In 2018, Dayglow (aka Sloan Struble) completed his debut album *Fuzzybrain* during his senior year of high school in Fort Worth, Texas. Recorded with minimal resources, it remained in relative obscurity for a short while—a sublime slice of bright-eyed bedroom pop that begged to be discovered. Shortly after, the singer-songwriter went on to study advertising at the University of Texas with no interest in pursuing mainstream stardom. That is, until the music video for “Can I Call You Tonight?” became a runaway crossover hit—which Struble shot on a shoestring budget using green-screen effects and has since netted hundreds of millions of YouTube streams. Naturally, it was a lot for Struble to take in. Reflecting on his rise, *Harmony House* has him dealing with the crazy changes that happened so quickly in his life. “\'Cause if you wanna keep on growing, you’ve gotta leave some things behind,” he muses on the mellow “Woah Man,” reassuring himself that letting go is okay as he calmly strums his guitar. But Struble approaches his music with a glass-half-full optimism, and as such, the album’s billowing indie pop has an airy, carefree vibe that could make even the toughest cynic smile. Whether he’s whistling his way through slick yacht rock (“Medicine”) or pivoting into Wild Nothing-recalling dream pop (“Balcony”), Struble makes even the most lovesick sentiments go down easy. But it’s his taste for ’80s soft-rock that resonates the most throughout, like on “December,” on which he contemplates wanting a fresh start along with a smooth sax solo that would make legendary session musician Phil Kenzie proud.

The identity of Toronto fusionists BADBADNOTGOOD has largely been shaped by the company they keep. This is, after all, a group with the stylistic fluidity and instrumental dexterity to bring Ghostface Killah’s ’70s-funk fantasias to life, turn up the heat on Charlotte Day Wilson’s slow-burning R&B ballads, and allow Future Islands’ Samuel T. Herring to channel a past life as a cabaret soul singer. But in contrast to 2016’s star-studded *IV*, BADBADNOTGOOD’s *Talk Memory* is conspicuously lacking in vocal features. Rather, the group’s first album in five years is an all-instrumental affair that puts the focus squarely on their most crucial quality: the ever-present tension between compositional sophistication and freaked-out improvisation. That said, *Talk Memory* still boasts the sort of enviable guest list only BADBADNOTGOOD could assemble. They built a dream team of instrumentalists—including Brazilian composer Arthur Verocai, ambient icon Laraaji, electro-psych voyager Floating Points, and Kendrick Lamar saxophonist Terrace Martin—to infuse their grooves with a cinematic grandeur (and also help fill the space vacated by keyboardist Matty Taveres, who left the band in 2019). But while the album’s lustrous string arrangements and psychedelic harp flourishes speak to the group’s ever-expanding musical vision, *Talk Memory* is also fueled by a primal energy that’s more conducive to head-banging than chin-stroking—when bassist Chester Hansen activates his fuzz pedal and starts shredding on the colossal nine-minute opener “Signal From the Noise,” BBNG practically resembles a free-jazz Death From Above 1979. “We come from a background of listening to a lot of rock music when we were younger,” Hansen tells Apple Music. “When we started to play our instruments, \[saxophonist\] Leland \[Whitty\] was learning Iron Maiden solos, and \[drummer\] Alex \[Sowinski\] was playing a bunch of Rush and Led Zeppelin, so it\'s nice to be able to incorporate some of those elements on this record.” Here, Hansen talks us through his memories of *Talk Memory*, track by track. **“Signal From the Noise”** “In the years of playing shows \[after *IV*\], we did a lot of improv stuff, and the intro to this song was a bass interlude we did on stage—I would essentially play stuff that sounded like this. And then when we were writing stuff for this album, we wanted to build it into a full song. So we added the arrangements and the bass solo, and our engineer Nic \[Jodoin\] made a tape loop that he faded in over the end. We also had some additional production from Floating Points at the very end to make it even more psychedelic.” **“Unfolding (Momentum 73)”** “I think the idea behind this title was that the human body is 73% water. And the \'unfolding\' part refers to the fact that the main sax part sounds like it\'s actually unfolding. Leland had the first arpeggio that you hear on sax, and we wanted to build a song around that. We finished the song right before the pandemic, and then, over the last year, we sent it to Laraaji, who\'s a legendary ambient artist. He has vocal songs but he also plays zither and other instruments, so we thought it\'d be a cool twist to get him to play zither on this.” **“City of Mirrors”** “A lot of our favorite records have incredible string arrangements on them, but logistically it\'s sometimes difficult to work them in. We\'ve been really lucky in the past because Leland plays violin and viola, so previously, we\'d just record him a hundred times stacked on top of each other to make an orchestral sound. But for this album, we were able to reach out to Arthur Verocai, who\'s a massive influence on us and a true legend. So we sent him every song and then he sent back all the string arrangements that you hear, which really took everything to the next level.” **“Beside April”** “Mahavishnu Orchestra was a big influence on this song. In the past, we haven\'t really had a lot of songs with riffs like this, so it\'s cool to be able to include some stuff that has a lot of riffs. It made sense for us to release this as a single before the album came out, because it has a pretty epic energy. Karriem Riggins played on this with us. He came by when we were running through it in the studio, and liked how it sounded. He\'s obviously an amazing drummer, but for this one, he was like, \'Just give me a snare drum!\' So Alex played the drum kit, and then Karriem had a snare drum with brushes and we just set up a mic for him. He was making sounds that I had never heard from just a single drum before. It was really amazing.” **“Love Proceeding”** “I was out of town, and Leland and Alex got together and jammed an early version of this. One interesting thing about this album is that it\'s the first thing we\'ve done with just the three of us, because Matty—our keyboard player and founding member of the band—went his own way a couple years ago, so this is us trying to figure out what we\'re going to do, and if we can cover all the parts. For this one, Leland played guitar for the first half and then ran over to the sax to play the solo, and we did it like all in one take, which was pretty fun.” **“Timid, Intimidating”** “Another difference about this album in general is that we would bring in stuff that we had written individually and take it to the next level with the rest of the group, instead of being there for every part of the writing process all together. I was trying to write songs that had crazy riffs in them, basically. I had a really funny MIDI demo version of this that got deleted, so I had to remember it and teach it to the other guys. And then it turned into what you hear. It was just a really good framework for a couple of solos. It has a Steely Dan vibe now that I hear it—I wasn\'t really thinking of them at the time, but they\'re a big influence on us.\" **“Beside April (Reprise)”** “Before we had recorded the original version of \'Beside April,\' I was visiting my mom and I was playing on her piano and came up with this alternate version of it. We had some extra studio time one day, so I just recorded the piano part and then Verocai did his thing on it.” **“Talk Meaning”** “It was one of the last days in the studio and Terrace Martin came by for a couple of hours. We had run into him a lot on the road, but never got to do anything together in the studio. He was very generous with his time. Leland and Alex wrote the main melody and the chords for this, and then we wanted to play it in a jazz context, so we just showed Terrace the melody. This song had the most old-school mic setup: There\'s maybe a couple mics on the drums, one mic on the bass, and then one mic for both saxophones. So Leland and Terrace were both standing behind a baffle, and they had to move \[toward the mic\] and back depending on who was taking the lead. Then we added some keyboards and Verocai put an amazing arrangement on it. And for the finishing touch, we sent it to Brandee Younger, who\'s an amazing harpist, and she really took it to the next level and played a beautiful outro. It\'s really the most in-depth collaboration on this record.”

On his Red Hand Files website, Nick Cave reflected on a comment he’d made back in 1997 about needing catastrophe, loss, and longing in order for his creativity to flourish. “These words sound somewhat like the indulgent posturing of a man yet to discover the devastating effect true suffering can have on our ability to function, let alone to create,” he wrote. “I am not only talking about personal grief, but also global grief, as the world is plunged deeper into this wretched pandemic.” Whether he needs it or not, the Australian songwriter’s music does very often deal with catastrophe, loss, and longing. The pandemic didn’t inspire *CARNAGE* per se, but the challenges of 2020 clearly permitted both intense, lyric-stirring ideas and, with canceled tours and so on, the time and creativity to flesh them out with longtime collaborator and masterful multi-instrumentalist/songwriter Warren Ellis. The most direct reference to COVID-19 might be “Albuquerque,” a sentimental lamentation on the inability to travel. For the most part, Cave looks beyond the pandemic itself, throwing himself into a philosophical realm of meditations on humanity, isolation, love, and the Earth itself, depicted through observations and, as he is wont to do, taking on the roles of several other characters, sentient and otherwise. The album begins with “Hand of God.” There’s soft piano and lyrics about the search for “that kingdom in the sky,” until Ellis\' dissonant violin strikes away the sweetness and an electronic beat kicks in. “I’m going to the river where the current rushes by/I’m gonna swim to the middle where the water is real high,” he sings, a little manically, as he gives in to the current. “Hand of God coming from the sky/Gonna swim to the middle and stay out there awhile… Let the river cast its spell on me.” That unmitigated strength of nature is central to *CARNAGE*. Motifs of rivers, rain, animals, fields, and sunshine are used to depict not only the beauty and the bedlam he sees in the world, but the ways it changes him. On the sweet, delicate “Lavender Fields,” he sings of “traveling appallingly alone on a singular road into the lavender fields… the lavender has stained my skin and made me strange.” On “Carnage,” he sings of loss (“I always seem to be saying goodbye”), but also of love and hope, later depicting a “reindeer, frozen in the footlights,” who then escapes back into the woods. “It’s only love, with a little bit of rain,” goes the uplifting refrain. With its murky rhythm and snarling spoken-word lyrics, “White Elephant” is one of Cave’s most intense songs in years. It’s also the song that most explicitly references a 2020 event: the murder of George Floyd. “The white hunter sits on his porch with his elephant gun and his tears/He\'ll shoot you for free if you come around here/A protester kneels on the neck of a statue, the statue says, ‘I can’t breathe’/The protester says, ‘Now you know how it feels’ and he kicks it into the sea.” Later, he continues, as the hunter: “I’ve been planning this for years/I’ll shoot you in the f\*\*king face if you think of coming around here/I’ll shoot you just for fun.” It’s one of the only Nick Cave songs to ever address a racially, politically charged event so directly. And it’s a dark, powerful moment on this album. *CARNAGE* ends with a pair of atmospheric ballads—their soundscapes no doubt influenced by Cave and Ellis’ extensive work on film scores. On “Shattered Ground,” the exodus of a girl (a personification of the moon) invokes peaceful, muted pain—“I will be all alone when you are gone… I will not make a single sound, but come softly crashing down”—and “Balcony Man” depicts a man watching the sun and considering how “everything is ordinary, until it’s not,” tweaking an idiom with serene acceptance: “You are languid and lovely and lazy, and what doesn’t kill you just makes you crazier.” There is substantial pain, darkness, and loss on this album, but it doesn’t rip its narrator apart or invoke retaliation. Rather, he takes it all in, allowing himself to be moved and changed even if he can’t effect change himself. That challenging sense of being unable to do anything more than *observe* is synonymous with the pandemic, and more broadly the evolving, sometimes devastating world. Perhaps the lesson here is to learn to exist within its chaos—but to always search for beauty and love in its cracks.

*KID A MNESIA* isn’t just an occasion to revisit a pair of groundbreaking albums (2000’s *Kid A* and 2001’s *Amnesiac*), but a chance to hear a little of how Radiohead got there. Recording sessions were tough: Thom Yorke had writer’s block, and his new commitment to electronic music—or, at least, a turn away from conventional rock—left some of his bandmates wondering about their function and purpose. As guitarist Ed O’Brien once put it, he was a guitarist faced with a bunch of tracks that had no guitar. At one point, producer Nigel Godrich split the band into two groups: one working with instruments in the main recording area, the other in a programming room processing sounds from next door, all under the condition that no acoustic instruments—guitars, drums, etc.—be used. The constraints opened doors: Not only did the band discover new ways of working (and, by extension, refresh their passion for music after years of unyielding pressure), but, in doing so, they shifted the template for what we think of when we think of a rock band, mixing the acoustic and the electronic (“Everything in Its Right Place,” “Like Spinning Plates”) and relatively straightforward tracks (“Optimistic,” “Pyramid Song”) with fragmentary, discursive ones (“Kid A,” “Pulk/Pull Revolving Doors”). In the outtakes, we get glimpses of the band’s past (the paranoiac folk of “Follow Me Around“) and future (the deconstructed, full-band sound of “If You Say the Word”), as well as versions of “Like Spinning Plates” and “Pulk/Pull Revolving Doors” that chart their evolution in real time. It’s a snapshot of a band taking step back from themselves and the way they worked, finding a way forward in the process.

When Low started out in the early ’90s, you could’ve mistaken their slowness for lethargy, when in reality it was a mark of almost supernatural intensity. Like 2018’s *Double Negative*, *Hey What* explores new extremes in their sound, mixing Alan Sparhawk and Mimi Parker\'s naked harmonies with blocks of noise and distortion that hover in drumless space—tracks such as “Days Like These” and “More” sound more like 18th-century choral music than 21st-century indie rock. Their faith—they’ve been practicing Mormons most of their lives—has never been so evident, not in content so much as purity of conviction: Nearly 30 years after forming, they continue to chase the horizon with a fearlessness that could make anyone a believer.

Western Australian psych-rock band Pond’s ninth album might have been their first in over a decade that was recorded entirely on home turf (for pandemic reasons), but thematically it darts all over the place. There are biographical moments, with reflections on traveling, meaningful encounters, and thought-provoking conversations. There are observations on modern life, ancient mythology, gentrification, and tourism. There are wild improvisations taken from frenzied jam sessions, collaborations with artists near and dear to the band, ideas drawn from other creative minds and works, with lyrics that bounce from profound to funny to delightfully absurd. All in all, *9* feels like a series of musical vignettes, often focused entirely on a single person, thought, memory, or moment. Below, frontman Nick Allbrook talks through each song on the record. **“Song for Agnes”** “A tribute to Agnes Martin, with none of her zen delicacy—sorry. Took some lyrics from a letter she wrote to her art dealer which I thought was brilliant. \[French artist\] Maud Nadal did the ‘frail as people’ bit, which I love. A lot of this album’s lyrics are kind of biographical.” **“Human Touch”** “One time a woman was smashing up a car outside my house, begging me to help her steal it. She was wired but kind of sweet in a scary way. Her dog, named Josie, was sitting in the passenger seat being very cute and fluffy. GUM \[Jay Watson\]’s loop started it all musically.” **“America’s Cup”** “1987 was the year Fremantle was televised to the world and gentrification began in earnest. There are still relics of the pre-cup history floating around. It’s also about large, massive champions gathered outside a gym in London, who I thought were funny. The first line is lifted from \[Icelandic artist\] Ragnar Kjartansson, and the music came from a super fun jam. Hadn’t done that in ages and it was a gas.” **“Take Me Avalon I’m Young”** “When I was 17—cue strings—I went to England for my traditional Australian ‘gap year,’ to try and become worldly and feel like you’re bigger and better than your home. I went to Glastonbury, met some hippies and got trippy and slept on Glastonbury Tor. Turns out there’s a lot of wild mythology about that place if you look it up. The song’s about age, decay, changing, and the golden dream of England. I wanted to make a song with the drumbeat like the one that comes in at the end of ‘3 Legs’ by Paul McCartney. \[Pond drummer\] Ginoli and me did that. \[New York-based artist\] Jesse Kotansky did some mind-buggering strings on this one, and a couple others on the album. Champion.” **“Pink Lunettes”** “This came from another one of Jay’s crusty loops. Mainly him and Ginoli turned it wild and I just looked at my notebook and garbled over the top in a one-take vomit of pretentious art school tripe. It’s a chopped and screwed mosaic of once-coherent material from Leonard Cohen and Richter and Documenta X and some other things.” **“Czech Locomotive”** “More biography. Emil Zátopek and his incredible story totally squashed me. I’ve been running a lot recently, and his enormous heart and romantic soul and talent and strength and will killed me dead. The music came from the aforementioned improv sesh.” **“Rambo”** “An ode to the ‘unenlightened.’ I had a chat with a translator of very expensive poems who said you can’t make real art unless you’ve read Rimbaud, and I thought that was the most hilarious thing I’d ever heard in my life, and that person thought I was super cool for disagreeing. All very confusing really, but it made me not want to read another book ever again. ‘I should run and hide or die in the generational divide’ seems to be the mantra of the album, like ‘I might go and shack up in Tasmania’ was for \[2019 album\] *Tasmania*.” **“Gold Cup / Plastic Sole”** “Basically this is about the most well-trodden subject of the year—shit getting fucked-er and fucked-erer. I’m aging, and truths like slave labor producing my favorite slippers are turning every once-frivolous pleasure sour. Seeking solace in nature, Deia, love. There’s a really fantastic chord progression written by \[Pond guitarist\] Shiny Joe, ameliorated by brilliant twisted piano by \[Melbourne artist\] Evelyn Ida Morris and Jesse Kotansky strings.” **“Toast”** “Another ripper Joe chord progression. His demo was called ‘Toast’ and I think he was imagining warm, slightly burnt bread, but I wrote about the tourists in Broome watching the sunset and seeing the apocalypse and how I could never spend enough time with my love to make said apocalypse feel right.”

All rippers, no skippers, Sarah Tudzin’s second album as Illuminati Hotties imbues hooky Y2K-era pop-punk with an attitude that feels distinctly contemporary. Stretching her sweet-and-sour voice like taffy, Tudzin sings from the perspective of a millennial slacker who isn’t quite buying what society’s selling, be it marketing scams (“Threatening Each Other re: Capitalism”) or too-cool-for-school socialites (“Joni: LA’s No. 1 Health Goth”). She’s referred to her scrappy, bruised songs as “tenderpunk,” and beneath all the pool-hopping and kick-flipping, there’s a woman trying to pull off this adulting thing in what feels like end times. But in the meantime, why not try and have some fun?

Listening to Liz Harris’ music as Grouper, the word that comes to mind is “psychedelic.” Not in the cartoonish sense—if anything, the Astoria, Oregon-based artist feels like a monastic antidote to spectacle of almost any kind—but in the subtle way it distorts space and time. She can sound like a whisper whose words you can’t quite make out (“Pale Interior”) and like a primal call from a distant hillside (“Followed the ocean”). And even when you can understand what she’s saying, it doesn’t sound like she meant to be heard (“The way her hair falls”). The paradox is one of closeness and remove, of the intimacy of singer-songwriters and the neutral, almost oracular quality of great ambient music. That the tracks on *Shade*, her 12th LP, were culled from a 15-year period is fitting not just because it evokes Harris’ machine consistency (she found her creative truth and she’s sticking to it), but because of how the staticky, white-noise quality of her recordings makes you aware of the hum of the fridge and the hiss of the breeze: With Grouper, it’s always right now.

Released without warning as the surprise companion to volumes two through four, *kiCK iiiii* is the most understated entry in the whole series. In place of psychedelic club beats or crushing distortion, Arca gives us twinkling little miniatures like “Pu,” “Chiquito,” and “Estrogen,” which shrink chamber music’s piano and strings down to snow-globe proportions. Arca’s heartbreaking falsetto turn on “Tierno” recalls the naked simplicity of her vocals on her 2017 self-titled album, and on “Músculos,” unsteady beats once again re-enter the frame, a reminder of the Venezuelan musician’s debt to Björk. *kiCK iiiii* may be the softest album in the pentalogy, but it has a hushed, glowing magnetism all its own.

The retro-futuristic duo (Mica Tenenbaum and Matthew Lewin) hails from LA by way of the uncanny Valley, churning out trippy DIY videos made from random VHS footage and mailing weird brochures to fans like a secretive cult. But on debut full-length *Mercurial World*, their polished synth-pop demands to be taken seriously, though their playful spirit abides—emulating the effects of a VOCALOID with their mouths, kicking off the album with a track called “The End.” Tenenbaum and Lewin blend the nostalgic with the contemporary, combining Y2K-era bubblegum, the disco grooves of mid-aughts indie-dance crossovers, and the space-age sheen of hyperpop for a 45-minute sugar rush; don’t miss “Chaeri,” 2021’s best pop song about being a bad friend.

www.mercurialworld.com

Ten years after the clangorous thrills of their debut LP, *New Brigade*, Iceage’s apocalyptic punk has led here: a hunger for comfort, refined goth grandeur. “If the last record is us heading out into a storm and feeling content doing so, this record is situated in the storm—longing for something we didn\'t have,” Iceage frontman Elias Bender Rønnenfelt tells Apple Music. “That could be shelter.” *Seek Shelter*, the Copenhagen band’s fifth studio album, is the group’s most expansive. Recording across 12 days in Lisbon, Portugal, the band worked with an outside producer for the first time—Sonic Boom (Spacemen 3’s Pete Kember). (“He’s a good bullshitter,” Rønnenfelt says.) *Seek Shelter* maintains the tenacity of the band’s hardcore roots, elevated with lush, unexpected experimentation, neo-psych dynamism (“Shelter Song”), a bluesy sinister dance (“Vendetta”), a fiery slow-burn and thunderous crescendo (“The Holding Hand”), and a mid-song interpolation of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” (“High & Hurt”). Below, Rønnenfelt takes us inside *Seek Shelter*, track by track. **“Shelter Song”** “We thought that a gospel choir would be the exact right thing. Cut forward: We\'re on the last day in Lisbon. We\'ve been bunkered up there for 12 days, collectively losing our minds, not necessarily knowing how to feel about everything we put down on tape. And having never worked with a choir before, we didn\'t really know if we were going to be able to speak the same language, but they instantly got it. They started flowing with the song and harmonizing and taking it in all sorts of directions. It became a very lovely collaboration.” **“High & Hurt”** “The melody started getting incorporated before we remembered what that hymn was. The lyrics of this song are, by nature, really quite scumbag-y, in a mythical sort of way. So it felt too tempting not to include ‘Will the Circle Be Unbroken.’ The contrast between that song and the additional lyrics felt kind of wrong, but deliciously so, you know?” **“Love Kills Slowly”** “Before the choir came in, I thought I was singing almost pitch perfect. As soon as my voice was paired with people who can actually sing, it became very apparent how rugged and broken it still is. I\'ve tried to make the lyrics as simple as possible, but that\'s the hardest thing to approach. How do you state something so obvious, but make it feel urgent and relevant and like it belongs to you? I\'m somebody who has always had a tendency to make lyrics overly voluptuous. This was an exercise in stripping things down. And of course it is still a bit corrupted.” **“Vendetta”** “‘Vendetta’ came about from me lending my little sister\'s plastic toy-store keyboard. I slowed the tempo way down and started playing with it. It is interesting to pair the pounding, dancy feel of the track with speaking about the omnipresence of crime in the world and have it be this discordant dance. We are always attracted to dualities, I guess. Traveling the world and growing up in Copenhagen or anywhere, you never have to scratch the surface very hard to discover that crime is an essential glue that binds a lot of society together.” **“Drink Rain”** “Definitely the most bizarre thing we ever been involved with writing. This was one of those moments where your hands just start writing, and then you take a look at a paper and you\'re like, \'What is this thing that I just wrote?\' It\'s this perverse creep that lurks around drinking from puddles of rain in the streets, because he has some delusion that it might bring him closer to some kind of love interest. In the studio, when we first listened back to the first take of it, we were like, \'I\'m not sure if we should be doing this.\' It feels like a transgression.” **“Gold City”** “It’s a ballad that speaks to how moments can be determined by a lot of factors culminating together: the weather, the air, your company, the levels of chemicals in your brain. Everything rumbles together.” **“Dear Saint Cecilia”** “It\'s a bit drunken and raving, and I wouldn\'t say uplifting. It\'s carefree, but also moving within chaos and trying to evoke the Catholic patron saint. It’s just a very carefree song that charges through the chaos of a modern society.” **“The Wider Powder Blue”** “It started out with one of my old heroes, Peter Schneidermann, who played in Denmark\'s first punk band, Sods. He recorded our first EP when we were 16, and he has always been a hero of mine. He asked me to write a song. I started out with what became this and I became too attached to it. I couldn\'t give it to him. That song is an ode to him and how his insane genius is quite morbid, but ultimately a glorious thing.” **“The Holding Hand”** “I can\'t remember the name in English for the instrument, but we had…like a xylophone, tubes of aluminum, or some kind of metal. The song is quite an abstract one, like a landscape scene in itself. It\'s more about describing a feeling of being in the world than describing the actual world. It plays with notions of power, how strength is sometimes weakness and how weakness is sometimes strength. It has this lost beauty in all that.”

“I’ve had a lot of controversies in my short period being an artist,” slowthai tells Apple Music. “But I always try making a statement.” In 2019, there was the Northampton rapper’s establishment-rattling appearance at the Mercury Prize ceremony, hoisting of an effigy of Boris Johnson’s severed head. A few months later, sexualized comments he made to comedian Katherine Ryan at the 2020 NME Awards caused a fierce Twitter backlash and prompted the Record Store Day 2020 campaign to withdraw an invitation for slowthai to be its UK ambassador. Ryan labeled their exchange “pantomime” but it led to a confrontation with an audience member and slowthai’s apology for his “shameful actions.” Since releasing his 2019 debut *Nothing Great About Britain*, then, the artist born Tyron Frampton has known the unforgiving heat of public judgment. It’s helped forge *TYRON*, a follow-up demarcated into two seven-track sides. The first is brash, incendiary, and energized, continuing to draw a through line between punk and UK rap. The second is vulnerable and introspective, its beats more contemplative and searching. The overarching message is that there are two sides to every story, and even more to every human being. “We all have the side that we don’t show, and the side we show,” he says. “Living up to expectations—and then not giving a fuck and just being honest with yourself.” Featuring guests including Skepta, A$AP Rocky, James Blake, and Denzel Curry, these songs, he hopes, will offer help to others feeling penned in by judgment, stereotypes, or a lack of self-confidence. “I just want them to realize they’re not alone and can be themselves,” he says. “I know that when shit gets dark, you need a little bit of light.” Explore all of slowthai’s sides with his track-by-track guide. **45 SMOKE** “‘Rise and shine, let’s get it/Bumbaclart dickhead/Bumbaclart dickhead.’ It’s like the wake-up call for myself. It’s how you feel when you’re making constant mistakes, or you’re in a rut and you wake up like, ‘I really don’t want to wake up, I’d rather just sleep all day.’ It’s explaining where I’m from, and the same routine of doing this bullshit life that I don’t want to do—but I’m doing it just for the sake of doing it or because this is what’s expected of me.” **CANCELLED** “This song’s a fuck-you to the cancel culture, to people trying to tear you down and make it like you’re a bad person—because all I’ve done my whole life is try and escape that stereotype, and try and better myself. You can call me what you want, you can say what you think happened, but most of all I know myself. Through doing this, I’ve figured it out on a deeper level. When we made this, I was in a dark place because of everything going on. And Skep \[Skepta, co-MC on this track\] was guiding me out. He was saying, ‘Yo, man, this isn’t your defining moment. If anything, it pushes you to prove your point even more.’” **MAZZA** “Mazza is ‘mazzalean,’ which is my own word... It\'s just a mad thing. It’s for the people that have mad ADHD \[slowthai lives with the disorder\], ADD, and can’t focus on something—like how everything comes and it’s so quick, and it’s a rush. It’s where my head was at—be it that I was drinking a lot, or traveling a lot, and seeing a lot of things and doing a lot of dumb shit. Mad time. As soon as I made it, I FaceTimed \[A$AP\] Rocky because I was that gassed. We’d been working here and there, doing little bits. He was like, ‘This is hard. Come link up.’ He was in London and I went down there and \[we\] just patterned it out.” **VEX** “It’s just about being angry at social media, at the fakeness, how everyone’s trying to be someone they’re not and showing the good parts of their lives. You just end up feeling shit, because even if your life’s the best it could be, it just puts in your head that, ‘Ah, it could always be better.’ Most of these people aren’t even happy—that’s why they\'re looking for validation on the internet.” **WOT** “I met Pop Smoke, and that night I recorded this song. It was the night he passed. The next morning, I woke up at 6 am to go to the Disclosure video shoot \[for ‘My High’\] and saw the news. I was just mad overwhelmed. Initially, I’d linked up with Rocky, making another tune, but he didn’t finish his bit. \[slowthai’s part\] felt like it summed it up the energies—it was like \[Pop Smoke’s\] energy, just good vibes. I felt like I wouldn\'t make it any longer because it’s straight to the point. As soon as it starts, you know that it’s on.” **DEAD** “We say ‘That’s dead’ as in it’s not good, it’s shit. So I was like, ‘Yo, every one of these things is dead to me.’ There’s a line, ‘People change for money/What’s money with no time?’ That’s aimed at people saying I changed because I gained success. It’s not that I’ve changed, but I’ve grown or grown out of certain things. It’s not the money that changed me, it’s understanding that doing certain things is not making me any better. If I’m spending all my time working on bettering myself and trying to better my craft, the money’s irrelevant. I don’t even have the time to spend it. So it’s just like saying everything’s dead. I’m focusing on living forever through my music and my art.” **PLAY WITH FIRE** “Even though we want to move far away from situations and circumstances, we keep toying with the idea \[of them\]. It plays on your mind that you want to be in that position. ‘PLAY WITH FIRE’ is the letting go as well as trying to hold on to these things. When it goes into \[next track\] ‘i tried,’ it’s like, ‘I tried to do all these things, live up to these expectations and be this person, but it wasn’t working for me.’ And on the other foot, I *tried* all these things. I can’t die saying I didn’t. You have to love everything for how it is to understand it, and try and move on. You’ve got to understand something for the negative before you can really understand the positive.” **i tried** “‘Long road/Tumble down this black hole/Stuck in Sunday league/But I’m on levels with Ronaldo.’ It’s saying it’s been a struggle to get here. And even still, I feel like I’m traveling into a void. You feel like you’re sinking into yourself—be it through taking too many drugs or drinking too much and burying yourself in a hole, just being on autopilot. It’s coming to that understanding, and dealing with those problems. It’s \[about\] boosting my confidence and my true self: ‘Yo, man, you’re the best. If this was football, you’d be the Ballon d’Or winner.’ We always look at what we think we should be like. We never actually look at who we are, and what our qualities are. ‘I’ve got a sickness/And I’m dealing with it.’ I’m trying. I\'m trying every avenue, and with a bit of hope and a bit of luck, I can become who I want to be.” **focus** “From the beginning, even though I’m in this pocket of people and this way of life, I’ve always known to go against that grain. I didn’t ever want to end up in jail. You either get a trade or you end doing shit and potentially you end in jail. A lot of people around me, they’re still in that cycle. And this is me saying, ‘Focus on some other shit.’ I come from the shit, and I pushed and I got there. And it was through maintaining that focus.” **terms** “It’s the terms and conditions that come with popularity and...fame. I don’t like that word. I hate words like ‘fad’ and ‘fame.’ They make me cringe so much. Maybe I’ve got something against words that begin with F. But it’s just dealing with what comes with it and how it’s not what you expected it to be. The headache of being judged for being a human being. Once you get any recognition for your art, you’re no longer a human—you’re a product. Dominic \[Fike, guest vocalist\] sums it up beautifully in the hook.” **push** “‘Push’ is an acronym for ‘praying until something happens.’ When you’re in a corner, you’ve got to keep pushing. Even when you’re at your lowest. That’s all life is, right? It’s a push. Being pulled is the easy route, but when you’re pushing for something, the hard work conditions your mind, strengthens you physically and spiritually, and you come out on top. I used to be religious—when my brother passed, when I was young. I asked for a Bible for my birthday, which was some weird shit. Through this project…it’s not faith in God, but my faith in people, it’s been kind of restored, my faith in myself. Everyone I work with on this, they’re my friends, and they’re all people that have helped me through something. And Deb \[Never, guest vocalist\]—we call each other twins. She’s my sister that I’ve known my whole life but I haven’t known my whole life.” **nhs** “It’s all about appreciation. The NHS—something that’s been doing work for generations, to save people—it’s been so taken for granted. It’s a place where everyone’s equal and everyone’s treated the same. It takes this \[pandemic\] for us to applaud people who have been giving their lives to help others. They should have constant applause at the end of every shift. We’re out here complaining and always wanting more. I don’t know if it’s a human defect or just consumerism, but you get one thing and then you always want the next best thing. I do it a lot. And there’s never a best one, because there’s always another one. Just be happy with what you’ve got. You\'ll end up having an aneurysm.” **feel away** “Dom \[Maker, co-producer and one half of Mount Kimbie\] works with James \[Blake\] a lot. They record a bunch of stuff, chop it up and create loops. I was going through all these loops, and I was like, ‘This one’s the one.’ As soon as we played it, I had lyrics and recorded my bit. I’ve loved James from when I was a kid at school and was like, ‘We should get James.’ We sent it to him, and in my head, I was like, ‘Ah, he’s not going to record on it.’ But the next day, we had the tune. I was just so gassed. I dedicated it to my brother passing. But it’s about putting yourself in your partner’s shoes, because through experiences, be it from my mum or friends, I’ve learnt that in a lot of relationships, when a woman’s pregnant, the man tends to leave the woman. The woman usually is all alone to deal with all these problems. I wanted it to be the other way around—the woman leaves the man. He’s got to go through all that pain to get to the better side, the beauty of it.” **adhd** “When I was really young, my mum and people around me didn’t really believe in \[ADHD\]—like, ‘It’s a hyperactive kid, they just want attention.’ They didn’t ever see it as a disorder. And I think this is my way of summarizing the whole album: This is something that I’ve dealt with, and people around me have dealt with. It’s hard for people to understand because they don’t get why it’s the impulses, or how it might just be a reaction to something that you can’t control. You try to, but it’s embedded in you. It’s just my conclusion—like at the end of the book, when you get to the bit where everything starts making sense. I feel like this is the most connected I’ve been to a song. It’s the clearest depiction of what my voice naturally sounds like, without me pushing it out, or projecting it in any way, or being aggressive. It’s just softly spoken, and then it gets to that anger at the end. And then a kiss—just to sweeten it all up.”

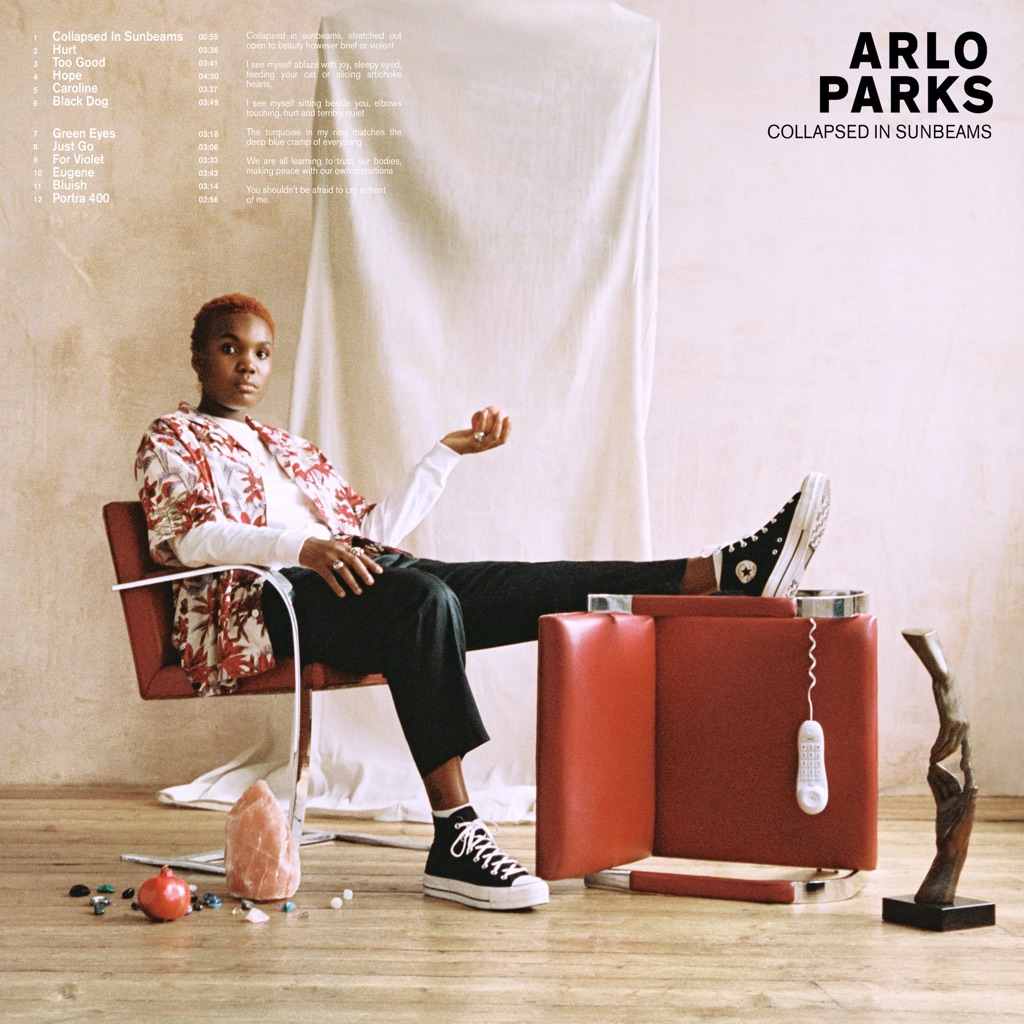

“I don’t like to agonize over things,” Arlo Parks tells Apple Music. “It can tarnish the magic a little. Usually a song will take an hour or less from conception to end. If I listen back and it’s how I pictured it, I move on.” The West London poet-turned-songwriter is right to trust her “gut feeling.” *Collapsed in Sunbeams* is a debut album that crystallizes her talent for chronicling sadness and optimism in universally felt indie-pop confessionals. “I wanted a sense of balance,” she says. “The record had to face the difficult parts of life in a way that was unflinching but without feeling all-consuming and miserable. It also needed to carry that undertone of hope, without feeling naive. It had to reflect the bittersweet quality of being alive.” *Collapsed in Sunbeams* achieves all this, scrapbooking adolescent milestones and Parks’ own sonic evolution to form something quite spectacular. Here, she talks us through her work, track by track. **Collapsed in Sunbeams** “I knew that I wanted poetry in the album, but I wasn\'t quite sure where it was going to sit. This spoken-word piece is actually the last thing that I did for the album, and I recorded it in my bedroom. I liked the idea of speaking to the listener in a way that felt intimate—I wanted to acknowledge the fact that even though the stories in the album are about me, my life and my world, I\'m also embarking on this journey with listeners. I wanted to create an avalanche of imagery. I’ve always gravitated towards very sensory writers—people like Zadie Smith or Eileen Myles who hone in on those little details. I also wanted to explore the idea of healing, growth, and making peace with yourself in a holistic way. Because this album is about those first times where I fell in love, where I felt pain, where I stood up for myself, and where I set boundaries.” **Hurt** “I was coming off the back of writer\'s block and feeling quite paralyzed by the idea of making an album. It felt quite daunting to me. Luca \[Buccellati, Parks’ co-producer and co-writer\] had just come over from LA, and it was January, and we hadn\'t seen each other in a while. I\'d been listening to plenty of Motown and The Supremes, plus a lot of Inflo\'s production and Cleo Sol\'s work. I wanted to create something that felt triumphant, and that you could dance to. The idea was for the song to expose how tough things can be but revolve around the idea of the possibility for joy in the future. There’s a quote by \[Caribbean American poet\] Audre Lorde that I really liked: ‘Pain will either change or end.’ That\'s what the song revolved around for me.” **Too Good** “I did this one with Paul Epworth in one of our first days of sessions. I showed him all the music that I was obsessed with at the time, from ’70s Zambian psychedelic rock to MF DOOM and the hip-hop that I love via Tame Impala and big ’90s throwback pop by TLC. From there, it was a whirlwind. Paul started playing this drumbeat, and then I was just running around for ages singing into mics and going off to do stuff on the guitar. I love some of the little details, like the bump on someone’s wrist and getting to name-drop Thom Yorke. It feels truly me.” **Hope** “This song is about a friend of mine—but also explores that universal idea of being stuck inside, feeling depressed, isolated, and alone, and being ashamed of feeling that way, too. It’s strange how serendipitous a lot of themes have proved as we go through the pandemic. That sense of shame is present in the verses, so I wanted the chorus to be this rallying cry. I imagined a room full of people at a show who maybe had felt alone at some point in their lives singing together as this collective cry so they could look around and realize they’re not alone. I wanted to also have the little spoken-word breakdown, just as a moment to bring me closer to the listener. As if I’m on the other side of a phone call.” **Caroline** “I wrote ‘Caroline’ and ‘For Violet’ on the same, very inspired day. I had my little £8 bottle of Casillero del Diablo. I was taken back to when I first started writing at seven or eight, where I would write these very observant and very character-based short stories. I recalled this argument that I’d seen taken place between a couple on Oxford Street. I only saw about 30 seconds of it, but I found myself wondering all these things. Why was their relationship exploding out in the open like that? What caused it? Did the relationship end right there and then? The idea of witnessing a relationship without context was really interesting to me, and so the lyrics just came out as a stream of consciousness, like I was relaying the story to a friend. The harmonies are also important on this song, and were inspired by this video I found of The Beatles performing ‘This Boy.’ The chorus feels like such an explosion—such a release—and harmonies can accentuate that.” **Black Dog** “A very special song to me. I wrote this about my best friend. I remember writing that song and feeling so confused and helpless trying to understand depression and what she was going through, and using music as a form of personal catharsis to work through things that felt impossible to work through. I recorded the vocals with this lump in my throat because it was so raw. Musically, I was harking back to songs like ‘Nude’ and ‘House of Cards’ on *In Rainbows*, plus music by Nick Drake and tracks from Sufjan Stevens’ *Carrie & Lowell*. I wanted something that felt stripped down.” **Green Eyes** “I was really inspired by Frank Ocean here—particularly ‘Futura Free’ \[from 2016’s *Blonde*\]. I was also listening to *Moon Safari* by Air, Stereolab, Unknown Mortal Orchestra, Tirzah, Beach House, and a lot of that dreamy, nostalgic pop music that I love. It was important that the instrumental carry a warmth because the song explores quite painful places in the verses. I wanted to approach this topic of self-acceptance and self-discovery, plus people\'s parents not accepting them and the idea of sexuality. Understanding that you only need to focus on being yourself has been hard-won knowledge for me.” **Just Go** “A lot of the experiences I’ve had with toxic people distilled into one song. I wanted to talk about the idea of getting negative energy out of your life and how refreshed but also sad it leaves you feeling afterwards. That little twinge from missing someone, but knowing that you’re so much better off without them. I was thinking about those moments where you’re trying to solve conflict in a peaceful way, but there are all these explosions of drama. You end up realizing, ‘You haven’t changed, man.’ So I wanted a breakup song that said, simply, ‘No grudges, but please leave my life.’” **For Violet** “I imagined being in space, or being in a desert with everything silent and you’re alone with your thoughts. I was thinking about ‘Roads’ by Portishead, which gives me that similar feeling. It\'s minimal, it\'s dark, it\'s deep, it\'s gritty. The song covers those moments growing up when you realize that the world is a little bit heavier and darker than you first knew. I think everybody has that moment where their innocence is broken down a little bit. It’s a story about those big moments that you have to weather in friendships, and asking how you help somebody without over-challenging yourself. That\'s a balance that I talk about in the record a lot.” **Eugene** “Both ‘Black Dog’ and ‘Eugene’ represent a middle chapter between my earlier EPs and the record. I was pulling from all these different sonic places and trying to create a sound that felt warmer, and I was experimenting with lyrics that felt a little more surreal. I was talking a lot about dreams for the first time, and things that were incredibly personal. It felt like a real step forward in terms of my confidence as a writer, and to receive messages from people saying that the song has helped get them to a place where they’re more comfortable with themselves is incredible.” **Bluish** “I wanted it to feel very close. Very compact and with space in weird places. It needed to mimic the idea of feeling claustrophobic in a friendship. That feeling of being constantly asked to give more than you can and expected to be there in ways that you can’t. I wanted to explore the idea of setting boundaries. The Afrobeat-y beat was actually inspired by Radiohead’s ‘Identikit’ \[from 2016’s *A Moon Shaped Pool*\]. The lyrics are almost overflowing with imagery, which was something I loved about Adrianne Lenker’s *songs* album: She has these moments where she’s talking about all these different moments, and colors and senses, textures and emotions. This song needed to feel like an assault on the senses.” **Portra 400** “I wanted this song to feel like the end credits rolling down on one of those coming-of-age films, like *Dazed and Confused* or *The Breakfast Club*. Euphoric, but capturing the bittersweet sentiment of the record. Making rainbows out of something painful. Paul \[Epworth\] added so much warmth and muscularity that it feels like you’re ending on a high. The song’s partly inspired by *Just Kids* by Patti Smith, and that idea of relationships being dissolved and wrecked by people’s unhealthy coping mechanisms.”

“We wanted it to be bold. We didn’t want it to be an allusion to anything. We just wanted it to be what it is, like when you see a Renaissance painting called *Man Holding Fish at the Market While Other People Walk By*.” So says vocalist/guitarist Adam Vallely of The Armed about the title of the band’s fourth album, *Ultrapop*. The previously anonymous Detroit hardcore collective revealed their identities with the record’s announcement in early 2021—or so they’d have listeners believe. And while Vallely (if that’s his real name) certainly seems to be involved, along with folks named “Dan Greene,” “Cara Drolshagen,” and Urian Hackney (an actual person and drummer), one never knows. What seems almost certainly true is that *Ultrapop* features guest appearances from Mark Lanegan, Troy Van Leeuwen (Queens of the Stone Age), Ben Chisholm (Chelsea Wolfe), and Kurt Ballou (Converge), who may or may not have produced the album. Below, Vallely discusses each track. **“Ultrapop”** “We wanted to open with a track that immediately made clear what our intentions were on this record. We wanted to throw you in the deep end. A big element aesthetically was trying to combine the most beautiful things with the most ugly things: There’s these really nice vocal arrangements that are pretty up-front, and then you have these power electronics and harsh noise accompanying it. So putting this song first is incredibly intentional. If you don\'t like this, you might as well get the fuck out right now.” **“All Futures”** “Whereas ‘Ultrapop’ is throwing you in the deep end, we wanted this to be like a distillation of all the various elements you hear on the album. We wanted it to be very catchy, very cleverly composed, and really good. The first guitar lead is very St. Vincent-influenced, then Jonni Randall’s lead in the chorus has a very Berlin-era Iggy sound. Lyrically, it’s an anti-edgelord anthem. It’s saying that just pointing out your distaste for things is not inherently a contribution. It’s okay to dislike things, but if you’re devoting all your energy to contrarianism, you’re just anti.” **“Masunaga Vapors”** “Keisuke Masunaga was one of the illustrators of the \[anime\] show *Dragon Ball Z*. He had a very distinct style with angularity and noses and eyes. But the song itself is based on Stéphane Breitwieser, who is a super notorious and prolific art thief from France who felt really connected to the pieces he would steal from museums. It’s a super chaotic but kind of uplifting song, and the whole thing is a confrontation about ownership and attribution in art and what belongs to who—and does any of it matter?” **“A Life So Wonderful”** “The title just seemed like a really not nihilistic, not metal, not hardcore thing to say, and it’s applied somewhat ironically to the lyrical content of the song. Dan Greene wrote about 90 percent of it. He always works in this MIDI program that sounds like an old Nintendo game and then we have to apply real instrumentation. Lyrically, it’s about the deterioration of truth as a societal construct and how dangerous that can be. I know, a real original theme for 2021, but that’s what it’s about—information warfare, destabilization, and the eventual numbness that can come from that.” **“An Iteration”** “This song was actually written almost in full during the *Only Love* sessions. But I think we all just felt that it was a bridge too far for that album, contextually—which was a real hard decision to make and made us feel like adult artists. But it’s one of my favorites on either of the records. Ben Chisholm really helped us nail this one and make it stronger. You can hear Nicole Estill from True Widow doubling my main vocal on everything, and then you can hear Jess Hall, who also sang on ‘Ultrapop,’ doing the hooks, because we wanted those to be real poppy.” **“Big Shell”** “Around 2016, we started doing these splinter groups where just a few of us would play in Detroit under different names. We would play material that we were not sure if it was Armed material. This is one of those songs, and we decided it was definitely a good song for The Armed. It’s probably the most rock-oriented track on the album, and it’s really satisfying. Cara wrote the lyrics, but I know she’s speaking about presenting your real self to the world and letting anyone who doesn’t like it deal with it on their own accord, which is sort of the spirit of *Ultrapop* throughout.” **“Average Death”** “This is the very first song we worked on with Ben Chisholm, and it really cemented the collaboration. It’s got this cool angular drum beat and this weird, lurching sort of groove throughout. Ben added a lot of gorgeous synths and the vocal break leading into the chorus. Urian did this undulating blastbeat that gives it these cool accents. But it’s a huge bummer lyrically—it’s about the abuses of actresses in 1930s Hollywood, that studio structure which is unfortunately a systemic issue that has not quite rooted itself out nearly a hundred years later.” **“Faith in Medication”** “The bassline is kinda crazy, and there\'s a guitar solo by Andy Pitcher towards the end. He’s channeling serious \'90s-era Reeves Gabrels—you can hear that the guitar doesn\'t have a headstock. Urian is absolutely beating the shit out of the drums with those cascading fills. Dan is obsessed with the visuals of \'80s and \'90s mecha-based anime where you see the fucking Gundams having some sort of dogfight in space. That\'s how he wanted the song to feel, and I think it absolutely feels like that.” **“Where Man Knows Want”** “The track opens very sparse, and then it quickly lets the normal The Armed reveal itself in the choruses. Not unlike ‘All Futures,’ the beginning clearly owes a lot to Annie Clark. Kurt Ballou is playing everything you hear at the end that sounds like a stringed instrument. He’s the king of playing those heavy chords punctuated by feedback. Lyrically, the song is talking about the creative curse, the obsession with having a new idea and executing it—and tricking yourself into thinking that when you finish this, you can rest. But it never quite works that way.” **“Real Folk Blues”** “Like ‘Masunaga Vapors,’ this song references a real person—Tony Colston-Hayter, who was this legendary acid-house rave promoter from the \'80s who then in the mid-2010s was arrested for hacking into bank accounts and stealing a million pounds. The reason we became obsessed with the story is because he was hacking into the accounts using this insane machine that was like a pitch-shifting pedal taped to something else that basically allowed him to alter the gender of his voice and play prerecorded bank messages that would trick the systems to get into what he needed to get into.” **“Bad Selection”** “This one was largely experimental as we were crafting it. We just wanted to break new ground with something, I think it’s very successful at doing that. Lyrically, it’s interesting because there’s a duality that presents the listener with a Choose Your Own Adventure kind of thing. With the chorus, is it about someone who’s keeping the faith in a better future, or is it about people being blinded by a violent faith in better days that had already gone by? One is really optimistic and one is very sinister, and they allude to real-world things.” **“The Music Becomes a Skull” (feat. Mark Lanegan)** “This takes an unexpected dark and dismal turn at the end of the sugar rush that is the rest of the record. Dan had a specific vision for the vocals that our immediate group of collaborators couldn’t really execute on. We were talking about it with Ben Chisholm and Dan said, ‘We need Mark Lanegan to sing on it.’ I think he meant we needed someone that sounds like that. We didn’t expect to actually get Mark Lanegan. But within 24 hours, we had vocals from Mark Lanegan. As inconvenient as a collaborative effort like The Armed can be, it can also lead to something like this. I mean, I’m singing with Mark Lanegan on this. It’s so fucking cool.”

As a lifelong fan of anime, Steven Ellison was struck by the lack of Black characters in the genre. So he decided to do something about it, signing on as an executive producer of *Yasuke*, a Netflix series from creator LeSean Thomas about a Black samurai in feudal Japan. Naturally, Ellison—aka Flying Lotus—scored the series too. An extension of the genre-free experiments of his solo catalog, his soundtrack for the show doubles as an ambitious act of world-building. Produced under the kinds of deadlines that don’t normally apply to his sprawling albums, this one moves quickly through different moods and styles: “War at the Door” pairs traces of trap and footwork with blockbuster-grade drums; “Your Lord” plants its flag halfway between easy listening and John Carpenter; the ambient “Shoreline Sus” negotiates a truce between ’70s Berlin and ’80s Japan. Soft tendrils of synthesizer, reminiscent of Vangelis’ *Blade Runner* soundtrack, serve as a through line for the album, highlighting its sci-fi glow, though a few tracks, like the jazz-funk “Crust,” wouldn’t sound out of place on one of FlyLo’s studio LPs. And while the music is largely instrumental, a few standout vocal tracks rank among the musician’s most affecting songwriting. “Hiding in the Shadows,” featuring Niki Randa, is a quietly operatic lullaby set to Japanese strings; “Black Gold,” the protagonist’s theme song, makes the most of Thundercat’s wistful falsetto. And a feature from Denzel Curry helps turn “African Samurai” into a minimalist masterpiece. A pulse-quickening showdown between blippy electronic beats and Curry’s lightning-fast flow, it’s the musical equivalent of blades slicing through air.

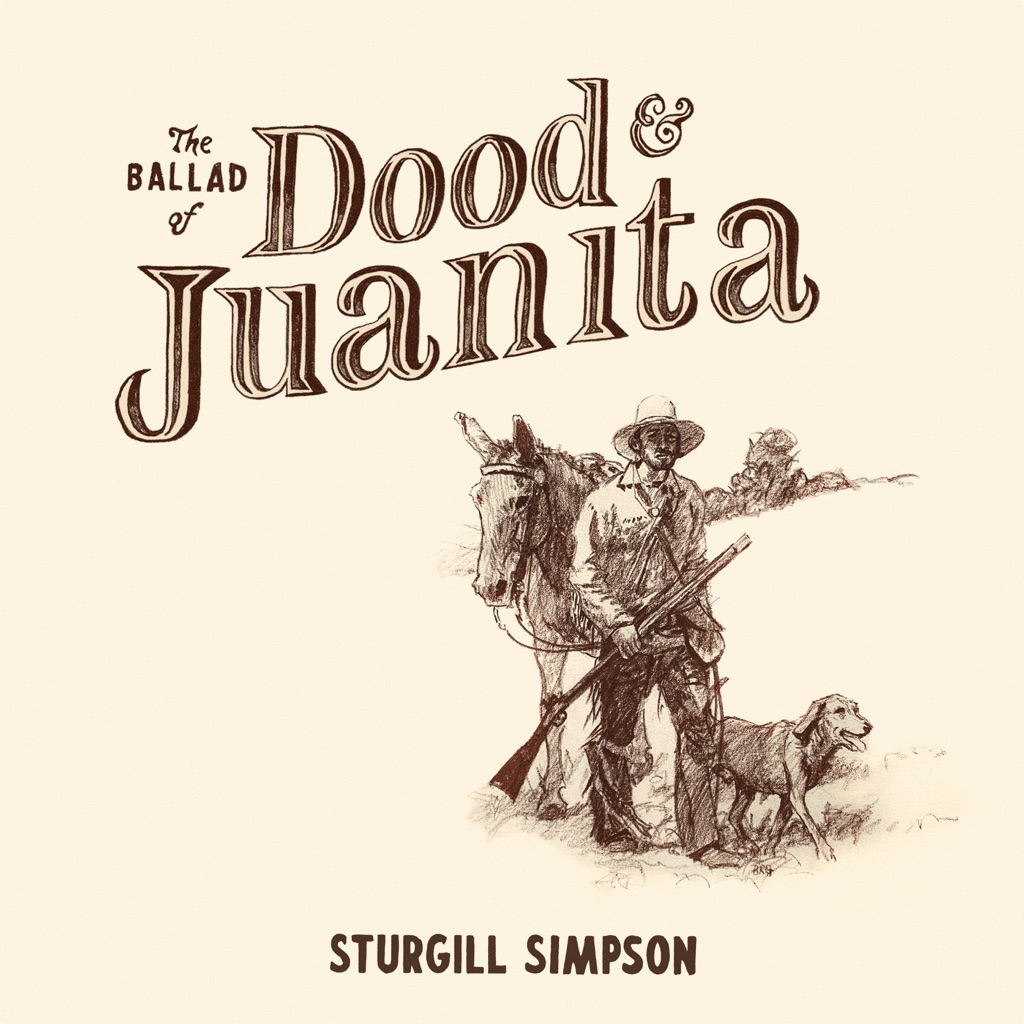

Sturgill Simpson has made several sonic detours over the last few years, sharply veering away from the cosmic country of his breakout 2014 album *Metamodern Sounds in Country Music*, particularly into prog rock on 2019’s *SOUND & FURY* and revisiting his bluegrass roots on the 2020 releases *Cuttin’ Grass, Vol. 1 (Butcher Shoppe Sessions)* and *Cuttin’ Grass, Vol. 2 (Cowboy Arms Sessions)*. *The Ballad of Dood & Juanita* falls more squarely in the latter’s territory, pulling from bluegrass, gospel, traditional country, and mountain music. Thematically, *Dood & Juanita* is a concept album, telling a continuous narrative throughout, something Simpson flirted with in the past but had yet to fully explore. And while Simpson has plenty of his own bona fides, tapping Willie Nelson to join him on “Juanita” sweetens the deal, offering a direct connection to the very lineage Simpson sets out to celebrate.

In many ways, Jimmy Edgar’s fourth solo album is a tribute to the glitz and grit of Los Angeles. The Detroit native moved there after a stint in Berlin—having burned out on the German city’s obsession with underground cool—and was soon connected to the visionary producer SOPHIE, who shifted his perspective on the role of art. “She always made a point of saying, ‘Listen, I’m actually *trying* to make mainstream music. I’m not interested in staying underground,” he tells Apple Music. “To her, that was more radical. You just had to believe your weird sound was worthy of big artists, and I did.” SOPHIE died tragically a few weeks before *CHEETAH BEND* was released, but her fingerprints are all over the album, he says, from the cartoonish, mechanical textures to the charismatic, flashy features. “LA revolves around fame and success,” he says. “She encouraged me to use that, to examine it, to riff on it.” Zigzagging between jagged, dizzying trap and bleary-eyed hip-hop with flickers of techno, hyper-pop, and R&B, the project feels less like a statement on the state of modern pop music and more like a dream of what it *could* be. Below, the shape-shifting producer takes us inside five of his favorite tracks. **CURVES** “The day I recorded this, SOPHIE and I went to Disneyland. She had VIP tickets because she didn\'t want to wait in line. Afterwards, we got sushi and she was like, ‘Hey, so Vince Staples is having a session if you want to go?’ When we got there, she insisted I play a track for him, and it wound up being the last track on his album *Big Fish Theory*. After we left, she was like, ‘So Charli XCX is in this other studio, do you want to go?’ It turned out to be Charli, A. G. Cook, and Noonie Bao, and we just started playing around. I wrote ‘CURVES’ in that session. It was initially going to be for Charli, but I think you can hear SOPHIE’s influence just from her being in the room. It\'s a big texture collage that has this physical bounce and bump to it.” **GET UP (feat. Danny Brown)** “I’d gone to Detroit and Danny showed up at the studio. I played him a bunch of different beats, but I had one track that I felt was particularly strong, so I ended with that. When I played it, one of his roommates who was asleep on the couch literally jumped up and was like, ‘DAMN! This is the one! This is the one!’ I just remember smiling ear to ear, because I was like, yup, yes, it is.” **HAVE A GREAT NOW!** “We always say ‘have a great day,’ or ‘have a great trip,’ but never ‘have a great now.’ Someone pointed this out to me once and it really hit me, so I used that idea to write the track. I started playing sounds on a synthesizer and connected them using compositional music theory, essentially making the entire song in the moment. It worked on these meta and microscopic levels. If you listen closely, it sounds like the track is cycling through dozens or hundreds of songs—almost like it has songs inside of songs. But I see it as a musical snapshot of my style, where everything is connected but distinct.” **METAL** “SOPHIE and I had been exchanging synthesizer files for years, and developing new styles of synthesis since 2011 or so. We were trying to figure out how to create sounds that sound like physical objects. I was downloading a lot of white papers from universities and doing all this technical research to figure out how to achieve this. Basically, a lot of the album is based on physical modeling, and there are a couple types of synthesis that are related to that. One is called ‘sweep step synthesis,’ which is emulating, say, the sound of rubbing your finger on glass, which casts the glass as a resonant body and the finger as something with tension and resistance. We ate this stuff up. ‘METAL’ was an attempt to lean into these concepts. She and I had a bunch of collaborations, but this was the one that felt like the most finished and relevant to the album.” **PAUSE** “I’d wanted to work with Matt Ox since I heard his fidget spinner song. He was, like, eight years old or something like that, and I just thought he was this interesting, enigmatic rapper. Plus, he was working with guys like Chief Keef, doing legit stuff. I found it really inspiring. I wanted to get him to sing because I liked his singing voice, but I also wanted him to rap, so I wrote the song in two sections that kind of repel each other. That’s a big part of the album, too, this idea of playing with extremes: soft sounds and hard sounds, big noises and negative space. I\'m a pretty extreme person, so I\'m always trying to push things. One thing I weirdly liked about this song was that I suspected some people might hate it, that they’d be annoyed by it or something. But I was drawn to that. I think it’s important to nurture art that’s more polarizing. It keeps you honest.”

“I’m not trying to reinvent myself,” Mike Milosh tells Apple Music. “I’m furthering my sound.” The Los Angeles singer/producer who heads up the electro-R&B project Rhye has, after three albums, a well-established aesthetic: ethereal, sumptuous soft-pop with gentle grooves and minimal production. On his contemplative fourth project, he applies these now signature characteristics to meditations on the idea of home. The album was largely inspired by Milosh’s recent move to Los Angeles’ bucolic Topanga Canyon. “I bought this home at the top of a mountain and I was very intentional about it,” he tells Apple Music. “I wanted a sacred, creative space.” He turned one of the property’s structures into a customized home studio, which he describes as “deeply analog,” and played with ways to refine his sound. “The space is set up ergonomically in a way where I can turn on all the synthesizers, their designated preamps and compressors, and float between any keyboard quickly without a lot of plugging or unplugging,” he says. “I like to have creative explosions when I’m writing, and this facilitates that immensely.” Unlike his past records, *Home* doesn’t have any midi or digital samples. Says Milosh: “Everything you hear, I created from scratch.” Read on as he takes us inside three key tracks. **Holy** “I always have musicians supporting me on my tracks, but ‘Holy’ is unique in that there\'s a 50-piece choir—the National Danish Girls\' Choir. Ben, a keyboardist who toured with me for about five years, was with me when I did the first concert with the Girls\' Choir in Copenhagen. We both felt so moved by them. I remember he was playing organ a lot at that concert, and there were moments when I’d look over at him and he was literally crying. The sheer beauty of the sound of the choir was overwhelming. That\'s when I decided I needed to have them on a record. They were game, and I always assumed I’d record them at their studio in Denmark. But it happened that they flew to Santa Barbara for a concert and were able to spend an entire day with me at the studio. This was right before the pandemic, and they did ‘Holy’ in one take. Ben and I were sitting in the control room mystified that it could happen that quickly, that perfectly. It was utter joy.” **Black Rain** “This weird thing happens to me where I write things that then become true. It\'s actually why I\'m careful to not write anything very dark or angry. When I wrote ‘Black Rain,’ I didn\'t understand what it was; I had come up with these stream-of-consciousness lyrics and rolled with it. But pretty soon after, the California wildfires started hitting and there was one day where it rained black soot all over my driveway. It was black rain. This really creepy, ominous feeling came over me at first, but I reminded myself that the song is about not letting anything get you down, about dancing your way through it. It’s also, more literally, about not ignoring the problems we’re causing. I don’t want there to be an ingenuity gap between our environmental damage and environmental cleanup. I want us to acknowledge it all, but to have fun while we do it. Life is beautiful, joyous, and precious. Let’s make positive, conscientious decisions.” **Sweetest Revenge** “‘Sweetest Revenge’ may sound like a mean song, but it’s about the realization that the best answer to negative energy is living a good life. If someone enters your life who doesn’t have good intentions or says something to get you down, the best thing that you can do is say, ‘I\'m not going to let that in. I\'m just going to enjoy my life.’ I’ve never been an overly emotional person; I’m the kind of guy who laughs when things get awkward or intense. Maybe that’s a way of coping, but it’s also about my outlook. I refuse to believe that anything I encounter is really that stressful or hard. I get to make music for a living. There\'s nothing stressful about that. Shooting a music video is not stressful. It\'s fun. Mixing records is fun. So I try to apply that mentality to the way I live. I believe that the way you do one thing is the way you do everything, and we train our minds how to deal with every scenario. On tour, you realize quickly that if you get stressed out when things go wrong, it infects everything. You’re better off laughing about it.”

With her incisive lyrics and gift for harnessing classic UK garage samples, PinkPantheress very quickly became one of 2021’s breakout stars. Her debut mixtape, *to hell with it*, is a bite-size collection of moreish pop songs and a small slice of the 20-year-old singer and producer’s creative output over the nine months since her first viral TikTok moment. “I basically put together the songs that I put out this year that I felt were strongest,” she tells Apple Music. “I sat in the studio with my manager and a good friend from home whose ear I trust, and I said, ‘Does this sound cohesive to you? Are the songs in a similar world?’” The world of *to hell with it* is one of sharp contrasts existing together in perfect balance: sweet, singsong vocals paired with frenetic breakbeats, floor-filler samples through a bedroom pop filter, confessional lyrics about mostly fictionalized experiences, and light, bright production with a solidly emo core. “They’re all vividly sad,” PinkPantheress says of the 10 tracks that made the cut. “I think I\'ve had a tendency, even on a particularly happy beat, to sing the saddest lyrics I can. I paint a picture of the actual scenarios where someone would be sad.” Here, the Bath-born, London-based artist takes us through her mixtape, track by track. **“Pain”** “In my early days on TikTok I was creating a song a day. Some of them got a good reception, but ‘Pain’ was the first one where people responded really well and the first one where the sound ended up traveling a little bit. It didn\'t go crazy, but the sound was being used by 30 people, and that got me quite excited. A lot of people haven’t really heard garage that much before, and I think that for them, the sample \[Sweet Female Attitude’s 2000 single ‘Flowers’\] is a very palatable way to ease into garage breakbeats, very British-sounding synths, and all those influences.” **“I must apologise”** “This track was produced by Oscar Scheller \[Rina Sawayama, Ashnikko\]. I was trying to stay away from a sample at this point, but there’s something about this beat \[from Crystal Waters’ 1991 single ‘Gypsy Woman (She’s Homeless)’\] which drugged me. When we started writing it, Oscar gave me the idea for one of the melodies and I remember thinking, ‘Wow, this actually is probably going to end up being one of my favorite songs just based off of this great melody that he\'s just come up with.’” **“Last valentines”** “My older cousin introduced me to LINKIN PARK; *Hybrid Theory* is one of my favorite albums ever. I went through the whole thing thinking, ‘Could I sample any of this?’ and when I listened to ‘Forgotten’ I just thought: ‘This guitar in the back is amazing. I can\'t believe no one\'s ever sampled it before!’ I looped it, recorded to it, mixed it, put it out. This was my first track where it took a darker turn, sonically. It really is emo through and through, from the sample to the lyrics.” **“Passion”** “To me, a lack of passion is just really not enjoying things like you used to—not having the same fun with your friends, finding things boring. I haven’t experienced depression myself, but I know people that have and I can attempt to draw comparisons of what I see in real life. Like it says in the lyrics, ‘You don’t see the light.’ I think I got a lot more emotional than I needed to get, but I\'m still glad that I went there. The instruments are so happy, I feel like there needed to be something to contradict it and make it a bit more three-dimensional.” **“Just for me”** “I made this song with \[UK artist and producer\] Mura Masa. I was sat with him, just going through references, and he started making the loop. I’ve never said this before, but I remember being like, ‘I don’t know if I’m going to be able to write anything good to this,’ and then it just came, after 20 minutes of sitting there wondering what I could do. The line ‘When you wipe your tears, do you wipe them just for me?’ just slipped off the tongue.” **“Noticed I cried”** “This is another track with Oscar Scheller and the first song I made without my own production. I held back a lot from working with producers, because I like working by myself, but Oscar is really good, so it ended up just being an easy process. He understood the assignment. I think it’s my favorite song I’ve ever released. It’s the top line, I’m just a big fan of the way it flows. I hope that people like it as much as I do.” **“Reason”** “Zach Nahome produced this track. He used to make a lot of garage, drum ’n’ bass, jungle, but his sound is quite different to that nowadays. So this was a bit of a different vibe for him. We made the beat together. I told him what kind of drums I wanted, what kind of sound and space I wanted, and he came up with that. With garage music, I just enjoy the breakbeats of it, the drums. It’s also quintessentially British. We birthed it. I think it’s always nice to go back to your roots.” **“All my friends know”** “I wanted to try something a bit different, and there were a few moments with this one where I wasn’t sure if I really liked it or not. After I stopped debating with myself it got a lot easier to enjoy it and I ended up feeling like it could actually be a lot of people’s favorite. The instrumental part of it is really beautiful; both producers—my friends Dill and Kairos—did a good job. It’s sentimental in a musical sense, and it’s sentimental in a personal sense as well.” **“Nineteen”** “This is a song that stems from personal experience, and kind of the first time in any of my songs where I’m like, ‘I’m actually speaking the truth here, this actually happened to me.’ Nineteen was a year of confusion, emotional confusion. I didn’t want to do my uni course, I wanted to do music. I didn\'t want people to laugh at me. I didn\'t want to tell myself out loud and then have it not happen. Internally, I was very sure and certain that it was going to happen, just because I\'m a big believer in manifestation. So 19 was that transition year. Once I\'d settled down and started doing what I loved, I felt a lot more comfortable, and actually, a lot more safe.” **“Break It Off”** “‘Break It Off’ was, I guess, my breakthrough track. It was the first time my name was being chucked around a fair bit. I fell in love with the original \[Adam F’s 1997 single ‘Circles’\] and I just wanted to hear what a top line would sound like on the track. So I found the instrumental, played around with it a little bit, and then sang on top. I think it got 100,000 likes on TikTok when I wasn’t really getting likes in that number before. The lyric is really tongue-in-cheek, and I think a lot of people on TikTok like tongue-in-cheek.”