that we recorded for the whole session. It\'s the first take of the first tune on the first day.” **“Black” (feat. Joshua Idehen)** “There was a point where we all got into the studio and I asked that we go into these breathing exercises where we essentially just breathe in really deeply about 30 times, and at the end of 30, we breathe out and hold it for as long as you can with nothing inside. We did one of these exercises while lying on the floor with our eyes shut in pitch blackness. I asked everyone to scream as hard as we can, really just let it out. No one could have anything in their ears apart from the track, so no one was aware of how anyone else sounded. It was complete no-self-awareness, no shyness. It\'s like a cathartic ritual to really just let it out, however you want.”

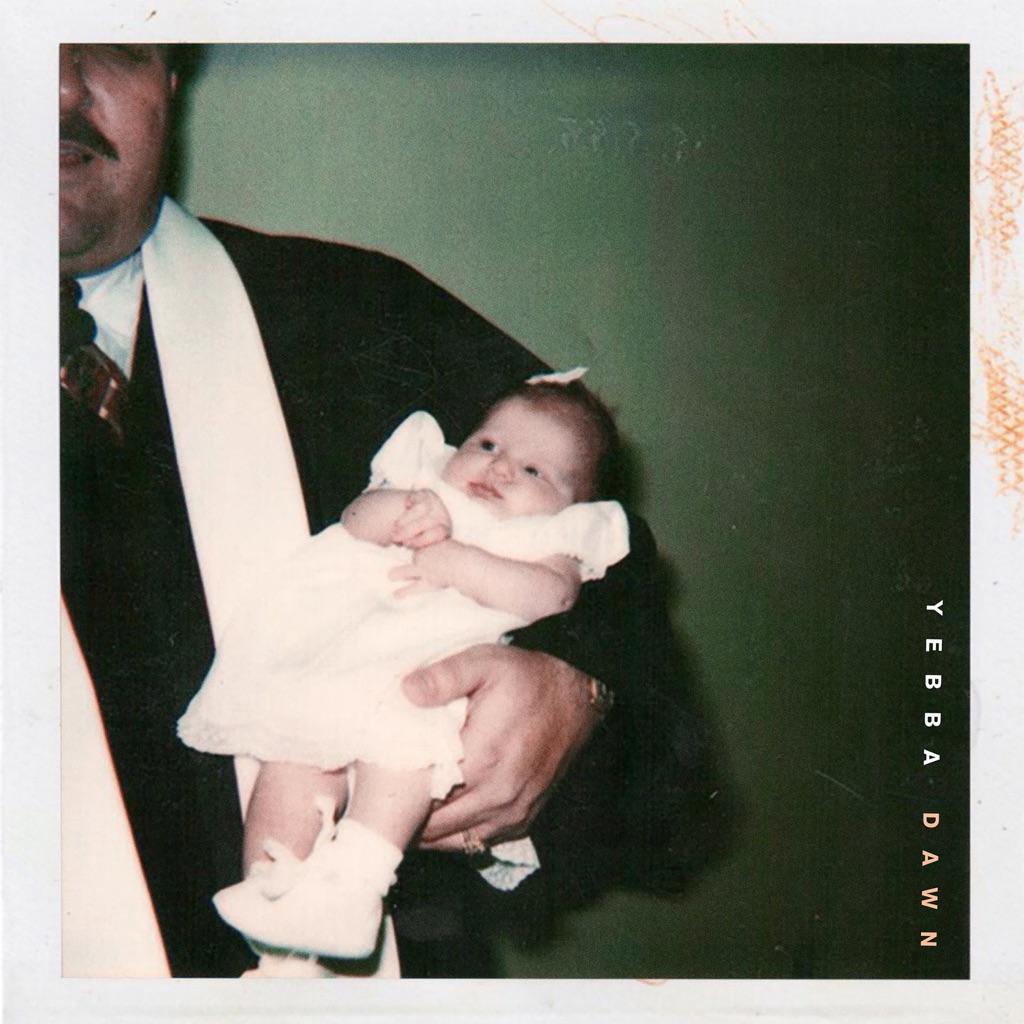

That motherhood is transformative is an understatement. For those who have the experience, it can change who they are and how they perceive the world, with fresh eyes, an open heart, and a devotion so deep it feels like being unmade. Thus, it\'s fitting that Cleo Sol’s *Mother* begins with a monument to maternal love—its abundant patience and grace for which she has a new understanding. “The train never stopped, never had time to unpack your trauma,” the British singer-songwriter croons gently on the opening track, “Don’t Let Me Fall.” “Keep fighting the world, that’s how you get love, mama.” Likewise, “Heart Full of Love” is an ode to her own child (who adorns the cover) that strives to portray both the power of that singular feeling and the gratitude that’s leveled her in its presence: “Thank you for sending me an angel straight from heaven, when my hope was gone, you made me strong...Thank you for being amazing, teaching me to hold on.” The rest of *Mother* unfurls like a letter addressed to a little one who, once removed from the safety of the womb, may come to know cruelty more often than mercy. On the piano-laden centerpiece “We Need You,” she pours into whoever may hear it a reminder of their worth, while a choir summons the divine. “We need your heart, we need your soul,” they sing, “we need your strength through this cold world, we need your voice, speak your truth.” Similar affirmations pepper the album, as Cleo imbues the lyrics with a tenderness that lands like a hug; her voice itself is so elegant and serene these songs, despite the lushness of the instrumentation, nearly resemble lullabies. It’s easy to be given to pessimism, but what she offers here is a balm, brimming with the kind of compassionate optimism that only new life can bring.

Poignant musings on loss and rebirth against a Cornish canvas.

“I don’t like to agonize over things,” Arlo Parks tells Apple Music. “It can tarnish the magic a little. Usually a song will take an hour or less from conception to end. If I listen back and it’s how I pictured it, I move on.” The West London poet-turned-songwriter is right to trust her “gut feeling.” *Collapsed in Sunbeams* is a debut album that crystallizes her talent for chronicling sadness and optimism in universally felt indie-pop confessionals. “I wanted a sense of balance,” she says. “The record had to face the difficult parts of life in a way that was unflinching but without feeling all-consuming and miserable. It also needed to carry that undertone of hope, without feeling naive. It had to reflect the bittersweet quality of being alive.” *Collapsed in Sunbeams* achieves all this, scrapbooking adolescent milestones and Parks’ own sonic evolution to form something quite spectacular. Here, she talks us through her work, track by track. **Collapsed in Sunbeams** “I knew that I wanted poetry in the album, but I wasn\'t quite sure where it was going to sit. This spoken-word piece is actually the last thing that I did for the album, and I recorded it in my bedroom. I liked the idea of speaking to the listener in a way that felt intimate—I wanted to acknowledge the fact that even though the stories in the album are about me, my life and my world, I\'m also embarking on this journey with listeners. I wanted to create an avalanche of imagery. I’ve always gravitated towards very sensory writers—people like Zadie Smith or Eileen Myles who hone in on those little details. I also wanted to explore the idea of healing, growth, and making peace with yourself in a holistic way. Because this album is about those first times where I fell in love, where I felt pain, where I stood up for myself, and where I set boundaries.” **Hurt** “I was coming off the back of writer\'s block and feeling quite paralyzed by the idea of making an album. It felt quite daunting to me. Luca \[Buccellati, Parks’ co-producer and co-writer\] had just come over from LA, and it was January, and we hadn\'t seen each other in a while. I\'d been listening to plenty of Motown and The Supremes, plus a lot of Inflo\'s production and Cleo Sol\'s work. I wanted to create something that felt triumphant, and that you could dance to. The idea was for the song to expose how tough things can be but revolve around the idea of the possibility for joy in the future. There’s a quote by \[Caribbean American poet\] Audre Lorde that I really liked: ‘Pain will either change or end.’ That\'s what the song revolved around for me.” **Too Good** “I did this one with Paul Epworth in one of our first days of sessions. I showed him all the music that I was obsessed with at the time, from ’70s Zambian psychedelic rock to MF DOOM and the hip-hop that I love via Tame Impala and big ’90s throwback pop by TLC. From there, it was a whirlwind. Paul started playing this drumbeat, and then I was just running around for ages singing into mics and going off to do stuff on the guitar. I love some of the little details, like the bump on someone’s wrist and getting to name-drop Thom Yorke. It feels truly me.” **Hope** “This song is about a friend of mine—but also explores that universal idea of being stuck inside, feeling depressed, isolated, and alone, and being ashamed of feeling that way, too. It’s strange how serendipitous a lot of themes have proved as we go through the pandemic. That sense of shame is present in the verses, so I wanted the chorus to be this rallying cry. I imagined a room full of people at a show who maybe had felt alone at some point in their lives singing together as this collective cry so they could look around and realize they’re not alone. I wanted to also have the little spoken-word breakdown, just as a moment to bring me closer to the listener. As if I’m on the other side of a phone call.” **Caroline** “I wrote ‘Caroline’ and ‘For Violet’ on the same, very inspired day. I had my little £8 bottle of Casillero del Diablo. I was taken back to when I first started writing at seven or eight, where I would write these very observant and very character-based short stories. I recalled this argument that I’d seen taken place between a couple on Oxford Street. I only saw about 30 seconds of it, but I found myself wondering all these things. Why was their relationship exploding out in the open like that? What caused it? Did the relationship end right there and then? The idea of witnessing a relationship without context was really interesting to me, and so the lyrics just came out as a stream of consciousness, like I was relaying the story to a friend. The harmonies are also important on this song, and were inspired by this video I found of The Beatles performing ‘This Boy.’ The chorus feels like such an explosion—such a release—and harmonies can accentuate that.” **Black Dog** “A very special song to me. I wrote this about my best friend. I remember writing that song and feeling so confused and helpless trying to understand depression and what she was going through, and using music as a form of personal catharsis to work through things that felt impossible to work through. I recorded the vocals with this lump in my throat because it was so raw. Musically, I was harking back to songs like ‘Nude’ and ‘House of Cards’ on *In Rainbows*, plus music by Nick Drake and tracks from Sufjan Stevens’ *Carrie & Lowell*. I wanted something that felt stripped down.” **Green Eyes** “I was really inspired by Frank Ocean here—particularly ‘Futura Free’ \[from 2016’s *Blonde*\]. I was also listening to *Moon Safari* by Air, Stereolab, Unknown Mortal Orchestra, Tirzah, Beach House, and a lot of that dreamy, nostalgic pop music that I love. It was important that the instrumental carry a warmth because the song explores quite painful places in the verses. I wanted to approach this topic of self-acceptance and self-discovery, plus people\'s parents not accepting them and the idea of sexuality. Understanding that you only need to focus on being yourself has been hard-won knowledge for me.” **Just Go** “A lot of the experiences I’ve had with toxic people distilled into one song. I wanted to talk about the idea of getting negative energy out of your life and how refreshed but also sad it leaves you feeling afterwards. That little twinge from missing someone, but knowing that you’re so much better off without them. I was thinking about those moments where you’re trying to solve conflict in a peaceful way, but there are all these explosions of drama. You end up realizing, ‘You haven’t changed, man.’ So I wanted a breakup song that said, simply, ‘No grudges, but please leave my life.’” **For Violet** “I imagined being in space, or being in a desert with everything silent and you’re alone with your thoughts. I was thinking about ‘Roads’ by Portishead, which gives me that similar feeling. It\'s minimal, it\'s dark, it\'s deep, it\'s gritty. The song covers those moments growing up when you realize that the world is a little bit heavier and darker than you first knew. I think everybody has that moment where their innocence is broken down a little bit. It’s a story about those big moments that you have to weather in friendships, and asking how you help somebody without over-challenging yourself. That\'s a balance that I talk about in the record a lot.” **Eugene** “Both ‘Black Dog’ and ‘Eugene’ represent a middle chapter between my earlier EPs and the record. I was pulling from all these different sonic places and trying to create a sound that felt warmer, and I was experimenting with lyrics that felt a little more surreal. I was talking a lot about dreams for the first time, and things that were incredibly personal. It felt like a real step forward in terms of my confidence as a writer, and to receive messages from people saying that the song has helped get them to a place where they’re more comfortable with themselves is incredible.” **Bluish** “I wanted it to feel very close. Very compact and with space in weird places. It needed to mimic the idea of feeling claustrophobic in a friendship. That feeling of being constantly asked to give more than you can and expected to be there in ways that you can’t. I wanted to explore the idea of setting boundaries. The Afrobeat-y beat was actually inspired by Radiohead’s ‘Identikit’ \[from 2016’s *A Moon Shaped Pool*\]. The lyrics are almost overflowing with imagery, which was something I loved about Adrianne Lenker’s *songs* album: She has these moments where she’s talking about all these different moments, and colors and senses, textures and emotions. This song needed to feel like an assault on the senses.” **Portra 400** “I wanted this song to feel like the end credits rolling down on one of those coming-of-age films, like *Dazed and Confused* or *The Breakfast Club*. Euphoric, but capturing the bittersweet sentiment of the record. Making rainbows out of something painful. Paul \[Epworth\] added so much warmth and muscularity that it feels like you’re ending on a high. The song’s partly inspired by *Just Kids* by Patti Smith, and that idea of relationships being dissolved and wrecked by people’s unhealthy coping mechanisms.”

“Things should change and evolve, and music is an extension of that, of the continuity of life,” Hiatus Kaiyote leader Nai Palm tells Apple Music. The Melbourne jazz/R&B/future-soul ensemble began writing their third album, *Mood Valiant*, in 2018, three years after the Grammy-nominated *Choose Your Weapon*, which featured tracks that were later sampled by artists including Kendrick Lamar, Drake, and Anderson .Paak. The process was halted when Nai Palm (Naomi Saalfield) was diagnosed with breast cancer—the same illness which had led to her mother’s death when she was 11. It changed everything about Nai Palm’s approach to life, herself, and her music—and the band began writing again from a different perspective. “All the little voices of self-doubt or validation just went away,” she says. “I didn\'t really care about the mundane things anymore, so it felt really liberating to be in a vocal booth and find joy in capturing who I am, as opposed to psychoanalyzing it. When you have nothing is when you really experience gratitude for what you have.” The album had largely been written before the pandemic hit, but when it did, they used the extra time to write even more and create something even more intricate. There are songs about unusual mating rituals in the animal kingdom, the healing power of music, the beauty and comfort of home, and the relationships we have with ourselves, those around us, and the world at large. “The whole album is about relationships without me really meaning to do that,” she says. Below, Nai Palm breaks down select lyrics from *Mood Valiant*. **“Chivalry Is Not Dead”** *“Electrons in the air on fire/Lightning kissing metal/Whisper to the tiny hairs/Battery on my tongue/Meteor that greets Sahara/We could get lost in static power”* “The first couple of verses are relating to bizarre mating rituals in the animal kingdom. It’s about reproduction and creating life, but I wanted to expand on that. Where else is this happening in nature that isn’t necessarily two animals? The way that lightning is attracted to metal, a conductor for electricity. When meteors hit the sand, it\'s so hot that it melts the sand and it creates this crazy kryptonite-looking glass. So it\'s about the relationship of life forces engaging with each other and creating something new, whether that\'s babies or space glass.” **“Get Sun”** *“Ghost, hidden eggshell, no rebel yell/Comfort in vacant waters/And I awake, purging of fear/A task that you wear/Dormant valiance, it falls”* “‘Get Sun’ is my tribute to music and what I feel it\'s supposed to do. Even when you’re closed off from the world, music can still find its way to you. ‘Ghost, hidden eggshell’ is a reference to *Ghost in the Shell*, an anime about a human soul captured in a cyborg\'s body. I feel that within the entertainment industry, but the opposite—there are people who are empty. There’s no rebellion. They’re comfortable in this vacant pool of superficial expression. I feel like there\'s a massive responsibility as a musician and as an artist to be sincere and transparent and expressive. And it takes a lot of courage but it also takes a lot of vulnerability. And ‘Dormant valiance, it falls’—from the outside, something might look quite valiant and put together, but if it\'s dormant and has no substance, it will fall, or be impermanent. And that\'s not how you make timeless art. Maybe it\'ll entertain people for three seconds but it will be gone.” **“Hush Rattle”** *“Iwêi, Rona”* “When I was in Brazil, I spent 10 days with the Varinawa tribe in the Amazon and it changed my life. On my last day there, all the women got together and sang for me in their language, Varinawa, and let me record it. There were about 20 women; they\'ll sing a phrase and when they get to the last note, they hold it for as long as they can and they all drop off at different points. It was just so magical. So we\'ve got little samples of that throughout the song, but the lyrics that I\'m singing were taught to me: ‘Iwêi,’ which means ‘I love you,’ and ‘Rona,’ which means ‘I will always miss you.’ It’s a love letter to the people that I met there.” **“Rose Water”** *“My hayati, leopard pearl in the arms of my lover/I draw your outline with the scent of amber”* “There’s an Arabic word here: *hayati*. The word *habibi* is like ‘You’re my love,’ but to say ‘my hayati’ means you\'re *more* than my love—you\'re my life. One of my dear friends is Lebanese. He’s 60, but maybe he\'s 400, we don\'t know. He’s the closest thing to a father that I\'ve had since being an orphan. He makes me this beautiful amber perfume; it’s like a resin, made with beeswax. There’s musk and oils he imports from Dubai and Syria. So it’s essentially a lullaby love song that uses these opulent, elegant elements from Middle Eastern culture that I\'ve been exposed to through the people that I love.” **“Red Room”** *“I got a red room, it is the red hour/When the sun sets in my bedroom/It feels like I\'m inside a flower/It feels like I\'m inside my eyelids/And I don\'t want to be anywhere but here”* “I used to live in an old house; the windows were colored red, like leadlight windows. And whenever the sun set, the whole room would glow for an hour. It\'s such a simple thing, but it was so magic to me. This one, for me, is about when you close your eyes and you look at the sun and it\'s red. You feel like you\'re looking at something, but really it\'s just your skin. It’s one of those childlike quirks everyone can relate to.” **“Sparkle Tape Break Up”** *“No, I can’t keep on breaking apart/Grow like waratah”* “It’s a mantra. I’m not going to let little things get to me. I\'m not going to start self-loathing. I\'m going to grow like this resilient, beautiful fucking flower. I\'ve made it a life goal to try to at least be peaceful with most people, for selfish reasons—so that I don\'t have to carry that weight. Songs like this have really helped me to formulate healthy coping mechanisms.” **“Stone or Lavender”** *“Belong to love/Please don’t bury us unless we’re seeds/Learn to forgive/You know very well it’s not easy/Who are they when they meet?/Stone or lavender/Before the word is ever uttered/Was your leap deeper?”* “‘Please don\'t bury us unless we\'re seeds’ is a reference to a quote: ‘They tried to bury us, they didn\'t know we were seeds.’ That visual is so fucking powerful. It’s saying, ‘Please don\'t try to crush the human spirit, because all life has the potential to grow, belong to love.’ This song is the closest to my breast cancer diagnosis stuff; it’s saying, ‘All right, who are you? What do you want from life? Who do you want to be?’ Do you emit a beautiful scent and you\'re soft and you\'re healing or are you stone? Before anyone\'s even exchanged anything, before a word is ever uttered, your energy introduces you.” **“Blood and Marrow”** *“Not a speck of dust on chrysanthemum/Feather on the breath of the mother tongue”* “I think is one of the most poetic things I\'ve ever written; it\'s maybe the thing I\'m most proud of lyric-wise. The first lyric is a reference to a Japanese poet called Bashō. I wanted to use this reference because when my bird Charlie died—I had him for 10 years, he was a rescue and he was my best friend—we were watching *Bambi* on my laptop. He was sitting on my computer, and we got halfway through and he died. The song is my ode to Charlie and to beauty in the world.”

“It happened by accident,” Halsey tells Apple Music of their fourth full-length. “I wasn\'t trying to make a political record, or a record that was drowning in its own profundity—I was just writing about how I feel. And I happen to be experiencing something that is very nuanced and very complicated.” Written while they were pregnant with their first child, *If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power* finds the pop superstar sifting through dark thoughts and deep fears, offering a picture of maternity that fully acknowledges its emotional and physical realities—what it might mean for one’s body, one’s sense of purpose and self. “The reason that the album has sort of this horror theme is because this experience, in a way, has its horrors,” Halsey says. “I think everyone who has heard me yearn for motherhood for so long would have expected me to write an album that was full of gratitude. Instead, I was like, ‘No, this shit is so scary and so horrifying. My body\'s changing and I have no control over anything.’ Pregnancy for some women is a dream—and for some people it’s a fucking nightmare. That\'s the thing that nobody else talks about.” To capture a sound that reflected the album’s natural sense of conflict, Halsey reached out to Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross. “I wanted cinematic, really unsettling production,” they say. “They wanted to know if I was willing to take the risk—I was.” A clear departure from the psychedelic softness of 2020’s *Manic*, the album showcases their influence from the start: in the negative space and 10-ton piano notes of “The Tradition,” the smoggy atmospherics of “Bells in Santa Fe,” the howling guitars of “Easier Than Lying,” the feverish synths of “I am not a woman, I’m a god.” Lyrically, Halsey says, it’s like an emptying of her emotional vault—“expressions of guilt or insecurity, stories of sexual promiscuity or self-destruction”—and a coming to terms with who they have been before becoming responsible for someone else; its fury is a response to an ancient dilemma, as they’ve experienced it. “I think being pregnant in the public eye is a really difficult thing, because as a performer, so much of your identity is predicated on being sexually desirable,” they say. “Socially, women have been reduced to two categories: You are the Madonna or the whore. So if you are sexually desirable or a sexual being, you\'re unfit for motherhood. But as soon as you are motherly or maternal and somebody does want you as the mother of their child, you\'re unfuckable. Those are your options; those things are not compatible, and they haven’t been for centuries.” But there are feelings of resolution as well. Recorded in conjunction with the shooting of a companion film, *If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power* is an album that’s meant to document Halsey’s transformation. And at its conclusion is “Ya’aburnee”—Arabic for “you bury me”—a sparse love song to both their baby and partner. Just the sound of their voice and a muted guitar, it’s one of the most powerful songs Halsey has written to date. “I start this journey with ‘Okay, fine—if I can\'t have love, then I want power,’” they say. “If I can\'t have a relationship, I\'m going to work. If I can\'t be loved interpersonally, I\'m going to be loved by millions on the internet, or I\'m going to crave attention elsewhere. I\'m so steadfast with this mentality, and then comes this baby. The irony is that the most power I\'ve ever had is in my agency, being able to choose. You realize, by the end of the record, I chose love.”

Saint Etienne’s 10th studio album wasn’t supposed to sound like this. By early 2020, Bob Stanley, Pete Wiggs, and Sarah Cracknell had almost completed a different set of songs. But as lockdown took hold, there was no way to mix them and work paused. While they waited, the trio picked up an idea that was easier to explore from their own homes, one first investigated on 2018’s Christmas giveaway *Surrey North EP*. A few years earlier, Stanley had become drawn to vaporwave, a sound he’d found on YouTube. Bedroom producers were warping and tranquilizing ’80s R&B and setting it to images of abandoned buildings. The hazy sense of nostalgia intrigued Stanley. “The music that gets sampled and images that get used are American or Japanese,” he tells Apple Music. “So, we thought, ‘What if we use British imagery and samples to try to evoke a period in recent British history?’” They settled on 1997 to 2001, a period beginning with the installation of the Labour government and ending with 9/11. It felt like the last time Britain had been buoyed by widespread optimism and was an age that people were increasingly looking back on with yearning. “A lot of the problems we have at the moment, like social media, barely existed,” says Stanley. “The internet barely existed. The climate catastrophe—everyone knew it was possibly going to happen, but no one realized it would accelerate as fast as it has.” Exchanging files and thoughts across email and video calls, the trio foraged samples from the era’s R&B and pop, stretching and reshaping them into eight hypnotic pieces full of summery warmth and reflection. Melodies take hold slowly but doggedly, melancholy occasionally draws in like evening shade, and a gauzy sense of reverie acknowledges how nostalgia can blur details. “The whole point is memory is a very unreliable narrator,” says Stanley. “Every period has its grimness but, with the ’90s, it’s easy to see how people are focusing on the positivity. When we were teenagers, we really looked back at the ’60s and thought what an amazing period that was. But what we were looking at was The Monkees rather than people being lynched in the South.” Here, Stanley guides us along a journey through a half-remembered past, track by track. **“Music Again”** “It’s basically Pete’s work. We just found the samples together and he extended that and made it into a hypnotic, repetitive pattern, and Sarah wrote her lyric over the top. I like the fact that when I’ve mentioned that there’s a Honeyz sample \[‘Love of a Lifetime’\], people are like ‘obscure R&B band’ or whatever. But they obviously weren’t. At the time, they were all over Radio 2; I think they had a couple of Top 10 hits. We really wanted it to be something you might remember hearing, so it might actually jog a genuine memory from the time. So, the samples \[on the album\] were all from mainstream acts, just not the most obvious songs.” **“Pond House”** “\[The sampled track, Natalie Imbruglia’s ‘Beauty on the Fire’\] got in the Top 30. With a lot of the samples, we were listening to albums from that period and just hearing if there was a snippet of something that we could use and expand. It’s almost like trying out a new instrument, trying out a guitar pedal, just seeing if there was something we could do with it. We were looking for good productions from the time, relatively smooth. I have playlists of all the ones that we never ended up using. There’s a song called ‘Sky’ by Sonique, a couple of Jamelia things—‘Antidote,’ ‘Life.’ Maybe we’ll use them in the future. Mel B’s solo stuff, Martine McCutcheon, Lutricia McNeal.” **“Fonteyn”** “\[The sample is\] a Lighthouse Family song, but it’s not the biggest hit, ‘Lifted’; it’s a relatively minor single \[‘Raincloud’\]. I remember hearing them on Radio 2 at the time, and I always really liked the bottom end of the piano working as a bassline, so that’s what we used.” **“Little K”** “We were just going back and forth, but basically Pete was sending us things that were essentially finished. It was like, ‘Well, this is terrific.’ Then Sarah would write lyrics and come up with the topline, then he’d fit them in and cut it up a bit like he did here on ‘Little K.’” **“Blue Kite”** “Pete did this in his studio at home. It was using bits of our own songs, from the early ’90s I think. That kind of abstraction reminds me of My Bloody Valentine, even though there’s no obvious guitars on it. I think it’s sad they never made another album 18 months after *Loveless*. Because I remember Colm, the drummer, was getting really into jungle, and I think they probably recorded stuff. I was thinking, ‘Wow, where’s this going to go?’ Then they just don’t make a record for 20-odd years instead. There were so many directions you could go in the early ’90s and so much music being made where you could take inspiration from it, from contemporary stuff. I think that really gave us a palette that we could use, as well as stuff from the past that we already liked—psychedelia, Northern Soul, or whatever.” **“I Remember It Well”** “I worked with a guy called Gus Bousfield, who does a lot of TV and film work. He’s an engineer, producer, and a multi-instrumentalist. That’s the kind of person I need to work with because I can barely play ‘Chopsticks.’ It’s great to have someone who can do everything you want. Gus recorded \[the sampled conversations here\] in an indoor market in Bradford. They’re heavily distorted and it sounds like human language, but you really can’t work out a single word. He plays guitar on this, which has a slight *Twin Peaks* feel.” **“Penlop”** “I think this probably had the most time spent on it. Pete did a version that was about eight minutes long. It got more distorted towards the end. I just love the way it has a part where it drops down, then comes crashing in. And then it goes up another level after that.” **“Broad River”** “The piano part is the intro to a Tasmin Archer song \[‘Ripped Inside’\]. That’s all we took from that, I think, a bar of piano or whatever, two bars. It’s funny because a lot of people have said, ‘Oh, this is the first time you did sampling since \[1993 album\] *So Tough*.’ And it isn’t. I suppose we’ve just not used it as obviously. There’s plenty of things we’ve recorded over the years which have samples on them, but you can take a bit of an existing song and make something completely new, with a completely new atmosphere. I think this is one of the cases, because I love the way it sounds on ‘Broad River’ and the Tasmin Archer song is obviously a fair bit darker.”

*Pink Noise*, Laura Mvula’s third full-length project, is a sexy album. “It really is,” Mvula tells Apple Music. “And I wanted it to be. I needed it to be.” Having felt boxed in by the success of her first two records, what she calls the “serious music” of 2013 debut *Sing to the Moon* and 2016’s *The Dreaming Room*, the UK singer-songwriter allowed herself to “paint using more colors than perhaps I let myself use before,” resulting in a vibrant, ’80s-influenced soundscape, shot through with rediscovered confidence and unabashed desire. Indebted to the era of MTV icons—Michael and Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston, Prince—this is sophisticated, luxurious, kinetic pop music. It demands that you dance. Mvula is deeply respected as an artist—classically trained, nominated twice for the Mercury Prize, the recipient of an Ivor Novello award—but *Pink Noise*, by deliberate design, presents her as not just a talent, but a superstar. “I had gotten so comfortable with everything being so focused on the music as its own thing, and somehow I was sort of separate from that,” she says. “This time I wanted to be front and center.” Here, Mvula walks us through *Pink Noise*, track by track. **“Safe Passage”** “\'Safe Passage\' was the first song I made that felt like the beginning of something. There’s a \[1988\] song by BeBe & CeCe Winans called ‘Heaven.’ And I knew I just needed to capture that sound, because that song was always played on a Sunday after church. And if I hear it now, I can smell Sunday dinner. I can go back there. I was creating the palette that this was going to be nostalgia. This body of work was going to be nostalgia, but brought into the present moment. It needed to make me and us feel good and safe and celebrated.” **“Conditional”** “I instinctively knew that ‘Conditional\' was going to be the most far-left thing that I\'d written or put out to that point. I didn’t grow up with hip-hop, so discovering it now in my own world, in my own way, since I started listening to Kanye, I\'ve just been floored by his level of creativity. A lot of what he does sounds like symphonies to me. The idea that you can make something so hypnotic and rich from the simplicity of a cyclical beat. There\'s so many thousands and millions of versions of how you can manipulate just one frequency. I remember messing around with that beat and then Dann Hume, who co-produced the album, took it to another level with the sounds that we were using.” **“Church Girl”** “Chris Martin FaceTimed me to tell me that this was his standout song. I\'d done it randomly on the train. And then I wrote the chorus chords like six months later, but didn\'t really have a melody or a verse for it. But the fact that the verse and the chorus lived in two different tonalities was always going to be the thing. The shifting gears is really important to me for the story of this song and letting go of the devils, so to speak, and figuring out how to dance. It\'s like looking back as well as looking forward all at the same time.” **“Remedy”** “I wanted to offer something direct to the struggle. It was during the time where people were taking to the streets and protesting. It needed to kick the way it did, it needed to slap the way it did, because I was pissed and tired and confused. I think that\'s all in that song. It was a direct point to Janet Jackson\'s *Rhythm Nation* and that whole era. The militant-ness of it was important for me. There\'s only so many times we can have the same conversation. My people are tired.” **“Magical”** “I only used to have a verse and chorus chords for this song for so long. I hated it. I rewrote the chorus, and once the chorus came, that’s when we knew it was a game-changer. My brother, my sister, my adopted brother from another mother came through, played guitar and sang on it. And we just basically put the song to bed. I can\'t describe to you the feeling when something becomes what it is: the mystery of music-making.” **“Pink Noise”** “The simplicity of this being a dance moment meant that I needed to draw, access things, tools I hadn\'t used before. I had to chip away at it slowly. It\'s not the kind of music where you play nine notes in a chord and it sounds lush. This is the kind of thing where if you put a few too many grains of whatever seasoning, it fucks the whole thing up. But you put it on and instantly you move, which is different for me. This is where the word ‘bop’ actually truly shines, because it is an actual bop.” **“Golden Ashes”** “My cry for help for anyone that feels like they suffer in silence. Which is unfortunately a universal truth, a very universal reality. I’ve always been good at crying and I’ve always been good at expressing my woes. I needed, in the midst of all this triumph, a space to do that on this record. Just towards the end where it peters out and you have this very strange dissonant harmony and the pulsating sort of circular breathing, it’s supposed to feel hypnotic, like \'Are we still here? Are we still in this moment?\' I\'m super proud of this song.” **“What Matters” (feat. Simon Neil)** “I don\'t think I\'ve said this before, but for me, this wasn\'t really going on the album. This was truly just for me, the Laura who doesn’t know what radio is, what streaming is—they don’t exist to me. It was like an afterthought, but then it became this lullaby anthem. Simon \[Neil, of Biffy Clyro\] is one of the most special humans I think I\'ll probably ever meet or work with, so reverent for music and the art of collaboration.” **“Got Me”** “I\'d been trying to pander to this picture of innocence and purity—all things that I do value on some level, but unfortunately, at a cost to ignoring a large part of who I am. I just needed a moment and an outlet to put into that. I feel like it serves a different purpose to any other song on the record. I don’t have to hide anymore in that way, and it’s really liberating.” **“Before the Dawn”** “When you are at a point where you\'re struggling and you feel like you\'re going through a moment in life where it\'s like, how on earth do you navigate this crisis? And you go back to the simple truths. My best friend said it to me first: ‘The night comes before the dawn.’ Which we all know, but it\'s just being reminded and reminding myself and singing to myself. Once I\'m in that and I reflect or meditate on that and it seeps more deeply into my subconscious, I find that I move with way more purpose and with less baggage.”

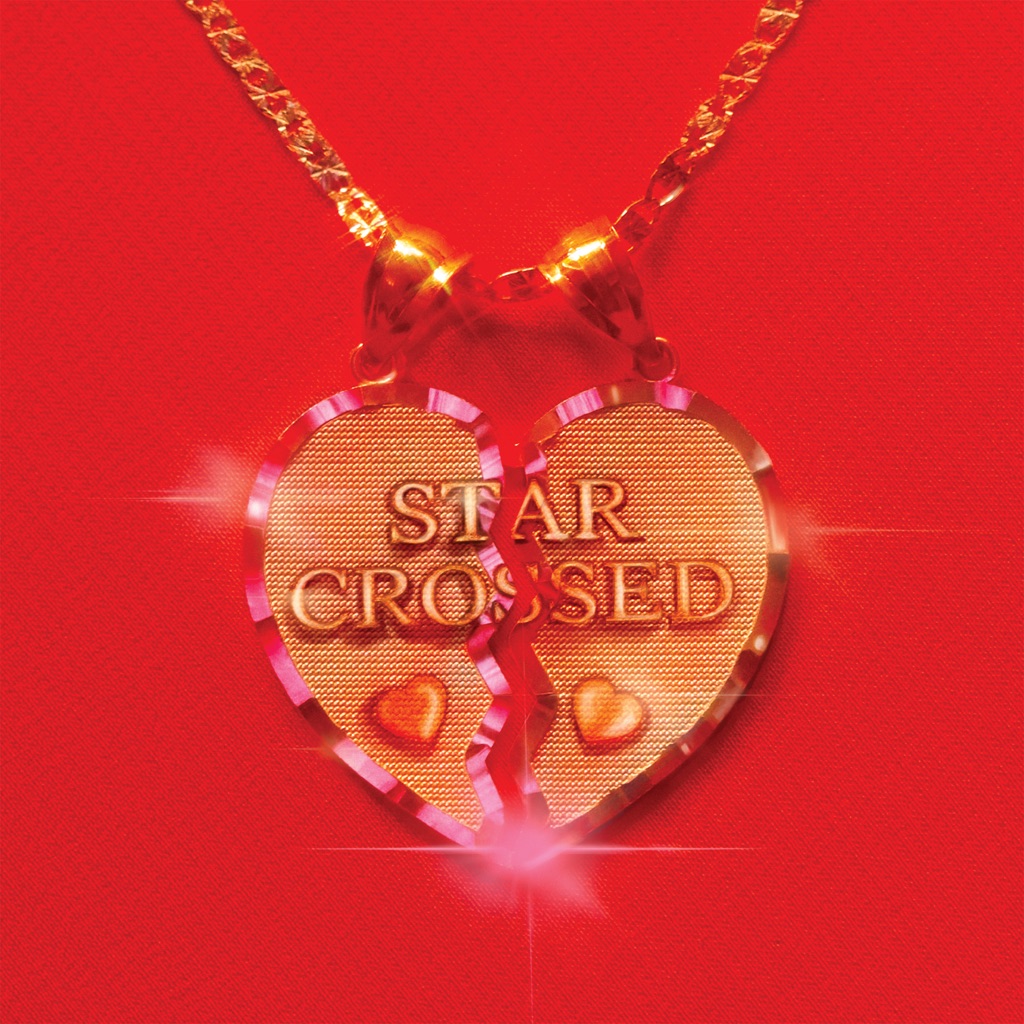

“I think that there is always reward in choosing to be the most vulnerable,” Kacey Musgraves tells Apple Music. “I have to remind myself that that\'s one of the strongest things you can do, is to be witness to being vulnerable. So I’m just trying to lean into that, and all the emotions that come with that. The whole point of it is human connection.” With 2018’s crossover breakthrough *Golden Hour*, Musgraves guided listeners through a Technicolor vision of falling in love, documenting the early stages of a romantic relationship and the blissed-out, dreamy feelings that often come with them. But the rose-colored glasses are off on *star-crossed*, which chronicles the eventual dissolution of that same relationship and the ensuing fallout. Presented as a tragedy in three acts, *star-crossed* moves through sadness, anger, and, eventually, hopeful redemption, with Musgraves and collaborators Daniel Tashian and Ian Fitchuk broadening the already spacey soundscape of *Golden Hour* into something truly deserving of the descriptors “lush” and “cinematic.” (To boot, the album releases in tandem with an accompanying film.) Below, Musgraves shares insight into several of *star-crossed*’s key tracks. **“star-crossed”** \"\[Guided psychedelic trips\] are incredible. At the beginning of this year, I was like, \'I want the chance to transform my trauma into something else, and I want to give myself that opportunity, even if it\'s painful.\' And man, it was completely life-changing in so many ways, but it also triggered this whole big bang of not only the album title, but the song \'star-crossed,\' the concept, me looking into the structure of tragedies themselves as an art form throughout time. It brought me closer to myself, the living thread that moves through all living things, to my creativity, the muse.\" **“if this was a movie..”** \"I remember being in the house, things had just completely fallen apart in the relationship. And I remember thinking, \'Man, if this was a movie, it wouldn\'t be like this at all.\' Like, I\'d hear his car, he\'d be running up the stairs and grabbing my face and say we\'re being stupid and we\'d just go back to normal. And it\'s just not like that. I think I can be an idealist, like an optimist in relationships, but I also love logic. I do well with someone who can also recognize common sense and logic, and doesn\'t get, like, lost in like these lofty emotions.\" **“camera roll”** \"I thought I was fine. I was on an upswing of confidence. I\'m feeling good about these life changes, where I\'m at; I made the right decision and we\'re moving forward. And then, in a moment of, I don\'t know, I guess boredom and weakness, I found myself just way back in the camera roll, just one night alone in my bedroom. Now I\'m back in 2018, now I\'m in 2017. And what\'s crazy is that we never take pictures of the bad times. There\'s no documentation of the fight that you had where, I don\'t know, you just pushed it a little too far.\" **“hookup scene”** \"So it was actually on Thanksgiving Day, and I had been let down by someone who was going to come visit me. And it was kind of my first few steps into exploring being a single 30-something-year-old person, after a marriage and after a huge point in my career, more notoriety. It was a really naked place. We live in this hookup culture; I\'m for it. I\'m for whatever makes you feel happy, as long as it\'s safe, doesn\'t hurt other people, fine. But I\'ve just never experienced that, the dating app culture and all that. It was a little shocking. And it made me just think that we all have flaws.\" **“gracias a la vida”** \"It was written by Violeta Parra, and I just think it\'s kind of astounding that she wrote that song. It was on her last release, and then she committed suicide. And this was basically, in a sense, her suicide note to the world, saying, \'Thank you, life. You have given me so much. You\'ve given me the beautiful and the terrible, and that has made up my song.\' Then you have Mercedes Sosa, who rerecords the song. Rereleases it. It finds new life. And then here I am. I\'m this random Texan girl. I\'m in Nashville. I\'m out in outer space. I\'m on a mushroom trip. And this song finds me in that state and inspires me to record it. It keeps reaching through time and living on, and I wanted to apply that sonically to the song, too.\"