Louder Than War Albums of the Year 2021

Louder Than War present their best albums of the year for 2021. Our Top 100 as voted for by writers and contributors to the site.

Published: December 01, 2021 08:30

Source

As Amyl and the Sniffers came off the road in late 2019, they moved into a house together in Melbourne. “It had lime green walls and mice,” frontwoman Amy Taylor tells Apple Music. “Three bedrooms and a shed out back that we took turns sleeping in. We knew we were going to come back for a long period of time to write. We just didn’t know how long.” Months later, as the bushfires gave way to a global pandemic, the Aussie punk outfit found themselves well-prepared for lockdown. “We’ve always kind of just been in each other’s pocket, forever and always,” Taylor says. “We’ve toured everywhere, been housemates, been in a van, and shared hotel rooms. We’re one person.” With all rehearsal studios closed, they rented a nearby storage unit where they could workshop the follow-up to their ARIA-winning, self-titled debut. The acoustics were so harsh and the PA so loud that guitarist Dec Martens says, “I never really heard any of Amy’s lyrics until they were recorded later on. She could’ve been singing about whatever, and I would have gone along with it, really.” And though *Comfort to Me* shows a more serious and personal side—as well as a range of influences that spans hardcore, power pop, and ’70s folk—that’s not necessarily a byproduct of living through a series of catastrophes. “I was pretty depressed,” Taylor says. “It’s hard to know what was the pandemic and what was just my brain. Even though you can’t travel and you can’t see people, life still just happens. I could look through last year and, really, it’s like the same amount of good and bad stuff happened, but in a different way. You’re just always feeling stuff.” Here, Taylor and Martens take us inside some of the album’s key tracks. **“Guided by Angels”** Amy Taylor: “I feel like, as a band, everyone thinks we’re just funny all the time. And we are funny and I love to laugh, but we also are full-spectrum humans who think about serious stuff as well, and I like that one because it’s kind of cryptic and poetic and a bit more dense. It’s not just, like, ‘Yee-haw, let’s punch a wall,’ which there’s plenty of and I also really love. We’re showing our range a little bit.” **“Freaks to the Front”** AT: “We must’ve written that before COVID. That’s absolutely a live-experience song and we’re such a live band—that’s our whole setup. We probably have more skills playing live than we do making music. It’s the energy that is contagious, and that one’s just kind of encouraging all kind of freaks, all kind of people: If you’re rich or poor or smart or fat or ugly or nice or mean, everyone just represent yourself and have a good time.” **“Choices”** Dec Martens: “\[Bassist\] Gus \[Romer\] is really into hardcore at the moment, and he wanted a really animalistic, straight-up hardcore song.” AT: “Growing up, I went to a fair handful of hardcore shows, and I personally liked the aggression of a hardcore show. In the audience, people kind of grabbing each other and chucking each other down, but then also pulling each other up and helping each other. I also just really like music that makes me feel angry. I constantly am getting unsolicited advice—or women, in general, are constantly getting told how to live and what to do. Everybody around the world is, and sometimes it’s really helpful—and I don’t discount that—but other times it’s just like, ‘Let me just fucking figure it out myself, and don’t tell me what kind of choices I can and can’t make, because it’s my flesh sack and I’ll do what I want with it.’” **“Hertz”** AT: “I think I started writing it at the start of 2020, pre-lockdown. But it’s funny now, because currently, being in lockdown again, I’m literally dying. I just want to get to the country and fucking not be in the city. So, the lyrics have really just come to fruition. I was thinking about somebody that I wasn’t really with at the time. It’s that feeling of feeling suffocated—you just want to look at the sky, just be in nature, and just be alive.” **“No More Tears”** DM: “I was really inspired by this ’70s album called *No Other* by Gene Clark, which isn’t very punk or rock. But I just played this at a faster tempo.” AT: “And also inspired heaps by the Sunnyboys, an Australian power pop band. Last year was really tough for me, and that song’s about how much I was struggling with heaps of different shit and trying to, I guess, try and make relationships work. I was just feeling not very lovable, because I’m all fucked in the head, but I’m also trying to make it work. It’s a pretty personal song.” **“Knifey”** AT: “It’s about my experience—and I’m sure lots of other people’s experience—of feeling safe to walk home at night. The world’s different for people like me and chicks and stuff: You can carry a weapon and if somebody does something awful and you react, it comes back to you. I remember when I was a kid, being like, ‘Dad, I want to get a knife,’ and he was like, ‘You can’t get a knife because you’ll kill someone and go to jail.’ But so be it. If somebody wants to have a go, I’m very happy to react negatively. At the start, I was like, ‘I don’t know if I want to do these lyrics. I don’t know if I’d want to play that song live.’ It’s probably the only song that I’ve ever really felt like that about. It hit up the boys in the band in an emotional way. They were like, ‘Fuck, this is powerful. Makes me cry and shit,’ and I was like, ‘That’s pretty dope.’” **“Don’t Need a C\*\*t (Like You to Love Me)”** AT: “It’s a fuck-you song. When I’m saying, ‘Don’t need a c\*\*t like you to love me,’ it’s pretty much just any c\*\*t that I don’t like in general. There could be some fucking piss-weak review of us or if I worked at a job and there was a crap fucking customer—it’s all of that. I wasn’t thinking about a particular bloke, although there’s many that I feel like that about.” **“Snakes”** “A bit of autobiography, an ode to my childhood. I grew up in a small town near the coast—kind of bogan, kind of hippy. I grew up on three acres, and I grew up in a shed with my sister, mom, and dad until I was about nine or 10, and we all shared a bedroom and would use the bath water to wash our clothes and then that same water to water the plants. Dad used to bring us toys home from the tip and we’d go swimming in the storms and there was snakes everywhere. There was snakes, literally, in the bedroom and the chick pens, and there’d be snakes killing the cats and snakes at school—and this song’s about that.”

“Sometimes I’ll be in my own space, my own company, and that’s when I\'m really content,” Little Simz tells Apple Music. “It\'s all love, though. There’s nothing against anyone else; that\'s just how I am. I like doing my own thing and making my art.” The lockdowns of 2020, then, proved fruitful for the North London MC, singer, and actor. She wrestled writer’s block, revived her cult *Drop* EP series (explore the razor-sharp and diaristic *Drop 6* immediately), and laid grand plans for her fourth studio album. Songwriter/producer Inflo, co-architect of Simz’s 2019 Mercury-nominated, Ivor Novello Award-winning *GREY Area*, was tapped and the hard work began. “It was straight boot camp,” she says of the *Sometimes I Might Be Introvert* sessions in London and Los Angeles. “We got things done pronto, especially with the pace that me and Flo move at. We’re quite impulsive: When we\'re ready to go, it’s time to go.” Months of final touches followed—and a collision between rap and TV royalty. An interest in *The Crown* led Simz to approach Emma Corrin (who gave an award-winning portrayal of Princess Diana in the drama). She uses her Diana accent to offer breathless, regal addresses that punctuate the 19-track album. “It was a reach,” Simz says of inviting Corrin’s participation. “I’m not sure what I expected, but I enjoyed watching her performance, and wrote most of her words whilst I was watching her.” Corrin’s speeches add to the record’s sense of grandeur. It pairs turbocharged UK rap with Simz at her most vulnerable and ambitious. There are meditations on coming of age in the spotlight (“Standing Ovation”), a reunion with fellow Sault collaborator Cleo Sol on the glorious “Woman,” and, in “Point and Kill,” a cleansing, polyrhythmic jam session with Nigerian artist Obongjayar that confirms the record’s dazzling sonic palette. Here, Simz talks us through *Sometimes I Might Be Introvert*, track by track. **“Introvert”** “This was always going to intro the album from the moment it was made. It feels like a battle cry, a rebirth. And with the title, you wouldn\'t expect this to sound so huge. But I’m finding the power within my introversion to breathe new meaning into the word.” **“Woman” (feat. Cleo Sol)** “This was made to uplift and celebrate women. To my peers, my family, my friends, close women in my life, as well as women all over the world: I want them to know I’ve got their back. Linking up with Cleo is always fun; we have such great musical chemistry, and I can’t imagine anyone else bringing what she did to the song. Her voice is beautiful, but I think it\'s her spirit and her intention that comes through when she sings.” **“Two Worlds Apart”** “Firstly, I love this sample; it’s ‘The Agony and the Ecstasy’ by Smokey Robinson, and Flo’s chopped it up really cool. This is my moment to flex. You had the opener, followed by a nice, smoother vibe, but this is like, ‘Hey, you’re listening to a *rap* album.’” **“I Love You, I Hate You”** “This wasn’t the easiest song for me to write, but I\'m super proud that I did. It’s an opportunity for me to lay bare my feelings on how that \[family\] situation affected me, growing up. And where I\'m at now—at peace with it and moving on.” **“Little Q, Pt. 1 (Interlude)”** “Little Q is my cousin, Qudus, on my dad\'s side. We grew up together, but then there was a stage where we didn\'t really talk for some years. No bad blood, just doing different things, so when we reconnected, we had a real heart-to-heart—and I heard about all he’d been through. It made me feel like, ‘Damn, this is a blood relative, and he almost lost his life.’ I thank God he didn’t, but I thought of others like him. And I felt it was important that his story was heard and shared. So, I’m speaking from his perspective.” **“Little Q, Pt. 2”** “I grew up in North London and \[Little Q\] was raised in South, and as much as we both grew up in endz, his experience was obviously different to mine. Being a product of an environment or system that isn\'t really for you, it’s tough trying to navigate that.” **“Gems (Interlude)”** “This is another turning point, reminding myself to take time: ‘Breathe…you\'re human. Give what you can give, but don\'t burn out for anyone. Put yourself first.’ Just little gems that everyone needs to hear once in a while.” **“Speed”** “This track sends another reminder: ‘This game is a marathon, not a sprint. So pace yourself!’ I know where I\'m headed, and I\'m taking my time, with little breaks here and there. Now I know when to really hit the gas and also when to come off a bit.” **“Standing Ovation”** “I take some time to reflect here, like, ‘Wow, you\'re still here and still going. It’s been a slow burn, but you can afford to give yourself a pat on the back.’ But as well as being in the limelight, let\'s also acknowledge the people on the ground doing real amazing work: our key workers, our healers, teachers, cleaners. If you go to a toilet and it\'s dirty, people go in from 9 to 5 and make sure that shit is spotless for you, so let\'s also say thank you.” **“I See You”** “This is a really beautiful and poetic song on love. Sometimes as artists we tend to draw from traumatic times for great art, we’re hurt or in pain, but it was nice for me to be able to draw from a place of real joy in my life for this song. Even where it sits \[on the album\]: right in the center, the heart.” **“The Rapper That Came to Tea (Interlude)”** “This title is a play on \[Judith Kerr’s\] children\'s book *The Tiger Who Came to Tea*, and this is about me better understanding my introversion. I’m just posing questions to myself—I might not necessarily have answers for them, I think it\'s good to throw them out there and get the brain working a bit.” **“Rollin Stone”** “This cut reminds me somewhat of ’09 Simz, spitting with rapidness and being witty. And I’m also finding new ways to use my voice on the second half here, letting my evil twin have her time.” **“Protect My Energy”** “This is one of the songs I\'m really looking forward to performing live. It’s a stepper, and it got me really wanting to sing, to be honest. I very much enjoy being around good company, but these days I enjoy my personal space and I want to protect that.” **“Never Make Promises (Interlude)”** “This one is self-explanatory—nothing is promised at all. It’s a short intermission to lead to the next one, but at one point it was nearly the album intro.” **“Point and Kill” (feat. Obongjayar)** “This is a big vibe! It feels very much like Nigeria to me, and Obongjayar is one of my favorites at the moment. We recorded this in my living room on a whim—and I\'m very, very grateful that he graced this song. The title comes from a phrase used in Nigeria to pick out fish at the market, or a store. You point, they kill. But also metaphorically, whatever I want, I\'m going to get in the same way, essentially.” **“Fear No Man”** “This track continues the same vibe, even more so. It declares: ‘I\'m here. I\'m unapologetically me and I fear no one here. I\'m not shook of anyone in this rap game.’” **“The Garden (Interlude)”** “This track is just amazing musically. It’s about nurturing the seeds you plant. Nurture those relationships, and everything around you that\'s holding you down.” **“How Did You Get Here”** “I want everyone to know *how* I got here; from the jump, school days, to my rap group, Space Age. We were just figuring it out, being persistent. I cried whilst recording this song; it all hit me, like, ‘I\'m actually recording my fourth album.’ Sometimes I sit and I wonder if this is all really true.” **“Miss Understood”** “This is the perfect closer. I could have ended on the last track, easily, but, I don\'t know, it\'s kind of like doing 99 reps. You\'ve done 99, that\'s amazing, but you can do one more to just make it 100, you can. And for me it was like, ‘I\'m going to get this one in there.’”

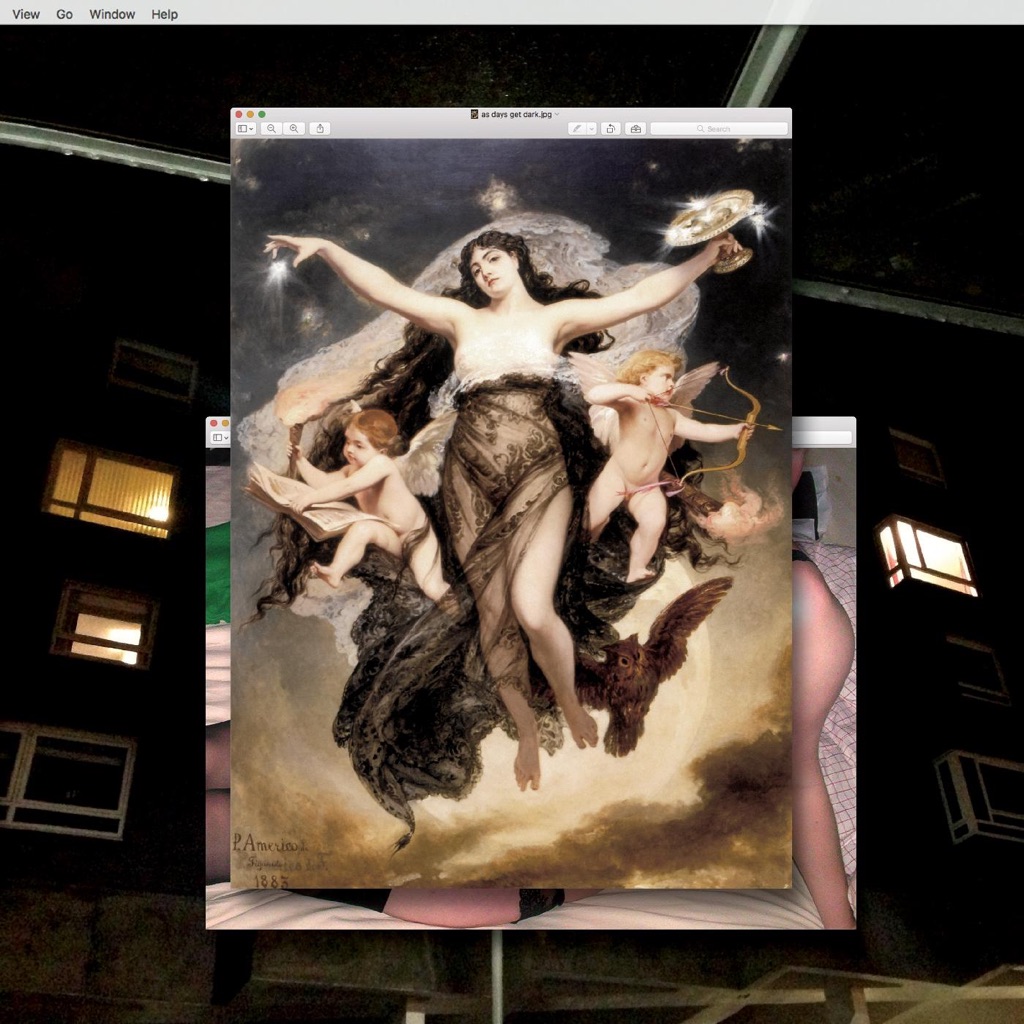

Slow builds, skyscraping climaxes, deep melancholy tempered by European grandeur: You pretty much know what you’re getting when you come to a Mogwai album, but rarely have they given it up with such ease as they do on *As the Love Continues*, their 10th LP. For a band whose central theme has remained almost industrially consistent, they’ve built up plenty of variations on it: the sparkling, New Agey electronics of “Dry Fantasy,” the classic indie rock sound of “Ceiling Granny” and “Ritchie Sacramento,” the ’80s dance rhythms of “Supposedly, We Were Nightmares.” Even when they reach for their signature build-and-release (“Midnight Flit”), you get the sense of a band not just marching toward an inevitable climax but relishing in texture, nuance, and note-to-note intricacies that make that climax feel fresh again. And while they’ve always been beautiful, they’ve also seemed to treat that beauty as an intellectual liability, something to be undermined in the name of staying sharp.

On *Compliments Please*, her 2019 debut as Self Esteem, Rebecca Taylor reintroduced herself to the world in a way that stunned fans of her previous work as one half of Sheffield indie-folk duo Slow Club. Here was Taylor fully realized as an artist—a millennial Madonna delivering personal polemic within a kaleidoscopic blast of bombastic pop. For this follow-up, Taylor has doubled down on that MO, creating a record that is bigger, better, and even more unapologetically true to herself. “On my first album I didn’t know what Self Esteem was, really,” she tells Apple Music. “Back then we were finding out and, now I know what it is, it’s a much more self-assured way to work. I knew I wanted to make *Compliments Please 2*, essentially. I wanted to do similar production but bigger and bolder. If there’s one violin, I want it to be a quartet. If it’s three-part harmony, I want it to be a choir. I just wanted to build it and make it more massive.” Over 13 frank, funny, and vital tracks, *Prioritise Pleasure* finds Taylor exploring sex and sexuality, misogyny, and toxic relationships. “Lyrically, I’ll always reflect where I’m at in my life,” she adds. “A lot of changes have happened between the first record and the second record.” Above all else though, it’s a record that uses skyscraping pop bangers to deliver a triumphant message of self-acceptance. Here, Taylor talks us through it, track by track. **“I’m Fine”** “With that slow beat opening it, me and my producer were like, ‘This would be an amazing first song…’ I’d wanted to write about something that’s happened to me. I wanted to reclaim my independence and my sexuality and my right to live my life however I want after that had been taken in a traumatic way. It has become this sort of mission statement at the top of the record for the thing I’m singing about. But for anyone who feels like they have to live their life because of the way society is—it’s for you.” **“Fucking Wizardry”** “If I had my time again, I wouldn’t put this on because I feel so overwhelmed singing it back. But it was very much where I was at when I was writing. I was in a relationship. I really, really loved him and we could have had a really good relationship, but his ex didn’t leave him alone during it. I had to get a thicker skin and build myself back up and say, ‘Do you know what? I’m not doing this.’ I did feel really hurt. I succumbed to jealousy and fear and I didn’t feel good enough. I’m embarrassed by my spitefulness, but it’s also very human and it’s important for me to show all the sides of myself on the record.” **“Hobbies 2”** “Kate Bush was someone I was thinking about when I was making this. She was an artist first and foremost and created the work. If it happened to be a hit then cool, but she was never going to deviate from just coming out of her head. This feels like a 2021 \[1985 Bush hit\] ‘Running Up That Hill.’ It’s so funny too. I’m basically saying I’ve got time to have this fuck buddy, but only if I’m not busy. I think that’s a very modern thing to have committed to song.” **“Prioritise Pleasure”** “All of my songs link to each other, because I’m always thinking about sex, sense of self, heartbreak, or defiance. They’re always in there. *Prioritise Pleasure* is sexy and it’s about prioritizing yourself in that way, but also it’s about prioritizing just what you want every day. As a woman, I’ve people-pleased and shapeshifted and sort of begged the world to not be mad with me my whole life. The turnaround and the key to my happiness is to not do that anymore.” **“I Do This All The Time”** “I’d wanted to a song that was like \[Baz Luhrmann’s ‘Everybody’s Free (To Wear Sunscreen)’\]. And a song that’s like ‘Dirrty’ by Christina Aguilera. I did one take. It’s almost like it possessed me. I had to just make it. There was this moment when I was tracking and recording the string line, I walked home, listened to it and thought, ‘I could just stop now.’ There was this part of me that was like, ‘This is it. This is what I’ve always wanted to do. This is always what I wanted to say.’ I’ve not had that feeling before.” **“Moody”** “I loved the keyboard sound and Johan \[Karlberg, producer\] just smashed a loop out. I had the lyric ‘Sexting you at the mental health talk seems counterproductive’ for ages so I put that in and that set the tone of what I wanted to write about. Spelling-out pop choruses are always L-O-V-E or whatever, I’ve always had this idea of spelling out something that has negative connotations. I thought it would be funny to do a song where I’m saying what I’m saying in the form of very sugary pop. It’s a bit of a piss-take really, me being sarcastic about girly pop music.” **“Still Reigning”** “That’s a sister song to ‘She Reigns’ on the first record. I’m obsessed with acceptance at the minute and letting things just be. I’ve always been someone who wants to strong-arm reality into what I need it to be, rather than just letting it happen. I was a very convincing kid. I remember convincing my dad to get a dog by drawing a pamphlet that I pretended was from the RSPCA, where I listed the benefits of having a dog. That was cute, but I was just being a manipulative little shit. I’ve always been like, ‘I want this, why not?’ That’s how I was approaching a relationship that I wanted to continue and they didn’t. Finally, the penny dropped about letting things go with the flow and about acceptance and love.” **“How Can I Help You”** “‘Black Skinhead’ was something we were going for in mood. Everything comes back to Kanye production every time we’re stuck. It’s a weird song but I’m a punk at my core. I love pop but I cut my teeth playing in a lot of punk bands. It’s a little nod to the tapestry of me and my music. Being a woman is hard enough. Being someone who wants to please everyone is very hard. Then being in the music industry has been really hard. So \[the lyrics are about\] all of it.” **“It’s Been A While”** “Me and Johan both really love trap and I requested a very, very deep, dark trap loop. This one is a bit of another timestamp. I’m addicted to my phone and the sort of weariness from it. I’ll be texting someone I’m seeing. Then I’m on Twitter making some sort of joke. Then I’m reading some news report about something awful. Then I’m on Instagram liking some cute woman’s picture. It’s round and round and round and my eyes are consuming so much all day. Also, I was still going out with that guy that was treating me pretty cheap. Again, it comes back to trying to strong-arm the world into doing what I want. It’s about all those things.” **“The 345”** “It’s me singing to me. It’s very on-the-nose. I just wondered what a love song to myself would be. I sing so many love songs to these people that come in and out of my life. I wondered what would happen if I sang to the person that’s not going to go anywhere, which sounds quite sad.” **“John Elton”** “It’s playing on the idea that these people come into your life and you love them and then they go and then that’s it. I’ve always struggled with that. Someone I loved who I had the joke with, and the joke was a really shit joke, but it still makes me laugh. Then you go to chat about it but everyone’s lives have moved on. People get married and have children and I’m just still out here laughing at the stupid joke we had. It’s an interesting little jolt back to reality and all part of the experience. I end the song by saying it’s all for me. No matter what, all of this is mine and all of these experiences are mine and that’s it.” **“You Forever”** “This is coming from a place of deciding whether or not to get back with someone. At one point in time, I really wanted to and I said that, and the other person said, ‘You need to be braver.’ Also an acceptance is creeping in where I’ve been all right on my own and I will be all right on my own. That’s important to hold on to. Modern dating is as much about not wanting to be alone as it is about trying to meet someone you like. To be all right on your own really does mean if you meet someone and they add something to your life, that’s what it should be about.” **“Just Kids”** “With a lot of my songs, when it’s not just romantic relationships, it’s about the frustration and the desire to be loved by someone who just won’t. Deciding to stop trying is what the song is about. Accept it and leave it with love but move forward in your life. It feels like a good place to try and put that to bed before I write the next album.”

The intense process of making a debut album can have enduring effects on a band. Some are less expected than others. “It made my clothes smell for weeks afterwards,” Squid’s drummer/singer Ollie Judge tells Apple Music. During the British summer heatwave of 2020, the UK five-piece—Judge and multi-instrumentalists Louis Borlase, Arthur Leadbetter, Laurie Nankivell, and Anton Pearson—decamped to producer Dan Carey’s London studio for three weeks. There, Carey served them the Swiss melted-cheese dish raclette, hence the stench, and also helped the band expand the punk-funk foundations of their early singles into a capricious, questing set that draws on industrial, jazz, alt-rock, electronic, field recordings, and a Renaissance-era wind instrument called the rackett. The songs regularly reflect on disquieting aspects of modern life—“2010” alone examines greed, gentrification, and the mental-health effects of working in a slaughterhouse—but it’s also an album underpinned by the kindness of others. Before Carey hosted them in a COVID-safe environment at his home studio, the band navigated the restrictions of lockdown with the help of people living near Judge’s parents in Chippenham in south-west England. A next-door neighbor, who happens to be Foals’ guitar tech, lent them equipment, while a local pub owner opened up his barn as a writing and rehearsal space. “It was really nice, so many people helping each other out,“ says Borlase. “There’s maybe elements within the music, on a textural level, of how we wished that feel of human generosity was around a bit more in the long term.” Here, Borlase, Judge, and Pearson guide us through the record, track by track. **“Resolution Square”** Anton Pearson: “It’s a ring of guitar amps facing the ceiling, playing samples. On the ceiling was a microphone on a cord that swung around like a pendulum. So you get that dizzying effect of motion. It’s a bit like a red shift effect, the pitch changing as the microphone moves. We used samples of church bells and sounds from nature. It felt like a really nice thing to start with, kind of waking up.” Ollie Judge: “It sounds like cars whizzing by on the flyover, but it’s all made out of sounds from nature. So it’s playing to that push and pull between rural and urban spaces.” **“G.S.K.”** OJ: “I started writing the lyrics when I was on a Megabus from Bristol to London. I was reading *Concrete Island* by J. G. Ballard, and that is set underneath that same flyover that you go on from Bristol to London \[the Chiswick Flyover\]. I decided to explore the dystopic nature of Britain, I guess. It’s a real tone-setter, quite industrial and a bit unlike the sound world that we’ve explored before. Lots of clanging.” **“Narrator”** OJ: “It’s almost like a medley of everything we’ve done before: It’s got the punk-funk kind of stuff, and then newer industrial kind of sounds, and a foray into electronic sounds.” Louis Borlase: “It’s actually one of the freest ones when it comes to performing it. The big build-up that takes you through to the very end of the song is massively about texture in space, therefore it’s also massively about communication. That takes us back to the early days of playing in the Verdict \[jazz venue\] together, in Brighton, where we used to have very freeform music. It was very much about just establishing a tonality and a harmony and potentially a rhythm, and just kind of riding with it.” **“Boy Racers”** OJ: “It’s a song of two halves. The familiar, almost straightforward pop song, and then it ends in a medieval synth solo.” LB: “We had started working on it quite crudely, ready to start performing it on tour, in March 2020, just before lockdown. In lockdown, we started sending each other files and letting it develop via the internet. Just at the point where everything stops rhythmically and everything gets thrown up into the air—and enter said rackett solo—it’s the perfect depiction of when we were able to start seeing each other again. That whole rhythmic element stopped, and we left the focus to be what it means to have something that’s very free.” **“Paddling”** OJ: “The big, gooey pop centerpiece of the album. There’s a video of us playing it live from quite a few years ago, and it’s changed so much. We added quite a bit of nuance.” AP: “It was a combined effort between the three of us, lyrically. It started off about coming-of-age themes and how that related to readings about *The Wind in the Willows* and Mole—about things feeling scary when they’re new sometimes. That kind of naivety can trip you up. Then also about the whole theme of the book, about greed and consumerism, and learning to enjoy simple things. That book says such a beautiful thing about joy and how to get enjoyment out of life.” **“Documentary Filmmaker”** OJ: “It was quite Steve Reich-inspired, even to the point where when I played my girlfriend the album for the first time she said, ‘Oh, I thought that was Steve Reich. That was really nice.’” LB: “It started in a bedroom jam at Arthur’s family house. We had quite a lazy summer afternoon, no pressure in writing, and that’s preserved its way through to what it is on the album.” AP: “Sometimes we set out with ideas like that and they move into the more full-band setting. We felt was really important to keep this one in that kind of stripped-back nature.” **“2010”** OJ: “I think it’s a real shift towards future Squid music. It’s more like an alternative rock song than a post-punk band. It’s definitely a turning point: Our music has been known to be quite anecdotal and humorous in places, but this is quite mature. It doesn’t have a tongue-in-cheek moment.” LB: “Lyrically, it’s tackling some themes which are quite distressing and expose some of the problematic aspects of society. Trying to make that work, you’re owing a lot to the people involved, people that are affected by these issues, and you don’t want to make something that doesn’t feel truly thought about.” **“The Flyover”** AP: “It moulds really nicely into ‘Peel St.’ after it, which is quite fun—that slow morphing from something quite calm into something quite stressful. Arthur sent some questions out to friends of the band to answer, recorded on their phones. He multi-tracked them so there’s only ever like three people talking at one time. It’s just such a hypnotic and beautiful thing to listen to. Lots of different people talking about their lives and their perspectives.” **“Peel St.”** AP: “That’s the first thing we came up with when we met up in Chippenham, after having been separate for so long. It was this wave of excitement and joy. I don’t know why, when we’re all so happy, something like that comes out. That rhythmic pattern grew from those first few days, because it was really emotional.” LB: “It was joyful, but when we were all in that barn on the first day, I don’t think any of us were quite right. We called it ‘Aggro’ before we named it ‘Peel St.,’ because we would feel pretty unsettled playing it. It was a workout mentally and physically.” **“Global Groove”** OJ: “I got loads of inspiration from a retrospective on Nam June Paik—who’s like the godfather of TV art, or video installations—at the Tate. It’s a lot about growing up with the 24-hour news cycle and how unhealthy it is to be bombarded with mostly bad news—but then sometimes a nice story about an animal \[gets added\] on the end of the news broadcast. Growing up with various atrocities going on around you, and how the 24-hour news cycle must desensitize you to large-scale wars and death.” **“Pamphlets”** LB: “It’s probably the second oldest track on the album. The three of us were staying at Ollie’s parents’ house a couple of summers ago and it was the first time we bought a whiteboard. We now write music using a whiteboard, we draw stuff up, try and keep it visual. It also makes us feel quite efficient. ‘Pamphlets’ became an important part of our set, particularly finishing a set, because it’s quite a long blow-out ending. But when we brought it back to Chippenham last year, it had changed so much, because it had had so much time to have so many audiences responding to it in different ways. It’s very live music.”

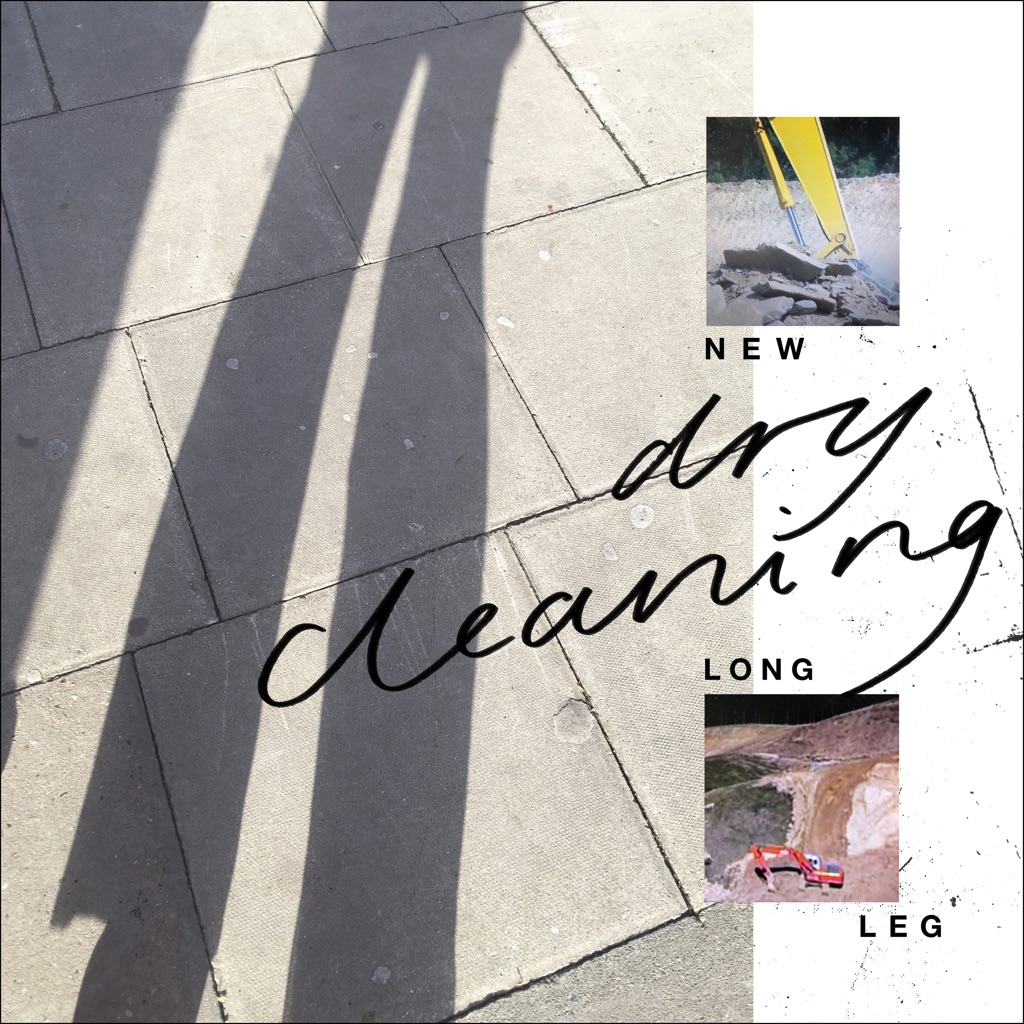

“Straight away,” Dry Cleaning drummer Nick Buxton tells Apple Music. “Immediately. Within the first sentence, literally.” That is precisely how long it took for Buxton and the rest of his London post-punk outfit to realize that Florence Shaw should be their frontwoman, as she joined in with them during a casual Sunday night jam in 2018, reading aloud into the mic instead of singing. Though Buxton, guitarist Tom Dowse, and bassist Lewis Maynard had been playing together in various forms for years, Shaw—a friend and colleague who’s also a visual artist and university lecturer—had no musical background or experience. No matter. “I remember making eye contact with everyone and being like, ‘Whoa,’” Buxton says. “It was a big moment.” After a pair of 2019 EPs comes the foursome’s full-length debut, *New Long Leg*, an hypnotic tangle of shape-shifting guitars, mercurial rhythms, and Shaw’s deadpan (and often devastating) spoken-word delivery. Recorded with longtime PJ Harvey producer John Parish at the historic Rockfield Studios in Wales, it’s a study in chemistry, each song eventually blooming from jams as electric as their very first. Read on as Shaw, Buxton, and Dowse guide us through the album track by track. **“Scratchcard Lanyard”** Nick Buxton: “I was quite attracted to the motorik-pedestrian-ness of the verse riffs. I liked how workmanlike that sounded, almost in a stupid way. It felt almost like the obvious choice to open the album, and then for a while we swayed away from that thinking, because we didn\'t want to do this cliché thing—we were going to be different. And then it becomes very clear to you that maybe it\'s the best thing to do for that very reason.” **“Unsmart Lady”** Florence Shaw: “The chorus is a found piece of text, but it suited what I needed it for, and that\'s what I was grasping at. The rest is really thinking about the years where I did lots and lots of jobs all at the same time—often quite knackering work. It’s about the female experience, and I wanted to use language that\'s usually supposed to be insulting, commenting on the grooming or the intelligence of women. I wanted to use it in a song, and, by doing that, slightly reclaim that kind of language. It’s maybe an attempt at making it prideful rather than something that is supposed to make you feel shame.” **“Strong Feelings”** FS: “It was written as a romantic song, and I always thought of it as something that you\'d hear at a high school dance—the slow one where people have to dance together in a scary way.” **“Leafy”** NB: “All of the songs start as jams that we play all together in the rehearsal room to see what happens. We record it on the phone, and 99 percent of the time you take that away and if it\'s something that you feel is good, you\'ll listen to it and then chop it up into bits, make changes and try loads of other stuff out. Most of the jams we do are like 10 minutes long, but ‘Leafy’ was like this perfect little three-minute segment where we were like, ‘Well, we don\'t need to do anything with that. That\'s it.’” **“Her Hippo”** FS: “I\'m a big believer in not waiting for inspiration and just writing what you\'ve got, even if that means you\'re writing about a sense of nothingness. I think it probably comes from there, that sort of feeling.” **“New Long Leg”** NB: “I\'m really proud of the work on the album that\'s not necessarily the stuff that would jump out of your speakers straight away. ‘New Long Leg’ is a really interesting track because it\'s not a single, yet I think it\'s the strongest song on the album. There\'s something about the quality of what\'s happening there: Four people are all bringing something, in quite an unusual way, all the way around. Often, when you hear music like that, it sounds mental. But when you break it down, there\'s a lot of detail there that I really love getting stuck into.” **“John Wick”** FS: “I’m going to quote Lewis, our bass player: The title ‘John Wick’ refers to the film of the same name, but the song has nothing to do with it.” Tom Dowse: “Giving a song a working title is quite an interesting process, because what you\'re trying to do is very quickly have some kind of onomatopoeia to describe what the song is. ‘Leafy’ just sounded leafy. And ‘John Wick’ sounded like some kind of action cop show. Just that riff—it sounded like crime was happening and it painted a picture straight away. I thought it was difficult to divorce it from that name.” **“More Big Birds”** TD: “One of the things you get good at when you\'re a band and you\'re lucky enough to get enough time to be together is, when someone writes a drum part like that, you sit back. It didn\'t need a complicated guitar part, and sometimes it’s nice to have the opportunity to just hit a chord. I love that—I’ll add some texture and let the drums be. They’re almost melodic.” **“A.L.C”** FS: “It\'s the only track where I wrote all the lyrics in lockdown—all the others were written over a much longer period of time. But that\'s definitely the quickest I\'ve ever written. It\'s daydreaming about being in public and I suppose touches on a weird change of priorities that happened when your world just gets really shrunk down to your little patch. I think there\'s a bit of nostalgia in there, just going a bit loopy and turning into a bit of a monster.” **“Every Day Carry”** FS: “It was one of the last ones we recorded and I was feeling exhausted from trying so fucking hard the whole recording session to get everything I wanted down. I had sheets of paper with different chunks that had already been in the song or were from other songs, and I just pieced it together during the take as a bit of a reward. It can be really fun to do that when you don\'t know what you\'re going to do next, if it\'s going to be crap or if it\'s going to be good. That\'s a fun thing—I felt kind of burnt out, so it was nice to just entertain myself a bit by doing a surprise one.”

“I wanted to get a better sense of how African traditional cosmologies can inform my life in a modern-day context,” Sons of Kemet frontman Shabaka Hutchings tells Apple Music about the concept behind the British jazz group’s fourth LP. “Then, try to get some sense of those forms of knowledge and put it into the art that’s being produced.” Since their 2013 debut LP *Burn*, the Barbados-raised saxophonist/clarinetist and his bandmates (tuba player Theon Cross and drummers Tom Skinner and Eddie Hick) have been at the forefront of the new London jazz scene—deconstructing its conventions by weaving a rich sonic tapestry that fuses together elements of modal and free jazz, grime, dub, ’60s and ’70s Ethiopian jazz, and Afro-Caribbean music. On *Black to the Future*, the Mercury Prize-nominated quartet is at their most direct and confrontational with their sociopolitical message—welcoming to the fold a wide array of guest collaborators (most notably poet Joshua Idehen, who also collaborated with the group on 2018’s *Your Queen Is a Reptile*) to further contextualize the album’s themes of Black oppression and colonialism, heritage and ancestry, and the power of memory. If you look closely at the song titles, you’ll discover that each of them makes up a singular poem—a clever way for Hutchings to clue in listeners before they begin their musical journey. “It’s a sonic poem, in that the words and the music are the same thing,” Hutchings says. “Poetry isn\'t meant to be descriptive on the surface level, it\'s descriptive on a deep level. So if you read the line of poetry, and then you listen to the music, a picture should emerge that\'s more than what you\'d have if you considered the music or the line separately.” Here, Hutchings gives insight into each of the tracks. **“Field Negus” (feat. Joshua Idehen)** “This track was written in the midst of the Black Lives Matter protests in London, and it was a time that was charged with an energy of searching for meaning. People were actually starting to talk about Black experience and Black history as it related to the present, in a way that hadn\'t really been done in Britain before. The point of artists is to be able to document these moments in history and time, and be able to actually find a way of contextualizing them in a way that\'s poetic. The aim of this track is to keep that conversation going and keep the reflections happening. I\'ve been working with Joshua for 15 years and I really appreciate his perspective on the political realm. He\'s got a way of describing reality in a manner which makes you think deeply. He never loses humor and he never loses his sense of sharpness.” **“Pick Up Your Burning Cross” (feat. Moor Mother & Angel Bat Dawid)** “It started off with me writing the bassline, which I thought was going to be a grime bassline. But then in the pandemic lockdown, I added layers of horns and woodwinds. It took it completely out of the grime space and put it more in that Antillean-Caribbean atmosphere. It really showed me that there\'s a lot of intersecting links between these musics that sometimes you\'re not even aware of until you start really diving into their potential and start adding and taking away things. It was really great to actually discover that the tune had more to offer than I envisioned in the beginning. Angel Bat Dawid and Moor Mother are both on this one, and the only thing I asked them to do was to listen to the track and just give their honest interpretation of what the music brings out of them.” **“Think of Home”** “If you\'re thinking poetically, you\'ve got that frantic energy of \'Burning Cross,\' which signifies dealing with those issues of oppression. Then at the end of that process of dealing with them, you\'ve got to still remember the place that you come from. You\'ve got to think about the utopia, think about that serene tranquil place so that you\'re not consumed in the battle. It\'s not really trying to be a Caribbean track per se, but I was trying to get that feeling of when I think back to my days growing up in Barbados. This is the feeling I had when I remember the music that was made at that time.” **“Hustle” (feat. Kojey Radical)** “The title of the track links back to the title of our second album, *Lest We Forget What We Came Here to Do*. The answer to that question is to hustle. Our grandparents came and migrated to Britain, not to just be British per se, but so that they could then create a better life for themselves and their families and have the future be one with dignity and pride. I gave these words to Kojey and he said that he finds it difficult to depict these types of struggles considering that he\'s not in the present moment within the same struggle that he grew up in. He felt it was disingenuous for him to talk about the struggle. I told him that he\'s a storyteller, and storytelling isn\'t always autobiographical. His gift is to be able to tell stories for his community, and to remember that he\'s also an orator of their history regardless of where his personal journey has led him.” **“For the Culture” (feat. D Double E)** “Originally, we\'d intended D Double E to be on \'Pick Up Your Burning Cross.\' But he came into the studio and it really wasn\'t the vibe that he was in. We played him the demo of this track and his face lit up. He was like, \'Let\'s go into the studio. I know what to do.\' It was one take and that was it. I think this might be one of my favorite tunes on the album. The reason I called it \'For the Culture\' is that it puts me back into what it felt like to be a teenager in Barbados in the \'90s, going into the dance halls and really learning what it is to dance. It\'s not just all about it being hard and struggling and striving; there is that fun element of celebrating what it is to be sensual and to be alive and love music and partying and just joyfulness.” **“To Never Forget the Source”** “I gave this really short melody to the band, maybe like four bars for the melody and a very repeated bassline. We played it for about half an hour, where the drums and bass entered slowly and I played the melody again and again. The idea of this, when we recorded in the studio, is that it needs to be the vibe and spirit of how we are playing together. So it wasn\'t about stopping and starting and being anxious. We need to play it until the feeling is right. The clarinets and the flutes on this one is maybe the one I\'m most proud of in terms of adding a counterpoint line, which really offsets and emphasizes the original saxophone and tuba line.” **“In Remembrance of Those Fallen”** “The idea of \'In Remembrance of Those Fallen\' is to give homage to those people that have been fighting for liberation and freedom within all those anti-colonial movements, and remember the ongoing struggle for dignity within especially the Black world in Africa. It\'s trying to get that feeling of \'We can do this. We can go forward, regardless of what hurdles have been done and of what hurdles we\'ve encountered.\' But, musically, there\'s so many layers to this. I was excited with how, on one side, the drums are doing what you\'d describe as Afro-jazz, and on the other one, it\'s doing a really primal sound—but mixing it in a way where you feel the impact of those two contrasting drum patterns. This is at the heart of what I like about the drums in Kemet. Regardless of what they\'re doing, the end result becomes one pulsating, forward-moving machine.” **“Let the Circle Be Unbroken”** “I was listening to a lot of \[Brazilian composer\] Hermeto Pascoal while making the album, and my mind was going onto those beautiful melodies that Hermeto sometimes makes. Songs that feel like you remember them, but they\'ve got a level of harmonic intricacy, which means that there\'s something disorienting too. It\'s like you\'re hearing a nursery rhyme in a dream, hearing the basic contour of the melody, but there\'s just something below the surface that disorientates you and throws you off what you know of it. It\'s one of the only times I\'ve ever heard that midtempo soca descend into brutal free jazz.” **“Envision Yourself Levitating”** “This one also features one of my heroes on the saxophone, Kebbi Williams, who does the first saxophone solo on the track. His music has got that real New Orleans communal vibe to it. For me, this is the height of music making—when you can make music that\'s easy enough to play its constituent parts, but when it all pieces together, it becomes a complex tapestry. It\'s the first point in the album where I do an actual solo with backing parts. This is, in essence, what a lot of calypso bands do in Barbados. So when you\'ve got traditional calypso music, you\'ll get a performer who is singing their melody and then you\'ve got these horn section parts that intersect and interact with the melody that the calypsonian is singing. It\'s that idea of an interchange between the band backing the chief melodic line.” **“Throughout the Madness, Stay Strong”** “It\'s about optimism, but not an optimism where you have a smile on your face. An optimism where you\'re resigned to the place of defeat within the big spectrum of things. It\'s having to actually resign yourself to what has happened in the continued dismantling of Black civilization, and how Black people are regarded as a whole in the world within a certain light; but then understanding that it\'s part of a broader process of rising to something else, rising to a new era. Also, on the more technical side of the recording of this tune, this was the first tune that we recorded for the whole session. It\'s the first take of the first tune on the first day.” **“Black” (feat. Joshua Idehen)** “There was a point where we all got into the studio and I asked that we go into these breathing exercises where we essentially just breathe in really deeply about 30 times, and at the end of 30, we breathe out and hold it for as long as you can with nothing inside. We did one of these exercises while lying on the floor with our eyes shut in pitch blackness. I asked everyone to scream as hard as we can, really just let it out. No one could have anything in their ears apart from the track, so no one was aware of how anyone else sounded. It was complete no-self-awareness, no shyness. It\'s like a cathartic ritual to really just let it out, however you want.”

On his Red Hand Files website, Nick Cave reflected on a comment he’d made back in 1997 about needing catastrophe, loss, and longing in order for his creativity to flourish. “These words sound somewhat like the indulgent posturing of a man yet to discover the devastating effect true suffering can have on our ability to function, let alone to create,” he wrote. “I am not only talking about personal grief, but also global grief, as the world is plunged deeper into this wretched pandemic.” Whether he needs it or not, the Australian songwriter’s music does very often deal with catastrophe, loss, and longing. The pandemic didn’t inspire *CARNAGE* per se, but the challenges of 2020 clearly permitted both intense, lyric-stirring ideas and, with canceled tours and so on, the time and creativity to flesh them out with longtime collaborator and masterful multi-instrumentalist/songwriter Warren Ellis. The most direct reference to COVID-19 might be “Albuquerque,” a sentimental lamentation on the inability to travel. For the most part, Cave looks beyond the pandemic itself, throwing himself into a philosophical realm of meditations on humanity, isolation, love, and the Earth itself, depicted through observations and, as he is wont to do, taking on the roles of several other characters, sentient and otherwise. The album begins with “Hand of God.” There’s soft piano and lyrics about the search for “that kingdom in the sky,” until Ellis\' dissonant violin strikes away the sweetness and an electronic beat kicks in. “I’m going to the river where the current rushes by/I’m gonna swim to the middle where the water is real high,” he sings, a little manically, as he gives in to the current. “Hand of God coming from the sky/Gonna swim to the middle and stay out there awhile… Let the river cast its spell on me.” That unmitigated strength of nature is central to *CARNAGE*. Motifs of rivers, rain, animals, fields, and sunshine are used to depict not only the beauty and the bedlam he sees in the world, but the ways it changes him. On the sweet, delicate “Lavender Fields,” he sings of “traveling appallingly alone on a singular road into the lavender fields… the lavender has stained my skin and made me strange.” On “Carnage,” he sings of loss (“I always seem to be saying goodbye”), but also of love and hope, later depicting a “reindeer, frozen in the footlights,” who then escapes back into the woods. “It’s only love, with a little bit of rain,” goes the uplifting refrain. With its murky rhythm and snarling spoken-word lyrics, “White Elephant” is one of Cave’s most intense songs in years. It’s also the song that most explicitly references a 2020 event: the murder of George Floyd. “The white hunter sits on his porch with his elephant gun and his tears/He\'ll shoot you for free if you come around here/A protester kneels on the neck of a statue, the statue says, ‘I can’t breathe’/The protester says, ‘Now you know how it feels’ and he kicks it into the sea.” Later, he continues, as the hunter: “I’ve been planning this for years/I’ll shoot you in the f\*\*king face if you think of coming around here/I’ll shoot you just for fun.” It’s one of the only Nick Cave songs to ever address a racially, politically charged event so directly. And it’s a dark, powerful moment on this album. *CARNAGE* ends with a pair of atmospheric ballads—their soundscapes no doubt influenced by Cave and Ellis’ extensive work on film scores. On “Shattered Ground,” the exodus of a girl (a personification of the moon) invokes peaceful, muted pain—“I will be all alone when you are gone… I will not make a single sound, but come softly crashing down”—and “Balcony Man” depicts a man watching the sun and considering how “everything is ordinary, until it’s not,” tweaking an idiom with serene acceptance: “You are languid and lovely and lazy, and what doesn’t kill you just makes you crazier.” There is substantial pain, darkness, and loss on this album, but it doesn’t rip its narrator apart or invoke retaliation. Rather, he takes it all in, allowing himself to be moved and changed even if he can’t effect change himself. That challenging sense of being unable to do anything more than *observe* is synonymous with the pandemic, and more broadly the evolving, sometimes devastating world. Perhaps the lesson here is to learn to exist within its chaos—but to always search for beauty and love in its cracks.

When IDLES released their third album, *Ultra Mono*, in September 2020, singer Joe Talbot told Apple Music that it was focused on being present and, he said, “accepting who you are in that moment.” On the Bristol band’s fourth record, which arrived 14 months later, that perspective turns sharply back to the past as Talbot examines his struggles with addiction. “I started therapy and it was the first time I really started to compartmentalize the last 20 years, starting with my mum’s alcoholism and then learning to take accountability for what I’d done, all the bad decisions I’d made,” he tells Apple Music’s Zane Lowe. “But also where these bad decisions came from—as a forgiveness thing but way more as a responsibility thing. Two years sober, all that stuff, and I came out and it was just fluid, we \[Talbot and guitarist Mark Bowen\] both just wrote it and it was beautiful.” Talbot is unshrinkingly honest in his self-examination. Opener “MTT 420 RR” considers mortality via visceral reflections on a driving incident that the singer was fortunate to escape alive, before his experiences with the consuming cycle of addiction cut through the pneumatic riffs of “The Wheel.” There’s hope here, too. During soul-powered centerpiece “The Beachland Ballroom,” Talbot is as impassioned as ever and newly melodic (“It was a conversation we had, I wanted to start singing”). It’s a song where he’s on his knees but he can discern some light. “The plurality of it is that perspective of *CRAWLER*, the title,” he says. “Recovery isn’t just a beautiful thing, you have to go through a lot of processes that are ugly and you’ve got to look at yourself and go, ‘Yeah, you were not a good person to these people, you did this.’ That’s where the beauty comes from—afterwards you have a wider perspective of where you are. And also from other people’s perspectives, you see these things, you see people recovering or completely enthralled in addiction, and it’s all different angles. We wanted to create a picture of recovery and hope but from ugly and beautiful angles. You’re on your knees, some people are begging, some people are working, praying, whatever it is—you’ve got to get through it.” *CRAWLER* may be IDLES’ most introspective work to date, but their social and political focus remains sharp enough on the tightly coiled “The New Sensation” to skewer Conservative MP Rishi Sunak’s suggestion that some people, including artists and musicians, should abandon their careers and retrain in a post-pandemic world. With its rage and wit, its bleakness and hope, and its diversions from the band’s post-punk foundations into ominous electronica (“MTT 420 RR”), glitchy psych textures (“Progress”), and motorik rhythms butting up against free jazz (“Meds”), *CRAWLER* upholds Talbot’s earliest aims for the band. In 2009, he resolved to create something with substance and impact—an antidote to the bands he’d watched in Bristol and London. “They looked beautiful but bored,” he says. “They were clothes hangers, models. I was so sick of paying money to see bored people. Like, ‘What are you doing? Where’s the love?’ I was at a place where I needed an outlet, and luckily I found four brothers who saved my life. And the rest is IDLES.”

Music by CHIHUAHUA. Recorded at 80 Hertz Studios, Manchester. Produced by Karl Sveinsson of Queen's Ark Audio. Mastered by Joe Caithness. Artwork by Rufus Murphy.

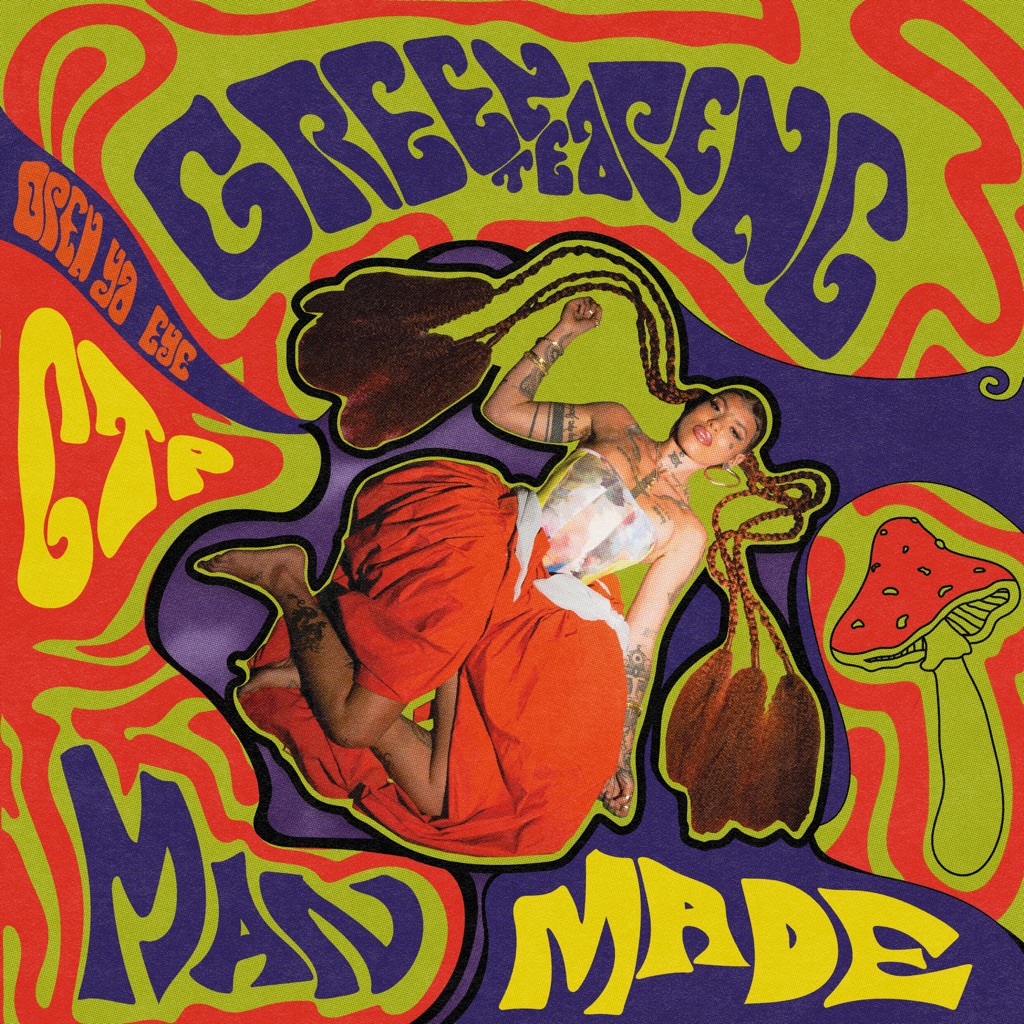

“I would definitely say that 2020 pushed me over the edge, to the point that I needed to express myself more than I ever had,” Greentea Peng tells Apple Music. Recordings for *MAN MADE*—her debut album—first took shape in the early months of 2020, coinciding with a pandemic-induced lockdown and shortly after some sad family news. It led her to use the work as both a means of rumination on the pains of modern life and an ode to his memory. Creating a makeshift studio out of a friend’s house (nicknamed “the woods” from its location in the greenery of Surrey), she spent time alongside longtime friends and collaborators including her band, The Seng Seng Family, and executive producer Earbuds, diving into eclectic genres—ska, soul, trip-hop, dub—to “deliberate my inner workings, and inner conflicts,” she says. But there’s also an underlying effort to weather that conflict through messages of oneness and healing. The bulk of the project is deliberately mixed in 432 Hz (a frequency below industry standard) by legendary engineer Gordon \"Commissioner Gordon\" Williams, inspired by Wells’ research into the power of vibrations to provide comfort and restoration. “We\'re living in a very conflicting time,” she says. “Amidst the huge paradigm shift globally, physically, and spiritually, things are intense. I always want to help uplift and bring people into the spirit, ignite a little self-belief and sovereignty inside.” Explore *MAN MADE* with her track-by-track guide. **“Make Noise”** “This is a manifesto for the album. The song started from a beat that SAMO and Josh \[Kiko, UK music producers\] brought to the woods. We were listening to it, the band started jamming it. It ended up turning out really different to the original. I was in a very free state of expression, channeling like Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry. It\'s not meant to be an easily digested piece of work; it\'s meant to be somewhat niche and provoking.” **“This Sound”** “My band and I were in a perfect environment—very comfortable, there was a heat wave—and we got very trippy. We were making an untold amount of music and things would just happen, the boys started playing, and again, it just came. When we were making it, I wasn\'t thinking of any influences, but when I listen back, I think Fatboy Slim, or Quentin Tarantino movies. But that\'s just it—no song on the album really sounds like the song before, but in a way they all do.” **“Free My People” (feat. Simmy and Kid Cruise)** “Simmy \[UK musician\] and Cam \[Toman, UK musician known as Kid Cruise\] are my bredrins, they\'ve been my bredrins for years. Before the lockdown I\'d always ask them to open up my shows; we\'re almost in a similar kind of vibe the way we mix up the genres. I invited them through to the woods and we actually wrote that song together on the spot.” **“Be Careful”** “Swindle \[UK musician and music producer\] came with the beat and then we recreated it with the musicians. ‘Be Careful’ was cool because it\'s probably the most different tune on the album; it\'s quite modern-sounding, almost trappy type. And in terms of the lyrics, I feel like it\'s one of the simpler songs—it\'s straight to the point.” **“Nah It Ain’t the Same”** “When I say ‘being a man today,’ I\'m talking about how being human today is just not the same; when you read scriptures, the word ‘man’ is what human is referred to, like, ‘We are all man at the end of the day.’ I guess I was playing devil\'s advocate a little bit because I knew people were gonna be like, ‘What about women?’ But I\'m going beyond that, beyond all of these ideas of man and woman. For me, I think everyone should be actively seeking to try and balance both their masculine and feminine energy; it doesn\'t matter what people identify with.” **“Earnest”** “The words just came to me—I think I just was waiting for the opportunity to be able to purge and release all of this shit. I\'m kind of channeling Barrington Levy and other kinds of reggae, but also just exploring my journey with faith and my connection with God, exploring that in there. It’s very honest.” **“Suffer”** “I originally started writing this about my man—he lost his dad basically the year I started going out with him. Initially I started writing about seeing him upset all the time and feeling his pain. I\'m very sensitive, and very much an empath. When I then also experienced loss, it gave ‘Suffer’ a new lease of life. I touch on the topic of inherited trauma as well; it\'s such a massive thing that people just don\'t realize or know about.” **“Mataji Freestyle”** “That was one of the ones we made at like five in the morning—we jammed that song for about two hours straight. Me and the boys were in altered states of consciousness a lot of the time. Obviously we\'re making music in 432 Hz as well, so that definitely added to the energy of the house. It was very meditative and intense, like I was crying whilst recording that song. It\'s also quite a complex song if you break it down in terms of technicals; everyone is on a different time.” **“Kali V2”** “It’s controversial; I knew certain heads were not gonna like it. But at the end of the day, the album isn\'t for everyone. I guess it was kind of like a battle tune, a kind of rebel tune—the whole album is, to be honest.” **“Satta”** “I got the term ‘satta vibrations’ from \[UK singer-songwriter\] Finley Quaye. I wrote it one morning outside Highbury & Islington tube station on my way back from a party, still kind of buzzing. Just sat on a bench watching my surroundings—seeing a woman cry, bare feds everywhere, pigeons. ‘Satta’ was also produced by Commissioner Gordon, too.” **“Party Hard Interlude”** “I referenced \[UK musician\] Donae’o on this. It was essential to have on there, like a nice little break. I knew I wanted the album to have interludes, skits, to go in and out, I wanted it to be a journey. We were all on copious amounts of mushrooms when we made this, so I felt it would be rude not to have a little ode to mycelium on there.” **“Dingaling”** “We all went to Anish’s \[Bhatt, UK producer known as Earbuds\] studio after being back from the woods; we met up and were going through the album. Anish showed us that tune and we all ended up just getting a bit waved and being there all night with our instruments out. Before we knew it we’d recreated \[his beat\]. Again, it’s a re-lick of Blak Twang \[2002 single ‘So Rotton’\] and 2Face’s \[Idibia, now known as 2Baba\] ‘African Queen,’ with my own little bit in the middle.” **“Maya”** “‘Maya’ for me is a mad one, because I\'ve never sung like that before, especially at the end where I\'m proper wailing. This was a time where I really just expressed myself freely. I don\'t do that often and am not able to do that often yet.” **“Man Made”** “This is probably the most overtly political tune, but to me it’s more spiritual. You can take the song literally, but also metaphorically: how these man-made seeds are being planted in society and in the collective. Materialism, consumerism, individualism—it\'s only once you’re able to shed these accessories that you actually start remembering what it is to be human.” **“Meditation”** “This song literally was a meditation. This track could have been like 15 minutes long; initially we recorded for over an hour. It’s meant to take you inside yourself. And with the 432 Hz as well, it\'s tranquil, to say the least. When you can actually submit to the sound and the frequency, and you\'re not distracted by anything else, you can actually just listen to it.” **“Poor Man Skit”** “I’m questioning the idea of what it is to be rich, to be successful in the modern world, and what it is we should be striving for. Concepts of happiness have kind of gotten distorted. This is really just delving into that—like what does ‘poor’ even mean? Is it the person with no money, or the person with no empathy, compassion, or connection?” **“Sinner”** “This one came from a slightly darker place. I played the bass on this one, which was sick; I came up with the bassline first and just built the tune around that. I was feeling quite sinful at the time, I guess—just questioning myself, my intentions, faith, morals—questioning everything, really.” **“Jimtastic Blues”** “This is a sentimental one. It\'s funny because it probably has the saddest lyrics, meaning, and sentiment on the album, but is maybe the most upbeat tune. It\'s one with Swindle; we’d made it in the woods, then Swindle took it away and added the brass elements at the end, which kind of took it up a notch. It seemed like the perfect way to end the album.\"

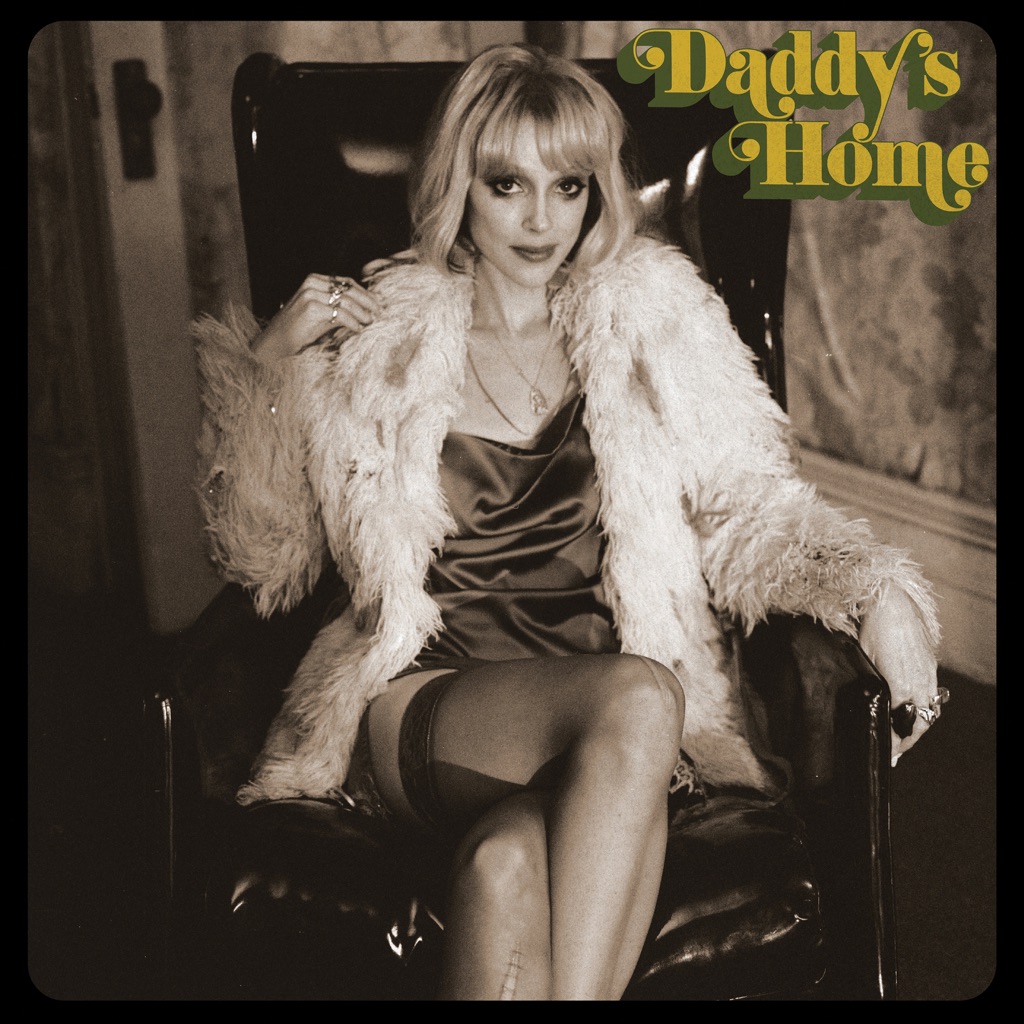

In the wake of 2017’s *MASSEDUCTION*, St. Vincent mastermind Annie Clark was in search of change. “That record was very much about structure and stricture—everything I wore was very tight, very controlled, very angular,” she tells Apple Music. “But there\'s only so far you can go with that before you\'re like, ‘Oh, what\'s over here?’” What Clark found was a looseness that came from exploring sounds she’d grown up with, “this kind of early-’70s, groove-ish, soul-ish, jazz-ish style in my head since I was a little kid,” she says. “I was raised on Steely Dan records and Stevie Wonder records like \[1973’s\] *Innervisions* and \[1972’s\] *Talking Book* and \[1974’s\] *Fulfillingness’ First Finale*. That was the wheelhouse that I wanted to play in. I wanted to make new stories with older sounds.” Recorded with *MASSEDUCTION* producer Jack Antonoff, *Daddy’s Home* draws heavily from the 1970s, but its title was inspired, in part, by recent events in Clark’s personal life: her father’s 2019 release from prison, where he’d served nearly a decade for his role in a stock manipulation scheme. It’s as much about our capacity to evolve as it is embracing the humanity in our flaws. “I wanted to make sure that even if anybody didn\'t know my personal autobiography that it would be open to interpretation as to whether Daddy is a father or Daddy is a boyfriend or Daddy is a pimp—I wanted that to be ambiguous,” she says. “Part of the title is literal: ‘Yeah, here he is, he\'s home!’ And then another part of it is ‘It’s 10 years later. I’ve done a lot in those 10 years. I have responsibility. I have shit I\'m seriously doing. It’s playing with it: Am I daddy\'s girl? I don\'t know. Maybe. But I\'m also Daddy, too, now.” Here, Clark guides us through a few of the album’s key tracks. **“Pay Your Way in Pain”** “This character is like the fixture in a 2021 psychedelic blues. And this is basically the sentiment of the blues: truly just kind of being down and out in a country, in a society, that oftentimes asks you to choose between dignity and survival. So it\'s just this story of one really bad fuckin’ day. And just owning the fact that truly what everybody wants in the world, with rare exception, is just to have a roof over their head, to be loved, and to get by. The line about the heels always makes me laugh. I\'ve been her, I know her. I\'ve been the one who people kind of go, ‘Oh, oh, dear. Hide the children\'s eyes.’ I know her, and I know her well.” **“Down and Out Downtown”** “This is actually maybe my favorite song on the record. I don\'t know how other people will feel about it. We\'ve all been that person who is wearing last night\'s heels at eight in the morning on the train, processing: ‘Oh, where have we been? What did I just do?’ You\'re groggy, you\'re sort of trying to avoid the knowing looks from other people—and the way that in New York, especially, you can just really ride that balance between like abandon and destruction. That\'s her; I\'ve been her too.” **“Daddy\'s Home”** “The story is really about one of the last times I went to go visit my dad in prison. If I was in national press or something, they put the press clippings on his bed. And if I was on TV, they\'d gather around in the common area and watch me be on Letterman or whatever. So some of the inmates knew who I was and presumably, I don\'t know, mentioned it to their family members. I ended up signing an autograph on a receipt because you can\'t bring phones and you couldn\'t do a selfie. It’s about watching the tables turn a little bit, from father and daughter. It\'s a complicated story and there\'s every kind of emotion about it. My family definitely chose to look at a lot of things with some gallows humor, because what else are you going to do? It\'s absolutely absurd and heartbreaking and funny all at the same time. So: Worth putting into a song.” **“Live in the Dream”** “If there are other touchpoints on the record that hint at psychedelia, on this one we\'ve gone completely psychedelic. I was having a conversation with Jack and he was telling me about a conversation he had with Bruce Springsteen. Bruce was just, I think anecdotally, talking about the game of fame and talking about the fact that we lose a lot of people to it. They can kind of float off into the atmosphere, and the secret is, you can\'t let the dream take over you. The dream has to live inside of you. And I thought that was wonderful, so I wrote this song as if you\'re waking up from a dream and you almost have these sirens talking to you. In life, there\'s still useful delusions. And then there\'s delusions that—if left unchecked—lead to kind of a misuse of power.” **“Down”** “The song is a revenge fantasy. If you\'re nice, people think they can take advantage of you. And being nice is not the same thing as being a pushover. If we don\'t want to be culpable to something, we could say, \'Well, it\'s definitely just this thing in my past,\' but at the end of the day, there\'s human culpability. Life is complicated, but I don\'t care why you are hurt. It\'s not an excuse to be cruel. Whatever your excuse is, you\'ve played it out.” **“…At the Holiday Party”** “Everybody\'s been this person at one time. I\'ve certainly been this person, where you are masking your sadness with all kinds of things. Whether it\'s dressing up real fancy or talking about that next thing you\'re going to do, whatever it is. And we kind of reveal ourselves by the things we try to hide and to kind of say we\'ve all been there. Drunk a little too early, at a party, there\'s a moment where you can see somebody\'s face break, and it\'s just for a split second, but you see it. That was the little window into what\'s going on with you, and what you\'re using to obfuscate is actually revealing you.”

Recorded in a brief moment of openness in the middle of a pandemic, "Speed The Day" continues the amazing run of recent Blue Orchids releases, albeit with a tinge of madness and more than a dollop of madness.

'Flock’ is the record that Jane Weaver always wanted to make, the most genuine version of herself, complete with unpretentious Day-Glo pop sensibilities, wit, kindness, humour and glamour. A consciously positive vision for negative times, a brooding and ethereal creation. The album features an untested new fusion of seemingly unrelated compounds fused into an eco-friendly hum; pop music for post-new-normal times. Created from elements that should never date, its pop music reinvented. Still prevalent are the cosmic sounds, but ‘Flock’ is a natural rebellion to the recent releases which sees her decidedly move away from conceptual roots in favour of writing pop music. Produced on a complicated diet of bygone Lebanese torch songs, 1980's Russian Aerobics records and Australian Punk. Amongst this broadcast of glistening sounds is ‘The Revolution Of Super Visions’, an untelevised Mothership connection, with Prince floating by as he plays scratchy guitar; it also features a funky whack-a-mole bass line and synth worms. It underlines the discordant pop vibe that permeates ‘Flock’ and concludes on ‘Solarised’, a super-catchy, totally infectious apocalypse, a radio-friendly groove for last dance lovers clinging together in an effort to save themselves before the end of the night. The musician’s exposure to an abundance of lost records served as a reminder that you still feel like an outsider in this world and that by overcoming fears you can achieve artistic freedom. Jane Weaver continues to metamorphosise…

As they worked on their third album, Wolf Alice would engage in an exercise. “We liked to play our demos over the top of muted movie trailers or particular scenes from films,” lead singer and guitarist Ellie Rowsell tells Apple Music. “It was to gather a sense of whether we’d captured the right vibe in the music. We threw around the word ‘cinematic’ a lot when trying to describe the sound we wanted to achieve, so it was a fun litmus test for us. And it’s kinda funny, too. Especially if you’re doing it over the top of *Skins*.” Halfway through *Blue Weekend*’s opening track, “The Beach,” Wolf Alice has checked off cinematic, and by its (suitably titled) closer, “The Beach II,” they’ve explored several film scores’ worth of emotion, moods, and sonic invention. It’s a triumphant guitar record, at once fan-pleasing and experimental, defiantly loud and beautifully quiet and the sound of a band hitting its stride. “We’ve distilled the purest form of Wolf Alice,” drummer Joel Amey says. *Blue Weekend* succeeds a Mercury Prize-winning second album (2017’s restless, bombastic *Visions of a Life*), and its genesis came at a decisive time for the North Londoners. “It was an amazing experience to get back in touch with actually writing and creating music as a band,” bassist Theo Ellis says. “We toured *Visions of a Life* for a very long time playing a similar selection of songs, and we did start to become robot versions of ourselves. When we first got back together at the first stage of writing *Blue Weekend*, we went to an Airbnb in Somerset and had a no-judgment creative session and showed each other all our weirdest ideas and it was really, really fun. That was the main thing I’d forgotten: how fun making music with the rest of the band is, and that it’s not just about playing a gig every evening.” The weird ideas evolved during sessions with producer Markus Dravs (Arcade Fire, Coldplay, Björk) in a locked-down Brussels across 2020. “He’s a producer that sees the full picture, and for him, it’s about what you do to make the song translate as well as possible,” guitarist Joff Oddie says. “Our approach is to throw loads of stuff at the recordings, put loads of layers on and play with loads of sound, but I think we met in the middle really nicely.” There’s a Bowie-esque majesty to tracks such as “Delicious Things” and “The Last Man on Earth”; “Smile” and “Play the Greatest Hits” were built for adoring festival crowds, while Rowsell’s songwriting has never revealed more vulnerability than on “Feeling Myself” and the especially gorgeous “No Hard Feelings” (“a song that had many different incarnations before it found its place on the record,” says Oddie. “That’s a testament to the song. I love Ellie’s vocal delivery. It’s really tender; it’s a beautiful piece of songwriting that is succinct, to the point, and moves me”). On an album so confident in its eclecticism, then, is there an overarching theme? “Each song represents its own story,” says Rowsell. “But with hindsight there are some running themes. It’s a lot about relationships with partners, friends, and with oneself, so there are themes of love and anxiety. Each song, though, can be enjoyed in isolation. Just as I find solace in writing and making music, I’d be absolutely chuffed if anyone had a similar experience listening to this. I like that this album has different songs for different moods. They can rage to ‘Play the Greatest Hits,’ or they can feel powerful to ‘Feeling Myself,’ or ‘they can have a good cathartic cry to ‘No Hard Feelings.’ That would be lovely.”