If there is a recurring theme to be found in Phoebe Bridgers’ second solo LP, “it’s the idea of having these inner personal issues while there\'s bigger turmoil in the world—like a diary about your crush during the apocalypse,” she tells Apple Music. “I’ll torture myself for five days about confronting a friend, while way bigger shit is happening. It just feels stupid, like wallowing. But my intrusive thoughts are about my personal life.” Recorded when she wasn’t on the road—in support of 2017’s *Stranger in the Alps* and collaborative releases with Lucy Dacus and Julien Baker (boygenius) in 2018 and with Conor Oberst (Better Oblivion Community Center) in 2019—*Punisher* is a set of folk and bedroom pop that’s at once comforting and haunting, a refuge and a fever dream. “Sometimes I\'ll get the question, like, ‘Do you identify as an LA songwriter?’ Or ‘Do you identify as a queer songwriter?’ And I\'m like, ‘No. I\'m what I am,’” the Pasadena native says. “The things that are going on are what\'s going on, so of course every part of my personality and every part of the world is going to seep into my music. But I don\'t set out to make specific things—I just look back and I\'m like, ‘Oh. That\'s what I was thinking about.’” Here, Bridgers takes us inside every song on the album. **DVD Menu** “It\'s a reference to the last song on the record—a mirror of that melody at the very end. And it samples the last song of my first record—‘You Missed My Heart’—the weird voice you can sort of hear. It just felt rounded out to me to do that, to lead into this album. Also, I’ve been listening to a lot of Grouper. There’s a note in this song: Everybody looked at me like I was insane when I told Rob Moose—who plays strings on the record—to play it. Everybody was like, ‘What the fuck are you taking about?’ And I think that\'s the scariest part of it. I like scary music.” **Garden Song** “It\'s very much about dreams and—to get really LA on it—manifesting. It’s about all your good thoughts that you have becoming real, and all the shitty stuff that you think becoming real, too. If you\'re afraid of something all the time, you\'re going to look for proof that it happened, or that it\'s going to happen. And if you\'re a miserable person who thinks that good people die young and evil corporations rule everything, there is enough proof in the world that that\'s true. But if you\'re someone who believes that good people are doing amazing things no matter how small, and that there\'s beauty or whatever in the midst of all the darkness, you\'re going to see that proof, too. And you’re going to ignore the dark shit, or see it and it doesn\'t really affect your worldview. It\'s about fighting back dark, evil murder thoughts and feeling like if I really want something, it happens, or it comes true in a totally weird, different way than I even expected.” **Kyoto** “This song is about being on tour and hating tour, and then being home and hating home. I just always want to be where I\'m not, which I think is pretty not special of a thought, but it is true. With boygenius, we took a red-eye to play a late-night TV show, which sounds glamorous, but really it was hurrying up and then waiting in a fucking backstage for like hours and being really nervous and talking to strangers. I remember being like, \'This is amazing and horrible at the same time. I\'m with my friends, but we\'re all miserable. We feel so lucky and so spoiled and also shitty for complaining about how tired we are.\' I miss the life I complained about, which I think a lot of people are feeling. I hope the parties are good when this shit \[the pandemic\] is over. I hope people have a newfound appreciation for human connection and stuff. I definitely will for tour.” Punisher “I don\'t even know what to compare it to. In my songwriting style, I feel like I actually stopped writing it earlier than I usually stop writing stuff. I usually write things five times over, and this one was always just like, ‘All right. This is a simple tribute song.’ It’s kind of about the neighborhood \[Silver Lake in Los Angeles\], kind of about depression, but mostly about stalking Elliott Smith and being afraid that I\'m a punisher—that when I talk to my heroes, that their eyes will glaze over. Say you\'re at Thanksgiving with your wife\'s family and she\'s got an older relative who is anti-vax or just read some conspiracy theory article and, even if they\'re sweet, they\'re just talking to you and they don\'t realize that your eyes are glazed over and you\'re trying to escape: That’s a punisher. The worst way that it happens is like with a sweet fan, someone who is really trying to be nice and their hands are shaking, but they don\'t realize they\'re standing outside of your bus and you\'re trying to go to bed. And they talk to you for like 45 minutes, and you realize your reaction really means a lot to them, so you\'re trying to be there for them, too. And I guess that I\'m terrified that when I hang out with Patti Smith or whatever that I\'ll become that for people. I know that I have in the past, and I guess if Elliott was alive—especially because we would have lived next to each other—it’s like 1000% I would have met him and I would have not known what the fuck I was talking about, and I would have cornered him at Silverlake Lounge.” **Halloween** “I started it with my friend Christian Lee Hutson. It was actually one of the first times we ever hung out. We ended up just talking forever and kind of shitting out this melody that I really loved, literally hanging out for five hours and spending 10 minutes on music. It\'s about a dead relationship, but it doesn\'t get to have any victorious ending. It\'s like you\'re bored and sad and you don\'t want drama, and you\'re waking up every day just wanting to have shit be normal, but it\'s not that great. He lives right by Children\'s Hospital, so when we were writing the song, it was like constant ambulances, so that was a depressing background and made it in there. The other voice on it is Conor Oberst’s. I was kind of stressed about lyrics—I was looking for a last verse and he was like, ‘Dude, you\'re always talking about the Dodger fan who got murdered. You should talk about that.’ And I was like, \'Jesus Christ. All right.\' The Better Oblivion record was such a learning experience for me, and I ended up getting so comfortable halfway through writing and recording it. By the time we finished a whole fucking record, I felt like I could show him a terrible idea and not be embarrassed—I knew that he would just help me. Same with boygenius: It\'s like you\'re so nervous going in to collaborating with new people and then by the time you\'re done, you\'re like, ‘Damn, it\'d be easy to do that again.’ Your best show is the last show of tour.” Chinese Satellite “I have no faith—and that\'s what it\'s about. My friend Harry put it in the best way ever once. He was like, ‘Man, sometimes I just wish I could make the Jesus leap.’ But I can\'t do it. I mean, I definitely have weird beliefs that come from nothing. I wasn\'t raised religious. I do yoga and stuff. I think breathing is important. But that\'s pretty much as far as it goes. I like to believe that ghosts and aliens exist, but I kind of doubt it. I love science—I think science is like the closest thing to that that you’ll get. If I\'m being honest, this song is about turning 11 and not getting a letter from Hogwarts, just realizing that nobody\'s going to save me from my life, nobody\'s going to wake me up and be like, ‘Hey, just kidding. Actually, it\'s really a lot more special than this, and you\'re special.’ No, I’m going to be the way that I am forever. I mean, secretly, I am still waiting on that letter, which is also that part of the song, that I want someone to shake me awake in the middle of the night and be like, ‘Come with me. It\'s actually totally different than you ever thought.’ That’d be sweet.” **Moon Song** “I feel like songs are kind of like dreams, too, where you\'re like, ‘I could say it\'s about this one thing, but...’ At the same time it’s so hyper-specific to people and a person and about a relationship, but it\'s also every single song. I feel complex about every single person I\'ve ever cared about, and I think that\'s pretty clear. The through line is that caring about someone who hates themselves is really hard, because they feel like you\'re stupid. And you feel stupid. Like, if you complain, then they\'ll go away. So you don\'t complain and you just bottle it up and you\'re like, ‘No, step on me again, please.’ It’s that feeling, the wanting-to-be-stepped-on feeling.” Savior Complex “Thematically, it\'s like a sequel to ‘Moon Song.’ It\'s like when you get what you asked for and then you\'re dating someone who hates themselves. Sonically, it\'s one of the only songs I\'ve ever written in a dream. I rolled over in the middle of the night and hummed—I’m still looking for this fucking voice memo, because I know it exists, but it\'s so crazy-sounding, so scary. I woke up and knew what I wanted it to be about and then took it in the studio. That\'s Blake Mills on clarinet, which was so funny: He was like a little schoolkid practicing in the hallway of Sound City before coming in to play.” **I See You** “I had that line \[‘I\'ve been playing dead my whole life’\] first, and I\'ve had it for at least five years. Just feeling like a waking zombie every day, that\'s how my depression manifests itself. It\'s like lethargy, just feeling exhausted. I\'m not manic depressive—I fucking wish. I wish I was super creative when I\'m depressed, but instead, I just look at my phone for eight hours. And then you start kind of falling in love and it all kind of gets shaken up and you\'re like, ‘Can this person fix me? That\'d be great.’ This song is about being close to somebody. I mean, it\'s about my drummer. This isn\'t about anybody else. When we first broke up, it was so hard and heartbreaking. It\'s just so weird that you could date and then you\'re a stranger from the person for a while. Now we\'re super tight. We\'re like best friends, and always will be. There are just certain people that you date where it\'s so romantic almost that the friendship element is kind of secondary. And ours was never like that. It was like the friendship element was above all else, like we started a million projects together, immediately started writing together, couldn\'t be apart ever, very codependent. And then to have that taken away—it’s awful.” **Graceland Too** “I started writing it about an MDMA trip. Or I had a couple lines about that and then it turned into stuff that was going on in my life. Again, caring about someone who hates themselves and is super self-destructive is the hardest thing about being a person, to me. You can\'t control people, but it\'s tempting to want to help when someone\'s going through something, and I think it was just like a meditation almost on that—a reflection of trying to be there for people. I hope someday I get to hang out with the people who have really struggled with addiction or suicidal shit and have a good time. I want to write more songs like that, what I wish would happen.” **I Know the End** “This is a bunch of things I had on my to-do list: I wanted to scream; I wanted to have a metal song; I wanted to write about driving up the coast to Northern California, which I’ve done a lot in my life. It\'s like a super specific feeling. This is such a stoned thought, but it feels kind of like purgatory to me, doing that drive, just because I have done it at every stage of my life, so I get thrown into this time that doesn\'t exist when I\'m doing it, like I can\'t differentiate any of the times in my memory. I guess I always pictured that during the apocalypse, I would escape to an endless drive up north. It\'s definitely half a ballad. I kind of think about it as, ‘Well, what genre is \[My Chemical Romance’s\] “Welcome to the Black Parade” in?’ It\'s not really an anthem—I don\'t know. I love tricking people with a vibe and then completely shifting. I feel like I want to do that more.”

The earliest releases of Yves Tumor—the producer born Sean Bowie in Florida, raised in Tennessee, and based in Turin—arrived from a land beyond genre. They intermingled ambient synths and disembodied Kylie samples with free jazz, soul, and the crunch of experimental club beats. By 2018’s *Safe in the Hands of Love*, Tumor had effectively become a genre of one, molding funk and indie into an uncanny strain of post-everything art music. *Heaven to a Tortured Mind*, Tumor’s fourth LP, is their most remarkable transformation yet. They have sharpened their focus, sanded down the rough edges, and stepped boldly forward with an avant-pop opus that puts equal weight on both halves of that equation. “Gospel for a New Century” opens the album like a shot across the bow, the kind of high-intensity funk geared more to filling stadiums than clubs. Its blazing horns and electric bass are a reminder of Tumor’s Southern roots, but just as we’ve gotten used to the idea of them as spiritual kin to Outkast, they follow up with “Medicine Burn,” a swirling fusion of shoegaze and grunge. The album just keeps shape-shifting like that, drawing from classic soul and diverse strains of alternative rock, and Tumor is an equally mercurial presence—sometimes bellowing, other times whispering in a falsetto croon. But despite the throwback inspirations, the record never sounds retro. Its powerful rhythm section anchors the music in a future we never saw coming. These are not the sullen rhythmic abstractions of Tumor\'s early years; they’re larger-than-life anthems that sound like the product of some strange alchemical process. Confirming the magnitude of Tumor’s creative vision, this is the new sound that a new decade deserves.

Released in June 2020 as American cities were rupturing in response to police brutality, the fourth album by rap duo Run The Jewels uses the righteous indignation of hip-hop\'s past to confront a combustible present. Returning with a meaner boom and pound than ever before, rappers Killer Mike and EL-P speak venom to power, taking aim at killer cops, warmongers, the surveillance state, the prison-industrial complex, and the rungs of modern capitalism. The duo has always been loyal to hip-hop\'s core tenets while forging its noisy cutting edge, but *RTJ4* is especially lithe in a way that should appeal to vintage heads—full of hyperkinetic braggadocio and beats that sound like sci-fi remakes of Public Enemy\'s *Apocalypse 91*. Until the final two tracks there\'s no turn-down, no mercy, and nothing that sounds like any rap being made today. The only guest hook comes from Rock & Roll Hall of Famer Mavis Staples on \"pulling the pin,\" a reflective song that connects the depression prevalent in modern rap to the structural forces that cause it. Until then, it’s all a tires-squealing, middle-fingers-blazing rhymefest. Single \"ooh la la\" flips Nice & Smooth\'s Greg Nice from the 1992 Gang Starr classic \"DWYCK\" into a stomp closed out by a DJ Premier scratch solo. \"out of sight\" rewrites the groove of The D.O.C.\'s 1989 hit \"It\'s Funky Enough\" until it treadmills sideways, and guest 2 Chainz spits like he just went on a Big Daddy Kane bender. A churning sample from lefty post-punks Gang of Four (\"the ground below\") is perfectly on the nose for an album brimming with funk and fury, as is the unexpected team-up between Pharrell and Zack de la Rocha (\"JU$T\"). Most significant, however, is \"walking in the snow,\" where Mike lays out a visceral rumination on police violence: \"And you so numb you watch the cops choke out a man like me/Until my voice goes from a shriek to whisper, \'I can\'t breathe.\'\"

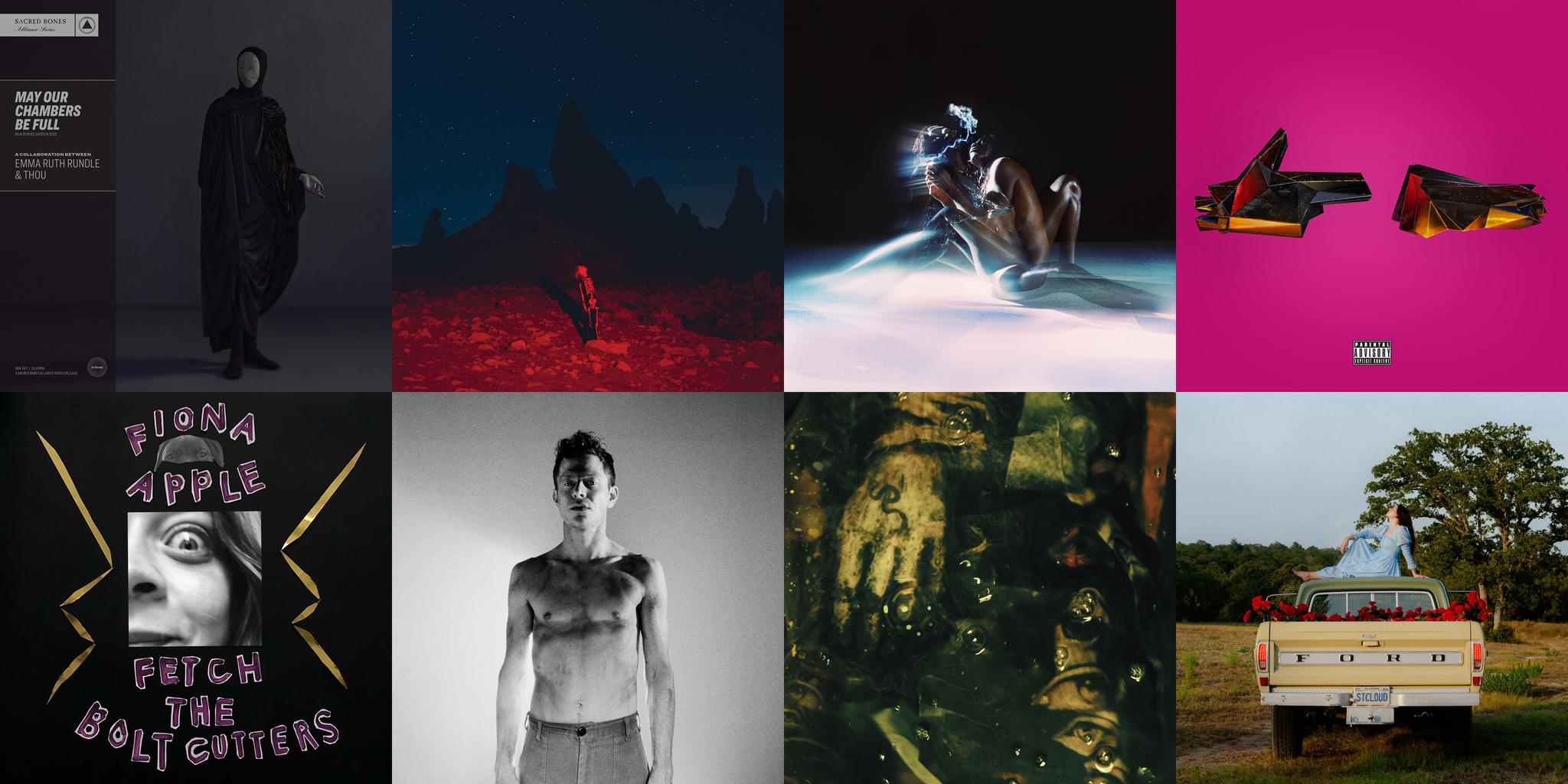

You don’t need to know that Fiona Apple recorded her fifth album herself in her Los Angeles home in order to recognize its handmade clatter, right down to the dogs barking in the background at the end of the title track. Nor do you need to have spent weeks cooped up in your own home in the middle of a global pandemic in order to more acutely appreciate its distinct banging-on-the-walls energy. But it certainly doesn’t hurt. Made over the course of eight years, *Fetch the Bolt Cutters* could not possibly have anticipated the disjointed, anxious, agoraphobic moment in history in which it was released, but it provides an apt and welcome soundtrack nonetheless. Still present, particularly on opener “I Want You to Love Me,” are Apple’s piano playing and stark (and, in at least one instance, literal) diary-entry lyrics. But where previous albums had lush flourishes, the frenetic, woozy rhythm section is the dominant force and mood-setter here, courtesy of drummer Amy Wood and former Soul Coughing bassist Sebastian Steinberg. The sparse “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” is backed by drumsticks seemingly smacking whatever surface might be in sight. “Relay” (featuring a refrain, “Evil is a relay sport/When the one who’s burned turns to pass the torch,” that Apple claims was excavated from an old journal from written she was 15) is driven almost entirely by drums that are at turns childlike and martial. None of this percussive racket blunts or distracts from Apple’s wit and rage. There are instantly indelible lines (“Kick me under the table all you want/I won’t shut up” and the show-stopping “Good morning, good morning/You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in”), all in the service of channeling an entire society’s worth of frustration and fluster into a unique, urgent work of art that refuses to sacrifice playfulness for preaching.

Mike Hadreas’ fifth LP under the Perfume Genius guise is “about connection,” he tells Apple Music. “And weird connections that I’ve had—ones that didn\'t make sense but were really satisfying or ones that I wanted to have but missed or ones that I don\'t feel like I\'m capable of. I wanted to sing about that, and in a way that felt contained or familiar or fun.” Having just reimagined Bobby Darin’s “Not for Me” in 2018, Hadreas wanted to bring the same warmth and simplicity of classic 1950s and \'60s balladry to his own work. “I was thinking about songs I’ve listened to my whole life, not ones that I\'ve become obsessed over for a little while or that are just kind of like soundtrack moments for a summer or something,” he says. “I was making a way to include myself, because sometimes those songs that I love, those stories, don\'t really include me at all. Back then, you couldn\'t really talk about anything deep. Everything was in between the lines.” At once heavy and light, earthbound and ethereal, *Set My Heart on Fire Immediately* features some of Hadreas’ most immediate music to date. “There\'s a confidence about a lot of those old dudes, those old singers, that I\'ve loved trying to inhabit in a way,” he says. “Well, I did inhabit it. I don\'t know why I keep saying ‘try.’ I was just going to do it, like, ‘Listen to me, I\'m singing like this.’ It\'s not trying.” Here, he walks us through the album track by track. **Whole Life** “When I was writing that song, I just had that line \[‘Half of my whole life is done’\]—and then I had a decision afterwards of where I could go. Like, I could either be really resigned or I could be open and hopeful. And I love the idea. That song to me is about fully forgiving everything or fully letting everything go. I’ve realized recently that I can be different, suddenly. That’s been a kind of wild thing to acknowledge, and not always good, but I can be and feel completely different than I\'ve ever felt and my life can change and move closer to goodness, or further away. It doesn\'t have to be always so informed by everything I\'ve already done.” **Describe** “Originally, it was very plain—sad and slow and minimal. And then it kind of morphed, kind of went to the other side when it got more ambient. When I took it into the studio, it turned into this way dark and light at the same time. I love that that song just starts so hard and goes so full-out and doesn\'t let up, but that the sentiment and the lyric and my singing is still soft. I was thinking about someone that was sort of near the end of their life and only had like 50% of their memories, or just could almost remember. And asking someone close to them to fill the rest in and just sort of remind them what happened to them and where they\'ve been and who they\'d been with. At the end, all of that is swimming together.” **Without You** “The song is about a good moment—or even just like a few seconds—where you feel really present and everything feels like it\'s in the right place. How that can sustain you for a long time. Especially if you\'re not used to that. Just that reminder that that can happen. Even if it\'s brief, that that’s available to you is enough to kind of carry you through sometimes. But it\'s still brief, it\'s still a few seconds, and when you tally everything up, it\'s not a lot. It\'s not an ultra uplifting thing, but you\'re not fully dragged down. And I wanted the song to kind of sound that same way or at least push it more towards the uplift, even if that\'s not fully the sentiment.” **Jason** “That song is very much a document of something that happened. It\'s not an idea, it’s a story. Sometimes you connect with someone in a way that neither of you were expecting or even want to connect on that level. And then it doesn\'t really make sense, but you’re able to give each other something that the other person needs. And so there was this story at a time in my life where I was very selfish. I was very wild and reckless, but I found someone that needed me to be tender and almost motherly to them. Even if it\'s just for a night. And it was really kind of bizarre and strange and surreal, too. And also very fueled by fantasy and drinking. It\'s just, it\'s a weird therapeutic event. And then in the morning all of that is just completely gone and everybody\'s back to how they were and their whole bundle of shit that they\'re dealing with all the time and it\'s like it never happened.” **Leave** “That song\'s about a permanent fantasy. There\'s a place I get to when I\'m writing that feels very dramatic, very magical. I feel like it can even almost feel dark-sided or supernatural, but it\'s fleeting, and sometimes I wish I could just stay there even though it\'s nonsense. I can\'t stay in my dark, weird piano room forever, but I can write a song about that happening to me, or a reminder. I love that this song then just goes into probably the poppiest, most upbeat song that I\'ve ever made directly after it. But those things are both equally me. I guess I\'m just trying to allow myself to go all the places that I instinctually want to go. Even if they feel like they don\'t complement each other or that they don\'t make sense. Because ultimately I feel like they do, and it\'s just something I told myself doesn\'t make sense or other people told me it doesn\'t make sense for a long time.” **On the Floor** “It started as just a very real song about a crush—which I\'ve never really written a song about—and it morphed into something a little darker. A crush can be capable of just taking you over and can turn into just full projection and just fully one-sided in your brain—you think it\'s about someone else, but it\'s really just something for your brain to wild out on. But if that\'s in tandem with being closeted or the person that you like that\'s somehow being wrong or not allowed, how that can also feel very like poisonous and confusing. Because it\'s very joyous and full of love, but also dark and wrong, and how those just constantly slam against each other. I also wanted to write a song that sounded like Cyndi Lauper or these pop songs, like, really angsty teenager pop songs that I grew up listening to that were really helpful to me. Just a vibe that\'s so clear from the start and sustained and that every time you hear it you instantly go back there for your whole life, you know?” **Your Body Changes Everything** “I wrote ‘Your Body Changes Everything’ about the idea of not bringing prescribed rules into connection—physical, emotional, long-term, short-term—having each of those be guided by instinct and feel, and allowed to shift and change whenever it needed to. I think of it as a circle: how you can be dominant and passive within a couple of seconds or at the exact same time, and you’re given room to do that and you’re giving room to someone else to do that. I like that dynamic, and that can translate into a lot of different things—into dance or sex or just intimacy in general. A lot of times, I feel like I’m supposed to pick one thing—one emotion, one way of being. But sometimes, I’m two contradicting things at once. Sometimes, it seems easier to pick one, even if it’s the worse one, just because it’s easier to understand. But it’s not for me.” **Moonbend** “That\'s a very physical song to me. It\'s very much about bodies, but in a sort of witchy way. This will sound really pretentious, but I wasn\'t trying to write a chorus or like make it like a sing-along song, I was just following a wave. So that whole song feels like a spell to me—like a body spell. I\'m not super sacred about the way things sound, but I can be really sacred about the vibe of it. And I feel like somehow we all clicked in to that energy, even though it felt really personal and almost impossible to explain, but without having to, everybody sort of fell into it. The whole thing was really satisfying in a way that nobody really had to talk about. It just happened.” **Just a Touch** “That song is like something I could give to somebody to take with them, to remember being with me when we couldn\'t be with each other. Part of it\'s personal and part of it I wasn\'t even imagining myself in that scenario. It kind of starts with me and then turns into something, like a fiction in a way. I wanted it to be heavy and almost narcotic, but still like honey on the body or something. I don\'t want that situation to be hot—the story itself and the idea that you can only be with somebody for a brief amount of time and then they have to leave. You don\'t want anybody that you want to be with to go. But sometimes it\'s hot when they\'re gone. It’s hard to be fully with somebody when they\'re there. I take people for granted when they\'re there, and I’m much less likely to when they\'re gone. I think everybody is like that, but I might take it to another level sometimes.” **Nothing at All** “There\'s just some energetic thing where you just feel like the circle is there: You are giving and receiving or taking, and without having to say anything. But that song, ultimately, is about just being so ready for someone that whatever they give you is okay. They could tell you something really fucked up and you\'re just so ready for them that it just rolls off you. It\'s like we can make this huge dramatic, passionate thing, but if it\'s really all bullshit, that\'s totally fine with me too. I guess because I just needed a big feeling. I don\'t care in the end if it\'s empty.” **One More Try** “When I wrote my last record, I felt very wild and the music felt wild and the way that I was writing felt very unhinged. But I didn\'t feel that way. And with this record I actually do feel it a little, but the music that I\'m writing is a lot more mature and considered. And there\'s something just really, really helpful about that. And that song is about a feeling that could feel really overwhelming, but it\'s written in a way that feels very patient and kind.” **Some Dream** “I think I feel very detached a lot of the time—very internal and thinking about whatever bullshit feels really important to me, and there\'s not a lot of room for other people sometimes. And then I can go into just really embarrassing shame. So it\'s about that idea, that feeling like there\'s no room for anybody. Sometimes I always think that I\'m going to get around to loving everybody the way that they deserve. I\'m going to get around to being present and grateful. I\'m going to get around to all of that eventually, but sometimes I get worried that when I actually pick my head up, all those things will be gone. Or people won\'t be willing to wait around for me. But at the same time that I feel like that\'s how I make all my music is by being like that. So it can be really confusing. Some of that is sad, some of that\'s embarrassing, some of that\'s dramatic, some of it\'s stupid. There’s an arc.” **Borrowed Light** “Probably my favorite song on the record. I think just because I can\'t hear it without having a really big emotional reaction to it, and that\'s not the case with a lot of my own songs. I hate being so heavy all the time. I’m very serious about writing music and I think of it as this spiritual thing, almost like I\'m channeling something. I’m very proud of it and very sacred about it. But the flip side of that is that I feel like I could\'ve just made that all up. Like it\'s all bullshit and maybe things are just happening and I wasn\'t anywhere before, or I mean I\'m not going to go anywhere after this. This song\'s about what if all this magic I think that I\'m doing is bullshit. Even if I feel like that, I want to be around people or have someone there or just be real about it. The song is a safe way—or a beautiful way—for me to talk about that flip side.”

AN IMPRESSION OF PERFUME GENIUS’ SET MY HEART ON FIRE IMMEDIATELY By Ocean Vuong Can disruption be beautiful? Can it, through new ways of embodying joy and power, become a way of thinking and living in a world burning at the edges? Hearing Perfume Genius, one realizes that the answer is not only yes—but that it arrived years ago, when Mike Hadreas, at age 26, decided to take his life and art in to his own hands, his own mouth. In doing so, he recast what we understand as music into a weather of feeling and thinking, one where the body (queer, healing, troubled, wounded, possible and gorgeous) sings itself into its future. When listening to Perfume Genius, a powerful joy courses through me because I know the context of its arrival—the costs are right there in the lyrics, in the velvet and smoky bass and synth that verge on synesthesia, the scores at times a violet and tender heat in the ear. That the songs are made resonant through the body’s triumph is a truth this album makes palpable. As a queer artist, this truth nourishes me, inspires me anew. This is music to both fight and make love to. To be shattered and whole with. If sound is, after all, a negotiation/disruption of time, then in the soft storm of Set My Heart On Fire Immediately, the future is here. Because it was always here. Welcome home.

“Place and setting have always been really huge in this project,” Katie Crutchfield tells Apple Music of Waxahatchee, which takes its name from a creek in her native Alabama. “It’s always been a big part of the way I write songs, to take people with me to those places.” While previous Waxahatchee releases often evoked a time—the roaring ’90s, and its indie rock—Crutchfield’s fifth LP under the Waxahatchee alias finds Crutchfield finally embracing her roots in sound as well. “Growing up in Birmingham, I always sort of toed the line between having shame about the South and then also having deep love and connection to it,” she says. “As I started to really get into alternative country music and Lucinda \[Williams\], I feel like I accepted that this is actually deeply in my being. This is the music I grew up on—Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, the powerhouse country singers. It’s in my DNA. It’s how I learned to sing. If I just accept and embrace this part of myself, I can make something really powerful and really honest. I feel like I shed a lot of stuff that wasn\'t serving me, both personally and creatively, and it feels like *Saint Cloud*\'s clean and honest. It\'s like this return to form.” Here, Crutchfield draws us a map of *Saint Cloud*, with stories behind the places that inspired its songs—from the Mississippi to the Mediterranean. WEST MEMPHIS, ARKANSAS “Memphis is right between Birmingham and Kansas City, where I live currently. So to drive between the two, you have to go through Memphis, over the Mississippi River, and it\'s epic. That trip brings up all kinds of emotions—it feels sort of romantic and poetic. I was driving over and had this idea for \'**Fire**,\' like a personal pep talk. I recently got sober and there\'s a lot of work I had to do on myself. I thought it would be sweet to have a song written to another person, like a traditional love song, but to have it written from my higher self to my inner child or lower self, the two selves negotiating. I was having that idea right as we were over the river, and the sun was just beating on it and it was just glowing and that lyric came into my head. I wanted to do a little shout-out to West Memphis too because of \[the West Memphis Three\]—that’s an Easter egg and another little layer on the record. I always felt super connected to \[Damien Echols\], watching that movie \[*Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills*\] as a teenager, just being a weird, sort of dark kid from the South. The moment he comes on the screen, I’m immediately just like, ‘Oh my god, that guy is someone I would have been friends with.’ Being a sort of black sheep in the South is especially weird. Maybe that\'s just some self-mythology I have, like it\'s even harder if you\'re from the South. But it binds you together.” BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA “Arkadelphia Road is a real place, a road in Birmingham. It\'s right on the road of this little arts college, and there used to be this gas station where I would buy alcohol when I was younger, so it’s tied to this seediness of my past. A very profound experience happened to me on that road, but out of respect, I shouldn’t give the whole backstory. There is a person in my life who\'s been in my life for a long time, who is still a big part of my life, who is an addict and is in recovery. It got really bad for this person—really, really bad. \[\'**Arkadelphia**\'\] is about when we weren’t in recovery, and an experience that we shared. One of the most intense, personal songs I\'ve ever written. It’s about growing up and being kids and being innocent and watching this whole crazy situation play out while I was also struggling with substances. We now kind of have this shared recovery language, this shared crazy experience, and it\'s one of those things where when we\'re in the same place, we can kind of fit in the corner together and look at the world with this tent, because we\'ve been through what we\'ve been through.” RUBY FALLS, TENNESSEE “It\'s in Chattanooga. A waterfall that\'s in a cave. My sister used to live in Chattanooga, and that drive between Birmingham and Chattanooga, that stretch of land between Alabama, Georgia, into Tennessee, is so meaningful—a lot of my formative time has been spent driving that stretch. You pass a few things. One is Noccalula Falls, which I have a song about on my first album called ‘Noccalula.’ The other is Ruby Falls. \[‘**Ruby Falls**’\] is really dense—there’s a lot going on. It’s about a friend of mine who passed away from a heroin overdose, and it’s for him—my song for all people who struggle with that kind of thing. I sang a song at his funeral when he died. This song is just all about him, about all these different places that we talked about, or that we’d spend so much time at Waxahatchee Creek together. The beginning of the song is sort of meant to be like the high. It starts out in the sky, and that\'s what I\'m describing, as I take flight, up above everybody else. Then the middle part is meant to be like this flashback but it\'s taking place on earth—it’s actually a reference to *Just Kids*, Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe. It’s written with them in mind, but it\'s just about this infectious, contagious, intimate friendship. And the end of the song is meant to represent death or just being below the surface and being gone, basically.” ST. CLOUD, FLORIDA “It\'s where my dad is from, where he was born and where he grew up. The first part of \[\'**St. Cloud**\'\] is about New York. So I needed a city that was sort of the opposite of New York, in my head. I wasn\'t going to do like middle-of-nowhere somewhere; I really did want it to be a place that felt like a city. But it just wasn’t cosmopolitan. Just anywhere America, and not in a bad way—in a salt-of-the-earth kind of way. As soon as the idea to just call the whole record *Saint Cloud* entered my brain, it didn\'t leave. It had been the name for six months or something, and I had been calling it *Saint Cloud*, but then David Berman died and I was like, ‘Wow, that feels really kismet or something,’ because he changed his middle name to Cloud. He went by David Cloud Berman. I\'m a fan; it feels like a nice way to \[pay tribute\].” BARCELONA, SPAIN “In the beginning of\* \*‘**Oxbow**’ I say ‘Barna in white,’ and ‘Barna’ is what people call Barcelona. And Barcelona is where I quit drinking, so it starts right at the beginning. I like talking about it because when I was really struggling and really trying to get better—and many times before I actually succeeded at that—it was always super helpful for me to read about other musicians and just people I looked up to that were sober. It was during Primavera \[Sound Festival\]. It’s sort of notoriously an insane party. I had been getting close to quitting for a while—like for about a year or two, I would really be not drinking that much and then I would just have a couple nights where it would just be really crazy and I would feel so bad, and it affected all my relationships and how I felt about music and work and everything. I had the most intense bout of that in Barcelona right at the beginning of this tour, and as I was leaving I was going from there to Portugal and I just decided, ‘I\'m just going to not.’ I think in my head I was like, ‘I\'m actually done,’ but I didn\'t say that to everybody. And then that tour went into another tour, and then to the summer, and then before you know it I had been sober six months, and then I was just like, ‘I do not miss that at all.’ I\'ve never felt more like myself and better. It was the site of my great realization.”

clipping.\'s second entry in their horror anthology collection follows up 2019\'s *There Existed an Addiction to Blood* by conjuring up an atmosphere that rarely allows a moment to catch your breath. William Hutson and Jonathan Snipes\' experimental production pushes their concepts even further, drawing inspiration from traditional hip-hop (\"Say the Name\" mixes a Geto Boys sample within a Chicago house music vibe, while \"Eaten Alive\" is a disorienting tribute to No Limit Records), power electronics (the blown-out blast of \"Make Them Dead\"), and EVP field samplings (the urgent \"Pain Everyday\"). These textured compositions allow Daveed Diggs\' narration to take center stage as he reconceptualizes scary-movie tropes with today\'s modern societal terrors, fleshed out by a couple of eclectic features. Cam & China flip the \"final girl\" cliché on its head on the uptempo \"’96 Neve Campbell,\" while alt-rap duo Ho99o9 relate inner city violence to auto-cannibalism on the industrial-leaning \"Looking Like Meat.\" Here the Los Angeles-based trio takes Apple Music through the record\'s many horrors. **Say the Name** William Hutson: “I had always wanted to make a track using that phrase from the Geto Boys, and we had talked about doing a Dance Mania Chicago ghetto house track about *Candyman*. I always liked that idea of a slow, plodding, more dance-oriented track, using that line repeated as a hook.” Daveed Diggs: “We had always talked about how that line is one of the scariest lines in rap music, it\'s just really good writing. Scarface does that better than anybody. What we had was this very Chicago, these really specific reference points, to me, that I had to connect. That\'s how I saw the challenge in my head, was like there\'s this very Texas lyric and this very Chicago concept. Fortunately, *Candyman* already does that for you. It\'s already about the legacy of slavery in this country. So I just got to lean into those things.” **’96 Neve Campbell (feat. Cam & China)** Jonathan Snipes: “This was actually the second thing we sent them—we made an earlier beat that had a sample that we couldn\'t clear. We wanted to make something that sounds a little more like jerk music and something that\'s a little bit more tailored for them.” WH: \"We didn\'t have our *Halloween*, *Friday the 13th* slasher song. The idea was to not have Daveed on it at all, except to rap the hooks, and just to have female rappers basically standing in for the final girl in a slasher movie. But then we liked Daveed\'s lines, we wanted him to keep rapping on it.” DD: “It felt too short with just two verses. We were like, ‘Well, put me on the phone and make me be the killer.’” WH: “There\'s a Benny the Butcher song called \'’97 Hov,\' this idea of referring to a song by a date and a person that\'s the vibe you\'re going for. So some of the suggestions were like, \'’79 Jamie Lee Curtis\' or \'’82 Heather Langenkamp.\' But then with Daveed on the phone and making a *Scream* reference, \'’96 Neve Campbell\' made more sense.” **Something Underneath** DD: “There\'s a whole batch of songs we recorded in New York while I was also doing a play, and so we\'d work all day and then I\'d go do this show at night. For a long time, there was a version of this one that I couldn\'t stand the vocal performance on. It\'s obviously a pretty technical song, and I just never nailed it and I sound tired and all of this. So it ended up being the last thing we finished.” **Make Them Dead** WH: “We did ‘Body & Blood’ and ‘Wriggle,’ which both take literal samples from power electronic artists and turned them into dance songs. The idea for this was, let\'s do a song that instead of borrows from power electronics and makes it into a dance song, let\'s try to just make a heavy, slow, plodding thing that feels like real power electronics.” DD: “When we finally settled on how this song should be lyrically, it was actually hard to write. Just trying to capture that same feel. There\'s something about power electronics that feels instructional, feels like it\'s ordering you to do something. The politics around it are varied, depending on who is making the stuff. But in order to sit within that, it had to feel political and instructional, but then that had to agree with us.” **She Bad** WH: “That\'s our witchcraft track.” JS: “Obviously, this ended up having some melodies in it, but it started as those, but it really is just field recordings and modular synths, and there isn\'t a beat so much and the melody is very obtuse in the hooks. It\'s mostly just looped and cut field recordings.” DD: “I\'ve been moving away from something that we did in a lot of our previous records, like really super visual, like precise visual storytelling that feels really cinematic, where I\'m just actually pointing the camera at things, so that was fun to try that again.” **Invocation (Interlude) (with Greg Stuart)** WH: “It\'s a joke about Alvin Lucier\'s beat pattern music, his wave songs and things like that, but done as if it was trying to summon the devil.” **Pain Everyday (with Michael Esposito)** DD: “I love this song so much. Also, I definitely learned while writing it why people don\'t write whole rap songs in 7/8. It\'s not easy. The math, the hidden math in those verses is intense. It kept breaking my brain, but now that it\'s all down, I can\'t hear it any other way, it sounds fine. But getting there was such a mindfuck.” WH: “So then the idea was it\'s in 7/8, it\'s about a lynched ghost, so the idea we had was a chase scene of the ghost of murdered victims of lynching.” **Check the Lock** WH: “This was conceived as a sequel to a song by Seagram and Scarface called ‘Sleepin in My Nikes.’ That was a rap song about extreme paranoia that I always thought was cool and felt like a horror, like an aspect of horror.” JS: “This is the one time on this album that we let ourselves do that like John Carpenter-y, creepy synth thing.” **Looking Like Meat (feat Ho99o9)** DD: “I think they reached out wanting to do a song, and this had always felt, we always wanted this to be like a posse track, kind of. This was another one that I wasn\'t going to write a voice for actually, we were going to try to find a better verse.” JS: “Which is why the hooks are all different—we were going to fill them in specifically with features, but sometimes features don\'t work out. This is like our attempt at making the more sort of aggressive, like a thing that sounds more like noise rap than we usually do.” WH: “The first thing on this beat was I bought 20 little music boxes that all played different songs, and I stuck them all to a sounding board and put contact microphones on it, and just cranked them each at the same time.” **Eaten Alive (with Jeff Parker & Ted Byrnes)** DD: “I had been in this phase of listening to Nipsey \[Hussle\] all day, every day, and all I wanted to do was figure out how to rap like that. So from his cadence perspective, it\'s like my best Nipsey impression, which we didn\'t know was going to turn into a posthumous tribute.” WH: “And the rapping was also partly a tribute, just spiritually a tribute to No Limit Records. That\'s why it\'s called \'Eaten Alive,\' which is named after a Tobe Hooper horror movie about a swamp.” **Body for the Pile (with Sickness)** WH: “It already came out \[in 2016\]. It ended up being on an Adult Swim compilation called *NOISE*. We did it with Chris Goudreau, our friend who is just a legendary noise artist called Sickness.” JS: “We always thought that would be a great song to save for a horror record, and then years went by and we weren\'t going to include it, because we thought, ‘Well, it\'s out and it\'s done.’ We looked around and I don\'t know, that comp isn\'t really anywhere and that track is hard to find, and we really like it and we thought it fit really nice. When we started putting it in the lineup of tracks and listening to it as an album, we realized it fit really nicely.” **Enlacing** WH: “The cosmic pessimism of H.P. Lovecraft is all about the horror of discovering how small you are in the universe and how uncaring the universe is. So this song was about accessing that fear by getting way too high on Molly and ketamine at the same time, then discovering Cthulhu or Azathoth as a result of getting way too fucking high.” JS: “My memory is that this was never intended to be a clipping. song, that you and I made this beat as an example of, ‘Hey, we can make normal beats.’” DD: “That Lovecraftian idea was something that we played in opposition to a lot on *Splendor & Misery*, so it was good to revisit in a way where we were actually playing into it, and also it definitely feels to me like just being way too high.” **Secret Piece** WH: “We wanted to really tie the two albums together, so the idea was to get everyone who played on any of the albums to contribute their one note. So we assembled the recordings of dawn and forests, and then almost everyone who played on either of these two albums contributed one note.” JS: “We have a habit of ending our albums with a piece of processed music or contemporary music. We ended *midcity* with a take on a Steve Reich phased loop idea, and we ended *CLPPNG* with a John Cage piece, and then *There Existed* ends with Annea Lockwood\'s \'Piano Burning.\' So we wanted something that felt like the sun was coming up at the end of the horror movie, a little bit.” WH: “That was the idea was that we were exiting, it\'s dawn in a forest. So dawn in a forest in a slasher movie or a horror movie usually means you\'re safe, right? The end of *Friday the 13th* one, the sun comes up and she\'s in the little boat, but that doesn\'t end well for her either. We did not have the jump scare at the end like *Friday the 13th*.” DD: “I pushed for it a little bit, but some people thought it was too corny.”

“My music is not as collaborative as it’s been in the past,” Jeff Parker tells Apple Music. “I’m not inviting other people to write with me. I’m more interested in how people\'s instrumental voices can fit into the ideas I’m working on.” As his career has evolved, the jazz guitarist and member of post-rock band Tortoise has become more comfortable writing compositions as a solitary exercise. While 2016\'s *The New Breed* featured a host of contributors, *Suite for Max Brown* finds the Los Angeles-based player eager to move away from the delirious funk-jazz of earlier works and towards something more unified and focused on repetition and droning harmonies. “I used to ask my collaborators to bring as much of the songwriting to the compositions as I do. Now, I’m just trying to prove to myself that I can do it on my own.” Parker handles most of the instruments on *Max Brown*, but familiar faces pop up throughout. The opening track, “Build a Nest,” features vocals from Parker’s daughter, Ruby, and “Gnarciss” includes performances from Makaya McCraven on the drums, Rob Mazurek on trumpet, and Josh Johnson on alto saxophone. Other frequenters of Parker’s orbit, like drummer Jamire Williams, appear throughout. But *Max Brown* is Parker’s record first and foremost, and the LP finds him less willing to give in to jazz’s typical demands of dynamic improvisation and community-oriented song-building. Here, Parker asserts himself as an ecstatic solo voice, where on earlier albums the soft-spoken musician may have been more willing to give way to his fellow bandmates. *Suite for Max Brown* is an ambitious sonic experiment that succeeds in its moves both big and small. “I like when music is able to enhance the environment of everyday life,” Parker says. “I would like people to be able to find themselves within the music.” Above all, *Suite for Max Brown* pays homage to the most important figures in Parker’s life. *The New Breed*, which was finished shortly after Parker’s father passed away, took its title from a store his father owned; *Max Brown* is derived from his mother’s nickname, and Parker felt an urgent desire to honor her while she was still able to hear it. “My mother has always been really supportive and super proud of the work I’ve done,” he says. “I wanted to dedicate an album to her while she’s still alive to see the results. She loves it, which means so much.” It’s an ode to his mother’s ambition, and a record that stands in awe of her achievements, even though they’re quite different from Jeff’s. “She had a stable job and collected a 401(k). My career as a musician is 180 degrees the opposite of that, but I’m still inspired by her work ethic.”

“I’m always looking for ways to be surprised,” says composer and multi-instrumentalist Jeff Parker as he explains the process, and the thinking, behind his new album, Suite for Max Brown, released via a new partnership between the Chicago–based label International Anthem and Nonesuch Records. “If I sit down at the piano or with my guitar, with staff paper and a pencil, I’m eventually going to fall into writing patterns, into things I already know. So, when I make music, that’s what I’m trying to get away from—the things that I know.” Parker himself is known to many fans as the longtime guitarist for the Chicago–based quintet Tortoise, one of the most critically revered, sonically adventurous groups to emerge from the American indie scene of the early nineties. The band’s often hypnotic, largely instrumental sound eludes easy definition, drawing freely from rock, jazz, electronic, and avant-garde music, and it has garnered a large following over the course of nearly thirty years. Aside from recording and touring with Tortoise, Parker has worked as a side man with many jazz greats, including Nonesuch labelmate Joshua Redman on his 2005 Momentum album; as a studio collaborator with other composer-musicians, including Makaya McCraven, Brian Blade, Meshell N’Degeocello, his longtime friend (and Chicago Underground ensemble co-founder) Rob Mazurek; and as a solo artist. Suite for Max Brown is informally a companion piece to The New Breed, Parker’s 2016 album on International Anthem, which London’s Observer honored as the best jazz album of the year, declaring that “no other musician in the modern era has moved so seamlessly between rock and jazz like Jeff Parker. As guitarist for Chicago post-rock icons Tortoise, he’s taken the group in new and challenging directions that have kept them at the forefront of pop creativity for the last twenty years. As of late, however, Parker has established himself as one of the most formidable solo talents in modern jazz.” Though Parker collaborates with a coterie of musicians under the group name The New Breed, theirs is by no means a conventional “band” relationship. Parker is very much a solo artist on Suite for Max Brown. He constructs a digital bed of beats and samples; lays down tracks of his own on guitar, keyboards, bass, percussion, and occasionally voice; then invites his musician friends to play and improvise over his melodies. But unlike a traditional jazz session, Parker doesn’t assemble a full combo in the studio for a day or two of live takes. His accompanists are often working alone with Parker, reacting to what Parker has provided them, and then Parker uses those individual parts to layer and assemble into his final tracks. The process may be relatively solitary and cerebral, but the results feel like in-the-moment jams—warm-hearted, human, alive. Suite for Max Brown brims with personality, boasting the rhythmic flow of hip hop and the soulful swing of jazz. “In my own music I’ve always sought to deal with the intersection of improvisation and the digital era of making music, trying to merge these disparate elements into something cohesive,” Parker explains. “I became obsessed maybe ten or fifteen years ago with making music from samples. At first it was more an exercise in learning how to sample and edit audio. I was a big hip-hop fan all my life, but I never delved into the technical aspects of making that music. To keep myself busy, I started to sample music from my own library of recordings, to chop them up, make loops and beats. I would do it in my spare time. I could do it when I was on tour—in the van or on an airplane, at a soundcheck, whenever I had spare time I was working on this stuff. After a while, as you can imagine, I had hours and hours of samples I had made and I hadn’t really done anything with them “So I made The New Breed based off these old sample-based compositions and mixed them with improvising,” he continues. “There was a lot of editing, a lot of post-production work that went into that. That’s in a nutshell how I make a lot of my music; it’s a combination of sampling, editing, retriggering audio, and recording it, moving it around and trying to make it into something cohesive—and make it music that someone would enjoy listening to. With Max Brown, it’s evolved. I played a lot of the music myself. It’s me playing as many of the instruments as I could. I engineered most it myself at home or during a residency I did at the Headlands Center for the Arts [in Sausalito, California] about a year ago.” His New Breed band-mates and fellow travelers on Max Brown include pianist-saxophonist Josh Johnson; bassist Paul Bryan, who co-produced and mixed the album with Parker; piccolo trumpet player Rob Mazurek, his frequent duo partner; trumpeter Nate Walcott, a veteran of Conor Oberst’s Bright Eyes; drummers Jamire Williams, Makaya McCraven, and Jay Bellerose, Parker’s Berklee School of Music classmate; cellist Katinka Klejin of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra; and even his seventeen-year-old daughter Ruby Parker, a student at the Chicago High School of the Arts, who contributes vocals to opening track, “Build A Nest.” Ruby’s presence at the start is fitting, since Suite for Max Brown is a kind of family affair: “That’s my mother’s maiden name. Maxine Brown. Everybody calls her Max. I decided to call it Suite for Max Brown. The New Breed became a kind of tribute to my father because he passed away while I was making the album. The New Breed was a clothing store he owned when I was a kid, a store in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where I was born. I thought it would be nice this time to dedicate something to my mom while she’s still here to see it. I wish that my father could have been around to hear the tribute that I made for him. The picture on the cover of Max Brown is of my mom when she was nineteen.” There is a multi-generational vibe to the music too, as Parker balances his contemporary digital explorations with excursions into older jazz. Along with original compositions, Parker includes “Gnarciss,” an interpretation of Joe Henderson’s “Black Narcissus” and John Coltrane’s “After the Rain” (from his 1963 Impressions album). Parker recalls, “I was drawn to jazz music as a kid. That was the first music that really resonated with me once I got heavily into music. When I was nine or ten years old, I immediately gravitated to jazz because there were so many unexpected things. Jazz led me into improvising, which led me into experimenting in a general way, into an experimental process of making music.” Coltrane is a touchstone in Parker’s musical evolution. In fact, Parker recalls, he inadvertently found himself on a new musical path one night about fifteen years ago when he was deejaying at a Chicago bar and playing ‘Trane: “I used to deejay a lot when I lived in Chicago. This was before Serrato and people deejaying with computers. I had two records on two turntables and a mixer. I was spinning records one night and for about ten minutes I was able to perfectly synch up a Nobukazu Takemura record with the first movement of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme and it had this free jazz, abstract jazz thing going on with a sequenced beat underneath. It sounded so good. That’s what I’m trying to do with Max Brown. It’s got a sequenced beat and there are musicians improvising on top or beneath the sequenced drum pattern. That’s what I was going for. Man vs machine. “It’s a lot of experimenting, a lot of trial and error,” he admits. “I like to pursue situations that take me outside myself, where the things I come up with are things I didn’t really know I could do. I always look at this process as patchwork quilting. You take this stuff and stitch it together until a tapestry forms.” —Michael Hill

Adrianne Lenker had an entire year of touring planned with her indie-folk band Big Thief before the pandemic hit. Once the tour got canceled, Lenker decided to go to Western Massachusetts to stay closer to her sister. After ideas began to take shape, she decided to rent a one-room cabin in the Massachusetts mountains to write in isolation over the course of one month. “The project came about in a really casual way,” Lenker tells Apple Music. “I later asked my friend Phil \[Weinrobe, engineer\] if he felt like getting out of the city to archive some stuff with me. I wasn\'t thinking that I wanted to make an album and share it with the world. It was more like, I just have these songs I want to try and record. My acoustic guitar sounds so warm and rich in the space, and I would just love to try and make something.” Having gone through an intense breakup, Lenker began to let her emotions flow through the therapy of writing. Her fourth solo LP, simply titled *songs* (released alongside a two-track companion piece called *instrumentals*), is modest in its choice of words, as this deeply intimate set highlights her distinct fingerpicking style over raw, soul-searching expressions and poignant storytelling motifs. “I can only write from the depths of my own experiences,” she says. “I put it all aside because the stuff that became super meaningful and present for me was starting to surface, and unexpectedly.” Let Lenker guide you through her cleansing journey, track by track. **two reverse** “I never would have imagined it being the first track, but then as I listened, I realized it’s got so much momentum and it also foreshadows the entire album. It\'s one of the more abstract ones on the record that I\'m just discovering the meaning of it as time goes on, because it is a little bit more cryptic. It\'s got my grandmother in there, asking the grandmother spirit to tell stories and being interested in the wisdom that\'s passed down. It\'s also about finding a path to home and whatever that means, and also feeling trapped in the jail of the body or of the mind. It\'s a multilayered one for me.” **ingydar** “I was imagining everything being swallowed by the mouth of time, and just the cyclical-ness of everything feeding off of everything else. It’s like the simple example of a body decomposing and going into the dirt, and then the worm eating the dirt, and the bird eating the worm, and then the hawk or the cat eating the bird. As something is dying, something is feeding off of that thing. We\'re simultaneously being born and decaying, and that is always so bewildering to me. The duality of sadness and joy make so much sense in that light. Feeling deep joy and laughter is similar to feeling like sadness in a way and crying. Like that Joni Mitchell line, \'Laughing and crying, it\'s the same release.\'” **anything** “It\'s a montage of many different images that I had stored in my mind from being with this person. I guess there\'s a thread of sweetness through it all, through things as intense as getting bit by a dog and having to go to the ER. It\'s like everything gets strung together like when you\'re falling in love; it feels like when you\'re in a relationship or in that space of getting to know someone. It doesn\'t matter what\'s happening, because you\'re just with them. I wanted to encapsulate something or internalize something of the beauty of that relationship.” **forwards beckon rebound** “That\'s actually one of my favorite songs on the album. I really enjoy playing it. It feels like a driving lullaby to me, like something that\'s uplifting and motivating. It feels like an acknowledgment of a very flawed part of humanness. It\'s like there\'s both sides, the shadow and the light, deciding to hold space for all of it as opposed to rejecting the shadow side or rejecting darkness but deciding to actually push into it. When we were in the studio recording that song, this magic thing happened because I did a lot of these rhythms with a paintbrush on my guitar. I\'m just playing the guitar strings with it. But it sounded like it was so much bigger, because the paintbrush would get all these overtones.” **heavy focus** “It\'s another love song on the album, I feel. It was one of the first songs that I wrote when I was with this person. The heavy focus of when you\'re super fixated on somebody, like when you\'re in the room with them and they\'re the only one in the room. The kind when you\'re taking a camera and you\'re focusing on a picture and you\'re really focusing on that image and the way it\'s framed. I was using the metaphor of the camera in the song, too. That one feels very bittersweet for me, like taking a portrait of the spirit of the energy of the moment because it\'s the only way it lasts; in a way, it\'s the only way I\'ll be able to see it again.” **half return** “There’s this weird crossover to returning home, being around my dad, and reverting back to my child self. Like when you go home and you\'re with your parents or with siblings, and suddenly you\'re in the role that you were in all throughout your life. But then it crosses into the way I felt when I had so much teenage angst with my 29-year-old angst.” **come** “This thing happened while we were out there recording, which is that a lot of people were experiencing deaths from far away because of the pandemic, and especially a lot of the elderly. It was hard for people to travel or be around each other because of COVID. And while we were recording, Phil\'s grandmother passed away. He was really close with her. I had already started this song, and a couple of days before she died, she got to hear the song.” **zombie girl** “There’s two tracks on the record that weren\'t written during the session, and this is one of them. It\'s been around for a little while. Actually, Big Thief has played it a couple of times at shows. It was written after this very intense nightmare I had. There was this zombie girl with this really scary energy that was coming for me. I had sleep paralysis, and there were these demons and translucent ghost hands fluttering around my throat. Every window and door in the house that I was staying in was open and the people had just become zombies, and there was this girl who was arched and like crouched next to my bed and looking at me. I woke up absolutely terrified. Then the next night, I had this dream that I was with this person and we were in bed together and essentially making love, but in a spirit-like way that was indescribable. It was like such a beautiful dream. I was like really close with this person, but we weren\'t together and I didn\'t even know why I was having that dream, but it was foreshadowing or foretelling what was to come. The verses kind of tell that story, and then the choruses are asking about emptiness. I feel like the zombie, the creature in the dream, represents that hollow emptiness, which may be the thing that I feel most avoidant of at times. Maybe being alone is one of the things that scares me most.” **not a lot, just forever** “The ‘not a lot’ in the title is the concept of something happening infinitely, but in a small quantity. I had never had that thought before until James \[Krivchenia, Big Thief drummer\] brought it up. We were talking about how something can happen forever, but not a lot of it, just forever. Just like a thin thread of something that goes eternally. So maybe something as small as like a bird shedding its feather, or like maybe how rocks are changed over time. Little by little, but endlessly.” **dragon eyes** “That one feels the most raw, undecorated, and purely simple. I want to feel a sense of belonging. I just want a home with you or I just want to feel that. It\'s another homage to love, tenderness, and grappling with my own shadows, but not wanting to control anyone and not wanting to blame anyone and wanting to see them and myself clearly.” **my angel** “There is this guardian angel feeling that I\'ve always had since I was a kid, where there\'s this person who\'s with me. But then also, ‘Who is my angel? Is it my lover, is it part of myself? Is it this material being that is truly from the heavens?’ I\'ve had some near-death experiences where I\'m like, \'Wow, I should have died.\' The song\'s telling this near-death experience of being pushed over the side of the cliff, and then the angel comes and kisses your eyelids and your wrists. It feels like a piercing thing, because you\'re in pain from having fallen, but you\'re still alive and returning to your oxygen. You expect to be dead, and then you somehow wake up and you\'ve been protected and you\'re still alive. It sounds dramatic, but sometimes things feel that dramatic.”

On his first LP of original songs in nearly a decade—and his first since reluctantly accepting Nobel Prize honors in 2016—Bob Dylan takes a long look back. *Rough and Rowdy Ways* is a hot bath of American sound and historical memory, the 79-year-old singer-songwriter reflecting on where we’ve been, how we got here, and how much time he has left. There are temperamental blues (“False Prophet,” “Crossing the Rubicon”) and gentle hymns (“I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You”), rollicking farewells (“Goodbye Jimmy Reed”) and heady exchanges with the Grim Reaper (“Black Rider”). It reads like memoir, but you know he’d claim it’s fiction. And yet, maybe it’s the timing—coming out in June 2020 amidst the throes of a pandemic and a social uprising that bears echoes of the 1960s—or his age, but Dylan’s every line here does have the added charge of what feels like a final word, like some ancient wisdom worth decoding and preserving before it’s too late. “Mother of Muses” invokes Elvis and MLK, Dylan claiming, “I’ve already outlived my life by far.” On the 16-minute masterstroke and stand-alone single “Murder Most Foul,” he draws Nazca Lines around the 1963 assassination of JFK—the death of a president, a symbol, an era, and something more difficult to define. It’s “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” that lingers longest, though: Over nine minutes of accordion and electric guitar mingling like light on calm waters, Dylan tells the story of an outlaw cycling through radio stations as he makes his way to the end of U.S. Route 1, the end of the road. “Key West is the place to be, if you’re looking for your mortality,” he says, in a growl that gives way to a croon. “Key West is paradise divine.”