Les Inrocks' Top 100 Albums of 2020

[Best of musique 2020] Si l’année a été, par la force des choses, pauvre en concerts, elle n’en a pas moins été riche en nouvelles prouesses discographiques. Voici le choix de la rédaction des Inrockuptibles.

Published: December 01, 2020 15:53

Source

It took Kelly Lee Owens 35 days to write the music for her second album. “I had a flood of creation,” she tells Apple Music. “But this was after three years that included loss, learning how to deal with loss and how to transmute that loss into something of creation again. They were the hardest three years of my life.” The Welsh electronic musician’s self-titled 2017 debut album figured prominently on best-of-the-year lists and won her illustrious fans across music and fashion. It’s the sort of album you recommend to people you’d like to impress. Its release, however, was clouded by issues in Owens’ personal life. “There was a lot going on, and it took away my energy,” she says. “It made me question the integrity of who I was and whether it was ego driving certain situations. It was so tough to keep moving forward.” Fortunately, Owens rallied. “It sounds hippie-dippie, but this is my purpose in life,” she says. “To convey messages via sounds and to connect to other people.” Informed by grief, lust, anxiety, and environmental concerns, *Inner Song* is an electronic album that impacts viscerally. “I allowed myself to be more of a vessel that people talk about,” she says. “It’s real. Ideas can flow through you. In that 35-day period, I allowed myself to tap into any idea I had, rather than having to come in with lyrics, melodies, and full production. It’s like how the best ideas come when you’re in the shower: You’re usually just letting things be and come through you a bit more. And then I could hunker down and go in hard on all those minute nudges on vocal lines or kicks or rhythmical stuff or EQs. Both elements are important, I learned. And I love them both.” Here, Owens treats you to a track-by-track guide to *Inner Song*. **Arpeggi** “*In Rainbows* is one of my favorite albums of all time. The production on it is insane—it’s the best headphone *and* speaker listening experience ever. This cover came a year before the rest of the album, actually. I had a few months between shows and felt like I should probably go into the studio. I mean, it’s sacrilege enough to do a Radiohead cover, but to attempt Thom’s vocals: no. There is a recording somewhere, but as soon as I heard it, I said, ‘That will never been heard or seen. Delete, delete, delete.’ I think the song was somehow written for analog synths. Perhaps if Thom Yorke did the song solo, it might sound like this—especially where the production on the drums is very minimal. So it’s an homage to Thom, really. It was the starting point for me, and this record, so it couldn’t go anywhere else.” **On** “I definitely wanted to explore my own vocals more on this album. That ‘journey,’ if you like, started when Kieran Hebden \[Four Tet\] requested I play before him at a festival and afterwards said to me, ‘Why the fuck have you been hiding your vocals all this time under waves of reverb, space echo, and delay? Don’t do that on the next album.’ That was the nod I needed from someone I respect so highly. It’s also just been personal stuff—I have more confidence in my voice and the lyrics now. With what I’m singing about, I wanted to be really clear, heard, and understood. It felt pointless to hide that and drown it in reverb. The song was going to be called ‘Spirit of Keith’ as I recorded it on the day \[Prodigy vocalist\] Keith Flint died. That’s why there are so many tinges of ’90s production in the drums, and there’s that rave element. And almost three minutes on the dot, you get the catapult to move on. We leap from this point.” **Melt!** “Everyone kept taking the exclamation mark out. I refused, though—it’s part of the song somehow. It was pretty much the last song I made for the album, and I felt I needed a techno banger. There’s a lot of heaviness in the lyrics on this album, so I just wanted that moment to allow a letting loose. I wanted the high fidelity, too. A lot of the music I like at the moment is really clear, whereas I’m always asking to take the top end off on the snare—even if I’m told that’s what makes something a snare. I just don’t really like snares. The ‘While you sleep, melt, ice’ lyrics kept coming into my head, so I just searched for ‘glacial ice melting’ and ‘skating on ice’ or ‘icicles cracking’ and found all these amazing samples. The environmental message is important—as we live and breathe and talk, the environment continues to suffer, but we have to switch off from it to a certain degree because otherwise you become overwhelmed and then you’re paralyzed. It’s a fine balance—and that’s why the exclamation mark made so much sense to me.” **Re-Wild** “This is my sexy stoner song. I was inspired by Rihanna’s ‘Needed Me,’ actually. People don’t necessarily expect a little white girl from Wales to create something like this, but I’ve always been obsessed with bass so was just wanting a big, fat bassline with loads of space around it. I’d been reading this book *Women Who Run With the Wolves* \[by Clarissa Pinkola\], which talks very poetically about the journey of a woman through her lifetime—and then in general about the kind of life, death, and rebirth cycle within yourself and relationships. We’re always focused on the death—the ending of something—but that happens again and again, and something can be reborn and rebirthed from that, which is what I wanted to focus on. She \[Pinkola\] talks about the rewilding of the spirit. So often when people have depression—unless we suffer chronically, which is something else—it’s usually when the creative soul life dies. I felt that mine was on the edge of fading. Rewilding your spirit is rewilding that connection to nature. I was just reestablishing the power and freedoms I felt within myself and wanting to express that and connect people to that inner wisdom and power that is always there.” **Jeanette** “This is dedicated to my nana, who passed away in October 2019, and she will forever be one of the most important people in my life. She was there three minutes after I was born, and I was with her, holding her when she passed. That bond is unbreakable. At my lowest points she would say, ‘Don’t you dare give this up. Don’t you dare. You’ve worked hard for this.’ Anyway, this song is me letting it go. Letting it all go, floating up, up, and up. It feels kind of sunshine-y. What’s fun for me—and hopefully the listener—is that on this album you’re hearing me live tweaking the whole way through tracks. This one, especially.” **L.I.N.E.** “Love Is Not Enough. This is a deceivingly pretty song, because it’s very dark. Listen, I’m from Wales—melancholy is what we do. I tried to write a song in a minor key for this album. I was like, ‘I want to be like The 1975’—but it didn’t happen. Actually, this is James’ song \[collaborator James Greenwood, who releases music as Ghost Culture\]. It’s a Ghost Culture song that never came out. It’s the only time I’ve ever done this. It was quite scary, because it’s the poppiest thing I’ve probably done, and I was also scared because I basically ended up rewriting all the lyrics, and re-recorded new kick drums, new percussion, and came up with a new arrangement. But James encouraged all of it. The new lyrics came from doing a trauma body release session, which is quite something. It’s someone coming in, holding you and your gaze, breathing with you, and helping you release energy in the body that’s been trapped. Humans go through trauma all the time and we don’t literally shake and release it, like animals do. So it’s stored in the body, in the muscles, and it’s vital that we figure out how to release it. We’re so fearful of feeling our pain—and that fear of pain itself is what causes the most damage. This pain and trauma just wants to be seen and acknowledged and released.” **Corner of My Sky (feat. John Cale)** “This song used to be called ‘Mushroom.’ I’m going to say no more on that. I just wanted to go into a psychedelic bubble and be held by the sound and connection to earth, and all the, let’s just say, medicine that the earth has to offer. Once the music was finished, Joakim \[Haugland, founder of Owens’ label, Smalltown Supersound\] said, ‘This is nice, but I can hear John Cale’s voice on this.’ Joakim is a believer that anything can happen, so we sent it to him knowing that if he didn’t like it, he wouldn’t fucking touch it. We had to nudge a bit—he’s a busy man, he’s in his seventies, he’s touring, he’s traveling. But then he agreed and it became this psychedelic lullaby. For both of us, it was about the land and wanting to go to the connection to Wales. I asked if he could speak about Wales in Welsh, as it would feel like a small contribution from us to our country, as for a long time our language was suppressed. He then delivered back some of the lyrics you hear, but it was all backwards. So I had to go in and chop it up and arrange it, which was this incredibly fun challenge. The last bit says, ‘I’ve lost the bet that words will come and wake me in the morning.’ It was perfect. Honestly, I feel like the Welsh tourist board need to pay up for the most dramatic video imaginable.” **Night** “It’s important that I say this before someone else does: I think touring with Jon Hopkins influenced this one in terms of how the synth sounded. It wasn’t conscious. I’ve learned a lot of things from him in terms of how to produce kicks and layer things up. It’s related to a feeling of how, in the nighttime, your real feelings come out. You feel the truth of things and are able to access more of yourself and your actual soul desires. We’re distracted by so many things in the daytime. It’s a techno love song.” **Flow** “This is an anomaly as it’s a strange instrumental thing, but I think it’s needed on the album. This has a sample of me playing hand drum. I actually live with a sound healer, so we have a ceremony room and there’s all sorts of weird instruments in there. When no one was in the house, I snuck in there and played all sorts of random shit and sampled it simply on my iPhone. And I pitched the whole track around that. It fits at this place on the record, because we needed to come back down. It’s a breathe-out moment and a restful space. Because this album can truly feel like a journey. It also features probably my favorite moment on the album—when the kick drums come back in, with that ‘bam, bam, bam, bam.’ Listen and you’ll know exactly where I mean.” **Wake-Up** “There was a moment sonically with me and this song after I mixed it, where the strings kick in and there’s no vocals. It’s just strings and the arpeggio synth. I found myself in tears. I didn’t know that was going to happen to me with my own song, as it certainly didn’t happen when I was writing it. What I realized was that the strings in that moment were, for me, the earth and nature crying out. Saying, ‘Please, listen. Please, see what’s happening.’ And the arpeggio, which is really chaotic, is the digital world encroaching and trying to distract you from the suffering and pain and grief that the planet is enduring right now. I think we’re all feeling this collective grief that we can’t articulate half the time. We don’t even understand that we are connected to everyone else. It’s about tapping into the pain of this interconnected web. It’s also a commentary on digital culture, which I am of course a part of. I had some of the lyrics written down from ages ago, and they inspired the song. ‘Wake up, repeat, again.’ Just questioning, in a sense, how we’ve reached this place.”

Atlanta underground rock provocateurs Black Lips have announced that their new LP The Black Lips Sing In A World That’s Falling Apart is set for release January 24th on Fire Records/Vice. Boasting an unapologetic southern-fried twang, the twelve-track collection marks the quintet’s most pronounced dalliance with country music yet, with a clang and harmony that is unmistakably the inimitable sound and feel of the Black Lips. While the songcraft and playing is more sophisticated, Black Lips were determined to return to the raw sound roots that marked their early efforts. Recorded and co-produced with Nic Jodoin at Laurel Canyon’s legendary, newly reopened Valentine Recording Studios (which played host to Beach Boys and Bing Crosby before shuttering in 1979) without Pro-Tools and other contemporary technology, the band banged the album out directly to tape quickly and cheaply, resulting in their grimiest, most dangerous, and best collection of songs since the aughts. Like The Byrds, who flirted with pastoral aesthetics before going all-out with the radical departure that was Sweetheart of The Rodeo, the Black Lips have been skirting the edges of country since “Sweet Kin” and “Make It” from their eponymous debut. But eschewing Graham Parson’s earnestness, Black Lips are careful not to hint at authenticity, wisely treading into their unfeigned rustic romance with the winking self-awareness of Bob Dylan’s “You Ain’t Goin Nowhere,” Rolling Stones “Dear Doctor,” or The Velvet Underground’s “Lonesome Cowboy Bill.” The band’s stylistic evolution and matured approach to musicianship and writing is, in part, due to the seismic lineup shifts they have undergone over the last half-decade. Worn down after a decade of prolific touring and recording, longtime guitarist Ian St Pé left the group in 2014, followed shortly thereafter by original drummer Joe Bradley. Jeweler/actress (and now Gucci muse) Zumi Rosow, whose sax skronk, flamboyant style, and wild stage presence had augmented the team before the duo’s departure, assumed a bigger writing and performance role in their absence. Soon drummer Oakley Munson from The Witnesses brought a new backbeat and unique backing vocal harmony into the fold. Last year the quintet was rounded out by guitarist Jeff Clarke of Demon’s Claws. The newly forged partnership, all of whom collaborate as songwriters, vocalists, and instrumentalists, has breathed new life into their sound. The result is akin to the radiance of the impulsive, wild nights where you find yourself two-stepping into the unknown.

You don’t need to know that Fiona Apple recorded her fifth album herself in her Los Angeles home in order to recognize its handmade clatter, right down to the dogs barking in the background at the end of the title track. Nor do you need to have spent weeks cooped up in your own home in the middle of a global pandemic in order to more acutely appreciate its distinct banging-on-the-walls energy. But it certainly doesn’t hurt. Made over the course of eight years, *Fetch the Bolt Cutters* could not possibly have anticipated the disjointed, anxious, agoraphobic moment in history in which it was released, but it provides an apt and welcome soundtrack nonetheless. Still present, particularly on opener “I Want You to Love Me,” are Apple’s piano playing and stark (and, in at least one instance, literal) diary-entry lyrics. But where previous albums had lush flourishes, the frenetic, woozy rhythm section is the dominant force and mood-setter here, courtesy of drummer Amy Wood and former Soul Coughing bassist Sebastian Steinberg. The sparse “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” is backed by drumsticks seemingly smacking whatever surface might be in sight. “Relay” (featuring a refrain, “Evil is a relay sport/When the one who’s burned turns to pass the torch,” that Apple claims was excavated from an old journal from written she was 15) is driven almost entirely by drums that are at turns childlike and martial. None of this percussive racket blunts or distracts from Apple’s wit and rage. There are instantly indelible lines (“Kick me under the table all you want/I won’t shut up” and the show-stopping “Good morning, good morning/You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in”), all in the service of channeling an entire society’s worth of frustration and fluster into a unique, urgent work of art that refuses to sacrifice playfulness for preaching.

Aveu, fiction et constat. Ainsi semble évoluer la trajectoire dessinée par Julien Gasc au fil de ses disques. Si Cerf, Biche et Faon prenait la forme d'un journal intime et Kiss Me, You Fool ! celle d'un recueil de fictions, L'Appel de la Forêt clôt cette trilogie en un dialogue tendre et spontané, abordant le présent avec clairvoyance par des mélodies aux reflets lumineux. Plus aventureux que ses prédécesseurs, ancrés respectivement dans le sud de la France et à Londres, ce troisième chapitre offre une vision kaléidoscopique, multipliant les géographies et les temporalités pour mieux s'inscrire dans l'instant. Par une collection de danses aux diverses origines, Julien se place au centre du quotidien - l'embrasse, le sublime et l'appelle à une transfiguration pour échapper à son imminent désastre. Sa voix circule à travers cet horizon morcelé, elle est nue et immédiate, parfois si blanche qu'elle disparaît, laissant la place à son interlocuteur, comme une invitation à occuper l'espace façonné par ses ritournelles. Émancipé de son costume de dandy, les rares fois où il s'en pare sont pour mieux s'en jouer. L'adresse se veut franche, et avant tout bienveillante. Plus qu'un chant d'amour, c'est une ode à la liberté et à la pleine conscience de notre condition humaine qui se déploie devant nous. Une invitation sans cynisme à quitter notre masque d'animal social et décoloniser le monde qui nous entoure - cesser de vouloir posséder coûte que coûte et laisser libres ceux que l'on aime. Ce disque est un compagnon de route, sans dogmes ni préceptes, à la devise simple : Garde la joie. Confession, fiction, and observation. This is how the trajectory drawn by Julien Gasc seems to evolve from one album to the next. While Cerf, Biche et Faon took the form of a diary and Kiss Me, You Fool! that of a collection of stories, L'Appel de la Forêt concludes this trilogy in a tender and spontaneous dialogue, broaching the present with clairvoyance through melodies with bright glimmers. More adventurous than its predecessors, which respectively took root in the south of France and in London, this third chapter offers a kaleidoscopic vision, multiplying geographies and temporalities to ingrain itself in the moment all the better. Through a collection of dances of diverse origins, Julien places himself at the heart of the everyday – embracing it, sublimating it, and calling for a transfiguration to escape its imminent disaster. His voice circulate through this fragmented horizon; it is raw and immediate, sometimes so stark that it disappears, making way for its interlocutor, like an invitation to occupy the space shaped by his ritornello. Emancipated from his dandy’s costume, the rare moments where he puts it on again are to more effectively elude it. The address is deliberately frank and above all benevolent. Beyond an amorous chant d’amour, it is an ode to freedom and to the full awareness of our human condition that unfolds before us. An invitation, devoid of cynicism, to take off of our ‘social animal’ mask and decolonise the world around us – to stop wanting to possess at all costs and let those we love be free. This album is a roadside companion, with no dogma or precepts, and a simple motto: Stay joyful.

“My language for producing music is way more diverse now and allows me to create different-sounding music,” Yaeji tells Apple Music. With her mesmerizing voice and chill vibe, the New York (by way of South Korea) DJ, producer, and multimedia artist Kathy Yaeji Lee is a unique presence in dance music. Her songs are celebratory yet meditative—influenced by house, R&B, and hip-hop. They’re reflective of her dual heritage and intercontinental mindset, ranging from stunt anthems (“raingurl,” “drink i’m sippin on”) to her lowercased cover of Drake’s “Passionfruit.” Recorded before inking a deal with XL (the home to Tyler, The Creator and other sonic misfits), *WHAT WE DREW 우리가 그려왔던* is a personal and intimate mixtape she likens to a musical diary. Sung-spoken in whispery tones in English and Korean, Yaeji’s observations are sharp, whether yearning for stillness (“IN PLACE 그 자리 그대로”), indulging in simple pleasures (“WAKING UP DOWN,” “MONEY CAN’T BUY”), or getting in her feelings (“WHAT WE DREW 우리가 그려왔던,” “IN THE MIRROR 거울”). It also represents a time when she soaked up new production techniques and was inspired by 2000s bossanova-influenced electronica, ’80s-’90s Korean music (curated by her parents, who live outside of Seoul), R&B, and soul. Below Yaeji walks through each song on her mixtape. “Every track is a bit different,” she says “I really hope it brings a little bit of positivity.” **MY IMAGINATION 상상** “I wrote it with the intention of warming people up to what I do. I repeat a lot in this song in Korean: ‘If you follow me in this moment I chose, right in this moment.’ And I repeat ‘my imagination’ over and over in Korean. I wanted it to feel really smooth and continuous, almost cyclical, but in a way that felt relaxing. It’s a way to ease you into the next song, which is quite emotional for me.” **WHAT WE DREW 우리가 그려왔던** “It’s one of the older songs on the mixtape. It was written at a very emotional time, when I was going through a lot of transitions and growing pains. In the midst of all that darkness, I was able to stay positive because of family around me. I think that notion of family and unconditional love is so Korean to me. Thinking of Korea gets me very emotional. My dad messaged \[himself scatting\] to me on KakaoTalk \[a Korean messaging app\] a year and a half ago. He said, ‘I have a song idea for you. Use it if it helps you in any way.’ When I finished up the mixtape, I realized it would be so perfect and meaningful for the track, so I added it in.” **IN PLACE 그 자리 그대로** “It was written around the time me and my friends were watching a video of Stevie Wonder performing live with a talk box \[a cover of The Carpenters’ ‘Close to You’ on *The David Frost Show* in 1972\]. We were listening to that a lot and it was stuck in my head. I loved how the talk box sounded; it’s so warm and fuzzy, his performance is so playful. It also has such a robotic quality. I wanted to create this feeling but using a completely different technique. I layered nine different vocal tracks to create that harmony you hear in the intro. It affected each layer differently and holds a similar feeling that I received when I heard Stevie Wonder. Emotionally, it was written when I didn’t want things to change. Just for a moment, I wanted things to stay still. It’s about yearning for stillness.” **WHEN I GROW UP** “It’s an idea I’ve been settling and meditating on for a long time. It’s the concept of a younger me, or a younger person, imagining what it’s like to become an adult. There’s another perspective in the song where it’s me, the adult version of myself, telling my younger self: ‘Unfortunately, when you grow older, you’re fearful for a lot of things. You don’t want to get hurt. You suppress your emotions and pretend like everything is OK.’ All these things I had no idea would happen when I was younger; it’s my reality, our reality, as adults. It’s a kind of back and forth about that.” **MONEY CAN’T BUY (feat. Nappy Nina)** “It’s the really playful one. It’s purely about friendship and being goofy and positive. The thing I repeat in Korean: ‘What I want to do is eat rice and soup.’ It’s pretty common for me. I’ll put the rice in the soup and mix it up, so it becomes like a porridge. I’m repeating that and it’s followed by ‘What I want, money can’t buy.’ Friendship isn’t something that’s quantifiable or measurable with materialism. It’s completely magical and far more special than what can be described. It’s like an appreciation song for friendship. It’s kind of perfect that Nappy Nina was featured on it. I had met her last minute. She’s a friend of my mixing engineer. She came in and recorded immediately; we realized we had mutual friends, so now we keep in touch. That lends itself well to the message of the song.” **FREE INTERLUDE (feat. Lil Fayo, Trenchcoat & Sweet Pea)** “It felt really liberating to include this in the mixtape. It was a completely natural, goofy hang with my friends. We were having fun making music together, kind of first takes of freestyles. The spirit of our hang and our friendship is really in that track. It’s a very meaningful one for me.” **SPELL 주문 (feat. YonYon & G.L.A.M.)** “It was a joy to put together. It started as a bare-bones demo that I had lyrics to. When I was writing it, I was thinking of the experience of performing onstage to a sea of people that you’ve never met before and sharing your most intimate thoughts and experiences. It’s casting a spell; you’re sharing something that only you know, and then they’re applying it in whatever way it means for themselves. I thought of YonYon because we went to the same middle school in Japan when I was living there for one year. We’ve stayed in touch since, and she’s doing great with music in Japan, so she’s always on my mind to collaborate, and this felt perfect. G.L.A.M. is a close friend of a friend. I had also played shows with her a long time ago when I moved to New York, so I thought she was also another perfect collaborator.” **WAKING UP DOWN** “Purely a feel-good song. There’s a moment of questioning and hesitation. The Korean verses embody that side of it. The parts in English are about the feeling I had when I had all of these basic life routines down and felt healthy, mentally and physically. It’s a song to groove to and hopefully feel inspired by. And also, not to get too wrapped up in the literal things: cooking, waking up, hydrating. Yes, it’s important, but the Korean lyrics remind you: Don’t forget, there are these bigger themes in life you have to think about.” **IN THE MIRROR 거울** “It’s the dramatic one. I really wanted to try singing in a way that feels like I’m unleashing pent-up energy. It was written after a difficult tour that mentally and physically stretched me quite thin. It came from a thought I had while I was looking in the mirror in the airplane bathroom. I think being up in the air makes you more emotional. I don’t know how true that is, but I definitely feel that way. I was really in my feelings and really upset.” **THE TH1NG (feat. Victoria Sin & Shy One)** “I want to credit Vic and Shy because I knew I wanted to work with them. I sent them a pretty bare-bones demo, just synth and samples. They’re partners and based in London. Vic is an incredible performing artist and Shy is an incredible DJ. Vic came up with all of the lyrics and vocals. They wrote it on their birthday, stayed at home alone in their bedroom, surrounded themselves with plants, meditated, and had an introspective stream of consciousness of what is this ‘TH1NG.’ It sounds really abstract, but they explore the concept. Shy did a lot of the production on it and built on the little things I sent them.” **THESE DAYS 요즘** “Do you know the \[anime\] genre Slice of Life? It feels like a Slice of Life song, which is, the way I understand it, it’s mundane day-to-day lifestyle about meditating on time. I would visually describe it as feeling like sitting on a stoop with your friends on a nice fall afternoon sharing stories with each other about how you’re doing. That kind of feeling. It’s not overly dramatic or purposeful; it’s a mood.” **NEVER SETTLING DOWN** “It’s a song about making a determined promise to myself to never settle. I should always stay open-minded, to continue unlearning and learning things, to shed things that felt toxic to me in the past. I say things like ‘I’m never shooting the shit,’ which is a balance of not taking myself too seriously but also that I’m not playing, I’m working every day. It’s a confident track, and I hope it brings confidence to other people that hear it. At the end, the breaks come in, and it feels like a big release, like a moment where you’re taking flight or dancing like crazy, alone in your room. That’s how I wanted to end the mixtape.”

Caribou’s Dan Snaith is one of those guys you might be tempted to call a “producer” but at this point is basically a singer-songwriter who happens to work in an electronic medium. Like 2014’s *Our Love* and 2010’s *Swim*, the core DNA of *Suddenly* is dance music, from which Snaith borrows without constraint or historical agenda: deep house on “Lime,” UK garage on “Ravi,” soul breakbeats on “Home,” rave uplift on “Never Come Back.” But where dance tends to aspire to the communal (the packed floor, the oceanic release of dissolving into the crowd), *Suddenly* is intimate, almost folksy, balancing Snaith’s intricate productions with a boyish, unaffected singing style and lyrics written in nakedly direct address: “If you love me, come hold me now/Come tell me what to do” (“Cloud Song”), “Sister, I promise you I’m changing/You’ve had broken promises I know” (“Sister”), and other confidences generally shared in bedrooms. (That Snaith is singing a lot more makes a difference too—the beat moves, but he anchors.) And for as gentle and politely good-natured as the spirit of the music is (Snaith named the album after his daughter’s favorite word), Caribou still seems capable of backsliding into pure wonder, a suggestion that one can reckon the humdrum beauty of domestic relationships and still make time to leave the ground now and then.

In the months leading up to his first tour date supporting 2019’s *Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest*, Bill Callahan was struck by what he describes to Apple Music as “the perfect inspiration for the perfect goal”: Before he left home, he’d try to write and record another album. “I\'m the type of person that can only do one thing at a time,” he says. “I just knew that if I didn\'t finish it before the tour, then it would be a year before I could even think about working on these songs. And I knew that if I did finish it, I would feel like a million bucks.” So Callahan drew up some deadlines for himself and began finishing and fleshing out songs he had lying around, work he hadn’t been able to find a home for previously. *Gold Record* is the short story collection to his other LPs\' novels—a set of self-contained worlds and character studies every bit as detailed and disarming as anything the 54-year-old singer-songwriter has released to date. It also includes an update to 1999’s “Let’s Move to the Country,” a song (originally under his Smog pseudonym) that was calling out for some added perspective. “I have a natural inclination to try to make a narrative out of a whole record,” he says. “But this time, it’s really just a bunch of songs that stand on their own, not really connected to the others. That\'s why I called it *Gold Record*—it’s kind of like a greatest hits record, though singles record is maybe more accurate.” Here, he takes us inside every song on the album. **Pigeons** “I noticed when I got married that I finally understood this word ‘community.’ I was always hearing it, but it never really meant anything to me. But then when I got married—and especially when I had a kid—that word became my favorite word. It meant so much. This song is just about the feeling of marriage, how it connects you to life processes, to birth and death and your neighbors. I think if you have a partner, you can\'t be the selfish person you used to be, because there\'s actually someone listening to you when you\'re being that way, so it kind of steers you into being more considerate and a more generous person. Because when someone is hearing what you\'re saying, then you are hearing what you\'re saying for the first time. That leads to being married to the world, I think.” **Another Song** “I actually wrote that song for a producer who contacted me. They were making a covers record with Emmylou Harris, and so I wrote that for her. The record never happened, so I just used it for myself. I think that one has a different feel because I got \[guitarist\] Matt Kinsey to play bass on that one song, and he has a pretty distinct and melodic kind of up-front way of playing bass.” **35** “It\'s definitely an experience that I had, where I felt like I’d read all the great books and would just be disappointed or feel alienated from any new authors that I would try to read. In your late teens and early twenties is when you read great books and you kind of take them on as if they are books about you, or books that reflect your inner world perfectly. But whenever I try to go back to those, I\'m just not interested. I look at it as a good thing: You are kind of unformed in your twenties, and then hopefully, by the time you hit 30, you are somewhat formed. I think that it\'s like you\'re getting your wings to fly. When you\'re unformed, when you\'re a fledgling person, you can\'t really express a lot. I think it\'s a good thing to have that feeling of not connecting necessarily with art, because it prompts you to work on your own.” **Protest Song** “That song is probably the oldest new song on the record. I started it ten years ago, got the idea and just never finished it. But I considered putting it on *Shepherd*, just as I considered putting it on \[2013’s\] *Dream River*. It didn\'t seem to fit either of those. It was kind of a revenge song. At the time I used to watch a lot of late-night shows, just because I was curious about what kind of music gets on there. At least at the time, it was almost invariably the worst people out there, in my opinion. So it was just kind of like a revenge fantasy, on the musicians that are performing. That accent I use is just a film noir that lives inside me.” **The Mackenzies** “When I bought my first car 30 years ago, the couple who was selling it invited me into their house and made me a cocktail. I just kind of hung out with them for a while, which was just a very pleasant and unusual thing. It was a used Dodge minivan, and he was a Dodge mechanic. I figured it was probably the safest person to buy a car from, a mechanic. They were maternal and paternal, to a complete stranger, me just coming out to their house. They also had one of those very homey houses that some people have. Some people master the art of comfort—they have the best couches and chairs and shag carpet and stuff. That\'s what stuck with me—their warmth, their instant warmth. But maybe that\'s because I was giving them a check for five grand. The song is fairly new, but those people had been in my head for a long time. I guess I always believe that if it\'s something you always think about, then that means it\'s very important—it\'s a good way to find out about what you should be writing about, if you have recurring thoughts.” **Let’s Move to the Country** “I always like playing it live, but I kind of stopped and then resurrected it a couple of years ago on tour. It seemed like there was something missing, and because of developments in my personal life, it just seemed like I should write a new chapter to the song. The original is from the perspective of someone who can\'t even say the words ‘baby’ or ‘family.’ The updated version is someone that can. It\'s sort of a mystery, and deciding if you\'re going to have a second one or not is kind of almost as big a decision as having one kid, because it could be looked at as whether or not you\'re happy having kids. I\'m totally not saying that people that only have one kid aren\'t happy having kids, but by having this second kid, you\'re definitely making some kind of deeper commitment, I think. You\'re saying, ‘Okay, I\'m willing to get deeper into this.’” **Breakfast** “I think it just started from an image I had of a woman making breakfast for her man—doing that kind of affectionate thing, but not having affection for the person. What are the dynamics of that? What\'s going on in that type of relationship? Why is she still feeding him and feeding the relationship when she\'s not happy? I was trying to explore that kind of dynamic that relationships can get into sometimes. I also find it interesting with couples: who gets up first and the way that changes sometimes, depending on what\'s going on. Who\'s getting out of bed first, and who\'s laying in bed longer?” **Cowboy** “It’s kind of nostalgic for the way TV used to be. There would be a later movie, and then later there was a late, late movie. If you were staying up to watch that, it would usually be after *The Tonight Show*. That meant something. It meant you\'re up pretty late, for whatever reason. You might be being irresponsible, or you might just be indulging yourself. Now that TV is on demand, I don\'t think anyone really watches late-night shows at night anymore—they just watch the highlights the next day. So on one level, it\'s about that loss of sense of place that TV used to give you, because it was a much more fixed thing. And that kind of correlates to watching a Western, because that\'s about a time that is also gone. I was just thinking about that, the time of your life when you can just watch a movie at two in the morning.” **Ry Cooder** “He\'s someone that I\'ve been familiar with maybe since his \[1984\] *Paris, Texas* soundtrack, but I hadn\'t really explored his records very much. Maybe three or four years ago I started digging into all of them and was really being blown away by how great so many of his records are and how different each one is and how he really uplifts and kind of puts a spotlight on international musicians. Unlike \[1986’s\] *Graceland*—where people think that Paul Simon kind of was just using those people—Ry Cooder really seems to want people to know about all this other kind of music. If you watch or read an interview with him from now, he\'s totally stoked about music and not at all jaded or bored or anything. I just thought that he deserved a ballad, a tribute. Because I think he\'s great.” **As I Wander** “I tried to make it a song about everything that I possibly could. I was trying to sum up human existence and sum up the record, even though it wasn\'t written with that intent necessarily. All the perspectives on the record are very distinct, and limited to just that narrative. But with ‘As I Wander,’ I tried to hold all narratives at the same time. Just like a great big spaghetti junction where all the highways meet up and swirl around.”

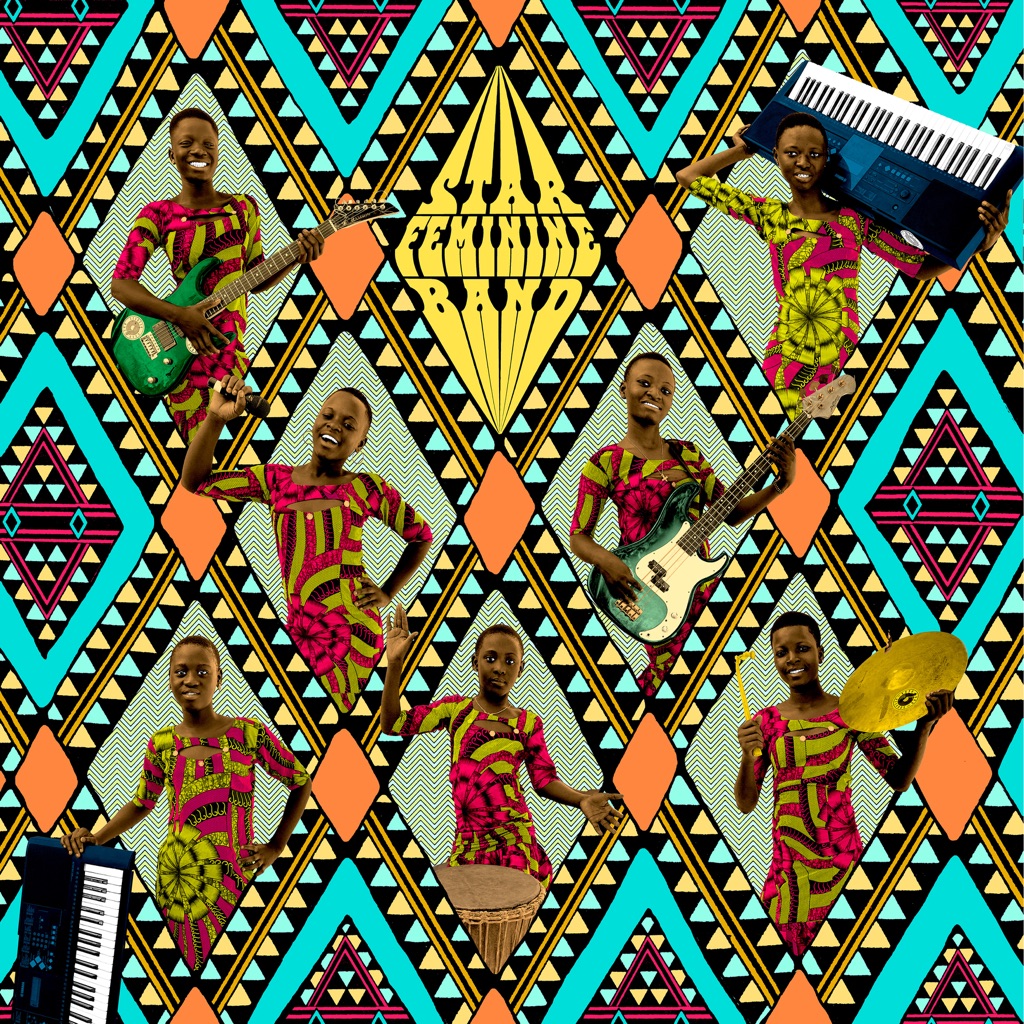

(ENGLISH TEXT BELOW) "Oh femme, femme africaine Oh femme, femme béninoise Femme noir, lève toi, ne dort pas Oh femme noir, lève toi ne dort pas Tu peu devenir, président de la république Tu peu devenir, premier ministre du pays Lève-toi, il faut faire, quelque chose Femme africaine, soit indépendante Le pays a besoin de nous, allons à l’école L’Afrique a besoin de toi, il faut travailler Le monde a besoin de nous, levons nous allons défendre Femme africaine, soit indépendante » Star Feminine Band Sans crier gare, une formation de jeunes filles originaires d’une région reculée du Bénin, bouscule l’idiome rock garage avec une fraîcheur, une inventivité et une énergie stupéfiantes, jouant juste, haut et fort. Au cours de la première partie du vingtième siècle, le découpage de la majorité de l’Afrique par les puissances européennes introduit une modernité forcée un peu partout sur le continent. Dans les villes et les ports, le continent bruisse d’une agitation nouvelle alors que l’électricité commence sa timide apparition. A la faveur de transports maritimes en plein essor, les 78 tours ramenés par les marins latino-américains, en particulier cubains, mais aussi par les soldats ou les colons européens, influencent durablement de nouvelles orientations musicales le long des côtes africaines. On assiste ainsi progressivement à une réinterprétation de ces musiques cubaines, mais aussi caribéennes, jazz ou rhythm’n’blues. Originaires en grande partie d’Afrique, ces musiques revenues des Amériques font office de vérité naturelle sur le continent. Certains orchestres décident ainsi de « réafricaniser » ces musiques afro-cubaines et noires américaines écoutées sur dans les ports, sur la place publique ou diffusées sur les ondes. Les bars et dancings, ainsi que les associations de jeunesse jouent également un rôle important dans la diffusion et le développement de ces musiques. A l’image de ce qui se passe dans la plupart des villes d’Afrique, de nombreux orchestres voient le jour au cours des années 1950 et 1960. Ils incarnent des symboles de modernité, au même titre que l’électricité, les automobiles et le cinéma. L’euphorie des années qui suivent l’indépendance est donc mise en musique par ces orchestres. Ceux-ci sont en partie influencés par les formations de danse ghanéennes qui sillonnent alors toutes les grandes villes du Golfe du Bénin, du Nigeria jusqu’au Liberia. Les échanges culturels sont fertiles. Au début des années 1960, les riches traditions locales du Bénin, à commencer par les musiques de transe et de cérémonie vaudou commencent à fusionner avec l’afro-cubain, la rumba congolaise et le high-life. Des dizaines d’orchestres, d’artistes et de labels participent à ce mouvement sans précédent. Par rapport à sa population, le Bénin est le pays d’Afrique le plus prolifique en terme de production discographique, notamment au cours d’une effervescence extraordinaire durant les années 1970. A la manière de ce qu’il se passe alors en Guinée, en Côte d’Ivoire ou au Mali, chaque grande ville ou préfecture possède au moins un orchestre moderne, que ce soit à Cotonou, Porto-Novo, Parakou, Ouidah, Natitingou, Abomey ou Bohicon. Des formations comme les Black Santiagos, le National Jazz du Dahomey, le Super Star de Ouidah, le Picoby Band et le Renova Band d’Abomey ou encore les Black Dragons de Porto Novo se font une réputation au niveau national. Au milieu des années 1960, la chanteuse Sophie Edia devient la première voix féminine à diffuser la musique béninoise en dehors des frontières du pays, à commencer par le Nigeria. En 1975, l’Unesco promeut l’Année Internationale de la Femme, un événement destiné à faire prendre conscience du rôle des femmes dans de nombreux pays, là où leur rôle est trop souvent minimisé ou bafoué. Cette initiative a un impact considérable sur le continent africain. Que ce soit au Mali avec Fanta Damba, en Côte d’Ivoire avec Mamadou Doumbia, au Cameroun avec Anne-Marie Nzie, au Congo Brazzaville avec Les Bantous de la Capitale ou au Burkina Faso avec Echo del Africa, tous rendent hommage à cette initiative. Partout en Afrique francophone, les consciences s’éveillent quand aux droits des femmes. En 1976, le poète camerounais Francis Bebey publie l’éloquent La Condition Masculine. Sous ses airs humoristiques, cette merveille interpelle elle aussi les consciences, sans pour autant sombrer dans une moralisation outrancière. "Tu ne connais pas Sizana Sizana, c'est ma femme C'est ma femme puisque nous sommes mariés depuis plus de dix-sept ans maintenant Elle était très gentille auparavant Je lui disais "Sizana, donne-moi de l'eau" Et elle m'apportait de l'eau à boire De l'eau claire, hein, très bonne! Je luis disais, "Sizana, fais-ceci" "Fais-cela" et elle obéissait Et moi j'étais content, je regardais tout ça avec bonheur Ah, je te dis que Sizana, Sizana, elle était une très bonne épouse auparavant Seulement, depuis quelques jours, les gens, là Ils ont apporté ici la condition féminine Il paraît que là-bas, chez eux, ils ont installé une femme dans un bureau Pour qu'elle donne des ordres aux hommes Aïe, tu m'entends des choses pareilles?" Francis Bebey "La condition masculine" Son compatriote Ali Baba creuse le même sillon avec La Condition Féminine, on ne tape pas la femme. En Côte d’Ivoire, Sidiki Bakaba déclame un poème de Léopold Sédar Senghor sur l’éloquent 45 tours Femme noire, mis en musique en mode spiritual jazz. Au Bénin, en 1977, le batteur Danialou Sagbohan enregistre l’éloquent Viva, femme africaine, un single fondateur pour la prise de conscience féminine dans ce pays. L’enthousiasme de ces années d’émancipation retombe toutefois au cours des années 1980, avec son lot d’unions imposées, de grossesses précoces, de violences diverses et d’excisions, notamment en Afrique sahélienne. En 1989, Oumou Sangaré, une jeune chanteuse malienne originaire du Wassoulou, enregistre l’historique Moussoulou (« Femmes »), aux sonorités claires et acoustiques. Puissant et percutant, son chant influence de nombreuses chanteuses du continent au cours des décennies suivantes. Ce premier opus offre un instantané saisissant de la condition des femmes d’Afrique de l’Ouest à la fin des années 1980. A ses débuts, elle chante dans les rues de Bamako, pour gagner de quoi manger. Oumou Sangaré modernise radicalement la tradition des cantatrices locales. Elle séduit immédiatement grâce à sa voix féline, mais aussi en raison de ses textes qui dénoncent la polygamie, les mariages forcés ou l’excision, prônant une sensualité, une fierté et une féminité sans ambages. Son succès est immédiat, avec des millions de cassettes vendues dans tous les marchés d’Afrique de l’Ouest. Oumou Sangaré accède au statut de superstar de la pop africaine. Femme malienne inscrite dans son époque, elle incarne le triomphe de l’amour et des émotions féminines en toutes circonstances. Si la musique sur laquelle elle chante est séduisante, audacieuse et pleine de vie, ses paroles imposent une nouvelle manière de voir. Celles-ci sont plus importantes que la musique. Elle est inspirée par les évènements sociaux et par son environnement immédiat. Femme libre, elle dit ce qu’elle veut et ce qu’elle pense. Sa musique, apolitique mais féministe, a un large impact. Son message à propos de la femme africaine rencontre un très large écho, sur le continent comme dans le reste du monde. Au cours des années 1990, la béninoise Angélique Kidjo s’impose également comme l’une des grandes voix féminines africaines. Elle porte haut l’héritage musical béninois. Née en 1960 à Ouidah, le berceau du vaudouisme, elle est bercée enfant par le théâtre et les sonorités afro-américaines. Encore adolescente, elle se fait un nom dans tout le pays grâce à ses apparitions radiophoniques. A ses débuts, elle est accompagnée par le Poly Rythmo de Cotonou, formé en 1969. Cet orchestre est le plus légendaire du pays, au gré d’une discographie pléthorique, de centaines de singles, d’albums et d’innombrables tournées partout dans le monde. En 1980, Angélique Kidjo enregistre son premier album Pretty à Paris sous la houlette du Camerounais Ekambi Brillant. Son succès en Afrique de l’Ouest est immédiat. Elle s’installe en France en 1983, en pleine explosion des musiques venues d’Afrique. Elle participe à divers groupes, avant de se lancer en solo et de s’imposer comme la grande voix féminine du Bénin. Quarante ans plus tard, ses héritières et compatriotes sont en passe de rayonner au grand jour. Dernière grande ville étape sur la route nationale qui sillonne le Nord Ouest du Bénin, la paisible Natitingou s’étale en longueur de part et d’autre d’un ruban d’asphalte. Après une quinzaine d’heures de route depuis la capitale économique Cotonou, cette ville offre une étape appréciable avant de poursuivre vers le Burkina Faso, le Togo ou l’immense réserve de la Pendjari, via Tanguiéta, là où commencent les vastes plaines sahéliennes et se réfugient les derniers grands animaux sauvages ayant échappé à la folie des hommes. Ville de croisement dans cette région située au carrefour de quatre pays, Natitingou contrôle l’accès de la région des collines de l’Atakora, qui ceignent la ville. Enclavée, la commune de Natitingou est largement isolée du reste du Bénin, tributaire du ravitaillement routier, des coupures d’électricité et des éléments naturels, parfois hostiles. Longtemps rétive à toute forme de domination, cette région a pour héros Kaba. Au début de la première guerre mondiale, il refusa la conscription militaire obligatoire et mena une guérilla farouche contre l’oppression coloniale. Cette guerre perdue se termina dans un bain de sang en 1917. A la sortie de la ville, le musée Kaba raconte cette résistance du peuple somba, notamment par son évocation de sa culture, de ses cérémonies, du travail du fer ou encore des cases circulaires, au toit conique, souvent surélevées et fortifiées, appelées tatas que l’on retrouve dans une bonne partie du Sahel. Kaba donna son nom à l’un des premiers orchestres de Natitingou, Kaba Diya, actif entre 1979 et 1983. Celui-ci publia un unique album de musiques modernes en 1980, représentatif de la culture de cette région, à commencer par sa pochette. Si Kaba Diya a eu l’occasion de publier un 33 tours, d’autres formations locales ont également marqué les esprits. Formation historique créée dès 1960, l’orchestre Bopeci a publié deux 45 tours. En revanche, Nati Fiesta, le Tchankpa Jazz ou L’Echo de l’Atakora n’ont a priori jamais publié leurs morceaux au format vinyle. Plus récemment, depuis le milieu des années 1990, Gay Stone, Cool Star, Ata Echo, les 3 Couleurs, le groupe Tchingas, Zénith Temple, Excelsior mais aussi depuis 2017 la formation FMG animent les nuits de Natitingou et de l’Atakora. Culturellement et musicalement, cette région du Nord-Ouest du Bénin est plus proche de l’aire d’influence sahélienne que de celle du Sud du pays, du sato, du vaudou et du folklore modernisé développé par des formations comme l’orchestre Black Santiagos qui donna ainsi naissance à l’afrobeat dès le milieu des années 1960, avant d’être repris et développé par Fela Kuti. C’est dans cette région de contraste, de paysages à la fois verts et rocailleux qu’ont grandies les sept vedettes juvéniles du Star Feminine Band. Souvent déscolarisées et promises à vendre des arachides, des bananes, du gari ou du tchoucoutou, une boisson locale à base de mil au bord du goudron, la plupart des jeunes filles de la région n’ont guère d’avenir. Les mariages forcés et les grossesses précoces sont légion. Conscient de cette précarité, le musicien André Baleguemon décide de former un groupe exclusivement féminin ancré dans les préoccupations de son époque. Il laisse la part belle à la guitare, à la batterie et au clavier, instruments admirés depuis son enfance, symboles de modernité dans cette région reculée. Son constat est simple : « Dans le Nord, les filles n’évoluent pas beaucoup et les femmes sont mises de côté. J’ai simplement voulu montrer la valeur de la femme dans les sociétés du Nord Bénin en formant un orchestre féminin ». Originaire de Tchaourou, une vaste commune située au centre Est du Bénin, André Balaguemon se passionne très jeune pour la musique. Il intègre l’orchestre Sam 11 de Parakou, au Nord Est du pays, au cours des années 1990, où il est successivement trompettiste puis guitariste. En 1999, il descend à Cotonou avant de se fixer dans le Nord-Ouest du pays, afin de renouer avec ses racines et ses passions musicales. Le 25 juillet 2016, avec le soutien de la municipalité de Natitingou, André lance un communiqué sur les ondes de Nanto FM afin de former des filles bénévolement à la musique. Quelques jours plus tard, des dizaines d’aspirantes musiciennes se présentent à la Maison des Jeunes. « Les filles qui sont venues ne connaissaient rien à la musique. Les sept sélectionnées sont de jeunes filles d’ethnie waama et nabo. Venues des villages alentour, certaines n’avaient même jamais vu ce genre d’instruments ». Depuis l’époque des indépendances, posséder ses propres instruments a toujours été l’une des conditions premières pour tout orchestre africain qui se respecte. Avec les instruments achetés par ses soins, batterie, deux guitares et des claviers, ajoutés à quelques percussions, André effectue ses premiers essais musicaux avec ses nouvelles recrues, une poignée de jeunes filles parmi les plus motivées. Rapidement, les filles se passionnent pour leurs nouvelles activités musicales, apprenant la batterie, la guitare, les harmonies vocales, le piano. Leurs progrès sont stupéfiants. Un intense travail de formation musicale se met en place, à commencer par des ateliers de batterie, l’instrument fétiche de la formation. Angélique et Urrice sont à la batterie et au chant, secondées par Marguerite, la troisième batteuse. Sandrine est aux claviers, tout comme Grace, qui œuvre également au chant. Julienne est à la basse et Anne à la guitare. Comme influence fondatrice de leur démarche, André cite volontiers Angélique Kidjo, « notre inspiration principale. C’est une femme que l’on ne peut pas ignorer. Miriam Makeba est aussi une source de fierté, comme Sagbohan Danialou, Stanislas Tohon. Kaba Diya, le grand orchestre régional nous a aussi beaucoup inspiré ». La pugnacité d’André est l’un des éléments clé de cette réussite humaine et artistique. Les filles ont déjà donné des dizaines de concerts dans la région, forgeant et étoffant un répertoire déjà solide, tout en séduisant un public local toujours plus nombreux. Outre les progrès musicaux, il s’implique personnellement auprès de chaque famille pour leur faire comprendre l’importance de son projet, à la fois sur le plan musical et humain, notamment sur le fait que chaque fille reste scolarisée et ne soit pas entrainée dans un mariage forcé. Dans l’histoire des musiques populaires africaines, peu nombreuses sont les formations féminines. Si les Amazones de Guinée, la Famille Bassavé et les Colombes de la Révolution au Burkina, les Sœurs Comoë en Côte d’Ivoire ou les Lijadu Sisters au Nigeria viennent notamment à l’esprit, Star Feminine Band n’a certainement pas d’équivalent au Bénin. La fraicheur, l’insouciance et la liberté, mais surtout le talent de ces jeunes filles est sans appel. A la fin de l’année 2018, la rencontre avec le jeune ingénieur français Jérémie Verdier accélère le cours des choses. En mission dans la région, il fait appel à ses amis espagnols Juan Toran et Juan Serra. Ceux-ci débarquent avec leur matériel d’enregistrement afin de graver les premiers morceaux de la jeune formation dans l’annexe du Musée local. Au hasard des rencontres et mû par un instinct sûr, Jean-Baptiste Guillot entend ces bandes. Il décide alors de partir à leur rencontre à la fin de l’année 2019. Ce voyage mémorable de quelques jours scelle le destin de l’album que vous tenez entre vos mains. Aujourd’hui âgées de neuf à quinze ans, les sept jeunes filles du Star Feminine Band continuent d’aller à l’école. Dans une annexe du Musée Départemental de Natitingou, André a installé le local de répétition de la formation. Plusieurs fois par semaine, les sept jeunes filles se retrouvent dans cet endroit, habitées par les plus nobles aspirations, celles de chanter leur culture, leur condition féminine et leur possible émancipation. Leurs répétitions ont lieu trois fois par semaine, de 16h à 19h. En période de vacances scolaires, elles répètent tous les jours du lundi au vendredi de 9h à 17h. En 2020, dans nombre de zones rurales du continent africain, mais aussi parfois dans les grandes métropoles, la situation des femmes n’a guère évolué depuis les années 1960, l’époque des indépendances où l’on pensait que tout aller changer à travers un continent en quête de modernité, de culture et d’émancipation. S’il a fait des émules en Afrique, le mouvement Me Too n’a guère touché les parties les plus reculées du continent. Prenant son essor, le Star Feminine Band donne plusieurs concerts à Natitingou mais aussi dans les villages alentour. A chaque fois qu’elles jouent en public, elles rassemblent un public local toujours plus nombreux et curieux quand à la démarche de cette formation iconoclaste. Les femmes viennent en masse, mais plus généralement les parents avec leurs enfants, mais aussi beaucoup de personnes âgées, dans une région où les activités culturelles se limitent souvent aux cérémonies agraires ou funéraires. André Baleguemon et ses talentueuses protégées adaptent des chansons d’inspiration traditionnelle, dans une veine de folklore modernisé. « Nous jouons les danses de rythme waama, nous voulons les mettre à l’honneur. Nous avons composé des chansons en français, en waama et ditamari, deux ethnies méconnues du Nord. Nous chantons aussi des morceaux en langue bariba, ainsi qu’en langue fon, langue majoritaire au Bénin, dans le nouveau répertoire, afin de se faire comprendre du plus grand nombre ». Peba est chanté en waama. Il y est dit que les filles vont à l’école pour être elles mêmes. Chantées en français les paroles de La musique et de Femme africaine sont éloquentes quant aux messages énoncés. Timtilu est chantée en ditamari. Les filles conseillent ici de ne pas délaisser leur culture, mais plutôt de la mettre à l’honneur. Chant d’émancipation en langue peule, Rew Be Me Light, est une ode à la femme, un encouragement pour réussir sa propre carrière et réussir en tant que femme. Fédérateur, Iseo est chanté en bariba. « Hommes et femmes, levons nous, du sud, du centre, du nord, unissons-nous et soyons un pour que le pays évolue ». Il s’agit ici de rassembler les régions et la diversité des cultures du Bénin. Louange à Dieu en peul, Montealla est d’inspiration mandingue dans son interprétation. Chanté en bariba, Idesouse indique que les filles doivent être scolarisées et aller au bout de leurs études pour défendre les valeurs de la femme. Elles doivent se battre d’autant plus afin de gagner cette reconnaissance. Au gré de chacun ces morceaux, chacune des filles de Star Feminine Band apporte sa propre inspiration. André compose tous leurs morceaux. Comme il le concède : « Elles amènent leurs idées. Le rêve de ces filles c’est de devenir des stars au niveau international. Elles doivent montrer la valeur de la femme dans le monde entier. Parler de l’Afrique, accomplir de grandes missions autour des valeurs de la femme. Elles parlent de l’excision, de la maltraitance et des violences faites aux filles. Nous voulons inscrire ces sujets dans le débat politique au Bénin, puis ailleurs en Afrique si cela nous est un jour possible ». Avec beaucoup d’aplomb, un œcuménisme et un charisme indéniables, Star Feminine Band s’impose aujourd’hui comme l’une des fiertés de la région de l’Atakora. Le groupe commence même à susciter des vocations, tout en semant les graines pour la prochaine génération de jeunes filles provinciales, mues par une volonté de fer, forgée du même minerai que les armes de Kaba, héros oublié de l’Atakora. Véritables héroïnes du quotidien, les sept filles du Star Feminine Band incarne le futur et la relève d’une génération en quête de reconnaissance. « Dans les années 1960, Dieu était une jeune fille noire qui chantait » avait coutume de dire le duo de compositeur new-yorkais Carole King et Gerry Coffin. Soixante années plus tard, dans une des provinces oubliées du continent africain, cet adage revêt toute sa valeur. Florent Mazzoleni ////////////////////ENGLISH/////////////////////////////// "Oh woman, African woman Oh woman, Beninese woman Black woman, get up, don't sleep Oh black woman, get up don't sleep You can become president of the republic Lead You can become the country’s Prime Minister Get up, something has to be done African woman, be independent The country needs us, let's go to school Africa needs you, you have to work The world needs us, stand up, let's stand up African woman, be independent" Star Feminine Band "Femme Africaine" Without warning, a group of young girls from a remote region of Benin is shaking up the world of garage rock with breathtaking freshness, ingenuity and energy, playing spot-on, loud and clear. During the first half of the twentieth century, the division of the majority of Africa by European powers introduced a forced modernity throughout most of the continent. In cities and ports, the continent buzzed with new energy as electricity began its timid appearance. Thanks to booming maritime transport, the 78 rpm records brought in by Latin American sailors, in particular Cubans, but also by European soldiers or settlers, had a durable influence on the new musical interests along the African coasts. Gradually, the reinterpretation of Cuban, but also Caribbean, jazz or rhythm’n’ blues music began. For the most part originally from Africa, this music from the Americas acted as a natural truth on the continent. Some orchestras thus decided to "re-Africanize" this Afro-Cuban and black American music heard in ports, public places or broadcasted on the radio. Bars and dance halls, as well as youth associations also played an important role in the dissemination and development of this music. In most African cities, many orchestras were born during the 1950s and 1960s. They became symbols of modernity, like electricity, cars and cinema. The euphoria of the years following independence was therefore set to music by these orchestras. These were partly influenced by Ghanaian dance formations that toured through all the major cities of the Gulf of Benin, from Nigeria to Liberia. The cultural exchanges were fertile. In the early 1960s, the rich local traditions of Benin, starting with trance and voodoo ceremonial music, began to merge with Afro-Cuban, Congolese rumba and high-life. Dozens of orchestras, artists and labels participated in this unprecedented movement. Unlike its population count, Benin is the most prolific African country in terms of record production, especially during the extraordinary exhilaration of the 1970s. In Guinea, Ivory Coast or Mali, each major city or prefecture had at least one modern orchestra, whether in Cotonou, Porto-Novo, Parakou, Ouidah, Natitingou, Abomey or Bohicon. Bands such as the Black Santiagos, the National Jazz of Dahomey, the Super Star of Ouidah, the Picoby Band, the Renova Band of Abomey and the Black Dragons of Porto Novo gained in popularity at the national level. In the mid-1960s, singer Sophie Edia became the first female singer to distribute Beninese music outside of the country's borders, starting with Nigeria. In 1975, Unesco promoted the International Women’s Year, an event designed to raise awareness of the role of women in many countries, where their role is too often downplayed or flouted. This initiative had a considerable impact on the African continent. Whether in Mali with Fanta Damba, in Côte d'Ivoire with Mamadou Doumbia, in Cameroon with Anne-Marie Nzie, in Congo Brazzaville with Les Bantous de la Capitale or in Burkina Faso with Echo del Africa, they all paid tribute to this initiative. All over French-speaking Africa, people were awakening to women's rights. In 1976, the Cameroonian poet Francis Bebey published the eloquent La Condition Masculine. Under its humorous airs, this gem challenged morals with lightness and tact. "You don't know Sizana Sizana is my wife She's my wife since we've been married for over seventeen years now She used to be very nice I would say to her "Sizana, give me water" And she would bring me water to drink Clear water, huh, very good! I would say, "Sizana, do this" "Do that" and she would obey And I was happy Ah, I tell you that Sizana, Sizana, she used to be a very good wife But, these past few days, these people They brought the female condition here Apparently over there, where they live, they put a woman in an office So that she can give orders to men Ouch, have you ever heard such a thing? " His fellow countryman Ali Baba ploughed the same furrow with La Condition Féminine, on ne tape pas la femme (The Feminine Condition, you don't hit a woman). In Ivory Coast, Sidiki Bakaba recited a poem by Léopold Sédar Senghor on the eloquent Femme noir (Black Woman) 45 rpm, set to spiritual jazz. In Benin, in 1977, drummer Danialou Sagbohan recorded the eloquent Viva, femme africaine (Viva, African woman), a founding song for women’s rights in his country. However, the enthusiasm of these years of emancipation dropped during the 1980s, with its share of forced unions, early pregnancies, various forms of violence and female genital mutilation, particularly in Sahelian Africa. In 1989, Oumou Sangaré, a young Malian singer from Wassoulou, recorded the historic Moussoulou ("Women"), with clear and acoustic tones. Powerful and impactful, her song influenced many female singers on the continent during the following decades. This first opus offered a striking snapshot of the condition of West African women in the late 1980s. When she started out, she sang in the streets of Bamako in order to earn enough to eat. Oumou Sangaré radically modernized the tradition of local singers. She immediately seduces the listener with her feline voice, but also with her lyrics which denounce polygamy, forced marriages or female genital mutilation, advocating sensuality, pride and unambiguous femininity. Her success was immediate, with millions of cassettes sold throughout all West African markets. Oumou Sangaré reached the status of African popstar. A Malian woman of her time, she embodied the triumph of love and female emotions in all circumstances. If the music on which she sings is attractive, daring and full of life, her words impose a new way of seeing things. These words weighed more than the music. Inspired by social events and her immediate environment, a free woman, she spoke her truth. Her music, apolitical but feminist, had a wide impact. Her message about African women was widely heard, both on the continent and throughout the rest of the world. During the 1990s, the Beninese Angélique Kidjo also established herself as one of the great African female singers. She proudly promoted Beninese musical heritage. Born in 1960 in Ouidah, the cradle of voodooism, she was raised in the world of theater and African-American sounds. As a teenager, she made a name for herself throughout the country thanks to her radio appearances. At the start of her career, she was accompanied by the Poly Rythmo of Cotonou, formed in 1969. The most legendary orchestra of the country, according to an enormous discography that includes hundreds of singles, albums as well as countless tours around the world. In 1980, Angélique Kidjo recorded her first album Pretty in Paris under the leadership of the Cameroonian Ekambi Brillant. Its success in West Africa was immediate. She moved to France in 1983 when music from Africa was all the hype. She joined different bands, before going solo and establishing herself as the greatest female voice of Benin. Forty years later, her successors and compatriots are about to shine bright. The last big city on the main road that criss-crosses northwestern Benin, peaceful Natitingou stretches out on either side of a strip of asphalt. After a fifteen hour drive from the business capital of Cotonou, this city offers a valuable stopover before heading to Burkina Faso, Togo or the huge Pendjari reserve, via Tanguiéta, where the vast Sahelian plains begin and where the last great wild animals to have escaped the madness of mankind take refuge. One of the region’s main crossover cities located at the crossroads of four countries, Natitingou controls the access to the Atakora hills region, which surrounds the city. Landlocked, the city of Natitingou is largely isolated from the rest of Benin, dependent on road deliveries and subject to power cuts and sometimes hostile natural elements. Steadily reluctant to any form of domination, this region’s hero is named Kaba. At the start of the First World War, he refused compulsory military service and led a fierce guerrilla war against colonial oppression. This lost war ended in a bloodbath in 1917. Upon leaving the city, the Kaba museum tells the story of the resistance of the Somba people, in particular through its evocation of its culture, its ceremonies, its iron work and even its circular huts with conical roofs, often raised and fortified, called tatas that are found in a good part of the Sahel. Kaba gave his name to one of Natitingou's first orchestras, Kaba Diya. Active between 1979 and 1983, it released a unique record of modern music in 1980, representative of the culture of its region, starting with the artwork. If Kaba Diya had the opportunity of releasing an LP, so did other local bands. A historical group formed in 1960, the Bopeci orchestra, released two 45 rpm records. On the other hand, Nati Fiesta, Tchankpa Jazz or L’Echo de l'Atakora never had a chance to release their songs on vinyl. More recently, since the mid 90s, Gay Stone, Cool Star, Ata Echo, Les 3 Couleurs, the Tchingas band, Zénith Temple, Excelsior and also since 2017 the FMG formation have been livening up the nights of Natitingou and Atakora. Culturally and musically, this region of North-West Benin is more influenced by the Sahel than by the South of the country, by sato, voodoo and modernized folklore developed by groups like the Black Santiagos orchestra which gave birth to Afrobeat in the mid-1960s, before being adopted and developed by Fela Kuti. It is in this region full of contrast, of both green and rocky landscapes, that the seven young stars of the Star Feminine Band grew up. Often taken out of school and sent to sell peanuts, bananas, gari or tchoucoutou, a local millet drink on the side of the road, most young girls in the region have little future to look forward to. Forced marriages and early pregnancies in the majority of cases. Aware of this insecurity, a musician named André Baleguemon decided to form an exclusively female band rooted in the concerns of its time. He puts the spotlight on the guitar, drums and keyboard, instruments he has admired since his childhood, symbols of modernity in this remote region. His observation is simple: "In the North, girls have no room to advance and women are put aside. I simply wanted to show the importance of women in the societies of North Benin by forming a female orchestra ". Originally from Tchaourou, a vast commune located in central eastern Benin, André Balaguemon developed a passion for music at a very young age. During the 1990s, he joined the Sam 11 orchestra in Parakou, in the northeastern part of the country, where he successively played trumpet and guitar. In 1999, he spent some time in Cotonou before settling in the northwest, in order to reconnect with his roots and musical passions. On July 25th, 2016, with the support of the city of Natitingou, André launched a press release on Nanto FM offering to help train girls in music for free. A few days later, dozens of aspiring musicians showed up at the Youth Center. “The girls who came didn't know anything about music. We selected seven girls of the Waama and Nabo ethnic groups from the surrounding villages, some had never even seen these types of instruments before. " Since the independence era, having your own instruments has always been the prerequisite of any self-respected African orchestra. With drums, two guitars, keyboards and some added percussion purchased by André, the first musical tests began with his new recruits, a handful of young girls among the most motivated. The girls quickly became passionate about their new musical activities, learning how to play drums, guitar, piano and sing vocal harmonies. Their progress was astounding. An intense work of musical training took place, starting with drum workshops, their favorite instrument. Angelique and Urrice on drums and vocals, assisted by Marguerite, the third drummer. Sandrine is on keyboards, as is Grace, who also sings vocals. Julienne is on bass and Anne on guitar. As the founding influence of their approach, André readily quotes Angélique Kidjo, “our main inspiration. She is a woman you cannot ignore. Miriam Makeba is also a source of pride, as is Sagbohan Danialou, Stanislas Tohon. Kaba Diya, the great regional orchestra, also inspired us a lot. ” André's determination is one of the key elements of this human and artistic success. The girls have already performed dozens of concerts in the region, forging and expanding an already solid repertoire, while attracting an ever-increasing local audience. In addition to musical progress, he has been personally involved with each family, showing them the importance of his project, both musically and humanly and in particular the fact that each girl must remain in school and not be forced into marriage. There are very few female bands in the history of popular African music. If the Amazones de Guinée, la Famille Bassavé and les Colombes de la Révolution in Burkina, the Sœurs Comoë in Ivory Coast or the Lijadu Sisters in Nigeria notably come to mind, Star Feminine Band has no equivalent in Benin. The originality, carefree attitude, freedom, and above all the talent of these young girls is undeniable. At the end of 2018, their encounter with the young French sound engineer Jérémie Verdier accelerated the course of things. On a mission in the region, he called on his Spanish friends Juan Toran and Juan Serra who showed up with their recording equipment in order to record the band’s first songs in the annex of the local museum. Random encounters and fate led Jean-Baptiste Guillot to hear the tapes. He decided to go meet them at the end of 2019. This short but memorable journey sealed the fate of the record you are now holding in your hands. Now aged nine to fifteen, the seven girls of the Star Feminine Band continue to go to school. André installed a rehearsal room in an annex of the Departmental Museum of Natitingou. Several times a week, the seven young girls get together, inhabited by the noblest aspirations, those of singing their culture, their feminine condition and their possible emancipation. They rehearse three times a week, from 4 to 7 p.m. During school holidays, they rehearse daily from Monday to Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. It’s 2020 but the situation of women in many rural areas of the African continent and also sometimes in large metropolises, has hardly changed since the 1960s, the era of independence when it was believed that everything would change in this continent that was searching for modernity, culture and emancipation. Although there were some followers of the Me Too movement in Africa, it hardly touched the most remote parts of the continent. The Star Feminine Band is taking off. Performing several concerts in Natitingou but also in the surrounding villages. Each time they play in public, they bring together an ever-increasing and curious local audience when it comes to this one of a kind training. Women come en masse, as well as parents with their children, but also many elderly people, in a region where cultural activities are often limited to agricultural or funeral ceremonies. André Baleguemon and his talented protégés adapt songs of traditional inspiration, in a vein of modernized folklore. “We play waama rhythm dances, we want to honor them. We compose songs in French, waama and ditamari, two unknown ethnic groups from the North. We also sing songs in the Bariba language, as well as the Fon language, the main language in Benin, in the new repertoire, in order to be understood by as many people as possible.” Peba is sung in waama. It’s about girls going to school in order to be themselves. Sung in French, the lyrics of La Musique and Femme africaine speak for themselves. Timtilu is sung in ditamari. In this song, the girls give the advice to not abandon your culture, but rather to honor it. A song of emancipation in the peul language, Rew Be Me Light, is an ode to women, an encouragement to succeed in your own career and succeed as a woman. A unifying song, Iseo is sung in bariba. “Men and women, let us rise, from the south, from the center, from the north, let us unite and be one so that the country can evolve”. This song is about bringing together the regions and the diversity of cultures in Benin. Praise be to God in peul, Montealla’s interpretation was inspired by mandingo. Sung in bariba, Idesouse indicates that girls must go to school until the end of their studies in order to defend the values of women. They have to fight all the more in order to gain this recognition. Through all of these songs, each of the Star Feminine Band members brings their own inspiration. André composes all their songs. He admits: “They bring their ideas. The dream of these girls is to become international stars. They must show the importance of women throughout the world. Speak of Africa, accomplish great missions around the values of women. They talk about female genital mutilation, abuse and violence against girls. We want to include these subjects in the political debate in Benin, then elsewhere in Africa if this is ever possible ”. With much confidence, an undeniable ecumenism and charisma, Star Feminine Band is one of the prides of the Atakora region. The band is even starting to instigate vocations, while sowing the seeds for the next generation of provincial girls, driven by an iron will, forged of the same mineral as the weapons of Kaba, forgotten hero of the Atakora. True heroines of everyday life, the seven girls of the Star Feminine Band embody the future and the next generation in search of recognition. “In the 1960s, God was a black girl who sang” used to say New York composer duo Carole King and Gerry Goffin. Sixty years later, in one of the forgotten provinces of the African continent, this adage takes on its full value. Florent Mazzoleni

The music of Darren Cunningham, the British electronic musician known as Actress, is notoriously difficult to categorize. Over the past 15 years, he has evaded the confines of more familiar dance music with avant-garde, abstract compositions that gaze inward. Although he references house, techno, dubstep, and R&B, he deconstructs, twists, and stretches them into practically unrecognizable forms. But make no mistake, his records are still intensely emotional—vivid soundscapes so full of depth and light that they can feel overwhelming. And *Karma & Desire*, his seventh LP, feels, in many ways, like mourning. Guided by meandering piano arpeggios and hushed vocals about heaven and prayer, it evokes funereal images of death and rebirth (“I’m thinking/Sinking/Down/In Heaven,” Zsela sings on “Angels Pharmacy”). A glitchy, fuzzy texture permeates the album, as if the tracks had been passed through an old-fashioned Instagram filter, and it builds a general sense of uneasiness. Actual beats are scarce, but those that do appear feel almost meditative (“Leaves Against the Sky,” “XRAY”), as if to provide relief from the amorphous expanse. It’s easy to see the metaphor for getting lost in dark corners of your own mind, and the solace that you feel when reality returns.

After recent mixtape “88”, Actress reveals new album "Karma & Desire". ‘Walking Flames’ featuring Sampha is out now. “Karma & Desire” includes guest collaborations from Sampha, Zsela and Aura T-09 and more. It’s “a romantic tragedy set between the heavens and the underworld” says Actress (Darren J. Cunningham) “the same sort of things that I like to talk about – love, death, technology, the questioning of one's being”. The presence of human voices take the questing artist into new territory. ‘Walking Flames’: “These are like graphics that I’ve never seen / My face on another human being / The highest resolution / Don't breathe the birth of a new day.” Flute-like melodies contributed by Canadian organist and instrument builder Kara-Lis Coverdale.